Abstract

Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) is an important regulator of normal development and homeostasis, and dysregulated signaling through the HGF receptor, Met, contributes to tumorigenesis, tumor progression and metastasis in numerous human malignancies. The development of selective small-molecule inhibitors of oncogenic tyrosine kinases (TK) has led to well-tolerated, targeted therapies for a growing number of cancer types. To identify selective Met TK inhibitors, we used a high-throughput virtual screen of the 13.5 million compound ChemNavigator database to find compounds most likely to bind to the Met ATP binding site and to form several critical interactions with binding site residues predicted to stabilize the kinase domain in its inactive conformation. Subsequent biological screening of 70 in silico hit structures using cell-free and intact cell assays identified three active compounds with micromolar IC50 values. The predicted binding modes and target selectivity of these compounds are discussed and compared to other known Met TK inhibitors.

Introduction

Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) is a secreted, heparin-binding protein that stimulates mitogenesis, motogenesis, and morphogenesis in a wide spectrum of cellular targets. Its receptor is the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) Met. Activation of the HGF/Met signaling pathway leads to a variety of cellular responses, including proliferation and survival, angiogenesis, and motility and invasion.1 Overexpression of Met and/or uncontrolled activation of its signaling pathway occurs in many human cancers. The presence of increased expression of either Met or HGF in tumor cell lines has been shown to correlate with tumor aggressiveness and decreased survival rates in several types of cancer.2 Germline and somatic missense mutations in the kinase domain of Met, leading to increased kinase activity, have been found in papillary renal cell carcinomas. This suggests that selective inhibition of the kinase domain may be a viable therapeutic strategy for the treatment of papillary renal carcinoma and possibly several other human cancers.

The overall structure of the Met receptor is that of a typical RTK, with an extracellular ligand binding domain, a transmembrane helix, and an intracellular kinase domain. HGF binding to the extracellular domain promotes receptor clustering and the autophosphorylation of several tyrosine residues in the kinase domain, leading to kinase activation.1 The intracellular domain has the standard kinase fold, with an amino-terminal β-sheet-containing lobe and a carboxyl-terminal helical lobe connected through a hinge region. The ATP binding site is in a deep, narrow, coin-slot-like cleft between the two lobes.3 Most existing kinase domain inhibitors target the ATP binding site. It was originally thought that identifying inhibitors selective to only one kinase domain would be difficult, since there are many kinases, all of which bind ATP, and the sequence of residues in the ATP binding site is highly conserved.4 However, in recent years many selective kinase inhibitors have been developed. One method for achieving selectivity is to target an inactive conformation of the binding site.5 This is a useful strategy for Met because in the crystal structure complexed with the staurosporine analog K-252a, the activation loop adopts a unique inhibitory conformation such that ATP and substrate peptides cannot bind.3

Here we describe a virtual screen to identify new compounds that inhibit the Met kinase and specifically its conformation in the inactive state. The general objective of virtual screening is to select a small subset of compounds predicted to have activity against a given biological target out of a large database of commercially available samples. In conventional high-throughput screening, thousands to hundreds of thousands of compounds are physically tested in parallel. The goal of virtual high-throughput screening is to test compounds computationally in order to reduce the number of compounds that are tested experimentally. The number of compounds in the final set can be adjusted according to the resources available for assaying. A variety of computational methods can be used for virtual screening depending on the desired size of the final subset and on the amount of information known about the target, its natural ligands, and any known inhibitors. The screening methods used here included filtering of a large database of commercially available compounds based on physicochemical properties, receptor–ligand docking and scoring, and pharmacophore searches within the docking results. This produced an initial subset of approximately 600,000 compounds, which was reduced to a final set of 175 molecules. This set had very little structural similarity to any known kinase inhibitors. The set was ranked using detailed forcefield calculations, and the top 70 compounds were purchased for testing in a cell-free system as well as in intact cells using a two site electrochemiluminescent immunoassay of Met activation. Three of the compounds tested showed inhibition of Met at micromolar or submicromolar levels.

Results and Discussion

Virtual Screen

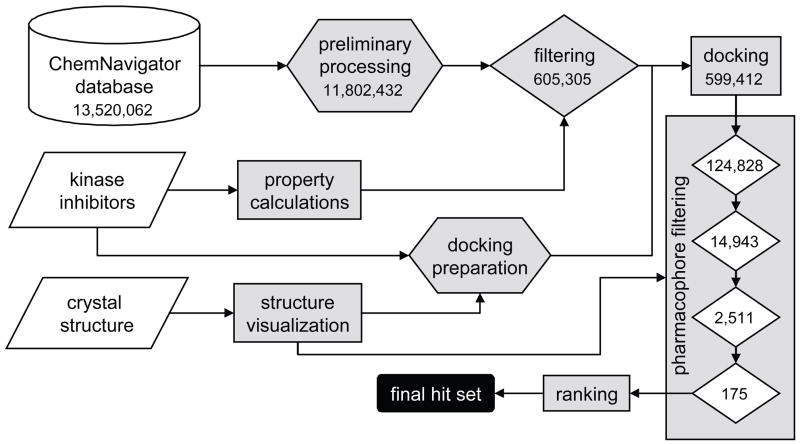

Figure 1 shows a schematic summary of the overall virtual screening procedure followed in this study. The ChemNavigator database (November 2004 release) consisted of a compilation of 13.5 million commercially available chemical samples from 154 international chemistry suppliers. During preliminary processing of the database, we added explicit hydrogens and calculated three-dimensional coordinates for each molecule. The first stage of processing was designed to remove generally unsuitable and undesirable compounds: very large and very small molecules, inorganic compounds, molecules whose lipophilicity was considered too high or too low; molecules with more than 15 rotatable bonds (which are not handled well by the docking program), and molecules with more than one undefined stereocenter, whose three-dimensional structures are therefore partially unknown. The processed database was further filtered to choose compounds whose physicochemical properties were within the ranges found in known kinase inhibitors to eliminate from the outset compounds which were unlikely to show any kinase-binding ability. These filtering criteria included molecular weight, number of aromatic rings and rotatable bonds, polar and non-polar surface area, logP, and number of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the virtual screening procedure. The number of compounds at each stage, from the starting point of a large database of small molecules, a crystal structure and a set of known inhibitors, to the end point of a small set of compounds proposed for biological screening, are listed.

