Abstract

Background and Purpose

Human embryonic stem cells (hESC) are considered a renewable source of dopamine producing neurons, and are of particular interest for their potential clinical use in Parkinson’s disease. In this study, we characterized human dopaminergic neurons generated by stromal-derived inducing activity (SDIA) from BG01V2, a strain of human embryonic stem cell line, BG01, characterized by a chromosome 17 trisomy. Similar chromosomal changes have been repeatedly observed in hESC cultures in different laboratories, indicating the importance of chromosome 17 for growth and adaptation of hESC to culture.

Methods

We investigated in vitro proliferation of differentiating cells using a BrDU incorporation assay, and monitored the cell population in long term cultures. Despite the cytogenetic abnormality, TH+ neurons were postmitotic at all stages of differentiation. After 30 days of differentiation, cell division ceased in 91% of the overall population of cells in the culture, indicating intact cell cycle regulation.

Results

Expression of midbrain specific marker genes (Otx2, Pax5, Msx-1) showed differentiation of hESC-derived neural progenitor cells into midbrain specific dopamine neurons. These neurons expressed the dopamine transporter (DAT), and displayed functional DAT activity and electrical excitability.

Conclusions

TH+ cells derived from the BG01V2 hESC line using SDIA are postmitotic and have functional characteristics of normal dopaminergic neurons.

Keywords: SDIA, embryonic stem cells, human, dopaminergic neuron, PA6 cells, BG01V2, trisomy 17, stem cell

1. Introduction

hESC are pluripotent cells obtained from the inner cell mass of pre-implantation blastocysts. hESC are self-replicating and can be maintained indefinitely in vitro in an undifferentiated state under defined conditions. The primary method for the maintenance of pluripotency in hESC requires the presence of mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) feeder layers. As hESC colonies enlarge, the hESC need to be frequently passaged and transferred to freshly-prepared MEF layers to prevent differentiation.

Techniques for sub-culturing hESC fall into two distinct categories, mechanical dissection and enzymatic isolation. Propagation of the cells using mechanical dissection is relatively difficult and laborious as compared to enzymatic methods, and cannot be easily applied on a large scale. There is, however, evidence that enzymatic passaging of hESCfor prolonged periods promotes genetic instability, and in particular leads to chromosomal abnormalities [7, 11, 22]. The cause of this genetic instability is not entirely understood, although it may be due to the disruption of cell-cell contacts by enzymatic treatment. Nonetheless, it is generally acknowledged that cells of any type maintained for extended periods in culture will develop genetic abnormalities [4]. This occurs in part due to adaptation to culture conditions, and in part because cells with an increased growth rate have an advantage among a population of normal cells [6]. Moreover, in vitro conditions confer no selection advantage in favor of normal cells.

Thus, even though manual passaging appears to maintain the genetic integrity of hESC colonies [8], it is likely that manual passaging merely delays, rather than entirely prevents, the occurrence of genetic abnormalities in hESC. Karyotype analysis is the most convenient, but not the most sensitive, means of detecting genetic abnormalities, and can only identify very large-scale changes (i.e., chromosomal rearrangements). It is probable that other, more subtle, mutations take place in hESC when they are maintained in vitro for extended periods under any circumstance [14, 21]. The occurrence of such genetic changes needs to be carefully considered in research on hESC and generation of various types of somatic cells from hESC.

We have previously described a variant hESC line BG01, which despite being karyotypically abnormal (49, +12. +17, XXY) shows normal differentiation and pluripotency [24, 26, 42]. More recently, the hESC line BG01 was propagated by manual dissection for several passages, and subsequently passaged every 4–5 days using collagenase. The BG01 cells retained a normal karyotype of 46, XY for 44 passages, but subsequently converted to trisomy 17. These trisomy 17 cells were karyotypically stable, and showed a remarkably consistent growth rate and dopaminergic neuronal differentiation. Dopaminergic differentiation of these cells was therefore characterized more extensively.

As previously reported [36, 41], we employed the SDIA model to induce dopaminergic differentiation of this variant of BG01. SDIA was identified by Kawasaki et al. (2000), who showed that co-culture of PA6 cells with hESC leads to enhanced neuralization and progressive fate restriction of the hESC to a mesencephalic dopaminergic lineage [19]. In previous studies, we described a method to isolate neural progenitor cells (NPC) expressing the neural precursor markers PSA-NCAM and nestin from the PA6 cell layers [36]. Isolated NPC were differentiated in the presence of Sonic Hedgehog Homolog (SHH), Fibroblast Growth Factor 8 (FGF8), and Glial Cell Line-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (GDNF). SHH and FGF8 are instructive regionalization molecules in early neural development leading to induction and establishment of midbrain dopaminergic progenitors [17, 31, 38]. GDNF is a potent survival and differentiation factor for both dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra and motorneurons [20, 30].

Previous studies have reported that genes involved in development and maintenance of the midbrain dopaminergic neuronal phenotype including Nurr1, Pitx3 and engrailed 1 are expressed in TH+ neurons derived by the SDIA protocol, suggesting that these cells are of the midbrain dopaminergic neuronal subtype [25, 41]. In the present study we investigated the early specification of ventral mesencephalic precursors by examining expression of key transcription factors involved in midbrain dopaminergic induction including Pax2, Pax5, Otx2 and Msx-1. Pax2 and Pax5 are co-expressed at the midbrain-hindbrain boundary. These factors, in combination with Otx2, function as organizers which control the development of the mesencephalon and metencephalon [32, 33, 35, 37]. A recent study using mouse and chicken embryos found identified Msx1 critical for specifying midbrain dopaminergic fate, by inducing the expression of neurogenin 2 (Ngn2) following neuronal differentiation [3]. We also evaluated whether the dopamine transporter, exclusively found in the midbrain [Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), accessible at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/gds/gds_browse.cgi?gds=868], was expressed in TH+ neurons from our cultures. DAT function was assessed by using a DAT binding cocaine analog [3H] WIN 35428.

