Abstract

Somatostatin is a neuropeptide best known for its inhibitory effects on growth hormone secretion and has recently been implicated in the control of social behavior. Several somatostatin receptor subtypes have been identified in vertebrates, but the functional basis for this diversity is still unclear. Here we investigate the expression levels of the somatostatin prepropeptide and two of its receptors, sstR2, and sstR3, in the brains of socially dominant and subordinate A. burtoni males using real-time PCR. Dominant males had higher somatostatin prepropeptide and sstR3 expression in hypothalamus compared to subordinate males. Hypothalamic sstR2 expression did not differ. There were no differences in gene expression in the telencephalon. We also observed an interesting difference between dominants and subordinates in the relationship between hypothalamic sstR2 expression and body size. As would be predicted based on the inhibitory effects of somatostatin on somatic growth, sstR2 expression was negatively correlated with body size in dominant males. In contrast sstR2 expression was positively correlated with body size in subordinate males. These results suggest that somatostatin prepropeptide and receptor gene expression in the hypothalamus are associated with the control of somatic growth in A. burtoni depending on social status.

Keywords: aggression, growth, social behavior, pre-optic area, Astatotilapia burtoni

Introduction

Studies of the peptide hormone somatostatin have revealed that this hormone has diverse physiological functions. Originally discovered for its negative effects on growth hormone secretion1, somatostatin is now known to act in a variety of tissues to regulate energy balance and metabolism2, 3. There is also growing evidence that somatostatin can act as a neuromodulator4, 5, modulating both motor6 and even social behaviors7. This diversity in function is perhaps reflected in the diversity of somatostatin receptor subtypes.

Five different somatostatin receptor (sstR) subtypes have been identified in vertebrates2. Based on structural and pharmacological characteristics the five types can be classified into two subgroups: sstR2/sstR3/sstR5 subgroup and sstR1/sstR4 subgroup. The former subgroup binds octapeptide and hexapeptide somatostatin analogs whereas the latter subgroup does not bind these analogs8. All five receptor types are expressed in the mouse brain9 whereas all subtypes but sstR4 have been identified in teleost brains10, 11. An autoradiography study on goldfish (Carassius auratus) brain found that radiolabeled somatostatin binding sites occurred primarily within three systems11: the preoptic/hypothalamic area (involved in regulation of pituitary hormones), the facial and vagal lobes (involved in the regulation of ingestive behavior), and the optic tectum (involved in the integration of visual stimuli). Despite identification and localization of multiple somatostatin receptor subtypes, there has been relatively little resolution of the functional bases of differential receptor expression. Sst2 and sst5 are the predominant subtypes in the pituitary of both rodents16 and teleosts17,18. Selective somatostatin ligands provide evidence for subtype specific function, as sst2 and sst5 agonists inhibit pituitary growth hormone secretion in rats, whereas selective sst1 and sst3 agonists do not19. The diversity of sst subtypes is likely a contributing factor to some of somatostatin's distinct biological functions20, as differences in the expression of receptor subtypes may affect how somatostatin acts on various physiological processes in diverse tissues. While developmental plasticity in the expression of the five sst subtypes has been explored21,22, plasticity in sst expression in adults has not been examined in detail [but see 23].

In addition to the diversity in receptors, different forms of the somatostatin peptide itself have been identified in teleost fish12. Expression of the somatostatin I gene in the brain primarily leads to production of a 14 amino acid protein that is closely associated with neuroendocrine regulation (especially growth hormone). The somatostatin II gene has apparently arisen during a gene duplication event and its expression generally results in the production of a 28 amino acid peptide3. Its role in the brain and behavior is less clear than other forms of somatostatin. A growing number of studies suggest that somatostatin III (and its mammalian homolog cortistatin) has important effects on circadian rhythms13. In goldfish the three forms have distinct but overlapping distributions within the brain14, all three transcripts being present in the hypothalamus. We focused on somatostatin I because of our interest in growth and our previous work implicating the neuroendocrine functions of somatostatin in regulating behavior7.

