Summary

Neuronal L-type calcium channels contribute to dendritic excitability and activity-dependent changes in gene expression that influence synaptic strength. Phosphorylation-mediated enhancement of L-type channels containing the CaV1.2 pore-forming subunit is promoted by A-kinase anchoring proteins (AKAPs) that target cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) to the channel. Although PKA increases L-type channel activity in dendrites and dendritic spines, the mechanism of enhancement in neurons remains poorly understood. Here we show that CaV1.2 interacts directly with AKAP79/150, which binds both PKA and the Ca2+/calmodulin-activated phosphatase, calcineurin (CaN). Co-targeting of PKA and CaN by AKAP79/150 confers bidirectional regulation of L-type current amplitude in transfected HEK293 cells and hippocampal neurons. However, anchored CaN dominantly suppresses PKA enhancement of the channel. Additionally, activation of the transcription factor NFATc4 via local Ca2+ influx through L-type channels requires AKAP79/150, suggesting that this signaling complex promotes neuronal L channel signaling to the nucleus through NFATc4.

Introduction

The activity of voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ channels is tuned by cAMP (Reuter, 1967; Tsien et al., 1972). This form of ion channel modulation has been extensively studied in heart, where it is prominent in the control of cardiac rate and contractility. In neurons, L-type Ca2+ channels are subject to a similar kind of modulation (Gray and Johnston, 1987), but the phenomenon has received much less attention in these cells. Phosphorylation of CaV1.2-based L-type channels by cAMP-dependent kinase (PKA) enhances L-type Ca2+ currents by increasing the opening probability of individual channels (Bean et al., 1984; Yue et al., 1990). Considerable evidence indicates that enhancement of current occurs in response to PKA-mediated phosphorylation of Ser1928 in the C-terminal tail of the pore-forming CaV1.2 subunit (reviewed by Catterall, 2000), although additional sites on the CaV1.2 subunit (Ganesan et al., 2006) and the CaV β subunit (Bunemann et al., 1999) have been implicated in this regulation as well.

In dendrites of hippocampal pyramidal neurons, PKA activation by cAMP enhances L-type channel current (Hoogland and Saggau, 2004; Kavalali et al., 1997). In these neurons, two L-type channel isotypes are present, but CaV1.2 channels outnumber CaV1.3 channels by nearly 4:1 (Hell et al., 1993) and CaV1.2 channels have been identified in macromolecular complexes containing β2 adrenergic receptors, adenylyl cyclases and PKA (Davare et al., 2001), observations which together suggest that CaV1.2 is likely to be a dominant isotype under the control of cAMP in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. L-type channels contribute about half of the total voltage-gated Ca2+ current in hippocampal pyramidal neurons (Mintz et al., 1992), and they are thought to participate in the control of dendritic excitability and help couple neuronal excitation to transcription of Ca2+-regulated genes (Bading et al., 1993; Dolmetsch et al., 2001; Graef et al., 1999; Impey et al., 1996; Mermelstein et al., 2000; Murphy et al., 1991). Postsynaptic L-type Ca2+ channels are critical in initiating long-lasting changes in synaptic strength that are dependent upon protein synthesis but independent of NMDA receptor activation (Grover and Teyler, 1990). Accordingly, knockout in hippocampus and neocortex of the CaV1.2 L-type channel impairs both NMDA receptor-independent late-phase LTP and hippocampus-dependent spatial learning (Moosmang et al., 2005). In contrast, knockout of the other major L-type channel isotype in brain, CaV1.3, has no effect on either synaptic plasticity or learning (Clark et al., 2003).

Many PKA substrates depend upon A-kinase anchoring proteins (AKAPs) for efficient phosphorylation by PKA. It has recently emerged that AKAPs often anchor PKA directly to the phosphorylation target, helping to explain how PKA can act specifically despite its wide array of substrates. Thus modulation by PKA of cardiac and skeletal muscle Ca2+ channels requires a modified leucine zipper-mediated interaction between AKAP15 (also known as AKAP18) and the α1 subunit of these channels (Hulme et al., 2003; Hulme et al., 2002). But while AKAP15 directs PKA alone to substrates, other AKAPs act as signaling integrators by binding additional regulators of PKA targets. AKAP79/150 (79 human/150 rodent) is the prototypical example of a multivalent anchoring protein, simultaneously binding PKA and the calcium-calmodulin (Ca2+/CaM)-activated phosphatase calcineurin (CaN; protein phosphatase 2B) (Oliveria et al., 2003). This AKAP79/150-based complex bearing an opposed kinase and phosphatase is present in the postsynaptic density within dendritic spines of neurons (Colledge et al., 2000; Klauck et al., 1996). AKAP79/150 has emerged as an important organizer of signaling events underlying excitatory synaptic plasticity, for example in the control of AMPA receptor down regulation during long-term synaptic depression (reviewed by Bauman et al., 2004). While it has been previously demonstrated that coexpression of AKAP79 with CaV1.2 promotes PKA phosphorylation of the channel in HEK293 cells (Gao et al., 1997), past work has not addressed the role of CaN anchoring in channel modulation nor whether AKAP79/150 is involved in regulation by PKA of L-type channels in neurons.

Here we demonstrate that AKAP79/150-anchored CaN controls neuronal L-type Ca2+ channel activity and is also critical for at least one form of L channel-dependent signaling to the nucleus. We show that endogenous AKAP150 and CaV1.2 are present together in macromolecular complexes isolated from cultured hippocampal neurons, and that reconstitution of this complex in HEK293 cells requires a direct interaction between modified leucine zipper motifs in both proteins. We show that, in neurons, enhancement of L-type current by PKA requires anchoring of this kinase by AKAP79/150. Our results reveal a powerful opposition to PKA by CaN, which profoundly attenuates enhancement of channel current. We also demonstrate that AKAP79/150 targeting of CaN is necessary to couple Ca2+ influx via L-type channels to activation of the transcription factor NFATc4. Our results suggest that, like the interaction between CaM and the proximal portion of the CaV1.2 C-terminus that underlies both Ca2+-dependent channel inactivation and control of nuclear signaling through cyclic AMP response element binding protein (CREB), the AKAP79/150 interaction with the distal C-terminus of the channel confers two distinct properties on neuronal L-type Ca2+ channels: reciprocal regulation of channel phosphorylation by CaN and PKA, and control of downstream signaling to the nucleus through NFATc4.

Results

CaV1.2 and AKAP79/150 interact directly via modified leucine zipper motifs

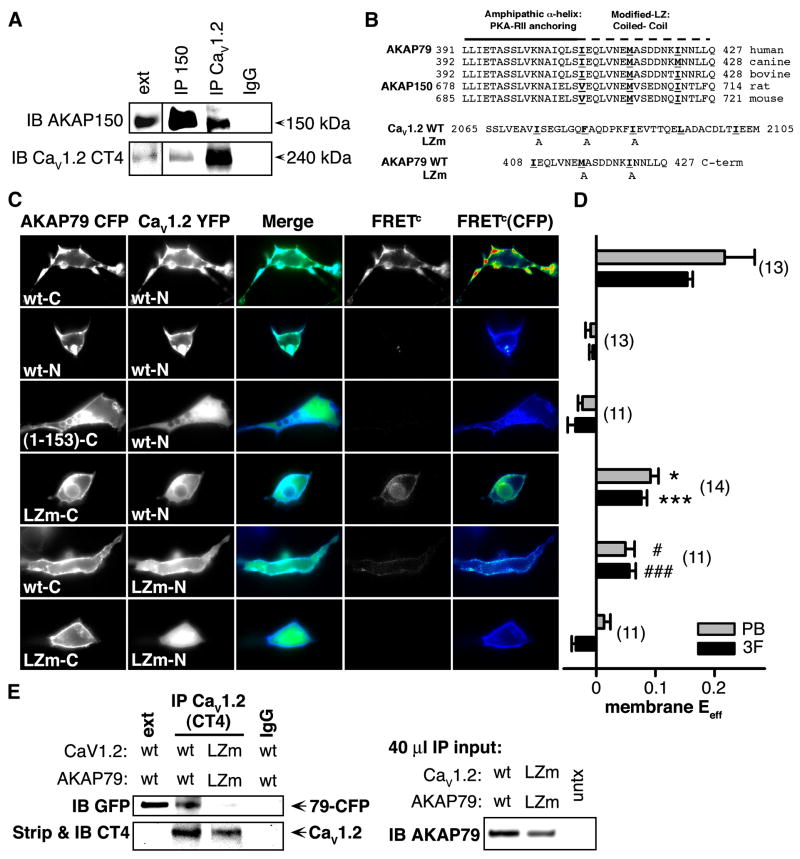

In hippocampal pyramidal neurons AKAP79/150 and CaV1.2 channels have a similar sub-cellular distribution, including localization to dendritic spines. Based on this pattern and the known interaction of AKAP15 with L-type Ca2+ channels (Hulme et al., 2002; 2003), we examined the possibility that neuronal CaV1.2 channels might reside with AKAP150 in a macromolecular complex. Using extracts from cultured rat hippocampal neurons, we found that a well-characterized antibody directed against the distal C-terminus of CaV1.2 (Gao et al., 2001) immunoprecipitated (IP’d) AKAP150 along with the channel (Figure 1A). Likewise, an antibody directed against AKAP150 IP’d full-length (> 200 kDa) CaV1.2 along with AKAP150, indicating that AKAP150 and CaV1.2 are present together in macromolecular complexes in neurons.

Figure 1. CaV1.2 and AKAP79/150 interact directly.

(A) Lysates from primary cultured hippocampal neurons (12–17 DIV) were immunoprecipitated (IP) and then immunoblotted (IB) with anti-AKAP150 or anti-CaV1.2 C-terminal (CT4) antibodies (n = 3). Extract lane exposure times were 5 min, all other exposure times were 1 min. Control lane (IgG, right), IP with non-specific rabbit IgG.

(B) Top, Alignment of human AKAP79, rat AKAP150, and orthologs from other species showing conservation of heptad-spaced hydrophobic residues between the end of the PKA-RII anchoring region and the C-terminus. Bottom, LZ motif alanine substitution mutants (LZm) introduced into AKAP79 and CaV1.2.

(C) Micrographs of transfected HEK293 cells showing subcellular localization of AKAP79-CFP (donor), CaV1.2-YFP (acceptor), CFP-YFP colocalization (Merge), and corrected, sensitized CFP-YFP FRET (FRETc; monochrome), and FRETC gated to donor intensity (FRETC(CFP); pseudocolor). N and C indicate fluorophore fusion to the N- or C-terminus.

(D) Effective FRET efficiency (Eeff) calculated from both 3-filter set measurements (3F) and YFP-acceptor photobleach (PB) measurements from the same cells (n values indicated in parentheses; * P = 0.025, # P = 0.018, *** P = 2.46 × 10−6, ### P = 4.20 × 10−7, relative to the upper row of data).

