Abstract

Photorhabdus luminescens subsp. akhurstii LN2 from Heterorhabditis indica LN2 showed nematicidal activity against axenic Heterorhabditis bacteriophora H06 infective juveniles (IJs). Transposon mutagenesis identified an LN2 mutant that supports the growth of H06 nematodes. Tn5 disrupted the namA gene, encoding a novel 364-residue protein and involving the nematicidal activity. The green fluorescent protein-labeled namA mutant was unable to colonize the intestines of H06 IJs.

Entomopathogenic Heterorhabditis and Steinernema nematodes are safe and effective bioinsecticides for the biological control of many economically important pests (9). The infective juveniles (IJs) of these nematodes harbor Photorhabdus or Xenorhabdus bacteria as symbionts in their intestines. The IJ nematodes properly maintain and carry the bacteria needed for killing insects and providing a suitable environment for the reproduction of new vectors (5, 8). Different bacterial isolates differ in their ability to support in vitro monoxenic cultures of nonhost nematodes (2, 7, 13) and to retain the bacterial cells in the IJ intestines (2, 8, 11).

Strains of Photorhabdus and Xenorhabdus spp. not only show insecticidal activities toward different insects (3, 4, 21) but also exhibit nematicidal activities against nematodes (14, 16, 17). The trans-specific nematicidal activity of Photorhabdus luminescens subsp. akhurstii LN2, a normal symbiont of Heterorhabditis indica LN2 against Heterorhabditis bacteriophora H06, was previously observed (12). The LN2 bacteria may secrete unidentified toxic factors that are lethal to the H06 nematodes. However, the genes of these bacteria involved in the trans-specific nematicidal activities have not been reported.

This paper describes the identification, through Tn5 mutagenesis and characterization, of a novel P. luminescens LN2 gene involved in nematicidal activity against the H06 IJs. The colonization of the green fluorescent protein (GFP)-labeled mutant cells in H06 IJ intestines was examined.

Isolation of a toxin-defective mutant.

Suicide plasmid pRL1063a carrying the Kmr transposon Tn5 and luxAB reporter genes (19) was introduced into a spontaneous ampicillin-resistant mutant of P. luminescens LN2, with the helper plasmid pRK2013, by triparental mating (20). The mutant colonies were screened for their nematicidal activities against axenic H06 IJs (10). From a transposon library of over 5,000 colonies, one mutant (named namA), which is able to support the growth of H06 nematodes, was obtained. The nematodes survived, and hermaphrodites with eggs inside were observed after 7 days with living mutant bacteria. Hermaphrodites with living juveniles inside and outside were observed after 12 days. With other mutants or the wild-type bacteria, all the nematodes died after 7 days, although 50 to 80% of the IJs might recover during the incubation. The namA mutant also lacked toxicity to other strains (HP88 and V16) of H. bacteriophora.

Southern blot analysis of the EcoRI-digested genomic DNA of the Tn5-luxAB insertion mutant, probed with the fragment of the luxAB gene within Tn5, showed a single insertion for Tn5-luxAB in the chromosome of P. luminescens LN2.

Identification of a novel gene.

DNA sequencing identified a 1,095-bp open reading frame (ORF) flanked by the insert site of the transposon. This ORF, designated namA, encodes a 364-residue protein (Fig. 1) with a predicted molecular mass (42,660 Da). The predicted protein is 46% identical to a hypothetical protein in the gram-negative bacterium Vibrio cholerae (E value = 3e−93). The similarity of the domains of the predicted NamA protein and the hypothetical protein from V. cholerae was below 52%. Detailed analysis of the amino acid sequence with similarity searches and motif and fold recognition showed no significant matches. Thus, it appeared that the gene had no significant homologs in the current databases and, therefore, was a novel gene involved in the nematicidal activity of LN2 bacteria.

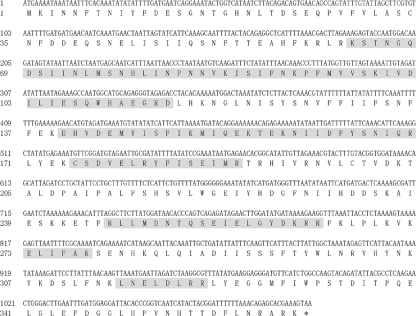

FIG. 1.

DNA sequence of the namA gene from P. luminescens LN2, with the amino acid sequence of the ORF shown below the DNA sequence. Shaded amino acids belong to peptides identified by mass spectroscopy on a tryptic digest of NamA.

The 9,586-bp sequence flanking the Tn5-luxAB was analyzed, and six ORFs were shown (Fig. 2). ORF1, ORF2, ORF3, ORF5, and ORF6 are similar to the genes dam, repA, dcm, gpQ, and gpP, respectively, while ORF4 was designated namA (Table 1). The sequences of all these putative genes were amplified from the genome DNA of the wild-type LN2 and confirmed by sequencing.

FIG. 2.

