Abstract

The incidence of brain metastasis is rising and poses a severe clinical problem, as we lack effective therapies and knowledge of mechanisms that control metastatic growth in the brain. Here we demonstrate a crucial role for high-affinity tumor cell integrin αvβ3 in brain metastatic growth and recruitment of blood vessels. Although αvβ3 is frequently up-regulated in primary brain tumors and metastatic lesions of brain homing cancers, we show that it is the αvβ3 activation state that is critical for brain lesion growth. Activated, but not non-activated, tumor cell αvβ3 supports efficient brain metastatic growth through continuous up-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) protein under normoxic conditions. In metastatic brain lesions carrying activated αvβ3, VEGF expression is controlled at the post-transcriptional level and involves phosphorylation and inhibition of translational respressor 4E-binding protein (4E-BP1). In contrast, tumor cells with non-activated αvβ3 depend on hypoxia for VEGF induction, resulting in reduced angiogenesis, tumor cell apoptosis, and inefficient intracranial growth. Importantly, the microenvironment critically influences the effects that activated tumor cell αvβ3 exerts on tumor cell growth. Although it strongly promoted intracranial growth, the activation state of the receptor did not influence tumor growth in the mammary fat pad as a primary site. Thus, we identified a mechanism by which metastatic cells thrive in the brain microenvironment and use the high-affinity form of an adhesion receptor to grow and secure host support for proliferation. Targeting this molecular mechanism could prove valuable for the inhibition of brain metastasis.

Keywords: angiogenesis, brain metastasis, integrin activation, 4E-BP1

Brain metastases are diagnosed in 10% to 40% of patients with progressing cancer, and the incidence is rising as patients live longer and extracranial metastases respond to improved treatments. However, brain metastases still cannot be treated effectively, and mechanisms controlling brain metastatic growth are largely unknown (1–3).

Here, we demonstrate that the high-affinity state of tumor cell adhesion receptor integrin αvβ3 critically promotes metastatic growth and recruitment of supporting blood vessels within the brain microenvironment. Integrins are cell surface receptors composed of non–covalently linked α and β subunits that mediate cell–matrix and cell–cell interactions and transduce signals that have impacts on cell survival, proliferation, adhesion, migration, and invasion. Integrin signals can also originate inside cells, affect receptor affinity, and thereby control ligand binding, cross talk with other receptors, and alter cell adhesion and proliferation (4–6). Integrin αvβ3 also plays a role on sprouting endothelial cells and contributes to angiogenesis (7). In several tumor types, including glioma, breast cancer, and melanoma, expression of αvβ3 supports invasion and metastasis (8–11). Notably, these tumors either originate in the brain or frequently spread to the brain. Because of this correlation and our previous findings that expression of αvβ3 by tumor cells, particularly in its high-affinity form, promotes metastatic dissemination (12), we asked whether αvβ3 and the activation state of the receptor also play a role in metastatic growth within the brain microenvironment. To address this question directly, we generated and validated a human tumor cell model in which variants share a genetic background and express integrin αvβ3 either in a constitutively activated or non-activated functional form. Our results show that tumor cell αvβ3 activation promotes tumor cell growth in the brain but not in the mammary fat pad (MFP) as a primary site, pointing to a critical influence of the tissue environment on the ability of high-affinity αvβ3 to enhance tumor growth. Our study suggests that the mechanism through which activated αvβ3 supports brain metastatic growth is based on elevated expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) because of inhibition of translational repressor 4E-BP1, resulting in efficient tumor angiogenesis under normoxic conditions. This function prevents development of hypoxia, associated tumor cell apoptosis, and retardation of lesion growth. Thus, as an initiator of this process, activated integrin αvβ3 could potentially serve as a target against brain metastasis.

Results

Tumor Cell Integrin αvβ3 Activation Enhances Metastatic Growth in the Brain.

