Abstract

The role of the medial basal hypothalamus (MBH) and the anterior hypothalamus/preoptic area (AH/POA) in sleep regulation was investigated using the Halász knife technique to sever MBH anterior and lateral projections in rats. If both lateral and anterior connections of the MBH were cut, rats spent less time in non-rapid eye movement sleep (NREMS) and rapid eye movement sleep (REMS). In contrast, if the lateral connections remained intact, the duration of NREMS and REMS was normal. The diurnal rhythm of NREMS and REMS was altered in all groups except the sham control group. Changes in NREMS or REMS duration were not detected in a group with pituitary stalk lesions. Water consumption was enhanced in three groups of rats, possibly due to the lesion of vasopressin fibers entering the pituitary. EEG delta power during NREMS and brain temperatures (Tbr) were not affected by the cuts during baseline or after sleep deprivation. In response to 4 h of sleep deprivation, only one group, that with the most anterior-to-posterior cuts, failed to increase its NREMS or REMS time during the recovery sleep. After deprivation, Tbr returned to baseline in most of the treatment groups. Collectively, results indicate that the lateral projections of the MBH are important determinants of duration of NREMS and REMS, while more anterior projections are concerned with the diurnal distribution of sleep. Further, the MBH projections involved in sleep regulation are distinct from those involved in EEG delta activity, water intake, and brain temperature.

Keywords: anterior hypothalamus/preoptic area, sleep regulation, non-rapid eye movement sleep

a relationship between the somatotropic axis and sleep was first recognized 40 years ago when the association between plasma growth hormone (GH) levels and non-rapid eye movement sleep (NREMS) was described by Takahashi et al. (77). Subsequently, much evidence has supported the hypothesis that hypothalamic growth hormone releasing hormone (GHRH) is involved in NREMS sleep regulation and, through its induction of pituitary release of GH, rapid eye movement sleep (REMS) as well (reviewed in Ref. 55). Within the hypothalamus, the majority of the GHRH-containing perikarya resides in the arcuate nucleus (ARC) (50, 51, 66). A smaller number of GHRH-containing neurons are found around the ventral border of the ventromedial nucleus, the dorsomedial nucleus, and in the parvocellular portion of the paraventricular nucleus (PVN), and the posterior hypothalamus. Previously, we showed that microinjection of GHRH into the medial preoptic region/anterior hypothalamus promotes NREMS, while injection of a GHRH antagonist peptide inhibited NREMS (80). The stimulated areas likely included the rostral portion of the periventricular (PeV) nucleus due to diffusion. Sites in the posterior hypothalamus were not tested. We posited that the extra-arcuate GHRHergic neurons were the source of the sleep-promoting GHRHergic projections because it had been demonstrated that sleep deprivation increases GHRH mRNA expression in the PVN, and diurnal variations in GHRH mRNA occurred in the periventromedial neurons (78). However, the number of GHRH-containing neurons is far larger inside than outside the ARC, and there are observations suggesting that intra-arcuate neurons, including GHRH-containing neurons, may project to various nuclei in the hypothalamus, in addition to the median eminence (ME) (22, 50, 63, 66). If monosodium glutamate is used to destroy the ARC in neonate rats, NREMS is decreased when the animals are adults (58). Collectively, such data suggest that the ARC also contributes to the sleep-promoting GHRHergic projections in the hypothalamus. Herein, we examine the significance of the connections between the mediobasal hypothalamus (MBH), the neuroendocrine area that contains the ARC, and the rostral forebrain [anterior hypothalamus, preoptic area (AH/POA)] in sleep regulation. We report that by using a Halász knife to make anterior and anterolateral isolations of the MBH, duration of NREMS and its distribution across the day in rats are altered, thereby, suggesting a role of ARC GHRHergic neurons in sleep regulation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (body weights 330–400 g) were used. They were acclimated to a 12:12-h light-dark cycle (light cycle starting at 0930). Experimental procedures followed institutional guidelines for the care and use of research animals and were approved by the institutional committees. The experiments are also consistent with the “Guiding Principles for Research Involving Animals and Human Beings” issued by the American Physiological Society (3).

The rats were housed individually in Plexiglas chambers for at least 2 wk before the experiments began, and during which they reached the desired body weights. Food and water were available ad libitum during the whole course of the experiment. The ambient temperature was set at 26 ± 1°C.

