Abstract

Background and purpose:

The effects of a phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor, roflumilast, on bleomycin-induced lung injury were explored in ‘preventive’ and ‘therapeutic’ protocols and compared with glucocorticoids.

Experimental approach:

Roflumilast (1 and 5 mg·kg−1·d−1, p.o.) or dexamethasone (2.5 mg·kg−1·d−1, p.o.) was given to C57Bl/6J mice from day 1 to 14 (preventive) or day 7 to 21 (therapeutic) after intratracheal bleomycin (3.75 U·kg−1). In Wistar rats, roflumilast (1 mg·kg−1·d−1, p.o.) was compared with methylprednisolone (10 mg·kg−1·d−1, p.o.) from day 1 to 21 (preventive) or from day 10 to 21 (therapeutic), following intratracheal instillation of bleomycin (7.5 U·kg−1). Analyses were performed at the end of the treatment periods.

Key results:

Preventive. Roflumilast reduced bleomycin-induced lung hydroxyproline, lung fibrosis and right ventricular hypertrophy; muscularization of intraacinar pulmonary vessels was also attenuated. The PDE4 inhibitor diminished bleomycin-induced transcripts for tumour necrosis factor (TNFα), transforming growth factor (TGFβ), connective tissue growth factor, αI(I)collagen, endothelin-1 and the mucin, Muc5ac, in lung, and reduced bronchoalveolar lavage fluid levels of TNFα, interleukin-13, TGFβ, Muc5ac, lipid hydroperoxides and inflammatory cell counts. Therapeutic. In mice, roflumilast but not dexamethasone reduced bleomycin-induced lung αI(I)collagen transcripts, fibrosis and right ventricular hypertrophy. Similar results were found in the rat.

Conclusions and implications:

Roflumilast prevented the development of bleomycin-induced lung injury, and alleviated the lung fibrotic and vascular remodeling response to bleomycin in a therapeutic protocol, the latter being resistant to glucocorticoids.

Keywords: Roflumilast, phosphodiesterase 4 inhibition, bleomycin, pulmonary fibrosis, steroids

Introduction

Lung fibrotic remodelling occurs in pulmonary conditions such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis/usual interstitial pneumonia (IPF/UIP), acute respiratory distress syndrome, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma. Inhibitors of phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) diminish inflammatory cell functions secondary to an increase in cellular cAMP (Sanz et al., 2005). In addition, PDE4 inhibitors target pulmonary fibroblasts, vascular smooth muscle cells, airway epithelial and endothelial cells, all of them being critically involved in these lung diseases. Therefore, PDE4 inhibitors would potentially have the capacity to alleviate pulmonary inflammation, fibrotic and vascular remodeling or mucociliary malfunction that may be considered as common facets of various pulmonary disorders (Houslay et al., 2005; Bender and Beavo, 2006).

Indeed, roflumilast, a PDE4 inhibitor being currently in advanced clinical development, demonstrated therapeutic benefit in COPD (Boswell-Smith and Page, 2006). The anti-inflammatory potential of roflumilast has been documented in a broad array of in vitro and in vivo models culminating in clinical observations that this PDE4 inhibitor reduces airway neutrophil influx following segmental lipopolysaccharide challenge in human volunteers, and diminished neutrophil numbers in induced sputum of patients with COPD (Bundschuh et al., 2001; Hatzelmann and Schudt, 2001; Grootendorst et al., 2007; Hohlfeld et al., 2008). In vivo, roflumilast prevents lung parenchymal, airway and vascular architectural changes provoked by chronic tobacco smoke, allergen challenge or hypoxia. Thus, roflumilast alleviates emphysema in mice exposed to tobacco smoke over 7 months (Martorana et al., 2005), reduces subepithelial collagen deposition in the airways of mice repetitively challenged with ovalbumin over 6 weeks (Kumar et al., 2003) or attenuates full muscularization of intraacinar pulmonary arterioles following chronic hypoxia in rats over 21 days (Izikki et al., 2007). From these observations one may reason that, by extending its anti-inflammatory potential, the PDE4 inhibitor may directly address pulmonary architectural aberrations in lung disorders.

Bleomycin-induced lung injury in rodents is a commonly used in vivo model to estimate the anti-fibrotic potential of a therapeutic procedure (Moeller et al., 2008). The fibrogenic response to bleomycin is considered as being secondary to oxidative stress and involving multiple factors such as interleukin-13 (IL-13), tumour necrosis factor-α (TNFα) and transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) (Fichtner-Feigl et al., 2006; Moeller et al., 2008). An early study revealed that a cAMP analogue mitigates the development of lung fibrosis following intratracheal instillation of bleomycin in hamsters (O'Neill et al., 1992). More recent investigations showing that mice deficient in cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 or the prostacyclin (IP) receptor develop a more severe lung fibrosis in response to bleomycin compared with the wild type, provide indirect evidence for a protective role of cAMP in this setting (Keerthisingam et al., 2001; Lovgren et al., 2006). However, the potential of a PDE4 inhibitor in this experimental model of a lung fibrotic response has not yet been explored.

The current study was designed to characterize the effects of roflumilast on the lung fibrotic response secondary to intratracheal instillation of bleomycin in mice or rat in a preventive or a therapeutic protocol, and to compare the PDE4 inhibitor with glucocorticoids, representing standard anti-inflammatory drugs being effective in this in vivo setting, but only after preventive administration (Chaudhary et al., 2006).

Methods

Animals and experimental design

Experiments were conducted according to the European Community and Spanish regulations for the use of experimental animals and approved by the institutional committee of animal research. Mice studies used specific pathogen-free male C57Bl/6J mice (Charles River, Barcelona, Spain) at 8 weeks of age which are reported to mount a robust early inflammatory response followed by pulmonary fibrotic remodeling secondary to bleomycin. Mice were housed under standard conditions with free access to water and food. Mice were anaesthetized with ketamine/medetomidine and then a single dose of bleomycin at 3.75 U·kg−1 (dissolved in 50 µL of saline) was administered intratracheally, via the transoral route, at day 1. This dose of bleomycin reproducibly generated pulmonary fibrosis in previous experiments. Sham-treated mice received the identical volume of intratracheal saline instead of bleomycin.

Roflumilast or dexamethasone was administered once daily in two different protocols, ‘preventive’ and ‘therapeutic’, to discriminate between effects on the early inflammatory (≤7 days after bleomycin) and the subsequent fibrotic response (>7 days after bleomycin) (Izbicki et al., 2002; Nakagome et al., 2006; Moeller et al., 2008). In the preventive protocol, animals received test compounds starting from the day of bleomycin administration (day 1) until the end of the experiment at day 14. In the therapeutic protocol, roflumilast or dexamethasone was administered from day 7 to the end of the experiment at day 21. Mice were allocated to the following groups: (i) saline + vehicle; (ii) saline + roflumilast (0.5, 1 or 5 mg·kg−1·d−1); (iii) bleomycin + vehicle; (iv–vi) bleomycin + roflumilast (0.5, 1 or 5 mg−1·kg−1·d−1); and (vii) bleomycin + dexamethasone (2.5 mg·kg−1·d−1). Roflumilast 0.5 mg·kg−1·d−1 was used in the preventive protocol only. Test compounds were given in methocel suspensions, once daily, p.o. by gavage in a volume of 10 mL·kg−1. With these doses of roflumilast or dexamethasone, no adverse effects were observed during the experiments.

