Abstract

PURPOSE

To examine early postoperative wound healing in rabbit corneas that had LASIK flaps formed with three different models (15 KHz, 30 KhZ, and 60 KHz) of a femtosecond laser compared with flaps formed with a microkeratome.

METHODS

Thirty-nine rabbit eyes were randomized to receive either no surgery or corneal flaps formed with one of the lasers or the microkeratome. Sixteen eyes also had lamellar cuts with no side cuts with the 30 KHz laser. Animals were sacrificed and corneas processed as frozen sections or fixed for transmission electron microscopy. Frozen sections were evaluated with the TUNEL assay to detect apoptosis, immunocytochemistry for Ki67 to detect cell mitosis, and immunocytochemistry for CD11b to detect mononuclear cells.

RESULTS

Rabbit corneas that had flaps formed with the 15 KHz laser had significantly more stromal cell death, greater stromal cell proliferation, and greater monocyte influx in the central and peripheral cornea at 24 hours after surgery than corneas that had flaps formed with the 30 KHz or 60 KHz laser or the microkeratome. Results of the 60 KHz laser and microkeratome were not significantly different for any of the parameters at 24 hours, except for mitotic stromal cells at the flap margin. Transmission electron microscopy revealed that the primary mode of stromal cell death at 24 hours after laser ablation was necrosis.

CONCLUSIONS

Stromal cell necrosis associated with femtosecond laser flap formation likely contributes to greater inflammation after LASIK performed with the femtosecond laser, especially with higher energy levels that result in greater keratocyte cell death.

The femtosecond solid-state laser used to make LASIK flaps has had an increasing role in refractive and corneal surgery.1 This laser uses thousands of ultra-short (approximately 600 femtosecond) pulses of focused near-infrared light (1053 nm) to create microcavitations that separate the corneal tissue. A high peak power leads to shock waves and intrastromal cavitation bubbles that coalesce and disappear after a few minutes. It delivers closely spaced, 3-micron spots that can be focused to a preset depth to produce photodisruption of stromal tissue. An intrastromal cleavage plane is created with adjustable diameter, depth, edge angle, hinge width, and hinge location.

Several potential advantages of using the femtosecond laser rather than the microkeratome for LASIK flap creation have been touted, including added safety, improved flap uniformity, and better predictability of the flap thickness, along with reduced complications such as buttonhole flaps, free caps, partial flaps, and epithelial defects.1-4 In the early experience of the authors with the commercially available IntraLase (Irvine, Calif) 15 KHz Model II femtosecond laser, however, we noted a markedly greater tendency toward early postoperative inflammation in the cornea—in some cases manifest as central diffuse lamellar keratitis—and a much more prominent scar at that flap edge compared with eyes treated with the microkeratome (S. E. Wilson, MD, and M. V. Netto, MD, unpublished data, 2005), suggesting an augmented corneal wound healing response with the femtosecond laser.

We initiated corneal wound healing studies in rabbits comparing the 15 KHz Model II femtosecond laser and the Hansatome microkeratome (Bausch & Lomb, Rochester, NY) to explore the corneal pathophysiology underlying these clinical differences. Subsequently, after completion of these laboratory studies, the femtosecond laser used at our facility was exchanged sequentially for the IntraLase 30 KHz and 60 KHz Model II femtosecond lasers, which incorporated several design changes that allowed lower laser energy levels to be used for both the lamellar and side cuts. Therefore, we included the 30 KHz and 60 KHz lasers in these studies. The results from these experiments are presented.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

The Animal Control Committee at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation approved all animal studies described in this article. All animals were treated in accordance with the tenets of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. Anesthesia was obtained by intramuscular injection of ketamine hydrochloride (30 mg/kg) and xylazine hydrochloride (5 mg/kg). In addition, topical proparacaine hydrochloride 1% (Alcon Laboratories Inc, Ft Worth, Tex) was applied to each eye just prior to surgery. Euthanasia was performed using an intravenous injection of 100 mg/kg pentobarbital while the animal was under general anesthesia.

Study Design and Femtosecond Laser and Microkeratome Parameters

Thirty-nine 12- to 15-week-old female New Zealand white rabbits weighing 2.5 to 3.0 kg each were included in this study. One eye of each rabbit was selected at random for surgery or control. The animals undergoing surgery were divided into several groups. Ten eyes had flaps produced with the microkeratome (160-μm plate, 9.0-mm diameter), 8 eyes had flaps produced with the 15 KHz Model II femtosecond laser (110-μm thickness, 9.0-mm diameter, 2.5-μJ raster energy, 2.7-μJ side-cut energy, 9-μm pulse spacing), 10 eyes had flaps performed with the 30 KHz Model II femtosecond laser (110-μm thickness, 9.0-mm diameter, 0.9-μJ raster energy, 0.9-μJ side-cut energy, 8-μm pulse spacing), and 5 eyes had flaps performed with the 60 KHz Model II femtosecond laser (110-μm thickness, 9.0-mm diameter, 1.1-μJ raster energy, 1.1-μJ side-cut energy, 8-μm pulse spacing), using previously described methods.5 Six control eyes from animals that had no surgery were also included.

