Abstract

Introduction

Persons carrying mutations for hereditary cancer syndromes are at high risk for the development of tumors at an early age, as well as the synchronous or metachronous development of multiple tumors of the corresponding tumor spectrum. The genetic causes of many hereditary cancer syndromes have already been identified. About 5% of all cancers are part of a hereditary cancer syndrome.

Methods

Selective literature review, including evidence-based guidelines and recommendations.

Results

Clinical criteria are currently available according to which many hereditary cancer syndromes can be diagnosed or suspected and which point the way to further molecular genetic analysis. A physician can easily determine whether these criteria are met by directed questioning about the patient’s personal and family medical history. The identification of the causative germ line mutation in the family allows confirmation of the diagnosis in the affected individual and opens up the option of predictive testing in healthy relatives.

Discussion

Mutation carriers for hereditary cancer syndromes need long-term medical surveillance in a specialized center. It is important that these persons should be identified in the primary care setting and then referred for genetic counseling if molecular genetic testing is to be performed in a targeted, rational manner.

Keywords: cancer syndromes, monogenic diseases, molecular genetic diagnostics, genetic counseling, surveillance

Hereditary cancer syndromes are encountered in all medical specialties. Although they account for only about 5% of all malignancies (1), it is nevertheless important to identify these patients because—unlike patients with sporadic cancers—they require special, long-term care. Every physician will see such patients during his career. Also important are the management of relatives and the provision of information to family members, who may also have an increased cancer risk. Both the physician in the relevant specialty and a human geneticist therefore have the task of informing patients in detail about their clinical condition, the risks for the patients themselves and for other family members and about the specific screening examinations (2). These patients should always be referred to a specialized center if a hereditary cancer syndrome is suspected.

This article is intended to equip the reader to achieve especially the following learning goals relating to hereditary cancer syndromes:

Become familiar with the main clinical features of several major cancer syndromes

Understand the differences between hereditary and nonhereditary cancers

Recognize the signs of a hereditary cancer and know when further diagnostic evaluations are indicated.

The methodological basis of this paper was a selective literature review primarily in the databases GeneReviews (www.genetests.org) and Orphanet (www.orpha.net), while for certain aspects a specific search for articles was conducted in Medline (via Pubmed).

Causes of hereditary cancer syndromes

Hereditary cancer syndromes.

The management of patients with hereditary cancer syndromes requires interdisciplinary cooperation between the respective specialty and human geneticists at specialized centers.

A hereditary cancer syndrome is present when a person, because of an inherited mutation, has an increased risk of developing certain tumors which can already develop at a relatively early age. In most known hereditary malignant syndromes the elevated cancer risk is due to a mutation of a single gene (monogenic hereditary diseases). The affected genes concerned usually have a controlling function on the cell cycle or the repair of DNA damage. Sporadically occurring, i.e., nonhereditary tumors are also caused by an increased incidence of mutations in these genes. In these cases, however, the genetic changes have newly developed in the cells of the tissue concerned (somatic mutations) and are not present in the other cells of the body.

Definition of somatic mutations.

Mutations in individual body cells, but not in the germ cells. The mutations only have effects on the body cells concerned and are therefore not transmitted to progeny.

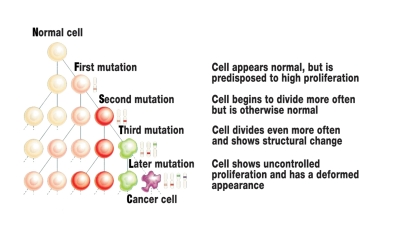

Most hereditary cancers are associated with a "germline mutation" which has entered the zygote via the egg cell or sperm and is consequently present in every cell of the later human body. The first step in the development of cancer has thus already been taken in every cell. This explains why patients with a hereditary tumor syndrome become ill more frequently and often at a younger age. Malignant degeneration occurs when further somatic mutations implicated in the development of cancer occur in genes of individual body cells throughout the mitotic cycles (figure 1) (3).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of cancer etiology. Sporadic tumors develop from originally "normal" body cells due to an increased incidence of somatic mutations during the cell divisions. Mutation carriers for a hereditary cancer syndrome already have a mutation in every body cell (germline mutation), the pathway to the cancer cell is thereby shortened. For cancer to develop, however, here too further somatic mutations have to occur during the cell mitoses. The diagram shortens this protracted multi-step process to only a few cell generations. Modified from: Cavenee WK and White RL: Anhäufung genetischer Defekte bei Krebs. In: Spektrum der Wissenschaft 5/1995, 41

