Abstract

Mycoplasma agalactiae, an important pathogen of small ruminants, exhibits a very versatile surface architecture by switching multiple, related lipoproteins (Vpmas) on and off. In the type strain, PG2, Vpma phase variation is generated by a cluster of six vpma genes that undergo frequent DNA rearrangements via site-specific recombination. To further comprehend the degree of diversity that can be generated at the M. agalactiae surface, the vpma gene repertoire of a field strain, 5632, was analyzed and shown to contain an extended repertoire of 23 vpma genes distributed between two loci located 250 kbp apart. Loci I and II include 16 and 7 vpma genes, respectively, with all vpma genes of locus II being duplicated at locus I. Several Vpmas displayed a chimeric structure suggestive of homologous recombination, and a global proteomic analysis further indicated that at least 13 of the 16 Vpmas can be expressed by the 5632 strain. Because a single promoter is present in each vpma locus, concomitant Vpma expression can occur in a strain with duplicated loci. Consequently, the number of possible surface combinations is much higher for strain 5632 than for the type strain. Finally, our data suggested that insertion sequences are likely to be involved in 5632 vpma locus duplication at a remote chromosomal position. The role of such mobile genetic elements in chromosomal shuffling of genes encoding major surface components may have important evolutionary and epidemiological consequences for pathogens, such as mycoplasmas, that have a reduced genome and no cell wall.

Bacteria of the Mycoplasma genus belong to the class Mollicutes and represent a remarkable group of organisms that derived from the Firmicutes lineage by massive genome reduction (41, 51). Consequent to this regressive evolution, modern mycoplasmas have been left with small genomes (580 to 1,400 kb), a limited number of metabolic pathways, and no cell wall. Due to these particularities, members of the Mycoplasma genus have often been portrayed as “minimal self-replicating organisms.” Despite this apparent simplicity, a large number of mycoplasma species are successful pathogens of humans and a wide range of animals, in which they are known to cause diseases that are often chronic and debilitating (1, 33). The surface of their single membrane is considered a key interface in mediating adaptation and survival in the context of a complex, immunocompetent host (10, 13, 34, 40). Indeed, mycoplasmas possess a highly versatile surface architecture due to a number of sophisticated genetic systems that promote intraclonal variation in the expression and structure of abundant surface lipoproteins (9, 50). Usually, these systems combine a set of contingency genes with a molecular switch for turning expression on or off that is based on either (i) spontaneous mutation (slipped-strand mispairing), (ii) gene conversion, or (iii) specific DNA rearrangements (9). While high-frequency phenotypic variation using the two first mechanisms has been described thoroughly for other bacteria (47), switching of surface components by shuffling of silent genes at a particular single expression locus has been studied mainly in mycoplasmas (3, 8, 14, 16, 23, 39, 43).

Mycoplasma agalactiae, an important pathogen responsible for contagious agalactia in small ruminants (listed by the World Organisation for Animal Health), possesses a family of lipoproteins encoded by the vpma genes for which phase variation in expression is driven by a “cut-and-paste” mechanism involving a tyrosine site-specific recombinase designated Xer1 (16). Data previously gathered with the PG2 type strain identified a single vpma cluster (42) composed of six vpma genes adjacent to one xer1 gene (Fig. 1A). Based on fine genetic analyses, Xer1 was further shown to mediate frequent site-specific DNA rearrangements by targeting short DNA sequences located upstream of each vpma gene (8, 16). While some vpma rearrangements can be phenotypically silent, others result in Vpma on-off switching by linking a silent vpma gene sequence immediately downstream of the unique vpma promoter. Because site-specific recombination can be reciprocal, the initial vpma configuration can be restored without a loss of genetic information.

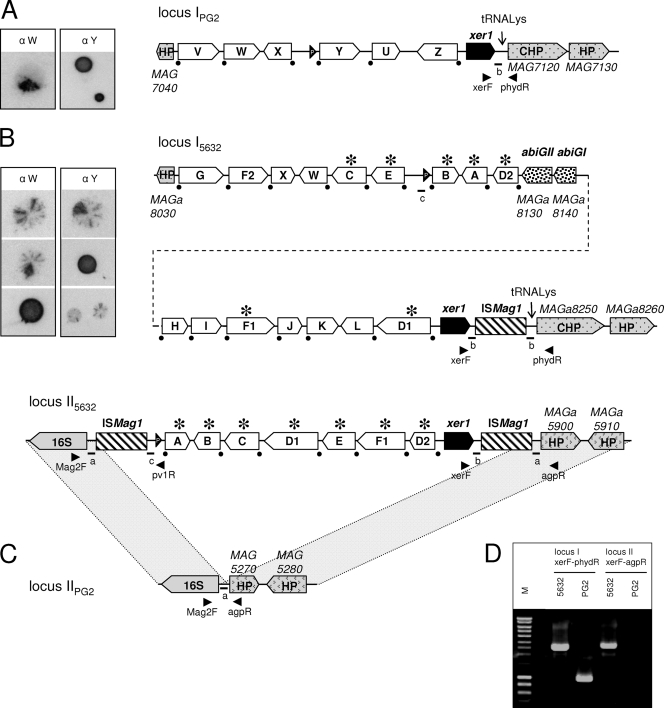

FIG. 1.

Comparison of M. agalactiae vpma loci between the PG2 type strain and strain 5632. Schematics represent the organization of the vpma loci in clonal variant 55.5 derived from PG2 (16, 42) (A) and in clonal variant c1 derived from strain 5632 (B). (C) Counterpart of locus II5632 in PG2 showing the absence of vpma genes in this region. (D) The presence of two distinct loci in 5632 was confirmed by PCR, using the primer pair xerF-phydR or xerF-agpR, and the resulting amplicons are shown. The locations of the primers are indicated by arrowheads in panels A, B, and C. Large white arrows labeled with letters represent Vpma CDSs. The positions of the promoters are represented by black arrowheads labeled “P.” The two non-Vpma-related CDSs (abiGI and abiGII) are indicated by large arrows filled with a dotted pattern. ISMag1 elements are indicated by hatched boxes. Recombination sites downstream of each vpma gene are indicated by black dots. An asterisk indicates that the corresponding vpma gene is present at two distinct loci. Schematics were drawn approximately to scale. HP, hypothetical protein; CHP, conserved hypothetical protein. Small letters and bars indicate the positions of short particular sequences mentioned in the text and in Fig. 3 and 4. The pictures on the left side of panels A and B illustrate the variable surface expression of Vpma, as previously described (8, 17). These correspond to colony immunoblots using Vpma-specific polyclonal antibodies recognizing PG2 VpmaW (α W) and VpmaY (α Y) epitopes.

