Abstract

A simple strategy for the induction of extracellular hydroxyl radical (OH) production by white-rot fungi is presented. It involves the incubation of mycelium with quinones and Fe3+-EDTA. Succinctly, it is based on the establishment of a quinone redox cycle catalyzed by cell-bound dehydrogenase activities and the ligninolytic enzymes (laccase and peroxidases). The semiquinone intermediate produced by the ligninolytic enzymes drives OH production by a Fenton reaction (H2O2 + Fe2+ → OH + OH− + Fe3+). H2O2 production, Fe3+ reduction, and OH generation were initially demonstrated with two Pleurotus eryngii mycelia (one producing laccase and versatile peroxidase and the other producing just laccase) and four quinones, 1,4-benzoquinone (BQ), 2-methoxy-1,4-benzoquinone (MBQ), 2,6-dimethoxy-1,4-benzoquinone (DBQ), and 2-methyl-1,4-naphthoquinone (menadione [MD]). In all cases, OH radicals were linearly produced, with the highest rate obtained with MD, followed by DBQ, MBQ, and BQ. These rates correlated with both H2O2 levels and Fe3+ reduction rates observed with the four quinones. Between the two P. eryngii mycelia used, the best results were obtained with the one producing only laccase, showing higher OH production rates with added purified enzyme. The strategy was then validated in Bjerkandera adusta, Phanerochaete chrysosporium, Phlebia radiata, Pycnoporus cinnabarinus, and Trametes versicolor, also showing good correlation between OH production rates and the kinds and levels of the ligninolytic enzymes expressed by these fungi. We propose this strategy as a useful tool to study the effects of OH radicals on lignin and organopollutant degradation, as well as to improve the bioremediation potential of white-rot fungi.

White-rot fungi are unique in their ability to degrade a wide variety of organopollutants (36, 47), mainly due to the secretion of a low-specificity enzyme system whose natural function is the degradation of lignin (11). Components of this system include laccase and/or one or two types of peroxidase, such as lignin peroxidase (LiP), manganese peroxidase (MnP), and versatile peroxidase (VP) (31). Besides acting directly, the ligninolytic enzymes can bring about lignin and pollutant degradation through the generation of low-molecular-weight extracellular oxidants, including (i) Mn3+, (ii) free radicals from some fungal metabolites and lignin depolymerization products (7, 22), and (iii) oxygen free radicals, mainly hydroxyl radicals (OH) and lipid peroxidation radicals (21). Although OH radicals are the strongest oxidants found in cultures of white-rot fungi (1), studies of their involvement in pollutant degradation are scarce. One of the reasons is that the mechanisms proposed for OH production still await in vivo validation.

Several potential sources of extracellular OH based on the Fenton reaction (H2O2 + Fe2+ → OH + OH− + Fe3+) have been postulated for white-rot fungi. In one case, an extracellular fungal glycopeptide has been shown to reduce O2 and Fe3+ to H2O2 and Fe2+ (45). Enzymatic sources include cellobiose dehydrogenase, LiP, and laccase. Among these, only cellobiose dehydrogenase is able to directly catalyze the formation of Fenton's reagent (33). The ligninolytic enzymes, however, act as an indirect source of OH through the generation of Fe3+ and O2 reductants, such as formate (CO2−) and semiquinone (Q−) radicals. The first time evidence was provided that a ligninolytic enzyme was involved in OH production, oxalate was used to generate CO2− in a LiP reaction mediated by veratryl alcohol (4). The proposed mechanism consisted of the following cascade of reactions: production of veratryl alcohol cation radical (Valc+) by LiP, oxidation of oxalate to CO2− by Valc+, reduction of O2 to O2− by CO2−, and a superoxide-driven Fenton reaction (Haber-Weiss reaction) in which Fe3+ was reduced by O2−. The OH production mechanism assisted by Q− was inferred from the oxidation of 2-methoxy-1,4-benzohydroquinone (MBQH2) and 2,6-dimethoxy-1,4-benzohydroquinone (DBQH2) by Pleurotus eryngii laccase in the presence of Fe3+-EDTA. The ability of Q− radicals to reduce both Fe3+ to Fe2+ and O2 to O2−, which dismutated to H2O2, was demonstrated (14). In this case, OH radicals were generated by a semiquinone-driven Fenton reaction, as Q− radicals were the main agents accomplishing Fe3+ reduction. The first evidence of the likelihood of this OH production mechanism being operative in vivo had been obtained from incubations of P. eryngii with 2-methyl-1,4-naphthoquinone (menadione [MD]) and Fe3+-EDTA (15). Extracellular OH radicals were produced on a constant basis through quinone redox cycling, consisting of the reduction of MD by a cell-bound quinone reductase (QR) system, followed by the extracellular oxidation of the resulting hydroquinone (MDH2) to its semiquinone radical (MD−). The production of extracellular O2− and H2O2 by P. eryngii via redox cycling involving laccase was subsequently confirmed using 1,4-benzoquinone (BQ), 2-methyl-1,4-benzoquinone, and 2,3,5,6-tetramethyl-1,4-benzoquinone (duroquinone), in addition to MD (16). However, the demonstration of OH production based on the redox cycling of quinones other than MD was still required.

In the present paper, we describe the induction of extracellular OH production by P. eryngii upon its incubation with BQ, 2-methoxy-1,4-benzoquinone (MBQ), 2,6-dimethoxy-1,4-benzoquinone (DBQ), and MD in the presence of Fe3+-EDTA. The three benzoquinones were selected because they are oxidation products of p-hydroxyphenyl, guaiacyl, and syringyl units of lignin (MD was included as a positive control). Along with laccase, the involvement of P. eryngii VP in the production of O2− and H2O2 from hydroquinone oxidation has also been reported (13). Since hydroquinones are substrates of all known ligninolytic enzymes, quinone redox cycling catalysis could involve any of them. Here, we demonstrate OH production by P. eryngii under two different culture conditions, leading to the production of laccase or laccase and VP. We also show that quinone redox cycling is widespread among white-rot fungi by using a series of well-studied species that produce different combinations of ligninolytic enzymes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and enzymes.

H2O2 (Perhydrol 30%) was obtained from Merck. 2-Deoxyribose, 1,10-phenanthroline, 2-thiobarbituric acid (TBA), and bovine liver catalase (EC 1.11.1.6) were purchased from Sigma. 2,6-Dimethoxyphenol (DMP), 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic (protocatechuic) acid, BQ, DBQ, MD, 1,4-benzohydroquinone (BQH2), and MBQH2 were from Aldrich. DBQH2 was prepared from DBQ by reduction with sodium borohydride (2). MBQ was synthesized by oxidation of MBQH2 with silver oxide (19). All other chemicals used were of analytical grade.

Laccase isoenzyme I (EC 1.10.3.2) and VP isoenzyme I from P. eryngii were produced and purified as previously described by Muñoz et al. (34) and Martínez et al. (32), respectively.

Organisms and culture conditions.