At the end of the treatment period, mice were sacrificed by a lethal injection of sodium pentobarbital followed by exsanguination. After opening the thoracic cavity, trachea, lungs and heart were removed en bloc. Bronchoalveolar lavage was performed (see below) and lungs were weighed and then processed for histological, biochemical or molecular biology studies. The right ventricular (RV) wall of the heart was dissected free and weighed along with the left ventricle wall plus septum (LV + S), and the resulting weights are reported as RV/LV + S ratio to provide an index of right ventricular hypertrophy. Body weights were recorded every 3 days.

In a separate experimental setting, male Wistar rats (250 g of weight, Charles River, Barcelona, Spain) were given a single, intratracheal dose of bleomycin (7.5 U·kg−1) or sham (saline) at day 1 and then allocated to the following treatment groups (i) sham + vehicle; (ii) bleomycin + vehicle; (iii) bleomycin + roflumilast (1 mg·kg−1·d−1) day 1–21; (iv) bleomycin + roflumilast (1 mg·kg−1·d−1) day 10–21; (v) bleomycin + methylprednisolone (10 mg·kg−1·d−1) day 1–21; and (vi) bleomycin + methylprednisolone (10 mg·kg−1·d−1) day 10–21 in order to differentiate effects of the PDE4 inhibitor compared with the glucocorticoid on the early inflammatory response (preventive protocol, day 1–21) as opposed to the fibrotic response (therapeutic protocol, day 10–21) in agreement with a previous report (Chaudhary et al., 2006). Test compounds were given once daily, p.o. by gavage. At day 21, rats were killed and analyses performed as described above.

Doses of roflumilast were selected in agreement with previous in vivo animal studies (Bundschuh et al., 2001; Kumar et al., 2003; Martorana et al., 2005; Izikki et al., 2007) and to yield plasma concentrations corresponding to therapeutic levels in clinical studies (data on file).

Bronchoalveolar lavage

At the end of experiments (preventive protocol, mice), bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was recovered following five consecutive washes of the right lung with 0.6 mL aliquots of saline flushed through a tracheal cannula. Cell suspensions were concentrated by low speed centrifugation (150× g, 5 min) and cells resuspended in buffer. Total cell counts were made in a haemocytometer. Differential cell counts were determined from cytospin preparations by counting about 300 cells stained with May-Gruenwald-Giemsa. Total protein content in BALF supernatants was measured by using the bicinchoninic acid assay for the colorimetric detection and quantitation of total protein following the instructions of the manufacturer. Absorbances were determined at 562 nm using a spectrophotometer and proteins were calculated based on a bovine serum albumin (BSA) standard curve. Results are expressed in µg protein per lung. BALF supernatants were stored at −80°C for measurements of the mucin Muc5ac, tumour necrosis factor (TNF)α, interleukin (IL)-13 and transforming growth factor (TGF)β1.

Histological studies

Lung histology was conducted as previously reported (Serrano-Mollar et al., 2002). Tissue blocks (4 µm thickness) were stained with haematoxylin-eosin for assessment of the inflammatory and fibrotic injury and with Masson's trichrome to detect collagen deposition. Severity of lung fibrosis was scored on a scale from 0 (normal lung) to 8 (total fibrotic obliteration of fields) according to Ashcroft (Ashcroft et al., 1988). Airway epithelial mucin forming cells were stained with Alcian blue.

To determine the extent of pulmonary vascular remodeling, the degree of muscularization of intraacinar pulmonary vessels was determined. Lung sections (4 µm thickness) were stained with haematoxylin-eosin, orcein and mouse monoclonal anti-α-smooth muscle actin (1:200 v/v) and analysed using a morphometric system (Olympus BH2 Research Microscope, Olympus America Inc, Center Valley, PA, USA) with the software package Image ProPlus 5.0 (MediaCybernetics, Silver Spring, MD, USA). In each animal, 25–40 intraacinar arteries were analysed. Arteries with an external diameter between 20 and 50 µm were categorized as fully muscularized, partially muscularized or non-muscularized as reported (Schermuly et al., 2005).

Biochemical studies

Lung hydroxyproline content was measured based on the conversion of hydroxyproline (obtained following acidic hydrolysis of collagen-containing lung extracts) with chloramine T and p-dimethylamino benzaldehyde into a chromophore with an absorbance at 561 nm and results presented as µg per lung.

Muc5ac protein in BALF was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as outlined (Mata et al., 2003). In brief, 40 µg of total BALF protein was incubated with 100 µL bicarbonate-carbonate buffer at 40°C in a 96-well plate until dryness. Wells were washed, blocked with phosphate-buffered saline, 0.05% (v/v) Tween-20 and 2% (w/v) BSA and incubated with mouse monoclonal antibody against Muc5ac (clone 45M1), 2 µg·mL−1. Following addition of a secondary antibody (anti-mouse Ig, conjugated to horseradish peroxidase) and several wash steps substrate solution was added. Results are expressed as x-fold change of absorbance at 450 nm versus controls.

Tumour necrosis factor-α, IL-13 and TGFβ1 in BALF was measured using ELISA according to the manufacturer's instructions and results were given as pg·mL−1 BALF. Lipid hydroperoxides were quantitated with a commercially available assay and results expressed as µmol·L−1 in BALF.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA (about 20 µg) was purified from about 15 to 30 mg lung tissue using TriPure isolation reagent, exactly as outlined by the manufacturer. The obtained RNA was kept at −80°C. RNA samples were treated with Ambion's DNA-free™ DNase reagent as outlined by manufacturer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, USA) to remove contaminating DNA from RNA preparations. RNA content was measured at 260/280 nm. RNA (0.5–1 µg) was reverse transcribed by using Taqman® Reverse Transcription (RT) Reagents. Briefly, 0.5–1 µg RNA (in 38.5 µL RNase-free water) was incubated with 2.5 µL of MultiScribe™ Reverse Transcriptase (final concentration: 1.25 U·µL−1), 2 µL RNase inhibitor (final concentration: 0.4 U·µL−1), 5 µL random hexamer primer (final concentration: 2.5 µmol·L−1), 20 µL desoxyNTP mixture (final concentration: 500 µmol·L−1 of each dATP, dGTP, dCTP, dTTP), 22 µL MgCl2 (final concentration: 5.5 mmol·L−1) and 10 µL 10× TaqMan® RT buffer to a final volume of 100 µL. cDNA synthesis was performed for 60 min at 42°C in a PTC-100TM Peltier Thermal Cycler. Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for relative quantitation of murine Muc5ac, prepro-endothelin-1, TGFβ1, connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), α I (I) collagen and TNFα mRNA was performed using the ABI prism 7900 HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturers instructions. Taqman® Universal PCR Master Mix (PN 4304437) was used, and the corresponding Taqman® Gene Expression assays (Assay on demand from Applied Biosystems) are as follows: Mm99999068_m1 for murine TNFα, Mm00441724_m1 for murine TGFβ1, Mm01276725_g1 for murine Muc5ac, Mm00438656_m1 for murine preproET-1, Mm00515790_g1 for murine CTGF and Mm00801666_g1 for murine α I (I) collagen. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) served as calibrator (pre-Development Assay Reagents, pDAR, ref. 4352339E for mouse GAPDH). The assay mixture comprised 0.9 µmol·L−1 forward and reverse primer and 0.25 µmol·L−1 FAM-labelled probe, 1× Taqman® Universal PCR Master Mix and cDNA (0.02–20 ng). PCR was conducted in final assay volumes of 25 µL using a standardized thermocycler protocol as instructed by the manufacturer. A 2 min period at 50°C was followed by successive periods of 10 min at 95°C, and of 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C and 1 min at 60°C.

