Abstract

Background

The mollicute Mycoplasma conjunctivae is the etiological agent leading to infectious keratoconjunctivitis (IKC) in domestic sheep and wild caprinae. Although this pathogen is relatively benign for domestic animals treated by antibiotics, it can lead wild animals to blindness and death. This is a major cause of death in the protected species in the Alps (e.g., Capra ibex, Rupicapra rupicapra).

Methods

The genome was sequenced using a combined technique of GS-FLX (454) and Sanger sequencing, and annotated by an automatic pipeline that we designed using several tools interconnected via PERL scripts. The resulting annotations are stored in a MySQL database.

Results

The annotated sequence is deposited in the EMBL database (FM864216) and uploaded into the mollicutes database MolliGen http://cbi.labri.fr/outils/molligen/ allowing for comparative genomics.

Conclusion

We show that our automatic pipeline allows for annotating a complete mycoplasma genome and present several examples of analysis in search for biological targets (e.g., pathogenic proteins).

Background

Mycoplasmas (class Mollicutes) are among the smallest microorganisms capable of self-replication and autonomous life [1]. The genus Mycoplasma includes a large number of highly genomically-reduced species which in nature are associated with hosts either commensally or pathogenically [2]. General features of the class Mollicutes are small genome, lack of cell wall and low GC content.

Indeed, the Mycoplasma species have genomes of 0.6 to 1.3 Mbp. Weisburg et al. (1989) [3] and Woese et al. (1980) [4] revealed that Mycoplasma have evolved from more classical bacteria of the firmicutes taxon by a so-called regressive evolution that resulted in massive genome reduction [5] and minimal metabolic activities. Consequently, they adopted a strict parasitic life style, mainly occurring as extracellular parasites often restricted to a living host, with some species having the ability to invade host cells as described by Sirand-Pugnet et al. (2007) [5], Rosengarten et al. (2000) [6] and Citti et al. (2005) [7]. They have a predilection for the mucosal surfaces, where they successfully compete for nutrients with many other organisms, establishing chronic infections [5]. They do not show specific virulence factor as known in other bacteria, instead they seem to use toxic metabolic intermediates that they secrete and translocate to the host cells as virulence factors [8]. Additionally, due to the lack of cell wall, they are not affected by some antibiotics which target synthesis of cell wall such penicillin or other beta-lactam antibiotics making these organisms particularly interesting in medicine.

Infectious keratoconjunctivitis (IKC)

Mycoplasma conjunctivae is considered as the major etiological agent of Infectious KeratoConjunctivitis (IKC) for both domestic and wild caprinae species. In the European Alps it affects several species such as alpine ibex (Capra ibex ibex), alpine chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra rupicapra), and mouflon (Ovis orientalis musimon), as well as in domestic sheep and goat [9]. In Switzerland, M. conjunctivae is known to be the primary cause of this disease [10].

The implied role of M. conjunctivae is based on the frequent isolation of this organism from inflamed eyes and on limited attempts to induce ocular disease experimentally showing that M. conjunctivae is one agent responsible for epidemic keratoconjunctivitis [11]. Nonetheless, even if the molecular epidemiology has been well described by Belloy et al. (2003) [9], the molecular infection mechanism is still not established and remains a mystery.

Methods

Bacterial strain

M. conjunctivae type strain HRC/581T (NCTC10147) [12] was grown on standard mycoplasma broth medium enriched with 20% horse serum, 2.5% yeast extract and 1% glucose (Axcell Biotechnologies). The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 20 min, washed three times in TES buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.8% NaCl, pH 7.5), and then re-suspended in TES buffer to a concentration of approximately 109 bacteria/ml. DNA was extracted by the guanidium thiocyanate method [13], extracted 3 times with PCIA (Phenol: CHCl3: Isoamylalcohol = 49.5: 49.5: 1) and 3 times with CIA (CHCl3: Isoamylalcohol = 99: 1), precipitated with 50% isoproanol, washed 2 times with 70% ethanol to remove salt, dried in the air for 15 min and re-suspended in double distilled H2O at a concentration of 500 μg/ml.

Sequencing

Sequencing and assembly of the genome was carried out by Microsynth AG. The quality of the isolated genomic DNA was verified by gel electrophoresis and displayed a pure high molecular weight DNA. The DNA was sheared by passing it several times through a needle, in order to construct two different libraries: a plasmid library and a fosmid library. For the plasmid library (2–12 Kbp inserts), the genomic DNA was passed 30 times through a 30-Gauge needle and sonicated for 10 seconds (sonication strength 3 on a Digital Sonifier 450 from Branson Ultrasonics corp, Danbury, CT, USA). For the fosmid library (32 Kbp inserts), the genomic DNA was passed 10 times through a 23-Gauge needle without sonication.

