Abstract

Several hepatitis A virus (HAV) and human norovirus (HuNoV) outbreaks due to consumption of contaminated berries and vegetables have recently been reported. Model experiments were performed to determine the effectiveness of freeze-drying, freeze-drying combined with heating, and steam blanching for inactivation of enteric viruses that might be present on the surface of berries and herbs. Inactivation of HAV and inactivation of feline calicivirus, a surrogate for HuNoV, were assessed by viral culturing and quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR), whereas HuNoV survival was determined only by quantitative RT-PCR. While freeze-drying barely reduced (<1.3 log10 units) the amount of HAV RNA detected in frozen produce, a greater decline in HAV infectivity was observed. The resistance of HuNoV genogroup I (GI) to freeze-drying was significantly higher than that of HuNoV GII on berries. Addition of a terminal dry heat treatment at 120°C after freeze-drying enhanced virus inactivation by at least 2 log10 units, except for HuNoV GII. The results suggest that steam blanching at 95°C for 2.5 min effectively inactivated infectious enteric viruses if they were present in herbs. Our results provide data for adjusting food processing technologies if viral contamination of raw materials is suspected.

There is growing concern over human exposure to enteric viruses through contaminated food products. Data on viral food-borne diseases are still fragmented, and workers have focused either on particular countries or on particular pathogens. Nonetheless, epidemiological evidence indicates that enteric viruses, particularly human norovirus (HuNoV), which causes acute gastroenteritis, and also hepatitis A virus (HAV), are the leading causes of food-borne illness in developed countries (14, 29, 49). While consumption of ready-to-eat foods contaminated by infected food handlers remains the major risk factor for viral food-borne outbreaks, many types of berries are increasingly being recognized as vehicles of viruses causing gastroenteritis (9, 15, 16, 18, 21, 24, 30, 34, 42) or hepatitis A outbreaks (6, 25, 41, 43, 44). Furthermore, most of the infections have been associated with consumption of minimally processed berries (i.e., frozen berries) (9, 15, 16, 24, 30, 34, 42-44).

Vegetables, including different types of salad vegetables and green onions, have also been associated with outbreaks of viral hepatitis and gastroenteritis (11, 19, 37, 45, 47). Recently, an outbreak of hepatitis A caused by ingestion of contaminated green onions resulted in three deaths in a total of 601 cases (48).

Produce may become contaminated during cultivation before harvest by contact with inadequately treated sewage or sewage-polluted water. Contamination may also occur during processing, storage, distribution, or final preparation. This can happen if produce comes into contact with infected people, contaminated water, or fomites. However, except for shellfish, foods are seldom tested for viruses. Frequently, food-borne outbreaks are suspected of being caused by enteric viruses, but because of the lack of sensitive and reliable methods such suspicions can rarely be confirmed by isolation of the virus from the implicated food. Hence, the safety of food products cannot be ensured by testing for viruses but can be ensured by prevention of contamination and implementation of food processing technologies that inactivate or eliminate viruses.

Various studies, as reviewed by Koopmans and Duizer (29), have addressed enteric virus survival after commercial processing. Most of these studies found that viruses remained viable for periods exceeding the shelf-lives of the products. Recently, we have shown that treatments commonly applied to produce (i.e., freezing, frozen storage, and washing with different sanitizers) are apparently unable to completely remove or inactivate enteric viruses (4). However, there is still no information about the efficiency of other current food processing technologies for the removal or inactivation of enteric viruses.

Vacuum freeze-drying is considered the reference process for manufacturing high-quality dehydrated products. The production of freeze-dried berries involves preliminary freezing of fresh berries, followed by placing the berries under reduced pressure with sufficient heat to sublimate ice. Vacuum freeze-drying treatment is the best method to dehydrate berries to maintain the color, flavor, and most types of antioxidants. Freeze-dried berries are commonly used by the food industry in cereals, muesli bars, chocolate products, and bakery goods.

Blanching is a critical industrial food preparation process that consists of scalding vegetables in boiling or steaming water for a short time, and it helps retain the flavor, color, and texture of vegetables by stopping enzyme action. Almost all vegetables that are to be frozen must be blanched, and blanching is also recommended for vegetables before dehydration. Blanching conditions vary, and the temperatures are generally between 75°C and 105°C (32). Therefore, studies were performed to obtain information on enteric virus inactivation when produce was subjected to freeze-drying and steam blanching.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses, cells, and infections.

Clinical stool samples positive for HuNoV genogroup I.4 (GI.4) (Valetta strain; kindly provided by RIVM, Bilthoven, The Netherlands) and GII.4 (Lordsdale; kindly provided by J. Buesa, University of Valencia, Valencia, Spain) were used as HuNoV reference material.

The cytopathogenic HM-175 strain of HAV (ATCC VR-1402), the F9 strain of feline calicivirus (FCV) (ATCC VR-782), and the vMC0 strain of mengovirus (ATCC VR-2310; kindly provided by A. Bosch, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain) were propagated and assayed in FRhK-4, CRFK, and HeLa cell monolayers, respectively. Virus stocks were subsequently produced from the same cells by using three freeze-thaw cycles and centrifugation of infected cell lysates at 660 × g for 30 min following the appearance of cytopathic effects. Infectious virus stocks were enumerated by determining the 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) with eight wells per dilution and 20 μl of inoculum per well.

Titration of viruses.