The primary target crystal structure used was that of the Met TK domain co-crystallized with the staurosporine analog K-252a.3 The structure was prepared for docking and a test run was performed using a series of 40 known kinase inhibitors from the literature that possessed a variety of core structures.5, 6 The filtered database was then docked using GOLD,7 saving up to ten poses for each compound. The majority of the compounds from prior filtering were docked successfully. As described in more detail in Methods, this was desirable because the scoring function of the docking program had very little predictive ability to discern binders from non-binders.

We used the structural interactions between Met and its ligands for analysis of the docked poses with pharmacophore-based filtering. This step is not typical of virtual screening strategies. Rather, the process generally moves directly from docking to scoring, since the docking program output is a score for each docked pose. However, we have found that filtering the docked poses with a series of pharmacophore queries to remove poses that do not form certain essential interactions with the target binding site significantly improves the quality of the results. Large-scale analysis of docking program performance has shown that, while existing scoring functions are generally good at producing reasonable docked poses of a molecule in a binding site, they are not necessarily good at discriminating between good binders and poor binders.8

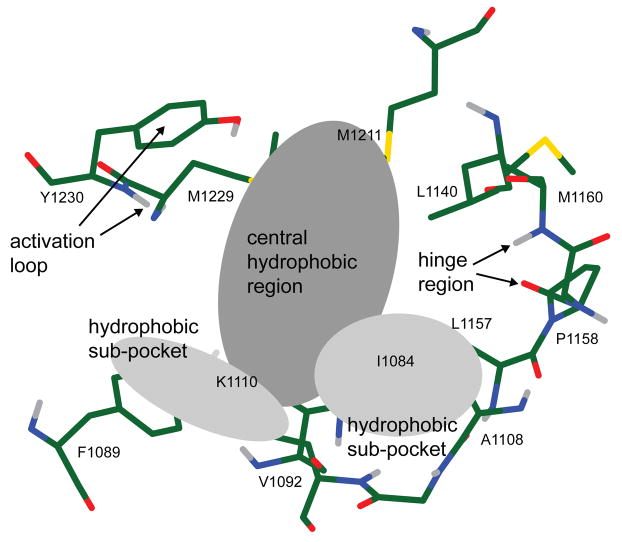

Docking results were filtered to enforce the presence of the following four interactions (Figure 2): 1) a hydrogen bond to residues in the hinge region, which is an interaction that is highly characteristic of all compounds bound to the ATP binding site in kinase domains; 2) a hydrophobic or aromatic interaction filling the central region of the pocket; 3) an additional hydrophobic or aromatic interaction in one of two smaller sub-pockets and 4) either a hydrogen bond to the backbone of residue Y1230 in the activation loop or an aromatic π-stacking interaction with its ring. The substantial movement of the portion of the activation loop surrounding Y1230 upon ligand binding, together with the hydrogen bonding between this tyrosine and the inhibitor K-252a seen in the crystal structure,3 suggest that an interaction with Y1230 may be key to inducing and stabilizing the inhibitory conformation of the activation loop. The docked molecules that satisfied all four interaction criteria gave a final set of 175 compounds.

Figure 2.

Topographical features of the Met ATP binding site used to filter docked poses. An interaction with each defined region of the binding site was required for a successfully docked compound.

Of 175 molecules in the final set, 70 were available for purchase. The available compounds were ranked for priority of testing according to the predicted strength of their interactions with binding site, using eMBrAcE in MacroModel.9 Each docked ligand was energy minimized in the binding site and the total forcefield interaction energy (the sum of the van der Waals, electrostatic, and solvation energies) was calculated. The previously calculated set of physicochemical properties was used to establish that all the compounds followed the Lipinski10 and Veber11 rules for drug-likeness and oral bioavailability, with the exception of a few where logP was modestly higher than typically accepted. Veber’s work suggests that polar surface area is a better predictor of membrane permeability than logP, so these compounds were not eliminated from consideration.

Biological Assays Measuring Met Activation

The 70 commercially available compounds were purchased and screened using cell-free and intact-cell assays developed to measure Met TK activation as represented by receptor autophosphorylation. Both assays were two-site immunoassays that utilize electrochemiluminescent detection, which provides significantly greater sensitivity and dynamic range relative to conventional enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) methods. Assay results were normalized to standard curves prepared using recombinantly expressed, purified Met proteins to maximize reproducibility and quantitation of kinase inhibition. Biological testing yielded three preliminary hit compounds that inhibited Met TK autophosphorylation induced by the addition of ATP and metal ions to unstimulated receptor in detergent solution and by ligand treatment of intact, quiescent normal human mammary epithelial cells (Table 1). Compound 1 inhibited kinase activity in the cell-free assay with an IC50 of 0.675 μM and inhibited HGF-induced Met activation in intact cells with an IC50 of 30 μM. Compound 2 inhibited kinase activity in the cell-free assay with an IC50 of 43 μM and Met activation in intact cells with an IC50 of 50 μM, while compound 3 inhibited Met activation in intact cells with an IC50 of 30 μM. Each compound showed greater than 95% inhibition at or less than 100 μM.

Table 1.

Met TK IC50 and maximal inhibition values of hit compounds.

| Hit Compound | Met TK IC50 (uM) | Max Inhibition (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CELL-FREE | INTACT CELLS | INTACT CELLS | |

| 1 | 0.675 | 30 | 98 |

| 2 | 43 | 50 | 95 |

| 3 | ND | 30 | 98 |

ND = not determined.

