Abstract

Aims

Achieving abstinence in the treatment of marijuana dependence has been difficult. To date the most successful treatments have included combinations of motivation enhancement treatment (MET) plus cognitive-behavioral coping skills training (CBT) and/or contingency management (ContM) approaches. Although these treatment approaches are theoretically based, their mechanisms of action have not been fully explored. The purpose of the present study was to explore mechanisms of behavior change from a marijuana treatment trial in which cognitive-behavioral treatment (CBT) and contingency management (ContM) were evaluated separately and in combination.

Design

A dismantling design was used in the context of a randomized clinical trial.

Setting

The setting was an outpatient treatment research facility located in a university medical center.

Participants

Participants were 240 adult marijuana smokers, meeting criteria for cannabis dependence.

Interventions

Participants were assigned to one of four 9-week treatment conditions: a case management control condition, MET/CBT coping skills training, contingency management (ContM), and MET/CBT+ContM.

Measurements

Outcome measures were total 90-day abstinence, recorded every 90 days for 12 months posttreatment.

Findings

Regardless of treatment condition, abstinence in near-term follow-ups was best predicted by abstinence during treatment, but long-term abstinence was predicted by use of coping skills and especially by posttreatment self-efficacy for abstinence.

Conclusions

It was concluded that the most efficacious treatments for marijuana dependence are likely to be those that increase self-efficacy.

Keywords: Marijuana dependence, contingency management, cognitive-behavioral treatment, self-efficacy, coping skills, treatment mechanisms

Marijuana is the most widely used illicit drug in the U.S.A. [1]. Despite recent attention to the treatment of marijuana dependence (e.g., [2]), prolonged abstinence has been difficult to achieve [2, 3]. There is thus a pressing need to determine what mechanisms of treatment lead to behavior change in this population.

Several treatment strategies offer promise in the treatment of marijuana dependence, namely cognitive-behavioral coping skills training (CBT), motivational enhancement (MET), contingency management, or a combination of these. In the largest controlled trial of treatment for marijuana dependence to date, the multi-site Marijuana Treatment Project (MTP) showed results indicating that nine sessions of combined MET and CBT were superior to two sessions of MET, and both were superior to a delayed treatment control group [2]. The highest abstinence rate achieved was 23% at 4-month follow-up in the MET/CBT condition, declining to 15% at 9 months.

Contingency management has been tested in studies by Budney and colleagues. Budney, Higgins, Radonovich, and Novy [4] found that MET/CBT, plus vouchers awarded contingent upon negative urines, produced more weeks of continuous abstinence from marijuana during the 14-week treatment period, and greater abstinence at the end of treatment (35%), than did a 4-session MET condition or a 14-session MET/CBT condition. There was no long-term follow-up, however.

Budney, Moore, Rocha and Higgins [5] compared cognitive-behavioral therapy, abstinence-based voucher incentives, or a treatment combining CBT with abstinence-based vouchers. Cannabis-dependent adults in the vouchers-only condition achieved the longest during-treatment abstinence. The best abstinence during the follow-up year was achieved by those in the CBT + Vouchers condition: 37% reported abstinence at a 12-month follow-up versus 17% in the vouchers-only condition. The authors concluded that early abstinence was a function of contingency management procedures, and that skills training was important in maintaining that effect.

Similar results were obtained in a comparable study by Kadden, Litt, Kabela-Cormier and Petry [6], referred to as MTP2, which was intended to maximize treatment effectiveness by combining MET/CBT and contingency management. Participants were adult marijuana smokers assigned to one of four 9-week treatment conditions: case management control condition (CaseM), MET/CBT, contingency management (ContM), and MET/CBT+ContM. Results indicated that, initially, all treatment conditions yielded similar decreases in marijuana use. At later follow-ups (11 and 14 months), the MET/CBT+ContM combination was associated with the highest rates of abstinence.

Mechanisms of Treatment

CBT, MET, and ContM presumably employ different, though complementary, mechanisms to achieve treatment gains. Cognitive-behavioral treatment is founded on the assumption that those who relapse lack the skills to deal with the affective, cognitive and environmental cues that trigger drug use, and/or lack the skills to maintain abstinence. The aim of CBT is to provide the person with skills to gain abstinence and to cope with life stressors and high-risk situations [3, 7]. To the extent that skills are developed and practiced, success experiences should lead to increased self-efficacy for coping, that will set the stage for greater use of coping behavior, resulting in greater abstinence over time (e.g., [8]).

Recent studies of mechanisms of change in the treatment of addictive behaviors have raised questions about how cognitive-behavioral treatments effect long-term change. Morgenstern and Longabaugh [9] reviewed the literature on proposed mechanisms of action of CBT for treatment of alcohol dependence. Only one of ten studies provided evidence for a mediational role of coping skills in improving outcomes. In the other nine studies, CBT either did not enhance coping to a greater degree than a comparison condition, or coping skills were unrelated to outcomes. In a study of CBT for alcohol dependence conducted by our group [10], CBT failed to improve coping more than a comparison condition.