(E) Left, LZ mutations disrupt coIP of CaV1.2 and AKAP79 in HEK 293 cells. Lysates from cells transfected with either wt or LZm forms of CaV1.2 and AKAP79-CFP were IP’d with the anti-CaV1.2 CT4 antibody and then probed by western blotting with an anti-GFP antibody that recognizes CFP-fused AKAP79. The same blot was stripped of anti-GFP and re-probed with the anti-CaV1.2 CT4 antibody. Extract lane was loaded with 50 μg total protein, CaV1.2 band is visible on the strip and re-probe blot at longer exposure times as in A. Right, Western blot of 40 μl IP input lysates. Untransfected control lysate marked as untx.

AKAP15 associates with CaV1.1 in skeletal muscle and with CaV1.2 in cardiac muscle through a modified leucine zipper (LZ) interaction (Hulme et al., 2002; 2003). Examination of the amino acid sequences of AKAP79/150 reveals a similar motif of conserved, heptad-spaced hydrophobic residues in the C-termini of these homologs as well (Figure 1B, top). To test whether CaV1.2 interacts closely, perhaps directly, with AKAP79/150, we used fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) measurements from HEK293 cells co-transfected with AKAP79 fused to enhanced cyan fluorescent protein (AKAP79-CFP) and CaV1.2 fused to enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (CaV1.2-YFP). In HEK293 cells transfected with this pair of fluorescent constructs, we estimated FRET using two independent approaches: a three filter-based method that yields corrected, sensitized FRET images (FRETC, 3F) and a donor-dequenching method based on acceptor photobleaching (PB) (Figure 1C,D). Images of HEK293 cells co-expressing CaV1.2-YFP and AKAP79-CFP tagged on its C terminus (wt-C) showed extensive colocalization of the channel and AKAP at the plasma membrane (Figure 1C, top row). Further, a strong, membrane-localized FRETC signal was evident in these cells; images of FRETC gated to the energy donor’s signal intensity, FRETC(CFP), are presented on a pseudocolor-coded intensity scale. The energy transfer efficiency (Eeff) at the plasma membrane was calculated using information from the CFP, YFP and raw FRET images (black bars in Figure 1D) and, alternatively, from acceptor photobleach measurements of FRET carried out subsequently in the same cells (gray bars in Figure 1D). Additional FRET data and analysis are presented in Figure S1.

In cells co-expressing CaV1.2-YFP and N terminal-tagged AKAP79-CFP (wt-N), imaging revealed that the channel and AKAP were again colocalized at the plasma membrane. For this fluorescent pair, however, no energy transfer was detectable. The absence of FRET in this case presumably reflects either an increased spatial separation between the fluorescent moieties or an unfavorable orientation between them. Neither colocalization nor FRET were observed when only the membrane-targeting domain of AKAP79 (residues 1-153) was co-expressed with CaV1.2, indicating that the C-terminal portion of AKAP79 is necessary for association with CaV1.2 at the plasma membrane. To specifically probe the role of the modified LZ motif of AKAP79 in the interaction with CaV1.2, we introduced point mutations at two positions in the anchoring protein (Figure 1B, bottom; Hulme et al., 2003). Energy transfer between this C terminal-tagged 79LZm-CFP mutant and CaV1.2-YFP was significantly reduced compared to cells co-expressing C terminal-tagged non-mutant form of AKAP79 and CaV1.2-YFP. Examination of the images also suggests that colocalization of the 79LZm mutant with the channel appeared to be reduced. Point mutations introduced into the CaV1.2 modified LZ also significantly reduced FRET and colocalization between channel and anchoring protein. Coexpression of both LZ mutants virtually eliminated FRET and colocalization, similar to cells expressing only the AKAP79 targeting domain. We extended these findings by carrying out coIPs from HEK293 cell lysates of heterologously-expressed CaV1.2 and AKAP79. In these experiments, LZm mutations disrupted coIP of AKAP79 and Cav1.2; the effect of the LZm mutations cannot be explained by substantial differences in levels of AKAP in the lysate or channel in the IP (Figure 1E, right and bottom left). Finally, the current density recorded from cells transfected with CaV1.2LZm and AKAP79LZm was significantly smaller than for cells expressing the wild type forms (wt/wt 40.6 ± 6.3 pA/pF; LZm/LZm 21.7 ± 5.0 pA/pF, P = 0.030; n = 15; Table S1). Together these results suggest that CaV1.2 and AKAP79 interact directly via modified leucine zipper motifs present in the C-termini of both proteins, and that this interaction promotes channel surface expression in HEK293 cells.

Disruption of PKA anchoring decreases CaV1.2 current amplitude

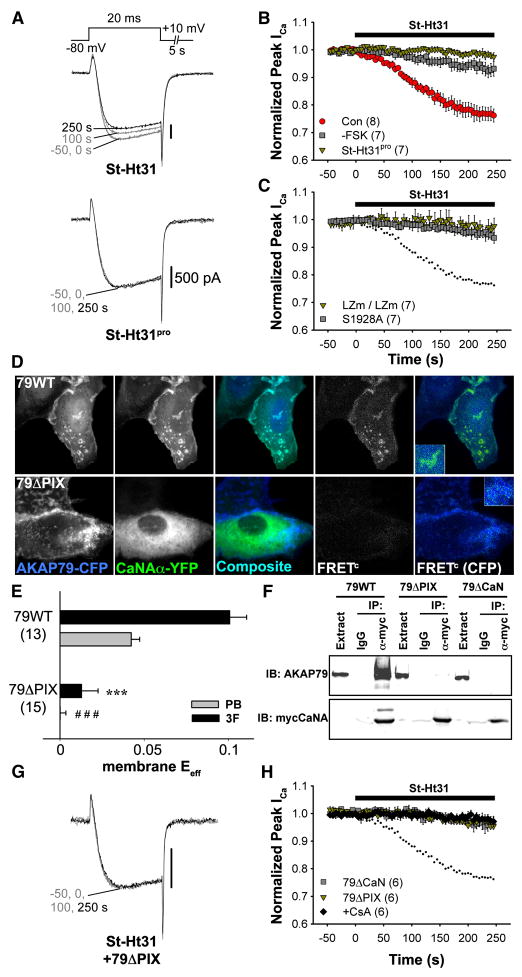

It has been previously demonstrated that expression of AKAP79 promotes phosphorylation by PKA of CaV1.2 channels heterologously expressed in HEK293 cells (Gao et al., 1997), and that protein phosphatase 2A opposes the effect of PKA on Ba2+ currents carried by CaV1.2 (Hall et al., 2006). However, AKAP79/150 is known to co-bind PKA and the Ca2+/CaM-activated phosphatase, CaN (Oliveria et al., 2003). To test whether CaN shares in the regulation of L-type channel activity, we allowed CaN activation via Ca2+ influx (rather than Ba2+) through CaV1.2 channels and we dialyzed cells intracellularly with 10 mM EGTA, which allows rises in Ca2+ concentration only in the vicinity of the channel (Deisseroth et al., 1996; Marty and Neher, 1985). While cAMP was elevated with forskolin (FSK), we acutely disrupted PKA anchoring by applying in the extracellular solution a stearated, membrane-permeant peptide, St-Ht31, which resembles the AKAP79 binding site for PKA (Carr et al., 1992; Snyder et al., 2005). In HEK293 cells transfected with CaV1.2 channel subunits and AKAP79-YFP, application of St-Ht31 caused a rapid decrease in whole-cell Ca2+ current amplitude (Figure 2A,B), as though channel phosphorylation and current enhancement by PKA were diminished by loss of PKA from the AKAP79/CaV1.2 complex (non-stearated Ht31 had a similar effect when included in the pipet solution, Figure S2). No decrease in current amplitude was observed when an inactive form of the peptide (St-Ht31pro) was applied, and the effect of St-Ht31 was much smaller in the absence of FSK. In FSK-stimulated cells transfected with LZm mutants of AKAP79 and CaV1.2, current amplitude was unaffected by St-Ht31. Substitution of alanine at the putative site of PKA phosphorylation (S1928) also occluded St-Ht31 action (Figure 2C). The occlusion of St-Ht31 action by mutations in the LZm domains or at S1928 are consistent with the ideas that the LZm domains sustain channel-AKAP interaction that is needed for efficient phosphorylation of the channel, and that S1928 is a critical target of phosphorylation by PKA.

Figure 2. Down-regulation of CaV1.2 currents in HEK293 cells following disruption of PKA anchoring.

(A) Representative CaV1.2 current records demonstrating the effect of St-Ht31 (top) or its inactive analog, St-Ht31pro (bottom), applied from 0 s onward to forskolin (FSK)-stimulated cells co-transfected with AKAP79-YFP and CaV1.2 channel subunits.

(B) Average time course of St-Ht31 effect on peak current amplitude. All experiments were performed in the presence of FSK except where otherwise indicated. Black bar indicates duration of St-Ht31 application. (Con), Current down-regulation in response to St-Ht31 in cells transfected with wild type CaV1.2 and AKAP79.

(Con), Current down-regulation in response to St-Ht31 in cells transfected with wild type CaV1.2 and AKAP79. (-FSK), Effect of St-Ht31 in the absence of FSK.

(-FSK), Effect of St-Ht31 in the absence of FSK.  , (St-Ht31pro) Response to application of a proline-substituted form of St-Ht31.

, (St-Ht31pro) Response to application of a proline-substituted form of St-Ht31.

(C) St-Ht31 application to cells coexpressing either LZm forms CaV1.2 and AKAP79 (LZm/LZm,  ), or the CaV1.2 phosphorylation site mutant S1928A and wild-type AKAP79 (S1928A,

), or the CaV1.2 phosphorylation site mutant S1928A and wild-type AKAP79 (S1928A,  ).

).

(D) Representative micrographs of COS7 cells demonstrating subcellular localization and 3-filter sensitized FRETC (presented as in Figure 1C) between CFP-labeled AKAP79 (79WT, top) or AKAP79 lacking the core PXIXIT-like motif of the CaN binding site (79ΔPIX, bottom) and CaN A-YFP.

(E) Effective membrane FRET efficiencies (Eeff) for AKAP79WT-CFP or AKAP79ΔPIX-CFP and CaN A-YFP as measured by acceptor photobleaching (PB) and 3-filter (3F) methods (n values indicated in parentheses; *** P = 1.38 × 10−6 and ### P = 2.16 × 10−7).

(F) Top, immunoprecipitations (IP) of myc-tagged CaNA (α-myc) from lysates of HEK293 cells transfected with myc-CaNA and either 79WT, 79ΔPIX or AKAP79ΔCaN, probed with anti-AKAP79. Bottom, the same blot was stripped of anti-AKAP79 and re-probed with anti-myc (n = 3 for both panels).

