Abstract

Pancreatic ductal epithelium produces a HCO3−-rich fluid. HCO3− transport across ductal apical membranes has been proposed to be mediated by both SLC26-mediated Cl−/HCO3− exchange and CFTR-mediated HCO3− conductance, with proportional contributions determined in part by axial changes in gene expression and luminal anion composition. In this study we investigated the characteristics of apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange and its functional interaction with Cftr activity in isolated interlobular ducts of guinea pig pancreas. BCECF-loaded epithelial cells of luminally microperfused ducts were alkalinized by acetate prepulse or by luminal Cl− removal in the presence of HCO3−-CO2. Intracellular pH recovery upon luminal Cl− restoration (nominal Cl−/HCO3− exchange) in cAMP-stimulated ducts was largely inhibited by luminal dihydro-DIDS (H2DIDS), accelerated by luminal CFTR inhibitor inh-172 (CFTRinh-172), and was insensitive to elevated bath K+ concentration. Luminal introduction of CFTRinh-172 into sealed duct lumens containing BCECF-dextran in HCO3−-free, Cl−-rich solution enhanced cAMP-stimulated HCO3− secretion, as calculated from changes in luminal pH and volume. Luminal Cl− removal produced, after a transient small depolarization, sustained cell hyperpolarization of ∼15 mV consistent with electrogenic Cl−/HCO3− exchange. The hyperpolarization was inhibited by H2DIDS and potentiated by CFTRinh-172. Interlobular ducts expressed mRNAs encoding CFTR, Slc26a6, and Slc26a3, as detected by RT-PCR. Thus Cl−-dependent apical HCO3− secretion in pancreatic duct is mediated predominantly by an Slc26a6-like Cl−/HCO3− exchanger and is accelerated by inhibition of CFTR. This study demonstrates functional coupling between Cftr and Slc26a6-like Cl−/HCO3− exchange activity in apical membrane of guinea pig pancreatic interlobular duct.

Keywords: bicarbonate, Slc26, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator, forskolin, H2DIDS

the pancreatic ducts of human and guinea pig secrete a HCO3−-rich fluid in response to stimulation by the adenylyl cyclase-coupled hormone secretin. The Cl−-rich secretion of pancreatic acinar cells is modified as it flows along the pancreatic ductal system, ultimately producing pancreatic juice with final concentrations of ∼140 mM HCO3− and ∼20 mM Cl− (31). In the guinea pig pancreatic duct, the uptake of bicarbonate across the basolateral membrane is mediated by Na+-HCO3− cotransport (NBC1) and by Na+/H+ exchange (19). HCO3− efflux across the apical membrane has been proposed to be mediated by CFTR, in concert with apical Cl−/HCO3− exchanger activity (9).

Proximal pancreatic duct HCO3− secretion by apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange is favored by the high luminal Cl− concentrations resulting from pancreatic acinar Cl− secretion. However, since this proximal fluid flows distally toward the ampullary terminus of the duct, its Cl− concentration progressively decreases in parallel with a gradual increase in its HCO3− concentration. These inverse changes in Cl− and HCO3− concentrations are predicted to alter relative contributions of apical membrane Cl−/HCO3− exchange and CFTR-mediated HCO3− conductance and have been suggested to reflect axial variation in expression and regulation of these transport activities (18). The Cl−/HCO3− exchangers Slc26a3 and Slc26a6 have been detected in mouse pancreatic duct and in the human pancreatic cell line CFPAC-1 (10, 22), leading to the proposal that Cl−-dependent HCO3− secretion by pancreatic proximal ducts represents combined activities of Slc26a6 and Slc26a3 anion exchangers, positively regulated by activated CFTR, with reciprocal positive regulation of CFTR by the anion exchangers (4, 5, 22, 23). However, a study in native mouse pancreatic duct suggests negative regulation of CFTR by Slc26a6 (43).

Secretin-stimulated HCO3− secretion in guinea pig pancreatic duct is not dependent on elevated luminal [Cl−] (21) (brackets denote concentration) and occurs even in the presence of luminal fluid containing 125 mM HCO3− and 23 mM Cl− (17). As luminal [Cl−] falls to or below this level (with corresponding elevation of [HCO3−]), CFTR Cl− permeability may fall while that for HCO3− may rise (34). Measurements of membrane potential (Vm) and intracellular pH (pHi) in luminally perfused interlobular ducts from guinea pig pancreas suggest that CFTR HCO3− conductance can account for observed levels of stimulated bicarbonate secretion (15, 18, 20). A computational model of pancreatic duct HCO3− secretion predicted for similar conditions that ∼94% of HCO3− efflux across the apical membrane was mediated by HCO3− conductance (36), although the model did not consider contributions from electrogenic Cl−/HCO3− exchange. Thus the HCO3− conductance of CFTR could provide the main route for apical HCO3− secretion in distal pancreatic ducts from species in which, like human and guinea pig, pancreatic juice contains high concentrations of HCO3− (∼140 mM).

Studies of the role of SLC26-mediated Cl−/HCO3− exchange activity in pancreatic ductal HCO3− secretion have to date been limited to genetically tractable mouse models. In isolated, perfused mouse interlobular pancreatic duct depleted of intracellular Cl−, genetic absence of Slc26a6 was associated with 45% reduction in secretin-stimulated luminal Clo−/HCO3i− exchange as measured during luminal Cl− restoration (13). However, in resealed mouse pancreatic duct segments, genetic absence of Slc26a6 was associated with 70% elevation of basal Cl−/HCO3− exchange activity (43). In addition, it was suggested that CFTR activity could be inhibited by Slc26a6 in the unstimulated mouse pancreatic duct (43). However, the low HCO3− concentration of mouse pancreatic juice (∼40 mM) contrasts to the ∼140 mM HCO3− in pancreatic juice of human and guinea pig (1), suggesting species-specific mechanisms of apical HCO3− transport and/or regulation. Thus identification of apical Cl−/HCO3− exchangers in guinea pig pancreatic duct and assessment of their interactions with CFTR may enhance our understanding of normal human pancreatic HCO3− secretion and its alterations in disease states.

We have measured pharmacologically defined activities of apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange and their response to CFTR inhibition in microperfused, forskolin-stimulated, interlobular ducts isolated from guinea pig pancreas. Because previous studies of apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange demonstrated that luminal H2DIDS decreased intracellular [Cl−] to a greater degree in cAMP-stimulated than in unstimulated ducts (15), we studied only forskolin-stimulated ducts. The effect of CFTR inhibition on Cl−-dependent HCO3− secretion into resealed interlobular duct fragments was also examined. We demonstrate a functional coupling between CFTR and Slc26a6-like apical anion exchange activity in isolated pancreatic interlobular duct under physiological conditions, such that CFTR inhibition increases apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation and culture of interlobular ducts.

Interlobular ducts (diameter 100–150 μm, length 800–1,200 μm) were isolated as described previously (19), in accordance with a protocol approved by the Nagoya University Committee on Ethical Animal Use for Experiments (21). Female Hartley guinea pigs (300–350 g) were killed by cervical dislocation. The pancreas was then removed, sliced into fragments of ∼1 mm3, and digested with collagenase and hyaluronidase at 37°C for 25 min, with an additional 20 min in fresh solution. Interlobular duct segments were microdissected with sharpened needles under a dissecting microscope, typically yielding 15–20 duct segments per pancreas. These duct segments are believed to represent second degree branches off the main pancreatic duct. The ducts were cultured overnight at 37°C as described previously (19).

Solutions.

Standard HEPES buffer contained (in mM) 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 d-glucose, and 10 HEPES. Standard HCO3−-buffered solutions contained (in mM) 115 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 5 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, and 10 d-glucose, equilibrated with 95% O2-5% CO2. Cl−-free solutions were made by replacing Cl− with glucuronate. In experiments shown in Fig. 7, bath and lumen were initially perfused with solution containing (in mM) 15 NaCl, 25 mM NaHCO3−, 95 N-methyl-d-glucamine (NMDG) Cl, 5 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, and 10 d-glucose, equilibrated with 95% O2-5% CO2. In these experiments (Fig. 7), Cl−-free solutions were made by replacing Cl− with glucuronate, and high-K+ (100 mM) solutions were made by replacing NMDG+ with K+, keeping [Na+] constant at 40 mM. Acetate addition was in equimolar substitution for Cl− or for glucuronate, as indicated. Forskolin (1 μM; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was added to the bath solution in all experiments. Where indicated, measurements of acid-equivalent influx were made in the presence of 200 μM of the anion exchange inhibitor dihydro-4,4′-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (H2DIDS; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) and/or 10 μM of the CFTR inhibitor inh-172 (CFTRinh-172; Sigma) (27). All solutions were adjusted to pH 7.4 at 37°C.

Microperfusion of isolated interlobular ducts.

The interlobular duct lumen was microperfused by use of a concentric pipette attached to one end of the duct, as described previously (14). Perfusate emerging from the open end of the duct lumen was washed away by superfused bath solution flowing at 3 ml/min and was maintained at 37°C.

Measurement of intracellular pH.

Intracellular pH (pHi) was measured ratiometrically in interlobular duct cells by use of the pH-sensitive fluorophore 2′,7′-bis(2-carboxyethyl)-5-(6)-carboxyfluorescein, acetoxymethyl ester (BCECF-AM; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Isolated interlobular ducts were incubated in 2 μM BCECF-AM at room temperature for 10 min. Small regions of BCECF-loaded duct epithelium were excited alternately at 440 and 490 nm, and fluorescence emission was measured at 530 nm (F440 and F490) by use of an inverted microscope (Olympus, Japan) adapted for epifluorescence. The BCECF excitation-to-emission ratio (F490/F440) was calculated and converted to a pHi value with calibration data obtained by the high K+-nigericin technique (40).

