Abstract

Cells infected by viruses utilize interferon (IFN)-mediated and p53-mediated irreversible cell cycle arrest and apoptosis as part of the overall host surveillance mechanism to ultimately block viral replication and dissemination. Viruses, in turn, have evolved elaborate mechanisms to subvert IFN- and p53-mediated host innate immune responses. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) encodes several viral IFN regulatory factors (vIRF1 to vIRF4) within a cluster of loci, their functions being primarily to inhibit host IFN-mediated innate immunity and deregulate p53-mediated cell growth control. Despite its significant homology and similar genomic location to other vIRFs, vIRF4 is distinctive, as it does not target and antagonize host IFN-mediated signal transduction. Here, we show that KSHV vIRF4 interacts with the murine double minute 2 (MDM2) E3 ubiquitin ligase, leading to the reduction of p53, a tumor suppressor, via proteasome-mediated degradation. The central region of vIRF4 is required for its interaction with MDM2, which led to the suppression of MDM2 autoubiquitination and, thereby, a dramatic increase in MDM2 stability. Consequently, vIRF4 expression markedly enhanced p53 ubiquitination and degradation, effectively suppressing p53-mediated apoptosis. These results indicate that KSHV vIRF4 targets and stabilizes the MDM2 E3 ubiquitin ligase to facilitate the proteasome-mediated degradation of p53, perhaps to circumvent host growth surveillance and facilitate viral replication in infected cells. Taken together, the indications are that the downregulation of p53-mediated cell growth control is a common characteristic of the four KSHV vIRFs and that p53 is indeed a key factor in the host's immune surveillance program against viral infections.

Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) was discovered in 1996 through the infectious etiology of KS and has since been implicated in KS, primary effusion lymphoma, and multicentric Castleman's disease (5, 35). Additionally, KSHV is classified as human herpesvirus 8 in the genus Rhadinovirus of the subfamily Gammaherpesvirinae (30). Like other herpesviruses, KSHV is a large, double-stranded DNA virus that establishes a lifelong persistent infection in the host (29). To efficiently establish persistent infection, KSHV dedicates a large portion of its genome to encoding immunomodulatory proteins that antagonize the immune system of the host. These viral immunomodulators have been shown to regulate different aspects of innate and adaptive immune responses, with most having cellular protein homologues. They have been shown to engage the cellular signaling pathway, oversee cell proliferation, and modulate apoptosis (6, 7, 36).

Interferon (IFN) regulatory factors (IRFs) are a well-characterized family of immunomodulatory proteins that regulate the IFN pathway, irreversible cell cycle arrest, and apoptosis in response to viral infections. KSHV encodes four viral IRF (vIRF) genes, which are homologous to cellular IRFs, in a cluster of loci between open reading frame 57 and open reading frame 58 of the viral genome (8, 38). KSHV vIRF1 (K9), vIRF2 (K11.1), and vIRF3 (K10.5) have previously been cloned and functionally characterized, but little is known about vIRF4 (K10). However, the expression of vIRF4 can be induced by 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA), suggesting that vIRF4 belongs to a family of lytic proteins and is expressed mainly in the nucleus (19, 20). Although vIRF4 has been poorly studied to this point, the other vIRFs have been shown to carry out two major biological functions. First, the vIRFs inhibit host IFN-mediated innate immunity. vIRF1 inhibits IRF3-mediated transcriptional activation through the sequestration of p300/CBP (3, 23, 24), vIRF2 inhibits the transactivation of IRF1 and IRF3 (12), and vIRF3 binds to IRF7 to suppress IRF7-mediated IFN-α production (18). Second, the vIRFs deregulate the tumor suppressor activity of p53. vIRF1 interacts with the ATM kinase to block its activity, thereby reducing p53 phosphorylation at the serine 15 residue and increasing p53 ubiquitination (40). Additionally, vIRF1, in conjunction with vIRF3, interacts with p53 to inhibit its transcriptional activation (39). These studies have demonstrated that the two vIRF proteins listed above comprehensively inhibit p53, a tumor suppressor, with this inhibition being one of the mechanisms used by host cells to prevent the survival and replication of virally infected cells.

p53, which also serves as a transcriptional factor, responds to DNA damage and other cellular stresses, such as viral infections, by inducing the arrest of the cell cycle or apoptosis and plays a critical role in tumor suppression. It has been well established that murine double minute 2 (MDM2) is the major negative regulator of p53, yet the mechanism by which MDM2 regulates the tumor-suppressing activity of p53 remains poorly understood. The prevailing view is that MDM2 suppresses p53 through the following pair of mechanisms: (i) MDM2 binds to and masks p53's N-terminal transactivation domain (TA), directly interfering with p53's ability to recruit the basal transcription machinery (17), and (ii) MDM2 acts as a RING-finger E3 ubiquitin ligase of p53 to promote the ubiquitin-mediated degradation of p53 (10). Additionally, when expressed at high levels, MDM2 gains the ability of autoubiquitination.

To further delineate the role of vIRF4 in the viral immune evasion strategy, we examined the potential effects of vIRF4 on p53-mediated cell growth control. Here, we show that KSHV vIRF4 interacts with MDM2 and that this interaction specifically suppresses MDM2 ubiquitination, resulting in enhanced p53 ubiquitination. Remarkably, the central region of vIRF4 is required to interact with MDM2 as well as stabilize it. As a consequence, the central region of vIRF4 is necessary for the degradation of p53 and the inhibition of p53-mediated apoptosis. This suggests that, similar to vIRF1 and vIRF3, vIRF4 downregulates p53-mediated host immune surveillance against viral infections. These results strongly indicate that KSHV has evolved mechanisms to affect p53-mediated irreversible cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, which are parts of the host surveillance mechanism against viral infections and tumorigenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and transfection reagents.

293T and HCT116 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco-BRL). Tetracycline-inducible TREx/BCBL-1 cells have been previously described (31) and were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco-BRL). Transient transfections were performed with FuGENE 6 (Roche) or calcium phosphate (Clontech) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Plasmid construction.