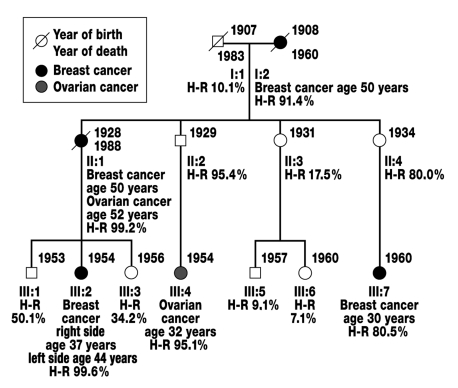

Most hereditary cancer syndromes follow autosomal-dominant inheritance in which the patient’s first-degree relatives (parents, children, and siblings) have a 50% risk of carrying the causative mutation themselves (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Family with suspected autosomal-dominant hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. Roman numerals indicate the generations (I-III), arabic numerals the persons (1–7) in the generations. Squares symbolize male persons, circles female persons. Taking into account the incomplete penetrance of the disease and age, the risk of being a mutation carrier for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (heterozygotic risk/H-R) was calculated for each family member using the Cyrillic 2.1 computer program. On the assumption that it is a hereditary form of breast and ovarian cancer, persons II:2 and II:4 are obligate mutation carriers for the disease, since their daughters (III:4 and III:7) are affected by the disease.

Each hereditary cancer syndrome has a certain characteristic spectrum of tumors. An entire series of genes are known whose changes can cause a hereditary cancer syndrome (table 1). Presumably there are also other, still undiscovered causative genes. Since malignancies are very common in the population and screening for mutations is demanding, the indication for molecular genetic analysis must be carefully considered (4). Clinical criteria for a genetic analysis have therefore been established for every form of cancer.

Table 1. Hereditary cancer syndromes with increased malignancy risk.

| Hereditary cancer syndrome | Gene | Incidence*1 | Narrower tumor spectrum |

| Autosomal-dominant inheritance | |||

| Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) | MSH2 | approx. 1:500*2 | Colon, endometrial, gastric, small intestine, urothelial cancer etc. |

| MLH1 | |||

| MSH6 | |||

| PMS2 | |||

| Familial breast and ovarian cancer | BRCA1 | 1:500 to 1:1000 | Breast, ovarian, and prostate cancer |

| BRCA2 | |||

| Neurofibromatosis type 1 | NF1 | 1:3000 | Neurofibroma, optic nerve glioma, neurofibrosarcoma |

| Familial retinoblastoma | RB1 | 1:15 000 to 1:20 000 | Often bilateral retinoblastoma in childhood, later secondary tumors |

| Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN2a) | RET | 1:30 000 | Medullary thyroid cancer, pheochromocytoma, hyperparathyroidism |

| Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) | APC | 1:33 000 | >100 colonic adenomas, tumors in upper gastrointestinal tract, desmoids |

| Von Hippel-Lindau disease | VHL | 1:36 000 | Clear cell renal cell cancer and other, usually benign tumors |

| Li-Fraumeni syndrome | TP53 | rare*3 | Particularly broad tumor spectrum incl. sarcomas, breast cancer, brain tumors, leukemia |

| Autosomal-recessive inheritance | |||

| MUTYH-associated polyposis (MAP) | MUTYH | No data | Colon cancer, colonic adenoma |

| Ataxia teleangiectatica | ATM | 1:40 000 to 1:100 000 | Non-Hodgkin lymphoma,leukemia |

| Fanconi anemia | FANC | 1:100 000 | Hematological neoplasms |

| A-H | |||

*1 The frequency data relate to the number of mutation carriers in the general population.

*2 About 2% to 3% of all colon cancers, from which the incidence is estimated.

*3 Worldwide fewer than 400 families described.

Source: www.GeneReviews.org

Anamnestic evidence of hereditary cancer syndromes

Definition of germline mutations.

