Abstract

Lactobacillus bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus, used in yogurt starter cultures, are well known for their stability and protocooperation during their coexistence in milk. In this study, we show that a close interaction between the two species also takes place at the genetic level. We performed an in silico analysis, combining gene composition and gene transfer mechanism-associated features, and predicted horizontally transferred genes in both L. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus. Putative horizontal gene transfer (HGT) events that have occurred between the two bacterial species include the transfer of exopolysaccharide (EPS) biosynthesis genes, transferred from S. thermophilus to L. bulgaricus, and the gene cluster cbs-cblB(cglB)-cysE for the metabolism of sulfur-containing amino acids, transferred from L. bulgaricus or Lactobacillus helveticus to S. thermophilus. The HGT event for the cbs-cblB(cglB)-cysE gene cluster was analyzed in detail, with respect to both evolutionary and functional aspects. It can be concluded that during the coexistence of both yogurt starter species in a milk environment, agonistic coevolution at the genetic level has probably been involved in the optimization of their combined growth and interactions.

Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus (Lactobacillus bulgaricus) and Streptococcus thermophilus have been used in starter cultures for yogurt manufacturing for thousands of years. Both species are known to stably coexist in a milk environment and interact beneficially. This so-called protocooperation, previously defined as biochemical mutualism, involves the exchange of metabolites and/or stimulatory factors (38). Examples of biochemical protocooperation between L. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus include the action of cell wall-bound proteases, produced by L. bulgaricus strains, and formate, required for growth of L. bulgaricus and supplied by S. thermophilus (6, 7). An overview of the interactions between the two yogurt bacteria, including the exchange of CO2, pyruvate, folate, etc., can be found in a recently published review by Sieuwerts et al. (43). Putative genetic mechanisms underlying protocooperation, however, so far have not been studied in detail.

The genomes of two L. bulgaricus strains and three S. thermophilus strains, all used in yogurt manufacturing, have been fully sequenced (3, 32, 33, 34, 39, 44, 46). The available genomic information could provide new insights into the genetic aspects of protocooperation between L. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus through the identification of putative horizontal gene transfer (HGT) events at the genome scale. HGT can be defined as the exchange of genetic material between phylogenetically unrelated organisms (23). It is considered to be a major factor in the process of environmental adaptation, for both individual species and entire microbial populations. Especially HGT events between two species existing in the same niche can reflect their interrelated activities and dependencies (13, 17). Nicolas et al. (36) predicted HGT events between Lactobacillus acidophilus and Lactobacillus johnsonii by analyzing 401 phylogenetic trees, also including the genes of L. bulgaricus. Several HGT events have been predicted in the S. thermophilus strains CNRZ1066 and LMG 18311 (3, 10, 18) as well as in L. bulgaricus ATCC 11842 (46). Moreover, a core genome of S. thermophilus and possibly acquired genes were identified by a comparative genome hybridization study of 47 strains (40).

In this study, we describe an in-depth bioinformatics analysis in which we combined gene composition (GC content and dinucleotide composition) and gene transfer mechanism-associated features. Thus, we predicted horizontally transferred genes and gene clusters in the five sequenced L. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus genomes, with a focus on niche-specific genes and genes required for bacterial growth. Identification of HGT events led to a list of putative transferred genes, some of which could be important for bacterial protocooperation and the adaptation to their environment. The evolution and function of the transferred gene cluster cbs-cblB(cglB)-cysE (originally called cysM2-metB2-cysE2 in S. thermophilus), involved in the metabolism of sulfur-containing amino acids, were analyzed in detail. On the basis of our analysis, it can be concluded that both species probably agonistically coevolved at the genetic level to optimize their combined growth in a milk environment and that protocooperation thus includes both biochemical and genetic aspects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genome sequences.

The complete genome sequences of L. bulgaricus ATCC 11842 (46), L. bulgaricus ATCC BAA365, S. thermophilus LMD9 (33), S. thermophilus CNRZ1066, S. thermophilus LMG 18311 (3), and Lactobacillus helveticus DPC 4571 (4) were obtained from the NCBI GenBank Entrez Genome database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/lproks.cgi) under GenBank accession numbers CR954253, CP000412, CP000419, CP000024, CP000023, and CP000517, respectively (Table 1). The L. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus strains are isolated from either yogurt or industrial yogurt starter cultures.

TABLE 1.

General features of the published L. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus genomesa

| Strain | Size (bp) | GC content (%) | No. of predicted ORFsb | Coding density (%) | No. of genes associated with metabolic pathways |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactobacillus bulgaricus | |||||

| ATCC 11842 | 1,864,998 | 49.72 | 1,562 | 75 | 900 |

| ATCC BAA365 | 1,856,951 | 49.69 | 1,721 | 79 | 883 |

| Streptococcus thermophilus | |||||

| CNRZ1066 | 1,796,226 | 39.08 | 1,915 | 85 | 864 |

| LMG 18311 | 1,796,846 | 39.09 | 1,892 | 85 | 820 |

| LMD9 | 1,856,368 | 39.07 | 1,716 | 78 | 788 |

Data adapted from the ERGO Bioinformatics Suite (37).

Since the open reading frames (ORFs) from the bacterial genomes were predicted with various methodologies by different groups, annotations could be inconsistent, especially for the pseudogenes. Therefore, the number of predicted ORFs should be treated with caution. For the horizontally transferred genes predicted in this study, errors derived from inconsistent ORF predictions, especially regarding annotations of pseudogenes and misannotated genes, have been corrected using the whole-genome comparison (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

Whole-genome comparison.

Genome sequences of the two L. bulgaricus strains and three S. thermophilus strains were aligned using the software package Mauve 2.0 (http://asap.ahabs.wisc.edu/mauve/) (8). Mauve 2.0 can efficiently construct multiple genome sequence alignments with modest computational resource requirements. The tool is used for identifying genomic recombination events (such as gene loss, duplication, rearrangement, and horizontal transfer) and characterizing the rates and patterns of genome evolution. Mauve 2.0 uses an anchored alignment technique to rapidly align genomes and allows the order of those anchors to be rearranged to detect genome rearrangements. The anchors, local collinear blocks (LCBs), represent homologous regions of sequence shared by multiple genomes. Mauve 2.0 requires that each collinear region of the alignment meet “minimum weight” criteria in order to identify and discard random matches. The weight of an LCB is defined as the sum of the lengths of matches in the LCB, and the minimum weight is a user-definable parameter. The minimum weight of the LCB used in this analysis was 41 and 46 for the S. thermophilus and L. bulgaricus genomes, respectively. After removing the low-weight LCBs from the set of alignment anchors, Mauve 2.0 could complete a gapped global alignment for each LCB.

HGT analysis.

Putative HGT events between L. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus strains were first detected by whole-genome comparison using Mauve 2.0. The whole-genome alignments were manually inspected to identify putative horizontally transferred genes. Sequence composition analysis was carried out, including the calculation of GC composition (of 600-bp fragments) and dinucleotide dissimilarity value δ (of 1,000-bp fragments) along the whole genome, using the δρ-Web tool (48) (see Fig. S2 and S3 in the supplemental material). Identification of HGT events by using composition differences is based on previous observations by Karlin et al. (24, 25) that each genome has a typical dinucleotide frequency and that related species have similar genome signatures. A high genomic dissimilarity between an input sequence and a representative genome sequence of the species from which the sequence was isolated suggests a heterologous origin of the input sequence. In other words, horizontally acquired genes can have a very different sequence dinucleotide composition compared to that of the genome in which they presently reside, and the difference can be expressed by the δ value. DNA fragments with significantly different GC composition and/or dinucleotide composition (average ± two standard deviations) compared to those of the whole genomes were predicted to be HGT regions.