All flaps were lifted and the beds irrigated with balanced salt solution before the flaps were returned to their original position. A bandage contact lens was placed over the eye (Soflens 66, F/M base curve; Bausch & Lomb) and the eyelids closed with a temporary tarsorrhaphy placed with a 5-0 suture. Four eyes in each the microkeratome and 15 KHz laser groups and 6 eyes in the 30 KHz laser group were treated with 1% prednisolone acetate every 6 hours beginning at the end of surgery. The animals were sacrificed 24 hours after surgery and the corneoscleral rims collected for cryofixation.

The 30 KHz and 60 KHz lasers differed from the 15 KHz laser in several features, including overall laser and optics integration design, pattern of laser pulse application, and the rate of application per second in pulses (30,000 pulses/second or 60,000 pulses/second vs 15,000 pulses/second, respectively). These changes allowed flaps to be formed with lower raster stromal energies and side-cut energies with the 30 KHz and 60 KHz lasers than with the 15 KHz laser. The energies used in this study with each laser were those recommended by the manufacturer at the time the laser was installed, with the experiments beginning shortly thereafter in each case. The manufacturer reports a measured spot size of approximately 2 microns for all three femtosecond laser models.

The laser systems were used for the experimental studies following standard installation and maintenance provided by the manufacturer for human clinical use. According to the manufacturer, the laser beam for each femtosecond laser system used is approximately Gausssian with negligible truncation by the lens aperture. The optical components of the delivery system for each laser underwent interferometric measurements ensuring nearly diffraction limited focusing prior to use.

The pulse energy was measured and controlled internally by each laser. The internal energy meter was calibrated by the manufacturer.

Femtosecond Laser Treatment for Analysis of Mode of Stromal Cell Death

One cornea in 16 additional rabbits also underwent stromal ablation without a side cut with the 30 KHz laser so that the effect of the intrastromal cut alone on stromal cell death could be analyzed. None of these eyes were treated with corticosteroids. The animals were sacrificed and corneas removed at three time points—15 minutes (4 corneas), 30 minutes (4 corneas), and 24 hours (8 corneas)—after laser ablation. These corneas were fixed for electron microscopy or terminal deoxyribonucleotidyl transferase–mediated dUTP-digoxigenin nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay.

Tissue Fixation and Sectioning for the TUNEL Assay and Immunocytochemistry

Corneoscleral rims of eyes with flaps and control eyes were embedded in liquid OCT compound (Tissue-Tek; Sakura Finetek, Torrance, Calif) within a 24 × 24 × 5 mm mold (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, Pa). The tissue specimens were centered within the mold so the block could be bisected and transverse sections cut from the center of the cornea. The mold and tissue were rapidly frozen in 2-methyl butane within a stainless steel crucible suspended in liquid nitrogen. The frozen tissue blocks were stored at −85°C until sectioning was performed.

Central corneal sections (7 μm thick) were cut using a cryostat (HM 505M; Micron GmbH, Walldorf, Germany). Sections were placed on microscope slides (Superfrost Plus; Fisher Scientific) and maintained at −85°C until staining was performed.

TUNEL Assays and Immunocytochemistry Assays

To detect fragmentation of DNA associated with cell death, tissue sections were fixed in acetone at −20°C for 2 minutes, dried at room temperature for 5 minutes, and then placed in balanced salt solution. A fluorescence-based TUNEL assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (ApopTag, Cat No. S7165; Intergen Co, Purchase, NY). The TUNEL assay detects the ends of fragments of DNA formed during the apoptosis process. Positive control (4 hours after mechanical corneal epithelial scrape) and negative control (unwounded) cornea slides were included in each assay. Photographs were obtained with a Nikon E800 fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY).

The monoclonal antibody for either Ki67 (Zymed Laboratories Inc, San Francisco, Calif), a marker of cells in the G1-M phase of mitosis, or CD11b (DAKO Corp, Carpinteria, Calif), a marker of monocytes, was placed on the sections and incubated at room temperature for 2 hours (anti-Ki67) or 1 hour (anti-CD11b). The working concentrations for anti-Ki67 and CD11b were 214.6 mg/L (1% BSA, pH 7.4) and 85 mg/L (1% BSA, pH 7.4), respectively. The secondary antibodies, Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen Corp, Carlsbad, Calif) 2 mg/mL diluted 1:250 for Ki67 and Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rat IgG (Invitrogen Corp) 2 mg/mL diluted 1:100 for CD11b, were applied for 1 hour at room temperature. Coverslips were mounted with Vectashield containing 4’,6 diamidino-2-phenyl-indole ([DAPI] Vector Laboratories Inc, Burlingame, Calif) to observe all cell nuclei in the tissue. Negative controls with secondary antibody alone or irrelevant isotype-matched antibodies were included in each experiment. The sections were viewed and photographed with a Nikon Eclipse E800 microscope equipped with a digital SPOT camera (Micro Video Instruments, Avon, Mass).