The averaged cycle threshold (CT) was determined and relative gene expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT procedure as described by the manufacturer (Applied Biosystems).

Statistics

Results are given as means ± SEM. Statistical analysis of data was carried out by analysis of variance (anova) followed by appropriate post hoc tests including Bonferroni's correction as appropriate.

Materials

Bleomycin was from Merck (Barcelona, Spain). Roflumilast was provided by Nycomed GmbH (Konstanz, Germany). Methocel was from Colorcon (Idastein, Germany). Dexamethasone (cyclodextrin complex), methylprednisolone, chloramine T, p-dimethylamino benzaldehyde were acquired from Sigma Quimica (Madrid, Spain). The bichinchoninic acid assay for quantification of proteins was from Pierce (Rockford, IL, USA). Mouse monoclonal anti-α-smooth muscle actin and anti-Muc5aC antibody was purchased from Dako (Glostrup, Danmark) and Neomarkers Labvision (Fremont, CA, USA) respectively. Horseradish conjugated anti-mouse Ig antibody was from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). ELISA kits to quantitate cytokines in BALF were acquired from different sources: mouse TNFα from eBiosciences (San Diego, CA, USA), mouse IL-13 and TGFβ1 from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA) respectively. An assay kit to measure lipid hydroperoxides was from Cayman Europe (Tallin, Estonia). TriPure reagent for RNA isolation was from Roche (Mannheim, Germany). All reagents for real time RT-PCR were purchased from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA, USA).

Results

Effects of roflumilast on bleomycin-induced pulmonary inflammation, parenchymal remodelling and mucus formation in mice in the preventive protocol

A marked influx of inflammatory cells, particularly of neutrophils, into the airways was observed, following intratracheal bleomycin instillation. Roflumilast dose-dependently reduced the bleomycin-induced accumulation of total cells, neutrophils and macrophages in BAL (Table 1). In parallel, roflumilast mitigated the lung parenchymal inflammatory response following bleomycin as illustrated by a reduction of inflammatory cell infiltrates (Figure 1A, a–d). An increase in BALF protein content secondary to bleomycin (7709 ± 440 µg protein per lung versus 717 ± 33 µg protein per lung in controls) was diminished by roflumilast (5242 ± 369 µg protein per lung at 5 mg·kg−1·d−1; P < 0.05, n = 7) indicating that the PDE4 inhibitor may attenuate lung microvascular leakage.

Table 1.

Effects of roflumilast (ROF) on bleomycin (BLM)-induced changes in total and differential cell counts in BALF from mice

| Total cells (×106) | Macrophages (×106) | Neutrophils (×106) | Lymphocytes (×106) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 1.51 ± 0.19 | 1.55 ± 0.18 | 0.019 ± 0.007 | 0.008 ± 0.004 |

| BLM | 8.77 ± 0.93# | 7.41 ± 0.80# | 0.929 ± 0.180# | 0.430 ± 0.082# |

| BLM + ROF 0.5 | 6.09 ± 1.42 | 5.22 ± 1.23 | 0.640 ± 0.147 | 0.240 ± 0.071 |

| BLM + ROF 1 | 5.87 ± 0.83* | 4.79 ± 0.70* | 0.537 ± 0.221 | 0.510 ± 124 |

| BLM + ROF 5 | 3.99 ± 0.40* | 3.37 ± 0.43* | 0.304 ± 0.098* | 0.320 ± 0.052 |

Roflumilast was given p.o. at 0.5 (ROF 0.5), 1 (ROF 1) or 5 (ROF 5) mg·kg−1·d−1 from the day of bleomycin (BLM) (3.75 U·kg−1) administration until the end of experiment at day 14 (preventive treatment). Data are mean ± SEM of 12 (control), 13 (BLM) and 7–9 (ROF) experiments.

P < 0.05 from control;

P < 0.05 from bleomycin. Roflumilast at either dose did not affect cell counts in control rats (not shown).

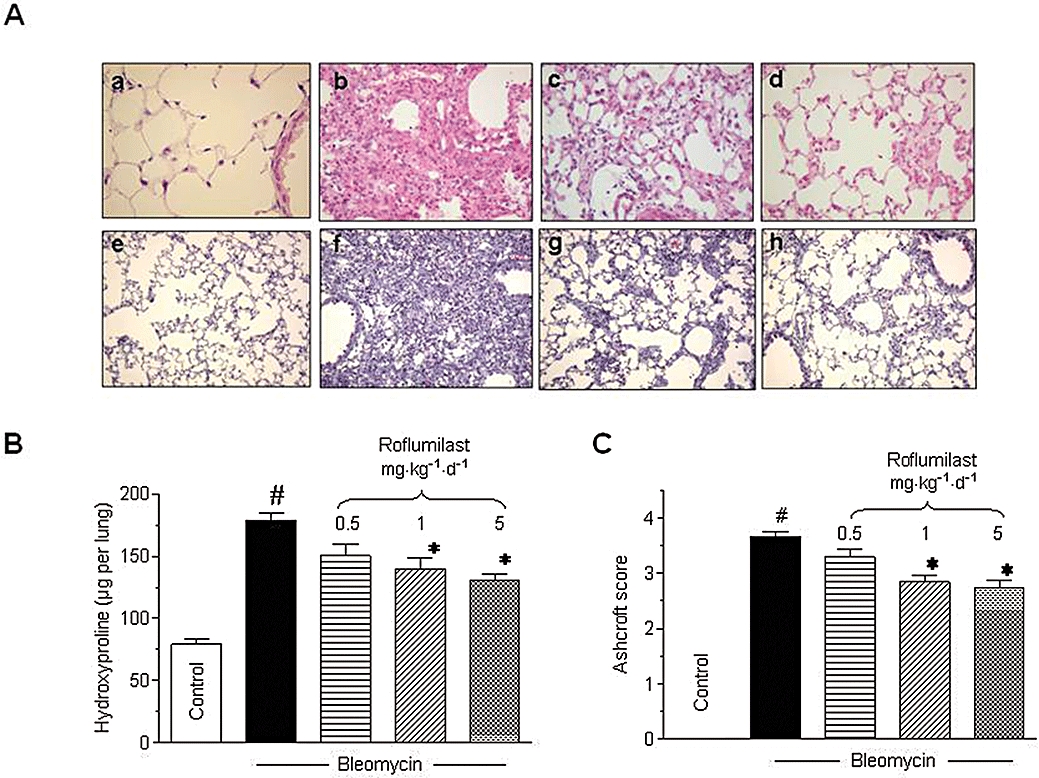

Figure 1.

Effects of roflumilast on bleomycin-induced fibrotic response in mouse lung. Mice received a single dose of bleomycin (3.75 U·kg−1) intratracheally at day 1 and roflumilast (0.5, 1 or 5 mg·kg−1·d−1 p.o., once daily) or vehicle was administered from day 1 to 14 (preventive protocol) until analysis at day 14. Histology (A), lung hydroxyproline content (µg per lung) (B) and fibrosis score (C) were assessed as described in Methods. In A, upper panels (a–d) show H&E staining (original magnification ×40) and lower panels (e–h) Masson's trichrome (original magnification ×10; collagen is stained in blue) for controls (a,e), bleomycin (b,f), bleomycin + roflumilast 1 mg·kg−1·d−1 (c,g) and bleomycin + roflumilast 5 mg·kg−1·d−1 (d,h). #P < 0.05 versus control, *P < 0.05 versus bleomycin. Results are given as mean ± SEM from n = 6 (B, C).