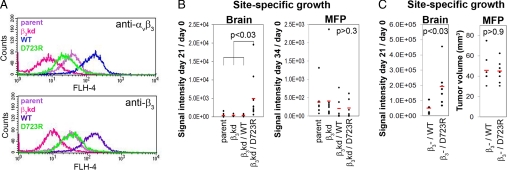

We chose MDA-MB-435 human cancer cells for our analysis because they are highly metastatic, can spread to the brain, and express αvβ3, and because the activation state of the receptor strongly affects metastasis to extracranial sites (12). To generate cell variants that express αvβ3 in defined states of activation, endogenous αvβ3 was knocked-down, targeting the 3′UTR of the β3 subunit gene and then reconstituted either with non-activated β3WT or constitutively activated mutant β3D723R (12, 13). In MDA-MB-435 cells, αvβ3 is the only β3 integrin. Thus, targeting β3 by stable transduction with lentiviral shRNA resulted in 80% reduction of total β3 protein (Western blot, not shown) and 70% reduction in αvβ3 surface expression (Fig. 1A), without affecting other integrins. This was confirmed by fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis of a panel of integrins, including αvβ5 and αvβ6 (not shown). Importantly, β3 down-regulation remained stable in tumor xenografts [supporting information (SI) Fig. S1]. The cDNA constructs used for reconstitution with β3WT or β3D723R lack 3′-UTRs and are therefore not affected by the β3 shRNA. αvβ3 surface expression in β3D723R cells resembled that of the parental cells, whereas β3WT cells expressed twice as much αvβ3 (Fig. 1A). Notably, αvβ3 activation by mutant β3D723R was stable after tumor cell implantation into the brain or MFP.

Fig. 1.

Impact of tumor cell integrin αvβ3 expression and activation on lesion growth in the brain and mammary fat pad (MFP). (A) Analysis of integrin αvβ3 expression by flow cytometry. Parent, MDA-MB-435 transduced with control shRNA ScrB; β3kd, MDA-MB-435 transduced with β3 shRNA; WT, MDA-MB-435/β3kd reconstituted with wild-type β3 (non-activated αvβ3); D723R, MDA-MB-435/β3kd reconstituted with β3D723R (activated αvβ3). (B) Lesion growth in the brain (days 0–21) or MFP (days 0–34) based on bioluminescence signal of F-luc–tagged tumor cells by non-invasive in vivo imaging. (C) Lesion growth in the brain (days 0–21) or MFP (days 0–36) of MDA-MB 435/β3- cells selected from parental cells with saporin-anti-β3 antibody and reconstituted by transfection with β3WT of β3D723R based on in vivo imaging (brain) or caliper measurement (MFP). Each dot represents one animal and red lines the mean values per group; group sizes in (B): brain: parent and β3kd, n = 6; β3WT and β3D723R, n = 11; MFP: parent, n = 10; β3kd, n = 8; β3 and β3D723R, n = 6; (C), all groups, n = 7. P values obtained by a two-tailed Student's t test with unequal variance.

When implanted into the forebrain (striatum), tumor cells expressing activated β3D723R exhibited a significant growth advantage over β3kd cells, cells expressing non-activated β3WT, and parental cells transduced with scrambled shRNA used as a control (Figs. 1B, 2A). In contrast, in the MFP, mimicking a primary tumor site, expression of activated β3D723R did not accelerate tumor growth, which was generally slower than in the brain (Fig. 1B). Notably, β3WT and β3D723R cells displayed identical growth rates in vitro (Fig. S2A).

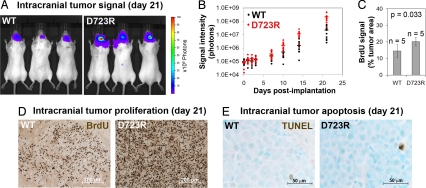

Fig. 2.

Tumor cell integrin αvβ3 activation enhances proliferation in the brain. (A) Non-invasive bioluminescence imaging 21 days after intracranial implantation of 1 × 104 β3WT- (Left) or β3D723R- (Right) expressing MDA-MB-435 tumor cells. (B) Growth of β3WT and β3D723R-expressing tumor cells in the brain. Each dot represents one animal; horizontal lines represent mean values per group. (C and D) Intracranial proliferation of β3WT- and β3D723R-expressing cells in brain lesions by in vivo BrdU uptake; n = 5 per group, P values obtained by a two-tailed Student's t test with unequal variance. (E) Apoptosis in β3WT and β3D723R brain lesions by TUNEL staining (brown).

The site-specific growth phenotype seen in β3WT and β3D723R cells was also observed with MDA-MB-435 β3-/WT and β3-/D723R cells (Fig. 1C). The previously described β3- cells (12) were obtained through selection with a saporin-conjugated anti-β3 antibody and used to generate β3WT and β3D723R re-expressing variants by plasmid transfection, and antibiotic selection (12). The organ-dependent growth behavior observed in both independently generated cell models confirmed that the phenotype is indeed due to the αvβ3 activation state. Thus, activation of integrin αvβ3 critically enhances tumor cell growth in the brain but is not required for growth in the MFP, implying that αvβ3 activation promotes metastatic growth in a microenvironment-dependent manner.