(G) Representative current records from HEK293 cells expressing 79ΔPIX-YFP and wild type CaV1.2 exposed to St-Ht31 beginning at 0 s.

(H) Average peak current time course following St-Ht31 application to cells expressing wild type CaV1.2 and 79ΔCaN-YFP( ) or 79ΔPIX-YFP (

) or 79ΔPIX-YFP ( ), or wild type CaV1.2 and AKAP79-YFP in the presence of the CaN inhibitor cyclosporin A (CsA, ◆). In C and H, small dots reproduce the time course of St-Ht31 action in the control condition shown in B as

), or wild type CaV1.2 and AKAP79-YFP in the presence of the CaN inhibitor cyclosporin A (CsA, ◆). In C and H, small dots reproduce the time course of St-Ht31 action in the control condition shown in B as  .

.

The effect on CaV1.2 of disruption of PKA anchoring requires CaN anchoring to a PXIXIT-like motif

We have previously identified a CaN binding region in AKAP79 between residues 315-360, and within this region is a motif (PIAIIIT; residues 337-343) that resembles the consensus sequence for CaN binding (PXIXIT) (Dell’Acqua et al., 2002). To test whether this motif represents the core of the CaN binding site in AKAP79, we coexpressed AKAP79-CFP and CaNA-YFP in COS7 cells. Deletion of the seven residues composing the PXIXIT-like motif (79ΔPIX) disrupted both AKAP79 targeting of CaN to membrane structures and FRET between AKAP79-CFP and CaNA-YFP (Figure 2D,E). Deletion of the PXIXIT-like motif was as effective in disrupting coIP of AKAP79 with myc-tagged CaNA as was deleting the entire CaN binding region (residues 315-360; 79ΔCaN) (Figure 2F).

We next tested whether CaN activity was responsible for decreasing current amplitude after disruption of PKA anchoring. St-Ht31 had no effect on FSK-stimulated cells expressing either 79ΔCaN-YFP or the 79ΔPIX-YFP (Figure 2G,H), and was also ineffective in the presence of the CaN inhibitor cyclosporin A (CsA). We conclude that St-Ht31 decreases CaV1.2 current amplitude by promoting unopposed dephosphorylation of CaV1.2 by AKAP79-anchored CaN.

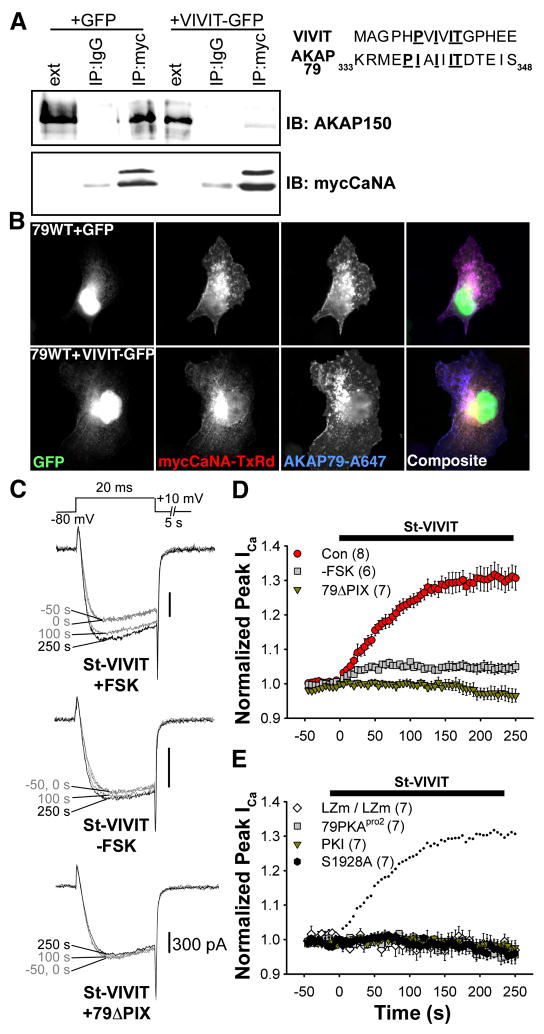

VIVIT disrupts CaN anchoring and reveals opposition to enhancement of CaV1.2 by PKA

To further probe the role of AKAP79/150-anchored CaN in regulation of CaV1.2 channels, we sought a molecular tool analogous to Ht31 that would disrupt CaN binding to AKAP79/150 but not inhibit the enzyme’s phosphatase activity. Recently, the VIVIT peptide has been shown to disrupt CaN binding to a PXIXIT-docking motif in NFAT transcription factors without inhibiting the phosphatase (Aramburu et al., 1999; Li et al., 2004). The presence of a PXIXIT-like motif in AKAP79/150 suggested that VIVIT might be effective in disrupting binding of CaN to AKAP79/150. To test the applicability of VIVIT in our system, we first studied the effect of expressing VIVIT-GFP in cells transfected with AKAP150 and myc-tagged CaNA. As shown in Figure 3A, coIP of AKAP150 with myc-CaNA was prevented by VIVIT-GFP. Immunostaining of COS7 cells transfected with AKAP79 and myc-CaNA shows that expression of VIVIT-GFP also disrupts anchoring of CaN to membrane structures by AKAP79 (Figure 3B). These data suggested that VIVIT competitively disrupts CaNA binding to AKAP79/150, at least when chronically present in cells.

Figure 3. VIVIT disrupts AKAP79/150 anchoring of CaN and increases CaV1.2 current amplitude.

(A) Immunoprecipitations (IP) of myc-tagged CaNA (myc) from lysates of HEK293 cells transfected with myc-CaNA, AKAP150 and either GFP or VIVIT-GFP, probed with anti-AKAP150.

(B) Micrographs of COS7 cells demonstrating subcellular localization of transfected AKAP79 (indirectly immunolabeled with Alexa Fluor 647) and myc-tagged CaN (indirectly immunolabeled with Texas Red) in cells expressing either GFP or VIVIT-GFP. Right, sequence of the entire VIVIT peptide and residues 333-348 of AKAP79.

(C) Representative currents showing the effect St-VIVIT applied beginning at 0 s on cells co-transfected with AKAP79-YFP and CaV1.2 channel subunits in the presence (top) or absence (middle) of FSK, or in FSK-stimulated cells expressing AKAP79ΔPIX (bottom).

(D) Average time course of St-VIVIT effect on peak current amplitude. Currents were recorded in FSK except where otherwise indicated. Black bar indicates the duration of St-VIVIT application.  (Con), Current up-regulation in response to St-VIVIT in cells transfected with wild type CaV1.2 and AKAP79.

(Con), Current up-regulation in response to St-VIVIT in cells transfected with wild type CaV1.2 and AKAP79.  (-FSK), Effect of St-VIVIT in the absence of FSK.

(-FSK), Effect of St-VIVIT in the absence of FSK.  (79ΔPIX) Effect of St-VIVIT in cells expressing 79ΔPIX-YFP.

(79ΔPIX) Effect of St-VIVIT in cells expressing 79ΔPIX-YFP.

(E) St-VIVIT application to cells expressing LZm forms of both CaV1.2 and AKAP79 (LZm/LZm, ◇), wild type CaV1.2 and a PKA binding-deficient AKAP79 containing A396P and I404P mutations (79pro2,  ), the CaV1.2 phosphorylation site mutant S1928A and wild type AKAP79 (S1928A,

), the CaV1.2 phosphorylation site mutant S1928A and wild type AKAP79 (S1928A,  ), or to cells expressing wild type CaV1.2 and AKAP79 preincubated with the PKA inhibitor PKI (PKI,

), or to cells expressing wild type CaV1.2 and AKAP79 preincubated with the PKA inhibitor PKI (PKI,  ). Small dots reproduce the control condition shown in D as

). Small dots reproduce the control condition shown in D as  .

.

To test whether CaN anchoring to AKAP79 is important for regulation of CaV1.2 we applied stearated VIVIT extracellularly to acutely disrupt the AKAP79-CaN interaction. Perfusion of St-VIVIT increased current amplitude rapidly after FSK stimulation, but not in cells expressing 79ΔPIX-YFP, indicating that St-VIVIT specifically competes for binding to the PXIXIT-like motif of AKAP79 and that anchored CaN opposes enhancement by PKA of CaV1.2 current (Figure 3C,D; non-stearated VIVIT had a similar effect when included in the pipet solution, Figure S2). St-VIVIT had a small effect in the absence of FSK that likely reflects the effect of basal PKA activity on the channel after CaN anchoring is disrupted. St-VIVIT had no effect on FSK-stimulated cells when PKA binding to AKAP79 was disturbed (AKAP79pro2, which disrupts the helical structure of the PKA binding site; a similar result was also observed with wild type CaV1.2 and AKAP79 when Ht31 was included in the pipet, data not shown), or when cells were exposed to the PKA inhibitor PKI. Similar to St-Ht31, the effect of St-VIVIT also required an intact LZ interaction and the S1928 phosphorylation site (Figure 3E), suggesting that St-VIVIT application increases current amplitude by permitting unopposed PKA to phosphorylate the channel at S1928. Together with the results of St-Ht31 experiments, these findings suggest that AKAP79-anchored PKA and CaN together influence CaV1.2 activity in an opposing manner by controlling phosphorylation of CaV1.2.

Dynamic range of modulation by PKA and CaN

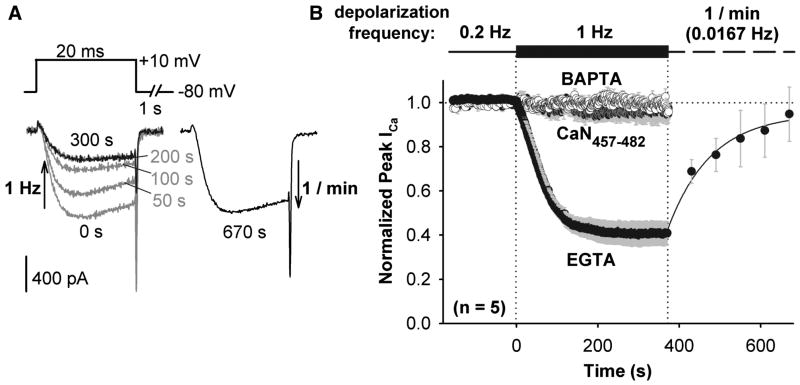

To evaluate the dynamic range of enhancement of CaV1.2 channels by PKA, Ca2+ current was first enhanced by persistent application of FSK, and enhancement was then reversed when CaN activity was stepped to a higher level of activity by increasing step depolarization frequency and hence local intracellular Ca2+. When depolarization frequency was increased from 0.2 Hz to 1 Hz, peak inward current amplitude dropped to ~40% of the level established at 0.2 Hz (Figure 4). Current amplitude recovered when the frequency of step depolarization was reduced to once per minute. The de-enhancement observed upon depolarization at 1 Hz was prevented by intracellular dialysis with the CaN autoinhibitory peptide (residues 457-482) or when EGTA in the internal recording solution was replaced with an equimolar amount of the faster Ca2+ chelator BAPTA. These latter two observations indicate that the decreased current amplitude that occurs with increased depolarization frequency is not caused by Ca2+-dependent inactivation. Our results indicate instead that, competing against persistent PKA activity, the degree of CaN-mediated channel de-enhancement is frequency dependent and CaN is positioned very close to the source of its activating Ca2+ (< 2 μm, Deisseroth et al., 1996; Marty and Neher, 1985).