The vsa family of the murine pathogen M. pulmonis (3, 39), the vsp family of the bovine pathogen M. bovis (2, 24), and the vpma family of M. agalactiae all generate intraclonal surface diversity by using very similar molecular switches (23), although their overall coding sequences seem to be specific to the Mycoplasma species. DNA rearrangements also govern phase variation of the 38 mpl genes of the human pathogen M. penetrans (27, 35, 38). However, in this mycoplasma species the molecular switch is slightly different, since each mpl gene possesses its own invertible promoter (19). In M. penetrans, the individual expression of each mpl gene can then be switched on and off in a combinatory manner, resulting in a large number of possible Mpl surface configurations. Since M. pulmonis, M. bovis, and M. agalactiae all belong to the Mycoplasma hominis phylogenetic cluster (48) and are relatively closely related, while M. penetrans belongs to the distinct Mycoplasma pneumoniae phylogenetic cluster (30, 48), it is tempting to speculate that the vsa, vsp, and vpma systems were all inherited from a common ancestor and that the bulk of their coding sequences evolved independently in their respective hosts while the molecular switch mechanism was retained.

In so-called “minimal” bacteria, the occurrence of relatively large genomic portions dedicated to multigene families, with genes encoding phase-variable, related surface proteins, suggests that they serve an important function(s). Data accumulated over the years for several mycoplasma species tend to indicate that one general purpose of these systems is to provide the mycoplasma with a variable shield that modulates surface accessibility in order to escape the host response and to adapt to rapidly changing environments (10, 11, 13, 40, 50). On the other hand, the sequences of phase-variable proteins are relatively conserved within one species but divergent between species, suggesting a more specific role for these molecules.

The role of the Vpma family of M. agalactiae has yet to be elucidated, but it was recently shown that Vpma switches in expression occur at a remarkably high rate in vitro (10−2 to 10−3 per cell per generation) (8, 17). The vpma systems described for PG2 (16) and another M. agalactiae strain, isolated in Israel (in which Vpmas were designated Avg proteins [14]), both revealed a repertoire of six vpma genes and only one promoter, suggesting that in M. agalactiae the number of Vpma configurations is limited to six. This contrasts with the situation commonly found in other Mycoplasma variable systems, which can offer a larger mosaic of surface architecture because of the concomitant switches of several related surface proteins and/or because of a larger number of phase-variable genes.

To further understand the degree of diversity that can be generated at the surface of M. agalactiae, we analyzed the vpma gene content of a field strain, 5632, whose genome was recently sequenced by our group (unpublished data). The present study shows that 5632 contains a total of 23 vpma genes distributed in two distinct loci that both contain a recombinase gene. Further genomic and proteomic analyses indicated that the capacity of 5632 to vary its Vpma surface architecture is far more complex than that described for the type strain. Unlike the case for PG2, both 5632 vpma loci are associated with several mobile genetic insertion elements (IS) that could play an evolutionary role in the dynamics of vpma repertoires, as suggested by data presented here. One 5632 vpma locus contains open reading frames (ORFs) that are highly conserved in both M. bovis, a closely related bovine mycoplasma, and the phylogenetically distant mycoplasmas of the M. mycoides cluster, which are also important ruminant pathogens. Whether these were acquired through evolution or through horizontal transfer is discussed. The present study reveals an additional degree of complexity for the Vpma system and further suggests that some field strains might have more dynamic genomes and a more variable surface than was first estimated (42).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, culture conditions, and DNA isolation.

M. agalactiae type strain PG2, clone 55.5 (16), and strain 5632, clonal variant C1 (26), have been described previously. These strains were isolated independently from goats in Spain. The experiments reported here were all performed with these clonal variants, but for simplicity, we refer to them as strains PG2 and 5632 only. M. agalactiae field isolates were kindly provided by F. Poumarat (AFSSA, Lyon, France) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Mycoplasmas were propagated in SP4 liquid medium (46) at 37°C, and genomic DNAs were extracted as described elsewhere (7, 37).

Identification of M. agalactiae vpma and associated loci.

Whole-genome sequencing of strain 5632 (clonal variant C1) was performed as follows. A library of 3-kb inserts (library A) was generated by mechanical shearing of the DNA followed by cloning of the blunt-ended fragments into the pcDNA2.1 (Invitrogen) Escherichia coli vector. Two libraries of 25-kb (library B) and 80-kb (library C) inserts were generated by HindIII partial digestion and cloning into the pBeloBAC11 (Caltech) modified E. coli vector. The plasmid inserts of 10,752, 3,072, and 768 clones picked from libraries A, B, and C, respectively, were end sequenced by dye terminator chemistry on ABI3730 sequencers. The PHRED/PHRAP/CONSED software package was used for sequence assemblies. Gap closure and quality assessment were performed according to the Bermuda rules, with 10,307 additional sequences. The vpma loci of strain 5632 were detected by DNA homology to those previously described for PG2 (positions of the loci on the 5632 genome are given with reference to the first nucleotide of the dnaA gene as nucleotide [nt] 1) and were annotated using the CAAT-Box platform (15), with the aid of Artemis software (36) and ACT software (5). The BLAST program suite was used for sequence homology searches of nonredundant databases (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/blast.cgi). In order to determine the extent of sequence similarity, alignments between sequences were performed using Needle (Needleman-Wunsch global alignment algorithm) and Water (Smith-Waterman local alignment algorithm) (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/emboss/align/) software. Designations of 5632 vpma genes were based on local and global alignment scores, using all vpma gene sequences, including those previously described for PG2. The same name was attributed to a vpma gene presenting an amino acid sequence identity of >50% in the global alignment (Needle) and an amino acid sequence identity of >70% in the local alignment (Water). Using these rules, strain 5632 was found to contain the vpmaW and vpmaX genes also present in PG2. Also, distinct names were given to vpmaY and vpmaF, although they displayed global identities of >50%, because their local identities were <70%. vpma products with highly similar sequences that differed only in the number of C-terminal repeats were considered allelic versions and were designated with the same letter followed by different numbers (i.e., VpmaD1 and VpmaD2 or VpmaF1 and VpmaF2). Finally, vpmaI was not considered an allelic version of vpmaD because the C-terminal repeated region of its corresponding product displayed a local identity of 64.7% (<70%) with the VpmaD1 and -D2 counterparts.

Direct sequencing of PCR products and of genomic DNA (18, 20) was performed using specific primers (see Table S2 in the supplemental material) at the sequencing facility of UMR 5165 (CNRS, UPS, CHU Purpan, Toulouse, France).

Phylogenetic analyses were performed using MEGA 3.1 (21) and the neighbor-joining tree method. The reliability of the tree nodes was tested by performing 500 bootstrap replicates.

