Abstract

Purpose

Nonhormonal treatment options have been investigated as treatments for hot flashes, a major clinical problem in many women. Starting in 2000, a series of 10 individual double-blind placebo-controlled studies has evaluated newer antidepressants and gabapentin for treating hot flashes. This current project was developed to conduct an individual patient pooled analysis of the data from these published clinical trials.

Patients and Methods

Individual patient data were collected from the various study investigators who published their study results between 2000 and 2007. Between-study heterogeneity for study characteristics and patient populations was tested via χ2 tests before a pooled analysis. The primary end point, the change in hot flash activity from baseline to week 4, for each agent was calculated via both weighted and unweighted approaches, using the size of the study as the weight. Basic summary statistics were produced for hot flash score and frequency using the following three statistics: raw change, percent reduction, and whether or not a 50% reduction was achieved.

Results

This study included seven trials of newer antidepressants and three trials of gabapentin. The optimal doses (defined by individual study results) of the newer antidepressants paroxetine, venlafaxine, fluoxetine, and sertraline decreased hot flash scores by 41%, 33%, 13%, and 3% to 18% compared with the corresponding placebo arms, respectively. The three gabapentin trials decreased hot flashes by 35% to 38% compared with the corresponding placebo arms.

Conclusion

Some newer antidepressants and gabapentin, within 4 weeks of therapy initiation, decrease hot flashes more than placebo.

INTRODUCTION

Hot flashes are a major problem for many women as they approach menopause.1 Estrogen reduces hot flashes, by approximately 80% to 90%.2–5 Nonetheless, over the last few years, there have been many concerns regarding the use of estrogen in menopausal women.2

In the 1990s, it was anecdotally recognized that patients receiving newer antidepressants (newer antidepressants are defined in this article as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors) seemed to have diminished hot flashes. The first published article regarding a pilot experience of this approach appeared in 1998,3 whereas the first results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial appeared in 2000.4 Since then, there have been multiple additional placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blinded clinical trials addressing the use of newer antidepressants for the treatment of hot flashes.4–12

In 2000, anecdotal experience with gabapentin, as a treatment for hot flashes, was published.13 The first report of a prospective pilot trial appeared in 2002,14 whereas the first results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial were published in 2003.15 Subsequently, reports from two additional double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trials have become available.16,17

In early 2005, results were available, at least in abstract form, for five clinical trials studying newer antidepressants and two clinical trials studying gabapentin, all of which were double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trials. At that time, discussions were begun with the primary authors of these trials to conduct an individual patient pooled analysis of these trial results. The primary goal of this project was to determine the effect size of the reduction in hot flash frequencies and hot flash scores for each pharmacologic agent and each category of agents (the different antidepressantsv the one antiseizure medication). In the interim, between the time this study concept was conceived and now, another meta-analysis regarding this subject was published.18 As will be discussed later in this report, the methodologies, the included studies, and the conclusions between that meta-analysis and the current one are different.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This project was approved by the Mayo Foundation Internal Review Board, as per US federal guidelines. In the spring of 2005, invitations were provided to the principal investigators of each of the known clinical trials that had addressed the utilization of a newer antidepressant or gabapentin, versus a placebo, in a prospective, randomized, double-blind clinical trial design. Subsequent to that time, additional clinical trials were published, and the primary authors of these clinical trials were also invited to participate in this endeavor. This effort resulted in the participation of all such known trials that used daily hot flash diary data and were published before January 2008.

Investigators invited to participate in this endeavor were asked to submit raw data containing their study's individual patient treatment assignment (placebov active agent), dose, and information regarding hot flash frequency and severity. Information submitted included individual patient data that were de-identified but were coded so as to allow for potential communication if clarification was necessary. The data were to include patient treatment assignment (placebov active agent) and dose. Investigators were asked to submit a SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) or SPSS (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) data set containing as many of the following demographic variables that were available in their data set: age, history of breast cancer, menopausal status (postmenopausalvperimenopausalvunknownvother), type of menopause (naturalv bilateral oophorectomy), race, and use of tamoxifen, raloxifene, or aromatase inhibitors.

The analysis was performed using aggregation of the patient-level data into pooled estimates of efficacy for each study according to the previously specified research hypothesis. Frequency and severity data were compiled to produce hot flash activity scores as per previous Mayo Clinic/North Central Cooperative Treatment Group studies.19 The hot flash severities were usually graded from 1 to 4, ranging from mild to very severe. For one of the studies,15 a 7-point hot flash severity scale was used, so this was translated into a 4-point scale by multiplying each individual data point by 4/7. The hot flash score was determined by multiplying the daily frequency times the average hot flash severity. For forest plot comparisons, 95% CIs and related two-samplet tests were constructed.