Figure 4. Reversal by CaN of FSK enhancement of CaV1.2 current.

(A) Superimposed, selected currents elicited by a 1 Hz train of 20 ms step depolarizations (left), and current record after recovery of enhancement during a train of 20 ms depolarizations at 1/min (right). Currents recorded from HEK293 cells expressing CaV1.2-based channels and AKAP79-YFP, and bathed in FSK.

(B) Peak inward Ca2+ current amplitude in response to changes in step depolarization frequency. Pipet solution contained 10 mM EGTA, CaN autoinhibitory peptide + 10 mM EGTA, or 10 mM BAPTA. For the 10 mM EGTA data, recovery of current amplitude during 1/min depolarization was fit with a single exponential function (solid black curve). Time courses corrected for the rate of channel rundown at 0.2 Hz prior to 1 Hz stimulation. Error bars for all data points are plotted in gray.

When Ba2+ replaced extracellular Ca2+, increasing depolarization frequency from 0.2 Hz to 1 Hz still caused current amplitude to drop, although more slowly and to a lesser degree than in Ca2+ (Figure S3). As in Ca2+, the de-enhancement that was observed in Ba2+ was prevented by the CaN autoinhibitory peptide, indicating that Ba2+ is able to act as an agonist for CaM activation of CaN. Ba2+ and other divalent metal cations are capable of acting as weak agonists for several CaM-dependent processes (Artalejo et al., 1996; Gu and Cooper, 2000; Hardcastle et al., 1983; Proks and Ashcroft, 1995). In sharp contrast, Ba2+ is unable to substitute for Ca2+ in triggering Ca2+-dependent inactivation of voltage gated Ca2+ channels (Erickson et al., 2003; Tillotson, 1979; Zuhlke et al., 1999). Taken together with the observation that 10 mM BAPTA prevents current de-enhancement in Ca2+, the result that Ba2+ partially supports de-enhancement further indicates that channel de-enhancement in response to increased depolarization frequency is due to CaN dephosphorylation and not Ca2+-dependent inactivation, because the latter process is absent in Ba2+ but intact in BAPTA (Cens et al., 1999; Zuhlke et al., 1999).

In Ca2+, CaV1.2 modulation in HEK293 cells ranges from ~40% of the normalized, control Ca2+ current level obtained at 0.2 Hz depolarization and in FSK to ~130% of this control level, as revealed by St-VIVIT disruption of CaN anchoring and resulting enhancement of current under the same control stimulation conditions (0.2 Hz, FSK; Figure 3D). The dynamic range of modulation we have observed, >3-fold enhancement (from ~40% to ~130%) above our measured minimum, is much larger than has been described previously for the reconstituted HEK293 cell system, and approaches the range of L channel modulation found in cardiac myocytes.

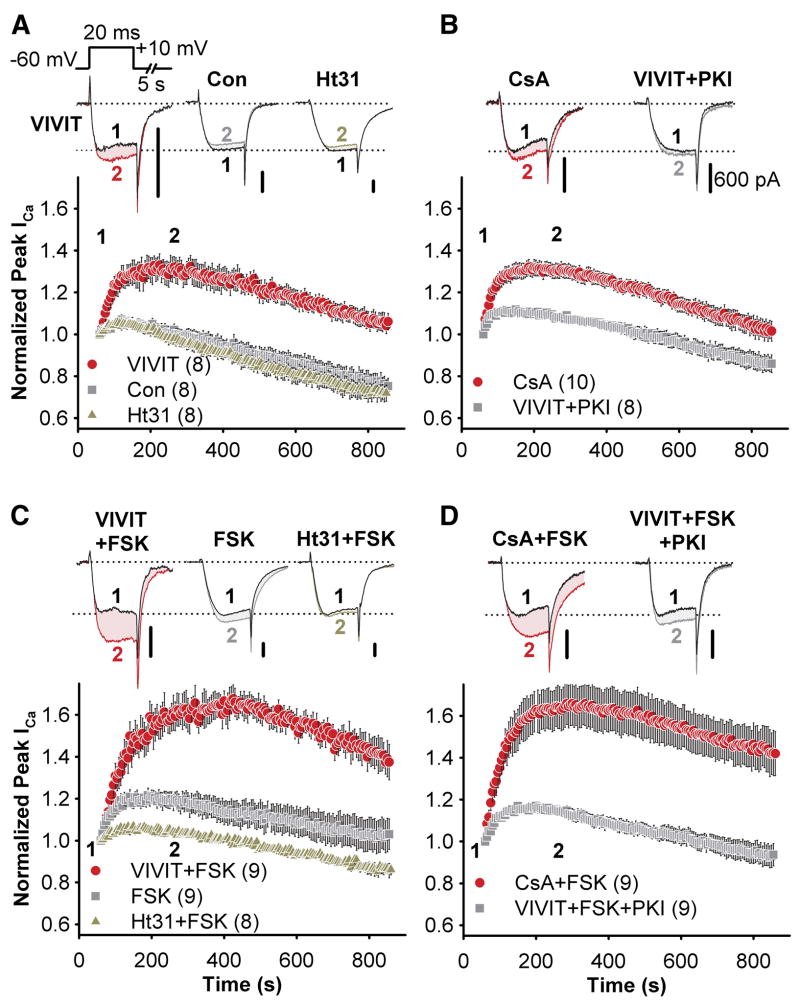

Anchored CaN opposes the effect of PKA on L-type current amplitude in hippocampal neurons

In hippocampal neurons, CaV1.2 has been shown to be important for memory and NMDA receptor-independent plasticity (Moosmang et al., 2005), and Ca2+ influx through L-type channels is enhanced by activation of β2-adrenergic receptors in dendritic spines of these neurons (Hoogland and Saggau, 2004). To test whether AKAP150 anchoring is important for local modulation of neuronal L-type channels, we examined pharmacologically isolated, voltage-clamped L-type Ca2+ current in mature cultured hippocampal neurons dialyzed intracellularly with 10 mM EGTA. Despite the difficulty of properly space-clamping L-type current in these extensively arborized neurons, plots of peak Ca2+ current exhibited highly reproducible responses to experimental manipulation of PKA and CaN.

In the absence of FSK, there was no difference between control time courses for L-type Ca2+ currents and those recorded with Ht31 in the patch pipet. However, intracellular dialysis of VIVIT resulted in an increase in current amplitudes without PKA stimulation (Figure 5A). This effect of VIVIT was blunted when PKI was simultaneously dialyzed into the cell, and CsA closely mimicked the effect of VIVIT (Figure 5B). When FSK was included in the pipet solution there was a small amount of current enhancement, which was prevented by Ht31, revealing an anchoring-dependent enhancement of L-type current by PKA (Figure 5C). However, the more prominent consequence of adding FSK to the pipet was that the effects of both VIVIT and CsA were substantially augmented (Figure 5C,D), suggesting that anchored CaN strongly opposes PKA phosphorylation of the channel even in the presence of elevated cAMP production. Additionally, simultaneous dialysis of PKI blunted the effect of VIVIT to the same extent in the presence of FSK as it had without FSK, indicating that while there may be a small amount of L-type channel phosphorylation by kinases other than PKA when CaN anchoring is disrupted, the effect of VIVIT on L-type currents is mainly the result of removing opposition to PKA activity.

Figure 5. Anchored PKA and CaN have opposing effects on L-type Ca2+ current in cultured hippocampal pyramidal neurons.

Peptides and other drugs were applied intracellularly via the patch pipet. Representative current recordings are shown for each time course as indicated; black records and colored records show currents 60 s (time point 1) and 250 s (time point 2) after establishing the whole cell recording configuration, respectively. All scale bars indicate 600 pA.

(A) Average peak current time course during dialysis of intracellular recording solution alone (Con,  ) or in the presence of either VIVIT (

) or in the presence of either VIVIT ( ) or Ht31 (

) or Ht31 ( ).

).

(B) The effect of CsA dialysis ( ) and co-application of VIVIT and PKI (

) and co-application of VIVIT and PKI ( ).

).

(C and D) as in A and B, but with FSK added to the intracellular recording solution.

