Abstract

EGFR inhibitors are increasingly used in combination with radiotherapy in the treatment of various EGFR-overexpressing cancers. However, little is known about the effects of cell cycle status on EGFR inhibitor-mediated radiosensitization. Using EGFR-overexpressing A431 and UMSCC-1 cells in culture, we found that radiation activated the EGFR and ERK pathways in quiescent cells, leading to progression of cells from G1 to S, but this activation and progression did not occur in proliferating cells. Inhibition of this activation blocked S-phase progression and protected quiescent cells from radiation-induced death. To determine if these effects were caused by EGFR expression, we transfected CHO cells, which lack EGFR expression, with EGFR expression vector. EGFR expressed in CHO cells also became activated in quiescent cells, but not in proliferating cells after irradiation. Moreover, quiescent cells expressing EGFR underwent increased radiation-induced clonogenic death as compared to both proliferating CHO cells expressing EGFR and quiescent wild-type CHO cells. Our data demonstrate that radiation-induced enhancement of cell death in quiescent cells involves activation of the EGFR and ERK pathways. Furthermore, they suggest that EGFR inhibitors may protect quiescent tumor cells, whereas radiosensitization of proliferating cells may be caused by downstream effects such as cell cycle redistribution. These findings emphasize the need for careful scheduling of treatment with the combination of EGFR inhibitors and radiation and suggest that EGFR inhibitors might best be given after radiation in order to optimize clinical outcome.

Keywords: EGFR, Radiation sensitivity, Radiation therapy, Cell cycle

Introduction

Inhibitors of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) have shown considerable promise when used alone and in combination with chemotherapy and radiation therapy (1). In particular, the outcome of treatment with the combination of EGFR inhibition and radiation therapy in preclinical studies (2-6) and in a randomized clinical trial in head and neck cancer (7, 8) is superior to that of radiation therapy alone. These results have fueled interest in optimizing the interaction of EGFR inhibition with radiation therapy.

As tumors are comprised of proliferating and quiescent cells, understanding the effects of the proliferation status of cells could represent a key aspect in optimizing EGFR-radiation interactions. Schmidt-Ullrich and colleagues found that radiation can stimulate EGFR phosphorylation in serum-starved, growth-arrested cells (with low background EGFR levels). If this EGFR stimulation were part of a survival signal, EGFR inhibitors could sensitize cells to radiation (9). Conversely, EGFR stimulation via its ligand could stimulate G0 quiescent cells to enter S-phase. If this occurred in the presence of unrepaired radiation-induced DNA damage, it could increase radiation sensitivity. In this case, EGFR inhibition might actually be radioprotective.

EGFR inhibitors might interact quite differently with irradiated proliferating cells. These cells have high levels of EGFR activation at baseline and the additional stimulation by radiation appears to have little effect on this already high baseline level (10). However, prolonged exposure to EGFR inhibitors can place cells in a relatively sensitive phase of the cell cycle, late G1, which can increase radiation sensitivity (11)

To better understand the effects of EGFR inhibitors on radiosensitivity with respect to cellular proliferation status, we compared the effects of radiation on EGFR-overexpressing cells that were proliferating versus quiescent cells arrested in G0/1. In the case of quiescent cells, we hypothesized that radiation would cause stimulation of EGFR, over low baseline levels, which would activate ERK and drive cells into S-phase. This would lead to a decrease in DNA repair and increased radiation-induced cell death. In contrast, we anticipated that proliferating cells would not exhibit increased phosphorylation of EGFR over already high baseline levels (10) and, therefore, proliferating cells might be relatively resistant to radiation as compared to quiescent cells in G0/1. When we found that this was the case, we developed a system using wild type CHO cells, which do not express EGFR (12), and CHO cells that were transfected with the EGFR expression vector. This system permitted us to specifically determine the role of radiation-induced EGFR activation and downstream stimulation on radiation sensitivity and to understand the difference in radiation sensitivity between proliferating and quiescent cells whose growth is driven by EGFR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Phospho-epidermal growth factor receptor (pEGFR; Y845), phospho-ERK (pERK; T202/Y204), GAPDH and total ERK antibodies, and U0126 were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). EGFR antibody (Sc-03) was acquired from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). γH2ax antibody was acquired from Upstate (Charlottesville, VA). EGF was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Erlotinib was kindly provided by Genentech Inc. (San Francisco, CA).

