Abstract

The acute inflammatory response involves neutrophils wherein recognition of bacterial products, such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), activates intracellular signaling pathways. We have shown that the mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) c-Jun NH2 terminal kinase (JNK) is activated by LPS in neutrophils and plays a critical role in monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1 expression and actin assembly. As the Tec family kinases are expressed in neutrophils and regulate activation of the MAPKs in other cell systems, we hypothesized that the Tec kinases are an upstream component of the signaling pathway leading to LPS-induced MAPKs activation in neutrophils. Herein, we show that the Tec kinases are activated in LPS stimulated human neutrophils and that inhibition of the Tec kinases, with leflunomide metabolite analog (LFM-A13), decreased LPS-induced JNK, but not p38, activity. Furthermore, LPS-induced actin polymerization as well as MCP-1, tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-6, and interleukin-1β expression are dependent on Tec kinase activity.

Keywords: MAP kinase, MCP-1, cell signaling, lipopolysaccarhide, neutrophil

INTRODUCTION

Polymorphonuclear leukocytes (neutrophils) migrate to sites of infection, where bacterial products such as LPS trigger the activation of signaling cascades resulting in effector functions that lead ultimately to eradication of the invading microorganisms. We previously have shown that the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) p38 [1] and JNK [2] are activated by LPS in human neutrophils, with each regulating specific effector functions. Whereas p38 regulates activation of nuclear factor (NF)-κB [3], the expression of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α [3], and IL-8 [4], as well as cell adhesion [3] after LPS stimulation, JNK regulates LPS-induced actin polymerization and the expression of MCP-1 and TNF-α [2]. In addition, we showed that spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) were upstream in the pathway leading to LPS-induced JNK activation in neutrophils [2]. The lack of complete inhibition of JNK activation with either Syk or PI3K inhibition, however, suggested the presence of additional signaling pathways that lead to JNK activation after exposure to LPS [2]. Recently the Tec kinases were shown to be present in human neutrophils and have been suggested to regulate JNK and p38 activity in other cell systems. Accordingly, we hypothesized that they may be involved in the LPS-induced signaling pathway leading to MAPK activation in neutrophils.

The Tec kinases are a family of nonreceptor tyrosine kinases that includes Tec, Btk, Itk, Bmx, and Txk. They reside in an inactive form in the cytoplasm, are translocated to the membrane fraction upon cell stimulation, wherein they are activated by phosphorylation, and initiate downstream signaling cascades [5–7]. The Tec kinases play an important role in both the innate and adaptive immune systems. Naturally occurring mutations in Btk result in X-linked agammaglobulinemia (XLA), a clinical immunodeficiency syndrome characterized by a virtual absence of circulating mature B cells and drastically reduced levels of immunoglobulins [7]. In addition, immature B cells from X-linked immunodeficiency (Xid) mice, which express an inactive form of Btk, do not respond to LPS normally [8] with Btk-deficient mice showing increased mortality after LPS exposure [9]. In the innate immune system, LPS stimulated macrophages activate both Btk and Tec [10], with Btk co-immunoprecipitating with Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 and some of its adapter molecules [11]. Similarly the Tec kinases play a role in LPS-induced cytokine production and MAPK activation in mononuclear cells. Mononuclear cells from XLA patients produce decreased levels of TNF-α [10] and IL-1β [12] when exposed to LPS and LPS stimulated macrophages from Btk-deficient mice display impaired TNF-α, IL-1β [13], and IL-10 [14] production, impaired AP-1 [14] and NF-κB activation [11, 14, 15], as well as diminished reactive oxygen intermediates (ROI) release [16, 17]. In contrast, although the Tec kinases are suggested to regulate the LPS response in macrophages, the role of the Tec kinases in the response of neutrophils to LPS, cells critical to the innate immune system, has not previously been examined.

One pathway through which the Tec kinases have been suggested to regulate their effects on cells of the innate and adaptive immune systems is via activation of the MAPK. In B cells, Btk activity is critical for MAPK activation as Btk regulates both JNK [18, 19] and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) [19] activation after B cell receptor (BCR) cross-linking as well as Gαq-mediated p38 activation [20]. Similarly, in response to T cell receptor (TCR) stimulation, T cells deficient in the Tec kinases display impaired activation of the MAPKs [21] as well as the activator protein-1 (AP-1) family of transcription factors [5], which are dependent on ERK and JNK activation. Finally in mononuclear cells, LPS-induced TNF-α synthesis has been suggested to be regulated by Btk through a p38-dependent pathway [12].

Recently, the Tec kinases Tec and Btk were shown to be expressed and functional in human neutrophils [22]. Tec was activated upon stimulation with fMLP [22] or upon crosslinking of the FcγRIIIB receptor [23]. Inhibition of the Tec kinases downregulated fMLP-induced superoxide production, adhesion, and chemotaxis through its effects on p38 and ERK activation [24] and inhibited intracellular calcium mobilization, phosphorylation of phospholipase C (PLC) γ2, and degranulation after FcγRIIIB receptor crosslinking [23]. Since the Tec kinases are critical components of LPS-induced signaling pathways in macrophages and regulate the functional response after exposure to fMLP or upon FcγRIIIB receptor crosslinking in neutrophils, we investigated the role of the Tec kinases in LPS-induced human neutrophil signaling. Specifically, as the Tec kinases regulate MAPK activity in other cell types, and LPS activates p38 and JNK in human neutrophils, we asked whether MAPK activation in LPS-stimulated human neutrophils is dependent on Tec kinase activity and if so if the Tec kinases regulate LPS-induced actin assembly and cytokine expression. We show here that both Tec and Btk are activated in human neutrophils stimulated with LPS, that Tec kinases are upstream in the LPS-induced pathway regulating JNK, but not p38, activity, and that actin assembly and cytokine production in LPS-stimulated human neutrophils is dependent on activation of the Tec kinases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

All reagents and plasticware used in these experiments were endotoxin-free. Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), sodium orthovanadate, aprotinin, leupeptin, sodium fluoride, Protein A-Sepharose, Triton X-100, 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane, β-glycerophosphate, p-nitrophenyl phosphate, dithiothreitol, sodium pyrophosphate, and RedTaq polymerase were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). LPS (E. coli 0111:B4) was from List Biological Laboratories (Campbell, CA). TRIzol, Moloney murine leukemia virus-reverse transcriptase, NBD-phallacidin, and rhodamine phalloidin were purchased from Invitrogen (Grand Island, NY). LFM-A13, LFM-A11, and the JNK inhibitor II (SP600125) were from Calbiochem Biochemicals (La Jolla, CA). Antibodies to JNK-1 (C-17) and Tec (M20) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). The Btk antibody was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). The anti-P-Tyr antibody (4G10) and anti-P-Tyr (4G10) agarose conjugate were from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY). The substrate c-Jun1–79 was generated as previously described [25].

