Abstract

Objectives

We sought to determine the association between body morphology abnormalities and depression examining lipoatrophy and lipohypertrophy separately.

Methods

Observational cross-sectional study of 250 patients from the University of Washington HIV Cohort. Patients completed an assessment including depression and body morphology. We used linear regression analysis to examine the association between lipoatrophy, lipohypertrophy, and depression. ANOVA was used to examine the relationship between mean depression scores and lipoatrophy and lipohypertrophy in 10 body regions.

Results

Of 250 patients, 76 had lipoatrophy, and 128 had lipohypertrophy. Mean depression scores were highest among patients with moderate-to-severe lipoatrophy (16.4), intermediate among those with moderate-to-severe lipohypertrophy (11.7), mild lipohypertrophy (9.9), and mild lipoatrophy (8.5), and lowest among those without body morphology abnormalities (7.7) (p=0.002). After adjustment, mean depression scores for subjects reporting moderate-to-severe lipoatrophy were 9.2 points higher (p<0.001), scores for subjects with moderate-to-severe lipohypertrophy were 4.8 points higher (p=0.02), and scores for subjects with mild lipohypertrophy were 2.8 points higher (p=0.03) than patients without body morphology abnormalities. Facial lipoatrophy was the body region associated with the most severe depression scores (15.5 versus 8.9 for controls, p=0.03).

Conclusions

In addition to long-term cardiovascular implications, body morphology has a more immediate effect on depression severity.

Keywords: Lipoatrophy, lipohypertrophy, lipodystrophy, depression, HIV

INTRODUCTION

The dramatic decline in HIV-related mortality due to combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) has led to unexpected abnormalities in fat distribution such as lipoatrophy and lipohypertrophy (8, 34), commonly grouped under the term lipodystrophy. Studies suggest that lipodystrophy may have a detrimental impact on sexual behavior, self-esteem, and general well-being (12, 15, 28). The few studies that assessed lipodystrophy and depression reported mixed results; some found an association between lipodystrophy and depression (22, 28), others did not (7, 31). Although lipoatrophy and lipohypertrophy are often conceptualized as a single disorder, they are distinct entities with different etiologies (3, 13). Prior studies have not examined the independent association between lipoatrophy or lipohypertrophy with depression severity among patients in clinical care. We conducted this study to examine the associations between lipoatrophy, lipohypertrophy, and depression.

METHODS

Study setting

This cross-sectional study was conducted among a convenience sample of patients in the University of Washington (UW) HIV Cohort, a longitudinal observational study of HIV-infected patients who receive primary care in the UW Harborview Medical Center HIV Clinic. This study was approved by the UW Institutional Review Board.

Study participants

HIV-infected patients over 18 years of age who attended the clinic between 9/26/2005 and 6/01/2006 were eligible for the study. We did not exclude patients who were receiving antidepressant medications.

Data sources

Patients used tablet PCs with touch screens to complete an assessment including measures of depression (Patient Health Questionnaire from the PRIME-MD) (18, 29), drug use (Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test) (26, 35), and lipoatrophy and lipohypertrophy (based on the Study of Fat Redistribution and Metabolic Change instrument) (3, 13, 14, 33). As previously described (10), we used web-based survey software developed specifically for patient-based measures.

Data were also obtained from the UW HIV Information System (UWHIS). UWHIS integrates comprehensive clinical data on the UW HIV cohort from all outpatient and inpatient encounters including demographic, clinical, laboratory, medication, and socioeconomic information.

Instrument Scoring

For the depression instrument, patients indicate for each of 9 depressive symptoms whether, during the prior 2 weeks, the symptom bothered them “not at all,” “several days,” “more than half the days,” or “nearly every day.” We scored it as a severity measure with scores ranging from 0 to 27. We also categorized depression severity as: none (0-4 points), mild (5-9 points), moderate (10-19 points), and severe (≥20 points) (18, 29).

There are several ways of scoring the Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (26, 35). Because of the association between drug use and depression (5, 32), we were interested in current drug use (within 3 months).