Cell culture

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO-K1) and A431 cell lines were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). The human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell line UMSCC-1 was a gift from Dr. Thomas E. Carey (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI). All cell lines were grown in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% cosmic calf serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT). Experiments were conducted in serum-containing media. For in vitro experiments, cells were released from flasks using PBS containing 0.01% trypsin and 0.20 mmol/L EDTA, and plated two days before treatment. For experiments with proliferating cells, 6 × 105 cells were plated in 10 cm Petri dishes in 10 ml medium, and the cultures were between 30% and 50% confluent at the time of harvest. For quiescent culture, 106 cells were plated in 10 cm Petri dishes in 10 ml medium; once the culture plate reached approximately 90% confluence (∼5-7 days after seeding), the growth medium was replaced. Two days later, cells were irradiated and analyzed.

Radiation and Drug Treatment

Cells were irradiated at room temperature at a dose rate of 3 Gy/min using a Pantak DXT300 orthovoltage unit. Dosimetry was carried out using an ionization chamber connected to an electrometer system that was directly traceable to a National Institute of Standards and Technology calibration. For drug treatment, Cells were briefly exposed to 10 μM U0126 (1h), 10 ng/ml EGF (30 min) or 3 μM Erlotinib (2h). Growth medium was replaced following drug treatment.

Flow cytometry

Cells were harvested and fixed in 70% ethanol. For DNA content flow cytometry, cells were stained with a solution of 0.018 mg/mL propidium iodide (PI) and 0.04 mg/mL RNase A. For bromodeoxyuridine (BrdUrd) flow cytometry, cells were exposed to 30 μmol/L BrdUrd for 15 minutes and processed as described previously (13) using an antibody recognizing BrdUrd (PharMingen, San Diego, CA) followed by a FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO). In each experiment, a control sample without BrdUrd was processed to determine the background signal. Ten thousand or forty thousand cells were analyzed using on a Beckman Coulter Epics Elite or a Becton Dickinson FACScan (San Jose, CA), respectively. The graphs were generated using WinMDI software.

Immunoblotting

Cells were scraped into PBS containing sodium orthovanadate and a protease inhibitor mixture (Complete Protease Inhibitor, Roche Diagnostic Co., Indianapolis, IN). Cells were incubated for 15 min on ice in Laemmli buffer (63 mM Tris-HCl, 2% (w/v) SDS, 10% (v/v) glycerol, and 0.005% (w/v) bromphenol blue) containing 100 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3Vo4, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 1 μg/ml aprotinin. After sonication, particulate material was removed by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. The soluble protein fraction was heated to 95°C for 5 min, then applied to a 4-12% bis-tris precast gel (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and transferred onto a PVDF membrane. Membranes were incubated for 1 h at room temperature in blocking buffer consisting of 3% BSA and 1% normal goat serum in Tris-buffered saline [137 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20]. Membranes were subsequently incubated overnight at 4°C with 1 μg/ml primary antibody in blocking buffer, washed, and incubated for 1 h with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA). After three additional washes in Tris-buffered saline, bound antibody was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence plus reagent (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). For quantification of relative protein levels, immunoblot films were scanned and analyzed using ImageJ 1.32j software (NIH, Bethesda, MD). Unless otherwise indicated, the relative protein levels shown represent a comparison to untreated controls.

Clonogenic cell survival assay

Clonogenic assays were performed using standard techniques (4, 11) in which cells were subcultured at clonal density immediately after irradiation. Cell survival curves were fitted using a linear quadratic equation, and the mean inactivation dose (MID) was calculated according to the method of Fertil et al. (14). The difference in radiosensitivity of quiescent and proliferating cells was compared by the ratio of the mean inactivation doses. Similarly, the radiation enhancement ratio (ER) was calculated by dividing the mean inactivation dose under control conditions by the mean inactivation dose after drug treatment.

Transfections

CHO cells were transiently transfected with the constructs encoding either human wild-type EGFR or empty vector (pcDNA 3.0, a kind gift from Dr. Len Neckers, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda) using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, for each transfection reaction, 10 μl Lipofectamine was incubated with 300 μl of Opti-MEM for 10 minutes. Following that, 2 μg of wild-type EGFR or empty vector plasmid was added and incubated for 30 minutes. This mixture was added to cells and incubated overnight. Transfections were carried out when CHO cells were at 30-40% (for proliferating condition experiments) or 90% (for quiescent condition experiments) density. Transfection efficiency was similar for proliferating and quiescent cells (approximately 50%). Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were irradiated and processed for colony formation assay.

Statistics

Results are presented as mean ± SE of at least three experiments. Student’s t test was used to assess the statistical significance of differences. A significance level threshold of p<0.05 was used in this study.