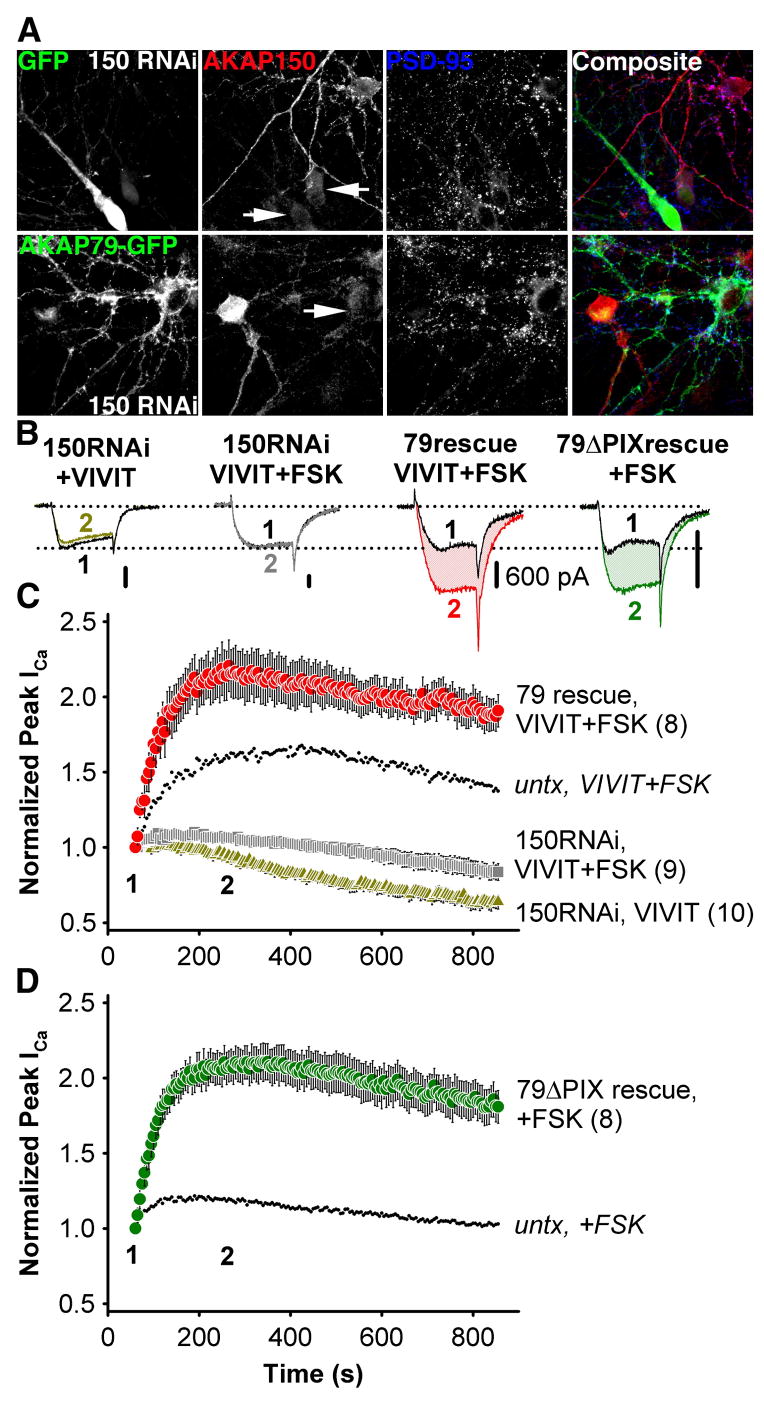

The effects of PKA and CaN on neuronal L-type channels are specific to AKAP79/150

Ht31 competes with all AKAPs for PKA binding, and VIVIT competes with any protein bearing a PXIXIT-like motif for CaN binding. To test whether the anchoring-dependent effects of PKA and CaN are specific to AKAP150 in hippocampal neurons we used an RNAi knockdown and rescue approach (Hoshi et al., 2005). We co-transfected neurons with GFP and a short hairpin construct that specifically interferes with expression of endogenous AKAP150 but not human AKAP79. Transfected neurons, marked by GFP expression, were reliably deficient in AKAP150 immunostaining when compared to untransfected neurons growing in the same cultures (Figure 6A, top). Co-expression of AKAP79-GFP with the AKAP150 RNAi construct was also successful, effectively resulting in replacement of the endogenous rat anchoring protein by the human form (Figure 6A, bottom).

Figure 6. The effect of VIVIT on neuronal L-type Ca2+ channels is specific to AKAP79/150.

(A) Top, micrographs of primary cultured hippocampal neurons transfected with the pSilencerAKAP150-short hairpin RNAi construct (150 RNAi) and GFP, demonstrating suppression (marked with GFP and arrows) of endogenous AKAP150 (red, indirectly immunolabeled with Texas Red). Bottom, simultaneous RNAi suppression of AKAP150 expression and rescue with AKAP79-GFP in hippocampal neurons. Normal levels of AKAP150 staining are seen in adjacent untransfected neurons. PSD-95 staining (blue, indirectly immunolabeled with Alexa Fluor 647) is a postsynaptic marker of excitatory synapses.

(B) Representative current recordings 60 s (time point 1, black traces) and 250 s (time point 2, colored traces) after establishing the whole cell recording configuration for 150RNAi + VIVIT, 150RNAi + VIVIT + FSK, 79rescue + VIVIT + FSK and 79ΔPIX + FSK conditions. All scale bars indicate 600 pA.

(C) Average peak current timecourse for cells expressing 150RNAi and GFP during VIVIT dialysis (150RNAi, VIVIT,  ) or co-application of VIVIT and FSK (150RNAi, VIVIT + FSK,

) or co-application of VIVIT and FSK (150RNAi, VIVIT + FSK,  ), and for cells rescued from AKAP150 knockdown by AKAP79-GFP co-transfection (79 rescue, VIVIT + FSK,

), and for cells rescued from AKAP150 knockdown by AKAP79-GFP co-transfection (79 rescue, VIVIT + FSK,  ). Small dots reproduce the effect of VIVIT + FSK observed in untransfected neurons (

). Small dots reproduce the effect of VIVIT + FSK observed in untransfected neurons ( from Fig. 4C).

from Fig. 4C).

(D) The effect of FSK alone on neurons after AKAP150 knockdown and replacement with AKAP79ΔPIX-YFP (79ΔPIX rescue, +FSK,  ). Small dots reproduce the effect of FSK in untransfected neurons (

). Small dots reproduce the effect of FSK in untransfected neurons ( from Figure 4C).

from Figure 4C).

When hippocampal pyramidal neurons were transfected with the AKAP150 RNAi construct, the effect of VIVIT on L-type current in untransfected cells was abolished whether or not FSK was included in the pipet (Figure 6B,C). FSK did cause a small enhancement of current that may represent the activity of PKA associated with other AKAPs or of non-anchored PKA. In contrast, co-transfection of AKAP79-GFP and the AKAP150 RNAi construct substantially enhanced the effect of VIVIT + FSK compared to untransfected cells. Co-transfection with the 79ΔPIX-GFP mutant increased the sensitivity of endogenous L-type channels to FSK, yielding a time course that closely resembles the time course of the effect of VIVIT + FSK in the AKAP79-GFP rescue condition (Figure 6B,D). These data indicate that the effects of PKA and CaN on L-type channels in hippocampal pyramidal neurons are specific to AKAP79/150 anchoring, and that CaN associates with and modulates neuronal L-type channels specifically through its association with the PXIXIT-like motif of AKAP79/150.

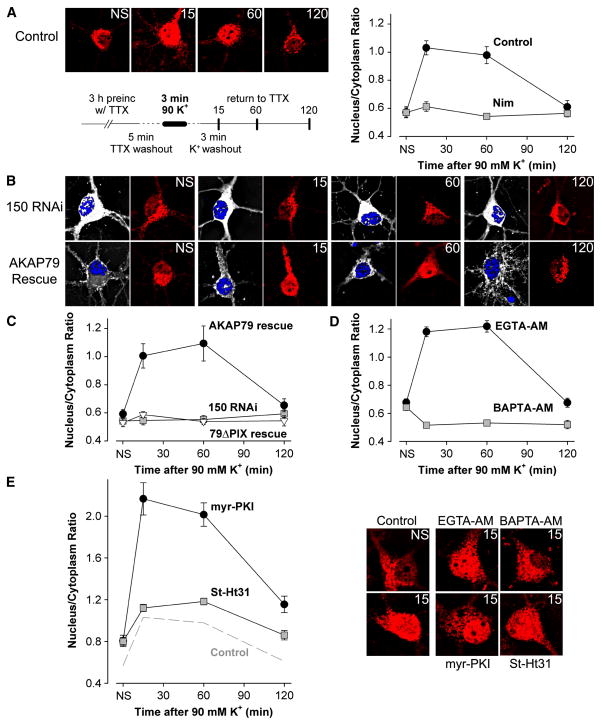

AKAP79/150 couples neuronal L-type channel activity to NFATc4 activation

In cultured hippocampal pyramidal neurons, Ca2+ entry specifically via L-type Ca2+ channels activates CaN, which in turn stimulates translocation to the nucleus of the transcription factor NFATc4 (Graef et al., 1999). Based on our findings that CaN is functionally associated with L-type channels in hippocampal neurons, we wondered whether AKA79/150 targeting of CaN is important in coupling L-type Ca2+ channel activity to NFATc4 activation. To test this hypothesis, we replicated a stimulation protocol that has been shown to activate L channel- and CaN-dependent nuclear translocation of NFATc4 and subsequent NFATc4-mediated gene expression. Following preincubation in TTX to silence spontaneous synaptic activity in the hippocampal cultures, we perfused neurons for 3 min in a solution containing high [K+] and then analyzed endogenous NFATc4 subcellular distribution by immunostaining at 15, 60 and 120 min after the high [K+]-depolarization. As shown previously, this stimulation increased nuclear NFATc4 staining within 15 min of high [K+] perfusion, the heightened level of nuclear NFATc4 persisted for ~60 min, and NFATc4 staining returned to the pre-stimulation level by 120 min (Figure 7A). NFATc4 translocation to the nucleus required L-type channel activity, as changes in NFATc4 distribution were not observed when the L channel blocker nimodipine was present during the stimulation protocol. Nor was nuclear translocation of NFATc4 observed in neurons transfected with an RNAi construct that knocked down expression of native AKAP150 (Figure 7B,C). NFATc4 translocation was rescued in AKAP150 knock-down neurons by co-transfection with AKAP79, the human homolog of AKAP150. Co-transfection with the AKAP79ΔPIX mutant failed to rescue NFATc4 translocation, despite this mutant’s ability to support PKA enhancement of CaV1.2 (Figure 6D) and its intact interaction with the channel (current density in Table S1, also unpublished observations showing intact FRET).

Figure 7. AKAP79/150 couples L-type Ca2+ channel activity to NFATc4 activation via targeting of CaN.

Following a 3 h preincubation in tetrodotoxin (TTX), primary cultured hippocampal neurons were stimulated by 3 min exposure to high (90 mM) K+ Tyrode’s solution and then fixed at the indicated time points (stimulation protocol schematized in the lower left of A). n = 20–30 cells for each point in averaged time courses.

(A) Left, deconvolved projection images collected at each time point (NS, not stimulated). NFATc4 distribution was determined by indirect immunofluorescence (Texas Red) and nuclei were stained with DAPI (images not shown). Right, average time course of NFATc4 nuclear translocation following application of high K+ solution for untreated cells (Con) and cells treated with the L channel antagonist nimodipine (Nim).

(B) Images of immunolabeled NFATc4 for cells transfected with 150 RNAi and GFP (150 RNAi) or with 150 RNAi and AKAP79-GFP (AKAP79 rescue). GFP (or AKAP79-GFP) expression (white) was used as a marker for cells transfected with the AKAP150 RNAi construct. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue).

(C) Time course of NFATc4 translocation for the 150 RNAi, AKAP79 rescue and 79ΔPIX rescue (150 RNAi and 79ΔPIX-YFP) conditions.

(D) Time course of NFATc4 translocation for cells loaded with either EGTA-AM or BAPTA-AM. Representative images shown below the time course plots.

(E) Time course of NFATc4 translocation for cells preincubated with myristoylated PKI (myr-PKI) or St-Ht31. Dashed line reproduces the time course for the control condition shown in A. Representative images shown to the right of the time course plots.

