SUMMARY

Asimadoline is a potent κ-opioid receptor agonist with a diaryl acetamide structure. It has high affinity for the κ receptor, with IC50 of 5.6 nM (guinea pig) and 1.2 nM (human recombinant), and high selectively with κ: μ: δ binding ratios of 1:501:498 in human recombinant receptors. It acts as a complete agonist in in vitro assay. Asimadoline reduced sensation in response to colonic distension at subnoxious pressures in healthy volunteers and in IBS patients without alteration of colonic compliance. Asimadoline reduced satiation and enhanced the postprandial gastric volume (in female volunteers). However, there were no significant effects on gastrointestinal transit, colonic compliance, fasting or postprandial colonic tone. In a clinical trial in 40 patients with functional dyspepsia (Rome II), asimadoline did not significantly alter satiation or symptoms over 8 weeks. However, asimadoline, 0.5 mg, significantly decreased satiation in patients with higher postprandial fullness scores, and daily postprandial fullness severity (over 8 weeks); the asimadoline 1.0 mg group was borderline significant. In a clinical trial in patients with IBS, average pain 2 hours post-on-demand treatment with asimadoline was not significantly reduced. Post-hoc analyses suggest asimadoline was effective in mixed IBS. In a 12-week study in 596 patients, chronic treatment with asimadoline, 0.5 mg and 1.0 mg, was associated with adequate relief of pain and discomfort, improvement in pain score and number of pain free days in patients with IBS-D. The 1.0 mg dose was also efficacious in IBS-alternating. There were also weeks with significant reduction in bowel frequency and urgency. Asimadoline has been well tolerated in human trials to date.

Keywords: Asimadoline, irritable bowel syndrome, bowel, opioid, receptor, kappa

IRRITABLE BOWEL SYNDROME THERAPY AND UNMET NEED

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is characterized by abdominal discomfort or pain in association with altered bowel habit or incomplete stool evacuation. The estimated prevalence in the community is about 10%, and the incidence is 1±2% per annum (1,2). This is a heterogeneous disorder, and important mechanisms include hypersensitivity of the gut, altered motility, psychosocial disorder, and mild inflammation possibly associated with alterations in the colonic microbiome or endogenous factors such as bile acids or products of digestion. Gastrointestinal infection may serve as a triggering or antecedent factor (3).

Current therapy for irritable bowel syndrome focuses on the major symptom experienced by the patient, diarrhea, constipation, or a combination of pain, gas, and bloating, and includes loperamide and alosetron for diarrhea, fiber, osmotic agents (such as magnesium salts or lactulose, stimulant laxatives and secretory agents such as lubiprostone for constipation, or calcium channel blocker and muscle relaxants for pain, gas, and bloating. A systematic review suggested that smooth muscle relaxants are beneficial for abdominal pain, although the trials were relatively small, the classes of agents diverse, and the overall efficacy uncertain in the more recent analyses.

Among patients with a significant psychological or psychiatric component of the irritable bowel syndrome, low-dose antidepressants have also been effective in relief of pain, depression, and diarrhea (4). Current medical therapies for pain and discomfort associated with irritable bowel syndrome have been insufficiently effective, and there is a need for novel approaches to treatment (5,6).

ROLE OF OPIATE RECEPTORS IN VISCERAL PAIN

The three major opioid receptors, κ, μ, and δ, are distributed in the peripheral and central nervous systems (7,8) and are known to modulate visceral nociception. The κ-opioid receptors participate in the inhibition of perception of noxious stimuli from the gastrointestinal tract, as shown in well-validated models of visceral sensation (9–11).

Available opioid agonists which bind to μ receptors relieve pain, but they usually result in many adverse effects such as constipation or in central side effects including opioid dependence (12,13). Such adverse effects preclude their general use in clinical practice for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). In contrast, peripheral κ-opioid receptor agonists seem to be devoid of these side effects.

κ-Opiate Receptors in Gastrointestinal Tract

The distribution of μ receptors differs from that of κ receptors; there is a greater abundance of μ receptors in all layers of the rat intestine submucosal regions and the interstitial cell layer (14). In contrast, there were more κ than μ receptors in the myenteric plexus. Using a combination of mRNA quantification and immunohistochemical visualization, stomach and proximal colon had the largest expression of both μ and κ opiate receptors. The expression of κ receptors in the proximal colon of rat was 40% that in the rat brain (15).

From a functional perspective, κ agonists inhibit visceral afferents that reflexly inhibit intestinal motility after laparotomy and intestinal handling (16–18). μ opiate agonists, such as fentanyl and morphine, do not reverse this inhibition. This suggests that the visceral analgesic effects are potentially unrelated to central analgesia in reversing the ileus associated with bowel handling in animal models.

Many of the effects of κ-opiate receptors were initially evaluated through the actions of fedotozine and U50,488. κ-opiate mechanisms appear important in spinal in addition to peripheral analgesia (19,20). As a prototype κ-opiate agonist, fedotozine had other properties that differentiated it from other opioid agonists, morphine (μ) and U50,488 (κ), including discriminative stimulus properties (21) and induction of contractions of guinea pig isolated intestinal smooth muscle cells, in contrast to the lack of effects of another κ agonist, U50,488 (22). κ-opiate receptors have been identified in myenteric neurons, suggesting that some κ agonists may affect intestinal motor function.

The κ-opiate agonist, fedotozine, which, in experimental animals reduced surrogates of visceral pain, also reduced visceral sensation without central effects in human studies, suggesting the effects were mediated peripherally (23–27). In this review, the general properties, pharmacology, efficacy and safety profile of a novel κ-opioid agonist, asimadoline, are summarized.

