Abstract

Recent studies have identified several chloride (Cl−) channel genes in the heart, including CFTR, ClC-2, ClC-3, CLCA, Bestrophin, and TMEM16A. Gene targeting and transgenic techniques have been used to delineate the functional role of cardiac Cl− channels in the context of health and disease. It has been shown that Cl− channels may contribute to cardiac arrhythmogenesis, myocardial hypertrophy and heart failure, and cardioprotection against ischaemia–reperfusion. The study of physiological or pathophysiological phenotypes of cardiac Cl− channels, however, may be complicated by the compensatory changes in the animals in response to the targeted genetic manipulation. Alternatively, tissue-specific conditional or inducible knockout or knockin animal models may be more valuable in the phenotypic studies of specific Cl− channels by limiting the effect of compensation on the phenotype. The integrated function of Cl− channels may involve multi-protein complexes of the Cl− channel subproteome and similar phenotypes can be attained from alternative protein pathways within cellular networks, which are influenced by genetic and environmental factors. Therefore, the phenomics approach, which characterizes phenotypes as a whole phenome and systematically studies the molecular changes that give rise to particular phenotypes achieved by modifying the genotype (such as gene knockouts or knockins) under the scope of genome/proteome/phenome, may provide a more complete understanding of the integrated function of each cardiac Cl− channel in the context of health and disease.

In 1989, the Hume laboratory in the University of Nevada (Harvey & Hume, 1989) and the Gadsby laboratory at the Rockefeller University (Bahinski et al. 1989) independently discovered a cAMP-activated Cl− current in rabbit and guinea pig heart. This opened a new era of Cl− channel studies in the heart. At least eight different types of Cl− currents have been discovered in cardiac cells from different regions of the heart and in different species (Fig. 1) (Hume et al. 2000; Duan et al. 2005; Yamamoto & Ehara, 2006). The biophysical, pharmacological and molecular properties of Cl− channels in the heart have been well characterized and summarized in several excellent review articles (Harvey, 1996; Hiraoka et al. 1998; Hume et al. 2000; Baumgarten & Clemo, 2003). At the molecular level, all cardiac Cl− channels described so far may fall into the following Cl− channel gene families: (1) the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), which is a member of the adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily and may be responsible for the Cl− currents activated by protein kinase A (PKA) (ICl,PKA)(Bahinski et al. 1989; Harvey & Hume, 1989; Nagel et al. 1992), protein kinase C (PKC) (ICl,PKC) (Walsh & Long, 1994; Collier & Hume, 1995), and extracellular ATP (ICl,ATP) (Levesque & Hume, 1995; Duan et al. 1999b; Yamamoto-Mizuma et al. 2004a) in the heart; (2) ClC-2, which is a member of the ClC voltage-gated Cl− channel superfamily and may be responsible for the hyperpolarization- and cell swelling-activated inwardly rectifying Cl− current (ICl,ir) (Duan et al. 2000; Komukai et al. 2002a,b); (3) ClC-3, which is also a member of the ClC voltage-gated Cl− channel superfamily and may be responsible for the volume-regulated outwardly rectifying Cl− current (ICl,vol), including the basally activated (ICl,b) (Duan et al. 1992) and swelling activated (ICl,swell) components (Duan et al. 1992, 1995, 1997a,b, 1999a, 2001; Duan & Nattel, 1994; Hermoso et al. 2002; Wang et al. 2003; Yamamoto-Mizuma et al. 2004b); (4) CLCA-1, which was thought to be responsible for the Ca2+-activated Cl− current (ICl,Ca) (Collier et al. 1996; Britton et al. 2002; Xu et al. 2002); (5) Bestrophin, a candidate also for ICl,Ca (Hartzell et al. 2005); and (6) TMEM16, a novel candidate for ICl,Ca (Caputo et al. 2008; Schroeder et al. 2008; Yang et al. 2008). In addition, it has been recently demonstrated by several groups that the voltage-dependent anion channel 1 (VDAC1), which is predominantly expressed in the outer membrane of mitochondrion, is also expressed in the sarcolemmal membrane (Estevez et al. 2001; Baker et al. 2004; Xiang et al. 2007). A novel Cl− current activated by extracellular acidosis (ICl.acid) has also been observed in cardiac myocytes but the molecular identity for ICl.acid is currently not known (Fig. 1).

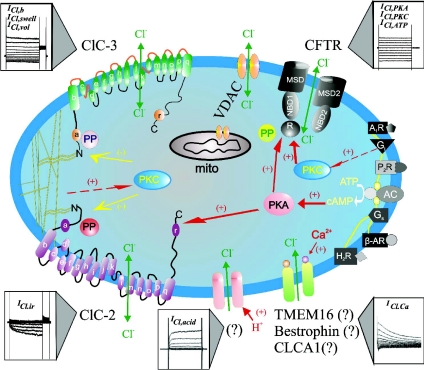

Figure 1. Schematic representation of Cl− channels in cardiac myocytes.

Cl− channels and their corresponding molecular entities or candidates are indicated. ClC-3, a member of voltage-gated ClC Cl− channel family, encodes Cl− channels that are volume regulated (ICl,vol) and can be activated by cell swelling (ICl,swell) induced by exposure to hypotonic extracellular solutions or possibly membrane stretch. ICl,b is a basally activated ClC-3 Cl− current. ClC-2, a member of voltage-gated ClC Cl− channel family, is responsible for a volume-regulated and hyperpolarization-activated inward rectifying Cl− current (ICl,ir). Membrane topology models (α-helices a-r) for ClC-3 and ClC-2 are modified from Dutzler et al. (2002). ICl,acid is a Cl− current regulated by extracellular pH and the molecular entity for ICl,acid is currently unknown. ICl,Ca is a Cl− current activated by increased intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i); Molecular candidates for ICl,Ca include CLCA1, a member of a Ca2+-sensitive Cl− channel family (CLCA), bestrophin-2, a member of the bestrophin gene family, and TMEM16, transmembrane protein 16. CFTR, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator, encodes Cl− channels activated by stimulation of cAMP–protein kinase A (PKA) pathway (ICl,PKA), protein kinase C (PKC) (ICl,PKC), or extracellular ATP through purinergic receptors (ICl,ATP). CFTR is composed of two membrane spanning domains (MSD1 and MSD2), two nucleotide binding domains (NBD1 and NBD2) and a regulatory subunit (R). P, phosphorylation sites for PKA and PKC; PP, serine–threonine protein phosphatases; Gi, heterodimeric inhibitory G protein; A1R, adenosine type 1 receptor; AC, adenylyl cyclase; H2R, histamine type II receptor; Gs, heterodimeric stimulatory G protein; β-AR, β-adrenergic receptor; P2R, purinergic type 2 receptor; proposed intracellular signalling pathway for purinergic activation of CFTR. VDAC, voltage-dependent anion channels (porin); mito, mitochondrion.

Previous in vitro experimental evidence has suggested that Cl− channels may be involved in the regulation of a large repertoire of cellular functions, including cellular excitability, intracellular organelle acidification, cell volume homeostasis, cell migration, proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis (Lang et al. 1998; Hume et al. 2000; Baumgarten & Clemo, 2003; Okada et al. 2006).

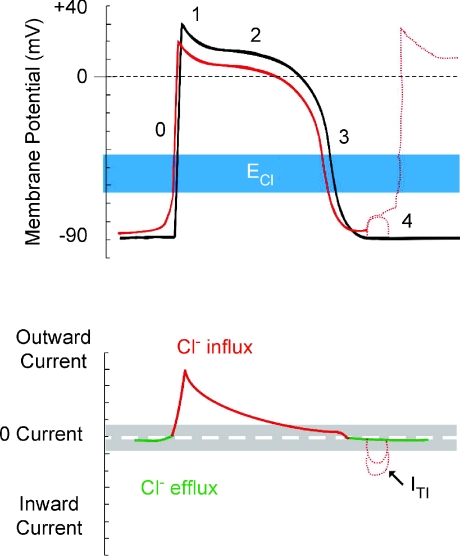

Early studies of intracellular Cl− activity (aiCl) in cardiac myocytes using ion-selective microelectrodes estimated an intracellular Cl− concentration ([Cl−]i) of 10 to 20 mmol l−1 under normal physiological conditions (Vaughan-Jones, 1979; Spitzer & Walker, 1980; Baumgarten & Fozzard, 1981; Caille et al. 1981). With an extracellular Cl− concentration ([Cl−]o) of 145 mmol l−1, therefore, the equilibrium potential for Cl− (ECl) is within a membrane potential range (usually −65 to −40 mV) that is more positive than the resting membrane potential and can be either negative or positive to the actual membrane potential during the normal cardiac cycle. Thus, compared with cationic channels, cardiac Cl− channels have the unique ability to generate both inward and outward currents and cause both depolarization and repolarization during the action potential. Therefore, activation of Cl− channels may produce significant effects on cardiac action potential characteristics (Fig. 2) and pacemaker activity (Fig. 3). The degree to which activation of Cl− currents depolarizes the resting membrane or accelerates the repolarization of action potential depends critically on the actual value of ECl and the magnitude of the Cl− conductance relative to the total membrane conductance. Under physiological conditions, for example, the activation of ClC-3 and CFTR Cl− channels in the heart will result in outwardly rectifying currents because the transmembrane Cl− gradient is asymmetrical. This will have more significant effects at positive potentials to accelerate repolarization and cause a shortening of the action potential duration (APD) compared with smaller depolarizing effects at negative potentials near the resting membrane potential (Fig. 2, top panel). Thus, activation of ClC-3 or CFTR channels will result in a shortening of Q–T interval (Fig. 2, bottom panel). The ability of Cl− current activation to depolarize cardiac cells is also opposed by the presence of a large background K+ conductance that normally controls the resting membrane potential. Both abbreviation of APD and depolarization of Em upon activation of Cl− channels may induce early afterdepolarization (EAD) and play a role in arrhythmogenesis under pathological conditions.