In addition, the functional maturation of hESC-derived neurons was monitored by measuring electrical excitability of neuronal cells, at two different time points during differentiation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Human embryonic stem cell culture

The human stem cell line BG01 has been previously described and was obtained from BresaGen [7]. The hESC were maintained undifferentiated by passaging on mitomycin-C-treated MEF (Millipore, Billerica, MA, http://www.millipore.com). For passage at 5- to 7-day intervals, colonies were treated with 1 mg/ml collagenase type IV (Worthington Biochemical Corporation, Lakewood, NJ) for approximately 2 hr and dissociated into small clusters and re-plated on freshly prepared MEF feeder layers. The hESC were cultured at 37°C, 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium/nutrient mixture, supplemented with 10% knockout serum replacement, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1mM nonessential amino acid, 4 ng/ml bFGF, 50 U/ml Penn-Strep (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD), and 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol (Millipore).

BG01 cells have been cultured several times in our laboratory. In previous experiments, BG01 cells passaged with trypsin developed karyotype abnormalities by passage 32. The majority of cells progressively developed additional abnormalities with karyotype XXY, +12, +14, +17 by passage 84. Other BG01 cultures passaged manually remained normal to at least passage 52 [7]. For cells passaged with collagenase, one culture remained normal through at least passage 60. The cells described in the present study are from a separate culture which became trisomic for chromosome 17 by passage 44. We will refer to this line as a second variant of BG01, termed BG01V2.

2.2. Derivation of dopaminergic neurons

Differentiation to a dopaminergic phenotype was achieved by co-culturing hESC with the PA6 mouse stromal cell line (Riken BioResource Center Cell Bank, Tsukuba, Japan; http://www2.brc.riken.jp) as previously described [36]. Briefly, the PA6 cell growth medium consisted of α–minimum essential medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals, Lawrenceville, GA; https://atlantabio.safepackets.com/index.asp) and 50 U/ml Pen/Strep. PA6 cells were grown to 100% confluence on collagen type-I coated 6-well plates in PA6 growth media. One day prior to the co-culture experiments, the culture media was replaced with differentiation media, containing Glasgow minimum essential medium,10% knockout serum replacement, 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids (Gibco), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis) and 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol (Millipore). Small clusters of hESC at a density of ~ 5000–10000 cells/cm2 were plated onto the PA6 cell layers.

After 10–12 days of co-culture, the partially differentiated hESC were isolated from the PA6 feeder cells by papain treatment. The isolated cells were plated onto 6-well plates coated with poly-L-lysine (10 mg/ml; Sigma) followed by laminin (20 μg/ml; Sigma) in small clusters at a density of 10000–20000 cells/cm2. After isolation, the neural progenitor cells were cultured in the presence of 40 ng/ml SHH, 40 ng/ml FGF8 and 20 ng/ml GDNF (all from R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

2.3. Dopamine transporter (DAT) binding assay

The [3H] WIN35428 binding assay was performed using a 0.32 M sucrose and 10 mM Na2HPO4 buffer. Intact cells were incubated with [3H] WIN35428 (30 nM final concentration) and increasing concentrations of unlabeled WIN 35428, ranging from 10 nM to 100 μM for 1 h at room temperature on a shaker, followed by mechanical scraping and rapid filtration with Whatman GF/B glass fiber filters presoaked in 0.01% polyethylenimine using a Brandel 12-well cell harvester. After several washes with sucrose-phosphate buffer, the filter was placed in a scintillation vial, which was assayed with 4 ml of cytoscint cocktail. Non-specific binding was defined by adding 100 μM GBR12909. Percentages of specific binding were calculated and defined as: Percentage of specific binding = Specific binding (dpm) − Non-specific binding (dpm)/total binding (dpm)/mg protein × 100. Protein assays were used in the normalization of saturation binding data to account for differences in cell numbers in cultures. Assays were done in duplicate with each experiment repeated three times. GraphPad Prism 4.0 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA) was used for non-linear curve fitting and estimation of the IC50 value.

2.4. Electrophysiology

The cells were recorded at ambient temperature in a bathing medium consisting of (mM): NaCl 143, KCl 5, CaCl2 1.8, MgCl2 0.8, NaH2PO4 0.9, hemi-sodium HEPES 10, glucose 18.7, brought to pH 7.4 with NaOH. The osmolarity was identical to that of the growth medium (312 mOsm). The cells were held at a holding potential of −60 mV under conventional whole cell voltage clamp at 100% series resistance compensation using the Alembic VE-2 amplifier (Alembic Instruments, Montreal QC, Canada). Patch pipettes usually had resistances of 2–4 MΩ and contained (mM): KCl 140, MgCl2 2, CaCl2 1, EGTA 11, HEPES 10, brought to pH 7.2 with KOH. The command potential was stepped in 10 mV increments (100 ms duration) from the holding potential through the range of −70 to +50 mV. Currents were filtered at 10 kHz and sampled at 50 kHz.

2.5. Cell proliferation assay

For the BrDU incorporation assay, cells were incubated for 20 hr with 10 μg/ml BrDU (Sigma), in differentiation media. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and washed 3 times with PBS followed by treatment with 95% methanol for 10 min on ice. After three washes with PBS, cells were permeabilized with 2N HCl for 10 min at room temperature. The acid was washed away and neutralized with 0.1 M sodium borate for 5 min at room temperature twice. After rinsing with PBS, cells were incubated in blocking buffer containing 10% goat serum and 0.1% Triton X-100 for 20 min at room temperature. The cells were incubated with the following primary antibodies: mouse anti-BrDU (1:200; BD Pharmigen, San Diego, CA) and rabbit antiTH (1:100; Pel-Freez, Rogers, AR) for 2 hr in blocking buffer. Cultures were washed with PBS and then incubated with fluorescent-labeled secondary antibodies, alexa 594-conjugated anti-rabbit and alexa 488-conjugated anti-mouse in PBS containing 1% BSA for 45 min (1:500; Molecular Probes). After three washes with PBS, the cultures were counter-stained with DAPI (Molecular probes).