The body morphology instrument asks patients to rate changes in the amount of fat in specific body regions graded on a 7-point scale ranging from -3 to +3 for each region. No change was scored as 0; mild, moderate, and severe increases were scored as +1, +2, and +3; and mild, moderate, and severe decreases were scored as -1, -2, and -3. An overall lipohypertrophy score was calculated totaling all positive responses (indicating increases in size of body regions). An overall lipoatrophy score was calculated totaling all negative responses (indicating decreases in size). Severity of each condition was defined as none (0 points), mild (1-12 points), and moderate-to-severe (>12 points). Patients with both lipoatrophy and lipohypertrophy were categorized by the more severe abnormality.

Statistical analyses

We performed bivariate analyses comparing study participant characteristics to the overall UW HIV cohort using chi-squared tests and t-tests. Among subjects, we examined associations between depression, body morphology abnormalities, demographic characteristics (age, race, sex, risk factor for HIV transmission), and clinical characteristics (CD4+ cell count nadir, current CD4+ cell count, peak HIV-1 RNA level, current cART use, BMI category, and current illicit drug use). We calculated BMI using the traditional Quetelet index: weight divided by height squared (kg/m2) (1). BMI was categorized as underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal (18.5-24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25-29.9 kg/m2), and obese (≥30 kg/m2). We performed bivariate analyses of associations with depression scores using t-tests. We used one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to examine the relationship between mean depression scores and any lipoatrophy or lipohypertrophy compared with no abnormality in each of 10 body regions, and moderate-to-severe abnormalities compared with no abnormality. Pairwise comparisons were performed for statistically significant factors. We used multivariate linear regression with depression scores as the dependent variable to examine associations between depression and lipoatrophy and lipohypertrophy in adjusted analyses. We determined the amount of variance explained by lipoatrophy and lipohypertrophy by subtracting the adjusted R2 from models excluding them from the adjusted R2 of the full model. Two-tailed p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The assessment was completed by 250 patients. Mean age of subjects was 43 years, 86% were men, and mean CD4+ count nadir was 169 cells/mm3 (Table 1). Demographic and clinical characteristics of subjects were similar to those of all UW HIV cohort patients in the study period (data not shown).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of study patients (N=250)

| Characteristic | No body morphology abnormalities N=46 |

Mild lipohypertrophy N=106 |

Mild lipoatrophy N=65 |

Moderate-to-severe lipohypertrophy N=22 |

Moderate-to-severe lipoatrophy N=11 |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 41 (89) | 93 (88) | 56 (86) | 15 (68) | 10 (91) | |

| Female | 5 (11) | 13 (12) | 9 (14) | 7 (32) | 1 (9) | 0.15 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 30 (65) | 68 (64) | 46 (71) | 14 (64) | 10 (91) | |

| Black | 11 (24) | 23 (22) | 13 (20) | 8 (36) | 1 (9) | |

| Hispanic | 4 (9) | 9 (8) | 4 (6) | 0 | 0 | |

| Other/Unknown | 1 (2) | 6 (6) | 2 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0.6 |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| < 30 | 9 (20) | 4 (4) | 6 (9) | 0 | 0 | |