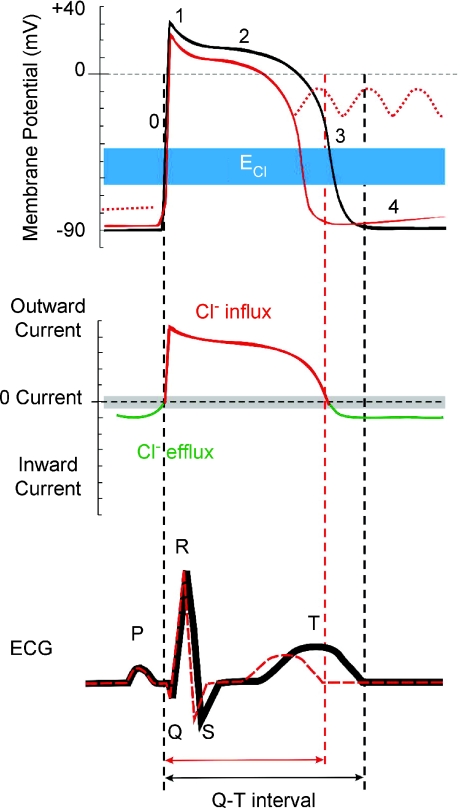

Figure 2. Modulation of cardiac electrical activity by activation of Cl− channels in heart.

Changes in action potentials (top), membrane currents (middle), and ECG (bottom) due to activation of CFTR or volume-regulated ClC-3 Cl− channels are depicted. Top panel, numbers illustrate conventional phases of a prototype ventricular action potential under control conditions (black) and after activation of ICl (red). Range of estimates for normal physiological values for Cl− equilibrium potential (ECl) is indicated in blue. Middle panel, range of zero-current values corresponding to ECl is shown in grey. Activation of CFTR or ClC-3 channels generates both inward (indicated by green) and outward (indicated by red) currents and cause both depolarization as well as repolarization during the action potential. Activation of ICl, therefore, induces larger membrane depolarization and induction of early afterdepolarizations (EAD) under conditions where resting K+ conductance is reduced (dotted red lines in top panel). Bottom panel, the letters (P, Q, R, S and T) indicate the conventional waves of ECG complex under control conditions (black) and after activation of ICl (red). Corresponding to the shortening of action potential in ventricular myocytes activation of ICl causes a shortening of Q–T interval. See text for details.

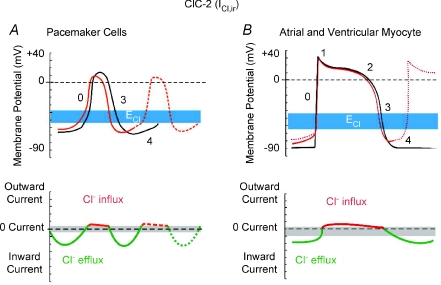

Figure 3. Modulation of cardiac electrical activity by activation of ClC-2 channels in cardiac pacemaker cells and myocytes.

Changes in action potentials (top panels) and membrane currents (bottom panels) of cardiac pacemaker cells (A), or atrial and ventricular myocytes (B), due to activation of ClC-2 channels are depicted. ICl.ir is activated by hyperpolarization, cell swelling, and acidosis. Top panels, numbers illustrate conventional phases of a prototype ventricular action potential under control conditions (black) and after activation of ICl (red). Range of estimates for normal physiological values for Cl− equilibrium potential (ECl) is indicated in blue. Bottom panels, range of zero-current values corresponding to ECl is shown in grey. A, activation of ICl.ir in pacemaker cells during hyperpolarization causes acceleration of phase 4 depolarization and automaticity, shortening of action potential duration, and decrease in cycle length and action potential amplitude (dashed red line in top panel). B, activation of ICl.ir in atrial and ventricular myocytes during hyperpolarization causes depolarization of resting membrane potential and induction of phase 4 autodepolarization and abnormal electrical impulse (trigger activity) and automaticity (dotted red line in top panel).

The understanding of Cl− channel function in cardiac physiology and pathophysiology, however, has been hampered by the concomitant expression of several types of Cl− channels in the same cardiac cell and by the lack of specific pharmacological tools to effectively separate the individual Cl− channels. For example, most studies that have examined the contribution of Cl− currents to the cardiac action potential and arrhythmias have relied on Cl− channel blockers and anion substitution experiments. The pharmacological specificity of many of these Cl− channel blockers can be problematic, and anion substitution, in addition to altering anion movement through channels, can have other unpredictable side effects on other transport proteins and signalling pathways (Frace et al. 1992; Nakajima et al. 1992).

The recent identification of molecular entities responsible for cardiac Cl− channels (Hume et al. 2000; Duan et al. 2005) has made it possible to combine gene-targeting techniques with electrophysiology, Molecular biology, and functional genomics and proteomics in the study of cardiac Cl− channels. Studies from transgenic and gene knockout mice have shown that Cl− channels may be important in arrhythmogenesis, myocardial hypertrophy, heart failure, and cardioprotection against ischaemia and reperfusion. Recent evidence has also demonstrated, however, that the study of physiological or pathophysiological phenotypes of cardiac Cl− channels may be complicated by the compensatory changes in the animals in response to the targeted genetic manipulation (Yamamoto-Mizuma et al. 2004b; Wright et al. 2008). To limit the effect of upregulation or developmental compensation on the phenotype of manipulated genes, tissue-specific conditional or inducible knockout or knockin animal models have been used as alternative approaches in the phenotypic studies of specific Cl− channel genes. In addition, recent evidence indicates that proteins do not act as single players but as part of functional complexes whose composition, subcellular localization and interaction orchestrate their biological role under different conditions. In addition, the integrated function of Cl− channels may involve multiple proteins of the Cl− channel subproteome and interactome. Similar phenotypes can be attained from alternative protein pathways within the cellular network. Therefore, the genotype–phenotype relationship of integrated Cl− channels and the molecular changes that give rise to particular phenotypes achieved by modifying the genotype (Cl− channel gene knockouts or knockins) should be studied systematically under the scope of genome, proteome and phenome. The phenomics approach, which characterizes phenotypes as a whole phenome, may provide more complete understanding of the functional role of each cardiac Cl− channel under normal and diseased conditions.

Several recent review articles have summarized the biophysical, pharmacological and molecular properties of the Cl− channels in the heart and the potential role of Cl− channels in cardiovascular function (Harvey, 1996; Hiraoka et al. 1998; Hume et al. 2000; Baumgarten & Clemo, 2003; Duan et al. 2005; Guan et al. 2006). In this review, I will highlight the major findings and recent advances in phenotypic studies of cardiac Cl− channels and discuss the possible uses of phenomics as an integrative approach to the systematic and meticulous understanding of Cl− channel function in the heart.

Phenotypic study of cardiac CFTR channels

CFTR in cardiac electrophysiology and arrythmogenesis

CFTR channels are closed under basal conditions and are activated only when the intracellular PKA- and PKC-dependent phosphorylation activity is increased (Duan et al. 1999b; Gadsby & Nairn, 1999; Hume et al. 2000). Telemetry ECG recordings revealed no significant difference in ECG parameters between CFTR−/− mice and their wild-type littermates (Xiang et al. unpublished observations), which is consistent with the low basal activity of CFTR channels in the heart. A major physiological role of activation of CFTR may be to prevent excessive APD prolongation and protect the heart against the development of early after-depolarization (EAD) and triggered activity caused by β-adrenergic stimulation of Ca2+ channels (Fig. 2). It is well-established that APD prolongation favours EADs by allowing recovery of inward currents and, conversely, shortening of APD makes it more difficult to induce EADs. EADs arising from phase 2 and 3 underlie focal triggered tachyarrhythmias and repolarization abnormalities, which contribute to cardiac sudden death. Therefore, activation of CFTR channels should protect against focal triggered arrhythmias. However, when background K+ conductance is reduced in the case of myocardial hypokalaemia, activation of CFTR channels will cause significant membrane depolarization and induce abnormal automaticity. These predicted effects of CFTR channel activation on APD and automaticity have been verified experimentally by manipulations of the Cl− gradient or the use of Cl− channel blockers (Harvey & Hume, 1990; Hiraoka et al. 1998). Histamine was found to activate CFTR channels in ventricular myocytes and induce oscillatory activity and abnormal impulses in the heart, although the contribution of CFTR channels to these arrhythmogenic activities has not been further explored. It has been shown that activation of CFTR channels contributes to hypoxia-induced shortening in APD (Ruiz et al. 1996). Activation of CFTR channels may accelerate the development of re-entry due to shortening of APD and refractoriness and a decrease in conduction velocity caused by a slight depolarization of diastolic potential leading to Na+ channel inactivation.