Calculation of H+-equivalent influx.

Net H+-equivalent influx (J ) via apical anion exchangers was estimated from the decrease in pHi following either an acetate prepulse or readdition of luminal Cl−. Net acid influx was calculated using the equation

) via apical anion exchangers was estimated from the decrease in pHi following either an acetate prepulse or readdition of luminal Cl−. Net acid influx was calculated using the equation

|

where βtot is the total buffering capacity [= intrinsic buffering capacity of the guinea pig pancreatic duct cell (βint) (11, 38) + buffering capacity of the CO2/HCO3− system (β )] and is a function of pHi. In Fig. 2 apical anion exchange activity was measured in the presence and absence of CO2/HCO3−. In the absence of CO2/HCO3−, βtot = βint. In each individual duct, dpHi/dt during sequential experimental maneuvers in the continued presence of CO2/HCO3− was measured at a uniform pHi. In most cases this pHi value was the midpoint of the pH change (ΔpH) elicited by the maneuver under study and is referred to as the “midpoint pHi value.”

)] and is a function of pHi. In Fig. 2 apical anion exchange activity was measured in the presence and absence of CO2/HCO3−. In the absence of CO2/HCO3−, βtot = βint. In each individual duct, dpHi/dt during sequential experimental maneuvers in the continued presence of CO2/HCO3− was measured at a uniform pHi. In most cases this pHi value was the midpoint of the pH change (ΔpH) elicited by the maneuver under study and is referred to as the “midpoint pHi value.”

Measurement of luminal pH and fluid secretory rate in isolated pancreatic ducts.

The pH of the duct lumen (pHL) was estimated by microfluorimetry as described previously (17, 21). The lumen of sealed ducts was punctured with a double-barreled (theta-glass) micropipette. Luminal fluid content was withdrawn and replaced with HCO3−-free, HEPES-buffered injection solution containing 20 μM BCECF-dextran (70 kDa).

The rate of fluid secretion into the lumen of resealed ducts was measured as previously described (17). Luminal fluorescence images were acquired at 1-min intervals via a charge-coupled device camera and transformed to binary images by using ARGUS 50 software (Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan). To determine secretory rate, initial values for the length (L0), diameter (2R0), and projected area (A0) of the duct lumen were measured in the first image of the series. The initial volume of the duct lumen (V0) was calculated, assuming cylindrical geometry, as πR02L0. The luminal surface area of the epithelium was taken to be 2πR0L0. Relative volume (V/V0) was calculated from relative area (A/A0) from the relationship V/V0 = (A/A0)3/2. Fluid secretion rates were calculated at 1-min intervals from increments in duct volume and expressed as secretory rates per unit area of luminal epithelium (nl·min−1·mm−2). The values of L0 and R0 were 459 ± 23 and 69 ± 3 μm, respectively (n = 14, means ± SE).

HCO3− concentration in the lumen ([HCO3−]L) was estimated from pHL with assumed values for CO2 solubility of 0.03 mM/mmHg and pK of the HCO3−/CO2-buffer system of 6.1 (17). The rate of HCO3− secretion into resealed duct lumens was calculated from the fluid secretory rate and changes in [HCO3−]L.

Measurement of Vm.

Vm was measured by impaling the basolateral membrane of the ducts with glass microelectrodes as previously described (20).

RT-PCR of apical anion exchangers and anion channel.

Total cellular RNA was prepared (RNeasy Protect Mini Kit, Qiagen, Tokyo, Japan) from homogenates of guinea pig isolated pancreatic interlobular ducts and examined for expression of mRNAs encoding the Slc26a3, Slc26a6, and Cftr polypeptides. cDNA was reverse transcribed from total cellular RNA (TaqMan, Roche, Basel, Switzerland) per manufacturer's instructions. Oligonucleotide primers for amplification of guinea pig cDNAs encoding Slc26a3 and Slc26a6 were designed on the basis of the aligned cDNA sequences of the human and mouse orthologs. A guinea pig Slc26a3 cDNA fragment was amplified with sense primer 5′-TCAACATTGTGGTTCCCAAA and antisense primer 5′-ATGCAAAACAGCATCATGGA. A fragment of guinea pig Slc26a6 cDNA was amplified with sense primer 5′-TCTCTGTGGGAACCTTTGCT and antisense primer 5′-GGCTCCGACAGGTAGTTGAC. Slc26a3 and Slc26a6 cDNAs were amplified for 35 cycles with conditions of 30 s denaturation at 94°C, 30 s annealing at 60°C, and 30 s extension at 72°C. Guinea pig Cftr cDNA was amplified for 35 cycles with sense primer 5′-CTTCTTGGTAGCCCTGTC and antisense primer 5′-CTAGGTATCCAAAAGGAGAG with conditions of 30 s denaturation at 94°C, 30 s annealing at 55°C, and 30 s extension at 72°C. cDNAs prepared from colon and kidney of guinea pig served as positive control templates. GAPDH cDNA was amplified to verify integrity of cDNA. PCR products were subjected to electrophoresis on 2% agarose gel and validated by direct DNA sequencing.

Statistics.

Data are presented as means ± SE where n refers to the number of individual ducts. Tests for statistical significance were made with Student's paired or unpaired t-test, and level of significance was taken as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange in microperfused interlobular pancreatic ducts.

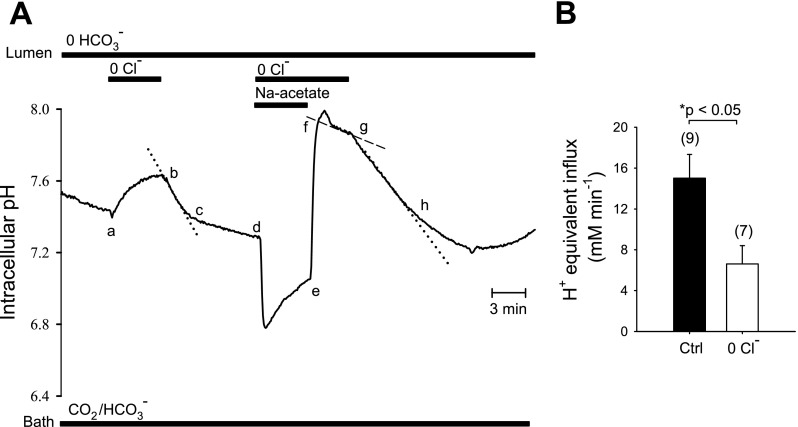

Figure 1 illustrates two experimental protocols for measurement of cAMP-activated apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange. To maximize the HCO3− and Cl− gradients across the apical membrane, an isolated interlobular duct was superfused with bath solution containing 124 mM Cl− and 25 mM HCO3−-5% CO2, and the duct lumen was perfused with nominally HCO3−-free, HEPES-buffered solution containing 124 mM Cl−. Under these conditions resting pHi was 7.32 ± 0.03 (n = 22). In the presence of 1 μM forskolin, removal of Cl− from the luminal solution by replacement with glucuronate (Fig. 1A, a–b) increased pHi by 0.074 ± 0.04 pH units (n = 13) over a 4-min period, followed by complete pHi recovery upon readdition of luminal Cl− (Fig. 1A, b–c). Addition of 80 mM sodium acetate to the luminal perfusate led to initial acidification (Fig. 1A, d–e), followed by a large intracellular alkalinization (Fig. 1A, e–f) upon subsequent acetate removal (mean peak value of pHi following acetate removal was pH 7.82 ± 0.07, n = 10). pHi recovery was slower (P < 0.02) in the absence of luminal Cl− (Fig. 1A, f–g; glucuronate replacement; J = 6.6 ± 1.7 mM/min, n = 7) than in its presence (Fig. 1B, J

= 6.6 ± 1.7 mM/min, n = 7) than in its presence (Fig. 1B, J = 15.0 ± 2.3 mM/min, n = 9). Subsequent readdition of luminal Cl− (Fig. 1A, g–h) prompted intracellular acidification at rates identical to those observed during initial recovery conditions (Fig. 1A, b–c). These two protocols show pHi recovery from alkaline load independent of the method of base loading. The data are consistent with the presence of apical Cl−/HCO3− or Cl−/OH− exchange (or the formally equivalent H+-Cl− cotransport).

= 15.0 ± 2.3 mM/min, n = 9). Subsequent readdition of luminal Cl− (Fig. 1A, g–h) prompted intracellular acidification at rates identical to those observed during initial recovery conditions (Fig. 1A, b–c). These two protocols show pHi recovery from alkaline load independent of the method of base loading. The data are consistent with the presence of apical Cl−/HCO3− or Cl−/OH− exchange (or the formally equivalent H+-Cl− cotransport).

Fig. 1.

Cl−/HCO3− and Cl−/OH− exchange activities across apical membrane of microperfused, forskolin-stimulated, interlobular pancreatic ducts. A: experimental protocol illustrating 2 sequentially applied methods of base loading in a representative microperfused pancreatic duct segment previously loaded with BCECF-AM: 1) luminal Cl−o removal, and 2) luminal acetate prepulse. The bath contained 124 mM Cl−, 25 mM HCO3−-5% CO2 with 1 μM forskolin throughout the experiment. The initial luminal solution of nominally HCO3−-free, HEPES-buffered solution was followed with 4 min exposure to 0 mM Cl− (glucuronate replacement, period a–b), accompanied by intracellular alkalinization. Restoration of luminal Cl−o permitted intracellular pH (pHi) recovery to control levels (b–c). A 4-min luminal exposure to 80 mM sodium acetate (d–e) followed by its removal (e–f) produced the sequential intracellular acidification and alkalinization characteristic of the acetate prepulse protocol. Slow pHi recovery from this intracellular alkalinization in the absence of luminal Cl−o (f–g) was accelerated upon readdition of luminal Cl−o (g–h). B: initial rates of pHi recovery (H+-equivalent acid influx, J ) following a sodium acetate prepulse were calculated from experiments similar to that shown in A, in the presence (solid bar, n = 9 pancreatic duct segments, g–h in A) and absence of luminal extracellular Cl− (Cl−o) (open bar, n = 7, f–g in A). Values are means ± SE; *P < 0.02, Student's unpaired t-test.