Carroll [11] suggested that CBT-based approaches yield long-term improvements in substance use because patients continue to develop coping strategies after treatment is finished. Indeed, she describes the “delayed emergence” of abstinence, which she attributes to the “implementation of generalizeable coping skills.” Similar conclusions have been drawn by others (e.g., [12]). However, few studies have actually measured use of coping skills at extended follow-up points, so the delayed adoption of additional coping skills has not been substantiated. The mechanisms of action of CBT are thus still unclear.

MET is a non-confrontational approach that seeks to help patients resolve ambivalence about their drug use, and thereby develop motivation to change behavior [13]. Here, too, actual mechanisms of action are not known. So far few studies have evaluated changes in motivation as a function of motivational interviewing, and some studies have indicated that motivational interviewing does not lead to progression through the stages of change model (e.g., [14]).

Contingency management procedures treat abstinence behavior as an operant that is susceptible to reinforcement. In this model the probability of abstinence increases with reinforcement for abstinent behavior. Short-term efficacy of contingency management appears to be the result of two occurrences: increased retention in treatment, and enhanced abstinence during treatment (see [15, 16] for reviews). Despite evidence that abstinence during treatment is the best predictor of longer term outcomes [17, 18], it is not clear whether contingency management results in long-term abstinence, or changes in coping behaviors.

Mechanisms of Change in Marijuana Treatment

Few studies have explored the mechanisms of treatments for marijuana dependence. Litt, et al. [19] examined the role of coping skills and cognitive constructs as mediators of treatment outcome in the multi-site Marijuana Treatment Project (MTP) trial. Consistent with findings by Morgenstern and Longabaugh [9] and Litt et al. [10] for alcohol treatment, the results from MTP indicated that marijuana outcomes out to 15 months were predicted by the use of coping skills, but that the coping skills-oriented MET/CBT treatment did not result in greater coping skills acquisition than did the MET comparison treatment in which no skills were explicitly taught. Self-efficacy, or confidence in the ability to refrain from smoking, appeared to be a partial mediator of treatment outcome: increase in self-efficacy from pre- to posttreatment was a more powerful predictor of decrease in drug use over the follow-up year than was coping skills change.

Thus there is some evidence that self-efficacy and use of coping skills may be mechanisms of behavior change in marijuana treatment, particularly in the long term, but it is not clear whether these play a role in treatments that employ contingency management. The purpose of the present study was to explore the mechanisms of treatment-related change in the use of marijuana in the MTP2 trial [6]. In that trial all treatment conditions yielded similar decreases in marijuana use up to 8 months after intake, but the treatments incorporating MET/CBT yielded greater abstinence in the longer term (up to 14 months post intake).

It was hypothesized that the CBT treatments in the MTP2 trial would result in increased coping and increased self-efficacy for abstinence, compared to a Case Management control condition, and that increased coping and self-efficacy would predict outcome at the follow-ups. We also tested the idea that CBT would yield increases in use of coping skills at later time points, as suggested by Carroll [11]. Finally, it was hypothesized that contingency management would result in increased abstinence and increased self-efficacy during treatment, compared to other treatments, but not necessarily in coping skills changes or lasting abstinence.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 240 men and women, recruited via newspaper and radio advertisements, who met DSM-IV criteria for current Cannabis Dependence. Of 606 people screened, 485 were eligible, 8.9% were excluded for concurrent alcohol or drug dependence, and 245 dropped out prior to randomization, primarily due to loss of interest. The patient sample resembled that seen in the Marijuana Treatment Project [2]. Most (71%) were male, with an average age of 33 years. Sixty percent were white, 73% were employed, and the sample as a whole had 13 years of schooling on average. The sample reported experiencing over 13 marijuana-related problems, and smoking on 89% of days in the 90 days prior to treatment intake. Of the 240 who provided baseline data, 218 (91%) provided posttreatment data, and 200 (83%) provided data at 14 months. Participants were asked not to engage in other treatments for marijuana dependence while receiving the study treatment, but they could engage in other psychotherapy for up to two visits per month. The mean number of days of outside treatment for any reason at any follow-up point was 1.2. Further details regarding recruitment, randomization, and considerations of sample size and power are provided in Kadden et al. [6].

Measures and Instruments

Substance use

The timing of administration of all instruments is shown in Table 1. In-person assessments were conducted at intake, posttreatment, and at 8 and 14 months after intake. Telephone assessments took place at months 5 and 11. Participants were paid $50 for each in-person follow-up, and $20 for telephone follow-ups. The Time Line Follow-Back (TLFB) interview gathered marijuana, other drug, and alcohol frequency-of-use data for each day of the 90 days prior to intake and each follow-up. The TLFB has good test-retest reliability, and validity for verifiable events over long time periods [20].

Table 1.

Timing of Administration of Treatment Process Measures

| Measure | Baseline | Post treatment | 5 Mo* | 8 Mo | 11 Mo* | 14 Mo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timeline Follow-Back (TLFB) | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Coping Strategies Scale | X | X | X | X | ||

| Readiness to Change | X | X | ||||

| Self-Efficacy | X | X |

Assessments conducted by telephone.

Mechanism variables

A number of variables are presumed to change as a function of treatment and to play a role in treatment outcome. The first of these is retention in treatment, which was operationalized as the number of treatment sessions attended. Another variable that has figured prominently in studies of long-term outcome is continuous abstinence during treatment. This was assessed using the TLFB administered at the posttreatment follow-up.