To determine infectivity titers, samples were titrated by inoculating 20-μl portions of serial fivefold dilutions of HAV and FCV into wells containing FRhk-4 and CRFK cells, respectively, grown in 96-well plates. Eight wells were assayed for each dilution. After incubation at 37°C in a CO2 incubator for 14 and 3 days for plates inoculated with HAV and FCV, respectively, the cells were observed for cytopathic effects. The infectivity titers were expressed as TCID50 per ml. The decay of viruses was determined by calculating log10 (Nx/N0), where N0 is the infectious virus titer for untreated produce and Nx is the infectious virus titer for treated produce.

Viral genome quantification.

A LightCycler 2.0 (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) was used for real-time reverse transcription (RT)-PCRs throughout this study.

Human norovirus GI and GII were quantified with a Platinum ThermoScript one-step quantitative RT-PCR system (Invitrogen AG, Basel, Switzerland) as described previously (10). Standard curves for HuNoV GI and GII were generated by amplifying 10-fold dilutions of the stool extract by real-time RT-PCR. The crossing points obtained from the assays with each dilution were used to plot a standard curve by assigning a value of 1 RT-PCR unit (PCRU) to the highest dilution showing a positive crossing point value and progressively 10-fold-higher values to the lower dilutions.

HAV RNA was quantified with a LightCycler HAV quantification kit (Roche Diagnostics) as previously described (46). The LightCycler HAV quantification kit contains HAV RNA standards that allow the number of RNA copies per sample to be estimated. This kit also includes an internal control to prevent misidentification of negative samples.

Primers and probes for FCV and mengovirus were described previously (4, 8). Standard curves were generated by performing real-time RT-PCR with 10-fold dilutions of FCV and mengovirus extracted RNA using a QIAamp viral RNA mini kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany). The crossing points obtained from the assays with each dilution were used to plot a standard curve by assigning corresponding TCID50.

Recovery of virus from food samples.

Viruses were released from the food surface as previously described (4, 5). Briefly, 15 g of berries or herbs was gently shaken for 15 min at room temperature with 60 ml of an elution buffer containing 50 mM glycine, 100 mM Tris, and 1% (wt/vol) beef extract (pH 9.5 ± 0.2). Then the food sample and diluent were transferred to a filter stomacher bag (Tempo Sacs; bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France), except for freeze-dried berries, which were mashed in the filter stomacher bag. The pH of the recovered elution buffer was adjusted to 7.0 ± 0.2, and the buffer was centrifuged at 3,500 × g for 15 min. Frozen raspberries and strawberries and freeze-dried berries were treated with pectinase by adding 300 μl of pectinase (Pectinex; Sigma, Buchs, Switzerland) to the elution buffer and gently shaken for 30 min at room temperature before centrifugation. The supernatant was concentrated to a volume of 500 μl using a Centricon Plus-70 centrifugal filter device (100K nominal molecular weight limit; Millipore, Molsheim, France).

Before testing with cell cultures, concentrated samples were decontaminated by sequential filtering through 0.45-μm and then 0.22-μm spin centrifuge tube filters (Corning, New York) pretreated with 300 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.2 ± 0.2) (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 4.3 mM Na2HPO4, 1.47 mM KH2PO4) containing 10% fetal calf serum. Filtered samples were divided in two subsamples, a 350-μl subsample for the cell culture assay and a 150-μl subsample for RNA extraction. RNA extraction was performed using a QIAamp viral RNA mini kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. Concentrated samples of raspberries and freeze-dried berries were pretreated with 300 μl of plant RNA Isolation Aid (Ambion, Cambridgeshire, United Kingdom) before RNA extraction.

A negative control was included with each group of RNA extracts. RNA extracts were either immediately analyzed by real-time RT-PCR or stored at −80°C until they were used. Positive controls with the same concentrations of viruses as the suspensions used to inoculate berries and herbs were analyzed in parallel by real-time RT-PCR to determine the fraction of particles recovered by the concentration procedure. RNA was obtained from positive controls using a QIAamp viral RNA mini kit.

Freeze-drying.

Locally purchased strawberries, raspberries, blackberries, blueberries, parsley, and basil were used in this study. A dilution of virus in phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.2 ± 0.2) was inoculated onto the surface of each 15-g portion of fresh produce by distributing 30 μl over six spots. Fifteen-gram portions of fresh berries and herbs were inoculated with about 1.6 × 106 TCID50 of HAV, 1.2 × 105 PCRU of HuNoV GI, and 2.0 × 106 PCRU of HuNoV GII. Inoculated samples were air dried in a laminar flow hood for 60 min. Batches of three samples were frozen at −20°C for at least 48 h in a steel monolayer tray. Freeze-drying trials were conducted using a vacuum freeze-dryer (Lyolab FII; ISL Biolafitte, Swindon, United Kingdom) having a condenser temperature of −70°C. Plate temperatures were applied (Fig. 1) over 18 h. After optimization of freeze-drying conditions regardless of shape and consistency (data not shown), the operating conditions consisted of 115°C for 3 h, followed by a decrease in the temperature to 60°C in 13 h and finally an increase in the temperature from 60 to 115°C in 2 h (Fig. 1). The internal temperature of whole berries was recorded by placing a probe at the center of one sample.

FIG. 1.

Example of the freeze-drying process. The dashed blue line indicates the temperature setting. The solid blue line indicates the internal temperature of berries. The solid red line indicates the product pressure, and the dashed red line indicates the chamber pressure.

Heating after freeze-drying.