All constructs for transient and stable expression in mammalian cells were derived from the expression vectors pcDNA4/V5-His, pcDNA/FRT/To-Hygro, pEF-IRES-Puro, or pBabe-Puro. DNA fragments corresponding to the coding sequence of the wild-type (WT) vIRF4 gene were amplified from template DNA (provided by Jürgen Hass) by PCR analysis and subcloned into pcDNA4/V5-His at the restriction sites EcoRI and NotI, into pcDNA/FRT/To-Hygro at BamHI and NotI, into pEF-IRES-Puro at EcoRI and XbaI, or into pBabe-Puro at BamHI and EcoRI. V5-tagged vIRF4 was expressed from a modified pIRES-Puro and pcDNA, both of which encode a C-terminal V5 tag. Several vIRF4 mutants were generated via PCR analysis. All constructs were sequenced using an ABI Prism 377 automatic DNA sequencer to verify 100% correspondence with the original sequence. The V5-tagged vIRF1 was cloned into the pEF-IRES-Puro vector (40).

Construction of cell lines.

To establish KSHV-infected BCBL-1 cells expressing WT or mutant vIRF4 in a tetracycline-inducible manner, pcDNA/FRT/To-vIRF4/Au or pcDNA/FRT/To-vIRF4 (1-605)/Au was transfected via electroporation along with the pOG44 Flp recombinase expression vector. Twenty-four hours after electroporation, cells were selected using 200 μg/ml of hygromycin B (Invitrogen) for 3 weeks. The detailed procedure has been previously described (30). HCT116 cells were transfected with pBabe-Puro, pBabe-vIRF4/V5, or pBabe-vIRF4 (1-605)/V5 and then selected using 2 μg/ml of puromycin (Sigma).

Reagents and chemicals.

The appropriate cells were treated with 20 μg/ml of cycloheximide (CHX; Sigma), 25 μM of LLNL (Sigma), 1 μg/ml of doxycycline (Dox; Sigma), 20 ng/ml of TPA (Sigma), 20 μM of etoposide (Sigma), and 400 μM of 5-fluorouracil (5-Fu; Sigma) for the indicated time periods.

Immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation.

For immunoblotting, polypeptides were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Bio-Rad). The membranes were blocked using 5% nonfat milk and then probed with the antibodies indicated below. Immunodetection was achieved by using a chemiluminescence reagent (Pierce) and a Fuji phosphorimager (BAS-1500; Fuji Film Co., Tokyo, Japan). For immunoprecipitation, cells were harvested and then lysed in 1% NP-40 lysis buffer supplemented with complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). After preclearing using protein A/G agarose beads for 1 h at 4°C, whole-cell lysates were used for immunoprecipitation with the antibodies indicated below. Generally, 1 to 4 μg of a commercial antibody was added to 1 ml of the cell lysate and incubated at 4°C for 3 h. After adding the protein A/G agarose beads, incubation was continued for an additional 2 h. Immunoprecipitates were extensively washed using 1% NP-40 lysis buffer and eluted by boiling for 5 min in an SDS-PAGE loading buffer. The primary antibodies were purchased from the following sources: p53 (DO-1), MDM2 (SMP14), and ubiquitin (P4D1) antibodies from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, actin antibody from Abcam, tubulin antibody from Sigma, Au antibody from Covance, V5 antibody from Bethyl Laboratories, Inc., and viral interleukin-6 (vIL-6) antibody from Advanced Biotechnologies. The K8, vIRF-1, latency-associated nuclear antigen, and K1 antibodies have been previously described (21, 31).

Apoptosis analysis.

HCT116 and TREx/BCBL-1 cells stably expressing WT or mutant forms of vIRF4 were seeded into 1 × 106 cells and cultured for 24 h. The cells were then treated with fresh medium containing two apoptosis-inducing reagents for up to 24 h. To perform the apoptosis assay, the cells were collected and washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline and then incubated in annexin V binding buffer (Invitrogen) containing 5 μl annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate and 10 μl propidium iodide (PI; 50 mg/liter) for 15 min at room temperature. Fluorescence emitted from the annexin V and PI signal was measured using FACScan flow cytometry. Cells containing positive annexin V and negative PI signals were considered to be apoptotic. Data was analyzed using Cell Quest (BD Biosciences).

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR).

Total RNAs were extracted by using TRI Reagent (Sigma) and then reverse transcribed by the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad), with the resultant cDNAs used to amplify MDM2 or p53. Real-time PCR analysis was performed using Sybr green-based detection methods in a CFX96 real-time system (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Actin was used as a normalization control.

RESULTS

vIRF4 interacts with MDM2.

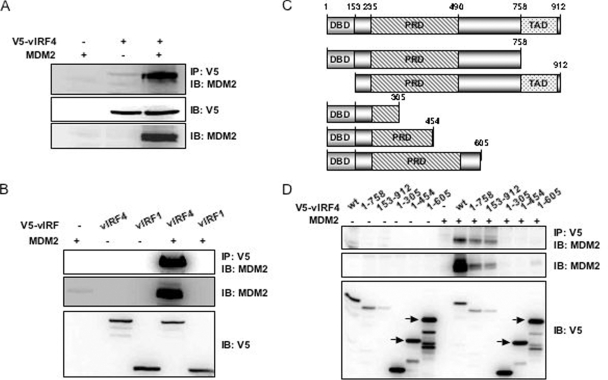

Since the KSHV vIRF1 and vIRF3 genes are functionally redundant in deregulating p53-mediated tumor suppressor activity, we investigated the potential interactions of vIRF4 with a number of cellular proteins involved in the p53 pathway. Among cellular proteins, MDM2 was found to specifically interact with vIRF4. 293T cells were transfected with V5-vIRF4 or MDM2 individually, as well as in combination. At 48 h posttransfection, the cells were lysed with a 1% NP-40 detergent and used for immunoprecipitation with an anti-V5 antibody. Proteins present in the anti-V5 immune complexes were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and exposed to an anti-MDM2 antibody. We show here that vIRF4 strongly interacts with MDM2 and robustly increases MDM2 protein levels (Fig. 1A). Additionally, endogenous MDM2-vIRF4 interaction was readily detected in anti-V5 immune complexes, as well as vIRF4 alone (Fig. 1A, lane 2). To confirm the specificity of the interaction between vIRF4 and MDM2, we expressed MDM2 alone and coexpressed MDM2 with V5-vIRF4 or V5-vIRF1 in 293T cells. Coimmunoprecipitation showed that MDM2 specifically bound to vIRF4 but not vIRF1 (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

The central region of vIRF4 is required for MDM2 interaction. (A) Coimmunoprecipitation (Co-IP) of MDM2 with vIRF4 (WT). 293T cells were transiently transfected with the indicated constructs, followed by immunoprecipitation (IP) with an anti-V5 antibody and immunoblotting (IB) with an anti-MDM2 antibody. (B) Co-IP of MDM2 with vIRF4 (WT) or vIRF1 (WT). 293T cells were transfected MDM2 and the indicated vIRF4 or vIRF1 constructs, followed by IP with an anti-V5 antibody and IB with an anti-MDM2 antibody. One percent of the whole-cell lysates (WCL) was used as the input. (C) Schematic representation of the plasmid constructs. (D) Co-IP of MDM2 with the WT or several vIRF4 mutants. 293T cells were transfected with the indicated vIRF4 constructs along with MDM2, followed by IP with an anti-V5 antibody and IB with an anti-MDM2 antibody. One percent of the WCL was used as the input.