Small fragments were ligated with a linker, fractionated twice through 0.8% agarose gels. Fractions of 6 different sizes (from 2 to 12 Kbp) were cut out from the gel and cloned into vector pOTW12 (Sanger Institute). Moreover, the large fragments were fractionated using a CHEF-DR II System (BIORAD). Fragments of 32 Kbp were cut out from the gel and ligated into pCC1Fos (Epicentre Biotechnology Inc.).

From the plasmid library 11'300 clones and from the fosmid library 384 clones were end-sequenced on an ABI 3730 capillary sequencer. A second part of the small fragments were sequenced using 454 Life Science FLX technology leading to 263'163 reads that were reduced to 78'498 reads covering 20'569'079 bp after applying a quality cut-off filter (approx. 22× coverage).

Assembly

The assembly was carried out using the SeqMan module of the DNASTAR Lasergene version 7 combining both classical Sanger sequences (ABI3730) and 454 FLX reads. A check was conducted with "amosvalidator" of the AMOS package [14], allowing identifying suspicious regions in the assembly. To help in the assembly process the 384 fosmids paired-end reads were aligned to the final sequence. The reads display a nice spreading at regular intervals except for 2 clones that were absent from the results. The 2 regions were analyzed for the presence of potentially lethal genes for E. coli. The first region contains a homologue of the gene lepA that is known to be lethal when overexpressed in E. coli [15]. This region also contains a restriction enzyme that might cut E. coli genome. The second region contains a transposase and some phage genes. This might explain the toxicity of these two fosmids in E. coli.

Automatic annotation

The automatic annotation pipeline was entirely built locally using available software and linking them with Perl scripts.

Gene prediction was carried out using Glimmer 3.02 [16] and the genetic code specific for Mycoplasma (e.g., UGA encodes a tryptophane). The interpolated context models (ICM) were calculated by self-training on the long ORFs of the contigs. The RNAs were predicted using Infernal with models obtained from RFAM [17], tRNAscan-SE [18], and blastn for 16S and 23S [19].

Predicted coding sequences (CDS) were translated using the EMBOSS package (extractseq, transeq, revseq) [20] and a similarity search was run by blastp against the UniProt/Swiss-Prot knowledgebase (Release 56.2 of 23-Sep-2008: 398181 entries) [21]. The CDS were also scanned against the HAMAP families [22] to identify orthologous protein families. In addition the CDS were searched for potential known domains using InterProScan [23], and for biased compositional regions with SEG [24] and Marcoil [25].

The biological interest of an annotation project is to identify the gene products by designating a descriptive common name for the protein and its function with as much specificity as the evidence supports. We use homology-based annotation transfer to assign the name and associated information of gene product: Gene symbol, EC number if protein is identified as an enzyme and other features.

Homology search is performed by blastp that allows finding the best matches with the highest significant sequence similarity appearing between the putative proteins sequences compared first to a database of known mycoplasma proteins and secondly to proteins from the UniProt/Swiss-Prot knowledgebase. Additionally, matches with HAMAP protein family permits to support homology annotation and raise the confidence level of annotation transfer. Other characterization features like functional domains constitute an additional support evidence of function assignment (Table 1). The results obtained from the various programs are parsed and stored in GFF3 format in a local MySQL database. The EMBL format is produced from the data stored in this database and deposited at the EBI EMBL database, the accession number is FM864216.

Table 1.

Functional assignment criteria

| Source | Known Protein | Putative | Hypothetical |

| Blastp (Mycoplasma DB) | Evalue < e-20 | Evalue between | Evalue |

| >e-20 and <e-4 | > e-4 or No match | ||

| Blastp (Swissprot DB) | Evalue < e-20 | Evalue between | Evalue |

| >e-20 and <e-4 | > e-4 or No match | ||

| HAMAP families | Confident protein family match | No confident protein family match | N/A |

| Interpro domains | If no HAMAP family match. Support evidence from at least one InterPro member database | Support evidence from one or none Interpro member database | |

Description of the criteria used to assign the genes products into the 3 following categories: Known Protein (known function: significant e-value and supported by confident protein family and functional domains), Putative protein (unclear function: twilight zone e-value but supported by functional domains) and Hypothetical protein (unknown function: non-significant e-value or no match in databases).

In order to assess the confidence of the results provided by our annotation pipeline, we used the known genome of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae (strain 232) already annotated (NCBI entry AE017332) for comparing pipeline results with those provided at NCBI. The annotation pipeline identifies 741 CDS and 32 non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) whereas only 691 CDS and 36 ncRNAS are known. The 91.1% of total genes were correctly predicted leaving only 23 genes not found by the predictor programs. Regarding the functional annotation, our pipeline provides 83.7% of correct gene annotations and even in some cases complements the existing one. 7.4% of CDS are wrongly annotated or in a different way. The 69 genes predicted in addition to known genes could be considered as false positives even if they also could represent new potential genes of M. hyopneumoniae genome (Table 2). Using results of M. hyopneumoniae 232 annotation, we evaluated the specificity and sensitivity of the pipeline and obtained a sensitivity of 92% and a specificity of 90% (Table 3).