Fifteen-gram portions of inoculated berries were freeze-dried as previously described and heated at 80, 100, or 120°C for 20 min in an oven (Weiss-Gallenkamp, Loughborough, United Kingdom). Each experimental condition was analyzed in triplicate. After heating, samples were processed as described above. Virus inactivation was calculated by determining log10 (Nt/N0), where N0 is the titer of virus recovered from freeze-dried berries and Nt is the titer of virus recovered from freeze-dried berries heated at a certain temperature.

Blanching.

Locally purchased parsley, basil, mint, and chives were inoculated as described above. Fifteen-gram portions of fresh herbs were inoculated with about 1.6 × 106 TCID50 of HAV, 1.6 × 106 TCID50 of FCV, 1.2 × 105 PCRU of HuNoV GI, and 2.0 × 106 PCRU of HuNoV GII. Batches of three samples were placed in a metal strainer and blanched at 95 or 75°C for 2.5 min in a “Le cuiseur vapeur automatic” (Magimix, Vicennes Cedex, France). After blanching, samples were processed as described above. The inactivation of viruses was calculated as described above.

Mengovirus control.

In order to obtain an accurate estimate of the quantity of an enteric virus, titrated mengovirus was used as a processing control as previously described (8). Briefly, ca. 5 × 103 TCID50 of mengovirus was added to the elution buffer used to release viruses from the food surface, and the virus was quantified by real-time RT-PCR at the end of the procedure (Fig. 2). The crossing point of the sample was compared to the crossing point of the positive control used in the extraction series and to a standard curve obtained by endpoint dilution. The efficiency of each extraction was determined, and virus titers were estimated for each sample (8, 10, 36).

FIG. 2.

Flow chart for the freeze-drying process. (Adapted from reference 8 with permission.)

Statistical analysis.

The significance of differences among the means for log10 (Nx/N0) was determined by the Student test using a significance level of P < 0.05 (Microsoft Office Excel; Microsoft, Redmond, WA).

RESULTS

Extraction efficiencies.

Initially, the protocol used for fresh and frozen berries was used for freeze-dried berries, without much success. Less than 1% of the inoculated viruses (HAV and HuNoV) was recovered at the end of the procedure. We suspected that this was because of loss of elution buffer after the berries became rehydrated. Therefore, freeze-dried berries were mashed in a filter stomacher bag, which improved the recovery from 2.2% to 30.6% depending on the food matrix (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Efficiency of the extraction method using mengovirus as a process control

| Product | TCID50 of mengovirus inoculateda | TCID50 of mengovirus recovered (mean ± SD)b | Efficiency (%) (mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frozen products | |||

| Blackberries | 4.8 × 103 | (9.2 ± 0.9) × 101 | 1.9 ± 1.89 |

| Blueberries | 9.1 × 103 | (4.9 ± 0.3) × 102 | 5.4 ± 3.66 |

| Raspberries | 1.2 × 103 | (2.1 ± 0.1) × 102 | 16.3 ± 0.95 |

| Strawberries | 9.0 × 103 | (8.9 ± 1.1) × 102 | 9.9 ± 1.23 |

| Basil | 4.5 × 103 | (1.4 ± 0.3) × 103 | 31.3 ± 8.66 |

| Parsley | 1.2 × 103 | (1.6 ± 0.2) × 102 | 13.7 ± 2.06 |

| Freeze-dried products | |||

| Blackberries | 4.8 × 103 | (2.6 ± 0.2) × 102 | 5.43 ± 5.66 |

| Blueberries | 9.1 × 103 | (8.7 ± 0.3) × 102 | 9.66 ± 3.99 |

| Raspberries | 1.2 × 103 | (2.7 ± 1.3) × 101 | 2.20 ± 1.10 |

| Strawberries | 9.0 × 103 | (2.1 ± 0.1) × 102 | 2.33 ± 1.77 |

| Basil | 4.5 × 103 | (1.5 ± 0.3) × 103 | 32.6 ± 8.15 |

| Parsley | 1.2 × 103 | (1.1 ± 0.1) × 102 | 9.4 ± 0.81 |

A suspension of mengovirus was extracted using a Qiagen kit and titrated by real-time RT-PCR with a standard curve constructed by using the number of mengovirus infectious units per reaction mixture.

Each inoculated food was analyzed in triplicate and extracted, and each nucleic acid suspension was titrated by real-time RT-PCR with a standard curve constructed by using the number of mengovirus infectious units per reaction mixture.

In order to prevent underestimation of recovered viruses, elution buffer was inoculated with a known concentration of mengovirus prior to processing to control the efficiency of the procedure (Fig. 2). The efficiency of the extraction procedure was calculated by comparing the numbers of recovered and inoculated mengovirus, and then the numbers of the quantified viruses recovered were more accurately estimated (8, 10, 36). For instance, the level recovery of mengovirus for frozen raspberries was ca. 16%, whereas for freeze-dried raspberries it was only ca. 2% (Table 1).

Effect of freeze-drying.

