Abstract

The incidence of suicide in Japan has increased markedly in recent years, making suicide a major social problem. Between 1997 and 2006, the annual number of suicides increased from 24,000 to 32,000; the most dramatic increase occurred in middle-aged men, the group showing the greatest increase in depression. Recent studies have shown that prevention campaigns are effective in reducing the total number of suicides in various areas of Japan, such as Akita Prefecture. Such interventions have been targeted at relatively urban populations, and national data from public health and clinical studies are still needed. The Japanese government has established the goal of reducing the annual number of suicides to 22,000 by 2010; toward this end, several programs have been proposed, including the Mental Barrier-Free Declaration, and the Guidelines for the Management of Depression by Health Care Professionals and Public Servants. However, the number of suicides has not declined over the past 10 years. Achieving the national goal during the remaining years will require extensive and consistent campaigns dealing with the issues and problems underlying suicide, as well as simple screening methods for detecting depression. These campaigns must reach those individuals whose high-risk status goes unrecognized. In this review paper, we propose a strategy for the early detection of suicide risk by screening for depression according to self-perceived symptoms. This approach was based on the symposium Approach to the Prevention of Suicide in Clinical and Occupational Medicine held at the 78th Conference of the Japanese Society of Hygiene, 2008.

Keywords: Depressive disorders, Japan, Prevention and control, Suicide

Introduction

The population of Japan is characterized by the greatest longevity in the world; according to the World Health Report 2003 [1], life expectancy was the highest in Japan (75.0 years), followed San Marino (73.4 years), Sweden (73.3 years), Monaco (72.9 years), and Iceland (72.8 years). However, the suicide rate in Japan also ranked high (24.2 per 100,000), placing it ninth in the world [2, 3]. Within the total Japanese population, malignant neoplasms (258.3 per 100,000 in 2005), heart diseases (138.0), and cerebrovascular diseases (107.1) represent the major causes of death [4]. However, suicide has emerged as the leading cause of death among men aged 20–44 years and women aged 15–34 years in Japan [4, 5].

In Japan, the incidence of suicide rose dramatically, from 20,100 (17.2 per 100,000) to 30,600 (24.2 per 100,000) between 1995 and 2005 [3]. The number of suicides per year has increased in all age categories over the last 10 years, and the increase was particularly remarkable among those in their 40s to 60s. The most frequently used methods of suicide were suffocation/hanging (60.9% for men and 53.8% for women), followed by poisoning (9.3% for men and 10.1% for women), gas inhalation (9.6% for men and 6.9% for women), and jumping (7.6% for men and 9.3% for women) [6]. The primary problems precipitating suicide were, in order, health-related, financial, and family-related issues [6].

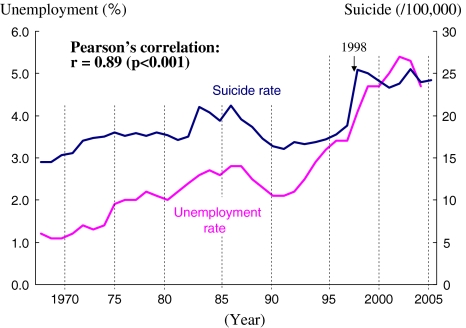

Some studies have indicated that the dramatic increase in suicide is closely related to the Japanese economic depression that occurred during the same decade [7]. Many employees were forced to work harder due to continuing business restructuring; numerous cases of suicide have been officially acknowledged as related to depression deriving from overwork over the past 10 years. The annual number of suicides has been reported to be closely correlated with the unemployment rate in Japan [4] (Fig. 1). Regionally, the average suicide rates (per 100,000) range from 15.7 (in Kanagawa Prefecture) to 29.4 (in Akita Prefecture) among the 47 prefectures in Japan. The suicide rate seems to be greatly influenced not only by socioeconomic factors but also by meteorological factors (e.g., cold weather, insufficient sunshine, and snowfall) [8] (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Relationship between suicide rate and unemployment rate in Japan

Table 1.

Major risk factors associated with suicide

| Clinical factors |

| Psychiatric disorders (e.g., depression, schizophrenia, alcohol dependency, substance abuse) |

| Physical disorders (e.g., cancer, HIV infection) |

| History of suicidal attempt |

| Sociodemographic factors |

| Gender (men) |

| Age (elderly) |

| Unmarried (single, separated, divorced, widowed) |

| Component of family members (living board) |

| Occupation (including unemployment) |

| Socioeconomic status (including low income) |

| Social life factors |

| Poor social welfare in community (e.g., insufficient livelihood protection) |

| Meteorological condition (e.g., cold weather, insufficient sunshine, and snowfall) |

