Abstract

Background and purpose

β1- and β2-adrenoceptors coexist in rat heart but β2-adrenoceptor-mediated inotropic effects are hardly detectable, possibly due to phosphodiesterase (PDE) activity. We investigated the influence of the PDE3 inhibitor cilostamide (300 nmol·L−1) and the PDE4 inhibitor rolipram (1 µmol·L−1) on the effects of (−)-catecholamines.

Experimental approach

Cardiostimulation evoked by (−)-noradrenaline (ICI118551 present) and (−)-adrenaline (CGP20712A present) through β1- and β2-adrenoceptors, respectively, was compared on sinoatrial beating rate, left atrial and ventricular contractile force in isolated tissues from Wistar rats. L-type Ca2+-current (ICa-L) was assessed with whole-cell patch clamp.

Key results

Rolipram caused sinoatrial tachycardia. Cilostamide and rolipram did not enhance chronotropic potencies of (−)-noradrenaline and (−)-adrenaline. Rolipram but not cilostamide potentiated atrial and ventricular inotropic effects of (−)-noradrenaline. Cilostamide potentiated the ventricular effects of (−)-adrenaline but not of (−)-noradrenaline. Concurrent cilostamide + rolipram uncovered left atrial effects of (−)-adrenaline. Both rolipram and cilostamide augmented the (−)-noradrenaline (1 µmol·L−1) evoked increase in ICa-L. (−)-Adrenaline (10 µmol·L−1) increased ICa-L only in the presence of cilostamide but not rolipram.

Conclusions and implications

PDE4 blunts the β1-adrenoceptor-mediated inotropic effects. PDE4 reduces basal sinoatrial rate in a compartment distinct from compartments controlled by β1- and β2-adrenoceptors. PDE3 and PDE4 jointly prevent left atrial β2-adrenoceptor-mediated inotropy. Both PDE3 and PDE4 reduce ICa-L responses through β1-adrenoceptors but the PDE3 component is unrelated to inotropy. PDE3 blunts both ventricular inotropic and ICa-L responses through β2-adrenoceptors.

Keywords: phosphodiesterases, rat atrium, sinoatrial node, ventricle, β1- and β2-adrenoceptors, (−)-adrenaline, (−)-noradrenaline, calcium current

Introduction

Activation of the sympathetic nervous system causes cardiostimulation through release of catecholamines. (−)-Noradrenaline and (−)-adrenaline increase rate and force of the mammalian heart through coexisting β1- and β2-adrenoceptors (receptor nomenclature follows Alexander et al., 2008) coupled to cAMP-dependent pathways. However, access of cAMP to effectors is different for cardiac β1-adrenoceptors and β2-adrenoceptors (Xiao et al., 1995; Kuschel et al., 1999) possibly due in part to involvement of different phosphodiesterases (PDEs). Hydrolysis of cAMP by PDEs protects the heart against overstimulation by sympathetic nerves but there are differences between β-adrenoceptor subtypes. Several PDE isoenzymes modulate catecholamine-evoked cardiostimulation (Fischmeister et al., 2006; Nikolaev et al., 2006). In the rat ventricle, PDE activity is mostly due to PDE3 and PDE4 (Mongillo et al., 2004; Rochais et al., 2004; Rochais et al., 2006). Rochais et al. (2006) investigated the effects of PDE inhibitors on the relationship between (−)-isoprenaline-evoked increases of subsarcolemmal cAMP (monitored from cyclic nucleotide-gated channels used as biosensors) and L-type Ca2+ current, ICa-L, mediated through β1- and β2-adrenoceptors of rat ventricular myocytes. (−)-Isoprenaline increased myocytic cAMP through both β1- and β2-adrenoceptors and these effects were markedly potentiated by the non-selective PDE inhibitor 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX). However, (−)-isoprenaline increased subsarcolemmal cAMP only through β1- but not β2-adrenoceptors. Inhibition of PDE3 or PDE4 caused robust enhancement of the β1AR-mediated subsarcolemmal cAMP increase. Although inhibition of either PDE3 or PDE4 uncovers transient subsarcolemmal cAMP increases through β2-adrenoceptors, only the concomitant inhibition of PDE3 and PDE4 caused stable increases of cAMP through these receptors. Comparable results were reported with ICa-L measurements. (−)-Isoprenaline-evoked increases in ICa-L through β1- or β2-adrenoceptors are enhanced by inhibition of PDE3 or PDE4. Taken together, the work of Rochais et al. (2006) illustrates differences and similarities of PDE-evoked modulation of the function of β1- and β2-adrenoceptors in a microdomain of rat ventricular cell membranes. How do these β1- and β2-adrenoceptor-mediated events in the membrane microdomain translate into increased ventricular contractility? How do PDEs modulate β1- and β2 adrenoceptor activity in non-ventricular cardiac regions of the rat?

Although β1- and β2-adrenoceptors coexist in the sinoatrial node (Saito et al., 1989), left atrium (Juberg et al., 1985) and ventricles (Minneman et al., 1979) of the rat heart, the cardiostimulant function of β1- but not β2-adrenoceptors is well accepted. There is no evidence for an inotropic function of β2-adrenoceptors in left atrium (Juberg et al., 1985) and (−)-adrenaline only causes modest tachycardia through rat sinoatrial β2-adrenoceptors, compared with β1-adrenoceptor-mediated tachycardia (Kaumann, 1986). The situation in ventricle is particularly complex, apparently because coupling of rat β2-adrenoceptors to Pertussis toxin (PTX)-sensitive Gi protein was reported to prevent Gs protein-mediated increases in Ca2+ transients and myocyte contractions and relaxations through these receptors (Xiao et al., 1995). However, others failed to detect β2-adrenoceptor-mediated increases in ICa-L and Ca2+ transients after PTX pre-treatment in rat ventricular myocytes (LaFlamme and Becker, 1998). Another possible reason for the subdued functional expression of rat cardiac β2-adrenoceptor activity could be a nearly complete hydrolysis of otherwise cardiostimulant cAMP by PDEs, particularly PDE3 and PDE4.

We therefore sought to investigate the β2-adrenoceptor-mediated effects of (−)-adrenaline on sinoatrial node, left atrium and ventricle under conditions of inhibition of PDE3 and PDE4 with cilostamide and rolipram, respectively, and compare the influence of the PDE inhibitors on the effects of (−)-noradrenaline, mediated through β1-adrenoceptors (Vargas et al., 2006). To better understand the link between PDE-controlled cAMP in the ICa-L domain and contractility events, the influence of the effects of cilostamide and rolipram on β1-adrenoceptors- and β2-adrenoceptor-mediated increases in ICa-L was compared in ventricular and atrial myocytes.

Methods

Isolated tissue experiments

Rats were killed following protocols approved by the Regierungspräsident Dresden, (permit number: 24D-9168.24-1/2007-17), in accordance with the guidelines of the European Community. Male Wistar rats (10–12 weeks old, ∼200 g weight) were anaesthetized with O2 30%/CO2 70% and killed with pure CO2. The hearts were dissected and placed in oxygenated, modified Tyrode's solution at room temperature containing (mmol·L−1): NaCl 126.9, KCl 5.4, CaCl2 1.8, MgCl2 1.05, NaHCO3 22, NaH2PO4 0.45, EDTA 0.04, ascorbic acid 0.2, pyruvate 5 and glucose 5.0. The pH of the solution was maintained at pH 7.4 by bubbling a mixture of 5% CO2 and 95% O2. Spontaneously beating right atria, left atria and the free wall of the right ventricle as well as left ventricular papillary muscles were rapidly dissected, mounted in pairs and attached to Swema 4–45 strain gauge transducers in an apparatus containing the modified Tyrode's solution at 37°C. Left atria, right ventricular walls and left ventricular papillary muscles were paced at 1 Hz and stretched as described (Kaumann and Molenaar, 1996; Oostendorp and Kaumann, 2000; Vargas et al., 2006). Contractile force was recorded through PowerLab amplifiers on a Chart for Windows, version 5.0 recording programme (ADInstruments, Castle Hill, NSW, Australia).

All tissues were exposed to phenoxybenzamine (5 µmol·L−1) for 90 min followed by washout, to irreversibly block α-adrenoceptors and tissue uptake of the catecholamines (Gille et al., 1985; Heubach et al., 2002). Experiments with (−)-noradrenaline were carried out in the presence of ICI118551 (50 nmol·L−1) to block β2-adrenoceptors. Experiments with (−)-adrenaline were carried out in the presence of CGP20712A (300 nmol·L−1) to selectively block β1-adrenoceptors and conceivably uncover CGP20712A-resistant effects, mediated through β2-adrenoceptors (Kaumann, 1986; Oostendorp and Kaumann, 2000; Heubach et al., 2002). To corroborate that CGP20712A-resistant effects of (−)-adrenaline were mediated through β2-adrenoceptors, the β2-adrenoceptor-selective antagonist ICI118551 (50 nmol·L−1) (Kaumann, 1986; Oostendorp and Kaumann, 2000) was used in the presence of CGP20712A.

Cumulative concentration-effect curves for the catecholamines were carried out in the absence and presence of the PDE3 inhibitor cilostamide (300 nmol·L−1) or PDE4 inhibitor rolipram (1 µmol·L−1) (Vargas et al., 2006), followed by the administration of a saturating concentration of (−)-isoprenaline (200 µmol·L−1). With 300 nmol·L−1 cilostamide approximately 86% of PDE3 and <0.4% of PDE4 would be inhibited; with 1 µmol·L−1 rolipram approximately 50% of PDE4 and 0.4% of PDE3 would be inhibited (see Vargas et al., 2006). For inotropic studies, the experiments were terminated by elevating the CaCl2 concentration to 8 mmol·L−1. The (−)-catecholamines caused, on occasion, ventricular arrhythmias. Positive inotropic effects of (−)-catecholamines were only measured from non-arrhythmic ventricular preparations or during periods of stable non-arrhythmic contractions. Times to peak force and to half-maximal relaxation (t1/2) were obtained fromfast speed tracings using ChartPro for Windows version 5.51 analysis programme (ADInstruments, Castle Hill, NSW, Australia).

Measurements of ICa-L

Ventricular and atrial myocytes of male rats were enzymatically dissociated as described earlier (Christ et al., 2001). Myocytes were stored at room temperature until use in a solution containing (mmol·L−1): NaCl 100, KCl 10, KH2PO4 1.2, CaCl2 0.5, MgSO4 5, taurine 50, MOPS 5 and glucose 50, pH 7.4. The single electrode patch clamp technique was used to measure ICa-L at 37°C (Christ et al., 2006a). Holding potential was −80 mV. K+ currents were blocked by replacing K+ with Cs+. The external perfusing solution contained (mmol·L−1): tetraethylammonium 120, CsCl 10, HEPES 10, CaCl2 2, MgCl2 1 and glucose 20 with pH adjusted with CsOH. The pipette solution contained (mmol·L−1): Cs methanesulphonate 90, CsCl 20, HEPES 10, Mg-ATP 4, Tris-GTP 0.4, EGTA 10 and CaCl2 3 with a calculated free Ca2+ concentration of 60 nmol·L−1 (EQCAL, Biosoft, Cambridge, UK) and pH 7.2, adjusted with CsOH. Current amplitude was determined as the difference between peak inward current and current at the end of the 200 ms depolarizing step to +10 mV. The effects of catecholamines on ICa-L were expressed in per cent of control (Christ et al., 2006a). To minimize the effects of desensitization, myocytes were exposed only to one concentration of catecholamine.

Statistics

−Log EC50M values of the catecholamines were estimated from fitting a Hill function with variable slopes to concentration-effect curves of catecholamines from individual experiments. To decide whether a model of one or two receptor populations could be used to fit concentration-effect curves, we used the extra sum-off squares F test with P < 0.05 to reject the hypothesis of one receptor population. Data from tissue and myocyte experiments were expressed as mean ± SEM of n = number of mice or number of myocytes (from ≥3 rats) respectively. Significance of differences between means was assessed with paired and unpaired Student's t-test using GraphPad 5 Software Inc. (San Diego, CA).

Drugs

CGP20712A was from Novartis (Basel, Switzerland). ICI118551 was from Tocris (Bristol, UK); (−)-adrenaline, (−)-isoprenaline, rolipram, phenoxybenzamine, isobutyl-methylxanthine (IBMX), Erythro-9-[2-Hydroxy-3-nonyl] adenine (EHNA), cilostamide and PTX were from Sigma (Poole Dorset, UK).

