Abstract

Background

Previous research on anesthesia-related mortality in the United States was limited to data from individual hospitals. The purpose of this study was to examine the epidemiologic patterns of anesthesia-related deaths at the national level.

Methods

We searched the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, manuals for codes specifically related to anesthesia/anesthetics. These codes were used to identify anesthesia-related deaths from the US multiple-cause-of-death data files for the years 1999–2005. Rates from anesthesia-related deaths were calculated based on population and hospital surgical discharge data.

Results

We identified 46 anesthesia/anesthetic codes, including complications of anesthesia during pregnancy, labor, and puerperium (O29.0–O29.9, O74.0–74.9, O89.0–O89.9), overdose of anesthetics (T41.0–T41.4), adverse effects of anesthetics in therapeutic use (Y45.0, Y47.1, Y48.0–Y48.4, Y55.1), and other complications of anesthesia (T88.2–T88.5, Y65.3). Of the 2,211 recorded anesthesia-related deaths in the United States during 1999–2005, 46.6% were attributable to overdose of anesthetics, 42.5% to adverse effects of anesthetics in therapeutic use, 3.6% to complications of anesthesia during pregnancy, labor, and puerperium, and 7.3% to other complications of anesthesia. The estimated rates from anesthesia-related deaths were 1.1 per million population per year (1.45 for males and 0.77 for females) and 8.2 per million hospital surgical discharges (11.7 for men and 6.5 for women). The highest death rates were found in persons aged 85 years and older.

Conclusion

Each year in the United States, anesthesia/anesthetics are reported as the underlying cause in approximately 34 deaths and contributing factors in another 281 deaths, with excess mortality risk in the elderly and men.

Introduction

Mortality risk associated with anesthesia has been the subject of extensive research for many decades.1–5 In a landmark study involving ten academic medical centers and 599,500 surgical patients in the United States during 1948–1952, Beecher and Todd6 found that the anesthesia-related death rate was 64 deaths per 100,000 procedures, varying markedly by anesthetic agents, types of providers, and patient characteristics. Based on their study results, Beecher and Todd estimated that the annual number of anesthesia-related deaths in the United States was over 5100, or 3.3 deaths per 100,000 population, which was more than twice the mortality attributable to poliomyelitis at that time. The report by Beecher and Todd helped identify anesthesia safety as a public health problem and spawned many follow-up studies in the United States7–10 and other countries.11–14 This intense research effort has played an important role in the continuing improvement of anesthesia safety. In the advent of new anesthesia techniques, drugs, and enhanced training, anesthesia-mortality risk has declined from about 1 death in 1000 anesthesia procedures in the 1940s to 1 in 10,000 in the 1970s and to 1 in 100,000 in the 1990s and early 2000s.15–18

It is noteworthy that contemporary estimates of anesthesia mortality risk are based on studies conducted in Europe, Japan, and Australia.17–20 The paucity of anesthesia mortality studies in the United States in recent years is compounded by several factors. First, improvement in anesthesia safety has made anesthesia-related deaths rare events; and studying rare events usually requires large sample sizes and considerable resources. Second, there is not an established national surveillance data system for monitoring anesthesia mortality. Lastly, clinical practice of anesthesia has expanded so much that it is extremely difficult to gather exposure data. It is estimated that most surgical anesthesia procedures are now performed in ambulatory care settings.21,22 The use of anesthesia for therapeutic and diagnostic purposes is also on the rise.23

Following the 1999 publication of the Institute of Medicine’s report on medical error,24 patient safety has become a priority area of health services research. To facilitate the measurement of patient safety and the evaluation of intervention programs, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality developed over 20 patient safety indicators for use with routinely collected hospital inpatient discharge data. Each indicator refers to a group of complications or adverse events identified through specific International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification codes.25 The first indicator, purportedly measuring the safety of anesthesia, is limited to adverse effects of anesthetics in therapeutic use and overdose of anesthetics. Complications of anesthesia during labor and delivery and systemic complications, such as malignant hyperthermia due to anesthesia, are not included. The objectives of this study are to develop a comprehensive set of anesthesia safety indicators based on the latest version of the International Classification of Diseases and to apply these indicators to a national data system for understanding the epidemiology of anesthesia-related mortality.

