Abstract

Among the most fundamental issues in cognitive neuroscience is how the brain may be organized into process-specific and stimulus-specific regions. In the episodic memory domain, most functional neuroimaging studies have focused on the former dimension, typically investigating the neural correlates of various memory processes. Thus, there is little information about what role stimulus-specific brain regions play in successful memory processes. To address this issue, the present event-related fMRI study used a factorial design to focus on the role of stimulus-specific brain regions, such as the fusiform face area (FFA) and parahippocampal place area (PPA) in successful encoding and retrieval processes. Searching within regions sensitive to faces or places, we identified areas similarly involved in encoding and retrieval, as well as areas differentially involved in encoding or retrieval. Finally, we isolated regions associated with successful memory, regardless of stimulus and process type. There were three main findings. Within face sensitive regions, anterior medial PFC and right FFA displayed equivalent encoding and retrieval success processes whereas left FFA was associated with successful encoding rather than retrieval. Within place sensitive regions, left PPA displayed equivalent encoding and retrieval success processes whereas right PPA was associated with successful encoding rather than retrieval. Finally, medial temporal and prefrontal regions were associated with general memory success, regardless of stimulus or process type. Taken together, our results clarify the contribution of different brain regions to stimulus- and process-specific episodic memory mechanisms.

INTRODUCTION

Episodic memory refers to the encoding and retrieval of personally experienced past events (Tulving, 1983), including memory for people and places. Functional neuroimaging studies have associated successful episodic memory with a complex network of brain regions, including the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and the medial temporal lobes (MTL) (Cabeza & Nyberg, 2000). Most functional neuroimaging studies have focused on process-specific activations, such as encoding vs. retrieval differences within PFC (Nyberg, Cabeza, & Tulving, 1996; Habib, Nyberg, & Tulving, 2003) and the MTL (Lepage, Habib, & Tulving, 1998). Very few studies have investigated how encoding vs. retrieval differences interact with stimulus-specific differences, such as differences between verbal and nonverbal stimuli (Kelley et al., 1998; McDermott, Buckner, Petersen, Kelley, & Sanders, 1999; Wagner, Poldrack et al., 1998). Event-related functional MRI (fMRI) studies comparing activity for remembered vs. forgotten items have shown that successful encoding and retrieval activity can be both general and stimulus-specific (Prince, Daselaar, & Cabeza, 2005). The present fMRI study investigates this issue within the visual domain by focusing on brain regions that have been strongly associated with processing places and faces.

Processing of places has been associated with activation in a region in the posterior parahippocampal gyrus (Epstein & Kanwisher, 1998) known as the parahippocampal place area (PPA), and processing of faces with regions within the fusiform gyrus (Kanwisher, McDermott, & Chun, 1997; Puce, Allison, Gore, & McCarthy, 1995) and the occipital cortex (Rossion, Schiltz, & Crommelinck, 2003) known as the fusiform face area (FFA) and occipital face area (OFA), respectively. These specialized place and face regions are frequently characterized as stimulus-specific or as having a content preference in that they rapidly and automatically support the perception of those stimuli, but not other stimuli such as objects, birds, cars, or bodies, although this is a matter of some debate in the literature (Gauthier, Skudlarski, Gore, & Anderson, 2000; Grill-Spector, Sayres, & Ress, 2006; Haxby et al., 2001). However, other imaging evidence suggests that stimulus-specific regions might not simply respond to the presence of specific content, but also additionally be modulated by focused attention (Wojciulik, Kanwisher, & Driver, 1998), repetition (Henson, Shallice, Gorno-Tempini, & Dolan, 2002), and novelty or mnemonic status (Epstein et al., 1999; Hayes, Nadel, & Ryan, 2007; Hayes, Ryan, Schnyer, & Nadel, 2004; Kuskowski & Pardo, 1999; Rossion, Schiltz, & Crommelinck, 2003; Turk-Browne, Yi, & Chun, 2006). Thus, it is an open question whether activity in these regions is modulated by successful memory processes during encoding and/or during retrieval.

To investigate this issue, we scanned participants using event-related fMRI while encoding and retrieving faces and places. We used a factorial design with three factors: (1) stimulus type: faces vs. places, (2) process type: encoding vs. retrieval, and (3) memory success: remembered vs. forgotten. We defined stimulus-specific regions as those showing face-place differences and searched within those regions for memory effects during encoding, retrieval, or both.

The current analysis had three main goals. The first two were to identify stimulus-specific memory success effects that are similar for encoding and retrieval as well as stimulus-specific memory success effects that differ for encoding vs. retrieval – for both (1) faces and (2) places. We expected to find stimulus-specific activation in the FFA and PPA for faces and places, respectively. Although studies have reported a role for stimulus-specific regions in successful encoding (e.g. Brewer et al., 1998, Turk-Browne et al., 2006), it is not clear whether these two regions (PPA and FFA) are also involved in successful retrieval. One possibility is that reactivation, in the exact areas that support better encoding, would also benefit retrieval. Another possibility is that enhanced activity in stimulus-specific regions only occurs for encoding success. A third goal (3) was to identify general memory success effects that are equivalent for both types of stimuli and both types of memory processes. In opposition to specialization for stimulus, regions involved in memory success as a general phenomenon, regardless of stimulus or process type represent the most fundamental cognitive operations. Based on studies of subsequent memory (Kirchhoff, Wagner, Maril, & Stern, 2000; Wagner, Schacter et al., 1998), retrieval success (e.g. Eldridge, Knowlton, Furmanski, Bookheimer, & Engel, 2000), and encoding-retrieval conjunctions (Prince, Daselaar, & Cabeza, 2005), MTL regions, such as the hippocampus, and PFC regions were predicted to play such a role in general memory success.

METHODS

Subjects

Nineteen right-handed participants (10 females), all students at Duke University, with an average age of 22.7 years (SD = 4.1) were scanned and paid for their participation. Data from three participants were excluded, one due to equipment malfunction and two due to inadequate behavioral performance (overall response rate less than two-thirds). Written informed consent was obtained for each participant and the study met all criteria for approval of the Duke University Institutional Review Board.

