Abstract

Introduction

The elapsed time between the onset of symptoms and reperfusion is a critial determinant of the clinical course of patients with myocardial infarction. The patients’ own decision time is the most important component of prehospital delay.

Methods

Selective literature review based on the references in a meta-analysis, complemented by a PubMed search on the expression "prehospital delay" in combination with "myocardial infarction," "acute coronary syndrome," "psychological factors," "gender," and "public campaign." A total of 73 papers addressing factors that influence prehospital delay were selected.

Results

The reasons for delays of more than 120 minutes in a patient with symptoms of myocardial infarction reaching the hospital are still not sufficiently elucidated. Patients’ uncertainty about their symptoms, advanced age, and female sex are three factors that appear to be associated with longer delays.

Discussion

Factors influencing prehospital delay operate at the following levels: the perception of acute symptoms, the recognition of the importance of these symptoms, and the decision to call for help. Intervention trials should consider these levels in meeting the needs of clinically relevant subpopulations.

Keywords: myocardial infarction, prehospital delay, epidemiology, prevention, psychological factors

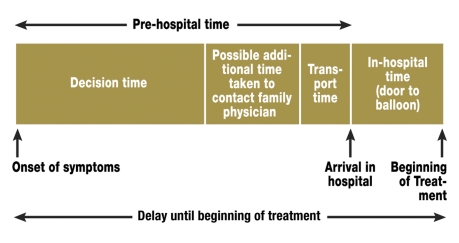

In acute myocardial infarction, the temporal window between the onset of symptoms and reperfusion is a critical determinant of the temporal course of treatment (e1–e3). Studies performed at the beginning of the thrombolysis era showed that the time taken up by the technical components of treatment is negligible by comparison (e4). A number of sources of delay were identified that were then dealt with individually to reduce delay times (e5). Yet the greatest part of the prehospital time (PHT) – as much as 75% of it – consists of the patient’s own decision time (1, e6) (figure 1). Even when medical rescue services function perfectly at a high technical level, the subjective element of the onset of illness remains the major factor in the time expended until treatment is delivered.

Figure 1.

The temporal window between the onset of symptoms and the beginning of treatment in acute myocardial infarction

Methods

The authors performed a review of the literature on the basis of the references of a current meta-analysis (e7), supplemented by a PubMed search between December 2006 and August 2007 on the on the expression "prehospital delay" in combination with "myocardial infarction," "acute coronary syndrome," "psychological factors," "gender," and "public campaign." This search revealed well over 100 articles published from 1990 to 2006 (and from 1984 for "public campaign"), which we considered with regard to the following subtopics: epidemiology, trends, sex differences, setting, previous illnesses, personality, and possibilities for prevention. The criteria for inclusion in this review were population access, population size, and the inclusion of a control group.

Results

Comparability of data

The data were rendered less comparable by variable methodology, differing segmentation of elapsed times, and differing inclusion criteria for the coronary patients (table). Patients who sustained an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) while in a state requiring acute resuscitation, or while already hospitalized, were not excluded from the analysis in all of the studies. Very short temporal windows should be viewed with some degree of skepticism, as it seems doubtful that patients’ reports of the time their symptoms began will be accurate to the minute (e8).

Table. Examples of varying types of study design.

| Study | Inclusion criteria | Latecomers | Method |

| NRMI-2 (1999) | Acute myocardial infarction | > 3 hours | Chart review |

| Sheifer et al. (2000) | Acute myocardial infarction | > 6 hours | Chart review |

| Ottesen et al. (2003) | Acute coronary syndrome | Not defined | Interview |

| McKinley et al. (2004) | Acute myocardial infarction | > 1 hour | Interview + Chart review |

| ARIC (2005) | Acute myocardial infarction | > 4 hours | Chart review |

| Taylor et al. (2005) | Undifferentiated chest pain | > 3 hours | Interview |

| GREECS (2006) | STEMI *1 / NSTEMI *2 / unstable angina pectoris | > 2 hours | Interview |

*1 STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

*2 NSTEMI, non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

The prevalence of prehospital delay

The patient’s chance of survival is significantly higher if treatment is begun within the so-called "golden hour" after the onset of symptoms (e3, e9), but few patients actually reach the hospital within this period. In three large-scale studies (2–4), only 22% to 44% of patients arrived at a hospital within two hours of the onset of symptoms. According to data collected in the Augsburg (southern Germany) Myocardial Infarction Registry (e10), 40% of patients with acute myocardial infarction have a prehospital time longer than four hours; even if a six-hour criterion is used, 25% to 33% of patients still arrive at the hospital too late. The percentage of patients arriving more than 12 hours after the onset of symptoms has remained between 10% and 20% (1–6, e5–e11).

