Abstract

Objective

The primary objective of the study was to prospectively assess quality of life (QOL) among women at increased risk of ovarian cancer who are undergoing risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO) or serial screening.

Methods

Women at increased risk of ovarian cancer who were undergoing RRSO were recruited into the study. At-risk women undergoing serial screening for early detection of ovarian cancer served as a comparison group. Participants completed measures of QOL, sexual functioning, body image, depressive symptoms, and a symptom checklist at baseline (prior to surgery for women obtaining RRSO), and then at 1-month, 6-months, and 12-months post baseline.

Results

Women who underwent surgery reported poorer physical functioning, more physical role limitations, greater pain, less vitality, poorer social functioning, and greater discomfort and less satisfaction with sexual activities at 1-month assessment compared to baseline. In contrast, women undergoing screening experienced no significant decrements in QOL or sexual functioning at 1-month assessment. Most QOL deficits observed in the surgical group were no longer apparent by 6-month assessment. Women in the surgery group were more likely to report hot flashes and vaginal dryness, but over time, symptoms of vaginal discomfort decreased to a greater extent in women who had RRSO compared to women undergoing screening. No differences in body image or depressive symptoms were observed between the two groups at any time point.

Conclusions

Short-term deficits in physical functioning and other specific domains of QOL were observed following RRSO, but most women recovered baseline functioning by 6- and 12-month assessments. Issues regarding the potential impact of surgery on short-term sexual functioning should be considered and weighed carefully, particularly among younger women.

Keywords: quality of life, ovarian cancer, prophylactic surgery, screening

Introduction

Women with a family history of ovarian cancer or a documented deleterious mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2 are at increased risk of developing ovarian cancer [1]. Screening options for high-risk women include serum CA125 evaluation and transvaginal ultrasound (TVU). Although practice guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommend concurrent TVU and CA125 every 6 months for those high-risk women who have not elected to undergo risk reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO) [2], numerous studies show neither has acceptable sensitivity and specificity for detecting early stage disease, nor do they impact morbidity and mortality [3–5].

Due to the limitations of screening for ovarian cancer, women at increased risk often consider risk-reducing surgery. Studies of BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers indicate that RRSO significantly reduces ovarian and breast cancer risk [6–9]. NCCN guidelines and other professional organizations recommend RRSO “ideally between 35 and 40 years or upon completion of child bearing” [2, 10]. However, it should be noted that the NCCN guidelines couch these recommendations within a multidisciplinary consultative process in which reproductive desires, assessment of cancer risk, and the pros and cons of surgery along with the potential sequelae of surgery are fully discussed. Quality of life issues, which have not been well-studied, are particularly pertinent to these discussions.

Aside from the potential medical benefits of RRSO, very little is known about women’s quality of life (QOL) following surgery. Patients who undergo RRSO have reported various physical and psychological sequelae following surgery [11], including post-operative complications, menopausal symptoms, and negative effects on body image and sexuality [12]. However, it has also been demonstrated that continued surveillance at regular intervals, with its attendant worry over the possibility of detecting an abnormality each time and the constant reminder of one’s increased cancer risk, can also contribute to negative effects on psychosocial functioning by increasing cancer-related anxiety and decreasing QOL [13, 14].

To date, few studies have prospectively assessed women’s QOL following RRSO in comparison to at-risk women undergoing screening. Retrospective studies have reported overall QOL in women following RRSO to be comparable to that of the general population [15–17]. However, women who had surgery were more likely to report physical symptoms that reduced sexual satisfaction (e.g.,. vaginal dryness) and poorer sexual functioning than women who had not had RRSO [16, 17].

Due to the cross-sectional and retrospective methodologies utilized in previous studies, potential changes in QOL over time among high-risk women have not been well-documented. Two prospective studies examined levels of distress and anxiety among at-risk women before and after RRSO [18, 19] but neither study reported QOL outcomes. In sum, serial screening and RRSO represent the primary risk management and risk reduction options currently recommended for women at increased risk of ovarian cancer, but few prospective data are available regarding the effects of these prevention strategies on women’s QOL over time. Thus, the primary objective of the present study was to prospectively assess QOL among women at increased risk for ovarian cancer who are undergoing RRSO or serial screening.

Methods

Participants and procedures

Participants were identified through the Family Risk Assessment Program (FRAP) at Fox Chase Cancer Center between December, 1999 and September, 2004. Eligible women were ages 25 and older who were considering RRSO due to: 1) a family history of ovarian cancer, 2) a family history suggestive of a hereditary breast/ovarian pattern, and/or 3) the presence of a known disease-related gene mutation in the family. Of the 92 women who were contacted, 75 (82%) participated. Demographic data were available for 14 of the 17 women who declined to participate. Analyses indicated no differences between participants and decliners in mean age, level of education, or marital status. Participants were identified as either having surgery in the immediate future (N = 38) or choosing to continue with screening (N = 37). All participants provided informed consent prior to enrolling in the study.

Study measures were collected at four time points: baseline (enrollment in the study) and one month, six months and twelve months after surgery (or 1-month, 6-months, and 12-months post-baseline for women in the screening group). Surveys were mailed or given directly to participants with return postage-paid envelopes provided. Response rates at follow-up points were generally high. At 1-month, the response rate was 95% (71/75). At 6-months, the response rate was 87% (65/75), and at 12-months, the response rate was 84% (63/75).