The predicted horizontally transferred genes and gene clusters were checked for HGT mechanism-associated features such as neighboring mobile elements or tRNA genes using Artemis (41) and Mauve 2.0. Homologs of the genes that were predicted to be transferred between S. thermophilus and L. bulgaricus were collected by performing BLASTP searches (1) against all the available genomes of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) or the nonredundant NCBI protein database. Homologous sequences were aligned with MUSCLE (12), and phylogenetic trees were constructed using the neighborhood-joining method implemented in ClustalW (30). The phylogenetic trees were visualized in LOFT (47). The positions of orthologs from L. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus in the phylogenetic trees were checked to confirm whether the predicted genes are genes that are horizontally transferred between the two genomes.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Through HGT, a genome can be rearranged by the integration and/or deletion of genetic elements, one of the driving forces in the evolution of organisms (50). HGT events can be detected using phylogenetic and compositional approaches. Information on gene transfer mechanisms, for instance, transposases or bacteriophage-related genes found in the neighborhood of the target genes, can improve the prediction of HGT events (50). In order to reveal protocooperation between the two coexisting yogurt species on the genetic level and to understand the rationale of their coevolution, putative HGT events were predicted and analyzed. HGT events, detected by combining composition analysis or phylogenetic analysis and gene transfer mechanism-associated features, are described for both S. thermophilus and L. bulgaricus strains.

Putative HGT from foreign origin to S. thermophilus.

Previously, Hols et al. (18) identified putative HGT events in the genomes of S. thermophilus strains CNRZ1066 and LMG 18311. In this study, we predicted the horizontally transferred genes in the S. thermophilus LMD9 genome and also thoroughly reanalyzed the genomes of S. thermophilus strains CNRZ1066 and LMG 18311 based on both gene composition and gene transfer mechanism-associated features. In order to identify strain-specific regions and indications for gene transfer or locus rearrangement, genome alignments of the strains from each species were performed (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The alignment of the three S. thermophilus genomes showed that strain LMD9 has undergone more genome rearrangements than both other strains. Strain CNRZ1066 and strain LMG 18311 share a more conserved genome context (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material).

Gene composition analysis, including GC content (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material) and dinucleotide composition (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material) analyses, revealed a list of putative horizontally transferred genes in the three S. thermophilus strains (Table 2; see also Table S1 in the supplemental material). In total, 197 genes were predicted as potentially acquired in the three S. thermophilus genomes, of which 118 genes are located in 28 gene clusters (Table 2). Over 60% of those genes were found to be associated with gene transfer mechanism-associated features, such as transposase, bacteriophage, and tRNA genes (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Compared with the core gene set of 47 S. thermophilus strains, identified by a recent comparative genomic hybridization study (40), 30 of the core genes overlapped with our HGT prediction. Since most of these core genes are not found to be associated with any mobile element or located in a predicted HGT gene cluster, they may be incorrectly predicted to be horizontally transferred by the gene composition analysis (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

TABLE 2.

Proposed horizontally transferred genes and gene clusters in S. thermophilus genomesa

| Gene cluster with | Gene ID(s) for strainb:

|

GC content (%)c | δ Value (103)d | δ Plot position (%)e | HGT mechanism-associated feature(s) | Function(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LMG 18311 | CNRZ1066 | LMD9 | ||||||

| Low GC content | ||||||||

| S1 | 0098, 0099, 0100, 0102, 0103, 0108 | 0098, 0099, 0100, 0102, 0103 | 0131, 0133, 0134, 0135 | 30 | 64 | 75 | Transposase, phage integrase | Lantibiotic/bacteriocin biosynthesis protein or exporter,f phage integrase, and hypothetical proteins |

| S2 | 0141, 0142, 0143, 0144, 0145 | 36 | 90 | 98 | Transposase | ABC-type peptide transport system | ||

| S3 | 0146, 0148, 0149, 0150 | 36 | 63 | 75 | Transposase | Bacteriocin exporter, EPS-related protein | ||

| S4 | 0182, 0183 | 0182,g 0183 | 30 | 102 | 97 | Transcriptional regulator,g putative protein kinasef | ||

| S5 | 0324, 0325, 0328 | 0324, 0325, 0328 | 1694 | 28 | 56 | 49 | Transposase | ABC-type transporter, hypothetical proteinf |

| S6 | 0683, 0684, 0685, 0686, 0687, 0688, 0689, 0690 | 27 | 73 | 89 | Transposase | Hypothetical proteins | ||

| S7 | 0706, 0707, 0709 | 0706, 0707, 0709 | 29 | 107 | 98 | Phage | Hypothetical proteinsf | |

| S8 | 0811, 0812, 0814, 0817 | 31 | 103 | 88 | Transposase, phage | Hypothetical proteins | ||

| S9 | 0774, 0782 | 32 | 125 | 85 | Phage | Hypothetical protein, phage-associated proteins | ||

| S10 | 1057, 1059, 1060, 1061, 1062, 1066 | 30 | 112 | 99.7 | Transposase | EPS biosynthesis | ||

| S11 | 1041, 1042, 1043, 1044 | 1037, 1040, 1041, 1042, 1044g | 29 | 48 | 57 | Transposase | UDP-N-acetylglucosamine enolpyruvyl transferase, regulator for MutR family,g hypothetical protein, tyrosyl-tRNA synthetasef | |

| S12 | 1077, 1078, 1079, 1080, 1081, 1082 | 30 | 67 | 83 | Transposase | EPS biosynthesisf | ||

| S13 | 1091, 1092, 1093, 1094, 1095, 1096, 1097, 1098, 1099, 1100, 1102 | 30 | 84 | 99 | Transposase | EPS biosynthesisf | ||

| S14 | 1296, 1297, 1298, 1299, 1300, 1301 | 27 | 94 | 98 | Macrolide efflux protein, peptidase F, regulator for MutR family, hydrolase, hypothetical proteins | |||

| S15 | 1328, 1329 | 29 | 68 | 30 | UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase, hypothetical protein | |||

| S16 | 1393 | 1393 | 1351, 1352, 1355, 1356, 1358 | 30 | 71 | 90 | Transposase | Multidrug efflux protein, regulator for MutR family, hypothetical proteinsf |

| S17 | 1479, 1480 | 1441, 1442, 1443 | 30 | 48 | 46 | Glycosyltransferase involved in cell wall biogenesis and transcriptional activator amrA | ||

| S18 | 1481, 1484, 1486 | 1445 | 31 | 69 | 78 | Hypothetical membrane proteinsf | ||

| S19 | 1474, 1475, 1476, 1477 | 31 | 66 | 89 | CRISPR system-related proteinsh | |||

| S20 | 1512, 1514 | 1512, 1514 | 29 | 112 | 94 | Hypothetical proteinsf | ||

| S21 | 1693, 1698 | 30 | 64 | 51 | Transposase | Regulator for Xre family, abortive infection phage resistance protein | ||

| S22 | 1943, 1944 | 1915, 1916 | 27 | 89 | 87 | Transposase | Bacteriocin-related proteins | |

| S23 | 1947, 1948, 1949, 1950, 1951 | 1947,g 1948, 1949, 1950,g 1951 | 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1924 | 28 | 88 | 99 | Transposase | Regulator for MutR familyg and ABC transporter, putative protein kinase, hypothetical proteinf |

| S24 | 1976, 1977, 1978, 1983, 1989 | 1976, 1977, 1978, 1983, 1989 | 1955, 1955, 1960, 1966 | 29 | 70 | 49 | tRNA | Conserved hypothetical proteinsf |

| High GC content | ||||||||

| S25 | 0040, 0041 | 0040, 0041 | 0058, 0059 | 49 | 75 | 67 | Transposase | Purine metabolismf |

| S26 | 0846, 0847, 0848 | 0846, 0847, 0848 | 0885, 0886, 0887 | 43 | 148 | 99.4 | Transposase | Cys/Met metabolismf |

| S27 | 1200, 1201 | 46 | 66 | 46 | Transposase | Histidine synthesis | ||

| S28 | 1680, 1685 | 1685 | 48 | 161 | 83 | Transposase | Putative bacteriocinf | |

Genes in boldface are described in detail in the text.