P. eryngii IJFM A169 (Fungal Culture Collection of the Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas) (= ATCC 90787 and CBS 613.91), Trametes versicolor IJFM A136, Phlebia radiata IJFM A588 (= CBS 184.83), Bjerkandera adusta IJFM A581 (= CBS 595.78), and Pycnoporus cinnabarinus IJFM A720 (= CECT 20448; Colección Española de Cultivos Tipo) were maintained at 4°C on 2% malt extract agar. Mycelial pellets were produced at 28°C in shaken (150 rpm) 250-ml conical flasks with 100 ml of a glucose-peptone (GP) medium containing 20 g glucose, 5 g peptone, 2 g yeast extract, 1 g KH2PO4, and 0.5 g MgSO4·7 H2O per liter (25). P. eryngii was also cultivated in the presence of 50 μM MnSO4 (GPMn medium). Inocula were prepared by homogenizing 10-day-old mycelium. The dry weight of the inocula was 0.1 g per 100 ml of medium.

Enzyme activities.

Laccase activity was assayed in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 5, using 10 mM DMP as a substrate and measuring the production of coerulignone (extinction coefficient at 469 nm [ɛ469] = 27,500 M−1 cm−1, when referring to the DMP concentration) (32). VP and MnP activities were estimated by Mn3+-tartrate complex formation (ɛ238 = 6,500 M−1 cm−1) in reaction mixtures containing 100 mM sodium tartrate buffer, pH 5, 100 μM MnSO4, and 100 μM H2O2 (32). LiP activity was assayed in 100 mM tartrate buffer, pH 3, as the oxidation of veratryl alcohol (2 mM) to veratraldehyde (ɛ310 = 9,300 M−1 cm−1) in the presence of 400 μM H2O2 (46). These enzymatic assays were performed at room temperature (22 to 25°C).

Mycelium washed with distilled water was used for the determination of cell-bound laccase, VP, and QR activities in P. eryngii. Laccase and VP activities were estimated as described above. To minimize underestimates of QR activity, BQ was selected, since laccase activity on BQH2 has been shown to be quite low (34). QR activity was determined in 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 5, using 500 μM BQ as a substrate and measuring the production of BQH2 by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Samples (20 μl) were injected into a Pharmacia system equipped with a Spherisorb S50DS2 column (Hichrom) and a diode array detector. The analyses were carried out at 40°C with a flow rate of 1 ml min−1 and 10 mM phosphoric acid-methanol (80/20) as an eluent. The UV detector operated at 280 nm, and BQH2 levels were estimated using a standard calibration curve. For these cell-bound analyses of enzymatic activities, appropriate amounts of mycelium were incubated at room temperature with 20-ml substrate solutions in shaken 100-ml conical flasks (150 rpm). Samples were taken at 1-min intervals for 5 min. The mycelium was separated from the liquid by filtration. Absorbance was determined immediately after filtration for laccase and VP activity measurements. The pH of samples used for QR activity determination was lowered to 2 with phosphoric acid, and they were kept frozen at −20°C until they were analyzed. International units of enzyme activity (μmol min−1) were used.

Incubation of fungi with quinones.

Ten-day-old mycelial pellets were collected from cultures by filtration, washed three times with distilled water, and resuspended in 50 ml of 20 mM phosphate buffer, pH 5, containing 500 μM BQ, MBQ, DBQ, or MD. The amount of mycelium used in these incubations was 202 ± 14 mg (dry weight). For Fe3+ reduction experiments, the complex 100 μM Fe3+-110 μM EDTA and 1.5 mM 1,10-phenanthroline were added to the quinone incubation solution. Iron salt (FeCl3) solutions were made up fresh immediately before use. In OH production experiments, 1,10-phenanthroline was replaced by either 2.8 mM 2-deoxyribose or 1 mM 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, depending on the method used to estimate OH generation (see below). Incubations were performed in 50-ml volumes at 28°C and 150 rpm in 100 ml conical flasks. Samples were periodically removed from three replicate flasks, and the extracellular fluid was separated from the mycelium by filtration. In order to inactivate the ligninolytic enzymes that could be released to the extracellular solution during the experiments, samples were treated in different ways depending on the kind of analysis to be performed. For the analysis of quinone, hydroquinone, protocatechuic acid, and TBA-reactive substances (TBARS), the pH of samples was lowered to 2 with phosphoric acid. For H2O2 estimation, samples were heated at 80°C for 20 min (a treatment that does not affect H2O2 levels). Other analyses were carried out immediately after the samples were removed.

Analytical techniques.

The Somogyi-Nelson method for the determination of reducing sugars was used to estimate glucose concentrations in fungal cultures (41).

Levels of MBQ, DBQ, and their corresponding hydroquinones were determined by HPLC, using standard calibration curves for each compound (17). Samples (20 μl) were injected into a Pharmacia system equipped with a Spherisorb S50DS2 column (Hichrom). The analyses were carried out at 40°C with a flow rate of 1 ml min−1 using 10 mM phosphoric acid-methanol (80/20) as the eluent. The UV detector operated at 254 and 280 nm.

H2O2 levels were estimated by measuring the production of O2 with a Clark-type electrode after the addition of 100 U of catalase per ml (heat-denatured catalase was used in blanks) (17). The amount of H2O2 was calculated taking into account the stoichiometry of the catalase reaction (2 H2O2:1 O2). The oxygen electrode was calibrated by the same procedure with known amounts of H2O2 from the standard commercial solution, which were calculated spectrophotometrically (ɛ230 = 81 M−1 cm−1).

The production of ferrous ion was measured at 510 nm by the formation of its chelate with 1,10-phenanthroline (ɛ = 12,110 M−1 cm−1) (4).

Both TBARS production from 2-deoxyribose (20) and conversion of 4-hydroxybenzoic acid into protocatechuic acid (12) were used as procedures to estimate OH production. TBARS were determined as follows. A total of 0.5 ml of 2.8% (wt/vol) trichloroacetic acid and 0.5 ml of 1% (wt/vol) TBA in 50 mM NaOH was added to 1-ml samples and heated for 10 min at 100°C. After the mixture cooled, the absorbance was read at 532 nm against appropriate blanks (18). Protocatechuic acid production was estimated by HPLC as described above for quinones, except a linear 10 mM phosphoric acid/methanol gradient from 0 to 30% methanol in 20 min was used as the mobile phase. The absorbance of the eluate was monitored at 254 nm (14).

Statistical analysis.

All the results included in the text and shown in the figures are the means and standard deviations of three replicates (full biological experiments and technical analyses). The least-squares method was used for regression analysis of data.

RESULTS

Following our previous studies of quinone redox cycling (15, 16), incubations of P. eryngii with quinones were carried out in buffered solutions (pH 5) and 10-day-old washed pellets. The fungus was grown in GP medium with or without Mn2+ in order to obtain pellets producing, respectively, only laccase (Lac-mycelium) or laccase plus VP (LacVP-mycelium) (32). In both cases, maximum growth was reached after 8 to 12 days, coinciding with glucose depletion (10 days). The mycelial dry weights in 10-day-old cultures carried out in GP and GPMn media were 808 ± 54 mg (average of three replicate flasks ± standard deviation). The levels of extracellular and cell-bound laccase, VP, and QR activities in 10-day-old cultures are listed in Table 1. The presence of Mn2+ in the culture medium repressed the production of VP (38), increased laccase activity, and had no significant effect on cell-bound QR activity.

TABLE 1.

Extracellular and cell-bound laccase, VP, and quinone reductase activities present in 10 day-old cultures of P. eryngii grown in GP and GPMn media

| Medium | Enzyme | Activity

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Culture liquid (mU ml−1) | Cell bound (mU mg−1) | ||

| GP | Lac | 24 ± 2 | 8 ± 1 |

| VP | 330 ± 13 | 4 ± 1 | |

| QR | NDa | 30 ± 3 | |

| GPMn | Lac | 57 ± 5 | 11 ± 2 |

| VP | 0 | 0 | |

| QR | ND | 28 ± 3 | |

ND, not determined.