GENERAL PROPERTIES OF ASIMADOLINE

Asimadoline is a selective agonist of the κ-opioid receptor (28) which has low permeability across the blood brain barrier (29,30). Asimadoline appears to have relatively low distribution in the central nervous system, with central adverse reactions observed dose dependently at doses 10 times higher than the threshold doses for analgesic action. The analgesic effect is presumably mediated by opioid receptors which reduce the excitability of nociceptors on peripheral nerve endings. The antinociceptive effect can be antagonized by systemic naloxone-HCl, as well as by local infiltration with the κ-opioid-receptor antagonist, norbinaltorphimine. Centrally induced adverse events, such as dysphoria, sedation and increased diuresis, only occur at high doses (1–3 mg/kg), which are 50 to 600 times the threshold dosage for an analgesic effect in rats and 30 to 100 times the threshold dosage in mice.

Asimadoline Chemistry and Basic Pharmacology

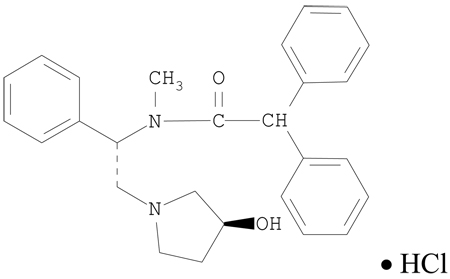

Asimadoline is N-[(1S)-2-[(3S)-3-hydroxypyrrolidin-1-yl]-1-phenylethyl]-N-methyl-2,2diphenylacetamide, hydrochloride.

Molecular formula: C27H30N2O2 × HCl Molecular weight (salt):451

Structural formula:

Receptor Binding Studies and in vitro Activity

Asimadoline was tested in various in vitro binding tests and ion channel screens. It had a high affinity only to κ-opioid receptors (IC50 1nM at human κ receptor) and a behaved as a potent (IC50 = 54.5 nmol/l) and full κ agonist in the rabbit vas deferens model. The action of asimadoline in the latter model was inhibited competitively by the nonselective opiate antagonist, naloxone, 0.3 µmol/l.

The IC50 for asimadoline binding to μ-opioid receptors was 3 µmol/l and to δ-opioid receptors was 0.7 µmol/l. The IC50 values for D1, D2, kainate, σ, PCP/NMDA, H1, α1, α2, M1/M2, glycine, 5HT1A, 5HT1C, 5HT1D, 5HT2, 5HT3, AMPA and kainate/AMPA receptors were all >10 µmol/l, suggesting no relevant antihistaminergic, antiserotonergic or anticholinergic effects.

At high concentrations, asimadoline demonstrated spasmolytic action against 400 µmol/l barium chloride in the rat duodenum (IC50 4.2 µmol/l), suggesting that asimadoline may block the direct stimulant effects of barium on smooth muscle through mechanisms that are not identified; however, it is possible that, at such high concentrations, the drug is not specific for κ receptors. Similarly, high concentrations of asimadoline inhibit spontaneous contractions of the rat uterus (IC50 12.7 µmol/l), and the mechanisms are unclear.

Pharmacokinetic Data in Animals

The absorption rate following oral administration is 80% in rats and >90% in dogs and monkeys. The plasma protein binding is 95–97%. Bioavailability is markedly lower, owing to a distinct first-pass metabolism: 20%, 14%, and 6% respectively in dogs, rats and monkeys. Following administration of 14C-asimadoline, there is no significant concentration in liver and kidneys, no significant penetration of the blood-brain barrier, and plasma elimination half-lives are less than one hour.

The metabolism of asimadoline is rapid and appears similar in animals and man; the major metabolite in plasma and in bile of rats and dogs is the glucuronide of asimadoline. In man, the long half-life of radioactivity of ~80 hours is almost exclusively accounted for by the glucuronide. There are also at least 10 Phase 1 metabolites (mainly products of aromatic hydroxylation and subsequent conjugation and of oxidative opening of the 3-hydroxypyrrolidine ring.) in urine and feces. CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 are involved in the formation of phase 1 metabolites. A drug-drug interaction study in humans showed that ketoconazole (CYP3A4 inhibitor) led to only a 2- to 3-fold increase in Cmax and area under the plasma concentration time curve (AUC)τ of asimadoline. There is no influence of the CYP2D6 genotype (extensive versus poor metabolizers) on asimadoline pharmacokinetics. Asimadoline had no inhibitory effect on CYP2A6, CYP2E1, CYP1A2, CYP2C9, and CYP2C19 activities in vitro using human microsomes. In general, asimadoline is unlikely to decrease clearance of co-administered substrates of CYP2D6 and CYP3A4.

Excretion is primarily fecal in the form of metabolites. After 48 hours from administration of radiolabeled asimadoline, the highest concentrations were observed in liver and kidneys (50 and 9 times the plasma concentrations, respectively); this increased concentration in the liver may reflect enterohepatic circulation of radioactive constituents.

Preclinical Pharmacology of Asimadoline

There is a lack of cross-tolerance in rats between antinociceptive effects of systemic morphine and asimadoline, suggesting that there may be less potential for tolerance to asimadoline than to morphine (31). These studies also showed that neurotrophic (somatic) pain due to chronic constriction injury in rats may respond to relatively small doses of the peripherally-selective κ agonist (31). Asimadoline's access to the brain is limited by the action of the P-glycoprotein (P-gp) in the blood brain barrier; in contrast, the intestinal P-gp barrier does not prevent intestinal uptake (32).