For S. thermophilus LMG 18311, CNRZ1066, and LMD9, the identifications (IDs) begin with stu, str, and STER_, respectively.

Average GC content for all genes in the gene cluster. The average GC content values of the three S. thermophilus genomes and the two L. bulgaricus genomes are 39.1% and 49.7%, respectively.

The δ value indicates the dissimilarity of the dinucleotide composition between the putative horizontally transferred gene cluster and the complete genome. High δ values can be indicative of horizontal acquisition, but not necessarily in all cases (e.g., not for ribosomal proteins carrying gene clusters). Similarly, low or intermediate δ values do not necessarily suggest the genes are not acquired, since a donor organism can have a similar DNA composition.

The δ values of all genomic fragments were plotted in a frequency distribution. The δ value of the input sequence was then compared with the distribution of the δ values of the genomic fragments. The position of the δ value of the input sequence is indicated by the percentage of fragments with a lower δ value.

The indicated genes of the S. thermophilus strains CNRZ1066 and LMG 18311 genomes have been described by Bolotin et al. and Hols et al. (3, 18) as HGT genes.

The indicated genes have been described by Ibrahim et al. (21) as the positive transcriptional regulators of the Rgg family.

The indicated gene cluster has been studied in detail by Horvath et al. (20).

The three genomes have several putative horizontally transferred gene clusters in common, including clusters S1, S5, S23, S24, S25, and S26. Cluster S1 encodes several lantibiotic/bacteriocin biosynthesis proteins and an exporter, i.e., labB, labC, and labT. These genes in S. thermophilus strains CNRZ1066 and LMG 18311 have been described by Hols et al. (18) as horizontally transferred genes. An ABC-type transporter in cluster S5 (stu0324, str0324, STER_1694) was found to have the best homolog (40% identity) in L. helveticus DPC 4571. Cluster S26 encodes enzymes involved in the metabolism of sulfur-containing amino acids, which will be described in detail below.

We also found examples of strain-specific HGT events such as exopolysaccharide (EPS) biosynthesis genes. According to the distinct groups of polysaccharides defined by Delcour et al. (9), EPSs in this study refer to extracellular polysaccharides which are released into the medium or attached to the cell surface (capsular polysaccharides). EPSs are important for the rheology, texture, and “mouthfeel” of yogurt. In addition, they are believed to contribute to probiotic effects (35). Previous studies revealed that EPS biosynthesis genes can vary enormously in different LAB strains (49). The EPS biosynthesis genes either are obtained by HGT or may have evolved much faster than other genes. The clusters S10, S12, and S13 of S. thermophilus strains LMD9, CNRZ1066 and LMG 18311, respectively, have different gene compositions and contexts and share limited sequence similarities (Table 3), suggesting that their origins differ.

TABLE 3.

Predicted horizontally transferred EPS biosynthesis clustersa

| Gene cluster | Gene ID | Gene alias | Annotationc | GC content (%) | Best BLASTP hit (excluding the same species)d | E valuee |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. thermophilus LMD9 cluster S10 | STER_1057 | Oligosaccharide translocase (flippase) | 30 | Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris Ropy352 (EpsU, GI 125631994) | 0 (98%) | |

| STER_1059 | β-d-Galp β-1,4-galactosyltransferase | 30 | Clostridium beijerinckii NCIMB 8052 (GI 150019442) | 1e−54 (43%) | ||

| STER_1061 | Glycosyltransferase | 32 | Lactobacillus gasseri ATCC 33323 (GI 116629783) | 6e−97 (49%) | ||

| STER_1062 | α-l-Rha α-1,3-l-rhamnosyltransferase | 30 | Streptococcus pneumoniae 2748/40 (GI 68643682) | 2e−40 (34%) | ||

| STER_1066b | β-d-Galp α-1,2-l-rhamnosyltransferase | 30 | Streptococcus infantarius subsp. infantarius ATCC BAA-102 (GI 171779794) | 8e−31 (89%) | ||

| S. thermophilus CNRZ1066 cluster S12 | str1077 | epsL | Polysaccharide pyruvyl transferase | 31 | Bacillus subtilis 168 (GI 50812312) | 1e−44 (37%) |

| str1078 | epsK | Heteropolysaccharide biosynthesis protein | 27 | Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 (GI 213692958) | 1e−31 (30%) | |

| str1079 | epsJ | Secreted polysaccharide polymerase | 31 | L. lactis subsp. lactis KF147 (GI 161702223) | 8e−33 (32%) | |

| str1080 | epsI | α-d-GlcNAc β-1,3-glucosyltransferase | 32 | S. pneumoniae 1936/39 (WcrI, GI 68644162) | 3e−55 (37%) | |

| str1081 | epsH | O-Acetyltransferase | 32 | Bifidobacterium catenulatum DSM 16992 (GI 212716325) | 1e−36 (47%) | |

| str1082 | epsG | β-d-Glcp α-1,3-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase | 30 | S. pneumoniae BZ86 (GI 148767463) | 3e−90 (44%) | |

| S. thermophilus LMG18311 cluster S13 | stu1091 | epsK | β-1,6-N-Acetylglucosaminyltransferase | 30 | Clostridium butyricum 5521 (GI 182416979) | 1e−29 (38%) |

| stu1092 | eps15 | Glycosyltransferase | 32 | L. bulgaricus ATCC 11842 (EpsIM, GI104774657) | 3e−83 (46%) | |

| stu1093 | Glycosyltransferase | 31 | none | N/A | ||

| stu1094 | eps14 | Oligosaccharide translocase (flippase) | 32 | Lactobacillus johnsonii ATCC 11506 (GI 120400357) | 7e−33 (39%) | |

| stu1095 | eps13 | EPS biosynthesis protein, putative | 26 | Clostridium perfringens C strain JGS1495 (GI 169342962) | 1e−12 (25%) | |

| stu1096 | eps12 | Oligosaccharide translocase (flippase) | 29 | Bacillus cereus ATCC 10987 (GI 42784431) | 7e−100 (39%) | |

| stu1097 | eps11 | α-1,2-Frucosyltransferase | 29 | L. lactis subsp. lactis KF147 (GI 161702195) | 2e−33 (30%) | |

| stu1098 | eps10 | Glycosyltransferase | 31 | S. pneumoniae (GI 148996768) | 2e−71 (55%) | |

| stu1099 | eps9 | O-Acetyltransferase | 32 | Vibrio parahaemolyticus AQ3810 (GI 153837517) | 7e−20 (48%) | |

| stu1100 | eps15 | Glycosyltransferase | 32 | S. pneumoniae strain 34356 (WcyK, GI 68642874) | 2e−40 (40%) | |

| L. bulgaricus ATCC 11842 and ATCC BAA365 shared cluster L18 | ldb1940,b LBUL_1803b | epsIIK | Oligosaccharide translocase (flippase) | 40 | Pediococcus pentosaceus ATCC 25745 (GI 116492367) | 7e−12 (46%) |

| ldb1941,b LBUL_1804b | epsIIK | Oligosaccharide translocase (flippase) | 32 | Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae serovar 3 strain JL03 (GI 165976892) | 1e−31 (51%) | |