Materials and Methods

The study protocol was reviewed and approved for exemption of informed consent by the Columbia University Institutional Review Board (New York, NY, United States).

ICD-10 Codes

The International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) is the standard classification system for recording and reporting diseases, injuries, and other health conditions.26 Sponsored by the World Health Organization, this disease classification system is revised periodically and used by many countries for the compilation of mortality and morbidity data. It also serves as the basis for international comparison of health statistics. The 10th revision (ICD-10) was implemented for coding and classifying mortality data from death certificates in the United States as of January 1, 1999. For the purpose of the present study, we developed a list of ICD-10 codes for medical conditions related to anesthesia or anesthetics (Table 1). These codes were identified by screening all the chapters of ICD-10 and informed by a thorough review of the research literature pertaining to anesthesia mortality and ICD.

Table 1.

International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) Codes for Anesthesia-related Conditions

| ICD-10 Code | Description |

|---|---|

| Complications of Anesthesia during Pregnancy, Labor, and Puerperium | |

| Pregnancy (O29.0–O29.6, O29.8–O29.9) | |

| O29.0 | Pulmonary complications |

| O29.1 | Cardiac complications |

| O29.2 | Central nervous system complications |

| O29.3 | Toxic reaction to local anesthesia |

| O29.4 | Spinal and epidural anesthesia-induced headache |

| O29.5 | Other complications of spinal and epidural anesthesia |

| O29.6 | Failed or difficult intubation |

| O29.8 | Other complications |

| O29.9 | Unspecified complications |

| Labor and Delivery (O74.0–O74.9) | |

| O74.0 | Aspiration pneumonitis |

| O74.1 | Other pulmonary complications |

| O74.2 | Cardiac complications |

| O74.3 | Central nervous system complications |

| O74.4 | Toxic reaction to local anesthesia |

| O74.5 | Spinal and epidural anesthesia-induced headache |

| O74.6 | Other complications of spinal and epidural anesthesia |

| O74.7 | Failed or difficult intubation |

| O74.8 | Other complications |

| O74.9 | Unspecified complications |

| Puerperium (O89.0–O89.6, O89.8–O89.9) | |

| O89.0 | Pulmonary complications |

| O89.1 | Cardiac complications |

| O89.2 | Central nervous system complications |

| O89.3 | Toxic reaction to local anesthesia |

| O89.4 | Spinal and epidural anesthesia-induced headache |

| O89.5 | Other complications of spinal and epidural anesthesia |

| O89.6 | Failed or difficult intubation |

| O89.8 | Other complications |

| O89.9 | Unspecified complications |

| Overdose of Anesthetics | |

| T41.0 | Inhaled anesthetics |

| T41.1 | Intravenous anesthetics |

| T41.2 | Other and unspecified general anesthetics |

| T41.3 | Local anesthetics |

| T41.4 | Unspecified anesthetics |

| Adverse Effects of Anesthetics in Therapeutic Use | |

| Y45.0 | Opioids and related analgesics |

| Y47.1 | Benzodiazepines |

| Y48.0 | Inhaled anesthetics |

| Y48.1 | Parenteral anesthetics |

| Y48.2 | Other and unspecified general anesthetics |

| Y48.3 | Local anesthetics |

| Y48.4 | Unspecified anesthetics |

| Y55.1 | Skeletal muscle relaxants (neuromuscular blocking agents) |

| Other Complications of Anesthesia | |

| T88.2 | Shock due to anesthesia in which the correct substance was properly administered |