Kappa-opioid receptors modulate visceral sensation conveyed by vagal afferents from the stomach (33). Kappa-opioid receptors are up-regulated in the presence of colonic inflammation, and the mechanical and thermal sensitivity of polymodal pelvic nerve afferent fibers innervating the rat colon can be inhibited by intracolonic instillation of asimadoline (34,35), which suggests the medication is active peripherally. There is evidence that asimadoline may exert actions unrelated to the κ-opioid receptor cloned in the central nervous system, and that this site is localized in the colon. The evidence for a separate peripheral κ-opioid receptor is supported by the dose-dependent attenuation of responses of pelvic nerve afferent fibers to noxious colonic distension by asimadoline in rats in which antisense oligodeoxynucleotide (ODN), specifically knocked down the rat κ-opioid receptor cloned in the CNS. These data suggested the existence of a novel, peripheral κ-opioid-like receptor localized in the colon (36).

There is evidence that arylacetamide κ-opioid receptor agonists non-selectively inhibit voltage-evoked sodium currents in a manner similar to local anesthetics by enhancing closed-state inactivation and induction of use-dependent block (37). Asimadoline has affinity to sodium and L type Ca2+ ion channels at IC50 concentrations 150 to 800 fold the IC50 for the κ receptors (38).

There is also evidence that κ-opioid agonists activate ion channels such as mitochondrial K(ATP) channels (39) and G protein-activated inwardly rectifying K+ channels (GIRK, also known as Kir3 (40,41). However, there is no evidence in the literature that the effects of κ-opioid agonists affect enteric neurons.

Asimadoline strongly inhibited transient Ca2+-dependent Cl− secretion, activated by the muscarinic receptor agonist, carbachol (100 µM), or the purinergic agonist, ATP (100 µM), in Ussing chamber experiments using rat colonic mucosa (42). This suggests a possible effect of asimadoline on inhibiting fluid and electrolyte secretion in diarrheal diseases.

Asimadoline has peripheral anti-inflammatory actions that are partly mediated through increase in joint fluid substance P levels (43); this effect was more prominent in arthritic female rats than male rats (44). Asimadoline was effective in attenuating joint damage in Freund's adjuvant-induced arthritis in rats and exhibited analgesic effects on mechanical nociceptive thresholds (45). The role of such anti-inflammatory actions in visceral sensation is unclear.

Visceral Sensation in Animal Models in vivo and κ-Opioid Agents

Together with several other central and peripheral κ-opioid agonists, asimadoline was tested in a colonic distension model in rats under normal and hyperalgesic conditions (34,46,47). κ-opioid agonists significantly attenuate visceral nociception. The antinociceptive effect of κ-opioid agonists is enhanced if acute or chronic hypersensitivity has been induced, in contrast to effects of μ- or δ-opioid agents which tend not to be associated with altered antinociceptive action in the presence of hypersensitivity (46,47).

It has also been shown that action of asimadoline takes place at the peripheral nerve ending: electrophysiological signals conducted directly from the transmitting nerve fibers are inhibited by administration of asimadoline and fedotozine (34). Therefore, central κ-opioid activity is not required for efficacy, and the potential for unpleasant side effects due to central κ-opioid agonist activity (such as dysphoria and hallucinations) can be avoided with the peripherally-acting asimadoline which shows low permeation across the blood-brain barrier. The effect of asimadoline is blocked by high doses of naloxone (which are not specific for any single type of opioid receptor), confirming that the effect is mediated through opioid receptors (34).

Toxicological Effects in Animal Species

There was low potential for systemic toxicity following single oral and intraperitoneal administration to rats and mice. Asimadoline was not teratogenic in rats and rabbits at doses of up to 125 and 8 mg/kg, respectively, and not mutagenic in four mutagenicity tests.

Rats tolerated oral administration of 15 mg/kg body weight daily over a period of 4 weeks and 2.5 mg/kg over 26 weeks without any toxicologically relevant effects. Higher doses led to alterations in liver, thymus and adrenal and thyroid glands. Beagle dogs tolerated 2.5 mg/kg body weight daily over a period of 4 weeks and 0.5 mg/kg over 26 weeks without any changes. Higher doses resulted in reversible cellular alterations in liver, kidneys and male reproductive organs.

Human Pharmacokinetics

Human pharmacological studies showed a good absorption of doses of 2.5 to 15 mg of asimadoline administered orally. Maximum plasma concentrations were determined from 0.5 hour to 2 hours after administration; Cmax after 5 mg was approximately 80–120 ng/ml or 0.2 µmol/l. The clinically relevant half-life after single administration was calculated to be about 5.5 hours. After repeated oral administration of 2.5 mg of asimadoline once daily or b.i.d., for one week, the terminal elimination half-life was approximately 15 – 20 hours. Steady state was reached within three days for both once daily and b.i.d. dose regimens. The relative bioavailability of oral administration (based on the extent of absorption) was slightly increased after ingestion of food as compared to fasting state. Cmax and terminal half-life were not influenced by ingestion of food. The absolute bioavailability in humans is estimated to be 40–50%.

Effects on Somatic Pain in Humans

In studies of post-dental extraction pain, asimadoline shows a bell-shaped, dose-response curve in the range of 0.1 to 2.5 mg, with highest efficacy at 0.15 and 0.5 mg doses. The 5 mg dose was associated with no relief of pain. In humans, asimadoline, 10 mg p.o., tended to be associated with increased pain after knee surgery, possibly through an NMDA-induced hyperalgesic and proinflammatory effect (48). These data suggest that high doses (10 mg) are unlikely to be beneficial in the treatment of pain in humans.