The recent issues surrounding suicide in Japan underpinned the symposium Approach to the Prevention of Suicide in Clinical and Occupational Medicine at the 78th Conference of the Japanese Society of Hygiene on 30 March 2008. Several important findings and proposals were presented at this symposium [9], including using the Employee Assistance Program to prevent suicide in the workplace (Nakao), screening for depression in the workplace using self-perceived symptoms (Takeuchi), analyzing gender differences in self-perceived symptoms relating to suicidal ideation in outpatients visiting a psychosomatic medicine clinic (Yoshimasu), and assessing suicide awareness and prevention education among adolescents (Nakano). The panel discussion at the symposium produced a consensus of opinions regarding the primary importance of health care professionals routinely assessing suicidal ideation using simple and standardized methods. Data indicating that a significant proportion of those who commit suicide make contact with health service providers with regard to mind/body complaints during the period shortly preceding death [10] underscores the importance of this approach. Therefore, in this review, we focused on self-reports of symptoms as possibly crucial in the identification of individuals at high risk for suicide, and we propose a suicide prevention strategy for application in the daily practices of clinical and occupational medicine.

Depression in Japan

Depression clearly plays an important role in the epidemiology of suicide, and more than 60% of individuals who committed suicide were identified as being depressed [11]. Identification of individuals at high risk for depression should contribute to a reduction in the number of suicide attempts. Although the incidence of depression has been increasing rapidly in Western countries, the number of people diagnosed with depression in Japan increased from 100,000 (83.1 per 100,000) to 430,000 (340.0 per 100,000) between 1984 and 1998 [11]. These data on suicide in Japan may be related to the increased tendency of physicians to diagnose depression using a standard method, such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) [12], or to the decreased resistance of those suffering from mind/body distress to visiting psychiatrists. Although depression is generally more common in women than in men [13], the most dramatic increase in rates of depression occurred among middle-aged males (40–60 years old), and a similar trend was observed in Japan among those who committed suicide [7]. Analysis of the relationship between six categories of occupational status and suicide revealed that suicide rates were highest among the unemployed and employee groups [6]. Therefore, strategies designed to identify potentially depressed individuals, in the service of suicide prevention in Japan, may target employees or the unemployed who are also middle-aged [14].

Suicide in the workplace

The US National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) [15] used data derived from epidemiological studies to identify the following occupational roles as being associated with the greatest risk of suicide: actors, automobile mechanics, chemical workers, chemists, dentists, electric utility workers, farmers, forestry workers, highway maintenance workers, military personnel, nurses, pharmaceutical industry workers, physicians, police officers, social workers, tobacco industry workers, and veterinarians. Within these occupations, the high suicide risk remains for health care workers (odds ratios: 5.43 for dentists, 2.31 for doctors, 1.58 for nurses, and 1.52 for social workers), even after controlling for the effects of age, gender, marital status, and race [16]. According to the recent occupational data in Japan [6], the suicide rate in a group of doctors (32.3 per 100,000) was certainly higher than the rates of other independent workers, such as farmers, forestry workers, fishermen (25.7 per 100,000), and workers in bars and restaurants (10.3 per 100,000), but it was not so outstanding when compared with a Japanese general population. It has been suggested that health care workers can use their knowledge of anatomy and toxicology as well as their access to drugs in suicide attempts, thus resulting in an increased likelihood that impulsive attempts will be lethal in Western countries [17]; however, this finding has not been confirmed in Japan.

Instead, elevated rates of suicide within particular occupational groups may result from complex interactions among work-related (e.g., work stress and access to potentially lethal materials) and other risk factors (e.g., socioeconomic status and psychiatric morbidity) [15–17]. According to the 2004 Japanese national survey of health [4], 49% of individuals aged 12 years or older reported experiencing stress in their daily lives. In this survey, the subjects answered yes if they perceived stress in any of 28 domains, including relationships with coworkers, family members, or neighbors, as well as in regard to living, social, financial, and health conditions. A higher percentage of women (53%) than men (45%) reported stress. Indeed, more recent data show that the percentages of both men and women reporting stress have increased in Japan [4]. Work-related problems were identified as the most frequent stressors, followed by health-related issues and then financial problems [4]. Long working hours, fears of job loss, and pressures to compete and succeed can carry serious consequences for the psychological health of workers. A survey performed in 2004 [4] indicated that 47% of Japanese workers showed some abnormalities on regular medical examinations; moreover, the number of workers complaining of mental rather than physical fatigue has been increasing. Perceived work stress is influenced by the match between the abilities of a worker and the environment in which they are employed, including job demands, individual control of job-related factors, and social support from colleagues and supervisors (i.e., the demand–control model) [18]. The working environment is also influenced by the degree to which a gap exists between the goals and aspirations held by workers and the rewards available in the work environment (i.e., the effort–reward model) [19]. According to a British longitudinal study among civil servants [20], psychological morbidity was predicted by high job demands, low decision authority, poor social support at work, and effort–reward imbalance. In general, stressful work environments can present risk factors for mental health disorders and suicidal behavior.