Table 2.

Results obtained for M. hyopneumoniae 232 annotation

| All genes | CDS | ncRNA | |

| Total of M. hyopneumoniae 232 known genes | 727 | 691 | 36 |

| Total annotated genes using pipeline | 773 | 741 | 32 |

| Total correct predictions * | 704 | 672 | 32 |

| Total known genes not predicted * | 23 | 19 | 4 |

| Total correct gene annotations | 647 | 618 | 29 |

| Total predicted genes incorrectly or differently annotated | 57 | 54 | 3 |

| Total predicted genes in additionally annotated by pipeline | 69 | 69 | 0 |

* CDS were predicted using Glimmer3 and ncRNAs were predicted using Blastn for 23S and 16S rRNAs, tRNAScan-SE for tRNAs and Infernal for other ncRNAs

Table 3.

Evaluation of the sensitivity and the specificity of the pipeline based on re-annotation of the M. hyopneumoniae 232 genome.

| Total genes detected | FP | TP | FN | Specificity TP/(TP+FP) | Sensitivity TP/(TP+FN) |

| 773 | 69 | 647 | 57 | 90% | 92% |

FP = False Positive, TP = True Positive, FN = False Negative

Results

General genome features

Composition and functional gene assignment, origin of replication

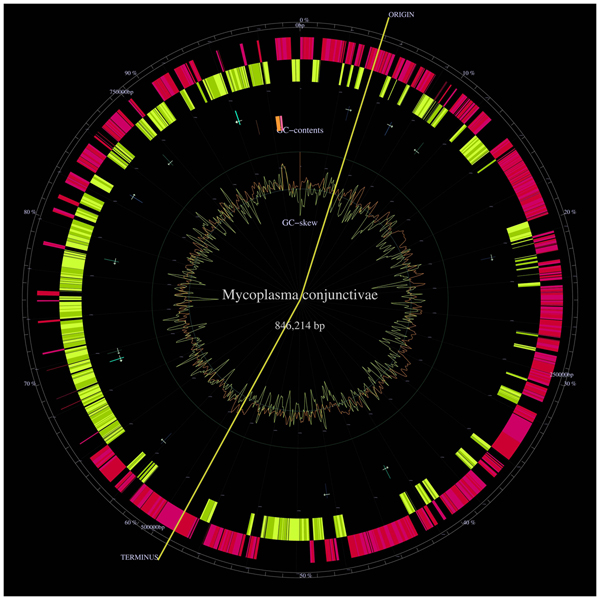

The genome consists of a single chromosome with a size estimated of about 0.9 Mbp. Currently, more than 95% of the genome is available as a single contig, but due to the presence of repeated sequences, we experienced difficulties in assembling the sequences to close the gap. The contig has a size of 846'214 bp with a G+C content of 29% (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Genome map. Mycoplasma conjunctivae genome map generated by GenomeProjector tool and available in http://myconj.vital-it.ch/GenomeProjector/. This map represents from the outer ring in wards, genes on direct strand (pink), genes on complementary strand (yellow), tRNAs (green arrows), rRNAs (pink or orange stripes depending on the strand), GC content (brown lines), GC skew (yellow lines). The replication origin and terminus are predicted from the GC skew shift points and are in a different position than the one we found.

A total of 734 genes have been computationally predicted. We found both 23S and 16S ribosomal RNAs in unique copies located next to each other. The 5S ribosomal RNA is located remotely of 23S and 16S genes. We identified 28 transfer RNAs covering all 20 amino acids. Other non-coding RNAs were found: bacterial RNase P class B, TPP riboswitch (THI element), tmRNA (proteolysis signal) and the bacterial signal recognition particle RNA.

Additionally, 699 genes were predicted as coding sequences for proteins. 49% of those genes have a clear homologue with a known function. 5.6% of those genes were annotated as "putative proteins" because the closest known protein was aligned with a marginal e-value. While the remaining 45% have unknown function, and were named as "hypothetical" proteins. From those hypothetical proteins, 75% matched non-significatively to other proteins and 25% are considered unique for M. conjunctivae because no match was obtained by blastp against both databases. A summary is shown in Table 4 and Table 5.

Table 4.

Summary of M. conjunctivae genome features

| Genome Features | |

| Length (bp) | 846,214 |

| G + C content (mole%) | 29.0% |

| Functionally assigned protein CDSs | 344 |

| Putative protein CDSs | 39 |

| Hypothetical protein CDSs | 316 |

| 23S rRNA | 1 |

| 16S rRNA | 1 |

| 5S rRNA | 1 |

| Bacterial RNase P class B | 1 |

| TPP riboswitch (THI element) | 1 |

| tmRNA | 1 |

| Bacterial signal recognition particle RNA | 1 |

| Transfer RNA genes | 28 |

Table 5.

