Abstract

Reproductive hormones can modulate communication-evoked behavior by acting on neural systems associated with motivation; however, recent evidence suggests that modulation occurs at the sensory processing level as well. The anuran auditory midbrain processes communication stimuli, and is sensitive to steroid hormones. Using multiunit electrophysiology, we tested whether sex and circulating testosterone influence auditory sensitivity to pure tones and to the natural vocalization in the green treefrog, Hyla cinerea. Sex did not influence audiogram best frequencies although sexes did differ in the sensitivities at those frequencies with males more sensitive in the lower frequency range. Females were more sensitive than males in response to the natural vocalization, despite showing no difference in response to pure tones at frequencies found within the advertisement call. Thresholds to frequencies outside the range of the male advertisement call were higher in females. Additionally, circulating testosterone increased neural thresholds in females in a frequency-specific manner. These results demonstrate that sex differences are limited to frequency ranges that relate to the processing of natural vocalizations, and depend on the type of stimulus. The frequency-dependent and stimulus-dependent nature of sex and testosterone influences suggests that reproductive hormones influence the filtering properties of the auditory system.

Keywords: sensory processing, communication, testosterone, vocalization, auditory plasticity, torus semicircularis

Introduction

Reproductive hormones are well established modulators of communication systems in fish (Stoddard et al., 2006), amphibians (Wilczynski et al., 2005) and birds (Ball et al., 2002) with effects readily observable at the level of behavior. Steroid hormones are known to act at forebrain nuclei to influence the motivation to communicate or respond to signals. However, forebrain nuclei rely on input from lower sensory processing areas and there is mounting evidence that hormones also act on the sensory system to modulate processing of communication stimuli (Sisneros et al., 2004; Yovanof and Feng, 1983; Zakon, 1987). In anuran amphibians, males and females often differ in peripheral auditory processing of simple, pure-tone stimuli (Keddy-Hector et al., 1992; McClelland et al., 1997; Narins and Capranica, 1976; Vassilakis et al., 2004; Wilczynski et al., 1984; Wilczynski et al., 1992). However, little is known about how sex differences or hormones influence the processing of more complex communication signals in the central nervous system (Hoke et al., 2008).

The auditory midbrain, the torus semicircularis (TS), is a critical area for investigating the role of reproductive hormones in modulating auditory processing of communication signals. The TS integrates the majority of ascending auditory inputs between the brainstem auditory nuclei and the forebrain (Wilczynski and Capranica, 1984; Wilczynski and Endepols, 2007). This integration results in a specialization within the TS for processing complex stimuli, such as communication signals, in addition to more simple pure-tone stimuli (Feng and Ratnam, 2000; Rose and Gooler, 2007). Testosterone receptors have been reported in the TS of Xenopus laevis (Kelley, 1980) and Rana esculenta (Dimeglio et al., 1987; Guerriero et al., 2005). Single-unit and multiunit neural responses in the TS vary seasonally (Goense and Feng, 2005; Hillery, 1984; Walkowiak, 1980), and gonad removal influences the multiunit audiogram in the TS of male Hyla cinerea (Penna et al., 1992). Hormonal influence on the processing of communication signals in the TS is likely considerable, although unknown.

Sex and testosterone may influence auditory sensitivity at all frequencies within the hearing range of the animal, only at the spectral sensitivity peaks, or at specific frequency bands inside or outside the frequencies of the conspecific call. The inner ear of the anuran contains two physically and functionally different sensory end-organs that process different spectral bands of airborne auditory stimuli (Smotherman and Narins, 2000). The amphibian papilla (AP) is a tonotopic structure that responds to a spectral band of approximately 100–1600 Hz for H. cinerea with two sensitivity peaks, the low best frequency (LBF) and the mid best frequency (MBF). The basilar papilla (BP) responds at a single best excitatory frequency, the high best frequency (HBF), and processes frequencies in the higher range, between 1400–5000 Hz. Both the AP and BP spectral bands are represented in the TS, with multiunit audiograms showing a LBF, MBF and HBF. Previous evidence suggests sexes may differ in the frequency at which they are most sensitive, particularly at the HBF (Keddy-Hector et al., 1992; McClelland et al., 1997; Narins et al., 1976; Wilczynski et al., 1984). Furthermore, relative responses to the two spectral bands may influence behavioral responses to the male advertisement call. Female H. cinerea are sensitive to spectral band differences in the advertisement call such that a call with one attenuated band is less attractive (Gerhardt, 1974). At the level of the TS, H. cinerea is reported to be more sensitive at the LBF and MBF compared to the HBF (Lombard and Straughan, 1974), however, sex and testosterone influences on these relationships have not been examined.

Sex and testosterone may also influence thresholds in a stimulus-specific manner. The neural audiogram has long been used to relate neural sensitivity in response to pure tones with behavioral responses to more complex communication signals. Neural processing of complex stimuli is often not the linear summation of a neuron’s response to pure tones (Rose and Capranica, 1983; Rose and Capranica, 1985; Woolley et al., 2006). These stimulus-specific responses suggest that multiunit thresholds also may depend on the type of stimulus.

In this study we tested the hypothesis that males and females differ in their neural sensitivity to auditory stimuli, in the TS, in a frequency-dependent manner based on peak sensitivities in the auditory system and on spectral characteristics found in the male advertisement call. We also tested the hypothesis that sex differences will be stimulus-dependent by examining thresholds in response to pure tones and the male advertisement call. Lastly we tested whether testosterone modulates these neural responses differently in males and females.

Materials and Methods

Animal Care

We purchased adult male (mean snout-vent length ± SEM: 50.4 ± 0.6 mm) and female (mean snout-vent length: 46.29 ± 1.0 mm) green treefrogs (Hyla cinerea) from two suppliers, NASCO (Fort Atkinson, WI) and Charles Sullivan Co. (Nashville, TN), and housed them in small groups of six animals per 10 gallon aquarium for at least two weeks to acclimate to lab conditions. We fed the frogs crickets ad libitum and provided water in a bowl inside each aquarium. All recordings were conducted between April 19th and June 24th 2004 corresponding with the early to mid breeding season of this species. Environmental conditions were 23°C and 14:10 light:dark cycle.

Hormone manipulation

For the surgical implantation of testosterone, we anesthetized animals by immersion in 2.5% urethane and made a small dorsal cutaneous incision. All individuals were left gonadaly intact and all received subcutaneous implants with Silastic© capsules (1.47mm i.d. × 1.96mm o.d. × 7mm total length) filled with either testosterone (male: n=7, female: n=3) or cholesterol (control, male: n=7, female: n=7) (Burmeister and Wilczynski, 2001). We sealed the incision with Vetbond (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) and placed each animal in its own holding aquarium for 10–12 days. The experimenter that collected the electrophysiology data was blind to the sex and treatment of the individual animals. Following the collection of electrophysiological data, we immediately euthanized the animals and collected a blood sample for hormone analysis. To verify the effectiveness of the testosterone manipulation, we used an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) kit (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI). General methods for the EIA procedure have been previously described (Lynch and Wilczynski, 2006). The kit was validated on pooled samples of H. cinerea plasma diluted to three or four different concentrations that were within the most sensitive portion of the standard curve. The slopes for the standard curve and the pooled plasma samples were parallel (standard curve = −0.074, plasma samples = −0.063). For some animals, we did not collect a sufficient amount of plasma or we could not reliably assay plasma hormone levels. Those animals were omitted from the hormone analysis. The measured androgen levels were the following (mean ± SEM): a) control males 4.7 ± 1.1 ng/ml (n=6), b) control females 6.9 ± 1.2 ng/ml (n=7), c) testosterone-treated males 162.3 ±45.5 ng/ml (n=3) and d) testosterone-treated females 257.1 ±92.3 ng/ml (n=3).