Suicide rates among the unemployed in various populations are not consistently associated with socioeconomic status [15]. This finding is derived in part from the difficulty of establishing social class distinctions among those who are unemployed, as complete data for income, occupation, and education are often unavailable. However, recent studies have suggested an inverse relationship between suicide rate and socioeconomic status [15]. The expected increase in suicide rate as a function of increasing age is particularly pronounced among workers in occupations with low socioeconomic status [21]. These findings are consistent with most studies in which an inverse correlation between socioeconomic status and suicide rates has emerged.

Current status of the literature

A MEDLINE search was performed to locate relevant studies of suicide in Japan published between 1966 and March 2008. Two medical subject headings (MeSH) were used: suicide and Japan. The headings were combined using the Boolean operator AND. The search identified a total of 352 articles; 285 of these were written in English, including 26 letters, eight reviews, six clinical trials, three editorials, and one meta-analysis. In a community survey [22], 12% of elderly people were reported to have experienced thoughts of death or suicide, and 3% had experienced such thoughts persistently for more than 2 weeks. Among elderly people with such thoughts, 23% had consulted physicians and 20% had asked family members for help [22]. The relative risk for suicide associated with depression was 9.95 according to a 6-year cohort study among 5,352 Japanese male workers aged 40–54 years [23]. Several studies [24, 25] indicated that socioeconomic factors affect the suicide mortality rate in Japan; low income and conditions created by economic depression emerged as major factors. Recent studies have shown that a suicide prevention campaign has been effective in reducing the number of suicides in various areas in Japan, including Akita Prefecture in the Tohoku region [26, 27].

Community-based intervention for suicide prevention

Akita Prefecture has had the highest suicide rate among the 47 prefectures in Japan since 1997. To tackle this problem, systematic intervention for suicide prevention has been conducted with a clear focus on community-based health promotion in this and other prefectures in the Tohoku region. For example, a community-based intervention was conducted in Akita Prefecture between 2001 and 2004 [27]. This was a nonrandomized control trial based on a quasi-experimental design, consisting of 43,963 residents in six towns as the intervention group and 297,071 residents in the other towns located in Akita Prefecture as the control group [27]. The intervention program was as follows: (1) implementation of a resident-based survey on mental health, (2) specialist training on suicide prevention for public health and welfare staff, (3) residents’ cooperation in performing basic resident surveys, planning independent meetings for mental health lectures, and raising awareness of theatrical performances, (4) distribution of list of counseling centers for residents with worries or concerns, and (5) establishment of a community network among senior citizens to eliminate the sense of psychological isolation by elderly people. As a result, the suicide rate in the intervention towns decreased from 70.8 per 100,000 before intervention (in 1999) to 34.1 per 100,000 after intervention (in 2004), although the figures in the control group were 47.8 before intervention and 49.1 after intervention. The importance of community-based intervention for suicide prevention has become recognized in Japan, and now many prefectures have planned their own public health approach for suicide prevention [28].

Symptoms related to suicidal ideation

In a clinical study by Nakao et al. [29], 863 outpatients (306 men, 557 women, mean age 34 years) attending a psychosomatic clinic were studied to examine associations among suicidal ideation, somatic symptoms, and mood states. All patients were diagnosed using the multiaxial assessment model of the DSM, Third Edition, Revised (DSM-III-R), and the Fourth Edition (DSM-IV). Subjects completed the Cornell Medical Index Questionnaire to assess suicidal ideation and somatic symptoms. Mood states were rated using the Profile of Mood States (POMS). In this population, 266 patients (31%) reported suicidal ideation. As reported in the DSM-III-R and DSM-IV, those with personality disorders, higher psychosocial stress, and lower psychosocial functioning tended toward suicidal ideation (P < 0.01). Multiple regression analysis demonstrated that the total number of somatic symptoms and the POMS depression scale predicted suicidal ideation (P < 0.05). It was concluded that evaluations of somatic symptoms and depressed mood states are important in assessing suicidal ideation within a Japanese clinical population suffering from mind/body distress.

The close relationship between suicidal ideation and psychosocial factors was confirmed in a clinical study conducted by Yoshimasu et al. in a population consisting of 199 new outpatients (66 men and 133 women) diagnosed with major depression [30]. Suicidal ideation and psychiatric symptoms were assessed with psychological tests using questionnaire formats. In univariate analysis, several psychosocial factors (self-reproach, derealization, depressive moods, depersonalization, and anxiety) were significantly associated with suicidal ideation among both men and women. However, multivariate analysis using the stepwise method of multiple logistic regression analysis identified gender differences (Table 2). Low social/family support and depersonalization were significantly associated with suicidal ideation in men, whereas derealization, depressive mood, and anxiety state were significantly associated with suicidal ideation in women.

Table 2.

