Abstract

Treatment evaluation for alcohol problem, runaway adolescents and their families is rare. This study recruited primary alcohol problem adolescents (N = 119) and their primary caretakers from two runaway shelters and assigned them to either: 1) home-based Ecologically-Based Family Therapy (EBFT), 2) office-based Functional Family Therapy (FFT), or 3) Service as Usual (SAU) through the shelter. Findings showed that both home-based EBFT and office-based FFT significantly reduced alcohol and drug use compared to SAU at 15-months post-baseline. Measures of family and adolescent functioning improved over time in all groups. However, significant differences among the home and office-based intervention were found for treatment engagement and moderators of outcome.

Keywords: adolescents, runaways, family therapy, alcohol abuse, clinical trial

Substance abuse, mental and physical health problems among runaway and homeless youth are significant issues for those that serve this population. Limited evidence suggests that rates of alcohol abuse among this group of adolescents are similar to rates reported among homeless adults (Robertson, 1989). However, few (15%) runaway and homeless youth report ever receiving substance abuse/mental health services (Robertson, 1989). Substantial research shows that runaway and homeless youth are running away from a family situation characterized by poor parenting practices, violence, neglect and sexual abuse (Kaufman & Widom, 1999; Lindsey, Kurtz, Jarvis, Williams, & Nackerud, 2000). Poor communication and fighting with parents were the most often mentioned reasons for running (Kufeldt, Durieux, Nimmo, & McDonald, 1992; Safyer et al., 2004). Although these families are characterized by high levels of family distress, family reunification is associated with greater adolescent adjustment and lower substance use (Van Leeuwen et al., 2004). Teare, Furst, Peterson, and Authier (1992) found that in their sample of shelter youths, those not reunified with their family had higher levels of hopelessness, greater risk of suicide, more overall dissatisfaction with life and reported more family problems than those reunified. Given this research, involving the family in intervention efforts is likely critical to positive outcome. Thus, the present study compared family treatments for shelter residing runaway youth with primary alcohol problems.

Runaway Youth

Youth reside at a runaway shelter for many different reasons. Some have left home voluntarily, been locked out of their home (push-outs/throwaways), taken to the shelter by police as parents would not claim the youth at the detention center, or were removed from the home by the state (system youth). In general, street living youth avoid shelter and system contact, and ties with their families have been severed. Most youth who reside in a shelter return to a home situation and have less severe family and individual problems than do street living youth (Finkelhor, Hotaling, & Sedlak, 1990).

Runaway and homeless youth are not sampled by the national surveys of high school seniors or households as they are unemployed, school dropouts and lack family support (Kipke, Montgomery, & MacKenzie, 1993). However, several studies indicate that runaway youth consume alcohol and use drugs at significantly greater levels than non-runaway youth. Kipke, Montgomery, Simon and Iverson (1997) report that 71% of their sample (N = 432) of runaway youth were classified as having an alcohol and/or illicit drug abuse disorder, while Baer, Ginzler and Peterson (2002) found that 69% of their homeless sample met criteria for dependence on at least one substance. In two earlier studies, 50% of the runaway youth met diagnostic criteria for alcohol abuse (Robertson, 1989; Warheit & Biafora, 1991). Moreover, Kipke et al. (1993) note that runaway youth use alcohol at a younger age and have more associated problems.

In addition to alcohol and drug use, runaway youth report higher levels of family conflict, physical and sexual abuse and neglect than do non-runaway adolescents (Johnson, Aschkenasy, Herbers, & Gillenwater, 1996; Zimet et al., 1995). Runaway youth report high levels of mental health problems including depression and conduct disorder as well as high rates of teenage pregnancy (Greene & Ringwalt, 1996; Slesnick & Prestopnik, 2005).

Treatment with Runaway Youth

Few treatments are available to guide practitioners when working with runaway and homeless youth. This treatment gap is significant given the range of problems that these youth face. Three published studies have examined treatments for runaway and homeless youth. Rotheram-Borus, Koopman, Haignere, and Davies (1991) evaluated the impact of a comprehensive HIV prevention intervention (up to 30 sessions) on the high-risk behaviors of 145 runaways at residential shelters. Sessions included discussion of general knowledge of HIV/AIDS, coping skills, access to resources and individual counseling to reduce barriers to safer sex. Youth who received the comprehensive intervention reported an increase in condom use and a decrease in high-risk behavior. In working with street living youth, Cauce et al. (1994) compared an intensive case management intervention with a less intensive, service as usual case management through a drop-in center. Few differences were found between the regular case management and the intensive case management on the Child Behavior Checklist subscales, depression, problem behaviors, and substance use. The authors concluded that the greater cost of the intensive case management makes it difficult to justify given the few differences in outcomes detected. Slesnick and Prestopnik (2005) evaluated a home-based family therapy (Ecologically Based Family Therapy, EBFT) intervention with drug abusing shelter-residing youth. Findings from this efficacy study showed that youth assigned to EBFT reported greater reductions in overall substance abuse compared to youth assigned to service as usual through the shelter while other problem areas were reduced in both conditions.

Family Therapy for Adolescent Substance Abuse

Several literature reviews conclude that family therapy is an especially effective intervention for treating adolescent drug use when compared to non-family based interventions (see reviews, Liddle, 2004; Ozechowski & Liddle, 2000). However, the findings for the effectiveness of family treatment on adolescent alcohol use are mixed. Although no outcome studies were found that examined family therapy outcome for primary alcohol problem youth, four studies examined alcohol use as one of the substances used at outcome. Santisteban, Perez-Vidal, Coatsworth, and Kurtines (2003) showed that alcohol use was not differentially impacted by Brief Strategic Family Therapy compared to group therapy. Azrin et al. (1994) found that a behavioral family intervention significantly reduced alcohol use immediately at post-treatment, although a later study (Azrin et al., 2001) showed that neither the behavioral family therapy nor individual cognitive therapy impacted alcohol use. Utilizing Integrated Family and Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for adolescents meeting DSM-IV criteria for at least one psychoactive substance use disorder, Latimer, Winters, D'Zurilla, and Nichols (2003) observed a significant reduction in alcohol use frequency from 5.6 days to 2.0 days, compared to a reduction of 6.9 days to 6.0 days in the psychoeducation control group. Given the relative void of family therapy outcome studies for adolescent alcohol problem youth, and runaway youth in particular, more research is necessary to guide intervention and treatment development efforts in this area.

Current Study

In Bronfenbrenner's (1979) theory of social ecology, individuals are viewed as being nested within a complex of interconnected systems that encompass individual, family and extrafamilial (peer, school, neighborhood) factors. Behavior is seen as the product of the reciprocal interplay between the child and these systems and of the relations of the systems with each other (Henggeler & Borduin, 1995). Pickrel and Henggeler (1996) note the consensus regarding the multidetermined nature of substance use (Brook, Nomura, & Cohen, 1989; Dishion, Reid, & Patterson, 1988; Kumpfer, 1989) thus providing the rationale for a multisystemic approach to intervention (Liddle et al., 2001). Liddle (1999) notes that early family therapy models focused intervention primarily on the family unit alone using a family systems theoretical orientation. Newer family interventions include focus on the individual and extrafamilial environments utilizing a more comprehensive theoretical base. The focus on more comprehensive family treatments has derived from a shift to a multisystemic theoretical base.

Ecologically-Based Family Therapy (EBFT) was developed using a multisystemic theoretical base (Slesnick & Prestopnik, 2005). However, EBFT was modeled after the Homebuilders family preservation model in which a family crisis, such as removal of a child from the home, initiates services. One difference from the traditional family preservation model is that given findings indicating that a long-term, intensive intervention may not result in better outcomes with this population than a relatively less intensive intervention (Cauce et al., 1994), EBFT was offered in 16 sessions. Concepts from crisis intervention theory, that most families are open to change during a crisis, are incorporated into the intervention. As Post and McCoard (1994) found, these youths and families may be more amenable than usual to counseling during a crisis, and the need for intervention is intense, with the timing (when they have sought help at a shelter) critical. Thus, EBFT begins its work in bringing the family together and addressing the immediate issues associated with the youth's stay at the shelter. These issues can require immediate intervention with the school (e.g., if youth has been truant, fighting or doing poorly), probation officer (e.g., if a court appearance is near), and family (e.g., coping with high emotion, problem solving, reintegrating the youth back into the home). As with the prototypical Homebuilder's family preservation model, therapy is conducted at home. Such a home-based approach seeks to reduce barriers to treatment (childcare, transportation, organization) that families with high levels of chaos often experience. The therapist also serves as a therapeutic case manager coordinating and facilitating meetings and/or services for the youth and family based upon a needs assessment.