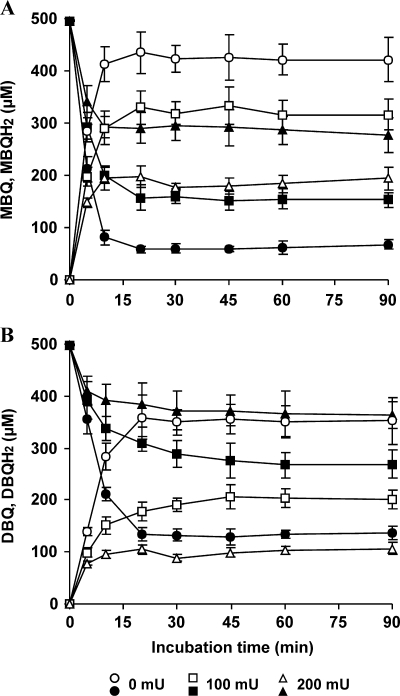

As previously reported for BQ and MD (16), MBQ and DBQ were redox cycled when incubated with washed Lac-mycelium (Fig. 1). Reduction of MBQ and DBQ to their corresponding QH2s was observed during the first 20 min. Then, QH2/Q molar ratios remained constant until the end of the experiment: 6.8 and 2.6 (average of 30- to 90-min samples) for MBQ and DBQ, respectively. These ratios were the result of equilibrium between QR and laccase activities as confirmed in parallel experiments carried out with added laccase. It was found that when the extracellular laccase activity was raised to 100 and 200 mU ml−1, QH2/Q ratios decreased, respectively, to 2.1 and 0.6 for MBQ and to 0.7 and 0.3 for DBQ. The lower ratios observed in incubations with DBQ agreed with the higher efficiency of laccase oxidizing DBQH2 than MBQH2 (17). These results indicated that oxidation of hydroquinones in the absence of added laccase was the rate-limiting step of MBQ and DBQ redox cycles, and therefore, that the enzyme addition increased the rates of these cycles.

FIG. 1.

Time course of MBQ (A) and DBQ (B) reduction by P. eryngii in the presence of different amounts of laccase (filled symbols, MBQ and DBQ; open symbols, MBQH2 and DBQH2). Incubations were carried out with 10-day-old Lac-mycelium and 500 μM quinones in 50 ml 20 mM phosphate buffer, pH 5, in the absence and presence of 100 and 200 mU ml−1 laccase. The error bars indicate standard deviations.

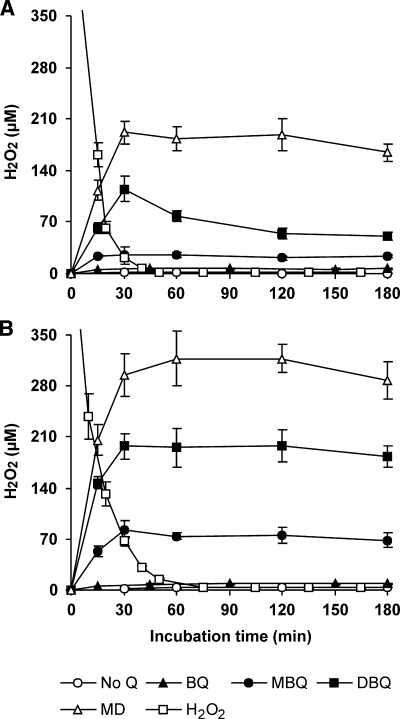

The production of H2O2 and reduction of Fe3+ by P. eryngii upon incubation with BQ, MBQ, DBQ, and MD was evaluated as a requisite for OH generation. Figure 2A and B shows the results for H2O2 production by LacVP-mycelium and Lac-mycelium, respectively. Regardless of the mycelium used, basal levels of extracellular H2O2 observed in 60- to 180-min samples remained around 2 to 3 μM with no quinone added. However, incubations carried out with quinones gradually increased H2O2 levels until steady values were attained (after 30 min). The average levels of 60- to 180-min samples increased in the order BQ < MBQ < DBQ < MD and were lower with LacVP-mycelium (6, 23, 61, and 179 μM, respectively) than with Lac-mycelium (8, 72, 192, and 308 μM, respectively). Figure 2 also shows that when P. eryngii mycelia were incubated with 500 μM H2O2, it nearly disappeared from the extracellular liquid in about 60 min. After this time, H2O2 levels were similar to those found without quinones (2 to 3 μM). Although this decrease in H2O2 levels was observed with both mycelia, indicating that they have one or more systems consuming it, the higher consumption rate observed with LacVP-mycelium suggested the involvement of VP. From these findings, it could be inferred that the steady H2O2 levels found in incubations with quinones were the result of equilibrium between the rates of production and consumption, and therefore, that quinone redox cycling was operative during the whole period studied.

FIG. 2.

Effects of quinones on the production of H2O2 by LacVP-mycelium (A) and Lac-mycelium (B) from P. eryngii. Mycelia were incubated in 50 ml 20 mM phosphate buffer, pH 5, in the absence (No Q) and presence of 500 μM BQ, MBQ, DBQ, or MD. Incubations with 500 μM H2O2 were also carried out in the absence of quinones. The error bars indicate standard deviations.

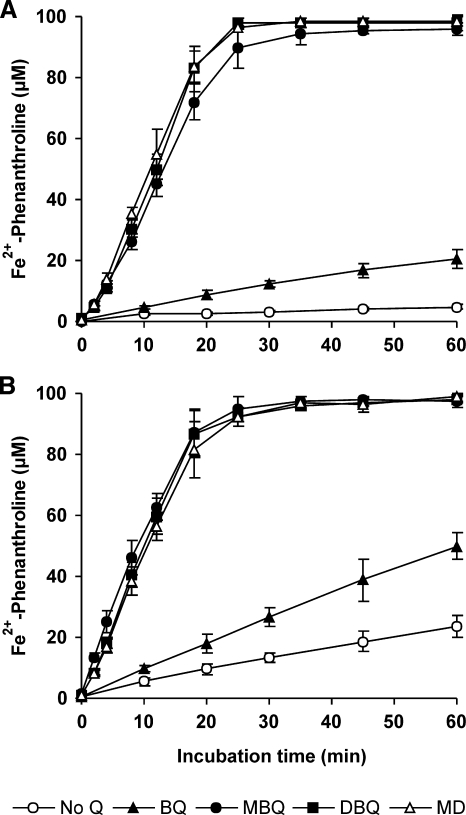

On the other hand, the effect of quinones on Fe3+ reduction by washed P. eryngii mycelia is shown in Fig. 3. Fe2+-phenanthroline complex from Fe3+-EDTA was linearly produced at different rates depending on the mycelium and quinone used. In the absence of quinones, basal iron reduction rates calculated from 0- to 60-min samples were 0.1 and 0.4 μM min−1 with LacVP- and Lac-mycelium, respectively. This observation supports the existence of a cell-bound mechanism for iron reduction which did not imply quinone redox cycling. Incubations with BQ raised these rates to 0.4 μM min−1 (LacVP-mycelium) and 0.9 μM min−1 (Lac-mycelium). A much greater increase was obtained in incubations with MBQ, DBQ, and MD, although no significant differences were found among them: 4.0 μM min−1 with LacVP-mycelium and 5.0 μM min−1 with Lac-mycelium, as calculated from the linear increase observed in 0- to 12-min samples. The Fe3+ was completely reduced and scavenged by phenanthroline with these three quinones in about 25 min.