2.6. Immunocytochemistry

Cultures were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS and then incubated with the primary antibodies in blocking buffer (PBS containing 5% goat serum, 2% BSA and 0.2% Triton X-100) at room temperature for 2 hr. The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit anti-TH (1:1000; Pel-Freez), rabbit anti-glutamate (1:1000), mouse anti-α-smooth muscle actin (ASMA) (1:500; all from Sigma), mouse anti-nestin (1:50) and mouse anti-Otx2 (1:50; all from R & D Systems), rabbit anti-microtubule-associated protein (MAP-2) (1:1000), and mouse anti-GalC (1:100; all from Millipore), mouse anti-Msx1/2 (1:100; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA), rabbit anti-DAT (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), rabbit anti-serotonin (5-HT) (1:500; ImmunoStar Inc., Hudson, WI), and rabbit anti-Pax5 (1:50; Abcam, Cambridge, MA). Cultures were incubated with fluorescent-labeled secondary antibodies [Alexa 488 (green) or Alexa 568 (red)-labeled goat IgG; 1:1000; Molecular Probe] in PBS with 1% BSA for 1 hr at room temperature. The cells were rinsed three times for 5 min in PBS. The Pel-Freez polyclonal TH antibody has been extensively studied and is known to be reliable and specific for immunocytochemical and immunohistochemical detection of TH. In addition, we used a monoclonal anti-TH antibody recognizing an epitope in the N-terminus(1:100; Sigma), and rat brain sections to verify the specificity of the polyclonal TH antibody. Negative controls included substituting the primary antibodies with non-immune mouse and rabbit IgG (1:100; Santa Cruz). Images were obtained using a Carl Zeiss Axiovert 200M microscope.

2.7. Statistics

Differences in percentages of BrDU+ and TH+ cells were tested by analysis of variance followed by Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons. Levels of significance are indicated by asterisks on the line graph and legend of Figure 6. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Conversion of the hESC line BG01 to BG01V2

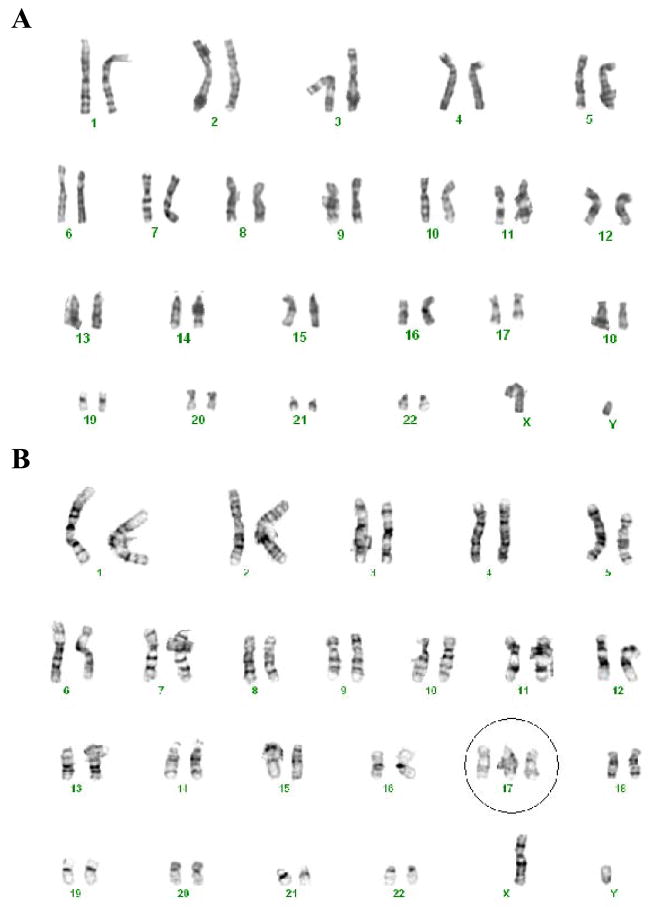

The BG01 cells retained a normal karyotype of 46, XY for 44 passages, but subsequently converted to trisomy 17 (Fig. 1). We periodically performed karyotype analysis to monitor the genetic integrity of the hESC in continuous culture. This variant of BG01, designated BG01V2, sustained a consistent trisomy 17 until at least passage 80, with no development of additional karyotype abnormalities. All the experiments described in this report were carried out using passages 71–79 of the BG01V2 line.

Figure 1.

Representative karyotype of BG01 and BG01V2 hESC lines. (A) Karyotype for a separate culture of normal BG01 cells, which did not develop chromosome 17 trisomy, at passage 60. (B) Abnormal karyotype of BG01V2 at passage 73, illustrating the gain of chromosome 17.

3.2. Differentiation of BG01V2 by SDIA

In a recent study we described neural induction of BG01V2 cells by PA6 cells and showed that neural progenitor cells isolated from co-cultures with PA6 cells were able to differentiate into glial, neuronal, and dopaminergic lineages under feeder-free conditions [36]. The differentiating hESC colonies were isolated from co-cultures after approximately 10–12 days and allowed to differentiate for an additional 18 days in the presence of SHH, FGF8 and GDNF.

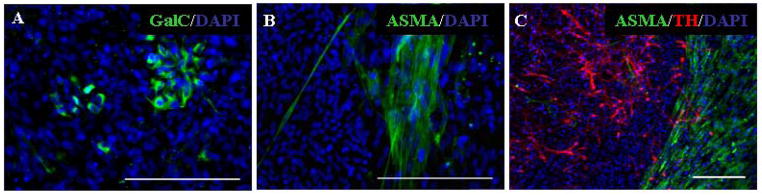

We previously identified approximately 90% of the cell population as neuronal and glial cells as indicated by expression of MAP2 and GFAP respectively [36]. In an attempt to identify the remaining cell types in our cultures, we examined the expression of the oligodendritic marker GalC and found that only a small number of cells (<1%) differentiated into GalC+ cells (Fig. 2A). Our previous investigations demonstrated ASMA positive cells of mesodermal origin in brain grafts from transplanted hESC after differentiation in PA6 co-cultures [41]. Therefore, we also investigated the potential of hESC to differentiate into cells of mesodermal lineage by using an antibody against ASMA. The hESC generated a small subpopulation (<5%) of smooth muscle cells in vitro, as judged by expression of ASMA and morphology (Fig. 2B). An interesting observation regarding the population of ASMA+ cells was their segregation from the cells of ectodermal origin. As shown in Figure 2C, the ASMA+ cells were situated outside the borders of rosettes or colonies containing large numbers of TH+ neurons.