Results

Rolipram but not cilostamide increases sinoatrial rate

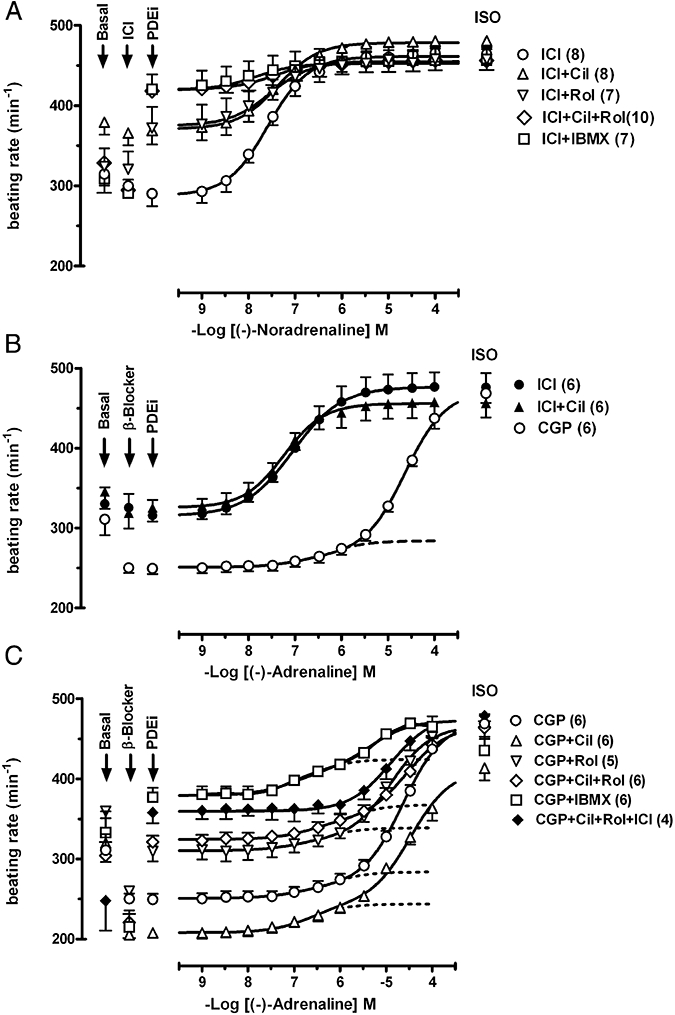

Mean beating rate was 234 ± 5 beats min−1 (n = 52) and 314 ± 9 beats min−1 (n = 45) in the presence of CGP20712A and ICI118551 respectively. CGP20712A caused bradycardia (Fig. 1C) but ICI118551 did not significantly change sinoatrial rate (Fig. 1A,B). An average decrease of 12 ± 5 beats min−1 by ICI118551 (n = 45 pooled data) was not significantly different from spontaneous rate decrease in time-matched controls (16 ± 3 beats min−1, n = 8). The CGP20712A-evoked bradycardia (Fig. 1A) was also reported in mouse heart (Heubach et al., 2002; Galindo-Tovar and Kaumann, 2008) and could be related to inverse agonism or blockade of β-adrenoceptors activated by traces of endogenously released noradrenaline. Cilostamide did not significantly modify sinoatrial beating rate in the presence of ICI118551 (P = 0.26, n = 8) or CGP20712A (P = 0.29, n = 6) (Fig. 1A,C). Rolipram increased sinoatrial rate by 37.3 ± 6.0% of the effect of 200 µmol·L−1 (−)-isoprenaline (P < 0.01, n = 5) and 24.4 ± 7.5% (P = 0.035, n = 6) in the presence of ICI118551 (Fig. 1A,B) or CGP20712A (Fig. 1C) respectively. The combination of cilostamide + rolipram increased beating rate by 59.8 ± 7.4% (P < 0.002, n = 10) and 43.9 ± 3.7% (P < 0.001, n = 6) in the presence of ICI118551 (Fig. 1A) and CGP20712A (Fig. 1C) respectively. The increase of sinoatrial rate by the combination of cilostamide + rolipram was significantly greater from that by rolipram alone in the presence of ICI118551 (P < 0.04) or CGP20712A (P < 0.05). IBMX (100 µmol·L−1) in the presence of CGP20712A increased sinoatrial rate by 94 ± 2% of (−)-isoprenaline (n = 4, not shown), precluding analysis of experiments with (−)-adrenaline under these conditions.

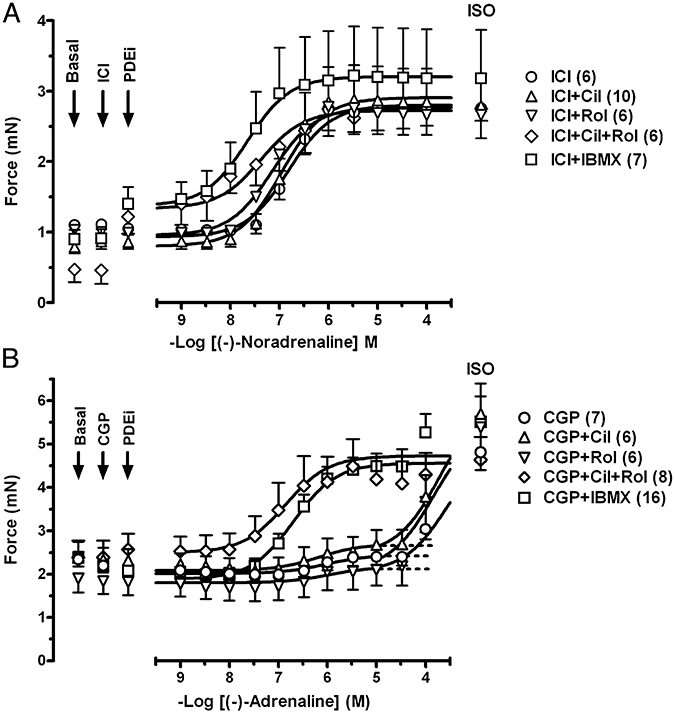

Figure 1.

The influence of cilostamide (300 nmol·L−1, Cil), rolipram (1 µmol·L−1, Rol) and IBMX (10 µmol·L−1) on the sinoatrial tachycardia elicited by (−)-noradrenaline through β1-adrenoceptors and (−)-adrenaline through β2-adrenoceptors. (A) Lack of potentiation of the positive chronotropic effects of (−)-noradrenaline by PDE inhibitors in the presence of ICI118551 (50 nmol·L−1, ICI). (B) Effects of (−)-adrenaline mediated through β1-adrenoceptors in the presence of ICI118551 and through both β1- and β2-adrenoceptors in the presence of CGP20712A (300 nmol·L−1, CGP). Lack of potentiation of the effects of (−)-adrenaline by cilostamide in the presence of ICI118551. (C) Lack of potentiation of the effects of (−)-adrenaline by cilostamide, rolipram and IBMX through β2-adrenoceptors in the presence of CGP20712A. Blockade by ICI118551 of the β2-adrenoceptor-mediated tachycardia of (−)-adrenaline in the presence of both cilostamide and rolipram (see also Fig. 2A). Fits of some biphasic curves were constrained by using the effect of (−)-isoprenaline as maximum. Broken lines in (B) and (C) depict a small β2-adrenoceptor-mediated chronotropic component. Means ± SEM, numbers of right atria are given in parenthesis. ISO, (−)-isoprenaline (200 µmol·L−1); PDEi, PDE inhibitor.

Cilostamide and rolipram fail to affect the chronotropic potency of catecholamines at sinoatrial β1- and β2-adrenoceptors

Neither cilostamide nor rolipram, administered separately or in combination, or IBMX (10 µmol·L−1) significantly altered the chronotropic potency of (−)-noradrenaline in the presence of ICI118551 (Fig. 1A, Table 1). (−)-Adrenaline in the presence of ICI118551 increased sinoatrial rate with –logEC50 = 7.11 ± 0.07 (n = 6) through β1-adrenoceptors (Fig. 1B). Cilostamide did not affect the potency of (−)-adrenaline in the presence of ICI118551 (−logEC50 = 7.10 ± 0.10, Fig. 1B).

Table 1.

Cardiostimulant potencies (−logEC50)

| (−)-Noradrenaline (ICI118551 50 nmol·L−1) |

β1 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | −LogEC50 | |||

| Right atrium (sinus rate) | ||||

| Control | 8 | 7.64 ± 0.07 | ||

| Rolipram | 7 | 7.47 ± 0.13 | ||

| Cilostamide | 8 | 7.43 ± 0.09 | ||

| Rolipram + cilostamide | 10 | 7.51 ± 0.09 | ||

| IBMX (10 µmol·L−1) | 7 | 7.73 ± 0.13 | ||

| Left atrium (contractile force) | ||||

| Control | 9 | 7.69 ± 0.06 | ||

| Rolipram | 7 | 8.75 ± 0.06** | ||

| Cilostamide | 8 | 7.89 ± 0.09 | ||

| Rolipram + cilostamide | 8 | not determined | ||

| IBMX (10 µmol·L−1) | 6 | 8.41 ± 0.12** | ||

| Right ventricle (contractile force) | ||||

| Control | 6 | 6.88 ± 0.02 | ||

| Rolipram | 5 | 7.18 ± 0.10* | ||

| Cilostamide | 7 | 7.06 ± 0.13 | ||

| Rolipram + cilostamide | 5 | 7.91 ± 0.04** | ||

| IBMX (10 µmol·L−1) | 8 | 7.81 ± 0.08** | ||

| Left ventricular papillary muscle (contractile force) | ||||

| Control | 6 | 6.79 ± 0.03 | ||

| Rolipram | 6 | 7.06 ± 0.10* | ||

| Cilostamide | 10 | 6.91 ± 0.05 | ||

| Rolipram + cilostamide | 6 | 7.32 ± 0.13** | ||

| IBMX (10 µmol·L−1) | 7 | 7.61 ± 0.10* | ||

| (−)-Adrenaline (CGP20712A 300 nmol·L−1) | n | β1−LogEC50 | β2−LogEC50 | f2 |

| Right atrium (sinus rate) | ||||

| Control | 6 | 6.68 ± 0.17 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | |

| Rolipram | 5 | 6.67 ± 0.26 | 0.07 ± 0.03 | |

| Cilostamide | 6 | 6.89 ± 0.14 | 0.16 ± 0.03* | |

| Rolipram + cilostamide | 6 | 7.01 ± 0.25 | 0.23 ± 0.07* | |

| IBMX (10 µmol·L−1) | 6 | 6.90 ± 0.13 | 0.30 ± 0.07* | |

| Left atrium (contractile force) | ||||

| Control | 8 | 4.27 ± 0.04 | ||

| Rolipram | 8 | 5.10 ± 0.09** | ||

| Cilostamide | 6 | 4.62 ± 0.08** | ||

| Rolipram + cilostamide | 10 | 5.96 ± 0.11** | 8.17 ± 0.08 | 0.26 ± 0.02 |

| IBMX (10 µmol·L−1) | 7 | 5.23 ± 0.09** | ||

| IBMX (30 µmol·L−1) | 5 | 5.53 ± 0.16** | 7.02 ± 0.08 | 0.25 ± 0.09 |

| Right ventricle (contractile force) | ||||

| Control | 7 | 6.09 ± 0.08 | 0.09 ± 0.07 | |

| Rolipram | 6 | 6.15 ± 0.18 | 0.07 ± 0.03 | |

| Cilostamide | 6 | 6.48 ± 0.08* | 0.15 ± 0.02* | |

| Rolipram + cilostamide | 8 | 6.83 ± 0.12* | 0.92 ± 0.03** | |

| IBMX (10 µmol·L−1) | 16 | 6.62 ± 0.09* | 0.84 ± 0.09** | |

| IBMX (100 µmol·L−1) | 4 | 6.81 ± 0.16 | 0.99 ± 0.01** | |

| Left ventricular papillary muscle (contractile force) | ||||

| Control | 4 | 6.05 ± 0.2 | 0.06 ± 0.03 | |

| Rolipram | 4 | 6.06 ± 0.10 | 0.08 ± 0.04 | |

| Cilostamide | 10 | 6.44 ± 0.11* | 0.17 ± 0.05 | |

| Rolipram + cilostamide | 5 | 6.84 ± 0.08** | 0.98 ± 0.03** | |

| IBMX (10 µmol·L−1) | 7 | 6.54 ± 0.10* | 0.82 ± 0.04** | |

| IBMX (100 µmol·L−1) | 4 | 6.91 ± 0.12* | 1.01 ± 0.04** | |

P values compared with control.

P < 0.05

P < 0.001.

As described before (Kaumann, 1986), the concentration-effect curves of (−)-adrenaline were biphasic in the presence of CGP20712A with a high-potency, CGP20712A-resistant component and low-potency, CGP20712A-sensitive component. Low (−)-adrenaline concentrations produced a very small increase of sinoatrial rate, mediated through β2-adrenoceptors, while high concentrations partially surmounted the blockade of β1-adrenoceptors caused by CGP20712A (Fig. 1B,C, Table 1). The PDE inhibitors neither alone or in combination did not affect the potency of (−)-adrenaline for β2-adrenoceptor-mediated chronotropic effects (Table 1). However, the fraction of the chronotropic effect mediated via β2-adrenoceptors (f2) was markedly enhanced by cilostamide, cilostamide + rolipram and IBMX (Fig. 1C, Table 1). The CGP20712A-resistant component f2 was completely antagonized by ICI118551, as demonstrated for the combination of cilostamide and rolipram (Figs 1C and 2a), consistent with mediation through β2-adrenoceptors.