FIG. 3.

Effects of quinones on the reduction of chelated Fe3+ by LacVP-mycelium (A) and Lac-mycelium (B) from P. eryngii. Mycelia were incubated in 50 ml 20 mM phosphate buffer, pH 5, in the absence (No Q) and presence of 500 μM BQ, MBQ, DBQ, or MD, with 100 μM Fe3+-110 μM EDTA and 1.5 mM 1,10-phenanthroline. The error bars indicate standard deviations.

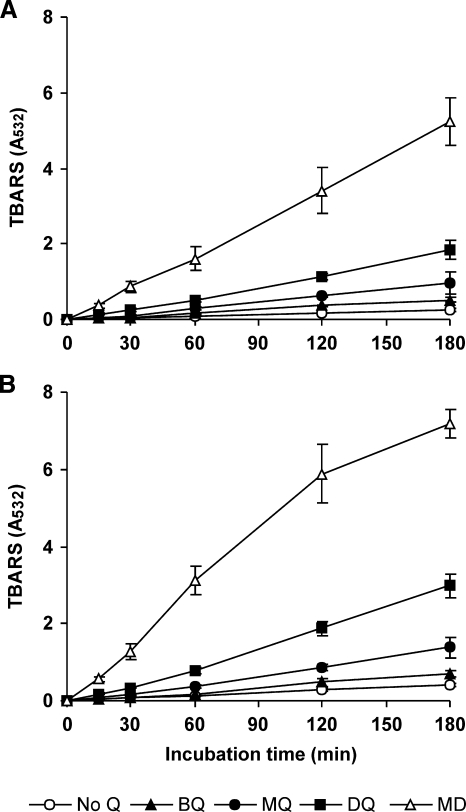

Following the demonstration of the formation of Fenton's reagent, production of OH was studied in incubations of washed mycelia with quinones and Fe3+-EDTA. Depending on the procedure used to detect OH, the incubation mixtures also contained either 2-deoxyribose or 4-hydroxybenzoic acid for the production of TBARS or protocatechuic acid, respectively. TBARS production was linear during the whole period studied with the four quinones and the two mycelia used (Fig. 4). The TBARS production rates were always higher with Lac-mycelium than with LacVP-mycelium. In both cases, the highest rate was obtained with MD, followed by DBQ, MBQ, and BQ. There existed, therefore, a positive correlation between TBARS levels and those of H2O2 shown in Fig. 2. Furthermore, taking into account that Fe2+ was produced at a rate similar to those of MBQ, DBQ, and MD (Fig. 3), it could be inferred that H2O2 was limiting the Fenton reaction during at least MBQ and DBQ redox cycling. TBARS production was also observed in the absence of quinones and the presence of Fe3+-EDTA, but at the lowest rates. This observation is in close agreement with the results in Fig. 3, showing the ability of P. eryngii to reduce Fe3+ with no Q. In addition to H2O2 basal levels generated by the fungus under these conditions (Fig. 2), OH production could be supported by that derived from ferrous iron autoxidation, followed by the dismutation of the resulting O2−.

FIG. 4.

Hydroxyl radical production by LacVP-mycelium (A) and Lac-mycelium (B) from P. eryngii via quinone redox cycling, estimated as TBARS formation from 2-deoxyribose. The incubation mixtures were as described in the legend to Fig. 3, except that 1,10-phenanthroline was replaced by 2.8 mM 2-deoxyribose. The error bars indicate standard deviations.

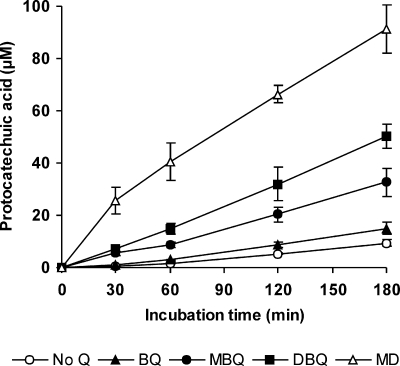

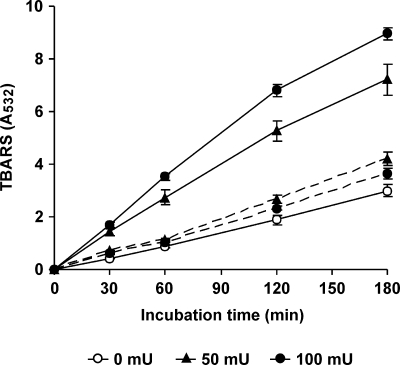

In order to confirm OH production, the effect of OH scavengers, such as mannitol and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), on TBARS formation was evaluated. Lac-mycelium was incubated with DBQ, Fe3+-EDTA, and 2-deoxyribose in the absence and presence of 5 mM mannitol or DMSO. The TBARS production rate during the first 120 min decreased from 14.8 mU A532 min−1 (incubation without scavengers) to 7.4 and 2.8 mU A532 min−1 with mannitol and DMSO, respectively. The production of OH was also confirmed by estimating the hydroxylation of 4-hydroxybenzoic acid during the redox cycling of the four quinones by Lac-mycelium. As shown in Fig. 5, protocatechuic acid was also produced on a constant basis throughout the experiment. Regression analyses of data obtained from 30- to 180-min samples produced the following rates of protocatechuic acid production: 64, 102, 199, 297, and 423 nM min−1 in incubations with no Q, BQ, MBQ, DBQ, and MD, respectively. The results in Fig. 1 revealed that oxidation of MBQH2 and DBQH2 was the rate-limiting step of the MBQ and DBQ redox cycles. Based on these results, the effects of increasing extracellular laccase and VP activities on OH production were evaluated. Figure 6 shows TBARS production during the incubation of Lac-mycelium with DBQ, Fe3+-EDTA, 2-deoxyribose, and different amounts of laccase and VP. The addition of 50 and 100 mU ml−1 laccase enhanced the TBARS production rate from 17 mU A532 min−1 (blank without added enzymes) to 40 and 50 mU A532 min−1, respectively, as calculated from the results obtained for 0- to 180-min samples. The addition of VP also caused an increase in the TBARS production rate, although much lower and inversely correlated with the amount of the enzyme: 23 and 20 mU A532 min−1 with 50 and 100 mU ml−1 of added VP, respectively.

FIG. 5.

Hydroxyl radical production by Lac-mycelium from P. eryngii via quinone redox cycling, estimated as 4-hydroxybenzoic acid hydroxylation. The incubation mixtures were as described in the legend to Fig. 3, except 1,10-phenanthroline was replaced by 1 mM 4-hydroxybenzoic acid. The error bars indicate standard deviations.

FIG. 6.

Effects of laccase and VP on hydroxyl radical (TBARS) production by Lac-mycelium from P. eryngii via DBQ redox cycling. The incubations were carried out in 50 ml 20 mM phosphate buffer, pH 5, containing Lac-mycelium, 500 μM DBQ, 100 μM Fe3+-110 μM EDTA, and 2.8 mM 2-deoxyribose, in the absence (0 mU) and presence of 50 and 100 mU ml−1 laccase (solid lines) and VP (dashed lines). The error bars indicate standard deviations.