These findings support the hypothesis that neuronal activity is coupled to downstream activation of NFATc4 by AKAP79/150 targeting of CaN to L-type channels. This hypothesis predicts that nuclear translocation of NFATc4 depends upon activation of CaN by localized [Ca2+] increases near L channels. To test the prediction, we loaded neurons with equal concentrations of either the slow Ca2+ chelator EGTA or the faster Ca2+ chelator BAPTA. Consistent with the prediction and our finding that only EGTA-insensitive, short-range [Ca2+] signals trigger CaN control of channel activity in HEK293 cells and neurons, NFATc4 translocation in neurons was unaffected by EGTA but powerfully suppressed by BAPTA (Figure 7D). These results indicate that the pool of CaN and its Ca2+-sensitive activator, CaM, that are responsible for initiating NFATc4 signaling reside < 2 μm from the mouth of neuronal L-type channels (Deisseroth et al., 1996; Marty and Neher, 1985).

We considered the possibility that PKA anchored to L channels by AKAP79/150 might oppose activation of NFATc4 by CaN, because activation of PKA has been reported to phosphorylate NFATc4 and suppress its nuclear translocation in neurons (Belfield et al., 2006). We found that inhibition of PKA by myristoylated PKI greatly enhanced the response of NFATc4 to stimulation with high [K+] (Figure 7E). However, disruption by St-Ht31 of PKA anchoring to AKAP only modestly enhanced NFATc4 translocation relative to control, suggesting that although PKA opposes CaN activation of NFATc4, it is unanchored PKA that likely carries out this task.

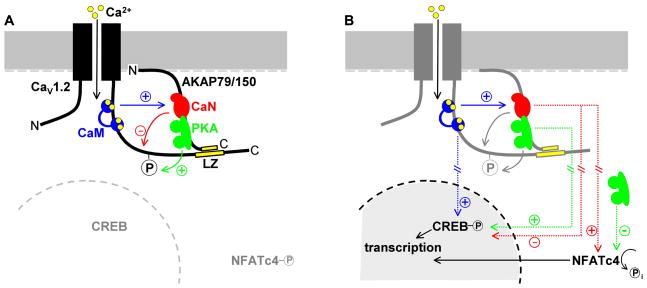

Discussion

CaV1.2 L-type Ca2+ channels can physically associate with either AKAP79/150 or AKAP15 through a modified leucine zipper interaction, but both the modulation of the channel and its downstream signaling depend upon the identity of the associated AKAP. Thus both of these AKAPs target PKA to the channel, but AKAP79/150 also targets CaN and thereby confers unique characteristics upon AKAP79/150-complexed L-type channels in neurons (Figure 8).

Figure 8. AKAP79/150 confers two distinct properties upon neuronal L-type Ca2+ channels.

(A) AKAP79/150-anchored CaN (red) strongly opposes L channel phosphorylation by PKA (green). Calmodulin (CaM, blue) binds directly to the proximal C-terminus of CaV1.2, where it mediates Ca2+-dependent inactivation of the channel (Cens et al., 1999; Erickson et al., 2003; Tillotson, 1979; Zuhlke et al., 1999). It is not known whether this CaM molecule, another CaM molecule associated with the channel or free CaM activates CaN in response to Ca2+ influx.

(B) AKAP79/150 targeting of CaN to L channels is necessary for NFATc4 activation. The known roles of CaM and PKA in nuclear signaling are also illustrated. CaM binding to the CaV1.2 C-terminus is critical for L channel-dependent activation of CREB (Dolmetsch et al., 2001), but the role of AKAP79/150 anchoring in PKA-dependent activation of CREB or CaN-dependent opposition to CREB phosphorylation has not been studied. Hash marks represent multiple steps and/or long distances involved in signaling pathways that affect transcription factor activation.

Anchored CaN is so effective that its action on L channels should not be thought of as only a reversal of PKA-mediated enhancement. Instead, CaN powerfully suppresses enhancement, even in the presence of elevated cAMP. The converse is true of Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors that are associated with AKAP79/150, where a clear effect of CaN is only revealed upon disruption of PKA anchoring or activity (Hoshi et al., 2005; Tavalin et al., 2002). The dominance of CaN in the L channel-AKAP79/150 complex may originate in the microenvironment near the intracellular mouth of the channel. In this location, CaN is advantageously placed to interact with its activator, Ca2+-CaM. CaV1.2 channels locally generate large increases in [Ca2+], and they also harbor a CaM molecule at an IQ motif near the modified leucine zipper that supports interaction with AKAP79/150 (Figure 8). This CaM has been shown to function as the Ca2+ sensor for L channel inactivation, facilitation and signaling to the nucleus (Dolmetsch et al., 2001; Erickson et al., 2003; Tillotson, 1979; Zuhlke et al., 1999). Because of its proximity and established role in L channel signaling, CaM docked at the IQ motif is an appealing candidate as an activator of anchored CaN, although alternatively, other channel-associated CaM molecules (Mori et al., 2004) may serve this function. Either way, the ability of CaM to activate calcineurin versus Ca2+-dependent inactivation shows pathway-specific sensitivity to Ba2+ and BAPTA (Figures 4 and S3): Ba2+ weakly mimics Ca2+ in activating CaN and 10 mM BAPTA completely suppresses activation of CaN, whereas Ba2+ is unable to trigger Ca2+-dependent inactivation of CaV1.2 and 10 mM BAPTA has no effect on inactivation.

Given the dominance of CaN when targeted to L-type Ca2+ channels, how is PKA ever able to succeed in influencing channel activity? We propose two possibilities. First, the results shown in Figure 4 suggest that CaN may be sensitive to the frequency of cellular excitation. CaN opposes PKA more strongly at higher excitation frequency, presumably because L channels are open more often, Ca2+ influx is increased and consequently CaN’s phosphatase activity is increased. Thus enhancement by PKA is likely favored when the channel is used less frequently. Second, during prolonged stimulation of CaN by Ca2+-CaM, oxidation of the CaN catalytic site inactivates the phosphatase (Bito et al., 1996; Wang et al., 1996), potentially allowing relief of CaN inhibition in response to long-lasting and/or high-frequency stimulation.

PKA enhances current amplitude by up to ~500% in cardiac myocytes (Bean et al., 1984), and our work has revealed enhancement in transfected HEK293 cells (up to ~325%, Figures 3 and 4) that approaches this level. The magnitude of L channel enhancement by PKA in neurons remains unclear, but our results with cultured hippocampal neurons—an underestimate of the extent of modulation because currents were normalized to the level 1 min after the onset of forskolin application—indicate a sizeable effect (~100%, Figure 6) that could have profound effects on neuronal Ca2+ signaling. If in fact maximum enhancement in neurons is limited to ~100%, however, what might prevent enhancement in neurons from reaching the higher levels seen in HEK293 cells and cardiac myocytes? One possibility is that, in neurons, AKAP79/150 associates with only some channels and this subpopulation of channels is subject to substantial enhancement. This idea may also explain results from our RNAi rescue experiments that neurons overexpressing AKAP79 or AKAP79ΔPIX exhibited an enhanced current response to PKA stimulation, as though overexpression increases the proportion of total channels that are associated with AKAP79/150 and thus regulated by PKA and CaN. Indeed, we have previously shown that overexpression of AKAP79 in these neurons recruits additional PKA to dendritic spines (Smith et al., 2006).

Forskolin stimulation of PKA had only a small effect on L currents in cultured hippocampal pyramidal neurons unless CaN anchoring or activity was disrupted. These neurons express several AKAPs besides AKAP79/150, none of which bind CaN, and at least two of which can associate with L channels (AKAP15 (Hulme et al., 2003) and MAP2B (Davare et al., 1999)). This requires some consideration. First, if a subset of L channels is complexed with AKAPs other than AKAP79/150, perhaps they rely upon a different phosphatase to suppress enhancement by PKA. The activity of such a phosphatase might explain how, in our experiments, PKA anchored to L channels by other AKAPs had little effect. A candidate for this role is protein phosphatase 2A, which has been reported to bind directly to the CaV1.2 C-terminus (Davare et al., 2000; Hall et al., 2006). Second, in L channel-AKAP complexes lacking a phosphatase, unopposed PKA may maintain channels in a maximally phosphorylated state and thereby occlude enhancement. Finally, our RNAi results suggest the possibility that AKAP79/150 is the primary AKAP associated with L-type channels in these neurons. Based on evidence that AKAP79/150 is the major AKAP in postsynaptic densities (Bauman et al., 2004) and that PKA enhances Ca2+ influx through L channels in dendritic spines (Hoogland and Saggau, 2004), we propose that AKAP79/150 is the sole AKAP responsible for cAMP-dependent modulation of L-type Ca2+ channels in spines of hippocampal pyramidal cells.

Ca2+ that enters through L-type channels is a potent activator of transcription factors that regulate neuronal gene expression. Activation of CREB by CaV1.2 requires CaM binding to the channel’s IQ motif where it acts as a sensitive calcium sensor (Bito et al., 1996; Deisseroth et al., 1996; Dolmetsch et al., 2001). Graef et al. (1999) demonstrated that L channels also specifically activate NFATc4-mediated transcription via CaN. Our results provide a molecular basis for this observation. Comparison of the action of BAPTA versus EGTA demonstrates that Ca2+ influx through L channels activates CaN, and subsequently NFATc4, in the vicinity of the channel. The experiments performed with RNAi knockdown and molecular replacement demonstrate that AKAP79/150 targeting of CaN is essential in linking L channels to NFATc4 translocation. Additionally, we have found that L channels and AKAP79/150 are associated physically and functionally in hippocampal pyramidal neurons and these partners are able to interact directly when heterologously expressed. We therefore conclude that AKAP79/150 promotes privileged signaling to NFATc4 by linking CaN directly to the channel. This is the first description of an effector of excitation-transcription coupling, CaN, being scaffolded to the channel and thereby positioned within range of its activating signal, Ca2+-CaM. As a single CaN molecule is unable to simultaneously bind the PXIXIT motifs of AKAP79 (KD ~1–5 μM) and NFATc4 (KD ~20 μM), and considering the dynamic nature of protein-protein interactions, when locally activated CaN unbinds from the AKAP it can presumably bind NFATc4. Intriguingly, CaM and CaN each have dual roles in neuronal L channel signaling: regulation of, and response to, Ca2+ influx. Our findings thus support an emerging view of neuronal L-type Ca2+ channels as a nexus for nuclear signaling mediated by intimate interactions with key signaling molecules.

Experimental Procedures

Cell culture and transfections

HEK293 were transfected with equimolar ratios of cDNAs encoding CaV1.2 channel subunits (α11.2a, β2b, α2δ1a) and other proteins, including AKAP79, using the Effectene transfection reagent (Qiagen). COS7 cells were transfected by calcium phosphate precipitation. Cells were plated onto glass coverslips and studied 1–3 days after transfection.