CFTR in myocardial hypertrophy and heart failure

Remodelling of CFTR channels has been observed in myocardial hypertrophy and heart failure. Using in situ mRNA hybridization in a combined pressure and volume overload model of heart failure in the rabbit, Wong et al. found that the normal epicardial to endocardial gradient of CFTR mRNA expression is reversed due to a significant decrease in epicardial expression of CFTR mRNA in the rabbit left ventricle (Wong et al. 2000). A post-translational change in CFTR expression could be responsible for this phenomenon (Davies et al. 2004). The loss of the normal transmural gradient of repolarising ion channels is likely to contribute to instability of repolarisation in the hypertrophied heart and hence increased risk of cardiac arrhythmias in patients with heart failure. A very recent study in human failing heart found that the expression of the mature CFTR protein decreased significantly to 52% of CFTR levels in non-failing controls (Solbach et al. 2008). Interestingly, it was reported recently that a paediatric patient who died of heart failure with significant myocardial lesion was retrospectively diagnosed as cystic fibrosis only after the histological examination of a liver biopsy (Collardeau-Frachon et al. 2007). The exact functional and clinical significance of the changes in CFTR expression during hypertrophy and heart failure is currently not clear and merits further study.

CFTR channels and cardioprotection against ischaemia/ reperfusion damage

We have previously found that targeted inactivation of the CFTR gene abolished the protective effects of ischaemic preconditioning on cardiac function and myocardium injury against sustained ischaemia in isolated mouse heart (Chen et al. 2004). Our preliminary in vivo studies using both wild-type and CFTR knockout mice also demonstrated that CFTR is an important mediator in both early and late ischaemic preconditioning in the heart (Ye et al. 2005). We also found that the CFTR channels may play a key role in the postconditioning induced cardioprotection in mouse heart (Xiang et al. 2008).

CFTR interactome and its versatile physiological functions

While CFTR is best characterized as a Cl− channel, considerable evidence in non-cardiac cells has demonstrated that CFTR is also a channel for other physiologically important anions such as the reduced form of glutathione (γ-glutamylcysteinylglycine; GSH) (Linsdell & Hanrahan, 1998; Gao et al. 1999; Kogan et al. 2003), ATP (Reisin et al. 1994; Sugita et al. 1998; Sabirov & Okada, 2005), and HCO3− (Minagawa et al. 2007). CFTR has been found to transport other molecules such as sphingosine-1-phosphate (Boujaoude et al. 2001) and to be involved in the release of cytokines (Vilela et al. 2006) and in the regulation of activities of many other ion channels and transporters such as epithelial Na+ channels (Kunzelmann et al. 2000, 2001) and Ca2+- and volume-activated Cl− channels (Kunzelmann et al. 2001). The integrated versatile functions and complex regulation of the CFTR channels may be concerted by a number of proteins in the CFTR interactome, which may include the chaperones that facilitate the processing and trafficking of CFTR protein, the proteins that control CFTR activity through signalling mechanisms, and other proteins such as ion channels and transporters that CFTR regulates (Kunzelmann et al. 2000, 2001; Naren & Kirk, 2000; Guggino & Banks-Schlegel, 2004; Guggino & Stanton, 2006; Wang et al. 2006; Skach, 2006).

Phenotypic study of cardiac ClC-2 channels: ClC-2 and pacemaker activity

ClC-2 channels are activated by hyperpolarization, cell swelling, and acidosis and have an inwardly rectifying I–V relationship (Duan et al. 2000). During the cardiac action potential, therefore, the ClC-2 channel will conduct a mainly inward current as a result of Cl− efflux at negative membrane potentials and cause a depolarization of the resting membrane potential of cardiac cells. At membrane potentials more positive than ECl, ClC-2 may conduct a small outward current as a result of Cl− influx and may accelerate repolarization of the action potential. It is also possible that, in a manner analogous to the role and tissue distribution pattern of the cationic pacemaker channels (If), the hyperpolarization-activated inward rectifying Cl− current (ICl,ir) through ClC-2 channels normally plays a much more prominent role in the SA or AV nodal regions of the heart (Fig. 3). ICl,ir under basal or isotonic conditions is small, but can be further activated by hypotonic cell swelling (Duan et al. 2000) and acidosis (Komukai et al. 2002a,b). The volume sensitivity of the channel also suggests its role in cell volume regulation. The sensitivity of ClC-2 to [H+]o and cell volume may be of pathological importance during hypoxia- or ischaemia-induced acidosis or cell swelling. Therefore, it may be possible that the significance of ICl,ir in the heart becomes more prominent under some pathological conditions (ischaemia or hypoxia) (Wright & Rees, 1997). As a matter of fact, ischaemia and acidosis have consistently been shown to depolarize the resting membrane potential of cardiac myocytes, increase automaticity and cause lethal arrhythmias, although the mechanism has remained obscure (Hiraoka et al. 1998; Carmeliet, 1999). It is reasonable to suggest that an increase in ClC-2 conductance could be responsible for these phenomena and be pro-arrhythmic. Drugs targeting ClC-2 channels could be anti-arrhythmic. Therefore, the ClC-2 channels could have important clinical significance for such cardiac diseases as arrhythmias, ischaemia and reperfusion, and congestive heart failure. Activation of ClC-2 current should mainly cause a depolarization of the resting membrane potential and it is suggested that the acidosis-induced increase in ICl,ir might underlie the depolarization of the resting membrane potential during acidosis or hypoxia (Komukai et al. 2002a,b). Preliminary telemetry electrocardiograph studies in conscious ClC-2 knockout (Clcn2−/−) mice revealed an increased incidence of atrial-ventricular block and a decreased chronotropic response to acute exercise stress when compared to their age-matched Clcn2+/+ and Clcn2+/− littermates. Targeted inactivation of ClC-2 does not alter intrinsic heart rate but prevents the positive chronotropic effect of acute exercise stress through a sympathetic regulation of ClC-2 channels (Huang et al. 2008).

Phenotypic study of cardiac ClC-3 channels

Functional role of VRCCs and ClC-3 in electrophysiology and arrythmogenesis

The current through the volume-regulated Cl− channels (VRCCs) under basal or isotonic conditions is small (Duan et al. 1992, 1997a; Sorota, 1992), but can be further activated by stretching of the cell membrane by inflation (Du & Sorota, 1997) or direct mechanical stretch of membrane β1-integrin (Browe & Baumgarten, 2003) and/or cell swelling induced by exposure to hypoosmotic solutions (Sorota, 1992; Du & Sorota, 1997; Duan et al. 1997b, 1999a). Activation of VRCCs is expected to produce depolarization of the resting membrane potential and more significant APD shortening than activation of CFTR channels (Fig. 2) because of its stronger outwardly rectifying property (Duan & Nattel, 1994; Duan et al. 1997a; Du & Sorota, 1997; Vandenberg et al. 1997). Because myocardial cells swell during hypoxia and ischaemia, and the washout of hyperosmotic extracellular fluid after reperfusion induces further cell swelling, activation of VRCCs may also contribute to hypoxia, ischaemia and reperfusion induced shortening of APD and arrhythmias (Du & Sorota, 1997; Vandenberg et al. 1997; Baumgarten & Clemo, 2003). Shortening of APD and, therefore, the effective refractory period reduces the length of the conducting pathway needed to sustain re-entry (wavelength). In principle, this favours the development of atrial or ventricular fibrillation, which depends on the presence of multiple re-entrant circuits or rotating spiral waves. ICl.swell also may slow or enhance the conduction of early extrasystoles, depending on the timing. In guinea-pig heart, hypo-osmotic solution shortened APDs and increased APD gradients between right and left ventricles. In ventricular fibrillation (VF) induced by burst stimulation, switching to hypo-osmotic solution increased VF frequencies, transforming complex fast Fourier transformation spectra to a single dominant high frequency on the left but not the right ventricle (Choi et al. 2006). Perfusion with the VRCC blocker indanyloxyacetic acid-94 reversed organized VF to complex VF with lower frequencies, indicating that VRCC underlies the changes in VF dynamics. Consistent with this interpretation, ClC-3 channel protein expression is 27% greater on left than right ventricles, and computer simulations showed that insertion of ICl,vol transformed complex VF to a stable spiral. Therefore, activation of ICl,vol has a major impact on VF dynamics by transforming random multiple wavelets to a highly organized VF with a single dominant frequency.

It has been shown that mechanical stretching or dilatation of the atrial myocardium is able to cause arrhythmias. Since ICl.swell was also found in sino-atrial (S-A) nodal cells, VRCCs may serve as a mediator of mechanotransduction and play a significant role in the pacemaker function if they act as the stretch activated channels in these cells (Hagiwara et al. 1992; Baumgarten & Clemo, 2003). Baumgarten's laboratory has recently demonstrated that ICl,swell in ventricular myocytes can be directly activated by mechanical stretch through selectively stretching β1-integrins with mAb-coated magnetic beads (Baumgarten & Clemo, 2003; Browe & Baumgarten, 2003, 2004). Although it has been suggested that stretch and swelling activate the same anion channel in some non-cardiac cells, further study is needed to determine whether this is true in cardiac myocytes.