Neurophysiology preparation

Neurophysiological methods were described previously by Wilczynski et al. (1993). Eight to ten days after the testosterone implant, we anesthetized animals in a solution of 2.5% tricaine methanesulfonate (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and cut a section of skin that we folded back to expose the braincase covering the midbrain. To expose the midbrain we cut away a small piece of braincase and replaced it with a damp piece of tissue. We replaced the skin over the exposed area and allowed the animal to recover for two days in its own holding aquarium. On the day of the electrophysiological recordings, we immobilized the animal with an intramuscular injection of curare (d-tubocurarine chloride; 10 μg/g body weight) and applied 2% lidocaine as a local anesthetic to the tissue surrounding the exposed brain area. Recordings took place in an Industrial Acoustics sound-attenuating chamber with the animal draped in wet paper towels. Temperature was monitored with a thermocouple placed near the head of the animal and never deviated from 23°C.

Auditory stimuli

Procedures are detailed in previous studies (McClelland et al., 1997; Wilczynski et al., 1993). Sound was presented to the ear of the animal through a custom made, closed-field earphone system. We used a Brüel & Kjær Digital Precision Integrating Sound Level Meter Type 2230 to calibrate the earphone system and determine the stimulus amplitude at the animal’s ear. Tone production and attenuation were controlled by custom designed hardware. Single frequency tone stimuli (300 ms duration repeated every 1.6 s) at 100–1000 Hz (in 100 Hz steps) and 1200–5000 Hz (in 200 Hz steps) were used to determine midbrain auditory thresholds within the hearing range of this species. We also determined auditory thresholds to a field-recorded advertisement call from a single male H. cinerea in Travis County, TX. The advertisement call was 122 ms in duration with spectral peaks at 825 and 2668 Hz. The characteristics of this call fell within the range of variation described previously (Gerhardt, 1968; Gerhardt, 1974).

Neurophysiology

We assessed acoustically-evoked extracellular multiunit responses in the TS contralateral to the earphone, using a low impedance (0.5–1.5 M•) tungsten electrode (AM Systems, Sequim, WA). Along with the recording electrode, we placed a microinjection needle in the tectal ventricle above the TS on the side opposite the recording site for another study for which the data will not be presented. We identified the TS by its robust response to a search stimulus consisting of two tones (900 Hz and 3000 Hz) presented simultaneously at a peak amplitude of 80 dB SPL. To establish audiograms, we determined auditory thresholds at each frequency by adjusting the attenuation level of the stimulus in 10 dB SPL and then in 1 dB SPL steps, stopping at the lowest sound pressure level that evoked a reliable response. A response was defined as five consecutive bursts of action potentials that coincided with sound presentation, as monitored visually on a storage oscilloscope and acoustically through earphones. The order in which the frequencies were tested within each animal was randomized.

We did not mark recording sites, and therefore were not able to determine from which toral subdivision our recordings were obtained. Given the relatively low impedance of the electrodes and the small size of the H. cinerea brain, each recording likely included neural responses from more than one toral subdivision. We believe our results were obtained from the TS based on visual inspection of electrode placement and on using auditory evoked activity obtained immediately after penetrating the optic tectum, which lies immediately dorsal to the TS. We also note that because all recordings are extracellular we are not able to distinguish activity from TS neurons from that of afferent axons entering the torus from lower brainstem auditory areas, and therefore our measure of TS activity may reflect a combination of both.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics are presented as mean ± SEM unless otherwise noted. For measures of audiogram best frequency, we identified a LBF, MBF and HBF for each animal. Using two-way ANOVA we tested whether sex or testosterone influenced the best frequency and the threshold at each of these peaks. Considering the behavioral relevance of the relative amplitudes of spectral peaks in the male advertisement call, we tested the qualitative observation that the auditory system is more sensitive at the LBF and MBF than it is at the HBF (Lombard and Straughan, 1974) by comparing the relative thresholds at these peaks. We calculated, for each subject, a ratio of the threshold at the LBF to the threshold at the HBF (LBF/HBF) and a ratio of the threshold at the MBF and HBF (MBF/HBF). These ratios were then compared to a null hypothesis of 1.0 using a one-sample t-test. We also compared ratios among the groups using two-way ANOVA.

Comparisons of the audiograms between groups were analyzed using one-way multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA). These analyses were conducted based on the reported range of spectral components in the male advertisement call as established by Gerhardt (1974). The male advertisement call contains two spectral peaks and the variation in the frequency components of those peaks had a range of 761–1340 Hz for the lower range and 2520–3600 Hz for the higher range. MANOVA was performed on thresholds that were grouped by whether or not their corresponding dependent variable (frequency of stimulus) fell within the natural bands of frequencies found at the peaks of the male advertisement call. Stimulus frequencies considered within the advertisement call bands were: 800, 900, 1000, 1200, 1400, 2600, 2800, 3000, 3200, 3400, and 3600 Hz (Figure 1a, vertical grey bars). Frequencies considered outside the bands were: 100, 200, 300, 400, 500, 600, 700, 1600, 1800, 2000, 2200, 2400, 3800, 4000, 4200, 4400, 4600, 4800, and 5000 Hz.

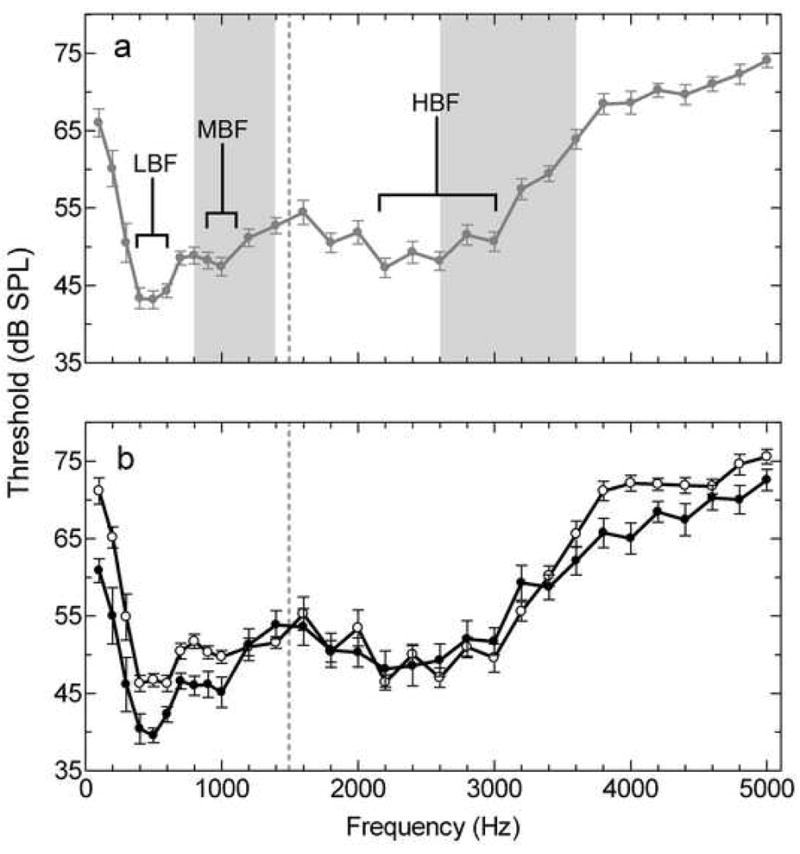

Figure 1.

Mean multiunit audiograms from Hyla cinerea. (a) Male and female audiograms combined. Each filled circle represents the mean threshold in response to the corresponding pure tone (n=14). Brackets denote the three peaks in sensitivity and the grey vertical bars denote the spectral bands of the male advertisement call. This audiogram is consistent with multiunit and behavioral audiograms previously published for this species (Lombard and Straughan, 1974; Penna et al., 1992, Megela-Simmons et al., 1985). (b) Males (filled circles, n=7) and females (open circles, n=7) represented in separate audiograms. The vertical dashed line in (a) and (b) represents the division between the AP and BP range of frequencies. Error bars represent SEM.