Preparation and transfection of primary hippocampal neurons

Primary hippocampal neurons were prepared from Sprague Dawley neonatal rats (P0–2) as described (Gomez et al., 2002; Smith et al., 2006). For imaging and electrophysiological recording, neurons were plated at low density (30–50,000 cells/ml) and grown 12–17 days in vitro (DIV). For IPs, neurons were plated at high density (500–750,000 cells/ml) and grown 12–17 DIV. For AMAXA-nucleofector transfection, P0-2 neurons were resuspended at 250–500,000 cells/transfection, electroporated with 4-6 μg of each cDNA and/or the150 RNAi construct, plated at medium density and grown to 12–17 DIV.

Immunoprecipitation

Extracts of cultured hippocampal neurons or transfected HEK293 cells were solubilized in 1.0% Triton X-100 (Gomez et al., 2002; Gorski et al., 2005) and incubated overnight at 4°C with 10 μg anti-AKAP150, anti-GFP (Molecular Probes), anti-myc (Santa Cruz) or anti-CaV1.2 CT4 antibodies. IPs were analyzed by immunoblotting for AKAP150 (1:2000), AKAP79 (1:1000), CaV1.2 (anti-CT4, 1:1000) CFP-tagged AKAP79 (anti-GFP, 1:500, Santa Cruz) or myc-tagged CaN A (anti-myc 9E10, 1:1000, Santa Cruz). Chemiluminescence was detected using an Alpha-Inotech imager.

FRET imaging

These methods and equipment have been described previously (Oliveria et al., 2003), but are described more thoroughly in Supplemental Experimental Procedures. Eeff calculations are adapted from Erickson et al. (2003).

Patch clamp recording

Borosilicate patch pipets were heat-polished to a resistance in the bath of 2–8 MΩ. Voltage-clamped currents were measured with an Axopatch 1D amplifier (Axon Instruments), filtered at 2 kHz and sampled at 10 kHz. Series resistance compensation, capacitance cancellation and leak subtraction (−P/4 protocol) were employed. For HEK293 cells, the whole-cell pipet contained (in mM): 135 CsCl, 10 EGTA or BAPTA, 10 HEPES, 4 MgATP, and pH adjusted to 7.5 with TEA-OH. The bath solution contained (in mM): 125 NaCl, 15 CaCl2 or 15 BaCl2, 10 HEPES, 20 sucrose, and pH adjusted to 7.3 with TEA-OH. Ca2+ currents were evoked by 20 ms depolarization from a holding potential of −80 mV to +10 mV every 5 s unless otherwise indicated. Current amplitudes were normalized to the steady level marked as time = 0 s, which was typically achieved 3–5 minutes after break-in for HEK293 cells. Positive transfectants were identified by AKAP79-YFP fluorescence. St-Ht31 (10 μM) and St-VIVIT (10 μM) were applied via rapid bath perfusion (Warner Instruments). Where indicated, FSK (5 μM), CsA (5 μM), PKI (5 μM) or CaN457-482 (100 μM) were included in the pipet solution. For cultured hippocampal pyramidal neurons, the whole-cell pipet contained (in mM): 120 CsMeSO4, 30 TEA-Cl, 10 EGTA, 5 MgCl2, 5 Na2ATP and 10 HEPES (pH 7.2). Neurons were superfused with (in mM): 125 NaCl, 10 CaCl2, 5.85 KCl, 22.5 TEA-Cl, 1.2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES(Na), 11 D-glucose (pH 7.4), as well as tetrodotoxin (TTX, 1 μM) to block Na+ currents. To isolate L-type currents, N- and P/Q-type Ca2+ channel currents were blocked by preincubating neurons in extracellular recording solution supplemented with ω-conotoxins (ω-CTx) GVIA (1 μM) and MVIIC (5 μM) for30 min before recording (Tavalin et al., 2004). Neurons were used for <1 hr after preincubation to minimize contamination from N- and P/Q-type currents as these channels became progressively unblocked (τoff ~200 min for ω-CTx-MVIIC unbinding from P/Q-type channels (Sather et al., 1993); ω-CTx-GVIA binding to N-type channels is even more prolonged (McCleskey et al., 1987)). A holding potential of −60 mV was chosen to inactivate >80% of R-type channels (Sochivko et al., 2003), which comprise 17–35% of the total calcium current in hippocampal neurons (McDonough et al., 1996; Sochivko et al., 2003). Transfected neurons were identified by GFP or AKAP79-GFP fluorescence. Where indicated, FSK (5 μM), CsA (5 μM), PKI (5 μM), Ht31 (10 μM) and VIVIT (10 μM) were included in the pipet solution. For neurons, currents were normalized to the level achieved at 1 min after break-in. Only neurons with an access resistance <10 MΩ were studied.

Cyclosporin A, forskolin and PKI were obtained from Sigma; ω-CTx-GVIA, ω-CTx-MVIIC and myr-PKI were obtained from EMD Biosciences; CaN457-482 was obtained from Biomol; St -Ht31 and St-Ht31pro were obtained from Promega; and St-VIVIT was synthesized by Sigma-Genosys.

Immunocytochemistry and quantitative digital image analysis

Hippocampal neurons and COS7 cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100, as previously described (Gomez et al., 2002). Labeling was performed with rabbit polyclonal antibodies against AKAP150 (1:500) and NFATc4 (H-74, 1:100, Santa Cruz (Groth and Mermelstein, 2003) and a monoclonal antibody against PSD95 (1:100, ABR). Secondary antibodies conjugated to Texas Red (1:500) or Alexa Fluor 647 (1:500) were obtained from Molecular Probes. Digital deconvolution imaging of stained cells was carried out and analyzed with Slidebook 4.0 software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations) and the same microscopy system as in the FRET experiments.