) following a sodium acetate prepulse were calculated from experiments similar to that shown in A, in the presence (solid bar, n = 9 pancreatic duct segments, g–h in A) and absence of luminal extracellular Cl− (Cl−o) (open bar, n = 7, f–g in A). Values are means ± SE; *P < 0.02, Student's unpaired t-test.

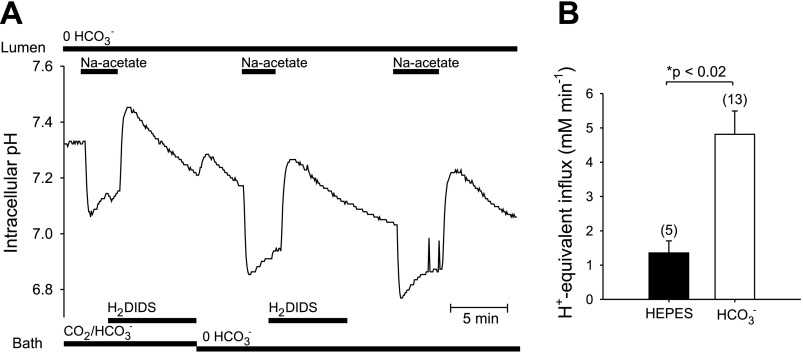

Figure 2A compares pHi recovery from an acetate-induced alkalosis in CO2/HCO3− buffer compared with that in nominally HCO3−-free, HEPES-buffered solution in ducts stimulated with forskolin. Basolateral H2DIDS was applied to minimize the contributions to pHi recovery of basolateral Cl−/HCO3− exchange or Na+-HCO3− cotransport [the guinea pig duct basolateral membrane lacks Na+-dependent Cl−/HCO3− exchange (19)]. The initial pHi recovery (base efflux) following acetate prepulse was considerably faster in CO2/HCO3− buffer than in its absence (Fig. 2B; *P < 0.02, Student's unpaired t-test).

Fig. 2.

HCO3− dependence of pHi recovery from a base load in microperfused ducts. A: a representative duct in bath containing 124 mM Cl−, 25 mM HCO3−-5% CO2 with 1 μM forskolin, and perfused luminally with nominally HCO3−-free, HEPES-buffered solution was base loaded by 80 mM luminal acetate prepulse, with subsequent recovery in the presence of basolateral 200 μM dihydro-4,4′-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (H2DIDS). After bath CO2/HCO3− removal, the duct segment was again subjected to luminal acetate prepulse with pHi recovery, first in the presence and immediately thereafter in the absence of basolateral H2DIDS. B: mean ± SE rates of H+-equivalent acid loading in experimental protocols similar to that of A were lower in nominally HCO3−-free, HEPES-buffered solution (solid bar, n = 5, mean midpoint pHi 7.46) than in HCO3−-buffered solution (open bar, n = 13, mean midpoint pHi 7.58; *P < 0.02, Student's unpaired t-test).

These data, together with those of Fig. 1, document the presence of apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange activity in isolated guinea pig interlobular ducts, expanding on others' observations (41).

Effect of luminal inhibitors on pHi recovery from an intracellular alkaline load in microperfused interlobular pancreatic ducts.

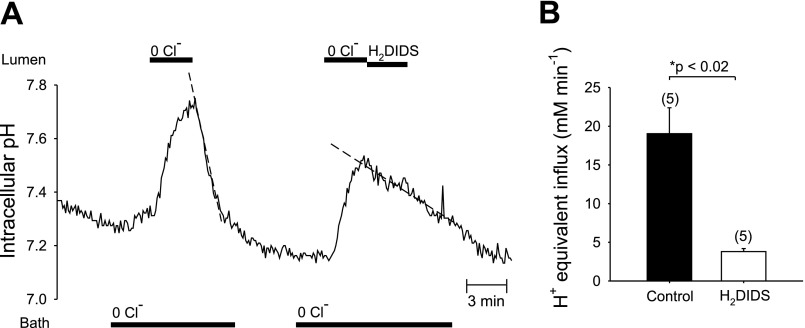

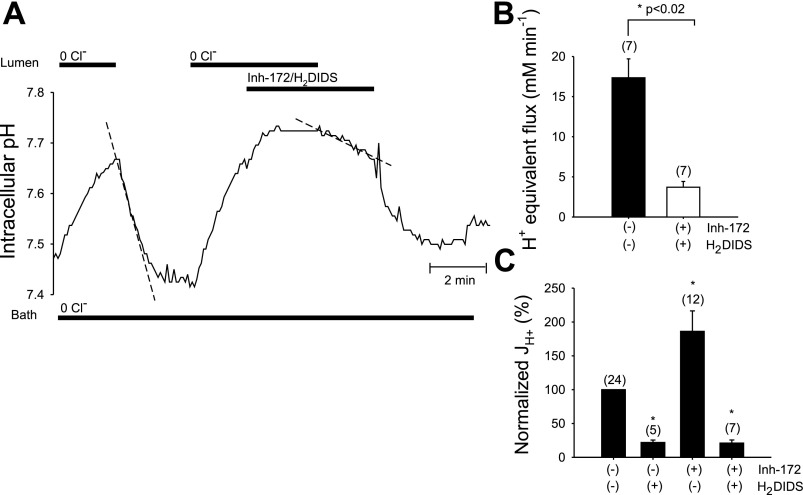

Recent evidence from Slc26a6−/− knockout mice suggests Slc26a6 and Slc26a3 polypeptides as candidate apical Cl−/HCO3− exchangers in microperfused mouse pancreatic interlobular ducts (13, 43). These two Slc26 anion exchangers differ in their sensitivities to inhibition by stilbene disulfonates (3, 4, 28). We therefore assessed sensitivity of apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange activity to H2DIDS. Figure 3A shows that in the presence of 25 mM HCO3− in bath and lumen, bath Cl− removal from forskolin-stimulated ducts increased pHi 0.18 ± 0.02 pH units (n = 15) in 2–3 min because of reversal of basolateral Cl−/HCO3− exchange. The rate of base loading (J ) following bath Cl− removal was 18.8 ± 3.4 mM/min (n = 12). pH recovery from alkalinization (J

) following bath Cl− removal was 18.8 ± 3.4 mM/min (n = 12). pH recovery from alkalinization (J ) following readdition of bath Cl− was 19.9 ± 4.7 mM/min (n = 12). In contrast, luminal Cl− removal caused a larger pHi increase of 0.25 ± 0.02 pH units (n = 22) in 2–3 min, due to reversal of apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange activity. The rate of base loading (J

) following readdition of bath Cl− was 19.9 ± 4.7 mM/min (n = 12). In contrast, luminal Cl− removal caused a larger pHi increase of 0.25 ± 0.02 pH units (n = 22) in 2–3 min, due to reversal of apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange activity. The rate of base loading (J ) following luminal Cl− removal was 24.2 ± 2.4 mM/min (n = 22). Subsequent readdition of luminal Cl− prompted influx of acid equivalents (J

) following luminal Cl− removal was 24.2 ± 2.4 mM/min (n = 22). Subsequent readdition of luminal Cl− prompted influx of acid equivalents (J ) at 21.5 ± 2.8 mM/min (n = 22; P > 0.05, Student's paired t-test for base loading rate vs. acid influx rate measured at the same pHi). As shown in Fig. 3A and summarized in Fig. 3B, luminal addition of H2DIDS (200 μM) coincident with luminal Cl− restoration slowed pHi recovery from a base load by ∼80% (n = 5, P < 0.02). These data showing H2DIDS-sensitive, apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange are consistent with the pharmacological properties of mouse and human Slc26a6.

) at 21.5 ± 2.8 mM/min (n = 22; P > 0.05, Student's paired t-test for base loading rate vs. acid influx rate measured at the same pHi). As shown in Fig. 3A and summarized in Fig. 3B, luminal addition of H2DIDS (200 μM) coincident with luminal Cl− restoration slowed pHi recovery from a base load by ∼80% (n = 5, P < 0.02). These data showing H2DIDS-sensitive, apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange are consistent with the pharmacological properties of mouse and human Slc26a6.

Fig. 3.

Luminal H2DIDS inhibits apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange in microperfused, forskolin-stimulated ducts. A: both lumen and bath were perfused with CO2/HCO3−-buffered solution throughout the experiment, with 1 μM forskolin in the bath. Bath Cl− removal revealed basolateral Cl−/HCO3− exchange activity, and subsequent removal of luminal Cl− revealed apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange activity. Restoration of first luminal and then bath Cl− led to full pHi recovery. Addition of 200 μM H2DIDS to the luminal perfusate inhibited pHi recovery mediated by apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange. B: rates of pHi recovery from base load in experiments similar to that of A (solid bars, n = 5, mean midpoint pHi 7.51) were inhibited in the presence of H2DIDS (open bars, n = 5, mean midpoint pHi 7.47); Values are means ± SE *P < 0.02, Student's paired t-test.