To investigate the mechanism involved, we followed tumor cell growth in the brain over time and realized initially no difference between cells expressing activated versus non-activated αvβ3. However, 10 days after implantation of 104 tumor cells, a significant growth difference became evident and then increased continuously (Fig. 2B). This difference was caused by an enhancement in tumor cell proliferation. On day 21, in vivo BrdU incorporation was 25% higher in β3D723R than in β3WT implants (Figs. 2C, 2D). Both lesion types showed low and comparable levels of apoptosis (<1%) by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining (Fig. 2E). Thus, once lesions in the brain reach an initial critical size, tumor cell integrin αvβ3 activation strongly enhances proliferation, without affecting cell survival.

Tumor Cell Integrin αvβ3 Activation Promotes Angiogenesis and Prevents Development of Hypoxia in Brain Lesions.

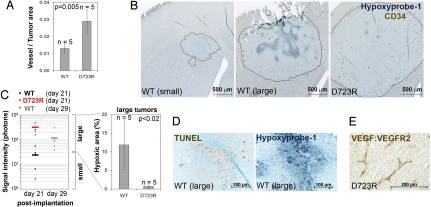

Having observed that the growth advantage of brain implants expressing activated β3D723R became apparent once the lesions reached an initial critical size, we asked whether a host response contributes to the accelerated tumor growth. In vivo labeling and detailed immunohistochemistry revealed two major points. First, the tumor area covered by blood vessels (CD34 stain) was significantly larger in lesions expressing activated β3D723R than in those expressing non-activated β3WT (Fig. 3A). This included all tumors, regardless of size. Notably, on day 21 post-implantation, five of five lesions in the β3D723R group were large and measured 2 to 3 mm in diameter, whereas only one in five in the β3WT group reached a threshold size of 1.5 mm. Second, whereas microvessels were distributed evenly throughout the large tumor areas in the β3D723R group with no or minimal hypoxic regions (<1%), vessels in the β3WT group were located mainly along the lesion margins. The only lager tumor in this group had developed extensive hypoxic regions in the poorly vascularized central area (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Tumor cell integrin αvβ3 activation increases angiogenesis and reduces hypoxia in brain lesions. (A) Quantification of the total vessel area in β3WT and β3D723R brain lesions 21 days after tumor cell implantion. Vessels were visualized by CD34 staining. (B) Immunohistochemistry of tumor vessels (brown) and hypoxic regions (gray-blue) in brain lesions on day 21. Borders between tumor area and brain parenchyma are outlined showing representative small (≤1.5 mm) and large (≥ 1.5 mm) β3WT lesions. All β3D723R lesions were >2 mm. (C) (Left) In vivo signal of β3WT (black) and β3D723R (red) brain lesions on day 21, and on day 29 for β3WT (gray) to obtain larger lesions for this group. Only lesions with a diameter ≥1.5 mm (≈5 × 107 bioluminescence photons in vivo) were included in the quantification of hypoxic tumor regions (marked with a bracket as large tumors). (Right) Percentage of hypoxic area in brain lesions >1.5 mm in diameter; n = 5 per group; P values based on two-tailed Student's t test with unequal variance. (D) Large β3WT lesions (> 1.5 mm) show increased apoptosis (Left; TUNEL staining, brown; nuclei, green) within hypoxic regions (Right; Hypoxyprobe-1 staining, gray-blue; nuclei, green) in adjacent sections. (E) Formation of the VEGF:VEGFR2 complex on tumor vessels in β3D723R brain lesions (Gv39M staining, brown).

To investigate whether the development of hypoxic regions in the β3WT group is a function of lesion size, we allowed implants of β3WT-expressing cells to grow longer and become larger, making it possible to compare them to β3D723R-expressing lesions. An association between hypoxia development and tumor size in lesions expressing non-activated β3WT would further point to angiogenesis as a growth limiting factor. On day 29 post-implantation, four of five β3WT lesions were larger than 1.5 mm, and they were used for comparison with β3D723R lesions of the same or larger size (Fig. 3C). Although β3D723R lesions developed no or only minimal hypoxia, β3WT lesions harbored large hypoxic regions (Fig. 3C) with increased tumor cell apoptosis (Fig. 3D). Thus, expression of activated αvβ3 by the tumor cells is associated with their enhanced ability to attract new blood vessels, thereby avoiding hypoxia and protecting the growing tumor cells from apoptosis. De novo angiogenesis, rather than tumor cell growth around exiting vessels (vessel co-opting), was confirmed by expression of VEGF:VEGFR2 complex on the tumor vessels (Fig. 3E), identifying the angiogenic state of the endothelial cells (14).