Figure 2.

Cellular composition of differentiated cultures in feeder-free conditions. Marker expression in cultures after 19 additional days of differentiation in the presence of SHH, FGF8 and GDNF, following removal from the PA6 cell feeder layer. (A) Expression of the oligodendrocytic marker GalC. GalC+ cells comprised less than 1% of the cell population. (B) The mesodermal marker ASMA was expressed in a subpopulation of cells, but (I) was rare in colonies containing large numbers of TH+ cells and was rarely seen in close proximity to TH+ cells. Scale bars=200 μm.

Earlier investigation of differentiation of hESC towards dopaminergic and other neuronal phenotypes showed that about 80% of the MAP2+ cells co-expressed TH, whereas less than 1% of cells stained positive for GABA. Co-expression of TH and GABA or expression of dopamine β-hydroxylase (DBH), was not detected [36]. To search for other neuronal phenotypes that would account for the unidentified 20% of MAP2+ neurons, we immunostained for the neurotransmitter markers choline acetyltransferase (ChAT), glutamate, and serotonin (5-HT), and found that these markers were not expressed. This may relate to limitations of the immunocytochemical detection of neurotransmitter markers, immaturity of the remaining MAP2+ neurons, or the presence of cells with other neurotransmitter phenotype.

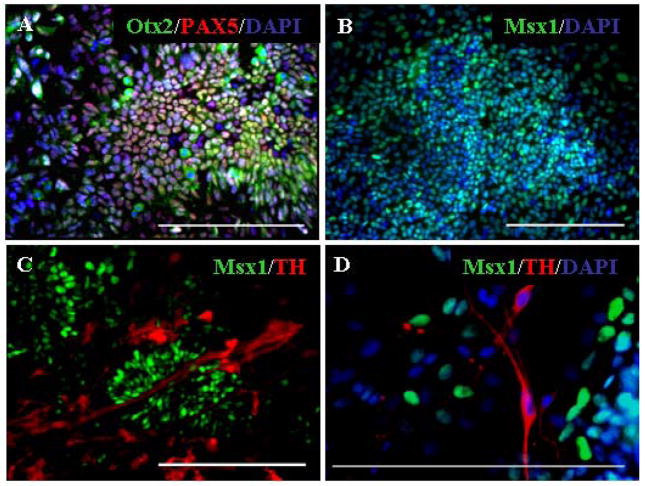

3.3. Midbrain specific nature of SDIA-derived neural progenitor cells

Dopaminergic neurons are present in the midbrain, hypothalamus, olfactory bulb, retina, and the carotid body/petrosal ganglion [12, 15]. Thus, dopaminergic cells positive for TH and negative for DBH are not restricted to the midbrain. To ascertain that the NPC isolated from PA6 cells were mesencephalic restricted NPC, we examined expression of the region-specific transcription factors Pax5, Otx2 and Msx1 to confirm midbrain dopaminergic lineage-specific differentiation.

As shown in Figure 3A and B, expression of Pax5, Otx2 and Msx1 was detected in the majority of cells within colonies recognizable as rosettes. After 12 days of differentiation, as the neural progenitor cells acquired their identity, Msx1 expression was attenuated in an increasing number of cells, and was absent from TH+ neurons (Fig. 3C, D).

Figure 3.

Expression of midbrain specific markers by isolated neural progenitor cells. Cells isolated from PA6 cell layers were differentiated for 7 days and examined for the expression of midbrain dopaminergic progenitor markers by immunostaining, using antibodies against (A) Otx2 and Pax5 and (B) Msx1. (C) After 12 days of differentiation the number of Msx1+ cells decreased and (D) Msx1 expression was absent from TH+ neurons. Scale bars=200 μm.

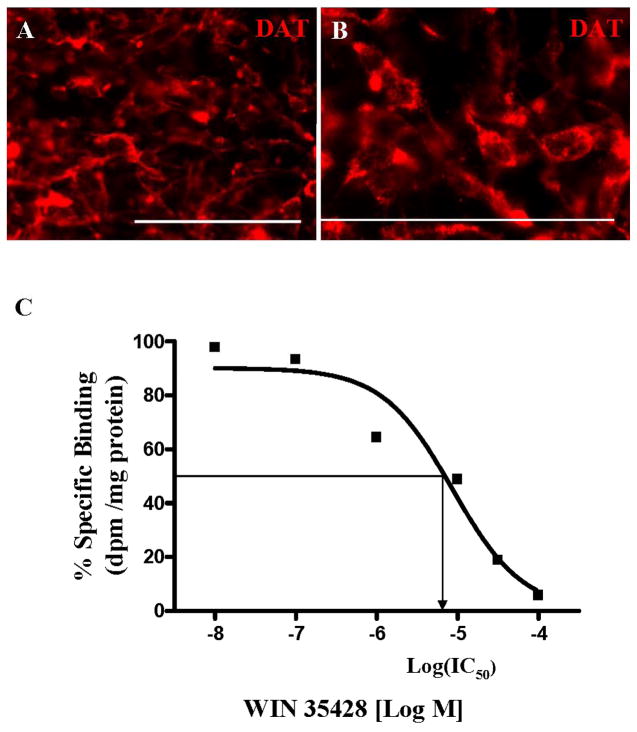

3.5. DAT immunostaining and [3H] WIN 35428 binding assay

DAT immunostaining showed expression within colonies containing cells resembling TH+ neurons, as judged by their morphology (Fig. 4A). As shown in Figure 4B, DAT immunoreactivity was seen mainly in the plasma membranes of cells with neuron-like morphology.

Figure 4.

Assessment of dopamine transporter (DAT) function and cell surface expression. (A, B) Illustration of DAT expression, mainly seen in plasma membranes, in terminally differentiated cultures by immunocytochemistry 18 days after isolation. (C) Saturation curve for [3H] WIN 35428 illustrating displacement binding inhibition values. The points represent the means of experimental data from three independent experiments. The IC50 was 8.66 uM. Scale bars=200 μm.