Psychological symptoms relating to suicidal ideation in outpatients with major depression: results of multiple logistic regression analysis, stepwise method

| Age adjusted odds ratio and its 95% confidence intervals | |

|---|---|

| Men (n = 66) | Women (n = 133) |

| Derealization (2.9, 0.9–9.9) | Derealization (3.2, 1.4–7.4) |

| Low social/family support (10.7, 1.5–77.4) | Depressive mood (4.9, 1.8–13.1) |

| Depersonalization (4.2, 1.2–15.3) | State anxiety (4.2, 1.2–14.4) |

This table was constructed by reanalyzing data from a previous study by Yoshimasu et al. [30]

The existence of gender differences in regard to the psychological factors related to suicidal ideation in depressed Japanese patients represents an important finding. In general, women are more likely to report suicidal ideation than men [30, 31], but the inverse findings have also been reported with regard to gender differences in completed suicide vs. suicidal ideation [32, 33]. Women reporting suicidal ideation may be more likely to be identified and treated at earlier stages of suicidal behavior compared with men. It is also possible that men may be more reluctant than women to acknowledge feelings, including those involved in suicidal ideation, and that women may be more likely to visit or be referred to psychological specialists [34]. In a study by Nakao et al. [34], psychological distress among female outpatients attending a US psychosomatic medicine clinic deviated less from female population norms than male patients deviated from male population norms, as assessed by the symptom checklist 90R [35]. Future research should focus on the gender differences in suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and deaths by suicide in clinical as well as general populations.

Self-reported symptoms related to depression

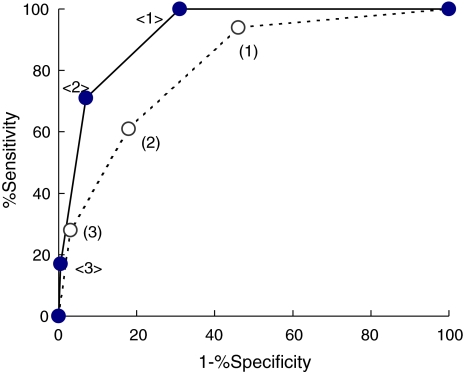

Evaluations of depression should include assessment of self-reported symptoms. A recent study by Takeuchi et al. [36] indicated that including one or two questions related to depression in annual medical checkups can represent an effective method for identifying major depression in Japanese workers. Items used for screening purposes would not focus on psychological discomfort alone; rather, inquiries into common somatic symptoms can also be useful. In a study by Nakao et al. [37], 1,443 Japanese employees (991 men and 452 women, mean age 34 years) were interviewed at annual health checkups, and 42 (2.9%) were diagnosed with major depression according to DSM-IV criteria. Congruent with previous studies [38, 39], and with Western studies among primary care patients [40, 41], the following 12 common major somatic symptoms were assessed: fatigue, headache, insomnia, back pain, abdominal pain, joint or limb pain, dizziness, chest pain, constipation, palpitation, nausea, and shortness of breath. Respondents were considered positive for somatic symptoms when these symptoms occurred at least once per week. In a previous study [37], 665 men reporting none of these somatic symptoms were also free from major depression (Table 3). Among the 237 women without somatic symptoms, only one was diagnosed with major depression. The prevalence of major depression was positively associated (P < 0.001) with the total number of somatic symptoms in both genders; the areas under the receiver-operator characteristic (ROC) curves were 0.92 in men and 0.81 in women (Fig. 2), indicating the sensitivity and specificity of the total number of somatic symptoms with respect to identifying major depression. Five percent of the total sample reported experienced suicidal ideation, but none of these subjects reported somatic symptoms. Although this study used a cross-cultural design, a cohort study conducted at 2 years [42] and at 20 years [43] indicated that somatic symptoms can significantly predict future depression.

Table 3.

The number of somatic symptoms and major depression in Japanese workers

| The number of somatic symptoms | The number of workers with somatic symptoms (n) | The number of workers with major depression (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 1.443) | ||

| 0 | 902 | 1 (0.1) |

| 1 | 371 | 13 (3.5) |

| 2 or 3 | 143 | 19 (13.3) |

| ≥4 | 27 | 9 (33.3)* |

| Men (n = 991) | ||

| 0 | 665 | 0 (0) |

| 1 | 244 | 7 (2.9) |

| 2 or 3 | 73 | 13 (17.8) |

| ≥4 | 9 | 4 (44.4)* |

| Women (n = 452) | ||

| 0 | 237 | 1 (0.4) |

| 1 | 127 | 6 (4.7) |

| 2 or 3 | 70 | 6 (8.6) |

| ≥4 | 18 | 5 (27.8)* |

This table was constructed by reanalyzing data from a previous study conducted by Nakao et al. [37]

* P < 0.001 in four groups (chi-square test)

Fig. 2.