Tumor Cell Integrin αvβ3 Activation Promotes VEGF Expression at the Post-Transcriptional Level in Normoxic Brain Lesions.

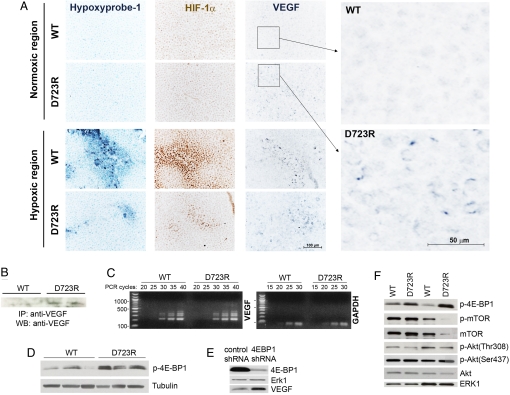

To identify a mechanism by which activated tumor cell integrin αvβ3 promotes angiogenesis in the brain, we focused on VEGF, a major promoter of endothelial proliferation (15). As hypoxia potently induces VEGF via transcription factor HIF-1α (16) or via induction of cap-independent internal ribosome entry site IRES-mediated translation (17), we analyzed VEGF expression in hypoxic versus normoxic tumor regions, identifying hypoxia by staining for Hypoxyprobe-1 and probing for HIF-1α. In hypoxic regions, VEGF protein expression was strong and associated with increased HIF-1α signal regardless of the αvβ3 activation state of the tumor lesions (Fig. 4A), indicating VEGF up-regulation at the transcriptional level. In contrast, in normoxic tumor regions devoid of Hypoxyprobe-1 and HIF-1α signal, VEGF was detected only in β3D723R but not in β3WT lesions (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Tumor cell integrin αvβ3 activation increases VEGF expression in the brain post-transcriptionally by 4E-BP phosphorylation. (A) VEGF protein expression in normoxic (upper panels) versus hypoxic areas (lower panels) of β3WT and β3D723R brain lesions by immunohistochemistry. Hypoxic regions defined by positive staining for Hypoxyprobe-1 (Left) and HIF-1α (Middle). β3WT and β3D723R lesions express VEGF in hypoxic regions. In normoxic regions, only β3D723R lesions express VEGF (Right; enlarged on far right). (B) VEGF protein levels in microdissected β3WT and β3D723R brain lesions 21 days after tumor cell implantation (immunoprecipitation [IP], VEGF; Western blot [WB], VEGF). (C) VEGF mRNA levels in microdissected β3WT and β3D723R brain lesions on day 21 post-implantation (RT-PCR). Lesions from three different mice per group. (D) Phospho-4E-BP1 signal in microdissected β3WT and β3D723R brain lesions 21 days after tumor cell implantation (Western blot with anti-phospho-4E-BP1 and anti-tubulin antibodies). (E) Down-regulation of 4E-BP1 in β3WT cells by shRNA results in a strong increase of VEGF protein level under normoxia in vitro. VEGF was immunoprecipitated from cell culture supernatants before Western blot analysis. (F) Detection of mTOR and Akt activation levels with phospho-specific antibodies in microdissected β3WT and β3D723R brain lesions 21 days after tumor cell implantation.

To determine whether αvβ3 activation in normoxic regions regulates VEGF expression at the transcriptional or post-transcriptional level (18, 19), proteins and total RNA were extracted from microdissected β3WT- and β3D723R-expressing lesions of mouse brains 21 days after tumor cell implantation. All analyzed β3WT lesions were smaller than 1.5 mm and still without hypoxic areas. β3D723R lesions, although larger, also showed no or minimal hypoxia (<1%) (Fig. 3). Western blot analysis of VEGF immunoprecipitated from brain tumor lysates confirmed increased VEGF protein levels in β3D723R-expressing lesions (Fig. 4B). Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT- PCR) with VEGF-specific primers yielded four distinct PCR products (230, 310, 365, and 430 bp) (Fig. 4C), corresponding to splice variants VEGF121, VEGF145, VEGF165, and VEGF189 (20), with no differences in mRNA levels or isoform patterns between β3WT- and β3D723R-expressing lesions (Fig. 4C). Thus, under normoxic conditions, tumor cell integrin αvβ3 activation regulates VEGF expression at the post-transcriptional level.