Human Neutrophil Isolation

Human neutrophils were isolated from healthy donors as previously described (26), a method which achieves >98% cell viability as assessed by trypan blue staining and yields < 5% contaminating monocytes. After isolation, neutrophils were resuspended at 20 × 106/ml in Krebs-Ringers phosphate buffer with 0.2% dextrose (KRPD) at pH 7.2 and 1% heat-inactivated platelet poor plasma (HIPPP) with or without protease inhibitors (leupeptin 10 μg/ml, aprotinin 10 μg/ml, and PMSF 10 μg/ml) or in RPMI 1640 (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD) with 1% HEPES and 1% HIPPP, where indicated.

Cell Membrane Isolation

Neutrophils were resuspended in complete KRPD supplemented with aprotinin (10 μg/ml), leupeptin (10 μg/ml), and 1% HIPPP and incubated at 37°C under non-suspended conditions for 55 minutes as previously described [2, 25]. Cells were stimulated with LPS (100 ng/ml) for various lengths of time. At the end of the stimulation period, PMSF (2.5 mM) and orthovanadate (1 mM) were quickly added and cells were lysed by sonication for 20 seconds (SLPt Sonifier, Branson Ultrasonics, Danbury, CT). Membrane fractions were prepared from cell lysates as previously described [22]. Proteins were separated on an 8% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, transferred to nitrocellulose, and immunoblotted for Tec.

Immunoprecipitation

Neutrophils were resuspended in complete KRPD with 1% HIPPP and protease inhibitors and incubated under non-suspended conditions at 37°C for 55 minutes. In experiments examining the role of the Tec kinases in LPS-induced JNK activation, neutrophils were pre-treated with LFM-A13 (25 or 100 μM), LFM-A11 (25 or 100 μM), or DMSO (0.1%) for 55 minutes. The cells were then stimulated with LPS (100 ng/ml) or left unstimulated at 37°C for the indicated lengths of time. After stimulation, the cells were centrifuged (15,000 RPM, 30 seconds) and lysed in 500 μl of ice-cold JNK lysis buffer as previously described [2, 25] for JNK immunoprecipitation or native lysis buffer as previously described [22] for Tec immunoprecipitation. Cell lysates were centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4 °C and the lysate supernatants were then pre-cleared with Protein-A or G Sepharose beads. To the lysates 2 μg of either anti-JNK1 antibody or anti-Tec antibody along with 20 μl of Protein-A-Sepharose, or 10 μl of the anti-P-Tyr agarose conjugate, was added followed by incubation for 2 hours at 4°C with rotation. After incubation, the beads were collected and washed three times in native lysis buffer for experiments examining activation of the Tec kinases. After washing the beads, 2x Laemmli sample buffer was added, samples were boiled at 100°C for 8 minutes, and proteins were separated on 8–10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels by electrophoresis. After transfer to nitrocellulose, immunoblotting for P-Tyr, Tec, or Btk was performed.

JNK Kinase Assay

After immunoprecipitation of JNK-1, the beads were washed once in JNK lysis buffer and twice in JNK kinase buffer (20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 20 mM β-glycerophosphate, 10 mM p-nitrophenyl phosphate, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 50 mM sodium orthovanadate), and a JNK kinase assay was performed as previously described [2, 25].

Phosphorylated p38 ELISA

Neutrophils were resuspended in complete KRPD with 1% HIPPP and protease and phosphatase inhibitors, aliquoted into microcentrifuge tubes, and then incubated with LFM-A13 (25 or 100 μM), LFM-A11 (25 or 100 μM), or DMSO (0.1%) for 55 minutes at 37°C with rotation. The cells were then stimulated with LPS (100 ng/ml) for the indicated times or left unstimulated. At each time point, 25 μl of cells were removed and added to 75 μl of ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES (pH 7.6), 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, and 1% Triton X-100), vortexed briefly, and snap frozen in an EtOH/dry ice bath, and stored at −20°C until assayed. Concentrations of phospho-p38 were measured using a phospho-p38 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (BioSource International, Camarillo, CA) per the manufacturer’s instructions.

RT-PCR and ELISAs

Neutrophils were resuspended in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 1% HIPPP and 1% HEPES, and incubated under nonsuspended conditions at 37°C with LFM-A13 (25 or 100 μM), LFM-A11 (25 or 100 μM), SP600125 (2–10 μM), or DMSO (0.1%) for 55 minutes. Cells were then stimulated with LPS (100 ng/ml) for 4 hours. RNA extraction and RT-PCR from the cell pellet was performed as previously described [2]. PCR primers utilized were as previously described [2] except for IL-6: 5′-AAAGAGGCACTGGCAGAAAA-3′, 5′-CCTTAAAGCTGCGCAGAATG-3′; and IL-1β: 5′-GCTGAGGAAGATGCTGGTTC-3′, 5′-AGTTATATCCTGGCCGCCTT-3′. Concentrations of MCP-1, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β in the cell culture supernatants were determined by ELISA (ELISA Tech, Aurora, CO) per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Actin polymerization and localization

Human neutrophils were resuspended in KRPD with 1% HIPPP and incubated with LFM-A13 (25 or 100 μM), LFM-A11 (25 or 100 μM), or DMSO (0.1%) for 40 minutes under nonsuspended conditions. Cells were then stimulated with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 40 minutes, and actin polymerization and localization were assessed as previously described [27].

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as means ± S.E.M. Multiple comparisons were performed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey (post hoc) test for determination of differences between groups. Statistical analysis was also performed by Student’s paired t test where indicated. A p value less than 0.05 was considered significant. GraphPad PRISM software (San Diego, CA) was used for all statistical calculations.