Under the optimized conditions, freeze-drying reduced the numbers of HAV on most of products by less than 1 log10 unit as determined by real-time RT-PCR. The only exception was parsley, where a 1.24-log10 unit reduction of HAV titers was observed. Furthermore, the HAV decay was significantly (P < 0.05) greater as determined by TCID50 than as determined by using the number of RNA copies except for parsley and strawberries (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Inactivation of HAV and HuNoV in frozen produce after freeze-dryinga

| Product | Inactivation of:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAV

|

HuNoV GI (PCRU) | HuNoV GII (PCRU) | ||

| No. of RNA copies | TCID50 | |||

| Blackberries | −0.61 ± 0.19 | −1.79 ± 0.08 | −0.71 ± 0.09 | −1.71 ± 0.26 |

| Blueberries | −0.98 ± 0.16 | −2.42 ± 0.25 | −1.29 ± 0.14 | −2.67 ± 0.18 |

| Raspberries | 0.29 ± 0.11 | −1.50 ± 0.35 | −0.63 ± 0.23 | −1.21 ± 0.07 |

| Strawberries | −0.85 ± 0.35 | −1.42 ± 0.22 | −0.84 ± 0.27 | −1.47 ± 0.03 |

| Basil | −0.35 ± 0.18 | −1.71 ± 0.18 | −2.00 ± 0.24 | −2.06 ± 0.16 |

| Parsley | −1.24 ± 0.19 | −1.24 ± 0.14 | −2.07 ± 0.12 | −3.52 ± 0.39 |

Inactivation was determined by real-time RT-PCR (PCRU and number of RNA copies) and virus culture (TCID50). The values are the means ± standard errors for log10 (Nx/N0), where N0 is the virus titer before freeze-drying and Nx is the titer after freeze-drying.

Overall, freeze-drying was significantly (P < 0.05) more effective for reducing the level of HuNoV GII than for reducing the level of HuNoV GI, except for basil. For HuNoV GII the greatest degree of inactivation was that for freeze-dried herbs and blueberries, and the virus titer was reduced on average by 2.7 log10 units.

When only the results for real-time RT-PCR detection after freeze-drying were compared, HAV and HuNoV GI showed similar behaviors on berries, whereas for vegetables there was appreciably less reduction of HAV titers (Table 2).

Virus survival on freeze-dried berries after heating.

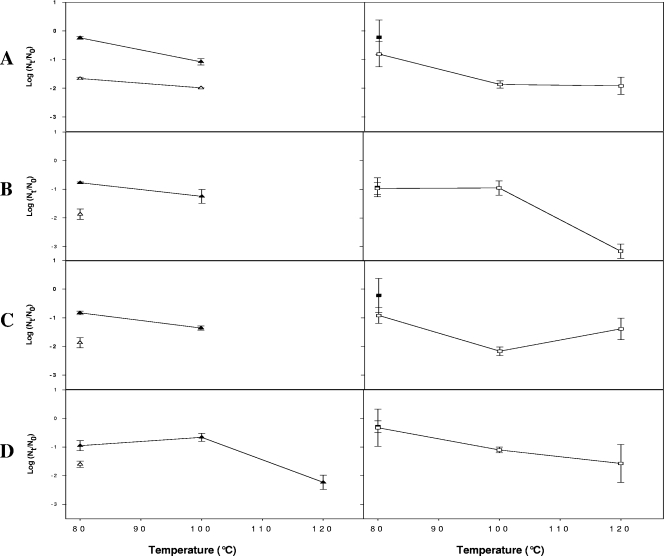

Due to the great resistance of HAV and HuNoV on freeze-dried berries, freeze-dried products were heated at 80, 100, or 120°C for 20 min. Overall, compared to the titers for freeze-dried berries, the HAV and HuNoV titers were only slightly reduced following heating at 80°C, which resulted in <1-log10 unit reductions in the numbers of HAV and HuNoV genomes (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Inactivation of HAV and HuNoV after freeze-dried berries were heated, as determined by real-time RT-PCR (PCRU or RNA copies) and virus culture (TCID50). (A) Blueberries. (B) Blackberries. (C) Raspberries. (D) Strawberries. The data are means ± standard errors for log10 (Nt/N0) where N0 is the virus titer after freeze-drying and Nt is the titer after freeze-dried berries were heated. ▵ and ▴, HAV levels determined by virus culture (▵) or the number of RNA copies (▴); ▪, HuNoV GI levels; □, HuNoV GII levels.

HAV and HuNoV GII genomes were detected in all freeze-dried berries even after heating at 100°C, whereas HuNoV GI was not detected after this treatment (Fig. 3.).

The level of infectious HAV was reduced by less than 2 log10 units by heating at 80°C, and infectious HAV was detected only in blueberries after heating at 100°C. The HAV infectious titer was reduced to undetectable levels after heating at 120°C, although corresponding numbers of RNA copies were still detected in freeze-dried strawberries.

Effect of blanching.

Enteric virus titers were significantly (P < 0.05) reduced immediately following steam blanching at 95°C for 2.5 min compared to the control (Table 3). Most HAV and FCV TCID50 were reduced by more than 3 log10 units. The exceptions were the values for HAV on parsley and FCV on chives; exact estimates of these values were not obtained because only one of the replicates was positive. Reduction of the HuNoV GI and GII titers after blanching at 95°C was very dependent on the type of herb. The greatest reduction in HuNoV GI and GII titers was observed for mint, for which the virus titer was reduced by more than 3 log10 units (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Inactivation of HAV, FCV, and HuNoV in herbs after steam blanching at 95°C for 2.5 mina

| Product | Inactivation of:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAV

|

FCV

|

HuNoV GI (PCRU) | HuNoV GII (PCRU) | |||

| No. of RNA copies | TCID50 | PCRU | TCID50 | |||

| Basil | −3.17 ± 0.29 | >−3.00 | −1.75 ± 0.06 | >−4.00 | −0.51 ± 0.11 | −1.61 ± 0.22 |

| Chives | >−4.00 | >−3.00 | −3.58 ± 0.25 | >−2.94 | >−3.00 | −2.31 ± 0.46 |

| Mint | >−4.00 | >−3.00 | −5.27 ± 0.59 | −3.17 ± 0.04 | >−3.00 | >−3.00 |

| Parsley | −3.30 ± 0.23 | >−2.41 | −1.40 ± 0.04 | >−4.00 | −1.58 ± 0.19 | −2.79 ± 0.19 |

Inactivation was determined by real-time RT-PCR (PCRU and number of RNA copies) and virus culture (TCID50). The values are means ± standard errors for log10 (Nx/N0), where N0 is the virus titer before steam blanching and Nx is the titer after steam blanching.