Stimulus materials

The stimuli consisted of 144 photographs of places and 144 photographs of faces. Photos of places consisted of common indoor (50%) and outdoor (50%) scenes, which were obtained from an online database (http://www.corbis.com) and set to a standard size of 576 × 432. Face photos were obtained, with permission, from an online database (http://agingmind.cns.uiuc.edu/facedb) and represent the age spectrum from young adults to older adults as well as different racial groups (Minear & Park, 2004). The database contains some faces with various emotional expressions, however only faces with neutral expressions (as determined by Minear and Park) were used in the current experiment. Faces were set on a solid black background. White fixation crosses were shown between successive stimuli.

Procedures

The fMRI study was completed in a single session and consisted of two place and three face runs for encoding (intentional) and the same number of runs for retrieval. There were also six total runs in which faces were paired with places (data not reported here). Overall run order was fixed based on pilot testing designed to elicit equivalent performance across tasks. Trial timing and jitter durations during encoding were also determined by pilot testing in order to attain similar performance. Place encoding trials were 1475 milliseconds (ms) and face encoding trials were 2475ms in duration, both followed by a variable jitter ranging from 1275 to 1775ms (mean jitter length was 1525ms) and required a 4-point rating of pleasantness or friendliness for places and faces, respectively. Retrieval trials in all conditions were 3000ms in duration, followed by a variable jitter ranging from 1500ms to 2500ms (mean jitter length was 2000ms) and required a combined old/new confidence response (definitely old, probably old, probably new, definitely new). Participants were encouraged to respond within the allotted period. The total number of old study trials was 108, yielding a potential total of 108 encoding trials and 108 retrieval trials per condition. Additionally, 36 new trials, per condition, were included during retrieval. Finger order for button press responses was counterbalanced across participants at both encoding and retrieval.

In each stimulus condition, the functional activity was measured separately for subsequent hits and subsequent misses during encoding. Encoding Success Activity (ESA) was identified by comparing study-phase activity for subsequently remembered vs. subsequently forgotten trials (Wagner et al., 1998; Brewer et al., 1998). Similarly, Retrieval Success Activity (RSA) was identified by comparing test-phase activity for remembered (hit) and forgotten (miss) trials. Additionally, General Success Activity (GSA) was defined as regions showing a significant main effect of memory success (remembered > forgotten), without significant effects of memory process (ESA vs. RSA) or stimulus content (face vs. place).

Scanning & Image Processing

Images were collected from a 4T GE scanner. Scanner noise was reduced with ear plugs and head motion was reduced with foam pads and headbands. Stimuli were presented with LCD goggles (Resonance Technology, Inc.), and behavioral responses were recorded with a 4-key fiber-optic response box (Resonance Technology, Inc.). Anatomical scanning started with a T1-weighted sagittal localizer series. The anterior (AC) and posterior commissures (PC) were identified in the mid-sagittal slice, and 34 contiguous oblique slices were prescribed parallel to the AC-PC plane. High-resolution T1-weighted structural images were acquired with a 450-ms repetition time (TR), a 9-ms echo time (TE), a 24-cm field of view (FOV), a 2562 matrix, and a slice thickness of 1.9-mm. Functional scanning employed an inverse spiral sequence with a 1500-ms TR, a 31-ms TE, a 24-cm FOV, a 642 image matrix, and a 60° flip angle. Thirty-four contiguous slices were acquired with the same slice prescription as the anatomical images. Slice thickness was 3.75-mm, resulting in cubic 3.75-mm3 isotropic voxels.

Data were processed using SPM2 (Statistical Parametric Mapping; Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm). The first six volumes were discarded to allow for scanner equilibration. Time-series were then corrected for differences in slice acquisition times, and realigned. Functional images were spatially normalized to a standard stereotactic space, using the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) templates implemented in SPM2 and resliced to a resolution of 3.75 mm3. The coordinates were later converted to Talairach and Tournoux’s space (Talairach & Tournoux, 1988) for reporting in Tables. Finally, the volumes were spatially smoothed using an 8-mm isotropic Gaussian kernel and proportionally scaled to the whole-brain signal.

fMRI analyses

For each participant, trial-related activity was assessed by convolving a vector of the onset times of the stimuli with a synthetic hemodynamic response function. The general linear model, as implemented in SPM2, was used to model the effects of interest and other confounding effects (e.g., head movement and magnetic field drift). Statistical Parametric Maps were identified for each participant by applying linear contrasts to the parameter estimates (beta weights) for the events of interest, resulting in a t-statistic for every voxel. In both stimulus conditions, we coded four trial types: subsequent hits, subsequent misses, retrieval hits, and retrieval misses. Subsequent hit trials were determined by matching the high-confidence retrieval hit responses at test to the relevant trials at encoding. Similar to other subsequent memory studies, only high-confidence retrieval hits were considered subsequent hits and all other trials were modeled as subsequent misses (Otten, Quayle, Akram, Ditewig, & Rugg, 2006; Schon, Hasselmo, Lopresti, Tricarico, & Stern, 2004). The mean number of trials contributing to each trial type in the design was 52 (standard deviation = 14.5).

Individual subject contrasts were submitted to a 2 (stimulus: face vs. place) × 2 (process type: encoding vs. retrieval) × 2 (memory success: remembered vs. forgotten) ANOVA using SPM5. As the first step in the analyses we identified main effects for stimulus (face > place and place > face) and memory success (remembered > forgotten) at a very conservative threshold, p < 0.05 false discovery rate (FDR) corrected (Genovese, Lazar, & Nichols, 2002) (extent threshold of 2 voxels). Then, within this strict set of voxels, we identified both 2- and 3-way interactions at p<0.05, uncorrected (extent threshold = 2). In order to ensure that each effect was driven by that specific effect (and no other) we used extensive inclusive and exclusive masking (Eldar, Ganor, Admon, Bleich, & Hendler, 2007). For example, in order to ensure that 2-way interactions were not driven by 3-way interactions, we inclusively masked main effects with the former and exclusively masked out the latter. When identifying regions showing greater memory success (both ESA and RSA) for faces than places, we inclusively masked this 2-way interaction with simple face ESA and face RSA contrasts (to ensure the interaction was not driven by inverse memory effects for places) and we exclusively masked with 3-way interactions (e.g., face > place memory success but only during encoding). Three-way interactions were inclusively masked with the relevant simple effect explaining the interactions. For example, the main effect of stimulus was masked inclusively with face ESA, face > place encoding success, and face ESA > face RSA. Finally, general memory success activity was assessed with inclusive masking for all four simple effects (face ESA, place ESA, face RSA, and place RSA) and exclusive masking for all interactions and contrasts contributing to those interactions.