| T88.3 | Malignant hyperthermia |

| T88.4 | Failed or difficult intubation |

| T88.5 | Other complications of anesthesia, Hypothermia following anesthesia |

| Y65.3 | Endotracheal tube wrongly placed |

In previous studies,6,18 anesthesia-related deaths were usually divided into two groups based on clinical judgment: deaths caused primarily by anesthesia and deaths in which anesthesia played a partial role. In this study, the role anesthesia played in the death was based on the causal chain of events leading to death as identified by the order on the death certificate and ICD coding guidelines. Anesthesia-related deaths were operationally defined as deaths that included one of the anesthesia-related codes (Table 1) as the underlying cause of death or included at least one anesthesia-related code as a listed cause among the multiple causes of death. We grouped the identified ICD-10 codes into four categories: (1) complications of anesthesia during pregnancy, labor, and puerperium; (2) overdose of anesthetics (exclusive of abuse of these substances); (3) adverse effects of anesthetics in therapeutic use; and (4) other complications of anesthesia in surgical and medical care (Table 1). In 5% of the anesthesia-related deaths, there was more than one anesthesia-related ICD-10 code in the multiple causes. For the purposes of this analysis, the death was categorized into the first listed ICD-10 code included in table 1.

Data Sources

Mortality data for this study came from the multiple-cause-of-death data files of the National Vital Statistics System, maintained by the National Center for Health Statistics.a Deaths were limited to those occurring within the United States. US citizens and military personnel who died outside of the United States are not included. The mortality data files are based on death certificates compiled by individual states and contain one record for each decedent. Data collected from the death certificate include information about the decedent’s demographic characteristics and causes of death. Up to 20 ICD-10 codes are recorded for each death. The underlying cause of death is selected from among all listed causes as the medical condition or the circumstance that triggered the chain of morbid events leading directly to death; and a contributing cause is a medical condition that aggravated the morbid sequence resulting in the fatality.27

Using the ICD-10 codes listed in Table 1 and the multiple-cause-of-death data files for the years 1999–2005, we identified anesthesia-related deaths. The records for these anesthesia-related deaths served as the mortality data for this study.

Statistical Analysis

Death rates were computed in two ways. First, we calculated the annual rates of anesthesia-related deaths per million population using data from the US Census Bureau for the study period. The annualized population-based death rate is a widely accepted public health measure, reflecting the portion of the general population that dies from a given health problem each year. Secondly, we estimated the risk of hospital anesthesia-related mortality based on the number of anesthesia-related deaths that occurred in hospitals as inpatients as recorded on the death certificate and national estimates of hospital surgical discharges. National estimates of hospital surgical discharges for the study period were generated from the National Hospital Discharge Survey using the defined surgical procedural codes28 and were used as a proxy measure of exposure to anesthesia among hospital inpatients.

Although mortality data are not subject to sampling error, they may be affected by random variation. Assuming deaths follow a Poisson probability distribution, the standard error associated with the number of deaths is the square root of the number of deaths.29 The National Hospital Discharge Survey data were based on a multi-stage random sampling scheme and the national estimate of the annual number of hospital discharges with a surgical procedure had a relative standard error of about 4%.28 The standard errors were calculated using SUDAAN Release 9.0.1 (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC).

Results

Frequency Distribution

During the seven-year study period, there were a total of 2,211 anesthesia-related deaths. Anesthesia complications were the underlying cause in 241 (10.9%) of these deaths and a contributing factor in the remaining 1,970 (89.1%) deaths. Overall, 46.6% of the anesthesia-related deaths were due to overdose of anesthetics, followed by adverse effects of anesthetics in therapeutic use (42.5%), anesthesia complications during pregnancy, labor, and puerperium (3.6%), and other complications of anesthesia (7.3%) (Table 2). Of the 241 deaths with anesthesia/anesthetics as the underlying cause of death, 79.7% resulted from adverse effects of anesthetics in therapeutic use, 19.1% resulted from anesthesia complications during pregnancy, labor, and puerperium, and 1.2% from wrongly placed endotracheal tubes.

Table 2.