Receiver-operator characteristic (ROC) curves of the total number of somatic symptoms for screening major depression in Japanese workers. Closed and open circles indicate the sensitivity and specificity in men (n = 991) and women (n = 452), respectively. <1>(1) Cutoff point of the total number of somatic symptoms as ≥1 (positive) or 0 (negative). <2> (2) Cutoff point of the total number of somatic symptoms as ≥2 (positive) or ≤1 (negative). <3> (3) Cutoff point of the total number of somatic symptoms as ≥4 (positive) or ≤3 (negative). This figure was completed by reanalyzing data from a previous study conducted by Nakao et al. [37]

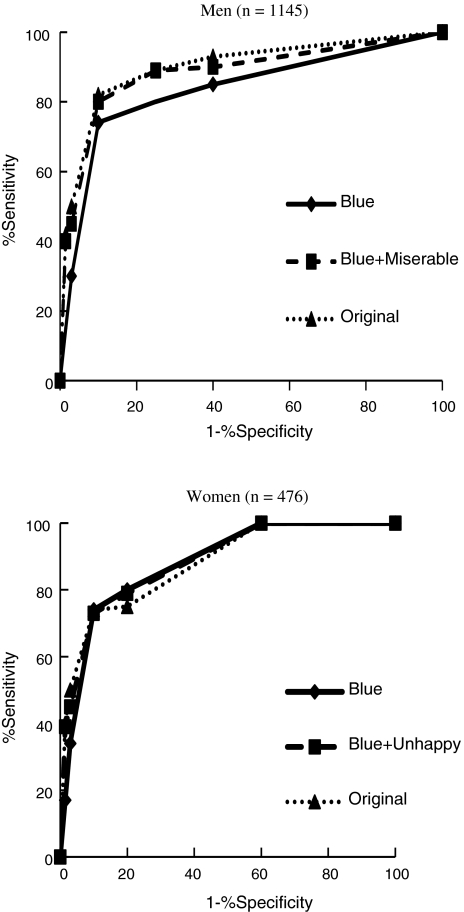

Our use of self-reported data was supported by several previous studies [44–46]. The diagnosis of depression remains a difficult task, even for psychiatrists and psychological specialists, due to the complexity of the issues involved and the time required for the interview. Although reliable questionnaires [e.g., POMS, the Self-rating Depression Scale (SDS), and Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (CES-D)], have been developed for use in clinical screening (Table 4), these are burdensome due to the sheer number of questions they contain. Researchers in the USA have reported that two items (“depressed mood” and “anhedonia”) in the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders Questionnaire (PRIME-MD) showed 96% sensitivity and 57% specificity for detecting major depression [44]. European researchers reported that two items (“not cheerful” and “not active”) in the World Health Organization (WHO)-5 Wellbeing Index were sufficient for screening for depression [45]. Thus, we suggest using one or two items addressing self-perceived symptoms as a screening tool for depression during medical checkups among both men and women (Fig. 3).

Table 4.

Major questionnaires used frequently to assess depression

| Questionnaire | Item | Period of assessment | Score range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beck Depression Index (BDI) | 7,13, or 21 | Today | 0–63 |

| Center for Epidemiologic Study Depression Scale (CES-D) | 10 or 20 | Past 1 week | 0–63 |

| Depression Scale (DEPS) | 10 | Last month | 0–30 |

| Duke Anxiety and Depression Scale (DADS) | 7 | Past 1 week | 0–100 |

| Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) | 15 or 30 | Past 1 week | 0–30 |

| Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL) | 13 or 25 | Past 1 week | 25–100 |

| Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (PRIME-MD) | 2 | Past 1 month | 0–2 |

| PRIME-MD Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) | 9 | Past 2 weeks | 0–9 |

| Profile of Mood State (POMS) | 15 for depression | Past 1 week | 0–60 |

| Symptom Driven Diagnostic System–Primary Care (SDDS-PC) | 5 | Past 1 month | 0–5 |

| Zung Self-assessment Depression Scale (SDS) | 20 | Recently | 20–80 |

| Single Question (SQ) | 1 | Past 1 year | 0–1 |

| WHO-5 Wellbeing Index | 5 | Past 2 weeks | 0–25 |

Fig. 3.

Receiver-operator characteristic (ROC) curves for the best-selected models of one-item, two-item, and original 15-item versions of the Profile of Mood States (POMS) depression scale in Japanese workers. The figure indicates ROC curves for the best-selected models of one-item (blue), two-item (blue and miserable or blue and unhappy), and original 15-item versions of the POMS depression scale for men and for women. This figure was constructed by reanalyzing data from a previous study conducted by Takeuchi et al. [36]

Suicide prevention strategy in Japan

In 2000, the Japanese government declared its intention to reduce the annual number of suicides to 22,000 by 2010 [47]; in 2002, the national committee reported on possible strategies to prevent suicide [11], emphasizing the importance of preintervention (assessment of factors affecting suicide), intervention (identification of persons at high risk in order to prevent suicide), and postintervention (social support for bereaved families and friends). On the basis of these ideas [11], two manuals for the management of depression were published for health care professionals [48] and public servants [49]. These manuals contained a screening test for depression and recommended that this test be administered at health checkups in the workplace and in local communities. However, this recommended screening method was based on the complete DSM-IV, text revision (DSM-IV-TR) criteria, including eight or nine items to assess depression. A program to identify depression within a national population requires a simpler approach. Achieving the national goal of reducing suicide to 22,000 cases per year within the next 2 years requires identification of target groups and the implementation of extensive interventions directed at individuals within such target groups who are at highest risk.