Docked Structures of Preliminary Hits

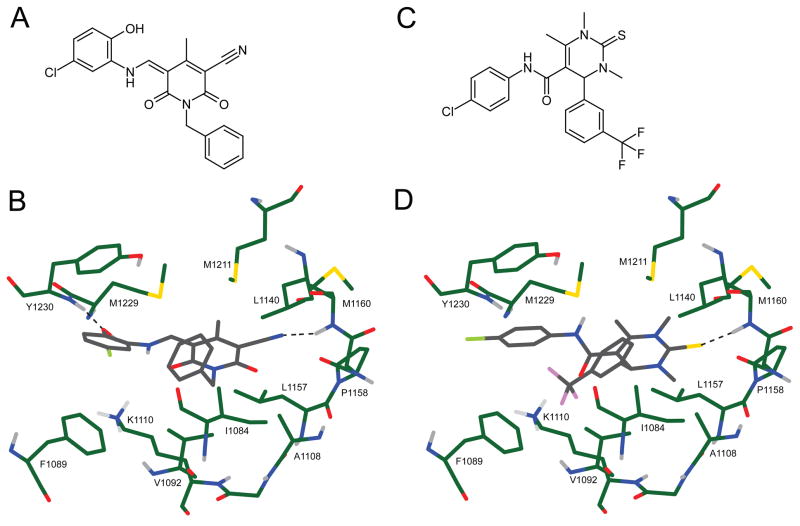

The structures of compounds 2 and 3, along with their binding modes as predicted by docking, are shown in Figure 3. Both compounds have a 3-ring structure in which the central ring forms a hydrogen bonding interaction with the backbone of residue M1160 in the hinge region. Interestingly, in both cases these hydrogen bonds are somewhat unusual, occurring via a cyano group in the case of compound 2 and a thione in the case of compound 3. A second, hydrophobic ring is buried in the binding pocket and interacts with hydrophobic residues I1084, V1092, M1211 and M1229. The third ring is oriented along the surface edge of the binding site and makes an aromatic ring-stacking interaction with Y1230, along with a hydrogen bond to its backbone in the case of compound 2. The lower binding affinity of compound 3 relative to 2 indicated in cell-free kinase assays can be explained by the lack of hydrogen bonding to Y1230, and a weaker hydrogen bond to the hinge via the thione compared to the cyano group.

Figure 3.

A) Chemical structure of compound 2. B) Chemical structure of compound 3. C) Predicted binding orientation and residue interactions of compound 2. D) Predicted binding orientation and residue interactions of compound 3.

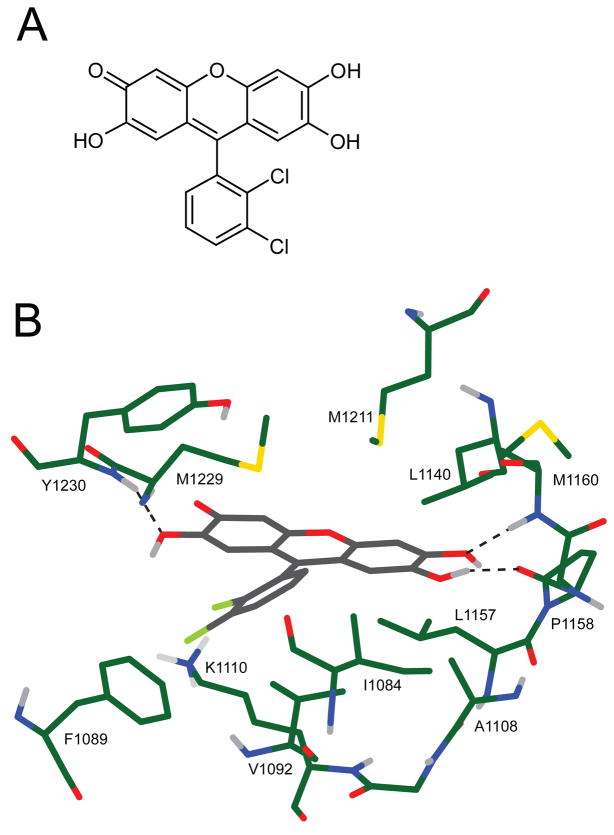

The structure of compound 1 with its predicted binding site orientation is shown in Figure 4. This compound has a central structure of three linked rings, one side of which hydrogen bonds to hinge residues M1160 and P1158, while the other side interacts with Y1230 in the activation loop. Like compounds 2 and 3, compound 1 also has a hydrophobic ring buried in the binding pocket and interacting with hydrophobic residues I1084, V1092, F1089 and M1229. The chlorine atoms on this phenyl ring form somewhat unfavorable van der Waals interactions with one side of the central linked ring structure. This is due to the fact that the docking was done with a static receptor in which the binding site is not quite wide enough for the rings to adopt a more orthogonal orientation, no doubt because the co-crystallized ligand is planar.3 The range of existing crystal structures of Met3, 12, 13 confirm the plasticity of this kinase in molding the activation and nucleotide-binding loops to the shape of the ligand in the ATP binding site, so we anticipate that this compound could easily be accomodated with a small conformational shift.

Figure 4.

A) Chemical structure of compound 1. B) Predicted binding orientation and residue interactions of compound 1.

Comparison with Other Met Inhibitors

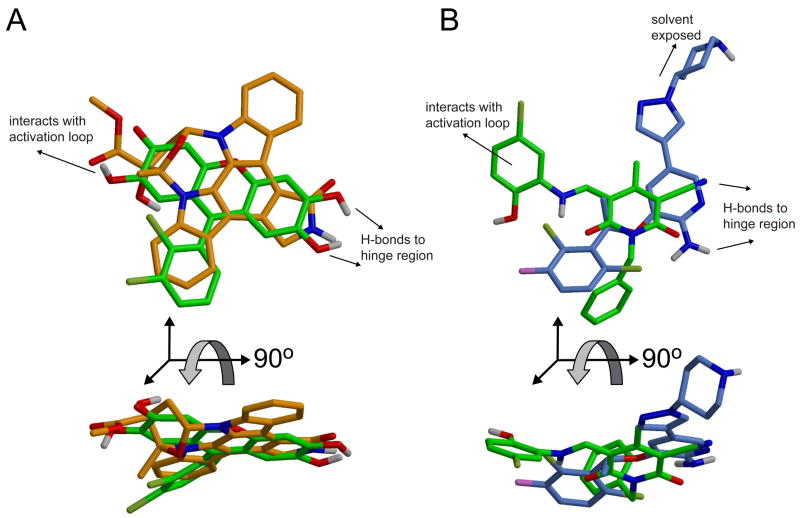

Compound 1 is generally similar in shape to the co-crystal structure ligand K-252a.3 An overlay of its docked pose to the binding mode of K-252a shows the central three linked rings aligned across one axis of the planar K-252a structure, with the chloro-phenyl ring partially overlapping one of the non-polar side rings (Figure 5A,C). PF-02341066, a potent Met inhibitor whose preclinical evaluation was recently published,14 is structurally similar to compound 2 in that it has a central ring which hydrogen bonds to the hinge backbone and an adjacent hydrophobic ring which is buried in the binding pocket (Figure 5B,D). PF-02341066 does not, however, form any interactions with Y1230 or surrounding regions of the activation loop.