Anesthesia-related Deaths by International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) Code, United States, 1999–2005

| ICD-10 Code | Number of Deaths | % |

|---|---|---|

| Complications of Anesthesia during Pregnancy, Labor, and Puerperium | 79 | 3.6 |

| Cardiac Complications | 60 | 2.7 |

| Overdose of Anesthetics | 1,030 | 46.6 |

| Inhaled anesthetics | 233 | 10.5 |

| Intravenous anesthetics | 419 | 19.0 |

| Other and unspecified general anesthetics | 254 | 11.5 |

| Local anesthetics | 86 | 3.9 |

| Unspecified anesthetics | 38 | 1.7 |

| Adverse Effects of Anesthetics in Therapeutic Use | 940 | 42.5 |

| Opioids and related analgesics | 439 | 19.9 |

| Benzodiazepines | 42 | 1.9 |

| Other and unspecified general anesthetics | 40 | 1.8 |

| Local anesthetics | 137 | 6.2 |

| Unspecified anesthetics | 257 | 11.6 |

| Other Complications of Anesthesia | 162 | 7.3 |

| Malignant hyperthermia | 22 | 1.0 |

| Failed or difficult intubation | 50 | 2.3 |

| Total | 2,211 | 100.0 |

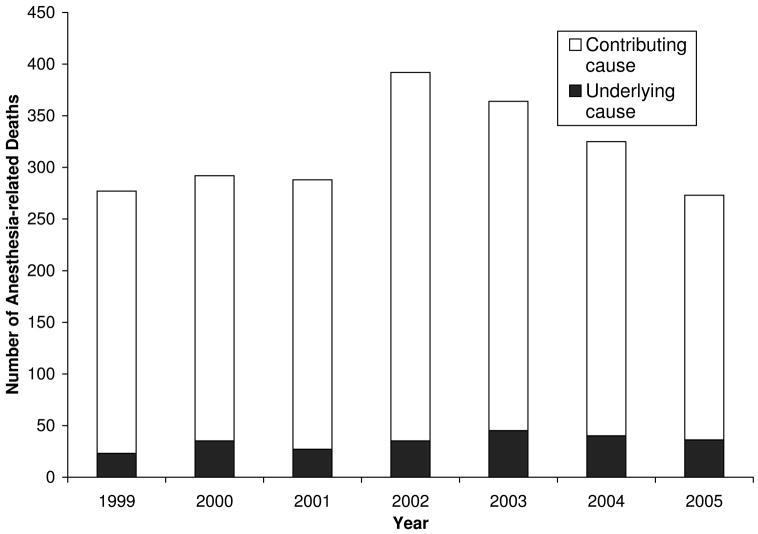

The number of anesthesia-related deaths averaged 315 deaths per year, including 34 deaths caused primarily by anesthesia/anesthetics (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Annual numbers of deaths caused primarily (underlying cause) or partially (contributing cause) by anesthesia/anesthetics, United States, 1999–2005

Males outnumbered females in anesthesia-related deaths by an 80% margin (1428 vs. 783). The majority (54.9%) of the decedents were aged 25 to 54 years.