Comparisons of mean thresholds in response to the field-recorded male advertisement call were made using two-way ANOVA. A p-value for statistical significance was set at p< 0.05 for all tests in this study. All experimental procedures were performed in accordance with a protocol approved by The University of Texas at Austin Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Results

Neural Audiograms

Neural audiogram peak frequencies and threshold values were typical of those previously reported for Hyla cinerea (Lombard and Straughan, 1974; Penna et al., 1992) (Figure 1a). When males and females in the control condition were considered together, the lower frequency range (100–1600 Hz), corresponding to the amphibian papilla (AP), contained two sensitivity peaks. The first peak, the low best frequency (LBF), had a mean ± SD of 475 ± 73 Hz with a between subject range of 400–600 Hz. The second peak, the mid best frequency (MBF), had a mean of 950 ± 102 Hz with a between-subject range of 800–1200 Hz. The highest frequency range (1400–5000 Hz), corresponding to the basilar papilla (BP), contained a single peak, the high best frequency (HBF), with a mean of 2329 ± 259 Hz and a range between 1900–2800 Hz.

Sex comparisons in the control condition

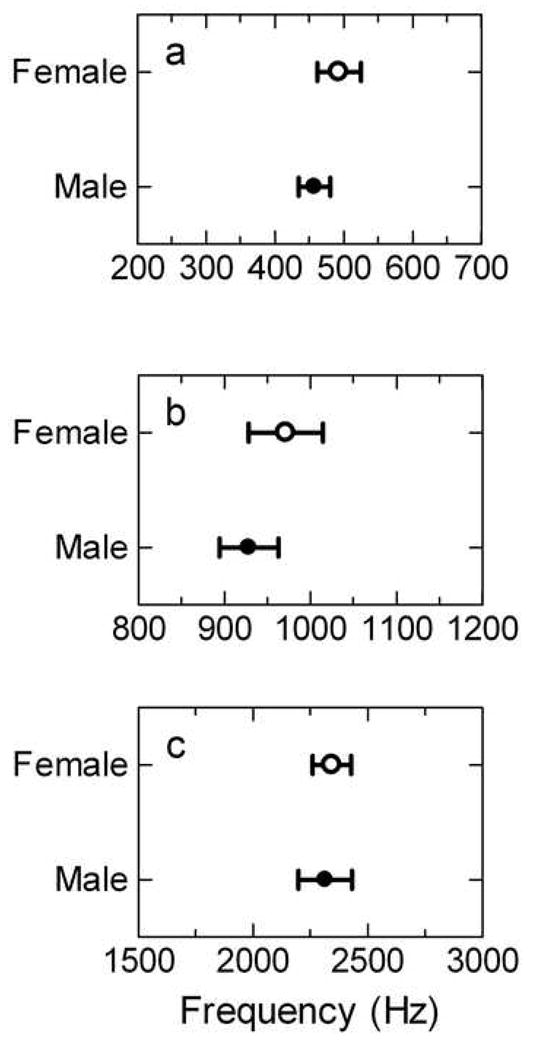

Audiogram best frequencies

Males and females did not differ in the frequencies at which they were most sensitive. The mean LBF for females was 493 ± 32 Hz and for males was 457 ± 23 Hz (Figure 2a) with no main effect of sex [F(1, 20)= 0.570, p=0.459]. The mean MBF for females was 971 ± 43 Hz and for males was 929 ± 34 Hz (Figure 2b) also with no main effect of sex [F(1, 20)= 4.125, p= 0.056]. The mean HBF for females was 2343 ± 84 Hz and for males was 2314 ± 116 Hz (Figure 2c) with no significant sex difference [F(1, 20)= 2.236, p= 0.150]. Previous studies in other anuran species demonstrate that, for some species, size correlates negatively with VIIIth nerve best excitatory frequency (BEF) in the BP range (corresponding here to the HBF in the TS) and significantly influences sex differences (McClelland et al., 1997; Shofner and Feng, 1981). We found no such correlation in H. cinerea at the level of the TS. For the animals in this study, male snout-vent length (SVL) was significantly greater than in females [male: 50.4 mm ± 0.6 N=7, female 46.3 mm ± 1.0, t(12)=3.568, p=0.004] which is consistent with previous reports (Garton and Brandon, 1975). SVL did not correlate with HBF [r (24) = −0.131, p = 0.542] and therefore did not influence the sex comparison.

Figure 2.

Audiogram best frequencies for females (open circles) and males (filled circles) at (a) LBF, (b) MBF and (c) HBF. Error bars represent SEM.

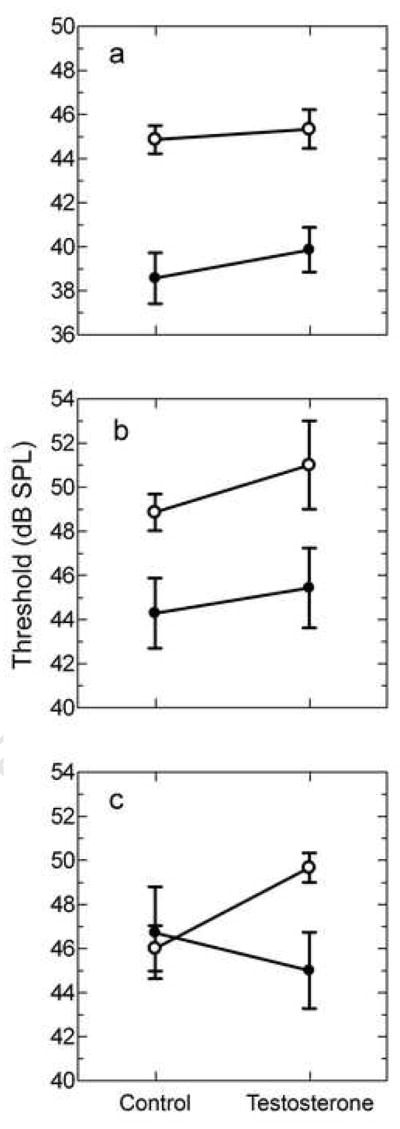

Threshold at audiogram best frequencies

Males had lower thresholds than females at LBF and MBF but not HBF. The mean threshold at LBF for females was 44.9 ± 0.6 dB SPL compared to 38.6 ± 1.2 dB SPL for males (Figure 3a, control) with a significant main effect of sex [F(1, 20)= 30.24, p<0.0001]. The mean threshold at MBF for females was 48.9 ± 0.8 dB SPL and for males was 44.3 ± 1.6 dB SPL (Figure 3b, control) with a significant main effect of sex [F(1, 20)= 10.32, p= 0.004]. The mean threshold at HBF for females was 46.0 ± 1.0 dB SPL compared to 46.7 ± 2.1 dB SPL for males (Figure 3c, control) with no main effect of sex [F(1, 20)= 1.158, p= 0.295].

Figure 3.

Threshold at audiogram best frequency. Comparison of females (open circles) and males (filled circles) on threshold at (a) LBF, (b) MBF and (c) HBF. Refer to the results section for statistical comparisons of sex and testosterone effects. Error bars represent SEM.