Figure 5.

A & C) Overlay of the docked position of compound 1 (grey) with the crystal structure of Met inhibitor K252-a (orange). B & D) Overlay of the docked positions of compound 2 (grey) with the Met inhibitor PF-02341066 (blue). The orientation of the compounds in views A and B is the same as that shown in Figures 3 and 4, whereas views C and D are rotated by 90 degrees about the X axis for clarity in visualizing the overlay.

PHA665752 and SU11274 are potent and selective inhibitors for c-Met from a family of rationally-designed pyrrole indolinones.2, 15, 16 However, we discovered as we began docking calculations that these indolinone compounds, which were designed using a homology model of Met built from the structure of the closely related fibroblast growth factor receptor-1 (FGFR1) kinase,2 do not fit into the Met/K-252a co-crystal structure3 binding site due to the conformation of the activation loop. The moiety at the 5-position of the indolinone ring, which was designed to displace a water molecule in the FGFR1 structure, is the portion of the structure that does not fit. The sulfoxide clashes with M1229 and the chlorinated phenyl ring clashes with V1092 and F1089 in the hydrophobic region of the binding site (Figure 2). The recently released structure of Met bound to SU1127412 suggests that these compounds are likely to be accommodated by a shift in the position of the activation loop and a flip of the Y1230 sidechain to pack against the chlorinated phenyl ring. This shift in loop conformation to maintain the interaction with Y1230 confirms the importance of interactions with this residue in conferring binding affinity. Similarly, in the structures of Met bound to triazolopyridazines, Y1230 is observed to form a π-stacking interaction with the heteroaromatic ring system in those compounds.13

In contrast to the indolinone and triazolopyridazine compounds, both 1 and 2 form hydrogen bonds to the backbone of residue Y1230, rather than simply making an aromatic ring-stacking interaction. This suggests that these compounds might be effective inhibitors of the mutated variants Y1230H/C/D (SwissProt P08581, also known as Y124817 in the context of GenBank J02958), unlike SU11274.18

Similarity to Other Kinase Inhibitors

To examine the chemical novelty of the three hits, we looked for any similarity to compounds in a commercial database of 170,000 known kinase inhibitors (Kinase ChemBioBase from Jubilant Biosys), as well as a set of 7,944 compounds with reported binding affinities against kinase targets from BindingDB19. The databases were searched using SciTegic extended connectivity functional class fingerprints20 for compounds similar to any of the three hits. No compounds were found in either database with a Tanimoto similarity21 higher than 0.4 to compound 1 or higher than 0.5 to compounds 2 and 3, suggesting that these hits do not have any significant sub-structural similarity to known kinase inhibitors.

Selectivity Assessment of Hit Compound 1

The submicromolar potency of compound 1 for inhibition of Met ATP binding and autophosphorylation prompted us to investigate the activity of this compound against other structurally related, oncogenically relevant TKs. A panel of 10 TKs: Abelson murine leukemia viral oncogene homolog 1 (ABL1), anaplastic lymphoma receptor tyrosine kinase (ALK), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), FGFR1, insulin-like growth factor receptor 1 (IGF1R), vascular endothelial cell growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2), Met, macrophage stimulating 1 receptor (MST1R), platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta (PDGFR beta) and v-ros avian UR2 sarcoma virus oncogene homolog 1 (ROS1), was selected for analysis through the SelectScreen Kinase Profiling Service (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The assay method employs a fluorescence-coupled enzyme format and is based on the differential sensitivity of phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated peptides to proteolytic cleavage. A significant benefit of this ratiometric method for quantitating reaction progress is the elimination of well-to-well variation in peptide concentration and signal intensities. The results of this analysis are summarized in Table 2. Significant inhibition (>50%) at 10 μM for compound 1 was observed for Met, VEGFR2, ABL1 and FGFR1, with greatest relative inhibition of FGFR1. Very little (<10%) inhibition was observed for IGF1R or PDGFRB.

Table 2.

Initial TK selectivity profile of compound 1.

| Kinase Tested | Mean Inhibition at 10 uM (%) |

|---|---|

| ABL1 | 60 |

| ALK | 36 |

| EGFR (ERBB1) | 14 |

| FGFR1 | 85 |

| IGF1R | −7 |

| KDR (VEGFR2) | 73 |

| MET (CMET) | 55 |

| MST1R (RON) | 45 |

| PDGFRB (PDGFR BETA) | 8 |

| ROS1 | 27 |

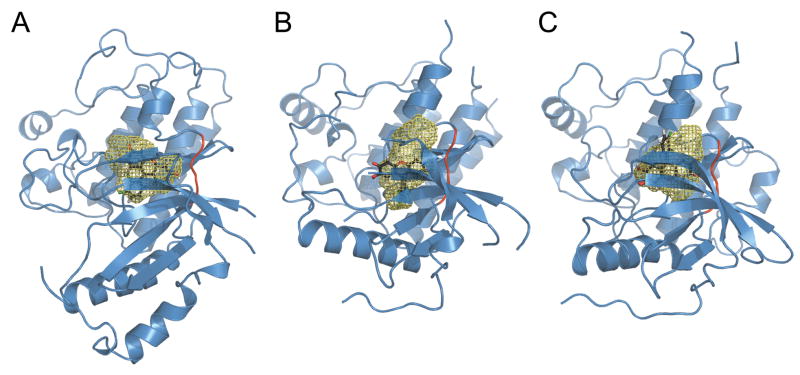

To identify the structural basis for these differences in affinity, we performed additional docking studies with GOLD7 to examine the interactions of compound 1 with those TKs for which it had the highest and lowest affinities: FGFR1 (85% inhibition) and IGF1R (no observed inhibition). We used the crystal structures of FGFR1 bound to the inhibitor PD 17307422 and of IGF1R bound to a nonhydrolyzable ATP analog.23 The volume of each binding site was visualized (Figure 6) using the program PASS,24 which fills the cavities in a structure with a set of solvent-excluded probe spheres.

Figure 6.