PCR assays.

PCR assays were performed on an Eppendorf Mastercycler ep-Gradient thermocycler, using 5 ng M. agalactiae DNA as a template and using specific primers (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). PCR assays were performed with 25-μl reaction mixtures containing a 0.4 mM concentration of each primer, PCR buffer (with MgSO4; New England Biolabs) at a 1× final concentration, a 200 mM concentration of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and 2.5 U Taq DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs). Reaction mixtures were subjected to 2 min at 94°C; 30 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 55°C, and 30 s at 72°C; and a final elongation step of 5 min at 72°C. All PCR assays were performed at the unique annealing temperature of 55°C, using primer pair xerF-phydR for specific amplification of locus I, primer pair xerF-agpR or Mag2F-agpR for locus II, primer pair aip1F-aip1R for the abiGI gene, and primer pair aip2F-aip2R for the abiGII gene. PCR products were analyzed by gel electrophoresis on 1% agarose gels.

Colony immunoblotting and proteomic analyses.

Colony immunoblotting was performed as previously described (8). Briefly, nitrocellulose membranes were placed on mycoplasma colonies freshly grown on agar medium and then removed and rinsed three times in TS buffer (10 mM Tris, 154 mM NaCl, pH 7.4). Membranes were then incubated overnight at 4°C with previously described rabbit Vpma-specific antibodies (8), washed three times in TS buffer containing 0.05% Tween 20 (Roth), and then incubated for 1 h at 25°C in a 1:2,000 dilution of swine anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Dako). After three washes, the colony blots were developed for 15 to 30 min in 4-chloro-1-naphthol and 0.02% hydrogen peroxide. The reaction was stopped by washing the blots in sterile distilled water.

Proteins that partitioned into Triton X-114 were extracted from strain 5632 as previously described (4), precipitated overnight at −70°C after the addition of 9 volumes of cold methanol, centrifuged for 10 min at 12,000 × g, and subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The gel was sliced into 16 sections which were subjected to trypsin digestion. Peptides were further analyzed by nano-liquid chromatography coupled to ion-trap tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).

Peptides were identified with SEQUEST through the Bioworks 3.3.1 interface (Thermo-Finnigan, Torrance, CA), using a database consisting of both direct and reverse-sense Mycoplasma agalactiae strain 5632 entries (1,652 entries). Using the following criteria as validation filters, the false-positive rate was null: ΔCN ≥ 0.1; Xcorr versus charge state, ≥1.5 (+1), 2.0 (+2), or 2.5 (+3); peptide probability, ≤ 0.001; and number of different peptides, ≥2.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The GenBank accession numbers for locus I5632 and locus II5632 are FP245515 and FP245514, respectively.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Genome sequencing of strain 5632 reveals an extended vpma repertoire.

The fully sequenced genome of M. agalactiae strain 5632 revealed a total of 23 vpma genes (Fig. 1). In contrast to the case for the PG2 type strain, this extended repertoire is distributed on two distinct chromosomal loci, loci I and II, that contain 16 and 7 vpma genes, respectively. BLAST analyses identified only two genes having significant similarity with those previously described for PG2 (16, 42), namely, vpmaW and vpmaX, with the others (vpmaA to vpmaG) only sharing blocks of high similarity with PG2 vpma genes (Fig. 2).

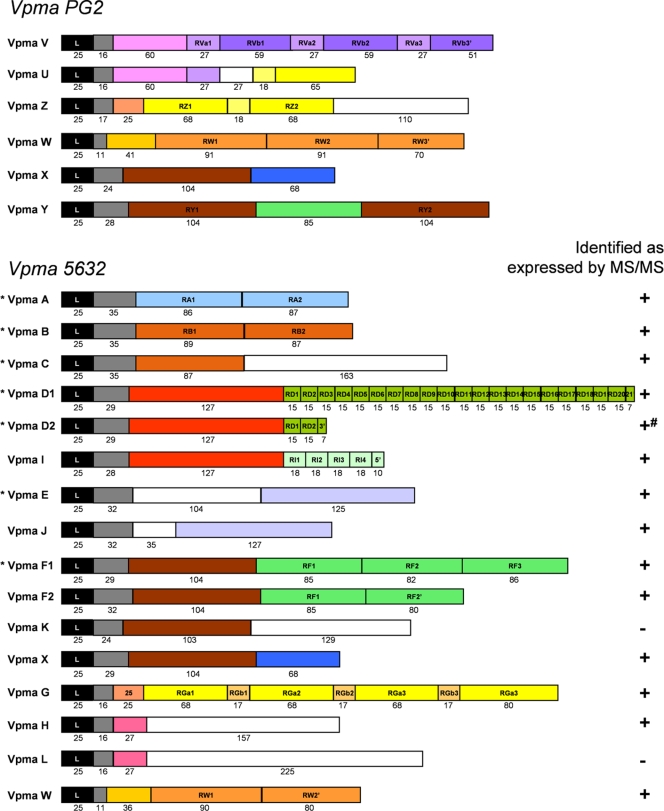

FIG. 2.

Structural features and comparison of vpma gene products in M. agalactiae strains PG2 and 5632. Predicted Vpma proteins are represented schematically by boxes and begin with a homologous 25-amino-acid leader sequence (black boxes) followed by regions that have homology between vpma gene products or that are repeated within the same product (colored boxes). Two boxes of the same color display an amino acid identity of >30%. White boxes represent unique sequences. Numbers below boxes indicate the numbers of amino acids. For strain 5632, detection by MS/MS of expressed specific Vpma peptides is noted (+). −, no specific peptides were detected for the corresponding Vpma; +#, VpmaD2 peptides detected are not specific because all are shared with VpmaD1 or -I (see the list of detected peptides in Table S3 in the supplemental material). An asterisk indicates that the corresponding vpma gene is present in 5632 at both vpma loci.

More precisely, locus I5632 is 19,453 bp long and is the counterpart of the PG2 vpma locus (Fig. 1A) because of their flanking coding sequences (CDSs) being nearly identical. In addition to 16 vpma genes, locus I5632 contains two CDSs (MAGa8140 and MAGa8130) that have no homology with the Vpma family but were found to have high amino acid similarity with Streptococcus agalactiae abiGI and abiGII gene products (45). The two corresponding genes are lacking in PG2 and were designated abiGI and abiGII, respectively. Locus I5632 further differs from its PG2 counterpart by the presence of an IS element corresponding to the previously described ISMag1 (31). This IS element is immediately adjacent to the 3′ end of the integrase-recombinase xer1 gene, whose product is identical to that in PG2.