Dopaminergic neurons derived from hESC also exhibited DAT binding, indicated by specific binding of [3H] WIN 35428. As illustrated in Fig. 4C, the displacement of [3H] WIN 35428 by WIN 35428 was concentration-dependent. The concentration of unlabeled ligand that displaced half of the radioligand (IC50) was 7.82 ± 0.56 μM.

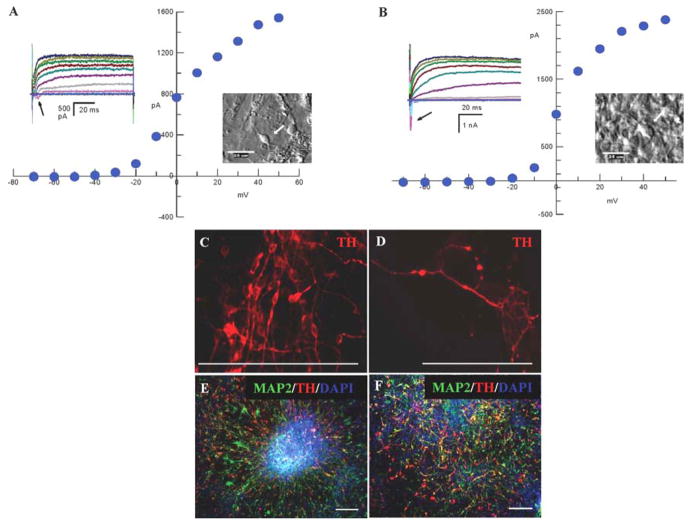

3.6. Electrophysiological characteristics of BG01V2-derived neurons

Voltage-clamp recordings were obtained from cells differentiated for 12 or 25 days after isolation from feeder cells. We assumed that the majority of cells recorded from were TH+ neurons based on their fusiform perikarya typical of dopaminergic neurons, and our prior studies showing TH expression in 80 ± 9% of cells with neuronal morphology [36]. At day 12, recordings were made from 14 neuronal cells. Two (14%) of these cells showed weak sodium currents (50–200 pA; Fig. 5A), although a majority (64%) showed the presence of the delayed rectifier at a wide range of expression (20 pA to > 1 nA). In contrast, recordings from three of 17 neuronal cells (18%) differentiated for 25 days displayed strong sodium currents (0.4 to 1.9 nA) and 47% showed outward rectification, most of which were strong (nA) (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Functional maturation of hESC-derived neurons in feeder free cultures. Examples of whole-cell currents obtained under voltage clamp conditions showing (A) weak sodium current with a clear delayed rectifier current in a relatively immature neuron at day 12, and (B) increased sodium currents and stronger outward rectification in a more mature neuron at day 25, as indicated by arrows. Cells were held at −60 mV and stepped in 10 mV increments for 100 ms from −70 to +50 mV. The cell from which the data presented were recorded is shown under Hoffman contrast as an inset to its current-voltage plot for each condition. Scale bars=25 μm. (C–F) Illustration of neurons in various stages of development in a culture at day 18 of differentiation. TH staining of (C) neurons with relatively immature unipolar or simple bipolar morphology lacking axonal and dendritic branching, as compared to (D) a mature neuron with fine extended processes. (E) The immature neurons were mostly found in colonies where radial neuronal migration was taking place whereas (F) mature neurons mainly resided in well-differentiated colonies. Scale bars=200 μm

Development of increased permeability to potassium during neuronal maturation was further manifested in terms of decreasing resting membrane potentials (RMP). The median RMP of cells differentiated for 12 days was −24 mV, whereas that of the more mature cells was −38 mV. The decreased RMP of cells examined at the later time point is likely due to further maturation of neuronal function, although these cells were selected on the basis of morphology and accessibility (they were not selected randomly), precluding statistical analysis of a difference between maturation phases. The morphology of the neuronal cells differed within cultures. As illustrated in Figure 7, immature neurons with unipolar or bipolar appearance (Fig. 5C), as well as mature multipolar neurons with widespread axonal terminal arborization (Fig. 5D) were detected in a culture differentiated for 18 days in the feeder free condition. Immature neurons were primarily found in rosettes where neural radial migration was taking place (Fig. 5E), whereas mature neurons were found in more completely differentiated rosettes lacking a radial structure (Fig. 5F).

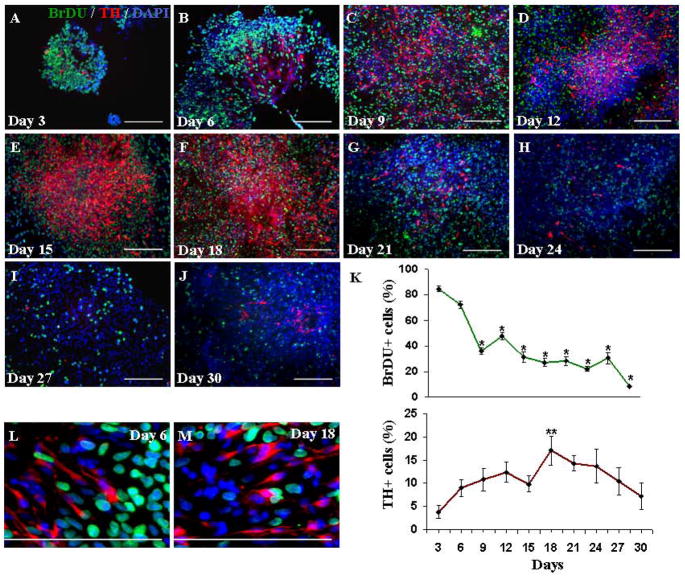

3.7. Proliferation of isolated neural progenitor cells

To assess the relationship between proliferating cells and TH+ neurons, hESC were co-cultured with PA6 cells for 10 days, followed by enzymatic isolation. The cultures were analyzed for BrDU incorporation every 3 days. TH+ neurons could be detected as early as 3 days after subculture. The majority of cells at this time exhibited cell division as indicated by BrDU incorporation (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6.