The amino terminus of vIRF4 exhibits a significant level of homology to the amino-terminal DNA-binding domain and TA of cellular IRFs. However, the central region of vIRF4 is not homologous to the cellular IRFs. Moreover, this region contains 14 repeats of a proline-rich P(X)2-3P motif. To determine the region of vIRF4 required for its interaction with MDM2, we constructed a series of vIRF4 deletion mutants (Fig. 1C). To demonstrate the expression of these deletion mutants, whole-cell lysates were used for immunoblot analyses with an anti-V5 antibody after transfection into 293T cells. vIRF4 (WT) and the vIRF4 deletion mutants were expressed at various yet comparable levels (Fig. 1D). These same cell lysates were then used for immunoprecipitation with an anti-V5 antibody, followed by immunoblotting to detect associations with MDM2 (Fig. 1D). The experiments demonstrate that the 606 to 758 amino acid region of vIRF4 is necessary to interact with and stabilize MDM2, whereas the amino-terminal DNA-binding domain and the carboxyl-terminal transactivation domain are not (Fig. 1D and see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Although it is difficult to discern MDM2 expression from the whole-cell lysates obtained from the transfection of MDM2 alone, data shown in Fig. 1B and D strongly support the assertion that vIRF4 stabilizes MDM2 by interacting with it.

vIRF4-MDM2 binding reduces MDM2 ubiquitination.

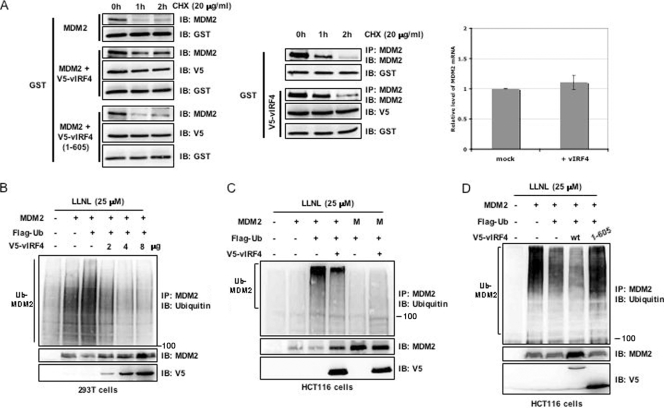

From our binding data, we found that the MDM2 protein accumulates when it is cotransfected with vIRF4 but not when it is cotransfected with vIRF1 (Fig. 1B and D). To clarify the mechanisms by which vIRF4 increases MDM2 stability, 293T cells were transfected with MDM2 alone or cotransfected with MDM2 along with V5-vIRF4 (WT) or V5-vIRF4 (1-605), followed by exposure of the cells to 20 μg/ml of CHX, a protein synthesis inhibitor. When vIRF4 (WT) was overexpressed, the half-life of the MDM2 protein was longer than when MDM2 alone or a vIRF4 (1-605) mutant that no longer interacted with MDM2 was overexpressed (Fig. 2A, left). To rule out the possibility that vIRF4 randomly stabilizes proteins, we included a mammalian glutathione S-transferase (GST) protein. These results showed that vIRF4 (WT) was unable to stabilize GST, showing that MDM2 stabilization via vIRF4 is a specific event. Furthermore, vIRF4 expression increased the half-life of endogenous MDM2 in 293T cells without significantly affecting MDM2 mRNA levels (Fig. 2A, middle and right). These results also indicate that the stabilization of MDM2 by vIRF4 is dependent on vIRF4 interaction.

FIG. 2.

vIRF4 augments MDM2 stability by suppressing the ubiquitination of MDM2. (A) An increase in the stability of MDM2 is induced by vIRF4. (A, left) After transfection with MDM2, GST, and an empty vector or MDM2, GST, and vIRF4 (WT or mutant), cells were treated with CHX (20 μg/ml) for the indicated periods of time, and then immunoblotted (IB) with anti-MDM2 antibody. (A, middle) At 48 h posttransfection with GST and/or vIRF4, 293T cells were treated with CHX (20 μg/ml) for the indicated periods of time. Whole-cell lysates (WCL) were used for immunoprecipitation (IP) or IB with the indicated antibodies. (A, right) At 48 h posttransfection of 293T cells with vIRF4 or mock transfection, total RNAs were prepared and MDM2 mRNA levels were analyzed by qRT-PCR. (B and C) Effects of vIRF4 on the ubiquitination of MDM2. 293T (B) or HCT116 (C) cells were cotransfected with the indicated vIRF4 constructs along with MDM2 and ubiquitin constructs. The cells were then treated with LLNL (25 μM), followed by IP with an anti-MDM2 antibody and IB with an anti-ubiquitin antibody. One percent of the WCL was used as the input. M, MDM2 (C464A) mutant that no longer possesses E3 ligase activity. (D) MDM2 accumulation is dependent on vIRF4 interaction. HCT116 cells were cotransfected with MDM2, ubiquitin, and the WT or mutant forms of vIRF4. The cells were then treated with LLNL (25 μM), followed by IP with an anti-MDM2 antibody and IB with an anti-ubiquitin antibody. One percent of the WCL was used as the input.

