Abstract

In this report, we describe the findings of diffusion MR imaging and proton MR spectroscopy in two infants with acute necrotizing encephalopathy in which there was characteristic symmetrical involvement of the thalami. Diffusion MR images of the lesions showed that the observed apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) decrease was more prominent in the first patient, who had more severe brain damage and a poorer clinical outcome, than in the second. Proton MR spectroscopy detected an increase in the glutamate/glutamine complex and mobile lipids in the first case but only a small increase of lactate in the second. Diffusion MR imaging and proton MR spectroscopy may provide useful information not only for diagnosis but also for estimating the severity and clinical outcome of acute necrotizing encephalopathy.

Keywords: Brain, diffusion; Brain, MR; Infants, central nervous system; Magnetic resonance (MR), spectroscopy

Acute necrotizing encephalopathy has recently been reported as a distinct form of acute encephalopathy that affects infants and children, especially in Japan and Taiwan (1-3). It is preceded by fever and symptoms of upper respiratory infection, the prodromal symptoms being ascribed mostly to a variety of viral infections. Neuropathologically, the disease is characterized by symmetric lesions in the thalami, tegmentum of the brain stem, and cerebral or cerebellar white matter, with evidence of breakdown of the blood-brain barrier (1-3). By reflecting this characteristic neuropathology, neuroimaging studies, especially MR imaging, play an important role in the diagnosis of the condition (1-8). In this report, we describe two cases of acute necrotizing encephalopathy, emphasizing the findings of diffusion MR imaging and localized proton MR spectroscopy.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

Two days after the onset of fever, vomiting, and diarrhea, a 10-month-old previously healthy boy was admitted with generalized tonic-clonic seizure. Brain CT, performed elsewhere, revealed the presence of symmetric low-density thalamic lesions. On admission, he was drowsy and showed decerebrate rigidity, without focal neurologic signs.

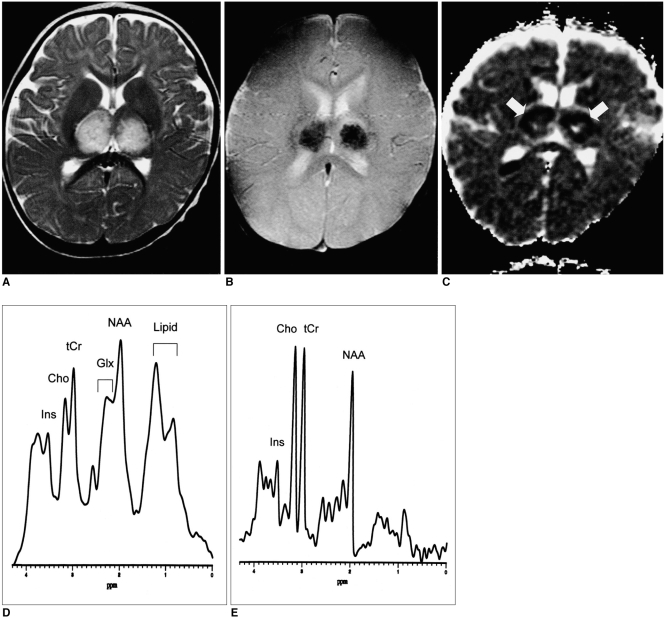

Conventional brain MR images obtained using a 1.5-T system on the second day of hospitalization depicted symmetric distribution of T1- and T2-prolonged areas in the thalami (Fig. 1A), tegmentum of the pons, and periventricular white matter. T2*-weighted gradient-echo images (TR/TE = 800/30, flip angle = 20°) demonstrated low signal intensities within the thalamic lesions, suggesting acute hemorrhage (Fig. 1B). After the intravenous administration of gadolinium-diethylene triamine penta-acetic acid, the lesions showed no abnormal enhancement. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging (b value=1000 sec/mm2) demonstrated high signal intensity in all the lesions, though this was absent in the central portion of thalamic lesions, and other than in this same area, apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) mapping revealed low signal intensity (Fig. 1C). Localized proton MR spectroscopy of the thalami using a stimulated echo-acquisition mode sequence (TR/TE=3000/30, 96 acquisitions, volume of interest=7 mL) showed that compared with an age-matched control subject, peak intensities were higher, occurring at 2.0-2.5 and 0.8-1.5 ppm (Figs. 1D, E).