In Japan, the government health care policy recognizes mental health as a top priority [11]. In 2005, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare organized the Strategic Research Group for the Management of Depression Related to Suicide [50]. The research group has planned to implement two types of intervention by 2010: one will assess the prevalence of suicide attempts in local communities and to develop a program for preventing suicide; the other will assess patients treated at emergency clinics following suicide attempts.

In June 2006, the fundamental law presenting the strategy for preventing suicide (Jisatsu Taisaku Kihonn Hou) was established. This Japanese law focuses on suicide prevention and supporting family members bereaved by suicide; it declares that national strategies are needed to increase awareness among the Japanese people of the problems related to suicide.

Intervention plan

Suicide prevention in the workforce requires the early identification of those workers at risk. There is conclusive evidence that behavioral changes can represent precursors of suicide in workers with various risk factors (e.g., psychiatric morbidity, low social support, and history of suicide attempts). However, suicidal behaviors usually follow long intervals during which harbingers of potential suicide may be detected. For example, the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare [11] summarized ten signs that should alert employers to possible suicide risks: depressive symptoms (e.g., depressed mood, self-reproach, and decreased work efficiency); prolonged somatic discomfort of unknown origin; increased alcohol consumption; difficulty in maintaining safety and health; rapid transformation in the working environment (e.g., increase in job demands, catastrophic work results, and job loss); inability to develop social support in the workplace or family; experience of important loss; severe physical disorders; expression of suicidal ideation; and attempted suicide. Supervisors must pay daily attention to the mental health of workers (supervisory lines) to identify such warning signs. Attendance by supervisors at regular training sessions to learn about active listening and psychological factors represents a promising strategy in this regard. The Japanese government has urged all employers to implement four approaches to comprehensive mental health care: a focus on individuals, utilizing supervisory lines, enlisting company health care staff, and referring to medical resources outside the company [51]. Since 2000, employee assistance programs (EAPs) have attracted a great deal of attention in Japan as promising medical resources outside the workplace. Originally, EAPs were employer-sponsored systems developed to restore or improve the functioning of workers whose personal problems were affecting job performance [51]; newer comprehensive EAPs engage in identification, assessment, monitoring, referral, short-term counseling, and follow-up activities with regard to the emotional, financial, legal, family, and substance-abuse concerns of employees. In this sense, comprehensive EAPs are new in Japan and primarily target the mental health care of employees. In a cohort study by Nakao et al. among 283 male Japanese employees at the same workplace who accessed EAP services [52], total scores on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Scale decreased significantly after the 2-year study period (P < 0.01); the changes in the scores on five items (i.e., suicidal thoughts, agitation, psychomotor retardation, guilt, and depressed mood) were significant. Specifically, 19 (86%) of the 22 workers with a positive response to the suicidal thoughts item (i.e., score ≥ 1) at baseline reported no suicidal thoughts (i.e., score = 0) after the 2-year study period. No significant changes were observed in the control group. These data suggest that the introduction of an EAP may decrease the frequency of suicidal thoughts in a working population.

Behavioral observations of unemployed individuals may provide a basis for classification of members of this group into three subsets [14, 53]: those pursuing either jobs or some activity (e.g., studying) in preparation for pursuing jobs; those spending their time at home without engaging in job-related activities; and those performing, or learning to perform, housekeeping in the absence of working outside the home [54]. Those classified into the first type of unemployment may be less likely to suffer from depression due to their active engagement in personal projects, suggesting that they may be excluded from the target population at high risk for depression. Some members of the second and third groups may be inactive due to symptoms of depression. As these individuals may be watching television or accessing the Internet, an antidepression campaign delivered via television and/or the Internet may represent an effective approach to address this subset of unemployed people. We recommend that communities and municipalities conduct advertising campaigns that enable those suffering from depression to identify their condition and that encourage them to consult psychological specialists if necessary.

Conclusions

A systematic reduction in the incidence of suicide in Japan will first require identification of those at high risk for depression, because most individuals who commit suicide are depressed. A simple screening method, such as that involving identification of physical discomfort, is required for implementation of depression screening on a national scale. This screening plan may result in overdiagnosis of depression. Indeed, the use of one or two questions with high sensitivity elicits only the core symptoms that are necessary but not sufficient for diagnosis. As a definitive diagnosis of depression requires a greater number of symptoms, a simple screening test may produce substantial numbers of false positives, i.e., individuals initially diagnosed as positive for depression but subsequently ruled out as suffering from this disorder. This screening plan, however, is proposed as a first and convenient test to identify depression. High sensitivity is far more important than low specificity in any effort to identify those suffering from depression, and marginal tests could improve specificity during subsequent screening processes [14].