Among the cognitive variables that are presumed to be mechanisms of change is motivation, or readiness to change. Readiness to change marijuana use was measured using the Readiness to Change Questionnaire (RTCQ; [21]), a 12-item Likert-scaled questionnaire based on Prochaska and DiClemente's stages-of-change model. The RTCQ was modified to refer to marijuana use, and an overall index of readiness was created using the Action subscale as computed by DiClemente, et al. [22]. This subscale had an internal consistency reliability of alpha=.72. To evaluate change in readiness from pre- to posttreatment, residualized change scores were calculated [23], and we used Levene's test for homogeneity of variance [24] to ensure that the variances of RTCQ scores at baseline and posttreatment were not significantly different.

Self-efficacy for stopping marijuana use was measured using a 20-item modification of a smoking cessation self-efficacy questionnaire [25], adapted by Stephens, Wertz and Roffman [26, 27] to refer to abstinence from marijuana. Participants indicated on a 7-point scale their confidence in their ability to resist smoking in a variety of interpersonal and intrapersonal situations. In the present study the internal consistency reliability of the scale was alpha=.92. Residualized change scores for self-efficacy were calculated in the same manner as for RTCQ.

Coping skills were assessed using the Coping Strategies Scale (CSS; [10]), adapted from the Processes of Change Questionnaire [22, 28]. The 40 items were reworded to refer to marijuana, and eight items were added to reflect specific skills taught in coping skills treatment. Participants rated the frequency with which they used each of the 48 strategies to help them abstain from using marijuana since the last follow-up, on a 4-point scale. The internal reliability of the 48 items was alpha = .92. Total coping was calculated by averaging all the items of the scale, so that the Total score ranged from 1 - 4. Changes in coping skills use over the follow-ups were calculated as residualized change scores from baseline.

Treatment Interventions

All the interventions, except ContM-only, were conducted in 60-minute individual outpatient sessions, employing manuals that provided specific guidelines to the therapists. All interventions were scheduled to last nine sessions and were provided free of charge. Treatments were conducted by experienced therapists. All therapists conducted all of the treatments.

The MET/CBT intervention consisted of two sessions of motivational enhancement therapy followed by seven sessions of coping skills training. The motivational enhancement component, derived from the Project MATCH MET manual [29], involves an empathic style designed to help participants resolve ambivalence, develop motivation to change, and set goals for behavior change. Sessions 3 through 9 involved cognitive-behavioral skills training, based on a manual developed for alcoholism treatment research [30]. The focus was on skills to achieve abstinence and cope with high-risk situations.

ContM was both a stand-alone intervention and, in another condition, was combined with MET/CBT. Because ContM required verification of abstinence, participants in all conditions provided a urine specimen to be tested for marijuana at each treatment session. Participants in both of the ContM conditions received a voucher if they submitted a negative urine specimen. The ContM-only group did not receive any other treatment. They met for 9 weeks, for about 15 minutes each week, with a Research Assistant who collected a urine specimen and managed the voucher system. The initial voucher rate was $10 for the first clean urine, and escalated by $15 per week for each successive marijuana-free urine specimen. A patient who had all clean urines would receive total earnings of $390. If a participant was positive for marijuana, no reward was given and the voucher value was reset to $10 for the next marijuana-negative urine. Vouchers could be redeemed for retail goods or services that were not drug-related [17, 31, 32].

The Case Management intervention was based on that used in the Marijuana Treatment Project [33]. It was supportive in nature, designed to help participants with problems of daily living that may be due to, or contribute to, their marijuana use. Efforts were made to minimize overlap with the MET/CBT and ContM interventions, and no skills relevant to managing substance use were taught.

Data Analysis

The primary outcome measure was continuous abstinence for the 90-day period prior to each follow-up (scored 0 or 1 for each participant), derived from the TLFB. To determine what behavior-change mechanisms were operating in this trial we examined three basic approaches:

(a) Marijuana outcomes over time as a function of Treatment

Analyses of 90-day abstinence over time were conducted using a generalized estimating equations model (GEE; Proc Genmod, [34]), as detailed in Kadden et al.[6]. This approach was used because it takes advantage of all available data (N=240) by using maximum likelihood estimation procedures to estimate the parameters of the multivariate model [35, 36].

(b) The relationship between treatment conditions and presumed mediators of outcomest

Oneway analysis of variance was used to determine if retention in treatment (treatment sessions attended) and days of continuous abstinence during treatment varied by treatment condition. Mixed model regression models (PROC MIXED; [34]) were used to determine if the different treatment conditions produced different levels in the other mediating variables at posttreatment, controlling for baseline levels. Variables tested in these models were readiness for change, self-efficacy for abstinence, and use of coping skills.