| 30-39 | 14 (30) | 34 (32) | 13 (20) | 7 (32) | 2 (18) | |

| 40-49 | 18 (39) | 43 (41) | 26 (40) | 12 (55) | 6 (55) | |

| ≥50 | 5 (11) | 25 (24) | 20 (31) | 3 (14) | 3 (27) | 0.03 |

| Risk factor for HIV transmission | ||||||

| Male sex-with-male | 28 (61) | 58 (55) | 36 (55) | 12 (55) | 6 (55) | |

| Injection drug use | 12 (26) | 30 (28) | 14 (22) | 3 (14) | 3 (27) | |

| Heterosexual | 6 (13) | 17 (16) | 10 (15) | 6 (27) | 1 (9) | |

| Other/unknown | 0 | 1 (1) | 5 (8) | 1 (5) | 1 (9) | 0.4 |

| Current CD4R+cell count (cells/mm3) | ||||||

| 0-200 | 12 (26) | 22 (21) | 15 (23) | 2 (9) | 6 (55) | |

| 201-350 | 16 (35) | 27 (25) | 12 (18) | 7 (32) | 3 (27) | |

| 351 or greater | 18 (39) | 57 (54) | 38 (58) | 13 (59) | 2 (18) | 0.06 |

| Currently receiving HAART | ||||||

| Yes | 27 (59) | 79 (75) | 54 (83) | 21 (95) | 9 (82) | |

| No | 19 (41) | 27 (25) | 11 (17) | 1 (5) | 2 (18) | 0.007 |

Only 46 subjects (18%) reported no lipoatrophy or lipohypertrophy, 106 (42%) reported mild lipohypertrophy, 65 (26%) reported mild lipoatrophy, 22 (9%) reported moderate-to-severe lipohypertrophy, and 11 (4%) reported moderate-to-severe lipoatrophy. There were 4 subjects who had moderate-to-severe lipoatrophy concurrent with mild lipohypertrophy, and 8 who had moderate-to-severe lipohypertrophy concurrent with mild lipoatrophy. These 12 subjects are classified according to their more severe body morphology abnormality. In addition, 75 subjects had both mild lipohypertrophy and mild lipoatrophy. These individuals are classified according to which mild abnormality was more severe. The mean depression score was 9.6, corresponding to mild-to-moderate depression: 72 (29%) had no depression, 70 (28%) mild depression, 82 (33%) moderate depression, and 26 (10%) severe depression.

Patients reporting any body morphology abnormality (lipoatrophy or lipohypertrophy) had higher mean depression scores than patients without body morphology abnormalities (10.0 versus 7.7, p=0.046 t-test). Mean depression scores varied among patients reporting different body morphology abnormalities (Figure 1), with the highest values among patients with moderate-to-severe lipoatrophy (16.4), intermediate values among those with moderate-to-severe lipohypertrophy (11.7), mild lipohypertrophy (9.9), and mild lipoatrophy (8.5), and the lowest values among those without body morphology abnormalities (7.7) (p=0.002, ANOVA).

Figure 1.

Mean depression score by body morphology

Overall p value for one-way analysis of variance examining the relationship between mean depression scores and body morphology abnormalities was 0.002.

* p values for pairwise comparisons for each body morphology abnormality versus None (no reported body morphology abnormalities).

Multivariate analyses

The relationship between body morphology abnormalities and depression remained after controlling for age, race, sex, cART use, BMI category, current drug use, and current CD4+ cell count. After adjustment, mean depression scores for subjects reporting moderate-to-severe lipoatrophy were 9.2 points higher (p<0.001, linear regression), while scores for subjects with moderate-to-severe lipohypertrophy were 4.8 points higher (p=0.02) than those without body morphology abnormalities. Scores for subjects with mild lipohypertrophy were only 2.8 points higher (p=0.03) than those without abnormalities. Scores for those with mild lipoatrophy were not significantly different from those without abnormalities.

Overall, the fully adjusted model, including lipoatrophy and lipohypertrophy severity scores, explained 7.3% of the variance in depression. Lipohypertrophy and lipoatrophy scores explained 5.4% of the variance, thus 74% of the variance explained by the full model was attributable to lipoatrophy and lipohypertrophy. In contrast, current CD4+ cell count accounted for only 2.3% of the variance of depression.

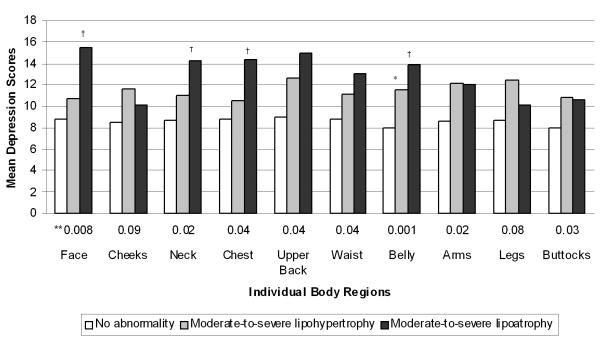

Individual body regions

We examined depression scores associated with regional body morphology abnormalities for patients reporting moderate-to-severe lipoatrophy or lipohypertrophy for each region compared with patients reporting no changes (Figure 2). We found mean depression scores for patients with moderate-to-severe lipoatrophy or lipohypertrophy were higher compared with those without changes, and these differences were statistically significant by overall one-way ANOVA (p values 0.001-0.04) for all regions except cheeks (p=0.09) and legs (p=0.08).