Top 20 biological processes. Relevant information with a biological meaning was searched in priority. We list the top 20 of biological process that are accomplished by the newly annotated genes.

| Biological process | Proteins matched |

| translation | 68 |

| metabolic process | 32 |

| transport | 31 |

| proteolysis | 18 |

| tRNA aminoacylation for protein translation | 15 |

| DNA repair | 13 |

| DNA replication | 12 |

| carbohydrate metabolic process | 11 |

| phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent sugar phosphotransferase system | 11 |

| regulation of transcription | 10 |

| DNA modification | 9 |

| glycolysis | 9 |

| ATP synthesis coupled proton transport | 8 |

| DNA methylation | 7 |

| DNA recombination | 7 |

| DNA integration | 6 |

| electron transport | 6 |

| biosynthetic process | 5 |

| nucleoside metabolic process | 5 |

| Protein folding | 5 |

It is important to note that our method (homology based annotation) does not allow to distinguish between close homologues having different functions.

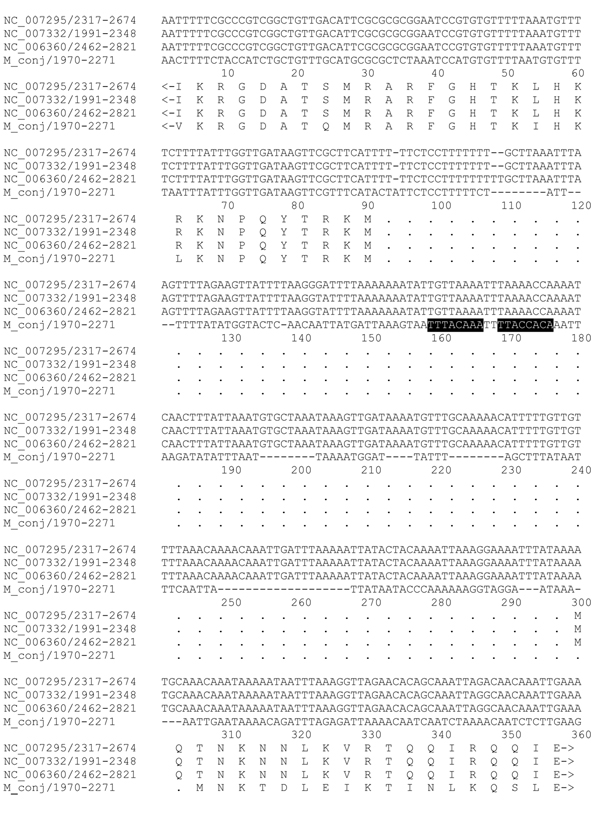

The origin of replication (oriC) was searched by comparing the sequences of 3 strains of M. hyopneumoniae with the sequence of M. conjunctivae in the region of dnaA gene (Figure 2). We attempted to identify several features that have been associated with replication origins in other bacterial species, including mollicutes. Bacterial origins of replication are typically located in the vicinity of the dnaA and dnaN genes. Usually several dnaA-box motifs are found within the intergenic regions around dnaA gene [26]. We searched unsuccessfully for the presence of consensus dnaA-box motifs with the pattern TTATC [CA]A [CA] using fuzznuc of the EMBOSS package [27]. When we used a slightly different, more relaxed dnaA-box consensus motifs TT [AT] [AC] [ACT]A [AC]A, two sequences matching each of these patterns were found between the dnaA and rpmH genes (Figure 2). However, well over 3,000 hits located throughout the rest of the genome were also seen. Therefore, the specificity of the pattern used to try to detect dnaA-box motifs was very low, decreasing our confidence in the significance of the sequences identified.

Figure 2.

Origin of replication. The region between rpmH and dnaA genes for the 3 M. hyopneumoniae strains aligned with M. conjunctivae. The two putative dnaA boxes are shown in black. M. hyopneumoniae J (NC_007295), M. hyopneumoniae 7448 (NC_007332), M. hyopneumoniae 232 (NC_006360), M. conjunctivae (FM864216).

These findings are in contrast to the multiple dnaA-boxes found in the intergenic regions surrounding dnaA in other mollicutes [26]. In addition to the presence of dnaA-box motifs, replication origins can also frequently be identified by looking for biases in strand composition through measures such as the cumulative GC skew [28-30]. For M. conjunctivae, we found no significant asymmetries that can be readily detected with GC skew. The lack of a clear bias in M. conjunctivae is similar to that observed for the M. hyopneumoniae [31]. Therefore, the only significant feature of the M. conjunctivae genome that provides any possible indication of the location of the origin of replication is the presence of the dnaA gene. Otherwise, there are no features that allow definitive mapping of the origin to the intergenic region upstream of the dnaA gene, as seen in other bacteria.