Cell Counting for Quantitation of TUNEL Assays and Immunocytochemistry Assays

For the TUNEL assay and immunocytochemistry for Ki67 or CD11b+ monocytes, all of the stained cells in seven non-overlapping, full-thickness columns extending from the anterior stromal surface to the posterior stromal surface were counted, as previously described.5 The diameter of each column was that of a 400× microscope field. The columns in which counts were performed were selected at random from the central cornea or peripheral cornea at the flap edge where the cut perforated the epithelium of each specimen. Care was taken to only count stromal cells, excluding epithelial cells, during dynamic counts at the microscope on tissue sections.

Electron Microscopy

For transmission electron microscope analysis, the tissue was fixed in 1% formaldehyde and 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4), post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide, sequentially dehydrated in ethanols, and embedded in an Epon and Araldite (Huntsman Advanced Materials Americas Inc, Los Angeles, Calif) mixture. Thin sections were prepared and electron micrographs were taken on a Tecnai 20, 200-kv digital electron microscope (FEI Co, Hillsboro, Ore) using a Gatan image filter (Gatan Inc, Pleasanton, Calif) and digital camera.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using statistical software (Statview 4.5; Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, Calif). Variations were expressed as standard errors of the mean. Statistical comparisons between the groups were performed using analysis of variance with the Bonferonni–Dunn adjustment for multiple comparisons. All statistical tests were conducted at an alpha level of 0.05.

RESULTS

Cell Death in the Stroma Following Femtosecond Laser Flap Formation

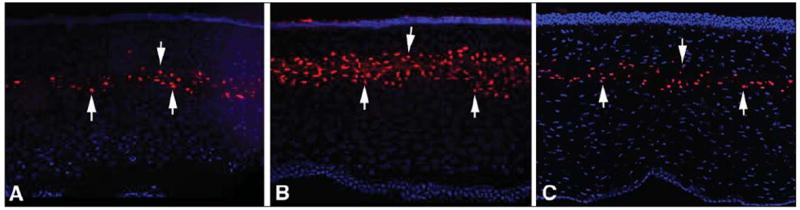

All corneas that had flap formation with the femtosecond laser or the microkeratome had TUNEL-positive cells in the anterior central stroma and the peripheral stroma at 24 hours after the procedure (Fig 1), indicating the presence of cells presumably undergoing apoptosis. No TUNEL-positive stromal cells were detected in control corneas that did not have surgery. Quantitative differences were noted between the groups (Tables 1-4). Thus, the 15 KHz laser triggered significantly more TUNEL-positive cells in both the central cornea and peripheral cornea at the flap edge than the 30 KHz laser, the 60 KHz laser, or the microkeratome. The difference between the 30 KHz or 60 KHz laser and the microkeratome did not reach statistical significance. Corticosteroids had little effect on the number of TUNEL-positive cells with any of the instruments, although a small significant decease was noted with steroids in the peripheral cornea with the 15 KHz laser. No TUNEL-positive cells were identified in the posterior stroma beyond 50% depth or in the endothelium using the microkeratome or any femtosecond laser model.

Figure 1.

Terminal deoxyribonucleotidyl transferase–mediated dUTP-digoxigenin nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay 24 hours after surgery of the central cornea from rabbits that had flap formation with the A) Hansatome microkeratome (Bausch & Lomb, Rochester, NY), B) the 15 KHz Model II femtosecond laser (IntraLase, Irvine, Calif), and C) the 30 KHz Model II femtosecond laser (IntraLase). Cell nuclei are stained blue with 4’,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole and TUNEL-positive cells are stained red (arrows indicate some TUNEL-positive cells in each panel). The level of TUNEL-positive cells triggered by the 60 KHz Model II femtosecond laser (not shown) was similar to that noted with the microkeratome. Original magnification ×400.

TABLE 1.

TUNEL-Positive Cells in the Central Cornea

| Group | No. of Eyes | Mean No. of Cells | SE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microkeratome no steroids | 6 | 12.6 | 0.5 |

| Microkeratome with steroids | 4 | 11.2 | 0.5 |

| 15 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | 4 | 23.2 | 0.5 |

| 15 KHz femtosecond laser with steroids | 4 | 20.2 | 0.5 |

| 30 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | 6 | 14.3 | 0.4 |

| 30 KHz femtosecond laser with steroids | 4 | 14.3 | 0.1 |

| 60 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | 5 | 12.3 | 1.1 |

| Unoperated control | 6 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

TUNEL = terminal deoxyribonucleotidyl transferase–mediated dUTP-digoxigenin nick end labeling, SE = standard error

TABLE 4.

TUNEL-Positive Cells in the Peripheral Cornea, Statistical Comparisons

| Group | P Value |

|---|---|

| Microkeratome no steroids vs. microkeratome with steroids | .05 |

| 15 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids vs. 15 KHz femtosecond laser with steroids | .001* |

| 30 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids vs. 30 KHz femtosecond laser with steroids | 0.06 |

| Microkeratome no steroids vs. 15 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | <.0001* |

| Microkeratome no steroids vs. 30 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | .70 |

| Microkeratome no steroids vs. 60 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | .40 |

| 15 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids vs. 30 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | <.0001* |

| 15 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids vs. 60 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | .0001* |

| 30 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids vs. 60 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | .20 |

TUNEL = terminal deoxyribonucleotidyl transferase–mediated dUTP-digoxigenin nick end labeling

Indicates statistically significant. With the Bonferroni–Dunn adjustment for multiple comparisons, comparisons in this table are not significant unless the corresponding P value is <.0024.