The primary analysis was the construction of an overall effect size for all agents, using the patient-level pooled data. An effect size was planned to be calculated as the difference in hot flash activity from the baseline week. Results were to be presented in terms of the percentage reduction from baseline. Basic summary statistics were produced for hot flash score and frequency using the following three statistics: raw change, percent reduction, and whether or not a 50% reduction was achieved. Relevant 95% CIs for the effect size were calculated and plotted on forest plots.

Tests for heterogeneity for study characteristics and patient populations were performed before combining data from the different studies. Regression models and random effects linear models were run on the hot flash activity data to control for age, breast cancer history, and tamoxifen usage.

Individual patient data underwent χ2 tests for variance and demographic heterogeneity before combining data from the different studies. Pooled effect sizes were obtained by using a random effects model for the raw data, where the individual studies were the random effects. The effect size for the percent decrease in hot flash scores from baseline to week 4 for each agent, which was the primary end point, was then calculated using the size of the sample as the weighting variable. The effect size was recalculated using an unweighted approach to test the sensitivity of the results relative to the influence of individual study sample sizes. The analytic methods used were consistent with those used in a recently published pooled analysis on the effectiveness of antidepressants for alleviating clinical depression.20

RESULTS

A total of 12 studies were considered for this pooled analysis.4–12,15–17 Nine of these studies involved newer antidepressants, and three involved gabapentin. Constructed funnel plots demonstrated that the studies were relatively consistent in their variability and indicated that the effect sizes observed were relatively consistent across sample sizes. Snedecor tests of variance heterogeneity of study results also supported this conclusion.

The analysis plans involved the use of a 1-week period to provide baseline week data for which the subsequent trial data could be compared. However, two of the trials9,10 that were considered for participation in this pooled analysis did not collect any baseline week data and thus could not be used. One of these two trials10 used day 1 of treatment as the baseline (E. Suvanto-Luukkonen personal communication, April 2007). The other trial9 did not claim to have baseline hot flash diary data and did not try to illustrate the use of baseline hot flash diary data. Thus, these two trials9,10 needed to be excluded from the formal pooled analysis presented here.

The data during the fourth treatment week were chosen to compare to the baseline week. These were available for all of the trials except for one.12 This trial, however, had data from the sixth treatment week available, so the week 6 data were used, instead, for this trial. Summary data of the 10 trials for patients who had baseline week data and data for the fourth treatment week (sixth treatment week for the one study) are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study Characteristics

| Agent and Study | No. of Patients in Current Analysis | Breast Cancer History (No. of patients) |

Tamoxifen (No. of patients) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Unknown | Yes | No | Unknown | ||