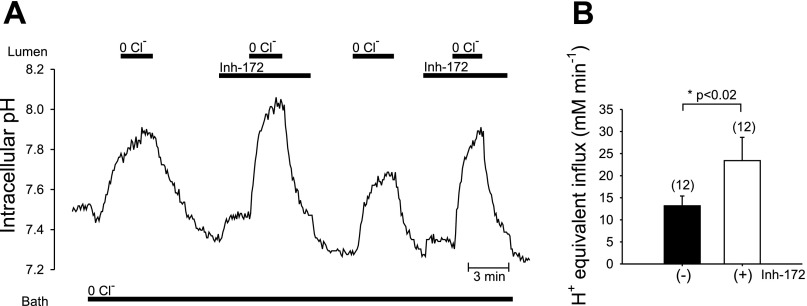

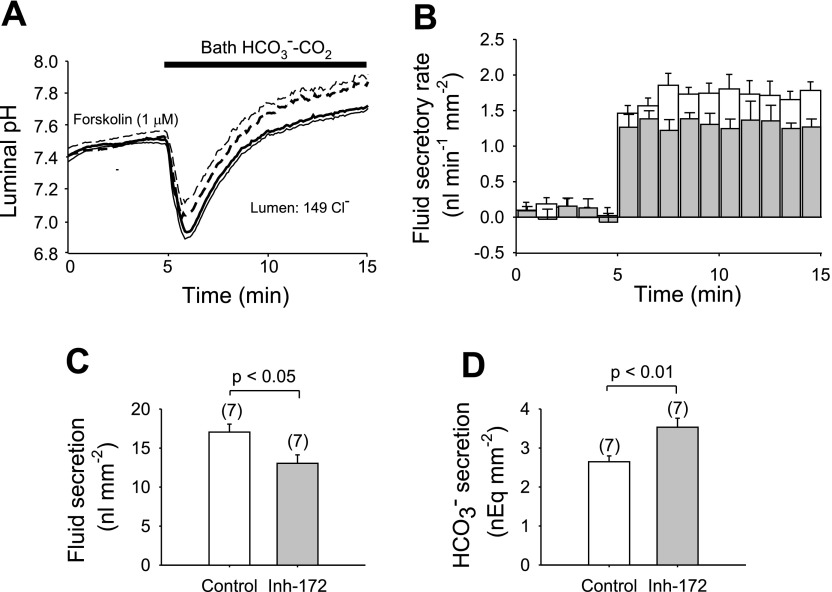

In the presence of high luminal [Cl−], apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange has been proposed to mediate most HCO3− secretion, with CFTR HCO3− conductance playing a minor role (1, 37). In this setting CFTR is thought to support luminal Cl−-dependent HCO3− secretion by recycling intracellular Cl− across the apical membrane (30, 45). Therefore, we examined the effect of CFTR inhibition on pHi recovery following a base load, using luminal application of CFTRinh-172, a specific CFTR inhibitor (27) that does not inhibit Cl−/HCO3− exchange in CFTR-transduced CFPAC-1 cells (33). Figure 4A shows a pHi trace from a representative duct luminally perfused with 25 mM HCO3− solution in a 25 mM HCO3− bath containing 1 μM forskolin. Removal of luminal Cl− rapidly alkalinized the duct. Subsequent luminal Cl− restoration induced pHi recovery from this base load significantly more rapidly (P < 0.02, paired experiments) in the presence of CFTRinh-172 (J = 23.4 ± 5.3, n = 12) than in the drug's subsequent absence (J

= 23.4 ± 5.3, n = 12) than in the drug's subsequent absence (J = 13.27 ± 2.2, n = 12; Fig. 4B). Thus inhibition of CFTR accelerated luminal Cl−-dependent HCO3− efflux across the apical membrane (Cl−/HCO3− exchange) by ∼80% in alkaline-loaded stimulated ducts.

= 13.27 ± 2.2, n = 12; Fig. 4B). Thus inhibition of CFTR accelerated luminal Cl−-dependent HCO3− efflux across the apical membrane (Cl−/HCO3− exchange) by ∼80% in alkaline-loaded stimulated ducts.

Fig. 4.

Luminal exposure to a CFTR inhibitor accelerates pHi recovery from a base load in microperfused, forskolin-stimulated ducts. A: bath and lumen were separately perfused with the standard CO2/HCO3− solution, with 1 μM bath forskolin present throughout the experiment. Duct cell pHi was measured during sequential periods of luminal Cl− removal and restoration with the bath continuously superfused with Cl−-free solutions, in the absence and subsequent presence of 10 μM CFTR inhibitor inh-172 (CFTRinh-172). B: 12 separate ducts similar to that in A reveal higher mean J acid equivalent influx upon luminal Cl− restoration in the presence of inh-172 (open bar) than in its absence (solid bar). For ducts exposed to 4 sequential cycles of Cl− removal and restoration as A, data from the first 2 cycles were included in the pooled data presented in B. Values are means ± SE from paired experiments, *P < 0.05, Student's paired t-test.

acid equivalent influx upon luminal Cl− restoration in the presence of inh-172 (open bar) than in its absence (solid bar). For ducts exposed to 4 sequential cycles of Cl− removal and restoration as A, data from the first 2 cycles were included in the pooled data presented in B. Values are means ± SE from paired experiments, *P < 0.05, Student's paired t-test.

We next examined the combined effects of luminal H2DIDS and CFTRinh-172 on luminal Cl−-dependent pHi recovery from alkaline load in the presence of 25 mM HCO3− in both bath and lumen. The pHi trace from a representative duct in Fig. 5A and the summarized paired duct data in Fig. 5B show that luminal H2DIDS inhibited the CFTRinh-172-accelerated rate of pHi recovery from alkaline load (J = 3.7 ± 0.7 mM/min, n = 7; P < 0.02, Student's paired t-test) compared with that in the absence of H2DIDS and inh-172 (J

= 3.7 ± 0.7 mM/min, n = 7; P < 0.02, Student's paired t-test) compared with that in the absence of H2DIDS and inh-172 (J = 17.4 ± 2.3 mM/min, n = 7). As summarized in Fig. 5C, which shows normalized pHi recovery data following luminal Cl− restoration taken from Figs. 3A, 4A, and 5A, CFTRinh-172 enhanced H2DIDS-sensitive apical membrane Cl−/HCO3− exchange. These data suggest that CFTR and Slc26a6-like, H2DIDS-sensitive Cl−/HCO3− exchange are functionally coupled in the duct apical membrane.

= 17.4 ± 2.3 mM/min, n = 7). As summarized in Fig. 5C, which shows normalized pHi recovery data following luminal Cl− restoration taken from Figs. 3A, 4A, and 5A, CFTRinh-172 enhanced H2DIDS-sensitive apical membrane Cl−/HCO3− exchange. These data suggest that CFTR and Slc26a6-like, H2DIDS-sensitive Cl−/HCO3− exchange are functionally coupled in the duct apical membrane.

Fig. 5.

Luminal H2DIDS completely inhibits the component of apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange activity accelerated by luminal CFTRinh-172. A: CO2/HCO3− bath containing 1 μM forskolin was Cl−-free throughout the experiment. pHi was recorded during sequential Cl− removal from and restoration to the CO2/HCO3−-buffered luminal perfusate in the absence and subsequent combined presence of 10 μM CFTRinh-172 and 200 μM H2DIDS. B: control mean pHi recovery rate (solid bar) compared with CFTRinh-172 plus H2DIDS (open bar, mean midpoint pHi 7.68 in both absence and presence of drugs); *n = 7, P < 0.02, Student's paired t-test. C: normalized rate of pHi recovery (expressed as J ) following luminal Cl− restoration in the absence and presence of the indicated luminal inhibitors. Data are taken from Figs. 3B, 4B, and 5B. Rates of pHi recovery from alkaline load (J

) following luminal Cl− restoration in the absence and presence of the indicated luminal inhibitors. Data are taken from Figs. 3B, 4B, and 5B. Rates of pHi recovery from alkaline load (J ) in the presence of inhibitor were normalized for each duct to the paired, previously measured control rate of pHi recovery for that same duct (100% = 15.6 ± 1.5 mM/min, n = 24). Values are means ± SE from paired experiments; *P < 0.02, Student's paired t-test.

) in the presence of inhibitor were normalized for each duct to the paired, previously measured control rate of pHi recovery for that same duct (100% = 15.6 ± 1.5 mM/min, n = 24). Values are means ± SE from paired experiments; *P < 0.02, Student's paired t-test.

Effects of luminal CFTRinh-172 on Cl−-dependent HCO3− secretion in cAMP-stimulated interlobular pancreatic ducts.

To investigate functional coupling between CFTR and Cl−/HCO3− exchange under more physiological conditions, we examined the effects of luminally injected CFTRinh-172 on Cl−-dependent HCO3− secretion in sealed ducts. Changes in pHL and volume were simultaneously monitored and rates of fluid and HCO3− secretion were calculated. The lumens of sealed ducts were micropunctured and filled with HCO3−-free, HEPES-buffered 149 mM Cl− containing BCECF-dextran (20 μM). The sealed ducts were initially superfused with the same HCO3−-free, HEPES-buffered solution and maximally stimulated by 1 μM bath forskolin. The bath solution was then switched to HCO3−-CO2-buffered solution in the continued presence of forskolin. pHL transiently decreased due to CO2 diffusion into the lumen and then subsequently increased due to HCO3− secretion (17), reaching pHi values of 7.72 ± 0.02 in the absence and 7.86 ± 0.04 in the presence of 10 μM luminal CFTRinh-172 after 10 min (Fig. 6A; n = 7, P < 0.01).

Fig. 6.