RESULTS

Behavioral data

Table 1 lists the proportion of high and low confidence responses for correct (hit, correct rejection) and incorrect (miss, false alarm) place and face trials. There was no significant difference (p > 0.15) between the proportion of high confidence hit responses for places versus faces. Confidence had a strong effect on accuracy for old items, with 90.2% accuracy for high confidence responses, but only 59.7% accuracy for low confidence responses. This pattern justifies including only high-confidence responses in the hit category in fMRI analyses. T-tests comparing place versus face reaction times for high confidence hits revealed no significant differences at encoding (p > 0.4) or retrieval (p > 0.95).

Table 1.

Behavioral results: mean proportion of responses and RTs in milliseconds

| Hi Conf. | Lo Conf. | Total | Hi Conf. | Lo Conf. | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old Trials | Hits | Misses | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Place | 0.58 | 0.20 | 0.78 | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.22 |

| Encoding RTs | 1582 | 1488 | 1533 | 1539 | ||

| Retrieval RTs | 1530 | 2258 | 1980 | 2406 | ||

| Face | 0.53 | 0.26 | 0.79 | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.21 |

| Encoding RTs | 1653 | 1721 | 1750 | 1721 | ||

| Retrieval RTs | 1528 | 2155 | 1990 | 2224 | ||

| New Trials | Correct Rejections | False Alarms | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Place | 0.45 | 0.39 | 0.84 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.16 |

| Face | 0.43 | 0.39 | 0.82 | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.18 |

RT: Response Times; Hi: High; Lo: Low; Conf: Confidence

fMRI data

Table 2 lists the main effects of stimulus type, 2-way stimulus type × memory success interactions, and 3-way stimulus type × process type × memory success interactions (separated by stimulus: face, place). All interactions are inclusively masked with the corresponding main effects and exclusively masked with alternative interactions (as outlined in the Methods). Table 3 lists the main effects of success, collapsed across both stimulus and process and exclusively masked with all interactions.

Table 2.

ANOVA results: main effects of stimulus, 2- and 3-way interactions

| Main effect of Stimulus | Stimulus × Success interactions | Stim × Process × Success interactions | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | BA | x | y | z | t | x | y | z | t | x | y | z | t | |

| Face | ||||||||||||||

| fusiform gyrus (FFA) | R | 37 | 48 | −48 | −17 | 6.07 | 45 | −63 | −13 | 2.46 | ||||

| fusiform gyrus (FFA) | L | 37 | −45 | −52 | −20 | 5.75 | −45 | −59 | −23 | 2.85 (E) | ||||

| inferior occipital gyrus (OFA) | R | 18/19 | 45 | −80 | −6 | 5.64 | ||||||||

| inferior occipital gyrus (OFA) | L | 18/19 | −37 | −84 | −12 | 4.99 | ||||||||

| precuneus | M | 7 | 4 | −60 | 35 | 4.67 | ||||||||

| anterior medial PFC | R | 10 | 11 | 58 | 4 | 4.02 | 11 | 55 | 8 | 4.53 | ||||

| ventrolateral PFC | R | 47 | 48 | 25 | −4 | 4.01 | ||||||||

| middle temporal gyrus | R | 21 | 52 | −15 | −9 | 3.67 | ||||||||

| Place | ||||||||||||||

| lingual gyrus | L | 18 | −11 | −88 | −2 | 13.04 | ||||||||

| lingual gyrus | M | 18 | 7 | −87 | 4 | 13.02 | ||||||||

| parahippocampal gyrus (PPA) | R | 36/37 | 30 | −48 | −4 | 12.87 | 33 | −44 | −7 | 3.89 (E) | ||||

| R | 19/30 | 15 | −40 | −1 | 2.30 | |||||||||

| parahippocampal gyrus (PPA) | L | 36/37 | −30 | −44 | −7 | 12.86 | −30 | −44 | −4 | 2.28 (E) | ||||

| L | 35/36 | −30 | −33 | −14 | 3.90 | |||||||||

| L | 19/30 | −15 | −44 | 2 | 2.89 | |||||||||

| lingual gyrus | L | 18 | −15 | −84 | −9 | 12.66 | ||||||||

| retrosplenial cortex (RSC) | R | 29/30 | 15 | −54 | 13 | 10.62 | 7 | −54 | 13 | 3.83 | 15 | −54 | 13 | 3.34 (E) |

| parieto-occipital sulcus (POS) | R | 18 | 11 | −94 | 15 | 10.41 | ||||||||

| occipitotemporal cortex | L | 19/39 | −30 | −90 | 19 | 9.05 | −37 | −82 | 29 | 3.71 | ||||

| occipitotemporal cortex | R | 19/39 | 33 | −83 | 22 | 8.98 | 37 | −79 | 32 | 4.79 | ||||

| 48 | −72 | 25 | 2.78 | |||||||||||

| parieto-occipital sulcus (POS) | L | 18/19 | −15 | −94 | 22 | 8.45 | −26 | −82 | 36 | 2.52 | ||||

| retrosplenial cortex (RSC) | L | 31 | −15 | −58 | 13 | 8.42 | ||||||||

| precuneus | R | 7 | 22 | −71 | 39 | 3.62 | 22 | −67 | 42 | 2.70 (E) | ||||

PFC: prefrontal cortex; H: hemisphere; L: left; R: right; M: midline; BA: Brodmann’s Area; E, Encoding

Table 3.