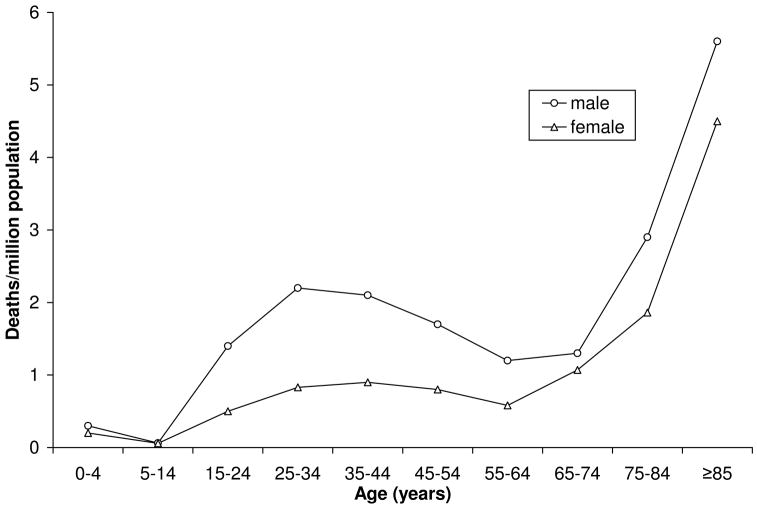

Population-based Death Rate

The anesthesia-related death rate was 1.1 per million population per year, with the rate for males almost twice the rate for females (1.45 vs. 0.77). The death rate varied with age (Figure 2). For both sexes, the lowest rate was found in children aged 5 to 14 years and the highest rate in those aged 85 or older. Males had higher death rates than females throughout the life span and the gap between sexes was especially pronounced in young and middle-age adults (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Annual anesthesia-related death rates per million population by sex, United States, 1999–2005

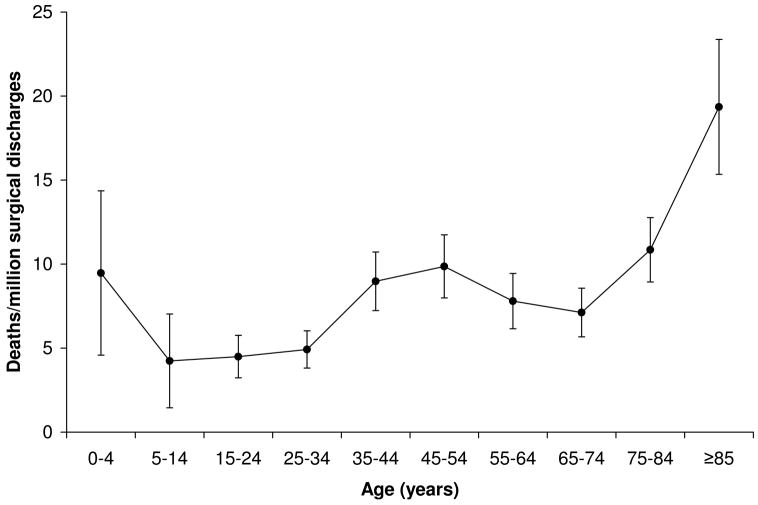

Mortality Risk among Surgical Inpatients

There were an estimated 105.7 million surgical discharges from US hospitals during the study period. Of the 2,211 anesthesia-related deaths, 867 died in hospitals, 348 in ambulatory care settings as outpatients, 46 on arrival, 258 at homes, 44 in hospice facilities, 315 at nursing homes or long term care facilities, 327 in other places, and 6 with the place of death unknown. The estimated mortality risk from anesthesia complications for inpatients was 8.2 (867/105.7, 95% confidence interval 7.4–9.0) deaths per million hospital surgical discharges (11.7, 95% confidence interval 10.3–13.1 for men and 6.2, 95% confidence interval 5.5–7.0 for women). The age pattern in mortality risk generally followed the pattern in population-based death rates, with substantially increased risk in the elderly (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Annual in-hospital anesthesia-related death rates per million hospital surgical discharges and 95% confidence intervals by age, United States, 1999–2005

Discussion

Since the first release of the patient safety indicators in 2001, a number of studies have assessed the utility of the individual indicators and in different patient groups.30–34 As a screening tool for identifying potential patient safety problems at the hospital level, patient safety indicators are found to be clinically relevant, effective and efficient. None of these studies, however, has specifically evaluated the indicator measuring anesthesia safety. As part of our effort to close this research gap, we developed four anesthesia safety indicators based on the latest version of the ICD. These indicators measure more complications and adverse events of anesthesia/anesthetics than the one proposed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality,25 and can be used to address the mortality risk. Specifically, we have added a category of complications of obstetric anesthesia, and a category of systemic complications that are rare occurrences but are of special concern to anesthesiologists, such as shock due to anesthesia, malignant hyperthermia due to anesthesia, and failed or difficult intubation. The US Department of Health and Human Services has proposed to the Congress to adopt a clinical modification of the ICD-10 codes in reporting clinical diagnoses and procedures by October 2011.b The anesthesia safety indicators developed in this study need to be validated once ICD-10 Clinical Modification coded health care utilization data become available.