Figure 2.

Mean depression scores by body region

**Overall p values from one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for patients with moderate-to-severe lipohypertrophy, moderate-to-severe lipoatrophy, or no body morphology abnormality for each body region

* Significant pairwise comparisons for moderate-to-severe lipohypertrophy versus no abnormality

† Significant pairwise comparisons for moderate-to-severe lipoatrophy versus no abnormality Patients who reported central changes (chest, back, waist and belly) were more likely to report moderate-to-severe lipohypertrophy than lipoatrophy. In contrast, patients reporting peripheral changes (face, cheeks, buttocks, arms, and legs) were more likely to report moderate-to-severe lipoatrophy than lipohypertrophy. No significant differences were found among the number of patients reporting moderate-to-severe lipoatrophy (N=23) versus lipohypertrophy (N=21) of the neck Mild abnormalities excluded from figure for simplicity

The highest depression scores were found for patients with moderate-to-severe facial lipoatrophy (15.5 versus 8.8 for patients without facial lipoatrophy or lipohypertrophy, pairwise comparison p=0.01) (note that this instrument distinguishes face and cheeks as 2 regions).

Mean depression scores were higher for patients reporting any lipoatrophy or lipohypertrophy in each body region compared to patients who did not report an abnormality. Differences in depression scores for patients reporting no abnormalities compared with any degree of lipoatrophy or any lipohypertrophy were statistically significant by overall one-way ANOVA for every region except the waist (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In this study of 250 HIV-infected patients attending the clinic for routine visits we found a high prevalence of body morphology abnormalities: 82% of patients had at least some degree of lipoatrophy or lipohypertrophy. Most abnormalities were mild, with 13% of patients reporting moderate-to-severe lipoatrophy or lipohypertrophy. Mean depression scores were significantly higher among patients with lipoatrophy or lipohypertrophy. Moderate-to-severe lipoatrophy was associated with dramatically higher depression scores: over double that of patients reporting no abnormalities in adjusted analyses. The depression instrument has a previously established minimal clinically important different of 4.8 (21). The definition of a minimal clinically important difference varies but is typically the smallest difference in a score considered to be clinically worthwhile or important (4). In adjusted analyses, the increase in depression scores associated with moderate-to-severe lipoatrophy was approximately 2 MCIDs, compared with an increase of just over one MCID for moderate-to-severe lipohypertrophy.

Prior studies have suggested a possible association between lipodystrophy and depression. However, these small studies did not differentiate between lipoatrophy and lipohypertrophy (7, 22, 28). One study found that lipodystrophy was more common among patients taking psychotropic medications such as antidepressants (34). A qualitative study suggested an association between lipodystrophy and depression (28), however only 14 patients were included. To our knowledge, no prior studies have assessed the association between body morphology abnormality severity and depression adjusting for other key factors associated with depression such as sex, age, and current CD4+ cell count.

We adjusted for BMI category in the multivariate analysis because of concerns that lipohypertrophy may in part be measuring obesity. However, findings were not significantly different when BMI category was not included in the analysis.

The highest depression scores were seen among patients reporting facial lipoatrophy which may be due to social stigma and the potential for facial lipoatrophy to identify a person as HIV-infected. Depression is known to have detrimental effects on medication adherence, immune function, disease progression, and survival (6, 9, 16, 24, 27). The association between facial lipoatrophy and depression suggest a simple way for providers to identify patients at increased risk for depression and that treatment of facial lipoatrophy may be an important part of care for HIV-infected patients.

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of our study is the use of the self-report body morphology measure from the Study of Fat Redistribution and Metabolic Change which allows separate examination of lipoatrophy and lipohypertrophy severity and their association with depression. In addition, we examined lipoatrophy and lipohypertrophy in individual body regions. Advantages of self-report over DEXA scans or single-cut CT scans are that patients’ perception of their fat changes may have a larger impact on depression than objective measures. In addition, the association with facial lipoatrophy, a clinically significant finding of this study, can be assessed with self-report. Another strength of this study is use of the Patient Health Questionnaire depression measure which has been extensively studied including its validity, responsiveness, and internal consistency among outpatient, inpatient, clinical trial, and HIV-infected populations (11, 17-21, 23, 29, 30). At 9 items, it is half the length of many other depression measures, has comparable sensitivity and specificity, and encompasses the 9 criteria upon which the diagnosis of DSM-IV (2) depressive disorders are based (18).