Measures

Demographic variables including age, race/ethnicity, marital status, and education level were assessed. Information regarding menopausal status, genetic testing status, and prior cancer history was obtained from participants’ FRAP records.

Quality of life (QOL) was assessed using the Medical Outcomes Survey (MOS) Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) [20, 21], which assesses 8 domains: physical functioning, role limitations due to physical problems, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, and mental health. In addition, the two component scale values were computed to summarize physical well-being (the Physical Components Score or PCS) and mental well-being (Mental Components Score or MCS). Participants also completed a 43-item symptom checklist that was originally developed for the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) [22]. The symptom checklist includes various menopausal-related symptoms (e.g., hot flashes, vaginal dryness) and has been widely used in cancer patient and at-risk populations [23–25].

Sexual functioning was assessed using the Sexual Activity Questionnaire [26], which assesses three aspects of sexual functioning (i.e. pleasure, discomfort, and habit). Women also provided ratings of body image using a modified version of the Body Parts Satisfaction Scale (BPSS) [27], on which women were asked to rate their level of satisfaction with specific body parts (e.g., breasts, thighs, waist, etc.). The BPSS provides a unidimensional measure of body satisfaction that is represented by a total score that is the mean of all responses.

Finally, depressive symptoms were assessed using the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale (CES-D), which is a 20-item self-report index of depressive symptoms [28]. The CES-D has high reliability and internal validity and has been widely used [14, 29, 30].

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS 9.1. Univariate analyses were performed to examine potential differences between the two groups (surgery vs. screening) on baseline demographic and outcome variables, using chi-square tests and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Next, multivariable analyses were conducted to examine changes in QOL, sexual functioning, symptoms, body image, and depressive symptoms over time across the two groups using generalized estimating equations (GEE). These models included patient group (surgery vs. screening) and assessment time point (baseline, 1-, 6-, and 12-months), controlling for relevant demographic and background variables (i.e. age, education level, marital status, and genetic testing result).

For missing data, no data imputation was carried out because we could not presume that data were missing at random. Rather, for each measure, analyses were carried out using every observation at each time point with complete data. In other words, missing data at each time point were excluded from the multivariable analyses. In this manner, patients with partial data were still included in the model.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the study sample

Study participants were predominantly non-Hispanic white, well educated, and married (see Table 1). Overall, no differences in demographic variables or menopausal status were observed between women choosing RRSO compared to women who opted for screening. With regards to genetic testing status, a greater percentage of women who had not undergone testing opted for screening (32.4%) compared to surgery (10.5%), although this difference did not reach statistical significance, χ2(2) = 5.36, p < 0.07. In addition, chi-square analyses indicated that a greater proportion of women in the surgery group had had breast cancer (28.9%) compared to the screening group (10.8%), χ2(1) = 3.85, p = 0.05. In general, women with prior breast cancer did not differ significantly from women who had not had breast cancer on their levels of overall physical well-being or mental well-being or on any of the QOL subscales at any of the assessment time points, with the exception of baseline physical functioning. Specifically, women with a prior breast cancer reported significantly greater (i.e. better) physical functioning (M = 93.25, SD = 17.59) compared to women who had not had breast cancer (M = 85.81, SD = 20.95), Wilcoxon test p < 0.05. Therefore, prior cancer history was included as a covariate in the subsequent multivariable model of physical functioning.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Participants

| Surgery (N = 38) | Screening (N = 37) | U.S. Population Norms | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) | 46.0 (6.99) | 47.0 (10.29) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 97.4% | 94.6% | |