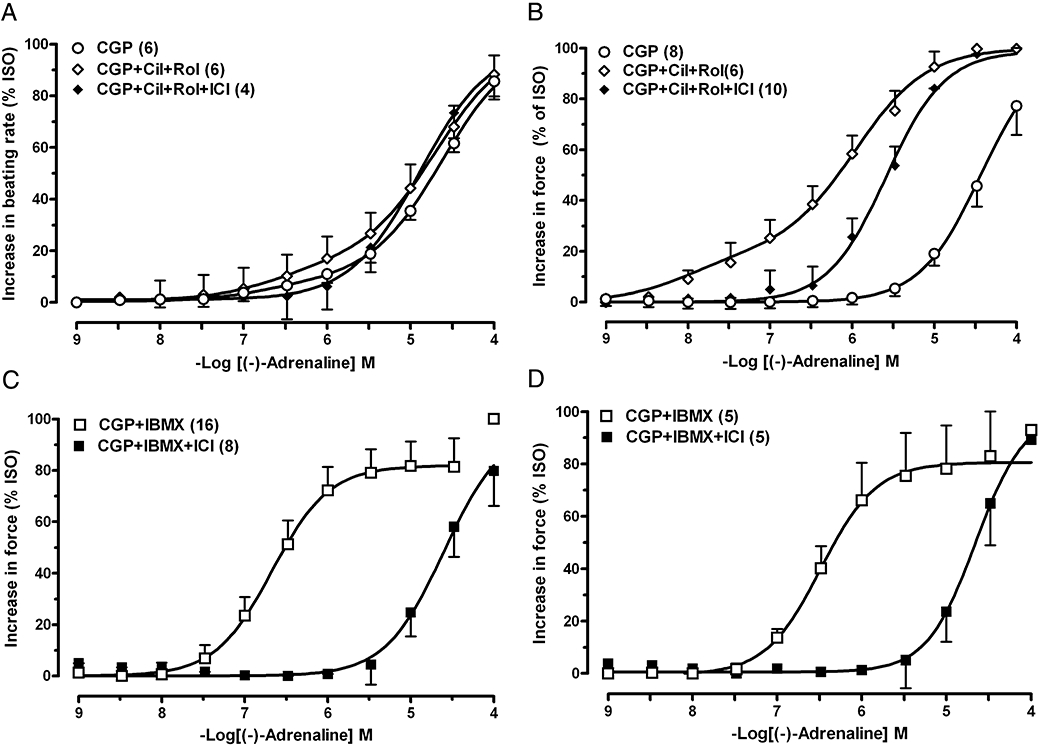

Figure 2.

Comparison of the β2-adrenoceptor-mediated effects of (−)-adrenaline in the presence of CGP20712A (CGP) and the inhibition of both PDE3 and PDE4 in four cardiac regions. Antagonism by ICI118551 (ICI). (A) Sinoatrial tachycardia. (B) Positive inotropic effects on left atrium. (C) Positive inotropic effects on free right ventricular wall. (D) Positive inotropic effects on left ventricular papillary muscle. For further details see Figure 1. Cil, cilostamide; Rol, rolipram.

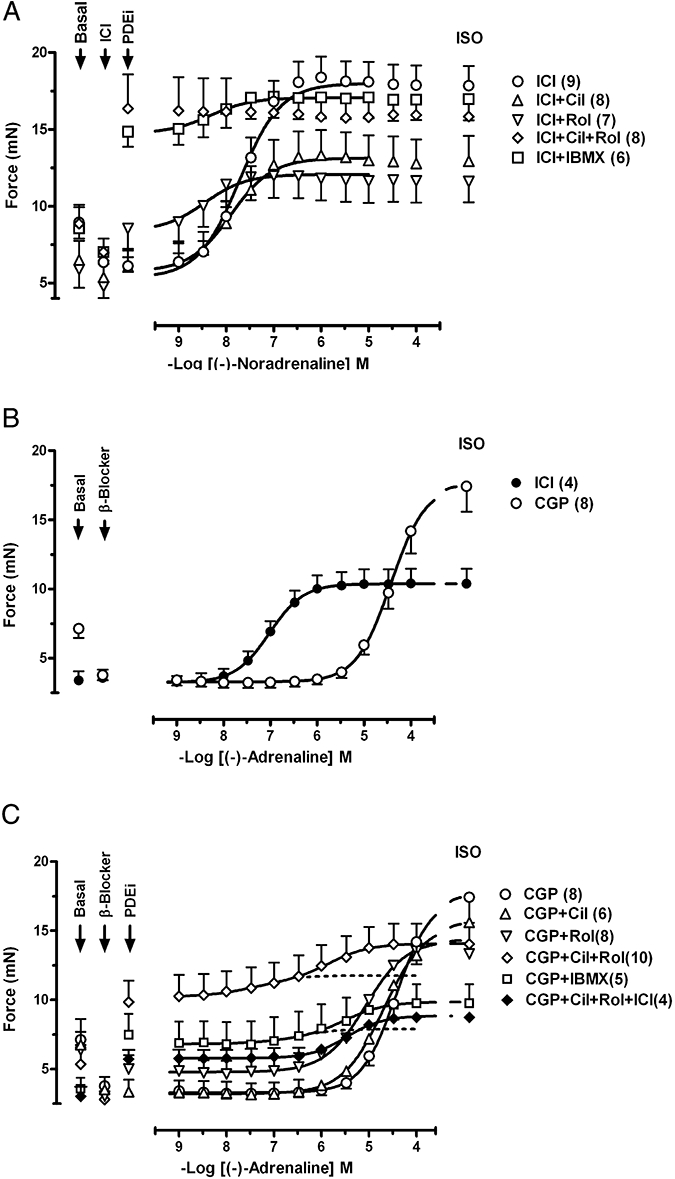

Effects of PDE inhibitors on left atrial contractile force

Mean contractile force was 2.8 ± 0.3 mN (n = 58) and 5.9 ± 0.3 mN (n = 44) in the presence of CGP20712A and ICI118551 respectively. Cilostamide did not significantly enhance contractile force. Rolipram and IBMX (10 µmol·L−1) increased contractile force in the presence of ICI118551 by 56.4 ± 7.9% (P = 0.001, n = 7) and 80.5 ± 3.5% (P < 0.001, n = 6) of (−)-isoprenaline respectively (Fig. 3A). In the presence of CGP20712A rolipram, IBMX 10, 30 and 100 µmol·L−1 increased contractile force by 20.6 ± 6.0% (P < 0.01, n = 8), 23.6 ± 3.1% (P < 0.02, n = 6), 65.9 ± 5.5% (P < 0.001, n = 8) (Fig. 3C) and 108 ± 2% (P < 0.001, n = 4, not shown) respectively. The increases in contractile force by rolipram and IBMX (10 µmol·L−1) in the presence of CGP20712A were significantly smaller (P = 0.05 and P < 0.001 respectively) than in the presence of ICI118551. The combination of cilostamide + rolipram increased contractile force significantly more (P = 0.03) in the presence of ICI118551 (105 ± 1% of (−)-isoprenaline, P < 0.001, n = 8, Fig. 3A) than in the presence of CGP20712A (61.2 ± 5.2%, P < 0.001, n = 8, Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

The influence of PDE inhibitors on the positive inotropic effects of (−)-noradrenaline through β1-adrenoceptors and (−)-adrenaline through β2-adrenoceptors on left atrium. (A) Potentiation of the effects of (−)-noradrenaline by rolipram (Rol), concurrent rolipram + cilostamide and IBMX (10 µmol·L−1) but not by cilostamide (Cil) alone. (B) Effects of (−)-adrenaline mediated through β1-adrenoceptors in the presence of ICI118551 (ICI) and antagonism by CGP20712A (CGP). (C) Unmasking of functional β2-adrenoceptors by concurrent cilostamide + rolipram or IBMX (30 µmol·L−1) and antagonism by ICI118551. Fits of some biphasic curves were constrained by using the effect of (−)-isoprenaline as maximum. For further details see legend to Figure 1. Error bars are omitted in the range of curve overlap.

Rolipram and IBMX but not cilostamide potentiate the effects of (−)-noradrenaline through β1-adrenoceptors on left atrium

Rolipram and IBMX potentiated the effects of (−)-noradrenaline in the presence of ICI118551 11.5-fold and fivefold respectively (Fig. 3A, Table 1). Cilostamide caused a small leftward shift of the concentration-effect curve for (−)-noradrenaline (Fig. 3A) but the difference in potency (Table 1) did not reach significance (P = 0.078). The maximum increase in contractility by combined cilostamide and rolipram prevented further effects of (−)-noradrenaline (Fig. 3A).

Concurrent cilostamide + rolipram uncovers functional β2-adrenoceptors in left atrium

CGP20712A caused a 2.8 log unit nearly surmountable rightward shift of the concentration-effect curve of (−)-adrenaline (Fig. 3B, Table 1), compared with the curve of (−)-adrenaline in the presence of ICI118551 (−logEC50 = 7.06 ± 0.06, n = 4) (Fig. 3B), consistent with mediation through β1-adrenoceptors. CGP20712A-resistant components of the effects of (−)-adrenaline were not observed (Fig. 3B), suggesting absence of β2-adrenoceptor-mediated effects.

Cilostamide and rolipram potentiated the effects of (−)-adrenaline at high concentrations in the presence of CGP20712A twofold and sevenfold respectively (Fig. 3C, Table 1). IBMX (10 µmol·L−1) potentiated the effects of (−)-adrenaline ninefold (Fig. 3C, Table 1). Concurrent cilostamide + rolipram uncovered consistent biphasic concentration-effect curves for (−)-adrenaline with a high-sensitivity component H (−logEC50 = 8.2, f2 = 0.26) and low-sensitivity component L (−logEC50 = 6.0, f1 = 0.74) (Fig. 3C, Table 1). ICI118551, in the presence of CGP20712A, prevented the appearance of the high-affinity component of (−)-adrenaline (Figs 2B and 3C), consistent with mediation through β2-adrenoceptors.

IBMX (10 µmol·L−1) increased contractile force less than the combination of cilostamide and rolipram and failed to reveal a biphasic curve for (−)-adrenaline (data in Table 1). However, 30 µmol·L−1 IBMX markedly increased basal force and unconcealed biphasic curves for (−)-adrenaline (Fig. 3C, Table 1).

Rolipram but not cilostamide potentiates the right ventricular effects of (−)-noradrenaline through β1-adrenoceptors

Mean contractile force was 1.9 ± 0.1 mN (n = 35) and 2.1 ± 0.1 mN (n = 46) in the presence of CGP20712A and ICI118551 respectively. Cilostamide, rolipram and IBMX (10 µmol·L−1) failed to increase right ventricular contractile force in the presence of ICI118551 (Fig. 4A) or CGP20712A (Fig. 4C). The combination of cilostamide + rolipram caused a small increase of contractile force (14 ± 10%, P < 0.05) in the presence of ICI118551 (Fig. 4A) but not in the presence of CGP20712A (Fig. 4C). IBMX (100 µmol·L−1) in the presence of CGP20712A increased ventricular force by 47 ± 14% (n = 4, not shown).

Figure 4.

The influence of PDE inhibitors on the positive inotropic effects of (−)-noradrenaline through β1-adrenoceptors and (−)-adrenaline through β2-adrenoceptors of the free right ventricular wall. (A) Potentiation of the positive inotropic effects of (−)-noradrenaline by rolipram (Rol), concurrent cilostamide + rolipram and IBMX but not by cilostamide (Cil) alone. (B) Effects of (−)-adrenaline mediated through both β1-adrenoceptors and β2-adrenoceptors in the absence of antagonists (controls), through β1-adrenoceptors in the presence of ICI118551 (ICI) and through β2-adrenoceptors in the presence of CGP20712A (CGP). (C) Potentiation of the effects of (−)-adrenaline through β2-adrenoceptors by cilostamide, concurrent cilostamide + rolipram and IBMX but not by rolipram. Fits of some biphasic curves were constrained by using the effect of (−)-isoprenaline as maximum. For further details see Figure 1.

Cilostamide did not significantly change the inotropic potency of (−)-noradrenaline (Fig. 4A, Table 1). Rolipram potentiated twofold the right ventricular effects of (−)-noradrenaline in the presence of ICI118551 (Fig. 4A, Table 1). The effects of (−)-noradrenaline were potentiated 8.5-fold by IBMX and 11-fold by concurrent cilostamide + rolipram (Fig. 4A). The potentiation of the effects of (−)-noradrenaline by IBMX and cilostamide + rolipram were both significantly greater than the potentiation by rolipram alone (P < 0.001 for both conditions).

Concurrent cilostamide and rolipram potentiate the right ventricular effects of (−)-adrenaline through β2-adrenoceptors

(−)-Adrenaline increased right ventricular contractile force with −logEC50 = 6.93 ± 0.05, (n = 5) (Fig. 4B). ICI118551 caused a threefold rightward shift (P < 0.001) of the concentration-effect curve for (−)-adrenaline, suggesting involvement of a minor β2-adrenoceptor-mediated component. In the presence of ICI118551, the −logEC50 was 6.40 ± 0.06 (n = 11) for the effects of (−)-adrenaline mediated through β1-adrenoceptors (Fig. 4B). CGP20712A caused a nearly 3 log unit rightward and partially surmountable shift of the curve for (−)-adrenaline, compared with the curve in the presence of ICI118551, and revealed a small CGP20712A-resistant component with f2 = 0.09 ± 0.02 compared with (−)-isoprenaline (200 µmol·L−1) (Figs 2C and 4B,C, Table 1). Cilostamide in the presence of CGP20712A significantly increased the potency and size (f2) of the CGP20712A-resistant component (Fig. 4C, Table 1). Rolipram in the presence of CGP20712A did not significantly affect the effects of (−)-adrenaline compared with CGP20712A alone (Fig. 4C and Table 1). Rolipram combined with cilostamide caused a fivefold potentiation and markedly increased f2 to 0.92 ± 0.03 (n = 8) of the CGP20712A-resistant component, precluding assessment of the CGP20712A-sensitive component (Fig. 4C, Table 1). IBMX (10 µmol·L−1) in the presence of CGP20712A potentiated threefold the effects of (−)-adrenaline and markedly increased f2 to 0.84 ± 0.09 (n = 16) of the CGP20712A-resistant component of the effects of (−)-adrenaline (Fig. 4C and Table 1). A total of IBMX (100) µmol·L−1 did not cause additional potentiation of the effects of (−)-adrenaline compared with 10 µmol·L−1 IBMX (Table 1). The effects of (−)-adrenaline in the presence of CGP20712A and IBMX were prevented by ICI118551 (Fig. 2C), consistent with mediation through β2-adrenoceptors.