Relative sensitivities of audiogram peaks

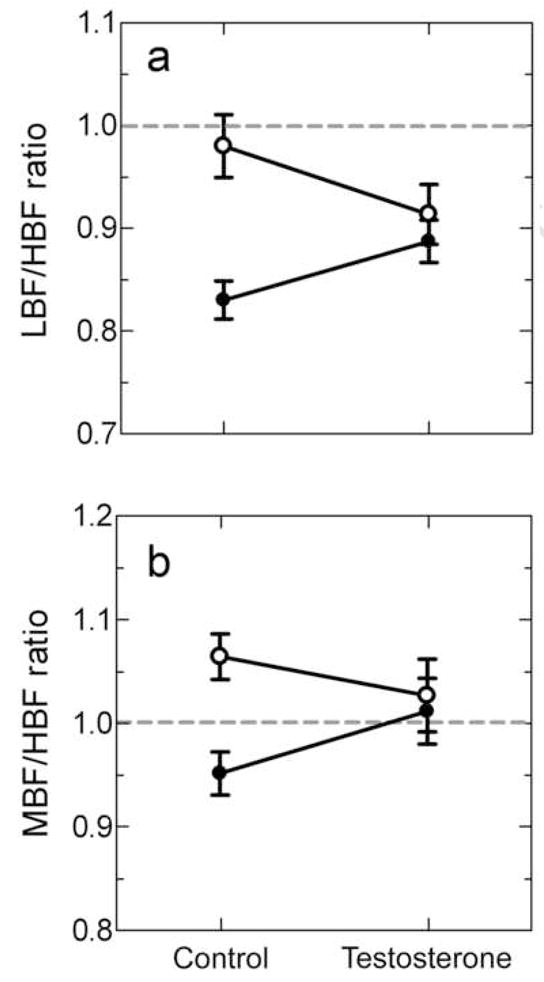

Considering the behavioral relevance of the relative amplitude of the two spectral bands in the male advertisement call, we compared neural thresholds between the corresponding spectral bands. Sex differences in threshold at LBF resulted in males showing a greater sensitivity at LBF compared to HBF and females showing equal sensitivity between the two peaks. The mean LBF/HBF threshold ratio for males was 0.83 ± 0.02 (Figure 4a, control) which was significantly lower than one [one sample t-test, t(6)= 9.181, p < 0.0001]. Threshold at LBF in males was lower by 8.1 ± 1.2 dB SPL compared to threshold at HBF. The mean LBF/HBF threshold ratio in females was 0.98 ± 0.03 (Figure 4a, control) which was not significantly different from 1.0 [one sample t-test, t(6)= 0.6563, p= 0.536]. Directly comparing the LBF/HBF threshold ratio between males and females demonstrated that males had significantly lower ratios than females [Bonferroni post-hoc test, t(20)= 4.540, p = 0.0002].

Figure 4.

The influence of sex and testosterone on relative thresholds at best frequency for (a) LBF/HBF and (b) MBF/HBF. Females are represented by open circles and males by filled circles. The dashed line denotes the null hypothesis of 1.0 and thus no relative difference in sensitivity between the two peaks being compared. Refer to the results section for statistical comparisons of sex and testosterone effects.

Sex differences in threshold at MBF resulted in males showing a greater sensitivity at MBF compared to HBF and females showing less sensitivity at MBF compared to HBF. The mean MBF/HBF threshold ratio for males was 0.95 ± 0.02 which was not statistically different from a ratio of 1.0 [one sample t-test, t(6)= 2.315, p= 0.060] (Figure 4b, control). The threshold at MBF in males was lower by 2.4 ± 1.1 dB SPL compared to threshold at HBF. The mean MBF/HBF threshold ratio in females was 1.06 ± 0.02 which was significantly higher than 1.0 [one sample t-test, t(6)= 2.919, p= 0.027] (Figure 4b, control). The threshold at MBF in females was higher by 2.9 ± 1.0 dB SPL compared to threshold at HBF. Directly comparing the MBF/HBF ratio between males and females demonstrated that males had significantly lower ratios than females [Bonferroni post-hoc test, t(20)= 3.179, p = 0.005].

Audiogram frequencies and the male advertisement call spectral bands

Females had significantly higher thresholds than males at frequencies outside the bands of the advertisement call [one-way MANOVA, F(1,12)=6.94, p=0.022] (Figure 5b, control). Visual inspection of the audiograms shows that females tended to have higher thresholds at the upper and lower ends of the curve but not at the intermediate frequencies (Figure 1b). In contrast, thresholds in response to frequencies within the spectral bands of the male advertisement call were not significantly different between the sexes [one-way MANOVA, F(1,12)=0.13, p=0.720] (Figure 5a, control).

Figure 5.

Mean audiogram thresholds based on advertisement call frequencies. Thresholds are collapsed across frequencies on whether they fall (a) within the bands of the advertisement call or (b) outside the range for females (open circles) and males (filled circles). Refer to the results section for statistical comparisons of sex and testosterone effects.

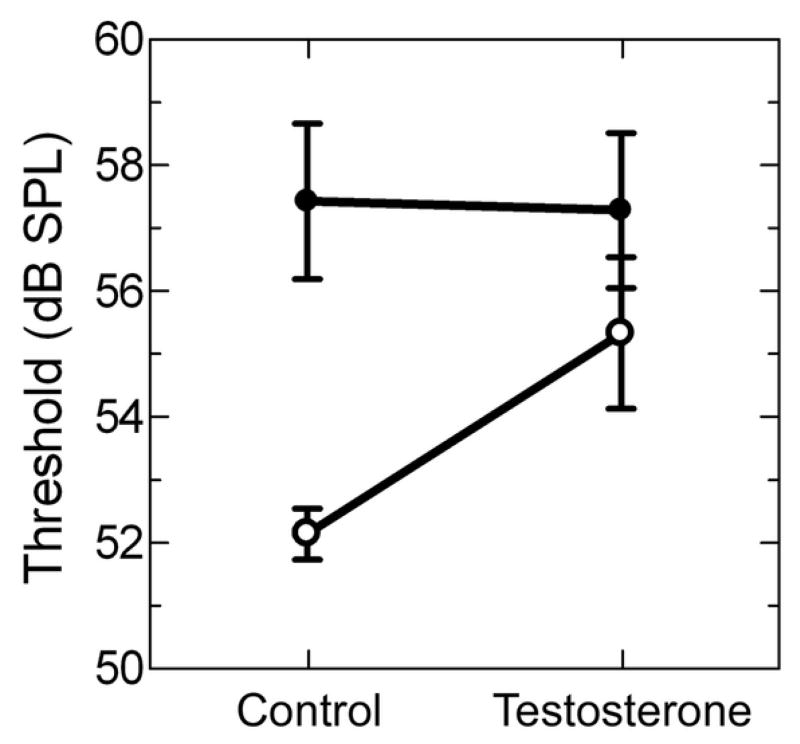

Thresholds to male advertisement call

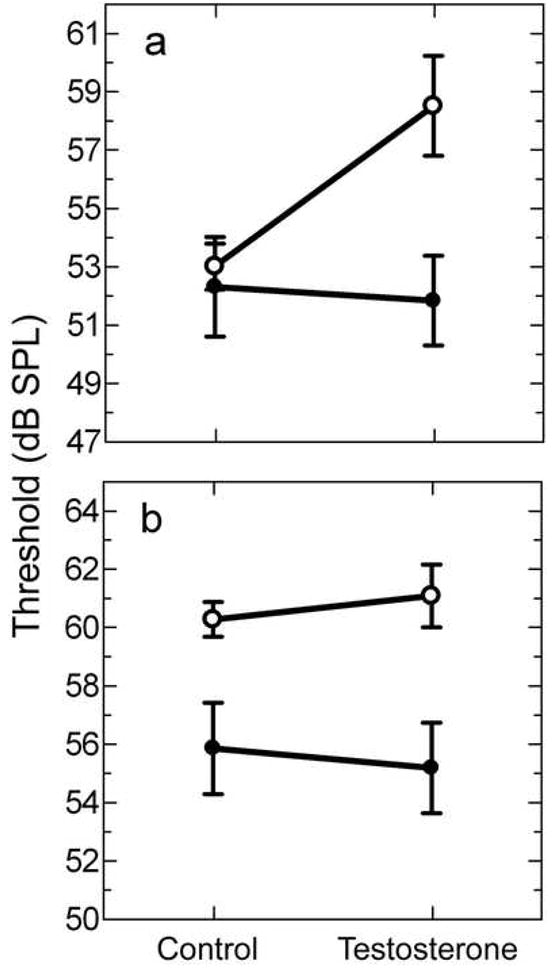

In response to the male advertisement call stimulus, females had significantly lower thresholds than males [Bonferroni post-hoc test, t(12)= 3.706, p= 0.003]. Mean threshold for females was 52.1 ± 0.4 dB SPL compared to 57.4 ± 1.2 dB SPL for males (Figure 6, control).