In-home therapy has been successful with families assessed as disorganized, chaotic and with few resources (Henggeler et al., 1991). Henggeler et al. (1991) noted that home-based interventions are particularly successful in facilitating treatment engagement of multi-problem youth. This is important since engagement and length of time in treatment have been associated with improved treatment outcomes (Stark, 1992; Szapocznik et al., 1988). Working with the family in their home, and in their neighborhood, allows the assessment of multiple ecological influences impacting the adolescent and family. In-home sessions also allow the intervention to be perceived as a natural process and enhances treatment engagement and acceptability (Henggeler et al., 1991; Joanning et al., 1992). A high percentage of missed or canceled office-based appointments occur because a family does not have reliable transportation or because the meeting time conflicts with a parent's work schedule (Henggeler & Borduin, 1995).

Home-based EBFT was compared with another viable family based intervention. Functional Family Therapy (FFT; Alexander & Parsons, 1982; Alexander & Sexton, 2002) is also a multisystemic approach that integrates and conceptually links behavioral and cognitive intervention strategies to the ecological formulation of the family disturbance. Problems such as substance use or running away are conceptualized as deriving from maladaptive family interaction patterns as well as limited coping and problem-solving skills. The primary focus of sessions is on family interaction and behavior change.

Nearly 30 years ago, Alexander and his colleagues were one of the first research groups to evaluate family-based intervention for runaway youth, including status delinquents, in reducing out of home placement, improving parent-child process and reducing negativity (Alexander, 1971; Alexander & Parsons, 1973; Barton et al., 1985). In these studies, FFT made significantly more improvements in adolescent and family functioning compared to individual therapy, a study participant-centered family therapy approach and a control group with minimal attention from probation officers. More recently, the effectiveness of FFT has been replicated across sites and settings for substance use problems and a wide range of other problem behaviors (Robbins, Alexander, Turner, & Perez, 2003; Waldron, Slesnick, Brody, Turner, & Peterson, 2001). While FFT can be provided in the home (Gordon, Graves, & Arbuthnot, 1995), the only randomized clinical trial of FFT with substance abusing adolescents has been office-based (Waldron et al., 2001). The impact of office- versus home-based treatment with direct versus indirect intervention through multiple systems, was of interest in this study. Hence, FFT was offered only in the office with intervention to systems outside the family provided indirectly through family members.

Hypotheses

It was expected that home-based EBFT and office-based FFT would show significantly greater adolescent improvement in substance use, psychological and family functioning compared to SAU. Given research suggesting that active/direct involvement within the systems impacting family members may be especially important for multi-problem youth (e.g., Henggeler et al., 1991) it was expected that positive change on the outcome measures would be greater for youth in the home-based compared to office-based family therapy. Moderators of treatment outcome including age, gender, abuse and ethnicity were also explored. This research is a step towards increasing our understanding of how best to intervene in the trajectory of substance abuse and associated problems among shelter-residing runaway youth.

Method

Participants

This was a sample of convenience. All study participants were engaged into the project through one of two runaway shelters in Albuquerque, NM. In order to be eligible for the program the adolescent had to have a primary alcohol problem (for example, alcohol dependence and marijuana abuse but not vice versa) and be between the ages of 12 and 17. Moreover, his or her family needed to reside within 60 miles of the research site, and the adolescent's parents must have agreed to the possibility of family therapy. Youth who were wards of the state and without an identified family to return to (including foster or other family member) were not eligible for the program given the family therapy requirements. Also, youth were excluded if there was evidence of unremitted psychosis or other condition which would impair their ability to understand and participate in the intervention or to consent for research participation (no youth was excluded based upon this criteria). Youth were approached by project research assistants while at the shelter and were not seeking formal treatment (especially substance abuse treatment). However, the program and the program's staff had a good reputation among the youth and staff at the shelter (Slesnick, Meyers, Meade, & Segelken, 2000), so we had a very low refusal rate, with 98% of eligible youth and parents agreeing to participate.

Study participants were between the ages of 12 and 17. All were primary alcohol using, and 106 (89%) met DSM-IV criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence; 66 (55.5%) youth had a diagnosis of alcohol dependence and 40 (33.6%) youth had a diagnosis of alcohol abuse. Further, 35 (29%) had a diagnosis of marijuana abuse, 44 (37%) had a diagnosis of marijuana dependence, six (5%) had a diagnosis of other substance abuse and 20 (17%) had a diagnosis of other substance dependence. Of those 13 adolescents not meeting criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence, all showed patterns of problem alcohol use. These 13 adolescents used alcohol on an average of 31% of the days (in the past 90) and on drinking days, drank an average of 10 standard drinks.

Design

Eligible adolescents (N = 119) and families were assigned to one of three conditions, home-based EBFT (N = 37), office-based FFT (N = 40) or SAU (N = 42), using urn randomization as described below. Assessment interviews were conducted at baseline, 3, 9 and 15 months post-baseline.

Procedure

Potentially eligible youth were approached and screened for eligibility at the shelter. Those meeting eligibility criteria were then engaged. After a review of the details of the project and signing of the research assent form, the youth's primary caretaker was contacted, and their consent was obtained. Treatment consent forms were signed at the first treatment session by all those who attended. A formal eligibility screen was conducted with the youth in which the Computerized Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (CDISC, Shaffer, 1992), sections on alcohol, drugs and psychosis were administered. If the youth did not meet formal inclusion criteria, they continued with SAU through the shelter, and their parent(s) were then notified.

Youth meeting inclusion criteria continued with the assessment battery which included self-report questionnaires, structured interviews and a urine toxicology screen. The assessment battery required approximately 3 hours to complete. Assistance was provided as needed, and participants were given frequent breaks, including the option to complete the assessment over 2 days. Upon completion of the assessment instruments study participants were randomly assigned to one of the three interventions.

Adolescents were paid $25 for completing the pretreatment assessment, and $50 for each follow-up assessment. The primary caretaker was provided five self-report questionnaires, requiring approximately 30 to 40 minutes to complete, with a stamped return envelope. The primary caretaker was paid $10 upon completion of the forms. Response from primary caretakers was very low. As findings are reported elsewhere (Slesnick & Prestopnik, 2004) they will not be reviewed here.

Follow-up appointments were scheduled at the convenience of the youth. Most follow-up assessments were conducted in the youth's home; otherwise, youth were transported to the research site for their appointment by the project research assistant. Missed appointments were rescheduled, and barriers were addressed. Project follow-up rates are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Follow-up rates by treatment modality.

| EBFT (N=37) | FFT (N=40) | SAU (N=42) | Total (N=119) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 month follow-up | 32 (86%) | 32 (80%) | 34 (81%) | 98 (82%) |

| 9 month follow-up | 32 (86%) | 29 (73%) | 33 (79%) | 94 (79%) |

| 15 month follow-up | 27 (73%) | 30 (75%) | 30 (71%) | 87 (73%) |

| Completed all assessments | 23 (62%) | 26 (65%) | 26 (62%) | 75 (63%) |

Note. N (%)

Randomization procedures

Study participants were randomized to condition using a computerized urn randomization program. The urn procedure retains random allocation and balances groups on a priori categorical variables. Although simple randomization is adequate with very large sample sizes (250+), urn balancing is preferable with smaller sample sizes (Stout, Wirtz, Carbonari, & Del Boca, 1994). The relative probabilities of assignment to treatment groups (urns) are computer adjusted based on previous randomizations to reduce the risk of nonequivalent groups. Variables were chosen based on factors thought to be most likely to impact treatment effects. The variables and categories included were gender, age (13-14, 15, 16, 17-18), ethnicity (Anglo, African-American, Hispanic, Native American, Other), number of days of substance use in the last 90 days (0-31, 31-61, 61-91), comorbidity status (Yes, No), and number of previous runaway episodes (None, 1-3, 3 or more).

Materials

A standard demographic questionnaire was administered to all study participants. This questionnaire also obtained self-reported physical and sexual abuse history.

Measures of substance use

The Form 90 (Miller, 1996) combines the timeline follow-back method (Sobell & Sobell, 1992) and grid averaging (Miller & Marlatt, 1984) for assessing widely variable alcohol and drug use patterns that characterize adolescent substance users. Several studies have established the test-retest reliability for Form 90 indices of drug and alcohol use for adults (Tonigan, Miller, & Brown, 1997; Westerberg, et al., 1999) and runaway adolescents (Slesnick & Tonigan, 2004) with kappas for different drug classes ranging from .74 to .95.

Urine toxicology screens were collected from youth at pre- and post-treatment assessment to verify self-reported illicit drug use. To address problem consequences associated with drug use, the POSIT (Rahdert, 1991) was utilized. Support for the psychometric properties of the POSIT, including convergent and discriminant validity, has been reported by McLaney, Del Boca and Babor (1994). As a measure of problems specifically associated with drinking, the Adolescent Drinking Index (ADI; Harrell & Wirtz, 1989a, 1989b) was used. This instrument differentiates youth whose drinking poses a problem for their functioning from youth whose drinking does not.

Psychological Functioning

The 120-item Youth Self-Report of the Child Behavior Checklist (YSR; Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1982) was used to assess study participants' self-reported delinquency, aggression, attention problems, somatic complaints, thought, and social problems. Achenbach and Edelbrock (1982) report test-retest reliability was .69 across a six-month interval, and criterion validity ranged from .75 to .82. The YSR scales measuring internalizing and externalizing behaviors were used in this study.