International studies have shown that a very wide range of prehospital times (a few minutes to several days) is a ubiquitous phenomenon (2–4, 7–11). The mean PHT in Germany is now 192 minutes (9).

The PHT in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Germany is much too high, but it is even higher in Asian countries: as reported by McKinley et al. (12), the median PHT is 3.5 hours (1.2 to 15.2 hours) in the USA and 2.5 hours (1.5 to 8.7 hours) in the United Kingdom, but 4.4 hours (1.8 to 13.3 hours) in South Korea and 4.5 hours (2.0 to 16.3 hours) in Japan.

Trends in prehospital delay times

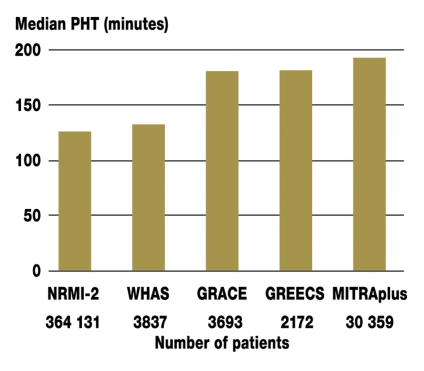

The MITRAplus registry, which contains data on over 30 000 patients and accurately reflects the delivery of care in Germany, has shown a significant prolongation of the median prehospital time from 166 minutes in 1994 to 192 minutes in 2002 (9). The multicenter ARIC study in the USA, with data on 18 928 patients (7), showed that the PHT became no shorter over the observation period from 1987 to 2000, but the percentage of patients who called the emergency medical services increased significantly. The American NRMI-2 myocardial infarction registry, with data on 364 131 patients, also showed no change in median PHT from 1994 to 1997 (8). A similar result was obtained in the Worcester Heart Attack Study (3), which showed no improvement in the time from symptom onset to treatment in the city of Worcester, Massachusetts, from 1986 to 1997. Quite the reverse: the percentage of patients with a PHT exceeding six hours grew over this period from about 18% to more than 22% (figure 2).

Figure 2.

The increasing median pre-hospital time in recent population-based registry studies.

NRMI-2, National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 2, 1999;

WHAS, Worcester Heart Attack Study, 2000; GRACE, Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events, 2002; GREECS, study of Pitsavos et al., Greece, 2006; MITRAplus, Maximal Individual Therapy in Acute Myocardial Infarction plus, 2006.

Social and demographic factors

Age – With the exception of only a few studies including small numbers of patients (13, 14), most published studies show a significant association of older age with longer PHT; the median figure is approximately 0.5 hours (2, 3, 7–10, 15, e11, e12).

Sex – Studies on potential sex differences in the perception of symptoms of acute myocardial infarction have revealed little in the way of significant differences. Data from the Augsburg Myocardial Infarction Registry (e10) on 486 women and 1436 men showed no difference in the frequency of typical chest pain, but a significantly higher frequency of nausea, dyspnea, and fear of death among women. Cold sweats were common in both sexes without any significant difference in frequency between them, though the study of Goldberg et al. (e13) arrived at a different conclusion. A possible effect of patient sex and symptoms on the PHT has been studied to date only by Meischke et al. (e14): although sex differences were found in the frequency of three different symptoms (women had cold sweats less frequently, but nausea and dyspnea more frequently), it was only the more frequent sweating among men that led to a shortening of the prehospital delay.

Nonetheless, most studies conclude that the PHT is significantly longer among women than among men (1–10, 15, e15). There are some indications that the difference has become smaller over the years (7). Moreover, it seems that a greater delay is often caused by the first physician contacted rather than by the patient herself (1, 7, e8). Moser et al. (16) found that age has only a minor influence on PHT in men, but a major one in women: women over age 55 had a PHT that was more than twice as long as that of younger women.

Social status – Smaller-scale studies (i.e., studies with fewer than 200 patients) have revealed no differences in PHT depending on social status (16, 17, e8), but larger studies indicate that patients with lower incomes (6, 14, e16) or with lower educational attainments (4, 7, 14, 18) have a longer PHT.

Clinical parameters and risk factors

Severity – Patients in cardiogenic shock after cardiac arrest arrive at the hospital sooner than others (2, 6, 15, 19, e15, e17). For these patients, the acute medical situation is so dramatic as to leave no room for subjective ambivalence. On the other hand, severity parameters such as the size of the infarct (15), enzyme values (13), ejection fraction, the number of occluded arteries (20), and the vital signs (16) do not seem to affect the PHT significantly.