Generally, there was appreciably less inactivation of HAV when the temperature of steam blanching was reduced to 75°C (Table 4), and the infectious HAV titers were reduced by an average of 2 log10 units, except for chives. The reductions in the HuNoV GI levels were pretty similar to those obtained when 95°C was used, except for mint.

TABLE 4.

Inactivation of HAV, FCV, and HuNoV in herbs after steam blanching at 75°C for 2.5 mina

| Product | Inactivation of:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAV

|

FCV

|

HuNoV GI (PCRU) | HuNoV GII (PCRU) | |||

| No. of RNA copies | TCID50 | PCRU | TCID50 | |||

| Basil | −1.54 ± 0.33 | −1.87 ± 0.11 | −1.63 ± 0.21 | −3.98 ± 0.04 | −0.48 ± 0.08 | −1.46 ± 0.26 |

| Chives | −1.26 ± 0.13 | >−3.00 | −2.01 ± 0.13 | >−4.00 | >−3.00 | −1.35 ± 0.12 |

| Mint | −1.86 ± 0.13 | −1.71 ± 0.06 | −1.26 ± 0.15 | >−4.00 | −0.97 ± 0.07 | −1.58 ± 0.12 |

| Parsley | −2.10 ± 0.38 | −2.07 ± 0.15 | −3.09 ± 0.15 | −3.65 ± 0.08 | −1.60 ± 0.19 | −1.52 ± 0.08 |

Inactivation was determined by real-time RT-PCR (PCRU and number of RNA copies) and virus culture (TCID50). The values are means ± standard errors for log10 (Nx/N0), where N0 is the virus titer before steam blanching and Nx is the titer after steam blanching.

DISCUSSION

The importance of viral food-borne diseases is increasingly being recognized, and the World Health Organization has found that there is an upward trend in their incidence (15a). This is particularly pertinent to fruits and vegetables that most likely will not be cooked before consumption. Berries and vegetables are prone to be contaminated through sewage-contaminated surface water or by infected food handlers during harvesting, packaging, or food preparation, and the viruses are likely to be on the food surface. Very recently, we have shown that treatments of the sorts commonly applied to produce (i.e., freezing, frozen storage, and washing) apparently cannot totally remove or inactivate enteric viruses (4). The occurrence of outbreaks of viral disease due to the consumption of frozen berries that had been frozen for several months raises safety concerns regarding the use of potentially contaminated frozen berries in the food industry (for instance, freeze-dried berries).

Freeze-drying is widely used for the preservation of berries, but no data on its effects on enteric virus inactivation have been available previously, except for a reported 3- to 4-log10 unit reduction in poliovirus (PV) levels in various food items (22). Considering that PV is known to be less resistant to environmental conditions than other enteric viruses, it is not surprising that all human viruses used in this study were only slightly affected by freeze-drying.

The freeze-drying process used in this study involved a combination of a vacuum and heat to remove the ice by sublimation. During this process, the internal food temperature reached a maximum of 55°C for ca. 10 h (Fig. 1), which may have been responsible for the reduction in the virus level observed. Overall, enteric viruses were more resistant to freeze-drying in berries with irregular surfaces, i.e., raspberries, blackberries, and strawberries, probably because the crevices and hairlike projections present on their surface may shield viruses from environmental modification (4, 28).

Generally, the reduction in HAV infectivity after freeze-drying was less than 2 log10 units, in line with results reported by Hart and coworkers (20) for coagulation factor concentrates. These authors also showed that infectious HAV was completely inactivated after a terminal dry heat treatment for 6 h at 90°C or for 24 h at 80°C. Only residual virus was detected after 2 h of treatment at 90°C or after 8 h of treatment at 80°C (20). We initially evaluated a terminal dry heat treatment consisting of 20 min at 80°C since this treatment is currently used in factories when high counts of molds are detected. The temperature was increased further since viruses were only slightly inactivated (Fig. 3). We have shown that dry heat treatment for 20 min at 100 or 120°C is capable of inactivating infectious HAV in berries, except for blueberries treated at 100°C. However, in some instances the reduction in the number of infectious viruses did not correlate with the number of genomes detected by real-time RT-PCR. Similar findings have been reported for other inactivation treatments and viruses (1, 2, 23, 31). At the same time, HuNoV GI was detected only after heating at 80°C, whereas HuNoV GII was detected even after heating at 120°C. However, these results must be interpreted with caution when the risks from HuNoV in foods are estimated because we most likely detected noninfectious virus particles.

Enzyme inactivation is the main reason for blanching vegetables and herbs intended for freezing. Depending on the conditions used, blanching seems to inactivate bacteria present on the surface of vegetables (13, 39), but previously no data were available on its efficacy against enteric viruses. Our results showed that the heat resistance of enteric viruses varied among the herbs and was lowest for chives and mint. Again, in some instances the reduction in the number of infectious viruses did not correlate with the number of genomes detected by real-time RT-PCR. These results are in agreement with results reported for murine norovirus 1 (MNV-1) in blanched spinach. Baert and coworkers (1) reported >2-log10 unit reductions in the level of infectious MNV-1 but only a 1-log10 unit reduction when MNV-1 was detected by real-time RT-PCR.