To investigate the mechanism involved, we focused on VEGF mRNA regulation. VEGF mRNA is “weakly” transcribed because of its highly structured 5′UTR, and its translation under normoxia strongly depends on the availability of eukaryotic initiation factor eIF4E (19, 21). eIF4E is bound and inhibited by eIF4E binding protein 1 (4E-BP1), which, when phosphorylated, no longer binds eIF4E and makes it available for translation of weak RNAs (22). 4E-BP1 was significantly stronger phosphorylated in β3D723R- than β3WT-expressing brain lesions (Fig. 4D), suggesting that increased VEGF expression is due to phosphorylation and inactivation of 4E-BP1. A causal relationship between 4E-BP1 inhibition and VEGF production under normoxia was confirmed by the finding that shRNA knock-down of 4E-BP1 in β3WT cells strongly increased VEGF protein levels in vitro (Fig. 4E). Similar to β3WT and β3D723R cells, 4E-BP1 knock-down and control cells also showed identical growth rates in culture (Fig. S2B).

We further investigated mTOR and Akt as major constituents of pathways controlling the 4E-BP1 protein (22). The mTOR protein is large and prone to degradation during tissue processing. We therefore compared the ratio between phosphorylated mTOR(Ser-2481) and total mTOR and found no difference between β3WT- and β3D723R-expressing lesions (Fig. 4F). Similarly, Akt activation measured by phosphorylation on Ser-308 and Thr-437 was also not altered because of αVβ3 activation (Fig. 4F). Thus, enhanced phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 associated with αVβ3 activation of the tumor cells is apparently not controlled by mTOR or Akt activation.

Tumor Cell Integrin αvβ3 Activation Does Not Prevent Hypoxia in Mammary Fat Pad Tumors.

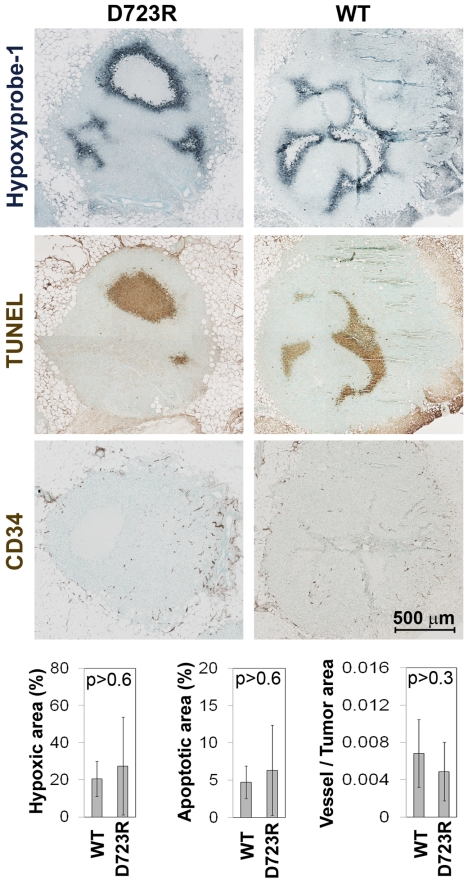

Although tumor cell integrin αvβ3 activation significantly increased growth of MDA-MB-435 cell implants in the brain, it had no impact on tumor growth in the MFP (Fig. 1B, 1C). There, β3kd as well as β3WT- and β3D723R-expressing cells grew more slowly than in the brain, and αvβ3 activation made no difference. In fact, MFP lesions expressing β3WT or β3D723R showed much lower blood vessel densities than brain lesions and developed extensive hypoxic regions with strong apoptosis and necrosis (Fig. 5). Hypoxic areas and some of the surrounding tissue strongly expressed VEGF in β3WT as well as β3D723R derived MFP lesions (Fig. S3). Because of the extensive expansion of hypoxic regions in MFP tumors, seen even in early lesions still smaller than 1 mm (not shown), it was not possible to define clearly normoxic areas and to analyze VEGF expression there. Thus, in the MFP, tumor cell αvβ3 activation is not sufficient to enhance recruitment of tumor blood vessels, prevent hypoxia, and accelerate tumor cell growth. Therefore, tumor cell integrin αvβ3 activation selectively enhances cancer growth in a microenvironment-dependent manner, strongly supporting lesion growth in the brain, a particularly feared metastatic site.