| ldb1942, LBUL_1805 | epsIIJ | β-1,4-Galactosyltransferase | 36 | Eubacterium siraeum DSM 15702 (GI 167749551) | 2e−08 (32%) | |

| ldb1943, LBUL_1806 | epsIII | α-1,3-Galactosyltransferase | 34 | Lactobacillus reuteri 100-23 (GI 194466827) | 2e−45 (39%) | |

| ldb1944, LBUL_1807 | epsIIH | Glycosyltransferase | 38 | Ruminococcus gnavus ATCC 29149 (GI 154504886) | 8e−49 (35%) | |

| ldb1945, LBUL_1808 | epsIIG | dTDP-rhamnosyl transferase rfbF | 40 | Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM (GI 58337989) | 1e−68 (45%) | |

| L. bulgaricus ATCC BAA365 cluster L19 | LBUL_1841 | Oligosaccharide translocase (flippase) | 30 | L. johnsonii ATCC 11506 (GI 120400357) | 9e−118 (47%) | |

| LBUL_1843 | Glycosyltransferase | 36 | Faecalibacterium prausnitzii M21/2 (GI 160944577) | 3e−44 (36%) | ||

| LBUL_1848 | Glycosyltransferase | 37 | Clostridium sp. strain L2-50 (GI 160893138) | 4e−40 (33%) | ||

| LBUL_1851 | Polysaccharide polymerase | 31 | Oenococcus oeni bacteriophage fOgPSU1 (GI 50057028) | 3e−62 (43%) | ||

| LBUL_1853 | Glycosyltransferase | 32 | L. johnsonii ATCC 33200 (GI 120400332) | 7e−102 (73%) | ||

| L. bulgaricus ATCC 11842 cluster, partially shared with ATCC | ldb1998 | epsIM | α-l-Rha α-1,3-glucosyltransferase | 37 | S. thermophilus LMG 18311 (eps15, stu1092) | 3e−83 (46%) |

| BAA365 L20 | ldb1999,bldb2000b | epsIL | β-1,6-N-Acetylglucosaminyltransferase | 36 | S. thermophilus (Eps3I, GI 24473742) | 6e−42 (49%) |

| ldb2001 | epsIK | Oligosaccharide translocase (flippase) | 40 | L. johnsonii NCC 533 (GI 42518960) | 0 (65%) | |

| ldb2003 | epsII | EPS biosynthesis protein, unknown function | 34 | Clostridium perfringens strain 13 (GI 18309485) | 7e−06 (23%) | |

| ldb2004 | epsIH | α-1,3-Galactosyltransferase | 33 | Clostridium botulinum F strain Langeland (GI 153941359) | 1e−36 (37%) | |

| ldb2005, LBUL_1854 | epsIG | β-d-Glcp β-1,4-galactosyltransferase | 36 | L. gasseri ATCC 33323 (GI 116629786) | 8e−69 (73%) | |

| ldb2006, LBUL_1855 | epsIF | β-1,4-Galactosyltransferase accessory protein | 36 | L. gasseri ATCC 33323 (GI 116629787) | 3e−77 (91%) |

Only the genes related to EPS biosynthesis in the clusters are shown here. Hypothetical proteins and transposases in the clusters are excluded. Genes in boldface represent those that were putatively transferred between yogurt bacteria.

Pseudogene.

Annotations were obtained from the ERGO database (37).

The best BLASTP hits for the target protein against the nonredundant protein database from NCBI. If the best hit was in the same species, the second best was retrieved iteratively until a hit in a different species was found. The gene/protein name and/or GI code for the best BLAST hit are provided in parentheses. The cut-off E value used for determining the existence of the best hits was 1e−5.

The percentage of identity is shown in parentheses.

Cluster S21 of S. thermophilus LMD9 contains STER_1698, encoding a phage resistance protein with a Pfam Abi_2 domain. Homologs of this protein were found to be involved in bacteriophage resistance, mediated through abortive infection in Lactococcus species (2). They belong to the AbiD, AbiD1, or AbiF family of proteins encoded by lactococcal plasmids and are active mainly against bacteriophage groups 936 and C2. The unique presence of this phage resistance gene in strain LMD9 might indicate a strain-dependent antiphage characteristic. Moreover, the genes present in cluster S19 of the same strain encode a novel phage resistance system, CRISPR3 (for clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats), with a low GC content (31%) indicative of a foreign origin. It agrees with the observation of Horvath et al. that CRISPR loci were possibly horizontally transferred and that they may play an important role in adaptation to a specific environment (19, 20).

Putative HGT from foreign origin to L. bulgaricus.

A similar analysis of the genomes of L. bulgaricus strains ATCC 11842 and ATCC BAA365 also revealed several putative HGT events (Table 4; see also Table S1 and Fig. S2 and S3 in the supplemental material). The chromosomal regions with significantly lower GC content could be the result of HGT from either S. thermophilus or other low-GC organisms. The high δ values, showing higher dissimilarity with dinucleotide composition, and the features of the flanking regions related to mobile elements are indicative for the HGT event (Table 4; see also Table S1 in the supplemental material). In total, 149 genes (including pseudogenes) were identified as being putatively horizontally transferred, 120 of which were found to be associated with gene transfer elements. The large majority (130 of the 149 genes) were distributed in 24 gene clusters.

TABLE 4.

Proposed horizontally transferred genes and gene clusters in L. bulgaricus genomesa

| Gene cluster | Gene ID(s) for strainb:

|

GC content (%)c | δ Value (103)d | δ Plot position (%)e | HGT mechanism-associated feature | Function(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATCC 11842 | ATCC BAA365 | ||||||

| L1 | 0014, 0019, 0020 | 0014, 0019 | 39 | 83 | 80 | tRNA | ABC transporter, transcriptional regulator (Xre family) |

| L2 | 0157, 0158 | 0132, 0133, 0134 | 38 | 112 | 87 | Hypothetical proteins | |

| L3 | 0245, 0246, 0247, 0248, 0249, 0251, 0252, 0253, 0254 | 0208, 0209, 0210, 0211, 0213, 0214, 0215, 0216, 0217 | 37 | 86 | 96 | Transposase | Folate biosynthesis proteins,f glutamine transport system, hypothetical proteins |

| L4 | 0260, 0261, 0262, 0263, 0264, 0265, 0266, 0267, 0268, 0269, 0270, 0271 | 0222, 0223, 0224, 0225, 0226, 0227, 0228, 0229 | 37 | 95 | 99 | tRNA | Peptidases, amino acid transporter, methionine biosynthesis genes, hypothetical proteins |

| L5 | 0299, 0301 | 0253, 0255 | 35 | 103 | 92 | Serine/threonine protein kinase (signaling pathway), hypothetical protein | |

| L6 | 0329, 0330, 0332, 0333, 0334 | 0285, 0286, 0288, 0289, 0290 | 35 | 66 | 72 | Transposase, tRNA | ABC transporter, serine/threonine protein kinase, hypothetical proteins |

| L7 | 0430, 0431 | 0384, 0385 | 39 | 59 | 4 | tRNA | Hypothetical proteins |

| L8 | 0959, 0960, 0961, 0962, 0964, 0966 | 33 | 71 | 75 | Phage recombinase | Carboxypeptidase, hypothetical proteins | |

| L9 | 0996, 0997, 0998, 1009, 1010, 1011 | 39 | 145 | 99 | Phage | Phage-associated proteins, hypothetical proteins | |

| L10 | 1042, 1044, 1046, 1047, 1048, 1049 | 33 | 72 | 76 | Carboxypeptidase, hypothetical proteins | ||

| L11 | 1053, 1054, 1055, 1077, 1078 | 38 | 42 | 28 | Phage integrase | Type I restriction-modification system | |