Figure 6.

Thresholds in response to the male advertisement call for females (open circles) and males (filled circles). Refer to the results section for statistical comparisons of sex and testosterone effects.

Testosterone treatment

Audiogram best frequencies

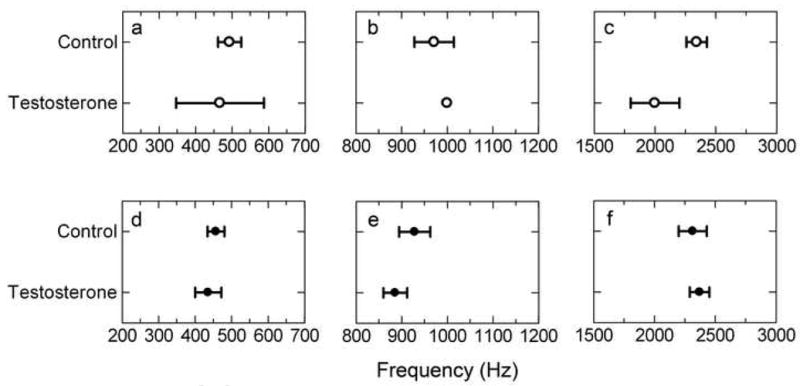

Testosterone had no significant influence on audiogram LBF in either females or males, with no interaction effect [F(1,20)=0.0029, p=0.958] and no overall treatment effect [F(1, 20)=0.2910, p=0.459]. The mean LBF for females treated with testosterone was 467 ± 120 Hz compared to 493 ± 32 Hz for control females (Figure 7a). The mean LBF for males treated with testosterone was 436 ± 36 Hz compared to 457 ± 23 Hz in control males (Figure 7d).

Figure 7.

Audiogram best frequency by testosterone treatment for (a, b, c) females and (d, e, f) males. The three best frequencies are (a, d) LBF, (b, e) MBF and (c, f) HBF.

Testosterone did not significantly influence MBF in either females or males, with no interaction effect [F(1,20)=0.8523, p=0.367] and no overall treatment effect [F(1, 20)= 0.0341, p= 0.855]. The mean MBF for females treated with testosterone was 1000 ± 00 Hz compared to 971 ± 44 Hz for control females (Figure 7b). The mean MBF for males treated with testosterone was 886 ± 26 Hz compared to 929 ± 34 Hz in control males (Figure 7e).

Testosterone did not significantly influence HBF in either males or females, with no significant interaction effect [F(1, 20)= 3.043, p= 0.096] and no treatment effect [F(1, 20)= 1.553, p= 0.227]. Testosterone treated females had a HBF with a mean of 2000 ± 200 Hz compared to 2343 ± 84 Hz for control females (Figure 7c). Males treated with testosterone had a mean HBF of 2371 ± 81 Hz compared to 2314 ± 116 Hz in control males (Figure 7f).

Threshold at audiogram best frequencies

Testosterone did not significantly influence threshold at LBF in either females or males, with no interaction effect [F(1,20)=0.1432, p=0.709] and no overall treatment effect [F(1, 20)= 0.6785, p = 0.420]. The mean threshold at LBF for testosterone-treated females was 45.3 ± 0.9 dB SPL compared to 44.9 ± 0.6 dB SPL for control females (Figure 3a). The mean threshold at LBF for testosterone-treated males was 39.9 ± 1.0 dB SPL compared to 38.6 ± 1.2 dB SPL for control males (Figure 3a).

Testosterone did not significantly influence threshold at MBF in either females or males, with no interaction effect [F(1,20)=0.0887, p=0.769] and no overall treatment effect [F(1, 20) = 0.9574, p = 0.340]. The mean threshold at MBF for testosterone-treated females was 51.0 ± 2.0 dB SPL compared to control females with 48.9 ± 0.8 dB SPL (Figure 3b). The mean threshold at MBF for testosterone-treated males was 45.4 ± 1.8 dB SPL compared to control males with 44.3 ± 1.6 dB SPL (Figure 3b).

Testosterone did not significantly influence threshold at HBF in either females or males with no interaction effect [F(1,20)=2.146, p=0.158] and no overall treatment effect [F(1, 20) = 0.2826, p= 0.601]. The mean threshold at HBF for testosterone-treated females was 49.7 ± 0.7 dB SPL and for control females was 46.0 ± 1.0 dB SPL (Figure 3c). The mean threshold at HBF for testosterone-treated males was 45.0 ± 1.7 dB SPL and for control males was 46.7 ± 2.1 dB SPL (Figure 3c).

Relative sensitivities of audiogram peaks

Testosterone influenced the LBF/HBF threshold ratio in a sex specific manner as supported by a significant interaction effect between sex and testosterone [F(1,20)=5.266, p=0.033] (Figure 4a). The interaction effect was due to a small, non-significant decrease in the ratio in females and a small non-significant increase in the ratio in males. First, testosterone did not significantly influence the ratio in females. Testosterone-treated females had a mean LBF/HBF threshold ratio of 0.91 ± 0.03 compared to the control mean of 0.98 ± 0.03 [Bonferroni post-hoc test, t(20)= 1.564, p= 0.134]. Testosterone-treated females had a mean ratio that was not statistically different from 1.0 [one sample t-test, t(2)= 2.982, p= 0.096]. The threshold at LBF in females treated with testosterone was lower by 4.3 ± 1.5 dB SPL compared to threshold at HBF. The mean LBF/HBF threshold ratio in males treated with testosterone was 0.89 ± 0.02, and was not statistically different from the control mean of 0.83 ± 0.02 [Bonferroni post test, t(20)= 1.728, p= 0.099]. The mean LBF/HBF ratio in testosterone-treated males remained significantly lower than 1.0 [one sample t-test, t(6)= 5.460, p= 0.002]. The threshold at LBF in males treated with testosterone was lower by 5.1 ± 1.1 dB SPL compared to threshold at HBF.

Testosterone did not influence the MBF/HBF threshold ratio in either males or females with no interaction effect [F(1,20)=2.836, p=0.108] and no overall treatment effect [F(1,20)=0.1491, p=0.704] (Figure 4b). Testosterone-treated females had a mean MBF/HBF threshold ratio of 1.03 ± 0.04 compared to the control mean of 1.06 ± 0.02. MBF/HBF threshold ratio in testosterone treated females was not statistically different from 1.0 [one sample t-test, t(2)= 0.756, p= 0.529]. The mean MBF/HBF threshold ratio in males treated with testosterone was 1.01 ± 0.03 compared to the control mean of 0.95 ± 0.02.