Peptide backbone structural models of the ATP binding sites of A) Met, B) FGFR1 and C) IGFR1 with compound 1 docked in the ATP binding site. The hinge region is shown in red. The solvent-excluded volume in the binding site, as calculated by the program PASS,24 is outlined in yellow mesh. This figure was created using PyMOL.40

As expected from the selectivity screen, 1 binds well to the FGFR1 structure, with its chlorinated phenyl ring buried more deeply in the binding site than observed for Met. The hydrophobic subpocket where this ring fits is deeper and larger in FGFR1 than in Met, as shown in Figure 6A and B, and the ring fits in much the same position as the dimethoxy phenyl ring of PD 173074, which has been shown to confer FGFR selectivity to that class of compounds.22 For IGF1R, in contrast, this subpocket is essentially nonexistent (Figure 6C), and 1 is mis-docked “upside down” with the chlorinated phenyl ring outside the binding site, consistent with the low observed selectivity for that kinase. These docking results suggest that the selectivity of analogs of 1 could be tuned to favor either FGFR1 or Met by adjusting the size and nature of substituents on the phenyl ring. Such modifications could presumably also affect binding affinity to the clinically relevant Met mutant V1092I (V111017 in GenBank J02958), in which the size of the hydrophobic subpocket is likely to be reduced.

While the strategy of developing TK inhibitors with selectivity for a single kinase offers theoretical advantages in limiting potential off-target toxicity, it is also possible that many such compounds will have limited efficacy as single agent anti-cancer therapies, due in part to the development of drug-resistant mutations in tumor cell lines. The number of selective, molecularly targeted therapies being tested in combinations in human clinical trials is growing rapidly, particularly for cancers where multiple oncogenic determinants have been identified. Thus, engineering a TK inhibitor with selectivity for a small group of known, disease-critical kinases may offer the advantages of broad action without the development cost of singularly-targeted agents or the potential toxicity of broad-acting agents with poorly defined selectivity. A potent inhibitory effect on FGFR1, an important mediator of angiogenesis, could prove to be a very desirable feature of a small molecule Met antagonist. FGFR1-mediated signaling has been implicated in the progression of a wide variety of solid tumor types where Met activation also occurs, including pancreatic and thyroid cancers.25, 26 FGFR1 gene amplification occurs in breast cancer27 and overexpression occurs in the majority of high-grade prostate cancers.28

Inhibitors with combined activity against VEGFR2 and FGFR1 are known; for example, brivanib alaninate (Bristol-Myers Squibb) is currently in clinical trials for a variety of solid tumors.29 Similarly, inhibitory activity against VEGFR2 has been reported for other Met TK inhibitors such as XL880,30 PHA665752, and SU11274.1, 31, 32 However, a Met/FGFR1 or Met/FGFR1/VEGFR2 inhibitor would be novel and a logical target combination for a variety of human cancers.

Conclusions

The HGF/Met signaling pathway contributes to tumorigenesis, tumor progression and metastasis in numerous human malignancies. Using a high-throughput virtual screening approach to identify potential competitive inhibitors of the Met TK ATP binding site, a set of 70 compounds was selected from the 13.5 million compound ChemNavigator database for biological testing. This set was found to contain three compounds with IC50 values for inhibition of Met TK activation in the submicromolar to 50 micromolar range. This hit rate (4%) is comparable to those of other combined virtual and physical screens, particularly those of very large compound libraries not enriched for specific structure types.33, 34 Our results offer another illustration of the efficiency of virtual screening compared to physical high-throughput screening approaches that frequently process 100,000 or more compounds. Here, with the modest effort and expense involved in screening only 70 compounds, we have identified three interesting new hits. The properties of these hit compounds warrant further biological and computational development, which is already underway.

Importantly, the hits identified in our study had little structural similarity to other known Met TK inhibitors, highlighting an important feature of the virtual screening approach. Despite this limited similarity, the active ligands were capable of supporting several key binding interactions common to those known compounds. Outside of these common critical interactions, the novel structures provide new opportunities to chemically improve affinity, selectivity, bioavailability and toxicity profiles. The selectivity assessment of the active compounds reported here against a panel of sequence-related and oncogenically relevant TKs, combined with additional docking studies, reinforced key Met binding interactions and revealed interactions likely to impart high affinity binding for FGFR1, along with interactions that may confer or remove selectivity toward clinically relevant Met kinase domain mutations. A better understanding of the structural and chemical determinants of selectivity is the first step toward the rational design of potent Met TK antagonists with activity against strategically chosen TK combinations.

Experimental Section

Database Processing

The ChemNavigator iResearch Library (August 2004 release plus the November 2004 update) was processed using the chemoinformatics toolkit CACTVS35 to add explicit hydrogens to the chemical structures, standardize the encoding of certain functional groups, and generate three-dimensional coordinates with CORINA.36 In preliminary filtering using the program Pipeline Pilot,37 we removed any salts and solvents, keeping only the largest fragment in each molecular record, and filtered out compounds containing atoms other than H, C, N, O, P, S, F, Cl, Br, and I; compounds with a molecular weight less than 100 or greater than 800; compounds with more than 15 rotatable bonds (excluding terminal rotors); compounds with a logP of less than −3.0 or greater than 8.0; and compounds with more than one undefined stereocenter. Any duplicate structures were then eliminated.

Preparation of Crystal Structures

For the virtual screening run, the crystal structure (PDB code 1R0P) of the kinase domain of Met crystallized with the inhibitor K-252a3 was prepared for docking by deleting the crystal waters, capping the terminal and loop ends (where regions of the sequence were disordered in the crystal) with neutral amine or aldehyde groups, and adding explicit hydrogens. The binding site was defined as a sphere with radius 10 Å, centered at the midpoint of the bond between atoms C3 and C4 in K-252a.

For selectivity analysis of compound 1, the crystal structure of FGFR1 bound to the inhibitor PD 17307422 (PDB code 2FGI) and the crystal structure of IGF1R bound to adenosine 5′-(beta, gamma-imido)triphosphate (AMP-PNP)23 (PDB code 1JQH) were used. As with Met, these structures were prepared for docking by deleting crystal waters (and the B chain in the case of 2FGI), capping chain ends with neutral groups, and adding explicit hydrogens. Coordinates were also built for all incompletely resolved surface side chains, none of which were near the binding site. The 10 Å binding site sphere was centered at the position of ligand atom C31 for 2FGI, and ligand atom N9 for 1JQH.