| L12 | 1228, 1229, 1230, 1231, 1232 | 39 | 119 | 100 | Type III restriction-modification system, hypothetical protein | ||

| L13 | 1143, 1144, 1145, 1146, 1147, 1148, 1150, 1151, 1152 | 39 | 81 | 97 | Transposase | Type II and Type I restriction-modification system, hypothetical proteins | |

| L14 | 1394, 1395, 1396 | 37 | 91 | 81 | Transposase | Hypothetical proteins | |

| L15 | 1461, 1462 | 1356, 1357 | 38 | 104 | 92 | Transposase | Cyclopropane fatty acid synthase, peptidase |

| L16 | 1694, 1695, 1696, 1697 | 1569, 1570, 1571, 1572 | 38 | 87 | 86 | tRNA | Glucose-1-phosphate thymidylyltransferase, hypothetical protein |

| L17 | 1775, 1776, 1777, 1778, 1779, 1780, 1781, 1782 | 1645, 1646, 1647, 1648, 1650, 1651, 1652, 1653, 1654, 1655 | 36 | 98 | 99 | Transposase | Urea cycle protein,f amino acid transporter, oxalate/formate antiporter, transposase, type II restriction-modification system, hypothetical proteins |

| L18 | 1940, 1941, 1942, 1943, 1944, 1945 | 1803, 1804, 1805, 1806, 1807, 1808 | 37 | 80 | 90 | Transposase | EPS biosynthesis |

| L19 | 1840, 1841, 1843, 1848, 1851, 1853 | 34 | 113 | 99.7 | Transposase | EPS biosynthesis | |

| L20 | 1985, 1988, 1989, 1990, 1991, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006 | 1854, 1855 | 36 | 83 | 100 | Transposase | EPS biosynthesis, DNA binding protein, transposase, hypothetical proteins |

| L21 | 2094, 2095 | 1938, 1939 | 36 | 70 | 76 | ABC transporter, serine/threonine protein kinase | |

| L22 | 2108, 2109, 2110, 2111, 2112, 2113, 2114, 2117, 2118 | 1950, 1951, 1952, 1953, 1954, 1955, 1957, 1958 | 40 | 95 | 98 | Transposase | Pyrimidine biosynthesis proteins, cold shock protein |

| L23 | 2178, 2179, 2180, 2181 | 38 | 106 | 95 | Transposase | Spermidine/putrescine transporterf | |

| L24 | 2192, 2193, 2194 | 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 | 37 | 75 | 62 | Transposase | Peptidoglycan-binding protein, hypothetical proteins |

Genes in boldface are described in detail in the text.

For L. bulgaricus ATCC 11842 and ATCC BAA365, the IDs begin with ldb and LBUL_, respectively.

Average GC content for all genes in the gene cluster. The average GC content values of the three S. thermophilus genomes and the two L. bulgaricus genomes are 39.1% and 49.7%, respectively.

The δ value indicates the dissimilarity of the dinucleotide composition between the putative horizontally transferred gene cluster and the complete genome. High δ values can be indicative of horizontal acquisition, but not necessarily in all cases (e.g., not for ribosomal proteins carrying gene clusters). Similarly, low or intermediate δ values do not necessarily suggest the genes are not acquired, since a donor organism can have a similar DNA composition.

The δ values of all genomic fragments were plotted in a frequency distribution. The δ value of the input sequence was then compared with the distribution of the δ values of the genomic fragments. The position of the δ value of the input sequence is indicated by the percentage of fragments with a lower δ value.

The indicated genes of the L. bulgaricus ATCC 11842 genome have been described by van de Guchte et al. (46) as HGT genes.

Among the predicted HGT events in L. bulgaricus, genes encoding transporter systems, restriction-modification systems, and EPS biosynthesis clusters are highly represented (Table 4). Genes present in the EPS biosynthesis clusters L18, L19, and L20 (Table 3) have low-GC content values (from 34% to 37%) and relatively high δ values (between 0.08 and 0.11), which are higher than those of about 90% of the genome fragments. This indicates that most EPS biosynthesis genes in L. bulgaricus are possibly derived from phylogenetically unrelated low-GC organisms.

Of the predicted horizontally transferred gene clusters, 15 out of 24 are found in both L. bulgaricus genomes (Table 4). For example, cluster L6, harboring genes encoding an ABC-type transporter, has the best blast hit with Streptococcus pneumoniae TIGR4. Another example is the folate biosynthesis operon folB-folKE-folC-folP (cluster L3) which has been described previously by van de Guchte et al. (46). L. bulgaricus strains are not able to produce folate, one of the essential components in human diets (45). This could be due to the absence of the genes involved in the biosynthesis of p-aminobenzoic acid (PABA), a precursor of folate. The PABA biosynthesis genes are present in the genomes of S. thermophilus. During the cogrowth of the two organisms, the S. thermophilus cells may provide PABA to the L. bulgaricus cells, thereby enabling them to produce folate (43, 46). A glutamine transporter system (LBUL_0214-0217 or ldb0251-0254) present in the same cluster, L3, could also be acquired by HGT. All the putative horizontally transferred genes indicate that the region harboring gene cluster L3 could be an active region, with respect to genomic recombination. The ISL5-like (29) transposase gene (LBUL_0221) in this region provides additional suggestions for the predicted HGT events.

Another interesting finding is the identification of three eukaryotic-type serine/threonine protein kinase genes (ldb0301, ldb0334, and ldb2095 or LBUL_0255, LBUL_0290, and LBUL_1939) in gene clusters L5, L6, and L21, respectively. Their protein sequences share about 30% identity with S. thermophilus homologs. Notably, BLAST analysis found the homologs of these genes present only in the genomes of S. thermophilus, L. bulgaricus, and one Lactococcus strain but absent in the other sequenced LAB genomes. The nucleotide sequence compositions of these protein kinase genes were not very similar to those of the S. thermophilus or L. bulgaricus genomes, suggesting a putative horizontal transfer event between the kinase genes from a foreign origin to S. thermophilus and L. bulgaricus genomes. Serine/threonine protein kinases are commonly found in eukaryotes, and they have been reported to play a role in the bacterial growth and development in many bacterial species (28, 51). The function of the serine/threonine protein kinases in L. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus remains to be discovered.

HGT between Lactobacillus bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus: cbs-cblB(cglB)-cysE as an example.

In addition to the HGT events in L. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus genomes from foreign origins, we also identified putative HGT events between the L. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus genomes. The EPS biosynthesis genes epsIM and epsIL (ldb1998-2000) in cluster L20 of L. bulgaricus were possibly acquired from S. thermophilus, since they share high sequence homology with the eps15 gene (stu1092) of S. thermophilus LMG 18311 and eps3I of another S. thermophilus strain, with 46% and 49% identity at the amino acid level, respectively (Table 3). epsIL (ldb1999-2000) is truncated due to an in-frame stop codon. A phylogenetic analysis using the homologs of epsIM and epsIL supported the hypothesis that the genes were transferred from S. thermophilus to L. bulgaricus (data not shown). The transfer of EPS biosynthesis genes between S. thermophilus and L. bulgaricus could play a role in (the optimization of) the physical interaction between the species in mixed yogurt cultures and, thus, in the exchange of metabolites and/or stimulatory factors. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that EPS production is also influenced by the cocultivation of the two species (S. Sieuwerts, C. Ingham, and J. van Hylckama Vlieg, personal communication). For kefir, similar findings have been obtained for Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (5). The physical contact between the two species enhanced the capsular kefiran production of L. kefiranofaciens.