RESULTS

Radiosensitivity and growth factor signaling in quiescent and proliferating cells

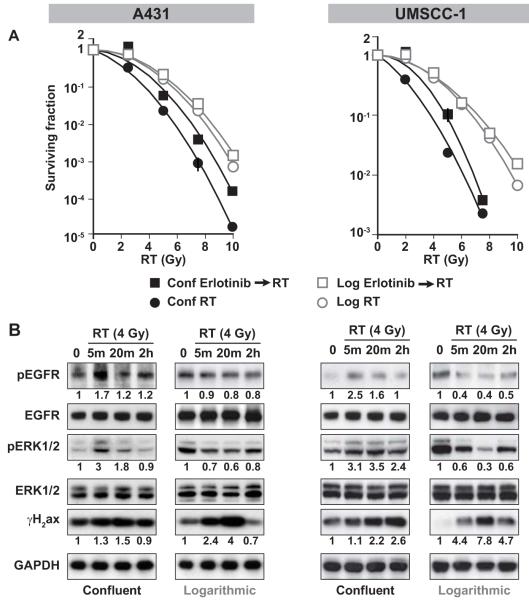

We selected UMSCC-1 human head and neck cancer cells and A431 human epithelial cancer cells for study, as both are driven by EGFR overexpression (15). We first sought to determine the relative radiation sensitivity of quiescent and proliferating A431 cells. We found that quiescent A431 cells (G0/1 ≥ 80%) were more sensitive to radiation than proliferating A431 cells (G1 ≤ 50%) (enhancement ratio =1.89 ± 0.02; p <0.001; Figure 1A). Similar experiments in UMSCC-1 cells confirmed that quiescent cells were more radiosensitive than proliferating cells (enhancement ratio = 1.70± 0.01; p <0.001; Figure 1A). Next, we used the EGFR inhibitor erlotinib to assess the contribution of EGFR activation to radiation sensitivity in quiescent and proliferating cells, reasoning that a brief exposure to drug would inhibit pEGFR without confounding effects such as cell cycle changes (10, 16). We found that a two-hour pretreatment with 3 μM erlotinib significantly protected quiescent cells (enhancement ratio = 0.67 ± 0.01), and also slightly but significantly protected proliferating cells (enhancement ratio = 0.91 ± 0.04). Erlotinib also significantly protected UMSCC-1 quiescent cells (enhancement ratio = 0.78 ± 0.05), and, to a lesser degree, proliferating cells (enhancement ratio = 0.89 ± 0.07). These data support our hypothesis that EGFR-driven, quiescent cells are more radiosensitive than proliferating cells, and that EGFR inhibition is radioprotective, particularly in quiescent cells.

Figure 1. Effect of cell culture condition on the radiation sensitivity of A431 and UMSCC-1 cells.

A). Proliferating and quiescent A431 and UMSCC-1 cells were exposed to various doses of radiation and plated for clonogenic survival assays. Quiescent cells were more sensitive to radiation than proliferating cells (ratio of surviving fractions = 2.70 at 4 Gy). B). Cells were treated with 4 Gy and harvested at various time points after radiation. Levels of pEGFR, EGFR, pERK1/2, ERK1/2, γH2ax and GAPDH proteins were measured in the cell lysates. Immediate activation of EGFR and ERK (by 5 min) was induced in quiescent cells, but not in proliferating cells. DNA damage in proliferating cells was repaired by 2 hours, but remained unrepaired in quiescent cells.

We next sought to determine if EGFR and ERK signaling were differentially affected after irradiation in quiescent and proliferating A431 cells and UMSCC-1 cells. In quiescent cells, irradiation induced immediate (5 min) EGFR and ERK activation, both of which returned to normal levels by 2 hours (Figure 1B). In contrast, there was no radiation-induced EGFR and ERK phosphorylation in proliferating cells; in fact pEGFR and pERK levels were decreased as we have reported previously (Figure 1B) (10). We also noticed that the unresolved DNA lesions in quiescent UMSCC-1 cells as reflected by high γH2ax levels were prolonged, as γH2ax levels had not decreased by 2 hours after the initial spike in UMSCC-1 cells (Figure 1B). In contrast, γH2ax levels in irradiated proliferating cells were resolved within 2 hours. These findings demonstrate that in EGFR-driven cells, irradiation induces EGFR-ERK signaling and unrepaired DNA damage in quiescent cells, but these effects were not found in proliferating cells.