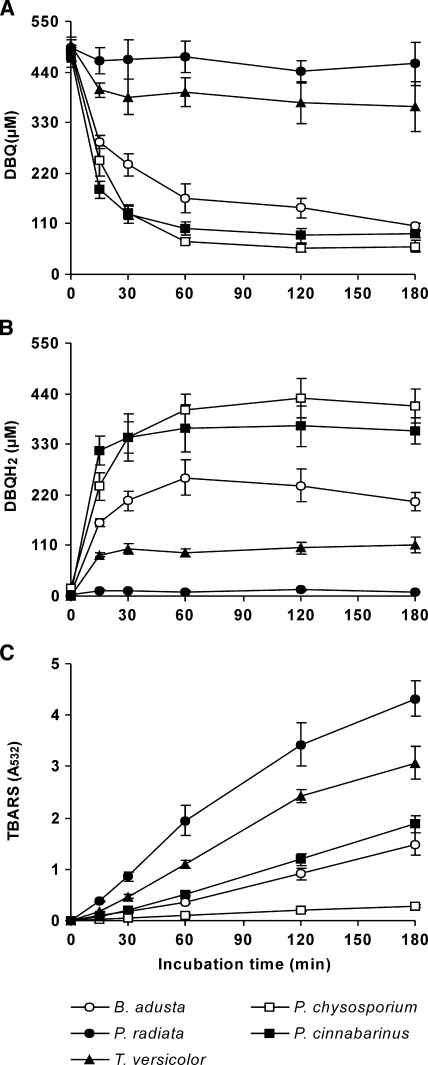

A final series of experiments was carried out in order to test the validity of this inducible OH production mechanism in other white-rot fungi: B. adusta, P. chrysosporium, P. radiata, P. cinnabarinus, and T. versicolor. Quinone redox cycling experiments were carried out with DBQ and 10-day-old washed mycelia grown in GP medium. The ligninolytic enzymes produced by the fungi under these culture conditions were LiP and a Mn2+-oxidizing peroxidase (VP) by B. adusta (30); laccase by P. cinnabarinus, T. versicolor, and P. radiata; and none by P. chrysosporium (Table 2). These different enzyme production patterns, including several levels of laccase, allowed us to study the effect of ligninolytic enzymes on OH production from both qualitative and quantitative points of view. Incubations of the fungi with DBQ were carried out in the presence of Fe3+-EDTA and 2-deoxyribose, and samples were analyzed for TBARS production, as well as for DBQ and DBQH2 levels (Fig. 7). Among the five fungi, P. chrysosporium produced TBARS at the lowest rate (2 mU A532 min−1 during a period from 0 to 120 min). Although the fungus showed a good ability to reduce DBQ, it is quite likely that the absence of ligninolytic enzymes limited the production of TBARS. The highest TBARS production rate, estimated during the same period, was obtained with P. radiata, followed by T. versicolor and P. cinnabarinus, i.e., 29, 21, and 10 mU A532 min−1, respectively (Fig. 7C). These results were positively correlated with laccase activity levels (Table 2), in agreement with the positive effect caused by the enzyme on TBARS production by P. eryngii (Fig. 6). Furthermore, the differences in laccase levels were also reflected in the DBQH2/DBQ ratios found at system equilibrium (Fig. 7A and B), similar to the results obtained with P. eryngii (Fig. 1). Thus, whereas DBQH2 was the prevalent compound in 60- to 180-min samples from the fungus producing the lowest laccase activity (P. cinnabarinus), DBQ was the prevalent compound with the best laccase producers (P. radiata and T. versicolor). A lower TBARS production rate was observed with B. adusta (8 mU A532 min−1), producing only ligninolytic peroxidases. However, it was four times higher than that observed with P. chrysosporium, indicating the involvement of these enzymes in DBQ redox cycling.

TABLE 2.

Extracellular laccase, MnP/VP, and LiP activities present in 10-day-old cultures of selected white-rot fungi grown in GP medium

| Species | Enzyme activity (mU ml−1)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Laccase | MnP/VP | LiP | |

| B. adusta | 0 | 38 ± 3 | 192 ± 15 |

| P. chrysosporium | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| P. radiata | 319 ± 22 | 0 | 0 |

| P. cinnabarinus | 19 ± 1 | 0 | 0 |

| T. versicolor | 217 ±14 | 0 | 0 |

FIG. 7.

Hydroxyl radical production by selected white-rot fungi via DBQ redox cycling. Levels of DBQ (A), DBQH2 (B), and TBARS (C) are shown. The incubation mixtures contained 50 ml 20 mM phosphate buffer, pH 5; 200 ± 12 mg 10-day-old mycelia from B. adusta, P. chrysosporium, P. radiata, P. cinnabarinus, and T. versicolor; 500 μM DBQ; 100 μM Fe3+-110 μM EDTA; and 2.8 mM 2-deoxyribose. TBARS levels were corrected from those found in incubation blanks without DBQ. The error bars indicate standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

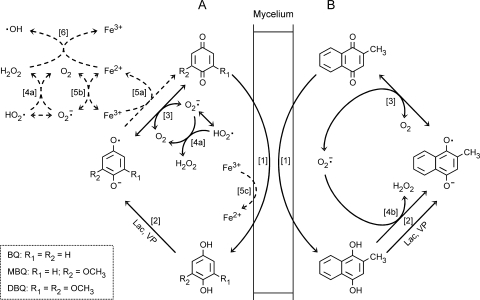

Our results provide in vivo validation of the Q−-assisted mechanism of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production previously demonstrated with purified laccases from P. eryngii (14, 17, 34) and Coriolopsis rigida (39), VP from P. eryngii, and MnP from Phanerochaete chrysosporium (13). They also support our earlier finding that quinone redox cycling is a mechanism for the production of extracellular O2− and H2O2 in P. eryngii (16). This mechanism can now be expanded to OH production, a greater number of quinones, and some widely studied white-rot fungi. The production of OH radicals has been inferred from the generation of Fe2+ and H2O2 (Fenton's reagent), as well as from the conversion of 2-deoxyribose into TBARS and the hydroxylation of 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, with the four parameters highly correlated. A definitive proof confirming OH identity would be required, such as electron spin resonance analysis. Overall, these results enable us to propose the scheme depicted in Fig. 8 as a model for extracellular OH production by white-rot fungi via quinone redox cycling. Although the scheme shows the main reactions involved in ROS production under the incubation conditions used in the present study, some steps of the process may present several alternatives (described below). As can be seen, two redox cycles are shown, one for the three benzoquinones (Fig. 8A) and the other for the naphthoquinone (Fig. 8B). Common reactions involved in the generation of Fenton's reagent in both cycles (reactions 4a, 5a to c, and 6) are shown only in Fig. 8A in order to avoid a crowded scheme. Figure 8B includes a distinctive reaction of MD redox cycling, i.e., propagation of MDH2 oxidation by O2− (reaction 4b), which, as discussed below, was probably the factor contributing most to the production of the highest levels of H2O2 and OH radicals with this quinone (Fig. 2 and 4, respectively). With the exception of the enzymatic oxidation of QH2, a similar quinone redox cycling process has been described in brown-rot fungi. These fungi produce several methoxyhydroquinones that can be chemically oxidized by Fe3+ (24). The mechanisms by which these fungi produce extracellular OH have been widely studied, since these radicals are considered the main agents causing the rapid cellulose depolymerization characteristic of brown rot (3). Thus, the involvement of QH2 in ROS production by brown-rot fungi has been evidenced not only under defined liquid incubation conditions, but also on cellulose and wood (8, 44). Quinone redox cycling in other biological systems has been extensively studied and described as an intracellular process consisting of the enzymatic one-electron reduction of Q, followed by the autoxidation of the resulting Q− (23). However, quinone redox cycling in white- and brown-rot fungi presents the distinctive characteristic of producing ROS in the extracellular environment due to the two-electron reduction of Q and the secretion of the resulting QH2.