| Education | |||

| High school/GED | 18.9% | 20.0% | |

| College/post-graduate | 81.1% | 80.0% | |

| Marital status | |||

| Never married | 10.8% | 14.3% | |

| Married/Living with partner | 81.1% | 68.6% | |

| Divorced/Separated | 8.1% | 17.1% | |

| Genetic test status | |||

| Positive test result | 39.5% | 29.7% | |

| No mutation found | 50.0% | 37.8% | |

| Did not undergo testing | 10.5% | 32.4% | |

| Postmenopausal | 27.0% | 25.0% | |

| Previous breast cancer* | 28.9% | 10.8% | |

| Quality of life | |||

| PCS | 53.88 (8.75) | 51.10 (11.26) | |

| MCS | 49.39 (10.30) | 47.51 (12.01) | |

| Physical functioning | 91.15 (14.24) | 83.91 (24.44) | 81.47 (24.60)a |

| Role-Physical | 82.03 (33.14) | 83.57 (33.73) | 77.77 (36.20)a |

| Bodily pain | 80.31 (22.51) | 73.31 (28.15) | 73.59 (24.25)a |

| Vitality | 57.26 (19.95) | 51.32 (23.91) | 58.43 (21.47)a |

| Social functioning | 90.23 (19.24) | 85.66 (22.85) | 81.54 (23.74)a |

| Role-Emotional | 81.25 (33.00) | 75.71 (39.05) | 79.47 (34.43)a |

| Mental health | 77.16 (16.4) | 71.06 (19.27) | 73.25 (18.68)a |

| General health perception | 76.41 (19.14) | 68.2 (24.78) | 70.61 (21.50)a |

| Average # of symptoms (SD) | 10.33 (5.96) | 9.97 (4.79) | |

| Sexual functioning | |||

| Pain/discomfort* | 4.45 (2.15) | 3.28 (1.79) | |

| Satisfaction/pleasure | 14.75 (3.35) | 15.30 (3.78) | |

| Body image | 3.16 (0.74) | 3.03 (1.04) | |

| Depressive symptoms (SD) | 8.52 (9.93) | 11.51 (10.28) | 9.25 (8.58)b |

No differences were observed on baseline QOL, body image, or depressive symptoms between the two groups. In addition, the two groups reported similar levels of satisfaction with sexual activity at baseline; however, women in the surgery group reported significantly more discomfort during sexual intercourse compared to women in the screening group, F = 5.10, p < 0.03.

At baseline, women reported experiencing about 10 symptoms (SD = 5.38). The most commonly reported symptoms are presented in Table 2. No difference was observed in the total number of symptoms reported at baseline across the two groups; however, at baseline, a greater proportion of women in the surgery group reported experiencing hot flashes (50.0%) and vaginal dryness (39.5%) compared to women in the screening group (27.0% and 10.8%, respectively), both χ2-values > 5.20, ps < 0.03.

Table 2.

The percentage of women reporting specific symptoms at each time point

| Baseline | 1-Month | 6-Months | 12-Months | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery | Screening | Surgery | Screening | Surgery | Screening | Surgery | Screening | |

| Headache | 57.9% | 51.4% | 50.0% | 62.2% | 50.0% | 48.6% | 57.9% | 40.5% |

| Hot flashes | 50.0% | 27.0% | 65.8% | 18.9% | 55.3% | 16.2% | 55.3% | 29.7% |

| General aches | 47.4% | 45.9% | 52.6% | 45.9% | 39.5% | 43.2% | 50.0% | 37.8% |

| Joint pain | 44.7% | 37.8% | 36.8% | 37.8% | 42.1% | 35.1% | 47.4% | 29.7% |

| Early awakening | 44.7% | 40.5% | 39.5% | 27.0% | 39.5% | 24.3% | 36.8% | 27.0% |

| Unhappy with appearance | 42.1% | 67.6% | 55.3% | 62.2% | 44.7% | 45.9% | 65.8% | 48.6% |

| Forgetfulness | 42.1% | 35.1% | 52.6% | 35.1% | 57.9% | 24.3% | 62.9% | 31.0% |

| Short-tempered | 42.1% | 40.5% | 47.4% | 40.5% | 42.1% | 27.0% | 50.0% | 29.7% |

| Vaginal dryness | 39.5% | 10.8% | 28.9% | 10.8% | 44.7% | 10.8% | 52.6% | 10.8% |

| Vaginal discomfort | 34.2% | 24.3% | 26.3% | 18.9% | 15.8% | 13.5% | 7.9% | 24.3% |

Information about RRSO surgical procedures was available for 25 of the 38 women in the surgery group. (The remaining 13 women underwent RRSO at other area institutions, and therefore, complete information regarding their surgical procedures was not available for these women). Of the 25 women with complete information, 14 women underwent total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (TAH/BSO), 2 women had TAH with unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (one ovary having been removed previously), 2 women had laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy (LAVH) with BSO, 4 women had abdominal BSO, and 3 women had laparoscopic BSO. In addition, two of the women who had TAH with BSO also underwent uterosacral colpopexy during their surgeries.

Quality of life and symptoms

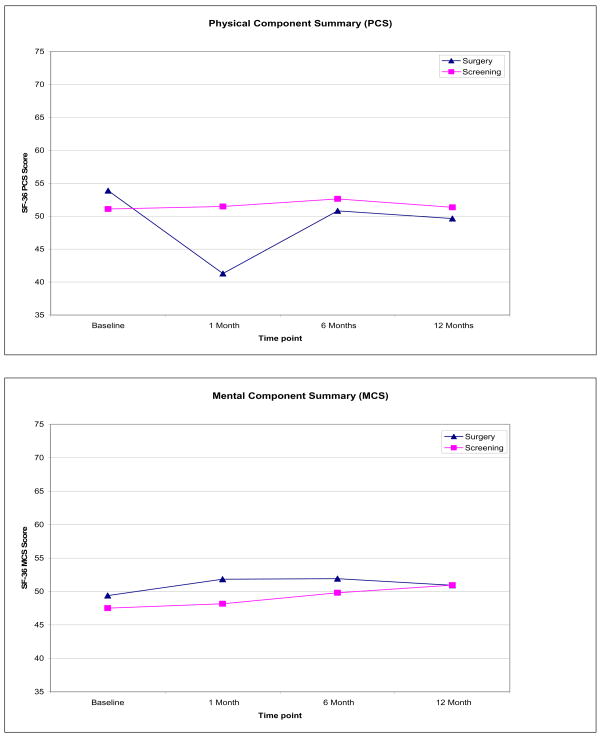

As depicted in Figure 1, a group (surgery vs. screening) by time interaction was observed for physical well-being (PCS), β = 10.76, p < 0.001. Specifically, the surgery group reported significantly lower mean PCS scores at 1-month follow-up compared to baseline (β = −5.61, p < 0.02), whereas no such deficit was observed in the screening group. In addition, a significant main effect of age (dichotomized as a categorical variable,≤45 years vs. > 45 years) was observed, indicating that older women (>45) had lower mean PCS scores (M =46.74, SD = 11.46) compared to younger women (M = 52.93, SD = 7.55), β = −5.30, p < 0.001.