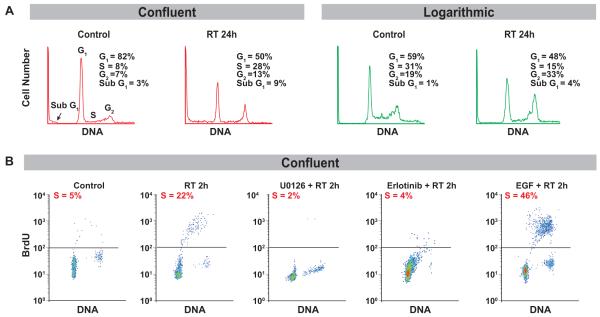

We then investigated the effect of radiation on cell cycle distribution of quiescent and proliferating A431 cells after irradiation (4 Gy). One parameter flow cytometry showed an increase in apoptotic cells, as reflected by an increase in sub G1 content in G0 cells compared to proliferating cells 24 hours after radiation (Figure 2A). This analysis also revealed that radiation caused a significant movement of cells with G1 DNA content into S in the initially quiescent cell population (percent in S-phase before and after radiation was 8% ± 3% and 28 ± 6% respectively), while initially proliferating cells did not undergo this movement after irradiation (percent in S-phase before and after irradiation was 31% ± 5% and 15% ± 3% respectively) (Figure 2A). To further assess the significance of the response to radiation with regard to cell-cycle progression in quiescent cells, we examined the effect of radiation on the cell cycle by measuring BrdUrd incorporation to assess cells in S-phase. We found that in quiescent A431 cells, irradiation (4 Gy) resulted in an increased S-phase fraction within 2h (Figure 2B) that lasted for 24h (data not shown), indicating that radiation stimulated G1 to S phase progression (5% to 22%). Similar results were obtained in UMSCC-1 cells (Supplemental Figure 1). A brief, nontoxic exposure to EGFR and ERK activity inhibitors, erlotinib and U0126 respectively, blocked the progression of quiescent cells to S-phase (Figure 2B), supporting the involvement of EGFR-ERK signaling in S-phase progression in response to radiation. Conversely, EGF stimulation in these cells increased the progression of cells to S-phase in response to radiation (22 to 46%), confirming the role of EGFR activation in this phenomenon (Figure 2B). These findings suggest that the increased radiosensitivity of quiescent cells as compared to proliferating cells is driven by the EGFR-ERK signaling pathway.

Figure 2. Effect of radiation on cell cycle in A431 quiescent cells.

A). Cell cycle distribution was analyzed by flow cytometry as described in Materials and Methods. An increase in apoptotic cells was observed in quiescent cells as compared to proliferating cells at 24 hours after radiation (4 Gy). Radiation induced substantial movement of cells from G1 to S-phase in quiescent cells, but not in proliferating cells. B). Quiescent A431 cells were treated with 10 μM U0126 (1h), 10 ng/ml EGF (30 min) and 3 μM Erlotinib (2h) and exposed to 4 Gy radiation, and harvested 2h later. BrdUrd incorporation was performed as described in Materials and Methods. U0126 and erlotinib each blocked the progression of quiescent cells to S-phase in response to radiation. EGF stimulation induced quiescent cell progression to S-phase in response to radiation.

Effect of growth factor stimulation or inhibition on radiation sensitivity of quiescent and proliferating cells