The second vpma locus of 5632, locus II5632, is 8,462 kb long and contains only seven vpma genes clustered between two ISMag1 copies, themselves flanked by a 16S rRNA gene at the 5′ end and by a CDS annotated as a hypothetical protein (HP) gene (MAGa5900) at the 3′ end. In PG2, this region is highly conserved, except that it does not contain any IS element or vpma or any other gene (locus IIPG2) (Fig. 1C and below). DNA BLAST analyses of locus II5632 demonstrated that all seven vpma coding sequences are identical to the seven vpma genes of locus I5632 (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, an identical xer1 gene also occurs at both vpma loci of strain 5632. Since a single functional gene would be sufficient to generate DNA rearrangements in each locus, the duplication was further confirmed by PCR to rule out any possible artifact of sequence assembling. This was performed using a xer1-specific primer in combination with a primer specific to the 3′ region of locus I (phydR) or locus II (agpR) (Fig. 1D).

The Vpma repertoire is composed of common and distinct structures.

Detailed analyses of the 23 vpma coding regions of strain 5632 showed that (i) 2 are allelic versions of PG2 vpma genes (vpmaW and vpmaX), (ii) 7 are duplicated (vpmaA, -B, -C, -D1, -D2, -E, and -F1) and distributed in two vpma loci that are 250 kbp apart, and (iii) 2 are allelic copies of vpmaD (vpmaD1 and -D2) and vpmaF (vpmaF1 and -F2) that vary mainly in the number of C-terminal repeat motifs. Consequently, strain 5632 contains 12 new, distinct Vpma products compared to PG2 (Fig. 2). All vpma gene products contain a conserved amino acid signal sequence at the N terminus, followed by a lipobox and an 11-amino-acid conserved sequence (41). Within 5632, some mature vpma gene products are unique (VpmaA, -G, and -W), while others share blocks of amino acids between them (VpmaB, -C, -D1, -D2, -E, -F1, -F2, -H, -I, -J, -K, -L, and -X). Also, most Vpmas contain amino acid blocks that are directly repeated (VpmaA, -B, -D1, -D2, -I, -F1, -F2, -G, and -W). These data indicate that the diversity in the Vpma family is represented by a mosaic of structures that is suggestive of homologous recombination events between vpma genes, gene duplication, and/or insertion-deletion of repeated motifs. For instance, VpmaF1 and VpmaF2 share a common block of 104 amino acids with VpmaK and VpmaX and a common block of 85 amino acids with VpmaY that is not found in VpmaK or VpmaX. Some Vpmas, such as VpmaD1 and -D2 or VpmaF1 and -F2, represent size variants of the same Vpma with a variable number of repeated motifs at the C terminus (e.g., VpmaD1 and -D2 contain 20 and 2 repeated motifs of 15 amino acids, respectively). Additionally, VpmaI may have a common ancestor with VpmaD1 and -D2 and can be seen as the result of combined events, such as gene duplication followed by sequence drift and/or repeat expansion at the 3′ end.

Anti-VpmaW and anti-VpmaY rabbit antibodies previously produced against Vpma products of strain PG2 (8) also reacted with 5632 surface-exposed epitopes in colony immunoblots (Fig. 1) and revealed the presence of sectored colonies characteristic of high-frequency variation in expression. Most likely, 5632 Vpmas recognized by these antibodies correspond to VpmaW and to VpmaF1 and/or -F2, which share blocks of amino acids with PG2 VpmaY (Fig. 2).

To better define the Vpma products expressed by strain 5632, proteins that partitioned in Triton X-114 detergent were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed by in-gel trypsin digestion and by LC-MS/MS. The results showed that at least two specific peptides were detected for 13 Vpmas (VpmaA, -B, -C, -D1, -E, -F1, -F2, -G, -H, -I, -J, -X, and -W), indicating that these were expressed by 5632 during propagation (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). While VpmaD1-specific peptides were detected, the expression of VpmaD2 could not be assessed because all VpmaD2 trypsin peptides were also carried in VpmaD1 or VpmaI. No peptides specific to VpmaL and VpmaK were detected, although they possess long specific sequences of 225 and 129 amino acids, respectively (Fig. 2). Whether VpmaL and VpmaK are expressed at low levels or under different conditions cannot be determined. Finally, all Vpmas encoded by locus II5632 are duplicated at locus I5632, and consequently, their expression cannot be monitored by this method or by any other method, such as Northern blot analysis, because their sequences are also identical at the DNA level.

The global proteomic approach taken above is qualitative and does not reflect the level of expression of each Vpma, two of which are predicted to be expressed at high levels by the clonal population, while others should reflect only a minority of back-switchers. In PG2, the vpma locus contains a unique promoter which drives the expression of the vpma gene localized immediately downstream, while the other vpma genes remain silent (16). This promoter region was more precisely defined by primer extension by Flitman-Tene et al. (14), and a similar sequence was detected in each locus of strain 5632. Therefore, Vpma expression in 5632 is most likely driven at each locus by a single promoter sequence which is highly conserved between the two loci (99% nucleotide identity). In locus I5632, the promoter sequence is located upstream of the vpmaB gene, while in locus II5632 it is upstream of vpmaA, suggesting that these two Vpmas would be coexpressed predominantly by the clonal population. However, in the absence of specific antibodies, this hypothesis cannot be tested. One interesting observation is that the length of a poly(T) tract located between the putative −35 and −10 boxes of the vpma promoters varies among the three vpma promoters sequenced and is 14, 15, and 12 nt long for loci I of PG2 and 5632 and for locus II of 5632, respectively (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). In other variable mycoplasma systems, i.e., the Vlp system of M. hyorhinis, fluctuation in the length of the polynucleotide tract between the −35 and −10 boxes has been shown to affect transcription (12). Whether this is also the case for the M. agalactiae species, and for strain 5632 in particular, cannot currently be tested because of the complexity of the 5632 vpma system. In PG2, DNA rearrangements are mediated by Xer1, which recognizes a specific recombination site (RS) sequence located upstream of each vpma gene. Indeed, analysis of the 5632 and PG2 vpma loci revealed that a rigorously identical RS sequence is located upstream of each of the 29 vpma genes (23 in 5632 and 6 in PG2). This suggests that each vpma locus of strain 5632 can independently undergo DNA rearrangements and that the concomitant expression of two distinct Vpmas is most likely to occur frequently in this strain. If so, 5632 could theoretically display 91 different Vpma surface configurations, compared to only 6 for the type strain PG2. In parallel, additional Vpma size variations by insertion or deletion of direct repeats can further participate in altering surface architecture.

Evidence of horizontal gene transfer at the vpma locus of 5632.