Physical map of the 9,586-bp Tn5-luxAB flanking sequence, showing six ORFs. ORF1, ORF2, ORF3, ORF4, ORF5, and ORF6 are 771, 2,139, 1,110, 1,095, 1,035 and 1,758 bp in length, respectively. The insert site of the Tn5-luxAB transposon of the namA mutant is located within ORF4 (position 5158).

TABLE 1.

Homologies of ORFs from the Tn5-luxAB flanking sequence

| ORF | Length (bp) | Protein size (no. of amino acids) | Homology(ies) | BLASTX % identity | BLASTX E value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORF1 | 771 | 256 | Putative DNA adenine methylase (dam gene) of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis IP 32953 | 49 | 4e−58 |

| ORF2 | 2,139 | 712 | Replication gene A (repA gene) of Y. pseudotuberculosis PB1 and deoxycytidine deaminase from Yersinia bercovieri ATCC 43970 | 62 | 0.0 |

| ORF3 | 1,110 | 369 | DNA-cytosine methyltransferase (dcm gene) of “Haemophilus somnus” 129PT | 51 | 1e−94 |

| ORF4 | 1,095 | 364 | Hypothetical protein from Vibrio cholerae | 46 | 3e−93 |

| ORF5 | 1,035 | 344 | Portal vertex-like protein (gpQ gene) from Salmonella enterica serotype Javiana strain GA_MM04042433 | 68 | 2e−143 |

| ORF6 | 1,758 | 585 | Probable terminase subunit (gpP gene) from S. enterica serotype Javiana strain GA_MM04042433 | 78 | 0.0 |

Although the genome sequences of P. luminescens subsp. laumondii TT01 are available (GenBank accession number NC005126) (6), the namA gene and the putative genes near namA were not detected in TT01. Attempts to find the namA gene in 13 bacterial isolates of Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus spp. by PCR and Southern blotting were not successful (our unpublished data). It appeared either that this gene is specific in P. luminescens LN2 or that its sequence is very variable in other bacterial isolates. The transcription of the namA gene in the wild-type LN2 strain was detected by reverse transcription-PCR in cultures after 12 to 48 h. From these results, it might be expected that H06 nematodes would be killed by P. luminescens LN2 mediated by the NamA protein, if both nematode species were to coinfect an insect host.

Complementation assays.

To verify that the transposon-disrupted gene is responsible for the loss of nematicidal activity, the namA mutant was transformed with the pLAFR3 plasmid (18) carrying the specific P. luminescens LN2 wild-type namA gene. The gene was amplified with a PstI restriction site, digested with PstI, and cloned into the cosmid pLAFR3 plasmid (18). The resulting construct was transformed into the LN2 mutant by conjugation. The vector without the insertion of the namA gene was introduced into the LN2 mutant as a control. The resulting colonies (Kmr Apr Tcr) were selected for their nematicidal activities against H06 IJs.

The plasmid carrying the gene clearly restored the nematicidal activity of the LN2 mutant against H06 IJs, although not to the level of the wild-type strain. The H06 IJs died after 7 days of incubation with wild-type LN2 bacteria and after 10 days with the namA mutant complemented with the namA gene.

Colonial characterization of the mutant.

The wild-type strain and the namA mutant showed all the characteristics of phase I bacteria (1), except for the production of no pH-sensitive pigments from the namA mutant. API systems detected no different biochemical reactions between the two colonies. Clearly, namA mutant cells were not converted into phase II variants. A previous report indicated that nematicidal activity occurs only in phase I of P. luminescens LN2, and phase II cells partially lose this ability (11). It seemed that the loss of nematicidal activity for the LN2 mutant against H06 nematodes was not the result of a typical phase variation.

Colonization of H06 IJs by nematicidal activity-defective mutant.

To observe the IJ colonization by the mutant bacteria, a spontaneous rifampin-resistant namA mutant (Rifr namA mutant) was labeled with GFP using the pMini-Tn5 transposon containing an egfp gene (15).

The IJs of H. bacteriophora H06 were cultured on sponge medium (10) inoculated with namA or GFP-labeled Rifr namA mutants. The IJ nematodes were extracted from the sponge and observed for GFP-labeled bacteria. The IJs were also homogenized with a sterile glass homogenizer after surface sterilization (10) to check for the presence of the GFP-labeled bacteria in the IJ intestines.

No H06 IJs had GFP-labeled bacteria in their intestines. In addition, no GFP-labeled bacteria were observed in the IJs that were disrupted mechanically. Bacterial colonization of the intestines of the IJs is an important process in the nematode-bacterium symbiosis. The present study demonstrated that the insertion inactivation of the namA gene restored the nutrient suitability of the LN2 bacteria for the reproduction of H06 nematodes by silencing the nematicidal activity of the bacteria but did not establish the environment needed for bacterial colonization of the IJs.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The DNA sequence for the 1,095-bp ORF designated namA has been deposited in GenBank (accession number EU850396).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Natural Foundation of Guangdong (grant 2007-6-7003403). The fellowship to Richou Han by JSPS, Japan, is gratefully appreciated.