Potential pathogenic features

Bacteria have many ways to produce virulence that reside in the ability to adhere, invade and cause damage to host cells. Various strategies of pathogenicity such as cytolysins, toxins and invasins enable other bacteria to produce infection. In Mycoplasma species no such typical primary virulence genes have been found. Mycoplasmas seem rather to use intrinsic metabolic and catabolic functions to cause disease in the affected host and to ensure the microbe's survival. Our efforts to identify genes involved in the pathogenicity of Mycoplasma conjunctivae were concentrated on the one hand, try to find those primary virulence genes, toxins principally, rare in other mycoplasmas. On the other hand, on metabolic pathways that has been proposed by studies carried out in other mycoplasmas [8].

Glycerol pathway

We found using manual blastp queries by an expert, the genes for a glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (glpO), a glycerol kinase (glpK), a glycerol uptake facilitator protein (glpF) and an ABC transporter system (Sn-glycerol-3-phosphate transport system permease) that are implicated in the glycerol metabolism producing cell damage, inflammation and disease in Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. mycoides Small Colony (SC) [8].

The pathway starts with the assimilation of glycerol by the ABC glycerol transporter (gtsA, gtsB and gtsC). Afterwards, the glycerol is phosphorylated into glycerol-3-phosphate, then oxidized by GlpO in presence of O2 into dihydroxyactone-phosphate (DHAP) producing one molecule of H2O2. H2O2 is released directly inside the host cells by the transmembrane GlpO protein leading to cell death [8]. The absence of any gene having a catalase or dismutase activity favors this hypothesis.

The identification of those genes in Mycoplasma conjunctivae constitutes an important discovery given that a relationship between the glycerol metabolism and cytotoxicity is established in the laboratory[8]. Further work to validate this hypothesis in M. conjunctivae is required and has been started in collaboration with a laboratory of the Institute for Veterinary Bacteriology (University of Bern).

Toxins

Toxins constitute an important type of virulence factors in several bacteria. Thereby, we searched for toxins in M. conjunctivae and we found 3 proteins highly similar with toxins of Treponema hyodysenteriae (Brachyspira hyodysenteriae). Those proteins are Hemolysin A (hlyA), Hemolysin B (hlyB) and Hemolysin C (hlyC). The 3 genes are scattered on the genome.

Those proteins are present in other mycoplasmas, particularly M. hyopneumoniae and M. capricolum, and even if in those species, these toxins are not essential for pathogenicity mechanisms, it can not be excluded that these toxins contribute to the pathogenicity of M. conjunctivae.

IS elements

Insertion sequences (IS) are short DNA elements that function as simple transposable elements by coding for proteins implicated in the transposition activity. Transposase and other regulatory protein are the proteins generally coded by IS elements: The transposase catalyses the enzymatic reaction allowing the IS to move. Regulatory proteins act by enhancing or inhibiting the transposition activity. The coding region in an insertion sequence is usually flanked by inverted repeats [32].

We found several genes coding for complete or partial transposases (Table 6). An IS1138 insertion element has particularly brought our attention. IS1138 elements belong to IS3 family are prevalent in other mycoplasmas and are the only (with IS1138b) that have been demonstrated directly to undergo autonomous transposition [32,33]. Interestingly a transposase for one IS1138 insertion elements is followed by homologues of a methylase HpaI and a type II restriction enzyme HpaI from Haemophilus parainfluenzae forming a restriction-methylation cassette. The hypothesis of a horizontal transfer from H. parainfluenza to M. conjunctivae was formulated. We evaluated the G+C content of this cassette, but we did not observe a higher G+C content inside the cassette compared to the surrounding area. If the G+C content inside the cassette would be different from that of M. conjunctivae (29%) and similar to that of H. parainfluenzae (~41%) it could constitute an evidence of the transfer.

Table 6.

List of M. conjunctivae transposases detected.

| gene | Product | start | end | strand | length | Condition of the sequence |

| MCJ_00022 | IS1138 | 23818 | 24999 | - | 1181 | Complete |

| MCJ_00059 | ? | 61624 | 61728 | + | 104 | Partial |

| MCJ_00099 | IS1138 | 97032 | 98213 | + | 1181 | Complete |

| MCJ_00207 | IS1138 | 192412 | 192660 | - | 248 | Same transposase split in two ORFs |

| MCJ_00208 | IS1138 | 192717 | 193088 | - | 371 | |

| MCJ_00215 | ISMag1 | 198177 | 199265 | + | 1088 | Complete |

| MCJ_00399 | IS1138 | 430830 | 432011 | - | 1181 | Complete |

| MCJ_00428 | IS1138 | 474034 | 474138 | + | 104 | Partial |

| MCJ_00553 | ISMHp1 | 639264 | 639500 | - | 236 | Partial |

| MCJ_00635 | IS1634AM | 742041 | 743714 | + | 1673 | Complete |

Comparative genomics

The list of proteins was classified and compared to 4 other mycoplasma genomes as shown in Table 7. The main difference with other mycoplasma is an apparently low carbohydrate and transport metabolism that could explain the need for a strong glycerol pathway, as well as the large number of hypothetical proteins probably due to the fully automatic annotation process.

Table 7.