MDM2 possesses E3 ubiquitin ligase activity to mediate its autoubiquitination as well as the ubiquitination of other substrates, including p53 (10, 15-17). Given that the stability of MDM2 is determined primarily by its intrinsic autoubiquitination activities, we postulated that vIRF4 might increase the stability of MDM2 by inhibiting its autoubiquitination. To investigate this, 293T cells were transfected with different combinations of vIRF4, MDM2, and ubiquitin, followed by incubation in the presence of LLNL, a proteasome inhibitor, for an additional 4 h. To enrich the total amount of the MDM2 protein so that polyubiquitinated species could be readily detected, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-MDM2 antibody and resolved on an SDS-PAGE gel, followed by immunoblotting with an anti-ubiquitin antibody. Consistent with its autoubiquitination activity, MDM2 expression resulted in a significant increase of its ubiquitination (Fig. 2B, lanes 2 and 3). In contrast, vIRF4 expression significantly reduced MDM2 ubiquitination levels in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2B, lanes 4 to 6).

To ascertain that vIRF4 is able to inhibit the autoubiquitination of MDM2, we engineered a Cys-to-Ala substitution of C464, the zinc-coordinating residue of the MDM2 gene. This mutation has been shown to abolish the E3 ubiquitin ligase activity of MDM2 without affecting its binding to p53 (13). Therefore, if vIRF4 stabilizes MDM2 by inhibiting its autoubiquitination, then an MDM2 mutant (C464A) lacking ubiquitin ligase activity should not be stabilized by vIRF4. For this, we utilized HCT116 cells containing an active form of p53 rather than 293T cells, which contain the simian virus 40 (SV40) T antigen that inactivates p53 (14). HCT116 cells were cotransfected with plasmids encoding vIRF4 and a Flag-tagged ubiquitin along with WT or mutant MDM2, and the levels of ubiquitin-MDM2 conjugates were analyzed after using LLNL to inhibit proteasome activity. As shown in Fig. 2C, vIRF4 expression did not significantly affect MDM2 (C464A) mutant levels while markedly increasing the MDM2 (WT) levels under identical conditions.

Given that vIRF4 readily prolonged the half-life of MDM2 through their interaction, we examined whether this activity was related to the ubiquitination of MDM2. To investigate the effects of MDM2-vIRF4 interaction on MDM2 ubiquitination levels, we compared the levels of MDM2 autoubiquitination elicited by vIRF4 (WT) and the vIRF4 (1-605) mutant. HCT116 cells were cotransfected with plasmids encoding MDM2 and Flag-tagged ubiquitin along with the WT or mutant vIRF4, and the levels of ubiquitin-MDM2 conjugates were analyzed by using LLNL to inhibit proteasome activity. As shown in Fig. 2D, vIRF4 (WT) reduced the relative levels of ubiquitin-MDM2 conjugates (Fig. 2D, lane 4), but the vIRF4 mutant deficient for MDM2 binding did not (Fig. 2D, lane 5), indicating that vIRF4 interaction is necessary to block the ubiquitination of MDM2. Taken together, these results show that vIRF4 apparently regulates the stability of MDM2 by modulating its ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation.

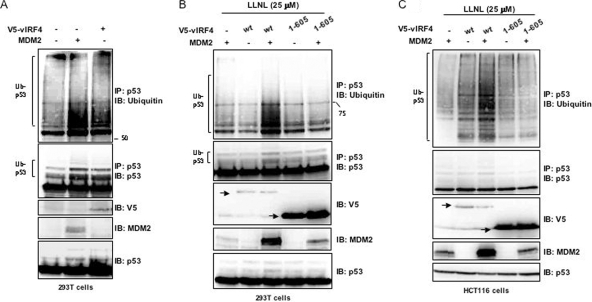

vIRF4 enhances p53 ubiquitination.

It has been well characterized that MDM2 possesses the ability to degrade p53 (15, 27). Given that vIRF4 interacts with MDM2 through its central region to induce MDM2 stabilization, we investigated whether the stabilization of MDM2 influenced the MDM2-mediated ubiquitination of p53. 293T cells expressing MDM2 or vIRF4 were examined for their p53 ubiquitination levels. While ubiquitinated p53 was readily detectable in the absence of either MDM2 or vIRF4 expression, expression of either of them significantly increased p53 ubiquitination (Fig. 3A). To further evaluate whether the increased p53 ubiquitination was due to increased MDM2 stabilization induced by its interaction with vIRF4, 293T or HCT116 cells were transfected with expression vectors encoding vIRF4 (WT), the vIRF4 (1-605) mutant, and MDM2, with the ubiquitin-conjugated p53 then immunoprecipitated using an anti-p53 antibody (DO-1). A low level of ubiquitinated p53 was detected in the presence of LLNL (Fig. 3B and C, lanes 1, 2, and 4), and when MDM2 was coexpressed with vIRF4 (WT), the ubiquitination of p53 increased dramatically (Fig. 3B and C, lane 3). However, when MDM2 was coexpressed with the vIRF4 (1-605) mutant, ubiquitinated p53 levels did not change (Fig. 3B and C, lane 5). These results indicate that the stabilization of MDM2 induced by vIRF4 interaction ultimately promotes p53 ubiquitination.

FIG. 3.

vIRF4 enhances the ubiquitination of p53 through its interaction with MDM2. (A) The effects of vIRF4 and MDM2 on the ubiquitination of p53. 293T cells were transfected with vIRF4 or MDM2, followed by immunoprecipitation (IP) with an anti-p53 antibody and immunoblotting (IB) with an anti-ubiquitin antibody. One percent of the whole-cell lysates (WCL) was used as the input. (B and C) Effects of vIRF4-MDM2 interaction on the ubiquitination of p53. 293T (B) or HCT116 (C) cells were cotransfected with the vIRF4 constructs along with the MDM2 and ubiquitin constructs. Cells were then treated with LLNL (25 μM), followed by IP with an anti-MDM2 antibody and IB with an anti-ubiquitin antibody. One percent of the WCL was used as the input.

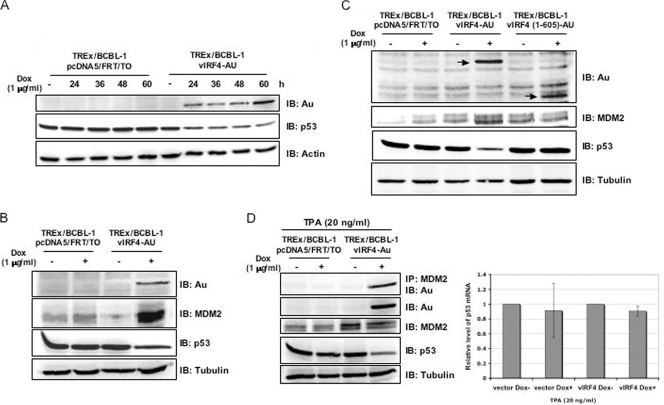

vIRF4 reduces p53 protein levels in KSHV-infected cells.