Validation of Docking Protocol

A small database of four known Met inhibitors2, 16 along with K-252a38 and staurosporine was constructed to be used as a test case for determining optimal docking parameters. As discussed above, these inhibitors do not fit in the 1R0P crystal structure binding site, so a second small database composed of a series of 40 known kinase inhibitors with a variety of core structures from the literature5, 6 was also constructed. Two GOLD7 docking runs to compare the GoldScore fitness function to the ChemScore fitness function were executed. We had found in prior work that the “library screening” genetic algorithm settings performed poorly, so the “7–8 times speedup” settings were used and the docking results were analyzed to choose a scoring function and a reasonable score cutoff value. There are no Ki or binding affinity data for this set of kinase inhibitors against Met, so we were unable to compare the scores from the two different scoring functions to experimental data. However, we found that ChemScore generated poses that were consistent with experimentally determined binding modes of the known inhibitors, although the value of the score itself had no predictive ability to distinguish between high- and low-affinity compounds. The ChemScore scoring function was therefore used with a generous score cutoff for keeping poses, since a low score did not necessarily mean that a pose was bad in this case.

Met-Specific Filtering of Processed ChemNavigator Database

The test database of kinase inhibitors was also used to look for reasonable ranges for logP, polar surface area, molecular weight and other properties for filtering potential new inhibitors. A set of 32 properties for the known inhibitors was calculated using MOE37 and Pipeline Pilot,37 including several versions of logP, logD and solubility, and various estimations of polar/non-polar surface area. Based on these results, the processed ChemNavigator database was filtered to keep only compounds with molecular weights between 250 and 500, more than 2 aromatic rings, fewer than 4 rotatable bonds (not counting terminal rotors), between 2 and 5 hydrogen bond acceptors, between 1 and 3 hydrogen bond donors, a logP value between 1.0 and 6.0, no phosphate or sulfate groups, a polar surface area less than 100 Å2, and a nonpolar surface area of at least 200 Å2.

Docking

Docking runs were performed using the program GOLD 2.17 with the “7–8 times speedup” genetic algorithm settings for virtual screening, and the default settings for follow-up analysis. The ChemScore fitness function was used with the “flip ring corners,” “flip planar N,” and “internal H-bonds” flags set. Early termination was allowed if the top 5 solutions were within 1.5 Å root mean square deviation (RMSD). The ten highest-scoring poses were saved for each compound, and poses with ChemScore fitness less than 20.0 were rejected. The results and scores were saved in a single self-describing (SD) file for each run.

Pharmacophore-based Filtering

A series of four receptor-based pharmacophore filters were created in MOE39 by defining required hydrogen bond or hydrophobic features for ligands based on the positions of atoms in the binding site. The first filter eliminated all poses that did not have a hydrogen bond to the backbone of hinge residues P1158 or M1160. The second filter eliminated all poses that did not have a hydrophobic or aromatic interaction with the central hydrophobic residues I1084, V1092, M1211 and M1229. The third filter defined a point at the centroid of atoms V1092 Cγ1, A1108 Cβ and L1157 Cδ1, and a second point at the centroid of atoms F1089 Cε2 and Cζ, and K1110 Cγ, Cδ and Cε. This filter then eliminated all poses that did not have a hydrophobic or aromatic atom within 2.5 Å of at least one of these two points. The fourth filter eliminated all poses that did not have either a hydrogen bond to Y1230 N or an aromatic π-stacking interaction with the tyrosine ring. Succeessful docking required that a molecule passed all four filters. The SD file of docked poses was imported into a MOE database and each pose was annotated with the polarity-charged-hydrophobicity (PCH) pharmacophore scheme. The database was then searched with the “use absolute positions” option in each query to test the poses in the frame of reference of the binding site, as they were docked by the docking program, rather than rotating each molecule to best match the query.

Ranking Commercially Available Compounds

The set of physicochemical properties (molecular weight, number of hydrogen bond acceptors and donors, logP, polar surface area, and number of rotatable bonds) calculated previously was used to check the compounds for violations of Lipinski’s Rule of Five10 and Veber’s rules for oral bioavailability.11 To evaluate binding site interactions, each docked ligand was minimized in the binding site and the force field interaction energy between protein and ligand was calculated using eMBrAcE in MacroModel.9 The energy minimization used the Polak-Ribiere conjugate gradient method, with convergence set to a gradient of 0.05, and the optimized potential for liquid simulations - all atom (OPLS-AA) forcefield with implicit generalized Born/surface area (GB/SA) water solvent and extended non-bonded cutoffs. Residues I1084, G1085, F1089, V1092, K1110, L1157, P1158, Y1159, M1160, G1163, M1211, M1229, and Y1230 were allowed to move and a shell of residues within 5 Å of these was restrained with a force constant of 100 kcal/mol; all other residues were frozen. The compounds were then sorted according to the total interaction energy, equal to the sum of the van der Waals, electrostatic, and solvation energies.

Electrochemiluminescent Two-site Immunoassays of Met TK Activity and Content

The human mammary epithelial cell line B5/589 was cultured to 90% confluence in multiwell plates and serum deprived for 48 h prior to use. For intact cell assays only, test compound over a range of concentrations was added for the final 16 h of the serum deprivation period. After drug treatment, cells were rinsed briefly with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), stimulated with HGF (180 ng/ml), or left unstimulated, for 20 min at 37C before lysis and protein extraction with ice cold buffer (pH 7.4) containing non-ionic detergent, protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Protein extracts were clarified by centrifugation, total protein concentration in the supernatant was determined, and aliquots of 500 micrograms were applied to each well of 96-well streptavidin-coated immunoassay plates (MA2400 96 plate, Meso Scale Discovery, Gaithersburg, MD, cat. L15SA-1) that had been coated with a biotinylated anti-Met capture antibody (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, cat. BAF 358) and blocked against non-specific binding with I-Block (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, cat. A1300). For cell-free assays, clarified cell lysates prepared from serum-deprived, untreated cells were applied to the similarly prepared plates. Test compounds at various concentrations were incubated with immobilized Met in the assay plate in a lysis buffer containing 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM MnCl2, 20 uM ATP for 1 h at room temperature. Met activation, as reflected by receptor autophosphorylation, was detected for both intact cell and cell-free samples using a Ruthenium (Ru)-tagged anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (Clone 4G10, Millipore, Billerica, MA, cat. 05–1050). The amount of Met protein captured was detected in parallel using a second Met-specific antibody (R&D Systems, cat. AF276). A tripropylamine-based buffer was added to all wells and electrochemiluminescent light measurements were made using a Sector Imager 2400 plate reader (Meso Scale Discovery). Met protein content was calculated from raw signal values using a standard curve obtained from purified recombinant Met protein (R&D Systems, cat. 358-MT). Met autophosphorylation measurements were normalized to Met protein content; Met content, in turn, was normalized to total protein concentrations to detect effects on Met expression level in intact cell samples. A previously characterized Met ATP binding antagonist, PHA665752 (gift from Dr. James Christensen, Pfizer, Inc.) was used as a positive control, and extracts prepared from resting, non-HGF-stimulated cells were used as a negative control. Vehicle controls were included as needed at the highest concentration present in samples.