RESULTS

LPS induces both Tec and Btk phosphorylation and the translocation of Tec to the plasma membrane

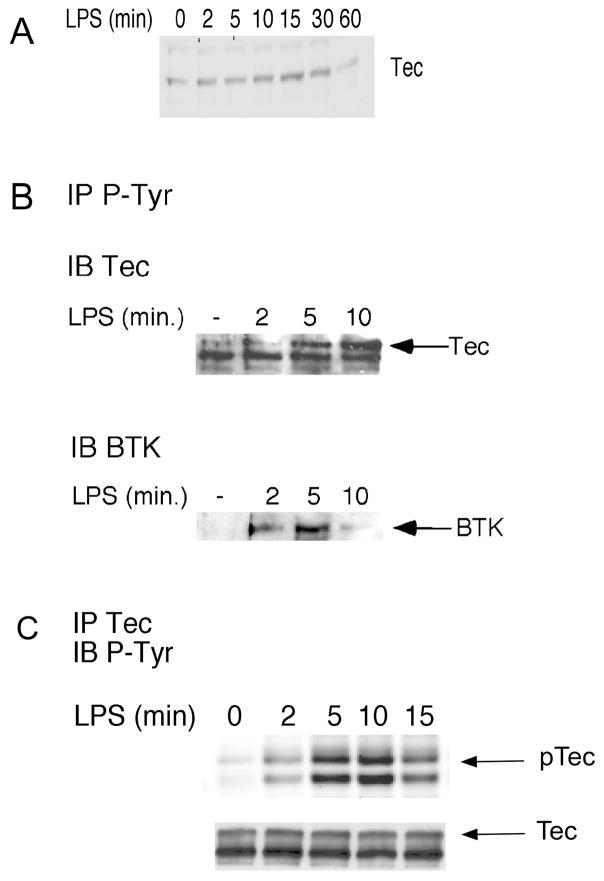

Since Tec and Btk are expressed and functional in human neutrophils [22, 23] and are activated by LPS in macrophages [10, 14], we examined whether the Tec kinases are activated after LPS stimulation in neutrophils. Human neutrophils (20 × 106/condition) in KRPD with 1% HIPPP were incubated under non-suspended conditions for 55 minutes at 37°C and then stimulated with LPS. After LPS stimulation, cell membrane fractions were isolated, as per the methods of Lachance, et al [22], separated on SDS-PAGE gels, and then immunoblotted for Tec. As seen in Figure 1A, stimulation with LPS results in recruitment of Tec to the membrane fraction. Increased levels of Tec are detected in the plasma membrane within 5 minutes after LPS stimulation, peak at 15 minutes, and returns to baseline by 60 minutes. To measure Tec kinase activation after LPS stimulation in human neutrophils, tyrosine phosphorylation was assessed, which correlates with Tec kinase activity [7]. Exposure to LPS results in an increase in the phosphorylation of both Tec and Btk in human neutrophils with the kinetics of Tec activation similar to that of its translocation to the plasma membrane (Figure 1B & C).

Figure 1.

LPS induces the translocation of Tec to the membrane fraction and the phosphorylation of Tec and Btk. Human neutrophils were preincubated at 37°C under nonsuspended conditions for 55 minutes followed by stimulation with LPS (100 ng/ml) for the time indicated. A. Membrane fractions were isolated from cell lysates as per Material and Methods, with proteins separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted (IB) for Tec. B. P-Tyr was immunoprecipitated (IP) from cell lysates with immunoprecipitated proteins separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and immunoblotted for Tec or Btk. C. Tec was immunoprecipitated from cell lysates, proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotting for P-Tyr was performed. Membranes were then immunoblotted for Tec to show that equal amounts of Tec were immunoprecipitated from each sample. Blots shown are representative of at least three experiments, all with similar results.

Inhibition of the Tec kinases decreases LPS-induced JNK, but not p38, activation

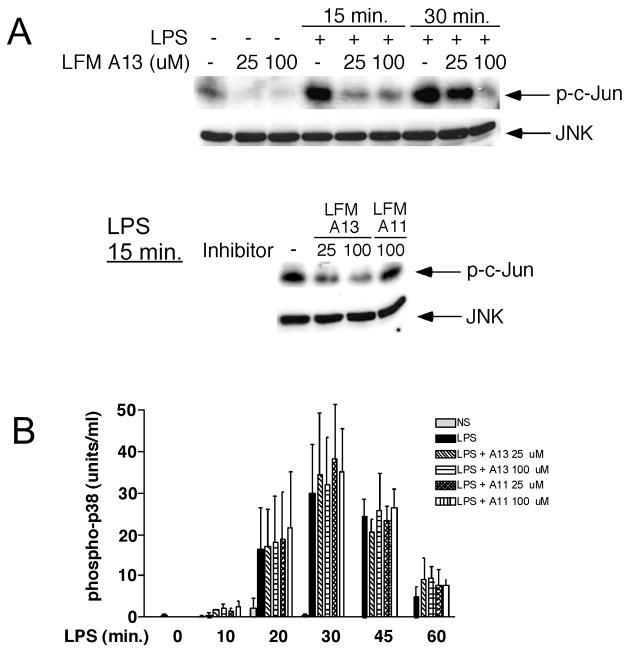

We have previously shown that JNK [2] and p38 [1] are activated by LPS in human neutrophils. Activation of the MAPK in several cell systems requires Tec kinase activity [10, 12, 14, 19, 21, 28–30], although the role of Tec kinases in LPS-induced MAPK activation is incompletely understood, particularly in neutrophils. We hypothesized that the Tec kinases may regulate MAPK activation in human neutrophils stimulated with LPS. To examine this possibility, we utilized LFM-A13, a potent (IC50 = 17.2 μM) and specific inhibitor of the Tec kinases [23, 31] and its inactive structural homolog, LFM-A11. Human neutrophils were preincubated with LFM-A13, or LFM-A11 as control, for 55 minutes, stimulated with LPS, with JNK and p38 activity assessed. Inhibition of the Tec kinases with LFM-A13 decreased LPS-induced JNK activation in a dose dependent manner (Figure 2A), an effect that was not observed with the inactive homolog LFM-A11. In contrast, although it has been proposed that p38 activation is also dependent on Tec kinase activity in other cell systems [10, 20, 29], preincubation of human neutrophils with LFM-A13 prior to LPS stimulation did not alter phosphorylation of p38 as assessed with a phospho-p38 specific ELISA (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Inhibition of the Tec kinases decreases LPS-induced JNK, but not p38, activation. Human neutrophils were preincubated with LFM-A13 (25 or 100 μM), LFM-A11 (25 or 100 μM), or DMSO (0.1%) at 37°C under nonsuspended conditions for 55 minutes followed by stimulation with LPS (100 ng/ml) for the indicated times. A. JNK-1 was immunoprecipitated (IP) from cell lysates, followed by an in vitro kinase assay utilizing c-Jun1–79 as an exogenous substrate. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose. Radiolabeled proteins were identified by autoradiography (upper panel). To ensure that equal amounts of JNK-1 were immunoprecipitated from each sample, membranes were immunoblotted (IB) for JNK-1 (lower panel). Blots shown are representative of three experiments, all with similar results. B. Levels of phosphorylated p38 were measured from cell lysates by ELISA. Results shown are mean ± S.E.M. from two separate experiments.