Previous studies suggest that somatostatin is important in behavioral and neural plasticity in the cichlid fish Astatotilapia (formerly Haplochromis) burtoni7. In this species, dominant males aggressively maintain a territory and are reproductively active, whereas subordinate males school with females and are reproductively suppressed15, 16. Subordinate males grow faster than dominant males (many teleosts grow throughout life), apparently representing a trade-off between growth and reproduction17. Frequent fluctuations of the physical environment are common in the natural habitat18 and laboratory studies indicate that such fluctuations result in constant change in social dominance relationships 19. Such transitions in social status are characterized by asymmetrical changes in growth and reproduction19, 20, with up-regulation of the reproductive axis in socially ascending males being more rapid than reductions. Somatostatin immunoreactive neurons in the preoptic area (POA) are about four times larger in dominant males compared to subordinate males, and POA somatostatin neuron size is negatively correlated with growth rate21. This finding suggested that the increased neuron size may be due to increased production of somatostatin along with increased release (with a subsequent reduction in growth).

We characterized phenotypic differences in somatostatin-I prepropeptide and somatostatin receptor gene expression in the hypothalamus, telencephalon, and pituitary of dominant and subordinate male A. burtoni. Using real-time PCR we measured gene expression in the hypothalamus and pituitary because previous work has identified these regions as critical in the regulation of somatic growth. We also measured gene expression in the telencephalon because our previous observations demonstrated that somatostatin has inhibitory effects on aggressive behavior, and serotonergic activity in the telencephalon is known to modulate aggression22. In addition, somatostatin plays a neuromodulatory role in the telencephalon, particularly in the hippocampus23. If larger hypothalamic somatostatin neuron size in dominant males is related primarily to reduced growth of dominant males, then dominant males should have more somatostatin prepropeptide, sstR2, and sstR3 expression than subordinate males. In contrast, if changes in somatostatin receptor gene expression in the brain affect aggression, we expected to observe reduced hypothalamic sstR3 and sstR2 expression in dominant males. We also expected to observe a relationship between receptor gene expression and aggressive behavior either between dominant and subordinate males or within dominant males.

Methods

Subjects

Fish were descendents of a wild-caught stock population18 and were group-housed (5-7 males, 6 females per tank) in 100L aquaria as previously described18, 21. Each aquarium contained 5 overturned terracotta flowerpots in a standard layout (one in each corner plus one central location). The flowerpots mimic the natural substrate and are necessary for males to establish vigorously defended territories, to which they attract females for spawning 18. In each tank there were 2-3 dominant males and 3-4 subordinate males. All males were tagged with colored beads attached to a plastic tag (Avery-Dennison, Pasadena, CA), which was inserted with a stainless steel tagging tool (Avery-Dennison) through the skin just below the dorsal fin at least one week before behavioral observations were conducted. All procedures were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and were approved by the Harvard University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol # 22-22).

Behavioral Observations for Gene Expression Studies

To examine differences in somatostatin gene expression in the brain between dominant (n = 12) and subordinate (n = 10) males we conducted two 10 min behavioral observations over a period of two weeks. We identified dominant and subordinate males by quantifying three behaviors based on previous descriptions of A. burtoni18. Chasing was defined as the number of times a territorial male chased non-territorial males or females. Border display was defined as the number of times a territorial male displayed to an adjacent territorial male by flaring the gills. Courtship displays were scored when males adopted a quivering display directed towards a female. For gene expression analyses, we chose unambiguously subordinate males that did not engage in any courtship or aggressive behaviors. Only one dominant and one subordinate male per tank was chosen. Males were measured for standard length (body size), and rapidly decapitated. We collected whole telencephalon and hypothalamus (Fig. 1) from each brain and stored these tissues in RNAlater (Ambion, Austin, TX). Previous studies in A. burtoni and other fish demonstrate that the hypothalamic portion includes almost the entire preoptic area with the exception of the rostral portion of the anterior parvocellular preoptic nucleus24-26. This rostral portion of the anterior parvocellurlar preoptic nucleus contains only a small fraction of the somatostatin I expressing neurons present in the POA14.

Figure 1.

Brain of male Astatotilapia burtoni with hypothalamus (including the preoptic area) and telencephalon indicated with circles.