Since p53 plays a critical role in the host's surveillance of viral infections, we examined the potential effect of vIRF4 on the stability of p53. To do this, carboxyl-terminal Au-tagged vIRF4 was ectopically expressed in BCBL-1 cells infected with KSHV in a tetracycline-inducible manner, as previously described (31). These cells were designated as TREx/BCBL-1 vIRF4. To assess the ability of vIRF4 to regulate the expression of p53, TREx/BCBL-1 vIRF4 cells were treated with 1 μg/ml of Dox (serving as a stand-in for tetracycline) for various periods of time and harvested for immunoblot analyses with antibodies against Au and p53. The vIRF4 protein was induced in TREx/BCBL-1 vIRF4 cells upon treatment with Dox, and its expression was detectable within 24 h after treatment (Fig. 4A). Under these conditions, endogenous p53 levels were examined by immunoblotting with an anti-p53 antibody. This showed that the amount of p53 decreased considerably in TREx/BCBL-1 vIRF4 cells when vIRF4 levels were increased (Fig. 4A). In contrast, a reduction of p53 protein levels was not observed in the control, TREx/BCBL-1 pcDNA5/FRT/To, under identical conditions (Fig. 4A). Since vIRF4 stabilizes MDM2 to enhance the ubiquitination of p53, we investigated whether vIRF4 affected the stabilization of MDM2 in virus-infected cells. TREx/BCBL-1 pcDNA5/FRT/To and TREx/BCBL-1 vIRF4 cells were treated with or without 1 μg/ml of Dox for 24 h. Upon Dox treatment, MDM2 was readily detectable at low levels in TREx/BCBL-1 pcDNA5/FRT/To, whereas it was detected at much higher levels in TREx/BCBL-1 vIRF4 cells (Fig. 4B). In addition to the augmentation of MDM2 protein levels, the amount of p53 in TREx/BCBL-1 vIRF4 cells was reduced (Fig. 4B). To correlate the interaction of vIRF4 and MDM2 with the stabilization of MDM2 and the reduction of p53, we then evaluated p53 and MDM2 protein levels in TREx/BCBL-1 vIRF4 (1-605) cells upon treatment with Dox. Unlike vIRF4 (WT), vIRF4 (1-605) mutant expression did not lead to MDM2 stabilization or p53 degradation in TREx/BCBL-1 vIRF4 (1-605) cells (Fig. 4C). To further delineate the effects of vIRF4-MDM2 interaction on p53 levels, TREx/BCBL-1 pcDNA5/FRT/To and TREx/BCBL-1 vIRF4 cells were treated with 20 ng/ml TPA in the presence or absence of Dox. The results showed efficient interaction between vIRF4 and endogenous MDM2 (Fig. 4D). Furthermore, the increase of endogenous MDM2 induced by vIRF4 led to the decrease of endogenous p53 (Fig. 4D). It should be noted that an increased amount of MDM2 was also detected in TREx/BCBL-1 vIRF4 cells untreated by Dox, which may be due to the leaky, low level of expression of vIRF4 under these conditions (Fig. 4D, left). Furthermore, qRT-PCR analysis showed that p53 mRNA levels remained unchanged upon vIRF4 expression (Fig. 4D, right). Collectively, these results indicate that vIRF4 expression significantly downregulates p53 protein expression through its interaction with MDM2.

FIG. 4.

vIRF4 downregulates p53 protein levels in stable cell lines and interacts with endogenous MDM2 during viral reactivation. (A) p53 expression in Dox-induced TREx/BCBL-1 vIRF4 cells. Upon stimulation with Dox (1 μg/ml), equal amounts of the total proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting (IB) with an anti-p53 antibody at the indicated times. An anti-actin antibody was used to monitor general protein levels, while an anti-Au antibody was used to monitor vIRF4 expression. (B and C) The expression levels of p53 and MDM2 in Dox-induced TREx/BCBL-1 vIRF4 cells and Dox-induced TREx/BCBL-1 vIRF4 (1-605) cells were compared. Twenty-four hours after stimulation with Dox (1 μg/ml), equal amounts of the total proteins were analyzed by IB with anti-p53 and anti-MDM2 antibodies. An anti-tubulin antibody was used to monitor general protein levels, while an anti-Au antibody was used to monitor vIRF4 protein expression. (D, left) At 24 h posttreatment of TREx/BCBL-1 pcDNA5/FRT/TO and TREx/BCBL-1 vIRF4 cells with TPA (20 ng/ml) and/or Dox (1 μg/ml), equal amounts of the total proteins were used for immunoprecipitation (IP) and IB with the indicated antibodies. One percent of the whole-cell lysates was used as the input. An anti-tubulin antibody was used to monitor general protein levels. (D, right) At 24 h posttreatment with TPA (20 ng/ml) and/or Dox (1 μg/ml), total RNAs were isolated from TREx/BCBL-1 pcDNA/FRT/TO and TREx/BCBL-1 vIRF4 cells and the p53 mRNA levels were analyzed by qRT-PCR. Vector, TREx/BCBL-1 pcDNA5/FRT/To cells; vIRF4, TREx/BCBL-1 vIRF4 cells.

vIRF4 expression enhances p53 ubiquitination and downregulates p53-mediated apoptosis in KSHV-infected cells.

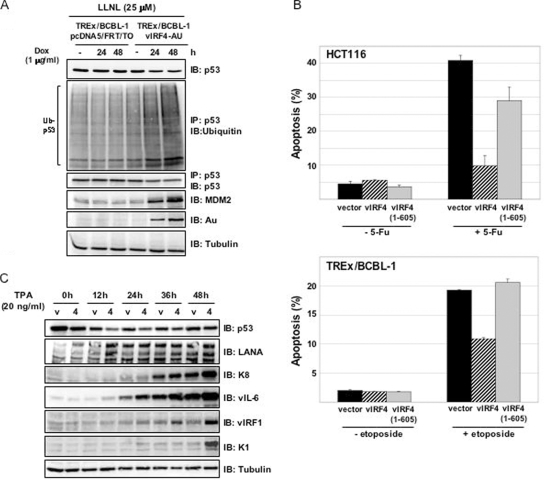

To further understand how vIRF4 decreases p53 protein levels in TREx/BCBL-1 vIRF4 cells, we evaluated p53 ubiquitination levels upon vIRF4 induction for different periods of time. TREx/BCBL-1 pcDNA5/FRT/To and TREx/BCBL-1 vIRF4 cells were incubated with or without Dox for various periods of time, followed by treatment with LLNL for 4 h. After harvesting, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-p53 antibody, followed by immunoblotting with an anti-ubiquitin antibody. The p53 ubiquitination levels in TREx/BCBL-1 vIRF4 cells were detectably higher than those in TREx/BCBL-1 pcDNA5/FRT/To control cells (Fig. 5A, lanes 1 and 4). Additionally, increasing amounts of vIRF4 led to increased MDM2 protein levels and decreased p53 protein levels (Fig. 5A).