(c) Examination of mediators of treatment effects

As a first step, logistic regression was used to evaluate the effect of treatment and process variables on posttreatment abstinence outcome. Posttreatment abstinence was treated separately from outcomes at later time points because it was not possible to determine the direction of causality between posttreatment abstinence and process variables evaluated at posttreatment. Two regression models were evaluated. In the first, only baseline proportion days abstinent (PDA; an indicator of pretreatment severity) and three dummy variables representing the experimental treatment conditions (MET/CB; ContM; and MET/CB + ContM) were entered. In the second model the baseline PDA covariate was entered, the treatment dummy variables were entered, and baseline and posttreatment values for the process variables were entered. The two models provided an examination of treatment effects, and the effect of mediating variables on those treatment effects.

Structural equation modeling with binary outcomes (e.g., [37]) conducted using MPlus software [38] was used to evaluate the joint influence of treatment conditions (again expressed as three dummy variables) and mediating variables on 90-day abstinence outcomes measured at months 5 through 14. The process variables of readiness to change, self-efficacy, and coping skills use were included in the models as residualized change scores. Abstinence at posttreatment was included as a predictor of later outcomes.

Results

Marijuana Outcomes Over Time as a Function of Treatment

A detailed discussion of treatment outcomes may be found in Kadden et al. [6]. Results from the GEE analysis on 90-day abstinence outcomes showed a main effect for Treatment condition [χ2(3) = 12.92; p < .01], with relatively high levels of 90-day abstinence found for the MET/CBT+ContM condition at the 11 and 14-month time points (see Table 2). There was no Time effect, and no Treatment X Time interaction. The ContM condition initially yielded relatively high rates of abstinence (about 22% reporting continuous abstinence at posttreatment). Abstinence rates for the ContM condition declined after 5 months.

Table 2.

90-Day Abstinence Rates (% Abstinent) at Each Follow-up Period by Treatment Condition

| Treatment Condition | Baseline | Post treatment | 5 Mo | 8 Mo | 11 Mo | 14 Mo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CaseM | 0.0 | 11.1 | 13.0 | 15.1 | 15.4 | 19.2 |

| MET/CBT | 0.0 | 12.7 | 21.8 | 18.5 | 15.4 | 20.4 |

| ContM | 0.0 | 22.0 | 18.4 | 12.2 | 12.5 | 12.5 |

| MET/CB+ContM | 0.0 | 18.6 | 23.7 | 23.2 | 25.3 | 27.6 |

Presumed Mechanisms of Change

Retention in treatment and continuous abstinence during treatment

Two variables have been cited as being especially important to the success of contingency management-based treatment programs: retention in treatment, and continuous abstinence during treatment [17]. One-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were conducted to determine if treatment assignment had an influence on retention. Results of these analyses indicated no main effect for Treatment condition on retention in treatment (see Table 3). Patients in all conditions attended 5 sessions on average. A priori contrasts also failed to show significant between-groups differences.

Table 3.

Means and Standard Deviations of Two Variables Central to Efficacy of Contingency Management: Treatment Retention and Continuous Abstinence. (N=240)

| Variable | Treatment Condition |

F Treatment (df=3,236) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CaseM | MET/CB | ContM | MET/CB/ContM | ||

| M | M | M | M | ||

| (SD) | (SD) | (SD) | (SD) | ||

| Treatment Sessions | 4.7 | 4.9 | 5.5 | 5.6 | 1.06 |

| Attended | (3.5) | (3.3) | (3.8) | (3.6) | |

| Days Continuous | 17.27 | 19.25 | 28.23 | 25.80 | 1.82 |

| Abstinence | (25.88) | (27.24) | (30.41) | (31.97) | |

| During Treatment a,b | |||||

Note. Linear contrast CaseM < MET/CB < ContM < MET/CB/ContM, p < .05.

Contrast of ContM conditions v. non-ContM Conditions, p < .05 .

An ANOVA also failed to show a main effect for treatment in Days of Continuous Abstinence during the treatment period (see Table 3). Two a priori contrasts did show significant systematic effects by treatment condition, however. The finding of a significant contrast of ContM treatments (ContM, MET/CBT+ContM) v. non-ContM treatments (CaseM, MET/CBT) indicated that contingency management was performing as expected, yielding abstinence by reinforcing delivery of clean urines [t (224) = 2.28; p < .05].

Readiness, self-efficacy, and coping skills

Table 4 shows the changes (pre-post) in each of these variables as a function of treatment. For each of the three linear mixed models a significant Time effect emerged, indicating higher scores on all variables at posttreatment. However, no main effect for Treatment emerged, and there was no significant Treatment X Time interaction.

Table 4.

Means and Standard Deviations of Key Elements ofCBT: Readiness for Change, Self-Efficacy, and Coping Skills

| Variable | Treatment Condition | Effects Tested (F values) (denominator df= 236) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CaseM | MET/CBT | ContM | MET/CB+ContM | Treatment | Time | Treatment X ime | |||||

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | ||||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | ||||

| RTC | 13.84 | 14.29 | 14.76 | 15.59 | 14.32 | 15.82 | 14.63 | 15.71 | 1.37 | 5.76* | 0.29 |

| (2.39) | (4.14) | (3.41) | (4.44) | (4.11) | (4.54) | (3.50) | (3.32) | ||||

| Self- | 65.56 | 83.81 | 65.84 | 91.79 | 70.27 | 90.83 | 65.29 | 81.02 | 1.04 | 66.99** | 0.80 |

| Efficacy | (25.14) | (36.19) | (26.10) | (33.38) | (24.54) | (30.49) | (26.89) | (32.67) | |||

| CSS | 2.16 | 2.45 | 2.05 | 2.50 | 2.14 | 2.46 | 2.18 | 2.58 | 0.48 | 67.27** | 0.64 |

| (0.47) | (0.63) | (0.48) | (0.61) | (0.51) | (0.61) | (0.47) | (0.62) | ||||

Note. p<.05

p<.001

RTC = Readiness to Change Score. CSS = Coping Strategies Scale Total Score.