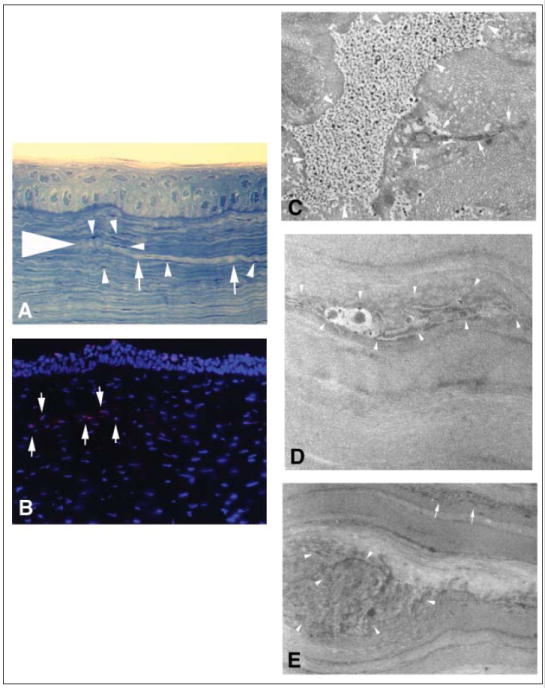

To explore whether cell death noted with the femtosecond laser was indeed apoptosis, or alternatively necrosis, central femtosecond laser ablations that did not have side cuts up to the epithelium were produced with the 30 KHz laser using an energy level of 2.5 μJ. Eyes were processed for TUNEL assay and transmission electron microscopy at 15 minutes, 30 minutes, or 24 hours after ablation. Although TUNEL-positive cells were detected at each time point, only necrotic keratocytes were detected with electron microscopy (Fig 2). Thus, femtosecond laser ablation is an example of a situation in which the TUNEL assay is positive at a site where the predominant mode of cell death is necrosis.

Figure 2.

Terminal deoxyribonucleotidyl transferase–mediated dUTP-digoxigenin nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay and transmission electron microscopy in corneas where an intrastromal cut was produced with the 30 KHz Model II femtosecond laser (IntraLase, Irvine, Calif) without side cuts and a higher than normal energy for this model of 2.7 μJ. (Fig 2A: Large arrowhead indicates end of the stromal laser cut; arrows show the lamellar cut; and small arrowheads show keratocytes.) Thus, there was no epithelial injury produced by the laser ablation. Although positive cells (Fig 2B arrows show TUNEL and stromal cells; Fig 2C, D, and E arrows and arrowheads show necrotic cellular debris) were detected at the site of femtosecond laser ablation using the TUNEL histological assay (Fig 2A and 2B original magnification ×400), only necrotic cells with random disruption of cellular organelles without condensed chromatin or cell shrinkage were detected with transmission electron microscopy (Fig 2 C, D and E, original magnification ×5000).

Cell Replication in the Stroma

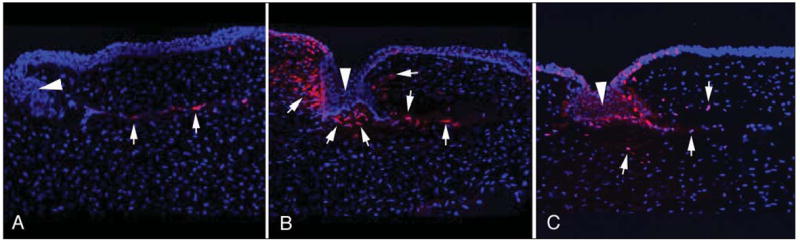

Corneas that had flaps generated with the microkeratome and each model of the femtosecond laser had stromal cells expressing the Ki67 antigen, indicating they were undergoing mitosis at 24 hours after surgery (Fig 3), with the highest levels in both the central and peripheral cornea being at the level of the flap interface in corneas treated with the 15 KHz laser. However, differences between the methods were greatest in the peripheral cornea near the flap margin (Fig 3, Tables 5 and 6) where, on average, twice as many stromal cells underwent mitosis at the level of the flap interface with the 15 KHz laser compared with the microkeratome.

Figure 3.

Mitotic Ki67-stained cells at 24 hours after surgery of the peripheral cornea at and central to the flap edge in rabbits that had flaps formed with A) the Hansatome microkeratome (Bausch & Lomb, Rochester, NY), B) the 15 KHz Model II femtosecond laser (IntraLase, Irvine, Calif), and C) the 30 KHz Model II femtosecond laser (IntraLase). Cell nuclei are stained blue with 4’,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole and Ki67-positive cells are stained red (arrows indicatedsome in each panel). The arrowheads in each panel are the epithelial plugs at the flap margin. In the particular section for the microkeratome shown here, there was no stromal cell proliferation immediately joining the epithelial plug. Other microkeratome specimens had some mitotic cells near the epithelial plug, but never to the extent noted with either the 15 KHz or the 30 KHz laser. Counts were performed at the microscope and care was taken to include only stromal cells and not epithelial cells within the plugs. Images of mitotic Ki67-positive cells in the peripheral cornea with the 60 KHz Model II femtosecond laser are not shown, but in general tended to be similar to those with the 30 KHz laser, although some corneas showed far less Ki67-stained cells, similar to the level noted with the microkeratome (not shown). Original magnification ×400.