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI, Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock, & Erlbaugh, 1961) is a commonly employed self-report measure of mood, cognitive and somatic aspects of depression, and has shown good psychometric properties (Norman, Miller, & Klee, 1983; Rush et al., 1986).

The National Youth Survey Delinquency Scale (NYSDS; Elliot, Huizinga, & Ageton, 1985) is a structured interview that provides scores for general theft, crimes against persons, index offenses, drug sales and total delinquency. Test-retest reliabilities for periods between 2 weeks and 6 months range from .75 to .98, internal consistency alphas range between .65 and .92, and criterion correlations between self-report and police or parent data hover near .40 (Moffitt, 1989).

Shaffer's (1992) CDISC is a computerized instrument developed specifically to diagnose children and adolescents (Winters & Stinchfield, 1995). CDISC is administered to youth by the research assistant and we included sections on Conduct Disorder, Oppositional Defiant Disorder, Mood, Eating and Anxiety disorders. It has demonstrated excellent interrater reliability of 97% with clinicians agreeing with the diagnoses of CDISC (Wolfe, Toro, & McCaskill, 1999).

Family Functioning

The Family Environment Scale (FES; Moos & Moos, 1986) is a commonly-used and well-standardized family assessment instrument. It comprises 90 true-false items and consists of ten subscales which measure the social-environmental characteristics of families. Conflict and Cohesion subscales were used to assess family disturbance as these two areas of functioning have been shown to predict negative communication exchanges in delinquent families (Mas, 1986). Internal consistencies have ranged from .61 to .78 and test-retest reliabilities from .73 to .86 (Moos & Moos, 1986).

The Conflict Tactic Scale (CTS; Straus, 1979) was implemented to measure the occurrence of several methods of conflict resolution used by the youth and primary caretaker. Two subscales were used (verbal aggression and physical violence), with each subscale separately scored to understand the methods used in conflict resolution. The measure has shown good internal consistency with Cronbach's alpha of .83 (Yoder, 1999) in a clinical sample. CTS is a widely used measure of conflict resolution tactics (Wolfe et al., 1999).

The Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI, Parker, Tupling, & Brown, 1979) consists of 25 items and is a measure of two important dimensions of parent child relationship: perceived parental care vs. rejection, and control vs. autonomy. It has good reliability in both clinical and non-clinical samples (correlations ranging from .63 to .88) and has demonstrated construct and predictive validity with correlations ranging from .51 to .78 (Klimidis, et al., 1992; Parker, 1983; Parker et al., 1979).

Treatment

Therapist Training and Supervision

Therapists were crossed with condition in order to equate groups on therapist characteristics. The principal investigator conducted a two day didactic training in both FFT and EBFT with experienced therapists who were available to the project from prior family therapy outcome trials. Thus, while the training of community based treatment providers may need greater intensity for an effectiveness study (Elliott & Mihalic, 2004), this study included already trained family systems based therapists and ongoing supervision within a university-based setting. Two therapists conducted therapy with the majority of the youth (72%). These two therapists were female, master's level licensed professional counselors with between 2 and 5 years experience in the field. Therapist differences were investigated between the two modalities (EBFT, FFT). Differences were found in the number of treatment sessions completed (M (SD) = 10.29 (6.41), 5.24 (5.75), F (1, 52) = 9.03, p < .01), but long-term outcomes did not differ by therapist (no main effects or interactions of substance use with therapist, all p's >.10).

Both office-based FFT and home-based EBFT were offered for 16, 50-minute sessions. Audiotape recordings of all therapy sessions were used for treatment adherence checks by the supervisor and for use in supervision meetings. The supervisor ensured that 1) no sessions were conducted outside the office and 2) no individual sessions were conducted in FFT. The therapists and supervisor met weekly for supervision, and selected portions of audiotapes were reviewed, feedback was provided and problems were discussed.

Office-Based Therapy

The goal of FFT (Alexander & Parsons, 1982) is to alter dysfunctional family patterns that contribute to alcohol abuse, running away and related problem behaviors. The therapy process is best understood in terms of the two major phases in which the basic elements of the model are implemented. The first phase focuses on readiness to change and involves creating the context in which behavior change can occur. The therapist's aims in this phase are to: 1) engage the family in therapy, 2) enhance the family's motivation for change, and 3) assess the relevant aspects of family functioning to be addressed in treatment. The second phase focuses on establishing and maintaining behavior change. In this behavior change phase, the motivational framework created and the assessment data obtained in the first phase are used to guide the selection and implementation of specific behavioral change techniques.

The success of FFT with delinquent populations has been attributed to that aspect of the model which integrates a systems-theoretical framework with a behavioral treatment methodology. The behavior change phase is implemented based upon the assessment of outcomes or functions of behavior. Interpersonal function of behavior can be assessed by noting the outcome of a particular behavior in terms of its impact on family interaction. That is, the function or outcome of a behavior may be significant psychological separation from family members (i.e., distance function), greater connection or interdependency (i.e., closeness function), or a blending of marked distance and closeness (i.e., midpointing function). The therapist must replace maladaptive behaviors (running away, alcohol use) with adaptive behaviors that maintain the interpersonal functions. Family sessions also focus on interpersonal communication skills, behavioral contracting, and problem solving (i.e., applied to situations at risk for initiating runaway behavior). In this modality, all intervention occurred in the office and treatment was guided by the FFT manual (Alexander & Parsons, 1982). Moreover, while FFT can include working individually with family members, in this study, only home-based family therapists met individually with family members.

Home-Based Therapy

Ecologically-based family therapy (EBFT) is based upon the Homebuilders Family Preservation model started in several states in the 1980's. However, EBFT includes significantly fewer sessions (16). These family-based approaches share the assumption that 1) time-limited, intensive and comprehensive therapeutic services should be provided in accordance with the needs and priorities of each family, and 2) most children are better off with their own families than in substitute care (Nelson & Landsman, 1992). Families in which the youth or parent refuse to meet together are provided up to two individual sessions in order to address those concerns or barriers. Frequent meetings early in therapy capitalize on the momentum of motivated family members to meet and work through the run away crisis. Treatment is provided in the family's home or wherever the youth might be residing (e.g., shelter, foster home).

Treatment begins by developing rapport with the family while assessing the treatment needs of the family and its members. Intervention strategies are similar to other family systems approaches, including FFT. Families are guided from an intrapersonal to interpersonal interpretation of problems utilizing interpretations, questions and reframes that have relational bases. The intervention is non-confrontational and the therapist sets a non-hostile, non-judgmental tone for sessions. Other intervention strategies include cognitive-behavioral techniques which are utilized to interrupt problem behavior patterns so that new skills can be taught, practiced, and applied outside the therapy context. One goal is for youth and parents to become more confident and competent in their ability to communicate needs and expectations.

Both family and individual sessions are used and problems such as substance use and running away are addressed directly. The therapist serves as a therapeutic case manager and facilitates and coordinates appointments for family members to address various areas of need including medical care, job training, or self-help programs. Counselors may meet with school personnel and probation officers. In sum, in addition to communication and parenting skills training, services include a wide range of behavioral, cognitive, and environmental interventions, depending on the family's needs. Treatment was guided by the EBFT manual (Slesnick, 2000) developed from an efficacy trial with a separate sample of primary drug abusing runaway youth (Slesnick & Prestopnik, 2005) for which more detailed information regarding the intervention format and guidelines can be found. In brief, the engagement procedure utilized with these youth and families is described in section one of the manual. Section two identifies common themes to the therapy with runaway youth and families (e.g., youth runs from the shelter/home, transitioning youth back into the home, parent refuses to allow youth to live in the home), and organizes an approach to effectively intervene. The final section outlines the sequence of clinical tasks for each therapy session. For sessions 1 and 2, tasks include engagement, information gathering, immediate needs assessment as well as therapist process and relational tasks. Beginning in session 3, cognitive-behavioral treatment techniques are employed including communication skills practice and problem solving. Session 4 begins the generalization of change that includes role plays and interpersonal homework tasks. These tasks then continue throughout treatment.

Service as Usual

SAU consisted of primarily of informal meetings or therapy provided or arranged by shelter staff. Generally, shelter staff provided crisis intervention and assisted with placement; however, a counselor was available to talk to youth who requested assistance. Thus, service as usual most often included case management and individual therapy meetings. Youth in our study were in the shelter an average of 9 (SD = 12.9) days at the pretreatment assessment and 17 (SD = 22.7) days at post-treatment assessment, which did not differ among the three groups. Some youth received treatment outside our program. At pre-treatment, the average number of outside (non-FFT/EBFT) treatment sessions was 2 (SD = 6.7), which did not differ among the three groups. At posttreatment, the average number of outside treatment sessions was 2 (SD = 6.2), which also did not differ among groups.