Repeated CSS scores were analyzed using mixed model regression to evaluate the hypothesis that use of coping skills increases over time as a result of cognitive-behavioral coping skills-based treatment (e.g., [11]). Dependent variables were CSS scores collected at posttreatment, and at the 8 and 14-month follow-ups. Baseline CSS was used as a covariate. Results showed no significant effect for Treatment condition or for the interaction of Treatment X Time. There was, however, a significant main effect for Time [F (2, 365) = 27.52; p < .001)], such that total coping scores decreased slightly from posttreatment through the 14-month follow-up. Figure 1 illustrates the Total Coping scores over time by Treatment condition.

Figure 1.

Total Coping scores by treatment condition over time.

Treatment Effects and Presumed Mechanisms in Marijuana Abstinence

Posttreatment abstinence

Table 5 presents the results of the two logistic regression models analyzing treatment and mediator effects on posttreatment abstinence. Results of Model 1, testing treatment conditions alone (each experimental treatment against the case management control), showed a main effect for the ContM condition. When mediating variables are added in Model 2, the ContM treatment effect disappears. Two variables considered to be process variables were associated with continuous abstinence during treatment. Not surprisingly, Days of Continuous Abstinence in treatment was associated with total abstinence in that period, as was Readiness for Change.

Table 5.

Predictors of Abstinence at Posttreatment by Logistic Regression Analysis. (N=198)

| Model | Predictor | B | se | Wald χ2 | Odds Ratio | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PDA Baseline | 0.90 | .39 | 5.47* | 2.46 | 1.16 | 5.24 |

| Treatment: MET/CBa | 0.24 | .60 | 0.16 | 1.27 | 0.39 | 4.12 | |

| Treatment: ContMa | 0.67 | .56 | 3.41* | 1.95 | 1.65 | 5.85 | |

| Treatment: MET/CB + ContMa | 0.54 | .55 | 0.96 | 1.72 | 0.58 | 5.10 | |

| 2 | PDA Baseline | 0.54 | 1.44 | 0.14 | 1.72 | 0.10 | 12.72 |

| Treatment: MET/CBa | 0.41 | 2.68 | 2.47 | 1.51 | 0.35 | 11.35 | |

| Treatment: ContMa | 2.49 | 2.48 | 2.27 | 12.11 | 0.30 | 22.40 | |

| Treatment: MET/CB + ContMa | 2.03 | 2.03 | 1.00 | 7.61 | 0.99 | 10.79 | |

| Readiness - Pretreatment | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.99 | 0.87 | 1.13 | |

| Self-Efficacy - Pretreatment | -0.05 | 0.03 | 2.97 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 1.01 | |

| Coping - Pretreatment | 0.27 | 0.11 | 3.20 | 1.31 | 0.98 | 1.61 | |

| Attendance in Treatment | 0.31 | 0.22 | 2.06 | 1.37 | 0.89 | 2.10 | |

| Days Abstinentb | 0.10 | 0.03 | 12.49*** | 1.11 | 1.05 | 1.18 | |

| Readiness - Posttreatment | 0.29 | 0.07 | 4.16* | 1.34 | 1.01 | 1.78 | |

| Self-Efficacy - Posttreatment | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 1.04 | |

| Coping - Postreatment | 0.08 | 0.07 | 1.21 | 0.93 | 0.80 | 1.06 |

Note: p<.05

p< .001

Treatment variables are dummy variables.

Days Abstinent = Days of Continuous Abstinence during Treatment

Abstinence months 5 - 14

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to model treatment and process variable effects on abstinence outcomes in months 5 - 14. Initially latent growth models were evaluated, in which the intercept and slope of abstinence over time were modeled as functions of treatment and process variables. When these models failed to converge, a structural path approach was taken, with abstinence outcomes used as latent variables. The patterns of abstinence seen in the raw proportions (see Table 2) led to the creation of Abstinence latent variables for follow-up months 5 - 8, and for follow-up months 11 - 14. Theta parameterization was used to correct confidence intervals in the binary outcomes models [39].