Genome comparison. Functional classification of proteins of 5 sequenced mycoplasma genomes

| Functional categories | Mycoplasma. hyopneumoniae 232 | Mycoplasma pulmonis | Mycoplasma genitalium | Mycoplasma mobile | Mycoplasma conjunctivae |

| (892 kb) | (964 kb) | (816 kb) | (777 kb) | (846 kb) | |

| Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis | 100 | 108 | 108 | 108 | 90 |

| Transcription | 22 | 27 | 16 | 23 | 16 |

| DNA replication, recombination and repair | 75 | 118 | 49 | 72 | 55 |

| Posttranslational modification, protein turnover | 20 | 24 | 19 | 22 | 15 |

| Energy production and conversion | 25 | 29 | 20 | 29 | 25 |

| Carbohydrate transport and metabolism | 57 | 68 | 32 | 50 | 30 |

| Amino acid transport and metabolism | 25 | 27 | 17 | 24 | 20 |

| Nucleotide transport and metabolism | 19 | 22 | 20 | 18 | 17 |

| Coenzyme transport and metabolism | 9 | 12 | 12 | 17 | 8 |

| Lipid transport and metabolism | 6 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 7 |

| Inorganic ion transport and metabolism | 14 | 18 | 17 | 15 | 5 |

| Other | 118 | 124 | 87 | 107 | 95 |

| No known function | 201 | 195 | 78 | 139 | 316 |

| Total CDSs | 691 | 782 | 484 | 633 | 699 |

Discussion

Mycoplasma conjunctivae is the fourteenth genome of a mycoplasma species that has been fully sequenced. Phylogenetically, the closest relative among the sequenced mycoplasmas is M. hyopneumoniae reflected by the high similarity of most of the proteins identified in M. conjunctivae.

The analysis of M. conjunctivae genome features, describes this organism as a typical mycoplasma, with a genome size and a G+C content within the range of other mycoplasma genomes. The comparison of mycoplasma genome sizes demonstrates that the sequence length is variable not only within the same genus but even among strains of the same species as shown in Table 8. Even if we do not know the final size of the genome, we expect a chromosome length of about 900'000 bp, size almost similar with the genome size of M. hyopneumoniae.

Table 8.

Genome comparison. Genome size of 15 sequenced genomes of species belonging to Mycoplasma genus http://www.ebi.ac.uk/genomes/bacteria.html, including M. conjunctivae.

| EMBL AC | Species name | Genome Size | G+C content |

| CU179680 | Mycoplasma agalactiae PG2 chromosome | 877,438 | 29.7% |

| CP001047 | Mycoplasma arthritidis 158L3-1 | 820,453 | 30.7% |

| CP000123 | Mycoplasma capricolum subsp. capricolum ATCC 27343 | 1,010,023 | 23.8% |

| AE015450 | Mycoplasma gallisepticum R | 996,422 | 31.5% |

| L43967 | Mycoplasma genitalium G37 | 580,076 | 31.7% |

| AE017332 | Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae 232 | 892,758 | 28.6% |

| AE017244 | Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae 7448 | 920,079 | 28.5% |

| AE017243 | Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae J | 897,405 | 28.5% |

| AE017308 | Mycoplasma mobile 163 K | 777,079 | 25% |

| BX293980 | Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. mycoides SC str. PG1 | 1,211,703 | 24% |

| BA000026 | Mycoplasma penetrans HF-2 | 1,358,633 | 25.7% |

| U00089 | Mycoplasma pneumoniae M129 | 816,394 | 40% |

| AL445566 | Mycoplasma pulmonis UAB CTIP | 963,879 | 26.6% |

| AE017245 | Mycoplasma synoviae 53 | 799,476 | 28.5% |

| FM864216 | Mycoplasma conjunctivae | 846,214 | 29% |

Globally the mycoplasma genomes have a characteristically low G+C content within the range of 23.8 to 40 mol% (Table 8). The highest G+C content found in M. pneumoniae and the lowest in M. capricolum. Regarding Mycoplasma conjunctivae, G+C content has a typical value of about 29%. The codon usage is similar to that of M. hyopneumoniae and opposite to that of M. capricolum and M. mycoides [31,34,35].

The presence of repeats across the genome was the principal difficulty for finishing the genome assembly. Insertion sequence (IS) elements are reported in the majority of mycoplasmas and in M. conjunctivae we found transposases for IS-elements in the genome. Some of those transposases genes are complete sequences and some other are fragmented showing a predicted length of less than 1000 bp. Since those insertion elements are nearly identical they created difficulties for assembling the genome.

The findings highlighted by this project, principally the glycerol pathway, require further experimental confirmation. In particular, the hypothesis for damaging the host cells by the glycerol metabolism need to be confirmed by demonstrating the localization of GlpO in the membrane and the release of H2O2 outside the cell. If this hypothesis can be verified, the possibility to block at any stage the glycerol pathway could constitute a candidate target for controlling the disease.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we created an automatic pipeline to annotate a prokaryotic genome sequence using various tools for the prediction and the identification of the genes. This pipeline is customized for handling sequences of mycoplasma species.