| Venlafaxine | |||||||

| Loprinzi et al4 | 191 | 191 | 0 | 0 | 134 | 57 | 0 |

| Fluoxetine | |||||||

| Loprinzi et al5 | 68 | 68 | 0 | 0 | 38 | 30 | 0 |

| Paroxetine | |||||||

| Stearns et al7 | 142 | 12 | 130 | 0 | 5 | 137 | 0 |

| Stearns et al6 | 117 | 97 | 20 | 0 | 69 | 40 | 8 |

| Sertraline | |||||||

| Kimmick et al8 | 49 | 49 | 0 | 0 | 49 | 0 | 0 |

| Gordon et al11 | 91 | 0 | 91 | 0 | 0 | 91 | 0 |

| Grady et al12 | 90 | 0 | 90 | 0 | 0 | 90 | 0 |

| Gabapentin | |||||||

| Pandya et al16 | 358 | 358 | 0 | 0 | 252 | 94 | 12 |

| Guttuso et al15 | 54 | 0 | 54 | 0 | 0 | 54 | 0 |

| Reddy et al17 | 38 | 0 | 38 | 0 | 0 | 38 | 0 |

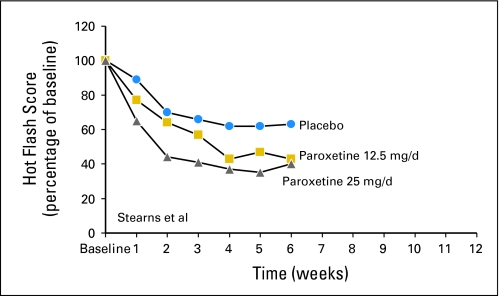

Basic summary statistics were produced for hot flash score and frequency using the following three statistics: raw change, percent reduction, and whether or not a 50% or greater reduction was achieved. Illustrations of individual study percent reduction from baseline results for the 10 studies are provided inFigure 1. These graphs are, at times, slightly different than what were presented in the individual study reports. One of the reasons for the differences is that the individual studies did not always show plots regarding percent changes from baseline. Rather, some showed absolute changes from baseline, which results in slightly different looking figures. Another reason, for one study,8 was that the previously published report used the mean hot flash score for all patients at the baseline time and at each of the follow-up times and compared the means to each other, as opposed to comparing each individual patient's values to each other and then illustrating the mean of these. The latter seems to be a better way to present the data because it compares all individual patient follow-up data to the baseline data for that individual. This way, if there is a differential dropout of patients (eg, patients with more baseline hot flashes being more likely to dropout), the results are not as skewed. Forest plots of these studies, comparing 4- to 6-week hot flash scores with baseline week scores, are provided inFigures 2 and 3. These figures illustrate that the drugs consistently reduced hot flashes more than did the placebos of each study. The mean hot flash score reduction seen in the combined placebo arms of these studies was 24%. The additional hot flash score reductions (vplacebos) were 33% for venlafaxine (75 mg/d),413% to 41% for paroxetine (10 to 25 mg/d),6,713% for fluoxetine (20 mg/d),59% to 18% for sertraline (50 mg/d),8,113% for sertraline (100 mg/d),12 and 35% to 38% for gabapentin (900 to 2,400 mg/d).15–17

Fig 1.

Individual study results. (A) Venlafaxine study results.4(B) Fluoxetine study results.5 (C) Paroxetine individual study results.6,7 (D) Sertraline individual study results.8,11,12 (E) Gabapentin individual study results.15–17

Fig 2.

Forest plots of hot flash reduction in newer antidepressant studies.

Fig 3.

Forest plots of hot flash reduction in gabapentin studies.

The pooled analysis exercise of calculating the effect size for the amount of decrease in hot flash scores from baseline to week 4 was redone using both weighted and unweighted approaches, using the size of the sample as the weighting variable. The weighted effect size was a reduction, on average, of 61.02%, with a standard deviation of 63.03%. The unweighted effect size was 58.13%, with a standard deviation of 61.11%. Hence, the weighting of the results by the size of the sample did not alter the basic finding with respect to hot flash score activity. The percentages of patients with at least a 50% reduction of hot flashes are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Patients With at Least a 50% Reduction of Hot Flashes in the Different Trials

| Agent, Study, and Dose (mg/d) | % of Active Arm Patients With at Least a 50% Reduction in Hot Flash Scores | % of Placebo Patients With at Least a 50% Reduction in Hot Flash Scores |

|---|---|---|

| Venlafaxine | ||

| Loprinzi et al4 | 30 | |

| 37.5 | 54 | |

| 75 | 70 | |

| 150 | 62 | |

| Fluoxetine | ||

| Loprinzi et al5 | 52 | |

| 20 | 70 | |

| Paroxetine | ||

| Stearns et al7 | 49 | |

| 12.5 | 50 | |

| 25 | 68 | |

| Stearns et al6 | 33; 57* | |

| 10 | 70 | |

| 20 | 76 | |

| Sertraline | ||

| Kimmick et al8 | 38 | |

| 50 | 50 | |

| Gordon et al11 | 21 | |

| 50 | 40 | |

| Grady et al12 | 41 | |

| 100 | 56 | |

| Gabapentin | ||

| Pandya et al16 | 27 | |

| 300 | 46 | |

| 900 | 56 | |

| Guttuso et al15 | 38 | |

| 900 | 63 | |

| Reddy et al17 | 47 | |

| 2,400 | 84 | |

| Combined placebo studies | 37 |

There were two different placebo arms in this trial.

The raw change from baseline data is similar to that seen with the percent reduction from baseline data. The results from all of the same analyses of these studies looking at hot flash frequency data, as opposed to hot flash score data, are virtually superimposable to what has already been presented earlier.

Linear regression models for the percentage reduction in hot flash activity was carried out to include the potential covariate influences of breast cancer history, tamoxifen use, race, and age. None of these variables significantly impacted the basic results of the efficacy of various agents in reducing hot flash activity.