General Memory Effects

| H | BA | x | y | z | t | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hippocampus | R | 19 | −12 | −12 | 5.65 | |

| L | −19 | −12 | −12 | 5.32 | ||

| fusiform gyrus | R | 37 | 52 | −52 | −13 | 5.19 |

| ventrolateral PFC | L | 47 | −48 | 36 | −2 | 4.67 |

| anterior PFC | M | 9 | −7 | 56 | 29 | 4.61 |

| dorsal PFC | M | 8 | −7 | 46 | 43 | 4.55 |

| fusiform gyrus | L | 37 | −26 | −48 | −14 | 4.03 |

| ventrolateral PFC | L | 44 | −33 | 9 | 28 | 3.82 |

PFC: prefrontal cortex; H: hemisphere; L: left; R: right; M: midline; BA: Brodmann’s Area

Memory effects on face-sensitive regions

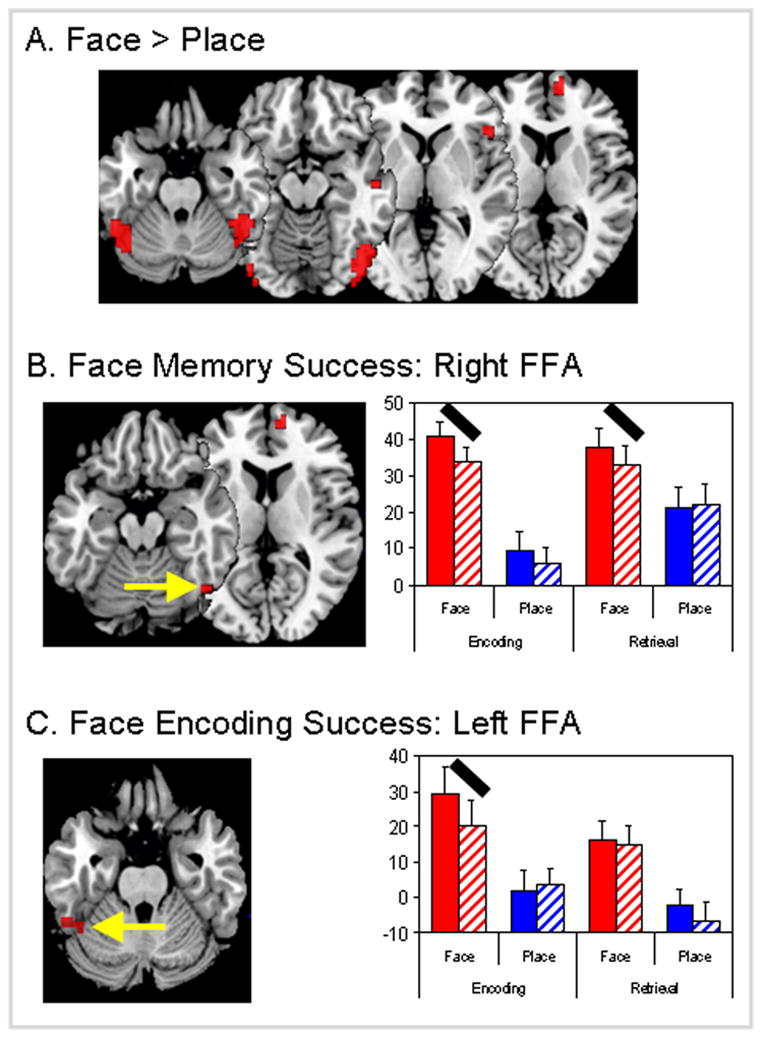

As shown by Table 2 and Figure 1A, the main effect of face vs. place yielded bilateral fusiform cortex (specifically, FFA), inferior occipital cortex (OFA), precuneus, anterior medial PFC, right ventrolateral PFC and right middle temporal gyrus. The fusiform gyrus and occipital cortex regions closely match previously reported coordinates for FFA and OFA (peak Talairach coordinates: right FFA = 48, −48, −17, left FFA = −45, −52, −20, right OFA = 45, −80, −6, left OFA = −37, −84, −12).

Figure 1.

Brain regions showing effects of (a) stimulus (face vs. place), (b) stimulus × success (face memory) interactions and (c) stimulus × success × process (face encoding success) interactions. Y-axis unit for graphs is the fMRI effect size (parameter estimate or beta weight with standard error bars). Red bars = face stimulus and blue bars = place stimulus, solid bars = memory success, hatched bars = memory failure. FFA = fusiform face area. Black oblique lines highlight the effects driving 2-way or 3-way interactions.

Within these face-sensitive regions, we identified regions showing memory effects. As listed in Table 2, clusters in the right FFA and medial PFC showed significant 2-way stimulus type × memory success interactions but not 3-way interactions involving process type. As shown by the bar graphs in Figure 1B, right FFA showed greater activity for remembered than forgotten trials both during encoding and during retrieval. Confirming that the memory success effect was similar for encoding and retrieval, a repeated measures ANOVA of the beta values from the right FFA yielded significant effects of stimulus (p < 0.0005) and stimulus × success interaction (p < 0.05), but the 3-way interaction (stimulus × success × process) was not significant (p > 0.35). Thus, greater activity within right FFA contributed to both successful encoding and retrieval of faces.

In contrast, left FFA exhibited a significant 3-way interaction (see Table 2). As illustrated by bar graphs in Figure 1C, this 3-way interaction reflected a remember-forgotten difference during encoding but not during retrieval. A repeated measures ANOVA of the beta values from the left FFA resulted in a significant effect of stimulus (p < 0.005), a nonsignificant stimulus × success interaction (p > 0.15) and, critically, a significant stimulus × success × process interaction (p < 0.05). Thus, left FFA activity contributed to the successful encoding of faces but not to the successful retrieval of faces.

Whereas right and left FFA showed significant memory effects, bilateral OFA showed greater activity for faces than places but no significant interactions with memory success (see Table 2). This pattern suggests that OFA contributes to face processing but not to face memory. The involvement of this region in face processing is consistent with evidence that this region plays a role in face feature analysis by way of a feedback mechanism from the fusiform gyrus (Rossion et al., 2003; Steeves et al., 2006).

No face-sensitive region showed a 3-way interaction with greater contributions to memory success during retrieval than during encoding. This finding suggests that the role of face-sensitive regions to memory for faces is more specialized for encoding.