Bleomycin induced a fibrotic response in lung, with enhanced deposition of collagen, as visualized by Masson's trichrome staining (Figure 1A, e–h). Roflumilast alleviated histologically observed multifocal fibrotic lesions, resulting in fewer organized and smaller foci and reduced septal enlargement. Augmented collagen deposition was reflected by an approximately 2-fold increase in hydroxyproline content of lung. Roflumilast dose-dependently reduced this bleomycin-induced increment in hydroxyproline (Figure 1B) and diminished the Ashcroft fibrosis score (Figure 1C).

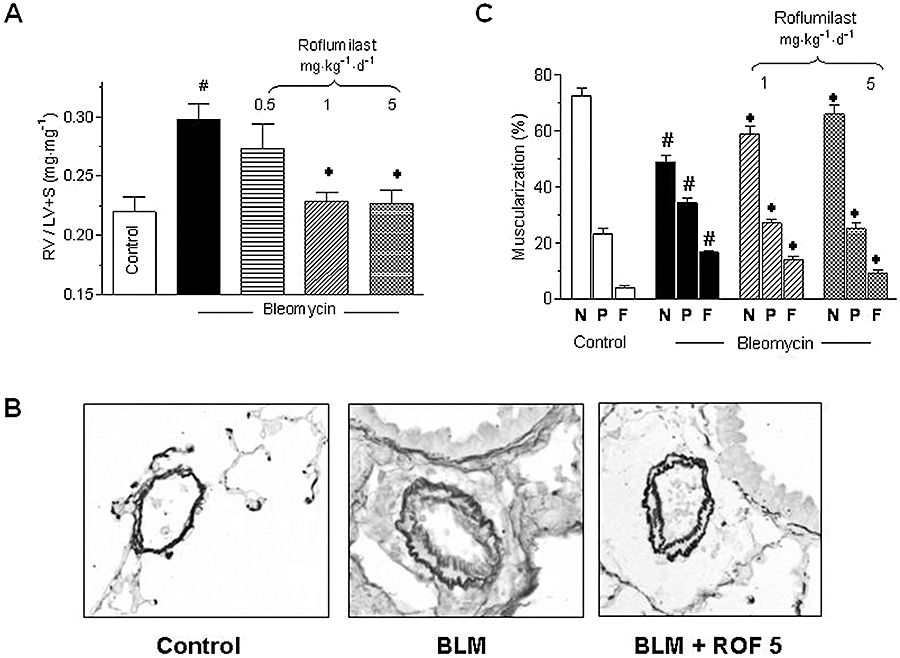

Right ventricular hypertrophy (RV/LV + S) and pulmonary vascular remodeling developed following bleomycin (Figure 2A–C). Roflumilast dose-dependently diminished the increase of the RV/LV + S ratio with a maximum effect at 1 mg·kg−1·d−1 (Figure 2A). In parallel, pulmonary artery media thickening (Figure 2B) and the proportion of fully muscularized intra-acinar pulmonary vessels (Figure 2C) was attenuated by the PDE4 inhibitor.

Figure 2.

Analysis of bleomycin-induced pulmonary vascular remodeling and right ventricular hypertrophy. Mice received a single dose of bleomycin (BLM; 3.75 U·kg−1) intratracheally at day 1 and roflumilast (ROF) was administered at 0.5, 1 or 5 mg·kg−1·d−1 p.o., once daily from day 1 to 14 until analysis in a preventive protocol. Right ventricular hypertrophy (expressed as RV/LV + S ratio) in A, histology of intra-acinar pulmonary arteries in B and, in C, the percentage of fully muscularized (F), partially muscularized (P) and non-muscularized (N) distal pulmonary vessels were determined, as described in Methods. #P < 0.05 versus control, *P < 0.05 versus bleomycin. Results are shown as mean ± SEM from nine to 10 (controls) or five to nine (bleomycin) mice (A) or three mice (C). LV + S, left ventricle + septum; RV, right ventricle.

Bleomycin increased BALF content of TNFα, IL-13 and TGFβ1 protein as well as TNFα, TGFβ1, CTGF, αI(I)collagen and endothelin-1 mRNA in lung extracts which was reduced by roflumilast (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effects of roflumilast on TNFα, IL-13, TGFβ, CTGF, αI(I)collagen and endothelin-1 (ET-1) expression following bleomycin in mice

|

TNFα |

IL-13 |

TGFβ |

CTGF |

αI(I)collagen |

ET-1 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA (lung) | Protein (BALF) | Protein (BALF) | mRNA (lung) | Protein (BALF) | mRNA (lung) | mRNA (lung) | mRNA (lung) | |

| Control | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 25.7 ± 6.8 | 4.4 ± 0.9 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 18.2 ± 10.9 | 1.1 ± 0.05 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.1 |

| BLM | 2.2 ± 0.2# | 76.8 ± 12.1# | 12.3 ± 1.4# | 6.2 ± 0.7# | 107.3 ± 18# | 4.6 ± 0.8# | 3.3 ± 0.7# | 4.1 ± 0.4# |

| BLM + ROF1 | 1.2 ± 0.2* | 45.4 ± 1.2* | 8.4 ± 1.0* | 3.8 ± 1* | 56 ± 16.5* | 2.3 ± 0.8* | 1.8 ± 0.4* | 2.2 ± 0.5* |

| BLM + ROF5 | 0.9 ± 0.4* | 40.9 ± 9* | 7.4 ± 1.3* | 2.7 ± 0.3* | 39 ± 10.1* | 1.5 ± 0.6* | 1.4 ± 0.2* | 2.0 ± 0.4* |

Roflumilast was administered at 1 or 5 mg·kg−1·d−1 (ROF1 or ROF5) p.o. from day 1 to 14 after intratracheal instillation of bleomycin (day 1, 3.75 U·kg−1) (preventive protocol). TNFα, IL-13 or TGFβ1 proteins were measured in BALF using ELISA. mRNA expression of TNFα, TGFβ1, CTGF, αI(I)collagen, ET-1 was measured in lung extracts by real-time quantitative PCR. Data shown are the means ± SEM of six (protein) or three to four (mRNA) animals. TNFα, IL-13 and TGFβ1 proteins are given in pg·mL−1, and mRNA as relative expression (i.e. x-fold change over control).

P < 0.05 from control;

P < 0.05 from bleomycin. Baseline expression remained unaffected by roflumilast (not shown).

CTGF, connective tissue growth factor; IL-13, interleukin-13; TGFβ, transforming growth factor-β; TNFα, tumour necrosis factor-α.