In the case of myocardial hypertrophy and heart failure, ionic remodelling is one of the major features of pathophysiological changes (Tomaselli & Marban, 1999). It has been found that the current densities and molecular expression of several major repolarizing K+ channels (such as Kv4x) are significantly reduced, which may be responsible for the prolongation of APD and development of EAD (Tomaselli & Marban, 1999). However, under these conditions, ICl,vol is constitutively active (Clemo et al. 1999b). The persistent activation of ICl,vol may limit the APD prolongation and make it more difficult to elicit EAD. Indeed, in myocytes from hearts in failure, blocking ICl,vol by tamoxifen significantly prolonged APD and decreased the depolarizing current required to elicit EAD by about 50%. Interestingly hyperosmotic cell shrinkage, which also inhibits ICl,vol, was almost equivalent to the effect of tamoxifen on APD and EAD in these myocytes (Baumgarten & Clemo, 2003). Therefore, the consequences of activation of ICl,vol are very complex. It may be detrimental, beneficial, or both simultaneously in different parts of the heart, depending on environmental influences.

ICl,swell and ClC-3 in IPC

It has been reported that the block of ICl,swell in rabbit cardiac myocytes inhibits preconditioning by brief ischaemia, hypoosmotic stress (Diaz et al. 1999, 2001) and adenosine receptor agonists (Batthish et al. 2002). These studies were solely based on the use of several Cl− channel blockers, such as anthracene-9-carboxylic acid (9-AC) and 4-acetamide-4′-isothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (SITS). As mentioned above, these pharmacological tools lack specificity to a particular Cl− channel in the heart and may also act on other ion channels or transporters. Therefore it has been very difficult to confirm the causal role of ICl,swell in IPC (Heusch et al. 2000). To specifically test whether the VRCCs are indeed involved in IPC, we have recently established in vitro and in vivo IPC models in ClCn3−/− mice. Our preliminary results indicate that targeted inactivation of ClC-3 gene prevented protective effects of late IPC but not of early IPC, suggesting that ICl,swell may contribute differently to early and late IPC (Bozeat et al. 2005, 2006). The underlying mechanisms for these differential effects are currently unknown. Recent reports, however, suggest that ICl,swell and ClC-3 might play an important role in apoptosis (Guan et al. 2006) and inflammation (Volk et al. 2008). Cl− channel blockers DIDS and NPPB were as potent as a broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor in preventing apoptosis and elevation of caspase-3 activity and improved cardiac contractile function after ischaemia and in vivo reperfusion (Mizoguchi et al. 2002). Transgenic mice overexpressing Bcl-2 in the heart had significantly smaller infarct size and reduced apoptosis of myocytes after ischaemia and reperfusion (Chen et al. 2001). It has been shown that Bcl-2 induces up-regulation of ICl,vol by enhancing ClC-3 expression in human prostate cancer epithelial cells (Lemonnier et al. 2004). Cell shrinkage is an integral part of apoptosis, suggesting that ICl,vol and ClC-3 might be intimately linked to apoptotic events through regulation of cell volume homeostasis (Wei et al. 2004; Lemonnier et al. 2004; Guan et al. 2006).

ICl.swell and ClC-3 in myocardial hypertrophy and heart failure

ICl.swell is persistently activated in ventricular myocytes from a canine pacing-induced dilated cardiomyopathy model (Clemo et al. 1999b). Using the perforated patch-clamp technique, Clemo et al. found that, even in isotonic solutions, a large 9-AC-sensitive, outwardly rectifying Cl− current was recorded in failing cardiac myocytes but not in normal cardiac myocytes. Graded hypotonic cell swelling (90–60% hypotonic) failed to activate additional current while graded hypertonic cell shrinkage caused an inhibition of the ‘basal’ Cl− current in failing myocytes. Moreover, the maximum current density of the ICl.swell in failing myocytes was about 40% greater than that in osmotically swollen normal myocytes. Constitutive activation of ICl.swell is also observed in several other animal models of heart failure, such as a rabbit aortic regurgitation model of dilated cardiomyopathy (Clemo & Baumgarten, 1998; Clemo et al. 1999a), a dog model of heart failure caused by myocardial infarction(Clemo et al. 1999b), and a mouse model of myocardial hypertrophy by aorta binding (Duan et al. 2004). In human atrial myocytes obtained from patients with right atrial enlargement and/or elevated left ventricular end-diastolic pressure, a tamoxifen sensitive ICl.swell was also found to be persistently activated (Patel et al. 2003). Therefore, it is possible that persistent activation of ICl.swell is a common response of cardiac myocytes to hypertrophy or heart failure-induced remodelling.

The mechanism for persistent activation of ICl.swell in hypertrophied or failing cardiac myocytes is still not clear. Perhaps the increase in cell volume caused by hypertrophy and the stretch of cell membrane caused by dilatation are both involved in the activation of ICl.swell. Alternatively, the persistent activation of ICl.swell may be caused by signalling cascades activated during hypertrophy independent of changes in cell length and volume, or both. ICl,swell could be activated by direct stretch of β1-integrin through focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and/or Src (Browe & Baumgarten, 2003). Mechanical stretch of myocytes also releases angiotensin II (AngII), which binds to AT1 receptors (AT1R) and stimulates FAK and Src in an autocrine–paracrine loop. A recent study by Browe and Baumgarten suggests that the stretch of β1-integrin in cardiac myocytes activates ICl.swell by activating AT1R and NADPH oxidase and, thereby, producing reactive oxygen species (ROS). In addition, NADPH oxidase may be intimately coupled to the channel responsible for ICl.swell, providing a second regulatory pathway for this channel through membrane stretch or oxidative stress (Browe & Baumgarten, 2004). This finding is very important for further understanding of the mechanism for hypertrophy activation of ICl.swell and ClC-3 channels and their relationship to hypertrophy and heart failure as it is very well known that Ang II plays a crucial role in myocardial hypertrophy and heart failure (De Mello, 2004). Interestingly, Miller and colleagues recently found that Cl− channel inhibitors and knockout of ClC-3 abolish cytokine-induced generation of ROS in endosomes and ROS-dependent NFκB activation in vascular smooth muscle cells (Miller et al. 2007), suggesting a potential close interaction between NADPH oxidase and ClC-3. In human corneal keratocytes and human fetal lung fibroblasts ClC-3 knockdown by a short hairpin RNA (shRNA) significantly decreased VRCC and lysophosphatidic acid (LPA)-activated Cl− current (ICl,LPA) in the presence of transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) compared with controls, whereas ClC-3 overexpression resulted in increased ICl,LPA in the absence of TGF-β1 (Yin et al. 2008). ClC-3 knockdown also resulted in a reduction of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) protein levels in the presence of TGF-β1, whereas ClC-3 overexpression increased α-SMA protein expression in the absence of TGF-β1. In addition, keratocytes transfected with ClC-3 shRNA had a significantly blunted regulatory volume decrease response following hyposmotic stimulation compared with controls. These data not only confirm that ClC-3 is important in VRCC function and cell volume regulation, but also provide new insight into the mechanism for the ClC-3-mediated fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition (Yin et al. 2008).

The functional and clinical significance of VRCCs in the hypertrophied and dilated heart are currently unknown. Using a mouse aortic binding model of myocardial hypertrophy, we have found that globally targeted disruption of ClC-3 gene (ClCn3−/−) accelerated the development of myocardial hypertrophy and the discompensatory process (Fig. 4), suggesting that activation of ICl,vol might be important in the adaptive remodelling of the heart during pressure overload (Liu et al. 2003). Interestingly, heart failure was found to be accompanied by a reduced ICl,vol density in rabbit cardiac myocytes (van Borren et al. 2002).

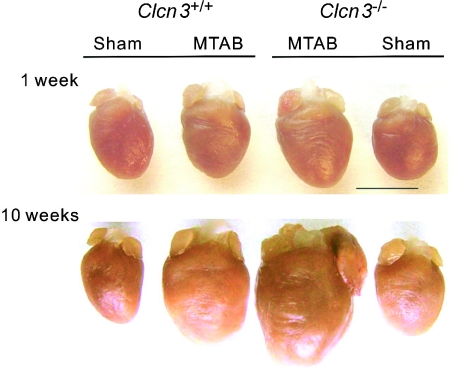

Figure 4. Comparison of pressure overload-induced remodelling of wild-type and Clcn3−/− mouse hearts.

Hearts from age-matched wild-type (WT, Clcn3+/+) and Clcn3−/− mice were excised 1 week (top panel) or 10 weeks (bottom panel) after minimally invasive transverse aorta binding (MTAB) or sham operation are shown. Hearts were cleaned of blood and connective tissues and then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Bar = 5 mm. Compared to WT mice disruption of ClC-3 gene significantly changed the remodelling process after MTAB. Both left ventricle and atrium were extremely enlarged after 10 weeks of MTAB.