FIG. 8.

Scheme of the quinone redox cycling process in P. eryngii (see Discussion for an explanation). (A) Main reactions involved in ROS production through BQ, MBQ, and DBQ redox cycling in the absence and presence of Fe3+-EDTA (solid and dashed arrows, respectively). (B) MD redox cycling, showing hydroquinone propagation by O2−. Reversible reactions are indicated by double arrows.

Quinone redox cycling in white-rot fungi is triggered by the actions of cell-bound enzymatic systems that reduce them to QH2 (Fig. 8, reaction 1). Studies carried out mainly with P. chrysosporium have described the existence of two different systems reducing quinones, i.e., intracellular dehydrogenases using NAD(P)H as electron donors [Q + NAD(P)H + H+ → QH2 + NAD(P)+] (6, 10) and a plasma membrane redox system (43). Two similar intracellular quinone reductases have been characterized in the brown-rot fungus Gloeophyllum trabeum (9). Our current research on the contributions of these systems to the reduction of quinones by P. eryngii has revealed that the plasma membrane redox system is not involved (data not shown). Following Q reduction, extracellular QH2 oxidation presents several possibilities. Being phenolic compounds, QH2s are susceptible to oxidation by any of the ligninolytic enzymes (Fig. 8, reaction 2). As inferred from the results shown in Fig. 1, 6, and 7, it is clear that oxidation of QH2 by laccase (4 QH2 + O2 → 4 Q− + 2 H2O + 4 H+) and peroxidases (2 QH2 + H2O2 → 2 Q− + H2O) increases the rates of quinone redox cycles and ROS production, provided Q reduction is the limiting reaction of the cycle. Chemical transformation of QH2 into Q− is also a possibility to consider, since other oxidants than enzymes are either present or produced in the course of redox cycling. First, QH2 autoxidation (QH2 + O2 → Q− + O2− + 2 H+), which is a spin-restricted reaction, has been documented to be catalyzed by transition metal ions (49). For instance, Fe3+, chelated or not with oxalate, has been shown to be the catalyst of QH2 oxidation in the redox cycling process described in brown-rot fungi (24, 44, 48). In the present study, special emphasis was placed on the involvement of the ligninolytic enzymes in quinone redox cycling. This is the reason why an iron complex preventing QH2 oxidation, such as Fe3+-EDTA (14), was used. The effect of replacing EDTA by oxalate on OH production by P. eryngii via DBQ redox cycling has already been determined and will be described in a separate publication from this study. Second, conversion of QH2 into Q− can be accomplished by comproportionation reaction (QH2 + Q ⇆ 2 Q− + 2 H+). This reaction has been demonstrated to trigger the “autoxidation” of several benzo- and naphthoquinones and is especially noticeable with QH2 substituted with strong electron-donating groups, including DBQH2 (37). The contribution of this reaction to the production of ROS could be evidenced in the absence of other enzymatic or chemical QH2 oxidants. For instance, the production of OH by P. chrysosporium during the DBQ redox cycle without producing any ligninolytic enzyme (Fig. 7) could be explained on the basis of this comproportionation reaction taking place. Third, the O2− derived from Q− autoxidation can propagate the oxidation of some QH2: QH2 + O2− → Q− + H2O2 (Fig. 8, reaction 4b). The existence of this reaction with the QH2 derived from the reduction of the four Qs studied here was previously determined by studying the effect of superoxide dismutase on either the rate of QH2 “autoxidation” or oxidation by laccase (16, 17). A negative effect indicative of suppression of QH2 propagation by O2− was observed only in the case of MDH2, in agreement with other reported studies (35).

In the absence of Fe3+-EDTA, the pronounced increase exerted by quinones on the production of extracellular H2O2 by P. eryngii (Fig. 2) evidenced the transformation of Q− into Q via autoxidation (Q− + O2 ⇆ Q + O2− [Fig. 8, reaction 3]), followed by O2− dismutation (O2− + HO2 + H+ → O2 + H2O2 [Fig. 8, reaction 4a]) and, in the case of MD, also by O2− reduction by MDH2 (reaction 4b). As Q− autoxidation is a reversible reaction, the continuous removal of both quinones by fungal reducing systems (Fig. 1) and of O2− by reactions 4a and b were among the factors contributing to the efficiency of quinone redox cycling as an H2O2 production mechanism. This was previously demonstrated in laccase reactions with MBQH2 and DBQH2 by the recycling of MBQ and DBQ with diaphorase (a reductase catalyzing the divalent reduction of quinones) (17). In this way, transformation of Q− into Q via autoxidation was favored over two competing reactions (not shown in Fig. 8): Q− dismutation (2 Q− + 2 H+ ⇆ QH2 + Q) and Q− laccase oxidation (4 Q− + O2 + 4 H+ → 4 Q + 2 H2O). With respect to the removal of O2− via spontaneous dismutation under the incubation conditions used here in redox cycling experiments (pH 5), it is quite likely that this was occurring around its optimum pH, as it implies the oxidation of O2− by the hydroperoxyl radical (HO2) in equilibrium with O2−, and the pK value of HO2 is 4.8 (5). In the presence of Fe3+-EDTA, the high enhancement of the rates of Fe3+ reduction (Fig. 3), TBARS production (Fig. 4), and 4-hydroxybenzoic acid hydroxylation (Fig. 5) caused by Q evidenced the production of OH by P. eryngii via Fenton's reagent formation. Reactions involved in this process are shown in Fig. 8. Under these conditions, Q− autoxidation is mainly catalyzed by Fe3+ (sum of reactions 5a, Q− + Fe3+ → Q + Fe2+, and 5b, Fe2+ + O2 ⇆ Fe3+ + O2−), leading to the production of OH radicals by a Q−-driven Fenton reaction (reactions 5a and 6) (14). Two other pathways that must be considered to contribute to OH generation, but to a lesser extent, are the O2−-driven Fenton reaction (reactions reverse 5b and 6), using the O2− produced by direct Q− autoxidation (reaction 3), and that caused by the reduction of Fe3+ by the unknown cell-bound system whose existence was inferred above from the results shown in Fig. 3 to 5 with no Q (reactions 5c and 6). Possible cell-bound systems catalyzing Fe3+ reduction are the plasma membrane redox system described in P. chrysosporium (42) and the plasma membrane reductase (Fre1 protein) involved in iron uptake by several fungi (26). In this regard, a possible role in controlling iron levels available for Fenton chemistry has been suggested for two P. chrysosporium ferroxidase activities, one of which is extracellular (28) and the other a component of the cell-bound iron uptake complex Fet3-Ftr1 (27).