The mutations affect egg cells or sperms and are transmitted via mitosis to the daughter cells.

They can be transmitted to progeny through the germline.

Some hereditary cancer syndromes can be diagnosed on the basis of the endoscopic findings, for example in the typical cases of familial adenomatous polyposis. In many cases, however, identifying these conditions is more difficult. The following special features may point to the presence of a hereditary cancer syndrome: several tumors developing in one patient, whether synchronously or metachronously, bilateral occurrence, unusually early age of disease onset, other relatives affected. In these cases it is useful to refer the patient and his/her relatives for closer evaluation to a human geneticist who will then, if necessary, institute further diagnostic procedures and offer individually adapted recommendations for screening and early diagnostic testing. The targeted examinations may facilitate early cancer diagnosis and, if necessary, the removal of precursor stages of cancer, thereby improving the prognosis. A list of human genetic advisory centers is provided on the home page of the Association of German Human Geneticists (www.bvdh.de).

Predictive diagnostics and early detection

Identification of the causative mutation in a cancer patient offers his/her relatives the possibility of a reliable predictive diagnosis. This means that the at-risk family members ("risk persons") can be screened for the presence of the mutation to establish whether or not they have inherited the increased cancer risk (mutation carrier or non–mutation carrier). With the aim of significantly improving the prognosis of the persons concerned, mutation carriers are enrolled in a specific surveillance program for the relevant cancer syndrome. Non–mutation carriers, on the other hand, can be discharged from intensified cancer screening. Large prospective studies on the effectiveness of existing early detection programs are ongoing and have already delivered initial evidence of the benefits of intensified screening (5, 6). If no underlying mutation can be identified in a family, predictive testing of relatives is not possible.

Several typical hereditary cancer syndromes are now considered as examples. Selection criteria were a high risk of malignancy and the availability of an early detection program allowing effective treatment of the tumors. Also included is the relatively rare Li-Fraumeni syndrome as an important differential diagnosis for several known cancer syndromes.

Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer

The annual number of new cases of colon cancer in Germany is estimated at above 37 000 for men and around 36 000 for women (7). About 3% of these cases—i.e., almost 2200 diseases—involve one of the hereditary colon cancer predisposition syndromes.

HNPCC (hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer / Lynch syndrome) is the commonest cause of hereditary colorectal cancers. Characteristic of the autosomal-dominant hereditary syndrome is the early occurrence of preferentially right-sided colorectal carcinomas, often synchronous and metachronous, cancers in the endometrium, renal pelvis/efferent urinary tract, small intestine, and in the stomach, ovaries, bile ducts, brain, and skin (8, 9). The penetrance of the disease, i.e. the likelihood of a mutation carrier developing a malignant tumor during his/her lifetime is about 80% to 90% (8). Roughly every 500th member of the general population is a mutation carrier for HNPCC (10).

Inheritance and its risks of repetition.

Autosomal-dominant (risk of repetition for direct progeny [children] 50%)

Autosomal-recessive (risk of repetition for siblings 25%)

The diagnosis of HNPCC is made clinically if the Amsterdam II criteria are fulfilled in the family (box 1) (9). Since many families cannot meet these strict criteria because of their small number of members and the incomplete penetrance of the disease, however, the revised Bethesda guidelines were additionally established (11).

Box 1. Clinical diagnostic criteria for HNPCC, all criteria must apply*1.

At least three family members with histologically confirmed colorectal cancer or cancer of the endometrium, small intestine, ureter or renal pelvis, one of whom is a first-degree relative of the two others; familial adenomatous polyposis must be ruled out

At least two successive generations affected

Diagnosis before age 50 years in at least one patient

*1based on the Amsterdam II Criteria (9)

Indicators for the presence of hereditary cancer syndromes.

Increased incidence of tumors in a person or family

Bilateral occurrence of tumors

Early age of disease onset, increased tendency to cancers from a certain tumor spectrum

These features may indicate the presence of HNPCC, but are not conclusive. For practical use, simplified suspicious clinical signs may be derived from them which represent the indication for a molecular pathogenic screening for HNPCC (box 2).

Box 2.