Inhibition of the Tec kinases decreases LPS-induced actin assembly

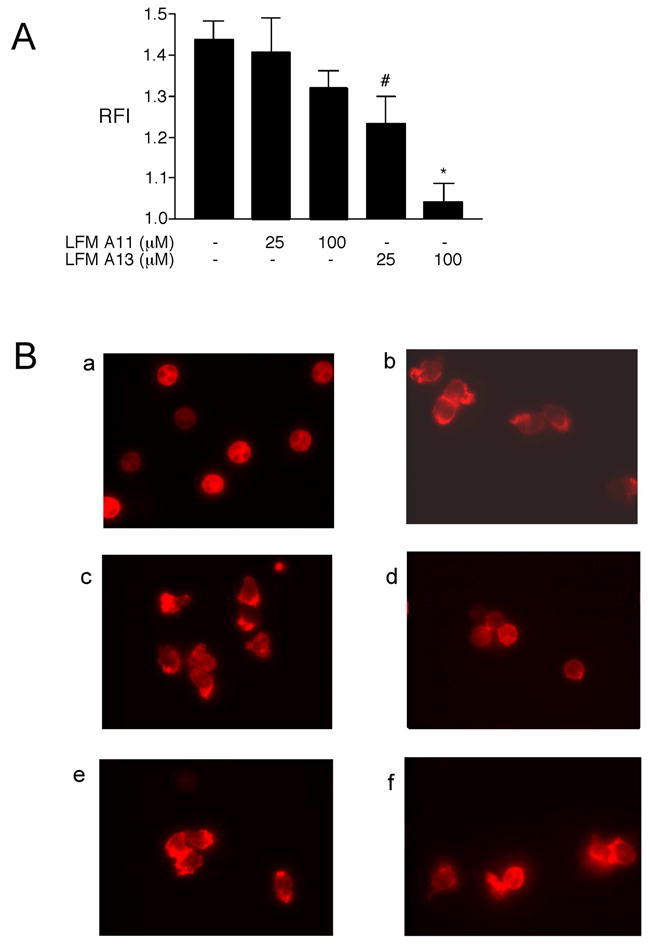

The Tec kinases regulate actin reorganization in lymphocytes and mast cells [32, 33], although their role in regulating actin assembly in cells of the innate immune system remain unexplored. As JNK activation is critical for LPS-induced actin assembly in neutrophils [34] and we show here that the Tec kinases regulate LPS-induced JNK activation (Fig. 2A), we examined the role of the Tec kinases in LPS-induced actin assembly in neutrophils. Neutrophils were preincubated with LFM-A13, or LFM-A11 as a negative control, stimulated with LPS, with actin reorganization assessed. LFM-A13 dose dependently decreased both actin polymerization and actin localization after exposure to LPS (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Inhibition of the Tec kinases decreases LPS-induced actin polymerization and localization. Human neutrophils were preincubated with LFM-A13 (25 or 100 μM), LFM-A11 (25 or 100 μM), or DMSO (0.1%) at 37°C under nonsuspended conditions for 40 minutes followed by stimulation with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 40 minutes. A. After stimulation, cells were labeled with NBD-phallacidin with F-actin polymerization assessed by flow cytometry as previously described [27]. Results are shown with the LPS-stimulated responses normalized to control resulting in a Relative Fluorescent Index (RFI). *p < 0.05 LPS versus LPS + LFM-A13 100 μM; #p < 0.05 LPS + LFM-A13 25 μM versus LPS + LFM-A13 100 μM. B. After stimulation, cells were stained with rhodamine phalloidin and then examined microscopically. a: unstimulated control; b: LPS-stimulated; c: LPS-stimulated, treated with LFM-A13 25 μM; d: LPS-stimulated, treated with LFM-A13 100 μM; e: LPS-stimulated, treated with LFM-A11 25 μM; f: LPS-stimulated, treated with LFM-A11 100 μM. Images shown represent one of three experiments all with similar results. Images are at 400x original magnification.

Inhibition of the Tec kinases decreases LPS-induced cytokine and chemokine expression

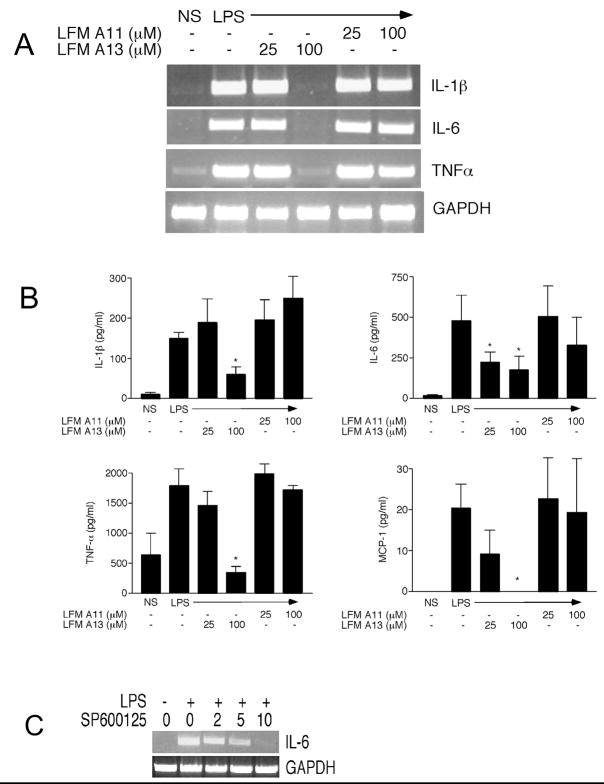

LPS stimulation of neutrophils results in the upregulation of both transcription and protein synthesis of several pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines [35–37]. Previously we have shown that JNK activity is necessary to the LPS-induced upregulation of MCP-1 and TNF-α expression in human neutrophils [2]. Since we show here that the Tec kinases are upstream of JNK activation in neutrophils stimulated with LPS (Figure 2A), we hypothesized that the Tec kinases may therefore also regulate the increase in cytokine and chemokine expression after exposure to LPS. Inhibition of the Tec kinases with LFM-A13 resulted in a reduction in both gene expression, as assessed by RT-PCR, of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β (Figure 4A) and protein synthesis, as determined by ELISA, of MCP-1, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β (Figure 4B). As a role for JNK activation in the LPS-induced expression of IL-6 in neutrophils has not been previously described [2], we investigated further whether the activation of JNK regulates the expression of IL-6 after exposure to LPS. Neutrophils were pretreated with the JNK inhibitor SP600125, exposed to LPS, with IL-6 expression assessed. Inhibition of JNK decreased IL-6 mRNA expression in LPS-stimulated neutrophils in a dose-dependent fashion (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Inhibition of the Tec kinases decreases LPS-induced cytokine and chemokine expression. Human neutrophils were preincubated with LFM-A13 (25 or 100 μM), LFM-A11 (25 or 100 μM), or DMSO (0.1%) at 37°C under nonsuspended conditions for 55 minutes followed by stimulation with LPS (100 ng/ml) for 4 hours. A. RT-PCR for IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and GAPDH was performed. PCR products were resolved on 1% agarose gels followed by staining with ethidium bromide. B. Protein levels of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and MCP-1 in the cell supernatants were measured by ELISA. C. Human neutrophils were preincubated with SP600125 (2–10 μM) or DMSO (0.1%) at 37°C under nonsuspended conditions for 55 minutes followed by stimulation with LPS (100 ng/ml) for 4 hours. RT-PCR for IL-6 and GAPDH was performed. PCR products were resolved on 1% agarose gels followed by staining with ethidium bromide. Results shown are the mean ± S.E.M. of three separate experiments. * p < 0.05 for that condition versus LPS by one-way ANOVA.