Rolipram but not cilostamide potentiates β1-adrenoceptor-mediated effects of (−)-noradrenaline on left ventricular papillary muscle

Mean contractile force was 1.00 ± 0.06 mN (n = 34) and 1.13 ± 0.10 mN (n = 31) in the presence of CGP20712A and ICI118551, respectively, in left ventricular papillary muscles. In the presence of ICI118551 cilostamide and rolipram did not significantly change contractile force (Fig. 5A). Concurrent rolipram + cilostamide and IBMX (10 µmol·L−1) tended to increase but these effects did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 5A). Cilostamide did not modify the potency of (−)-noradrenaline (Fig. 5A, Table 1). Rolipram, concurrent cilostamide + rolipram and IBMX (10 µmol·L−1) potentiated twofold, sevenfold and tenfold the effects of (−)-noradrenaline, respectively, in the presence of ICI118551 (Fig. 5A, Table 1).

Figure 5.

The influence of PDE inhibitors on the positive inotropic effects of (−)-noradrenaline through β1-adrenoceptors and (−)-adrenaline through β2-adrenoceptors of left ventricular papillary muscles. (A) Potentiation of the positive inotropic effects of (−)-noradrenaline by rolipram (Rol), concurrent rolipram + cilostamide and IBMX but not by cilostamide (Cil) alone. (B) Potentiation of the effects of (−)-adrenaline by cilostamide, cilostamide + rolipram and IBMX but not rolipram in the presence of CGP20712A (CGP). Fits of some biphasic curves were constrained by using the effect of (−)-isoprenaline as maximum. For further details see Figure 1.

Cilostamide and concurrent cilostamide and rolipram, but not rolipram, potentiate β2-adrenoceptor-mediated effects of (−)-adrenaline on left ventricular papillary muscles

In the presence of CGP20712A cilostamide, rolipram, IBMX (10 µmol·L−1) and rolipram + cilostamide did not increase force (Fig. 5B). IBMX (100 µmol·L−1) increased contractile force by 43 ± 7% of (−)-isoprenaline (n = 4, P < 0.05). (−)-Adrenaline in the presence of CGP20712A caused very small increases in contractility (−logEC50 = 6.0), with f2 = 0.06 ± 0.03 (n = 4) compared with (−)-isoprenaline (Fig. 5B, Table 1). Cilostamide but not rolipram increased the CGP20712A-resistant component (Fig. 5B, Table 1). In the presence of IBMX and concurrent presence of cilostamide + rolipram the effects of (−)-adrenaline were potentiated three- and sixfold with f2 values of 0.82 ± 0.04 (n = 7) and 0.98 ± 0.03 (n = 5), respectively, compared with (−)-isoprenaline (Fig. 5B, Table 1). A total of IBMX (100) µmol·L−1 did not cause additional potentiation of the effects of (−)-adrenaline compared with 10 µmol·L−1 IBMX (Table 1). The effects of (−)-adrenaline in the presence of CGP20712A and IBMX (10 µmol·L−1) were prevented by ICI118551 (Fig. 2D), consistent with mediation through β2-adrenoceptors.

Lusitropic effects of catecholamines. Cilostamide and rolipram cause (−)-adrenaline to hasten relaxation through β2-adrenoceptors in left ventricular papillary muscles

To compare lusitropic effects of the catecholamines mediated through β1- and β2-adrenoceptors, we assessed the relaxation accompanying the approximately matching effects produced by (−)-noradrenaline (0.1 µmol·L−1) and (−)-adrenaline (1 µmol·L−1) in the presence of IBMX (10 µmol·L−1) from the experiments of Figure 5. The positive lusitropic effects of these catecholamine concentrations in the absence and presence of cilostamide and rolipram were also assessed. Basal times to peak force and relaxation t1/2 times were 51.5 ± 0.5 ms (n = 71) and 30.8 ± 0.4 ms (n = 71) respectively. (−)-Noradrenaline shortened both the times to peak force and relaxation t1/2 (Figs 6 and 7). Cilostamide, rolipram and concurrent cilostamide + rolipram tended to enhance the relaxant effects of (−)-noradrenaline but none of the effects of the PDE inhibitors reached statistical significance. IBMX itself reduced both times to peak force and relaxation t1/2 (Figs 6 and 7). (−)-Noradrenaline in the presence of IBMX caused significantly greater reductions of time to peak force and relaxation t1/2 than in the absence of IBMX (Figs 6 and 7).

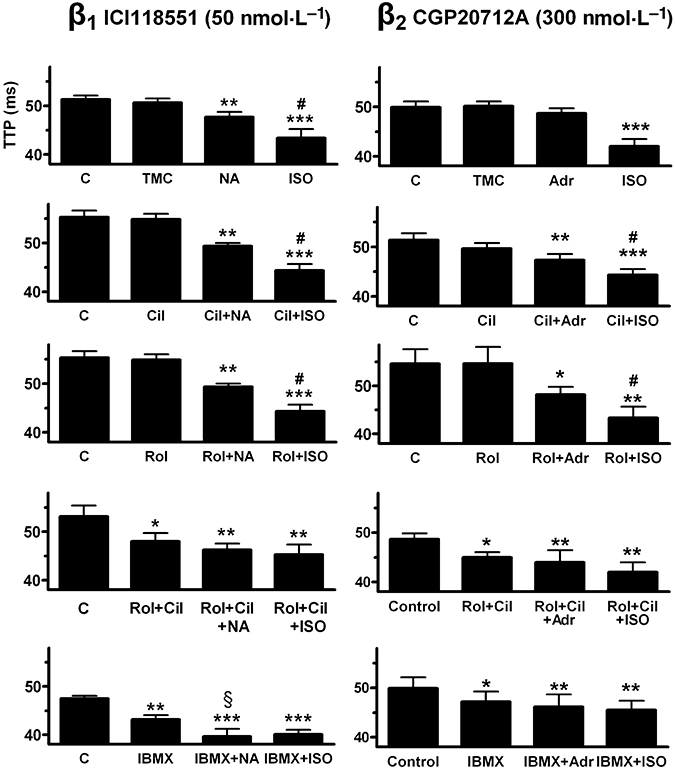

Figure 6.

Influence of PDE inhibitors on shortening of time to peak force (TTP) by (−)-noradrenaline (100 nmol·L−1, NA) through β1-adrenoceptors (left hand panels) and (−)-adrenaline (1 µmol·L−1, Adr) through β2-adrenoceptors (right hand panels). Comparison with the responses to (−)-isoprenaline (100 µmol·L−1, ISO). C, control; TMC, time-matched control; Cil, cilostamide (300 nmol·L−1); Rol, rolipram (1 µmol·L−1) and IBMX (10 µmol·L−1). Data from the experiments on left ventricular papillary muscles (see Fig. 4). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. control; #P < 0.05 vs. catecholamine + PDE inhibitor; §P < 0.05 vs. PDE inhibitor alone.

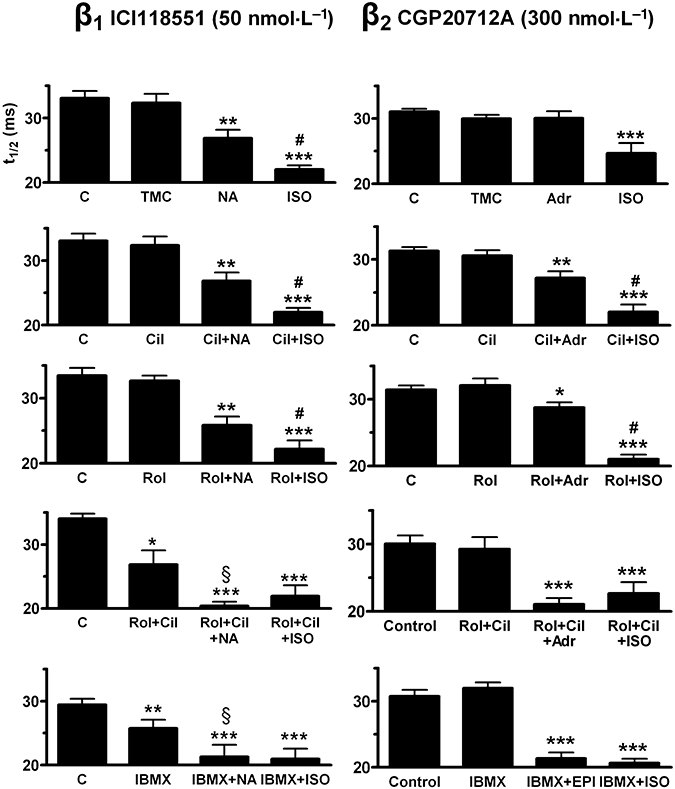

Figure 7.

Influence of PDE inhibitors on the shortening of relaxation time (t1/2) by (−)-noradrenaline (100 nmol·L−1, NA) through β1-adrenoceptors (left hand panels) and (−)-adrenaline (1 µmol·L−1, Adr) through β2-adrenoceptors (right hand panels). Comparison with the responses to (−)-isoprenaline (ISO). C, control; TMC, time-matched control; Cil, cilostamide (300 nmol·L−1); Rol, rolipram (1 µmol·L−1) and IBMX (10 µmol·L−1). Data from the experiments on left ventricular papillary muscles (see Fig. 4). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. control; #P < 0.05 vs. catecholamine + PDE inhibitor; §P < 0.05 vs. PDE inhibitor alone.

(−)-Adrenaline did not hasten relaxation (Figs 6 and 7). However, in the presence of cilostamide, rolipram and IBMX, (−)-adrenaline significantly reduced both times to peak force and relaxation t1/2 (Figs 6 and 7).

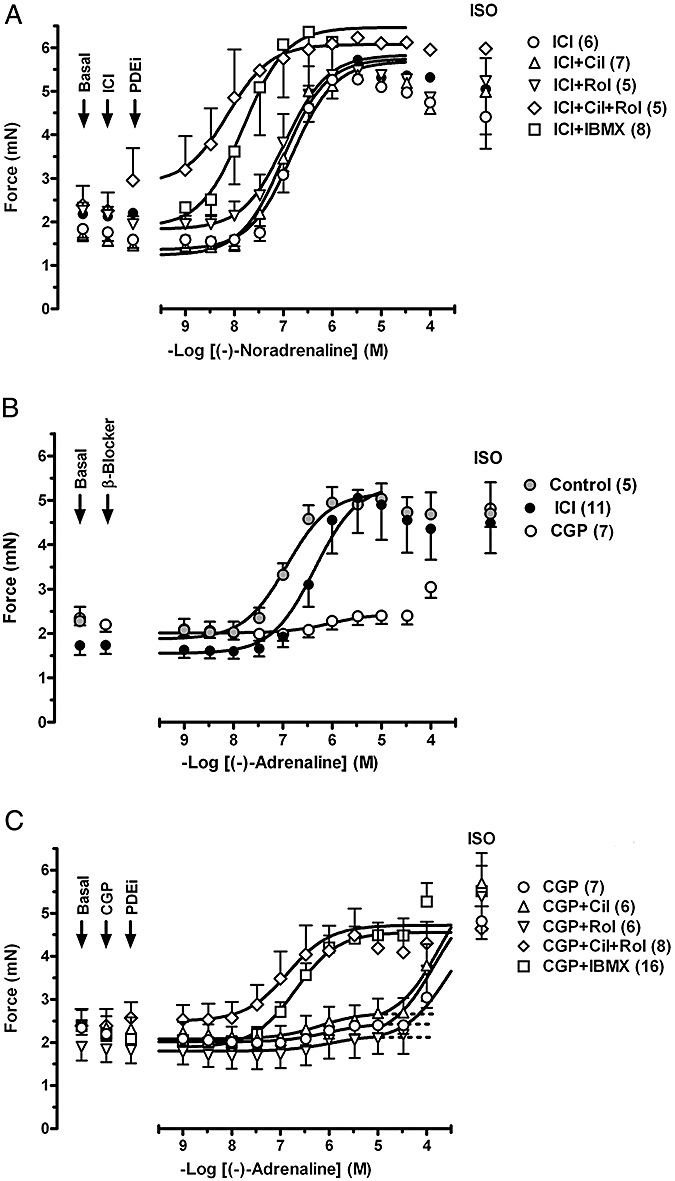

(−)-Noradrenaline increases ventricular ICa-L exclusively through β1-adrenoceptors