Human Safety Data

Several placebo-controlled studies and open studies have been performed in the Phase II programs in somatic pain, osteoarthritis and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Asimadoline safety has been tested in more than 1,100 subjects at up to 15 mg as a single daily dose and up to 10 mg daily over 8 weeks of continuous dosing. As a result of safety, pharmacodynamic and clinical trial data, the target dose for asimadoline in treatment of functional gastrointestinal disorders is in the 0.5 to 1.0 mg, b.i.d. range. It is worth noting, however, that higher doses have been tested in human studies involving the gastrointestinal tract; thus, 1.5 mg, b.i.d., was tested in pharmacodynamic studies, and 11 participants in a study of post-operative ileus received asimadoline, 3.0 mg, b.i.d., for up to 11 doses.

Single and multiple doses, up to 2.5 mg per day, were very well tolerated. Single and multiple oral doses, up to 5 mg, were well tolerated; at doses of 10 and 15 mg, mild sedation and polyuria were observed, consistent with the known κ-opiate actions that cause aquaresis (49–51). Multiple doses of 2.5 mg per day were very well tolerated; multiple doses of 2.5 mg twice daily showed mild tiredness and polyuria in some subjects.

At 10 mg per day, nausea and vomiting were observed. No change in bowel function or effects on ECG, laboratory, and endocrine parameters were detected at any dose. No symptoms suggestive of withdrawal phenomena were reported by patients after eight weeks of treatment with up to 10 mg daily.

Serious adverse events were not commonly seen during the asimadoline development program and, for the most part, those that occurred were thought to be unrelated to the drug.

Human Pharmacodynamic Studies

a. Visceral sensation and gastrointestinal motor functions

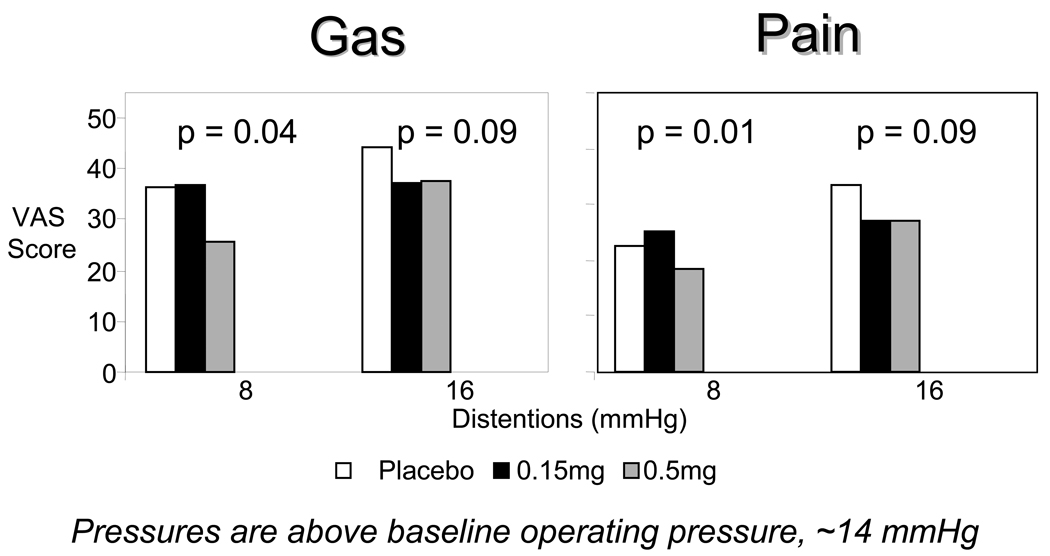

were tested in healthy volunteers (52) in a randomized, double-blind study of 0.15, 0.5, or 1.5 mg asimadoline or placebo orally, twice a day for 9 days. Asimadoline increased nutrient drink intake and decreased colonic tone during fasting without affecting postprandial colonic contraction, compliance or gastrointestinal or colonic transit. Gas and pain sensation ratings in response to colonic distention were decreased with asimadoline, 0.5 mg, at low levels (8 mmHg above operating pressure) of distention, not at higher levels of distention. In contrast, asimadoline, 1.5 mg, increased gas scores at 16 mmHg distention and pain scores at 8 and 16 mmHg distensions, not at higher levels of distention. The mechanism for this increased sensation with higher doses of asimadoline is unclear; however, it is consistent with the paradoxical observation of increased pain with higher doses observed in somatic pain trials that involved single daily doses of up to 10 mg/day for 8 weeks (38).

b. Satiation volume, postprandial symptoms and gastric volumes in healthy volunteers

Single administrations of asimadoline, 0.5 or 1.5 mg, and placebo 1 hour prior to testing were assessed in a randomized, double-blind fashion using the volume of Ensure® to achieve full satiation and postprandial symptoms 30 minutes after meal, and gastric volume (fasting and postprandial) measured by 99mTc-SPECT imaging (53). Compared to placebo, asimadoline, 0.5 mg, decreased postprandial fullness without affecting the volume ingested at full satiation. On the other hand, asimadoline, 1.5 mg, decreased satiation during meal, allowing increased volumes of nutrient drink to be ingested and somewhat decreased postprandial fullness (p=0.067), despite the higher volumes ingested. There was a significant treatment-gender interaction in the effect of asimadoline on gastric volumes, with asimadoline, 0.5 mg (but not 1.5 mg), being associated with increased fasting and postprandial gastric volumes in females. The effect of asimadoline on gastric volume did not explain the effect observed on satiation volume or postprandial fullness. Overall, the data suggested that single oral administration of asimadoline decreases satiation and postprandial fullness in humans, independently of its effects on gastric volume.

c. Colonic sensation in patients with IBS

In 20 patients with IBS and evidence of visceral hypersensitivity shown by a pain threshold of <32 mmHg during colonic distension (54), the effect of a single dose of asimadoline, 0.5 mg, was compared to placebo in a randomized, crossover fashion. While pain and other sensation thresholds were not significantly altered, area under the curve of intensity ratings of pain were lower with asimadoline. This finding supported the development of a trial to assess the effect of asimadoline for pain episodes in patients with IBS (discussed below).