DISCUSSION

We have shown here that the Tec kinases are activated by LPS and are an integral component of the LPS-induced signaling pathway in neutrophils leading to JNK activation, actin polymerization, and cytokine expression. Previously it has been shown that the Tec kinases are important in the response of macrophages [10–14] and B cells [8] to LPS, as well as neutrophil signaling after stimulation with fMLP [22, 24] or upon crosslinking of the FcγRIIIB receptor [23]. The present study now confirms and extends these findings by showing here that the Tec kinases are activated in response to LPS and regulate several downstream effector functions in LPS stimulated human neutrophils.

The principal objective of this study was to determine the role of the Tec kinases in both the LPS-induced MAPK signaling pathway and effector functions in human neutrophils. Previously, we have shown that both p38 and JNK are activated in LPS-stimulated neutrophils and that they regulate distinct downstream events [2–4]. As MAPK activation depends on Tec family kinase activity in various other cell systems, including LPS-stimulated macrophages [10, 12, 14], we hypothesized that the Tec kinases might be a constituent of the signaling pathway leading to MAPK activation in LPS-stimulated neutrophils. Based on our data, we conclude that activity of the Tec kinases is critical to the activation of JNK, but not p38, in neutrophils exposed to LPS (Figure 2). Although the Tec kinases have been shown to play a role in ERK activation in several other cell systems [5, 14, 19, 21, 24], we did not examine this relationship here, as we have previously been unable to detect ERK activation in LPS-stimulated human neutrophils [1].

Our findings of the dependence of JNK activation on Tec kinase activity in neutrophils exposed to LPS is similar to that seen in lymphocytes [18, 19] and mast cells [28]. In contrast, however, macrophages isolated from either XLA patients [16] or Btk-deficient mice [14] show normal levels of JNK phosphorylation after LPS stimulation, suggesting that either other, non-Btk, Tec kinases regulate LPS-induced JNK activation in macrophages or that LPS-induced JNK activation in macrophages is independent of the Tec kinases. Our finding that the Tec kinases did not regulate LPS-induced p38 activation in neutrophils are consistent with previous reports that the Tec kinases are not involved in p38 activation in BCR signaling [18, 19] and that LPS-induced p38 activation in macrophages is Btk independent [14, 16]. In contrast, the Tec kinases do appear to reside upstream of p38 in mast cells [29], fMLP-stimulated neutrophils [24], and in G-protein-mediated B cell signaling [20]. Regardless of the results in other cell systems, while p38 is a critical mediator of LPS-induced NF-κB activation and cytokine production in neutrophils [3], the evidence presented here suggests that the Tec kinases are not required for p38 activation in human neutrophils stimulated with LPS. The mechanisms for the differential role of the Tec kinase in fMLP or LPS-induced p38 activation is unexplained and requires further study.

The differences in the role of the Tec kinases in LPS-induced JNK and p38 activation seen in this study may be related to the differences in conditions necessary for their activation. Whereas JNK is activated by LPS [2] and TNF-α [25] only in non-suspended adherent cells, likely due to the requirement for β2 integrin ligation [25], LPS- [1] and TNF-α-induced [38] p38 activation is present in suspended neutrophils. Since we established here that the Tec kinases are upstream of JNK, but not p38, we hypothesize that LPS-induced activation of the Tec kinases may be dependent on β2 integrin ligation. Such a role for the Tec kinases downstream of integrin signaling has been described in epithelial and endothelial cells [39] as well as platelets [40, 41]. Alternatively, the Tec kinases may play a role in inside-out integrin signaling, with integrin activation dependent on Tec activity, as is the case in TCR [42, 43], BCR [44], and FcεRI [45] signaling. Although beyond the focus of the current study, the interrelationship between the Tec kinases and integrin signaling is currently being examined in our laboratory. Finally, further study is warranted to define the relationship of PI3K and Syk to the Tec kinases in the pathway leading to LPS-induced JNK activation in neutrophils, since PI3K and Syk reside upstream of JNK in this pathway [2] and are upstream of the Tec kinases in other cell systems [5, 23].

JNK activity has been shown to be critical to LPS-induced actin assembly in neutrophils and this has been proposed as one mechanism by which JNK inhibition decreased neutrophil influx into the lungs in an in vivo model of lung inflammation induced by LPS [34]. Therefore, we investigated whether the Tec kinases might regulate LPS-induced actin assembly in human neutrophils. Indeed, inhibition of Tec kinase activity resulted in diminished actin polymerization and localization in response to LPS stimulation (Figure 3). These findings are consistent with the previously established role of the Tec kinases in the regulation of actin reorganization in B cells, T cells, and mast cells [32, 33]. Since neutrophil migration to an inflammatory site requires actin assembly and neutrophil recruitment to the site of inflammation was decreased in Xid mice [17], taken together this suggests that pharmacologic manipulation of the Tec kinases may be a potential therapeutic strategy for LPS-mediated disease states.