Hypertension is associated with a longer PHT (2–5, 7, 8, 10), with a median of 2.2 hours as compared to 2.0 hours in normotensive patients (3). Three studies with smaller case numbers revealed no significant difference (1, 14, 21). One reason for this may be a less sensitive perception of pain in patients with hypertension as a risk factor for myocardial infarction (e18).

Diabetes – With a few exceptions (1, 14, 21), most studies have indicated that diabetes significantly predicts a longer PHT (2–4, 6–9). This may be due to the suppression of pain by diabetic neuropathy (e19).

Smoking – In three larger studies involving more than 2000 patients each (2, 4, 9), smokers had significantly shorter prehospital times than non-smokers. The reason for this is perhaps that the risk of myocardial infarction among smokers has been well publicized by the media (9).

The potential influence of body-mass index, hypercholesterolemia, and physical activity on prehospital times has only been investigated in the GREECS study (4); no significant effect was found for any of these factors.

Pre-existing heart disease

Angina pectoris – Patients with a prior history of angina pectoris tend to have a longer prehospital time (2, 3, 6, 19). Apparently, these patients have more difficulty identifying and attaching the proper significance to the chest pain of myocardial infarction. The ARIC study (7), however, found no effect of angina pectoris on the PHT, and the NRMI-2 study (8) and that of Kentsch et al. (18) even found that patients with prior angina pectoris arrived at the hospital earlier than others.

Previous myocardial infarction – Though one might imagine that patients who have previously sustained a myocardial infarction would arrive at the hospital more quickly in the event of reinfarction, this is by no means necessarily the case. The MITRAplus study (9) and a Swedish study with more than 2000 patients (10) showed no difference in PHT between patients with a first infarction and patients with a reinfarction. In the first study period of the Worcester Heart Attack Study (1986–1990), patients with reinfarctions actually took longer to get to a hospital (odds ratio 1.6 for a more than six-hour delay, as compared to patients with a first infarction) (22). A Danish study came to the conclusion that patients with a reinfarction have a markedly shorter PHT, while patients with a previous mechanical revascularization procedure interpreted their symptoms correctly but nevertheless had significantly longer decision times (1).

Previous revascularization or bypass operation – In most studies, these patients were found to arrive at the hospital sooner than others (2–4, 5–8, 15), perhaps because of the sensitization of their families and treating physicians by the previous events.

Contextual influences

Time of occurrence – Many studies have found no difference in PHT due to the time of day or the day of the week (11, 20–22, e20, e21), while others have found a shorter PHT at night (6, 19) or, alternatively, a longer PHT at night or on the weekend (2, 5, 9, e22).

Contact with family physician – Well under half of all patients call the emergency medical services first (5, 11, e23–e25); instead, many first contact their family physician. This prolongs the prehospital time (median, 120 minutes, compared to 74 minutes) (11, e23, e26, e27) (box 1).

Box 1. Subjective reasons why some patients inform the family physician first about their medical emergency (myocardial infarction).

The patient does not feel ill enough to call the emergency medical services (e24, e25)

The patient believes the family physician is "on his or her side" (e22)

The patient desires the family physician’s permission to call the emergency medical services (e22)

The patient believes calling the family physician first is the right thing to do, so that the family physician can then notify the emergency medical services (e22)

Home environment – Consultation of non-physicians for advice markedly prolongs the prehospital delay (18, 23); patients who do so have an odds ratio of 2.06 to 2.34 for a delay greater than one hour (11). Most patients ask their spouse for advice and 21% even speak with their children before calling a physician (e24). On the other hand, it may provide some degree of comfort to the patient to have someone else call the emergency medical team. A delegation of responsibility may be especially helpful when the patient’s symptoms do not correspond to his or her own conception of a heart attack (17, e22).

According to some studies, patients who experience their first symptoms while at home tend to arrive at the hospital with a greater delay than others (1, 24, e16, e26). Other studies, however, have shown no difference (14, 16, 20, e20, e21). The presence of other persons seems not to influence the prehospital time (12, 13, 16, 20, 24, e16, e20, e21, e28). Patients that try to suppress their warning symptoms by self-medication or self-distraction (23, e24) have a roughly threefold elevation of relative risk for arriving late at the hospital (18).

The acute perception of symptoms

Pain pattern – Chest pain is the most common symptom of myocardial infarction, with a frequency of 80% to 95% (21, 24, e13, e28). Patients with the classic sudden, unexpected, and severe chest pain are the most likely to arrive at the hospital in good time (23). Radiating pain also shortens the PHT (17). The intensity of the pain has no significant effect on the PHT (1, 12, 16, 20, e16, e29, e30). The intensity of anginal pain was positively correlated with a shorter PHT only in the studies of Horne (17), Rawles (25), and Dracup (14).