Indications for further molecular pathological diagnostic evaluation for HNPCC*1

-

Further genetic diagnostic evaluation for HNPCC should be performed in the following cases:

Patients with colon cancer before age 50 years

Patients with a history of two or more HNPCC-associated tumors

Patients with colon cancer who have at least one first-degree relative with an HNPCC-associated tumor before age 50 years

Patients with colon cancer who have at least two relatives with an HNPCC- associated tumor

Patients with colorectal adenomas before age 40 years without evidence of polyposis disease

Persons with a first-degree relative who satisfies one of the first five criteria

*1modified from the Bethesda and revised Bethesda criteria (11, 12)

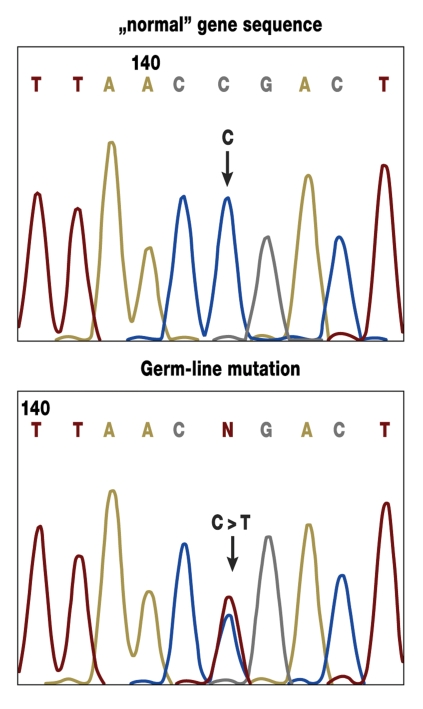

So far 4 of the genes that are mutated in HNPCC are known (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2). These genes carry information for proteins that are important for the repair of defects in the replication of DNA (mismatch repair genes) (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Example of evidence of a mutation in the MSH2 gene in molecular genetic diagnostics (direct sequencing in lymphocyte DNA). The upper diagram shows the unchanged sequence; the lower diagram shows a base exchange (C > T) in the form of a germline mutation in a gene copy.

Predictive diagnostics.

Screening of a healthy person for mutation carrier status

Determination of the risk of disease

Evidence of a DNA repair defect is provided by an analysis of the tumor tissue, which is the first diagnostic step. Two methods are available for this purpose (immunohistochemical staining and analysis for microsatellite instability). If the tumor finding is abnormal, a change in one of the genes mentioned is probable, and a search for mutations is therefore relevant. At present, however, the underlying mutation cannot be found in all cases; it is therefore speculated that further, still unidentified genes are etiologically implicated. If the tumor tissue offers no sign of a DNA repair defect however, a search for mutations will probably be unproductive.

Because of the high cancer risk, HNPCC patients are recommended to undergo a systematic surveillance program (table 2) (13). As long as the familial germline mutation cannot be ruled out in a risk person, then this individual should be referred for the same early detection program.

Table 2. Cancer surveillance program for HNPCC based on the study protocol of the German Cancer Aid joint research project "Familial Colon Cancer".

| Beginning | Examination | Frequency |

| From age 25 years (or earlier if very early disease onset in family, i.e. 5 years before earliest age of disease onset in family) | Physical examination | Once annually |

| Abdominal ultrasonography | Once annually | |

| Complete colonoscopy | Once annually | |

| Gynecological examination for endometrial and ovarian cancer (transvaginal sonography) | Once annually | |

| From age 35 years | Gastroscopy | Once annually |

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP)

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) is typically characterized by the development of hundreds to thousands of adenomatous polyps throughout the colon. Adenoma growth usually begins in the second decade in the rectosigmoid. If untreated, patients die from cancer on average at age 40 years.

Besides classical FAP, there is also a milder disease course (attenuated FAP, AFAP), in which patients usually develop fewer than 100 adenomas; disease onset is usually also 10 to 15 years later than in classical FAP. The adenomas are often localized in the proximal colon. Some of the patients are also seen to have extracolonic tumors, especially adenomas in the gastric fundus, osteomas of the mandible and maxilla and the long tubular bones as well as desmoid tumors (in about 13% of cases). Pathognomic for the disease is the characteristic "congenital hypertrophy of retinal pigment epithelium (CHRPE)" which is present in about 85% of patients but does not affect vision.