Effects of luminal CFTRinh-172 on Cl−-dependent HCO3− secretion in cAMP-stimulated pancreatic duct. Duct lumens were filled with a Cl−-rich (149 mM), HCO3−-free, HEPES-buffered solution containing BCECF dextran. The bath was first superfused with HCO3−-free, HEPES-buffered solution containing 1 μM forskolin. After a 5-min period, CO2-HCO3− was introduced to the bath solution in the continued presence of forskolin. Luminal pH (pHL) and fluid secretory rate were monitored for 10 min. A: changes in pHL in the absence (solid line) or presence (dashed line) of luminally injected CFTRinh-172 (10 μM): means ± SE of 7 experiments. Thin solid line and thin dashed line indicate SE in 1 direction only, for clarity. B: changes in fluid secretory rate in the absence (open bars) or presence (shaded bars) of luminally injected CFTRinh-172 (10 μM). Means ± SE of 7 experiments. C: fluid secretion calculated in the absence (open bar) and presence (shaded bar) of CFTRinh-172 during 10-min superfusion with HCO3−-CO2 buffered solution (*P < 0.05, Student's unpaired t-test). D: HCO3− secretion across the apical membrane during 10-min superfusion with HCO3−-CO2-buffered solution in the absence (open bar) and presence (shaded bar) of CFTRinh-172 (*P < 0.01, Student's unpaired t-test). Means ± SE for 7 experiments in C and D.

Fluid secretion rapidly increased to stable values (Fig. 6B), with rates of 1.7 ± 0.1 nl·min−1·mm−2 in the absence and 1.3 ± 0.1 nl·min−1·mm−2 in the presence of CFTRinh-172 (Fig. 6C, n = 7, P < 0.05). Calculated HCO3− secretion rates during the 10-min perfusion with HCO3−-CO2 buffer were 2.65 ± 0.15 nEq/mm in the absence and 3.53 ± 0.23 nEq/mm in the presence of CFTRinh-172 (Fig. 6D, n = 7, P < 0.01). Thus luminal CFTRinh-172 significantly enhanced HCO3− secretion while inhibiting net fluid secretion in the presence of high luminal [Cl−]. The decreased fluid secretion likely reflected inhibition of CFTR-mediated Cl− secretion. Previous studies suggest that HCO3− secretion is mediated largely by H2DIDS-sensitive Cl−/HCO3− exchange in the presence of high luminal [Cl−] (17, 21). The present data suggest that inhibition of CFTR activity enhances H2DIDS-sensitive apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange under physiological conditions in which Cl−-dependent HCO3− secretion is thought to occur in vivo.

Effect of Vm on apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange in microperfused interlobular pancreatic ducts.

Strong evidence favors an electrogenic mechanism of 1Cl−/2HCO3− exchange for recombinant mouse Slc26a6 (35), but DIDS-sensitive electroneutral monovalent anion exchange by recombinant mouse Slc26a6 and human SLC26A6 has also been observed (3, 6). Consistent with the latter mechanism, DIDS-sensitive SLC26A6-like Cl−/HCO3− exchange in CFTR-transduced human CFPAC-1 pancreatic duct epithelial cells (10, 33) and in mouse NIH 3T3 fibroblasts and human HEK-293 cells (26) was insensitive to bath [K+]-induced changes in Vm. In addition, net secretion of HCO3− was equivalent to net reabsorption of Cl− in resealed mouse pancreatic duct segments stimulated with forskolin, and this HCO3− secretion was completely absent in duct segments from the Slc26a6−/− mouse (45).

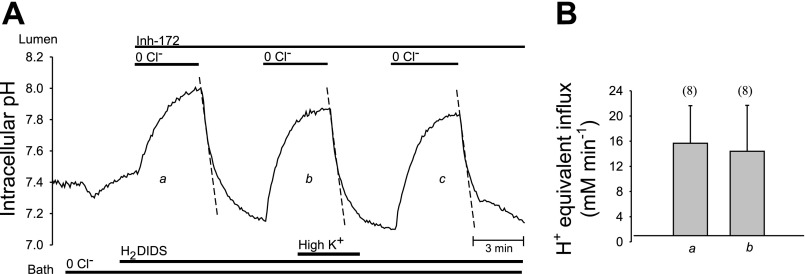

To test Vm dependence of apical membrane Cl−/HCO3− exchange, ducts were subjected to luminal Cl− removal and restoration in the presence of luminal CFTRinh-172, in Cl−-free bath solutions of normal and high [K+] containing 40 mM Na+ along with 500 μM H2DIDS to minimize basolateral membrane HCO3− transport. As shown by the pHi trace of Fig. 7A, and summarized in Fig. 7B (paired experiments), apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange rate (acid influx) in the presence of luminal CFTR inhibitor was on average not altered by bath [K+] changes between 5 and 100 mM. The rates of pHi recovery from an alkaline load in the presence of CFTRinh-172 in normal K+ bath (Fig. 7B, “control” conditions) were indistinguishable from those reported in Fig. 4B, reinforcing the conclusion that inhibition of CFTR activity leads to increased apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange.

Fig. 7.

Depolarization by bath [K+] elevation does not alter pHi recovery from base load in microperfused ducts. A: CO2/HCO3− bath containing 1 μM forskolin and 500 μM H2DIDS was Cl−-free and the lumen contained 10 μM CFTRinh-172 throughout the experiment. pHi was recorded during sequential Cl− removal from and restoration to the CO2/HCO3−-buffered luminal perfusate with 5 or 100 mM bath K+. B: luminal Cl− restoration-induced mean pHi recovery rate (section a, mean midpoint pHi 7.55) was not inhibited by the depolarizing maneuver of bath K+ elevation (section b, mean midpoint pHi 7.60); means ± SE from paired experiments,*P > 0.05, Student's paired t-test.

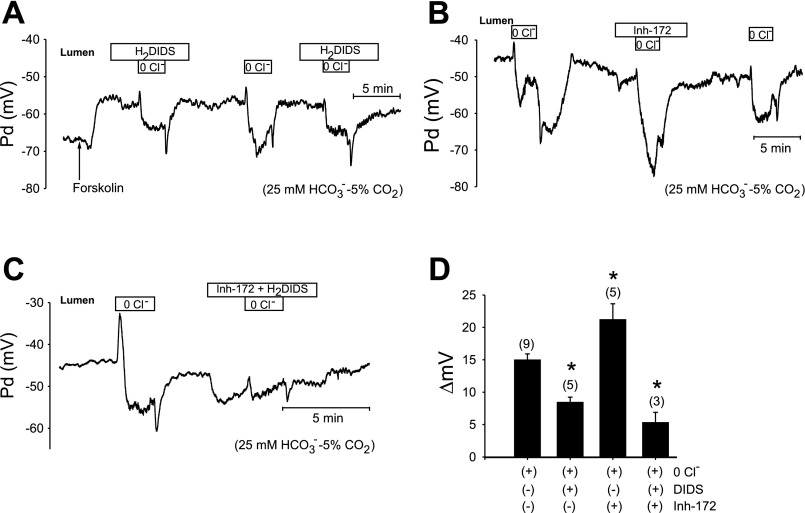

Figure 8 tracks duct Vm during luminal Cl− removal and restoration in the presence and absence of luminal H2DIDS (200 μM) or CFTRinh-172 (10 μM). Bath and luminal solutions both contained 25 mM HCO3−-5% CO2. The basolateral membrane was impaled by microelectrodes and intracellular potential was measured in reference to the bath. We assume that basolateral Vm was likely close in magnitude to apical Vm, since the distal end of the lumen was open to the bath, and since the transepithelial potential of the stimulated, perfused rat pancreatic duct was < 5 mV (30). Luminal exposure to either H2DIDS (Fig. 8A) or CFTRinh-172 (Fig. 8B) resulted in a small hyperpolarization (−4.1 ± 0.9 mV, n = 5; −4.0 ± 0.3 mV, n = 5, respectively). As shown in Fig. 8, A, B, and C, removal of luminal Cl− resulted in a transient depolarization, followed by a hyperpolarization of the duct by −15.0 ± 1.0 mV (n = 12). Restoration of Cl− to the luminal perfusate reversed these changes. The transient depolarization was partially inhibited by luminal CFTRinh-172 (Fig. 8B) and thus probably reflected Cl− efflux via CFTR. The subsequent hyperpolarization might be explained by depletion of intracellular Cl− (with Vm shift toward the K+ equilibrium potential) and/or by 1Cl−/2HCO3− exchange across the apical membrane. Figure 8A shows that the hyperpolarization was attenuated ∼44% by luminal H2DIDS (to −8.4 ± 0.8 mV, n = 5; P < 0.01, Fig. 8D), suggesting that H2DIDS-sensitive apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange contributes to the hyperpolarization. In contrast, CFTR inhibition by luminal application of CFTRinh-172 enhanced the hyperpolarization by ∼45% to −21.8 ± 2.5 mV (n = 5; P < 0.05 Figs. 8, B and D) and this enhancement was also inhibited by luminal H2DIDS (Fig. 8, C and D). These data reveal an H2DIDS-sensitive hyperpolarizing activity in response to luminal Cl− removal that is consistent with electrogenic Cl−/HCO3− exchange across the apical membrane. The data also confirm that inhibition of CFTR accelerates apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange.

Fig. 8.