Another example of an HGT event between S. thermophilus and L. bulgaricus is the cbs-cblB(cglB)-cysE gene cluster encoding enzymes involved in sulfur-containing amino acid metabolism. The gene cluster was originally named cysM2-metB2-cysE2 (3) but was renamed in our previous study of the basis of a consistent functional annotation in LAB (31). Since this HGT event could give insight into the coevolution in milk and protocooperation between the two bacterial species during yogurt fermentation, we performed an in-depth comparative analysis on the evolution of this gene cluster, in light of phylogeny, gene context, and sequence features.

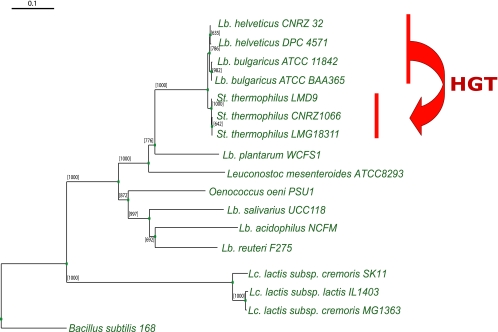

The cbs-cblB(cglB)-cysE gene cluster is located in a 3.6-kb region (including a 600-bp upstream noncoding region) in S. thermophilus cluster S26. The corresponding genes in L. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus share more than 94% nucleotide sequence identity. Using the δρ-Web tool, we analyzed the sequence similarity between this DNA fragment and the whole genomes of S. thermophilus, respectively: the cbs-cblB(cglB)-cysE fragment has a very high δ value compared to the value for rest of the genome, indicating lower sequence composition similarity between the DNA fragment and the S. thermophilus genomes. The δ values of the cbs-cblB(cglB)-cysE cluster against the S. thermophilus genomes are much higher than their δ values against the L. bulgaricus genomes. Moreover, phylogenetic analysis also supported the prediction of this HGT event and provided more insight into the evolutionary events leading to the transfer of this cluster (Fig. 1). The cbs-cblB(cglB) gene clusters of S. thermophilus are closely linked to those of L. bulgaricus and L. helveticus (lactobacillus branch) instead of L. lactis in the classic phylogenetic tree, suggesting an HGT event from L. bulgaricus or L. helveticus to S. thermophilus. Although the sequence composition of this gene cluster is more similar to that of the L. bulgaricus genomes than to that of the L. helveticus genome (lower δ values and more-similar GC content), the difference is not significant enough to conclude that the cluster originates from L. bulgaricus.

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic tree of the cbs-cblB(cglB)-cysE gene cluster in LAB genomes. The tree is constructed on the basis of the alignment of concatenated sequences of the cbs and cblB or cglB genes. Since the gene cysE is a pseudogene in a few genomes, it is not taken into account in the phylogenetic analysis. Bootstrap values are reported for a total of 1,000 replicates. Truncated cbs and cblB or cglB genes from Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM are also included in the tree. Genes from Bacillus subtilis 168 are used as the outgroup. The HGT event is indicated by an arrow. Lb., Lactobacillus; St., Streptococcus; Lc., Lactococcus.

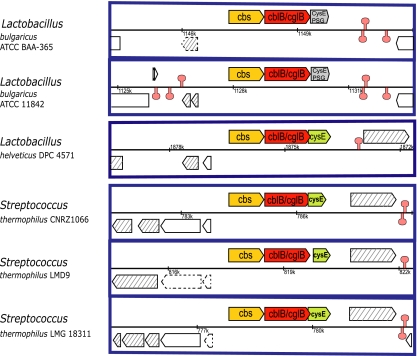

Gene context analysis indicates that L. bulgaricus, L. helveticus, and S. thermophilus have the same gene organization in this region (Fig. 2). Moreover, the locus is flanked by transposase genes, supporting recombination events to occur in this region. Multiple DNA sequence alignment of the cbs-cblB (cglB)-cysE cluster revealed a 179-bp DNA fragment with low GC content (34%) inserted into the open reading frame of the cysE gene in the L. bulgaricus genomes (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). This sequence is responsible for the truncation of the cysE gene in L. bulgaricus. An inverted repeat and a direct repeat are found in close proximity to the boundaries of the insertion sequence (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). The 179-bp DNA sequence shares 98% identity with a transposase gene located in the vicinity of an EPS biosynthesis cluster in L. bulgaricus ATCC BAA365 (cluster L18). We found that this insertion element frequently occurs in nonfunctional genes (pseudogenes) of L. bulgaricus genomes (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). For instance, in L. bulgaricus ATCC BAA365, it was found to be responsible for the truncation of the sucrose-6-phosphate hydrolase gene, a gene important for sucrose metabolism (22).

FIG. 2.

Gene context of cbs-cblB(cglB)-cysE in L. bulgaricus, L. helveticus, and S. thermophilus. The clusters have the same gene context, while cysE in L. bulgaricus strains is truncated due to the presence of an insertion sequence (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). PSG, pseudogene. Dashed arrows also represent the pseudogenes. Predicted terminators are indicated by mushroom symbols. Transposase genes are shadowed by gray diagonal stripes. Modified from an image created with the Microbial Genome Viewer application (26).

The cbs-cblB(cglB)-cysE cluster in L. helveticus shares over 90% nucleotide sequence identity to the counterparts in L. bulgaricus. Interestingly, the cysE gene in L. helveticus is intact. This suggests that S. thermophilus could have acquired this gene cluster from L. helveticus. Both species are used in conjunction in the manufacture of Bulgarian-type yogurt (11).

Role of the horizontally transferred cbs-cblB(cglB)-cysE cluster in protocooperation.

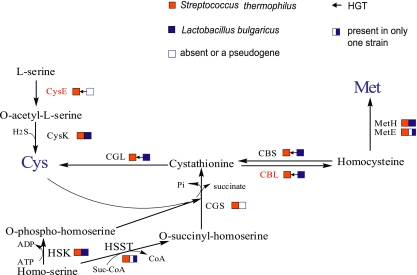

The enzymes encoded by the cbs-cblB(cglB)-cysE gene cluster are involved in the metabolism of sulfur-containing amino acids. The metabolic pathway of the interconversion between cysteine and methionine containing these enzymes is shown in Fig. 3. Serine acetyltransferase, encoded by cysE, initiates cysteine biosynthesis by converting l-serine to O-acetylserine. The enzymes encoded by cblB or cglB and cbs are involved in the conversion of homocysteine to cysteine. As indicated, CysE, CblB/CglB, and CBS in S. thermophilus are probably obtained by HGT from L. bulgaricus, while the cysE gene is truncated in L. bulgaricus. It should be noted that another copy of the cysE and cbl or cgl genes [in addition to those in the cbs-cblB(cglB)-cysE operon] is present in the S. thermophilus genomes.

FIG. 3.

Methionine and cysteine interconversion pathway in S. thermophilus and L. bulgaricus. Filled red boxes represent the presence of the genes in the three S. thermophilus strains. Filled blue boxes represent the presence of the genes in both L. bulgaricus strains. The half-filled blue box represents a gene present only in L. bulgaricus ATCC BAA365. Open boxes indicate that the genes either are absent or are pseudogenes. Arrows between boxes represent the HGT events and the directions of the transfers. The cysE gene in L. bulgaricus is truncated after the HGT; thus, it is also shown as an open box. The enzymes shown are as follows: CysE, serine acetyltransferase; CysK, O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase; CBL, cystathionine beta-lyase; CGL, cystathionine gamma-lyase; MetH, homocysteine S-methyltransferase; MetE, homocysteine methyltransferase; HSK, homoserine kinase; HSST, homoserine O-succinyltransferase; CGS, cystathionine gamma-synthase; CBS, cystathionine beta-synthase. The distribution of the above-mentioned genes in the S. thermophilus and L. bulgaricus genomes is derived from our previous study (31). Suc-CoA, succinyl coenzyme A; Pi, phosphate.