Statistical Analyses

Initial analyses were conducted to examine the distributional characteristics of the variables of interest. Delinquency (NYSDS) was skewed due to some extremely high scores. To compensate for these scores, log transformations were conducted. Statistical analyses were conducted with these transformed scores, but the actual means and standard deviations are reported.1

Tests for baseline differences among modalities were conducted first, using one-way ANOVAs and chi-square tests, as appropriate. Tests for treatment differences followed, using a series of 3 (treatment modality) × 4 (time) repeated measures ANOVAs. Number of treatment sessions was used as covariate for all analyses. Since the SAU group did not meet with project therapists, the number of outside treatment sessions completed was taken from self-report on the Form 90. For FFT and EBFT groups, number of sessions was taken from therapist report, confirmed through therapy notes, while therapy received outside the project was also obtained from the Form 90. Three domains were assessed: substance use, family functioning and psychological functioning (Please refer to Table 3 for the list of dependent measures). Intent to treat analyses were completed with all study participants on all the main variables, followed by treated analyses.

Table 3. Measure of Substance Use, Family Functioning, and Psychological Functioning Assessed at Pretreatment, 3 Month Follow-up, 9 Month Follow-up, and 15 Month Follow-up According to Three Study Conditions for Intent to Treat Analyses.

| Ecologically-Based Family Therapy

|

Functional Family Therapy

|

Service As Usual

|

Time effect

|

Treatment × Time Effect

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F | p | η2 | F | p | η2 |

| Substance Use Measures

| ||||||||||||

| Percent Days of Alcohol or Drug Use (Form 90) | ||||||||||||

| Pretx | 43 | 32 | 43 | 30 | 38 | 25 | 6.72 | <.001 | .23 | 2.48 | .03 | .10 |

| 3mfu | 33 | 35 | 15 | 18 | 25 | 28 | ||||||

| 9mfu | 21 | 27 | 18 | 30 | 32 | 35 | ||||||

| 15mfu | 12 | 25 | 13 | 24 | 33 | 38 | ||||||

|

Percent Days of Only Drug Use (Form 90) | ||||||||||||

| Pretx | 34 | 36 | 32 | 32 | 28 | 28 | 3.09 | .03 | .12 | 1.75 | .12 | .07 |

| 3mfu | 22 | 32 | 13 | 18 | 20 | 28 | ||||||

| 9mfu | 15 | 24 | 17 | 30 | 29 | 35 | ||||||

| 15mfu | 11 | 25 | 9 | 21 | 30 | 39 | ||||||

|

Percent Days of Alcohol Use (Form 90) | ||||||||||||

| Pretx | 27 | 27 | 24 | 24 | 17 | 10 | 10.45 | <.001 | .31 | 1.64 | .14 | .07 |

| 3mfu | 9 | 19 | 6 | 11 | 9 | 10 | ||||||

| 9mfu | 7 | 17 | 4 | 9 | 7 | 12 | ||||||

| 15mfu | 1 | 3 | 4 | 9 | 7 | 9 | ||||||

|

Average Number of Standard Drinks (Form 90) | ||||||||||||

| Pretx | 9.67 | 6.10 | 9.84 | 5.22 | 7.59 | 3.59 | 3.41 | .02 | .13 | 1.60 | .15 | .06 |

| 3mfu | 4.36 | 6.67 | 4.68 | 5.10 | 7.41 | 5.90 | ||||||

| 9mfu | 7.83 | 15.85 | 5.27 | 5.92 | 5.23 | 5.22 | ||||||

| 15mfu | 2.30 | 4.11 | 3.60 | 5.65 | 7.46 | 14.36 | ||||||

|

Number of Substance Use Diagnoses (CDISC) | ||||||||||||

| Pretx | 1.91 | 1.20 | 2.08 | 1.09 | 2.12 | 0.82 | 8.98 | <.001 | .28 | 1.94 | .07 | .08 |

| 3mfu | 1.13 | 1.22 | 1.00 | 1.33 | 1.77 | 1.14 | ||||||

| 9mfu | 1.04 | 1.19 | 1.08 | 1.29 | 0.73 | 1.04 | ||||||

| 15mfu | 0.74 | 1.05 | 0.85 | 1.29 | 0.54 | 0.90 | ||||||

|

Adolescent Drinking Index (ADI) | ||||||||||||

| Pretx | 26.68 | 10.83 | 27.60 | 14.13 | 23.69 | 11.91 | 3.34 | .02 | .13 | 0.96 | .45 | .04 |

| 3mfu | 24.32 | 11.29 | 20.16 | 14.78 | 21.35 | 10.75 | ||||||

| 9mfu | 19.23 | 13.18 | 17.52 | 13.97 | 15.96 | 9.01 | ||||||

| 15mfu | 13.77 | 9.88 | 15.64 | 15.34 | 15.00 | 9.94 | ||||||

|

Number of Problem Consequences (POSIT) | ||||||||||||

| Pretx | 6.57 | 3.93 | 6.83 | 3.87 | 6.58 | 3.98 | 5.39 | .002 | .19 | 0.46 | .84 | .02 |

| 3mfu | 5.13 | 4.04 | 4.75 | 2.85 | 2.92 | 2.74 | ||||||

| 9mfu | 5.26 | 4.59 | 4.38 | 4.56 | 3.31 | 2.68 | ||||||

| 15mfu | 3.65 | 3.92 | 3.88 | 4.27 | 3.85 | 4.51 | ||||||

|

Psychological Functioning Measures | ||||||||||||

| Depression (BDI) | ||||||||||||

| Pretx | 16.00 | 9.42 | 16.00 | 9.65 | 9.80 | 8.35 | 1.74 | .17 | .07 | 1.01 | .42 | .04 |

| 3mfu | 11.91 | 10.35 | 10.12 | 9.61 | 6.56 | 6.55 | ||||||

| 9mfu | 9.13 | 9.68 | 5.96 | 7.15 | 6.56 | 7.83 | ||||||

| 15mfu | 8.87 | 9.13 | 8.31 | 8.64 | 5.80 | 5.23 | ||||||

|

Number of Psychiatric Diagnoses (CDISC) | ||||||||||||

| Pretx | 1.17 | 1.56 | 1.04 | 1.25 | 1.04 | 1.80 | 4.48 | .006 | .16 | .069 | .99 | .00 |

| 3mfu | 0.65 | 0.88 | 0.65 | 1.57 | 0.58 | 1.17 | ||||||

| 9mfu | 0.26 | 0.69 | 0.27 | 0.60 | 0.23 | 0.42 | ||||||

| 15mfu | 0.17 | 0.49 | 0.19 | 0.57 | 0.19 | 0.49 | ||||||

|

Internalizing Problems (YSR) | ||||||||||||

| Pretx | 20.96 | 10.13 | 20.31 | 8.99 | 17.96 | 10.23 | 1.97 | .13 | .08 | 0.43 | .86 | .02 |

| 3mfu | 17.52 | 8.87 | 15.92 | 9.40 | 13.50 | 6.44 | ||||||

| 9mfu | 14.17 | 9.21 | 14.08 | 8.63 | 12.65 | 7.24 | ||||||

| 15mfu | 14.87 | 8.31 | 14.35 | 9.43 | 12.46 | 7.22 | ||||||

|

Externalizing Problems (YSR) | ||||||||||||

| Pretx | 30.35 | 9.20 | 27.15 | 9.33 | 25.81 | 10.65 | 2.97 | .04 | .11 | 0.35 | .91 | .02 |

| 3mfu | 25.57 | 10.37 | 20.77 | 8.42 | 19.38 | 7.51 | ||||||

| 9mfu | 21.09 | 10.09 | 18.62 | 9.40 | 20.35 | 9.12 | ||||||

| 15mfu | 19.83 | 9.30 | 16.04 | 7.64 | 19.58 | 8.63 | ||||||

|

Delinquent Behaviors (NYSDS) | ||||||||||||

| Pretx | 190 | 343 | 175 | 240 | 934 | 1739 | 11.45 | <.001 | .33 | 1.51 | .18 | .06 |

| 3mfu | 36 | 50 | 24 | 66 | 92 | 147 | ||||||

| 9mfu | 40 | 108 | 194 | 699 | 58 | 103 | ||||||

| 15mfu | 36 | 87 | 16 | 43 | 22 | 50 | ||||||

|

Percentage of Days Living at Home (Form 90) | ||||||||||||

| Pretx | 71 | 25 | 64 | 30 | 59 | 40 | 2.41 | .075 | .10 | 0.65 | .69 | .03 |

| 3mfu | 60 | 39 | 45 | 42 | 62 | 38 | ||||||

| 9mfu | 81 | 35 | 75 | 35 | 81 | 32 | ||||||

| 15mfu | 78 | 34 | 73 | 35 | 86 | 28 | ||||||

|

Family Functioning Measures | ||||||||||||

| Verbal Aggression (CTS) | ||||||||||||

| Pretx | 0.48 | 0.19 | 0.51 | 0.25 | 0.36 | 0.25 | 8.53 | <.001 | .27 | 1.64 | .14 | .07 |