Clinical Trials of Asimadoline in Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders

Functional dyspepsia

To evaluate the effects of asimadoline on satiation volume and post-challenge symptoms (55), 40 patients fulfilling Rome II criteria for functional dyspepsia were randomized to a double-blind, parallel-group design trial that evaluated gastric satiation and symptoms before and after 8 weeks of asimadoline, 0.5 mg or 1.0 mg, or placebo, b.i.d. Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS) and Nepean Dyspepsia Index (NDI) were used to assess symptoms during 8 weeks of treatment. Asimadoline had no significant effect on maximum tolerated volume or aggregate symptom score with nutrient drink challenge. There was also no significant effect on the mean of the total daily symptom severity score compared to placebo. However, assessment of efficacy in the intent to treat population was somewhat compromised by a substantial number of patients not meeting study inclusion criteria with insufficient baseline scores. In fact, a sub-analysis of patients with higher postprandial fullness scores showed that, asimadoline, 0.5 mg, significantly increased the maximum tolerated volume compared to placebo. This information suggests that the medication should be tested in future trials in a subgroup of functional dyspepsia patients whose symptoms are consistent with the postprandial distress syndrome and fulfill required inclusion criteria at baseline.

Irritable bowel syndrome

a. On-demand asimadoline in females with irritable bowel syndrome (56)

To compare the effects of asimadoline and placebo on episodes of abdominal pain in patients with IBS, 100 female patients with IBS were randomized (3:2 ratio) to receive asimadoline, up to 1 mg four times daily, or placebo for 4 weeks under double blind. Following a 2-week run–in period, pain was scored by daily diary using a 100 mm visual analog scale. During pain episodes, patients recorded the pain severity, took study medication, and recorded pain score 2 hours later. The primary endpoint was the average reduction in pain severity score 2 hours after treatment. The average pain reduction 2 hours post-treatment was not significantly different between the groups. Post-hoc analyses suggested asimadoline was effective in IBS-mixed, but pain rating was somewhat worse in diarrhea-predominant IBS. Anxiety score was modestly reduced by asimadoline. No significant adverse effects were noted. Thus, an on-demand dosing schedule of asimadoline was not effective in reducing severity of abdominal pain in IBS.

b. Twelve week chronic dosing of asimadoline in the treatment of patients with IBS

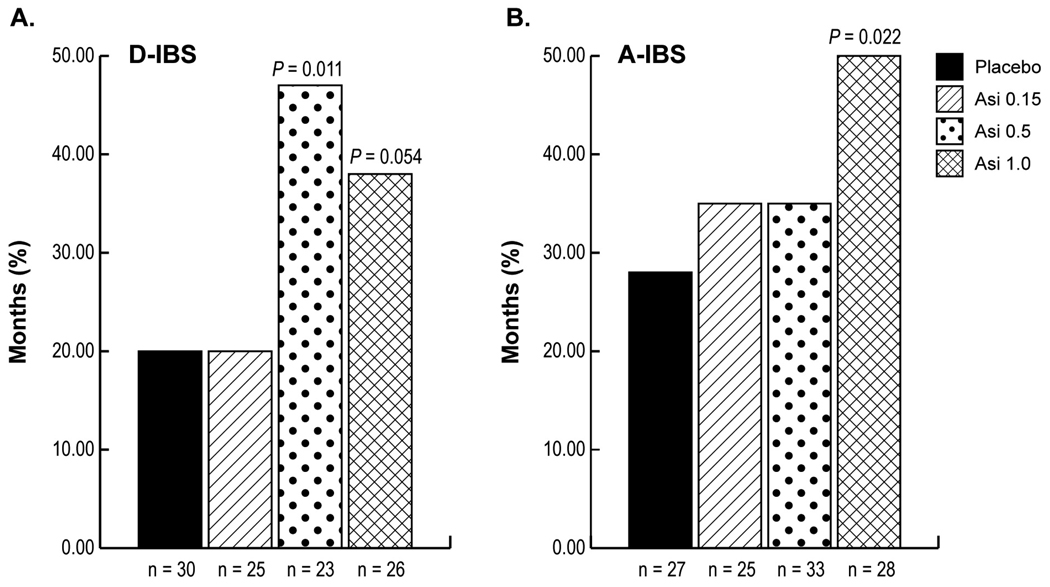

In a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial (57), the effects of asimadoline, 0.15, 0.5, or 1.0 mg, or placebo, b.i.d. for 12 weeks were evaluated in 596 patients with IBS. The primary efficacy measure was number of months of adequate relief of IBS pain or discomfort. There was no significant treatment effect in the entire IBS study population. However, in diarrhea-predominant IBS (D-IBS) patients with at least baseline moderate pain (score 2 or above on a 0–4 scale), asimadoline (0.5 mg) produced significant improvement in the total number of months with adequate relief of IBS pain or discomfort and several other secondary endpoints, including adequate relief of IBS symptoms, pain scores, pain free days, urgency, and stool frequency. In patients with alternating bowel function in IBS, significant improvement was also observed in adequate relief endpoints with 1.0 mg of asimadoline. Asimadoline was well tolerated. These data suggest that chronically dosed asimadoline warrants further evaluation as a treatment for IBS, probably in those with diarrhea or alternating bowel function.