Figure 1.

Mean PCS and MCS scores by group at each time point

For the mental component summary (MCS) score, significant main effects were observed for age and genetic testing results. Older women reported higher MCS scores (M = 52.25, SD = 10.49) compared to younger women (M = 48.25, SD = 10.80), β = 5.18, p < 0.01. Women who chose not to undergo genetic testing had lower mean MCS scores (M = 47.02, SD = 12.45) than women who tested positive for a BRCA1/2 mutation (M = 49.37, SD = 9.85) or who received results indicating no known mutation was found (M = 51.22, SD = 11.38), β = −5.58, p < 0.01. No differences in MCS were observed between the two groups or over time.

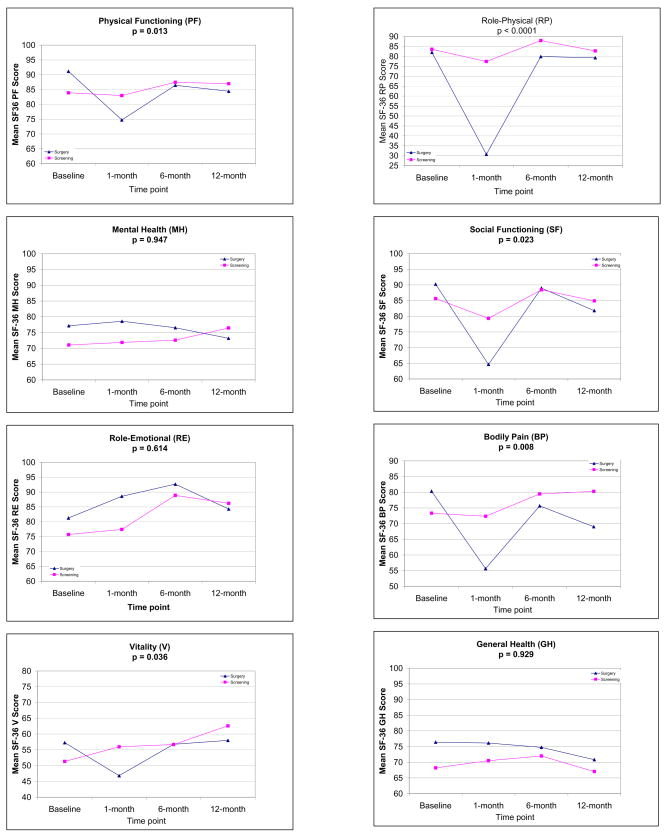

With respect to the SF-36 subscales, significant interactions between group and time were observed for five subscales: Physical Functioning, Role-Physical, Bodily Pain, Vitality, and Social Functioning. On each of these subscales, women in the surgery group reported poorer physical functioning, worse physical role limitations, worse pain, less vitality, and poorer social functioning at 1-month assessment compared to baseline, whereas women in the screening group reported no significant decrements in these domains over time (see Figure 2). Prior breast cancer history was no longer associated with physical functioning in the multivariable model, p > 0.57.

Figure 2.

Mean SF-36 subscale scores by group at each time point.

Importantly, decrements in QOL reported at the 1-month assessment were no longer apparent by 6-month assessment, and recovery of QOL was maintained at 12 months with one exception. Women in the surgery group had significantly lower scores on the bodily pain subscale (indicating greater pain) at 12-month assessment (M = 69.00, SD = 22.35) compared to baseline (M = 80.31, SD = 22.51), β = −10.92, p = 0.05, whereas no difference in pain scores were observed in the screening group over time.

With respect to symptoms reported (see Table 2), there was a significant main effect of group for hot flashes, β = −1.16, p < 0.03. Controlling for age, women in the surgery group were more likely to report experiencing hot flashes than women in the screening group across all time points. Similarly, a significant main effect of group was observed for vaginal dryness, β = −1.82, p < 0.01, whereby women in the surgery group were more likely to report vaginal dryness than women in the screening group.

For the symptom of vaginal discomfort, main effects of time were observed such that fewer women reported vaginal discomfort at 6-month, β = −1.12, p < 0.05, and 12-month assessments, β = −2.06, p < 0.01, compared to baseline. These main effects were qualified by a significant group by time interaction effect, β = 2.29, p < 0.02. Specifically, at 12-month follow-up, the proportion of women in the surgery group who reported vaginal discomfort had decreased to a significantly greater extent (34% at baseline to 8% at 12-month follow-up) compared to women in the screening group (which remained at 24% from baseline to 12-month follow-up). Finally, older age was significantly associated with greater reporting of joint pain, early awakening, being unhappy with one’s appearance, and being short-tempered; however, neither main effects of group or time point nor any interaction effects were observed for these symptoms.