One interesting characteristic of quinone redox cycling is the low substrate specificity of the enzymes participating in the process. The results obtained in the present study with three of the most representative quinones produced during the degradation of both softwood and hardwood lignins enhances the likelihood of extracellular ROS production by white-rot fungi through this mechanism. Quinones have been also shown to be common intermediates during the degradation of aromatic pollutants by these fungi (36). In this regard, it is likely that some of these quinone intermediates can act as redox cycling agents contributing to ROS production and thus to the degradation of the pollutant from which they derive. This could be the case with MD being an oxidation product of 2-methylnaphthalene. The high correlation observed between the levels of H2O2 (Fig. 2) and OH radicals (Fig. 4 and 5) allows us to use the same rationales to explain the differences found in both cases with the different quinones. It is quite likely that O2− reduction by MDH2 (Fig. 8, reaction 4b) was the main factor contributing to the production of the highest levels of H2O2 and OH during MD redox cycling for two reasons. First, it doubles the amount of H2O2 produced by O2− dismutation, which is the only reaction converting O2− into H2O2 with the three benzoquinones. Second, it increases the rate of QH2 oxidation, which is the limiting reaction of MBQ and DBQ redox cycles, as inferred from the results shown in Fig. 1, and the BQ redox cycle, as previously reported by Guillén et al. (16). In fact, the latter study showed that the concerted action of laccase and O2− increased MDH2 oxidation in such a way that MD reduction became the limiting reaction of its redox cycle. The differences observed in the extents of H2O2 and OH production during the redox cycles of the three benzoquinones (DBQ > MBQ > BQ) can be explained by considering the ability of Q− radicals to be autoxidized. This ability, estimated previously as the production of H2O2 during the oxidation of DBQH2, MBQH2 and BQH2 by purified laccase of P. eryngii, was shown to be DBQ− > MBQ− > BQ− (16, 17). Furthermore, the higher the laccase and VP activities on QH2, which have been reported to be DBQH2 > MBQH2 > BQH2 (13, 17), the higher the rate of the quinone redox cycle.

The induction of TBARS production by DBQ and Fe3+-EDTA in B. adusta, P. chrysosporium, P. radiata, P. cinnabarinus, and T. versicolor (Fig. 7) led us to conclude that quinone redox cycling is a widespread mechanism for ROS production among white-rot fungi, including O2−, H2O2, and OH radicals. This process can be operative in the absence of ligninolytic enzymes provided other QH2 oxidants are present, as reported with brown-rot fungi (24, 48) and shown here in the case of P. chrysosporium. However, the significance of QH2 enzymatic catalysis has been clearly evidenced by the following observations: the increase exerted by added laccase and VP on TBARS production by P. eryngii (Fig. 6) and the much higher TBARS production rates obtained with fungi expressing ligninolytic enzymes under the culture conditions used (Table 2 and Fig. 7). From the results shown in Fig. 4 and 7, it can be inferred that the enzyme playing a crucial role in terms of OH production was laccase. First, TBARS production by P. eryngii was found to be higher with Lac-mycelium than with LacVP-mycelium (Fig. 4). Second, TBARS production with the fungi expressing only laccase (P. radiata, P. cinnabarinus, and T. versicolor) was found to be higher than with the fungus expressing only peroxidases (B. adusta) (Fig. 7). This is not surprising, because oxidation of QH2 by peroxidases implies the consumption of part of the H2O2 required for OH generation. The participation of laccase in the production of highly reactive oxidants deserves more attention, since it could explain the solubilization and mineralization of lignin observed with some ascomycetes producing only this ligninolytic enzyme (29, 40).

In summary, the results shown in the present study provide new information on the mechanisms used by white-rot fungi to activate O2 in the extracellular environment. In addition, they supply the basis for a simple strategy that could be used in fundamental and practical studies, such as the determination of factors affecting OH production by quinone redox cycling, as well as the roles these radicals can play in lignin and organopollutant degradation by these fungi. In this regard, our current research in this field, carried out with P. eryngii and T. versicolor, is showing that the induction of extracellular OH radical production by quinones and iron occurs not only in incubations with washed mycelium, but also with whole fungal cultures during primary and secondary metabolism. This research is also revealing that the capability of these fungi to degrade pollutants is increased when quinone redox cycling is used as a strategy to induce the production of extracellular OH radicals (unpublished data).

Acknowledgments

The research was funded by two projects from the Comunidad de Madrid (GR/AMB/0812/2004 and S-0505/AMB0100) and one project from the Comunidad de Madrid-Universidad de Alcalá (CAM-UAH2005/065). The stays of V. Gomez-Toribio at the Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas and A. B. García-Martín at the Universidad de Alcalá were supported, respectively, by fellowships from the Comunidad de Madrid and the Universidad de Alcalá.

We thank P. R. Shearer for English revision.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 17 April 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Backa, S., J. Gierer, T. Reitberger, and T. Nilsson. 1993. Hydroxyl radical activity associated with the growth of white-rot fungi. Holzforschung 47:181-187. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker, W. 1941. Derivatives of pentahydroxybenzene, and a synthesis of pedicellin. J. Chem. Soc. 1941:662-670. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baldrian, P., and V. Valaskova. 2008. Degradation of cellulose by basidiomycetous fungi. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 32:501-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barr, D. P., M. M. Shah, T. A. Grover, and S. D. Aust. 1992. Production of hydroxyl radical by lignin peroxidase from Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 298:480-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bielski, B. H. J., and A. O. Allen. 1977. Mechanism of the disproportionation of superoxide radicals. J. Phys. Chem. 81:1048-1050. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brock, B. J., S. Rieble, and M. H. Gold. 1995. Purification and characterization of a 1,4-benzoquinone reductase from the basidiomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:3076-3081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Camarero, S., D. Ibarra, M. J. Martínez, and A. T. Martínez. 2005. Lignin-derived compounds as efficient laccase mediators for decolorization of different types of recalcitrant dyes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:1775-1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen, R., K. A. Jensen, C. J. Houtman, and K. E. Hammel. 2002. Significant levels of extracellular reactive oxygen species produced by brown rot basidiomycetes on cellulose. FEBS Lett. 531:483-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen, R., M. R. Suzuki, and K. E. Hammel. 2004. Differential stress-induced regulation of two quinone reductases in the brown rot basidiomycete Gloeophyllum trabeum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:324-331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Constam, D., A. Muheim, W. Zimmermann, and A. Fiechter. 1991. Purification and partial characterization of an intracellular NADH:quinone oxidoreductase from Phanerochaete chrysosporium. J. Gen. Microbiol. 137:2209-2214. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cullen, D., and P. J. Kersten. 2004. Enzymology and molecular biology of lignin degradation, p. 249-312. In R. Brambl and G. A. Marzluf (ed.), The Mycota. III. Biochemistry and molecular biology. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany.

- 12.Forney, L. J., C. A. Reddy, M. Tien, and S. D. Aust. 1982. The involvement of hydroxyl radical derived from hydrogen peroxide in lignin degradation by the white rot fungus Phanerochaete chrysosporium. J. Biol. Chem. 257:11455-11462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gómez-Toribio, V., A. T. Martínez, M. J. Martínez, and F. Guillén. 2001. Oxidation of hydroquinones by the versatile ligninolytic peroxidase from Pleurotus eryngii: H2O2 generation and the influence of Mn2+. Eur. J. Biochem. 268:4787-4793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guillén, F., V. Gómez-Toribio, M. J. Martínez, and A. T. Martínez. 2000. Production of hydroxyl radical by the synergistic action of fungal laccase and aryl alcohol oxidase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 383:142-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guillén, F., M. J. Martínez, and A. T. Martínez. 1996. Hydroxyl radical production by Pleurotus eryngii via quinone redox-cycling, p. 389-392. In K. Messner and E. Srebotnik (ed.), Biotechnology in the pulp and paper industry: recent advances in applied and fundamental research. Facultas-Universitätsverlag, Vienna, Austria.