Other researchers have used ICD-9 codes in studies of anesthesia morbidity and mortality.35,36 Our application of the anesthesia safety indicators to the ICD-10 coded multiple-cause-of-death data files produced several notable findings. First, our results indicate that the numbers of anesthesia-related deaths in the United States averaged about 315 deaths per year from 1999 to 2005. About 11% of these deaths were caused primarily by anesthesia/anesthetics. This proportion is consistent with previous studies.17,37,38 The death rate from complications and adverse events associated with anesthesia/anesthetics during the study period was estimated at 1.1 per million population, which represents a 97% reduction compared to the reported rate for the years 1948–1952.6 Based on the number of anesthesia-related deaths occurring in hospitals and hospital surgical discharges, we estimated that the mortality risk of anesthesia for surgical inpatients was 0.82 in 100,000. The risk of anesthesia-related deaths estimated with this methodology is compatible with recent reports from other countries.17,18,20 For instance, in Australia where there is a national registry for anesthesia-related deaths, the mortality risk is estimated to be 0.5 per 100,000.18

Our findings should be interpreted with caution. First, the anesthesia safety indicators developed in this study are based on a limited number of ICD-10 codes, which capture only the death certificates in which an anesthesia complication or adverse event was listed among the multiple causes of death. This limitation can be aggravated when the indicators are applied to hospital discharge data to study anesthesia-related morbidity because clinical documentation of complications may vary with hospitals and the severity of complications.

Second, our data on anesthesia-related mortality came solely from the multiple-cause-of-death data files of the National Vital Statistics System. As the most authoritative source of national mortality data in the United States, the multiple-cause-of-death data files are known for their completeness of data ascertainment, uniformity in format and content, and standardized protocols for reporting, coding, and processing.39 To reduce coding errors, the National Center for Health Statistics uses automated coding systems in combination with manual checking. In the past decade, the National Center for Health Statistics implemented a series of interventional programs (e.g., clearer instructions for data reporting and processing, more timely filing of amendments, electronic death registration, and querying the states about specific data items).39 Nevertheless, the validity and reliability of the multiple-cause-of-death data remain a concern. Although previous research has shown a high reliability of the multiple-cause-of-death data for some diseases (such as cancer and external causes),40 their sensitivity and specificity for detecting anesthesia-related deaths have not been rigorously examined. It is likely that the case definition we used in this study may have missed a portion of anesthesia-related mortality, particularly those deaths in which complications and adverse events of anesthesia/anesthetics played only a contributory role. On the other hand, some of the deaths associated with anesthetics or analgesics identified through the ICD-10 codes may not be related to anesthesia practice.

Finally, we based our estimates of death rates on population data and mortality risk on hospital surgical discharges. The population-based rates are valuable from a public health perspective but should be further refined in future studies. Specifically, deaths from complications of anesthesia during pregnancy, labor and puerperium are confined to women of reproductive age, thus the mortality risk should be estimated using age- and sex-appropriate denominator data.

Our estimate of anesthesia-related mortality risk for surgical inpatients is also susceptible to biases. It is conceivable that some of the anesthesia-related deaths occurring in hospitals might have resulted from exposure in ambulatory care settings or from exposure in nonsurgical therapeutic and diagnostic procedures. In addition, it is possible that some deaths that occurred outside of hospitals may have been related to complications from inpatient anesthesia. After a ten-year hiatus, the National Survey of Ambulatory Surgery from the National Center for Health Statistics was fielded in 2006 with updates to reflect the changing environment in ambulatory surgery. The lack of a comprehensive data system monitoring anesthesia exposure is a problem that has hindered research efforts in the United States and other countries for many years. With the rapid growth of clinical anesthesia services, considering methods for on-going national surveillance for anesthesia exposure and outcomes is imperative.