As mentioned earlier, M. bovis is a close relative of M. agalactiae and generates surface variation by using a very similar genetic system, designated the vsp gene family. Both the vsp and vpma systems have several common features, including (i) vsp or vpma related genes are clustered in close proximity to a conserved recombinase gene (32); (ii) the recombination site involved in DNA rearrangements is identical, except for a single nucleotide polymorphism that is conserved in each species; and (iii) vpma or vsp genes code for proteins having a signal peptide that is highly conserved between the two systems. Unlike the PG2 vpma loci, the vpma loci of 5632 are associated with IS elements, as in M. bovis (23), and one, locus I5632, contains two non-vpma genes, abiGI and abiGII, that have 86.97 and 85.15% overall DNA identity with two M. bovis ORFs, ORF4 and ORF5 (23), respectively, located in the vsp locus. A search of the databases revealed that abiGI and abiGII from strain 5632 also match with gene products annotated as conserved hypothetical products in Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. mycoides biotype LC strain GM12 (22) and M. mycoides subsp. mycoides SC strain PG1 (49), with >50% amino acid similarity in the global alignment (Table 1). While abiG homologs are present in several gram-positive bacteria, such as Streptococcus agalactiae and Streptococcus suis (6, 45), none was found in other Mollicutes sequences available in the databases, which included 21 complete genomes.

TABLE 1.

abiG-related gene products in Mollicutes and other bacteria

| Strain | Presence of sequence (% identity, % similarity) related to Mycoplasma agalactiae strain 5632 sequencea

|

|

|---|---|---|

| AbiGI-like (MAGa8140) | AbiGII-like (MAGa8130) | |

| M. agalactiae PG2 | − | − |

| M. bovis PG45 | + (84.8, 93.6) | + (81.1, 91.3) |

| M. mycoides mycoides SC PG1 | + (40.8, 59.2) | + (41.8, 64.6) |

| M. mycoides mycoides LC GM12 | + (41.7, 59.2) (Mmycm_04185) | + (31.9, 51.6) (Mmycm_04180) |

| + (40.1, 58.5) (Mmycm_00130) | + (32.6, 50.9) (Mmycm_00135) | |

| Other Mollicutes strains | − | − |

| Streptoccusagalactiae H36B | + (40.2, 58.3) | + (41.2, 65.3) |

| Streptococcus suis 05ZYH33 | + (41.2, 58.3) | + (40.4, 66.3) |

| Non-Streptococcus spp. | + (<40, not available) | + (<40) |

+, presence of homologous sequence; −, absence of homologous sequence in public databases (as of June 2008). Identity and similarity percentages between amino acid sequences were obtained using the Needle alignment program (http://mobyle.pasteur.fr/cgi-bin/portal.py).

The abiGI and abiGII genes were first described for Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris UC653 (28), where they occur as an operon carried by a conjugative plasmid and confer resistance to phage infection (29). Detection by LC/MS-MS of AbiGII-like specific peptides in the Triton X-114 detergent phase of 5632 indicates that the corresponding abiGII gene is expressed, although there is no hydrophobic domain that could account for this partitioning. Previous attempts to define the functions of abiGI and abiGII of Streptococcus species failed (44), and whether abiG homologues found in mycoplasmas have a role in protecting them against phage attack remains to be addressed. Nevertheless, comparison of AbiGI and AbiGII amino acid sequences by constructing neighbor-joining trees (500 bootstraps) indicated a strong relationship between Mycoplasma and Streptococcus sequences, suggesting that their corresponding genes might have undergone horizontal gene transfer (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

To further define the occurrence of the two abi genes in M. agalactiae, a collection of 92 strains representative of (i) various geographical areas and (ii) various histories (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) was screened by PCR for the presence of abiG genes, using the specific primer pairs aip1F-aip1R and aip2F-aip2R. PCR products corresponding to each gene were obtained for 11 strains of 92 total strains. Further PCR assays showed that like the case for Streptococcus agalactiae, the two abiG genes always occur next to each other. Interestingly, direct genome sequencing of six abiG-positive strains, using aip2F2 as a primer, showed that the abiGII gene is always associated with vpma genes. Because strains displaying abiG genes in their vpma loci have very different geographical origins (Ivory Coast, Spain, and France), this result raised the question of whether these genes were inherited vertically from an M. agalactiae/M. bovis common ancestor or whether the vpma locus is a hot spot for their insertion. Since the vpma locus is frequently subjected to DNA rearrangements, deletion of abiG genes by intrarecombination involving, for instance, vpma-RS sequences, may easily have occurred, resulting in abiG-negative strains.

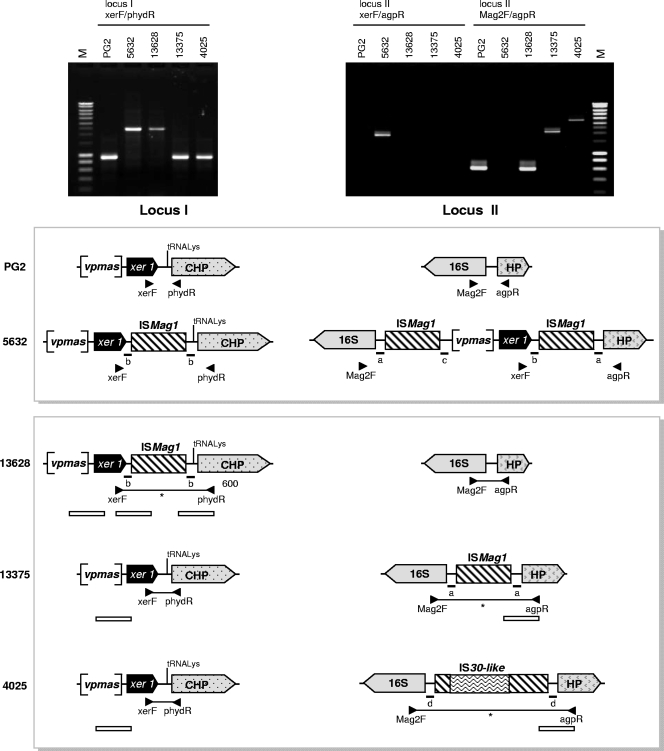

Plasticity of M. agalactiae vpma loci.