Sexual functioning

Overall, women in the surgery group reported greater discomfort during sexual intercourse (M = 4.45, SD = 2.15) than women in the screening group (M = 3.28, SD = 1.79), β = 1.15, p < .05. In addition, older women and women in the surgery group reported significantly less pleasure during sexual activity compared to younger women (β = −1.72, p < 0.02) and women in the screening group (β = −2.36, p < 0.03), respectively. However, these main effects were qualified by a Group × Age interaction (β = 4.82, p < .0001). In the surgery group, older women reported greater satisfaction (M = 15.27, SD = 2.84) than did younger women (M = 13.69, SD = 4.09), β = 1.58, p < 0.05. In contrast, in the surveillance group, younger women reported greater satisfaction with sexual activity (16.43, SD = 3.15) compared to older women (13.97, SD = 4.49), β = 3.59, p < 0.0001.

With respect to frequency of sexual activity, there was a significant group by time interaction, β = −0.61, p < 0.01. Women in the surgery group reported reduced frequency of sexual activity at 1-month compared to baseline (β = 0.51, p < 0.01), whereas no change in frequency was reported by women in the screening group. Table 3 presents the percentage of women reporting increased, decreased, or usual levels of sexual activity at each time point. At 1-month post-surgery, 66.7% of women who had RRSO reported decreased sexual activity over the past month. However, at subsequent time points, the percentage of women in the surgery group who reported decreased frequency of sexual activity declined over time, thereby indicating a gradual return to usual levels. These data suggest that the decrease in sexual activity reported by women in the surgery group reflects a temporary, and not permanent, alteration in the monthly frequency of sexual activities.

Table 3.

The percentage of women reporting usual, increased, or decreased sexual activity

| Baseline | 1-Month | 6-Months | 12-Months | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery | Screening | Surgery | Screening | Surgery | Screening | Surgery | Screening | |

| Less than usual | 24.2% | 23.3% | 66.7% | 20.8% | 40.7% | 36.4% | 39.3% | 29.2% |

| About the same | 63.6% | 76.7% | 33.3% | 70.8% | 55.6% | 54.5% | 46.4% | 58.3% |

| Somewhat more | 12.1% | 0% | 0% | 8.3% | 3.7% | 9.1% | 7.1% | 12.5% |

| Much more | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 7.1% | 0% |

Psychosocial functioning: Body image and depressive symptoms

Older women were less satisfied with their overall body image than younger women (β = −3.82, p < .01), but no other significant differences in body image were observed over time or between the surgery and screening groups. On the other hand, older women reported fewer depressive symptoms (M = 8.24, SD = 8.26) compared to younger women (M = 10.54, SD = 10.40), β = −4.30, p < 0.01. Again, no significant differences in depressive symptoms were observed over time or between the surgery and screening groups.

Discussion

In this prospective study, women undergoing RRSO were more likely to report short-term deficits in physical functioning and sexual functioning compared to women in the screening group. However, by 12-month follow-up, ratings of QOL were similar between the two groups. These findings are consistent with data from prior retrospective studies that reported comparable levels of QOL between women who had RRSO and those who chose screening [16].

As would be expected, decrements in QOL following surgery were observed in domains related to physical functioning, physical role limitations, pain, and vitality. Because social interactions are likely to be more limited during the recuperative period immediately following surgery, this may account for the decline in social functioning observed at 1-month post-surgery. Across most subdomains of QOL, recovery to baseline levels was observed by 6-months post-surgery. However, for bodily pain, women who had had RRSO continued to report greater pain at 12-month follow-up. The reasons for this finding are unclear, as women in the surgery group were not more likely to report symptoms (e.g., joint pain or general aches) than women in the screening group.

Overall, a greater proportion of women who had RRSO reported symptoms of estrogen deprivation (i.e. hot flashes, vaginal dryness) compared to women in the screening group. Although this would be expected following surgically-induced menopause, it should be noted that these differences were already evident at baseline (prior to surgery). One possible interpretation is that, even though the two groups were similar in age, women who chose surgery were already in a peri-menopausal state of diminished production of estrogen. Although speculative, it is possible that women who perceive that they are imminently approaching menopause are more accepting of surgically-induced menopause, and therefore, are more likely to commit to having RRSO.

In addition, our findings indicated that symptoms of vaginal discomfort decreased over time, notably among women who had had RRSO. This gradual decrease in the experience of vaginal discomfort may reflect better awareness and coping with post-menopausal symptoms among women who are dealing with the physical side effects of surgically-induced menopause. That is, over time, women who had RRSO may have learned how to better manage these symptoms so as to reduce discomfort, perhaps through seeking information or advice from their physicians, healthcare providers, the internet, or other women.