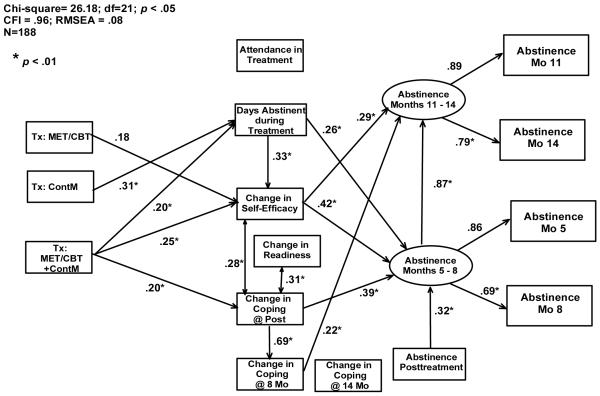

The initial path model evaluated was heavily saturated, with all logical paths hypothesized (e.g., paths showing subsequent measures predicting previous measures were not allowed). This model failed to converge. Nonsignificant paths were then eliminated, resulting in a converging model with extremely poor fit. Modification indices were then used to add (logical) paths to the model [40]. The final model is shown in Figure 2. Although this model does not provide an ideal fit to the data (the model chi-square value indicates a significant departure from the data structure), it is the best that could be logically represented from the data, and fit indices are acceptable.

Figure 2.

Diagram depicting results of final structural equation model showing interacting effects of treatment conditions and mediating variables on 90-day abstinence outcomes through months 5 - 14. Values shown are standardized path coefficients. CFI = Comparative Fit Index. RMSEA=Root Mean Square Error of Approximation.

Examination of Figure 2 shows no direct paths from any of the Treatment condition dummy variables to the Abstinence outcome latent variables. Instead, effects of treatment were mediated by other variables. In particular, abstinence at months 5 - 8 was predicted by abstinence at posttreatment, days of continuous abstinence during treatment, pre-post change in coping, and pre-post change in self-efficacy.

The treatments themselves appeared to operate as hypothesized, when other related variables were taken into account. The ContM condition was the most effective at promoting continuous abstinence during the treatment period, whereas the MET/CBT and MET/CBT + ContM conditions were most effective at increasing self-efficacy. The MET/CBT + ContM condition, which provided contingent reinforcement for abstinence during treatment, yielded the largest increases in coping, as long as the correlation with readiness to change was accounted for. Two variables, attendance in treatment and coping change at 14 months, dropped out of the analyses entirely. As for readiness to change, its contribution was at best indirect.

In contrast to the picture for early abstinence, abstinence at later time points (i.e., 11 and 14 months) was best predicted by pre-post change in self-efficacy and by pre- 8 month change in coping total score. The variable most associated with contingency management, days of continuous abstinence during treatment, failed to predict longer-term outcomes when other variables were also in the model. Days of continuous abstinence during treatment did, however, contribute to increased pre-post change in self-efficacy. Despite the decline in average coping scores over the follow-up periods, coping skills use predicted abstinence at 11 - 14 months. The most significant predictor of abstinence, throughout the follow-up period, was pre-post self-efficacy change.

Discussion

The present study sheds some light on the outcomes reported in the Kadden et al. [6] article. Initial abstinence was higher for those in the ContM condition, but over time the MET/CBT conditions (especially MET/CB + ContM) yielded greater abstinence. Although abstinence 5 to 8 months out was predicted by abstinence during treatment, long-term abstinence (11 to 14 months out) was accounted for in part by changes in coping and self-efficacy.

The Role of Self-Efficacy

To a considerable extent successful outcomes were related to change in self-efficacy, which was in part related to continuous abstinence during treatment. The findings raise the question as to what causes what: does increased self-efficacy lead to greater abstinence, or does abstinence lead to increases in self-efficacy? The answer may determine whether treatment should either focus on abstinence (as contingency management does) or on increasing confidence (as CBT tends to do).

Wong et al. [41] reported in a study of cocaine users that self-efficacy over time was a function of abstinence in the preceding follow-up period, but abstinence was not predicted by earlier self-efficacy, implying that achieving abstinence was the primary mechanism of change. In the present study, however, abstinence at later follow-up points was accounted for by pre-post change in self-efficacy, above and beyond that explained by days of continuous abstinence during treatment. This finding is more consistent with results found by Baer et al. [42], who reported that self-efficacy in cigarette smokers predicted later smoking abstinence even when previous abstinence was controlled for. The results in the present study suggest that both abstinence and self-efficacy should be emphasized in treatment, and that change in one leads to change in the other.

The present results are also consistent with findings reported by Litt et al. [19]. In that study, too, change in self-efficacy from pre- to posttreatment was predictive of later coping, and was also independently predictive of outcome. Thus the influence of self-efficacy on outcomes is not wholly mediated by coping behaviors (at least as we measured them). Self-efficacy increases apparently led to behavioral or affective changes (e.g., decreasing motivation to smoke) that we are not aware of.

An obvious conclusion suggested by the present results is that treatment should seek to maximize self-efficacy. According to social learning theory there are several potential sources for self-efficacy: information from others, experience, and physiological feedback. Empirical studies have shown that the most potent source of self-efficacy is the experience of mastery in a situation [22, 42-45]. From this perspective, successful behavioral performance should have a powerful impact on self-efficacy. Therefore the preferred treatment strategy would employ behavioral assignments designed to increase patients' coping repertoire and provide success experiences [3, 43, 46].

Contingency Management

The present study is the first to examine the cognitive and behavioral changes that accompany both cognitive-behavioral and contingency management treatments for marijuana dependence. Historically, mechanisms of contingency management treatments have not been extensively analyzed. It has been generally assumed that the mechanism of contingency management is obvious, namely positive reinforcement. However, contingency management may have a cognitive aspect as well.