Adverse Events Reported in Clinical Trials

At the target doses (0.5 or 1 mg, b.i.d.) intended for use in patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders, there were no serious clinical or laboratory adverse events in multiple clinical trials. Table I summarizes the cumulative safety of asimadoline from several clinical trials involving somatic pain and visceral pain syndromes. It is worth noting that symptoms like polyuria with high dose asimadoline suggest aquaresis, an effect of κ-opioid agonists that is associated with increased serum prolactin (58,59), possibly mediated through inhibition of dopaminergic tuberoinfundibular dopaminergic neurons (60) which are outside the blood brain barrier.

TABLE I.

Cumulative Safety of Asimadoline from Clinical Trials* Involving Somatic Pain and Visceral Pain Syndromes

| Adverse Event | Placebo | 0.15–2.0mg/day | 2.5–6.0mg/day | 7.5–15.0mg/day |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any Event | 105/224 (47%) | 57/171 (33%) | 139/248 (56%) | 115/167 (69%) |

| Headache | 18 (8%) | 9 (5%) | 56 (23%) | 35 (21%) |

| Dizziness | 9 (4%) | 5 (3%) | 19 (8%) | 25 (15%) |

| Polyuria | 4 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 10 (4%) | 17 (10%) |

| Fatigue | 5 (2%) | 2 (1%) | 14 (6%) | 14 (8%) |

| Nausea | 8 (4%) | 6 (4%) | 7 (3%) | 15 (9%) |

| Somnolence | 1 (0%) | 2 (1%) | 19 (8%) | 9 (5%) |

| Thirst | 15 (7%) | 8 (5%) | 6 (2%) | 6 (4%) |

| Vomiting | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 8 (5%) |

| Diarrhea | 9 (4%) | 3 (2%) | 5 (2%) | 8 (5%) |

| Constipation | 1 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (1%) | 6 (4%) |

Includes single-dose and multiple-dose studies; reported by total daily dose.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

Asimadoline is a selective, peripherally active κ-opioid agonist with effects on visceral sensation and some evidence of efficacy in subgroups of patients with functional dyspepsia and postprandial distress, as well as IBS patients with diarrhea or alternating bowel function. It appears safe and, at the doses that appear efficacious in clinical trials, it does not cause significant adverse effects, such as aquaresis. Drug interactions are unlikely to be significant, and the initial pharmacodynamics and Phase II trials suggest that, with further study, it may be a significant addition to the therapeutic armamentarium for pain and discomfort in patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders.

Figure 1.

Gas and pain VAS scores in response to colonic distentions. Figure shows VAS scores for gas (A) and pain (B) at each distention pressure during random colonic phasic distention. Asimadoline decreased gas and pain perception at low distention pressures but this effect was not observed at higher levels of distention.

Figure 2.

Effects of asimadoline on adequate relief of IBS pain or discomfort in patients with at least moderate pain at baseline. Diarrhea-predominant (D-IBS) patients are shown in panel A and alternators (A-IBS) in panel B (reproduced from ref. 57).

Acknowledgements

Dr. Camilleri is supported in part by grants RO1-DK54681 and K24-DK02638 from National Institutes of Health. The author thanks Tioga Pharmaceuticals for providing summary data on safety and Cindy Stanislav for excellent secretarial assistance.