Diagnostic procedure for suspected HNPCC/Lynch syndrome.

Microsatellite analysis and immunohistochemical analysis of tumor tissue for abnormalities typical of HNPCC

Search for mutations in a blood sample if tumor tissue findings are pathological

The incidence of the disease in the general population is 1 : 33 000, the penetrance close to 100%. FAP is caused by a germline mutation in the tumor suppressor gene APC. 11% to 25% of cases are traceable to a mutation that has newly developed in the patient (14). According to the guidelines of the German Society of Digestive and Metabolic Diseases (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Verdauungs- und Stoffwechselerkrankungen, DGVS), persons at risk of FAP should undergo rectosigmoidoscopy annually from age 10 years onwards (15). The decision regarding surgery should be taken on the basis of the clinical findings. After rectum-sparing colectomy, the risk of developing rectal stump carcinoma is about 13% after 25 years (16). It was demonstrated in several studies that the risk for FAP patients of dying from colorectal cancer was markedly reduced by an intensive early detection program and prophylactic colectomy (6).

MUTYH-associated polyposis (MAP)

MAP is clinically comparable to attenuated FAP. The disease is caused by germline mutations and is one of the few cancer syndromes which has autosomal recessive inheritance. These patients accordingly have a germline mutation in the maternal and the paternal copy of the MUTYH gene. The possibility of MAP should be considered if a colorectal cancer is diagnosed at an early age in individual patients or in siblings whose parents are healthy and/or if 15 to 20 colonic adenomas are present. Extracolonic manifestations have been described only rarely to date (17).

Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer

According to the Epidemiological Cancer Registry of the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, approximately every twelfth woman develops breast cancer during her life (18). The suspicion of a hereditary disease is justified if women already become ill at a very early age or develop several tumors (bilateral breast or ovarian cancer, breast and ovarian cancer) or if several women with these diseases are present in one family. Operationalized criteria are applied in clinical practice (box 3).

Box 3. Inclusion criteria for mutation screening in genes BRCA1 and BRCA2*1.

-

A mutation search in genes BRCA1 and BRCA2 should be considered for the following familial constellations:

At least three women with breast cancer in the same line of a family

At least two women with breast cancer (one under 51 years of age) in the same line of a family

At least one woman with breast cancer and one woman with ovarian cancer in the same line of a family

At least two women in the same line of a family with the diagnosis of ovarian cancer

A man with breast cancer and one further person with breast or ovarian cancer in the same line of a family

-

Regardless of the family history, mutation screening should be performed for the following constellations:

At least one woman with both breast and ovarian cancer

A woman who developed bilateral breast cancer, with the first breast cancer before age 51 years

A women who was younger than 36 years at onset of breast cancer

*1 according to the German S3 guideline for the early detection of breast cancer (19)

The principal etiopathogenic factors for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer are changes in the genes BRCA1 and BRCA2. About 5% of breast cancers are due to a mutation in one of the two genes (19). Further genes have recently been identified, in which so far causative mutations for hereditary breast cancer have only been detected in individual cases. Carriers of a mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2 have a risk of up to 80% of developing breast cancer and of 20% to 40% of developing ovarian cancer during the course of their life (20, 21). Male mutation carriers generally do not become ill, but can transmit the mutation to their progeny. Male carriers of a BRCA1 mutation, however, have an increased risk of prostate cancer, while men with a BRCA2 mutation have an increased risk of breast cancer.

Differential diagnoses in adenomatous polyposis diseases.

Classical familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP)

Attenuated familial adenomatous polyposis (AFAP)

MUTYH-associated Polyposis (MAP)

A causative mutation in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene can only be detected in about 50% of the families in which there is a suspicion of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. If the presence of breast and ovarian cancer in a family is confirmed by the detection of a mutation or is very probable because of the family history, the risk persons in the family are recommended to have regular early detection screening to identify cancer at the earliest possible stage. Some women request bilateral ovariectomy or even mastectomy for cancer prevention. Based on the data from the multicenter study "Familial Breast and Ovarian Cancer" sponsored by the German Cancer Aid (Deutsche Krebshilfe), a general early detection program has been established which has been integrated in the S3 guidelines for early detection of breast cancer (19).