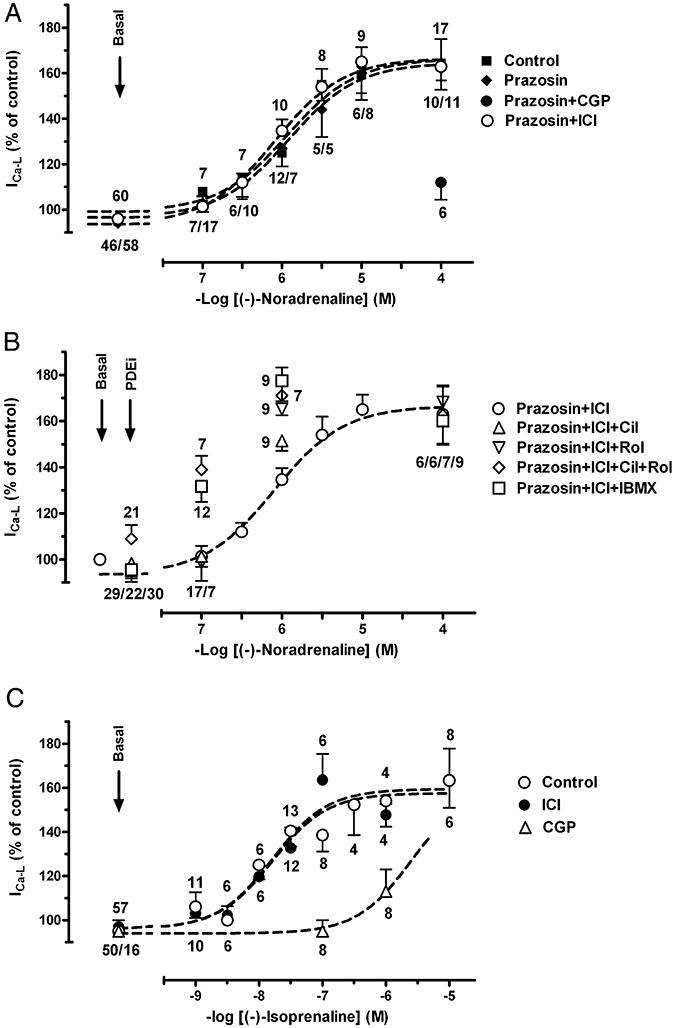

Basal current density of ICa-L in rat ventricular myocytes was 10.2 ± 0.2 pA pF−1 (n = 495). Representative experiments of (−)-noradrenaline-evoked increases in ICa-L and the effects of rolipram, cilostamide and IBMX are shown in Figure 8 (left hand panels). (−)-Noradrenaline increased ICa-L in a concentration-dependent manner with −logEC50 = 5.95 ± 0.15 (Fig. 9A). The effects of (−)-noradrenaline were resistant to blockade by the β2-adrenoceptor-selective antagonist ICI118551 but antagonized by the β1-adrenoceptor-selective antagonist CGP20712A (Fig. 9A), consistent with exclusive mediation through β1-adrenoceptors. Prazosin failed to alter the concentration-effect curve for (−)-noradrenaline, ruling out participation of α1-adrenoceptors (Fig. 9A). The effects of (−)-isoprenaline on ICa-L are shown for comparison in Fig. 9C. As found with (−)-noradrenaline, the effects of (−)-isoprenaline were antagonized by CGP20712A but not by ICI118551, consistent with mediation through β1- but not through β2-adrenoceptors. (−)-Isoprenaline (−logEC50 = 7.70 ± 0.20, Fig. 9C) was approximately 50-fold more potent than (−)-noradrenaline.

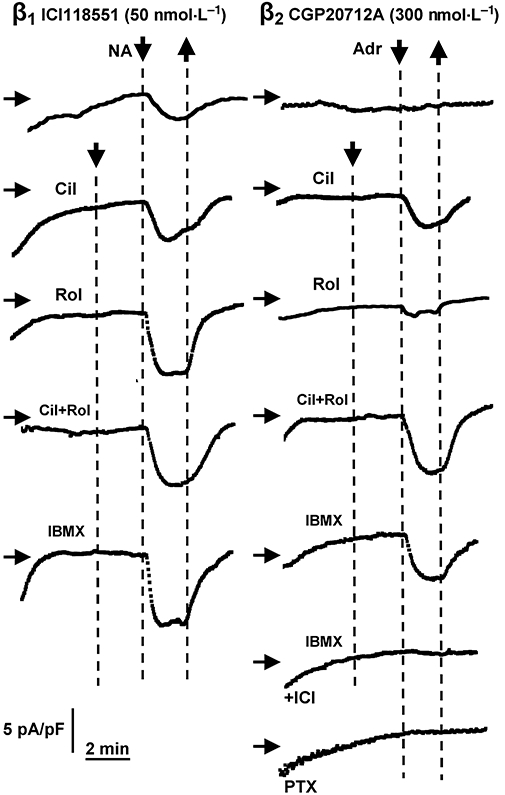

Figure 8.

Augmentation by PDE inhibitors of increases in ICa-L evoked by (−)-noradrenaline (NA) through β1-adrenoceptors (ICI118551 present, left hand panels) and unmasking of (−)-adrenaline (Adr) responses mediated through β2-adrenoceptors (CGP20712A present, right hand panels). Representative experiments of ventricular myocytes. Displayed are time courses of ICa-L amplitudes measured in individual cells. Scaling is given in the left lower corner (same scaling for all graphs). Cilostamide (300 nmol·L−1, Cil), alone or combined with rolipram (1 µmol·L−1, Rol) and IBMX (10 µmol·L−1) uncovered (−)-adrenaline-evoked increases in ICa-L through β2AR. Prevention of effects of (−)-adrenaline in the presence of IBMX by ICI118551 (50 nmol·L−1, ICI). Pertussis toxin (PTX) did not uncover effects of (−)-adrenaline. Horizontal arrows indicate the level of 10 pA pF−1; downward-pointing arrows and upward-pointing arrows indicate addition and washout of PDE inhibitors and catecholamines respectively.

Figure 9.

Concentration-dependent increases of ICa-L by (−)-noradrenaline and (−)-isoprenaline. (A) (−)-Noradrenaline-induced increases in ICa-L is not affected by prazosin (1 µmol·L−1) and ICI118551 (50 nmol·L−1, ICI) but suppressed by CGP20712A (300 nmol·L−1, CGP). (B) Potentiation of (−)-noradrenaline-induced increases of ICa-L by cilostamide (300 nmol·L−1 Cil), rolipram (1 µmol·L−1, Rol), concurrent cilostamide + rolipram and IBMX (10 µmol·L−1). (C) Effects of (−)-isoprenaline are exclusively mediated through β1-adrenoceptors. Numbers indicate number of myocytes.

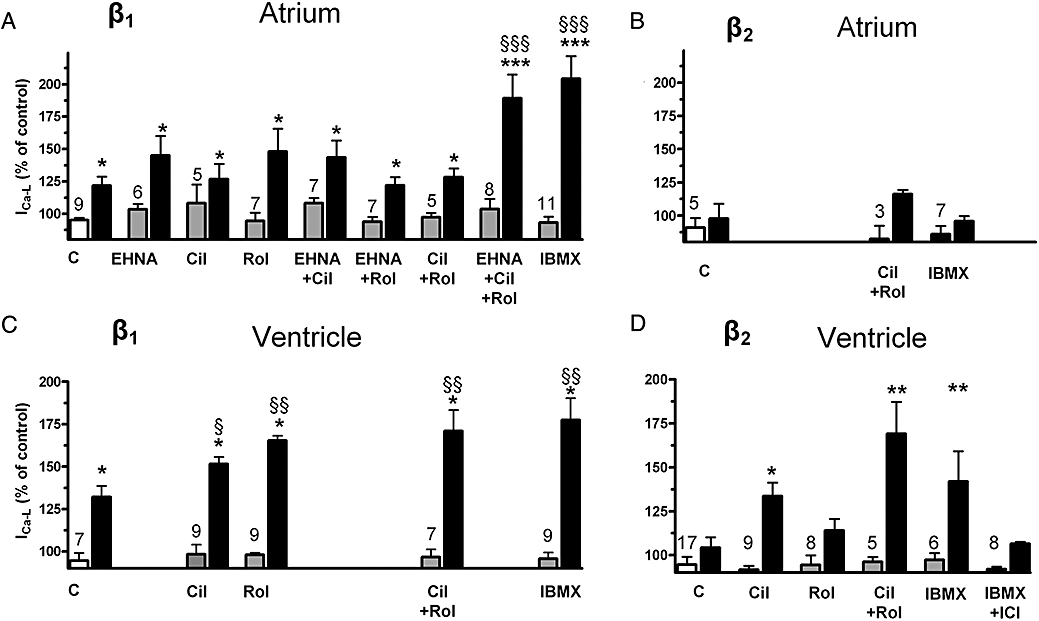

Both cilostamide and rolipram augment (−)-noradrenaline-evoked ICa-L increases through ventricular β1-adrenoceptors

The PDE inhibitors did not significantly modify basal ICa-L in the presence of ICI118551 (Fig. 10C) or CGP20712A (Fig. 10D). (−)-Noradrenaline (1 µmol·L−1) (ICI118551 present) caused an approximately half maximal increase of ICa-L (Figs 9A,B and 10C). The responses to (−)-noradrenaline (1 µmol·L−1) were significantly increased by cilostamide (P < 0.05), rolipram (P < 0.01) and the combination of cilostamide + rolipram (P < 0.01), consistent with a role of both PDE3 and PDE4 (Figs 8,9 and 10C). IBMX (10 µmol·L−1) enhanced the (−)-noradrenaline response more than cilostamide (P < 0.01) but not significantly more than the responses to rolipram or concurrent cilostamide + rolipram (Figs 9B and 10C). The effects of 100 nmol·L−1 (−)-noradrenaline were only increased by IBMX and the combination of cilostamide + rolipram but not by cilostamide or rolipram alone (Fig. 9B).

Figure 10.

Effects of PDE inhibitors on ICa-L responses to (−)-noradrenaline (1 µmol·L−1) through β1-adrenoceptors (ICI118551 50 nmol·L−1 present; A, C) and (−)adrenaline (10 µmol·L−1) through β2-adrenoceptors (CGP20712A 300 nmol·L−1 present; B, D) in atrial (A, B) and ventricular (C, D) myocytes. Responses to EHNA (10 µmol·L−1), cilostamide (300 nmol·L−1, Cil), rolipram (1 µmol·L−1, Rol) and IBMX (10 µmol·L−1) are depicted in grey columns, responses to agonists in black columns. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared with the corresponding basal; §P < 0.05, §§P < 0.01, §§§P < 0.001 compared with the effect in the absence of PDE inhibitor. Numbers on grey columns indicate number of myocytes.

Cilostamide and concurrent cilostamide + rolipram, but not rolipram alone, cause (−)-adrenaline-evoked increases of ICa-L through ventricular β2-adrenoceptors

(−)-Adrenaline (10 µmol·L−1) (CGP20712A present) caused a marginal increase of ICa-L which did not reach statistical significance (Figs 8 and 10D). In the presence of cilostamide, but not rolipram, (−)-adrenaline significantly (P < 0.05) increased ICa-L (Figs 8 and 10D). In the presence of concurrent cilostamide + rolipram, (−)-adrenaline enhanced ICa-L significantly more (P < 0.01) than in the presence of cilostamide alone (Figs 8 and 10D). ICI118551 (50 nmol·L−1) nearly abolished the (−)-adrenaline-evoked increase in the presence of both CGP20712A and IBMX (10 µmol·L−1) (Fig. 10D). The (−)-adrenaline-evoked increases of ICa-L in the presence of IBMX and CGP20712A were 42 ± 16% (n = 16) and 6.5 ± 1% (n = 8) in the absence and presence of ICI118551, respectively (P < 0.01), consistent with exclusive mediation through β2-adrenoceptors.

To investigate whether Gi inactivation facilitated β2-adrenoceptor responses, myocytes were incubated at least 3 h with PTX 1.5 µg mL−1 at 37°C under constant agitation as described (Gong et al., 2000). However, even after PTX treatment of ventricular myocytes 10 µmol·L−1 (−)-adrenaline in the presence 300 nmol·L−1 CGP20712A failed to increase ICa-L (n = 10 cells, Fig. 8). In contrast, the PTX treatment nearly abolished the blunting effect of carbachol (10 µmol·L−1) on the (−)-isoprenaline (1 µmol·L−1) evoked increase in ICa-L (n = 7 cells, not shown).

(−)-Noradrenaline increases atrial ICa-L through β1-adrenoceptors in the presence of IBMX

Basal current density of ICa-L in rat atrial myocytes was 6.5 ± 0.3 pA pF−1 (n = 95). The PDE inhibitors did not significantly modify basal ICa-L in the presence of ICI118551 (Fig. 10A). The response to (−)-noradrenaline (1 µmol·L−1), a concentration 50-fold greater than the concentration causing half maximal inotropic effects (Fig. 3, Table 1), was studied in the absence and presence of PDE inhibitors (Fig. 10A). (−)-Noradrenaline produced a moderate increase in ICa-L that was not significantly enhanced by EHNA, cilostamide, rolipram or concurrent rolipram + cilostamide, but markedly increased by both IBMX (10 µmol·L−1) and the combination of cilostamide, rolipram and EHNA (Fig. 10A). The responses to 1 µmol·L−1 (−)-noradrenaline in the presence of IBMX or the combination of EHNA, cilostamide and rolipram (Fig. 10A) are not significantly different from the response to 10 µmol·L−1 (−)-noradrenaline which increased ICa-L by 80 ± 11% (n = 6, not shown).