TABLE 5.

Mitotic (Ki67-Positive) Cells in the Peripheral Cornea

| Group | No. of Eyes | Mean No. of Cells | SE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microkeratome no steroids | 6 | 6.4 | 0.3 |

| Microkeratome with steroids | 4 | 6.6 | 0.2 |

| 15 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | 4 | 13.4 | 0.8 |

| 15 KHz femtosecond laser with steroids | 4 | 13.7 | 0.4 |

| 30 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | 6 | 10.6 | 0.2 |

| 30 KHz femtosecond laser with steroids | 4 | 10.5 | 0.2 |

| 60 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | 5 | 3.5 | 0.8 |

| Unoperated control | 6 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

TUNEL = terminal deoxyribonucleotidyl transferase–mediated dUTP-digoxigenin nick end labeling, SE = standard error

TABLE 6.

Mitotic (Ki67-Positive) Cells in the Peripheral Cornea, Statistical Comparisons

| Group | P Value |

|---|---|

| Microkeratome no steroids vs. microkeratome with steroids | .80 |

| 15 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids vs. 15 KHz femtosecond laser with steroids | .68 |

| 30 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids vs. 30 KHz femtosecond laser with steroids | .97 |

| Microkeratome no steroids vs. 15 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | <.0001* |

| Microkeratome no steroids vs. 30 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | <.0001* |

| Microkeratome no steroids vs. 60 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | .0001* |

| 15 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids vs. 30 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | <.0001* |

| 15 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids vs. 60 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | <.0001* |

| 30 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids vs. 60 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | <.0001* |

TUNEL = terminal deoxyribonucleotidyl transferase–mediated dUTP-digoxigenin nick end labeling

Indicates statistically significant. With the Bonferroni–Dunn adjustment for multiple comparisons, comparisons in this table are not significant unless the corresponding P value is <.0024.

There was a significant reduction in the number of peripheral mitotic stromal cells with the 30 KHz laser compared with the 15 KHz laser, but this number was still greater than with the microkeratome (Tables 5 and 6). The mean number of peripheral mitotic stromal cells with the 60 KHz laser was significantly less with the 60 KHz laser than with the microkeratome or the 30 KHz laser, although there was considerable variability as is indicated by the larger standard error of the mean in the 60 KHz laser group (Table 5). Corticosteroids had no effect on mitotic stromal cells (Tables 5 and 6). There were no mitotic stromal cells noted in control corneas that did not have surgery.

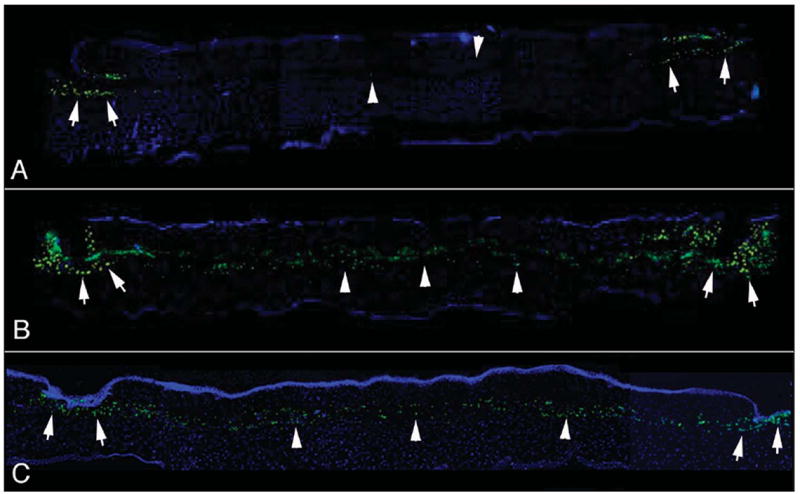

Inflammatory Cellular Response

Monocytes that expressed CD11b were used as a marker for inflammatory infiltration and were detected along the flap interface in all corneas from the four groups that had flaps generated (Fig 4, Tables 7 and 8). Corneas treated with the microkeratome had few monocytes present in the central cornea relative to the peripheral cornea (see Fig 4). Corneas treated with the 15 KHz laser had high levels of monocytes both at the flap margin and in the center of the cornea above and below the interface. There tended to be far fewer monocytes in both the peripheral and central cornea in the 30KHz or 60KHz laser groups, although occasional corneas in the 30 KHz laser group had monocyte levels similar to the average in the 15 KHz laser group (see Fig 4). The regimen of corticosteroids used in this study had no significant effect on monocyte infiltration into the cornea in any groups tested. No monocytes were detected in control corneas that did not have surgery.