Audiogram frequencies and the male advertisement call spectral bands

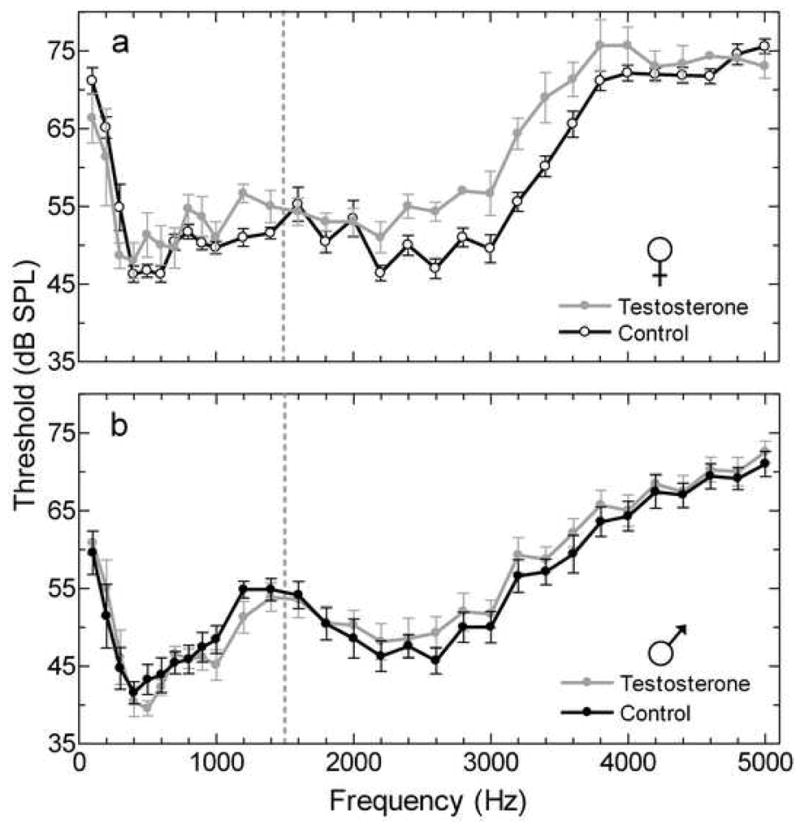

Testosterone treatment influenced audiograms in a sex and frequency dependent manner (Figure 8). For frequencies corresponding to the spectral bands of the male advertisement call, females treated with testosterone had significantly elevated thresholds compared to control females [one-way MANOVA, F(1,8)=11.59, p=0.009] (Figure 5a). Thresholds in males treated with testosterone were not significantly different from control males [one-way MANOVA, F(1,12)=0.04, p=0.838] (Figure 5a). Testosterone treatment did not influence thresholds for frequencies outside the bands of the advertisement call in either males or females, with no interaction effect [F(1,20)=.25, p=0.621] and no overall effect of testosterone [F(1,20)=.002, p=0.964] (Figure 5b).

Figure 8.

Multiunit audiograms from the TS comparing control and testosterone treatment in (a) females and (b) males. The dashed line divides the AP and BP range of frequencies.

Thresholds to male advertisement call

For thresholds in response to the male advertisement call we found no significant interaction between sex and testosterone treatment [F(1,20)=2.044, p=0.168] and no overall effect of testosterone [F(1,20)=1.709, p=0.206]. Females treated with testosterone had a mean threshold of 55.3 ± 1.2 dB SPL compared to the control mean of 52.1 ± 0.4 dB SPL. The mean threshold for males treated with testosterone was 57.3 ± 1.2 dB SPL compared to 57.4 ± 1.2 dB SPL for the control condition (Figure 6). Despite the lack of a significant sex by testosterone interaction effect, testosterone treatment did elevate female thresholds such that they were not significantly different from control males [Bonferroni post test, t(8)= 1.139, p=0.288].

Discussion

Sex differences

Our first goal for this study was to determine whether male and female H. cinerea differed in neural sensitivity to auditory stimuli. We tested whether sex differences to pure tones were frequency-dependent. Our results demonstrate sex differences in the relative sensitivities of the spectral peaks and in the sensitivity to frequencies outside the spectral bands of the advertisement call. Sex differences are also stimulus-dependent such that differences in response to pure tones do not predict the differences to the natural advertisement call.

Previous studies reported sex differences in the BP BEF from single units in the VIIIth nerve in other species, but we see no evidence of a related difference in H. cinerea at the level of the TS. The previous report of consistent tuning in peak sensitivities between responses from the VIIIth nerve and the TS in H. cinerea (Lombard and Straughan, 1974), suggest that if sex differences occurred in the peripheral auditory system we would expect to see them represented in the responses from the TS. For other species examined, females have BP units tuned to a lower frequency than males and the difference is associated with a large dimorphism in snout-vent length, with females larger than males (McClelland et al., 1997; Narins and Capranica, 1976). As demonstrated previously (Garton and Brandon, 1975) and in this study, H. cinerea has a statistically significant but relatively small size dimorphism with males larger than females. The lack of a large size dimorphism in H. cinerea may account for a similar HBF in males and females. Consistent with our results, H. microcephala has a relatively small size dimorphism and also has no sex difference in BP tuning (McClelland et al., 1997).

At the level of the TS, H. cinerea has been reported to be more sensitive at the LBF and MBF compared to the HBF (Lombard and Straughan, 1974) but our results demonstrate that this is only true for males. Multiunit thresholds to pure tones at the audiogram sensitivity peaks demonstrate that males are more sensitive than females at the two peaks that fall within the AP range of frequencies (LBF and MBF) but not at the peak in the BP range (HBF). The differences in thresholds result in a sex difference in the relative sensitivities between the AP and BP range of frequencies. The male advertisement call contains spectral bands that fall within each of these frequency ranges which suggests that the resulting neural representation of the call may differ between males and females.

Strong sex differences emerge when the multiunit audiogram is considered in terms of the prominent frequencies in the natural vocalization of the species. Females are less sensitive than males in response to frequencies that fall outside the spectral bands of the male advertisement call. For frequencies that fall within the bands of the male advertisement call no sex difference is evident. We must note that harmonic frequency structure in the male advertisement calls do fall outside the peak bands, as defined in this study and elsewhere (Gerhardt, 1974), but are generally attenuated compared to the peak components. In addition, synthetic models of the male advertisement call that contain only the peak frequencies, with no attenuated harmonic structure, are recognizable and just as attractive to females as the natural call with harmonic structure (Gerhardt, 1974). Our results then suggest that, in response to pure-tone stimuli, sex differences are limited to particular frequency bands that are unlikely to be involved in the processing of communication signals.

Sex differences in multiunit thresholds are also stimulus-dependent. In contrast to the lack of a sex difference in response to pure tones within the spectral bands of the advertisement call, a sex difference emerges in response to the naturally recorded advertisement call such that females are more sensitive to the behaviorally relevant stimulus. This may be the result of stimulus-dependent response properties of subsets of cells within the TS such as those exhibited in Rana pipiens (Rose and Capranica, 1983; Rose and Capranica, 1985). A single unit analysis could attempt to test whether the stimulus-dependent sex differences in this study are due to the response properties of individual cells or an emergent property of a network of cells within the TS.

Testosterone influences

Our second goal for this study was to determine whether circulating testosterone levels influence neural sensitivity to auditory stimuli in male and female H. cinerea. In females, testosterone influences multiunit thresholds in both a frequency-dependent, and a stimulus-dependent manner, but we find no evidence that the same is true for males.

Despite the lack of evidence for a shift in thresholds at any of the sensitivity peaks in testosterone-treated animals (figure 3), subtle changes resulted in shifts in the relative sensitivities between the MBF peak and the HBF peak in females. With these small shifts, thresholds at MBF no longer differed from thresholds at HBF (figure 4). The relative amplitude of the two spectral bands of the male advertisement call does influence female behavior (Gerhardt, 1974; Gerhardt, 1976) and a steroid induced shift in the relative sensitivity to those bands may therefore have behavioral consequences. The magnitude of the shifts is small, but suggests a behavioral recognition study would be useful to determine whether these shifts in MBF/HBF ratios result in testosterone related shifts in recognition of the advertisement call.