Cloning of Somatostatin Prepropeptide and Real-time PCR

The full length cDNAs for sstR2 and sstR3 have been previously described27. To clone the somatostatin I prepropeptide, primers were designed based on the highly conserved somatostatin-14 peptide, forward primer [5′-TGCTCTTGTCGGACCTCCTGCAGG-3′], reverse primer [5′-TTCCAGAAGAAGTTCTTGCA-3′]. PCR was conducted as described above and a 150 bp band was cloned and sequenced. Using the sequence of this fragment, the full length cDNA was obtained using 5′ [5′-CGCTCCAGGTCGACGCGGATGTCTTC-3′] and 3′ [5′-GGAGAACTTCCCTCTGGCCGACGGTGA-3′] RACE (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). The products of these reactions were gel purified, subcloned, and sequenced. We also attempted to sequence sstR1 and sstR5 transcripts but were unsuccessful. Future studies will probe an A. burtoni cDNA library for these transcripts.

RNA was extracted from whole hypothalamus and telencephalon samples in 0.5 mL of Trizol and RNA quality was checked using the Nanochip on a Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA.). For each RNA sample, 2 μg of RNA was treated with DNase (Amplification grade, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and RNA concentration was precisely determined in duplicate using the RiboGreen assay (Invitrogen). This assay allows for precise determinations of RNA concentrations, which alleviates the need for using so-called house-keeping genes when conducting quantitative real-time PCR28. Although housekeeping genes are often used as standards in quantitative real-time PCR experiments, it has been shown repeatedly that their expression levels cannot be assumed to be constant across experimental conditions28-30. Normalization of RNA using the Ribogreen method is not affected by differences in standard housekeeping gene expression such as G3PDH or 18s ribosomal RNA in subsequent real-time PCR28, 29. Based on the Ribogreen measurements of RNA, 1 μg of RNA from each sample was reverse transcribed using Superscript (Invitrogen) for use in quantitative real-time PCR reactions.

Quantitative Real-time PCR reactions were conducted on a MJ DNA Engine Opticon 2 thermocycler. Primers for all transcripts were designed using Primer3 (http://www-genome.wi.mit.edu/cgi-bin/primer/primer3_www.cgi). To design primers for sstR2 (Genbank accession #: AY585718) and sstR3 (AY585719) we used previously published sequences for A. burtoni31 We determined the efficiency of the PCR reaction using standard curves using the plasmids that were created when the cDNAs were cloned. The efficiency was calculated using the formula E = 10[-1/slope]-1, and was over 90% for all primer sets used. Cycling conditions were: 5 min at 95 C, then 40 cycles of 30 sec at 95 C, 30 sec at 52 C, and 30 sec at 72 C, followed by a five minute extension period and a melt curve analysis. All reactions were run in duplicate. Gene expression data were not normally distributed so we used non-parametric U-tests and rank correlations to analyze the data.

Results

The Astatotilapia burtoni somatostatin I peptide gene contains an open reading frame of 366 bp encoding a 119 amino acid prepropeptide and has 45% identity to both mouse and human sequences. The last 14 amino acids, which form the bioactive somatostatin peptide, are identical in A. burtoni, mouse, and human. This sequence has been deposited in Genbank (Genbank Accession #:AY585720).

Somatostatin and Somatostatin Receptor Gene Expression in Brain

In the hypothalamus, dominant males had significantly increased expression of somatostatin prepropeptide (Mann-Whitney, U = 21, p = 0.01) and sstR3 (U = 13, P < 0.01) compared to subordinates (Fig. 2a). There was no difference in sstR2 expression between dominants and subordinates (U = 39, p = 0.28). In the telencephalon, there were no significant differences between dominants and subordinates in somatostatin prepropeptide (Mann-Whitney U = 51, p = 0.78), sstR2 (U = 103, p = 0.43), or sstR3 (U = 105, p = 0.51) expression (Fig 2b). In the pituitary somatostatin prepropeptide was increased in dominant males compared to subordinates (Fig. 2c, Mann-Whitney U = 21, p = 0.01), whereas there were no differences in sstR2 (U = 34, p = 0.21), or sstR3 expression (U = 24, p = 0.99).