Fulfillment of the national goal within the remaining 2 years will require the identification of target groups and the implementation of extensive interventions for high-risk individuals within these groups (e.g., middle-aged men with depression). Campaigns to educate those with the highest vulnerability to suicide are also needed to promote recognition and treatment.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported, in part, by a grant-in-aid, Project for the Activation of Young Investigators, from the Japanese Society for Hygiene (2005–2006).

References

- 1.World Health Organization. The World Health Report. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2003.

- 2.Bertolote JM. Foreword. In: Figures and facts about suicide. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1999;3–10.

- 3.World Health Organization. Prevention of suicidal behaviors: a task for all. (http://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide/supresuicideprevent/en/).

- 4.Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Vital statistics of Japan 2005, Japan. Health and Welfare Statistics Association, Tokyo, 2007 (in Japanese).

- 5.Yamamura T, Kinoshita H, Nishiguchi M, Hishida S. A perspective in epidemiology of suicide in Japan. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2006;63:575–83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Community Safety Bureau, National Police Agency. Suicide report in 2006. (http://www.npa.go.jp/toukei/chiiki8/20070607.pdf) (in Japanese).

- 7.Yamasaki A, Morgenthaler S, Kaneko Y, Shirakawa T. Trends and monthly variations in the historical record of suicide in Japan from 1976 to 1994. Psychol Rep. 2004;94:607–12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Shiho Y, Tohru T, Shinji S, Manabu T, Yuka T, Eriko T, et al. Suicide in Japan: present conditions and prevention measures. Crisis. 2005;26:12–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Nakao M, Yoshimasu K, Takeuchi T, Nakano M. Approach to prevention of suicide in clinical and occupational medicine [abstract]. Nippon Eiseigaku Zasshi. 2008;63:271–7 (in Japanese).

- 10.Pirkis J, Burgess P. Suicide and recency of health care contacts: a systemic review. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:462–74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Japanese Committee for Prevention of Suicide. A proposal for prevention of suicide: current status of suicide in Japan. (http://www.mhlw.go.jp/houdou/2002/12/h1218-3.html/) (in Japanese).

- 12.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed, text revision. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2000.

- 13.Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Patient Survey 2005 (All Japan), Volume 1. Tokyo: Health and Welfare Statistics Association, 2007 (in Japanese).

- 14.Nakao M, Takeuchi T. The suicide epidemic in Japan and strategies of depression screening for its prevention. Bull World Health Org. 2006;84:492–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Boxer PA, Burnett C, Swanson N. Suicide and occupation: a review of the literature. J Occup Environ Med. 1995;37:442–52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Stack S. Occupation and suicide. Soc Sci Quart. 2001;82:384–96. [DOI]

- 17.Wilhelm K, Kovess V, Rios-Seidel C, Finch A. Work and mental health. Soc Psychiatry Psychiat Epidemiol. 2004;39:866–73. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Karasek R. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job redesign. Adm Sci Q. 1979;24:285–308. [DOI]

- 19.Siegrist J, Peter R, Junge A, Cremer P, Seidel D. Low status control, high effort at work and ischemic heart disease: prospective evidence from blue-collar men. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47:2043–53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Stansfeld SA, Fuhrer R, Shipley MJ, Marmot MG. Work characteristics predict psychiatric disorder: prospective results from the Whitehall II Study. J Psychosom Res. 1997;43:73–81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Kreitman N, Carstairs V, Duffy J. Association of age and social class with suicide among men in Great Britain. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1991;45:195–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Ono Y, Tanaka E, Oyama H, Toyokawa K, Koizumi T, Shinohe K, et al. Epidemiology of suicidal ideation and help-seeking behaviors among the elderly in Japan. Psychiat Clin Neurosci. 2001;55:605–11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Tamakoshi A, Ohno Y, Yamada T, Aoki K, Hamajima N, Wada M, et al. Depressive mood and suicide among middle-aged workers: findings from a prospective cohort study in Nagoya, Japan. J Epidemiol. 2000;10:173–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Otsu A, Araki S, Sakai R, Yokoyama K, Scott Voorhees A. Effects of urbanization, economic development, and migration of workers on suicide mortality in Japan. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:1137–46. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Yamasaki A, Sakai R, Shirakawa T. Low income, unemployment, and suicide mortality rates for middle-aged persons in Japan. Psychol Rep. 2005;96:37–48. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Oyama H, Ono Y, Watanabe N, Tanaka E, Kudoh S, Sakashita T, et al. Local community intervention through depression screening and group activity for elderly suicide prevention. Psychiat Clin Neurosci. 2006;60:110–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Motohashi Y, Kaneko Y, Sasaki H, Yamaji M. A decrease in suicide rates in Japanese rural towns after community-based intervention by the health promotion approach. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2007;37:593–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.The Japanese Center of Comprehensive Measures for Suicide Prevention. Strategies of suicide prevention in self-governing bodies (http://www.ncnp.go.jp/ikiru-hp/torikumi.html) (in Japanese).