Memory effects on place-sensitive regions

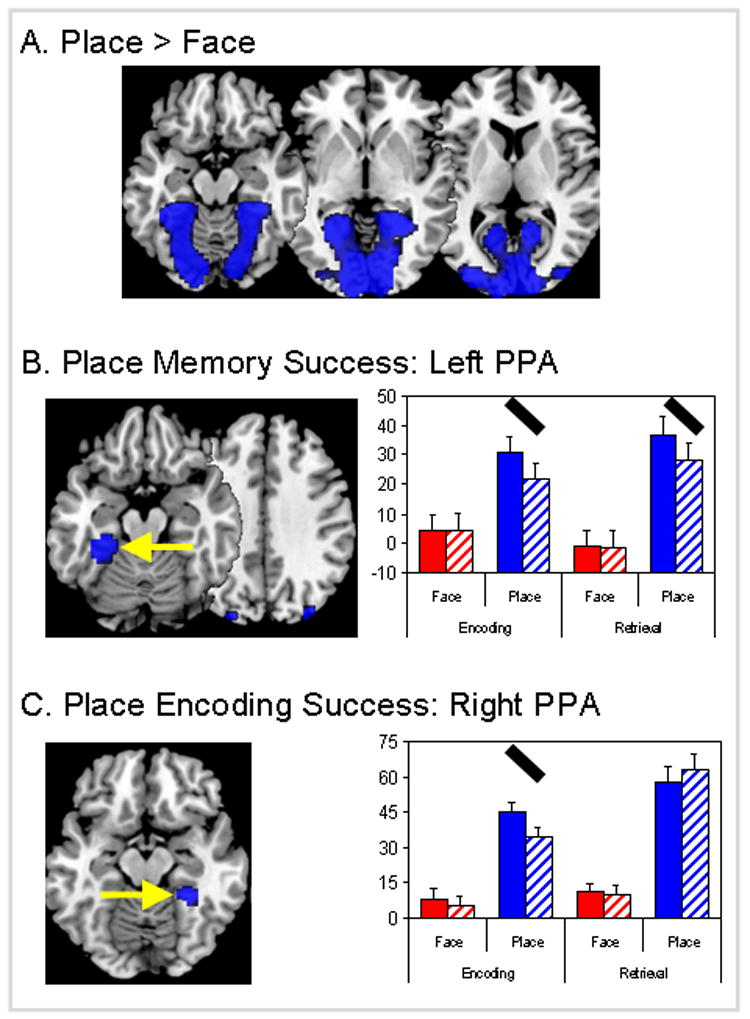

As shown by Table 2 and Figure 2A, places yielded greater activity than faces in a large network of brain regions, covering occipitotemporal and occipitoparietal regions. The parahippocampal gyrus regions closely match previously reported coordinates for PPA (peak Talairach coordinates: right PPA = 30, −48, −4, left PPA = −30, −44, −7).

Figure 2.

Brain regions showing effects of (a) stimulus (place vs. face), (b) stimulus × success (place memory) interactions and (c) stimulus × success × process (place encoding success) interactions. Y-axis unit for graphs is the fMRI effect size (parameter estimate or beta weight with standard error bars). Red bars = face stimulus and blue bars = place stimulus, solid bars = memory success, hatched bars = memory failure. PPA = parahippocampal place area. Black oblique lines highlight the effects driving 2-way or 3-way interactions.

Within place-sensitive regions, we identified regions showing memory effects. As listed in Table 2, clusters in the PPA (left > right), retrosplenial cortex, occipitotemporal cortex, and parieto-occipital sulcus (POS) showed significant 2-way stimulus × success interactions. Some of these regions did not show reliable 3-way interactions, indicating that they had similar contributions to encoding success and retrieval success. As illustrated by the bar graphs in Figure 2B, one of these regions was the left PPA, which showed greater activity for remember than forgotten trials both during encoding and during retrieval. Confirming that the memory success effect was similar for encoding and retrieval, a repeated measures ANOVA of the beta values from the left PPA resulted in significant effects of stimulus (p < 0.005) and stimulus × success interaction (p < 0.0001), but the 3-way interaction (stimulus × process × success interaction) was not significant (p > 0.8). Thus, greater activity within left PPA contributed to both successful encoding and retrieval of places.

In contrast, other clusters in the PPA (right > left), the retrosplenial cortex and the precuneus exhibited a significant 3-way stimulus × success × process interaction (see Table 2). As illustrated by bar graphs in Figure 2C, this 3-way interaction reflected a remember-forgotten difference during encoding but not during retrieval. A repeated measures ANOVA of the beta values from the right PPA resulted in a significant effect of stimulus (p < 0.0001), a nonsignificant stimulus × success interaction (p > 0.45) and critically, a significant stimulus × success × process interaction (p < 0.001). Thus, right PPA activity contributed to the successful encoding but not to the successful retrieval of places.

No place-sensitive region showed a 3-way interaction with greater contributions to memory success during retrieval than during encoding. This finding suggests that the role of place-sensitive regions to memory for places is more specialized for encoding.

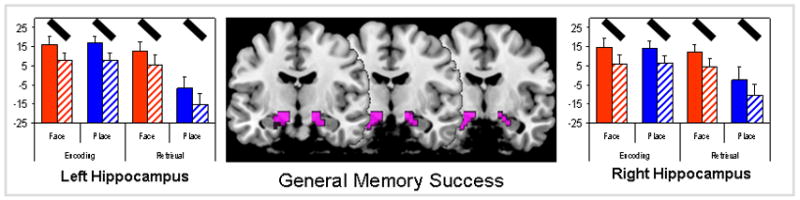

General Memory Success Effects

Finally, we identified regions that showed significant main effects of memory (remembered > forgotten) but no reliable 2-way or 3-way interaction. These regions contribute to memory success regardless of stimulus type (place vs. face) or process type (encoding vs. retrieval). As listed in Table 3, these regions were found within MTL, bilateral fusiform gyri, left ventrolateral PFC, and other PFC regions. The strongest effects were those in the hippocampus. As illustrated by Figure 3, the left and right hippocampi showed greater activity for remembered than forgotten trials for both faces and places and for both encoding and retrieval. This finding is consistent with the fundamental role of the hippocampus in episodic memory.

Figure 3.

Brain regions showing a main effect of general memory success, exclusive of all memory interactions. Y-axis unit for graphs is the fMRI effect size (parameter estimate or beta weight with standard error bars). Red bars = face stimulus and blue bars = place stimulus, solid bars = memory success, hatched bars = memory failure. Black oblique lines highlight the individual memory success effects.

DISCUSSION

The study yielded three main findings. First, within face-sensitive brain regions, right FFA was associated with successful memory during both encoding and during retrieval, whereas left FFA was associated with successful memory only during encoding. Another region contributing to face encoding and retrieval was anterior medial PFC. Second, within place-sensitive brain regions, left PPA was associated with successful memory during both encoding and during retrieval, whereas right PPA was associated with successful memory only during encoding. No face- or place-sensitive region had a greater contribution to successful retrieval than to successful encoding. Finally, general memory success, regardless of stimulus type or process type was found most strongly in the hippocampus. Other regions contributing to general memory success included several left PFC areas. These three findings are discussed in separate sections below.