On the basis of evidence that suggested that the efficacy of paroxetine might be related to its ability to prevent the conversion of tamoxifen to endoxifen,21 patients receiving paroxetine, who were not receiving concomitant tamoxifen, were examined.Figure 4 illustrates that the benefit of paroxetine on decreasing hot flashes is apparent in patients who were not receiving tamoxifen (P = .002, by Kruskal-Wallis test comparing the combined paroxetine arms with the placebo arm).

Fig 4.

Hot flash score data for paroxetine patients who were not receiving tamoxifen.7

DISCUSSION

This individual patient pooled analysis supports that newer antidepressants and gabapentin decrease hot flashes. With regard to the newer antidepressants, it seems that venlafaxine and paroxetine are more effective than the studied doses of sertraline and fluoxetine.

It has become apparent in recent years that paroxetine can inhibit the conversion of tamoxifen to its active metabolite, endoxifen.22 In addition, it has also become apparent that endoxifen may be responsible for causing tamoxifen-associated hot flashes.21 Therefore, part of the efficacy of paroxetine for treating hot flashes in patients receiving tamoxifen may be related to its inhibition of the metabolism of this drug. Nonetheless, the efficacy of paroxetine against hot flashes is demonstrated in women who are not taking tamoxifen (Fig 4), showing that its efficacy against hot flashes is related to more than just its ability to interfere with the metabolism of tamoxifen. Another review has demonstrated that hot flash therapies seem to be equally effective in women who have a history of breast cancer versus those who do not and also in women on tamoxifen versus those who are not.23

It has been reported in another meta-analysis18 that two placebo-controlled, double-blind trials that looked at longer durations of newer antidepressants9,10 had negative results, being unable to demonstrate that the three studied antidepressants in these two trials (venlafaxine, citalopram, and fluoxetine) were better than were placebos in terms of daily hot flash score changes. However, as noted earlier, neither of these trials had baseline data in patients, before they received study medications. In one of these trials, the patient diary information was presented starting with the first week of therapy, with no baseline hot flash diary information being provided.9 In the other trial,10 the first day of therapy was used as the baseline hot flash data. This is problematic because the effect of antidepressants on hot flashes is quite rapid. If week 1 ofFigure 1A is examined, it can be observed that the hot flash reduction with venlafaxine 37.5 mg/d (all three treatment arms received 37.5 mg/d for the first study week) was as low as that achieved with the 37.5 mg/d arm 4 weeks later. When the first day of therapy in the initial venlafaxine trial is compared with the baseline week data, there is a 30% decrease in hot flash score reduction seen on that day. In addition, if data from the Evans et al9 trial are examined, the one piece of data that was collected at baseline and then monthly after treatment was started (that being from a prospectively administered questionnaire inquiring about how significantly hot flashes interfered with patients' daily living) does illustrate a significantly positive treatment effect (Fig 1 in that report), with a 51% improvement from baseline with venlafaxine versus only a 15% improvement with placebo. It is noteworthy that the conclusion section of the abstract for this article9 did surmise that venlafaxine did significantly decrease hot flashes. Further details regarding these two trials have been published.24

Gabapentin, at doses ranging from 900 to 2,400 mg/d, also significantly decreased hot flashes, as illustrated in three published trials.15–17 Relatively similar results are seen in these three trials, at least in terms of the improvement seen on the active treatment arms versus the placebo arms. Although the forest plot (Fig 3) suggests that a 300 mg/d dose of gabapentin is not as efficacious as a 900 mg/d dose, the 2,400 mg/d dose efficacy looks similar to the 900 mg/d dose. Examining individual trials, the two trials that evaluated 900 mg/d of gabapentin reported that hot flashes were decreased by 45% to 50% (Fig 1E).15,16 In the individual patient trial that studied 2,400 mg/d, hot flashes were reported to be reduced by approximately 80% (Fig 1E).17 In this last trial, however, there was a much more substantial reduction of hot flashes in the placebo arm compared with the other two trials (> 40% at 4 weeks), thus leading to the similar-appearing results in the forest plot. In addition, the trial looking at gabapentin 2,400 mg/d was a relatively small trial, with only 20 patients per study arm. Thus, the dose response question, with regard to higher doses of gabapentin, needs to be further investigated. A recently completed trial in men with prostate cancer also has evaluated doses of gabapentin at 900 mg/d. This trial shows similar efficacy to the trials seen in women, with a 45% reduction in hot flashes in the men with prostate cancer.25

The relative efficacy of gabapentin, compared with newer antidepressants, can be estimated by looking at the forest plots of these different agents (Figs 2 and 3). In all, the efficacy seems to be relatively similar.