Examination of proliferation capacity of isolated neural progenitor cells and viability of TH+ neurons derived from hESC. (A–J) Simultaneous detection of BrDU incorporation and expression of TH in isolated neural progenitor cells every 3 days during 30 days of culture. TH+ neurons appeared 2–3 days after isolation from the PA6 feeder layers (A). BrDU incorporation showed a gradual decline over time, while the number of TH+ neurons increased and reached a maximum at approximately 18 days (F). At day 30 proliferation ceased in the majority of cells, as shown in panel (J). (K) Line graph illustrating the relationship between the mean values of percentages of BrDU-labeled (green line) and TH+ (red line) cells as a function of time (means ± SEM). The overall effect of time was statistically significant for the BrDU+ cells (P <0.0001) and TH+ neurons ( P= 0.0287). In addition, percentages of BrDU+ cells at days 9–30 versus day 3 were significantly different (P <0.001). The percentage of TH+ neurons was significantly different (P <0.05) at day 18 versus day 3. *=P<0.001, **=P<0.05. High magnification views of cells within colonies differentiated for (L) 6 days and (M) 18 days, demonstrating the lack of BrDU incorporation in TH+ neurons, indicating that the TH+ cells are in a post-mitotic state. Scale bars=200 μm.

BrDU incorporation showed a gradual decline over time, while the number of TH+ neurons reached a maximum at approximately day 18 (Fig. 6A–J). At day 18, many BrDU+ cells were still seen in the center as well as the periphery of the colonies (Fig. 6F). By 30 days after isolation from the feeder cells, proliferation ceased in 91 ± 0.4 % of cells (Fig. 6J). Figure 6K shows percentages of BrDU+ (green line) and TH+ (red line) cells at the indicated time points during 30 days of culture. Notably, co-localization of BrDU with cells expressing TH could not be detected at any time point (Fig. 6 L, M). The percentage of TH+ neurons at day 18 in the BrDU assay was only 17 ± 3%, as compared to the 34 ± 6% found in our earlier study. To test whether the procedure for BrDU double staining was responsible for decreasing the number of detected TH+ cells, and to exclude the possibility of the presence of undetected TH+ cells with incorporated BrDU, we repeated the cell proliferation assay and quantified the percentages of TH+ cells in cultures with or without BrDU staining after 18 days of differentiation. In this set of experiments we found that the detection of TH+ cells was not altered by BrDU staining. The percentage of TH+ cells was 27± 5 in cultures co-stained with BrDU and 25± 8 in cultures that did not receive BrDU treatment. Therefore, differences between percentages between TH+ cells in the BrDU assay as compared to our previous report are most likely due to differences in passage number, cell density, or other differences between preparations.

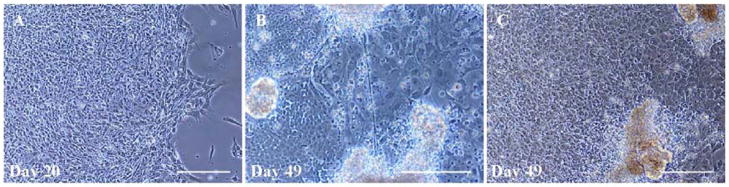

In long-term cultures (35–56 days), cells exhibited more characteristic morphological features of mature neurons, including extensive process outgrowth (Fig. 7B), as compared to cells at earlier time points (Fig. 7A). After 7 weeks, cell viability was significantly decreased (Fig. 7C). Long-term monitoring of the cultures did not show signs of transition of any cell type to tumor-like colonies with uncontrolled growth.

Figure 7.

Long-term monitoring of BG01V2- derived cultures. (A) Phase-contrast image of a colony 20 days after isolation. (B) A colony in long-term culture (49 days), showing process outgrowth from well-differentiated neurons, establishing a network of connections between adjacent colonies. (C) Cell death was significantly increased in long-term cultures, as shown by accumulation of cell debris. Scale bars=200 μm.

Discussion

We demonstrate here that TH-expressing neurons derived from a variant of a hESC are post-mitotic and show phenotypic characteristics of midbrain dopaminergic neurons. We employed the SDIA method to generate dopaminergic neurons from a variant of BG01, here termed BG01V2, which carries a chromosome 17 trisomy.

It has repeatedly been observed that long-term maintenance of hESC can cause chromosomal abnormalities. The cause of such genetic alternations in hESC is not fully understood, but has been associated with adaptation to in vitro culture, offering the mutated hESC advantages such as growth and survival [6, 13]. Interestingly, several laboratories have reported the gain of chromosome 17 as one of the most common alterations in late passages of hESC [6, 7, 11, 21, 22, 39]. Recent publications have discussed possible candidate genes on this chromosome involved in adaptation of hESC to in vitro culture. BIRC5(survivin), an inhibi tor of apoptosis is among these genes, and is selectively over-expressed in common human cancers [5, 34].

Several studies have claimed that development of karyotypic abnormalities in hESC can be prevented by mechanical passaging instead of the use of enzymes for extended passaging [7, 23]. Other studies have investigated the genetic integrity of several hESC lines under feeder-free conditions and demonstrated that prolonged propagation does not lead to chromosomal aberrations [2, 29, 40]. Although the karyotype for all lines appeared stable, more detailed microarray analysis revealed differences in the expression of small subsets of genes in cultures maintained for long periods of time [29]. Another study has reported the development of copy number aberrations, mitochondrial DNA mutations, and promoter methylation in late passage hESC [21].

Classical G-band karyotyping is often used to analyze hESC lines, but provides only a low-resolution overview of the genome. There are undoubtedly more subtle differences between strains of hESC lines described in various studies of differentiation of hESC to specific cell types, perhaps resulting from unknown mutations. Thus, differences between published studies involving differentiation of presumably normal hESC towards various cell types are difficult to interpret. High resolution DNA analysis, detecting gene alterations and mutations would have to be used in order to evaluate the genetic stability of hESC lines and to compare various strains and passage numbers of hESC.

Previously, we illustrated that BG01V2 differentiated on PA6 cells for 10–12 days mainly gave rise to neurons (46 ± 8%) and glia (44 ± 13%), where the percentage of TH+ cells was 34 ± 6. Here we found that a subpopulation (<5%) of cells were of mesodermal origin, as shown by expression of ASMA. A small number of oligodendritic cells (<1%), expressing GalC and were also found in the cultures.