Contingency management procedures that yield continuous abstinence may enable patients to recognize their ability to stay abstinent, thus providing mastery experiences that increase self-efficacy. This may have occurred to some extent in this study; self-efficacy did increase from pre-to-posttreatment, and that increase was related to abstinence achieved in the ContM treatments.

The failure of ContM-only to achieve lasting improvements in abstinence, however, may be the result of participants' attributions that their abstinence behavior was externally maintained by the reinforcements received. For self-efficacy to stay high, the person has to attribute behavioral accomplishments to his or her own efforts [47]. This may help explain why contingency management treatments appear to work best in combination with other treatments [4]; the additional treatment may help the individual attribute success experiences to their own efforts (e.g., skills development).

Coping Skills

The early use of coping skills was also a significant element in predicting long term outcomes. However, far from confirming Carroll's [11] hypothesis that coping skills-based treatments achieve long-term success through continued acquisition and use of skills, the current study found that use of coping skills declined somewhat over time. The reasons for this are not known. (Perhaps as a person becomes more accustomed to abstinence, fewer coping actions are necessary.) These results, along with others described, may indicate a need to more effectively develop coping ability and self efficacy.

Limitations and Conclusions

A significant limitation is that self-efficacy was only measured at pre- and posttreatment. A thorough understanding of a dynamic expectancy like self-efficacy would require measurement over multiple time points. Another problem may lie with our measurement of coping skills. Although the measure used here has proven reliability and predictive validity, it may not have captured all the coping behaviors that our patients actually used. A technology like experience sampling or daily recording, in which patients describe their ongoing coping behaviors, while minimizing errors of retrospection, is needed in this kind of research.

An obvious shortcoming is that the major analysis of this study, the path model, provided only in an imperfect fit with the data. This may be explained in part by trying to model binary outcomes, which can lead to inflated chi-squares [48], and by the lack of measured mediators at later follow-ups. Despite the significant chi-square, however, the high CFI and low RMSEA indicate that the model is acceptable [38].

In summary, the present study sought to examine the predictors of marijuana treatment outcome over time, and thereby develop an enhanced understanding of treatment mechanisms. The results indicated that early abstinence is predictive of near-term outcomes, but that long-term success is best predicted by self-efficacy and by coping skills. Most interesting (or troubling, depending on one's point of view) is that the mechanisms of treatment that are operative here were not treatment-specific; self-efficacy and coping skills were predictive of outcome regardless of treatment condition, and all treatment conditions yielded some increases in these. Early abstinence appeared to be important to the extent that it increased self-efficacy. We may have thus uncovered an important mechanism of contingency management treatments. These are not only theoretically interesting propositions, but also clinically useful insights that might help us develop more effective substance abuse treatments.

Acknowledgments

Support for this project was provided by grant R01-DA012728 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and in part by General Clinical Research Center grant M01-RR06192 from the National Institutes of Health. The authors would like to acknowledge the therapists: Aimee Markward, MS, CAC, Susan Sampl, PhD, and Jay Beatman, PsyD; and the Research Assistants: Priscilla Morse, Kara Dion, and Abigail Sama.

References

- [1].Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Results from the 2005 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Rockville, MD: 2006. Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-30, DHHS Publication No. SMA 06-4194. [Google Scholar]