It is worth comparing the results of the current trial to another meta-analysis18 of nonhormonal hot flash therapies that was published after the current pooled analysis was initiated. This previously published meta-analysis looked at six trials that evaluated newer antidepressants.9,4-7,10 Two of these trials, however, were excluded from the present analysis because it became apparent that there were no baseline data for these trials when individual patient results were studied.9,10 In addition to excluding these two trials, the current meta-analysis added three randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials that evaluated newer antidepressants for hot flashes.8,11,12 The previous meta-analysis18 looked at two trials evaluating gabapentin.15,16 The current trial adds a third gabapentin study.17

A major difference in methodology between the previous meta-analysis and the current one relates to the way the analyses were performed. The current trial evaluated individual patient data from all of the involved studies. In contrast, the previous meta-analysis used data from completed published trials, as opposed to individual patient data. The use of individual patient data in the current trial allowed for the ability to exclude two trials for which baseline data were not available. In addition, it provided the ability to illustrate all of the individual results from the involved trials, using identical statistical methodology applied to the raw data from each trial. For these reasons, the conclusions from this current pooled analysis are more stout than the more tepid conclusion regarding the utility of newer antidepressants in the previous meta-analyses.18 Lastly, data from three additional randomized, double-blind, clinical trials that have recently become available further support that newer antidepressants do moderately decrease hot flashes.26–28

In conclusion, this current pooled analysis does support that both newer antidepressants and gabapentin are useful for relieving hot flashes in women. It suggests, however, that the efficacy of newer antidepressants is not identical between the studied agents, with venlafaxine and paroxetine appearing to decrease hot flashes more than sertraline or fluoxetine. Newer antidepressants and gabapentin, admittedly, do not decrease hot flashes as much as hormonal agents, and they, like virtually all drugs, do have some toxicities associated with them. Nonetheless, they are reasonable treatments to offer to patients with bothersome hot flashes. Further research regarding these agents will hopefully define the utility of other antidepressants, better delineate whether there is non–cross resistance between these drugs, better determine the optimal dose of gabapentin, and determine whether pregabalin is helpful for reducing hot flashes.

Footnotes

Supported by the North Central Cancer Treatment Group (Public Health Service Grant No. CA-37404) and the Mayo Clinic Foundation.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: Malini Iyengar,GlaxoSmithKline(C)Consultant or Advisory Role: Charles L. Loprinzi, CoNCERT Pharmaceuticals (C); Vered Stearns, Wyeth (C), JDS Pharmaceuticals (C), CoNCERT Pharmaceuticals (C); Thomas Guttuso Jr, Depomed (C)Stock Ownership: None Honoraria: None Research Funding: Vered Stearns,GlaxoSmithKlineExpert Testimony: None Other Remuneration: Thomas Guttuso Jr, US Patent 6310098, owned by University of Rochester

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Charles L. Loprinzi, Jeff Sloan, Vered Stearns, Brent Diekmann, Gretchen Kimmick, Paul Gordon, Kishan Pandya, Thomas Guttuso Jr, Debra Barton, Paul Novotny

Administrative support: Charles L. Loprinzi, Jeff Sloan

Provision of study materials or patients: Charles L. Loprinzi, Vered Stearns, Rebecca Slack, Malini Iyengar, Gretchen Kimmick, James Lovato, Paul Gordon, Kishan Pandya, Thomas Guttuso Jr

Collection and assembly of data: Charles L. Loprinzi, Jeff Sloan, Brent Diekmann, Paul Novotny

Data analysis and interpretation: Charles L. Loprinzi, Jeff Sloan, Brent Diekmann, Debra Barton

Manuscript writing: Charles L. Loprinzi, Jeff Sloan, Vered Stearns, Rebecca Slack, Malini Iyengar, Brent Diekmann, Gretchen Kimmick, James Lovato, Paul Gordon, Kishan Pandya, Thomas Guttuso Jr, Debra Barton, Paul Novotny

Final approval of manuscript: Charles L. Loprinzi, Jeff Sloan, Vered Stearns, Rebecca Slack, Malini Iyengar, Brent Diekmann, Gretchen Kimmick, James Lovato, Paul Gordon, Kishan Pandya, Thomas Guttuso Jr, Debra Barton, Paul Novotny