Fig. 1.

A 10-month-old boy with sequelae of severe motor deficit.

A. Axial fast spin-echo T2-weighted MR image (TR/TE=3500/120) shows symmetric high signal intensity in the bilateral thalami.

B. Axial T2*-weighted gradient-echo MR image (TR/TE=800/30, flip angle = 20°) at the same level as A shows conspicuous low signal intensity within the thalamic lesions, possibly due to the presence there of acute petechial hemorrhage.

C. Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) map of diffusion imaging reveals low ADC in the thalamic lesions (arrows), which may represent the presence of cytotoxic edema. In the central portion of the lesions, however, ADC is high, suggesting tissue necrosis.

D. Short echo-time proton MR spectrogram (STEAM 3000/30) of a thalamic lesion shows increased glutamate/glutamine complex peak intensities at 2.0-2.5 ppm and lipid/lactate complex peak intensities at 0.8-1.5 ppm, as compared with an age-matched control subject (E). Broadening of the line-width may be caused by the occurrence of petechial hemorrhage within the lesion.

E. Short echo-time proton MR spectrogram (STEAM 3000/30) of normal thalamus in a 9-month-old age-matched control subject.

Note.-Ins=myoinositol, Cho=choline compound, tCr=creatine complex, Glx=glutamate/glutamine complex, NAA=N-acetyl aspartate

Laboratory findings on admission showed increased serum aspartate and alanine aminotransferase levels, though those of blood ammonium and lactate were normal. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis showed slightly increased protein content, without pleocytosis. Polymerase chain reaction analysis of the CSF was negative for deoxynucleic acid (DNA) of herpes simplex virus and enterovirus, and similar analysis of peripheral blood was negative for major mutations in mitochondrial DNA, which would indicate mitochondrial encephalopathy with lactic acidosis and stroke-like episode (MELAS) syndrome.

The patient was treated with acyclovir, an antiviral agent, and steroid. His mental state improved, and on the fourth day of hospitalization he was almost alert. Cognitive functions gradually improved, though severe motor deficits remained. Follow-up brain MR imaging performed three months later revealed residual atrophic change in the previously observed lesions; both T1- and T2-weighted images depicted small areas of high signal intensity at the center of the thalami, indicating residual subacute hemorrhage.

Case 2

Four days after the development of fever, cough, and rhinorrhea, a 6-month-old, previously healthy girl was admitted with generalized tonic-clonic seizure and mental change, as well as increased rigidity of the extremities. CT images of the brain, obtained at another hospital, depicted symmetric low-density lesions in the thalami and external capsules. Two months earlier, the patient's elder sister had died of acute encephalopathy.

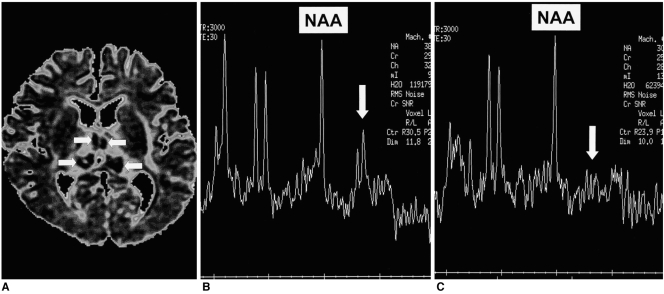

Conventional brain MR imaging performed on the second day of hospitalization indicated that symmetric T1- and T2-prolonged areas were present in the thalami and external capsules. T2*-weighted gradient-echo images clearly showed that within the thalamic lesions, acute hemorrhage had occurred. After the intravenous administration of gadolinium-diethylene triamine penta-acetic acid, the lesions showed no abnormal enhancement and ADC mapping revealed areas of low signal intensity within them (Fig. 2A). Localized proton MR spectroscopy using a stimulated echo-acquisition mode sequence (TR/TE=3000/30, 96 acquisitions, volume of interest=7 mL) showed a small doublet at 1.33 ppm (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