Figure 4.

Monocytes expressing CD11b detected at 24 hours after surgery with the A) Hansatome microkeratome (Bausch & Lomb, Rochester, NY), B) the 15 KHz Model II femtosecond laser (IntraLase, Irvine, Calif), and C) the 30 KHz Model II femtosecond laser (IntraLase). There was typically little monocyte infiltration in the center of corneas (arrowheads) with flaps produced with the microkeratome. Monocytes were routinely detected at the flap margins (arrows) near the side cut through the epithelium in the microkeratome group. Greater numbers of monocytes were detected in both the central (arrowheads) and peripheral (arrows) cornea after flap formation with either of the femtosecond lasers, although the mean was significantly greater with the 15 KHz laser. The cornea treated with the 30 KHz laser shown here C) had the highest level of monocyte infiltration of any of the corneas in that group, whereas the 15 KHz cornea shown here B) was average for that group. The levels of monocyte infiltration in corneas that had flaps formed with the 60 KHz laser were similar to those in corneas that had flaps formed with the 30 KHz laser, although some had lower levels similar to those in the microkeratome group (not shown). Original magnification ×200.

TABLE 7.

Monocyte (CD11b-Positive) Cells in the Peripheral Cornea

| Group | No. of Eyes | Mean No. of Cells | SE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microkeratome no steroids | 6 | 10.9 | 0.3 |

| Microkeratome with steroids | 4 | 11.2 | 0.3 |

| 15 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | 4 | 22.6 | 0.7 |

| 15 KHz femtosecond laser with steroids | 4 | 22.0 | 0.6 |

| 30 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | 6 | 13.3 | 0.5 |

| 30 KHz femtosecond laser with steroids | 4 | 13.7 | 0.8 |

| 60 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | 5 | 13.0 | 0.5 |

| Unoperated control | 6 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

TUNEL = terminal deoxyribonucleotidyl transferase–mediated dUTP-digoxigenin nick end labeling

TABLE 8.

Monocyte (CD11b-Positive) Cells in the Peripheral Cornea, Statistical Comparisons

| Group | P Value |

|---|---|

| Microkeratome no steroids vs. microkeratome with steroids | .70 |

| 15 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids vs. 15 KHz femtosecond laser with steroids | .40 |

| 30 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids vs. 30 KHz femtosecond laser with steroids | .70 |

| Microkeratome no steroids vs. 15 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | <.0001* |

| Microkeratome no steroids vs. 30 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | .001* |

| Microkeratome no steroids vs. 60 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | .007 |

| 15 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids vs. 30 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | <.0001* |

| 15 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids vs. 60 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | .0001* |

| 30 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids vs. 60 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | .64 |

TUNEL = terminal deoxyribonucleotidyl transferase–mediated dUTP-digoxigenin nick end labeling

Indicates statistically significant. With the Bonferroni–Dunn adjustment for multiple comparisons, comparisons in this table are not significant unless the corresponding P value is <.0024.

DISCUSSION

Our experience with LASIK performed in humans with the 15 KHz laser was different from that with LASIK performed with the microkeratome. Thus, in the early postoperative period almost all corneas had clinically significant peripheral diffuse lamellar keratitis (with some having central diffuse lamellar keratitis) associated with greater flap edema and slower recovery of vision (M. V. Netto, MD, and S. E. Wilson, MD, unpublished data, 2005). Hourly topical corticosteroids controlled the increased inflammation in most patients, but visual recovery was delayed on average compared with patients who had LASIK using the microkeratome.

To investigate this difference, we initiated a study in rabbits to investigate key parameters of the early wound healing response in corneas treated with the 15 KHz laser or the microkeratome. Subsequently, the newer 30 KHz and 60 KHz lasers became available in our clinic. We noted that postoperative flap edema and diffuse lamellar keratitis in the eyes of patients who had LASIK with the 30 KHz or 60 KHz lasers were markedly reduced and similar to eyes that had LASIK with the microkeratome. Therefore, we also included the 30 KHz and 60 KHz lasers in the our study.

The results of this study demonstrate that there is more stromal cell death (see Fig 1), stromal cell proliferation (see Fig 3), and inflammatory cell infiltration (see Fig 4) with the 15 KHz laser than with the microkeratome at 24 hours after flap formation. Kim et al3 similarly noted more stromal cell death with a 15 KHz femtosecond laser than with a microkeratome. Differences were noted in both the central and peripheral cornea. In the current study, stromal cell death, stromal cell proliferation, and inflammatory cell infiltration were markedly less with the 30 KHz laser, but still greater for most parameters studied than with the microkeratome. The 60 KHz laser results were not statistically different from those of the microkeratome, except that there were more Ki67-positive mitotic stromal cells in the periphery consistent with a stronger healing response at the flap margin.

We hypothesize that the higher levels of stromal cell death and proliferation and inflammatory cell infiltration with the 15 KHz laser, and to a limited extent the 30 KHz and 60 KHz lasers, compared with the microkeratome are attributable to the necrotic mode of stromal cell death associated with the femtosecond laser. Our previous studies,6 which included the TUNEL assay and transmission electron microscopy, demonstrated that flap formation with the microkeratome is predominantly associated with keratocyte apoptosis. However, cell death associated with the femtosecond laser is predominantly necrosis (see Fig 2) and likely a direct energy-related effect of the laser.