A limitation of this observational non-randomized study is that while the cross-sectional design demonstrates a significant association between lipoatrophy, lipohypertrophy, and depression, it does not allow conclusions to be drawn regarding the direction of association. This association may be bi-directional. Patients who are depressed may be more likely to report body morphology abnormalities. More importantly, however, we suspect that lipoatrophy and lipohypertrophy lead to higher depression scores. This hypothesis is supported by a clinical trial of poly-L-lactic acid for facial lipoatrophy which found improvement in depression after lipoatrophy treatment (25). Longitudinal follow-up of patients in the UW HIV cohort will allow us to examine the time course and strengthen conclusions regarding the direction of the association. Our study may be generalizable only to patients with similar characteristics. Further studies are needed to examine the impact of differences in body morphology perception by sex or race.

Conclusions

Lipoatrophy and lipohypertrophy are significantly associated with higher depression scores among HIV-infected patients. Lipoatrophy is associated with more severe depression than lipohypertrophy. Our results suggest that facial lipoatrophy, in particular, has a profound impact on depression severity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The questionnaires for self-report of fat distribution were developed under the auspices of NIH R01 DK 57508. We also wish to thank the patients and providers of the University of Washington Madison HIV clinic. This work was supported by grants from the Mentored Patient-Oriented Research Career Development Award NIAID Grant (AI-60464), and the University of Washington Center for AIDS Research NIAID Grant (AI-27757).

This work was supported by grants from the Mentored Patient-Oriented Research Career Development Award NIAID Grant (AI-60464) and the University of Washington Center for AIDS Research NIAID Grant (AI-27757).

Abbreviations

- cART

combination antiretroviral therapy

- ANOVA

one-way analysis of variance

- UW

University of Washington

- UWHIS

UW HIV Information System

Footnotes

The enclosed article has not been published and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere.

Portions of the data were presented at the 44th Annual Meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, 2006, Toronto, CA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Body Mass Index: How to measure obesity. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: the evidence report.: National Institutes of Health. 1998. pp. 139–140. Appendix 6. NIH Publication #98-4083. [PubMed]