NFATc4 translocation assay

Prior to stimulation, coverslips bearing cultured hippocampal neurons were incubated for 3 h at 37°C in Tyrode’s solution containing (in mM): 135 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 25 HEPES, 10 glucose and 0.1% BSA, pH 7.4, and 1 μM TTX (Sigma). Coverslips were stimulated at room temperature with high [K+] (90 mM) and then returned to Tyrode’s +TTX and incubated at 37°C until fixation at the indicated time points. In experiments using pharmacological manipulations, nimodipine (5 μM), myr-PKI (5 μM) or St-Ht31 (10 μM) was applied for 15 min before high [K+] stimulation and was also included throughout the remainder of the protocol. In the EGTA-AM and BAPTA-AM experiments, after 1 h of preincubation in Tyrode’s +TTX, the bathing solution was exchanged for one containing 100 μM of either membrane-permeant chelator in addition to TTX. After 1 h loading chelator, neurons were returned to Tyrode’s +TTX and allowed to recover in this solution for 1 h prior to stimulation with high [K+]. To measure NFATc4 immunofluorescence intensity in a neuron, a z-series (0.2 μm steps) of images was collected from each cell. The z-series images were digitally deconvolved and then used to construct two-dimensional, summed-intensity projection images representing the integrated intensity profile for each cell. Quantitative mask analysis of these projection images was performed using Slidebook to obtain mean immunofluorescence intensities in the nucleus and in the cytoplasm of the neuronal soma.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the student’s t-test. All error bars indicate standard error of measurement.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The CT4 antibody was provided by Marlene Hosey (Northwestern University). VIVIT-GFP and the VIVIT peptide were provided by Patrick Hogan (Harvard University). The pSilencer-sh150RNAi construct was provided by John Scott (Oregon Health Sciences University). We thank Joshua Ohrtman, Emily Gibson and Jessica Gorski for technical assistance. This work was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (NS051963 to S.F.O., NS40701 to M.L.D., NS35245 to W.A.S.) and the Sie Foundation (M.L.D.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aramburu J, Yaffe MB, Lopez-Rodriguez C, Cantley LC, Hogan G, Rao A. Affinity-driven peptide selection of an NFAT inhibitor more selective than cyclosporin A. Science. 1999;285:2129–2133. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5436.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artalejo CR, Elhamdani A, Palfrey HC. Calmodulin is the divalent cation receptor for rapid endocytosis, but not exocytosis, in adrenal chromaffin cells. Neuron. 1996;16:195–205. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bading H, Ginty DD, Greenberg ME. Regulation of gene expression in hippocampal neurons by distinct calcium signaling pathways. Science. 1993;260:181–186. doi: 10.1126/science.8097060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman AL, Goehring AS, Scott JD. Orchestration of synaptic plasticity through AKAP signaling complexes. Neuropharmacology. 2004;46:299–310. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2003.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean BP, Nowycky MC, Tsien RW. β-adrenergic modulation of calcium channels in frog ventricular heart cells. Nature. 1984;307:371–375. doi: 10.1038/307371a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belfield JL, Whittaker C, Cader MZ, Chawla S. Differential effects of Ca2+ and cAMP on transcription mediated by MEF2D and cAMP-response element-binding protein in hippocampal neurons. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:27724–27732. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601485200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bito H, Deisseroth K, Tsien RW. CREB phosphorylation and dephosphorylation: a Ca2+- and stimulus duration-dependent switch for hippocampal gene expression. Cell. 1996;87:1203–1214. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81816-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunemann M, Gerhardstein BL, Gao T, Hosey MM. Functional regulation of L-type calcium channels via protein kinase A-mediated phosphorylation of the β2 subunit. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:33851–33854. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.33851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr DW, Hausken ZE, Fraser ID, Stofko-Hahn RE, Scott JD. Association of the type II cAMP-dependent protein kinase with a human thyroid RII-anchoring protein. Cloning and characterization of the RII-binding domain. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:13376–13382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA. Structure and regulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2000;16:521–555. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cens T, Restituito S, Galas S, Charnet P. Voltage and calcium use the same molecular determinants to inactivate calcium channels. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:5483–5490. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark NC, Nagano N, Kuenzi FM, Jarolimek W, Huber I, Walter D, Wietzorrek G, Boyce S, Kullmann DM, Striessnig J, Seabrook GR. Neurological phenotype and synaptic function in mice lacking the CaV1.3 α subunit of neuronal L-type voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels. Neuroscience. 2003;120:435–442. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00329-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colledge M, Dean RA, Scott GK, Langeberg LK, Huganir RL, Scott JD. Targeting of PKA to glutamate receptors through a MAGUK-AKAP complex. Neuron. 2000;27:107–119. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davare MA, Avdonin V, Hall DD, Peden EM, Burette A, Weinberg RJ, Horne MC, Hoshi T, Hell JW. A β2 adrenergic receptor signaling complex assembled with the Ca2+ channel CaV1.2. Science. 2001;293:98–101. doi: 10.1126/science.293.5527.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davare MA, Dong F, Rubin CS, Hell JW. The A-kinase anchor protein MAP2B and cAMP-dependent protein kinase are associated with class C L-type calcium channels in neurons. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:30280–30287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.42.30280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davare MA, Horne MC, Hell JW. Protein phosphatase 2A is associated with class C L-type calcium channels (CaV1.2) and antagonizes channel phosphorylation by cAMP-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:39710–39717. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005462200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deisseroth K, Bito H, Tsien RW. Signaling from synapse to nucleus: postsynaptic CREB phosphorylation during multiple forms of hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 1996;16:89–101. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Acqua ML, Dodge KL, Tavalin SJ, Scott JD. Mapping the protein phosphatase-2B anchoring site on AKAP79. Binding and inhibition of phosphatase activity are mediated by residues 315-360. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:48796–48802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207833200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolmetsch RE, Pajvani U, Fife K, Spotts JM, Greenberg ME. Signaling to the nucleus by an L-type calcium channel-calmodulin complex through the MAP kinase pathway. Science. 2001;294:333–339. doi: 10.1126/science.1063395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson MG, Liang H, Mori MX, Yue DT. FRET two-hybrid mapping reveals function and location of L-type Ca2+ channel CaM preassociation. Neuron. 2003;39:97–107. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00395-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan AN, Maack C, Johns DC, Sidor A, O’Rourke B. β-adrenergic stimulation of L-type Ca2+ channels in cardiac myocytes requires the distal carboxyl terminus of α1C but not serine 1928. Circ Res. 2006;98:e11–e18. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000202692.23001.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao T, Cuadra AE, Ma H, Bunemann M, Gerhardstein BL, Cheng T, Eick RT, Hosey MM. C-terminal fragments of the α1C (CaV1.2) subunit associate with and regulate L-type calcium channels containing C-terminal-truncated α1C subunits. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:21089–21097. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008000200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao T, Yatani A, Dell’Acqua ML, Sako H, Green SA, Dascal N, Scott JD, Hosey MM. cAMP-dependent regulation of cardiac L-type Ca2+ channels requires membrane targeting of PKA and phosphorylation of channel subunits. Neuron. 1997;19:185–196. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80358-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez LL, Alam S, Smith KE, Horne E, Dell’Acqua ML. Regulation of A-kinase anchoring protein 79/150-cAMP-dependent protein kinase postsynaptic targeting by NMDA receptor activation of calcineurin and remodeling of dendritic actin. J Neurosci. 2002;22:7027–7044. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-16-07027.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon GW, Berry G, Liang XH, Levine B, Herman B. Quantitative fluorescence resonance energy transfer measurements using fluorescence microscopy. Biophys J. 1998;74:2702–2713. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77976-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorski JA, Gomez LL, Scott JD, Dell’Acqua ML. Association of an A-kinase-anchoring protein signaling scaffold with cadherin adhesion molecules in neurons and epithelial cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:3574–3590. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-02-0134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graef IA, Mermelstein PG, Stankunas K, Neilson JR, Deisseroth K, Tsien RW, Crabtree GR. L-type calcium channels and GSK-3 regulate the activity of NF-ATc4 in hippocampal neurons. Nature. 1999;401:703–708. doi: 10.1038/44378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray R, Johnston D. Noradrenaline and β-adrenoceptor agonists increase activity of voltage-dependent calcium channels in hippocampal neurons. Nature. 1987;327:620–622. doi: 10.1038/327620a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groth RD, Mermelstein PG. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor activation of NFAT (nuclear factor of activated T-cells)-dependent transcription: a role for the transcription factor NFATc4 in neurotrophin-mediated gene expression. J Neurosci. 2003;23:8125–8134. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-22-08125.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover LM, Teyler TJ. Two components of long-term potentiation induced by different patterns of afferent activation. Nature. 1990;347:477–479. doi: 10.1038/347477a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu C, Cooper DM. Ca2+, Sr2+, and Ba2+ identify distinct regulatory sites on adenylyl cyclase (AC) types VI and VIII and consolidate the apposition of capacitative cation entry channels and Ca2+-sensitive ACs. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:6980–6986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.10.6980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall DD, Feekes JA, rachchige Don AS, Shi M, Hamid J, Chen L, Strack S, Zamponi GW, Horne MC, Hell JW. Binding of protein phosphatase 2A to the L-type calcium channel CaV1.2 next to Ser1928, its main PKA site, is critical for Ser1928 dephosphorylation. Biochemistry. 2006;45:3448–3459. doi: 10.1021/bi051593z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardcastle J, Hardcastle PT, Noble JM. The effect of barium chloride on intestinal secretion in the rat. J Physiol. 1983;344:69–80. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hell JW, Westenbroek RE, Warner C, Ahlijanian MK, Prystay W, Gilbert MM, Snutch TP, Catterall WA. Identification and differential subcellular localization of the neuronal class C and class D L-type calcium channel α1 subunits. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:949–962. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.4.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogland TM, Saggau P. Facilitation of L-type Ca2+ channels in dendritic spines by activation of β2 adrenergic receptors. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8416–8427. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1677-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshi N, Langeberg LK, Scott JD. Distinct enzyme combinations in AKAP signalling complexes permit functional diversity. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:1066–1073. doi: 10.1038/ncb1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulme JT, Ahn M, Hauschka SD, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. A novel leucine zipper targets AKAP15 and cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase to the C terminus of the skeletal muscle Ca2+ channel and modulates its function. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:4079–4087. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109814200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulme JT, Lin TW, Westenbroek RE, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. β-adrenergic regulation requires direct anchoring of PKA to cardiac CaV1.2 channels via a leucine zipper interaction with A kinase-anchoring protein 15. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13093–13098. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2135335100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impey S, Mark M, Villacres EC, Poser S, Chavkin C, Storm DR. Induction of CRE-mediated gene expression by stimuli that generate long-lasting LTP in area CA1 of the hippocampus. Neuron. 1996;16:973–982. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80120-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavalali ET, Hwang KS, Plummer MR. cAMP-dependent enhancement of dihydropyridine-sensitive calcium channel availability in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5334–5348. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-14-05334.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klauck TM, Faux MC, Labudda K, Langeberg LK, Jaken S, Scott JD. Coordination of three signaling enzymes by AKAP79, a mammalian scaffold protein. Science. 1996;271:1589–1592. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5255.1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Rao A, Hogan PG. Structural delineation of the calcineurin-NFAT interaction and its parallels to PP1 targeting interactions. J Mol Biol. 2004;342:1659–1674. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.07.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marty A, Neher E. Potassium channels in cultured bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. J Physiol. 1985;367:117–41. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015817. 117–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCleskey EW, Fox AP, Feldman DH, Cruz LJ, Olivera BM, Tsien RW, Yoshikami D. ω-Conotoxin: direct and persistent blockade of specific types of calcium channels in neurons but not muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:4327–4331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.12.4327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonough SI, Swartz KJ, Mintz IM, Boland LM, Bean BP. Inhibition of calcium channels in rat central and peripheral neurons by ω-conotoxin MVIIC. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2612–2623. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-08-02612.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mermelstein PG, Bito H, Deisseroth K, Tsien RW. Critical dependence of cAMP response element-binding protein phosphorylation on L-type calcium channels supports a selective response to EPSPs in preference to action potentials. J Neurosci. 2000;20:266–273. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-01-00266.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintz IM, Adams ME, Bean BP. P-type calcium channels in rat central and peripheral neurons. Neuron. 1992;9:85–95. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90223-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moosmang S, Haider N, Klugbauer N, Adelsberger H, Langwieser N, Muller J, Stiess M, Marais E, Schulla V, Lacinova L, Goebbels S, Nave KA, Storm DR, Hofmann F, Kleppisch T. Role of hippocampal CaV1.2 Ca2+ channels in NMDA receptor-independent synaptic plasticity and spatial memory. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9883–9892. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1531-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori MX, Erickson MG, Yue DT. Functional stoichiometry and local enrichment of calmodulin interacting with Ca2+ channels. Science. 2004;304:432–435. doi: 10.1126/science.1093490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy TH, Worley PF, Baraban JM. L-type voltage-sensitive calcium channels mediate synaptic activation of immediate early genes. Neuron. 1991;7:625–635. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90375-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveria SF, Gomez LL, Dell’Acqua ML. Imaging kinase--AKAP79--phosphatase scaffold complexes at the plasma membrane in living cells using FRET microscopy. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:101–112. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200209127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proks P, Ashcroft FM. Effects of divalent cations on exocytosis and endocytosis from single mouse pancreatic beta-cells. J Physiol. 1995;487:465–77. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter H. The dependence of slow inward current in Purkinje fibres on the extracellular calcium-concentration. J Physiol. 1967;192:479–492. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1967.sp008310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sather WA, Tanabe T, Zhang JF, Mori Y, Adams ME, Tsien RW. Distinctive biophysical and pharmacological properties of class A (BI) calcium channel α1 subunits. Neuron. 1993;11:291–303. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90185-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KE, Gibson ES, Dell’Acqua ML. cAMP-dependent protein kinase postsynaptic localization regulated by NMDA receptor activation through translocation of an A-kinase anchoring protein scaffold protein. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2391–2402. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3092-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder EM, Colledge M, Crozier RA, Chen WS, Scott JD, Bear MF. Role for A kinase-anchoring proteins (AKAPS) in glutamate receptor trafficking and long term synaptic depression. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:16962–16968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409693200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sochivko D, Chen J, Becker A, Beck H. Blocker-resistant Ca2+ currents in rat CA1 hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Neuroscience. 2003;116:629–638. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00777-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavalin SJ, Colledge M, Hell JW, Langeberg LK, Huganir RL, Scott JD. Regulation of GluR1 by the A-kinase anchoring protein 79 (AKAP79) signaling complex shares properties with long-term depression. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3044–3051. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-08-03044.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavalin SJ, Shepherd D, Cloues RK, Bowden SE, Marrion NV. Modulation of single channels underlying hippocampal L-type current enhancement by agonists depends on the permeant ion. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:824–837. doi: 10.1152/jn.00700.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillotson D. Inactivation of Ca conductance dependent on entry of Ca ions in molluscan neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;77:1497–1500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.3.1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien RW, Giles W, Greengard P. Cyclic AMP mediates the effects of adrenaline on cardiac purkinje fibres. Nat New Biol. 1972;240:181–183. doi: 10.1038/newbio240181a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Culotta VC, Klee CB. Superoxide dismutase protects calcineurin from inactivation. Nature. 1996;383:434–437. doi: 10.1038/383434a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue DT, Herzig S, Marban E. β-adrenergic stimulation of calcium channels occurs by potentiation of high-activity gating modes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:753–757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.2.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuhlke RD, Pitt GS, Deisseroth K, Tsien RW, Reuter H. Calmodulin supports both inactivation and facilitation of L-type calcium channels. Nature. 1999;399:159–162. doi: 10.1038/20200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.