| 3mfu | 0.27 | 0.22 | 0.26 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.21 | ||||||

| 9mfu | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.18 | ||||||

| 15mfu | 0.25 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.21 | ||||||

|

Family Violence (CTS) | ||||||||||||

| Pretx | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 2.44 | .07 | .10 | 0.24 | .96 | .01 |

| 3mfu | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.09 | ||||||

| 9mfu | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.12 | ||||||

| 15mfu | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.14 | ||||||

|

Family Cohesion (FES) | ||||||||||||

| Pretx | 4.23 | 2.25 | 4.96 | 2.79 | 4.00 | 2.45 | 3.30 | .03 | .13 | .56 | .76 | .02 |

| 3mfu | 5.50 | 1.79 | 5.68 | 2.72 | 4.38 | 2.25 | ||||||

| 9mfu | 5.77 | 2.65 | 5.84 | 2.69 | 5.15 | 2.59 | ||||||

| 15mfu | 5.91 | 2.33 | 6.24 | 2.74 | 5.65 | 2.64 | ||||||

|

Family Conflict (FES) | ||||||||||||

| Pretx | 5.05 | 2.32 | 5.88 | 2.37 | 5.38 | 2.38 | 3.33 | .03 | .13 | 0.59 | .74 | .03 |

| 3mfu | 4.23 | 2.22 | 4.44 | 2.53 | 4.88 | 2.29 | ||||||

| 9mfu | 3.41 | 2.56 | 3.68 | 2.12 | 4.62 | 2.93 | ||||||

| 15mfu | 3.36 | 2.36 | 3.36 | 2.94 | 4.08 | 2.21 | ||||||

|

Parental Care (PBI) | ||||||||||||

| Pretx | 23.13 | 6.56 | 20.29 | 10.37 | 21.62 | 9.54 | 0.12 | .95 | .01 | 0.31 | .93 | .01 |

| 3mfu | 24.78 | 7.49 | 24.29 | 9.00 | 22.62 | 8.83 | ||||||

| 9mfu | 26.39 | 6.31 | 24.71 | 9.05 | 22.58 | 10.70 | ||||||

| 15mfu | 25.61 | 6.75 | 24.95 | 10.43 | 23.62 | 8.51 | ||||||

|

Parental Overprotectiveness (PBI) | ||||||||||||

| Pretx | 18.65 | 8.48 | 18.14 | 9.68 | 17.15 | 11.11 | 0.58 | .63 | .03 | 0.61 | .73 | .03 |

| 3mfu | 14.30 | 7.24 | 15.00 | 7.52 | 17.69 | 10.89 | ||||||

| 9mfu | 12.39 | 8.50 | 15.33 | 8.55 | 14.12 | 8.93 | ||||||

| 15mfu | 13.39 | 5.98 | 13.90 | 9.28 | 14.65 | 8.37 | ||||||

Note. Data shown is only for those study participants who completed all four assessments.

Only study participants completing all four assessments (N = 75) were included in the tests for treatment differences. However, to maximize statistical power, we decided to use all available data for individual analyses, even if individual study participants did not have complete data on all measures. Therefore, although the full sample size for the treatment outcome analyses was 75, individual analyses differ in sample size.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Average age of youth was 15.1 years, and the sample included 65 (55%) females and 54 (45%) males. Ethnic composition and other demographic characteristics can be found in Table 2.

Table 2. Demographic characteristics and substance use by treatment modality at pretreatment.

| Variable | EBFT (N=37) | FFT (N=40) | SAU (N=42) | Total (N=119) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 15.14 (1.44) | 14.83 (1.34) | 15.40 (1.29) | 15.13 (1.36) | |

| Gender (#, % Male) | 15 (41%) | 16 (40%) | 23 (55%) | 54 (45%) | |

| Ethnicity (#,%) | African Am | 3 (8%) | 2 (5%) | 1 (2%) | 6 (5%) |

| Anglo | 6 (16%) | 14 (35%) | 15 (36%) | 35 (29%) | |

| Hispanic | 20 (54%) | 16 (40%) | 16 (38%) | 52 (44%) | |

| Native Am | 6 (16%) | 4 (10%) | 3 (7%) | 13 (11%) | |

| Other | 2 (5%) | 4 (10%) | 7 (17%) | 13 (11%) | |

| # Lifetime Runs | 4.38 (5.96) | 4.33 (5.62) | 5.60 (15.20) | 4.79 (10.10) | |

| # Arrests | 2.61 (2.89) | 4.39 (9.18) | 2.89 (4.94) | 3.30 (6.25) | |

| Enrolled in school (#, %) | 21 (57%) | 23 (58%) | 15 (36%) | 59 (50%) | |

| Sexual abuse (#, %) | 12 (32%) | 21 (52%) | 13 (31%) | 46 (39%) | |

| Physical abuse (#, %) | 10 (27%) | 15 (38%) | 18 (43%) | 43 (36%) | |

| Suicide attempts (#, %) | 21 (57%) | 15 (38%) | 21 (50%) | 57 (48%) | |

| Family income | $25,630 | $28,606 | $22,754 | $25,588 | |

| (26,832) | (33,348) | (23,612) | (27,981) | ||

| Percent Days Use of: | |||||

| Alcohol | 28% (27) | 22% (22) | 25% (21) | 25% (23) | |

| Cocaine | 5% (12) | 6% (18) | 2% (5) | 4% (13) | |

| Hallucinogens | 2% (4) | 1% (2) | 2% (4) | 2% (3) | |

| Marijuana | 31% (36) | 31% (32) | 35% (32) | 32% (33) | |

| Tobacco | 59% (40) | 64% (43) | 70% (38) | 64% (40) | |

| Alcohol and Drugs Combined | 45% (33) | 44% (31) | 47% (28) | 45% (30) | |

Note. Means and Standard deviations unless otherwise specified.

Pretreatment Differences

Gender differences

Females reported more sexual abuse than males (χ2 (1) = 13.29, p < .001), but males and females did not differ in physical abuse or in their report of at least one previous suicide attempt. Other gender differences were found at baseline. Females had higher internalization scores from the YSR (t (117) = -2.62, p = .01), higher BDI scores (t (116) = -1.97, p = .05), higher CTS verbal aggression scores (t (117) = -3.36, p < .05), and lower NYSDS delinquency scores (t (116) = 3.96, p < .001). Females had lower average number of standard drinks in a drinking session (t (117) = 2.82, p < .01), and used less drugs other than alcohol (t (117) = 2.08, p < .05), but did not differ in any other substance use variables.

Ethnicity differences

Because of limited numbers in some ethnic groups, only Anglo (N = 52, 60%) and Hispanic (N = 35, 40%) youth were used in tests for group differences. Anglo and Hispanic youth did not differ in reported incidence of sexual or physical abuse or in suicide attempts. Few ethnicity differences were found in the main variables. Anglo youth reported higher conflict tactics verbal aggression (F (1, 86) = 4.53, p < .05) than Hispanic youth. No other differences were found.

Baseline treatment differences

Comparisons among FFT, EBFT and SAU on baseline measures were conducted. Based upon chi-square analyses or ANOVAs, as appropriate, groups did not differ along any of the URN randomization characteristics (all p's > .20; see section above on Randomization).

Other baseline differences were only found for delinquency from the NYSDS, with the SAU group reporting higher scores than either FFT or EBFT (F (2, 118) = 5.23, p < .01). No differences were found for any of the other main variables (substance use, psychological functioning, or family functioning), indicating that the treatment groups were relatively equal in baseline performance (all p's > .10).

Follow-up Differences

Analyses were conducted among youth who were interviewed and not interviewed for all follow-up assessments, as it was of some concern that youth with more stable environments and less severe problems would be easier to locate and interview. Analyses (using tracked vs. not tracked between-subject variable in ANOVAs or Chi-Squares) found that those youth who were tracked were not significantly different on any dependent variable or demographic characteristics from those who missed a follow-up assessment (all p's >.10). Further, the rate of tracking did not differ among treatment modalities (X2 (1) = 0.10, p >.30).

Urine Screens

Urine screens were conducted at pre-treatment and 3 month follow-up. Cannabis was the drug most commonly found on urine screens (at pretreatment: N = 34, at 3 month follow-up: N = 29). All other drugs were found in 4 or less youths' drug screens (at pretreatment: cocaine (N = 1), amphetamines (N = 4), at 3 month follow-up: opiates (N = 1), benzodiazepines (N = 1), amphetamine (N = 1), alcohol (N = 2)). The self-reported use of drug classes (on the Form 90) was checked against urine screen data. Study participants who reported no use of a particular drug class during the assessed period, but were positive on the drug screen, were identified, as these were cases where self-report was faulty. Only one adolescent (1%) reported no marijuana use and had a positive drug screen at posttreatment. Given this, we were confident that the self-reported alcohol and drug use was a valid estimate of the adolescent's use.