REFERENCES

- 1.McKinlay SM, Jefferys M. The menopausal syndrome. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1974;28:108–115. doi: 10.1136/jech.28.2.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: Principal results from the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loprinzi CL, Pisansky TM, Fonseca R, et al. Pilot evaluation of venlafaxine hydrochloride for the therapy of hot flashes in cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:2377–2381. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.7.2377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loprinzi CL, Kugler JW, Sloan JA, et al. Venlafaxine in management of hot flashes in survivors of breast cancer: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;356:2059–2063. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03403-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loprinzi CL, Sloan JA, Perez EA, et al. Phase III evaluation of fluoxetine for treatment of hot flashes. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1578–1583. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.6.1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stearns V, Slack R, Greep N, et al. Paroxetine is an effective treatment for hot flashes: Results from a prospective randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6919–6930. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.10.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stearns V, Beebe KL, Iyengar M, et al. Paroxetine controlled release in the treatment of menopausal hot flashes: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2827–2834. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.21.2827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kimmick GG, Lovato J, McQuellon R, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study of sertraline (Zoloft) for the treatment of hot flashes in women with early stage breast cancer taking tamoxifen. Breast J. 2006;12:114–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2006.00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans ML, Pritts E, Vittinghoff E, et al. Management of postmenopausal hot flushes with venlafaxine hydrochloride: A randomized, controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:161–166. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000147840.06947.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suvanto-Luukkonen E, Koivunen R, Sundstrom H, et al. Citalopram and fluoxetine in the treatment of postmenopausal symptoms: A prospective, randomized, 8-month, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Menopause. 2005;12:18–26. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200512010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gordon PR, Kerwin JP, Boesen KG, et al. Sertraline to treat hot flashes: A randomized controlled, double-blind, crossover trial in a general population. Menopause. 2006;13:568–575. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000196595.82452.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grady D, Cohen B, Tice J, et al. Ineffectiveness of sertraline for treatment of menopausal hot flushes: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:823–830. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000258278.73505.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guttuso TJ., Jr Gabapentin's effects on hot flashes and hypothermia. Neurology. 2000;54:2161–2163. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.11.2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loprinzi C, Barton D, Sloan J, et al. Pilot evaluation of gabapentin for treating hot flashes. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:1159–1163. doi: 10.4065/77.11.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guttuso T, Jr, Kurlan R, McDermott MP, et al. Gabapentin's effects on hot flashes in postmenopausal women: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:337–345. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02712-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pandya KJ, Morrow GR, Roscoe JA, et al. Gabapentin for hot flashes in 420 women with breast cancer: A randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:818–824. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67215-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reddy SY, Warner H, Guttuso T, Jr, et al. Gabapentin, estrogen, and placebo for treating hot flushes: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:41–48. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000222383.43913.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelson HD, Vesco KK, Haney E, et al. Nonhormonal therapies for menopausal hot flashes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006;295:2057–2071. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sloan JA, Loprinzi CL, Novotny PJ, et al. Methodologic lessons learned from hot flash studies. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:4280–4290. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.23.4280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kirsch I, Deacon BJ, Huedo-Medina TB, et al. Initial severity and antidepressant benefits: A meta-analysis of data submitted to the Food and Drug Administration. PLoS Med. 2008;5:260–268. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goetz MP, Rae JM, Suman VJ, et al. Pharmacogenetics of tamoxifen biotransformation is associated with clinical outcomes of efficacy and hot flashes. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9312–9318. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.3266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stearns V, Johnson M, Rae J, et al. Active tamoxifen metabolite plasma concentrations after coadministration of tamoxifen and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor paroxetine. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1758–1764. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bardia A, Novotny P, Sloan J, et al. Efficacy of non-estrogenic hot flash therapies among women stratified by breast cancer history and tamoxifen use: A pooled analysis. Menopause. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31818c91ca. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loprinzi CL, Barton DL, Sloan JA, et al. Newer antidepressants for hot flashes-should their efficacy still be up for debate? Menopause. 2009;16:184–187. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31817dfd2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loprinzi C. Gabapentin for hot flashes in men: NCCTG trial N00CB. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(suppl):494S. abstr 9005. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carpenter JS, Storniolo AM, Johns S, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trials of venlafaxine for hot flashes after breast cancer. Oncologist. 2007;12:124–135. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-1-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barton DL, LaVasseur B, Sloan JA, et al. A phase III trial evaluating three doses of citalopram for hot flashes: NCCTG Trial N05C9. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(suppl):511s. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.6379. abstr 9538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Speroff L, Gass M, Constantine G, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of desvenlafaxine succinate treatment for menopausal vasomotor symptoms: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:77–87. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000297371.89129.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]