We deposited the Mycoplasma conjunctivae genome fully annotated in the EMBL database (FM864216). Data stored into our local database can be searched and genome can be visualized through our website http://myconj.vital-it.ch. Analysis of annotated genes gives new insights about potential mechanisms of pathogenicity as well as the possibility to go deeper into the knowledge of Mycoplasma conjunctivae and the IKC disease and opens the way to finding methods to prevent M. conjunctivae infections of domestic animals as reservoir for this pathogen and hence prevent IKC in wild animals.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

JF proposed and supported the project. SPCC created the pipeline and did the analysis. MAQ did the genomic library. TS and MAQ sequenced the clones. TS, GW and CW did the assembly. SPCC and LF wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank for support the "Programmes actions intégrées PAI" – Germaine de Staël. We would like to particularly thank Mrs Denise Schmidheini for her kind help in initiating and supporting this sequencing project.

We are grateful to the Vital-IT platform for offering calculation time on their computing cluster, and in particular to Mr Volker Flegel for his help in installing and debugging the necessary software.

This article has been published as part of BMC Bioinformatics Volume 10 Supplement 6, 2009: European Molecular Biology Network (EMBnet) Conference 2008: 20th Anniversary Celebration. Leading applications and technologies in bioinformatics. The full contents of the supplement are available online at http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2105/10?issue=S6.

Contributor Information

Sandra P Calderon-Copete, Email: Sandra.Calderon@unil.ch.

George Wigger, Email: georges.wigger@microsynth.ch.

Christof Wunderlin, Email: Christof.Wunderlin@microsynth.ch.

Tobias Schmidheini, Email: t.schmidheini@microsynth.ch.

Joachim Frey, Email: joachim.frey@vbi.unibe.ch.

Michael A Quail, Email: mq1@sanger.ac.uk.

Laurent Falquet, Email: Laurent.Falquet@isb-sib.ch.

References

- Pettersson B, Uhlén M, Johansson KE. Phylogeny of some mycoplasmas from ruminants based on 16S rRNA sequences and definition of a new cluster within the hominis group. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:1093–1098. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-4-1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balish MF, Krause DC. Mycoplasmas: A Distinct Cytoskeleton for Wall-Less Bacteria. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;11:244–255. doi: 10.1159/000094058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisburg WG, Tully JG, Rose DL, Petzel JP, Oyaizu H, Yang D, Mandelco L, Sechrest J, Lawrence TG, Van Etten J, Maniloff J, Woese CR. A phylogenetic analysis of the mycoplasmas: Basis for their classification. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:6455–6467. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.12.6455-6467.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woese CR, Maniloff J, Zablen LB. Phylogenetic analysis of the mycoplasmas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:494–498. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.1.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirand-Pugnet P, Lartigue C, Marenda M, Jacob D, Barré A, Barbe V, Schenowitz C, Mangenot S, Couloux A, Segurens B, de Daruvar A, Blanchard A, Citti C. Being pathogenic, plastic, and sexual while living with a nearly minimal bacterial genome. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e75. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosengarten R, Citti C, Glew M, Lischewski A, Droesse M, Much P, Winner F, Brank M, Spergser J. Hostpathogen interactions in mycoplasma pathogenesis: Virulence and survival strategies of minimalist prokaryotes. Int J Med Microbiol. 2000;290:15–25. doi: 10.1016/S1438-4221(00)80099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citti C, Browning GF, Rosengarten R. Phenotypic diversity and cell invasion in host subversion by pathogenic mycoplasmas. In: Blanchard A, Browning GF, editor. Mycoplasmas: pathogenesis, molecular biology, and emerging strategies for control. Horizon Bioscience, Wymondham, Norfolk, United Kingdom; pp. 439–483. [Google Scholar]