This was confirmed by the experiments in which a lamellar cut without a side cut or resulting injury to the epithelium was performed with the 30 KHz laser. This intrastromal ablation produced necrosis identified by typical randomly disrupted cellular morphology without characteristics of apoptosis, such as chromatin condensation and cell shrinkage, when the tissue was examined with transmission electron microscopy (see Fig 2). This is another example of the TUNEL assay detecting necrotic cells under some circumstances7-10 and reinforces the need to confirm the mode of cell death detected by the TUNEL assay in a particular system. The TUNEL assay detects the thousands of DNA ends formed during apoptosis. It is not surprising that under some conditions necrosis can similarly fragment DNA, albeit in a more random manner.

Necrotic debris is a far greater stimulus to inflammatory cell infiltration than apoptotic bodies and other remnants of apoptotic cells, but otherwise should not adversely affect the cellular recovery of the cornea or the clinical results of LASIK performed with the femtosecond laser as long as the resulting inflammation is controlled. This tends to be a greater concern with the 15 KHz laser because greater energy levels are used and, therefore, more keratocyte cells undergo necrosis, which leads to more inflammatory stimulus. In most patients, this inflammation can be suppressed with topical corticosteroids administered during the early postoperative period and extending to 24 to 48 hours. Our studies have noted that the 60 KHz laser, which uses low energies from 0.8 to 1.2 μJ, produces levels of inflammation that are no different from the microkeratome at 24 hours after surgery, even when no corticosteroids are used despite triggering low, but detectible, levels of stromal cell death.

The 15 KHz laser may also induce greater inflammation through a second mechanism. The higher side-cut energies recommended with this laser (typically 1.5 to 2.5 μJ) trigger greater epithelial cell injury at the incision than either the microkeratome or the 30 KHz or 60 KHz lasers (in which side-cut energies are typically 0.9 to 1.2 μJ). Corneal epithelial cells constantly (constitutively) produce pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor alpha, and these cytokines are released by cellular injury.11-13 Greater quantities of these cytokines are likely released into the tears and stroma with the 15 KHz laser, where they may bind receptors on keratocyte cells. The resulting increased production of chemokines by surviving keratocytes6 likely augments the inflammatory cell infiltration associated with the 15 KHz laser.

There are several clinical correlates to the wound healing differences noted with the femtosecond lasers in this study. First, there is a tendency for more inflammation to develop in the early postoperative period when the femtosecond laser is used in LASIK, especially if higher energy levels are used. This trend can be reduced with a particular laser by using less side-cut and lamellar-cut energy and by using femtosecond laser models such as the 30 KHz or 60 KHz lasers where lower energies are routinely employed in flap formation. It is important to note that not only is the energy per pulse lower with the 30 KHz and 60 KHz lasers than with the 15 KHz laser, but the cumulative energy is also lower with the newer laser models. Thus, although the faster repetition rates of the 30 KHz and 60 KHz lasers are certainly desirable for the patient and surgeon from an operational perspective, it is the overall superior design of these laser systems that allows lower energies to be used for both the lamellar and side cuts.

In turn, lower energy application leads to lower stromal cell death and inflammation. Thus, use of the newer lasers allows the surgeon to reduce the frequency of corticosteroid application in the postoperative period (S. E. Wilson, MD, unpublished data, 2006). Importantly, increasing the energy level for the side cut, lamellar cut, or both to form a LASIK flap, which sometimes becomes necessary when the laser is out of alignment or is otherwise not operating optimally, will increase cell death and the tendency toward inflammation.

Second, there tends to be stronger healing at the flap margin and in the interface with the femtosecond laser, as reported by Kim et al.3 This is especially true with the 15 KHz laser, but in our experience is less prominent with the 30 KHz and 60 KHz lasers. This greater healing at the flap edge is visible at the slit lamp as greater scar at the flap margin at 1 or more months after surgery in the human eye compared with the scar noted in the typical eye that has LASIK with the microkeratome. The greater healing of the flap noted with the femtosecond laser is likely an advantage to the patient that decreases the chances of traumatic flap displacements. However, it can be a problem when trying to re-lift the flap for LASIK enhancement. Thus, in occasional patients—especially when enhancement is attempted 6 or more months after the primary procedure with the 15 KHz laser—greater difficulty can be encountered in lifting the flap compared with re-operation with flaps formed using the microkeratome.

The topical corticosteroid regimen examined in this study had little effect on stromal cell apoptosis or mitosis or inflammatory cell infiltration. However, more frequent application could have increased the effects, especially on inflammation, because hourly application is clinically effective in reducing peripheral and central diffuse lamellar keratitis and edema in patients who have LASIK.