Although the two groups differed in their symptom experience (particularly in those symptoms associated with estrogen deprivation), there were few differences in quality of life between the two groups at long-term (i.e. 6-month and 12-month) follow-up. It has been noted that experiencing more symptoms does not necessarily translate to lower quality of life [31], and that the two concepts (symptoms and QOL) represent distinctive entities and are not interchangeable, which is reflected by the generally modest overlap between symptoms and QOL reported in most studies [32]. A study of symptoms and QOL in breast cancer patients reported that fatigue was the strongest predictor of QOL, whereas other symptoms (e.g., pain, nausea and/or vomiting, breast symptoms, systemic therapy side effects, and arm symptoms) explained very little of the variance in QOL scores [32]. Hence, in the context of the present study, the finding that QOL did not differ between the two groups even though the surgical group experienced greater symptoms may be attributed, in part, to the fact that the most commonly reported symptoms by women in our study were not ones found to be strongly associated with QOL in other previous studies. Finally, it has been proposed that patients likely “adapt” to any physical changes that occur over time, so that QOL tends to remain stable. This concept has been termed “response shift,” which is defined as a recalibration or change in one’s internal standards of QOL [33]. Whether women who undergo RRSO experience a response shift in QOL following surgery remains to be investigated.

Similar to previous studies that have reported sexual dysfunction following RRSO [15–17], women in the surgery group reported greater discomfort and less satisfaction with sexual intercourse compared to women in the screening group. However, our pattern of findings indicates a more complex story. Specifically, our data suggest that sexual satisfaction in older women is not as adversely affected by surgery, unlike in younger women. For older women who may have already been experiencing menopausal symptoms pre-surgery (e.g., vaginal dryness), the post-surgical manifestations of menopause may not be so dramatically different or require as considerable adjustment after surgery. Indeed, this is consistent with a previous study in which postmenopausal women reported no adverse effects of RRSO on their libido [11]. For younger women, however, coping with surgically-induced menopause may require greater adjustment [34, 35], and thus, the physical and psychological consequences of menopause may have a greater negative impact on sexual functioning [36].

In general, older women had fewer depressive symptoms and greater psychosocial functioning (i.e. higher MCS scores) than younger women. These data are consistent with previous studies of breast cancer patients that have reported older age to be positively associated with psychosocial adjustment [37–39]. Previous studies indicate that younger women may have worse symptom experiences [39]; as such, the transition to menopause can be associated with decreases in QOL and greater emotional distress [40]. In addition, it has been proposed that younger women may have fewer coping strategies and experience greater disruptions in their daily responsibilities compared to older women [40, 41], which could contribute to depressive symptoms and poorer psychosocial adjustment.

As one of the first studies to present prospective data on QOL over time among a sample of at-risk women who choose to undergo RRSO or serial screening, these findings may be useful for helping at-risk women make decisions about their ovarian cancer prevention options. Although there are a number of strengths of the study, including the prospective design, the cohort of two comparable groups of women with respect to demographic variables, and a longitudinal follow-up, we acknowledge several limitations of the study. First, the sample size is relatively small, although comparable to other prospective studies of this nature [19, 42]. Second, the majority of women who underwent RRSO in the present study had either abdominal BSO or concomitant abdominal hysterectomy. Given that prior studies have reported that short-term quality of life outcomes are generally higher among women undergoing laparoscopic procedures compared to total abdominal hysterectomy in the first 6 weeks following surgery [43–45], the 1-month post-surgical data may be less applicable to women who undergo laparoscopic procedures. Third, our sample was comprised of women who were predominantly non-Hispanic white and well-educated, thereby limiting the potential generalizability of these results to other ethnic/racial groups or women with fewer years of education. Fourth, because study participants were recruited from a cancer risk assessment program, the majority of women had already undergone previous cycles of screening (i.e. were not screen naïve) when they entered the study. As such, screening may be less likely to have had a negative impact on quality of life among women with a history of prior screening. On the other hand, if there was a selection bias for including participants who have previously tolerated screening well from a quality of life standpoint, then this bodes well for the surgery group, as they had levels of QOL comparable to the screening group. Finally, we acknowledge that the two groups were not equivalent with respect to prior breast cancer history. However, all women were disease-free and baseline levels of QOL did not differ between the surgery and screening groups. In other words, given that a significantly greater proportion of women in the surgery group had had breast cancer, one might expect to see lower levels of QOL in this group compared to the screening group at baseline, but this was not the case. Despite these potential limitations, the findings from the present study provide a greater understanding of how various cancer prevention options may impact on women’s physical, psychosocial, and sexual functioning over time, and how these effects may be more salient among younger women.

In sum, findings from the present study suggest that, although there are short-term decrements in specific domains of QOL following RRSO, most women recover baseline functioning within one year. However, issues regarding the potential impact of surgery on sexual functioning should be considered and weighed carefully, particularly among younger women. New data demonstrating differences in age of onset of ovarian cancer by gene affected [9], coupled with the present findings, can assist women and their health care providers in better customizing RRSO recommendations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Department of Defense (DAMD 17-00-1-0568) and the National Institutes of Health (P30 CA006927). We thank Honey Salador and the Family Risk Assessment Program staff for their assistance on this project. We acknowledge the FCCC Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Facility and the Population Studies Facility for their services.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest statement: No authors have any conflicts of interest to report for the present study.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Antoniou A, Pharoah PD, Narod S, Risch HA, Eyfjord JE, Hopper JL, Loman N, Olsson H, Johannsson O, Borg A, Pasini B, Radice P, Manoukian S, Eccles DM, Tang N, Olah E, Anton-Culver H, Warner E, Lubinski J, Gronwald J, Gorski B, Tulinius H, Thorlacius S, Eerola H, Nevanlinna H, Syrjakoski K, Kallioniemi OP, Thompson D, Evans C, Peto J, Lalloo F, Evans DG, Easton DF. Average risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations detected in case Series unselected for family history: a combined analysis of 22 studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:1117–30. doi: 10.1086/375033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NCCN Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast and Ovarian. 2007;1 available @ www.nccn.org.