Symptoms – Vague symptoms and non-specific complaints are significant predictors of a delay in the patient’s decision time. Sweating occurs in about 65% to 75% of cases (24, e28) and tends to shorten the PHT (2, 14, 18, e18, e31). Excessive sweating after relatively mild physical exertion is likely to be interpreted as unusual and thus as a possible sign of serious illness (e31). Symptoms such as nausea and heartburn, which arise in 45% to 52% of patients (17, e28), lengthen the PHT (14, 24, e31). Shortness of breath, which arises in about 28% to 59% of patients (17, 21, e28), is an alarming symptom but is often misinterpreted and thus tends to prolong the PHT (2, 14, e20).

Previous knowledge – The patient’s knowledge of the main symptoms of myocardial infarction, including atypical ones such as sweating, nausea, or dyspnea, leads to a shorter prehospital delay (12, 23, e20), though not in all studies (14, 24). Dracup et al. (14) found that the patient’s knowledge of the possibilities for treatment shortened the PHT, but Ottesen et al. (1) found that knowledge about thrombolytic treatment made no difference to the PHT.

The patient’s own interpretation of the symptoms – The patient’s ability to interpret the symptoms correctly decisively determines his or her behavior. Patients who attribute their symptoms to a cardiac problem seek help more quickly (1, 13, 14, 16, 18, 20, 24, e30–e32). Only two smaller studies arrived at a different conclusion (e20, e28) (box 2).

Box 2. Delays caused by erroneous interpretation of symptoms.

Some patients have symptoms of myocardial infarction, but fail to react appropriately, because they:

do not consider the symptoms to be serious (e16, 18, 20, e23)

have a "mismatch between symptom expectations and experience" (17)

choose to wait and see whether the symptoms improve (12, 14, e16, 18, e23, e24, e26)

do not want to be a burden on anyone (14, e16, 18, e22, e26, e48)

find it unpleasant or embarrassing to seek medical help (12, 14, e16, 20, e22)

The complexity of interpretive behavior was made especially clear by Kentsch et al. (18) in their study of 739 patients with acute myocardial infarction. 44% of patients who realized that they were having a heart attack and were aware, at the same time, that heart attacks can be fatal, nonetheless took more than an hour to call for medical help. In a multivariate model, the following attitudes were found to contribute to these patients’ delay in deciding to seek medical attention: "I wanted to wait and see first"; "I didn’t take the symptoms seriously"; "I didn’t want to trouble anyone"; "The symptoms got better"; consumption of analgesics.

Fear of death – 35% of women and 20% of men experience the fear of death (a sensation of impending doom) during the acute infarction phase (11). In the study of Whitehead et al. (e33), 32.6% of women and 18.4% of men reported having experienced considerable worry and fear of death. Fear during the acute event significantly shortens the prehospital delay (16, 20, e28, e29).

Psychological factors

The psychological paradigms that would seem to have the greatest potential relevance to PHT are the concepts of denial and related types of operationalization, such as alexithymia (difficulty perceiving and expressing one’s own feelings). Here, too, the findings are inconsistent: O’Carroll et al. (e30) found no effect of alexithymia on the prehospital delay, while Kenyon et al. (13) found that it significantly prolonged the prehospital delay. Prolongation has likewise been found to result from a hyperactive behavior style (type A behavior) (19) and from a fatalistic attitude to one’s own health (e30).

In the study of Bunde and Martin (e31), which included 433 patients, a depressive mood was found to contribute significantly to a prolonged decision time. The only items that differed significantly between timely arrivers and latecomers had to do with fatigue, sleep disturbances, and exhaustion; thus, the correlation between depression and prehospital delay might reflect a difficulty mustering the energy required to call for help.

Opportunities for prevention

Most people know little about heart attacks. Many know that chest pain is an important symptom, but few can correctly name more than two further symptoms (e34). Thus, a number of studies have sought to answer the question whether prehospital delays might be shortened by public education in the media, public events, and special training. According to a review of ten studies on the influence of such efforts on the PHT (e35), four studies showed significantly shorter prehospital times than before the intervention (e36–e38), while six revealed no change (e39–e44), among them the REACT study (e43) (n = 20 364), which was carried out from 1995 to 1997 in 20 American cities. Although persons living in the target areas of the public information campaigns were demonstrably better informed about the subject afterward, the PHT in the target areas was not shortened significantly in comparison to control areas. On the other hand, the previous fear that false-positive self-referrals to the hospital would become more common after such information campaigns, thereby incurring higher costs, was not substantiated (e39).