Figure 2.

Somatostatin and somatostatin receptor expression in the brain. Somatostatin I prepropeptide, sstR2 and sstR3 mRNA levels were measured in (A) hypothalamus, (B) telencephalon, and (C) pituitary from dominant (open bars) and subordinate males (black bars). ** P < 0.01.

Somatostatin and Somatostatin Receptor Gene Expression and Body Size

Interestingly, hypothalamic sstR2 expression was negatively correlated with body size in dominant males (Fig. 3b, Spearman ρ = -0.59, p = 0.04). Hypothalamic sstR3 (Fig. 3e, ρ = -0.16, p = 0.68) and somatostatin prepropeptide (Fig. 3a, ρ = -0.04, p = 0.89) expression did not co-vary with body size in dominant males. In contrast, body size in subordinates was positively correlated with sstR2 (Fig. 3d, Spearman ρ = 0.64, p = 0.04), sstR3 (Fig. 3f, ρ = 0.75, p = 0.01), and somatostatin prepropeptide (Fig. 3b, ρ = 0.77, p = 0.01) expression.

Figure 3.

Correlations between body size and hypothalamic somatostatin I prepropeptide (A,B), sstR2 (C,D), and sstR3 (E,F) in dominant and subordinate males. Spearman correlations with p-value are listed in each panel.

Somatostatin and Somatostatin Receptor Gene Expression and Social Behavior

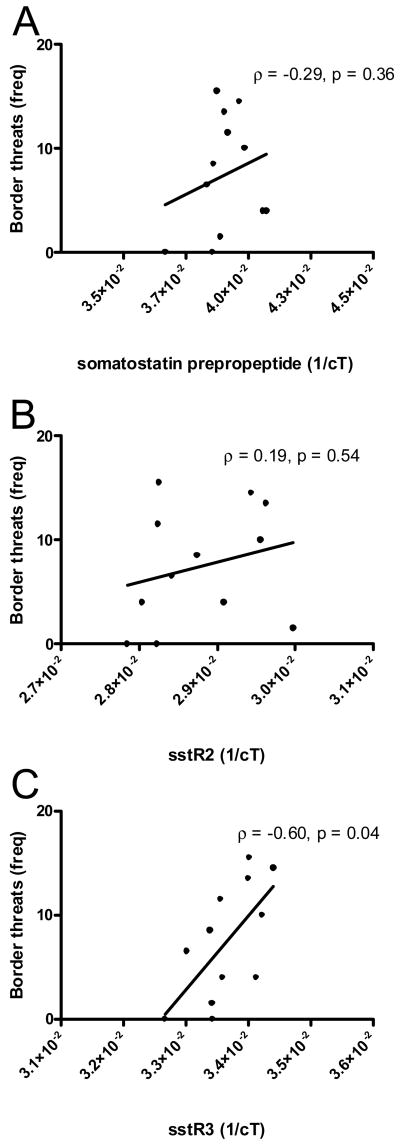

In dominant males, there were no significant correlations between social behaviors and hypothalamic sstR2 or somatostatin prepropeptide. Hypothalamic sstR3 expression was positively correlated with border threats (Fig. 4A, ρ = 0.60, p = 0.04) but not chasing (ρ = 0.1, p = 0.8) or courtship displays (ρ = 0.22, p = 0.5). There were no significant correlations between social behaviors and sstR2, sstR3, or somatostatin prepropeptide gene expression in the telencephalon or pituitary of dominant males (all p's > 0.09). There were also no significant correlations between sstR expression in hypothalamus or telencephalon and fleeing behavior in subordinate males.

Figure 4.

Correlations between border threats and hypothalamic somatostatin I prepropeptide (A), sstR2 (B), and sstR3 (C) in dominant males. Spearman correlations with p-value are listed in each panel.