For males, testosterone did not influence audiogram thresholds, regardless of whether the test frequencies fall within or outside the spectral bands of the male advertisement call (figure 5). The lack of an influence of testosterone manipulation on neural thresholds in males is consistent with results reported previously for multiunit audiograms in Hyla cinerea (Penna et al., 1992) where testosterone treatment had no effect in castrated males. However, in the previous study, gonad removal without steroid replacement did influence audiogram thresholds suggesting that testosterone may require the presence of other gonadal steroids to influence thresholds in males. Our results do not support this prediction given that we manipulated testosterone levels in the presence of gonads and see no effect on thresholds.

In females, testosterone significantly increased audiogram thresholds for frequencies corresponding to the spectral bands of the male advertisement call but not for those frequencies outside the advertisement call bands (figure 5). This demonstrates that for thresholds to pure-tone stimuli, testosterone influences are limited to spectral bands that are likely to be involved in processing communication signals. This result is in contrast to a previous study that demonstrated no influence of testosterone on thresholds in females (Penna et al., 1992). The previous study did not report testosterone levels and therefore we do not know if a difference in the effectiveness of the testosterone treatment may explain the different results. Moreover, the testosterone levels achieved by implants in this study may be higher than the physiological range for this species (Burmeister and Wilczynski, 2000) although natural levels from animals in the field are not known. Natural circulating testosterone levels vary widely both among anuran species and within species across breeding conditions. For example female Rana esculenta have a range of approximately 0.75 – 5 ng/ml (Gobbetti and Zerani, 1999) whereas female Bufo arenarum have a range of approximately 5 – 230 ng/ml (Medina et al., 2004). The same can be said for male Rana blythi (Emerson and Hess, 1996) and Scaphiopus couchii (Harvey et al., 1997). Future studies on the dose dependence of the testosterone effects found in this study could clarify the functional role of these changes in the context of the natural breeding cycle of the female.

The influence of testosterone on auditory thresholds in the TS leads to questions about its site of action within the auditory system. Responses in the TS represent the function of lower auditory nuclei and therefore may be an indication of sex differences and hormone action earlier in the auditory pathway. Considering the presence of steroid receptors within the TS (Dimeglio et al., 1987; Guerriero et al., 2005; Kelley, 1980) and previous data demonstrating sex differences in VIIIth nerve responses (discussed above) and otoacoustic emissions (Vassilakis et al., 2004) of several anuran species, it is likely that the results of this study are a combination of effects within the TS and earlier processing centers including hair cells of the ear.

Suggestions for behavioral significance

Auditory processing in the TS is important in perception and phonotactic behavior suggesting that sex differences revealed in this study would influence auditory evoked behavior. Behavioral audiograms, using the modified reflex response, match closely to the multiunit audiograms recorded from the Hyla cinerea TS, demonstrating the perceptual relevance of neural thresholds at this level of the brain (Megela-Simmons et al., 1985). Additionally, lesions of the TS in Hyla versicolor eliminate phonotactic behavior in two-alternative choice tests while extensive thalamic lesions do not (Endepols et al., 2003).

A sex difference in the relative sensitivities between the AP and BP range of frequencies may influence how we currently understand behavioral responses to the advertisement call in this species. Gerhardt (1974) demonstrated that, behaviorally, females are sensitive to the relative amplitudes of the spectral bands of the male advertisement call. In two-alternative choice tests, a synthetic call with a relative amplitude difference of as little as 10 dB SPL between the low and high frequency bands rendered the call less attractive compared to calls with smaller differences.

Complementary tests in males have not been reported. The results of the current study suggest that males may perform differently on a similar type of behavioral task. In addition, the relative amplitudes of the two bands of the advertisement call attenuate differentially over distance and this factor influences discrimination behavior in females (Gerhardt, 1976) but the influence in males is not known.

Higher neural thresholds to frequencies outside the bands of the male advertisement call in female H. cinerea suggest that, in a noisy environment, the female auditory system may filter out frequencies that would interfere with the detection and discrimination of the communication signal. Broadband noise does influence behavioral responses in female H. cinerea (Ehret and Gerhardt, 1980). Likewise, behavioral evidence in females of another Hylid species, H. ebraccata, suggests that the natural noise of a chorus does indeed impair detection and discrimination (Wollerman, 1999; Wollerman and Wiley, 2002). Experiments comparing males and females on these tasks are needed to test the behavioral implications of audiogram sex differences.

Evidence in another frog species is consistent with the effects of testosterone on female thresholds in this study. In female Physalaemus pustulosus, testosterone levels are highest just prior to the expression of maximal levels of reproductive behavior and testosterone levels are low when reproductive behavior levels become high (Lynch and Wilczynski, 2005; Lynch et al., 2005). Behavioral examination of testosterone influence on signal detection in a noisy environment is necessary to test whether testosterone effects on behavior result from the signal detection changes shown in our study. Our data, together with evidence from other anuran species and other taxa, support the hypothesis that reproductive hormones provide a functional means to modulate auditory processing of communication signals in a context dependent manner.

Acknowledgments

We thank Allison Tannenbaum and Ed Pasanen for technical advice, Greg Hixon for statistical advice and Glennis Julian for assistance with hormone analysis. We also thank Lynn Almli, Alexander Baugh, Tomoko Hattori, Glennis Julian and Kim Hoke for comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. This research was supported by NIGMS F31 GM66547 (JAM) and NIH RO1 MH057066 (WW).

List of abbreviations

- AP

amphibian papilla

- BP

basilar papilla

- BEF

best excitatory frequency

- EIA

enzyme immunoassay

- HBF

high best frequency

- LBF

low best frequency

- MBF

mid best frequency

- SVL

snout-vent length

- TS

torus semicircularis

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Cited References

- Ball GF, Riters LV, Balthazart J. Neuroendocrinology of song behavior and avian brain plasticity: Multiple sites of action of sex steroid hormones. Front Neuroendocrin. 2002;23:137–178. doi: 10.1006/frne.2002.0230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burmeister S, Wilczynski W. Social signals influence hormones independently of calling behavior in the treefrog (Hyla cinerea) Horm Behav. 2000;38:201–209. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2000.1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burmeister SS, Wilczynski W. Social context influences androgenic effects on calling in the green treefrog (Hyla cinerea) Horm Behav. 2001;40:550–558. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2001.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeglio M, Morrell JI, Pfaff DW. Localization of steroid-concentrating cells in the central nervous system of the frog Rana esculenta. Gen Comp Endocr. 1987;67:149–154. doi: 10.1016/0016-6480(87)90142-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehret G, Gerhardt HC. Auditory masking and effects of noise on responses of the green treefrog (Hyla cinerea) to synthetic mating calls. J Comp Physiol. 1980;141:13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson SB, Hess DL. The role of androgens in opportunistic breeding, tropical frogs. Gen Comp Endocr. 1996;103:220–230. doi: 10.1006/gcen.1996.0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endepols H, Feng AS, Gerhardt HC, Schul J, Walkowiak W. Roles of the auditory midbrain and thalamus in selective phonotaxis in female gray treefrogs (Hyla versicolor) Behav Brain Res. 2003;145:63–77. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(03)00098-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng AS, Ratnam R. Neural basis of hearing in real-world situations. Annu Rev Psychol. 2000;51:699–725. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garton JS, Brandon RA. Reproductive ecology of the green treefrog, Hyla cinerea, in Southern Illinois (Anura: Hylidae) Herpetologica. 1975;31:150–161. [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt HC. MA Thesis. The University of Texas at Austin; Austin, Texas: 1968. Evolutionary aspects of vocal communication and reproductive behavior in the Hyla cinerea species group. [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt HC. The significance of some spectral features in mating call recognition in the green treefrog (Hyla cinerea) J Exp Biol. 1974;61:229–41. doi: 10.1242/jeb.61.1.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt HC. Significance of two frequency bands in long distance vocal communication in the green treefrog. Nature. 1976;261:692–694. [Google Scholar]