(−)-Adrenaline (10 µmol·L−1 in the presence of CGP20712A 300 nmol·L−1) only produced marginal increases of ICa-L which were not significantly affected by concurrent rolipram + cilostamide or IBMX (Fig. 10B).

Discussion

Our results point to region-specific and isoenzyme-dependent differences of the roles of PDE3 and PDE4 in reducing β1- and β2-adrenoceptor function in the rat heart. These conclusions are based on a range of findings. The sinoatrial tachycardia caused by (−)-noradrenaline through β1-adrenoceptors and (−)-adrenaline through β2-adrenoceptors was not potentiated by cilostamide or rolipram, inconsistent with modulation by either PDE3 or PDE4. However, rolipram caused tachycardia, suggesting that PDE4 reduces basal sinoatrial beating rate by decreasing the PKA-controlled pacemaker rhythm, independently of β-adrenoceptor activation. In contrast, the positive inotropic effects to (−)-noradrenaline, mediated through atrial and ventricular β1-adrenoceptors, were potentiated by rolipram, but not by cilostamide, suggesting hydrolysis of inotropically relevant cAMP by PDE4 but not by PDE3. Further, cilostamide but not rolipram potentiated the minor inotropic ventricular effects of (−)-adrenaline mediated through β2-adrenoceptors, suggesting a blunting effect of PDE3. The combination of cilostamide + rolipram uncovered functional cardiostimulation mediated through β2-adrenoceptors in left atrium and markedly potentiated the effects of (−)-adrenaline in right and left ventricular myocardium through β2-adrenoceptors, suggesting that PDE3 and PDE4 act in concert to prevent manifestation of an inotropic function through β2-adrenoceptors. Increases of ventricular ICa-L through β1-adrenoceptor activation were augmented by either cilostamide or rolipram, consistent with modulation by both PDE3 and PDE4, but inconsistent with the selective blunting by PDE4, but not PDE3, of the positive inotropic effects of (−)-noradrenaline. Cilostamide but not rolipram facilitated ventricular ICa-L activation through β2-adrenoceptors, suggesting selective modulation by PDE3, consistent with the blunting effects of PDE3 of the positive inotropic effects of (−)-adrenaline. Our ventricular findings with β2-adrenoceptor stimulation are consistent with an important control by PDE3 of cAMP generated in the subsarcolemmal space (ICa-L), but a more strict control of contractility by both PDE3 and PDE4 near the contractile machinery.

PDE4 modulates basal sinoatrial beating but not the tachycardia mediated with (−)-noradrenaline through β1-adrenoceptors and (−)-adrenaline through β2-adrenoceptors

The basal beating rate of sinoatrial cells is tightly controlled by cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PK)-A phosphorylation of phospholamban and probably other PKA substrates (Vinogradova et al., 2006). Basal PDE activity is high in sinoatrial cells compared with ventricular myocytes (Vinogradova et al, 2005; 2007; 2008). The PDE3-selective inhibitor milrinone markedly increases beating rate and phospholamban phosphorylation in rabbit sinoatrial node cells, consistent with a control of basal heart rate by PDE3 (Vinogradova et al., 2007; 2008). Vinogradova et al. (2008) provided evidence that milrinone increased Ca2+ loading of the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), attributed to enhanced Ca2+ ATPase pumping expected from the phospholamban phosphorylation, leading to enhanced Ca2+ release from subsarcolemmal ryanodine RyR2 channels which in turn activated the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger inward current that accelerated diastolic depolarization and sinoatrial beating rate.

In contrast to the results in rabbit (Vinogradova et al., 2008), in the rat, the PDE4 inhibitor rolipram but not the PDE3-selective cilostamide caused tachycardia. The rolipram-evoked tachycardia in the rat sinoatrial node persisted during β1-adrenoceptor blockade with CGP20712A, ruling out sensitization by rolipram of β1-adrenoceptor-mediated effects by traces of endogenously released noradrenaline. Our results with rolipram-evoked tachycardia and the failure of cilostamide to change sinoatrial rate are consistent with a direct reduction of the basal sinoatrial rate by PDE4 but not by PDE3 in the rat. The tachycardia caused by rolipram is likely to result from the inhibition of PDE4, followed by elevation of sinoatrial cAMP, increased PKA-catalysed phosphorylation of proteins leading to accelerated Ca2+-cycling and enhanced beating rate. In addition, the increased sinoatrial cAMP in the presence of rolipram may directly open cyclic nucleotide-gated HCN channels responsible for the current activated by hyperpolarisation, If (DiFrancesco and Tortora, 1991), thereby contributing to tachycardia. However, the milrinone-evoked sinoatrial tachycardia, described by Vinogradova et al. (2008), was hardly reduced by If inhibition with Cs+, so that a role for If appears unlikely.

Recent work shows that, in contrast to the selective reduction of sinoatrial beating rate by PDE3 in the rabbit proposed by Vinogradova et al. (2008) and PDE4 in the rat (this work), both PDE3 and PDE4 reduce murine basal sinoatrial rate (Galindo-Tovar and Kaumann, 2008). Unlike mouse and rat, in the dog the PDE4 inhibitor rolipram does not change sinoatrial rate but PDE3 inhibitors cause tachycardia (Heaslip et al., 1999). Thus, there are species differences as to which PDE isoforms reduce basal sinoatrial rate.

The IBMX (100 µmol·L−1) caused greater tachycardia than IBMX (10 µmol·L−1). Additional PDEs (PDE2?) may control basal sinoatrial rate, when PDE3 and PDE4 are inhibited. Alternatively, IBMX (100 µmol·L−1) may have caused a more complete blockade of PDE4 than rolipram (1 µmol·L−1).

Vinogradova et al. (2008) suggested that the PDE-dependent control of local Ca2+ release and basal spontaneous sinoatrial beating rate used the same mechanism as that used by β-adrenoceptor stimulation to accelerate sinoatrial rate (Vinogradova et al., 2002). However, our results disclosed an unexpected difference. The positive chronotropic effects of (−)-noradrenaline through β1-adrenoceptors and (−)-adrenaline through β2-adrenoceptors in the rat were not potentiated by the separate or joint presence of cilostamide and rolipram. This is in contrast to the β-adrenoceptor-independent tachycardia elicited by rolipram, suggesting that the sinoatrial cAMP pools, presumably enhanced through activation of β1- and β2-adrenoceptors, are distinct from the rolipram-sensitive cAMP pool controlled by PDE4 that modulates basal sinoatrial rate. A similar discrepancy was recently reported in murine sinoatrial node, in which both PDE3 and PDE4 reduce basal sinoatrial beating rate but neither controls the β1-adrenoceptor-mediated tachycardia of (−)-noradrenaline (Galindo-Tovar and Kaumann, 2008).

Could the catecholamine-evoked tachycardia occur through β-adrenoceptors via a cAMP-independent pathway? Yatani et al. (1987) suggested that effects of isoprenaline on L-type Ca2+ channels occur through direct coupling to Gs protein and without diffusible cAMP in guinea-pig myocytes. However, the comprehensive evidence obtained directly from sinoatrial cells by Vinogradova et al. (2006; 2008), as well as classical work, points to an obligatory involvement of a cAMP-dependent pathway. Taniguchi et al. (1977) reported that noradrenaline caused a maximum elevation of cAMP and increase of beating rate by 1 min, but the cAMP response faded to control levels while the tachycardia remained stable by the 5th minutes in rabbit sinoatrial pacemaker cells. The non-selective PDE inhibitor, theophylline, prevented the fade of the noradrenaline-evoked cAMP response, consistent with a role for PDEs. Taniguchi et al. (1977) suggested that the adenylyl cyclase was involved. However, the work of Taniguchi et al. (1977) showing that the noradrenaline-evoked tachycardia persists despite the PDE-induced fade of the cAMP signal, is consistent with the failure of PDE inhibitors to influence the chronotropic potency of (−)-noradrenaline in the rat (this work) and murine sinoatrial node (Galindo-Tovar and Kaumann, 2008), but not necessarily consistent with an involvement of cAMP. On the other hand, Tanaka et al. (1996) provided conclusive evidence for an obligatory involvement of cAMP and PKA in catecholamine-evoked sinoatrial tachycardia through β-adrenoceptors in rabbit sinoatrial cells. Positive chronotropic responses and increases in ICa-L to flash photolysis of caged isoprenaline and cAMP were abolished by the PKA inhibitor Rp-cAMP in rabbit sinoatrial cells.

PDE4 limits the inotropic function of left atrial β1-adrenoceptors

Rolipram caused marked potentiation (11-fold) of the positive inotropic effects of (−)-noradrenaline on left atrium but cilostamide failed to affect the inotropic potency. These effects are consistent with an exclusive role of PDE4 in controlling the inotropically relevant cAMP generated through left atrial β1-adrenoceptor stimulation. IBMX also potentiated the effects of (−)-noradrenaline but not more than rolipram (Fig. 3A, Table 1), making it unlikely that, apart from PDE4, other PDE isoforms modulate β1-adrenoceptor-mediated effects of (−)-noradrenaline in left atrium. The selective control by PDE4 of left atrial inotropic β1-adrenoceptor function observed in the rat is quite similar in the mouse (Galindo-Tovar and Kaumann, 2008).

Rolipram and IBMX (10 µmol·L−1) potentiated not only the left atrial effects of low (−)-noradrenaline concentrations (11-fold and fivefold) observed in the presence of ICI118551 (Fig. 3A, Table 1) but also similarly the effects of high (−)-adrenaline concentrations (sevenfold and ninefold) in the presence of CGP20712A (Fig. 3C, Table 1). These latter findings can be interpreted as surmountability by high (−)-adrenaline concentrations of the β1-adrenoceptor blockade by CGP20712A. Under this condition of reactivation of β1-adrenoceptors, PDE4 appears to limit the inotropically relevant cAMP generated by (−)-adrenaline to a similar extent as that generated by receptor interaction with (−)-noradrenaline in the absence of CGP20712A. In contrast to the failure of cilostamide to significantly increase the potency of (−)-noradrenaline, cilostamide produced a small fold potentiation of the effects of high (−)-adrenaline concentrations in the presence of CGP20712A, suggesting a small role of PDE3 at β1-adrenoceptors, activated by (−)-adrenaline. However, after cilostamide, the f2 fraction was also increased, so that participation of β2-adrenoceptors cannot be excluded. The ninefold potentiation of the effects of (−)-adrenaline by IBMX (10 µmol·L−1) in the presence of CGP20712A appears to be mainly due to PDE4 inhibition at β1-adrenoceptors because it is close to the sevenfold potentiation caused by rolipram. The twofold greater potentiation with 30 µmol·L−1 IBMX, compared with 10 µmol·L−1 IBMX, could be caused by an additional small involvement of PDE2 or alternatively, be due merely to an additive cardiostimulant component produced by IBMX.

PDE3 and PDE4 jointly prevent β2-adrenoceptor function in left atrium

The concentration-effect curves of (−)-adrenaline were monophasic without a CGP20712A-resistant component, even in the presence of cilostamide or rolipram, consistent with an interaction with a single receptor population (i.e. β1-adrenoceptors). Therefore, inhibition of PDE3 or PDE4 alone does not appear to reveal β2-adrenoceptor-mediated effects of (−)-adrenaline. However, the concurrent inhibition of PDE3 and PDE4 with cilostamide and rolipram in the presence of CGP20712A uncovered functional β2-adrenoceptors in the left atrium. The CGP20712A-resistant effects of low (−)-adrenaline concentrations in the presence of both cilostamide and rolipram were prevented by ICI118551, consistent with mediation through β2-adrenoceptors (Figs 2B and 3C). Therefore, PDE3 and PDE4, acting in concert, appear to prevent the manifestation of β2-adrenoceptor-mediated effects of (−)-adrenaline in rat left atrium. It is not clear why consistent β2-adrenoceptor-mediated effects of (−)-adrenaline were not observed in the presence of IBMX (10 µmol·L−1), perhaps because inhibition of PDE3 and PDE4 was less complete than with the combination of cilostamide + rolipram. Indeed, a higher IBMX concentration of 30 µmol·L−1 also revealed a CGP20712A-resistant component of the (−)-adrenaline effects (Fig. 3C, Table 1) with f2 = 0.25, probably mediated through β2-adrenoceptors. However, even under pronounced non-selective PDE inhibition with IBMX, the Emax of the β2-adrenoceptor-mediated effects was small compared with the Emax of β1-adrenoceptor-mediated effects. The inotropic properties of rat and murine (Galindo-Tovar and Kaumann, 2008) left atrial β2-adrenoceptors are remarkably similar: β1-adrenoceptor-mediated effects of the catecholamines are blunted by PDE4 but the modest β2-adrenoceptor-mediated effects of (−)-adrenaline are completely suppressed by concurrent action of PDE3 and PDE4.