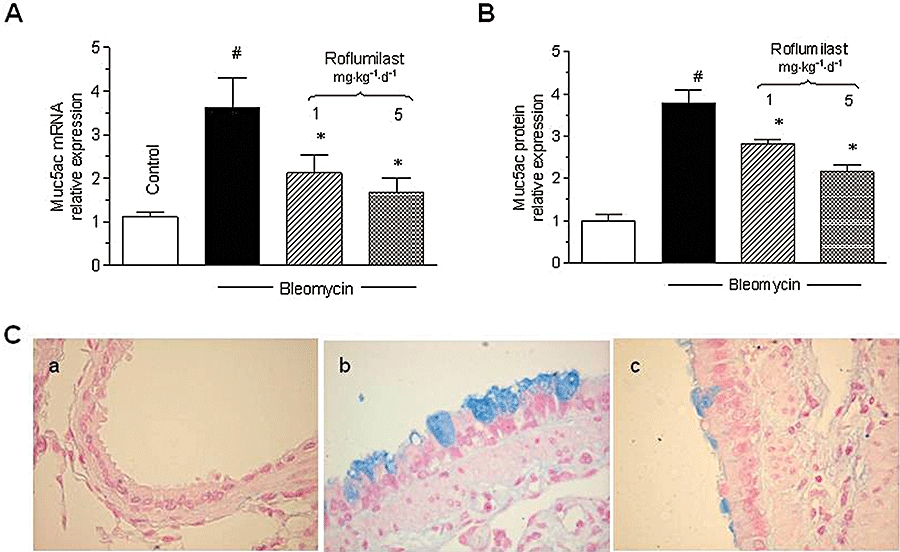

The mucin Muc5ac was elevated in lungs, following bleomycin. Roflumilast dose-dependently attenuated Muc5ac protein (BALF) and mRNA (lung) (Figure 3A,B). In parallel, the PDE4 inhibitor diminished the increased number of airway epithelial cells forming mucin proteins in lungs of mice, after bleomycin (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Effects of roflumilast on Muc5ac mRNA (lung), protein (BAL fluid) and mucin-forming cells. Mice received a single dose of bleomycin (3.75 U·kg−1) intratracheally at day 1 and roflumilast was given at 1 or 5 mg·kg−1·d−1 p.o. from day 1 to 14 (preventive protocol). Muc5ac mRNA in lung extracts (A) and protein in BAL fluid (B) was measured at day 14. Muc5ac mRNA or protein were quantified by real-time RT-PCR or ELISA and data were given as relative expression (i.e. x-fold change over control). Results are shown as mean ± SEM from four to five (mRNA) and six (protein) mice. #P < 0.05 versus control, *P < 0.05 versus bleomycin. Representative photomicrographs of airway epithelium stained with Alcian blue to detect mucus-forming cells were taken at day 14. Mucus producing cells are stained in blue, magnification was ×40. (a) control, (b) bleomycin, (c) bleomycin and roflumilast 5 mg·kg−1·d−1 (C). BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; RT-PCR, reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction.

Finally, we also found that a surrogate parameter of oxidative burden, accumulation of lipid hydroperoxides, in BALF was increased after bleomycin (3.7 ± 0.2 µmol·L−1 following bleomycin from 1.5 ± 0.2 µmol·L−1 in controls). Roflumilast attenuated this increased levels of lipid hydroperoxides to 3.1 ± 0.05 µmol·L−1 at 5 mg·kg−1·d−1 (P < 0.05; n = 3).

Bleomycin-induced lung injury in mice was paralleled by a loss in body weight of 2.9 ± 0.5 g from an initial mean body weight of about 20 g over the 14 day observation period while control mice gained weight (1.4 ± 0.2 g) within this time frame. Roflumilast-treated mice were partially protected from bleomycin-induced body weight loss (57% and 61% inhibition of body weight loss at 1 and 5 mg·kg−1·d−1 respectively; P < 0.05 versus bleomycin alone).

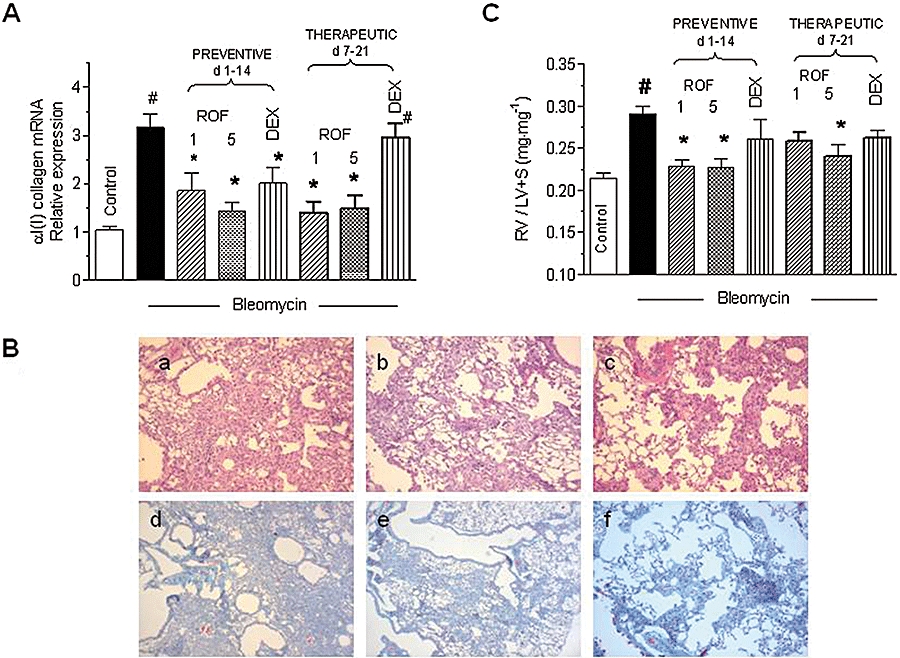

Effects of roflumilast and dexamethasone on bleomycin-induced lung fibrotic response in mice in a therapeutic versus a preventive protocol

The primary endpoint in these experiments was αI(I)collagen mRNA in lung extracts as a marker of the fibrotic response. In the preventive protocol, dexamethasone partly diminished the increased αI(I)collagen mRNA found after bleomycin to the same extent as that observed after roflumilast at 1 mg·kg−1·d−1. However, in the therapeutic protocol, dexamethasone was ineffective while roflumilast was still able to reduce αI(I)collagen mRNA (Figure 4A), collagen deposition (Figure 4B) and the Ashcroft fibrosis score (by 13% and 28% at 1 and 5 mg·kg−1·d−1, P < 0.05 for both dose levels).

Figure 4.

Comparison of roflumilast and dexamethasone on lung αI(I)collagen mRNA and right ventricular hypertrophy associated with bleomycin in a therapeutic protocol in mice. Mice received a single dose of intratracheal bleomycin (3.75 U·kg−1) at day 1, and roflumilast (ROF: 1 or 5 mg·kg−1·d−1 p.o.) or dexamethasone (DEX; 2.5 mg·kg−1·d−1 p.o.) either from day 1 to 14 with analyses at day 14 (preventive protocol) or from day 7 to 21 with analyses at day 21 (therapeutic protocol). αI(I)collagen was quantitated in lung extracts by real-time RT-PCR and data are given as relative expression levels (i.e. x-fold increase over control) (A). Lung histology shows H&E staining (original magnification ×40) in the upper panels (a–c) and Masson's trichrome (original magnification ×40; collagen is stained in blue) in the lower panels (d–f) for bleomycin (a,d), bleomycin + roflumilast 1 mg·kg−1·d−1 (b,e) and bleomycin + roflumilast 5 mg·kg−1·d−1 (c,f) with roflumilast from day 7 to 21 and analyses at day 21 (B). The RV/LV + S ratio was calculated as a measure of right ventricular hypertrophy (C). Results are given as the means ± SEM from three to five [αI(I)collagen] or nine (RV/LV + S) animals. #P < 0.05 versus control, *P < 0.05 versus bleomycin. LV + S, left ventricle + septum; RT-PCR, reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction; RV, right ventricle.

Roflumilast maintained its ability to decrease right ventricular hypertrophy in the therapeutic protocol while dexamethasone was not effective in either protocols (Figure 4C).