- [2].The Marijuana Treatment Project Research Group Brief treatments for cannabis dependence: Findings from a randomized multisite trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:455–66. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Marlatt GA, Gordon JR. Relapse prevention: Maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors. Guilford; New York: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Budney AJ, Higgins ST, Radonovich KJ, Novy PL. Adding voucher-based incentives to coping skills and motivational enhancement improves outcomes during treatment for marijuana dependence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:1051–61. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.6.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Budney AJ, Moore BA, Rocha HL, Higgins ST. Clinical trial of abstinence-based vouchers and cognitive-behavioral therapy for cannabis dependence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:307–16. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.4.2.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kadden RM, Litt MD, Kabela-Cormier E, Petry NM. Abstinence rates following behavioral treatments for marijuana dependence. Addict Behav. 2007;32:1220–36. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Marlatt GA, George WH. Relapse prevention: introduction and overview of the model. Br J Addict. 1984;79:261–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1984.tb00274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Larimer ME, Palmer RS, Marlatt GA. Relapse prevention. An overview of Marlatt's cognitive-behavioral model. Alcohol Res Health. 1999;23:151–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Morgenstern J, Longabaugh R. Cognitive-behavioral treatment for alcohol dependence: a review of evidence for its hypothesized mechanisms of action. Addiction. 2000;95:1475–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.951014753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Litt MD, Kadden RM, Cooney NL, Kabela E. Coping skills and treatment outcomes in cognitive-behavioral and interactional group therapy for alcoholism. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:118–28. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.71.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Carroll KM. Relapse prevention as a psychosocial treatment: A review of controlled clinical trials. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1996;4:46–54. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Rosenblum A, Magura S, Palij M, Foote J, Handelsman L, Stimmel B. Enhanced treatment outcomes for cocaine-using methadone patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999;54:207–18. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00166-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to change addictive behavior. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Stotts AL, DeLaune KA, Schmitz JM, Grabowski J. Impact of a motivational intervention on mechanisms of change in low-income pregnant smokers. Addict Behav. 2004;29:1649–57. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Petry NM. A comprehensive guide to the application of contingency management procedures in clinical settings. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;58:9–25. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Petry NM, Simcic F., Jr. Recent advances in the dissemination of contingency management techniques: clinical and research perspectives. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;23:81–6. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00251-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Higgins ST, Alessi SM, Dantona RL. Voucher-based incentives. A substance abuse treatment innovation. Addict Behav. 2002;27:887–910. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00297-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Carroll KM, Easton CJ, Nich C, Hunkele KA, Neavins TM, Sinha R, et al. The use of contingency management and motivational/skills-building therapy to treat young adults with marijuana dependence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:955–66. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Litt MD, Kadden RM, Stephens RS. Coping and self-efficacy in marijuana treatment: results from the marijuana treatment project. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:1015–25. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten R, Allen J, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biochemical methods. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: 1992. pp. 41–71. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Rollnick S, Heather N, Gold R, Hall W. Development of a short 'readiness to change' questionnaire for use in brief, opportunistic interventions among excessive drinkers. Br J Addict. 1992;87:743–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1992.tb02720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].DiClemente CC, Carbonari JP, Zweben A, Morrel T, Lee RE. Motivation hypothesis causal chain analysis. In: Longabaugh R, Wirtz PW, editors. Project MATCH hypotheses: Results and causal chain analyses (NIH Publication No 01-4238) National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Bethesda, MD: 2001. pp. 206–22. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Cohen JC, Cohen P. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Zumbo BD. The simple difference score as an inherently poor measure of change: Some reality, much mythology. In: Thompson B, editor. Advances in social science methodology: A research annual. Vol 5. JAI Press; Greenwich, CT: 1999. pp. 269–304. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Curry SJ, Marlatt GA, Gordon J, Baer JS. A comparison of alternative theoretical approaches to smoking cessation and relapse. Health Psychol. 1988;7:545–56. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.7.6.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Stephens RS, Wertz JS, Roffman RA. Predictors of marijuana treatment outcomes: the role of self-efficacy. J Subst Abuse. 1993;5:341–53. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(93)90003-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Stephens RS, Wertz JS, Roffman RA. Self-efficacy and marijuana cessation: a construct validity analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63:1022–31. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.6.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Prochaska JO, Velicer WF, DiClemente CC, Fava J. Measuring processes of change: applications to the cessation of smoking. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:520–8. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.4.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Miller WR, Zweben A, DiClemente CC, Rychtarik RG. Project MATCH Monograph Series. Vol 2. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Rockville, MD: 1992. Motivational enhancement therapy manual: A clinical research guide for therapists treating individuals with alcohol abuse and dependence. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Monti PM, Abrams DB, Kadden RM, Cooney NL. Treating alcohol dependence: A coping skills training guide. Guilford Press; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Higgins ST, Budney AJ, Bickel WK, Foerg FE, Donham R, Badger GJ. Incentives improve outcome in outpatient behavioral treatment of cocaine dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:568–76. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950070060011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Petry NM, Alessi SM, Marx J, Austin M, Tardif M. Vouchers versus prizes: contingency management treatment of substance abusers in community settings. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:1005–14. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Steinberg KL, Roffman RA, Carroll KM, Kabela E, Kadden R, Miller M, et al. Tailoring cannabis dependence treatment for a diverse population. Addiction. 2002;97(Suppl 1):135–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.97.s01.5.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].SAS Institute . SAS/STAT software: changes and enhancements through V7 and V8. Cary, NC: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. New York Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42:121–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Muthen BO. Beyond SEM: General latent variable modeling. Behaviormetrika. 2002;29:81–117. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Muthh́en LK, Me BO. Mplus user's guide. Muthh́en & Muthh́en; Los Angeles, CA: 19982007. [Google Scholar]

- [39].MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling Methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Silvia ESM, MacCallum RC. Some factors affecting the success of specification searches in covariance structure modeling. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1988;23:297–326. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2303_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Wong CJ, Anthony S, Sigmon SC, Mongeon JA, Badger GJ, Higgins ST. Examining interrelationships between abstinence and coping self-efficacy in cocaine-dependent outpatients. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;12:190–9. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.12.3.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Baer J, Holt CS, Lichtenstein E. Self-efficacy and smoking reexamined; construct validity and clinical utility. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1986;54:846–52. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.6.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Annis HM, Davis CS. Self-efficacy and the prevention of alcoholic relapse: Initial findings from a treatment trial. In: Baker TB, Cannon DS, editors. Assessment and treatment of addictive disorders. Praeger Publishers; New York: 1988. pp. 88–112. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Annis HM, Davis CS. Assessment of expectancies. In: Donovan D, Marlatt GA, editors. Assessment of addictive behaviors. The Guilford Press; New York: 1988. pp. 84–111. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavior change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84:191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Curry S, Marlatt GA, Gordon JR. Abstinence violation effect: validation of an attributional construct with smoking cessation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1987;55:145–9. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.2.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]