- 3.Gaarenstroom KN, van der Hiel B, Tollenaar RA, Vink GR, Jansen FW, van Asperen CJ, Kenter GG. Efficacy of screening women at high risk of hereditary ovarian cancer: results of an 11-year cohort study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16 (Suppl 1):54–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hogg R, Friedlander M. Biology of epithelial ovarian cancer: implications for screening women at high genetic risk. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1315–27. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stirling D, Evans DG, Pichert G, Shenton A, Kirk EN, Rimmer S, Steel CM, Lawson S, Busby-Earle RM, Walker J, Lalloo FI, Eccles DM, Lucassen AM, Porteous ME. Screening for familial ovarian cancer: failure of current protocols to detect ovarian cancer at an early stage according to the international Federation of gynecology and obstetrics system. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5588–96. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finch A, Beiner M, Lubinski J, Lynch HT, Moller P, Rosen B, Murphy J, Ghadirian P, Friedman E, Foulkes WD, Kim-Sing C, Wagner T, Tung N, Couch F, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Ainsworth P, Daly M, Pasini B, Gershoni-Baruch R, Eng C, Olopade OI, McLennan J, Karlan B, Weitzel J, Sun P, Narod SA. Salpingo-oophorectomy and the risk of ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal cancers in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 Mutation. Jama. 2006;296:185–92. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rebbeck TR, Lynch HT, Neuhausen SL, Narod SA, Van’t Veer L, Garber JE, Evans G, Isaacs C, Daly MB, Matloff E, Olopade OI, Weber BL. Prophylactic oophorectomy in carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1616–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosen B, Kwon J, Fung Kee Fung M, Gagliardi A, Chambers A. Systematic review of management options for women with a hereditary predisposition to ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;93:280–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kauff ND, Domchek SM, Friebel TM, Robson ME, Lee J, Garber JE, Isaacs C, Evans DG, Lynch H, Eeles RA, Neuhausen SL, Daly MB, Matloff E, Blum JL, Sabbatini P, Barakat RR, Hudis C, Norton L, Offit K, Rebbeck TR. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy for the prevention of BRCA1- and BRCA2-associated breast and gynecologic cancer: a multicenter, prospective study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1331–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.9626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guillem JG, Wood WC, Moley JF, Berchuck A, Karlan BY, Mutch DG, Gagel RF, Weitzel J, Morrow M, Weber BL, Giardiello F, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Church J, Gruber S, Offit K. ASCO/SSO review of current role of risk-reducing surgery in common hereditary cancer syndromes. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4642–60. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.5260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meiser B, Tiller K, Gleeson MA, Andrews L, Robertson G, Tucker K. Psychological impact of prophylactic oophorectomy in women at increased risk for ovarian cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2000;9:496–503. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200011/12)9:6<496::aid-pon487>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hallowell N, Mackay J, Richards M, Gore M, Jacobs I. High-risk premenopausal women’s experiences of undergoing prophylactic oophorectomy: a descriptive study. Genet Test. 2004;8:148–56. doi: 10.1089/gte.2004.8.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kauff ND, Hurley KE, Hensley ML, Robson ME, Lev G, Goldfrank D, Castiel M, Brown CL, Ostroff JS, Hann LE, Offit K, Barakat RR. Ovarian carcinoma screening in women at intermediate risk: impact on quality of life and need for invasive follow-up. Cancer. 2005;104:314–20. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hensley ML, Robson ME, Kauff ND, Korytowsky B, Castiel M, Ostroff J, Hurley K, Hann LE, Colon J, Spriggs D. Pre- and postmenopausal high-risk women undergoing screening for ovarian cancer: anxiety, risk perceptions, and quality of life. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;89:440–6. doi: 10.1016/s0090-8258(03)00147-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elit L, Esplen MJ, Butler K, Narod S. Quality of life and psychosexual adjustment after prophylactic oophorectomy for a family history of ovarian cancer. Fam Cancer. 2001;1:149–56. doi: 10.1023/a:1021119405814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Madalinska JB, Hollenstein J, Bleiker E, van Beurden M, Valdimarsdottir HB, Massuger LF, Gaarenstroom KN, Mourits MJE, Verheijen RHM, van Dorst EBL, van der Putten H, van der Velden K, Boonstra H, Aaronson NK. Quality-of-life effects of prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy versus gynecologic screening among women at increased risk of hereditary Ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6890–6898. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robson M, Hensley M, Barakat R, Brown C, Chi D, Poynor E, Offit K. Quality of life in women at risk for ovarian cancer who have undergone risk-reducing oophorectomy. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;89:281–7. doi: 10.1016/s0090-8258(03)00072-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bresser PJC, Seynaeve C, Van Gool AR, Niermeijer MF, Duivenvoorden HJ, van Dooren S, van Geel AN, Menke-Pluijmers MB, Klijn JGM, Tibben A. The course of distress in women at increased risk of breast and ovarian cancer due to an (identified) genetic susceptibility who opt for prophylactic mastectomy and/or salpingo-oophorectomy. European Journal of Cancer. 2007;43:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tiller K, Meiser B, Butow P, Clifton M, Thewes B, Friedlander M, Tucker K. Psychological impact of prophylactic oophorectomy in women at increased risk of developing ovarian cancer: a prospective study. Gynecologic Oncology. 2002;86:212–219. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2002.6737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ware JE. SF-36 Health Survey Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston: The Health Institute; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) Med Care. 