Calculations and Statistical Analysis

Drug treatment of intact cells was performed in duplicate wells; all electrochemiluminescence assay samples were performed in triplicate. Mean values from empty wells were subtracted from all other raw values. The standard curve of Met protein content was analyzed by nonlinear regression curve fitting algorithms (Microsoft Excel or GraphPad Prism software) to generate an equation from which sample values for Met content were derived. Mean values among groups were compared for statistically significant differences using unpaired Student’s t-test (p < 0.01) or ANOVA.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research. This project has been funded in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract N01-CO-12400. We thank Dr. James Christensen and Pfizer for the generous gift of PHA665752. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Support: This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

List of Abbreviations

- HGF

Hepatocyte growth factor

- TK

Tyrosine kinase

- RTK

Receptor tyrosine kinase

- EGFR

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- PDGFRb

Platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta

- FGFR1

Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1

- ABL1

Abelson murine leukemia viral oncogene homolog 1

- IGF1R

Insulin-like growth factor receptor 1

- VEGFR2

Vascular endothelial cell growth factor receptor 2

- MST1R

Macrophage stimulating 1 receptor

- ROS1

v-ros avian UR2 sarcoma virus oncogene homolog 1

- ALK

Anaplastic lymphoma receptor tyrosine kinase

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- AMP-PNP

Adenosine 5′-(beta, gamma-imido)triphosphate

- PBS

Phosphate-buffered saline

- RMSD

Root mean square deviation

- SD

Self-describing

- MOE

Molecular operating environment

- PCH

Polarity-charged-hydrophobicity

- GB/SA

Generalized Born/surface area

- OPLS-AA

Optimized potential for liquid simulations - all atom

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

References

- 1.Ma PC, Maulik G, Christensen J, Salgia R. c-Met: structure, functions and potential for therapeutic inhibition. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews. 2003;22:309–325. doi: 10.1023/a:1023768811842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang X, Le P, Liang C, Chan J, Kiewlich D, Miller T, Harris D, Sun L, Rice A, Vasile S, Blake RA, Howlett AR, Patel N, McMahon G, Lipson KE. Potent and selective inhibitors of the Met [hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor (HGF/SF) receptor] tyrosine kinase block HGF/SF-induced tumor cell growth and invasion. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2003;2:1085–1092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schiering N, Knapp S, Marconi M, Flocco MM, Cui J, Perego R, Rusconi L, Cristiani C. Crystal structure of the tyrosine kinase domain of the hepatocyte growth factor receptor c-Met and its complex with the microbial alkaloid K-252a. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2003;100:12654–12659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1734128100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gould C, Wong CF. Designing specific protein kinase inhibitors: insights from computer simulations and comparative sequence/structure analysis. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2002;93:169–178. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(02)00186-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noble MEM, Endicott JA, Johnson LN. Protein kinase inhibitors: insights into drug design from structure. Science. 2004;303:1800–1805. doi: 10.1126/science.1095920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.García-Echeverría C, Traxler P, Evans DB. ATP site-directed competitive and irreversible inhibitors of protein kinases. Medicinal Research Reviews. 2000;20:28–57. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1128(200001)20:1<28::aid-med2>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones G, Willett P, Glen RC, Leach AR, Taylor R. Development and validation of a genetic algorithm for flexible docking. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1997;267:727–748. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Warren GL, Andrews CW, Capelli AM, Clarke B, LaLonde J, Lambert MH, Lindvall M, Nevins N, Semus SF, Senger S, Tedesco G, Wall ID, Woolven JM, Peishoff CE, Head MS. A critical assessment of docking programs and scoring functions. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2006;49:5912–5931. doi: 10.1021/jm050362n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohamadi F, Richards NGJ, Guida WC, Liskamp R, Lipton M, Caufield C, Chang G, Hendrickson T, Still WC. Macromodel - an integrated software system for modeling organic and bioorganic molecules using molecular mechanics. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 1990;11:440–467. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 1997;23:3–25. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Veber DF, Johnson SR, Cheng HY, Smith BR, Ward KW, Kopple KD. Molecular properties that influence the oral bioavailability of drug candidates. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2002;45:2615–2623. doi: 10.1021/jm020017n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bellon SF, Kaplan-Lefko P, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Moriguchi J, Rex K, Johnson CW, Rose PE, Long AM, O’Connor AB, Gu Y, Coxon A, Kim TS, Tasker A, Burgess TL, Dussault I. c-Met inhibitors with novel binding mode show activity against several hereditary papillary renal cell carcinoma related mutations. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283:2675–2683. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705774200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albrecht BK, Harmange JC, Bauer D, Berry L, Bode C, Boezio AA, Chen A, Choquette D, Dussault I, Fridrich C, Hirai S, Hoffman D, Larrow JF, Kaplan-Lefko P, Lin J, Lohman J, Long AM, Moriguchi J, O’Connor A, Potashman MH, Reese M, Rex K, Siegmund A, Shah K, Shimanovich R, Springer SK, Teffera Y, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Bellon SF. Discovery and optimization of triazolopyridazines as potent and selective inhibitors of the c-Met kinase. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2008;51:2879–2882. doi: 10.1021/jm800043g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zou HY, Li Q, Lee JH, Arango ME, McDonnell SR, Yamazaki S, Koudriakova TB, Alton G, Cui JJ, Kung PP, Nambu MD, Los G, Bender SL, Mroczkowski B, Christensen JG. An orally available small-molecule inhibitor of c-Met, PF-2341066, exhibits cytoreductive antitumor efficacy through antiproliferative and antiangiogenic mechanisms. Cancer Research. 2007;67:4408–4417. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sattler M, Pride YB, Ma P, Gramlich JL, Chu SC, Quinnan LA, Shirazian S, Liang C, Podar K, Christensen JG, Salgia R. A novel small molecule met inhibitor induces apoptosis in cells transformed by the oncogenic TPR-MET tyrosine kinase. Cancer Research. 2003;63:5462–5469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christensen JG, Schreck R, Burrows J, Kuruganti P, Chan E, Le P, Chen J, Wang X, Ruslim L, Blake R, Lipson KE, Ramphal J, Do S, Cui JJ, Cherrington JM, Mendel DB. A selective small molecule inhibitor of c-Met kinase inhibits c-Met-dependent phenotypes in vitro and exhibits cytoreductive antitumor activity in vivo. Cancer Research. 2003;63:7345–7355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dharmawardana PG, Giubellino A, Bottaro DP. Hereditary papillary renal carcinoma type I. Current Molecular Medicine. 2004;4:855–868. doi: 10.2174/1566524043359674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berthou S, Aebersold DM, Schmidt LS, Stroka D, Heigl C, Streit B, Stalder D, Gruber G, Liang C, Howlett AR, Candinas D, Greiner RH, Lipson KE, Zimmer Y. The Met kinase inhibitor SU11274 exhibits a selective inhibition pattern toward different receptor mutated variants. Oncogene. 2004;23:5387–5393. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu T, Lin Y, Wen X, Jorissen RN, Gilson MK. BindingDB: a web-accessible database of experimentally determined protein-ligand binding affinities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D198–D201. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rogers D, Brown RD, Hahn M. Using extended-connectivity fingerprints with Laplacian-modified Bayesian analysis in high-throughput screening follow-up. J Biomol Screen. 2005;10:682–686. doi: 10.1177/1087057105281365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Willett P, Barnard JM, Downs GM. Chemical similarity searching. Journal of Chemical Information and Computer Sciences. 1998;38:983–996. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohammadi M, Froum S, Hamby JM, Schroeder MC, Panek RL, Lu GH, Eliseenkova AV, Green D, Schlessinger J, Hubbard SR. Crystal structure of an angiogenesis inhibitor bound to the FGF receptor tyrosine kinase domain. The EMBO Journal. 1998;17:6896–5904. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.20.5896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pautsch A, Zoephel A, Ahorn H, Spevak W, Hauptmann R, Nar H. Crystal structure of bisphosphorylated IGF-1 receptor kinase: Insight into domain movements upon kinase activation. Structure. 2001;9:955–965. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00655-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brady GP, Jr, Stouten PFW. Fast prediction and visualization of protein binding pockets with PASS. Journal of Computer-Aided Molecular Design. 2000;14:383–401. doi: 10.1023/a:1008124202956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Z, Neiss N, Zhou S, Henne-Bruns D, Korc M, Bachem M, Kornmann M. Identification of a fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 splice variant that inhibits pancreatic cancer cell growth. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2712–2719. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kondo T, Zheng L, Liu W, Kurebayashi J, Asa SL, Ezzat S. Epigenetically controlled fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 signaling imposes on the RAS/BRAF/mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway to modulate thyroid cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5461–5470. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elbauomy ES, Green AR, Lambros MB, Turner NC, Grainge MJ, Powe D, Ellis IO, Reis-Filho JS. FGFR1 amplification in breast carcinomas: a chromogenic in situ hybridisation analysis. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:R23. doi: 10.1186/bcr1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sahadevan K, Darby S, Leung HY, Mathers ME, Robson CN, Gnanapragasam VJ. Selective over-expression of fibroblast growth factor receptors 1 and 4 in clinical prostate cancer. J Pathol. 2007;213:82–90. doi: 10.1002/path.2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ayers M, Fargnoli J, Lewin A, Wu Q, Platero JS. Discovery and validation of biomarkers that respond to treatment with brivanib alaninate, a small-molecule VEGFR-2/FGFR-1 antagonist. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6899–6906. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bean J, Brennan C, Shih JY, Riely G, Viale A, Wang L, Chitale D, Motoi N, Szoke J, Broderick S, Balak M, Chang WC, Yu CJ, Gazdar A, Pass H, Rusch V, Gerald W, Huang SF, Yang PC, Miller V, Ladanyi M, Yang CH, Pao W. MET amplification occurs with or without T790M mutations in EGFR mutant lung tumors with acquired resistance to gefitinib or erlotinib. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20932–20937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710370104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma PC, Schaefer E, Christensen JG, Salgia R. A selective small molecule c-MET Inhibitor, PHA665752, cooperates with rapamycin. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:2312–2319. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma PC, Jagadeeswaran R, Jagadeesh S, Tretiakova MS, Nallasura V, Fox EA, Hansen M, Schaefer E, Naoki K, Lader A, Richards W, Sugarbaker D, Husain AN, Christensen JG, Salgia R. Functional expression and mutations of c-Met and its therapeutic inhibition with SU11274 and small interfering RNA in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1479–1488. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shoichet BK. Virtual screening of chemical libraries. Nature. 2004;432:862–865. doi: 10.1038/nature03197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klebe G. Virtual ligand screening: strategies, perspectives and limitations. Drug Discov Today. 2006;11:580–594. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ihlenfeldt WD, Takahashi Y, Abe H, Sasaki S. Computation and management of chemical properties in CACTVS: An extensible networked approach toward modularity and compatibility. Journal of Chemical Information and Computer Sciences. 1994;34:109–116. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gasteiger J, Rudolph C, Sadowski J. Automatic generation of 3D-atomic coordinates for organic molecules. Tetrahedron Computer Methodology. 1990;3:547. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pipeline Pilot [411] San Diego, CA: SciTegic, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morotti A, Mila S, Accornero P, Taglibue E, Ponzetto C. K252a inhibits the oncogenic properties of Met, the HGF receptor. Oncogene. 2002;21:4885–4893. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.MOE: Molecular Operating Environment [200403] Montreal, Canada: Chemical Computing Group, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Delano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System [099] Palo Alto, CA: DeLano Scientific; 2002. [Google Scholar]