The isolated NPC were differentiated in the presence of SHH and FGF8. These molecules are considered to have a critical role in early cell fate specification of midbrain dopaminergic neurons [17, 31, 38]. Additional regulatory genes have been identified as being required for the generation of mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons, particularly Pax2, Pax5, Otx2 and Msx1 [3, 32, 33, 35, 37]. Pax5 homozygous mutant mice showed complete loss of the posterior midbrain and cerebellum [35]. Recent studies have identified a role of Otx2 in regulating neuronal subtype identity and neurogenesis in midbrain dopaminergic neurons [27, 28, 37]. Lmx1a and Msx1 are critical intrinsic dopamine neuron determinants [3], and midbrain dopaminergic development was found to be abnormal in Msx1 knockout mice [16].

Here we report that neural progenitor cells generated by SDIA are restricted to a midbrain dopaminergic phenotype, evidenced by expression of Pax5, Otx2 and Msx1. The dopaminergic nature of the TH+ neurons was further supported by expression of the dopamine transporter. Functional DAT activity was confirmed by competitive DAT binding experiments. The IC50 value from the binding assay was in the micromolar range. Other studies using dopaminergic neurons derived from rodent mesencephalic progenitor cells have also reported DAT binding of low affinity (Kd > 1μM). In contrast, hDAT-transected N2A neurons and COS-7 cells displayed much higher binding affinities [43]. A possible explanation for our result may be that the binding affinity of dopamine analog to DAT is dependent on the degree of neuronal maturation. As previously illustrated, dopaminergic cells at various stages of differentiation were present in the cultures, and the electrophysiological studies demonstrated that a subset of these cells were not fully mature neurons.

Electrophysiological recordings showed that sodium currents contributing to membrane excitability were present at early stages of differentiation (i.e., 12 days after isolation), but seemed to increase in magnitude in cells differentiated for 25 days, indicating progressive neuronal maturation. Resting membrane potentials of cells were variable within cultures. However, resting membrane potentials tended to become more negative as a function of time in culture. These observations are consistent with several studies demonstrating maturation of neuronal cells as a function of insertion and clustering of voltage-dependent sodium channels [9, 10, 18].

We also evaluated cell proliferation of the isolated NPC by BrDU incorporation while monitoring the generation of TH+ neurons during 30 days of culture. There was a significant decrease in numbers of dividing cells after 30 days of culture. TH+ cells were post-mitotic at all stages of differentiation.

We further examined cell growth rate and viability in long-term cultures. We did not observe any colonies with uncontrolled cell proliferation, indicating the absence of tumor cells in these cultures.

We conclude that TH+ neurons derived from BG01V2, a hESC line carrying a trisomy of chromosome 17, can be induced to differentiate to cells with biochemical, morphological, and electrophysiological characteristics of midbrain dopaminergic neurons. The molecular mechanisms underlying the subtype and regional specification of dopaminergic neurons are still under investigation. Models allowing a large fraction of the total cells to develop into dopaminergic neurons are likely to be useful for examining the pathways responsible for dopaminergic induction from hESC, and for overcoming obstacles involved in cell transplant-related research.

Acknowledgments

Research supported by the Intramural Research Program of NIDA, NIH, DHHS.