Support: Dr. Camilleri conducted four research studies funded by the previous (Merck KGAa, Darmstadt, Germany) and current (Tioga Pharmaceuticals Inc., San Diego, CA) owners of asimadoline. He has served as a consultant to Tioga after completing and publishing all research studies. His personal remuneration for this activity is below the federal threshold for significant financial conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Drossman DA, Li Z, Andruzzi E, et al. U.S. householder survey of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Prevalence, sociodemography, and health impact. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1569–1580. doi: 10.1007/BF01303162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Talley NJ, Van Zinsmeister AR, Dyke C, Melton LJ., III Epidemiology of colonic symptoms and the irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:927–934. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90717-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Camilleri M. Mechanisms in IBS: something old, something new, something borrowed…. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2005;17:311–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2004.00632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drossman DA, Whitehead WE, Camilleri M. Irritable bowel syndrome: a technical review for practice guidelines. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:2120–2137. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.agast972120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andresen V, Camilleri M. Irritable bowel syndrome: recent and novel therapeutic approaches. Drugs. 2006;66:1073–1088. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200666080-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andresen V, Camilleri M. Challenges in drug development for functional gastro-intestinal disorders: Part II: Visceral pain. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18:354–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2006.00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Satoh M, Minami M. Molecular pharmacology of the opioid receptors. Pharmacol Ther. 1995;68:343–364. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(95)02011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stein C. The control of pain in peripheral tissue by opioids. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1685–1690. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199506223322506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harada Y, Nishioka K, Kitahata LM, Nakatani K, Collins JG. Contrasting actions of intrathecal U50,488H, morphine, or [D-Pen2, D-Pen5] enkephalin or intravenous U50,488H on the visceromotor response to colorectal distension in the rat. Anesthesiology. 1995;83:336–343. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199508000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Danzebrink RM, Green SA, Gebhart GF. Spinal mu and delta, but not kappa, opioid-receptor agonists attenuate responses to noxious colorectal distension in the rat. Pain. 1995;63:39–47. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)00275-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diop L, Riviere PJ, Pascaud X, Junien JL. Peripheral kappa-opioid receptors mediate the antinociceptive effect of fedotozine (correction of fetodozine) on the duodenal pain reflex in rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994;271:65–71. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90265-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sproule BA, Busto UE, Somer G, Romach MK, Sellers EM. Characteristics of dependent and nondependent regular users of codeine. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19:367–372. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199908000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Schepper HU, Cremonini F, Park M-I, Camilleri M. Opioids and the gut: pharmacology and current clinical experience. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16:383–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2004.00513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bagnol D, Mansour A, Akil H, Watson SJ. Cellular localization and distribution of the cloned mu and kappa opioid receptors in rat gastrointestinal tract. Neuroscience. 1997;81:579–591. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00227-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fickel J, Bagnol D, Watson SJ, Akil H. Opioid receptor expression in the rat gastrointestinal tract: a quantitative study with comparison to the brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1997;46:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(96)00266-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riviere PJ, Pascaud X, Chevalier E, Le Gallou B, Junien JL. Fedotozine reverses ileus induced by surgery or peritonitis: action at peripheral kappa-opioid receptors. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:724–731. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)91007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Winter BY, Boeckxstaens GE, De Man JG, Moreels TG, Herman AG, Pelckmans PA. Effects of mu-and kappa-opioid receptors on postoperative ileus in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;339:63–67. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01345-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salet GAM, Heyligers JMM, Lautenschutz JM, van Lindert ACM, Heintz APM, Boon TA. The effects of fedotozine on digestive symptoms following abdominal surgery. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:A682. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonaz B, Riviere PJ, Sinniger V, Pascaud X, Junien JL, Fournet J, Feuerstein Fedotozine, a kappa-opioid agonist, prevents spinal and supra-spinal Fos expression induced by a noxious visceral stimulus in the rat. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2000;12:135–147. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.2000.00188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ness TJ. Kappa opioid receptor agonists differentially inhibit two classes of rat spinal neurons excited by colorectal distention. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:388–394. doi: 10.1053/gast.1999.0029900388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Broqua P, Wettstein JG, Rocher MN, Riviere PJ, Dahl SG. The discriminative stimulus properties of U50,488 and morphine are not shared by fedotozine. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 1998;8:261–266. doi: 10.1016/s0924-977x(97)00084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coruzzi G, Morini G, Coppelli G, Bertaccini G. The contractile effect of fedotozine on guinea pig isolated intestinal cells is not mediated by kappa opioid receptors. Pharmacology. 1998;56:281–284. doi: 10.1159/000028210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coffin B, Bouhassira D, Chollet R, Fraitag B, De Meynard C, Geneve J, et al. Effect of the kappa agonist fedotozine on perception of gastric distension in healthy humans. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1996;10:919–925. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1996.109280000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Delvaux M, Louvel D, Lagier E, Scherrer B, Abitbol JL, Frexinos J. The kappa agonist fedotozine relieves hypersensitivity to colonic distention in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:38–45. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70226-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dapoigny M, Abitbol JL, Fraitag B. Efficacy of peripheral kappa agonist fedotozine versus placebo in treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. A multicenter dose-response study. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:2244–2249. doi: 10.1007/BF02209014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Read NW, Abitbol JL, Bardhan KD, Whorwell PJ, Fraitag B. Efficacy and safety of the peripheral kappa agonist fedotozine versus placebo in the treatment of functional dyspepsia. Gut. 1997;41:664–668. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.5.664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fraitag B, Homerin M, Hecketsweiler P. Double-blind dose-response multicenter comparison of fedotozine and placebo in treatment of nonulcer dyspepsia. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39:1072–1077. doi: 10.1007/BF02087560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gottschlich R, Krug M, Barber A, Devant RM. kappa-Opioid activity of the four stereoisomers of the peripherally selective kappa-agonists, EMD 60,400 and EMD 61,753. Chirality. 1994;6:685–689. doi: 10.1002/chir.530060814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barber A, Bartoszyk GD, Bender HM, Gottschlich R, Greiner HE, Harting J, et al. A pharmacological profile of the novel, peripherally-selective kappa-opioid receptor agonist, EMD 61753. Br J Pharmacol. 1994;113:1317–1327. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb17142.