Fig. 5.

Tumor cell integrin αvβ3 activation does not prevent hypoxia in mammary fat pad tumors. Hypoxia (Hypoxyprobe-1 in gray-blue, Upper), apoptosis/necrosis (TUNEL staining in brown, Middle) and blood vessel denstity (CD34 in brown, Lower) in MFP tumors 34 days after implanting 1 × 104 β3WT- or β3D723R-expressing tumor cells. Quantifications are included (n = 5 per group). P values are based on two-tailed Student's t test with unequal variance. Note: All 34-day old MFP tumors were smaller than 21-day-old β3D723R brain lesions.

Discussion

We analyzed a role of integrin αvβ3 activation in tumor cell growth in the brain and mammary fat pad to represent clinically highly relevant metastatic and primary sites. We focused explicitly on αvβ3 in tumor cells, as it is largely unknown how the activation state of this receptor affects cancer progression whereas the endothelial receptor has been widely studied in angiogenesis. We show that tumor cell integrin αvβ3 activation strongly promotes metastatic growth in the brain by enabling tumor cells to attract blood vessels independently of hypoxia and thereby avoiding hypoxia-related growth stagnation and apoptosis. In contrast, in the mammary fat pad, tumor cell αvβ3 had no effect on lesions growth, which was generally slower than in the brain, poorly vascularized, extensively hypoxic, and associated with apoptosis and necrosis. Expression of activated tumor cell integrin αvβ3 could not overcome this limitation as it did in the brain. Therefore, the specific ability of activated tumor cell integrin αvβ3 to enhance angiogenesis clearly depends on the tissue microenvironment. Organ-dependent differences in growth factors, chemokines, cytokines, and matrix proteins, as well as stromal and immune components, may distinctly affect tumor cell growth and endothelial behavior in the mammary fat pad versus the brain (23) and may synergize with (brain) or antagonize (MFP) growth-promoting functions of activated tumor cell αvβ3.

Intracranial MDA-MB-435 lesions expressed four different VEGF isoforms, including freely diffusible VEGF121 and partially diffusible VEGF165, the most frequent isoform in VEGF-secreting cells (15, 19). Because of the strong hypoxia in the MFP environment, we were unable to reliably define normoxic MFP tumor areas and determine VEGF expression there. However, as previously shown, over-expression of VEGF121 in glioma cells increased angiogenesis in the brain, but not in the subcutaneous environment (24). This suggests that even though MDA-MB-435 β3D723R tumors might express VEGF in normoxic regions in the MFP, this might not be sufficient to promote angiogenesis. Similarly, HIF-1α knockout in transformed astrocytes reduced their growth in the subcutis but promoted it in the brain (25). Thus, the inability of the mammary fat pad to support continuous, hypoxia-independent angiogenesis may be related to the nature and responsiveness of vascular development in the mammary fat pad compared with the brain.

It was previously shown that VEGF can promote breast cancer cell survival in an autocrine manner (26). However, in our model, tumor cell survival was not limiting, and we found increased proliferation but no evidence for enhanced survival of tumor cells upon αvβ3 activation in normoxic brain lesions. Integrins can signal through different growth promoting pathways, including Src and MAPK (27–30). However, we detected no significant differences in pSrc and pERK levels between β3WT- and β3D723R-expressing brain lesions (not shown). In fact, all of our data point to increased vascularization as the main mechanism through which activated tumor cell integrin αvβ3D723R accelerates lesion growth in the brain: increased vascular density, strongly reduced hypoxia, and formation of VEGF:VEGFR2 complex indicating an angiogenic switch. Furthermore, divergence in growth rates between β3WT- and β3D723R-expressing brain lesions became obvious only after the tumors reached a size at which blood supply became limiting in β3WT tumors.