To define whether the occurrence of the two vpma loci observed in strain 5632 is common among M. agalactiae strains, a PCR assay was performed with primer pairs xerF-phydR, xerF-agpR, and Mag2F-agpR, which yield amplicons corresponding to either locus I or II of PG2 and/or 5632. More specifically, the primer pairs xerF-phydR and xerF-agpR target the 3′ ends of the loci, which are not affected by vpma rearrangements, while Mag2F and agpR were designed to amplify a more or less empty locus II under our PCR conditions. The assay was conducted with the panel of 92 strains (see above). The results showed that 89 strains produced an amplification profile identical to that obtained with PG2, while 3 showed new profiles, none of which was identical to that obtained with 5632 (Fig. 3). Sequencing of PCR products or selected genomic regions showed that (i) strain 13628, like 5632, contains an IS element at locus I while displaying a locus II similar to that of PG2; and (ii) strains 13375 and 4025, like PG2, display no IS at locus I while carrying a locus II containing one or more IS but no vpma genes, with strain 4025 having an IS30-like insert in an ISMag1 element. These data suggest that the occurrence of a vpma cluster at locus II is a rare event and has so far been observed only in strain 5632, while the occurrence of vpma genes at locus I is shared by all M. agalactiae strains tested so far.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of vpma loci or their counterparts in M. agalactiae strains PG2, 5632 13628, 13375, and 4025. Pictures represent the amplification of locus I and/or II by use of primers xerF-phydR, xerF-agpR, and Mag2F-agpR, whose positions are indicated in the schematics by arrowheads. Schematics represent vpma locus I and vpma locus II or its counterpart. Brackets indicate vpma gene cluster localization next to the xer1 gene (filled black arrow). IS elements (ISMag1 or IS30-like) are indicated by hatched boxes or boxes with wavy lines. Lines traced between primers symbolize the PCR amplicons obtained, with asterisks indicating those which were directly sequenced. White bars below the loci indicate regions that were directly sequenced using genomic DNA. Small letters (a, b, c, and d) represent the 14-nt sequences that flanked the IS.

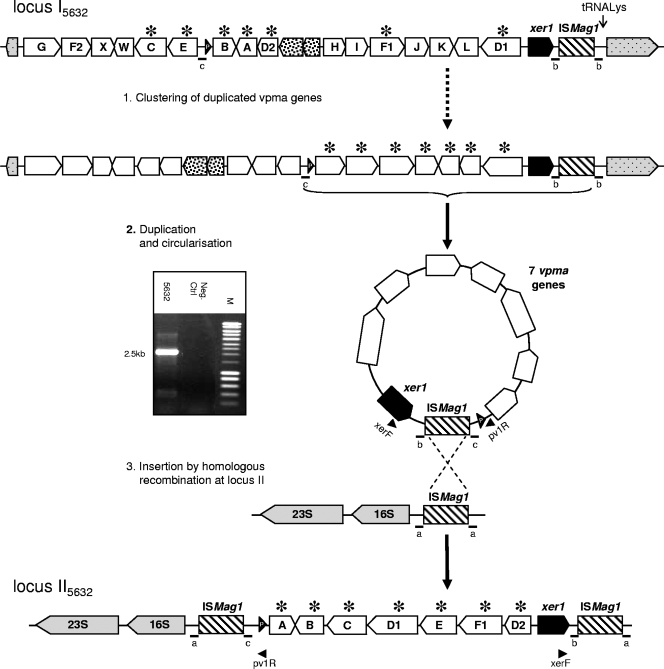

The presence of an ISMag1 element in close proximity to vpma locus I in 5632 is not an isolated event, since it is shared by at least one other strain, 13628, which unlike 5632, was isolated in France in 2003 from a goat ear canal. ISMag1 belongs to the IS30 family (31), which generates, when inserting itself into a host genome, a direct repeat that flanks the IS (25). Indeed, ISMag1 of locus I is flanked in 5632 and in 13628 by an identical 14-nt directly repeated sequence (Fig. 3), suggesting that its insertion most likely occurred in an ancestor common to the two strains. Interestingly, the 14-nt element found on each side of the IS of locus II13375 (Fig. 3) is also repeated in locus II5632 as if flanking the whole locus, including the IS. Because no other 14-nt directed repeat is found in the vicinity of the two IS, this suggested the introduction of the vpma cluster at locus II5632 via a duplication-insertion mechanism involving a circular intermediate carrying a set of vpma genes together with an ISMag1 element (Fig. 4). In this scenario, the duplicated vpma genes would have first clustered at one end of locus I via a series of DNA recombination events. In a second step, part of locus I, including xer1 and ISMag1, would have been duplicated and circularized to finally recombine at locus II via a single crossover between the IS elements. One argument in favor of the occurrence of the circular form is that a PCR product was obtained with strain 5632, using outwardly oriented primers pv1R and xerF, and its partial sequencing revealed the presence of an ISMag1 element next to a sequence “c,” usually found next to the promoter (Fig. 4). Whether this result really reflects a duplication-excision event of part of vpma locus I and whether the circular form can reinsert itself elsewhere in the genome have still to be demonstrated formally. Nevertheless, the 100% nucleotide identity observed between loci I and II of 5632 indicates that this duplication event occurred relatively recently.

FIG. 4.

Scenario of duplication-insertion of strain 5632 vpma genes from locus I to locus II via a circular intermediate. Schematics illustrate a putative scenario in which the vpma cluster of 5632 at locus II originates from locus I by a mechanism of duplication-insertion involving a circular intermediate and IS elements. Small bars with a letter below represent 14-nt sequences (a, b, and c) flanking the ISMag1 element either after an insertion event (a and b) or after a homologous recombination event (c). The dotted arrow indicates the clustering process for seven vpma genes at one end of locus I, starting from the current configuration. It represents a series of an unknown number of possible DNA rearrangements. Asterisks indicate duplicated vpma genes. The gel picture shows PCR amplification of the circular intermediate obtained using primers xerF and pv1R, with strain 5632 crude DNA extract as the template.

Conclusions.

A number of sophisticated genetic systems devoted to high-frequency surface variation have been described for mycoplasma species. Many of these systems appear as small sets of species-specific genes, which are nearly identical in all of the isolates and are clustered at one locus. The clustering of these genes has been proposed to facilitate recombination events which generate diversity, and theoretically, a wide range of surface diversity can be produced with only a few genes, particularly as they are prone to internal rearrangements of their sequences. Our characterization of a new set of vpma genes in an M. agalactiae field isolate (5632) illustrates this point. This new repertoire is far more complex than that first described for the PG2 type strain and represents a mosaic of structures that is suggestive of homologous recombination events between vpma genes, gene duplication, and/or insertion-deletion of repeated motifs (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). This opens the question of the true diversity in equivalent variable systems from mycoplasmas with apparently few variable genes, most of which have been sequenced from type strains. Field or clinical isolates have the potential to reveal greater-than-suspected diversity in variable gene repertoires, which could be useful to design molecular probes for epidemiology studies.