References

- 1.Ambrosini G, Adida C, Altieri DC. A novel anti-apoptosis gene, survivin, expressed in cancer and lymphoma. Nat Med. 2007;3:917–921. doi: 10.1038/nm0897-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amit M, Shariki C, Margulets V, Itskovitz-Eldor J. Feeder layer- and serum-free culture of human embryonic stem cells. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:837–845. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.021147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersson E, Tryggvason U, Deng Q, Friling S, Alekseenko Z, Robert B, et al. Identification of intrinsic determinants of midbrain dopamine neurons. Cell. 2006;124:393–405. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrews PW. The selfish stem cell. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:325–326. doi: 10.1038/nbt0306-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azuhata T, Scott D, Takamizawa S, Wen J, Davidoff A, Fukuzawa M, et al. The inhibitor of apoptosis protein survivin is associated with high-risk behavior of neuroblastoma. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:1785–1791. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2001.28839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker DE, Harrison NJ, Maltby E, Smith K, Moore HD, Shaw PJ, et al. Adaptation to culture of human embryonic stem cells and oncogenesis in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:207–215. doi: 10.1038/nbt1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brimble SN, Zeng X, Weiler DA, Luo Y, Liu Y, Lyons IG, et al. Karyotypic stability, genotyping, differentiation, feeder-free maintenance, and gene expression sampling in three human embryonic stem cell lines derived prior to August 9, 2001. Stem Cells Dev. 2004;13:585–597. doi: 10.1089/scd.2004.13.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buzzard JJ, Gough NM, Crook JM, Colman A. Karyotype of human ES cells during extended culture. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:381–382. doi: 10.1038/nbt0404-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Couraud F, Martin-Moutot N, Koulakoff A, Berwald-Netter Y. Neurotoxin-sensitive sodium channels in neurons developing in vivo and in vitro. J Neurosci. 1986;6:192–198. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-01-00192.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dargent B, Couraud F. Down-regulation of voltage-dependent sodium channels initiated by sodium influx in developing neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:5907–5911. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Draper JS, Smith K, Gokhale P, Moore HD, Maltby E, Johnson J, et al. Recurrent gain of chromosomes 17q and 12 in cultured human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:53–54. doi: 10.1038/nbt922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finley JC, Polak J, Katz DM. Transmitter diversity in carotid body afferent neurons: Dopaminergic and peptidergic phenotypes. Neuroscience. 1992;51:973–987. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90534-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grandela C, Wolvetang E. hESC adaptation, selection and stability. Stem Cell Rev. 2007;3:183–191. doi: 10.1007/s12015-007-0008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanson C, Caisander G. Human embryonic stem cells and chromosome stability. APMIS. 2005;113:751–755. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2005.apm_305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hökfelt T, Martensson R, Björklund A, Kleinau S, Goldstein M. Distributional maps of tyrosine-hydroxylase-immunoreactive neurons in the rat brain. In: Björklund A, Hökfelt T, editors. Handbook of Chemical Neuroanatomy. Vol. 2. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1984. pp. 277–379. Classical transmitters in the CNS, Part I. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Houzelstein D, Cohen A, Buckingham ME, Robert B. Insertional mutation of the mouse Msx1 homeobox gene by an nlacZ reporter gene. Mech Dev. 1997;65:123–133. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(97)00065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hynes M, Rosenthal A. Specification of dopaminergic and serotonergic neurons in the vertebrate CNS. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1999;9:26–36. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(99)80004-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaplan MR, Cho MH, Ullian EM, Isom LL, Levinson SR, Barres BA. Differential control of clustering of the sodium channels Na(v)1.2 and Na(v)1.6 at developing CNS nodes of Ranvier. Neuron. 2001;30:105–119. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00266-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawasaki H, Mizuseki K, Nishikawa S, Kaneko S, Kuwana Y, Nakanishi S, et al. Induction of midbrain dopaminergic neurons from ES cells by stromal cell-derived inducing activity. Neuron. 2000;28:31–40. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin LF, Doherty DH, Lile JD, Bektesh S, Collins F. GDNF: A glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor for midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Science. 1993;260:1130–1132. doi: 10.1126/science.8493557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maitra A, Arking DE, Shivapurkar N, Ikeda M, Stastny V, Kassauei K, et al. Genomic alterations in cultured human embryonic stem cells. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1099–1103. doi: 10.1038/ng1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitalipova MM, Rao RR, Hoyer DM, Johnson JA, Meisner LF, Jones KL, et al. Preserving the genetic integrity of human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:19–20. doi: 10.1038/nbt0105-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moon SY, Park YB, Kim DS, Oh SK, Kim DW. Generation, culture, and differentiation of human embryonic stem cells for therapeutic applications. Mol Ther. 2006;13:5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pal R, Khanna A. Similar pattern in cardiac differentiation of human embryonic stem cell lines, BG01V and ReliCellhES1, under low serum concentration supplemented with bone morphogenetic protein-2. Differentiation. 2007;75:112–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2006.00123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perrier AL, Tabar V, Barberi T, Rubio ME, Bruses J, Topf N, et al. Derivation of midbrain dopamine neurons from human embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:12543–12548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404700101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Plaia TW, Josephson R, Liu Y, Zeng X, Ording C, Toumadje A, et al. Characterization of a new NIH-registered variant human embryonic stem cell line, BG01V: a tool for human embryonic stem cell research. Stem Cells. 2006;24:531–546. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puelles E, Annino A, Tuorto F, Usiello A, Acampora D, Czerny T, et al. Otx2 regulates the extent, identity and fate of neuronal progenitor domains in the ventral midbrain. Development. 2004;131:2037–2048. doi: 10.1242/dev.01107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Puelles E, Acampora D, Lacroix E, Signore M, Annino A, Tuorto F, et al. Otx dose-dependent integrated control of antero-posterior and dorso-ventral patterning of midbrain. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:453–460. doi: 10.1038/nn1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosler ES, Fisk GJ, Ares X, Irving J, Miura T, Rao MS, et al. Long-term culture of human embryonic stem cells in feeder-free conditions. Dev Dyn. 2004;229:259–274. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roussa E, Krieglstein K. GDNF promotes neuronal differentiation and dopaminergic development of mouse mesencephalic neurospheres. Neurosci Lett. 2004;361:52–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.12.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roussa E, Krieglstein K. Induction and specification of midbrain dopaminergic cells: focus on SHH, FGF8, and TGF-beta. Cell Tissue Res. 2004;318:23–33. doi: 10.1007/s00441-004-0916-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwarz M, Alvarez-Bolado G, Urbánek P, Busslinger M, Gruss P. Conserved biological function between Pax-2 and Pax-5 in midbrain and cerebellum development: evidence from targeted mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14518–14523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simon HH, Bhatt L, Gherbassi D, Sgadó P, Alberí L. Midbrain dopaminergic neurons: determination of their developmental fate by transcription factors. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2003;991:36–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Storlazzi CT, Brekke HR, Mandahl N, Brosjö O, Smeland S, Lothe RA, et al. Identification of a novel amplicon at distal 17q containing the BIRC5/SURVIVIN gene in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours. J Pathol. 2006;209:492–500. doi: 10.1002/path.1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Urbánek P, Fetka I, Meisler MH, Busslinger M. Cooperation of Pax2 and Pax5 in midbrain and cerebellum development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5703–5708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vazin T, Chen J, Lee CT, Amable R, Freed WJ. Assessment of stromal-derived inducing activity in the generation of dopaminergic neurons from human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2008 doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0039. online April 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vernay B, Koch M, Vaccarino F, Briscoe J, Simeone A, Kageyama R, et al. Otx2 regulates subtype specification and neurogenesis in the midbrain. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4856–4867. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5158-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang MZ, Jin P, Bumcrot DA, Marigo V, McMahon AP, Wang EA, et al. Induction of dopaminergic neuron phenotype in the midbrain by Sonic hedgehog protein. Nat Med. 1995;1:1184–1188. doi: 10.1038/nm1195-1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xiao L, Yuan X, Sharkis SJ. Activin A maintains self-renewal and regulates fibroblast growth factor, Wnt, and bone morphogenic protein pathways in human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1476–1486. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu C, Inokuma MS, Denham J, Golds K, Kundu P, Gold JD, et al. Feeder-free growth of undifferentiated human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:971–974. doi: 10.1038/nbt1001-971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zeng X, Cai J, Chen J, Luo Y, You ZB, Fotter E, et al. Dopaminergic differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2004;22:925–940. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-6-925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zeng X, Chen J, Liu Y, Luo Y, Schulz TC, Robins AJ, et al. BG01V: A variant human embryonic stem cell line which exhibits rapid growth after passaging and reliable dopaminergic differentiation. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2004;22:421–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang L, Elmer LW, Little KY. Expression and regulation of the human dopamine transporter in a neuronal cell line. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1998;59:66–73. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(98)00138-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]