Although lesions expressing activated or non-activated αvβ3 up-regulated VEGF protein in hypoxic regions, only lesions with the activated receptor expressed elevated VEGF under normoxia. This was caused by αvβ3 activation–dependent control of VEGF at the post-transcriptional level. Our data indicate that activated αvβ3 promotes VEGF protein expression through inhibition of 4E-BP1, a repressor of mRNA translation. αvβ3 Activation in brain lesions induced phosphorylation and thereby inactivation of 4E-BP1, which is known to result in the release of eIF4E and increased translation of VEGF mRNA (21). A causal relationship between VEGF increase and 4E-BP1 inhibition in our model was provided by knock-down of 4E-BP1 in β3WT cells, as this resulted in increased VEGF production under normoxic conditions. Notably, under hypoxia, 4E-BP1 might exert an opposite effect on VEGF, as its over-expression has been shown to increase IRES-dependent VEGF translation (17). In the current study, however, we focused on normoxia, because increased VEGF expression resulting from αvβ3 activation occurred in normoxic brain lesions. Thus, our findings establish a link between the activation state of integrin αvβ3, regulation of translation, and angiogenesis in vivo.

Several integrins, including α6β4, αIIbβ3, and α2β1, can promote translation of weak mRNAs through the PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathway (31, 32). In contrast, activation of integrin αvβ3 did not result in enhanced activation of mTOR or Akt in brain lesions, suggesting that a different mechanism is involved. Notably, mTOR-independent phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 in breast cancer cells has been previously documented (33).

The incidence of brain metastases in tumor patients is rising. However, although therapies for primary tumors and extracranial metastases are improving, effective treatments for brain metastases are still missing (1–3). Our data define the activated, high-affinity conformer of tumor cell integrin αvβ3 as a potential new therapeutic target in brain metastasis. Moreover, our study points to the importance of the tumor microenvironment when considering different treatment options for cancer. Beyond drug accessibility, brain metastases apparently require specific targeting. Thus, information on mechanisms that promote metastatic growth in the brain as presented here can be a basis for the development of novel, effective therapies.

Materials and Methods

Tumor Cell Model.

MDA-MB-435 adenocarcinoma cells were from J.E. Price (M. D. Anderson), cultured as previously described (12), and stably tagged with Firefly luciferase (F-luc) using a lentiviral transduction system (34). For generation of MDA-MB-435 β3kd, β3WT, β3D723R, β3-/WT, β3-/D723R, and 4E-BP1 knock-down cells, see SI Methods.

Animal Experiments.

Female 6- to 8-week-old CB17/SCID mice were injected with 1 × 104 F-luc–tagged cancer cells either stereotactically into the striatum (2.5 mm right from the midline, 2.5 mm anterior from bregma, and 3 mm deep) or into the axillary mammary fat pad and imaged once (mfp) or twice (brain) weekly using an IVIS200 bioluminescence imaging system (Xenogen). BrdU (Sigma) (1 ml of 1 mg/ml) was injected intraperitoneally at 24 hours, and Hypoxyprobe-1 (NPI) (150 μl of 10 mg/ml) intraperitoneally 60 minutes before tissue harvest. All animal work complied with National Institutes of Health and institutional guidelines (TSRI is AAALAC accredited).