FAP and risk reduction.

FAP patients’ risk of dying from a colorectal carcinoma can be reduced by an intensified early detection program and prophylactic colectomy.

For early detection screening it is recommended to refer patients to one of the centers specializing in hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (for a list of centers in Germany please refer to the German-language website www.krebshilfe.de/brustkrebszentren.html).

Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN2)

Early detection program in risk persons for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer.

Regular self-examination, 6-monthly palpatory examination of the breast

Mammary sonography (6-monthly)

Annual mammography of the breast

Annual mammary MRI

MEN2 occurs in three subforms (22). Characteristic of type 2a is the increased incidence of medullary thyroid cancers (C cell carcinomas), pheochromocytomas, and hyperparathyroidism. In type 2b, medullary thyroid cancers can already occur in early childhood, as well as pheochromocytomas and mucosal neuromas of the lips and tongue. Affected individuals usually exhibit a marfanoid habitus and typical facial abnormalities with a long face, coarse features, and prominent lips. In the third subform of MEN2, familial medullary thyroid cancer, there is only an increased risk of medullary thyroid carcinoma.

Mutations in the RET protooncogene are responsible for all three subforms. The type and position of the mutation within the gene decide which form of MEN2 will result. Medullary thyroid cancers are relatively rare in the general population. Since it is so far estimated that about 25% to 33% develop in association with MEN2 (23), the diagnosis of a medullary thyroid cancer already represents an indication for a molecular genetic analysis for MEN2.

Because of the high risk of malignancy among mutation carriers, prophylactic thyroidectomy is usually recommended. When this is performed depends mainly on which mutation is present in the family. For carriers of a mutation for MEN2b, thyroidectomy is usually already recommended in early childhood because of the very early age of disease onset. For the other associated diseases, regular clinical screening should be performed.

Li-Fraumeni Syndrome

Characteristic of Li-Fraumeni syndrome is the high risk of malignant tumors already existing during childhood and early adulthood. These malignancies usually take the form of breast cancer, sarcomas and brain tumors, in children mainly leukemias and renal and adrenocortical cancers. Li-Fraumeni syndrome, however, has also been described as associated with an elevated risk of developing numerous other tumors (including melanomas, colon and pancreatic cancer).

In most families the factors responsible for the high cancer risk are germline mutations in the TP53 tumor suppressor gene, which may also be changed in sporadic tumors due to somatic mutations. The resulting protein (p53) plays a central role in controlling the cell cycle. The risk for carriers of a TP53 mutation of developing cancer during their lifetime is reported in the literature as 85% (24). These persons frequently develop multiple cancers in different organs. Since the tumor spectrum is very broad, there is at present no targeted early detection program for this syndrome. Women have the option of prophylactic mastectomy to reduce the high risk of breast cancer (25).

Conclusion

Multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) type 2.

The lead tumor is medullary thyroid cancer (C cell carcinoma). The narrower tumor spectrum comprises pheochromocytomas and hyperparathyroidism.

Indication for diagnostic evaluation for MEN type 2.

Indication for molecular genetic diagnostic evaluation for MEN type 2 is already the diagnosis of extramedullary thyroid cancer in a patient.

Li-Fraumeni syndrome.

The narrower tumor spectrum of Li-Fraumeni syndrome comprises breast cancer, sarcomas, and brain tumors, in children mainly leukemia and renal and adrenocortical cancers.

For HNPCC, FAP, MEN2a, and hereditary breast and ovarian cancer, the data available so far demonstrate that the existing early detection programs provide benefits for mutation carriers. It is therefore important to identify these persons at an early stage and enroll them in an appropriate screening program. This task devolves mainly upon primary care physicians. For further management, it is advisable to refer patients to a specialized center experienced in these relatively uncommon clinical entities.

Further Information.

This article has been certified by the North Rhine Academy for Postgraduate and Continuing Medical Education.