Various processing control viruses have been used in methods for detecting HAV or noroviruses, including FCV, PV, and mengovirus (8, 34, 36, 38). The latter virus has been proposed as a processing control for HAV and HuNoV (CEN/TC 275/WG6/TAG4 of the European Union) and has successfully been used for quantification of HAV and HuNoV in naturally contaminated shellfish (8, 36). Because the recovery from frozen berries (5) and the recovery from freeze-dried berries were consistently different, mengovirus was used as a processing control for HAV and HuNoV, as suggested by Costafreda and colleagues (8). To our knowledge, this is the first time that a processing control has been used in inactivation studies in order to normalize the real numbers of viruses recovered after each treatment. This control increases the confidence in estimating the numbers of recovered viruses in nontreated and treated food samples, and the results strongly support the conclusion that the reductions described here correctly reflect the results obtained with the different food processing technologies.

Several authors have reported an unexpected high prevalence of HuNoV GI in the environment (10, 26, 36, 40) considering that most of strains circulating in humans belong to GII, with GII.4 the predominant group. It has been hypothesized that HuNoV GI is more prevalent in the environment due to its greater resistance to inactivation (10). This may also explain the high number of berry-related (9, 16, 18) and shellfish-related (3, 12, 17, 27, 32, 35) outbreaks caused by HuNoV GI. Our results have shown, for the first time, the greater resistance of HuNoV GI to certain food processing methods (i.e., freeze-drying) and to frozen storage (4). In any case, we must be cautious about concluding that HuNoV GI is more resistant since the resistance was very dependent on the type of treatment or the matrix involved. Furthermore, only one genotype of each genogroup was used in our studies.

To the best of our knowledge, HuNoV and HAV in naturally contaminated berries or vegetables have never been quantified. Data for shellfish are still scarce, but some publications reported HuNoV concentrations ranging from 102 to 104 copies per g of digestive tissues (32, 33, 35, 36, 40). HAV in naturally contaminated shellfish samples has recently been quantified, and the titers ranged from 103 to 105 HAV genomes per g of clam (8); also, Williams and Fout reported 0.2 to 224 infectious particles per 100 g shellfish meat (50). Based on these results and assuming that there are similar levels in naturally contaminated produce, we can try to estimate the risk of becoming infected. Our group reported previously that chlorinated water was the best method for virus decontamination of produce; nevertheless, we reported a <2-log10 reduction in HAV and HuNoV titers after raspberries and parsley were washed (4). Koopmans and Duizer (29) summarized the risks of consuming products that may have become contaminated with enteric viruses. The risks were categorized as negligible, low, medium, and high depending on whether processing resulted in reductions in the infectivity of common food-borne viruses of at least 4, 3, 2, and 1 log units, respectively. Considering the additive effects of the different treatments resulting in a cumulative log reduction factor, an entire commercial process, such as washing raspberries with chlorinated water, freezing, and freeze-drying, cannot completely remove or inactivate the enteric viruses in raspberries. In contrast, blanching of contaminated herbs previously washed with chlorinated water most likely reduces the risk of becoming infected to a negligible level.

The Codex Alimentarius Commission (15a) has recently proposed a new work to provide guidance for the control of viruses in food, which will include the development of a general guidance document concerning the control of HuNoV and HAV in fresh produce, bivalve mollusks, and ready-to-eat foods. The results of our study should be valuable for this and other future guidance documents. Moreover, the data reported here should serve as baseline for food processors to effectively identify mitigation and intervention strategies in the event of an outbreak and to develop quality control measures specifically for virus control.

Acknowledgments

We thank Alain Fracheboud for his technical support in the freeze-drying experiments.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 24 April 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baert, L., M. Uyttendaele, M. Vermeersch, C. E. Van, and J. Debevere. 2008. Survival and transfer of murine norovirus 1, a surrogate for human noroviruses, during the production process of deep-frozen onions and spinach. J. Food Prot. 71:1590-1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baert, L., C. E. Wobus, E. Van Coillie, L. B. Thackray, J. Debevere, and M. Uyttendaele. 2008. Detection of murine norovirus 1 by using plaque assay, transfection assay, and real-time reverse transcription-PCR before and after heat exposure. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:543-546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boxman, I. L., J. J. Tilburg, N. A. Te Loeke, H. Vennema, K. Jonker, E. de Boer, and M. Koopmans. 2006. Detection of noroviruses in shellfish in the Netherlands. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 108:391-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butot, S., T. Putallaz, and G. Sanchez. 2008. Effects of sanitation, freezing and frozen storage on enteric viruses in berries and herbs. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 126:30-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butot, S., T. Putallaz, and G. Sanchez. 2007. Procedure for rapid concentration and detection of enteric viruses from berries and vegetables. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:186-192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calder, L., G. Simmons, C. Thornley, P. Taylor, K. Pritchard, G. Greening, and J. Bishop. 2003. An outbreak of hepatitis A associated with consumption of raw blueberries. Epidemiol. Infect. 131:745-751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reference deleted.