Discussion

On both the national and the international level, the prehospital time (PHT) is the most important factor leading to a temporal delay in the initiation of treatment for acute myocardial infarction. The studies that have been performed to date show that the most important factors influencing the PHT are the sex and age of the patient and the patient’s misinterpretation of the symptoms. Empirical data on the effect of psychological mechanisms and coping strategies remain scarce at present.

One cannot yet draw a clear risk profile for "latecomers" that would be of use in everyday clinical practice and in patient education. There is still no theoretically well-founded and empirically confirmed basis for understanding patients’ decisional behavior thus predicting their actions. There is a consensus, however, that general knowledge about the typical symptoms of heart attack is a necessary foundation of prevention but still does not suffice to prepare patients adequately for an acute crisis (e17).

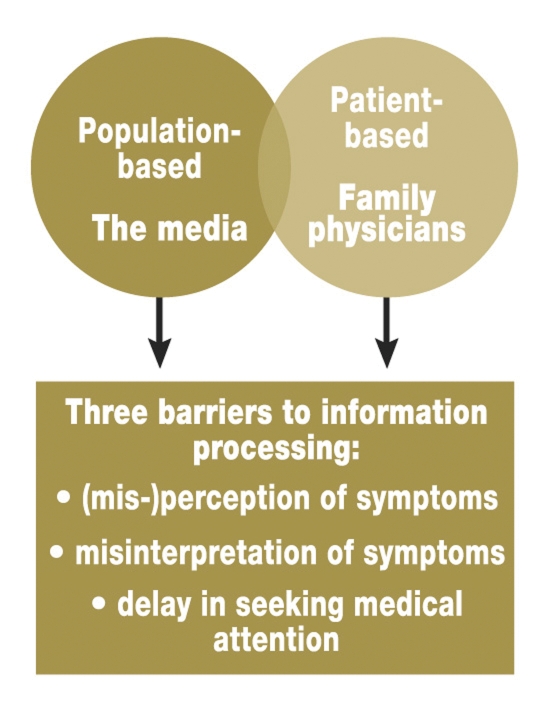

In the future, the psychosocial and economic conditions of the population will have to be considered more closely, patients at high risk will have to receive greater individual attention, and more sex-specific patient education will have to be provided (e45). Preventive action will have to be tailored more specifically to the groups that are most at risk. It would be desirable to develop predictive algorithms for decisional behavior in groups with well-defined identifying features (e.g., age < 60; female sex; anxious-avoidant behavior style), so that individualized prevention strategies could be offered (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Goal-orientation in preventive strategies for the reduction of pre-hospital delay

A further opportunity to identify patients at risk seems to be provided by observation of the prodromal phase of acute myocardial infarction. In the days preceding the acute event, many patients suffer increased irritability, depressive mood, unexplained fatigue, or anxiety (e46, e47). Physicians consulted because of such symptoms should think of the possibility of an impending myocardial infarction and take the corresponding steps to inform the patient about what to do in case this happens.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Ethan Taub, M.D.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors state that they have no conflict of interest as defined by the guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