Deutsches Ärzteblatt provides certified continuing medical education (CME) in accordance with the requirements of the Chambers of Physicians of the German federal states (Länder). CME points of the Chambers of Physicians can be acquired only through the Internet by the use of the German version of the CME questionnaire within 6 weeks of publication of the article. See the following website: www.aerzteblatt.de/cme

Participants in the CME program can manage their CME points with their 15-digit "uniform CME number" (einheitliche Fortbildungsnummer, EFN). The EFN must be entered in the appropriate field in the www.aerzteblatt.de website under "meine Daten" ("my data"), or upon registration. The EFN appears on each participant’s CME certificate.

The solutions to the following questions will be published in volume 49/2008.

The CME unit "Emergencies Associated with Pregnancy and Delivery: Peripartum Hemorrhage" (volume 37/2008) can be accessed until 24 October 2008.

For volume 45/2008 we plan to offer the topic "Treatment of Depressive Disorders".

Solutions to the CME questionnaire in volume 33/2008:

Baum E, Peters G: The Diagnosis and Treatment of Primary Osteoporosis According to Current Guidelines: 1b, 2e, 3a, 4c, 5a, 6b, 7d, 8a, 9a, 10e

Please answer the following questions to participate in our certified Continuing Medical Education program. Only one answer is possible per question. Please select the answer that is most appropriate.

Question 1:

For which of the following patients is further testing for HNPCC indicated?

Patient with colorectal cancer at age 45 years

Patient with two colonic adenomas at age 63 years

Patient with colorectal cancer at age 53 years and a grandfather with a colorectal cancer at age 74 years

Patient with mandibular osteomas at age 66 years and with a malignant melanoma at age 83 years

Patient with colorectal cancer at age 53 years and bronchial cancer at age 58 years

Question 2:

Which of the following hereditary cancer syndromes has autosomal-recessive inheritance?

MEN2a

HNPCC

Attenuated FAP (AFAP)

MUTYH-associated polyposis (MAP)

Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer

Question 3:

Which hereditary cancer syndrome is frequently associated with congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium (CHRPE)?

MEN2a

HNPCC

Typical FAP

MUTYH-associated polyposis (MAP)

Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer

Question 4:

Before which age is the occurrence of colon cancer indicative of hereditary colon cancer, regardless of the family history?

90 years

80 years

70 years

60 years

50 years

Question 5:

Which of the following examinations belongs to the annual early detection program for a healthy 45-year-old HNPCC mutation carrier?

Complete colonoscopy

Capsule endoscopy

C3 breath test

Abdominal computed tomography

Determination of tumor marker CA-125

Question 6:

Which of the following tumors belongs to the typical tumor spectrum of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2?

Colon cancer

Plasmocytoma

C-cell thyroid cancer

Ovarian cancer

Follicular thyroid cancer

Question 7:

About what can predictive diagnostics in Li-Fraumeni syndrome provide information for the tested family members?

The age at which cancer will occur in the tested person

Whether participation in the well evaluated early detection program would be valuable for the tested person

Whether the tested person has inherited the causative mutation and thus the increased cancer risk

Whether the tested person will develop cancer in his/her life

In which organ cancer will occur in the person concerned

Question 8:

How high is the probability of a woman in the general population being a mutation carrier for familial breast and ovarian cancer?

1 : 5–1 : 10

1 : 50–1 : 100

1 : 500–1 : 1000

1 : 5,000–1 : 10 000

About 1 : 1 000 000

Question 9:

How high is the percentage risk for siblings of patients with MUTYH-associated polyposis (MAP) of also being affected by the disease?

5%

10%

15%

25%

50%

Question 10:

Which finding suggests the presence of a hereditary cancer syndrome?

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) in a 5-year-old child

Two basaliomas in a 60-year-old agricultural worker

A colorectal adenoma in a 68-year-old patient

Breast cancer in a 25-year-old female patient

Lung cancer in a 70-year-old smoker

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by mt-g.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists according to the guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