Face-specific memory effects

Our first main finding was that right FFA, a region identified as selectively sensitive to faces, was also associated with successful memory during both encoding and during retrieval. Left FFA, while also showing selectivity for faces, was only associated with successful memory during encoding. The right fusiform has been reported to support processing unique instances of nameable stimuli (Koutstaal et al., 2001; Simons, Koutstaal, Prince, Wagner, & Schacter, 2003). In the current experiment where a semantic label is absent, the right FFA may process the unique perceptual features of novel faces, forming a holistic representation of each face (person identity). Moreover, reactivation of this region is associated with memory success, suggesting that enhanced processing supports memory for the identification of the face and may store or represent perceptual features related to person identity. What is unclear is whether memory success results from processing specific perceptual details or the integration of unique features into a holistic representation.

In contrast with right FFA, left FFA yielded successful memory activity for faces during encoding (ESA) but not during retrieval (RSA). Thus, results indicate that the left FFA displays additional encoding enhancing properties that are not associated with successful retrieval. Left fusiform has been linked to lexical/semantic processing of objects (Simons, Koutstaal, Prince, Wagner, & Schacter, 2003). Although novel faces are not nameable, participants may be encoding a particular facial feature (e.g. hair, eyes, nose, mouth) and how it differs from a prototypical norm, potentially helping to individuate that particular face from the ongoing set, but only during encoding (suggesting that only immediate processing but not storage occurs). It should be reiterated that significant stimulus specific activity was observed in left FFA at retrieval; however, differential activity was not observed for hits and misses.

In addition to right FFA, another region that contributed to both the encoding and retrieval of faces was anterior medial PFC (BA 10). This regions sits within a larger anterior region of the rostral medial frontal cortex that has been implicated in mentalizing, self-knowledge, and person perception (Amodio & Frith, 2006). It is possible that in the current experiment, all three processes are involved. Whereas the task involved memory for the faces of others, one successful strategy may involve interrogation of self-knowledge in relation to them (e.g., would I like to spend time with this person?). This is particularly plausible given the encoding instructions to rate the friendliness of each face. At any rate, very little is known regarding the role of medial BA10 in face memory, and further research is warranted to flesh out its exact role in face memory success.

Place-specific memory effects

Successful place memory was associated with PPA (left > right), bilateral occipitotemporal, and retrosplenial/parieto-occipital sulcus (RSC/POS) regions. The left PPA and RSC/POS regions have been reported in many previous studies and have typically been attributed to place sensitive processing (Epstein & Higgins, 2006; Epstein, Higgins, Parker, Aguirre, & Cooperman, 2006; Epstein & Kanwisher, 1998; Epstein, Parker, & Feiler, 2007) as well as contextual associations (Aminoff, Gronau, & Bar, 2007; Bar & Aminoff, 2003; Bar, Aminoff, & Ishai, 2007; Bar, Aminoff, & Schacter, 2008). Either framework may be suitable for understanding the general results reported here. That is, the current results suggest that place memory success is supported by the enhanced processing of places and the formation and retrieval of contextual associations within places as compared to the faces. Like the face results, it is clear from place analyses that unique networks are associated with not just perceptual sensitivity, but also memory success for particular stimuli.

Right PPA, retrosplenial, and parieto-occipital sulcus and bilateral occipitotemporal regions were all found to be associated with ESA but not with RSA. The differential involvement of PPA in encoding may reflect a primary role of this region in enhancing novelty effects associated with perceptual processing of places. It is important to note that although this region did not exhibit differential activity for hits and misses at retrieval it remained active during stimulus-specific processing. This suggests that a region can help individuate a particular instance from an ongoing set, at encoding (above and beyond stimulus-sensitivity), and later respond in a stimulus-specific manner at retrieval with no mnemonic benefit. In this regard, regions in PPA displayed additional encoding enhancing properties, suggestive of an interaction between cognition and perception, which may depend on whether the level of processing is based on form (right) or semantic labeling (left).

The PPA lateralization difference fits with ideas from both the object identification/priming literature (Koutstaal et al., 2001; Marsolek, Kosslyn, & Squire, 1992; Marsolek, Schacter, & Nicholas, 1996; Simons, Koutstaal, Prince, Wagner, & Schacter, 2003) and the episodic memory literature (Burgess, Maguire, & O’Keefe, 2002; Garoff, Slotnick, & Schacter, 2005; Maguire et al., 1998) regarding the contribution of the right hemisphere to form-specific visual details as compared to the left hemisphere contribution to more abstract (gist-based) or episodic details. The current results suggest that while successful encoding of places may rely on both specific and general information, stage-independent successful memory for places may rely on gist-based or episodic information to a greater extent. The left lateralized PPA effects may also indicate the use of a semantic label that would serve to benefit both encoding and retrieval success, perhaps by storing and reactivating this information.

Modular Memory

In summary, this experiment showed place and face sensitive cortical regions to be associated not only with the perception, but also successful memory of these stimulus classes. These regions help to individuate visual information in a stimulus-specific manner and may operate at a gist- (right FFA, left PPA) versus item-based (left FFA, right PPA) level. We argue that stimulus-specific regions are associated with cognitive processing above and beyond perceptual identification, with right FFA and left PPA critical loci for representing people and places, respectively, in episodic memory. Additionally, regions including anterior medial PFC, retrosplenial cortex, and parieto-occipital sulcus are likely to support these representations.

By investigating episodic memory processes within regions displaying a content preference, we conclude that strong interactions occur between cognition and perception in these brain regions. One such type of interaction involves differential activation of the same regions during retrieval that were associated with successful encoding. These results not only support the fact that previously identified stimulus-specific regions or “modules” also contribute to memory success at encoding, but that reactivation of these regions also supports successful memory at retrieval. Reactivation in stimulus specific regions may support the retrieval of unique perceptual features of the item that allow specifically for recollection. Another type of interaction involves differential activation for successful encoding, more so than at retrieval. This activity may contribute to successful memory by identifying new items as novel (versus repeated as when encountered during retrieval). Factors including repetition, perceived novelty, and conscious effort are likely to influence whether and how robustly a stimulus-specific region responds and are important for future studies to investigate.