A 6-month-old girl without significant neurologic sequelae.

A. ADC map of diffusion imaging shows that the thalamic lesions have a concentric appearance. They have high-signal centers with low-signal rims (arrows), and the ADC values of their remaining portion are high.

B. Initial proton MR spectrogram (STEAM 3000/30) of a lesion shows a small lactate peak (arrow). The N-acetyl aspartate peak is within the normal range.

C. Follow-up proton MR spectrogram (STEAM 3000/30) obtained one week later shows no lactate peak (arrow). The N-acetyl aspartate peak shows no interval change and is still within the normal range.

Note.-NAA=N-acetyl aspartate

Laboratory findings indicated slightly increased levels of serum aspartate aminotransferase, lactate, and ammonia, though the lactate level rapidly returned to normal. CSF analysis revealed increased protein content without pleocytosis. Polymerase chain reaction analysis of the CSF was negative for DNA of herpes simplex virus and enterovirus, and similar analysis of peripheral blood was negative for major mutations in mitochondrial DNA.

The patient was thought to be suffering from acute necrotizing encephalopathy, and was treated with mannitol, acyclovir, and steroid. Her mental state improved and on the second day of hospitalization her level of alertness was almost normal. The extremities gradually became less rigid, and follow-up brain MR imaging and MR spectroscopy performed one week later revealed marked improvement of the initial lesions and disappearance of the doublet at 1.33 ppm (Fig. 2C).

DISCUSSION

Acute necrotizing encephalopathy of childhood is a distinct form of acute encephalopathy recently reported from Japan (2-4). Since then, similar cases in other countries have been described (5-7). The clinico-radiological features of our cases closely correspond to the diagnostic criteria suggested by Mizuguchi (1), namely clinical findings of acute encephalopathy following febrile prodromata, rapid deterioration in the level of consciousness, and convulsions; laboratory findings which indicate an absence of CSF pleocytosis, together with frequently increased CSF protein and serum aminotransferase levels but no increase in blood ammonia; characteristic neuroimaging findings; and the exclusion of similar disease. Among the characteristic neuroimaging findings, symmetric lesions in the thalami were most constant, being observed in all reported cases (1-8). Bilateral tegmental involvement of the brain stem was the second most common finding, present in about 60% of cases.

Neuropathologically, the lesions occurring in acute necrotizing encephalopathy have been described as having a concentric or laminar structure (9). Perivascular petechial hemorrhage and necrosis of neurons and glial cells occurred in the center of lesions, and in the outer portion, all vessels were congested and acutely swollen oligodendrocytes were observed. Along the edge of lesions, the pathologic findings were extravasation mainly around the arteries and myelin pallor.

The diffusion MR imaging findings of acute necrotizing encephalopathy have previously been reported (8). The ADC value was found to be initially lower than normal, indicating decreased water diffusibility, a very useful finding in differentiating acute necrotizing encephalopathy from acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis; this low ADC value seen during the acute phase slowly increased during follow-up studies. In our cases, a low ADC was observed, except in the central portion of thalamic lesions, where ADC was high. The causes of ADC decrease during the acute phase of acute necrotizing encephalopathy are not clear, though it is most likely due to swollen neuroglial cells within the lesions, as in acute ischemic infarctions, or to the swelling of myelin. Supportive evidence for this is the presence of swollen oligodendrocytes or myelin pallor, revealed by pathologic examination. Another possible cause is the presence of acute petechial hemorrhage within a lesion, particularly a thalamic lesion. It is well known that diffusion MR imaging reveals the lower than normal ADC caused by acute hemorrhage (10), but the ADC decrease seen in non-hemorrhagic lesions is difficult to explain. We believe, therefore, that the cytotoxic edema occurring in neuroglial cells and possible swelling of myelin is the dominant cause of ADC decrease in acute necrotizing encephalopathy.