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bender HM, Dasenbrock J. Brain concentrations of asimadoline in mice: the influence of coadministration of various P-glycoprotein substrates. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1998;36:76–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walker J, Catheline G, Guilbaud G, Kayser V. Lack of cross-tolerance between the antinociceptive effects of systemic morphine and asimadoline, a peripherally-selective kappa-opioid agonist, in CCI-neuropathic rats. Pain. 1999;83:509–516. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00158-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jonker JW, Wagenaar E, van Deemter L, Gottschlich R, Bender HM, Dasenbrock J, Schinkel AH. Role of blood-brain barrier P-glycoprotein in limiting brain accumulation and sedative side-effects of asimadoline, a peripherally acting analgaesic drug. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;127:43–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ozaki N, Sengupta JN, Gebhart GF. Differential effects of mu-, delta-, and kappa-opioid receptor agonists on mechanosensitive gastric vagal afferent fibers in the rat. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:2209–2216. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.4.2209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sengupta JN, Snider A, Su X, Gebhart GF. Effects of kappa opioids in the inflamed rat colon. Pain. 1999;79:175–185. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00175-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Su X, Julia V, Gebhart GF. Effects of intracolonic opioid receptor agonists on poly-modal pelvic nerve afferent fibers in the rat. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:963–970. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.2.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Joshi SK, Su X, Porreca F, Gebhart GF. Kappa-opioid receptor agonists modulate visceral nociception at a novel peripheral site of action. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5874–5879. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-15-05874.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joshi SK, Lamb K, Bielefeldt K, Gebhart GF. Arylacetamide kappa-opioid receptor agonists produce a tonic-and use-dependent block of tetrodotoxin-sensitive and-resistant sodium currents in colon sensory neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;307:367–372. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.052829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Asimadoline Investigator’s Brochure. Indications: Irritable bowel syndrome and postoperative ileus. Version 5.0. Tioga Pharmaceuticals; 2006. Jul 7, [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lishmanov AY, Maslov LN, Lasukova TV, Crawford D, Wong TM. Activation of kappa-opioid receptor as a method for prevention of ischemic and reperfusion arrhythmias: role of protein kinase C and K(ATP) channels. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2007;143:187–190. doi: 10.1007/s10517-007-0046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kobayashi T, Washiyama K, Ikeda K. Inhibition of G protein-activated inwardly rectifying K+ channels by ifenprodil. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:516–524. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marker CL, Luján R, Loh HH, Wickman K. Spinal G-protein-gated potassium channels contribute in a dose-dependent manner to the analgesic effect of mu-and delta-but not kappa-opioids. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3551–3559. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4899-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schreiber R, Bartoszyk GD, Kunzelmann K. The kappa-opioid receptor agonist asimadoline inhibits epithelial transport in mouse trachea and colon. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;503:185–190. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Binder W, Scott C, Walker JS. Involvement of substance P in the anti-inflammatory effects of the peripherally selective kappa-opioid asimadoline and the NK1 antagonist GR205171. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:2065–2072. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Binder W, Carmody J, Walker J. Effect of gender on anti-inflammatory and analgesic actions of two kappa-opioids. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;292:303–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Binder W, Walker JS. Effect of the peripherally selective kappa-opioid agonist, asimadoline, on adjuvant arthritis. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;124:647–654. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sengupta JN, Snider A, Su X, Gebhart GF. κ, but not μ or δ, opioids attenuate responses to distension of afferent nerve fibers innervating the rat colon. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:968–980. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(96)70064-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burton MB, Gebhart GF. Effects of kappa-opioid receptor agonists on responses to colorectal distension in rats with and without acute colonic inflammation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;285:707–715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Machelska H, Pfluger M, Weber W, Piranvisseh-Volk M, Daubert JD, Dehaven R, Stein C. Peripheral effects of the kappa-opioid agonist EMD 61753 on pain and inflammation in rats and humans. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;290:354–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bellissant E, Denolle T, Sinnassamy P, Bichet DG, Giudicelli JF, Lecoz F, Gandon JM, Allain H. Systemic and regional hemodynamic and biological effects of a new kappa-opioid agonist, niravoline, in healthy volunteers. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;278:232–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kramer HJ, Uhl W, Ladstetter B, Backer A. Influence of asimadoline, a new kappa-opioid receptor agonist, on tubular water absorption and vasopressin secretion in man. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;50:227–235. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2000.00256.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ko MC, Willmont KJ, Lee H, Flory GS, Woods JH. Ultra-long antagonism of kappa opioid agonist-induced diuresis by intracisternal nor-binaltorphimine in monkeys. Brain Res. 2003;982:38–44. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02938-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Delgado-Aros S, Chial HJ, Camilleri M, Szarka LA, Weber FT, Jacob J, Ferber I, McKinzie S, Burton DD, Zinsmeister AR. Effects of a kappa opioid agonist, asimadoline, on satiation and gastrointestinal motor and sensory functions in humans. Am J Physiol. 2003;284:G558–G566. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00360.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Delgado-Aros S, Chial HJ, Cremonini F, Ferber I, McKinzie S, Burton DD, Camilleri M. Effects of asimadoline, a kappa-opioid agonist, on satiation and postprandial symptoms in health. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:507–514. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Delvaux M, Beck A, Jacob J, Bouzamondo H, Weber FT, Frexinos J. Effect of asimadoline, a kappa opioid agonist, on pain induced by colonic distension in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:237–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Talley NJ, Choung RS, Camilleri M, Dierkhising RA, Zinsmeister AR. Asimadoline, a kappa-opioid agonist, and satiation in functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:1122–1131. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03676.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Szarka LA, Camilleri M, Burton D, Fox JC, McKinzie S, Stanislav T, Simonson J, Sullivan N, Zinsmeister AR. Efficacy of on-demand asimadoline, a peripheral kappa-opioid agonist, in females with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1268–1275. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mangel AW, Bornstein JD, Hamm LR, Buda J, Wang J, Irish W, Urso D. Clinical trial: asimadoline in the treatment of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharm Ther. 2008;28:239–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bart G, Schluger JH, Borg L, Ho A, Bidlack JM, Kreek MJ. Nalmefene induced elevation in serum prolactin in normal human volunteers: partial kappa opioid agonist activity? Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:2254–2262. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Goletiani NV, Mendelson JH, Sholar MB, Siegel AJ, Skupny A, Mello NK. Effects of nalbuphine on anterior pituitary and adrenal hormones and subjective responses in male cocaine abusers. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;86:667–677. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chesterfield M, Janik J, Murphree E, Lynn C, Schmidt E, Callahan P. Orphanin FQ/nociceptin is a physiological regulator of prolactin secretion in female rats. Endocrinology. 2006;147:5087–5093. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]