Treatment Participation

Differences were found for the number of sessions completed among treatment modalities. With all adolescents included, those in EBFT attended more sessions (M (SD) = 10.31 (7.57)), than FFT (M (SD) = 6.51 (6.68)), F (1, 73) = 5.31, p <.05). Treatment refusal also differed among groups, with fewer EBFT study participants refusing even one session (N = 3) than FFT study participants (N = 10) (X2 (1) = 3.91, p < .05). With engagement defined as 5 or more sessions attended, EBFT engaged more study participants (N = 27) than did FFT (N = 20) (X2 (1) = 4.27, p < .05). Further comparing EBFT and FFT, two pretreatment measures predicted engagement in therapy. Using logistic regression, externalizing behaviors predicted therapy engagement for EBFT (X2 (1) = 4.36, p < .05) but not for FFT. For EBFT, those adolescents who were engaged into therapy had higher externalizing behaviors (M (SD) = 30.37 (9.85)) than those who were not engaged (M (SD) = 21.70 (13.13)). Also, reported history of sexual abuse predicted engagement, for EBFT (X2 (1) = 3.60, p = .06). Of those reporting sexual abuse, 50% were engaged in EBFT while 40% were engaged in FFT.

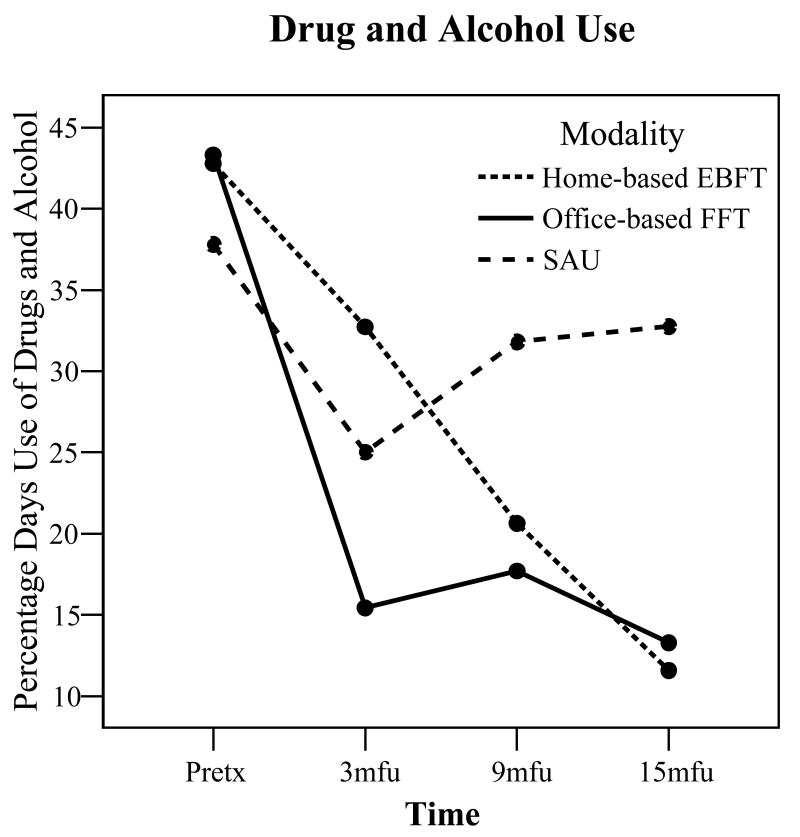

Treatment Outcome (Intent to treat)

Repeated measures analyses were conducted with each of the dependent measures. Interactions between treatment modality and time were found with two measures of substance use. The percentage days of drug and alcohol use significantly decreased over the assessment period for both family therapy conditions (EBFT: F (3,96) = 5.60, p < .01; η2 =.20; FFT: F (3,96) = 7.70, p < .001; η2 =.25), while SAU returned to near-baseline levels (p > .20; see Figure 1; overall F (6,140) = 2.48, p < .05; η2 = .10). No other dependent measures had a time by modality interaction (all p's > .10).

Figure 1.

Percent days use of all drug classes (except tobacco) from pretreatment levels to all follow-up assessments by treatment modality.

Further, most variables which did not show a differential impact among groups still decreased over time, including percent days of drug use, percent days of alcohol use, problem consequences, ADI score, CTS verbal aggression, FES conflict and cohesion, number of psychiatric diagnoses, YSR externalizing problems and NYSDS delinquency score. See Table 3 for means and standard deviations by group as well as test statistics.

Treatment Outcome (Treated analyses)

Treated analyses were conducted that parallel the intent to treat analyses, reported above. A dose of treatment was defined as 5 or more treatment sessions, and any youth in FFT or EBFT who did not receive at least 5 treatment sessions were excluded from the following analyses. Szapocznik et al. (1983) used four sessions as the cut-off for the treated analyses while Joanning et al. (1992) used 6 sessions as the cut-off. Thus, five sessions represent the midpoint between these two studies. This reduced the total N to 63 (N = 20, EBFT; N = 17, FFT; N = 26, SAU). Overall similar results were found with treated analyses as with the intent to treat analyses.

However, interactions were found for alcohol use days (F (6,116) = 2.04, p = .06; η2 = .10), with both family therapy groups significantly reducing percent days of alcohol use over the assessment periods (EBFT: F (3,57) = 11.47, p <.001; η2 = .38; FFT: F (3,57) = 6.14, p <.01; η2 = .24) as compared to SAU (p > .20). Further, the number of substance use diagnoses showed a significant interaction between time and modality (F (6,116) = 2.38, p < .05; η2 = .11). A significant difference at the 3 month follow-up (F (2,59) = 4.36, p < .05; η2 = .13), showed FFT with significantly fewer substance use diagnoses than SAU. No other dependent measures showed a time by modality interaction.

Overall time effects were found with measures of substance use (percent days of alcohol/drug use, problem consequences and ADI score). Delinquent behaviors and family verbal aggression decreased, while number of days living at home and family cohesion increased.

Secondary Analyses

Exploratory analyses were conducted to determine moderating effects of gender, ethnicity, age, and report of sexual and physical abuse on the dependent variables. To do so, each potential moderating variable was entered as an additional between subjects factor in the repeated measures analyses, similar to those conducted earlier.

Gender

A trend towards an interaction with gender for percentage of days drug and alcohol use was found (overall F (6,134) = 1.95, p = .07; η2 =.08). Use decreased significantly over time for both males and females in EBFT (Males: F (3,66) = 3.73, p < .05; η2 = .15; Females: F (3,66) = 3.51, p < .05; η2 = .14). For FFT, use only decreased significantly for males (F (3,66) = 9.21, p < .001; η2 = .30). For SAU, neither males nor females decreased their use significantly over time (p's > .10). No other differences were found.

Age

For purposes of analysis, age at pretreatment was divided into two groups (younger (ages 12-15; N = 65) and older (ages 16-17; N = 54). Of these, 43 younger and 32 older youth completed all assessments and were thus included in the repeated measures analyses.

A moderating effect of age was found for alcohol use days and internalizing problems. Percent days of alcohol use significantly decreased for both older (F (3, 66) = 7.78, p < .001; η2 =.26) and younger (F (3, 66) = 5.77, p < .01; η2 = .21) adolescents in EBFT. FFT was only effective in reducing alcohol use in older youth (F (3, 66) = 13.39, p < .001; η2 = .38), while SAU was not successful in reducing alcohol use in either older or younger youth (p > .20; overall: F (6, 134) = 2.52, p < .05; η2 = .10). Internalizing problems (YSR) also showed a moderating effect of age on modality (F (6,134) = 2.16, p = .05; η2 =.09). For the younger adolescents, both EBFT (F (3,66) = 3.13, p < .05; η2 =.12) and FFT (F (3,66) = 4.27, p < .01; η2 =.16) decreased significantly over time, while SAU did not. For the older adolescents, only SAU significantly decreased over time (F (3,66) = 5.34, p < .01; η2 =.20). A similar pattern was found for BDI (F (6,132) = 2.62, p < .05; η2 =.11).

Physical/Sexual Abuse

Abuse did not moderate the effect of treatment for any dependent variable.

Ethnicity

Ethnicity did not moderate any of the effects of treatment.

Discussion

Research supports the powerful effect of family-based interventions in reducing substance use among adolescents; however, the impact of family therapy for primary alcohol problem youth, and runaway youth more specifically, is less known. This is one of the first randomized clinical trials examining family therapy outcome with primary alcohol abusing adolescents. In this study, the impact of family therapy (both home- and office-based) was especially pronounced on alcohol use. Youth assigned to home-based EBFT showed a 97% decline in days of alcohol use (83% decline for office-based FFT), and a 77% reduction in number of standard drinks consumed on drinking days (64% for FFT) at 15 months post intake. This compares to youth assigned to SAU who showed a 59% reduction in days of alcohol use and virtually no change in number of standard drinks consumed on each drinking day. When including drug use, adolescents in both family therapies reported a 72% reduction at 15 months while SAU study participants returned to baseline use levels (overall 14% reduction in alcohol and drugs combined, and a 7% increase in days of drug use alone). The findings suggest that family therapy has a strong impact on reducing days of alcohol use (and drugs) and standard drinks compared to services provided through the community.