Strategic and mnemonic “guidance” or modulation of stimulus-specific regions is likely subserved by the MTL and PFC. These fundamental memory processes may set the ‘neural context’ for an episode, with regions in the left inferior frontal gyrus and left ventrolateral prefrontal cortex serving roles in the establishment, organization, and retrieval of suitable cues (Moscovitch & Winocour, 2002; Simons & Spiers, 2003). Multiple regions in the MTL are associated with memory success and are likely to operate in ways that are both dependent and independent of conscious response (Daselaar, Fleck, Prince, & Cabeza, 2006; Henke et al., 2003). Future research into consolidation effects on memory and the timing and requirements of retrieval tests should help to clarify the interactions between stimulus-independent and stimulus-specific regions.

Although we found some stimulus-specific regions that differentially contributed to encoding, no stimulus-specific region differentially contributed to retrieval. This suggests that within regions sensitive to a particular stimulus, there is no additional process specialization mechanism available for retrieval compared to that utilized at encoding. As such, the nature of memory success specialization within stimulus-specific regions appears to be for either equivalent effects at encoding and retrieval or for enhancement only at encoding. The source of the observed hemispheric lateralization differences for these specializations (faces = right FFA vs. left FFA, places = left PPA vs. right PPA) is an important issue to be addressed by future research.

Future studies will also help to clarify whether enhanced processing in stimulus-specific regions is driven by bottom-up perceptual aspects inherent to the stimuli or top-down modulation by means of other brain regions and/or strategic processing. Studies of working memory that have employed face and place stimuli as distractors during the delay period have shown that active suppression of such regions can occur, and can benefit performance when a stimulus from a different class is shown during the delay (Gazzaley, Cooney, McEvoy, Knight, & D’Esposito, 2005). Additional support for the idea of strategic control over stimulus-specific processing comes from a functional connectivity study (Summerfield et al., 2006) in which the authors found left dorsolateral PFC to potentially mediate top-down control of posterior stimulus-specific regions in association with successful encoding.

General memory effects

The brain regions associated with memory success regardless of stimuli and memory phases are likely to play the most fundamental role in mnemonic processing. Previously, we found a mid-posterior area within the left hippocampus that was both stimulus and process independent (Prince, et al., 2005). In the current study, we again found the MTL to be associated with general memory success. This included large bilateral foci in the anterior MTL, spanning the hippocampus, amygdala, and rhinal cortex. The bilateral nature of anterior MTL regions found in the current study suggests that pictorial stimuli likely differ from verbal stimuli not only at encoding (Kelley et al., 1998) but at retrieval as well. Anterior MTL activity has also been associated with novelty (Kirchhoff et al., 2000; Ranganath & Rainer, 2003) but the fact that this region was involved in both retrieval and encoding does not support the idea that it primarily responds to novelty. In addition to the anterior MTL, clusters in medial dorsal and left ventrolateral PFC displayed general memory success effects. These regions may contribute to visual and mnemonic individuation of an item from the larger ongoing set of stimuli.

Conclusions

The study yielded three main findings. First, right FFA was associated with face encoding and retrieval and left FFA with face encoding. Second, left PPA was associated with place encoding and retrieval and right PPA with place encoding. Finally, the hippocampus showed general success effects, independent of stimulus type or process type. To our knowledge, this is the first study to directly compare, within subjects, encoding and retrieval success for place and face stimuli. By directly comparing content and process types, this study further clarifies how and when specific brain regions contribute to episodic memory success.