- 16.Guillén, F., M. J. Martínez, C. Muñoz, and A. T. Martínez. 1997. Quinone redox cycling in the ligninolytic fungus Pleurotus eryngii leading to extracellular production of superoxide anion radical. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 339:190-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guillén, F., C. Muñoz, V. Gómez-Toribio, A. T. Martínez, and M. J. Martínez. 2000. Oxygen activation during the oxidation of methoxyhydroquinones by laccase from Pleurotus eryngii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:170-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gutteridge, J. M. C. 1984. Reactivity of hydroxyl and hydroxyl-like radicals discriminated by release of thiobarbituric acid-reactive material from deoxy sugars, nucleosides and benzoate. Biochem. J. 224:761-767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haemmerli, S. D., H. E. Schoemaker, H. W. H. Schmidt, and M. S. A. Leisola. 1987. Oxidation of veratryl alcohol by the lignin peroxidase of Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Involvement of activated oxygen. FEBS Lett. 220:149-154. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halliwell, B., and J. M. C. Gutteridge. 1981. Formation of a thiobarbituric-acid-reactive substance from deoxyribose in the presence of iron salts. FEBS Lett. 128:347-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hammel, K. E., A. N. Kapich, K. A. Jensen, and Z. C. Ryan. 2002. Reactive oxygen species as agents of wood decay by fungi. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 30:445-453. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johannes, C., and A. Majcherczyk. 2000. Natural mediators in the oxidation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by laccase mediator systems. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:524-528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kappus, H., and H. Sies. 1981. Toxic drug effects associated with oxygen metabolism: redox cycling and lipid peroxidation. Experientia 37:1233-1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kerem, Z., K. A. Jensen, and K. E. Hammel. 1999. Biodegradative mechanism of the brown rot basidiomycete Gloeophyllum trabeum: evidence for an extracellular hydroquinone-driven Fenton reaction. FEBS Lett. 446:49-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kimura, Y., Y. Asada, and M. Kuwahara. 1990. Screening of basidiomycetes for lignin peroxidase genes using a DNA probe. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 32:436-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kosman, D. J. 2003. Molecular mechanisms of iron uptake in fungi. Mol. Microbiol. 47:1185-1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larrondo, L. F., P. Canessa, F. Melo, R. Polanco, and R. Vicuna. 2007. Cloning and characterization of the genes encoding the high-affinity iron-uptake protein complex Fet3/Ftr1 in the basidiomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Microbiology 153:1772-1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larrondo, L. F., L. Salas, F. Melo, R. Vicuña, and D. Cullen. 2003. A novel extracellular multicopper oxidase from Phanerochaete chrysosporium with ferroxidase activity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:6257-6263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liers, C., R. Ullrich, K. T. Steffen, A. Hatakka, and M. Hofrichter. 2006. Mineralization of 14C-labelled synthetic lignin and extracellular enzyme activities of the wood-colonizing ascomycetes Xylaria hypoxylon and Xylaria polymorpha. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 69:573-579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martínez, A. T. 2002. Molecular biology and structure-function of lignin-degrading heme peroxidases. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 30:425-444. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martínez, A. T., M. Speranza, F. J. Ruiz-Duenas, P. Ferreira, S. Camarero, F. Guillén, M. J. Martínez, A. Gutiérrez, and J. C. del Río. 2005. Biodegradation of lignocellulosics: microbial, chemical, and enzymatic aspects of the fungal attack of lignin. Int. Microbiol. 8:195-204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martínez, M. J., F. J. Ruiz-Dueñas, F. Guillén, and A. T. Martínez. 1996. Purification and catalytic properties of two manganese-peroxidase isoenzymes from Pleurotus eryngii. Eur. J. Biochem. 237:424-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mason, M. G., P. Nicholls, and M. T. Wilson. 2003. Rotting by radicals—the role of cellobiose oxidoreductase? Biochem. Soc. Trans. 31:1335-1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muñoz, C., F. Guillén, A. T. Martínez, and M. J. Martínez. 1997. Laccase isoenzymes of Pleurotus eryngii: characterization, catalytic properties and participation in activation of molecular oxygen and Mn2+ oxidation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:2166-2174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Öllinger, K., G. D. Buffinton, L. Ernster, and E. Cadenas. 1990. Effect of superoxide dismutase on the autoxidation of substituted hydro- and semi-naphthoquinones. Chem. Biol. Interact. 73:53-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pointing, S. B. 2001. Feasibility of bioremediation by white-rot fungi. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 57:20-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roginsky, V. A., L. M. Pisarenko, W. Bors, and C. Michel. 1999. The kinetics and thermodynamics of quinone-semiquinone-hydroquinone systems under physiological conditions. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2:871-876. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ruiz-Dueñas, F. J., F. Guillén, S. Camarero, M. Pérez-Boada, M. J. Martínez, and A. T. Martínez. 1999. Regulation of peroxidase transcript levels in liquid cultures of the ligninolytic fungus Pleurotus eryngii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:4458-4463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saparrat, M. C. N., F. Guillén, A. M. Arambarri, A. T. Martínez, and M. J. Martínez. 2002. Induction, isolation, and characterization of two laccases from the white-rot basidiomycete Coriolopsis rigida. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1534-1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shary, S., S. A. Ralph, and K. E. Hammel. 2007. New insights into the ligninolytic capability of a wood decay ascomycete. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:6691-6694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Somogyi, M. 1945. A new reagent for the determination of sugars. J. Biol. Chem. 160:61-73. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stahl, J. D., and S. D. Aust. 1995. Properties of a transplasma membrane redox system of Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 320:369-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stahl, J. D., S. J. Rasmussen, and S. D. Aust. 1995. Reduction of quinones and radicals by a plasma membrane redox system of Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 322:221-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suzuki, M. R., C. G. Hunt, C. J. Houtman, Z. D. Dalebroux, and K. E. Hammel. 2006. Fungal hydroquinones contribute to brown rot of wood. Environ. Microbiol. 8:2214-2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tanaka, H., S. Itakura, and A. Enoki. 1999. Hydroxyl radical generation by an extracellular low-molecular-weight substance and phenol oxidase activity during wood degradation by the white-rot basidiomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Holzforschung 53:21-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tien, M., and T. K. Kirk. 1984. Lignin-degrading enzyme from Phanerochaete chrysosporium: purification, characterization, and catalytic properties of a unique H2O2-requiring oxygenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:2280-2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tortella, G. R., M. C. Diez, and N. Durán. 2005. Fungal diversity and use in decomposition of environmental pollutants. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 31:197-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Varela, E., and M. Tien. 2003. Effect of pH and oxalate on hydroquinone-derived hydroxyl radical formation during brown rot wood degradation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:6025-6031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang, L. P., B. Bandy, and A. J. Davison. 1996. Effects of metals, ligands and antioxidants on the reaction of oxygen with 1,2,4-benzenetriol. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 20:495-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]