In addition to the effect on LPS-induced JNK activation and actin assembly, our results suggest that the Tec kinases regulate the expression of TNF-α, IL-6, MCP-1, and IL-1β in human neutrophils after exposure to LPS (Figure 4A & B). While JNK activity has been shown to be critical to the upregulation of MCP-1 [2], and as we show here IL-6 (Figure 4C), expression after LPS stimulation in human neutrophils, it plays only a minor role in LPS-induced TNF-α expression [2] and no role in IL-1β expression (P.G. Arndt, unpublished observations). Therefore, while the Tec kinases likely regulate LPS-induced MCP-1 and IL-6 expression in human neutrophils by way of their effect on JNK kinase activity, the mechanisms by which the Tec kinases regulate TNF- α and IL-1β expression appears to proceed via an alternative pathway that is dependent on neither JNK or p38 activity. Nevertheless, our findings of the role of the Tec kinases in mediating the expression of cytokines and chemokines, and in particular those regulated by JNK activation, in LPS-stimulated human neutrophils are consistent with those shown in other cell systems. Specifically, FcεRI crosslinking in mast cells triggers a signaling pathway in which Btk activity leads to JNK activation and c-Jun phosphorylation, resulting in cytokine production [28, 46]. In addition, macrophages from both XLA patients [10, 12] and Xid mice [13] display impaired TNF-α and IL-1β upregulation in response to LPS and in LPS-stimulated murine macrophages, Btk was shown to regulate AP-1 activity [14], which is known to regulate expression of MCP-1 [47], TNF-α, and IL-6 [48]. In contrast, however, the upregulation of IL-6 expression after LPS stimulation is normal in macrophages from XLA patients [12, 16] and is actually increased in macrophages from Xid mice [14]. Taken together, this suggests that the LPS-induced upregulation of IL-6 expression in macrophages proceeds via a pathway independent of the Tec kinases or that there is redundancy in the signaling pathways involving the Tec kinases. Finally, although not examined herein, as neutrophil apoptosis involves JNK [25], and the Tec kinases regulate apoptosis in mast cells [29], B cells [49], and macrophages [17], taken together this suggests that the Tec kinases may play a role in neutrophil apoptosis. This possibility is being actively investigated in our laboratory.

As neutrophils are terminally differentiated and have a shortened ex vivo lifespan, attempts at genetic modification have been largely unsuccessful. Accordingly, the use of chemical inhibitors is inevitable in the study of neutrophil signaling. Although chemical inhibitors can have nonspecific effects, we have used concentrations of LFM-A13 [31] and SP600125 [50, 51] that have been shown to be specific for the kinases in question and have previously been used in neutrophils [23, 52]. In particular, Heo and colleagues demonstrated a specificity of SP600125 for the inhibition of JNK based on its observed binding with JNK via crystallography [51], whereas LFM-A13 has been shown not to affect the enzymatic activity of a variety of other kinases, including Janus kinases JAK1 and JAK3, Src family kinase Hck, epidermal growth factor receptor kinase, and insulin receptor kinase [31]. In addition, to exclude a chemical effect of LFM-A13, we have included its inactive chemical homolog LFM-A11 as a negative control in all experiments. Since LFM-A13 inhibits the activation of three of the Tec kinases expressed in neutrophils [24], we cannot herein draw any conclusions as to which member of the Tec family regulates the LPS-induced signaling pathway leading to JNK activation in human neutrophils in our study. Alternatively, the Tec kinases may play compensatory roles in the regulation of neutrophil signaling, such that inhibition of all three kinases is necessary to observe the effects described herein. Existing evidence suggests that the Tec kinases may play compensatory roles in the innate immune system. First, the impaired survival and clearance of LPS observed in Btk-deficient mice is prevented by pretreatment with immunoglobulins, suggesting that isolated Btk deficiency may not be sufficient to impair the neutrophil response to LPS [9]. Second, there is no defect in neutrophil influx into the lungs or in cytokine and chemokine levels in the serum or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of Btk-deficient mice treated with inhaled LPS (P.G. Arndt, unpublished observations). We are currently investigating the roles of the individual members of the Tec family in LPS-induced neutrophil signaling.

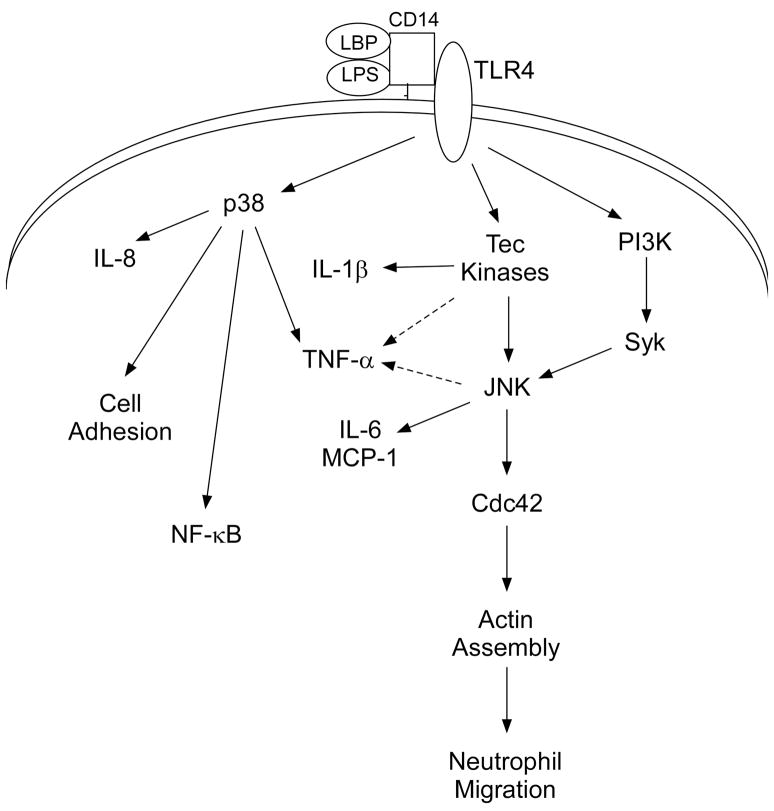

In conclusion, we have demonstrated here that the Tec kinases are activated and play an integral role in the LPS-induced signaling pathway in human neutrophils leading to JNK activation, actin polymerization, and the upregulation of cytokine and chemokine expression (Figure 5). Although p38 plays an important role in LPS-induced effector functions, including NF-κB activation, cell adhesion, and IL-8 expression, evidence presented here suggests that its activation is independent of Tec kinase activation. Since JNK regulates neutrophil recruitment in a model of acute lung inflammation induced by LPS [34] and tyrosine kinase inhibitors improve survival in murine models of LPS-induced septic shock [53], the role of the Tec kinases may be clinically relevant in LPS-mediated diseases such as acute lung injury and septic shock. We anticipate that an improved understanding of the mechanisms by which the Tec kinases become activated and lead to upregulation of neutrophil effector functions may lead to the development of novel therapies.

Figure 5.

Schematic of proposed signaling pathways by which the Tec kinases regulate JNK activation, actin polymerization, and cytokine expression in LPS-stimulated neutrophils. Exposure to LPS results in Tec kinase translocation to the plasma membrane and activation, which is in turn critical for JNK activation. The Tec kinases regulate actin assembly as well as MCP-1, IL-6, and partially TNF-α upregulation in response to LPS stimulation in a JNK-dependent manner. The Tec kinases also play a role in IL-1β and TNF-α synthesis in response to LPS stimulation via a JNK-independent pathway. Notably, although p38 plays an important role in LPS-induced neutrophil functions, including NF-κB activation, cell adhesion, and IL-8 synthesis, its activation is independent of Tec kinase activity.