Comparison of roflumilast with methylprednisolone on the bleomycin-induced lung fibrotic response in rats in the therapeutic versus preventive protocol

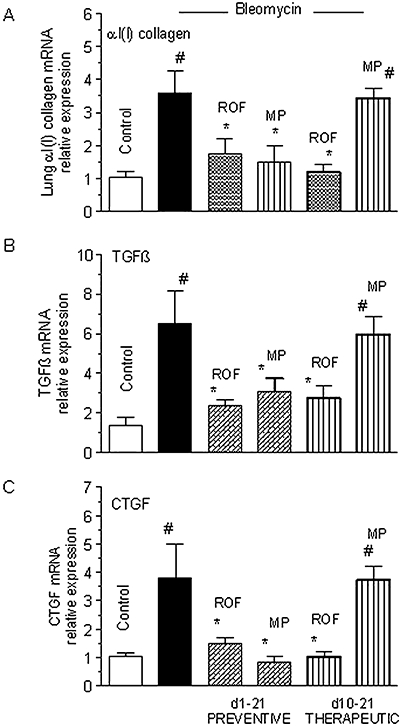

To confirm the differential findings with the PDE4 inhibitor compared with the glucocorticoid in the therapeutic versus the preventive protocol in another species, roflumilast (1 mg·kg−1·d−1 p.o.) and methylprednisolone (10 mg·kg−1·d−1 p.o.) were compared in rats. Again, αI(I)collagen mRNA in lung extracts served as the primary endpoint. An about 3.5-fold increase in αI(I)collagen mRNA was observed at day 21 following bleomycin that was markedly reduced by both roflumilast and methylprednisolone in the preventive protocol. On the other hand, only roflumilast but not methylprednisolone alleviated lung αI(I)collagen mRNA expression in the therapeutic protocol (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Comparison of roflumilast (ROF) and methylprednisolone (MP) on lung αI(I)collagen mRNA and right ventricular hypertrophy associated with bleomycin in a therapeutic protocol in rats. Wistar rats were exposed to a single intratracheal dose of bleomycin (7.5 U·kg−1) at day 1 and roflumilast (1 mg·kg−1·d−1 p.o.) or methylprednisolone (10 mg·kg−1·d−1 p.o.) was administered either from day 1 to 21 (preventive protocol) or from day 10 to 21 (therapeutic protocol). Lung extracts for determination of αI(I)collagen, TGFβ1 and CTGF mRNA by real-time RT-PCR were prepared at day 21. Results are shown as relative expression levels (x-fold increase over control) and given as mean ± SEM from six to eight animals per treatment group. #P < 0.05 versus control, *P < 0.05 versus bleomycin. CTGF, connective tissue growth factor; TGFβ1, transforming growth factor-β1; RT-PCR, reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction.

Furthermore, augmented expression of TGFβ1 and CTGF mRNA in lung extracts following bleomycin, was attenuated by roflumilast but not by methyprednisolone in the therapeutic protocol while both therapeutic treatments were equally effective in the preventive regimen (Figure 5B,C).

Discussion

A major novel finding from this study is that a PDE4 inhibitor, roflumilast, alleviated bleomycin-induced lung fibrotic responses in mice or rats in a preventive but also in a therapeutic protocol, thus discriminating between the effects of the PDE4 inhibitor and those of a glucocorticoid.

The early inflammatory response to intratracheal bleomycin instillation partly accounts for the subsequent development of the lung fibrotic response (Moeller et al., 2008; Moore and Hogaboam, 2008). Roflumilast reduced airway and pulmonary parenchymal inflammatory cell infiltrates following bleomycin instillation. These findings corroborate the anti-inflammatory potential of the PDE4 inhibitor demonstrated in diverse in vivo models (Bundschuh et al., 2001; Wollin et al., 2006; Le Quement et al., 2008; Weidenbach et al., 2008). Standard anti-inflammatory agents, i.e. glucocorticoids, were also shown to attenuate the inflammatory response in the bleomycin model (Koshika et al., 2005; Chaudhary et al., 2006). Roflumilast partly attenuated lung TNFα and IL-13 generation evoked by bleomycin, and with respect to TNFα, this observation is in agreement with a range of in vitro and in vivo investigations using different stimuli (Bundschuh et al., 2001; Hatzelmann and Schudt, 2001). Reduction of lung TNFα, IL-13 and inflammatory cell influx may explain some of the antifibrotic effects of the PDE4 inhibitor in the preventive protocol. Indeed, TNFα and IL-13 together induce TGFβ1, an acknowledged trigger of lung fibrosis, and strategies addressed against TNFα (e.g. a soluble TNF receptor or antibody) or an anti IL-13 antibody mitigate pulmonary fibrotic remodelling induced by bleomycin (Piguet et al., 1989; Belperio et al., 2002; Fichtner-Feigl et al., 2006).

Transforming growth factor-β1 triggers lung proliferation of fibroblasts and their expression of CTGF and collagen I. Roflumilast reduced not only the increased lung TGFβ1 formation after bleomycin instillation, but also CTGF and collagen I transcripts and collagen deposition in lung parenchyma. While all these effects may be secondary to an inhibition of the early inflammatory response, including TNFα and IL-13, it should be remembered that PDE4 inhibitors and in particular roflumilast, were shown to diminish various human lung fibroblast functions such as fibroblast-driven contraction of collagen gels, fibronectin-induced chemotaxis, proliferation, TGFβ1-induced expression of α-smooth muscle actin as surrogate of myofibroblast differentiation, CTGF, collagen I, fibronectin and the expression of ICAM-1 cell adhesion molecule in vitro (Kohyama et al., 2002; Boero et al., 2006; Dunkern et al., 2007; Klar et al., 2007). Further, proliferation of cultured lung fibroblasts obtained from C57Bl/6J mice was concentration-dependently attenuated by roflumilast with an IC50 of 4.9 nmol·L−1 and a maximum inhibition of 70–80% (our unpublished data).

Based on these observations, we then explored whether roflumilast maintained effective inhibition of the bleomycin-induced fibrotic response in a therapeutic protocol in mice. An anti-inflammatory glucocorticoid reduced bleomycin-induced lung αI(I)collagen expression under the preventive protocol but not in the therapeutic regime while roflumilast maintained its efficacy in both protocols. A similar outcome was reproduced in rats in which roflumilast was effective in the preventive and the therapeutic protocol in reducing lung TGFβ1, CTGF and αI(I)collagen expression while methylprednisolone, as previously reported (Chaudhary et al., 2006), was only effective in the preventive protocol. Essentially, this earlier report provides a rationale to dissect merely anti-inflammatory from additional antifibrotic effects by comparing effects of test compounds in the therapeutic versus the preventive administration protocol as used here, on the bleomycin-induced lung fibrotic response. Interestingly, the PDGFR/cAbl/ckit kinase inhibitor imatinib, an established anti-fibrotic agent, reduced lung αI(I)collagen and TGFβ1 transcripts in both preventive and therapeutic regimens while the effects of methylprednisolone were limited to the preventive protocol (Chaudhary et al., 2006). Taken together, it may be inferred that the PDE4 inhibitor, in addition to its well-established anti-inflammatory effects, might induce direct anti-fibrotic effects by inhibiting the pro-fibrotic machinery, specifically lung fibroblasts, in bleomycin-induced lung injury.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or interstitial lung diseases such as IPF are accompanied by pulmonary vascular remodelling, fostering the development of pulmonary hypertension, which obscures prognosis in these conditions. Bleomycin elicits pulmonary vascular remodeling, increase of pulmonary arterial pressure and right ventricular hypertrophy in rodents (Underwood et al., 2000; Ortiz et al., 2002; Hemnes et al., 2008). This study reveals that roflumilast alleviated right ventricular hypertrophy in mice in both preventive and therapeutic protocols, and decreased the muscularization of intraacinar pulmonary arteries following bleomycin (preventive protocol). These findings are corroborated by a recent report in which roflumilast was shown to mitigate monocrotaline- or chronic hypoxia-induced pulmonary vascular remodeling and to decrease an augmented pulmonary arterial pressure and right ventricular hypertrophy in rats in a preventive and therapeutic (monocrotaline) protocol (Izikki et al., 2007).