References

- 1.Ottesen MM, Dixen U, Torp-Pedersen C, Kober L. Prehospital delay in acute coronary syndrome - an analysis of the components of delay. Int J Cardiol. 2004;96:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2003.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldberg RJ, Steg PG, Sadiq I, et al. Extent of, and factors associated with delay to hospital presentation in patients with acute coronary disease (the GRACE registry) Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:791–796. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02186-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldberg RJ, Yarzebski J, Lessard D, Gore JM. Decade-long trends and factors associated with time to hospital presentation in patients with acute myocardial infarction: the Worcester Heart Attack Study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3217–3223. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.21.3217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pitsavos C, Kourlaba G, Panagiotakos DB, Stefanadis C. Factors associated with delay in seeking health care for hospitalized patients with acute coronary syndromes: the GREECS study. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2006;47:329–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gurwitz JH, McLaughlin TJ, Willison DJ, et al. Delayed hospital presentation in patients who have had acute myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:593–599. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-8-199704150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sheifer SE, Rathore SS, Gersh BJ, et al. Time to presentation with acute myocardial infarction in the elderly: associations with race, sex, and socioeconomic characteristics. Circulation. 2000;102:1651–1656. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.14.1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGinn AP, Rosamond WD, Goff DC, Jr, Taylor HA, Miles JS, Chambless L. Trends in prehospital delay time and use of emergency medical services for acute myocardial infarction: experience in 4 US communities from 1987-2000. Am Heart J. 2005;150:392–400. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldberg RJ, Gurwitz JH, Gore JM. Duration of, and temporal trends (1994-1997) in prehospital delay in patients with acute myocardial infarction: the second National Registry of Myocardial Infarction. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:2141–2147. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.18.2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mark B, Meinertz T, Fleck E, et al. Stetige Zunahme der Prähospitalzeit beim akuten Herzinfarkt. Dtsch Arztebl. 2006;20:1378–1383. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blohm Berglin M, Hartford M, Karlsson T, Herlitz J. Factors associated with prehospital and inhospital delay time in acute myocardial infarction: a 6-year experience. J Intern Med. 1998;243:243–250. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1998.00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lovlien M, Schei B, Hole T. Prehospital delay, contributing aspects and responses to symptoms among Norwegian women and men with first time acute myocardial infarction. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2007.03.002. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKinley S, Dracup K, Moser DK, et al. International comparison of factors associated with delay in presentation for AMI treatment. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2004;3:225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kenyon LW, Ketterer MW, Gheorghiade M, Goldstein S. Psychological factors related to prehospital delay during acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1991;84:1969–1976. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.84.5.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dracup K, McKinley SM, Moser DK. Australian patients’ delay in response to heart attack symptoms. Med J Aust. 1997;166:233–236. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1997.tb140101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leizorovicz A, Haugh MC, Mercier C, Boissel JP. Prehospital and hospital time delays in thrombolytic treatment in patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction. Analysis of data from the EMIP study. European Myocardial Infarction Project. Eur Heart J. 1997;18:248–253. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moser DK, McKinley S, Dracup K, Chung ML. Gender differences in reasons patients delay in seeking treatment for acute myocardial infarction symptoms. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;56:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horne R, James D, Petrie K, Weinman J, Vincent R. Patients’ interpretation of symptoms as a cause of delay in reaching hospital during acute myocardial infarction. Heart. 2000;83:388–393. doi: 10.1136/heart.83.4.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kentsch M, Rodemerk U, Muller-Esch G, et al. Emotional attitudes toward symptoms and inadequate coping strategies are major determinants of patient delay in acute myocardial infarction. Z Kardiol. 2002;91:147–155. doi: 10.1007/s003920200004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ladwig KH, Lehmacher W, Roth R, Breithardt G, Budde T, Borggrefe M. Patientenbezogene Determinanten der Verzögerung in einem zielorientierten Patientenverhalten bei akutem Myokardinfarkt. Ergebnisse aus der Postinfarkt-Spätpotential-Studie (PILP) Z Kardiol. 1991;80:649–656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burnett RE, Blumenthal JA, Mark DB, Leimberger JD, Califf RM. Distinguishing between early and late responders to symptoms of acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:1019–1022. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80716-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fukuoka Y, Dracup K, Rankin SH, et al. Prehospital delay and independent/interdependent construal of self among Japanese patients with acute myocardial infarction. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:2025–2034. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yarzebski J, Goldberg RJ, Gore JM, Alpert JS. Temporal trends and factors associated with extent of delay to hospital arrival in patients with acute myocardial infarction: the Worcester Heart Attack Study. Am Heart J. 1994;128:255–263. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(94)90477-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruston A, Clayton J, Calnan M. Patients’ action during their cardiac event: qualitative study exploring differences and modifiable factors. BMJ. 1998;316:1060–1064. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7137.1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dracup K, Moser DK. Beyond sociodemographics: factors influencing the decision to seek treatment for symptoms of acute myocardial infarction. Heart Lung. 1997;26:253–262. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(97)90082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rawles JM, Metcalfe MJ, Shirreffs C, Jennings K, Kenmure AC. Association of patient delay with symptoms, cardiac enzymes, and outcome in acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 1990;11:643–648. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a059770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e1.Zahn R, Schiele R, Gitt AK, et al. Impact of prehospital delay on mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated with primary angioplasty and intravenous thrombolysis. Am Heart J. 2001;142:105–111. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.115585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e2.Steg PG, Bonnefoy E, Chabaud S, et al. Impact of time to treatment on mortality after prehospital fibrinolysis or primary angioplasty: data from the CAPTIM randomized clinical trial. Circulation. 2003;108:2851–2856. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000103122.10021.F2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e3.De Luca G, van’t Hof AW, de Boer MJ, et al. Time to treatment significantly affects the extent of ST-segment resolution and myocardial blush in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated by primary angioplasty. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1009–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e4.Schroeder JS, Lamb IH, Hu M. The prehospital course of patients with chest pain. Analysis of the prodromal, symptomatic, decision-making, transportation and emergency room periods. Am J Med. 1978;64:742–748. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(78)90512-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e5.Rogers WJ, Canto JG, Lambrew CT, et al. Temporal trends in the treatment of over 1.5 million patients with myocardial infarction in the US from 1990 through 1999: the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 1, 2 and 3. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:2056–2063. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00996-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e6.Weaver WD. Time to thrombolytic treatment: factors affecting delay and their influence on outcome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25:3–9. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00108-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e7.Moser DK, Kimble LP, Alberts MJ, et al. Reducing delay in seeking treatment by patients with acute coronary syndrome and stroke: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on cardiovascular nursing and stroke council. Circulation. 2006;114:168–182. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.176040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e8.Fukuoka Y, Dracup K, Ohno M, Kobayashi F, Hirayama H. Symptom severity as a predictor of reported differences of prehospital delay between medical records and structured interviews among patients with AMI. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2005;4:171–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e9.Boersma E, Maas AC, Deckers JW, Simoons ML. Early thrombolytic treatment in acute myocardial infarction: reappraisal of the golden hour. Lancet. 1996;348:771–775. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)02514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e10.Löwel H, Meisinger C, Heier M, Hörmann A, v Scheidt W. Herzinfarkt und koronare Sterblichkeit in Süddeutschland. Dtsch Arztebl. 2006;103(10):A616–A622. [Google Scholar]