The sulfur-containing amino acids cysteine and methionine are present in low concentrations in milk proteins, 0.89% and 2.4%, respectively (42). In milk, only traces of methionine and cysteine can be detected as free amino acids (14). As the amount of sulfur-containing amino acids in milk either as free amino acids or derived from proteolysis may not meet the requirements for bacterial growth, bacteria need to synthesize these amino acids de novo. S. thermophilus strains are already equipped with most genes required for methionine and cysteine biosynthesis. However, under the evolutionary pressure, S. thermophilus might need to produce more cysteine/methionine, and a “foreign” gene cluster could probably have added value, for instance, when under the control of an alternative regulatory mechanism. In Streptococcus strains, it was found that the promoter region of cysK, the cbs paralog, has a conserved motif for binding to the transcriptional regulator CmbR (27). This activator regulates the metC-cysK operon encoding a cystathionine lyase and cysteine synthase in Lactococcus lactis (15). This regulatory motif is not found upstream of the cbs-cblB(cglB)-cysE gene cluster. However, we did find a GC-rich motif to be conserved in the upstream region of the cbs gene in the S. thermophilus and L. bulgaricus genomes, as well as in the Lactobacillus plantarum, Oenococcus, and Leuconostoc genomes, which may be a binding site for an alternative transcriptional regulator (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). After transferring the intact gene cluster to S. thermophilus, the L. bulgaricus strains may have inactivated their cysE genes, thereby losing the ability to synthesize cysteine. In contrast to S. thermophilus, L. bulgaricus lacks an active serine biosynthesis pathway; it is unnecessary to maintain a functional gene involved in this pathway for synthesizing cysteine from serine.

A recent proteomics study of S. thermophilus LMG 18311 revealed the upregulation of sulfur-containing amino acid biosynthesis genes, including cbs (cysM2) and cblB or cglB (metB2), when grown in coculture with L. bulgaricus ATCC 11842 (16). The stimulatory effect of L. bulgaricus on this biosynthetic pathway in S. thermophilus suggests that the enzymes are indeed of importance for protocooperation in yogurt manufacturing.

Conclusions.

The protocooperation between L. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus in yogurt manufacturing has been previously described but with respect mainly to their dependency on growth factors and metabolic interactions. In this study, we identified HGT events between the yogurt bacteria and revealed protocooperation on the basis of exchanged and/or acquired genetic elements during evolution. The genome-wide analysis generated a list of genes and gene clusters, most probably obtained by HGT. The EPS biosynthesis proteins EPSIM and EPSIL in L. bulgaricus genomes were likely acquired from S. thermophilus. A gene cluster encoding the enzymes involved in sulfur-containing amino acid metabolism [cbs-cblB(cglB)-cysE] in S. thermophilus was probably transferred from L. bulgaricus strains. The predicted HGT events in bacteria used in yogurt manufacturing, S. thermophilus and L. bulgaricus, provide important information on their coevolution and their protocooperation strategies for adaptation to the milk environment. The new insights could be used advantageously to improve the control of cogrowth of both species in yogurt manufacturing and, accordingly, to improve product characteristics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant CSI4017 from the Casimir program of the Ministry of Economic Affairs, The Netherlands.