- 2.American Psychiatric Association . Task Force on DSM-IV. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-IV. 4th ed American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. p. xxvii.p. 886. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bacchetti P, Gripshover B, Grunfeld C, et al. Fat distribution in men with HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;40(2):121–31. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000182230.47819.aa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beaton DE, Boers M, Wells GA. Many faces of the minimal clinically important difference (MCID): a literature review and directions for future research. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2002;14(2):109–14. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200203000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bing EG, Burnam MA, Longshore D, et al. Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(8):721–8. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.8.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boarts JM, Sledjeski EM, Bogart LM, Delahanty DL. The differential impact of PTSD and depression on HIV disease markers and adherence to HAART in people living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(3):253–61. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burgoyne R, Collins E, Wagner C, et al. The relationship between lipodystrophy-associated body changes and measures of quality of life and mental health for HIV-positive adults. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(4):981–90. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-2580-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen D, Misra A, Garg A. Clinical review 153: Lipodystrophy in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(11):4845–56. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cook JA, Grey D, Burke J, et al. Depressive symptoms and AIDS-related mortality among a multisite cohort of HIV-positive women. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(7):1133–40. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crane HM, Lober W, Webster E, et al. Routine collection of patient-reported outcomes in an HIV clinic setting: the first 100 patients. Curr HIV Res. 2007;5(1):109–18. doi: 10.2174/157016207779316369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diez-Quevedo C, Rangil T, Sanchez-Planell L, Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. Validation and utility of the patient health questionnaire in diagnosing mental disorders in 1003 general hospital Spanish inpatients. Psychosom Med. 2001;63(4):679–86. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200107000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dukers NH, Stolte IG, Albrecht N, Coutinho RA, de Wit JB. The impact of experiencing lipodystrophy on the sexual behaviour and well-being among HIV-infected homosexual men. AIDS. 2001;15(6):812–3. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200104130-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fat Redistribution and Metabolic Change in HIV Infection (FRAM) Investigators Fat distribution in women with HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;42(5):562–71. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000229996.75116.da. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gripshover B, Tien PC, Saag MS, et al. Lipoatrophy is the dominant feature of the lipodystrophy syndrome in HIV-infected men. 10th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Boston, MA. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hays RD, Cunningham WE, Sherbourne CD, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection in the United States: results from the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study. Am J Med. 2000;108(9):714–22. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00387-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ickovics JR, Hamburger ME, Vlahov D, et al. Mortality, CD4 cell count decline, and depressive symptoms among HIV-seropositive women: longitudinal analysis from the HIV Epidemiology Research Study. JAMA. 2001;285(11):1466–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.11.1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Justice AC, McGinnis KA, Atkinson JH, et al. Psychiatric and neurocognitive disorders among HIV-positive and negative veterans in care: Veterans Aging Cohort Five-Site Study. AIDS. 2004;18(Suppl 1):S49–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lowe B, Kroenke K, Herzog W, Grafe K. Measuring depression outcome with a brief self-report instrument: sensitivity to change of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) J Affect Disord. 2004;81(1):61–6. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(03)00198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lowe B, Schenkel I, Carney-Doebbeling C, Gobel C. Responsiveness of the PHQ-9 to Psychopharmacological Depression Treatment. Psychosomatics. 2006;47(1):62–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.47.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lowe B, Unutzer J, Callahan CM, Perkins AJ, Kroenke K. Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the patient health questionnaire-9. Med Care. 2004;42(12):1194–201. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200412000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marin A, Casado JL, Aranzabal L, et al. Validation of a specific questionnaire on psychological and social repercussions of the lipodystrophy syndrome in HIV-infected patients. Qual Life Res. 2006;15(5):767–75. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-5001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin A, Rief W, Klaiberg A, Braehler E. Validity of the Brief Patient Health Questionnaire Mood Scale (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28(1):71–7. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mayne TJ, Vittinghoff E, Chesney MA, Barrett DC, Coates TJ. Depressive affect and survival among gay and bisexual men infected with HIV. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(19):2233–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moyle GJ, Brown S, Lysakova L, Barton SE. Long-term safety and efficacy of poly-L-lactic acid in the treatment of HIV-related facial lipoatrophy. HIV Med. 2006;7(3):181–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2006.00342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newcombe DA, Humeniuk RE, Ali R. Validation of the World Health Organization Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST): report of results from the Australian site. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2005;24(3):217–26. doi: 10.1080/09595230500170266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(1):21–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-1-200007040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Power R, Tate HL, McGill SM, Taylor C. A qualitative study of the psychosocial implications of lipodystrophy syndrome on HIV positive individuals. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79(2):137–41. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.2.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282(18):1737–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Kroenke K, Hornyak R, McMurray J. Validity and utility of the PRIME-MD patient health questionnaire in assessment of 3000 obstetric-gynecologic patients: the PRIME-MD Patient Health Questionnaire Obstetrics-Gynecology Study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(3):759–69. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.106580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steel JL, Landsittel D, Calhoun B, Wieand S, Kingsley LA. Effects of lipodystrophy on quality of life and depression in HIV-infected men on HAART. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2006;20(8):565–75. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stein MD, Solomon DA, Herman DS, Anderson BJ, Miller I. Depression severity and drug injection HIV risk behaviors. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(9):1659–62. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.9.1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tien PC, Cole SR, Williams CM, et al. Incidence of Lipoatrophy and Lipohypertrophy in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;34(5):461–6. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200312150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsiodras S, Mantzoros C, Hammer S, Samore M. Effects of protease inhibitors on hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, and lipodystrophy: a 5-year cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(13):2050–6. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.13.2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.WHO ASSIST Working Group The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST): development, reliability and feasibility. Addiction. 2002;97(9):1183–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]