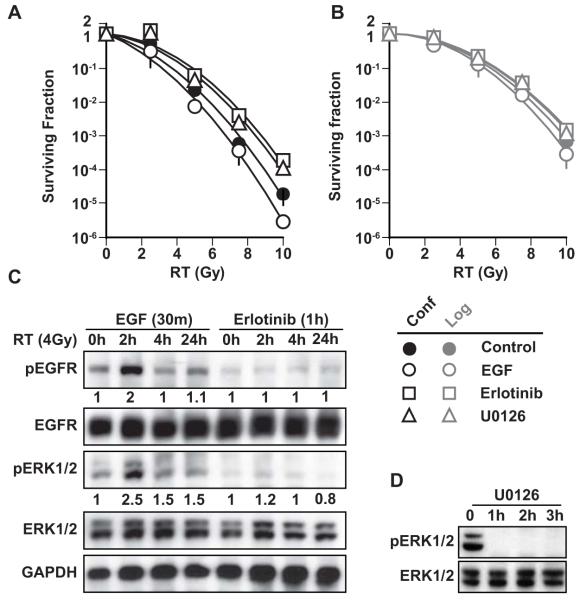

We then investigated the role of radiation-induced EGFR phosphorylation in radiation-induced cell death. As shown in Figure 2B, EGF pre-incubation potentiated quiescent cell transition from G1 to S-phase; we therefore hypothesized that EGF pre-incubation would sensitize quiescent cells to radiation. We further hypothesized that treatment with a brief, exposure to erlotinib (3 μM) would block this transition and would therefore protect cells from radiation-induced clonogenic death. Indeed, we found that EGF pretreatment moderately sensitized A431 cells to radiation (enhancement ratio = 1.3 ± 0.01), and erlotinib pretreatment caused significant radioprotection (enhancement ratio = 0.54 ± 0.07; p<0.002) (Figure 3A). We further sought to determine the role of radiation-induced ERK phosphorylation in radiation-induced cell death in quiescent cells. As shown in Figure 2B, U0126 inhibited cell transition from G1 to S-phase. We hypothesized that ERK inhibition, achieved using a brief, nontoxic concentration of U0126, and would protect cells from radiation-induced cell death. Indeed, we found that U0126 (10 μM) protected quiescent cells from radiation-induced death (Figure 3A). In contrast, neither EGF, erlotinib, nor U0126 significantly affected the radiosensitivity of proliferating cells (Figure 3B). In quiescent cells, EGF pretreatment potentiated both EGFR and ERK activation in response to radiation, whereas erlotinib abrogated this activation (Figure 3C). These signaling changes did not occur in proliferating cells (data not shown). Furthermore, U0126 completely blocked ERK activation in response to radiation after 1h (Figure 3D), confirming that EGFR-ERK activation is important in radiation-induced cell death. These findings suggest that radiation-induced EGFR phosphorylation and subsequent ERK phosphorylation drives irradiated quiescent cells into S-phase, leading to cell death.

Figure 3. Effect of EGFR inhibition by erlotinib, stimulation by EGF, or ERK inhibition by U0126 on radiation sensitivity of A431 cells.

A). Quiescent and B). Proliferating cells were pre-treated with erlotinib (3 μM for 1h), EGF (10 ng/ml for 30 min) or U0126 (10 μM for 1h) and exposed to various doses of radiation. Cells were immediately plated for colony formation. EGF pretreatment sensitized cells to radiation (enhancement ratio = 1.3 ± 0.01), and both erlotinib and U0126 pretreatment protected cells from radiation-induced cell death (enhancement ratio = 0.53 ± 0.25; p<0.002 and 0.62 ±0.14; p<0.005, respectively). C). Using the same conditions of drug treatment, cells were harvested at various time points after 4 Gy radiation. Immunoblotting was performed for pEGFR, EGFR, pERK1/2, ERK1/2 and GAPDH. D). Cells were harvested at 1, 2 and 3h after U0126 treatment and immunoblotted for pERK1/2 and ERK1/2.

Effects of exogenously expressed EGFR on radiation-induced clonogenic death in proliferating and quiescent cells

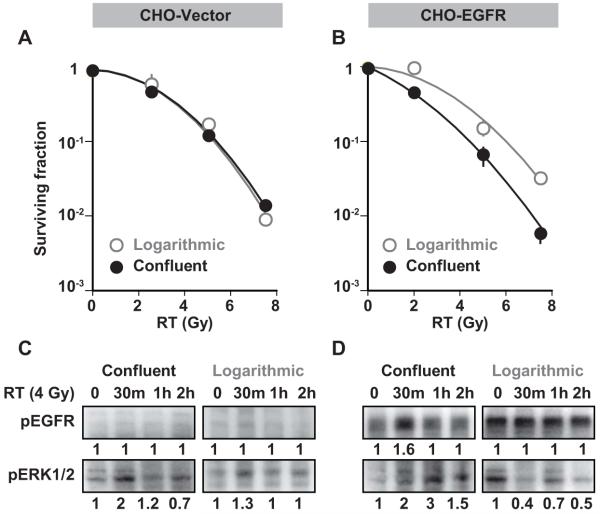

Finally, we sought to explicitly assess the influence of proliferation status on radiosensitivity in CHO cells, which lack EGFR, and in CHO cells transfected so that they express EGFR. CHO cells are capable of expressing EGFR and have been used in studies of EGFR trafficking and function (17-21). Our experiments show that in EGFR-expressing CHO cells, EGFR and ERK are phosphorylated upon EGF stimulation (data not shown) confirming that this pathway functions appropriately in this system. In contrast to our findings in EGFR-expressing A431 cells, we found no difference between the radiation sensitivities of quiescent and proliferating wild-type CHO cells (enhancement ratio = 1.01 ± 0.01), which is consistent with a critical role for EGFR in radiation response (Figure 4A). Furthermore, quiescent CHO cells ectopically expressing EGFR, showed increased radiation sensitivity (enhancement ratio = 1.5± 0.2, p <0.001) compared to proliferating cells (Figure 4B). Finally, we confirmed that ectopic expression of EGFR in CHO cells resulted in EGFR activation in response to radiation only in quiescent cells and not in proliferating cells (Figure 4C, D). These results confirm the role of EGFR activation in radiation-induced cell death in quiescent cells.