Acknowledgments

We thank KC Malcolm for critical review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Nick JA, Avdi NJ, Gerwins P, Johnson GL, Worthen GS. Activation of a p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in human neutrophils by lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 1996;156:4867–4875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arndt PG, Suzuki N, Avdi NJ, Malcolm KC, Worthen GS. Lipopolysaccharide-induced c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase activation in human neutrophils: role of phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase and Syk-mediated pathways. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:10883–10891. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309901200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nick JA, Avdi NJ, Young SK, Lehman LA, McDonald PP, Frasch SC, Billstrom MA, Henson PM, Johnson GL, Worthen GS. Selective activation and functional significance of p38alpha mitogen-activated protein kinase in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated neutrophils. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:851–858. doi: 10.1172/JCI5257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nick JA, Young SK, Arndt PG, Lieber JG, Suratt BT, Poch KR, Avdi NJ, Malcolm KC, Taube C, Henson PM, Worthen GS. Selective suppression of neutrophil accumulation in ongoing pulmonary inflammation by systemic inhibition of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Immunol. 2002;169:5260–5269. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.5260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schaeffer EM, Schwartzberg PL. Tec family kinases in lymphocyte signaling and function. Curr Opin Immunol. 2000;12:282–288. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(00)00088-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawakami Y, Kitaura J, Hata D, Yao L, Kawakami T. Functions of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase in mast and B cells. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;65:286–290. doi: 10.1002/jlb.65.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang WC, Collette Y, Nunes JA, Olive D. Tec kinases: a family with multiple roles in immunity. Immunity. 2000;12:373–382. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80189-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klaus GG, Holman M, Johnson-Leger C, Elgueta-Karstegl C, Atkins C. A re-evaluation of the effects of X-linked immunodeficiency (xid) mutation on B cell differentiation and function in the mouse. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2749–2756. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reid RR, Prodeus AP, Khan W, Hsu T, Rosen FS, Carroll MC. Endotoxin shock in antibody-deficient mice: unraveling the role of natural antibody and complement in the clearance of lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 1997;159:970–975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horwood NJ, Mahon T, McDaid JP, Campbell J, Mano H, Brennan FM, Webster D, Foxwell BM. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase is required for lipopolysaccharide-induced tumor necrosis factor alpha production. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1603–1611. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jefferies CA, Doyle S, Brunner C, Dunne A, Brint E, Wietek C, Walch E, Wirth T, O’Neill LA. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase is a Toll/interleukin-1 receptor domain-binding protein that participates in nuclear factor kappaB activation by Toll-like receptor 4. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:26258–26264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301484200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horwood NJ, Page TH, McDaid JP, Palmer CD, Campbell J, Mahon T, Brennan FM, Webster D, Foxwell BM. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase is required for TLR2 and TLR4-induced TNF, but not IL-6, production. J Immunol. 2006;176:3635–3641. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mukhopadhyay S, Mohanty M, Mangla A, George A, Bal V, Rath S, Ravindran B. Macrophage effector functions controlled by Bruton’s tyrosine kinase are more crucial than the cytokine balance of T cell responses for microfilarial clearance. J Immunol. 2002;168:2914–2921. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.6.2914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt NW, V, Thieu T, Mann BA, Ahyi AN, Kaplan MH. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase is required for TLR-induced IL-10 production. J Immunol. 2006;177:7203–7210. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.7203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doyle SL, Jefferies CA, O’Neill LA. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase is involved in p65-mediated transactivation and phosphorylation of p65 on serine 536 during NFkappaB activation by lipopolysaccharide. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:23496–23501. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500053200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perez de Diego R, Lopez-Granados E, Pozo M, Rodriguez C, Sabina P, Ferreira A, Fontan G, Garcia-Rodriguez MC, Alemany S. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase is not essential for LPS-induced activation of human monocytes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:1462–1469. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mangla A, Khare A, Vineeth V, Panday NN, Mukhopadhyay A, Ravindran B, Bal V, George A, Rath S. Pleiotropic consequences of Bruton tyrosine kinase deficiency in myeloid lineages lead to poor inflammatory responses. Blood. 2004;104:1191–1197. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inabe K, Miyawaki T, Longnecker R, Matsukura H, Tsukada S, Kurosaki T. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase regulates B cell antigen receptor-mediated JNK1 response through Rac1 and phospholipase C-gamma2 activation. FEBS Lett. 2002;514:260–262. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02375-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang A, Craxton A, Kurosaki T, Clark EA. Different protein tyrosine kinases are required for B cell antigen receptor-mediated activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase, c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase 1, and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1297–1306. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.7.1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bence K, Ma W, Kozasa T, Huang XY. Direct stimulation of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase by G(q)-protein alpha-subunit. Nature. 1997;389:296–299. doi: 10.1038/38520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schaeffer EM, Debnath J, Yap G, McVicar D, Liao XC, Littman DR, Sher A, Varmus HE, Lenardo MJ, Schwartzberg PL. Requirement for Tec kinases Rlk and Itk in T cell receptor signaling and immunity. Science. 1999;284:638–641. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5414.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lachance G, Levasseur S, Naccache PH. Chemotactic factor-induced recruitment and activation of Tec family kinases in human neutrophils. Implication of phosphatidynositol 3-kinases. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:21537–21541. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201903200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fernandes MJ, Lachance G, Pare G, Rollet-Labelle E, Naccache PH. Signaling through CD16b in human neutrophils involves the Tec family of tyrosine kinases. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78:524–532. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0804479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilbert C, Levasseur S, Desaulniers P, Dusseault AA, Thibault N, Bourgoin SG, Naccache PH. Chemotactic factor-induced recruitment and activation of Tec family kinases in human neutrophils. II. Effects of LFM-A13, a specific Btk inhibitor. J Immunol. 2003;170:5235–5243. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.5235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Avdi NJ, Nick JA, Whitlock BB, Billstrom MA, Henson PM, Johnson GL, Worthen GS. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha activation of the c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway in human neutrophils. Integrin involvement in a pathway leading from cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:2189–2199. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007527200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haslett C, Guthrie LA, Kopaniak MM, Johnston RB, Jr, Henson PM. Modulation of multiple neutrophil functions by preparative methods or trace concentrations of bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Am J Pathol. 1985;119:101–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Erzurum SC, Downey GP, Doherty DE, Schwab B, 3rd, Elson EL, Worthen GS. Mechanisms of lipopolysaccharide-induced neutrophil retention. Relative contributions of adhesive and cellular mechanical properties. J Immunol. 1992;149:154–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hata D, Kitaura J, Hartman SE, Kawakami Y, Yokota T, Kawakami T. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase-mediated interleukin-2 gene activation in mast cells. Dependence on the c-Jun N-terminal kinase activation pathway. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:10979–10987. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.18.10979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kawakami Y, Miura T, Bissonnette R, Hata D, Khan WN, Kitamura T, Maeda-Yamamoto M, Hartman SE, Yao L, Alt FW, Kawakami T. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase regulates apoptosis and JNK/SAPK kinase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:3938–3942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawakami Y, Kitaura J, Hartman SE, Lowell CA, Siraganian RP, Kawakami T. Regulation of protein kinase CbetaI by two protein-tyrosine kinases, Btk and Syk. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:7423–7428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120175097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahajan S, Ghosh S, Sudbeck EA, Zheng Y, Downs S, Hupke M, Uckun FM. Rational design and synthesis of a novel anti-leukemic agent targeting Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK), LFM-A13 [alpha-cyano-beta-hydroxy-beta-methyl-N-(2, 5-dibromophenyl)propenamide] J Biol Chem. 1999;274:9587–9599. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qiu Y, Kung HJ. Signaling network of the Btk family kinases. Oncogene. 2000;19:5651–5661. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takesono A, Finkelstein LD, Schwartzberg PL. Beyond calcium: new signaling pathways for Tec family kinases. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:3039–3048. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.15.3039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arndt PG, Young SK, Lieber JG, Fessler MB, Nick JA, Worthen GS. Inhibition of c-Jun N-terminal kinase limits lipopolysaccharide-induced pulmonary neutrophil influx. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:978–986. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200406-712OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Djeu JY, Serbousek D, Blanchard DK. Release of tumor necrosis factor by human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Blood. 1990;76:1405–1409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malcolm KC, Arndt PG, Manos EJ, Jones DA, Worthen GS. Microarray analysis of lipopolysaccharide-treated human neutrophils. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;284:L663–670. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00094.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lord PC, Wilmoth LM, Mizel SB, McCall CE. Expression of interleukin-1 alpha and beta genes by human blood polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:1312–1321. doi: 10.1172/JCI115134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nahas N, Molski TF, Fernandez GA, Sha’afi RI. Tyrosine phosphorylation and activation of a new mitogen-activated protein (MAP)-kinase cascade in human neutrophils stimulated with various agonists. Biochem J. 1996;318( Pt 1):247–253. doi: 10.1042/bj3180247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen R, Kim O, Li M, Xiong X, Guan JL, Kung HJ, Chen H, Shimizu Y, Qiu Y. Regulation of the PH-domain-containing tyrosine kinase Etk by focal adhesion kinase through the FERM domain. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:439–444. doi: 10.1038/35074500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Laffargue M, Monnereau L, Tuech J, Ragab A, Ragab-Thomas J, Payrastre B, Raynal P, Chap H. Integrin-dependent tyrosine phoshorylation and cytoskeletal translocation of Tec in thrombin-activated platelets. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;238:247–251. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hamazaki Y, Kojima H, Mano H, Nagata Y, Todokoro K, Abe T, Nagasawa T. Tec is involved in G protein-coupled receptor- and integrin-mediated signalings in human blood platelets. Oncogene. 1998;16:2773–2779. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Woods ML, Kivens WJ, Adelsman MA, Qiu Y, August A, Shimizu Y. A novel function for the Tec family tyrosine kinase Itk in activation of beta 1 integrins by the T-cell receptor. Embo J. 2001;20:1232–1244. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.6.1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Finkelstein LD, Shimizu Y, Schwartzberg PL. Tec kinases regulate TCR-mediated recruitment of signaling molecules and integrin-dependent cell adhesion. J Immunol. 2005;175:5923–5930. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.5923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spaargaren M, Beuling EA, Rurup ML, Meijer HP, Klok MD, Middendorp S, Hendriks RW, Pals ST. The B cell antigen receptor controls integrin activity through Btk and PLCgamma2. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1539–1550. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kitaura J, Eto K, Kinoshita T, Kawakami Y, Leitges M, Lowell CA, Kawakami T. Regulation of highly cytokinergic IgE-induced mast cell adhesion by Src, Syk, Tec, and protein kinase C family kinases. J Immunol. 2005;174:4495–4504. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hata D, Kawakami Y, Inagaki N, Lantz CS, Kitamura T, Khan WN, Maeda-Yamamoto M, Miura T, Han W, Hartman SE, Yao L, Nagai H, Goldfeld AE, Alt FW, Galli SJ, Witte ON, Kawakami T. Involvement of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase in FcepsilonRI-dependent mast cell degranulation and cytokine production. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1235–1247. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.8.1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shyy YJ, Li YS, Kolattukudy PE. Structure of human monocyte chemotactic protein gene and its regulation by TPA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;169:346–351. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)90338-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sweet MJ, Hume DA. Endotoxin signal transduction in macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 1996;60:8–26. doi: 10.1002/jlb.60.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Uckun FM, Waddick KG, Mahajan S, Jun X, Takata M, Bolen J, Kurosaki T. BTK as a mediator of radiation-induced apoptosis in DT-40 lymphoma B cells. Science. 1996;273:1096–1100. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5278.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bennett BL, Sasaki DT, Murray BW, O’Leary EC, Sakata ST, Xu W, Leisten JC, Motiwala A, Pierce S, Satoh Y, Bhagwat SS, Manning AM, Anderson DW. SP600125, an anthrapyrazolone inhibitor of Jun N-terminal kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:13681–13686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251194298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heo YS, Kim SK, Seo CI, Kim YK, Sung BJ, Lee HS, Lee JI, Park SY, Kim JH, Hwang KY, Hyun YL, Jeon YH, Ro S, Cho JM, Lee TG, Yang CH. Structural basis for the selective inhibition of JNK1 by the scaffolding protein JIP1 and SP600125. Embo J. 2004;23:2185–2195. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kato T, Noma H, Kitagawa M, Takahashi T, Oshitani N, Kitagawa S. Distinct role of c-Jun N-terminal kinase isoforms in human neutrophil apoptosis regulated by tumor necrosis factor-alpha and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2008;28:235–243. doi: 10.1089/jir.2007.0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Novogrodsky A, Vanichkin A, Patya M, Gazit A, Osherov N, Levitzki A. Prevention of lipopolysaccharide-induced lethal toxicity by tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Science. 1994;264:1319–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.8191285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]