Discussion

In the present study we have shown that in the hypothalamus the expression of somatostatin and its receptors is related to both social status and body size. Somatostatin is known to have an inhibitory effect on somatic growth, and we observed that dominant fish had increased expression of somatostatin prepropeptide and sstR3 gene expression in the hypothalamus. However, in subordinate fish somatostatin receptor and prepropeptide gene expression was positively correlated with body size. These results suggest that somatostatin plays a role in the intricate interplay between somatic growth and social behavior in A. burtoni. This complexity may explain why it has been a challenge to detect direct relationships between neural sstR2 and sstR3 expression in the brain and the previously described somatostatin-mediated regulation of social dominance.

Previous studies demonstrated that dominant A. burtoni males have reduced growth rates17 and larger somatostatin immunoreactive neurons than subordinate males21, and our results from real-time PCR experiments are consistent with these observations. Somatostatin in the preoptic area could mediate growth by directly regulating growth hormone secretion. An additional possibility is that differences in growth may be related to reduced food intake by dominant males, as subordinates have been observed to spend more time feeding than dominants3. Increased feeding is typically associated with increased plasma leptin levels32, and in rats leptin has been demonstrated to decrease somatostatin release into the median eminence33. Somatostatin outside of the preoptic area may also be important, as somatostatin I is expressed in the ventroposterior hypothalamus14, which is thought to control feeding behavior34. Somatostatin I expression in this region overlaps with expression of neuropeptide Y35 and cholesystokinin36, two peptides that are known to mediate food intake37.

Interestingly, the relationship between somatostatin gene expression and body size differed between dominant and subordinate males, suggesting a complex interplay between the effects of somatostatin on somatic growth on the one hand and social status on the other. In dominant males, sstR2 gene expression was negatively associated with body size, whereas in subordinate fish somatostatin receptor and prepropeptide gene expression was positively correlated with body size. The negative relationship between somatostatin gene expression in dominant males was expected as larger males generally have slower growth rates17 (presumably mediated by somatostatin21). Previous studies indicate that subordinate males have increased activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-interrenal axis and corticotrophin releasing hormone (CRH) can affect growth hormone secretion. Reduced somatostatin prepropeptide and receptor gene expression in subordinate males may allow for increased stimulation of growth hormone by CRH38. The negative relationship between somatostatin prepropeptide and body size in dominant males was unexpected and may be due to the dual role of somatostatin affecting growth and social behavior. There were no differences between dominant and subordinate males in sstR2 and sstR3 expression in the pituitary and telencephalon. This suggests that phenotypic differences in growth may not be mediated by changes in receptor expression, or that post-transcriptional processes may be more important in altering the sensitivity of the pituitary and telencephalon to somatostatin. Future experiments will determine the effects of somatostatin on somatostatin receptor expression in the pituitary and brain

In a previous study we demonstrated that somatostatin has robust inhibitory effects on aggressive behavior in dominant males27. Thus, we expected that more aggressive dominant males might have reduced somatostatin prepropeptide expression in the brain. In contrast, dominant fish had more somatostatin prepropeptide and sstR3 gene expression in hypothalamus than subordinates, and sstR3 expression was positively correlated with border threats (but not chasing behavior). These results do not support the hypothesis that differences in sstR2 or sstR3 expression mediate phenotypic differences in aggressive behavior. We suggest that increased sstR3 expression in dominant males could possibly result in an autocrine inhibition of hypothalamic somatostatin release. Presumably this would result in altered signaling via other somatostatin receptor subtypes in different tissues (e.g. pituitary). An additional possibility is that subtle, anatomically specific differences in somatostatin receptor expression are present in dominant and subordinate males, with somatostatin acting in different cell populations (e.g., parvo- vs. magno-cellular portions of the POA) to affect behavior versus growth. Further study at a higher spatial resolution in the brain is needed to dissect the mechanisms by which somatostatin inhibits aggression in dominant males. There may also be important phenotypic differences in somatostatin II and III expression. In goldfish somatostatin II is mostly confined to the hypothalamus including portions of the preoptic area whereas somatostatin III transcripts are less abundant in the preoptic area and more abundant in telencephalon14. The expression of these transcripts will be examined in future studies.