- e11.Grossman SA, Brown DF, Chang Y, et al. Predictors of delay in presentation to the ED in patients with suspected acute coronary syndromes. Am J Emerg Med. 2003;21:425–428. doi: 10.1016/s0735-6757(03)00106-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e12.Goodacre S, Kelly AM, Kerr D. Potential impact of interventions to reduce times to thrombolysis. Emerg Med J. 2004;21:625–629. doi: 10.1136/emj.2003.012575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e13.Goldberg RJ, O’Donnell C, Yarzebski J, Bigelow C, Savageau J, Gore JM. Sex differences in symptom presentation associated with acute myocardial infarction: a population-based perspective. Am Heart J. 1998;136:189–195. doi: 10.1053/hj.1998.v136.88874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e14.Meischke H, Larsen MP, Eisenberg MS. Gender differences in reported symptoms for acute myocardial infarction: impact on prehospital delay time interval. Am J Emerg Med. 1998;16:363–366. doi: 10.1016/s0735-6757(98)90128-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e15.Bouma J, Broer J, Bleeker J, van Sonderen E, Meyboom-de Jong B, DeJongste MJ. Longer prehospital delay in acute myocardial infarction in women because of longer doctor decision time. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53:459–464. doi: 10.1136/jech.53.8.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e16.McKinley S, Moser DK, Dracup K. Treatment-seeking behavior for acute myocardial infarction symptoms in North America and Australia. Heart Lung. 2000;29:237–247. doi: 10.1067/mhl.2000.106940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e17.Senges J, Schiele R. Prähospitalzeit - Patientenwissen allein reicht nicht aus. Z Kardiol. 2004;93(Suppl 1):16–18. doi: 10.1007/s00392-004-1106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e18.Falcone C, Auguadro C, Sconocchia R, Angoli L. Susceptibility to pain in hypertensive and normotensive patients with coronary artery disease: response to dental pulp stimulation. Hypertension. 1997;30:1279–1283. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.5.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e19.Jermendy G. Clinical consequences of cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy in diabetic patients. Acta Diabetol. 2003;40(Suppl 2):370–374. doi: 10.1007/s00592-003-0122-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e20.Noureddine S, Adra M, Arevian M, et al. Delay in seeking health care for acute coronary syndromes in a Lebanese sample. J Transcult Nurs. 2006;17:341–348. doi: 10.1177/1043659606291544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e21.Schmidt SB, Borsch MA. The prehospital phase of acute myocardial infarction in the era of thrombolysis. Am J Cardiol. 1990;65:1411–1415. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)91345-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e22.Pattenden J, Watt I, Lewin RJ, Stanford N. Decision making processes in people with symptoms of acute myocardial infarction: qualitative study. BMJ. 2002;324:1006–1009. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7344.1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e23.Leslie WS, Urie A, Hooper J, Morrison CE. Delay in calling for help during myocardial infarction: reasons for the delay and subsequent pattern of accessing care. Heart. 2000;84:137–141. doi: 10.1136/heart.84.2.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e24.Hartford M, Karlson BW, Sjolin M, Holmberg S, Herlitz J. Symptoms, thoughts, and environmental factors in suspected acute myocardial infarction. Heart Lung. 1993;22:64–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e25.Lozzi L, Carstensen S, Rasmussen H, Nelson G. Why do acute myocardial infarction patients not call an ambulance? An interview with patients presenting to hospital with acute myocardial infarction symptoms. Intern Med J. 2005;35:668–671. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2005.00957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e26.Taylor DM, Garewal D, Carter M, Bailey M, Aggarwal A. Factors that impact upon the time to hospital presentation following the onset of chest pain. Emerg Med Australas. 2005;17:204–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2005.00724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e27.Hitchcock T, Rossouw F, McCoubrie D, Meek S. Observational study of prehospital delays in patients with chest pain. Emerg Med J. 2003;20:270–273. doi: 10.1136/emj.20.3.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e28.Morgan DM. Effect of incongruence of acute myocardial infarction symptoms on the decision to seek treatment in a rural population. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2005;20:365–371. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200509000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e29.Walsh JC, Lynch M, Murphy AW, Daly K. Factors influencing the decision to seek treatment for symptoms of acute myocardial infarction: an evaluation of the Self-Regulatory Model of illness behaviour. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56:67–73. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e30.O’Carroll RE, Smith KB, Grubb NR, Fox KA, Masterton G. Psychological factors associated with delay in attending hospital following a myocardial infarction. J Psychosom Res. 2001;51:611–614. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00265-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e31.Bunde J, Martin R. Depression and prehospital delay in the context of myocardial infarction. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:51–57. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000195724.58085.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e32.Meischke H, Eisenberg MS, Schaeffer SM, Damon SK, Larsen MP, Henwood DK. Utilization of emergency medical services for symptoms of acute myocardial infarction. Heart Lung. 1995;24:11–18. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(05)80090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e33.Whitehead DL, Strike P, Perkins-Porras L, Steptoe A. Frequency of distress and fear of dying during acute coronary syndromes and consequences for adaptation. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:1512–1516. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.07.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e34.Goff DC, Jr, Sellers DE, McGovern PG, et al. Knowledge of heart attack symptoms in a population survey in the United States: the REACT Trial. Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:2329–2338. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.21.2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e35.Kainth A, Hewitt A, Sowden A, et al. Systematic review of interventions to reduce delay in patients with suspected heart attack. Emerg Med J. 2004;21:506–508. doi: 10.1136/emj.2003.013276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e36.Blohm M, Hartford M, Karlson BW, Karlsson T, Herlitz J. A media campaign aiming at reducing delay times and increasing the use of ambulance in AMI. Am J Emerg Med. 1994;12:315–318. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(94)90147-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e37.Gaspoz JM, Unger PF, Urban P, et al. Impact of a public campaign on pre-hospital delay in patients reporting chest pain. Heart. 1996;76:150–155. doi: 10.1136/hrt.76.2.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e38.Mitic WR, Perkins J. The effect of a media campaign on heart attack delay and decision times. Can J Public Health. 1984;75:414–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e39.Bett N, Aroney G, Thompson P. Impact of a national educational campaign to reduce patient delay in possible heart attack. Aust N Z J Med. 1993;23:157–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1993.tb01810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e40.Ho MT, Eisenberg MS, Litwin PE, Schaeffer SM, Damon SK. Delay between onset of chest pain and seeking medical care: the effect of public education. Ann Emerg Med. 1989;18:727–731. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(89)80004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e41.Moses HW, Engelking N, Taylor GJ, et al. Effect of a two-year public education campaign on reducing response time of patients with symptoms of acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1991;68:249–251. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(91)90753-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e42.Meischke H, Dulberg EM, Schaeffer SS, Henwood DK, Larsen MP, Eisenberg MS. „Call fast, Call 911“: a direct mail campaign to reduce patient delay in acute myocardial infarction. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1705–1709. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.10.1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e43.Luepker RV, Raczynski JM, Osganian S, et al. Effect of a community intervention on patient delay and emergency medical service use in acute coronary heart disease: the Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment (REACT) Trial. Jama. 2000;284:60–67. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e44.Rustige J, Schiele R, Schneider J, Senges J. Intravenous thrombolysis in acute myocardial infarct: optimization of the therapeutic strategy by informing the patients and physicians. Anasthesiol Intensivmed Notfallmed Schmerzther. 1992;27:205–208. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1000282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e45.Caldwell MA, Miaskowski C. Mass media interventions to reduce help-seeking delay in people with symptoms of acute myocardial infarction: time for a new approach? Patient Educ Couns. 2002;46:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00153-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e46.Appels A, Kop WJ, Schouten E. The nature of the depressive symptomatology preceding myocardial infarction. Behav Med. 2000;26:86–89. doi: 10.1080/08964280009595756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e47.Ottolini F, Modena MG, Rigatelli M. Prodromal symptoms in myocardial infarction. Psychother Psychosom. 2005;74:323–327. doi: 10.1159/000086324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e48.Kaur R, Lopez V, Thompson DR. Factors influencing Hong Kong Chi nese patients’ decision-making in seeking early treatment for acute myocardial infarction. Res Nurs Health. 2006;29:636–646. doi: 10.1002/nur.20171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]