One of the most interesting findings of our study was the occurrence of duplicated vpma loci in strain 5632. Because one vpma locus can express only a single vpma gene per cell, the consequences of such an event are tremendous in terms of variability because it allows concomitant expression and, in turn, multiplies the number of possible surface combinations. Our data suggest that this situation most likely resulted from the duplication of one 5632 vpma region at a remote chromosomal position (250 kbp away) and that it involves IS elements. The role of such mobile genetic elements in chromosomal shuffling of genes encoding major surface components may have important evolutionary and epidemiological consequences for pathogens, such as mycoplasmas, that have a reduced genome and no cell wall.

Finally, whether a successful vaccine strategy based on surface antigens could be developed for mycoplasmas is not known, but this would have to take into account the dynamics and scope of any variable antigen gene repertoires.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the French Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries and by the National Institute for Agricultural Research (INRA).

We thank F. Poumarat and the French National Network for Surveillance of Mycoplasmosis (AFSSA, Lyon, France, and VIGIMYC, France) for providing the strains. We also thank A. Blanchard for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 17 April 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baseman, J. B., and J. G. Tully. 1997. Mycoplasmas: sophisticated, reemerging, and burdened by their notoriety. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 321-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Behrens, A., M. Heller, H. Kirchhoff, D. Yogev, and R. Rosengarten. 1994. A family of phase- and size-variant membrane surface lipoprotein antigens (Vsps) of Mycoplasma bovis. Infect. Immun. 625075-5084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhugra, B., L. L. Voelker, N. Zou, H. Yu, and K. Dybvig. 1995. Mechanism of antigenic variation in Mycoplasma pulmonis: interwoven, site-specific DNA inversions. Mol. Microbiol. 18703-714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bordier, C. 1981. Phase separation of integral membrane proteins in Triton X-114 solution. J. Biol. Chem. 2561604-1607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carver, T. J., K. M. Rutherford, M. Berriman, M. A. Rajandream, B. G. Barrell, and J. Parkhill. 2005. ACT: the Artemis comparison tool. Bioinformatics 213422-3423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, C., J. Tang, W. Dong, C. Wang, Y. Feng, J. Wang, F. Zheng, X. Pan, D. Liu, M. Li, Y. Song, X. Zhu, H. Sun, T. Feng, Z. Guo, A. Ju, J. Ge, Y. Dong, W. Sun, Y. Jiang, J. Yan, H. Yang, X. Wang, G. F. Gao, R. Yang, and J. Yu. 2007. A glimpse of streptococcal toxic shock syndrome from comparative genomics of S. suis 2 Chinese isolates. PLoS ONE 2e315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, W. P., and T. T. Kuo. 1993. A simple and rapid method for the preparation of gram-negative bacterial genomic DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 212260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chopra-Dewasthaly, R., C. Citti, M. D. Glew, M. Zimmermann, R. Rosengarten, and W. Jechlinger. 2008. Phase-locked mutants of Mycoplasma agalactiae: defining the molecular switch of high-frequency Vpma antigenic variation. Mol. Microbiol. 671196-1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Citti, C., G. F. Browning, and R. Rosengarten. 2005. Phenotypic diversity and cell invasion in host subversion by pathogenic mycoplasmas, p. 439-484. In A. Blanchard and G. F. Browning (ed.), Mycoplasmas: molecular biology, pathogenicity and strategies for control. Horizon Bioscience, Norfolk, United Kingdom.