- 8.Costafreda, M. I., A. Bosch, and R. M. Pinto. 2006. Development, evaluation and standardization of a real-time TaqMan reverse transcription-PCR assay for the quantification of hepatitis A virus in clinical and shellfish samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:3846-3855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cotterelle, B., C. Drougard, J. Rolland, M. Becamel, M. Boudon, S. Pinede, O. Traoré, K. Balay, P. Pothier, and E. Espié. 2005. Outbreak of norovirus infection associated with the consumption of frozen raspberries, France, March 2005. Eur. Surveill. 10:E050428.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.da Silva, A. K., J. C. Le Saux, S. Parnaudeau, M. Pommepuy, M. Elimelech, and F. S. Le Guyader. 2007. Removal of norovirus in wastewater treatment using real-time RT-PCR: different behavior of genogroup I and genogroup II. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:7891-7897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dentinger, C. M., W. A. Bower, O. V. Nainan, S. M. Cotter, G. Myers, L. M. Dubusky, S. Fowler, E. D. Salehi, and B. P. Bell. 2001. An outbreak of hepatitis A associated with green onions. J. Infect. Dis. 183:1273-1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Roda Husman, A. M., F. Lodder-Verschoor, H. H. van den Berg, F. S. Le Guyader, P. van Pelt, W. H. van der Poel, and S. A. Rutjes. 2007. Rapid virus detection procedure for molecular tracing of shellfish associated with disease outbreaks. J. Food Prot. 70:967-974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dipersio, P. A., P. A. Kendall, Y. Yoon, and J. N. Sofos. 2007. Influence of modified blanching treatments on inactivation of Salmonella during drying and storage of carrot slices. Food Microbiol. 24:500-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.European Food Safety Authority. 2007. The community summary report on trends and sources of zoonoses, zoonotic agents, antimicrobial resistance and foodborne outbreaks in the European Union in 2006. EFSA J. 130:3-352. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Falkenhorst, G., L. Krusell, M. Lisby, S. B. Madsen, B. Bottiger, and K. Molbak. 2005. Imported frozen raspberries cause a series of norovirus outbreaks in Denmark, 2005. Eur. Surveill. 10:E050922.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15a.FAO/WHO. 2008. Microbiological hazards in fresh leafy vegetables and herbs: meeting report. Microbiological Risk Assessment Series No. 14. FAO/WHO, Rome, Italy.