- 29.Nakao M, Yamanaka G, Kuboki T. Suicidal ideation and somatic symptoms of patients with mind/body distress in a Japanese psychosomatic clinic. Suic Life Threat Behav. 2002;32:80–90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Yoshimasu K, Sugahara H, Tokunaga S, Akamine M, Kondo T, Fujisawa K, et al. Gender differences in psychiatric symptoms related to suicidal ideation in Japanese patients with depression. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;60:563–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Beautrais AL. Gender issues in youth suicidal behaviour. Emerg Med (Fremantle). 2002;14:35–42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Stein D, Brom D, Elizur A, Witztum E. The association between attitudes toward suicide and suicidal ideation in adolescents. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1998;97:195–201. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, Greenwald S, Hwu HG, Joyce PR, et al. Prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in nine countries. Psychol Med. 1999;29:9–17. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Nakao M, Fricchione G, Zuttermeister PC, Myers P, Barsky AJ, Benson H. Effects of gender and marital status on somatic symptoms of patients attending a mind/body medicine clinic. Behav Med. 2001;26:159–68. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Derogatis LR. The SCL-90-R: administration, scoring and procedures manual II. Baltimore: Clinical Psychometric Research, 1992.

- 36.Takeuchi T, Nakao M, Yano E. Screening for major depression utilising a selected two-item questionnaire at workplace health examination. Prim Care Commun Psychiat. 2006;11:13–9. [DOI]

- 37.Nakao M, Yano E. Reporting of somatic symptoms as a screening marker for detecting major depression in a population of Japanese white-collar workers. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:1021–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Nakao M, Yamanaka G, Kuboki T. Major depression and somatic symptoms in a mind/body medicine clinic. Psychopathology. 2001;34:230–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Nakao M, Fricchione G, Myers P, Zuttermeister PC, Baim M, Mandle CL, et al. Anxiety is a good indicator for somatic symptom reduction through a behavioral medicine intervention in a mind/body medicine clinic. Psychother Psychosom. 2001;70:50–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Linzer M, Hahn SR, 3rd deGruy FV, et al. Physical symptoms in primary care: predictors of psychiatric disorders and functional impairment. Arch Fam Med. 1994;3:774–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Marple RL, Kroenke K, Lucey CR, Wilder J, Lucas CA. Concerns and expectations in patients presenting with physical complaints. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:1482–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Nakao M, Yano E. Prediction of major depression in Japanese adults: somatic manifestation of depression in annual health examinations. J Affect Disord. 2006;90:29–35. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Takeuchi T, Nakao M, Yano E. Symptomatology of depressive state in the workplace: a 20-year cohort study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008;43:343–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Whooley MA, Avins AL, Miranda J, Browner WS. Case-finding instruments for depression: two questions are as good as many. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:439–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Henkel V, Mergl R, Coyne JC, Kohnen R, Möller HJ, Hegerl U. Screening for depression in primary care: will one or two items suffice? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;254:215–23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Isshiki A, Nakao M, Yamaoka K, Yano E. Application of subjective symptom checklist for screening major depression by annual health examinations: a cross-validity study in the workplace. J Med Screen. 2004;11:207–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Tatara K. Guideline of “Health in Japan toward the 21st century (Kenko-Nippon-21)”. Tokyo: Gyousei; 2001 (in Japanese).

- 48.The Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Manual of management of depression. (http://www.mhlw.go.jp/shingi/2004/01/s0126-5.html#2) (in Japanese).

- 49.The Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Manual of strategy for facilitating management of depression. (http://www.mhlw.go.jp/shingi/2004/01/s0126-5.html#1) (in Japanese).

- 50.Japanese Multimodal Intervention Trials for Suicide Prevention. Two research tasks to be performed. (http://www.jfnm.or.jp/itaku/J-MISP/index.html) (in Japanese).

- 51.Colantonio A. Assessing the effects of employee assistance programs: a review of employee assistance program evaluations. Yale J Biol Med. 1989;62:13–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Nakao M, Nishikitani M, Shima S, Yano E. A 2-year cohort study on the impact of an employee assistance programme (EAP) on depression and suicidal thoughts in male Japanese workers. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2007;81:151–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Nakao M. Suicide in Japan. In: Shrivastava A (ed). Handbook of suicide behaviour. London: Gaskell. 2008 (in press).

- 54.Survey on Time Use and Leisure Activities 2004. Statistics Bureau, Director-General for Policy Planning (Statistical Standards) and Statistical Research and Training Institute, Tokyo (http://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/shakai/index.htm).