In the current study, bleomycin increased endothelin-1 expression in lung extracts in agreement with observations from others (Mutsaers et al., 1998), which was reduced by roflumilast. This together with the reported inhibition of pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell proliferation by PDE4 inhibitors (Growcott et al., 2006) may account in part for the reduction of bleomycin-induced pulmonary vascular remodelling by the PDE4 inhibitor. Finally, oxidative stress was recently suggested to support bleomycin-induced pulmonary hypertension (Hemnes et al., 2008). In the current study, an increased accumulation of lipid hydroperoxides in BALF following bleomycin was diminished by roflumilast. Thus, the mechanism by which roflumilast reduces bleomycin-induced pulmonary vascular remodelling and right ventricular hypertrophy may comprise direct inhibitory effects on pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell proliferation (putatively relevant in the therapeutic protocol), anti-inflammatory effects (as TNFα receptor deficient mice were resistant to bleomycin-induced pulmonary hypertension (Ortiz et al., 2002)) and reduction of oxidative stress.

Mucus overproduction represents a component of mucociliary malfunction in COPD or severe asthma with the (human) mucin MUC5AC being prominently expressed by the airway epithelium in these conditions (Caramori et al., 2004; Gensch et al., 2004; Morcillo and Cortijo, 2006; Kim et al., 2008). Here, in our experiments, bleomycin augmented lung mRNA and protein expression of (rodent) Muc5ac and increased the mucus-forming cells of the airway epithelial layer, reproducing earlier observations in rats (Mata et al., 2003). Roflumilast dose-dependently reduced bleomycin-induced lung Muc5ac formation and epithelial mucus-forming cells. Oxidative stress, generated in response to bleomycin, was shown to augment MUC5AC production in human bronchial epithelial cells in vitro, a process that may involve an activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (Takeyama et al., 2000). In rats, the anti-oxidant N-acetylcysteine decreased lung Muc5ac, upregulated following bleomycin (Mata et al., 2003). In the current study, roflumilast reduced lung oxidant burden associated with bleomycin in mice. Further, roflumilast and other PDE4 inhibitors diminished epidermal growth factor-induced MUC5AC expression in human airway epithelial cells in vitro (Mata et al., 2005). Another candidate capable of controlling airway epithelial Muc5ac production is IL-13 and, in our present work, this cytokine was increased with bleomycin and reduced with roflumilast. This cytokine was demonstrated to augment MUC5AC expression in airway epithelial cells in vitro and to promote differentiation of ciliated into goblet cells in vivo, and interestingly, was found at increased levels in lungs affected from COPD (Tyner et al., 2006; Zhen et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2008). Taken together, the inhibition by roflumilast of Muc5ac formation following bleomycin in mice may involve multiple pathways, such as reduction of lung oxidative stress or IL-13, but also a direct interference at the level of airway epithelial cells.

In summary, the PDE4 inhibitor roflumilast alleviates lung fibrotic remodelling following intratracheal bleomycin instillation in rodents, a widely used experimental model to identify drugs active in lung disorders associated with fibrosis. In this context roflumilast maintained its efficacy in a therapeutic protocol, where fibrosis remained resistant to anti-inflammatory glucocorticoids, indicating that the PDE4 inhibitor may directly address fibroblasts in vivo, concurring with analogous observations in vitro. Further studies are required to confirm this hypothesis and to determine its potential therapeutic value.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants SAF2005-00669 (JC) and SAF2006-01002 (EJM) of CICYT and grant CB06/06/0027 of CIBERES (Ministry of Science and Innovation and Health Institute ‘Carlos III’, Spanish Government), research grants from Regional Government (‘Generalitat Valenciana’), and Nycomed GmbH (Konstanz, Germany).

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- BALF

bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CTGF

connective tissue growth factor

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- IL-13

interleukin-13

- IPF/UIP

idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis/usual interstitial pneumonia

- LV + S

left ventricle + septum

- PDE4

phosphodiesterase 4

- RT-PCR

reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

- RV

right ventricle

- TGF

transforming growth factor

- TNF

tumour necrosis factor

Conflicts of interest

EJM and JC received a research grant from Nycomed GmbH. AH and HT are employees of Nycomed GmbH.