- 10.Citti, C., M. F. Kim, and K. S. Wise. 1997. Elongated versions of Vlp surface lipoproteins protect Mycoplasma hyorhinis escape variants from growth-inhibiting host antibodies. Infect. Immun. 651773-1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Citti, C., and R. Rosengarten. 1997. Mycoplasma genetic variation and its implication for pathogenesis. Wien Klin. Wochenschr. 109562-568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Citti, C., and K. S. Wise. 1995. Mycoplasma hyorhinis vlp gene transcription: critical role in phase variation and expression of surface lipoproteins. Mol. Microbiol. 18649-660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Denison, A. M., B. Clapper, and K. Dybvig. 2005. Avoidance of the host immune system through phase variation in Mycoplasma pulmonis. Infect. Immun. 732033-2039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flitman-Tene, R., S. Mudahi-Orenstein, S. Levisohn, and D. Yogev. 2003. Variable lipoprotein genes of Mycoplasma agalactiae are activated in vivo by promoter addition via site-specific DNA inversions. Infect. Immun. 713821-3830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frangeul, L., P. Glaser, C. Rusniok, C. Buchrieser, E. Duchaud, P. Dehoux, and F. Kunst. 2004. CAAT-box, contigs-assembly and annotation tool-box for genome sequencing projects. Bioinformatics 20790-797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glew, M. D., M. Marenda, R. Rosengarten, and C. Citti. 2002. Surface diversity in Mycoplasma agalactiae is driven by site-specific DNA inversions within the vpma multigene locus. J. Bacteriol. 1845987-5998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glew, M. D., L. Papazisi, F. Poumarat, D. Bergonier, R. Rosengarten, and C. Citti. 2000. Characterization of a multigene family undergoing high-frequency DNA rearrangements and coding for abundant variable surface proteins in Mycoplasma agalactiae. Infect. Immun. 684539-4548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heiner, C. R., K. L. Hunkapiller, S. M. Chen, J. I. Glass, and E. Y. Chen. 1998. Sequencing multimegabase-template DNA with BigDye terminator chemistry. Genome Res. 8557-561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horino, A., Y. Sasaki, T. Sasaki, and T. Kenri. 2003. Multiple promoter inversions generate surface antigenic variation in Mycoplasma penetrans. J. Bacteriol. 185231-242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hudson, P., T. S. Gorton, L. Papazisi, K. Cecchini, S. Frasca, Jr., and S. J. Geary. 2006. Identification of a virulence-associated determinant, dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase (lpd), in Mycoplasma gallisepticum through in vivo screening of transposon mutants. Infect. Immun. 74931-939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar, S., K. Tamura, and M. Nei. 2004. MEGA3: Integrated software for molecular evolutionary genetics analysis and sequence alignment. Brief Bioinform. 5150-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lartigue, C., J. I. Glass, N. Alperovich, R. Pieper, P. P. Parmar, C. A. Hutchison, III, H. O. Smith, and J. C. Venter. 2007. Genome transplantation in bacteria: changing one species to another. Science 317632-638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lysnyansky, I., Y. Ron, and D. Yogev. 2001. Juxtaposition of an active promoter to vsp genes via site-specific DNA inversions generates antigenic variation in Mycoplasma bovis. J. Bacteriol. 1835698-5708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lysnyansky, I., R. Rosengarten, and D. Yogev. 1996. Phenotypic switching of variable surface lipoproteins in Mycoplasma bovis involves high-frequency chromosomal rearrangements. J. Bacteriol. 1785395-5401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahillon, J., C. Leonard, and M. Chandler. 1999. IS elements as constituents of bacterial genomes. Res. Microbiol. 150675-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marenda, M. S., E. M. Vilei, F. Poumarat, J. Frey, and X. Berthelot. 2004. Validation of the suppressive subtractive hybridization method in Mycoplasma agalactiae species by the comparison of a field strain with the type strain PG2. Vet. Res. 35199-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neyrolles, O., I. Chambaud, S. Ferris, M. C. Prevost, T. Sasaki, L. Montagnier, and A. Blanchard. 1999. Phase variations of the Mycoplasma penetrans main surface lipoprotein increase antigenic diversity. Infect. Immun. 671569-1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Connor, L., A. Coffey, C. Daly, and G. F. Fitzgerald. 1996. AbiG, a genotypically novel abortive infection mechanism encoded by plasmid pCI750 of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris UC653. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 623075-3082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Connor, L., M. Tangney, and G. F. Fitzgerald. 1999. Expression, regulation, and mode of action of the AbiG abortive infection system of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris UC653. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65330-335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pettersson, B., M. Uhlen, and K. E. Johansson. 1996. Phylogeny of some mycoplasmas from ruminants based on 16S rRNA sequences and definition of a new cluster within the hominis group. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 461093-1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pilo, P., B. Fleury, M. Marenda, J. Frey, and E. M. Vilei. 2003. Prevalence and distribution of the insertion element ISMag1 in Mycoplasma agalactiae. Vet. Microbiol. 9237-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ron, Y., R. Flitman-Tene, K. Dybvig, and D. Yogev. 2002. Identification and characterization of a site-specific tyrosine recombinase within the variable loci of Mycoplasma bovis, Mycoplasma pulmonis and Mycoplasma agalactiae. Gene 292205-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosengarten, R., C. Citti, P. Much, J. Spergser, M. Droesse, and M. Hewicker-Trautwein. 2001. The changing image of mycoplasmas: from innocent bystanders to emerging and reemerging pathogens in human and animal diseases. Contrib. Microbiol. 8166-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosengarten, R., and K. S. Wise. 1990. Phenotypic switching in mycoplasmas: phase variation of diverse surface lipoproteins. Science 247315-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roske, K., A. Blanchard, I. Chambaud, C. Citti, J. H. Helbig, M. C. Prevost, R. Rosengarten, and E. Jacobs. 2001. Phase variation among major surface antigens of Mycoplasma penetrans. Infect. Immun. 697642-7651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rutherford, K., J. Parkhill, J. Crook, T. Horsnell, P. Rice, M. A. Rajandream, and B. Barrell. 2000. Artemis: sequence visualization and annotation. Bioinformatics 16944-945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 38.Sasaki, Y., J. Ishikawa, A. Yamashita, K. Oshima, T. Kenri, K. Furuya, C. Yoshino, A. Horino, T. Shiba, T. Sasaki, and M. Hattori. 2002. The complete genomic sequence of Mycoplasma penetrans, an intracellular bacterial pathogen in humans. Nucleic Acids Res. 305293-5300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shen, X., J. Gumulak, H. Yu, C. T. French, N. Zou, and K. Dybvig. 2000. Gene rearrangements in the vsa locus of Mycoplasma pulmonis. J. Bacteriol. 1822900-2908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simmons, W. L., A. M. Denison, and K. Dybvig. 2004. Resistance of Mycoplasma pulmonis to complement lysis is dependent on the number of Vsa tandem repeats: shield hypothesis. Infect. Immun. 726846-6851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sirand-Pugnet, P., C. Citti, A. Barre, and A. Blanchard. 2007. Evolution of mollicutes: down a bumpy road with twists and turns. Res. Microbiol. 158754-766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sirand-Pugnet, P., C. Lartigue, M. Marenda, D. Jacob, A. Barre, V. Barbe, C. Schenowitz, S. Mangenot, A. Couloux, B. Segurens, A. de Daruvar, A. Blanchard, and C. Citti. 2007. Being pathogenic, plastic, and sexual while living with a nearly minimal bacterial genome. PLoS Genet. 3e75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sitaraman, R., A. M. Denison, and K. Dybvig. 2002. A unique, bifunctional site-specific DNA recombinase from Mycoplasma pulmonis. Mol. Microbiol. 461033-1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tangney, M., and G. F. Fitzgerald. 2002. AbiA, a lactococcal abortive infection mechanism functioning in Streptococcus thermophilus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 686388-6391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tettelin, H., V. Masignani, M. J. Cieslewicz, C. Donati, D. Medini, N. L. Ward, S. V. Angiuoli, J. Crabtree, A. L. Jones, A. S. Durkin, R. T. Deboy, T. M. Davidsen, M. Mora, M. Scarselli, I. Margarit y Ros, J. D. Peterson, C. R. Hauser, J. P. Sundaram, W. C. Nelson, R. Madupu, L. M. Brinkac, R. J. Dodson, M. J. Rosovitz, S. A. Sullivan, S. C. Daugherty, D. H. Haft, J. Selengut, M. L. Gwinn, L. Zhou, N. Zafar, H. Khouri, D. Radune, G. Dimitrov, K. Watkins, K. J. O'Connor, S. Smith, T. R. Utterback, O. White, C. E. Rubens, G. Grandi, L. C. Madoff, D. L. Kasper, J. L. Telford, M. R. Wessels, R. Rappuoli, and C. M. Fraser. 2005. Genome analysis of multiple pathogenic isolates of Streptococcus agalactiae: implications for the microbial “pan-genome.” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10213950-13955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tully, J. G. 1995. Culture medium formulation for primary isolation and maintenance of mollicutes, p. 33-39. In J. G. Tully (ed.), Molecular and diagnostic procedures in mycoplasmology: molecular characterization. Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

- 47.van der Woude, M. W. 2006. Re-examining the role and random nature of phase variation. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 254190-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weisburg, W. G., J. G. Tully, D. L. Rose, J. P. Petzel, H. Oyaizu, D. Yang, L. Mandelco, J. Sechrest, T. G. Lawrence, J. Van Etten, J. Maniloff, and C. R. Woese. 1989. A phylogenetic analysis of the mycoplasmas: basis for their classification. J. Bacteriol. 1716455-6467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Westberg, J., A. Persson, A. Holmberg, A. Goesmann, J. Lundeberg, K. E. Johansson, B. Pettersson, and M. Uhlen. 2004. The genome sequence of Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. mycoides SC type strain PG1T, the causative agent of contagious bovine pleuropneumonia (CBPP). Genome Res. 14221-227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wise, K. S. 1993. Adaptive surface variation in mycoplasmas. Trends Microbiol. 159-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Woese, C. R. 1987. Bacterial evolution. Microbiol. Rev. 51221-271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.