Membrane hyperpolarization by luminal Cl− removal in microperfused ducts is reduced by H2DIDS and increased by CFTRinh-172. A: membrane potential difference (Pd) was measured during sequential cycles of luminal Cl− removal and restoration in the initial presence and subsequent absence and reintroduction of luminal H2DIDS (200 μM). B: Pd was measured during sequential cycles of luminal Cl− removal and restoration in the initial absence, subsequent presence, and repeated absence of CFTRinh-172 (10 μM). Both A and B are representative of 5 similar experiments, in which the Cl−-containing CO2/HCO3−-buffered bath was supplemented with 1 μM forskolin (arrow). C: Pd was measured during sequential cycles of luminal Cl− removal and restoration in the initial absence and subsequent presence of CFTRinh-172 (10 μM) + H2DIDS (200 μM). Representative of 3 similar experiments. D: mean change in hyperpolarization from resting membrane potential (ΔmV) following removal of luminal Cl− in presence or absence of luminally applied inhibitors, summarized from experiments similar to those shown in A, B, and C. Means ± SE; *P < 0.01, Student's paired t-test.

Expression of Slc26a3, Slc26a6, and CFTR mRNAs in guinea pig interlobular pancreatic duct.

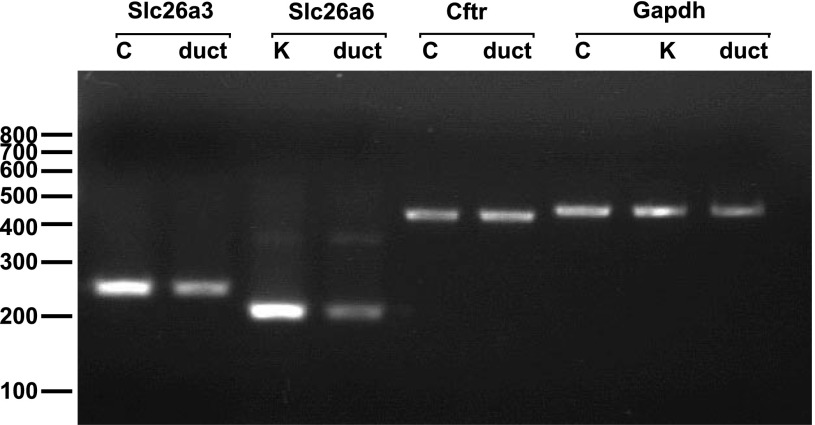

Figure 9 shows sequence-confirmed cDNAs encoding Slc26a3, Slc26a6, Cftr, and Gapdh, as amplified by RT-PCR from total RNAs of isolated interlobular pancreatic duct, kidney, and colon of guinea pig. The data confirm that interlobular ducts from guinea pig pancreas express mRNAs encoding not only Cftr, but also the apical membrane anion exchangers Slc26a3 and Slc26a6, as has been observed in mouse pancreas (13).

Fig. 9.

Expression of Slc26a3, Slc26a6, and Cftr mRNAs in interlobular pancreatic duct segments of guinea pig. Agarose gel showing RT-PCR products amplified 35 cycles from cDNA of interlobular pancreatic duct, colon (C), and kidney (K) of guinea pig.

DISCUSSION

We have identified in guinea pig interlobular pancreatic duct a H2DIDS-sensitive, Cl−/HCO3− exchange activity that mediates the major component of forskolin-stimulated, Cl−-dependent HCO3− efflux across the apical membrane and a smaller component of apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange activity insensitive to 200 μM H2DIDS. The H2DIDS-sensitive fraction of Cl−/HCO3− exchange was accelerated by inhibition of CFTR. In addition, we have shown that luminal inhibition of CFTR decreased fluid secretion but increased net apical HCO3− secretion into Cl−-rich luminal fluid. Guinea pig pancreatic duct expressed mRNAs encoding Slc26a3, Slc26a6, and Cftr. Luminal Cl− removal reversibly hyperpolarized duct cells in a manner partially attenuated by H2DIDS, consistent with electrogenic apical membrane 1Cl−/2HCO3− exchange. However, pHi recovery from an alkaline load upon restoration of luminal Cl− (apical Cli−/HCO3o− exchange activity) was on average insensitive to depolarization by bath exposure to 100 mM K+.

The data together suggest that CFTR and H2DIDS-sensitive Cl−/HCO3− exchange are functionally coupled in the apical membrane of pancreatic duct cells to mediate fluid and HCO3− secretion. On the basis of pharmacological properties of the recombinant mouse and human orthologs, the component of apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange sensitive to 200 μM H2-DIDS may be mediated by Slc26a6, whereas the insensitive component may be mediated by Slc26a3.

Identification of apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange activity in interlobular pancreatic duct of guinea pig.

Although HCO3− and Cl− transport by the microperfused pancreatic duct of guinea pig has been studied (15–17), direct study of regulated luminal Cl−/HCO3− exchange by pHi measurement has until recently not been reported. We have detected apical membrane Cl−/base exchange activity in forskolin-stimulated interlobular pancreatic duct. Cl−/HCO3− exchange was severalfold more rapid than Cl−/OH− exchange (Fig. 2) and largely inhibited by luminal 200 μM H2DIDS. H2DIDS-sensitive apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange in guinea pig pancreatic duct was recently shown to be stimulated by bile acids by a mechanism dependent on intracellular Ca2+ increase (41).

mRNAs encoding both apical exchangers Slc26a3 and Slc26a6 have been detected in the mouse pancreatic duct and in the human pancreatic cell line CFPAC-1 (10, 22, 32). Slc26a3 and Slc26a6 mRNAs are also expressed in intact guinea pig interlobular pancreatic ducts (Fig. 8). Among the functional differences noted to date between recombinant Slc26a3 and Slc26a6 are the contrasting DIDS insensitivity of Slc26a3 (4, 28) and the DIDS sensitivity of Slc26a6 (3, 10). Forskolin-stimulated, luminal Cl−-dependent HCO3− efflux following base load was inhibited ∼80% by 200 μM H2DIDS in guinea pig pancreatic ducts (Fig. 3). H2DIDS similarly inhibited duct cell HCO3− efflux under basal conditions and in response to stimulation by secretin (12). H2DIDS inhibited both basal and secretin-stimulated fluid secretion into Cl−-rich luminal fluid (17). The apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange activity sensitive to 200 μM H2-DIDS thus resembles Slc26a6 (3, 10), and anion exchange activity insensitive to 200 μM H2-DIDS recalls Slc26a3 (4, 28), with the former contributing the greater portion of Cl−-dependent HCO3− secretion across the apical ductal membrane.

Vm sensitivity of Slc26-like Cl−/HCO3− exchange in guinea pig pancreatic duct.

Electrogenic 1Cl−/nHCO3− exchange by Slc26a6 was first suggested by membrane hyperpolarization upon removal of bath Cl− in Xenopus oocytes expressing mouse Slc26a6 (22, 44). Electrogenic anion exchange with a stoichiometry of 1Cl−/2HCO3− was later confirmed by simultaneous measurement of pHi, intracellular Cl− ([Cl−]i), and Vm (35). However, other studies reported Vm-insensitive Cl−/HCO3− exchange mediated by mouse Slc26a6 and human SLC26A6 (3). Rates of endogenous apical H2DIDS-sensitive Cl−/HCO3− exchange in CFTR-complemented CFPAC-1 cells (33) and rates of CFTR-activated Cl−/HCO3− exchange in 3T3 and HEK-293 cells (26) were similarly insensitive to depolarization by elevated bath [K+]. Mouse Slc26a3 was shown to mediate 2Cl−/1HCO3− exchange (35), but Slc26a3-mediated anion exchange with properties of Vm sensitivity or electrogenicity was not observed by other laboratories (4, 24, 28). Moreover, Slc26a3-mediated Cl−/HCO3− exchange across the apical enterocyte membrane of intact mouse ileum does not exhibit properties of electrogenicity (42).

The Vm hyperpolarization induced by removal of Cl− from HCO3−-containing luminal perfusate (Fig. 8) may reflect depletion of intracellular Cl− (Vm thus approaching toward K+ equilibrium potential). Alternatively, it may reflect 1Cl−/2HCO3− exchange across the apical membrane, or a combination of the two. Partial inhibition of hyperpolarization by luminal H2DIDS suggests that H2DIDS-sensitive apical 1Cl−/2HCO3− exchange by Slc26a6 or a similar activity contributes substantially to the hyperpolarization. This conclusion was supported further by inhibition of net fluid secretion by. CFTRinh-172 of only 24%, demonstrating that net fluid efflux still accompanied apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange in this condition (Fig. 6). The effective HCO3− concentration of the fluid secreted in the presence of luminal CFTRinh-172 was estimated from the ratio of measured HCO3− secretion and measured fluid secretion to be 283 ± 36 mM. Assuming isotonic salt-water coupling during pancreatic fluid secretion, this value of effective HCO3− concentration suggests that ∼50% of HCO3− secretion is unaccompanied by net fluid flow and is formally mediated by 1:1 exchange with luminal Cl−. Thus an effective HCO3− concentration of ∼300 mM is compatible with HCO3− secretion mediated by 1Cl−/2HCO3− exchange.

In contrast, apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange rate (as measured during luminal Cl− removal and restoration) was not significantly affected by exposure to high (100 mM) [K+] in the bath (Fig. 7), a maneuver that depolarizes Vm by ∼20–30 mV in pancreatic duct of guinea pig (H. Ishiguro, unpublished data) and rat (29). pHi recovery from acetate-induced base load in perfused guinea pig interlobular duct was similarly insensitive to high bath K+ (n = 10, data not shown). Changes in pHi upon removal and restoration of luminal Cl− demonstrated equivalent rates of acid-equivalent transport in the absorptive and secretory directions for apical Cl−/HCO3− exchanger, further consistent with an electroneutral anion exchange process (data not shown).