The screening experiments of the transposon library were conducted at Saga University, Japan, and all other experiments were conducted in the Guangdong Entomological Institute, China. We thank Jerald Ensign from the University of Wisconsin for critical revision of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 17 April 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akhurst, R. J. 1980. Morphological and functional dimorphism in Xenorhabdus spp., bacteria symbiotically associated with the insect pathogenic nematodes Neoaplectana and Heterorhabditis. J. Gen. Microbiol. 121:303-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akhurst, R. J. 1983. Neoaplectana species: specificity of association with bacteria of the genus Xenorhabdus. Exp. Parasitol. 55:258-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowen, D., T. A. Rocheleau, M. Blackburn, O. Andreev, E. Golubeva, R. Bhartia, and R. H. Ffrench-Constant. 1998. Insecticidal toxins from the bacterium Photorhabdus luminescens. Science 280:2129-2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowen, D. J., and J. C. Ensign. 1998. Purification and characterization of a high-molecular-weight insecticidal protein complex produced by the entomopathogenic bacterium Photorhabdus luminescens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:3029-3035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ciche, T. A., C. Darby, R.-U. Ehlers, S. Forst, and H. Goodrich-Blair. 2006. Dangerous liaisons: the symbiosis of entomopathogenic nematodes and bacteria. Biol. Control 38:22-46. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duchaud, E., C. Rusniok, L. Frangeul, C. Buchrieser, A. Givaudan, S. Taourit, S. Bocs, C. Boursaux-Eude, M. Chandler, J. Charles, E. Dassa, R. Derose, S. Derzelle, G. Freyssinet, S. Gaudriault, C. Medigue, A. Lanois, K. Powell, P. Siguier, R. Vincent, V. Wingate, M. Zouine, P. Glaser, N. Boemare, A. Danchin, and F. Kunst. 2003. The genome sequence of the entomopathogenic bacterium Photorhabdus luminescens. Nat. Biotechnol. 21:1307-1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ehlers, R.-U., S. Stoessel, and U. Wyss. 1990. The influence of phase variants of Xenorhabdus spp. and Escherichia coli (Enterobacteriaceae) on the propagation of entomopathogenic nematodes of the genera Steinernema and Heterorhabditis. Rev. Nematol. 13:417-424. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodrich-Blair, H., and D. J. Clarke. 2007. Mutualism and pathogenesis in Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus: two roads to the same destination. Mol. Microbiol. 64:260-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grewal, P. S., R.-U. Ehlers, and D. I. Shapiro-Ilan. 2005. Nematodes as biocontrol agents. CABI Publishing, Wallingford, United Kingdom.

- 10.Han, R., and R.-U. Ehlers. 1998. Cultivation of axenic Heterorhabditis spp. dauer juveniles and their response to non-specific Photorhabdus luminescens food signals. Nematologica 44:425-435. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Han, R., and R.-U. Ehlers. 2001. Effect of Photorhabdus luminescens phase variants on the in vivo and in vitro development and reproduction of the entomopathogenic nematodes Heterorhabditis bacteriophora and Steinernema carpocapsae. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 35:239-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han, R. C., and R.-U. Ehlers. 1999. Trans-specific nematicidal activity of Photorhabdus luminescens. Nematology 1:687-693. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han, R. C., W. M. Wouts, and L. Li. 1991. Development and virulence of Heterorhabditis spp. strains associated with different Xenorhabdus luminescens isolates. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 58:27-32. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu, K., J. Li, and J. M. Webster. 1995. Mortality of plant-parasitic nematodes caused by bacterial (Xenorhabdus spp. and Photorhabdus luminescens) culture media. J. Nematol. 27:502-503. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qiu, X. H. 2009. Ph.D. thesis. Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China.

- 16.Sicard, M., J. B. Ferdy, S. Pagès, N. Le Brun, B. Godelle, N. Boemare, and C. Moulia. 2004. When mutualists are pathogens: an experimental study of the symbioses between Steinernema (entomopathogenic nematodes) and Xenorhabdus (bacteria). J. Evol. Biol. 17:985-993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sicard, M., S. Hering, R. Schulte, S. Gaudriault, and H. Schulenburg. 2007. The effect of Photorhabdus luminescens (Enterobacteriaceae) on the survival, development, reproduction and behaviour of Caenorhabditis elegans (Nematoda: Rhabditidae). Environ. Microbiol. 9:12-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Staskawicz, B., D. Dahlbeck, N. Keen, and C. Napoli. 1987. Molecular characterization of cloned avirulence genes from race 0 and race 1 of Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea. J. Bacteriol. 169:5789-5794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolk, C. P., Y. Cai, and J. Panoff. 1991. Use of a transposon with luciferase as reporter to identify environmental responsive genes in a cyanobacterium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:5355-5359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xie, B., K. Xu, H. X. Zhao, and S. F. Chen. 2005. Isolation of transposon mutants from Azospirillum brasilense Yu62 and characterization of genes involved in indole-3-acetic acid biosynthesis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 248:57-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang, G., A. J. Dowling, U. Gerike, R. H. ffrench-Constant, and N. R. Waterfield. 2006. Photorhabdus virulence cassettes confer injectable insecticidal activity against the wax moth. J. Bacteriol. 188:2254-2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]