The ventricular inotropic effects of (−)-noradrenaline, mediated through β1-adrenoceptors, are selectively blunted by PDE4

Rolipram but not cilostamide potentiated twofold the positive inotropic effects of (−)-noradrenaline on both right ventricular strips and left ventricular papillary muscles (Figs 4A and 5A, Table 1), consistent with selective hydrolysis of inotropically relevant cAMP by PDE4 but not PDE3 reported previously for β1-adrenoceptors activated by (−)-noradrenaline (Vargas et al., 2006) or (−)-isoprenaline (Katano and Endoh, 1992). Although cilostamide did not significantly modify the potency of (−)-noradrenaline, concurrent cilostamide + rolipram caused an eightfold potentiation of the effects of (−)-noradrenaline in right ventricular preparations (Fig. 4A, Table 1). The synergistic potentiation of the effects of (−)-noradrenaline by concurrent cilostamide + rolipram, that is, when both PDE3 and PDE4 are inhibited, confirms similar observations in rat right ventricle and are accompanied by marked increases in cAMP levels (Vargas et al., 2006). The accumulation of inotropically relevant cAMP during inhibition of PDE4 by rolipram may leak into the compartment of PDE3 and produce PKA-catalysed phosphorylation (Gettys et al., 1987; Smith et al., 1991) thereby activating PDE3 to further hydrolyze inotropically relevant cAMP.

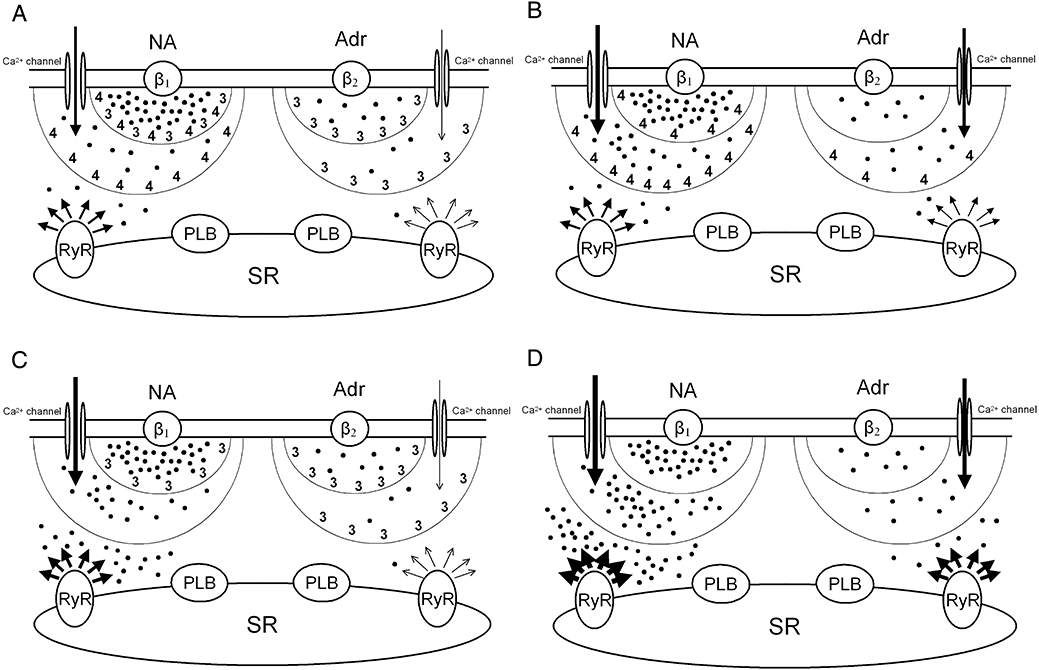

Interestingly, in the presence of concurrent cilostamide + rolipram (or IBMX 10 µmol·L−1) approximately 10-fold lower (−)-noradrenaline concentrations sufficed to produce approximately half maximal increases in ICa-L compared with the absence of the PDE inhibitors (Fig. 9B). The inotropic potency of (−)-noradrenaline was nearly 10-fold higher than the potency to increase ICa-L. However, both effects were potentiated approximately 10-fold by concurrent cilostamide + rolipram (compare Figs 4A and 9B). The similarity of these potentiations is consistent with the elimination of local cAMP gradients at the Ca2+ channel domain and SR and a homogenous distribution of a high cAMP level across the sarcoplasm when both PDE3 and PDE4 are inhibited (see also Fig. 11D).

Figure 11.

Hypothetical regulation of cAMP levels by activated PDE3 (3) and PDE4 (4) in compartments at different distances from activated β1- and β2-adrenoceptors in rat ventricle. (A) Physiological situation. (B) Inhibition of PDE3. (C) Inhibition of PDE4. (D) Inhibition of both PDE3 and PDE4. Black dots represent steady state concentrations of cAMP in each domain. (−)-Noradrenaline (NA) and (−)-adrenaline (Adr) stimulate β1- and β2-adrenoceptors, respectively, thereby increasing the production of cAMP and activating PDE3 and PDE4. Two sequential barriers, formed by activated PDEs, break down cAMP. The composition of PDEs in both barriers is different for β1- and β2-adrenoceptors. L-type Ca2+ channel function is enhanced by cAMP and only reduced by PDE activity of the first barrier (smaller half-circle), whereas inotropically relevant cAMP has to pass through the more distal second barrier (larger half-circle) to reach the SR. The first barrier corresponds to PDE3 and PDE4 bound to the sarcolemma. The second barrier is produced by PDE3 and PDE in the cytoplasm and at the SR. Arrows represent Ca2+ current through L-type channels and Ca2+ release from RyR2 channels (RyR). Arrow thickness is proportional to ICa-L and Ca2+ release. The inotropic responses are assumed to be proportional to Ca2+ released from the SR through RyR2 channels. The cAMP-dependent activation of PKA and subsequent PKA-catalysed phosphorylation of Ca2+ channels, phospholamban (PLB), PDE4 and RyR2 is not represented to avoid overcrowding. Both PDE3 and PDE4 blunt the ICa-L response to (−)-noradrenaline (NA) mediated through β1-adrenoceptors but only PDE3 blunts the ICa-L response to (−)-adrenaline mediated through β2-adrenoceptors. Positive inotropic responses to both (−)-noradrenaline (β1-adrenoceptors) and (−)-adrenaline (β2-adrenoceptors) are assumed to occur at least in part through PKA-catalysed phosphorylation of Ca2+ channels, RyR2 channels and phospholamban (PLB). The positive inotropic effects of catecholamines are controlled by PDE4 through β1-adrenoceptors but by PDE3 through β2-adrenoceptors.

PDE3 but not PDE4 moderately blunts (−)-adrenaline responses, but acting in concert with PDE4, markedly reduces β2-adrenoceptor-mediated effects of (−)-adrenaline in ventricle

Low (−)-adrenaline concentrations caused a small increase in contractility in the presence of CGP20712A with an f2 of 0.09 and 0.06 in right and left ventricular preparations, respectively, presumably mediated through β2-adrenoceptors (Figs 4B,C and 5B). Very high (−)-adrenaline concentrations (30–100 µmol·L−1) partially surmounted the β1-adrenoceptor blockade by (−)-adrenaline (Figs 4B,C and 5B). Rolipram failed to affect the (−)-adrenaline responses, ruling out hydrolysis by PDE4 of inotropically relevant cAMP through β2-adrenoceptors. Cilostamide, instead, caused twofold potentiation of the effects of (−)-adrenaline with small increases in f2 to 0.15–0.17 in both right and left ventricle (Figs 4C and 5B, Table 1), consistent with a small role of PDE3 in blunting β2-adrenoceptor-mediated responses. However, concurrent cilostamide + rolipram caused a marked increase of f2 to 0.92 and 0.99, and fivefold and sixfold potentiation of the effects of (−)-adrenaline in right and left ventricle (Figs 4C and 5B, Table 1).

The IBMX (10 µmol·L−1) caused a similar increase in f2 to 0.82–0.84 and threefold potentiation of the right and left ventricular effects of (−)-adrenaline; these effects were prevented by ICI118551 (Fig. 2C,D), consistent with mediation through β2-adrenoceptors. IBMX (100 µmol·L−1) did not cause greater potentiation than IBMX (10 µmol·L−1) or concurrent rolipram + cilostamide. The similar potentiation of the effects of (−)-adrenaline by IBMX compared with concurrent cilostamide + rolipram suggests that mostly PDE3 and PDE4 control inotropically relevant cAMP and make unlikely a contribution of other PDE isoenzymes (e.g. PDE2).

To account for the synergistic potentiation of the effects of (−)-adrenaline by concurrent cilostamide + rolipram, the accumulation of inotropically relevant cAMP during inhibition of PDE3 by cilostamide may leak into the compartment of PDE4 and produce PKA-catalysed phophorylation (MacKenzie et al., 2002) thereby activating PDE4 to further hydrolyze cAMP that has become inotropically relevant.

PDE4 blunts β1-adrenoceptor-mediated increases of both ICa-L and contractile force but PDE3 reduces only ICa-L

In line with previous work with (−)-isoprenaline on rat ventricular myocytes (Verde et al., 1999; Rochais et al., 2006), our results with (−)-noradrenaline show that both cilostamide and rolipram enhance the β1-adrenoceptor-mediated ICa-L responses. These results suggest that both PDE3 and PDE4 hydrolyze subsarcolemmal cAMP generated through β1-adrenoceptor stimulation in the vicinity of the ICa-L channels as reported previously (Rochais et al., 2006) and are consistent with the immunocytochemical localisation of both PDE3 and PDE4 in the sarcolemma (Okruhlicova et al., 1996). In contrast and, as reported before (Katano and Endoh, 1992; Vargas et al., 2006), only inhibition of PDE4 but not of PDE3 potentiates the positive inotropic effects of catecholamines, suggesting that the PDE3-catalysed hydrolysis of subsarcolemmal cAMP reduces β1-adrenoceptor-mediated increases in ICa-L without affecting contractile events.

The dissociation between PDE3-evoked reduction of β1-adrenoceptor-mediated increases in ICa-L but not of contractile responses suggests that β1-adrenoceptor/PDE3/L-type Ca2+ channel complexes are located at a separate compartment from the domains of phospholamban and RyR2 channels that contribute to enhanced contractility through PKA-catalysed phosphorylation, via greater Ca2+ uptake and release from and to the SR respectively. On the other hand, PDE4 reduces both the inotropically relevant cAMP (Vargas et al., 2006) and the cAMP in the ICa-L domain (Rochais et al., 2006) through β1-adrenoceptor stimulation. Rat ventricular PDE4 activity was initially only detected in the cytosol (Weishaar et al., 1987). Interestingly, inhibition of PDE4 causes a more marked increase in cAMP in the cytosol than in the subsarcolemmal compartment in rat cardiomyocytes (Leroy et al., 2008), suggesting that the control of cytosolic cAMP by PDE4 contributes to the blunting of the β1-adrenoceptor-mediated inotropic responses.

The β1-adrenoceptor-evoked increases of cAMP lead to PKA-dependent phosphorylation and activation of PDE4 (Leroy et al., 2008). PDE4-catalysed hydrolysis of cAMP reduces the free diffusion of cAMP and causes gradients of both cAMP and PKA (Saucerman et al., 2006). During inhibition of PDE4, more cAMP accumulates at the domains of L-type Ca2+ channels, phospholamban as well as RyR2 channels, as schematically depicted in Figure 11. This interpretation has to be restricted to rat ventricle because, for example, in human ventricular and atrial myocardium β1-adrenoceptor-mediated increases in contractility are greatly reduced by PDE3 activity, but not by PDE4 activity (Christ et al., 2006b; Kaumann et al., 2007), presumably because PDE3, rather than PDE4, is bound to the SR (Lugnier et al., 1993). Unfortunately, a comparison of the expression and activity of rat and human myocardial PDE3 and PDE4 (see Osadchii, 2007) does not yet appear to explain species-dependent control of β1-adrenoceptors and their function by these PDE isoenzymes.

β2-Adrenoceptor-mediated increases of ventricular ICa-L and contractility are blunted by PDE3 but not PDE4

In contrast to the increase in ICa-L obtained with (−)-noradrenaline, mediated through β1-adrenoceptors, the effect of (−)-adrenaline through β2-adrenoceptors was reduced by PDE3 only. This apparently contradicts the results of Rochais et al. (2006). They demonstrated on rat ventricular myocytes cultured for 24 h that cilostamide and to a greater extent the PDE4 inhibitor Ro 20-1724 enhanced the increases of ICa-L induced by isoprenaline in the presence of CGP20712A, attributed to mediation through β2-adrenoceptors. In contrast, using freshly isolated myocytes, we found that in the presence of CGP20712A only cilostamide, but not rolipram, enhanced the (−)-adrenaline-evoked increase in ICa-L. The discrepancy between our results and those of Rochais et al. (2006) is puzzling but could be due to different experimental conditions. We worked at 37°C, used 300 nmol·L−1 CGP20712A as well as 10 µmol·L−1 (−)-adrenaline and demonstrated that the effects of (−)-adrenaline on ICa-L were mediated through β2-adrenoceptors because they were prevented by 50 nmol·L−1 ICI118551 (at least in the presence of IBMX). On the other hand, Rochais et al. worked at 21–27°C, used 1 µmol·L−1 CGP20712A as well as 5 µmol·L−1 (−)-isoprenaline but did not verify whether the effects of (−)-isoprenaline in the presence of (−)-CGP20712A were antagonized by ICI118551. It is possible that (−)-isoprenaline in the presence of CGP20712A did partially surmount the blockade of β1-adrenoceptors in the experiments of Rochais et al. (2006). CGP20712A 300 nmol·L−1 produced an approximate 2 log incomplete shift of the concentration-effect curve of (−)-isoprenaline for increases in ICa-L density (Fig. 9C). The threefold greater concentration of CGP20712A (1 µmol·L−1) used by Rochais et al. (2006) would be expected to cause a 2.5 log unit shift of the curve for (−)-isoprenaline. Assuming that the −logEC50 for the effects of (−)-isoprenaline on ICa-L is 7.7 (Fig. 9C), its −logEC50 at β1-adrenoceptors will be decreased by 2.5 log units in the presence of 1 µmol·L−1 CGP20712A to 5.2, that is, to 6 µmol·L−1 which is close to the 5 µmol·L−1 (−)-isoprenaline used by Rochais et al. (2006). Thus, under the conditions of Rochais et al. (2006) it is conceivable that (−)-isoprenaline actually interacted mainly with β1-adrenoceptors and only to a lesser extent with β2-adrenoceptors.