However, a heterogeneous distribution among isolated duct fragments of electrogenic Cl−/HCO3− exchangers of 1:2 and 2:1 stoichiometries could also produce an averaged insensitivity to high K+ depolarization. Alternatively or additionally, the 20–30 mV depolarization elicited by elevated bath [K+] may be too small to influence measurably the observed Cl−/HCO3− exchange activity, in contrast to the 70–140 mV excursions applied to voltage-clamped Xenopus oocytes expressing mouse Slc26a3 and Slc26a6 (7, 35). Considered in this way, the 15 mV changes in duct potential difference elicited by luminal Cl− removal and restoration in the present studies (Fig. 8) might not be expected detectably to modify electrogenic anion exchange rates. Thus the electrogenicity of the apical H2DIDS sensitive Cl−/HCO3− activity of guinea pig interlobular pancreatic duct remains uncertain.

Interaction of apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange and Cftr in the apical membrane of guinea pig pancreatic duct.

Slc26a6-like Cl−/HCO3− exchange may play a major role in HCO3− secretion in proximal parts of the pancreatic ductal system characterized by Cl−-rich luminal fluid derived from acinar secretion (18). Activation of apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange is thought to depend on the presence of functional CFTR in pancreatic duct cells. Lee et al. (1999) examined the activities of apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange in luminally perfused main pancreatic duct from wild-type and CftrΔF508/ΔF508 mice (25). Forskolin stimulation increased the rate of DIDS-sensitive Cl−/HCO3− exchange across the apical membrane in ducts from wild-type mice, but not in ducts from CftrΔF508/ΔF508 mice. In CFPAC-1 human pancreatic duct epithelial cells lacking CFTR, heterologous CFTR complementation conferred forskolin-stimulated, H2DIDS-sensitive (SLC26A6-like) Cl−/HCO3− exchange (33) in the apical membrane (32). Coexpression of recombinant human wild-type but not mutant CFTR conferred or enhanced forskolin-sensitive Cl−/HCO3− exchange activity associated with expression of mouse Slc26a3 and Slc26a6 in HEK-293 cells (22) and with human SLC26A6 (3) and SLC26A3 (4) in Xenopus oocytes. These data suggest that activation of Slc26-mediated Cl−/HCO3− exchange in the apical membrane requires functional and activated CFTR and have been interpreted to reflect direct interaction between the STAS domains of SLC26 anion transporters and the phosphorylated R domain of CFTR (23).

CFTRinh-172 alters CFTR gating by voltage-independent binding to a cytoplasmic nucleotide binding domain (39) or, according to more recent evidence, by direct pore interaction (2). CFTRinh-172 inhibition of CFTR may alter direct or indirect interactions between CFTR and Slc26-like anion exchangers. However, the functional coupling observed in this study does not require such direct molecular interaction. CFTR and Slc26a6 experience similar concentration gradients for Cl− and HCO3− at the duct apical membrane and may act synergistically or antagonistically in HCO3− secretion. For example, Slc26a6-mediated HCO3− efflux upon luminal Cl− restoration may be reduced secondary to rapid Cl− gradient dissipation by Cl− influx through CFTR. In addition, CFTR and (electrogenic) Slc26a6 will experience the same inside-negative Vm driving force. Thus, in the presence of high luminal [Cl−], Slc26a6-mediated Cl−/HCO3− exchange may be a more energy-efficient form of HCO3− secretion than the HCO3− conductance of CFTR (8).

In the present study, we used Cl−-rich luminal solutions in microperfused and in sealed ducts to mimic luminal conditions of the proximal duct. (The technical requirements of duct isolation and perfusion required use of interlobular ducts from more distal locations along the duct axis.) We demonstrated with three types of experiments that inhibition of CFTR accelerated Slc26a6-like Cl−/HCO3− exchange across the duct apical membrane. First, luminal application of CFTRinh-172 increased forskolin-stimulated Cl−/HCO3− exchange by ∼80% as measured by rate of pHi change during luminal Cl− removal and restoration (Fig. 4). This CFTRinh-172-enhanced component of Cl−/HCO3− exchange was completely inhibited by 200 μM luminal H2DIDS (Fig. 5), consistent with Slc26a6-mediated Cl−/HCO3− exchange. Second, luminally injected CFTRinh-172 (10 μM) increased forskolin-stimulated HCO3− secretion into Cl−-rich luminal fluid (Fig. 6). Third, luminally applied CFTRinh-172 (10 μM) potentiated luminal Cl− removal-induced, 200 μM H2DIDS-sensitive hyperpolarization in the presence of HCO3− (Fig. 8).

Inhibition of forskolin-stimulated CFTR by inh-172 reduces the rapid but transient depolarization immediately following luminal Cl− removal (Fig. 8), an effect predicted to antagonize activity of an electrogenic apical 1Cl−/2HCO3− exchanger. However, inhibition of forskolin-stimulated CFTR by inh-172 is also predicted to elevate duct cell [Cl−]i or to reduce its rate of decline during the period of forskolin-stimulated secretion, effects predicted to stimulate apical 1Cl−/2HCO3− exchange as measured during luminal Cl− removal. Our data (Figs. 4–6) demonstrate predominance of the latter effect, showing stimulation of ductal apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange by CFTRinh-172. Thus inh-172-induced hyperpolarization in the presence of high luminal [Cl−] may increase HCO3− secretion (Fig. 6) by accelerating an apical electrogenic 1Cl−0/2HCO3−i exchange activity, despite the predicted coincident increase in [Cl−]i. The lack of Cl−/HCO3− exchange inhibition by bath [K+] elevation (Fig. 7) and its attendant depolarization of 20–30 mV, in contrast to prediction for a 1Cl−/2HCO3− stoichiometry, remains unexplained in this setting.

Our findings contrast with recent studies in mouse pancreatic duct where inhibition of CFTR with short interfering RNA led to a decrease in secretin-stimulated Slc26a6-mediated Cl−/HCO3− exchange and a decrease in HCO3− efflux into the sealed duct lumen (43). These differences suggest distinct consequences of pharmacological inhibition of CFTR and of decreased CFTR polypeptide abundance. In addition, species differences in regulation and functional activity of apical anion exchange and CFTR channel activity may contribute to the divergent HCO3− concentrations of the stimulated pancreatic ductal secretions produced by mouse and guinea pig.

In the classical model of pancreatic duct HCO3− secretion, apical HCO3− secretion is mediated by Cl−/HCO3− exchange, and CFTR supports HCO3− secretion by recycling to the lumen the Cl− entering the cell in exchange for HCO3− (30). In the present study we have demonstrated two coincident responses to pharmacological inhibition of CFTR: acceleration of apical, Slc26a6-like, Cl−-dependent HCO3− secretion in parallel with decreased volume secretion. The data suggest that, in Cl−-rich acinar fluid conditions of the proximal duct, an Slc26a6-like anion exchanger may be the principal route for HCO3− secretion and can compensate for a low HCO3 permselectivity of CFTR.

Conclusion.

Pharmacological inhibition of Cftr accelerates luminal Cl−-dependent HCO3− secretion via Cl−/HCO3− exchange in forskolin-stimulated interlobular duct from guinea pig. The finding that the majority of Cftr-enhanced apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange is H2DIDS sensitive, combined with RT-PCR data from isolated duct, is consistent with an Slc26a6-like anion exchanger functionally coupled to Cftr activity. Our data suggest that this apical Cl−/HCO3− exchanger can compensate for imposed reduction of Cftr activity in stimulated pancreatic interlobular duct. The relative contributions of Cftr, Slc26 Cl−/HCO3− exchangers, and other HCO3− conductances to stimulated pancreatic ductal HCO3− secretion remain to be determined in guinea pig, human, and other species in which pancreatic juice bicarbonate concentration reaches 140 mM. Continued study of pancreatic secretion in these organisms will be important to complement ongoing studies in the mouse, in which the advantage of genetic tractability is accompanied by the considerable disadvantage of reduced HCO3− secretory capacity.

GRANTS

This study was supported by a Novartis Foundation Bursary Award (London, UK), a travel award from the Cell Physiology Core Facility of the Harvard Digestive Disease Center [Boston, MA; National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant DK34854], and a Japan Health Sciences Foundation Fellowship (Tokyo, Japan) awarded to A. K. Stewart. S. L. Alper was supported by NIH Grants DK43495 and DK34854. H. Ishiguro was funded by the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science and the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, Japan.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. S. Naruse for helpful discussions and Prof. M. Otsuki for generous support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Argent B, Gray M, Steward M, Case M. Cell Physiology of Pancreatic Ducts. In: Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract, edited by Johnson LR, Barrett KE, Ghishan FK, Merchant JL, Said HM, Wood JD. Burlington, MA: Elsevier Academic, 2006, p. 1371–1396.