- 16.Fell, G., M. Boyens, and S. Baumgarte. 2007. Frozen berries as a risk factor for outbreaks of norovirus gastroenteritis. Results of an outbreak investigation in the summer of 2005 in Hamburg. Bundesgesundheitsbl. Gesundheitsforsch. Gesundheitsschutz. 50:230-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gallimore, C. I., J. S. Cheesbrough, K. Lamden, C. Bingham, and J. J. Gray. 2005. Multiple norovirus genotypes characterised from an oyster-associated outbreak of gastroenteritis. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 103:323-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaulin, C. D., D. Ramsay, P. Cardinal, and M. A. D'Halevyn. 1999. Epidemic of gastroenteritis of viral origin associated with eating imported raspberries. Can. J. Public Health 90:37-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grotto, I., M. Huerta, R. D. Balicer, T. Halperin, D. Cohen, N. Orr, and M. Gdalevich. 2004. An outbreak of norovirus gastroenteritis on an Israeli military base. Infection 32:339-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hart, H. F., W. G. Hart, J. Crossley, A. M. Perrie, D. J. Wood, A. John, and F. McOmish. 1994. Effect of terminal (dry) heat treatment on non-enveloped viruses in coagulation factor concentrates. Vox Sang. 67:345-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hedlund, K. O., E. Rubilar-Abreu, and L. Svensson. 2000. Epidemiology of calicivirus infections in Sweden, 1994-1998. J. Infect. Dis. 181:S275-S280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heidelbaugh, N. D., and D. J. Giron. 1969. Effect of processing on recovery of polio virus from inoculated foods. J. Food. Sci. 34:239-241. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hewitt, J., and G. E. Greening. 2004. Survival and persistence of norovirus, hepatitis A virus, and feline calicivirus in marinated mussels. J. Food Prot. 67:1743-1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hjertqvist, M., A. Johansson, N. Svensson, P. E. Abom, C. Magnusson, M. Olsson, K. O. Hedlund, and Y. Andersson. 2006. Four outbreaks of norovirus gastroenteritis after consuming raspberries, Sweden, June-August 2006. Eur. Surveill. 11:E060907.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hutin, Y. J., V. Pool, E. H. Cramer, O. V. Nainan, J. Weth, I. T. Williams, S. T. Goldstein, K. F. Gensheimer, B. P. Bell, C. N. Shapiro, M. J. Alter, and H. S. Margolis. 1999. A multistate, foodborne outbreak of hepatitis A. N. Engl. J. Med. 340:595-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jothikumar, N., J. A. Lowther, K. Henshilwood, D. N. Lees, V. R. Hill, and J. Vinje. 2005. Rapid and sensitive detection of noroviruses by using TaqMan-based one-step reverse transcription-PCR assays and application to naturally contaminated shellfish samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:1870-1875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kageyama, T., M. Shinohara, K. Uchida, S. Fukushi, F. B. Hoshino, S. Kojima, R. Takai, T. Oka, N. Takeda, and K. Katayama. 2004. Coexistence of multiple genotypes, including newly identified genotypes, in outbreaks of gastroenteritis due to norovirus in Japan. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:2988-2995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kniel, K. E., D. S. Lindsay, S. S. Sumner, C. R. Hackney, M. D. Pierson, and J. P. Dubey. 2002. Examination of attachment and survival of Toxoplasma gondii oocysts on raspberries and blueberries. J. Parasitol. 88:790-793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koopmans, M., and E. Duizer. 2004. Foodborne viruses: an emerging problem. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 90:23-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Korsager, B., S. Hede, H. Boggild, B. Bottiger, and K. Molbak. 2005. Two outbreaks of norovirus infections associated with the consumption of imported frozen raspberries, Denmark, May-June 2005. Eur. Surveill. 10:E050623.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lamhoujeb, S., I. Fliss, S. E. Ngazoa, and J. Jean. 2008. Evaluation of the persistence of infectious human noroviruses on food surfaces by using real-time nucleic acid sequence-based amplification. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:3349-3355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Le Guyader, F. S., F. Bon, D. DeMedici, S. Parnaudeau, A. Bertone, S. Crudeli, A. Doyle, M. Zidane, E. Suffredini, E. Kohli, F. Maddalo, M. Monini, A. Gallay, M. Pommepuy, P. Pothier, and F. M. Ruggeri. 2006. Detection of multiple noroviruses associated with an international gastroenteritis outbreak linked to oyster consumption. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:3878-3882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Le Guyader, F. S., J. C. Le Saux, K. Ambert-Balay, J. Krol, O. Serais, S. Parnaudeau, H. Giraudon, G. Delmas, M. Pommepuy, P. Pothier, and R. L. Atmar. 2008. Aichi virus, norovirus, astrovirus, enterovirus, and rotavirus involved in clinical cases from a French oyster-related gastroenteritis outbreak. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:4011-4017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Le Guyader, F. S., C. Mittelholzer, L. Haugarreau, K. O. Hedlund, R. Alsterlund, M. Pommepuy, and L. Svensson. 2004. Detection of noroviruses in raspberries associated with a gastroenteritis outbreak. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 97:179-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Le Guyader, F. S., F. H. Neill, E. Dubois, F. Bon, F. Loisy, E. Kohli, M. Pommepuy, and R. L. Atmar. 2003. A semiquantitative approach to estimate Norwalk-like virus contamination of oysters implicated in an outbreak. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 87:107-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Le Guyader, F. S., S. Parnaudeau, J. Schaeffer, A. Bosch, F. Loisy, M. Pommepuy, and R. L. Atmar. 2009. Detection and quantification of noroviruses in shellfish. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:618-624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Long, S. M., G. K. Adak, S. J. Brien, and I. A. Gillespie. 2002. General outbreaks of infectious intestinal disease linked with salad vegetables and fruit, England and Wales, 1992-2000. Commun. Dis. Public Health 5:101-105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lowther, J. A., K. Henshilwood, and D. N. Lees. 2008. Determination of norovirus contamination in oysters from two commercial harvesting areas over an extended period, using semiquantitative real-time reverse transcription PCR. J. Food Prot. 71:1427-1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mazzotta, A. S. 2001. Heat resistance of Listeria monocytogenes in vegetables: evaluation of blanching processes. J. Food Prot. 64:385-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nishida, T., O. Nishio, M. Kato, T. Chuma, H. Kato, H. Iwata, and H. Kimura. 2007. Genotyping and quantitation of noroviruses in oysters from two distinct sea areas in Japan. Microbiol. Immunol. 51:177-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Niu, M. T., L. B. Polish, B. H. Robertson, B. K. Khanna, B. A. Woodruff, C. N. Shapiro, M. A. Miller, J. D. Smith, J. K. Gedrose, M. J. Alter, and H. S. Margolis. 1992. Multistate outbreak of hepatitis A associated with frozen strawberries. J. Infect. Dis. 166:518-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ponka, A., L. Maunula, C.-H. von Bonsdorff, and O. Lyytikainen. 1999. An outbreak of calicivirus associated with consumption of frozen raspberries. Epidemiol. Infect. 123:469-474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ramsay, C. N., and P. A. Upton. 1989. Hepatitis A and frozen raspberries. Lancet i:43-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reid, T. M., and H. G. Robinson. 1987. Frozen raspberries and hepatitis A. Epidemiol. Infect. 98:109-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosenblum, L. S., I. R. Mirkin, D. T. Allen, S. Safford, and S. C. Hadler. 1990. A multifocal outbreak of hepatitis A traced to commercially distributed lettuce. Am. J. Public Health 80:1075-1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sanchez, G., S. Populaire, S. Butot, T. Putallaz, and H. Joosten. 2006. Detection and differentiation of human hepatitis A strains by commercial quantitative real-time RT-PCR tests. J. Virol. Methods 132:160-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Warner, R. D., R. W. Carr, F. K. McCleskey, P. C. Johnson, L. M. Elmer, and V. E. Davison. 1991. A large nontypical outbreak of Norwalk virus. Gastroenteritis associated with exposing celery to nonpotable water and with Citrobacter freundii. Arch. Intern. Med. 151:2419-2424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wheeler, C., T. M. Vogt, G. L. Armstrong, G. Vaughan, A. Weltman, O. V. Nainan, V. Dato, G. Xia, K. Waller, J. Amon, T. M. Lee, A. Highbaugh-Battle, C. Hembree, S. Evenson, M. A. Ruta, I. T. Williams, A. E. Fiore, and B. P. Bell. 2005. An outbreak of hepatitis A associated with green onions. N. Engl. J. Med. 353:890-897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Widdowson, M. A., A. Sulka, S. N. Bulens, R. S. Beard, S. S. Chaves, R. Hammond, E. D. Salehi, E. Swanson, J. Totaro, R. Woron, P. S. Mead, J. S. Bresee, S. S. Monroe, and R. I. Glass. 2005. Norovirus and foodborne disease, United States, 1991-2000. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11:95-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williams, F. P., and G. S. Fout. 1992. Contamination of shellfish by stool-shed viruses: methods of detection. Environ. Sci. Technol. 26:689-696. [Google Scholar]