In summary we have demonstrated that hypothalamic somatostatin prepropeptide and receptor gene expression is differentially regulated in dominant and subordinate A. burtoni, likely as a consequence of somatostatin's dual role in regulating both dominance behavior and socially controlled growth. Further characterization of the distribution of the different somatostatin receptor subtypes and colocalization with the somatostatin prepropeptide will help in clarifying the complex interplay between a versatile neuropeptide, growth and social behavior.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sarah Annis and Jennie Lin for technical assistance; Christian Daly and Claire Reardon for advice on quantitative PCR; Flora Hinz and Jonah Larkins-Ford for comments on the manuscript, and all members of the Hofmann laboratory for discussions. This work was supported by NIGMS grant GM068763 and the Bauer Center for Genomics Research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Brazeau P, Vale W, Burgus R, Ling N, Butcher M, Rivier J, Guillemin R. Hypothalamic polypeptide that inhibits the secretion of immunoreactive pituitary growth hormone. Science. 1973;179:77–79. doi: 10.1126/science.179.4068.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel YC. Somatostatin and its receptor family. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 1999;20:157–198. doi: 10.1006/frne.1999.0183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson LE, Sheridan MA. Regulation of somatostatins and their receptors in fish. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2005;142:117–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weckbecker G, Lewis I, Albert R, Schmid HA, Hoyer D, Bruns C. Opportunities in somatostatin research: biological, chemical and therapeutic aspects. Nat Reviews Drug Discovery. 2003;2:999–1017. doi: 10.1038/nrd1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Epelbaum J, Dournaud P, Fodor M, Viollet C. The neurobiology of somatostatin. Critical Rev Neurobiol. 1994;8:25–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Viollet C, Vaillend C, Videau C, Bluet-Pajot M, Ungerer A, L'Heritier A, Kopp C, Potier B, Billard J, Schaeffer J, Smith R, Rohrer S, Wilkinson H, Zheng H, Epelbaum J. Involvement of sst2 somatostatin receptor in locomotor, exploratory activity and emotional reactivity in mice. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;12:3761–3770. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trainor BC, Hofmann HA. Somatostatin regulates aggressive behavior in an African cichlid fish. Endocrinol. 2006;147:5119–5125. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dournaud P, Slama A, Beaudet A, Epelbaum J. Somatostatin receptors. In: Quirion R, Bjorklund A, Hokfelt T, editors. Hanbook of Chemical Neuroanatomy. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science; 2000. pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar U, Laird D, Srikant CB, Escher E, Patel YC. Expression of the five somatostatin receptor (SSTR1-5) in rat pituitary somatotrophes: quantitative analysis by double-layer immunoflourescence confocal microscopy. Endocrinol. 1997;138 doi: 10.1210/endo.138.10.5566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zupanc GK, Cecyre D, Maler L, Zupanc MM, Ouirion R. The distribution of somatostatin binding sites in the brain of gymnotiform fish, Apteronotus leptorhynchus. J Chem Neuroanat. 1994;7:49–63. doi: 10.1016/0891-0618(94)90007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cardenas R, Lin X, Chavez M, Abramburo C, Peter RE. Characterization and distribution of somatostatin binding sites in goldfish brain. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2000;117:117–128. doi: 10.1006/gcen.1999.7396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin X, Otto CJ, Peter RE. Expression of Three Distinct Somatostatin Messenger Ribonucleic Acids (mRNAs) in Goldfish Brain: Characterization of the Complementary Deoxyribonucleic Acids, Distribution and Seasonal Variation of the mRNAs, and Action of a Somatostatin-14 Variant. Endocrinology. 1999;140:2089–2099. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.5.6706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Canosa LF, Peter RE. Pre-pro-somatostatin-III may have cortistatin-like functions in fish. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2005;1040:253–256. doi: 10.1196/annals.1327.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Canosa LF, Cerda-Reverter JM, Peter RE. Brain mapping of three somatostatin-encoding genes in the goldfish. J Comp Neurol. 2004;474:43–57. doi: 10.1002/cne.20097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hofmann HA, Fernald RD. What cichlids tell us about the social regulation of brain and behavior. J Aquaricult Aquatic Sci. 2001;9:17–31. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernald RD. Social regulation of the brain: sex, size and status. Novartis Found Symp. 2002;244:169–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hofmann HA, Benson ME, Fernald RD. Social status regulates growth rate: consequences for life-history strategies. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14171–14176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.14171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fernald RD, Hirata NR. Field study of Haplochromis burtoni: quantitative behavioural observations. Anim Behav. 