In the brain, decreased ADC is observed most frequently in cases involving hyperacute infarction, but rarely in status epilepticus, hemiplegic migraine or venous infarction. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy is a further example of a brain disorder in which a lower ADC is found in the involved areas, and in most clinical situations this decrease involves significant neuroglial damage. We speculate that the degree and extent of ADC decrease can be used to predict brain damage or the clinical outcome in patients with acute necrotizing encephalopathy, and our experience, though limited to only two cases, supports this possibility. In the first patient, in whom the ADC of thalamic lesions showed a greater decrease, there was more significant morphologic damage and a poorer clinical outcome, as shown at follow-up, than in the second, whose ADC of thalamic lesions was only slightly decreased. In both our cases, the central high ADC area surrounded by a thick, rim-like area of low ADC in the thalami correlated closely with the pathologic findings of lesions with a concentric or laminar structure, as mentioned above. In severe cases of acute necrotizing encephalopathy, rapid neuroglial cell death or necrosis may occur in the central portion of a lesion, surrounded by a less severely damaged zone, pathological change which can be clearly demonstrated by diffusion MR imaging. In milder cases, as in our second patient, brain damage may be less severe and the pathological change occurring may be seen at diffusion MR imaging as a slight decrease in ADC.

The proton MR spectroscopic findings of acute necrotizing encephalopathy have previously been reported (5, 8). Follow-up studies showed that a small lactate peak seen at initial MR spectroscopy had rapidly returned to within the normal range (8), and we also observed this change in our second patient. In our first case, we noted that peak intensities were higher at 2.0-2.5 ppm, a finding not reported in previous proton MR spectroscopic studies of this disease. The peak is usually caused by the glutamate/glutamine complex within the brain, and it is well known that cerebral glutamine is increased in the presence of hyperammonemia (11). Because of the absence of hyperammonemia in our first case, it is less likely that the peak was due to increased cerebral glutamine, and we speculate that it may, instead, have been due mainly to increased cerebral glutamate. Glutamate is a well-known excitatory neurotransmitter but can cause excitotoxic neuronal damage if excessive amounts are released into the synaptic cleft. It is, therefore, tempting to explain the neuronal damage occurring in acute necrotizing encephalopathy in terms of glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity. An increase in glutamate was not, however, observed in our second case or in those previously reported, suggesting that it may be transient or depend on the severity of the disease. In our first case, another interesting MR spectroscopic finding was the broad peak occurring at 0.8-1.5 ppm. As the increased peak intensities were broad rather than a narrow doublet at 1.33 ppm, we believe that most are due to mobile lipids, the increase of which may result from cell membrane damage or disintegration; pathological evidence which supports this hypothesis is the neuroglial cell necrosis occurring at the center of the lesions. This was not, however, observed in the second case, in which diffusion MRI demonstrated a slightly decreased ADC and the clinical outcome was good. We consider that the combined increase in the glutamate/glutamine complex and mobile lipids is a spectroscopic sign suggesting significant neuroglial damage in the investigated regions.

At follow-up T1-weighted imaging, subacute perivascular petechial hemorrhage has been detected (1-3, 6, 7), and in our cases, T2*-weighted gradient-echo imaging detected acute petechial hemorrhage in the center of the thalamic lesions; T2-weighted images obtained during the acute phase showed homogeneous high signal intensity and the presence of hemorrhage was not detected. Small petechial hemorrhage may, however, be obscured within the lesions on T2-weighted images, and T2*-weighted gradient-echo imaging may help characterize the lesions by identifying central hemorrhage during the acute phase.