FIG. 5.

vIRF4 enhances the ubiquitination of p53 in stable cell lines. (A) Effects of vIRF4 expression on the ubiquitination of p53 in stable cell lines. Upon stimulation with Dox (1 μg/ml), cells were also treated with LLNL (25 μM) for 4 h before being harvested at the indicated times. Cells lysates were then used for immunoprecipitation (IP) with an anti-p53 antibody, followed by immunoblotting (IB) with an anti-ubiquitin antibody. An anti-tubulin antibody was used to monitor general protein levels, while an anti-Au antibody was used to monitor vIRF4 protein expression. (B) vIRF4 protects cells from apoptosis induced by two different DNA damage reagents. (B, top) HCT116 cells stably expressing the WT or mutant forms of vIRF4 were treated with 5-FU for 24 h and then assessed for annexin V and PI staining, followed by FACS analysis. (B, bottom) TREx/BCBL-1 cells stably expressing the WT or mutant forms of vIRF4 via stimulation with Dox (1 μg/ml) were treated with etoposide for 24 h and then assessed for annexin V and PI staining, followed by FACS analysis. Data represent the means (±SD) of the combined results from three independent experiments. (C) At the indicated times after stimulation with TPA (20 ng/ml), equal amounts of the total proteins were analyzed by IB with KSHV-specific antibodies. An anti-tubulin antibody was used to monitor general protein levels. V, TREx/BCBL-1 pcDNA5/FRT/To cells; 4, TREx/BCBL-1 vIRF4 cells. Similar results were obtained from three independent experiments.

A tumor suppressor, p53, regulates cell cycle arrest and apoptosis (1, 2). To examine the biological consequences of accelerated p53 degradation by vIRF4, we compared the abilities of vIRF4 (WT) and the vIRF4 (1-605) mutant in inhibiting p53-mediated apoptosis. Three HCT116 stable cell lines [HCT116-pBabe, HCT116-pBabe vIRF4, and HCT116-pBabe vIRF4 (1-605)] and three TREx/BCBL-1 stable cell lines [TREx/BCBL-1 pcDNA5/FRT/To, TREx/BCBL-1 vIRF4, and TREx/BCBL-1 vIRF4 (1-605)] were used for this study. HCT116 cells were treated with 5-Fu for 24 h, after which annexin V and PI staining were performed to determine apoptosis levels via flow cytometry. Expression of vIRF4 (WT) decreased 5-Fu-induced apoptosis levels in HCT116 cells, whereas the vIRF4 (1-605) mutant did not (Fig. 5B, top). TREx/BCBL-1 cells were treated with etoposide for 24 h, after which annexin V and PI staining were performed to determine apoptosis levels via flow cytometry. Etoposide effectively induced p53-mediated apoptosis in TREx/BCBL-1 cells, with the apoptosis levels detectably reduced upon vIRF4 (WT) expression. In contrast, expression of the vIRF4 (1-605) mutant had little or no effect on apoptosis (Fig. 5B, bottom). These results suggest that vIRF4 stabilizes MDM2, resulting in the enhanced degradation of p53 and the suppression of p53-dependent apoptosis.

To assess the effects of the vIRF4-mediated downregulation of p53 on KSHV viral protein expression, TREx/BCBL-1 pcDNA5/FRT/To and TREx/BCBL-1 vIRF4 cells were treated with TPA for the periods of time indicated above, with equal amounts of polypeptides used for immunoblotting with a variety of antibodies. This showed that the levels of the early lytic vIRF1 and the delayed-early lytic K1 proteins were considerably higher in TREx/BCBL-1 vIRF4 cells than in TREx/BCBL-1 pcDNA5/FRT/To cells. Additionally, marginal increases in the K8 and vIL-6 immediate-early lytic proteins were detected in TREx/BCBL-1 vIRF4 cells compared to the K8 and vIL-6 protein levels present in TREx/BCBL-1 pcDNA5/FRT/To cells (Fig. 5C). In contrast, the viral latency-associated nuclear antigen and cellular tubulin remained at equivalent levels in these cells under identical conditions (Fig. 5C). These data demonstrate that vIRF4 markedly downregulates p53 protein levels, which may result in favorable circumstances for viral propagation.

DISCUSSION

Upon viral infection, IFN and the tumor suppressor p53 are the major molecules employed by host cells as components of their antiviral defense mechanisms. Thus, there exists a need for viruses to tightly regulate these antiviral surveillance mechanisms of the host, which KSHV accomplishes through the use of various immunomodulatory proteins (7). These include vIRF1 and vIRF3, which act upon IFN-mediated antiviral activity and inhibit the p53-mediated tumor suppressor activity of the host (32). Here, we report that KSHV vIRF4 prevents MDM2 self-ubiquitination, thereby stabilizing MDM2. Consequently, vIRF4 downregulates p53 protein levels by enhancing the ubiquitination of p53, ultimately inhibiting p53-mediated apoptosis. Our studies suggest that the inhibition of p53 activity induced by the KSHV vIRFs is important to the virus in establishing and/or maintaining persistent infection.