Figure 4. Effect of EGFR expression on radiation sensitivity in proliferating and quiescent CHO cells.

Proliferating and quiescent CHO cells were transfected with A) empty vector plasmids or B) wild-type EGFR plasmids and exposed to various doses of radiation and plated for clonogenic survival assays. Those transfected with empty vector plasmids showed no difference in clonogenic survival at any dose of radiation. In CHO cells transfected with EGFR, clonogenic survival revealed increased radiation sensitivity of quiescent cells compared to proliferating cells (enhancement ratio = 1.5 ± 0.2, p <0.001). C) Proliferating and quiescent cells were transfected with empty vector plasmids or D) wild type EGFR plasmids and treated with 4Gy radiation. Cells were harvested at various time points and immunoblotted for pEGFR and pERK. Ectopic expression of EGFR resulted in EGFR activation after radiation only in quiescent cells, and not in proliferating cells.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have demonstrated that EGFR inhibition has a distinctly different effect on the radiosensitivity of quiescent and proliferating EGFR-driven cells in culture. Radiation-induced activation of EGFR in quiescent cells induces progression into S-phase, slows DNA repair, and enhances radiation-induced cell death. The initial effect of EGFR inhibition is to block these processes and to cause radioprotection. However, in proliferating cells, radiation induces neither EGFR activation nor S-phase entry, and (short term) EGFR inhibition has little effect on radiation-induced death. Collectively, our data demonstrate that cellular proliferation status profoundly affects EGFR and ERK activation in response to radiation, which significantly affects radiosensitivity. As tumors are composed of a heterogeneous mixture of both proliferating and quiescent cells, our findings support a more complicated model of tumor response to EGFR inhibition and radiation, in which the overall effect of EGFR inhibition may vary as a function of the number of quiescent versus proliferating cells.

Our findings in quiescent cells are consistent with prior reports that radiation stimulates EGFR activation in growth-arrested cells (9, 22). This radiation-induced EGFR activation induces progression to S-phase, increasing radiosensitivity and cell death. However, our results differ in proliferating cells, wherein we found that radiation did not induce EGFR activation. This is in keeping with our previous work, in which we reported that in proliferating cells radiation appears to have little effect on already high levels of EGFR activation; instead, radiation actually decreases ERK activity in an ATM-dependent manner (10). It now appears that one cannot generalize that quiescent cells are less radiosensitive than proliferating cells(23); in fact, the opposite is found in EGFR-driven cells. These findings also suggest that the effects of radiation should also be evaluated in cells that are driven by similar tyrosine kinase proteins, including HER2 and IGF-1 overexpressing cells.

Note that the conditions we used in our study differed from those that produce “potentially lethal damage repair”, in which cells that are held in plateau phase for 24 hours after relatively high doses of radiation (10 Gy) show decreased sensitivity to radiation compared to those that are plated immediately after radiation (24, 25). We chose to use a lower dose of radiation (4 Gy) and to wait less than 4 hours after radiation before processing cells to avoid confounding effects. Thus, our finding of increased radiation sensitivity in EGFR expressing confluent cells is not in conflict with previous studies of PLDR.

Since we have observed defective repair capabilities of quiescent cells as compared to proliferating cells, it appears that EGFR and ERK activation in quiescent cells may inappropriately drive the cells to S-phase through a defective G1/S checkpoint, enhancing cellular radiosensitivity. This finding is consistent with the mechanism of action of chemoradiotherapy, such as gemcitabine or 5-fluorouracil, in combination with radiation, whereby inappropriate progression through S-phase increases radiosensitivity (26-28). This model of increased cell killing following EGFR activation also resembles chemotherapy-induced cell death in that we previously reported that EGFR activation in response to chemotherapy is an indispensable event in subsequent cell death (29).