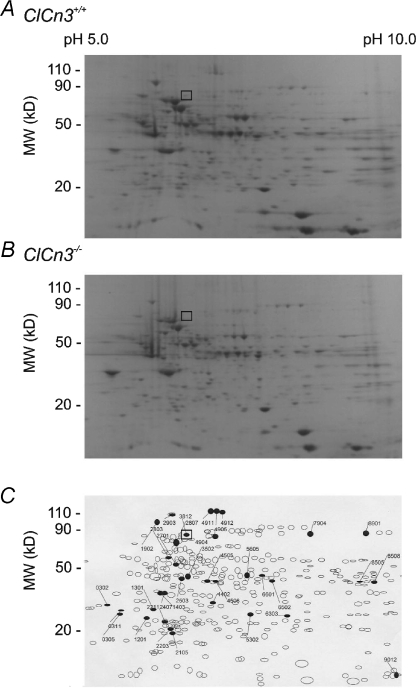

In order to understand the molecular changes in cardiac function that accompany the knockout of the Clcn3 gene, we examined gene and protein expression profiles from ClCn3−/− and ClCn3+/+ mouse heart. Overall 150 genes and 35 proteins are expressed differentially in the heart of the ClCn3−/− mouse model compared to those of control ClCn3+/+ mice (Yamamoto-Mizuma et al. 2004b). Expression of ClC-2 and ClC-1 channels is increased 5-fold and 4-fold, respectively, while the expression of some cytoskeleton proteins and PKCδ is decreased by more than 2-fold. To further test the possibility that targeted inactivation of the Clcn3 gene using a conventional murine global knockout approach might result in compensatory changes in expression of other membrane proteins in cells from Clcn3−/− mice, cardiac membrane proteins were isolated from Clcn3+/+ and Clcn3−/− mice and analysed using two dimensional (2-D) polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Fig. 5). In atrial cell membrane extracts 753 distinct membrane proteins were initially identified, and up to 104 proteins appeared to exhibit altered expression levels in cells from Clcn3−/− mice, compared to atrial cells from Clcn3+/+ mice. In order to more reliably quantify actual changes in protein expression and minimize spurious results that might arise due to expected small variations in protein spot densities that normally occur from gel to gel, we established a minimal detection criterion of a 2-fold change in spot density. Using this criterion, comparisons of 2-D gels from membrane extracts isolated from Clcn3+/+ andClcn3−/− mice (Fig. 5) consistently revealed significant changes in the expression of at least 35 distinct membrane proteins (6 missing proteins, 2 new proteins, 9 upregulated proteins, 15 downregulated proteins, and 2 translocated proteins) from hearts of Clcn3−/− mice compared to Clcn3+/+ mice. One of the six missing proteins was identified as ClC-3 by Western blot analysis of the 2-D gels. The location (molecular mass = 85 kDa and pI= 6.9) of the ClC-3 protein spot (no. 3812) in the 2-D gels from Clcn3+/+ mice (□ in Fig. 5) is consistent with the predicted molecular mass of 84 kDa and pI of 6.91 for ClC-3. Obviously the compensatory changes in the animals in response to the targeted genetic manipulation are very complicated and the observed physiological or pathophysiological phenotypes of the Clcn3−/− mice cannot simply be attributed to changes in a single ClC-3 protein. Alternatively, tissue-specific conditional or inducible knockout or knockin animal models may be more valuable in the phenotypic studies of specific Cl− channels by limiting the effect of compensation on the phenotype. Our preliminary studies on the conditional heart-specific ClC-3 knockout and knockin mice and inducible heart-specific ClC-3 knockout mice consistently support the crucial functional role of ClC-3 channels in the adaptive remodelling of the heart against pressure overload (Xiong et al. 2008).

Figure 5. Comparative two-dimensional electrophoresis analysis of protein expression patterns in membranes of cardiac cells from Clcn3+/+ and Clcn3−/− mice.

A, representative 2-D gel depicts Coomassie-stained proteins from wild-type (Clcn3+/+) mouse heart. B, representative 2-D gel depicts Coomassie-stained proteins from Clcn3−/− mouse heart. C, spot sets created from images of 2-D gels of both wild-type and Clcn3−/− mouse heart run under the same conditions as the gels in A and B and compared using Bio-Rad PDQuest version 7.1.1 software. Three gels were run for each mouse heart type; two hearts were pooled to provide proteins for each gel. The filled symbols indicate changes in protein patterns in Clcn3−/− compared to wild-type. A total of 35 proteins consistently changed (minimum criteria: > 2-fold change) in membranes from Clcn3−/− mouse heart in all 3 experiments (6 missing proteins, 2 new proteins, 9 up-regulated proteins, 15 down-regulated proteins, and 2 translocated proteins). The open squares (□) in A, B and C indicate the location (molecular mass 85 kDa and pI 6.9) of the ClC-3 protein spot (No. 3812) in the 2-D gels, which was independently confirmed by Western blotting using a specific anti-ClC-3 C670−687 antibody. (From Yamamoto-Mizuma et al. 2004b).

Phenotypic study of Ca2+-activated Cl− channels in heart

Ca2+-activated chloride channels (CACCs) are widely distributed in cardiac tissues and play important roles in the regulation of cardiac excitability. However, the molecular identity of this channel in the heart remains to be determined. CLCA-1 and bestrophins (Hartzell et al. 2005) were initially proposed as candidates for CACCs in cardiac tissues (O’Driscoll et al. 2008a). It has been demonstrated that at least three members of the murine bestrophin family, mBest1, mBest2 and mBest3, are expressed in mouse heart. Whole-cell patch clamp experiments with HEK cells transfected with cardiac mBest1 and mBest3 both elicited a calcium sensitive, time-independent Cl− current, suggesting mBest1 and mBest3 may function as pore-forming Cl− channels that are activated by physiological levels of calcium (O’Driscoll et al. 2008a,b). Very recently, independent studies from three laboratories have identified a new gene, TMEM16 (or Ano1), as a candidate for CACCs (Caputo et al. 2008; Schroeder et al. 2008; Yang et al. 2008). The hTMEM16A mRNA is present in multiple human tissues, including heart, lung, placenta, liver, skeletal muscle and small intestine (Huang et al. 2006). Whether TMEM16 forms the functional endogenous CACCs and how TMEME16 interacts with and the bestrophins in native cardiac myocytes remain to be explored.

Ca2+-activated Cl− channel and cardiac electrophysiology and arrhythmogenesis

Even though ICl,Ca is also expected to be outwardly rectifying under physiological conditions the activation of ICl,Ca will have considerably different effects on cardiac action potentials and resting membrane potential (Fig. 6) from those of CFTR and ClC-3 channels (Fig. 2). This is because the kinetic behaviour of ICl,Ca is significantly determined by the time course of the [Ca2+]i transient (Zygmunt & Gibbons, 1991). Normally, ICl,Ca will have insignificant effects on the diastolic membrane potential, as resting [Ca2+]i is low. When [Ca2+]i is substantially increased above the physiological resting level, however, ICl,Ca carries a significant amount of transient outward current. ICl,Ca will activate early during the action potential in response to an increase in [Ca2+]i associated with Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR), The time course of decline of the [Ca2+]i transient will determine the extent to which ICl,Ca contributes to early repolarization during phase 1. In the rabbit left ventricle, ICl,Ca contributes to APD shortening in subendocardial myocytes but not in subepicardial myocytes. These differences in functional expression of ICl,Ca may reduce the electrical heterogeneity in the left ventricle (Verkerk et al. 2004). In Ca2+-overloaded cardiac preparations, ICl,Ca can contribute to the arrhythmogenic transient inward current (ITI, see Fig. 6) (Zygmunt, 1994). ITI produces delayed afterdepolarization (DAD) (January & Fozzard, 1988) and induces triggered activity, which is an important mechanism for abnormal impulse formation. In sheep Purkinje and ventricular myocytes, activation of ICl,Ca was found to induce DAD and plateau transient repolarization (Verkerk et al. 2000). Therefore, blockade of ICl,Ca may be potentially antiarrhythmogenic by reducing DAD amplitude and triggered activity based on DAD. However, the role of ICl,Ca in phase 1 repolarization and the generation of EAD and DAD of either normal or failing human heart seem very limited (Verkerk et al. 2003). Therefore, the clinical relevance of ICl,Ca blockers remains to be determined.

Figure 6. Modulation of cardiac electrical activity by activation of Ca2+-activated Cl− channels in heart.

Changes in action potentials (top) and membrane currents (bottom) due to activation of Ca2+-activated Cl− channels are depicted. Top panel, numbers illustrate conventional phases of a prototype ventricular action potential under control conditions (black) and after activation of ICl (red). Range of estimates for normal physiological values for ECl is indicated in blue. Bottom panel, range of zero-current values corresponding to ECl is shown in grey. Activation of ICl.Ca during [Ca2+]i overload results in oscillatory transient inward current (ITI) and induction of delayed afterdepolarization (DAD) (dotted red lines).

ICl,Ca in myocardial hypertrophy and heart failure

The critical role of Ca2+ in cardiac development, function and disease is undisputable. Despite the heterogeneous aetiology and overt manifestations of heart failure, abnormalities in Ca2+ handling are prominent, and alterations in Ca2+ homeostasis are a hallmark of myocardial hypertrophy and heart failure (Houser et al. 2000). Ca2+ transients in failing cardiac myocytes, for example, are characterized by diminished amplitude, elevated diastolic Ca2+ levels, and prolonged decay of the Ca2+ transients. In non-cardiac cells, ICl,Ca could be an important mediator of apoptosis (Elble & Pauli, 2001). But, information on the possible involvement of ICl,Ca in heart failure is currently very limited. It is reported that ICl,Ca may play little, if any, role in the electrical remodelling of human end-stage failing heart (Verkerk et al. 2001, 2003).