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ganz PA, Day R, Ware JE, Jr, Redmond C, Fisher B. Base-line quality-of-life assessment in the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Breast Cancer Prevention Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:1372–82. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.18.1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Day R, Ganz PA, Costantino JP, Cronin WM, Wickerham DL, Fisher B. Health-related quality of life and tamoxifen in breast cancer prevention: a report from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 Study. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2659. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.9.2659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ganz PA, Rowland JH, Desmond K, Meyerowitz BE, Wyatt GE. Life after breast cancer: understanding women’s health-related quality of life and sexual functioning. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:501–14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.2.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mortimer JE, Boucher L, Baty J, Knapp DL, Ryan E, Rowland JH. Effect of tamoxifen on sexual functioning in patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1488–92. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.5.1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thirlaway K, Fallowfield L, Cuzick J. The Sexual Activity Questionnaire: a measure of women’s sexual functioning. Qual Life Res. 1996;5:81–90. doi: 10.1007/BF00435972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berscheid E, Walster E, Bohrnstedt G. The happy American body: A survey report. Psychology Today. 1973;7:119–131. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tiffen J, Sharp L, O’Toole C. Depressive symptoms prescreening and postscreening among returning participants in an ovarian cancer early detection program. Cancer Nurs. 2005;28:325–30. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200507000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vadaparampil ST, Ropka M, Stefanek ME. Measurement of psychological factors associated with genetic testing for hereditary breast, ovarian and colon cancers. Fam Cancer. 2005;4:195–206. doi: 10.1007/s10689-004-1446-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Finlayson TL, Moyer CA, Sonnad SS. Assessing symptoms, disease severity, and quality of life in the clinical context: a theoretical framework. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10:336–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arndt V, Stegmaier C, Ziegler H, Brenner H. A population-based study of the impact of specific symptoms on quality of life in women with breast cancer 1 year after diagnosis. Cancer. 2006;107:2496–2503. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sprangers MAG, Schwartz CE. The challenge of response shift for quality-of-life-based clinical oncology research. Ann Oncol. 1999;10:747–749. doi: 10.1023/a:1008305523548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knobf MT. Carrying on: the experience of premature menopause in women with early stage breast cancer. Nurs Res. 2002;51:9–17. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200201000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knobf MT. “Coming to grips” with chemotherapy-induced premature menopause. Health Care Women Int. 2008;29:384–99. doi: 10.1080/07399330701876562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Graziottin A, Basson R. Sexual dysfunction in women with premature menopause. Menopause. 2004;11:766–77. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000139926.02689.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ganz PA, Guadagnoli E, Landrum MB, Lash TL, Rakowski W, Silliman RA. Breast cancer in older women: quality of life and psychosocial adjustment in the 15 months after diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4027–33. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hopwood P, Haviland J, Mills J, Sumo G, J MB. The impact of age and clinical factors on quality of life in early breast cancer: an analysis of 2208 women recruited to the UK START Trial (Standardisation of Breast Radiotherapy Trial) Breast. 2007;16:241–51. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Janz NK, Mujahid M, Chung LK, Lantz PM, Hawley ST, Morrow M, Schwartz K, Katz SJ. Symptom experience and quality of life of women following breast cancer treatment. Journal of Women’s Health (15409996) 2007;16:1348–1361. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ganz PA, Greendale GA, Petersen L, Kahn B, Bower JE. Breast cancer in younger women: reproductive and late health effects of treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4184–93. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mor V, Malin M, Allen S. Age differences in the psychosocial problems encountered by breast cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1994:191–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bresser PJC, Van Gool AR, Seynaeve C, Duivenvoorden HJ, Niermeijer MF, van Geel AN, Menke M, Klijn JGM, Tibben A. Who is prone to high levels of distress after prophylactic mastectomy and/or salpingo-ovariectomy? Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1641–1645. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garry R, Fountain J, Brown J, Manca A, Mason S, Sculpher M, Napp V, Bridgman S, Gray J, Lilford R. EVALUATE hysterectomy trial: a multicentre randomised trial comparing abdominal, vaginal and laparoscopic methods of hysterectomy. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8:1–154. doi: 10.3310/hta8260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kluivers KB, Hendriks JC, Mol BW, Bongers MY, Bremer GL, de Vet HC, Vierhout ME, Brolmann HA. Quality of life and surgical outcome after total laparoscopic hysterectomy versus total abdominal hysterectomy for benign disease: a randomized, controlled trial. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:145–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kluivers KB, Johnson NP, Chien P, Vierhout ME, Bongers M, Mol BW. Comparison of laparoscopic and abdominal hysterectomy in terms of quality of life: a systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2008;136:3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]