The results of our study suggest that the United States has experienced a 97% decrease in anesthesia-related death rates since the late 1940s and the mortality risk from complications and adverse events of anesthesia/anesthetics for surgical inpatients is similar to the reports from other countries, at about 1 in 100,000. Our study found that 42.5% of anesthesia-related deaths were attributable to adverse effects of anesthetics in therapeutic use. With the increased use of anesthesia outside of the traditional operating room setting,21,22 continued monitoring of the safety of anesthesia is warranted.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Lois Fingerhut, MA, Dr. Diane Makuc, DrPH, and Dr. Jennifer Madans, PhD, of the National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Hyattsville, Maryland, USA) for helpful comment on an earlier version of the manuscript. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Funding Disclosure: This research was supported in part by grants R01AG13642 and R01AA09963 from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland.

Footnotes

Meetings at which the work has been presented: The American Society of Anesthesiologists Annual Meeting, October 20th, 2008, Orlando, Florida.

Vital Statistics Data Available Online, Centers for Disease Control, National Center for Health Statistics. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/dvs/Vitalstatsonline.htm. Last accessed November 17th, 2008.

http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/2008pres/08/20080815a.html. Last accessed November 17th, 2008

Contributor Information

Guohua Li, Professor and Director, Center for Health Policy and Outcomes in Anesthesia and Critical Care, Department of Anesthesiology, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, NY.

Margaret Warner, Epidemiologist, Office of Analysis and Epidemiology, National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Hyattsville, MD.

Barbara H. Lang, Research Assistant, Department of Anesthesiology, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, NY.

Lin Huang, Statistician, Department of Biostatistics, Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, New York, NY.

Lena S. Sun, Professor, Department of Anesthesiology, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, NY.