All three conditions showed improvements across areas of family functioning (verbal aggression, family cohesion and conflict), psychological functioning (psychiatric diagnoses, externalizing problems, delinquent behaviors, and days living at home) and substance use (number of substance use diagnoses, ADI score and number of problem consequences).

The finding of few differences in non-substance related areas though greater reductions in substance use for family therapy compared to service as usual is similar to other outcome findings (e.g., Ozechowski & Liddle, 2000; Stanton & Shadish, 1997). In order to examine mechanisms of change associated with family therapy (such as changes in family interaction), experts in the field note that observer reports of family interaction are necessary to fully examine the relationship of change in family functioning and substance use (Liddle & Dakof, 1995). Only two such studies have been conducted, and each identified greater improvement in family functioning for family compared to non-family interventions (Liddle et al., 2001; Santisteban et al., 2003). Alternatively, the findings might be due to the nature of the population. Removal of a child to a shelter represents a significant crisis, resolution of which in itself might improve the adolescent's self-reported perceptions across many areas, regardless of the intervention received.

Home versus Office Therapy

Significantly lower treatment refusal and higher engagement and treatment retention rates were found for those in home-based EBFT as compared to office-based FFT. Given that runaway youth and families are considered difficult to engage and maintain in treatment (Morrissette, 1992; Smart & Ogborne, 1994), this finding supports the inclusion of home-based therapies with this population. Sexually abused youth and those with higher externalizing problems completed more sessions in home-based EBFT compared to office-based FFT. These youth and families might experience more family chaos, requiring active involvement by the therapist in the home and across many systems in order to successfully maintain them in treatment. The higher engagement rate of youth into EBFT may be due to the context of the treatment (home-based v. office), and thus, the critical factor may not be the type of family therapy but rather the context of the therapy. Similarly, Godley et al. (2002) compared a home-based assertive after-care intervention to a non-home based service as usual condition for marijuana abusing adolescents and families. Godley et al. (2002) found significantly higher linkage rates for those in the home-based approach (92% v. 59%) compared to the non home-based intervention. Thus the unique effect of treatment context on outcome is an important area of future study.

Overall, families assigned to either the office- or home-based family therapy showed significant improvements in substance use, family and individual functioning. Two studies directly compared family therapy approaches with adolescent substance abusers and found improvements in both (Scopetta, King, Szapocznik, & Tillman, 1979; Szapocznik et al., 1983; 1986). Similar to the current study, Scopetta et al. (1979) found comparable outcomes for drug abusing adolescents assigned to an ecological version of structural family therapy that intervened with the schools, neighbors and the family, as compared to a version that intervened with the nuclear family alone. Szapocznik et al. (1983; 1986) found that one person family therapy was no more effective than conjoint family therapy. Possibly, the common theoretical base among family therapies is responsible for the similarity in outcomes.

A longer follow-up assessment would have allowed examination of whether substance use frequency would continue to decline in home-based EBFT compared to office-based FFT. Although not statistically significant, Figure 1 shows that office-based FFT had a sharp decline in substance use at 3 months but that use leveled off by 15 months. EBFT showed a consistent, gradual decrease in use to the final, 15-month post-intake follow-up. We are aware of only one study that reports family therapy findings for adolescent substance use beyond 12 months (Henggeler, Clingempeel, & Brondino, 2002), so more research is needed to examine the long-term impact of family therapy on adolescent alcohol and drug use.

Moderators of Treatment

Examination of potential moderators of adolescent family treatment such as age, gender and ethnicity has been neglected and is virtually absent (Liddle & Dakof, 1995; Ozechowski & Liddle, 2000). One exception, Henggeler et al. (1999), examined treatment by gender finding that Multisystemic Family Therapy was more effective than SAU in decreasing drug use among females at posttreatment, though no differences by gender were found at 6 months posttreatment. Most family treatment studies of drug abuse involve few females, making analyses difficult given the small sample sizes. However, our sample included a nearly equal gender representation (55% female) making analysis possible. Although abuse and ethnicity did not moderate any of the treatment effects in the current study, post-hoc analyses indicated that home-based EBFT was more effective at reducing substance abuse among females and younger adolescents than office-based FFT at 15 months post intake. Specifically, EBFT was effective at reducing alcohol and drug use for both males and females, whereas FFT showed a significant reduction in use for males only. For SAU, neither males nor females decreased their use significantly over time, and males in SAU increased their alcohol use by 50% by 15 months, suggesting that adolescent males might especially benefit from involvement in family therapy.

Home-based EBFT was also effective at reducing alcohol use for older and younger adolescents whereas office-based FFT was effective in reducing alcohol use in older adolescents only. This result is puzzling. Possibly, home-based therapists developed stronger connections with females and younger study participants which might impact our findings. Or, younger youth and females might benefit more from the active therapist involvement, while older adolescents and males might respond positively to the cognitive talk therapy approach of the office based FFT approach in this study.

Limitations

The findings need to be interpreted in light of several limitations. As noted earlier, the design of the study does not allow one to conclude whether the findings are the result of the context of treatment (home v. office) or to treatment condition (FFT v. EBFT), and future work will need to disentangle this relationship. Thus, conclusions regarding the differential effectiveness of FFT and EBFT or home and office-based therapy would be premature without further research. Few studies have compared family therapies with one another, and little evidence is available to suggest that one type of family therapy is superior to another (Slesnick, Kaminer, & Kelly, In press). Indeed, family therapies, including EBFT and FFT, may be more similar than different in that they share the underlying conceptual framework that individual problems are best understood and addressed at the interactional level (Carr, 2000). Even with this limitation, the study offers some direction for future study especially regarding examination of home-based approaches for highly chaotic families, and for runaway youth in particular.

This study's findings are based upon a sample of convenience and may not generalize to runaways who reside in shelters in other states or cities. The findings might not generalize to street living youth who do not access the shelter system, or to runaway youth who have disconnected entirely from their families, or who avoid the shelter system. Some runaway adolescents in the sample were difficult to track over time, despite considerable attempts (follow-up rates at 3, 9 and 15 months were 82%, 79% and 73%, respectively). Although we are satisfied that those that were unable to be tracked at follow-up did not differ significantly at baseline than those that were tracked, it is unknown whether these adolescents improved in the same manner as those that were tracked. The findings are based upon adolescent self-report whereas observational measures would likely provide greater sensitivity to family level change. Further, given the follow-up attrition in the study, the results may be underpowered. One-way between-subjects power analyses disregarding time effects, using the effect size found in the study, show the power to range from .71 to .59. This is lower power than is typically adequate in a study. However, this method of calculating power is a conservative estimate of power, and actual power in the analyses was likely adequate for the outcome analyses though not for the moderating analyses.

Conclusions and Future Directions

Although this study showed that runaway, alcohol problem youth are amenable and responsive to intervention efforts and that treatment effects can be sustained over a one year time period, more research is needed to identify those components of interventions that are necessary for change. Longitudinal work will allow further analysis of the theoretical supposition underlying the multisystemic treatment models. That is, in targeting multiple levels of change, positive treatment outcomes should be sustained over time to a greater extent than in those interventions that do not target multiple areas. Whether successful intervention requires that the therapists enter these multiple systems directly or intervene indirectly through family members alone requires more study. Our preliminary findings suggest that home-based interventions might have a stronger positive impact on outcomes for females and younger youth than office-based therapy.

Longitudinal research is necessary to identify critical periods for intervention to prevent family disintegration leading to chronic running away and homelessness. Identification of high risk youth and having interventions available prior to them entering the shelter system can reduce disruption to the family associated with the youth being removed from the home, and is worthy of future research focus.

Given the void of treatment outcome studies for primary alcohol abusing youth, and runaway youth especially, this study's findings are encouraging and provide useful information for continued research focus on treatment development and evaluation with this underserved and understudied population. Although office and home-based family therapies showed similarities in outcome, differences in engagement and moderators of outcome warrant future study. To date, research on runaway and homeless youth has been primarily atheoretical as researchers are at the stage of identifying and quantifying these youths' behaviors (Paradise & Cauce, 2003). The social ecology theoretical base (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) that behavior is multiply determined and must be addressed in multiple realms might be an especially useful theoretical framework for working with runaway adolescents and families whose situations are characterized by difficulties in many interconnected systems.

Footnotes

Using a log transform for the NYSDS scores rectified the skewed scores. The untransformed scores had a skewness of 6.02, 4.11, 6.39, and 5.36 and kurtosis of 48.00, 20.18, 44.24, and 34.77 for each of the assessment points (intake, 3mfu, 9mfu, 15mfu). The transformed scores skewness was -0.14, 0.71, 0.69, and 0.88 and kurtosis was -0.53, -0.32, -0.59, and -0.24 for each of the assessment points (intake, 3mfu, 9mfu, 15mfu).