References

- 1.Harper P. Practical Genetic Counselling. Sixth Edition. London: Hodder Arnold; 2004. 331 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richtlinien zur Diagnostik der genetischen Disposition für Krebserkrankungen. Dtsch Arztebl. 1998;95(22) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knudson AG. Two genetic hits (more or less) to cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:157–162. doi: 10.1038/35101031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aretz S, Propping P, Nöthen MM. Indikationen zur molekulargenetischen Diagnostik bei erblichen Krankheiten. Dtsch Arztebl. 2006;103(9):A550–A558. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brekelmans CT, Seynaeve C, Bartels CC, et al. Effectiveness of breast cancer surveillance in BRCA1/2 gene mutation carriers and women with high familial risk. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:924–930. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.4.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vasen HF, Möslein G, Alonso A, et al. Guidelines for the clinical management of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) Gut. 2008;57:704–713. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.136127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robert Koch-Institut; Gesellschaft der epidemiologischen Krebsregister in Deutschland e.V. Krebs in Deutschland 2003 - 2004. Häufigkeiten und Trends. 6. überarbeitete Auflage. Berlin: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lynch HT, de la Chapelle A. Hereditary colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:919–932. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra012242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vasen HF, Watson P, Mecklin JP, Lynch HT. New clinical criteria for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC, Lynch syndrome) proposed by the International Collaborative group on HNPCC. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:1453–1456. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70510-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lamberti C, Mangold E, Pagenstecher C, et al. Frequency of hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer among unselected patients with colorectal cancer in Germany. Digestion. 2006;74:58–67. doi: 10.1159/000096868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Umar A, Boland CR, Terdiman JP, et al. Revised Bethesda Guidelines for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome) and microsatellite instability. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:261–268. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Boland CR, Hamilton SR, et al. A National Cancer Institute Workshop on Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colorectal Cancer Syndrome: meeting highlights and Bethesda guidelines. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89(3):1758–1762. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.23.1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schulmann K, Mangold E, Schmiegel W, Propping P. Wirksamkeit der Krebsfrüherkennung beim hereditären kolorektalen Karzinom ohne Polyposis. Dtsch Arztebl. 2004;101(8):A506–A512. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedl W, Lamberti C. Familiäre adenomatöse Polyposis. In: Ganten D, Ruckpaul K, editors. Hereditäre Tumorerkrankungen. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer; 2001. pp. 305–329. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmiegel W, Pox C, Adler G, Fleig W, Fölsch UR, Frühmorgen P, Graeven U, et al. S3-Leitlinienkonferenz „Kolorektales Karziom“ 2004. Z Gastroenterol. 2004;42:1129–1177. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-813699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN, et al. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1977–1981. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312303292701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aretz S, Uhlhaas S, Goergens H, et al. MUTYH-associated polyposis: 70 of 71 patients with biallelic mutations present with an attenuated or atypical phenotype. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:807–814. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Volker Krieg. Epidemiologie des Brustkrebses, Symposion zum Mammakarzinom. www.krebsregister.nrw.de. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmutzler R, Schlegelberger B, Meindl A, et al. Stufe-3-Leitlinie Brustkrebs-Früherkennung in Deutschland, 1. update 2008, Edited by U.-S. Albert on behalf of the members of the planning group and the leaders of the working groups in the "Concerted Action for Early Detection of Breast Cancer in Germany,". München, Wien, New York: Zuckerschwerdt Verlag; 2008. Hereditäre Brustkrebserkrankung; pp. 56–59. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Antoniou AC, Pharoah PD, McMullan G, Day NE, Ponder BA, Easton D. Evidence for further breast cancer susceptibility genes in addition to BRCA1 and BRCA2 in a population-based study. Genet Epidemiol. 2001;21:1–18. doi: 10.1002/gepi.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walsh T, Casadei S, Coats KH. Spectrum of mutations in BRCA1, BRCA2, CHEK2, and TP53 in families at high risk of breast cancer. JAMA. 2006;295(22):1379–1388. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.12.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marini F, Falchetti A, Del Monte F, et al. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006;1 doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-1-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ritter MM, Höppner W. Multiple endokrine Neoplasie. In: Ganten D, Ruckpaul K, editors. Hereditäre Tumorerkrankungen. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer; 2001. 430 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Le Bihan C, Moutou C, Brugieres L, Feunteun J, Bonaiti-Pellie C. ARCAD: a method for estimating age-dependent disease risk associated with mutation carrier status from family data. Genet Epidemiol. 1995;12:13–25. doi: 10.1002/gepi.1370120103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thull DL, Vogel VG. Recognition and management of hereditary breast cancer syndromes. Oncologist. 2004;9:13–24. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.9-1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]