Femtosecond laser flap formation is associated with increases in key processes in the corneal wound healing response to LASIK compared with surgery performed with a microkeratome, including inflammatory cell infiltration, especially when higher energy levels are used for the lamellar cut and side cut. The predominant mode of keratocyte cell death associated with the femtosecond laser is necrosis. Alterations in the femtosecond laser that allow cuts to be performed with lower side-cut and lamellar-cut energies have markedly reduced the tendency of these lasers to increase inflammation and improved their ability to promote greater wound healing at the flap edge. Further improvements can be anticipated as our better understanding of the interaction of the laser with the cornea leads to further refinements in femtosecond laser technology and its application.

TABLE 2.

TUNEL-Positive Cells in the Central Cornea, Statistical Comparisons

| Group | P Value |

|---|---|

| Microkeratome no steroids vs. microkeratome with steroids | .13 |

| 15 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids vs. 15 KHz femtosecond laser with steroids | .0049 |

| 30 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids vs. 30 KHz femtosecond laser with steroids | .98 |

| Microkeratome no steroids vs. 15 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | <.0001* |

| Microkeratome no steroids vs. 30 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | .30 |

| Microkeratome no steroids vs. 60 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | .77 |

| 15 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids vs. 30 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | <.0001* |

| 15 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids vs. 60 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | .0001* |

| 30 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids vs. 60 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | .2 |

TUNEL = terminal deoxyribonucleotidyl transferase–mediated dUTP-digoxigenin nick end labeling

Indicates statistically significant. With the Bonferroni–Dunn adjustment for multiple comparisons, comparisons in this table are not significant unless the corresponding P value is <.0024.

TABLE 3.

TUNEL-Positive Cells in the Peripheral Cornea

| Group | No. of Eyes | Mean No. of Cells | SE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microkeratome no steroids | 6 | 11.3 | 0.4 |

| Microkeratome with steroids | 4 | 10.9 | 0.4 |

| 15 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | 4 | 20.2 | 0.6 |

| 15 KHz femtosecond laser with steroids | 4 | 23.2 | 0.5 |

| 30 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | 6 | 11.5 | 0.2 |

| 30 KHz femtosecond laser with steroids | 4 | 13.0 | 1.0 |

| 60 KHz femtosecond laser no steroids | 5 | 10.7 | 0.6 |

| Unoperated control | 6 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

TUNEL = terminal deoxyribonucleotidyl transferase–mediated dUTP-digoxigenin nick end labeling, SE = standard error

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by U.S. Public Health Service grants EY10056 and EY15638 from the National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, and Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc, New York, NY.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial or proprietary interest in the materials presented herein.

References

- 1.Nordan LT, Slade SG, Baker RN, Suarez C, Juhasz T, Kurtz R. Femtosecond laser flap creation for laser in situ keratomileusis: six-month follow-up of initial U.S. clinical series. J Refract Surg. 2003;19:8–14. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-20030101-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Binder PS. Flap dimensions created with the IntraLase FS laser. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2004;30:26–32. doi: 10.1016/S0886-3350(03)00578-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim JY, Kim MJ, Kim TI, Choi HJ, Pak JH, Tchah H. A femtosecond laser creates a stronger flap than a mechanical microkeratome. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:599–604. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holzer MP, Rabsilber TM, Auffarth GU. Femtosecond laser-assisted corneal flap cuts: morphology, accuracy, and histopathology. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:2828–2831. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohan RR, Hutcheon AEK, Choi R, Hong J-W, Lee J-S, Mohan RR, Ambrósio R, Jr, Zieske JD, Wilson SE. Apoptosis, necrosis, proliferation, and myofibroblast generation in the stroma following LASIK and PRK. Exp Eye Res. 2003;76:71–87. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(02)00251-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Helena MC, Baerveldt F, Kim W-J, Wilson SE. Keratocyte apoptosis after corneal surgery. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:276–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Lamki RS, Skepper JN, Loke YW, King A, Burton GJ. Apoptosis in the early human placental bed and its discrimination from necrosis using the in-situ DNA ligation technique. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:3511–3519. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.12.3511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaeschke H, Gujral JS, Bajt ML. Apoptosis and necrosis in liver disease. Liver International. 2004;24:85–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2004.0906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shabalina IG, Panaretakis T, Bergstrand A, Depierre JW. Effects of the rodent peroxisome proliferator and hepatocarcinogen, perfluorooctanoic acid on apoptosis in human hepatoma HepG2 cells. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:2237–2246. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.12.2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Willingham MC. Cytochemical methods for the detection of apoptosis. J Histochem Cytochem. 1999;47:1101–1110. doi: 10.1177/002215549904700901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson SE, Liu JJ. Mohan RR. Stromal-epithelial interactions in the cornea. Prog Retin Eye Res. 1999;18:293–309. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(98)00017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson SE, Mohan RR, Mohan RR, Ambrósio R, Jr, Hong J, Lee J. The corneal wound healing response: cytokine-mediated interaction of the epithelium, stroma, and inflammatory cells. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2001;20:625–637. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(01)00008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hong JW, Liu JJ, Lee JS, Mohan RR, Mohan RR, Woods DJ, He YG, Wilson SE. Proinflammatory chemokine induction in keratocytes and inflammatory cell infiltration into the cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:2795–2803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]