Conclusions and future directions

Recent efforts have provided strong evidence that Cl− channels may play an important role in cardiac diseases, including arrhythmias, myocardial ischaemia, hypertrophy and heart failure. Although global knockout mice are invaluable experimental models and functional genomics remains a powerful approach to understanding the function of cardiac Cl− channels, much information has been also gained in recent years using different transgenic mouse models. One common finding among different models has been compensatory changes in the animals in response to the targeted genetic manipulation (Yamamoto-Mizuma et al. 2004b; Guggino, 2009). These compensatory changes most likely exert beneficial effects for the animal's survival but may introduce complications in understanding the phenotypes of the animals. Even though the loss of the product of the targeted gene can be verified, the upregulation of other genes in the vicinity of the targeting can occur (Moore et al. 1999) and may readily escape detection. Such upregulation could have an important effect on the observed phenotype. A knockout may not always be a knockout such as when the targeted gene is widely or ubiquitously expressed, when alternative splicing variants of the gene exist (Jentsch et al. 2002), and when functional channels are actually heteromultimeric and the structure might be associated with modulatory subunits (Estevez et al. 2001). Accessory proteins may be involved in the determination of the stability of the channel complex in the membrane and in the modulation of biophysical, pharmacological and regulatory properties of the channel. A Cl− channel may function as a multi-protein complex or functional module, which may be composed of a pore forming subunit for ion transportation, auxiliary subunits for modulating pore gating, and proteins as second messengers tightly coupled to channel function. These proteins might be intimately linked to certain physiological functions and belong to the same subproteome. Manipulation of one gene in the subproteome may cause changes in other proteins of the same subproteome. Therefore, the functional consequences of disrupting the specific gene are very difficult to predict unless the changes in the entire subproteome are examined. Therefore, caution should be taken when conventional global gene knockout animals are used in phenotypic studies. Alternatively, tissue-specific conditional or inducible knockout or knockin animal models may be more valuable in the phenotypic studies of specific Cl− channels by limiting the effect of compensation on the phenotype. On the other hand, similar phenotypes can be attained from alternative protein pathways involving different gene products and many phenotypic changes may actually be a result of posttranslational modifications such as protein phosphorylation or dephosphorylation. Therefore, it is clear that conventional functional genomics may provide only limited information on the functional module of multi-protein complexes. We are now facing the challenge of a major paradigm shift in the study of integrated Cl− channel functions. Further investigations of the cellular and molecular mechanisms by which the cardiac Cl− channel proteins function to impart physiological or pathophysiological phenotypes may require a phenomic approach to characterize the phenotypes of cardiac Cl− channels on a genome- and proteome-wide scale in the context of health and disease.

Acknowledgments

The research in the Laboratory of Functional Genomics and Proteomics, Center of Biomedical Research Excellence and the Department of Pharmacology, University of Nevada, School of Medicine is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01-HL63914), National Center of Research Resources (NCRR, P20RR15581), American Diabetes Association Innovation Award, and the National Basic Research Program of China (no. 2009CB521903).

References

- Bahinski A, Nairn AC, Greengard P, Gadsby DC. Chloride conductance regulated by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase in cardiac myocytes. Nature. 1989;340:718–721. doi: 10.1038/340718a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker MA, Lane DJ, Ly JD, De Pinto V, Lawen A. VDAC1 is a transplasma membrane NADH-ferricyanide reductase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:4811–4819. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311020200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batthish M, Diaz RJ, Zeng HP, Backx PH, Wilson GJ. Pharmacological preconditioning in rabbit myocardium is blocked by chloride channel inhibition. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;55:660–671. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00454-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgarten CM, Clemo HF. Swelling-activated chloride channels in cardiac physiology and pathophysiology. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2003;82:25–42. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(03)00003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgarten CM, Fozzard HA. Intracellular chloride activity in mammalian ventricular muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1981;241:C121–C129. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1981.241.3.C121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boujaoude LC, Bradshaw-Wilder C, Mao C, Cohn J, Ogretmen B, Hannun YA, Obeid LM. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator regulates uptake of sphingoid base phosphates and lysophosphatidic acid: modulation of cellular activity of sphingosine 1-phosphate. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:35258–35264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105442200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozeat N, Dwyer L, Ye L, Yao T, Duan D. The role of ClC-3 chloride channels in early and late ischemic preconditioning in mouse heart. FASEB J. 2005;19:A694–A695. [Google Scholar]

- Bozeat N, Dwyer L, Ye L, Yao TY, Hatton WJ, Duan D. VSOACs play an important cardioprotective role in late ischemic preconditioning in mouse heart. Circulation. 2006;114:272–273. 1425. [Google Scholar]

- Britton FC, Ohya S, Horowitz B, Greenwood IA. Comparison of the properties of CLCA1 generated currents and ICl(Ca) in murine portal vein smooth muscle cells. J Physiol. 2002;539:107–117. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browe DM, Baumgarten CM. Stretch of β1 integrin activates an outwardly rectifying chloride current via FAK and Src in rabbit ventricular myocytes. J Gen Physiol. 2003;122:689–702. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browe DM, Baumgarten CM. Angiotensin II (AT1) receptors and NADPH oxidase regulate Cl− current elicited by β1 integrin stretch in rabbit ventricular myocytes. J Gen Physiol. 2004;124:273–287. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caille JP, Ruiz-Ceretti E, Schanne OF. Intracellular chloride activity in rabbit papillary muscle: effect of ouabain. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1981;240:C183–C188. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1981.240.5.C183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caputo A, Caci E, Ferrera L, Pedemonte N, Barsanti C, Sondo E, Pfeffer U, Ravazzolo R, Zegarra-Moran O, Galietta LJ. TMEM16A, a membrane protein associated with calcium-dependent chloride channel activity. Science. 2008;322:590–594. doi: 10.1126/science.1163518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet E. Cardiac ionic currents and acute ischemia: from channels to arrhythmias. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:917–1017. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.3.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Liu LL, Ye LL, McGuckin C, Tamowski S, Scowen P, Tian H, Murray K, Hatton WJ, Duan D. Targeted inactivation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channel gene prevents ischemic preconditioning in isolated mouse heart. Circulation. 2004;110:700–704. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000138110.84758.BB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Chua CC, Ho YS, Hamdy RC, Chua BH. Overexpression of Bcl-2 attenuates apoptosis and protects against myocardial I/R injury in transgenic mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H2313–H2320. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.5.H2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi BR, Hatton WJ, Hume JR, Liu T, Salama G. Low osmolarity transforms ventricular fibrillation from complex to highly organized, with a dominant high-frequency source. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3:1210–1220. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemo HF, Baumgarten CM. Protein kinase C activation blocks ICl(swell) and causes myocyte swelling in a rabbit congestive heart failure model. Circulation. 1998;98:I–695. [Google Scholar]

- Clemo HF, Danetz JS, Baumgarten CM. Does ClC-3 modulate cardiac cell volume? Biophys J. 1999a;76:A203. [Google Scholar]

- Clemo HF, Stambler BS, Baumgarten CM. Swelling-activated chloride current is persistently activated in ventricular myocytes from dogs with tachycardia-induced congestive heart failure. Circ Res. 1999b;84:157–165. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.2.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collardeau-Frachon S, Bouvier R, Le GC, Rivet C, Cabet F, Bellon G, Lachaux A, Scoazec JY. Unexpected diagnosis of cystic fibrosis at liver biopsy: a report of four pediatric cases. Virchows Arch. 2007;451:57–64. doi: 10.1007/s00428-007-0434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier ML, Hume JR. Unitary chloride channels activated by protein kinase C in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 1995;76:317–324. doi: 10.1161/01.res.76.2.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier ML, Levesque PC, Kenyon JL, Hume JR. Unitary Cl− channels activated by cytoplasmic Ca2+ in canine ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 1996;78:936–944. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.5.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies WL, Vandenberg JI, Sayeed RA, Trezise AE. Post-transcriptional regulation of the cystic fibrosis gene in cardiac development and hypertrophy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;319:410–418. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Mello WC. Heart failure: how important is cellular sequestration? The role of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004;37:431–438. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz RJ, Batthish M, Backx PH, Wilson GJ. Chloride channel inhibition does block the protection of ischemic preconditioning in myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:1887–1889. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz RJ, Losito VA, Mao GD, Ford MK, Backx PH, Wilson GJ. Chloride channel inhibition blocks the protection of ischemic preconditioning and hypo-osmotic stress in rabbit ventricular myocardium. Circ Res. 1999;84:763–775. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.7.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du XY, Sorota S. Cardiac swelling-induced chloride current depolarizes canine atrial myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1997;272:H1904–H1916. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.4.H1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan D, Cowley S, Horowitz B, Hume JR. A serine residue in ClC-3 links phosphorylation-dephosphorylation to chloride channel regulation by cell volume. J Gen Physiol. 1999a;113:57–70. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.1.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan D, Fermini B, Nattel S. Sustained outward current observed after Ito1 inactivation in rabbit atrial myocytes is a novel Cl− current. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1992;263:H1967–H1971. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.6.H1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan D, Fermini B, Nattel S. α-Adrenergic control of volume-regulated Cl− currents in rabbit atrial myocytes. Characterization of a novel ionic regulatory mechanism. Circ Res. 1995;77:379–393. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.2.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan D, Hume JR, Nattel S. Evidence that outwardly rectifying Cl− channels underlie volume-regulated Cl− currents in heart. Circ Res. 1997a;80:103–113. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan D, Liu L, Wang GL, Ye L, Tian H, Yao Y, Chen A, Duan M, Hatton W. Cell volume-regulated ion channels and ionic remodeling in hypertrophied mouse heart. J Cardiac Failure. 2004;10:S72. [Google Scholar]