References

- Achenbach TM, Edelbrock CS. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and Child Behavior Profile. Burlington, VT: Child Psychiatry, University of Vermont; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander JF. Report to juvenile court, District 1, state of Utah. Salt Lake City: 1971. Evaluation summary: Family groups treatment program. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander JF, Parsons BV. Functional family therapy: Principles and procedures. Carmel, CA: Brooks/Cole; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander JF, Parsons BV. Short term behavioral intervention with delinquent families: Impact on family process and recidivism. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1973;81:219–225. doi: 10.1037/h0034537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander JF, Sexton TL. Functional family terhapy: A model for treating high-risk, acting-out youth. In: Kaslow Florence W., editor. Comprehensive handbook of psychotherapy: Integrative/eclectic. Vol. 4. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons; 2002. pp. 111–132. [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Donahue B, Teichner GA, Crum T, Howell J, DeCato LA. A controlled evaluation and description of individual-cognitive problem solving and family-behavior therapies in dually-diagnosed conduct-disordered and substance-dependent youth. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2001;11:1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Azrin N, Donahue B, Besalel V, Kogan E, Acierno R. Youth drug abuse treatment: A controlled outcome study. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse. 1994;3:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Ginzler JA, Peterson PL. DSM-IV alcohol and substance abuse and dependence in homeless youth. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64(5):5–14. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton C, Alexander JF, Waldron H, Turner CW, Warburton J. Generalizing treatment effects of Functional Family Therapy: Three replications. American Journal of Family Therapy. 1985;17:335–347. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward C, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erlbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1961;4:53–63. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Nomura C, Cohen P. A network on influences on adolescent drug involvement : Neighborhood, school, peer, and family. Genetic, Social and General Psychology Monographs. 1989;115:125–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr A. Evidence-based practice in family therapy and systemic consultation: Child-focused problems. Journal of Family Therapy. 2000;22:29–60. [Google Scholar]

- Cauce AM, Morgan CJ, Wagner V, Moore E, Sy J, Wurzbacher K, Weeden K, Tomlin S, Blanchard T. Effectiveness of intensive case management for homeless adolescents: Results of a 3-month follow-up. Special Series: Center for Mental Health Services Research Projects. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 1994;2:219–227. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Reid JB, Patterson GR. Empirical guidelines for a family intervention for adolescent drug use. Journal of Chemical Dependency Treatment. 1988;1:189–224. [Google Scholar]

- Elliot DS, Huizinga D, Ageton SS. Explaining delinquency and drug use. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Hotaling G, Sedlak A. Missing, abducted, runaway and thrownaway children in America: First Report. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Godley MD, Godley SH, Dennis ML, Funk R, Passetti L. Preliminary outcomes from the assertive continuing care experiment for adolescents discharged from residential treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;23:21–32. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00230-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon DA, Graves K, Arbuthnot J. The effect of Functional Family Therapy for delinquents on adult criminal behavior. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 1995;22:60–73. [Google Scholar]

- Greene JM, Ringwalt CL. Youth and familial substance use's association with suicide attempts among runaway and homeless youth. Substance Use and Misuse. 1996;31:1041–1058. doi: 10.3109/10826089609072286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell AV, Wirtz PW. Screening for adolescent problem drinking: Validation of a multidimensional instrument for case identification. Psychological Assessment. 1989a;1:61–63. [Google Scholar]

- Harrell AV, Wirtz PW. Adolescent Drinking Index test and manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1989b. [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Borduin CM, Melton GB, Mann BJ, Smith LA, Hall JA, Cone L, Fucci BR. Effects of multisystemic therapy on drug use and abuse in serious juvenile offenders: A progress report from two outcome studies. Family Dynamics of Addiction Quarterly. 1991;1:40–51. [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Clingempeel WG, Brondino MJ. Four-year follow-up of multisystemic therapy with substance-abusing and substance-dependent juvenile offenders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41:868–874. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200207000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Pickrel SG, Brondino MJ. Multisystemic treatment of substance-abusing and dependent delinquents: Outcomes, treatment, fidelity, and transportability. Mental Health Services Research. 1999;1:171–184. doi: 10.1023/a:1022373813261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Borduin CM. Multisystemic treatment of serious juvenile offenders and their families. In: Schwartz IM, AuClaire P, editors. Home-based services for troubled children. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Joanning H, Thomas F, Quinn W, Mullen R. Treating adolescent drug abuse: A comparison of family systems therapy, group therapy, and family drug education. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 1992;18:345–356. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TP, Aschkenasy JR, Herbers MR, Gillenwater SA. Self-reported risk factors for AIDS among homeless youth. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1996;8:308–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman GJ, Widom SC. Childhood victimization, running away, and delinquency. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 1999;36(4):347–370. [Google Scholar]

- Kipke M, Montgomery S, MacKenzie R. Substance use among youth seen at a community-based health clinic. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1993;14:289–294. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(93)90176-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipke MD, Montgomery SB, Simon TR, Iverson EF. Substance abuse disorders among runaways and homeless youth. Substance Use and Misuse. 1997;32(78):969–986. doi: 10.3109/10826089709055866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimidis S, Minas IH, Ata AW. The PBI-BC: A brief current form of the parental bonding instrument for adolescent research. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1992;33:374–377. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(92)90058-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kufeldt K, Durieux M, Nimmo M, McDonald M. Providing shelter for street youth: Are we reaching those in need? Child Abuse and Neglect. 1992;16:187–199. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(92)90027-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumpfer KL. Prevention of alcohol and drug abuse: A critical review of risk factors and prevention strategies. In: Shaffer D, Philips I, Enzer NB, editors. Prevention of mental disorders, alcohol and other drug use in children and adolescents. OSAP Prevention Monograph No. 2. Rockville, MD: Office for Substance Abuse Prevention; 1989. pp. 309–371. [Google Scholar]

- Latimer WW, Winters CK, D'Zurilla T, Nichols M. Integrated family and cognitive-behavioral therapy for adolescent substance abusers: A stage I efficacy study. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2003;71(3):303–318. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddle HA. Theory Development in a Family-Based Therapy for Adolescent Drug Abuse. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1999;28:521–532. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP2804_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddle HA. Family-based therapies for adolescent alcohol and drug use: Research contributions and future research needs. Addiction. 2004;99 2:76–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddle HA, Dakof GA. Efficacy of family therapy for drug abuse: Promising but not definitive. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 1995;21:511–543. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey EW, Kurtz PD, Jarvis S, Williams NR, Nackerud L. How runaway and homeless youth navigate troubled waters: Personal strengths and resources. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 2000;17:115–141. [Google Scholar]

- Mas CH. Doctoral dissertation. University of Utah; Salt Lake City, UT: 1986. Attribution styles and communication patterns in families of juvenile delinquents. [Google Scholar]

- McLaney MA, Del Boca FK, Babor TF. A validation study of the Problem Oriented Screening Instrument for Teenagers (POSIT) Journal of Mental Health. 1994;3:363–376. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Marlatt GA. Manual for the Comprehensive Drinker Profile. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR. Project MATCH Monograph Series. Vol. 5. U.S. Dept. of Health; Bethesda, MD: 1996. Form 90 a structured assessment interview for drinking and related problem behaviors. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. Accommodating self-report methods to a low-delinquency culture: Experience from New Zealand. In: Klein MW, editor. Cross-national research in self-reported crime and delinquency. Norwell, MA: Kluwer Academic; 1989. pp. 43–66. [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, Moos BS. Family Environment Scale manual. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Morrissette P. Engagement strategies with reluctant homeless young people. Psychotherapy. 1992;29:447–451. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson KE, Landsman MJ. Alternative models of family preservation: Family-based services in context. Springfield, IL: Thomas; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Norman WH, Miller IW, Klee SH. Assessment of cognitive distortion in a clinically depressed population. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1983;7:133–140. [Google Scholar]

- Ozechowski TJ, Liddle HA. Family-based therapy for adolescent drug abuse: Knowns and unknowns. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2000;3:269–298. doi: 10.1023/a:1026429205294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradise MJ, Cauce AM. Substance use and delinquency during adolescence: A prospective look at an at-risk sample. Substance Use and Misuse. 2003;38:701–723. doi: 10.1081/ja-120017390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker G. Parental overprotection: A risk factor in psychosocial development. New York, NY: Grune & Stratton; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Parker G, Tupling H, Brown LB. A parental bonding instrument. British Journal of Medical Psychology. 1979;52:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Pickrel SG, Henggeler SW. Multisystemic therapy for adolescent substance abuse and dependence. Adolescent Substance Abuse and Dual Disorders. 1996;5:201–211. [Google Scholar]

- Post P, McCoard D. Needs and self-concept of runaway adolescents. The School Counselor. 1994;41:212–219. [Google Scholar]

- Rahdert E, editor. DHHS Publication No (ADM) 91-1735. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1991. The adolescent assessment and referral system manual. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson M. A report of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Berkeley, CA: Alcohol Research Group, School of Public Health, University of Southern California; 1989. Homeless youth in Hollywood: Patterns of alcohol use. [Google Scholar]