For detailed protocols of immunohistochemistry, RNA, and protein expression, see SI Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants CA095458 and CA112287 (to B.F.H.), CBCRP grants 12NB0176 and 13NB0180 (to B.F.H.), a UCSD NNC project grant (to B.F.H.), and fellowships from SG Komen (to M.L. and J.S.K.), and the Swedish Government to K.S.. We thank Bruce Torbet for F-luc expressing lentiviral constructs. Dr. Ernest Beutler, a NAS member, a leader in biomedical research and our Department Chair, contributed to this work based on numerous scientific discussions.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0903035106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Ranasinghe MG, Sheehan JM. Surgical management of brain metastases. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;22:E2. doi: 10.3171/foc.2007.22.3.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin NU, Bellon JR, Winer EP. CNS metastases in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3608–3617. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weil RJ, Palmieri DC, Bronder JL, Stark AM, Steeg PS. Breast cancer metastasis to the central nervous system. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:913–920. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61180-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arias-Salgado EG, Lizano S, Shattil SJ, Ginsberg MH. Specification of the direction of adhesive signaling by the integrin beta cytoplasmic domain. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:29699–29707. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503508200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ginsberg MH, Partridge A, Shattil SJ. Integrin regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:509–516. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stupack DG. The biology of integrins. Oncology (Williston Park) 2007;21(9) Suppl 3:6–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brooks PC, Clark RA, Cheresh DA. Requirement of vascular integrin alpha v beta 3 for angiogenesis. Science. 1994;264:569–571. doi: 10.1126/science.7512751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albelda SM, et al. Integrin distribution in malignant melanoma: association of the beta 3 subunit with tumor progression. Cancer Res. 1990;50:6757–6764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gingras MC, Roussel E, Bruner JM, Branch CD, Moser RP. Comparison of cell adhesion molecule expression between glioblastoma multiforme and autologous normal brain tissue. J Neuroimmunol. 1995;57:143–153. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(94)00178-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Natali PG, et al. Clinical significance of alpha(v)beta3 integrin and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression in cutaneous malignant melanoma lesions. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1554–1560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pignatelli M, Cardillo MR, Hanby A, Stamp GW. Integrins and their accessory adhesion molecules in mammary carcinomas: loss of polarization in poorly differentiated tumors. Hum Pathol. 1992;23:1159–1166. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(92)90034-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Felding-Habermann B, et al. Integrin activation controls metastasis in human breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:1853–1858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.4.1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hughes PE, et al. Breaking the integrin hinge. A defined structural constraint regulates integrin signaling. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6571–6574. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.12.6571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bergers G, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 triggers the angiogenic switch during carcinogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:737–744. doi: 10.1038/35036374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karamysheva AF. Mechanisms of angiogenesis. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2008;73:751–762. doi: 10.1134/s0006297908070031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kunz M, Ibrahim SM. Molecular responses to hypoxia in tumor cells. Mol Cancer. 2003;2:23. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-2-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braunstein S, et al. A hypoxia-controlled cap-dependent to cap-independent translation switch in breast cancer. Mol Cell. 2007;28:501–512. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gray MJ, et al. HIF-1alpha, STAT3, CBP/p300 and Ref-1/APE are components of a transcriptional complex that regulates Src-dependent hypoxia-induced expression of VEGF in pancreatic and prostate carcinomas. Oncogene. 2005;24:3110–3120. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kevil CG, et al. Translational regulation of vascular permeability factor by eukaryotic initiation factor 4E: Implications for tumor angiogenesis. Int J Cancer. 1996;65:785–790. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960315)65:6<785::AID-IJC14>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zygalaki E, et al. Real-time reverse transcription-PCR quantification of vascular endothelial growth factor splice variants. Clin Chem. 2005;51:1518–1520. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.046987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Benedetti A, Harris AL. eIF4E expression in tumors: its possible role in progression of malignancies. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1999;31:59–72. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(98)00132-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sonenberg N, Gingras AC. The mRNA 5′ cap-binding protein eIF4E and control of cell growth. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:268–275. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80150-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Witz IP. Tumor-microenvironment interactions: Dangerous liaisons. Adv Cancer Res. 2008;100:203–229. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(08)00007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo P, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor isoforms display distinct activities in promoting tumor angiogenesis at different anatomic sites. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8569–8577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blouw B, et al. The hypoxic response of tumors is dependent on their microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:133–146. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00194-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bachelder RE, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor is an autocrine survival factor for neuropilin-expressing breast carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5736–5740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huveneers S, et al. Integrin alpha v beta 3 controls activity and oncogenic potential of primed c-Src. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2693–2700. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meier F, et al. The RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways present molecular targets for the effective treatment of advanced melanoma. Front Biosci. 2005;10:2986–3001. doi: 10.2741/1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vellon L, Menendez JA, Lupu R. A bidirectional “alpha (v) beta(3) integrin-ERK1/ERK2 MAPK” connection regulates the proliferation of breast cancer cells. Mol Carcinog. 2006;45:795–804. doi: 10.1002/mc.20242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Illario M, et al. Fibronectin-induced proliferation in thyroid cells is mediated by alphavbeta3 integrin through Ras/Raf-1/MEK/ERK and calcium/CaMKII signals. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:2865–2873. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chung J, Bachelder RE, Lipscomb EA, Shaw LM, Mercurio AM. Integrin (alpha 6 beta 4) regulation of eIF-4E activity and VEGF translation: a survival mechanism for carcinoma cells. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:165–174. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200112015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pabla R, et al. Integrin-dependent control of translation: engagement of integrin alphaIIbbeta3 regulates synthesis of proteins in activated human platelets. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:175–184. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.1.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Avdulov S, et al. Activation of translation complex eIF4F is essential for the genesis and maintenance of the malignant phenotype in human mammary epithelial cells. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:553–563. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen EI, et al. Adaptation of energy metabolism in breast cancer brain metastases. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1472–1486. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Felding-Habermann B, Habermann R, Saldivar E, Ruggeri ZM. Role of beta3 integrins in melanoma cell adhesion to activated platelets under flow. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5892–5900. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.