Our study helps to distinguish the direct, early effect of EGFR inhibition from the downstream effects of EGFR inhibition. The direct effect of EGFR inhibition can be mild to significant radioprotection, while downstream effects can induce accumulation in G1, leading to radiosensitization. As such, the study of activation of EGFR and ERK in response to radiation has yielded varying results, suggesting that this activation may depend on culture conditions, time of monitoring response, and dose of radiation. For instance, Harari and Huang found that 24 hours after EGFR inhibition, UMSCC1 cells showed G1 arrest, decreased S-phase fraction, and enhanced radiosensitivity (11). Tanaka et al. also found enhanced radiosensitivity in NSCLC cells 24 hours after EGFR inhibition (30). In our study, we irradiated cells two hours after exposure to erlotinib, when EGFR was inhibited but before substantial cell cycle effects occurred; these conditions produced radioprotection.

The effects of radiation on ERK activity can also differ depending on direct versus indirect induction. As we and others (9, 31, 32) have found, ERK can be stimulated directly from EGFR activation in quiescent cells, whereas our previous work shows that ERK can be inhibited in response to radiation via MKP-1 activation in proliferating cells. Our results argue for a more complex theory of the mechanism underlying the effects of radiation on the EGFR-ERK pathway.

In this work, we show that quiescent and proliferating cells that are EGFR-driven differ in radiosensitivity and response to EGFR inhibition. At present, the mechanism of the interaction between DNA damage-repair pathways and EGFR and ERK activation in quiescent or proliferating cells has yet to be determined (30). Further studies are necessary to elucidate the differences between radiation-induced EGFR and ERK activation and their unique roles in cell cycle progression. Additionally, other downstream pathways of radiation-induced EGFR activation in quiescent cells aside from ERK might also be explored in this context. It is already clear that in vitro studies combining EGFR and ERK inhibitors with radiation must be carefully designed to take cellular proliferation status into consideration. Improved understanding of the consequences of these cell cycle effects in combination treatment with EGFR inhibitors, radiation, and/or chemotherapeutic agents will have important ramifications in the optimization of clinical treatment schedule. Specifically, our findings indicate that cells may be protected from irradiation within the first several hours after receiving erlotinib, suggesting that radiation should precede treatment with an EGFR inhibitor. Furthermore, our results support a potential role for Ki-67, which denotes proliferating cells, as a biomarker, as the overall effect of EGFR inhibition may vary as a function of the number of quiescent versus proliferating cells.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mats Ljungman and Christine E. Canman for helpful discussions, and Steven Kronenberg for assistance in making figures.

Grant support: NIH through the University of Michigan Head and Neck Specialized Program of Research Excellence grant (5 P50 CADE97248), MICHR, University of Michigan Cancer Center support grant (5 P30 CA46592), and Howard Hughes Medical Institute Training Fellowship to Hiniker, SM.