We show that vIRF4 downregulates p53 protein levels by facilitating its ubiquitination and degradation. This activity is dependent on the stabilization of MDM2, which is mediated by vIRF4. MDM2 possesses E3 ligase activity, which mediates its autoubiquitination as well as the ubiquitination of other substrates, including p53 (10, 16, 17). There are several potential mechanisms which may explain how vIRF4 contributes to MDM2 stability. First, MDM2 stabilizes its own protein levels through posttranslational modifications, such as sumoylation and phosphorylation. Sumoylation protects MDM2 from proteasomal degradation by competing with ubiquitin at its major conjugation site, Lys 464 (4), while the phosphorylation of MDM2 prevents it from self-ubiquitination, thereby stabilizing MDM2 (9, 11). Second, the deubiquitination enzymes HAUSP and USP2a have been shown to directly bind and remove ubiquitin molecules from MDM2, resulting in its stabilization (2, 26, 41). Third, other MDM2 binding partners may block the E3 ligase activity of MDM2 toward itself. For example, the MDM2 binding protein MTBP reduces the autoubiquitination of MDM2 and stabilizes it (1). As seen with MTBP, vIRF4 significantly suppresses MDM2 self-ubiquitination in a binding-dependent manner (Fig. 2). Additional studies are necessary to identify the particular mode of the vIRF4-mediated stabilization of MDM2.

Recent studies have shown that MDM2 is capable of inducing both the monoubiquitination and polyubiquitination of p53. When MDM2 levels are low, it catalyzes the monoubiquitination of p53 to export it from the nucleus for degradation and/or further modification in the cytoplasm. Conversely, when MDM2 levels are high, p53 is polyubiquitinated inside the nucleus and is subsequently degraded by nuclear proteasomes. MDM2 is generally considered to function as an ubiquitin E3 ligase to promote its self-degradation as well as the degradation of p53 (22, 33). Thus, the MDM2-p53 autoregulatory negative-feedback loop, wherein p53 induces MDM2 expression while MDM2 represses p53 activity and requires tight regulation to fine-tune p53 function (28, 42). Our data show that the stabilization of MDM2 by vIRF4, indicated by a high level of MDM2, significantly enhances p53 polyubiquitination (Fig. 3). These results suggest that vIRF4 likely regulates the ubiquitin ligase activity of MDM2 toward itself but not toward p53. Furthermore, this implies that vIRF4 may physically protect the sites of MDM2 ubiquitination by interacting with MDM2 while leaving the E3 ligase activity of MDM2 toward p53 intact. Similarly, vIRF4 enhances the stabilization of MDM2 while increasing the ubiquitination of p53, with vIRF4 downregulating p53 protein levels in KSHV-infected cells (Fig. 4 and 5). Importantly, this effect is closely associated with vIRF4-MDM2 interaction, given that the MDM2 noninteractive vIRF4 (1-605) mutant lost this function (Fig. 3 to 5). MDM2-induced p53 degradation was dramatically increased in KSHV-infected TREx/BCBL-1 cells upon vIRF4 expression (Fig. 5A), strongly suggesting a novel function for vIRF4 in downregulating p53 protein levels. p53 normally functions as an integrator stress response signal by activating or repressing the transcription of genes that regulate cell cycle progression and/or apoptosis (25, 34), and indeed, vIRF4 readily inhibits p53-mediated apoptosis (Fig. 5B). Therefore, the stabilization of MDM2 by vIRF4 may lead to the repression of p53 without shifting the negative feedback loop toward MDM2. Subsequently, the downregulation of p53 protein levels resulted in efficient viral gene expression during viral replication (Fig. 5C).

In summary, our studies have identified KSHV vIRF4 as a novel MDM2-interacting protein. vIRF4 inhibits MDM2 self-ubiquitination and stabilizes its protein levels, enhancing the MDM2-mediated degradation of p53. Especially, KSHV encodes a cluster of four viral homologues of cellular IRFs, vIRF1 to vIRF4. vIRF1 binds to p53 to suppresses its phosphorylation and acetylation, which increases p53 ubiquitination and downregulates p53 protein levels (24, 39, 40). vIRF3 also binds to p53 and blocks its ability to enhance transcription and induce apoptosis (37). Additionally, we report here that vIRF4 reduces MDM2 ubiquitination, thus inhibiting the p53-mediated apoptosis mediated by p53 ubiquitination. The fact that these three forms of the vIRFs suppress p53 protein stability and/or transcriptional activity in distinctive manners to deregulate p53 tumor suppressor-mediated growth control indicates that the inhibition of p53 function by the vIRFs is important for maintaining persistent infections and developing virus-associated malignancies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Korea Research Foundation Grant, which is funded by the Korean government (MOEHRD, Basic Research Promotion Fund; KRF-2006-352-C00074), as well as by CA082057, CA115284, a Hastings Foundation grant, and DE019085 (J.U.J.).