References

- Ashcroft T, Simpson JM, Timbrell V. Simple method of estimating severity of pulmonary fibrosis on a numerical scale. J Clin Pathol. 1988;41(4):467–470. doi: 10.1136/jcp.41.4.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belperio JA, Dy M, Burdick MD, Xue YY, Li K, Elias JA, et al. Interaction of IL-13 and C10 in the pathogenesis of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;27(4):419–427. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0009OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender AT, Beavo JA. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases: molecular regulation to clinical use. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58(3):488–520. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boero S, Silvestri M, Sabatini F, Nachira A, Rossi GA. Inhibition of human lung fibroblast functions by roflumilast N-oxide. Eur Respir J. 2006;662s:P3845. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- Boswell-Smith V, Page CP. Roflumilast: a phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor for the treatment of respiratory disease. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2006;15(9):1105–1113. doi: 10.1517/13543784.15.9.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bundschuh DS, Eltze M, Barsig J, Wollin L, Hatzelmann A, Beume R. In vivo efficacy in airway disease models of roflumilast, a novel orally active PDE4 inhibitor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;297(1):280–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caramori G, Di Gregorio C, Carlstedt I, Casolari P, Guzzinati I, Adcock IM, et al. Mucin expression in peripheral airways of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Histopathology. 2004;45(5):477–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2004.01952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary NI, Schnapp A, Park JE. Pharmacologic differentiation of inflammation and fibrosis in the rat bleomycin model. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173(7):769–776. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200505-717OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkern TR, Feurstein D, Rossi GA, Sabatini F, Hatzelmann A. Inhibition of TGF-beta induced lung fibroblast to myofibroblast conversion by phosphodiesterase inhibiting drugs and activators of soluble guanylyl cyclase. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;572:12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fichtner-Feigl S, Strober W, Kawakami K, Puri RK, Kitani A. IL-13 signaling through the IL-13alpha2 receptor is involved in induction of TGF-beta1 production and fibrosis. Nat Med. 2006;12(1):99–106. doi: 10.1038/nm1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gensch E, Gallup M, Sucher A, Li D, Gebremichael A, Lemjabbar H, et al. Tobacco smoke control of mucin production in lung cells requires oxygen radicals AP-1 and JNK. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(37):39085–39093. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406866200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grootendorst DC, Gauw SA, Verhoosel RM, Sterk PJ, Hospers JJ, Bredenbroker D, et al. Reduction in sputum neutrophil and eosinophil numbers by the PDE4 inhibitor roflumilast in patients with COPD. Thorax. 2007;62(12):1081–1087. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.075937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Growcott EJ, Spink KG, Ren X, Afzal S, Banner KH, Wharton J. Phosphodiesterase type 4 expression and anti-proliferative effects in human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Respir Res. 2006;7:9. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzelmann A, Schudt C. Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory potential of the novel PDE4 inhibitor roflumilast in vitro. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;297(1):267–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemnes AR, Zaiman A, Champion HC. PDE5A inhibition attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis and pulmonary hypertension through inhibition of ROS generation and RhoA/Rho kinase activation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;294(1):L24–L33. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00245.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohlfeld JM, Schoenfeld K, Lavae-Mokhtari M, Schaumann F, Mueller M, Bredenbroeker D, et al. Roflumilast attenuates pulmonary inflammation upon segmental endotoxin challenge in healthy subjects: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2008;21:616–623. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houslay MD, Schafer P, Zhang KY. Keynote review: phosphodiesterase-4 as a therapeutic target. Drug Discov Today. 2005;10(22):1503–1519. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03622-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izbicki G, Segel MJ, Christensen TG, Conner MW, Breuer R. Time course of bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis. Int J Exp Pathol. 2002;83(3):111–119. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2613.2002.00220.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izikki M, Adnot S, Zadigue P, Barlier Mur AM, Maitre B, Raffestin B, et al. Effect of roflumilast on hypoxia-and monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension in rats. Eur Respir J. 2007;294s:E1836. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- Keerthisingam CB, Jenkins RG, Harrison NK, Hernandez-Rodriguez NA, Booth H, Laurent GJ, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 deficiency results in a loss of the anti-proliferative response to transforming growth factor-beta in human fibrotic lung fibroblasts and promotes bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Am J Pathol. 2001;158(4):1411–1422. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64092-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EY, Battaile JT, Patel AC, You Y, Agapov E, Grayson MH, et al. Persistent activation of an innate immune response translates respiratory viral infection into chronic lung disease. Nat Med. 2008;14(6):633–640. doi: 10.1038/nm1770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klar J, Sabatini F, Schatton E, Burgbacher B, Rossi GA, Hatzelmann A, et al. Roflumilast N-oxide reduces human fibroblast function. Eur Respir J. 2007;544s:E3258. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- Kohyama T, Liu X, Wen FQ, Zhu YK, Wang H, Kim HJ, et al. PDE4 inhibitors attenuate fibroblast chemotaxis and contraction of native collagen gels. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;26(6):694–701. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.26.6.4743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshika T, Hirayama Y, Ohkubo Y, Mutoh S, Ishizaka A. Tacrolimus (FK506) has protective actions against murine bleomycin-induced acute lung injuries. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;515(1–3):169–178. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar RK, Herbert C, Thomas PS, Wollin L, Beume R, Yang M, et al. Inhibition of inflammation and remodeling by roflumilast and dexamethasone in murine chronic asthma. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;307(1):349–355. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.053819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Quement C, Guenon I, Gillon JY, Valenca S, Cayron-Elizondo V, Lagente V, et al. The selective MMP-12 inhibitor, AS111793 reduces airway inflammation in mice exposed to cigarette smoke. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154:1206–1215. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovgren AK, Jania LA, Hartney JM, Parsons KK, Audoly LP, Fitzgerald GA, et al. COX-2-derived prostacyclin protects against bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;291(2):L144–L156. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00492.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martorana PA, Beume R, Lucattelli M, Wollin L, Lungarella G. Roflumilast fully prevents emphysema in mice chronically exposed to cigarette smoke. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172(7):848–853. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200411-1549OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mata M, Ruiz A, Cerda M, Martinez-Losa M, Cortijo J, Santangelo F, et al. Oral N-acetylcysteine reduces bleomycin-induced lung damage and mucin Muc5ac expression in rats. Eur Respir J. 2003;22(6):900–905. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00018003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mata M, Sarria B, Buenestado A, Cortijo J, Cerda M, Morcillo EJ. Phosphodiesterase 4 inhibition decreases MUC5AC expression induced by epidermal growth factor in human airway epithelial cells. Thorax. 2005;60(2):144–152. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.025692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller A, Ask K, Warburton D, Gauldie J, Kolb M. The bleomycin animal model: a useful tool to investigate treatment options for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis? Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40(3):362–382. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore BB, Hogaboam CM. Murine models of pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;294(2):L152–L160. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00313.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morcillo EJ, Cortijo J. Mucus and MUC in asthma. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2006;12(1):1–6. doi: 10.1097/01.mcp.0000198064.27586.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutsaers SE, Foster ML, Chambers RC, Laurent GJ, McAnulty RJ. Increased endothelin-1 and its localization during the development of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in rats. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1998;18(5):611–619. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.18.5.2898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagome K, Dohi M, Okunishi K, Tanaka R, Miyazaki J, Yamamoto K. In vivo IL-10 gene delivery attenuates bleomycin induced pulmonary fibrosis by inhibiting the production and activation of TGF-beta in the lung. Thorax. 2006;61(10):886–894. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.056317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill CA, Giri SN, Wang Q, Perricone MA, Hyde DM. Effects of dibutyrylcyclic adenosine monophosphate on bleomycin-induced lung toxicity in hamsters. J Appl Toxicol. 1992;12(2):97–111. doi: 10.1002/jat.2550120206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz LA, Champion HC, Lasky JA, Gambelli F, Gozal E, Hoyle GW, et al. Enalapril protects mice from pulmonary hypertension by inhibiting TNF-mediated activation of NF-kappaB and AP-1. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;282(6):L1209–L1221. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00144.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piguet PF, Collart MA, Grau GE, Kapanci Y, Vassalli P. Tumor necrosis factor/cachectin plays a key role in bleomycin-induced pneumopathy and fibrosis. J Exp Med. 1989;170(3):655–663. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.3.655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz MJ, Cortijo J, Morcillo EJ. PDE4 inhibitors as new anti-inflammatory drugs: effects on cell trafficking and cell adhesion molecules expression. Pharmacol Ther. 2005;106:269–297. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schermuly RT, Dony E, Ghofrani HA, Pullamsetti S, Savai R, Roth M, et al. Reversal of experimental pulmonary hypertension by PDGF inhibition. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(10):2811–2821. doi: 10.1172/JCI24838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Mollar A, Closa D, Cortijo J, Morcillo EJ, Prats N, Gironella M, et al. P-selectin upregulation in bleomycin induced lung injury in rats: effect of N-acetyl-L-cysteine. Thorax. 2002;57(7):629–634. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.7.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeyama K, Dabbagh K, Jeong Shim J, Dao-Pick T, Ueki IF, Nadel JA. Oxidative stress causes mucin synthesis via transactivation of epidermal growth factor receptor: role of neutrophils. J Immunol. 2000;164(3):1546–1552. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.3.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyner JW, Kim EY, Ide K, Pelletier MR, Roswit WT, Morton JD, et al. Blocking airway mucous cell metaplasia by inhibiting EGFR antiapoptosis and IL-13 transdifferentiation signals. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(2):309–321. doi: 10.1172/JCI25167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood DC, Osborn RR, Bochnowicz S, Webb EF, Rieman DJ, Lee JC, et al. SB239063, a p38 MAPK inhibitor, reduces neutrophilia, inflammatory cytokines, MMP-9, and fibrosis in lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;279(5):L895–L902. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.5.L895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidenbach A, Braun C, Schwoebel F, Beume R, Marx D. Therapeutic effect of various PDE4 inhibitors on cigarette smoke-induced pulmonary neutrophilia in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:A652. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- Wollin L, Bundschuh DS, Wohlsen A, Marx D, Beume R. Inhibition of airway hyperresponsiveness and pulmonary inflammation by roflumilast and other PDE4 inhibitors. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2006;19(5):343–352. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhen G, Park SW, Nguyenvu LT, Rodriguez MW, Barbeau R, Paquet AC, et al. IL-13 and epidermal growth factor receptor have critical but distinct roles in epithelial cell mucin production. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;36(2):244–253. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0180OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]