1977;25:964–975. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hofmann HA. Functional genomics of neural and behavioral plasticity. J Neurobiol. 2003;54:272–282. doi: 10.1002/neu.10172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.White SA, Nguyen T, Fernald RD. Social regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone. J Exp Biol. 2002;205:2567–2581. doi: 10.1242/jeb.205.17.2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hofmann HA, Fernald RD. Social status controls somatostatin neuron size and growth. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4740–4744. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-12-04740.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Øyvind Ø, Korzan WJ, Larson ET, Winberg S, Lepage O, Pottinger TG, Renner KJ, Summers CH. Behavioral and neuroendocrine correlates of displaced aggression in trout. Horm Behav. 2004;45:324–329. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sloviter RS, Nilaver G. Immunocytochemical localization of GABA-like, cholecystokinin-like, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide-like, and somatostatin-like immunoreactivity in the area dentata and hippocampus of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1987;256:42–60. doi: 10.1002/cne.902560105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fernald RD, Shelton LC. The organization of the diencephalon and the pretectum in the cichlid fish, Haplochromis buroni. J Comp Neurol. 1985;238:202–217. doi: 10.1002/cne.902380207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen CC, Fernald RD. Distributions of two gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor types in a cichlid fish suggest functional specialization. J Comp Neurol. 2006;495:314–323. doi: 10.1002/cne.20877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burmeister SS, Kailasanath V, Fernald RD. Social dominance regulates androgen and estrogen receptor gene expression. Horm Behav. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.09.008. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trainor BC, Hofmann HA. Somatostatin regulates aggressive behavior in an African cichlid fish. Endocrinol. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0511. in review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hashimoto JG, Beadles-Bohling AS, Wiren KM. Comparison of RiboGreen and 18s rRNA quantitation for normalizing real-time RT-PCR expression analysis. Biotechniques. 2004;36:54–60. doi: 10.2144/04361BM06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aubin-Horth N, Landry CR, Letcher BH, Hofmann HA. Alternative life histories shape brain gene expression profiles in males of the same population. Proc R Soc Lond B. 2005;272:1655–1662. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bustin SA. Quantification of mRNA using real-time reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR): trends and problems. J Mol Endocrinol. 2002;29:23–39. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0290023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trainor BC, Hofmann HA. Somatostatin regulates aggressive behavior in an African cichlid fish. Endocrinol. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0511. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schneider JE, Wade GN. Inhibition of reproduction in sevice of energy balance. In: Wallen K, Schneider JE, editors. Reproduction in Context. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2000. pp. 35–82. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watanobe H, Habu S. Leptin regulates growth hormone-releasing factor, somatostatin, and alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone but not neuropeptide Y release in rat hypothalamus in vivo: Relation with growth hormone secretion. 2002;22:6265–6271. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-14-06265.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peter RE. The brain and feeding behavior. In: Hoar SW, Randall DJ, Brett JR, editors. Fish physiology. New York: Academic Press; 1979. pp. 121–159. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pickavance LC, Staines W, Fryer JN. Distribution and colocalization of neuropeptide Y and somatostatin in the goldfish brain. J Chem Neuroanat. 1992;5:221–233. doi: 10.1016/0891-0618(92)90047-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Himick BA, Peter RE. CCK/gastrin-like immunoreactivity in brain and gut, and CCK suppression of feeding in goldfish. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:R841–R851. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.267.3.R841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Volkoff H, Canosa LF, Unniappan S, Cerda-Reverter JM, Bernier NJ, Kelly SP, Peter RE. Neuropeptides and the control of food intake in fish. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2005;142:3–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rousseau K, Le Belle N, Marchelidon J, Dufour S. Evidence that corticotropin-releasing hormone acts as a growth hormone-releasing factor in a primitive teleost, the European eel (Anguilla anguilla) J Neuroendocrinol. 1999;11:385–392. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1999.00334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]