We thank Jürgen Hass for providing the reagent and Michelle Connole for the fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis. Finally, we thank all lab members for their support and discussions.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 15 April 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brady, M., N. Vlatkovic, and M. T. Boyd. 2005. Regulation of p53 and MDM2 activity by MTBP. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25545-553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brooks, C. L., M. Li, M. Hu, Y. Shi, and W. Gu. 2007. The p53-Mdm2-HAUSP complex is involved in p53 stabilization by HAUSP. Oncogene 267262-7266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burýsek, L., W. S. Yeow, B. Lubyova, M. Kellum, S. L. Schafer, Y. Q. Huang, and P. M. Pitha. 1999. Functional analysis of human herpesvirus 8-encoded viral interferon regulatory factor 1 and its association with cellular interferon regulatory factors and p300. J. Virol. 737334-7342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buschmann, T., S. Y. Fuchs, C. G. Lee, Z. Q. Pan, and Z. Ronai. 2000. SUMO-1 modification of Mdm2 prevents its self-ubiquitination and increases Mdm2 ability to ubiquitinate p53. Cell 101753-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang, Y., E. Cesarman, M. S. Pessin, F. Lee, J. Culpepper, D. M. Knowles, and P. S. Moore. 1994. Identification of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma. Science 2661865-1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collot-Teixeira, S., J. Bass, F. Denis, and S. Ranger-Rogez. 2004. Human tumor suppressor p53 and DNA viruses. Rev. Med. Virol. 14301-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coscoy, L. 2007. Immune evasion by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7391-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cunningham, C., S. Barnard, D. J. Blackbourn, and A. J. Davison. 2003. Transcription mapping of human herpesvirus 8 genes encoding viral interferon regulatory factors. J. Gen. Virol. 841471-1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D'Arcy, P., W. Maruwge, B. A. Ryan, and B. Brodin. 2008. The oncoprotein SS18-SSX1 promotes p53 ubiquitination and degradation by enhancing HDM2 stability. Mol. Cancer Res. 6127-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fang, S., J. P. Jensen, R. L. Ludwig, K. H. Vousden, and A. M. Weissman. 2000. Mdm2 is a RING finger-dependent ubiquitin protein ligase for itself and p53. J. Biol. Chem. 2758945-8951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng, J., R. Tamaskovic, Z. Yang, D. P. Brazil, A. Merlo, D. Hess, and B. A. Hemmings. 2004. Stabilization of Mdm2 via decreased ubiquitination is mediated by protein kinase B/Akt-dependent phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 27935510-35517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fuld, S., C. Cunningham, K. Klucher, A. J. Davison, and D. J. Blackbourn. 2006. Inhibition of interferon signaling by the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus full-length viral interferon regulatory factor 2 protein. J. Virol. 803092-3097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geyer, R. K., Z. K. Yu, and C. G. Maki. 2000. The MDM2 RING-finger domain is required to promote p53 nuclear export. Nat. Cell Biol. 2569-573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hahn, W. C., and R. A. Weinberg. 2002. Modelling the molecular circuitry of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2331-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haupt, Y., R. Maya, A. Kazaz, and M. Oren. 1997. Mdm2 promotes the rapid degradation of p53. Nature 387296-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Honda, R., H. Tanaka, and H. Yasuda. 1997. Oncoprotein MDM2 is a ubiquitin ligase E3 for tumor suppressor p53. FEBS Lett. 42025-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Honda, R., and H. Yasuda. 2000. Activity of MDM2, a ubiquitin ligase, toward p53 or itself is dependent on the RING finger domain of the ligase. Oncogene 191473-1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joo, C. H., Y. C. Shin, M. Gack, L. Wu, D. Levy, and J. U. Jung. 2007. Inhibition of interferon regulatory factor 7 (IRF7)-mediated interferon signal transduction by the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus viral IRF homolog vIRF3. J. Virol. 818282-8292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanno, T., Y. Sato, T. Sata, and H. Katano. 2006. Expression of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-encoded K10/10.1 protein in tissues and its interaction with poly(A)-binding protein. Virology 352100-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katano, H., Y. Sato, T. Kurata, S. Mori, and T. Sata. 2000. Expression and localization of human herpesvirus 8-encoded proteins in primary effusion lymphoma, Kaposi's sarcoma, and multicentric Castleman's disease. Virology 269335-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee, B. S., M. Connole, Z. Tang, N. L. Harris, and J. U. Jung. 2003. Structural analysis of the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus K1 protein. J. Virol. 778072-8086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li, M., C. L. Brooks, F. Wu-Baer, D. Chen, R. Baer, and W. Gu. 2003. Mono- versus polyubiquitination: differential control of p53 fate by Mdm2. Science 3021972-1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li, M., H. Lee, J. Guo, F. Neipel, B. Fleckenstein, K. Ozato, and J. U. Jung. 1998. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus viral interferon regulatory factor. J. Virol. 725433-5440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin, R., P. Genin, Y. Mamane, M. Sgarbanti, A. Battistini, W. J. Harrington, Jr., G. N. Barber, and J. Hiscott. 2001. HHV-8 encoded vIRF-1 represses the interferon antiviral response by blocking IRF-3 recruitment of the CBP/p300 coactivators. Oncogene 20800-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meek, D. W. 1999. Mechanisms of switching on p53: a role for covalent modification? Oncogene 187666-7675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meulmeester, E., M. M. Maurice, C. Boutell, A. F. Teunisse, H. Ovaa, T. E. Abraham, R. W. Dirks, and A. G. Jochemsen. 2005. Loss of HAUSP-mediated deubiquitination contributes to DNA damage-induced destabilization of Hdmx and Hdm2. Mol. Cell 18565-576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Michael, D., and M. Oren. 2003. The p53-Mdm2 module and the ubiquitin system. Semin. Cancer Biol. 1349-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moll, U. M., and O. Petrenko. 2003. The MDM2-p53 interaction. Mol. Cancer Res. 11001-1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moore, P. S., and Y. Chang. 2003. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus immunoevasion and tumorigenesis: two sides of the same coin? Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57609-639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moore, P. S., and Y. Chang. 2001. Molecular virology of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 356499-516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakamura, H., M. Lu, Y. Gwack, J. Souvlis, S. L. Zeichner, and J. U. Jung. 2003. Global changes in Kaposi's sarcoma-associated virus gene expression patterns following expression of a tetracycline-inducible Rta transactivator. J. Virol. 774205-4220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Offermann, M. K. 2007. Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus-encoded interferon regulator factors. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 312185-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poyurovsky, M. V., and C. Prives. 2006. Unleashing the power of p53: lessons from mice and men. Genes Dev. 20125-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prives, C., and P. A. Hall. 1999. The p53 pathway. J. Pathol. 187112-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Renne, R., W. Zhong, B. Herndier, M. McGrath, N. Abbey, D. Kedes, and D. Ganem. 1996. Lytic growth of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) in culture. Nat. Med. 2342-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rezaee, S. A., C. Cunningham, A. J. Davison, and D. J. Blackbourn. 2006. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus immune modulation: an overview. J. Gen. Virol. 871781-1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rivas, C., A. E. Thlick, C. Parravicini, P. S. Moore, and Y. Chang. 2001. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus LANA2 is a B-cell-specific latent viral protein that inhibits p53. J. Virol. 75429-438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Russo, J. J., R. A. Bohenzky, M. C. Chien, J. Chen, M. Yan, D. Maddalena, J. P. Parry, D. Peruzzi, I. S. Edelman, Y. Chang, and P. S. Moore. 1996. Nucleotide sequence of the Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (HHV8). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9314862-14867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seo, T., J. Park, D. Lee, S. G. Hwang, and J. Choe. 2001. Viral interferon regulatory factor 1 of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus binds to p53 and represses p53-dependent transcription and apoptosis. J. Virol. 756193-6198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shin, Y. C., H. Nakamura, X. Liang, P. Feng, H. Chang, T. F. Kowalik, and J. U. Jung. 2006. Inhibition of the ATM/p53 signal transduction pathway by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus interferon regulatory factor 1. J. Virol. 802257-2266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stevenson, L. F., A. Sparks, N. Allende-Vega, D. P. Xirodimas, D. P. Lane, and M. K. Saville. 2007. The deubiquitinating enzyme USP2a regulates the p53 pathway by targeting Mdm2. EMBO J. 26976-986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stommel, J. M., and G. M. Wahl. 2005. A new twist in the feedback loop: stress-activated MDM2 destabilization is required for p53 activation. Cell Cycle 4411-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.