- Duan D, Nattel S. Properties of single outwardly rectifying Cl− channels in heart. Circ Res. 1994;75:789–795. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.4.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan D, Winter C, Cowley S, Hume JR, Horowitz B. Molecular identification of a volume-regulated chloride channel. Nature. 1997b;390:417–421. doi: 10.1038/37151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan D, Ye L, Britton F, Horowitz B, Hume JR. A novel anionic inward rectifier in native cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2000;86:E63–E71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan D, Ye L, Britton F, Miller LJ, Yamazaki J, Horowitz B, Hume JR. Purinoceptor-coupled Cl− channels in mouse heart: a novel, alternative pathway for CFTR regulation. J Physiol. 1999b;521:43–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00043.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan D, Zhong J, Hermoso M, Satterwhite CM, Rossow CF, Hatton WJ, Yamboliev I, Horowitz B, Hume JR. Functional inhibition of native volume-sensitive outwardly rectifying anion channels in muscle cells and Xenopus oocytes by anti-ClC-3 antibody. J Physiol. 2001;531:437–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0437i.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan DY, Liu LL, Bozeat N, Huang ZM, Xiang SY, Wang GL, Ye L, Hume JR. Functional role of anion channels in cardiac diseases. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2005;26:265–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2005.00061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutzler R, Campbell EB, Cadene M, Chait BT, MacKinnon R. X-ray structure of a ClC chloride channel at 3.0 A reveals the molecular basis of anion selectivity. Nature. 2002;415:287–294. doi: 10.1038/415287a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elble RC, Pauli BU. Tumor suppression by a proapoptotic calcium-activated chloride channel in mammary epithelium. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:40510–40517. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104821200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estevez R, Boettger T, Stein V, Birkenhager R, Otto E, Hildebrandt F, Jentsch TJ. Barttin is a Cl− channel β-subunit crucial for renal Cl− reabsorption and inner ear K+ secretion. Nature. 2001;414:558–561. doi: 10.1038/35107099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frace AM, Maruoka F, Noma A. Control of the hyperpolarization-activated cation current by external anions in rabbit sino-atrial node cells. J Physiol. 1992;453:307–318. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadsby DC, Nairn AC. Control of CFTR channel gating by phosphorylation and nucleotide hydrolysis. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:S77–S107. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.1.S77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao L, Kim KJ, Yankaskas JR, Forman HJ. Abnormal glutathione transport in cystic fibrosis airway epithelia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 1999;277:L113–L118. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.277.1.L113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan YY, Wang GL, Zhou JG. The ClC-3 Cl− channel in cell volume regulation, proliferation and apoptosis in vascular smooth muscle cells. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:290–296. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guggino SE. Can we generate new hypotheses about Dent disease from gene analysis? Exp Physiol. 2009;94:191–196. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2008.044586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guggino WB, Banks-Schlegel SP. Macromolecular interactions and ion transport in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:815–820. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200403-381WS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guggino WB, Stanton BA. New insights into cystic fibrosis: molecular switches that regulate CFTR. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:426–436. doi: 10.1038/nrm1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara N, Masuda H, Shoda M, Irisawa H. Stretch-activated anion currents of rabbit cardiac myocytes. J Physiol. 1992;456:285–302. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartzell C, Putzier I, Arreola J. Calcium-activated chloride channels. Annu Rev Physiol. 2005;67:719–758. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.032003.154341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey RD. Cardiac chloride currents. News Physiol Sci. 1996;11:175–181. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey RD, Hume JR. Autonomic regulation of a chloride current in heart. Science. 1989;244:983–985. doi: 10.1126/science.2543073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey RD, Hume JR. Histamine activates the chloride current in cardiac ventricular myocytes. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1990;1:309–317. [Google Scholar]

- Hermoso M, Satterwhite CM, Andrade YN, Hidalgo J, Wilson SM, Horowitz B, Hume JR. ClC-3 is a fundamental molecular component of volume-sensitive outwardly rectifying Cl− channels and volume regulation in HeLa cells and Xenopus laevis oocytes. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:40066–40074. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205132200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heusch G, Liu GS, Rose J, Cohen MV, Downey JM. No confirmation for a causal role of volume-regulated chloride channels in ischemic preconditioning in rabbits. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32:2279–2285. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiraoka M, Kawano S, Hirano Y, Furukawa T. Role of cardiac chloride currents in changes in action potential characteristics and arrhythmias. Cardiovas Res. 1998;40:23–33. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00173-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houser SR, Piacentino V, III, Weisser J. Abnormalities of calcium cycling in the hypertrophied and failing heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32:1595–1607. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Godfrey TE, Gooding WE, McCarty KS, Jr, Gollin SM. Comprehensive genome and transcriptome analysis of the 11q13 amplicon in human oral cancer and synteny to the 7F5 amplicon in murine oral carcinoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2006;45:1058–1069. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang ZM, Britton F, An C, Yuan C, Ye L, Hatton W, Duan D. Characterization of ClC-2 channel/PKA interaction in mouse heart. FASEB J. 2008;22:721.5. [Google Scholar]

- Hume JR, Duan D, Collier ML, Yamazaki J, Horowitz B. Anion transport in heart. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:31–81. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- January CT, Fozzard HA. Delayed afterdepolarizations in heart muscle: mechanisms and relevance. Pharmacol Rev. 1988;40:219–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jentsch TJ, Stein V, Weinreich F, Zdebik AA. Molecular structure and physiological function of chloride channels. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:503–568. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan I, Ramjeesingh M, Li C, Kidd JF, Wang Y, Leslie EM, Cole SP, Bear CE. CFTR directly mediates nucleotide-regulated glutathione flux. EMBO J. 2003;22:1981–1989. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komukai K, Brette F, Orchard CH. Electrophysiological response of rat atrial myocytes to acidosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002a;283:H715–H724. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01000.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komukai K, Brette F, Pascarel C, Orchard CH. Electrophysiological response of rat ventricular myocytes to acidosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002b;283:H412–H422. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01042.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunzelmann K, Schreiber R, Boucherot A. Mechanisms of the inhibition of epithelial Na+ channels by CFTR and purinergic stimulation. Kidney Int. 2001;60:455–461. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.060002455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunzelmann K, Schreiber R, Nitschke R, Mall M. Control of epithelial Na+ conductance by the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Pflugers Arch. 2000;440:193–201. doi: 10.1007/s004240000255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang F, Busch GL, Ritter M, Volkl H, Waldegger S, Gulbins E, Haussinger D. Functional significance of cell volume regulatory mechanisms. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:247–306. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.1.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemonnier L, Shuba Y, Crepin A, Roudbaraki M, Slomianny C, Mauroy B, Nilius B, Prevarskaya N, Skryma R. Bcl-2-dependent modulation of swelling-activated Cl− current and ClC-3 expression in human prostate cancer epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4841–4848. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque PC, Hume JR. ATPo but not cAMPi activates a chloride conductance in mouse ventricular myocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 1995;29:336–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsdell P, Hanrahan JW. Glutathione permeability of CFTR. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1998;275:C323–C326. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.1.C323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Ye L, McGuckin C, Hatton WJ, Duan D. Disruption of Clcn3 gene in mice facilitates heart failure during pressure overload. J Gen Physiol. 2003;122:76. [Google Scholar]

- Miller FJ, Jr, Filali M, Huss GJ, Stanic B, Chamseddine A, Barna TJ, Lamb FS. Cytokine activation of nuclear factor kappa B in vascular smooth muscle cells requires signaling endosomes containing Nox1 and ClC-3. Circ Res. 2007;101:663–671. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.151076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minagawa N, Nagata J, Shibao K, Masyuk AI, Gomes DA, Rodrigues MA, LeSage G, Akiba Y, Kaunitz JD, Ehrlich BE, LaRusso NF, Nathanson MH. Cyclic AMP regulates bicarbonate secretion in cholangiocytes through release of ATP into bile. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1592–1602. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizoguchi K, Maeta H, Yamamoto A, Oe M, Kosaka H. Amelioration of myocardial global ischemia/reperfusion injury with volume-regulatory chloride channel inhibitors in vivo. Transplantation. 2002;73:1185–1193. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200204270-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RC, Lee IY, Silverman GL, Harrison PM, Strome R, Heinrich C, Karunaratne A, Pasternak SH, Chishti MA, Liang Y, Mastrangelo P, Wang K, Smit AF, Katamine S, Carlson GA, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB, Melton DW, Tremblay P, Hood LE, Westaway D. Ataxia in prion protein (PrP)-deficient mice is associated with upregulation of the novel PrP-like protein doppel. J Mol Biol. 1999;292:797–817. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagel G, Hwang TC, Nastiuk KL, Nairn AC, Gadsby DC. The protein kinase A-regulated cardiac Cl− channel resembles the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Nature. 1992;360:81–84. doi: 10.1038/360081a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima T, Sugimoto T, Kurachi Y. Effects of anions on the G protein-mediated activation of the muscarinic K+ channel in the cardiac atrial cell membrane. Intracellular chloride inhibition of the GTPase activity of GK. J Gen Physiol. 1992;99:665–682. doi: 10.1085/jgp.99.5.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naren AP, Kirk KL. CFTR chloride channels: Binding partners and regulatory networks. News Physiol Sci. 2000;15:57–61. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.2000.15.2.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Driscoll KE, Hatton WJ, Burkin HR, Leblanc N, Britton FC. Expression, localization and functional properties of Bestrophin 3 channel isolated from mouse heart. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008a;295:C1610–C1624. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00461.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Driscoll KE, Leblanc N, Britton FC. Molecular and functional characterization of murine Bestrophin 1 cloned from heart. FASEB J. 2008b;22:1201.25. [Google Scholar]