References

- 1.Trent J, Gaster E. Anesthetic deaths in 54,128 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 1944;119:954–8. doi: 10.1097/00000658-194406000-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waters RM, Gillespie NA. Deaths in the operating room. Anesthesiology. 1944;5:113–28. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dornette WHL, Orth OS. Death in the operating room. Curr Res Anesth Analg. 1956;35:545–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hingson RA, Holden WD, Barnes AC. Mechanisms involved in anesthetic deaths. A survey of OR and obstetric delivery room related mortality in the University Hospitals of Cleveland, 1945–1954 NY. State J Med. 1956;56:230–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aitkenhead AR. Injuries associated with anesthesia: a global perspective. Br J Anaesth. 2005;95:95–109. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beecher HK, Todd DP. A study of deaths associated with anesthesia and surgery: based on a study of 599,548 anesthesias in ten institutions, 1948–1952, inclusive. Ann Surg. 1954;140:2–34. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195407000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schapira M, Kepes ER, Hurwitt ES. An analysis of deaths in the operating room and within 24 hours of surgery. Anesth Analg. 1960;39:149–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phillips OC, Frazier TM, Graff TD, DeKornfeld TJ. The Baltimore Anesthesia Study Committee. JAMA. 1960;174:2015–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.1960.03030160001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Memery HN. Anesthesia mortality in private practice: a ten-year study. JAMA. 1965;194:1185–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greene NM, Banister WK, Cohen B, Keet JE, Mancinelli MJ, Welch ET, Welch HJ. Survey of deaths associated with anesthesia in Connecticut. Conn Med. 1959;23:512–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Minuck M. Death in the operating room. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1967;14:197–204. doi: 10.1007/BF03003720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clifton BS, Hotten WIT. Deaths associated with anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 1963;35:250–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/35.4.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrison GG. Death attributable to anaesthesia: a 10-year survey, 1967–1976. Br JAnaesth. 1978;50:1041–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/50.10.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gebbie D. Anaesthesia and death. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1966;13:390–6. doi: 10.1007/BF03002181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dripps RD, Lamont A, Eckenhoff JE. The role of anesthesia in surgical mortality. JAMA. 1961;178:261–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.1961.03040420001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tiret L, Desmonts JM, Hatton F, Vourc’h G. Complications associated with anaesthesia-- a prospective survey in France. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1986;33:336–44. doi: 10.1007/BF03010747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arbous MS, Grobbee DE, van Kleef JW, de Lange JJ, Spoormans HHAJM, Touw P, Werner FM, Meurshing AEE. Mortality associated with anaesthesia: a qualitative analysis to identify risk factors. Anaesthesia. 2001;56:1141–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2001.02051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gibbs N, Borton C. Report of the Committee convened under the auspices of the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists. Melbourne: Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists; 2006. Safety of Anaesthesia in Australia: A review of anaesthesia related mortality, 2000–2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawashima Y, Takahashi S, Suzuki M, Morita K, Irita K, Iwao Y, Seo N, Tsuzaki K, Dohi S, Kobayashi T, Goto Y, Suzuki G, Fujii A, Suzuki H, Yokoyama K, Kugimiya T. Anesthesia-related mortality and morbidity over a 5-year period in 2,363,038 patients in Japan. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2003;47:809–17. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2003.00166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mackay P. Report of the Committee convened under the auspices of the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists. Melbourne: Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists; 2002. Safety of Anaesthesia in Australia: A review of anaesthesia related mortality, 1997–1999. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lagoe RJ, Milliren JH. Changes in ambulatory surgery utilization 1983–88: a community-based analysis. Am J Public Health. 1990;80:869–71. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.7.869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fleisher LA, Pasternak LR, Lyles A. A novel index of elevated risk of inpatient hospital admission immediately following outpatient surgery. Arch Surg. 2007;142:263–8. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.142.3.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koch M, Dayan S, Barinholtz D. Office-based anesthesia: an overview. Anesthesiol Clin North America. 2003;21:417–43. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8537(02)00079-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Institute of Medicine. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health Care System. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Patient Safety Indicators, Version 3.2. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tenth Revision. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Health Related Problems. [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Center for Health Statistics. Instructions for Classifying the Underlying Cause-of-Death, ICD-10. Albany, NY: WHO Publications Center; 2008. pp. 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- 28.DeFrances CJ, Hall MJ. 2005 National Hospital Discharge Survey. Adv Data. 2007;12:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kung HC, Hoyert DL, Xu JQ, Murphy SL. Deaths: Final data for 2005 National vital statistics reports. 10. Vol. 56. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller MR, Elixhauser A, Zhan C, Meyer GS. Patient Safety Indicators: using administrative data to identify potential patient safety concerns. Health Serv Res. 2001;36:110–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Romano PS, Geppert JJ, Davies S, Miller MR, Elixhauser A, McDonald KM. A national profile of patient safety in U.S. hospitals. Health Aff. 2003;22:154–66. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.2.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhan C, Miller MR. Excess length of stay, charges, and mortality attributable to medical injuries during hospitalization. JAMA. 2003;290:1868–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.14.1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosen AK, Rivard P, Zhao S, Loveland S, Tsilimingras D, Christiansen CL, Elixhauser A, Romano PS. Evaluating the patient safety indicators how well do they perform on Veterans Health Administration data? Med Care. 2005;43:873–84. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000173561.79742.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sedman A, Harris JM, II, Schulz K, Schwalenstocker E, Remus D, Scanlon M, Bahl V. Relevance of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Patient Safety Indicators for Children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2005;115:135–45. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Donnelly EF, Buechner JS. Complications of anesthesia. Med Health R I. 2001;84:341–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lienhart A, Auroy Y, Pequignot F, Benhamou D, Warszawski J, Bovet M, Jougla E. Survey of anesthesia-reltaed mortality in France. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:1087–97. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200612000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lunn JN, Mushin WW. Mortality associated with anaesthesia [Special Communication] Anaesthesia. 1982;37:856. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1982.tb01824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tikkanen J, Hovi-Viander M. Death associated with anaesthesia and surgery in Finland in 1986 compared to 1975. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1995;39:262–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1995.tb04054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anderson R. Edited by the Committee for the Workshop on the Medicolegal Death Investigation System. Washington, D.C: The National Academies Press; 2003. Quality of Death Certificate Data, Medicolegal Death Investigation System: Workshop Summary; pp. 40–2. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Albertsen PC, Walters S, Hanley JA. A comparison of cause of death determination in men previously diagnosed with prostate cancer who died in 1985 or 1995. J Urol. 2000;163:519–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]