- 2.Caci E, Caputo A, Hinzpeter A, Arous N, Fanen P, Sonawane ND, Verkman AS, Ravazzolo R, Zegarra-Moran O, Galietta LJ. Evidence for direct CFTR inhibition by CFTRinh-172 based on arginine 347 mutagenesis. Biochem J 413: 135–142, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chernova MN, Jiang L, Friedman DJ, Darman RB, Lohi H, Kere J, Vandorpe DH, Alper SL. Functional comparison of mouse Slc26a6 anion exchanger with human SLC26A6 polypeptide variants: differences in anion selectivity, regulation, and electrogenicity. J Biol Chem 280: 8564–8580, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chernova MN, Jiang L, Shmukler BE, Schweinfest CW, Blanco P, Freedman SD, Stewart AK, Alper SL. Acute regulation of the SLC26A3 congenital chloride diarrhoea anion exchanger (DRA) expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Physiol 549: 3–19, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi JY, Muallem D, Kiselyov K, Lee MG, Thomas PJ, Muallem S. Aberrant CFTR-dependent HCO3− transport in mutations associated with cystic fibrosis. Nature 410: 94–97, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark JS, Vandorpe DH, Chernova MN, Heneghan JF, Stewart AK, Alper SL. Species differences in Cl− affinity and in electrogenicity of SLC26A6-mediated oxalate/Cl− exchange correlate with the distinct human and mouse susceptibilities to nephrolithiasis. J Physiol 586: 1291–1306, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dorwart MR, Shcheynikov N, Yang D, Muallem S. The solute carrier 26 family of proteins in epithelial ion transport. Physiology (Bethesda) 23: 104–114, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gray M, O'Reilly C, Winpenny J, Argent B. Anion interactions with CFTR and consequences for HCO3− transport in secretory epithelia. J Korean Med Sci 15 Suppl: S12–S15, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gray MA, Harris A, Coleman L, Greenwell JR, Argent BE. Two types of chloride channel on duct cells cultured from human fetal pancreas. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 257: C240–C251, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greeley T, Shumaker H, Wang Z, Schweinfest CW, Soleimani M. Downregulated in adenoma and putative anion transporter are regulated by CFTR in cultured pancreatic duct cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 281: G1301–G1308, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hegyi P, Gray MA, Argent BE. Substance P inhibits bicarbonate secretion from guinea pig pancreatic ducts by modulating an anion exchanger. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 285: C268–C276, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hegyi P, Rakonczay Z Jr, Tiszlavicz L, Varro A, Toth A, Racz G, Varga G, Gray MA, Argent BE. Protein kinase C mediates the inhibitory effect of substance P on HCO3− secretion from guinea pig pancreatic ducts. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 288: C1030–C1041, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishiguro H, Namkung W, Yamamoto A, Wang Z, Worrell RT, Xu J, Lee MG, Soleimani M. Effect of Slc26a6 deletion on apical Cl−/HCO3− exchanger activity and cAMP-stimulated bicarbonate secretion in pancreatic duct. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 292: G447–G455, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishiguro H, Naruse S, Kitagawa M, Hayakawa T, Case RM, Steward MC. Luminal ATP stimulates fluid and HCO3− secretion in guinea-pig pancreatic duct. J Physiol 519: 551–558, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishiguro H, Naruse S, Kitagawa M, Mabuchi T, Kondo T, Hayakawa T, Case RM, Steward MC. Chloride transport in microperfused interlobular ducts isolated from guinea-pig pancreas. J Physiol 539: 175–189, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishiguro H, Naruse S, Kitagawa M, Suzuki A, Yamamoto A, Hayakawa T, Case RM, Steward MC. CO2 permeability and bicarbonate transport in microperfused interlobular ducts isolated from guinea-pig pancreas. J Physiol 528: 305–315, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ishiguro H, Naruse S, Steward MC, Kitagawa M, Ko SB, Hayakawa T, Case RM. Fluid secretion in interlobular ducts isolated from guinea-pig pancreas. J Physiol 511: 407–422, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishiguro H, Steward M, Naruse S. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator and SLC26 transporters in HCO3− secretion by pancreatic duct cells. Sheng Li Xue Bao 59: 465–476, 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishiguro H, Steward MC, Lindsay AR, Case RM. Accumulation of intracellular HCO3− by Na+-HCO3− cotransport in interlobular ducts from guinea-pig pancreas. J Physiol 495: 169–178, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ishiguro H, Steward MC, Sohma Y, Kubota T, Kitagawa M, Kondo T, Case RM, Hayakawa T, Naruse S. Membrane potential and bicarbonate secretion in isolated interlobular ducts from guinea-pig pancreas. J Gen Physiol 120: 617–628, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishiguro H, Steward MC, Wilson RW, Case RM. Bicarbonate secretion in interlobular ducts from guinea-pig pancreas. J Physiol 495: 179–191, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ko SB, Shcheynikov N, Choi JY, Luo X, Ishibashi K, Thomas PJ, Kim JY, Kim KH, Lee MG, Naruse S, Muallem S. A molecular mechanism for aberrant CFTR-dependent HCO3− transport in cystic fibrosis. EMBO J 21: 5662–5672, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ko SB, Zeng W, Dorwart MR, Luo X, Kim KH, Millen L, Goto H, Naruse S, Soyombo A, Thomas PJ, Muallem S. Gating of CFTR by the STAS domain of SLC26 transporters. Nat Cell Biol 6: 343–350, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lamprecht G, Schaefer J, Dietz K, Gregor M. Chloride and bicarbonate have similar affinities to the intestinal anion exchanger DRA (down regulated in adenoma). Pflügers Arch 452: 307–315, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee MG, Choi JY, Luo X, Strickland E, Thomas PJ, Muallem S. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator regulates luminal Cl−/HCO3− exchange in mouse submandibular and pancreatic ducts. J Biol Chem 274: 14670–14677, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee MG, Wigley WC, Zeng W, Noel LE, Marino CR, Thomas PJ, Muallem S. Regulation of Cl−/HCO3− exchange by cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator expressed in NIH 3T3 and HEK 293 cells. J Biol Chem 274: 3414–3421, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma T, Vetrivel L, Yang H, Pedemonte N, Zegarra-Moran O, Galietta LJ, Verkman AS. High-affinity activators of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) chloride conductance identified by high-throughput screening. J Biol Chem 277: 37235–37241, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Melvin JE, Park K, Richardson L, Schultheis PJ, Shull GE. Mouse down-regulated in adenoma (DRA) is an intestinal Cl−/HCO3− exchanger and is up-regulated in colon of mice lacking the NHE3 Na+/H+ exchanger. J Biol Chem 274: 22855–22861, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Novak I, Greger R. Electrophysiological study of transport systems in isolated perfused pancreatic ducts: properties of the basolateral membrane. Pflügers Arch 411: 58–68, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Novak I, Greger R. Properties of the luminal membrane of isolated perfused rat pancreatic ducts. Effect of cyclic AMP and blockers of chloride transport. Pflügers Arch 411: 546–553, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Padfield PJ, Garner A, Case RM. Patterns of pancreatic secretion in the anaesthetised guinea pig following stimulation with secretin, cholecystokinin octapeptide, or bombesin. Pancreas 4: 204–209, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rakonczay Z, Fearn A, Hegyi P, Boros I, Gray MA, Argent BE. Characterization of H+ and HCO3− transporters in CFPAC-1 human pancreatic duct cells. World J Gastroenterol 12: 885–895, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rakonczay Z, Hegyi P, Hasegawa M, Inoue M, You J, Iida A, Ignath I, Alton EW, Griesenbach U, Ovari G, Vag J, Da Paula AC, Crawford RM, Varga G, Amaral MD, Mehta A, Lonovics J, Argent BE, Gray MA. CFTR gene transfer to human cystic fibrosis pancreatic duct cells using a Sendai virus vector. J Cell Physiol 214: 442–455, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shcheynikov N, Kim KH, Kim KM, Dorwart MR, Ko SB, Goto H, Naruse S, Thomas PJ, Muallem S. Dynamic control of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator Cl−/HCO3− selectivity by external Cl−. J Biol Chem 279: 21857–21865, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shcheynikov N, Wang Y, Park M, Ko SB, Dorwart M, Naruse S, Thomas PJ, Muallem S. Coupling modes and stoichiometry of Cl−/HCO3− exchange by Slc26a3 and Slc26a6. J Gen Physiol 127: 511–524, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sohma Y, Gray MA, Imai Y, Argent HCO3− BE. transport in a mathematical model of the pancreatic ductal epithelium. J Membr Biol 176: 77–100, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steward MC, Ishiguro H, Case RM. Mechanisms of bicarbonate secretion in the pancreatic duct. Annu Rev Physiol 67: 377–409, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Szalmay G, Varga G, Kajiyama F, Yang XS, Lang TF, Case RM, Steward MC. Bicarbonate and fluid secretion evoked by cholecystokinin, bombesin and acetylcholine in isolated guinea-pig pancreatic ducts. J Physiol 535: 795–807, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taddei A, Folli C, Zegarra-Moran O, Fanen P, Verkman AS, Galietta LJ. Altered channel gating mechanism for CFTR inhibition by a high-affinity thiazolidinone blocker. FEBS Lett 558: 52–56, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomas JA, Buchsbaum RN, Zimniak A, Racker E. Intracellular pH measurements in Ehrlich ascites tumor cells utilizing spectroscopic probes generated in situ. Biochemistry 18: 2210–2218, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Venglovecz V, Rakonczay Z Jr, Ozsvari B, Takacs T, Lonovics J, Varro A, Gray MA, Argent BE, Hegyi P. Effects of bile acids on pancreatic ductal bicarbonate secretion in guinea pig. Gut 57: 1102–1112, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walker NM, Simpson JE, Yen PF, Gill RK, Rigsby EV, Brazill JM, Dudeja PK, Schweinfest CW, Clarke LL. Down-regulated in adenoma Cl/HCO3 exchanger couples with Na/H exchanger 3 for NaCl absorption in murine small intestine. Gastroenterology 135: 1645–1653, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Y, Soyombo AA, Shcheynikov N, Zeng W, Dorwart M, Marino CR, Thomas PJ, Muallem S. Slc26a6 regulates CFTR activity in vivo to determine pancreatic duct HCO3− secretion: relevance to cystic fibrosis. EMBO J 25: 5049–5057, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xie Q, Welch R, Mercado A, Romero MF, Mount DB. Molecular characterization of the murine Slc26a6 anion exchanger: functional comparison with Slc26a1. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 283: F826–F838, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang D, Shcheynikov N, Zeng W, Ohana E, So I, Ando H, Mizutani A, Mikoshiba K, Muallem S. IRBIT coordinates epithelial fluid and HCO3−secretion by stimulating the transporters pNBC1 and CFTR in the murine pancreatic duct. J Clin Invest 119: 193–202, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]