- Pilo P, Vilei EM, Peterhans E, Bonvin-Klotz L, Stoffel MH, Dobbelaere D, Frey J. A metabolic enzyme as a primary virulence factor of Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. mycoides small colony. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:6824–6831. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.19.6824-6831.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belloy L, Janovsky M, Vilei EM, Pilo P, Giacometti M, Frey J. Molecular epidemiology of Mycoplasma conjunctivae in Caprinae: transmission across species in natural outbreaks. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:1913–1919. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.4.1913-1919.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belloy L, Vilei EM, Giacometti M, Frey J. Characterization of LppS, an adhesin of Mycoplasma conjunctivae. Microbiology. 2003;149:185–193. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.25864-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baas EJ, Trotter SL, Franklin RM, Barile MF. Epidemic caprine keratoconjunctivitis: recovery of Mycoplasma conjunctivae and its possible role in pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 1977;18:806–815. doi: 10.1128/iai.18.3.806-815.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barile MF, Del Giudice RA, Tully JG. Isolation and characterization of Mycoplasma conjunctivae sp. n. from sheep and goats with keratoconjunctivitis. Infect Immun. 1972;5:70–76. doi: 10.1128/iai.5.1.70-76.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitcher DG, Saunders NA, Owen RJ. Rapid extraction of bacterial genomic DNA with guanidium thiocyanate. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1989;8:151–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.1989.tb00262.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phillippy AM, Schatz MC, Pop M. Genome assembly forensics: finding the elusive mis-assembly. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R55. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-3-r55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March PE, Inouye M. Characterization of the lep operon of Escherichia coli. Identification of the promoter and the gene upstream of the signal peptidase I gene. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:7206–7213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delcher AL, Bratke KA, Powers EC, Salzberg SL. Identifying bacterial genes and endosymbiont DNA with Glimmer. Bioinformatic. 2007;23:673–679. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths-Jones S, Moxon S, Marshall M, Khanna A, Eddy S, Bateman A. Rfam: annotating non-coding RNAs in complete genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005:D121–D124. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice P, Longden I, Bleasby A. EMBOSS: The European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite. Trends in Genetics. 2000;16:276–277. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(00)02024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bairoch A, Apweiler R, Wu CH, Barker WC, Boeckmann B, Ferro S, Gasteiger E, Huang H, Lopez R, Magrane M, Martin MJ, Natale DA, O'Donovan C, Redaschi N, Yeh LS. The Universal Protein Resource (UniProt) Nucleic Acids Res. 2005:D154–D159. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima T, Auchincloss AH, Coudert E, Keller G, Michoud K, Rivoire C, Bulliard V, de Castro E, Lachaize C, Baratin D, Phan I, Bougueleret L, Bairoch A. HAMAP: a database of completely sequenced microbial proteome sets and manually curated microbial protein families in UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009:D471–478. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter S, Apweiler R, Attwood TK, Bairoch A, Bateman A, Binns D, Bork P, Das U, Daugherty L, Duquenne L, Finn RD, Gough J, Haft D, Hulo N, Kahn D, Kelly E, Laugraud A, Letunic I, Lonsdale D, Lopez R, Madera M, Maslen J, McAnulla C, McDowall J, Mistry J, Mitchell A, Mulder N, Natale D, Orengo C, Quinn AF, Selengut JD, Sigrist CJ, Thimma M, Thomas PD, Valentin F, Wilson D, Wu CH, Yeats C. InterPro: the integrative protein signature database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009:D211–215. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wootton JC, Federhen S. Statistics of local complexity in amino acid sequences and sequence databases. Computers & Chemistry. 1993;17:149–163. doi: 10.1016/0097-8485(93)85006-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delorenzi M, Speed T. An HMM model for coiled-coil domains and a comparison with PSSM based predictions. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:617–625. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.4.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordova CM, Lartigue C, Sirand-Pugnet P, Renaudin J, Cunha RA, Blanchard A. Identification of the origin of replication of the Mycoplasma pulmonis chromosome and its use in oriC replicative plasmids. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:5426–5435. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.19.5426-5435.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita MQ, Yoshikawa H, Ogasawara N. Structure of the dnaA and DnaA-box region in the Mycoplasma capricolum chromosome: conservation and variations in the course of evolution. Gene. 1992;110:17–23. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90439-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roten CA, Gamba P, Barblan JL, Karamata D. Comparative Genometrics (CG): a database dedicated to biometric comparisons of whole genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:142–144. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrázek J, Karlin S. Strand compositional asymmetry in bacterial and large viral genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3720–3725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha EP, Danchin A, Viari A. Universal replication biases in bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:11–16. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minion FC, Lefkowitz EJ, Madsen ML, Cleary BJ, Swartzell SM, Mahairas GG. The genome sequence of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae strain 232, the agent of swine mycoplasmosis. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:7123–7133. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.21.7123-7133.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhugra B, Dybvig K. Identification and characterization of IS a transposable element from Mycoplasma pulmonis that belongs to the IS3 family. Mol Microbiol. 1138;7:577–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dybvig K, Voelker L. Molecular biology of Mycoplasmas. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1996;50:25–57. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westberg J, Persson A, Holmberg A, Goesmann A, Lundeberg J, Johansson KE, Pettersson B, Uhlén M. The genome sequence of Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. mycoides SC type strain PG1T, the causative agent of contagious bovine pleuropneumonia (CBPP) Genome Res. 2004;14:221–227. doi: 10.1101/gr.1673304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe JD, Stange-Thomann N, Smith C, DeCaprio D, Fisher S, Butler J, Calvo S, Elkins T, FitzGerald MG, Hafez N, Kodira CD, Major J, Wang S, Wilkinson J, Nicol R, Nusbaum C, Birren B, Berg HC, Church GM. The complete genome and proteome of Mycoplasma mobile. Genome Res. 2004;14:1447–1461. doi: 10.1101/gr.2674004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]