In acute necrotizing encephalopathy, the infectious organisms identified are almost always viruses, and so an antiviral agent such as acyclovir is used for treatment. Another widely used agent is steroid, which has an anticytokine effect, and since the effect of hypothermia is similar, it too has recently been used in the treatment of patients with acute necrotizing encephalopathy (12). Such anticytokine therapies are based on the observation that in the CSF and serum of patients with this disease, proinflammatory cytokine levels, including those of interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α, increase.

In this report, we have described two cases of acute necrotizing encephalopathy examined by diffusion MR imaging and proton MR spectroscopy, as well as routine brain MR imaging. Diffusion MR imaging revealed a more prominent decrease of ADC in the first patient, who had more severe brain damage and a poorer clinical outcome than the second. Proton MR spectroscopy demonstrated increased glutamate/glutamine complex and mobile lipids in the first case and only a small increase of lactate in the second, less severe, case. We conclude that diffusion MR imaging and proton MR spectroscopy may provide useful information not only for diagnosis, but also for estimating the severity and clinical outcome of acute necrotizing encephalopathy.

References

- 1.Mizuguchi M. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy of childhood: a novel form of acute encephalopathy prevalent in Japan and Taiwan. Brain Dev. 1997;19:81–92. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(96)00063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mizuguchi M, Abe J, Mikkaichi K, et al. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy of childhood: a new syndrome presenting with multifocal, symmetric brain lesions. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1995;58:555–561. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.58.5.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yagishita A, Nakano I, Ushioda T, Otsuki N, Hasegawa A. Acute encephalopathy with bilateral thalamotegmental involvement in infants and children: imaging and pathology findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1995;16:439–447. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fujimoto Y, Shibata M, Tsuyuki M, Okada M, Tsuzuki K. Influenza A virus encephalopathy with symmetrical thalamic lesions. Eur J Pediatr. 2000;159:319–321. doi: 10.1007/s004310051280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Porto L, Lanferman H, Moller-Hartmann W, Jacobi G, Zanella F. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy of childhood after exanthema subitum outside Japan or Taiwan. Neuroradiology. 1999;41:732–734. doi: 10.1007/s002340050833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campistol J, Gassio R, Pineda M, Fernandez-Alvarez E. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy of childhood (infantile bilateral thalamic necrosis): two non-Japanese cases. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1998;40:771–774. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1998.tb12346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim YJ, Chun KA, Kim KT, Choi KH, Kim YH. MR imaging of acute necrotizing encephalopathy: a report of two cases. J Korean Radiol Soc. 2001;44:633–636. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harada M, Hisaoka S, Mori K, Yoneda K, Noda SN, Nishitani H. Differences in water diffusion and lactate production in two different types of postinfectious encephalopathy. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2000;11:559–563. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2586(200005)11:5<559::aid-jmri12>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mizuguchi M, Hayashi M, Nakano I, et al. Concentric structure of thalamic lesions in acute necrotizing encephalopathy. Neuroradiology. 2002;44:489–493. doi: 10.1007/s00234-002-0773-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang BK, Na DG, Ryoo JW, Byun HS, Roh HG, Pyeun YS. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging of intracerebral hemorrhage. Korean J Radiol. 2001;2:183–191. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2001.2.4.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Graaf AA, Deutz NE, Bosman DK, Chamuleau RA, de Haan JG, Bovee WM. The use of in-vivo proton NMR to study the effects of hyperammonemia in the rat cerebral cortex. NMR Biomed. 1991;4:31–37. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1940040106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munakata M, Kato R, Yokoyama H, et al. Combined therapy with hypothermia and anticytokine agents in influenza A encephalopathy. Brain Dev. 2000;22:373–377. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(00)00169-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]