We thank Ellen Looijesteijn for critically reading the manuscript and Celine Prakash for the analysis of the conserved regulatory motifs.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 24 April 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anba, J., E. Bidnenko, A. Hillier, D. Ehrlich, and M. C. Chopin. 1995. Characterization of the lactococcal abiD1 gene coding for phage abortive infection. J. Bacteriol. 177:3818-3823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolotin, A., B. Quinquis, P. Renault, A. Sorokin, S. D. Ehrlich, S. Kulakauskas, A. Lapidus, E. Goltsman, M. Mazur, G. D. Pusch, M. Fonstein, R. Overbeek, N. Kyprides, B. Purnelle, D. Prozzi, K. Ngui, D. Masuy, F. Hancy, S. Burteau, M. Boutry, J. Delcour, A. Goffeau, and P. Hols. 2004. Complete sequence and comparative genome analysis of the dairy bacterium Streptococcus thermophilus. Nat. Biotechnol. 22:1554-1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Callanan, M., P. Kaleta, J. O'Callaghan, O. O'Sullivan, K. Jordan, O. McAuliffe, A. Sangrador-Vegas, L. Slattery, G. F. Fitzgerald, T. Beresford, and R. P. Ross. 2008. Genome sequence of Lactobacillus helveticus, an organism distinguished by selective gene loss and insertion sequence element expansion. J. Bacteriol. 190:727-735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheirsilp, B., H. Shoji, H. Shimizu, and S. Shioya. 2003. Interactions between Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens and Saccharomyces cerevisiae in mixed culture for kefiran production. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 96:279-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Courtin, P., V. Monnet, and F. Rul. 2002. Cell-wall proteinases PrtS and PrtB have a different role in Streptococcus thermophilus/Lactobacillus bulgaricus mixed cultures in milk. Microbiology 148:3413-3421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Courtin, P., and F. Rul. 2004. Interactions between microorganisms in a simple ecosystem: yogurt bacteria as a study model. Lait 84:125-134. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darling, A. C., B. Mau, F. R. Blattner, and N. T. Perna. 2004. Mauve: multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res. 14:1394-1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delcour, J., T. Ferain, M. Deghorain, E. Palumbo, and P. Hols. 1999. The biosynthesis and functionality of the cell-wall of lactic acid bacteria. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 76:159-184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delorme, C. 2008. Safety assessment of dairy microorganisms: Streptococcus thermophilus. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 126:274-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dimitrov, Z., M. Michaylova, and S. Mincova. 2005. Characterization of Lactobacillus helveticus strains isolated from Bulgarian yoghurt, cheese, plants and human faecal samples by sodium dodecilsulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of cell-wall proteins, ribotyping and pulsed field gel fingerprinting. Int. Dairy J. 15:998-1005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edgar, R. C. 2004. MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinformatics 5:113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feder, M. E. 2007. Evolvability of physiological and biochemical traits: evolutionary mechanisms including and beyond single-nucleotide mutation. J. Exp. Biol. 210:1653-1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghadimi, H., and P. Pecora. 1963. Free amino acids of different kinds of milk. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 13:75-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Golic, N., M. Schliekelmann, M. Fernandez, M. Kleerebezem, and R. van Kranenburg. 2005. Molecular characterization of the CmbR activator-binding site in the metC-cysK promoter region in Lactococcus lactis. Microbiology 151:439-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herve-Jimenez, L., I. Guillouard, E. Guedon, C. Gautier, S. Boudebbouze, P. Hols, V. Monnet, F. Rul, and E. Maguin. 2008. Physiology of Streptococcus thermophilus during the late stage of milk fermentation with special regard to sulfur amino-acid metabolism. Proteomics 8:4273-4286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffmeister, M., and W. Martin. 2003. Interspecific evolution: microbial symbiosis, endosymbiosis and gene transfer. Environ. Microbiol. 5:641-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hols, P., F. Hancy, L. Fontaine, B. Grossiord, D. Prozzi, N. Leblond-Bourget, B. Decaris, A. Bolotin, C. Delorme, S. Dusko Ehrlich, E. Guedon, V. Monnet, P. Renault, and M. Kleerebezem. 2005. New insights in the molecular biology and physiology of Streptococcus thermophilus revealed by comparative genomics. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 29:435-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horvath, P., A. C. Coute-Monvoisin, D. A. Romero, P. Boyaval, C. Fremaux, and R. Barrangou. 15 July 2008. Comparative analysis of CRISPR loci in lactic acid bacteria genomes. Int. J. Food Microbiol. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Horvath, P., D. A. Romero, A. C. Coute-Monvoisin, M. Richards, H. Deveau, S. Moineau, P. Boyaval, C. Fremaux, and R. Barrangou. 2008. Diversity, activity, and evolution of CRISPR loci in Streptococcus thermophilus. J. Bacteriol. 190:1401-1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ibrahim, M., P. Nicolas, P. Bessieres, A. Bolotin, V. Monnet, and R. Gardan. 2007. A genome-wide survey of short coding sequences in streptococci. Microbiology 153:3631-3644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iyer, R., and A. Camilli. 2007. Sucrose metabolism contributes to in vivo fitness of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 66:1-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jain, R., M. C. Rivera, J. E. Moore, and J. A. Lake. 2002. Horizontal gene transfer in microbial genome evolution. Theor. Popul. Biol. 61:489-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karlin, S. 2001. Detecting anomalous gene clusters and pathogenicity islands in diverse bacterial genomes. Trends Microbiol. 9:335-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karlin, S., I. Ladunga, and B. E. Blaisdell. 1994. Heterogeneity of genomes: measures and values. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:12837-12841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kerkhoven, R., F. H. van Enckevort, J. Boekhorst, D. Molenaar, and R. J. Siezen. 2004. Visualization for genomics: the Microbial Genome Viewer. Bioinformatics 20:1812-1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kovaleva, G. Y., and M. S. Gelfand. 2007. Transcriptional regulation of the methionine and cysteine transport and metabolism in streptococci. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 276:207-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krupa, A., and N. Srinivasan. 2005. Diversity in domain architectures of Ser/Thr kinases and their homologues in prokaryotes. BMC Genomics 6:129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lapierre, L., B. Mollet, and J. E. Germond. 2002. Regulation and adaptive evolution of lactose operon expression in Lactobacillus delbrueckii. J. Bacteriol. 184:928-935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Larkin, M., G. Blackshields, N. P. Brown, R. Chenna, P. A. McGettigan, H. McWill, F. Valentin, I. M. Wallace, A. Wilm, R. Lopez, J. D. Tompson, T. J. Gibson, and D. G. Higgins. 2007. ClustalW and ClustalX version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23:2947-2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu, M., A. Nauta, C. Francke, and R. J. Siezen. 2008. Comparative genomics of enzymes in flavor-forming pathways from amino acids in lactic acid bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:4590-4600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu, M., F. H. van Enckevort, and R. J. Siezen. 2005. Genome update: lactic acid bacteria genome sequencing is booming. Microbiology 151:3811-3814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Makarova, K., A. Slesarev, Y. Wolf, A. Sorokin, B. Mirkin, E. Koonin, A. Pavlov, N. Pavlova, V. Karamychev, N. Polouchine, V. Shakhova, I. Grigoriev, Y. Lou, D. Rohksar, S. Lucas, K. Huang, D. M. Goodstein, T. Hawkins, V. Plengvidhya, D. Welker, J. Hughes, Y. Goh, A. Benson, K. Baldwin, J. H. Lee, I. Diaz-Muniz, B. Dosti, V. Smeianov, W. Wechter, R. Barabote, G. Lorca, E. Altermann, R. Barrangou, B. Ganesan, Y. Xie, H. Rawsthorne, D. Tamir, C. Parker, F. Breidt, J. Broadbent, R. Hutkins, D. O'Sullivan, J. Steele, G. Unlu, M. Saier, T. Klaenhammer, P. Richardson, S. Kozyavkin, B. Weimer, and D. Mills. 2006. Comparative genomics of the lactic acid bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:15611-15616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Makarova, K. S., and E. V. Koonin. 2007. Evolutionary genomics of lactic acid bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 189:1199-1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Makino, S., S. Ikegami, H. Kano, T. Sashihara, H. Sugano, H. Horiuchi, T. Saito, and M. Oda. 2006. Immunomodulatory effects of polysaccharides produced by Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus OLL1073R-1. J. Dairy Sci. 89:2873-2881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nicolas, P., P. Bessieres, S. D. Ehrlich, E. Maguin, and M. van de Guchte. 2007. Extensive horizontal transfer of core genome genes between two Lactobacillus species found in the gastrointestinal tract. BMC Evol. Biol. 7:141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Overbeek, R., N. Larsen, T. Walunas, M. D'Souza, G. Pusch, E. Selkov, K. Liolios, V. Joukov, D. Kaznadzey, I. Anderson, A. Bhattacharyya, H. Burd, W. Gardner, P. Hanke, V. Kapatral, N. Mikhailova, O. Vasieva, A. Osterman, V. Vonstein, M. Fonstein, N. Ivanova, and N. Kyrpides. 2003. The ERGO (TM) genome analysis and discovery system. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:164-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pette, J. W., and H. Lolkema. 1950. Yoghurt. I. Symbiosis and antibiosis of mixed cultures of Lactobacillus bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus. Neth. Milk Dairy J. 4:197-208. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pfeiler, E. A., and T. R. Klaenhammer. 2007. The genomics of lactic acid bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 15:546-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rasmussen, T. B., M. Danielsen, O. Valina, C. Garrigues, E. Johansen, and M. B. Pedersen. 2008. Streptococcus thermophilus core genome: comparative genome hybridization study of 47 strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:4703-4710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rutherford, K., J. Parkhill, J. Crook, T. Horsnell, P. Rice, M. A. Rajandream, and B. Barrell. 2000. Artemis: sequence visualization and annotation. Bioinformatics 16:944-945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rutherfurd, S. M., and P. J. Moughan. 1998. The digestible amino acid composition of several milk proteins: application of a new bioassay. J. Dairy Sci. 81:909-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sieuwerts, S., F. A. de Bok, J. Hugenholtz, and J. E. van Hylckama Vlieg. 2008. Unraveling microbial interactions in food fermentations: from classical to genomics approaches. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:4997-5007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Siezen, R. J., and H. Bachmann. 2008. Genomics of dairy fermentations. Microb. Biotechnol. 1:435-442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sybesma, W., M. Starrenburg, L. Tijsseling, M. H. Hoefnagel, and J. Hugenholtz. 2003. Effects of cultivation conditions on folate production by lactic acid bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:4542-4548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van de Guchte, M., S. Penaud, C. Grimaldi, V. Barbe, K. Bryson, P. Nicolas, C. Robert, S. Oztas, S. Mangenot, A. Couloux, V. Loux, R. Dervyn, R. Bossy, A. Bolotin, J. M. Batto, T. Walunas, J. F. Gibrat, P. Bessieres, J. Weissenbach, S. D. Ehrlich, and E. Maguin. 2006. The complete genome sequence of Lactobacillus bulgaricus reveals extensive and ongoing reductive evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:9274-9279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van der Heijden, R. T., B. Snel, V. van Noort, and M. A. Huynen. 2007. Orthology prediction at scalable resolution by phylogenetic tree analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 8:83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van Passel, M. W., A. C. Luyf, A. H. van Kampen, A. Bart, and A. van der Ende. 2005. Deltarho-web, an online tool to assess composition similarity of individual nucleic acid sequences. Bioinformatics 21:3053-3055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Welman, A. D., and I. S. Maddox. 2003. Exopolysaccharides from lactic acid bacteria: perspectives and challenges. Trends Biotechnol. 21:269-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zaneveld, J. R., D. R. Nemergut, and R. Knight. 2008. Are all horizontal gene transfers created equal? Prospects for mechanism-based studies of HGT patterns. Microbiology 154:1-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang, C. C. 1996. Bacterial signalling involving eukaryotic-type protein kinases. Mol. Microbiol. 20:9-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.