- Gobbetti A, Zerani M. Hormonal and cellular brain mechanisms regulating the amplexus of male and female water frog (Rana esculenta) J Neuroendocrinol. 1999;11:589–596. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1999.00369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goense JBM, Feng AS. Seasonal changes in frequency tuning and temporal processing in single neurons in the frog auditory midbrain. J Neurobiol. 2005;65:22–36. doi: 10.1002/neu.20172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerriero G, Prins GS, Birch L, Ciarcia G. Neurodistribution of androgen receptor immunoreactivity in the male frog, Rana esculenta. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2005;1040:332–336. doi: 10.1196/annals.1327.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey LA, Propper CR, Woodley SK, Moore MC. Reproductive endocrinology of the explosively breeding desert spadefoot toad, Scaphiopus couchii. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 1997;105:102–113. doi: 10.1006/gcen.1996.6805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillery CM. Seasonality of two midbrain auditory responses in the treefrog, Hyla chrysoscelis. Copeia. 1984:844–852. [Google Scholar]

- Hoke KL, Ryan MJ, Wilczynski W. Candidate neural locus for sex differences in reproductive decisions. Biol Lett. 2008;4:518–521. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2008.0192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keddy-Hector AC, Wilczynski W, Ryan MJ. Call patterns and basilar papilla tuning in cricket frogs. II Intrapopulation variation and allometry. Brain Behav Evolut. 1992;39:238–246. doi: 10.1159/000114121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley DB. Auditory and vocal nuclei in the frog brain concentrate sex hormones. Science. 1980;207:553–555. doi: 10.1126/science.7352269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombard RE, Straughan IR. Functional aspects of anuran middle ear structures. J Exp Biol. 1974;61:71–93. doi: 10.1242/jeb.61.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch KS, Wilczynski W. Gonadal steroids vary with reproductive stage in a tropically breeding female anuran. Gen Comp Endocr. 2005;143:51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2005.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch KS, Wilczynski W. Social regulation of plasma estradiol concentration in a female anuran. Horm Behav. 2006;50:101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch KS, Rand AS, Ryan MJ, Wilczynski W. Plasticity in female mate choice associated with changing reproductive states. Anim Behav. 2005;69:689–699. [Google Scholar]

- McClelland BE, Wilczynski W, Rand AS. Sexual dimorphism and species differences in the neurophysiology and morphology of the acoustic communication system of two neotropical hylids. J Comp Physiol A. 1997;180:451–462. doi: 10.1007/s003590050062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina MF, Ramos L, Crespo CA, Gonzalez-Calvar S, Fernandez SN. Changes in serum sex steroid levels throughout the reproductive cycle of Bufo arenarum females. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2004;136:143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2003.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megela-Simmons A, Moss CF, Daniel KM. Behavioral audiograms of the bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana) and the green treefrog (Hyla cinerea) J Acoust Soc Am. 1985;78:1236–1244. doi: 10.1121/1.392892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narins PM, Capranica RR. Sexual differences in the auditory system of the tree frog Eleutherodactylus coqui. Science. 1976;192:378–380. doi: 10.1126/science.1257772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penna M, Capranica RR, Somers J. Hormone-induced vocal behavior and midbrain auditory sensitivity in the green treefrog, Hyla cinerea. J Comp Physiol A. 1992;170:73–82. doi: 10.1007/BF00190402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose G, Capranica RR. Temporal selectivity in the central auditory system of the leopard frog. Science. 1983;219:1087–1089. doi: 10.1126/science.6600522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose GJ, Capranica RR. Sensitivity to amplitude modulated sounds in the anuran auditory nervous system. J Neurophysiol. 1985;53:446–65. doi: 10.1152/jn.1985.53.2.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose GJ, Gooler DM. Function of the amphibian central auditory system. In: Narins PM, Feng AS, Fay RR, Popper AN, editors. Hearing and Sound Communication in Amphibians. Vol. 28. Springer; New York: 2007. pp. 250–290. [Google Scholar]

- Shofner WP, Feng AS. Post-metamorphic development of the frequency selectivities and sensitivities of the peripheral auditory system of the bullfrog, Rana catesbeiana. J Exp Biol. 1981;93:181–196. [Google Scholar]

- Sisneros JA, Forlano PM, Deitcher DL, Bass AH. Steroid-dependent auditory plasticity leads to adaptive coupling of sender and receiver. Science. 2004;305:404–407. doi: 10.1126/science.1097218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smotherman MS, Narins PM. Hair cells, hearing and hopping: A field guide to hair cell physiology in the frog. J Exp Biol. 2000;203:2237–2246. doi: 10.1242/jeb.203.15.2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard PK, Zakon HH, Markham MR, McAnelly L. Regulation and modulation of electric waveforms in gymnotiform electric fish. J Comp Physiol A. 2006;192:613–624. doi: 10.1007/s00359-006-0101-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassilakis PN, Meenderink SWF, Narins PM. Distortion product otoacoustic emissions provide clues to hearing mechanisms in the frog ear. J Acoust Soc Am. 2004;116:3713–3726. doi: 10.1121/1.1811571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walkowiak W. The coding of auditory signals in the torus semicircularis of the fire-bellied toad and the grass frog - Responses to simple stimuli and to conspecific calls. J Comp Physiol. 1980;138:131–148. [Google Scholar]

- Wilczynski W, Capranica RR. The auditory system of anuran amphibians. Prog Neurobiol. 1984;22:1–38. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(84)90016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilczynski W, Endepols H. Central auditory pathways in anuran amphibians: The anatomical basis of hearing and sound communication. In: Narins PM, Feng AS, Fay RR, Popper AN, editors. Hearing and sound communication in amphibians. Vol. 28. Springer; New York: 2007. pp. 221–249. [Google Scholar]

- Wilczynski W, Zakon HH, Brenowitz EA. Acoustic communication in spring peepers - Call characteristics and neurophysiological aspects. J Comp Physiol. 1984;155:577–584. [Google Scholar]

- Wilczynski W, Keddy-Hector AC, Ryan MJ. Call patterns and basilar papilla tuning in cricket frogs. I Differences among populations and between sexes. Brain Behav Evolut. 1992;39:229–237. doi: 10.1159/000114120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilczynski W, McClelland BE, Rand AS. Acoustic, auditory, and morphological divergence in three species of neotropical frog. J Comp Physiol A. 1993;172:425–438. doi: 10.1007/BF00213524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilczynski W, Lynch KS, O’Bryant EL. Current research in amphibians: Studies integrating endocrinology, behavior, and neurobiology. Horm Behav. 2005;48:440–450. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollerman L. Acoustic interference limits call detection in a Neotropical frog Hyla ebraccata. Anim Behav. 1999;57:529–536. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1998.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollerman L, Wiley RH. Background noise from a natural chorus alters female discrimination of male calls in a Neotropical frog. Anim Behav. 2002;63:15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Woolley SMN, Gill PR, Theunissen FE. Stimulus-dependent auditory tuning results in synchronous population coding of vocalizations in the songbird midbrain. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2499–2512. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3731-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yovanof S, Feng AS. Effects of estradiol on auditory evoked responses from the frog’s auditory midbrain. Neurosci Lett. 1983;36:291–297. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(83)90015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakon HH. Hormone-mediated plasticity in the electrosensory system of weakly electric fish. Trends Neurosci. 1987;10:416–421. [Google Scholar]