Acknowledgments

We thank Christy Krupa and Amber Baptiste-Tarter for assistance in subject recruitment and scanning, Chih-Chen Wang for assistance in image processing and Scott Hayes for comments on the manuscript. This study was supported by NIH grants to R.C. (AG19731, AG23770).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aminoff E, Gronau N, Bar M. The parahippocampal cortex mediates spatial and nonspatial associations. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17(7):1493–1503. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amodio DM, Frith CD. Meeting of minds: the medial frontal cortex and social cognition. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7(4):268–277. doi: 10.1038/nrn1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar M, Aminoff E. Cortical analysis of visual context. Neuron. 2003;38(2):347–358. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar M, Aminoff E, Ishai A. Famous Faces Activate Contextual Associations in the Parahippocampal Cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2007 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar M, Aminoff E, Schacter DL. Scenes unseen: the parahippocampal cortex intrinsically subserves contextual associations, not scenes or places per se. J Neurosci. 2008;28(34):8539–8544. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0987-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess N, Maguire EA, O’Keefe J. The human hippocampus and spatial and episodic memory. Neuron. 2002;35(4):625–641. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00830-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabeza R, Nyberg L. Imaging Cognition II: An empirical review of 275 PET and fMRI studies. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2000;12:1–47. doi: 10.1162/08989290051137585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daselaar SM, Fleck MS, Prince SE, Cabeza R. The medial temporal lobe distinguishes old from new independently of consciousness. J Neurosci. 2006;26(21):5835–5839. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0258-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldar E, Ganor O, Admon R, Bleich A, Hendler T. Feeling the real world: limbic response to music depends on related content. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17(12):2828–2840. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldridge LL, Knowlton BJ, Furmanski CS, Bookheimer SY, Engel SA. Remembering episodes: a selective role for the hippocampus during retrieval. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3(11):1149–1152. doi: 10.1038/80671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein R, Harris A, Stanley D, Kanwisher N. The parahippocampal place area: recognition, navigation, or encoding? Neuron. 1999;23(1):115–125. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80758-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein R, Higgins JS. Differential Parahippocampal and Retrosplenial Involvement in Three Types of Visual Scene Recognition. Cereb Cortex. 2006 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein R, Higgins JS, Parker W, Aguirre GK, Cooperman S. Cortical correlates of face and scene inversion: A comparison. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44(7):1145–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein R, Kanwisher N. A cortical representation of the local visual environment. Nature. 1998;392(6676):598–601. doi: 10.1038/33402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein R, Parker WE, Feiler AM. Where am I now? Distinct roles for parahippocampal and retrosplenial cortices in place recognition. J Neurosci. 2007;27(23):6141–6149. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0799-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garoff RJ, Slotnick SD, Schacter DL. The neural origins of specific and general memory: the role of the fusiform cortex. Neuropsychologia. 2005;43(6):847–859. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier I, Skudlarski P, Gore JC, Anderson AW. Expertise for cars and birds recruits brain areas involved in face recognition. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3(2):191–197. doi: 10.1038/72140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzaley A, Cooney JW, McEvoy K, Knight RT, D’Esposito M. Top-down enhancement and suppression of the magnitude and speed of neural activity. J Cogn Neurosci. 2005;17(3):507–517. doi: 10.1162/0898929053279522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genovese CR, Lazar NA, Nichols T. Thresholding of statistical maps in functional neuroimaging using the false discovery rate. Neuroimage. 2002;15(4):870–878. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill-Spector K, Sayres R, Ress D. High-resolution imaging reveals highly selective nonface clusters in the fusiform face area. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9(9):1177–1185. doi: 10.1038/nn1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haxby JV, Gobbini MI, Furey ML, Ishai A, Schouten JL, Pietrini P. Distributed and overlapping representations of faces and objects in ventral temporal cortex. Science. 2001;293(5539):2425–2430. doi: 10.1126/science.1063736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SM, Nadel L, Ryan L. The effect of scene context on episodic object recognition: parahippocampal cortex mediates memory encoding and retrieval success. Hippocampus. 2007;17(9):873–889. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SM, Ryan L, Schnyer DM, Nadel L. An fMRI study of episodic memory: retrieval of object, spatial, and temporal information. Behav Neurosci. 2004;118(5):885–896. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.118.5.885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henke K, Mondadori CR, Treyer V, Nitsch RM, Buck A, Hock C. Nonconscious formation and reactivation of semantic associations by way of the medial temporal lobe. Neuropsychologia. 2003;41(8):863–876. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(03)00035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henson RN, Shallice T, Gorno-Tempini ML, Dolan RJ. Face repetition effects in implicit and explicit memory tests as measured by fMRI. Cereb Cortex. 2002;12(2):178–186. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanwisher N, McDermott J, Chun MM. The fusiform face area: a module in human extrastriate cortex specialized for face perception. J Neurosci. 1997;17(11):4302–4311. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-11-04302.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley WM, Miezin FM, McDermott KB, Buckner RL, Raichle ME, Cohen NJ, et al. Hemispheric specialization in human dorsal frontal cortex and medial temporal lobe for verbal and nonverbal memory encoding. Neuron. 1998;20(5):927–936. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80474-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchhoff BA, Wagner AD, Maril A, Stern CE. Prefrontal-temporal circuitry for episodic encoding and subsequent memory. J Neurosci. 2000;20(16):6173–6180. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-16-06173.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutstaal W, Wagner AD, Rotte M, Maril A, Buckner RL, Schacter DL. Perceptual specificity in visual object priming: functional magnetic resonance imaging evidence for a laterality difference in fusiform cortex. Neuropsychologia. 2001;39(2):184–199. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(00)00087-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuskowski MA, Pardo JV. The role of the fusiform gyrus in successful encoding of face stimuli. Neuroimage. 1999;9(6 Pt 1):599–610. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1999.0442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepage M, Habib R, Tulving R. Hippocampal PET activations of memory encoding and retrieval: The HIPER model. Hippocampus. 1998;8:313–322. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1998)8:4<313::AID-HIPO1>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire EA, Burgess N, Donnett JG, Frackowiak RS, Frith CD, O’Keefe J. Knowing where and getting there: a human navigation network. Science. 1998;280(5365):921–924. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsolek CJ, Kosslyn SM, Squire LR. Form-specific visual priming in the right cerebral hemisphere. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 1992;18(3):492–508. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.18.3.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsolek CJ, Schacter DL, Nicholas CD. Form-specific visual priming for new associations in the right cerebral hemisphere. Memory & Cognition. 1996;24(5):539–556. doi: 10.3758/bf03201082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott KB, Buckner RL, Petersen SE, Kelley WM, Sanders AL. Set-and code-specific activation in frontal cortex: an fMRI study of encoding and retrieval of faces and words. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 1999;11(6):631–640. doi: 10.1162/089892999563698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minear M, Park DC. A lifespan database of adult facial stimuli. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 2004;36(4):630–633. doi: 10.3758/bf03206543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otten LJ, Quayle AH, Akram S, Ditewig TA, Rugg MD. Brain activity before an event predicts later recollection. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9(4):489–491. doi: 10.1038/nn1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince SE, Daselaar SM, Cabeza R. Neural correlates of relational memory: successful encoding and retrieval of semantic and perceptual associations. J Neurosci. 2005;25(5):1203–1210. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2540-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puce A, Allison T, Gore JC, McCarthy G. Face-sensitive regions in human extrastriate cortex studied by functional MRI. J Neurophysiol. 1995;74(3):1192–1199. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.3.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossion B, Schiltz C, Crommelinck M. The functionally defined right occipital and fusiform “face areas” discriminate novel from visually familiar faces. Neuroimage. 2003;19(3):877–883. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00105-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schon K, Hasselmo ME, Lopresti ML, Tricarico MD, Stern CE. Persistence of parahippocampal representation in the absence of stimulus input enhances long-term encoding: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study of subsequent memory after a delayed match-to-sample task. J Neurosci. 2004;24(49):11088–11097. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3807-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Koutstaal W, Prince SE, Wagner AD, Schacter DL. Neural mechanisms of visual object priming: evidence for perceptual and semantic distinctions in fusiform cortex. Neuroimage. 2003;19(3):613–626. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00096-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summerfield C, Greene M, Wager T, Egner T, Hirsch J, Mangels J. Neocortical connectivity during episodic memory formation. PLoS Biol. 2006;4(5):e128. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talairach J, Tournoux P. A co-planar stereotactic atlas of the human brain. Stuttgart, Germany: Thieme; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Tulving E. Elements of Episodic Memory. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Turk-Browne NB, Yi DJ, Chun MM. Linking implicit and explicit memory: common encoding factors and shared representations. Neuron. 2006;49(6):917–927. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner AD, Poldrack RA, Eldridge LL, Desmond JE, Glover GH, Gabrieli JD. Material-specific lateralization of prefrontal activation during episodic encoding and retrieval. Neuroreport. 1998;9(16):3711–3717. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199811160-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner AD, Schacter DL, Rotte M, Koutstaal W, Maril A, Dale AM, et al. Building memories: remembering and forgetting of verbal experiences as predicted by brain activity. Science. 1998;281(5380):1188–1191. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5380.1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojciulik E, Kanwisher N, Driver J. Covert visual attention modulates face-specific activity in the human fusiform gyrus: fMRI study. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79(3):1574–1578. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.3.1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]