References

- 1.Nyati MK, Morgan MA, Feng FY, Lawrence TS. Integration of EGFR inhibitors with radiochemotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:876–85. doi: 10.1038/nrc1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang SM, Harari PM. Modulation of radiation response after epidermal growth factor receptor blockade in squamous cell carcinomas: inhibition of damage repair, cell cycle kinetics, and tumor angiogenesis. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:2166–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bianco C, Tortora G, Bianco R, et al. Enhancement of antitumor activity of ionizing radiation by combined treatment with the selective epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitor ZD1839 (Iressa) Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:3250–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nyati MK, Maheshwari D, Hanasoge S, et al. Radiosensitization by pan ErbB inhibitor CI-1033 in vitro and in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:691–700. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-1041-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chinnaiyan P, Huang S, Vallabhaneni G, et al. Mechanisms of enhanced radiation response following epidermal growth factor receptor signaling inhibition by erlotinib (Tarceva) Cancer Res. 2005;65:3328–35. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raben D, Helfrich B, Chan DC, et al. The effects of cetuximab alone and in combination with radiation and/or chemotherapy in lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:795–805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vermorken JB, Mesia R, Rivera F, et al. Platinum-based chemotherapy plus cetuximab in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1116–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonner JA, Harari PM, Giralt J, et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:567–78. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmidt-Ullrich RK, Mikkelsen RB, Dent P, et al. Radiation-induced proliferation of the human A431 squamous carcinoma cells is dependent on EGFR tyrosine phosphorylation. Oncogene. 1997;15:1191–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nyati MK, Feng FY, Maheshwari D, et al. Ataxia telangiectasia mutated down-regulates phospho-extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 via activation of MKP-1 in response to radiation. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11554–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harari PM, Huang SM. Head and neck cancer as a clinical model for molecular targeting of therapy: Combining EGFR blockade with radiation. International Journal of Radiation Oncology Biology Physics. 2001;49:427–33. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)01488-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krug AW, Schuster C, Gassner B, et al. Human epidermal growth factor receptor-1 expression renders Chinese hamster ovary cells sensitive to alternative aldosterone signaling. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:45892–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208851200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoy CA, Seamer LC, Schimke RT. Thermal denaturation of DNA for immunochemical staining of incorporated bromodeoxyuridine (BrdUrd): critical factors that affect the amount of fluorescence and the shape of BrdUrd/DNA histogram. Cytometry. 1989;10:718–25. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990100608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fertil B, Malaise EP. Intrinsic radiosensitivity of human cell lines is correlated with radioresponsiveness of human tumors: analysis of 101 published survival curves. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1985;11:1699–707. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(85)90223-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffmann T, Hafner D, Ballo H, Haas I, Bier H. Antitumor activity of anti-epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibodies and cisplatin in ten human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma lines. Anticancer Res. 1997;17:4419–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chun PY, Feng FY, Scheurer AM, Davis MA, Lawrence TS, Nyati MK. Synergistic effects of gemcitabine and gefitinib in the treatment of head and neck carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:981–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ravid T, Heidinger JM, Gee P, Khan EM, Goldkorn T. c-Cbl-mediated ubiquitinylation is required for epidermal growth factor receptor exit from the early endosomes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:37153–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403210200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soubeyran P, Kowanetz K, Szymkiewicz I, Langdon WY, Dikic I. Cbl-CIN85-endophilin complex mediates ligand-induced downregulation of EGF receptors. Nature. 2002;416:183–7. doi: 10.1038/416183a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boerner JL, Demory ML, Silva C, Parsons SJ. Phosphorylation of Y845 on the epidermal growth factor receptor mediates binding to the mitochondrial protein cytochrome c oxidase subunit II. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:7059–71. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.16.7059-7071.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clark S, Dunlop M. Modulation of phospholipase A2 activity by epidermal growth factor (EGF) in CHO cells transfected with human EGF receptor. Role of receptor cytoplasmic subdomain. Biochem J. 1991;274(Pt 3):715–21. doi: 10.1042/bj2740715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olsson P, Gedda L, Goike H, et al. Uptake of a boronated epidermal growth factor-dextran conjugate in CHO xenografts with and without human EGF-receptor expression. Anticancer Drug Des. 1998;13:279–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yacoub A, McKinstry R, Hinman D, Chung T, Dent P, Hagan MP. Epidermal growth factor and ionizing radiation up-regulate the DNA repair genes XRCC1 and ERCC1 in DU145 and LNCaP prostate carcinoma through MAPK signaling. Radiat Res. 2003;159:439–52. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2003)159[0439:egfair]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall EJ, Giaccia AJ. Radiobiology for the Radiologist. 6ed Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weichselbaum RR, Little JB. Radioresistance in some human tumor cells conferred in vitro by repair of potentially lethal X-ray damage. Radiology. 1982;145:511–3. doi: 10.1148/radiology.145.2.7134460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weichselbaum RR, Malcolm AW, Little JB. Fraction size and the repair of potentially lethal radiation damage in a human melanoma cell line. Possible implications for radiotherapy. Radiology. 1982;142:225–7. doi: 10.1148/radiology.142.1.7053535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lawrence TS, Blackstock AW, McGinn C. The mechanism of action of radios ensitization of conventional chemotherapeutic agents. Seminars in Radiation Oncology. 2003;13:13–21. doi: 10.1053/srao.2003.50002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGinn CJ, Miller EM, Lindstrom MJ, Kunugi KA, Johnston PG, Kinsella TJ. The role of cell-cycle redistribution in radiosensitization - implications regarding the mechanism of fluorodeoxyuridine radiosensitization. International Journal of Radiation Oncology Biology Physics. 1994;30:851–9. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)90360-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson GD, Bentzen SM, Harari PM. Biologic basis for combining drugs with radiation. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2006;16:2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feng FY, Varambally S, Tomlins SA, et al. Role of epidermal growth factor receptor degradation in gemcitabine-mediated cytotoxicity. Oncogene. 2007;26:3431–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanaka T, Munshi A, Brooks C, Liu J, Hobbs ML, Meyn RE. Gefitinib radiosensitizes non-small cell lung cancer cells by suppressing cellular DNA repair capacity. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1266–73. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dent P, Yacoub A, Contessa J, et al. Stress and radiation-induced activation of multiple intracellular signaling pathways. Radiat Res. 2003;159:283–300. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2003)159[0283:sariao]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lammering G, Hewit TH, Hawkins WT, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor as a genetic therapy target for carcinoma cell radiosensitization. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:921–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.12.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]