We also found that the selective cilostamide-sensitive PDE3 blunting of the ICa-L response to (−)-adrenaline correlated with the small but significant potentiation by cilostamide of the β2-adrenoceptor-mediated inotropic effects of (−)-adrenaline (Figs 4, 5, Table 1) on both right as well as left ventricle and were accompanied by hastened relaxation in left ventricle (Figs 6 and 7). If the small potentiation were solely due to enhanced Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release from RyR2 channels, relaxation should not have been hastened. However, not only cilostamide, but even rolipram induced (−)-adrenaline to hasten relaxation (Figs 6 and 7), so that PKA-catalysed phosphorylation of phospholamban seems to have occurred when either PDE3 or PDE4 were inhibited. Rolipram only induced (−)-adrenaline to hasten relaxation but not to enhance ventricular ICa-L or potentiate the inotropic effects through β2-adrenoceptors of left ventricular papillary muscles, suggesting that the relevant PDE4 is hydrolyzing cAMP near phospholamban but perhaps not near the Ca2+ channels or RyR2 channels.

The predominant control of β2-adrenoceptor-mediated inotropic effects of (−)-adrenaline by PDE3 in rat ventricle is similar to the exclusive control by PDE3, but not PDE4, encountered in human atrium (Christ et al., 2006b).

Concurrent cilostamide and rolipram caused marked potentiation of the ventricular inotropic effects of (−)-adrenaline through β2-adrenoceptors. Cyclic AMP, accumulating after cilostamide-evoked PDE3 inhibition during β2-adrenoceptor stimulation, may have overflowed its normal limits and reached compartments, including Ca2+ channels and RyR2 channels in which PDE4 could be phosphorylated and activated by PKA, thus hydrolyzing cAMP (MacKenzie et al., 2002; Leroy et al., 2008) and reducing its levels at both ICa-L channels and proteins involved in enhancing contractile force (Fig. 11D). Concurrent inhibition of PDE3 and PDE4 would therefore preserve large amounts of cAMP which would diffuse to produce PKA-catalysed phosphorylation of ICa-L and of proteins, including RyR2 Ca2+ release channels and phospholamban, involved in the positive inotropic effects of (−)-adrenaline through β2-adrenoceptors.

(−)-Noradrenaline-evoked increases of atrial ICa-L through β1-adrenoceptors are only increased by the concurrent inhibition of PDE1, PDE2 and PDE3. Discrepancies with inotropic effects

The small increase in ICa-L by (−)-noradrenaline, mediated through β1-adrenoceptors, was unaffected by EHNA, cilostamide, rolipram or concurrent cilostamide + rolipram, inconsistent with control by PDE2, PDE3 or PDE4. However, both IBMX and concurrent EHNA, cilostamide and rolipram markedly increased the (−)-noradrenaline response, suggesting that at the L-type Ca2+ channel domain the three PDE isoenzymes act in concert to blunt the response to (−)-noradrenaline.

The function of PDE isoenzymes controlling atrial ICa-L responses to (−)-noradrenaline is fundamentally at variance with the atrial inotropic responses to (−)-noradrenaline, which are selectively controlled by PDE4. Inhibition of PDE2 is mandatory to permit effects of concomitant inhibition of PDE3 and PDE4 on the level of ICa-L. In contrast, it is also unlikely that PDE2 is modulating atrial positive inotropic responses to (−)-noradrenaline and (−)-adrenaline through β1-adrenoceptors and β2-adrenoceptors, respectively, because responses and potencies in the presence of IBMX were not significantly greater than in the presence of concurrent cilostamide + rolipram (Fig. 3, Table 1). The discrepancy could be related to structural peculiarities of the atrial myocardium. Unlike ventricular myocardium, atrial myocardium virtually lacks t-tubules which in ventricle couple to the junctional SR and form the SR network around the myofibrils (Hüser et al., 1996; Lipp et al., 1996; Yamasaki et al., 1997). In atrial myocardium, slender sarcotubular connections are connected to Z-tubules (Yamasaki et al., 1997). Due to inhomogenous Ca2+ increases upon depolarization, Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release largely fails in deeper layers of the atrial myocytes (Mackenzie et al., 2001). We speculate that the selective control by PDE4 of the positive inotropic effects of (−)-noradrenaline is related to the localisation of this isoenzyme at or near the SR, as also proposed for ventricular myocardium.

Are regional differences in cardiac β2-adrenoceptor function related to both PDE activity and receptor density?

In the absence of PDE inhibition, (−)-adrenaline elicited weak cardiostimulation through β2-adrenoceptors of sinoatrial node and both right and left ventricles but not at all in the left atrium (Figs 1–5). Concurrent cilostamide and rolipram did not potentiate the positive chronotropic effects of (−)-adrenaline and only caused an increase in f2 to 0.23 from 0.08 in the absence of the PDE inhibitors (Table 1). On the left atrium, in contrast, combined cilostamide and rolipram uncovered potent positive inotropic effects of (−)-adrenaline with f2 = 0.26, mediated through β2-adrenoceptors. On the ventricles, the effect of IBMX (10 µmol·L−1) or the combination of cilostamide and rolipram potentiated the effects of (−)-adrenaline and greatly enhanced f2 to 0.82–0.84 and 0.92–0.98 respectively (Table 1). PDE3 and PDE4, acting in concert, appeared to hydrolyze inotropically relevant cAMP effects elicited by (−)-adrenaline through β2-adrenoceptors in ventricle and left atrium but hardly affected chronotropically relevant cAMP in sinoatrial cells. Can the differences between cardiac regions in the magnitude of the β2-adrenoceptor fraction f2 after combined inhibition of PDE3 and PDE4 be explained in part by differences in regional β2-adrenoceptor densities? The literature on β2-adrenoceptor density, compared with β1-adrenoceptor density, in the rat heart, summarized in Table 2, reveals that the sinoatrial node has the lowest density of β2-adrenoceptors amounting only to about 25–30% of atrial or ventricular β2-adrenoceptors. Furthermore, a large fraction of rat right atrial β2-adrenoceptor population is not located in myocytes but in ganglion cells (Mysliveček et al., 2006). Yet, (−)-adrenaline enhanced sinoatrial beating through β2-adrenoceptors (This report; Kaumann, 1986) even in the absence of PDE inhibitors while left atrial β2-adrenoceptors only reveal inotropic function when both PDE3 and PDE4 are inhibited, despite the fourfold greater β2-adrenoceptor density, relative to β1-adrenoceptors. Clearly the minor β2-adrenoceptor-mediated tachycardia is conspicuous, despite the very low receptor density, because it is unaffected by PDEs. Ventricular β2-adrenoceptor function after concomitant cilostamide and rolipram is even more marked than that of left atrial β2-adrenoceptors under this condition, despite the similar β2/β1-adrenoceptor proportion in both regions. Physiological and anatomical differences between left atrium and ventricle may account for the difference in β2-adrenoceptor function, even after combined inhibition of PDE3 and PDE4.

Table 2.

Densities of β1- and β2-adrenoceptors (as % total) in rat cardiac regions

| Tissue | β1-Adrenoceptor | β2-Adrenoceptor | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sinoatrial node | 93.3 | 6.8 | Matthews et al. (1996) |

| Atrium | 74.3 | 25.7 | Mysliveček et al. (2003) |

| Left ventricle | 81.5 | 18.5 | Witte et al. (2000) |

| Right ventricular papillary muscle | 80.4 | 19.7 | Matthews et al. (1996) |

| Ventricles | 79.0 | 21.0 | Mysliveček et al. (2003) |

| Ventricles | 73.0 | 27.0 | Kitagawa et al. (1995) |

| Ventricular myocytes | 90.0 | 10.0 | Kitagawa et al. (1995) |

| Ventricles | 70.0 | 30.0 | Mauz and Pelzer (1990) |

| Ventricular myocytes | 100 | 0 | Mauz and Pelzer (1990) |

Enzymatic disaggregation of rat ventricular myocytes markedly reduced (Kitagawa et al, 1995) or even made undetectable β2-adrenoceptors (Mauz and Pelzer, 1990) compared with intact ventricle (Table 2). The reduced ventricular β2-adrenoceptor density, compared with β1-adrenoceptor density, in rat ventricular myocytes, may explain the high (−)-adrenaline concentration used (10 µmol·L−1) to unambiguously demonstrate increases in ICa-L through β2-adrenoceptors. Our failure to detect effects on ICa-L by (−)-adrenaline through β2-adrenoceptors of atrial myocytes could also be due to further reduction of the low receptor density by enzymatic disaggregation.

Conclusions

The PDE4 reduced basal sinoatrial beating rate but neither PDE3 nor PDE4 affected the chronotropic potencies of (−)-noradrenaline and (−)-adrenaline through β1- and β2-adrenoceptors, respectively, suggesting that the cAMP hydrolysis by PDE4 controlled beating rate in a compartment distinct from the region at which β-adrenoceptor activation modified ionic channel activity and Ca2+ cycling leading to tachycardia. PDE4 but not PDE3 reduced the atrial and ventricular inotropic effects of (−)-noradrenaline through β1-adrenoceptors. The β1-adrenoceptor-mediated increases of ventricular ICa-L were blunted by both PDE3 and PDE4 at the sarcolemmal domain but increases in contractile force are blunted only by PDE4, suggesting that cAMP in the β1-adrenoceptor/PDE3/Ca2+channel compartment does not reach proteins that produce increases in contractility such as RyR2 channels and phospholamban (Fig. 11). PDE3, but not PDE4 alone, reduced both increases in ICa-L and ventricular positive inotropic effects of (−)-adrenaline through β2-adrenoceptors. However, not only PDE3 but also PDE4 appeared to prevent hastening of relaxation by (−)-adrenaline though β2-adrenoceptors. Concurrent inhibition of PDE3 and PDE4 uncovered left atrial inotropic effects of (−)-adrenaline through β2-adrenoceptors and markedly potentiated ventricular inotropic effects of (−)-adrenaline mediated through β2-adrenoceptors. PDE3 and PDE4 protected the rat heart against ventricular and left atrial overstimulation but not against tachycardia through β1- and β2-adrenoceptors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Romy Kempe and Annegret Häntzschel for excellent technical assistance.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ICa-L

(L-type calcium current)

- CGP20712A

(2-hydroxy-5-[2-[[2-hydroxy-3-[4-[1-methyl-4-(trifluoromethyl)-1H-imidazol-2-yl]phenoxy]propyl]amino]ethoxy]-benzamide)

- EHNA

Erythro-9-[2-Hydroxy-3-nonyl]adenine

- IBMX

3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine

- ICI118551

(1-[2,3-dihydro-7-methyl-1H-inden-4-yl)oxy-3-[(1-methylethyl)amino]-2-butanol)

- PDE

phosphodiesterase

Conflicts of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC), 3rd edition (2008 revision) Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153(Suppl.)(2):S1–S209. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christ T, Wettwer E, Dobrev D, Adolph E, Knaut M, Wallukat G, et al. Autoantibodies against the β1-adrenoceptor from patients with dilated cardiomyopathy prolong action potential duration and enhance contractility in isolated cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:1515–1525. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christ T, Schindelhauer S, Wettwer E, Wallukat G, Ravens U. Interaction between autoantibodies against the β1-adrenoceptor and isoprenaline in enhancing L-type Ca2+ current in rat ventricular myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006a;41:716–723. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christ T, Engel A, Ravens U, Kaumann AJ. Cilostamide potentiates more the positive inotropic effects of (−)-adrenaline through β2-adrenoceptors than the effects of (−)-noradrenaline through β1-adrenoceptors in human atrial myocardium. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2006b;374:249–253. doi: 10.1007/s00210-006-0119-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFrancesco D, Tortora P. Direct activation of cardiac pacemaker channels by intracellular cyclic AMP. Nature. 1991;351:145–147. doi: 10.1038/351145a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischmeister R, Castro LRV, Abi-Gerges A, Rochais F, Jurevicius J, Leroy J, et al. Compartmentation of cyclic nucleotide signalling in the heart. The role of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases. Circ Res. 2006;99:816–828. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000246118.98832.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galindo-Tovar A, Kaumann AJ. Phosphodiesterase4 blunts inotropism and arrhythmias but not sinoatrial tachycardia of (−)-adrenaline mediated through mouse cardiac β1-adrenoceptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:710–720. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gettys TW, Blackmore PF, Redmon JB, Beebe SJ, Corbin JD. Short-term feedback regulation of cAMP by accelerated degradation in rat tissues. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:333–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]