- Okada Y, Shimizu T, Maeno E, Tanabe S, Wang X, Takahashi N. Volume-sensitive chloride channels involved in apoptotic volume decrease and cell death. J Membr Biol. 2006;209:21–29. doi: 10.1007/s00232-005-0836-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel DG, Higgins RS, Baumgarten CM. Swelling-activated Cl current, ICl,swell, is chronically activated in diseased human atrial myocytes. Biophys J. 2003;84:233a. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- Reisin IL, Prat AG, Abraham EH, Amara JF, Gregory RJ, Ausiello DA, Cantiello HF. The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator is a dual ATP and chloride channel. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:20584–20591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz PE, Ponce ZA, Schanne OF. Early action potential shortening in hypoxic hearts: role of chloride current(s) mediated by catecholamine release. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1996;28:279–290. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabirov RZ, Okada Y. ATP release via anion channels. Purinergic Signal. 2005;1:311–328. doi: 10.1007/s11302-005-1557-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder BC, Cheng T, Jan YN, Jan LY. Expression cloning of TMEM16A as a calcium-activated chloride channel subunit. Cell. 2008;134:1019–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skach WR. CFTR: new members join the fold. Cell. 2006;127:673–675. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solbach TF, Paulus B, Weyand M, Eschenhagen T, Zolk O, Fromm MF. ATP-binding cassette transporters in human heart failure. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2008;377:231–243. doi: 10.1007/s00210-008-0279-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorota S. Swelling-induced chloride-sensitive current in canine atrial cells revealed by whole-cell patch-clamp method. Circ Res. 1992;70:679–687. doi: 10.1161/01.res.70.4.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer KW, Walker JL. Intracellular chloride activity in quiescent cat papillary muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1980;238:H487–H493. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1980.238.4.H487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugita M, Yue Y, Foskett JK. CFTR Cl− channel and CFTR-associated ATP channel: distinct pores regulated by common gates. EMBO J. 1998;17:898–908. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.4.898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomaselli GF, Marban E. Electrophysiological remodeling in hypertrophy and heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;42:270–283. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00017-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Borren MM, Verkerk AO, Vanharanta SK, Baartscheer A, Coronel R, Ravesloot JH. Reduced swelling-activated Cl− current densities in hypertrophied ventricular myocytes of rabbits with heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;53:869–878. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00507-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg JI, Bett GC, Powell T. Contribution of a swelling-activated chloride current to changes in the cardiac action potential. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1997;273:C541–C547. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.2.C541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan-Jones RD. Non-passive chloride distribution in mammalian heart muscle: micro-electrode measurement of the intracellular chloride activity. J Physiol. 1979;295:83–109. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1979.sp012956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkerk AO, Tan HL, Ravesloot JH. Ca2+-activated Cl− current reduces transmural electrical heterogeneity within the rabbit left ventricle. Acta Physiol Scand. 2004;180:239–247. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6772.2003.01252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkerk AO, Veldkamp MW, Baartscheer A, Schumacher CA, Klopping C, van Ginneken AC, Ravesloot JH. Ionic mechanism of delayed afterdepolarizations in ventricular cells isolated from human end-stage failing hearts. Circulation. 2001;104:2728–2733. doi: 10.1161/hc4701.099577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkerk AO, Veldkamp MW, Bouman LN, van Ginneken AC. Calcium-activated Cl− current contributes to delayed afterdepolarizations in single Purkinje and ventricular myocytes. Circulation. 2000;101:2639–2644. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.22.2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkerk AO, Wilders R, Coronel R, Ravesloot JH, Verheijck EE. Ionic remodeling of sinoatrial node cells by heart failure. Circulation. 2003;108:760–766. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000083719.51661.B9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilela RM, Lands LC, Meehan B, Kubow S. Inhibition of IL-8 release from CFTR-deficient lung epithelial cells following pre-treatment with fenretinide. Int Immunopharmacol. 2006;6:1651–1664. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk AP, Heise CK, Hougen JL, Artman CM, Volk KA, Wessels D, Soll DR, Nauseef WM, Lamb FS, Moreland JG. CLC-3 and ICLswell are required for normal neutrophil chemotaxis and shape change. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:34315–34326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803141200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh KB, Long KJ. Properties of a protein kinase C-activated chloride current in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 1994;74:121–129. doi: 10.1161/01.res.74.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GX, Hatton WJ, Wang GL, Zhong J, Yamboliev I, Duan D, Hume JR. Functional effects of novel anti-ClC-3 antibodies on native volume-sensitive osmolyte and anion channels in cardiac and smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H1453–H1463. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00244.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Venable J, LaPointe P, Hutt DM, Koulov AV, Coppinger J, Gurkan C, Kellner W, Matteson J, Plutner H, Riordan JR, Kelly JW, Yates JR, III, Balch WE. Hsp90 cochaperone Aha1 downregulation rescues misfolding of CFTR in cystic fibrosis. Cell. 2006;127:803–815. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei L, Xiao AY, Jin C, Yang A, Lu ZY, Yu SP. Effects of chloride and potassium channel blockers on apoptotic cell shrinkage and apoptosis in cortical neurons. Pflugers Arch. 2004;448:325–334. doi: 10.1007/s00424-004-1277-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong KR, Trezise AE, Crozatier B, Vandenberg JI. Loss of the normal epicardial to endocardial gradient of cftr mRNA expression in the hypertrophied rabbit left ventricle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;278:144–149. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright AR, Rees SA. Targeting ischaemia–cell swelling and drug efficacy. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1997;18:224–228. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)01078-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright J, Morales MM, Sousa-Menzes J, Ornellas D, Sipes J, Cui Y, Cui I, Hulamm P, Cebotaru V, Cebotaru L, Guggino WB, Guggino SE. Transcriptional adaptation to Clcn5 knockout in proximal tubules of mouse kidney. Physiol Genomics. 2008;33:341–354. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00024.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang SY, Schegg K, Ye LL, Hatton WJ, Duan D. VDAC-1 may interact with CFTR to impart important cellular function in mouse heart. FASEB J. 2007;21:A799. 726.3. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang SY, Ye LL, Hatton WJ, Duan D. ATPo-activated chloride channels play a key role in postconditioning-induced cardioprotection in mouse heart. FASEB J. 2008;22:1130.10. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong D, Ye L, Neveux I, Burkin DJ, Scowen P, Evans R, Valencik M, Duan D, Hume JR. Cardiac specific inactivation of ClC-3 gene reveals cardiac hypertrophy and compromised heart function. FASEB J. 2008;22:970.25. [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Dong PH, Zhang Z, Ahmmed GU, Chiamvimonvat N. Presence of a calcium-activated chloride current in mouse ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H302–H314. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00044.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto S, Ehara T. Acidic extracellular pH-activated outwardly rectifying chloride current in mammalian cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H1905–H1914. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00965.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto-Mizuma S, Wang GX, Hume JR. P2Y purinergic receptor regulation of CFTR chloride channels in mouse cardiac myocytes. J Physiol. 2004a;556:727–737. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.059881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto-Mizuma S, Wang GX, Liu LL, Schegg K, Hatton WJ, Duan D, Horowitz TL, Lamb FS, Hume JR. Altered properties of volume-sensitive osmolyte and anion channels (VSOACs) and membrane protein expression in cardiac and smooth muscle myocytes from Clcn3−/− mice. J Physiol. 2004b;557:439–456. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.059261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YD, Cho H, Koo JY, Tak MH, Cho Y, Shim WS, Park SP, Lee J, Lee B, Kim BM, Raouf R, Shin YK, Oh U. TMEM16A confers receptor-activated calcium-dependent chloride conductance. Nature. 2008;455:1210–1215. doi: 10.1038/nature07313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye L, Dwyer L, Duan D. In vivo study of the role of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator Cl− channels in early and late ischemic preconditioning. Heart Disease. 2005;4:91. 362. [Google Scholar]

- Yin Z, Tong Y, Zhu H, Watsky MA. ClC-3 is required for LPA-activated Cl− current activity and fibroblast-to-myofibroblast differentiation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;294:C535–C542. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00291.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zygmunt AC. Intracellular calcium activates a chloride current in canine ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1994;267:H1984–H1995. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.5.H1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zygmunt AC, Gibbons WR. Calcium-activated chloride current in rabbit ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 1991;68:424–437. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.2.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]