Surgery

The rats were anesthetized with ketamine-xylazine (87 and 13 mg/kg, respectively). Six groups of rats with different MBH isolations were prepared (Table 1). Hypothalamic cuts were made with a Halász-type knife (radius: 1.6 mm, height: 2.0 mm) as described earlier (46, 47). The rats were placed into a stereotaxic apparatus (Kopf Instruments) with the incisor bar lowered −6.5 mm. The skull was uncovered, the surface of the bone was cleared and sterilized with 70% ethanol. A piece of bone (about 2 mm wide and 6 mm long) was removed from the midline of the skull. The knife then was inserted into the brain in the midline behind the bregma (59). First, the knife was moved backward (posterior to bregma −1.8 mm), then was lowered carefully with the tip of the knife blade in the front, until it touched the base of the skull. In this setting the knife was turned 90° to both sides, and in this lateral position, the knife was moved further backward -2.5 mm on each side, elongating the lateral separation. This group of rats was called anterolateral cut group (ALC) (Fig. 1). Another group of rats was prepared using the same coordinates, but this group was cut only unilaterally: unilateral ALC (UALC). Half of the UALC rats were cut on the left, and half were cut on the right side of the hypothalamus (n = 3 left; n = 3 right; total: n = 6). For the ACmid group, the knife was pulled backward and lowered as in the ALC group, and then it was rotated 180° (90–90° on each side) in the hypothalamus. In the ACmid group, in contrast to the ALC group, the cut was not elongated caudally (Fig. 1). The knife was lowered into the brain at a more posterior position at −2.3 mm posterior to bregma (Fig. 1). The ACpost group was prepared in the same way as the ACmid group, except the knife was lowered into the brain −2.8 mm posterior to bregma and the rotation was 180° (Fig. 1). For the pituitary stalk lesion (PSL) group, the knife was lowered into the brain at −4.2 mm posterior to bregma, and the pituitary stalk was lesioned by a 180° cut (Fig. 1). Sham operation was performed with a knife blade in the front, lowered at −1.8 mm posterior to bregma until it reached the skull bone at the bottom; no rotation of the knife was performed. The rats were provided with cortical stainless-steel screw electroencephalogram (EEG) electrodes, and a thermistor to record brain temperature (Tbr) (60). Motor activity was determined from signals generated in electromagnetic transducers activated by the movements of the recording cable (60).

Table 1.

Summary of experimental groups and conditions with sample sizes

| Group Name |

Baseline Day Recording |

Sleep Deprivation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | NREMS | REMS | SWA | Tbr | ||

| ALC | n=15 | n=17 | n=17 | n=17 | n=8 | n=8 |

| UALC | n=6 | n=6 | n=6 | n=6 | n=6 | |

| ACmid | n=8 | n=6 | n=6 | n=6 | n=6 | n=5 |

| ACpost | n=8 | n=6 | n=6 | n=8 | n=8 | n=8 |

| PSL | n=16 | n=11 | n=11 | n=11 | n=8 | n=8 |

| Sham | n=18 | n=24 | n=24 | n=11 | n=12 | n=7 |

ALC, anterolateral cut; UALC, unilateral anterolateral cut; ACmid, anterior cut, 2.3 mm posterior to bregma; ACpost, anterior cut, 2.8 mm posterior to bregma; PSL, pituitary stalk lesion; NREMS, non-rapid eye movement sleep; REMS, rapid eye movement sleep; SWA, slow-wave activitiy; Tbr, cortical brain temperature.

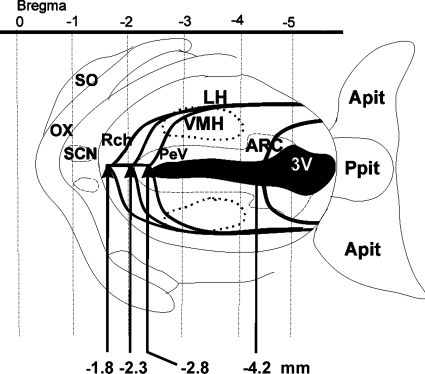

Fig. 1.

Schematic line drawing illustrates the design of different Halász's knife isolations. Microknife isolations started at −1.8 mm from bregma in the case of the bilateral anterolateral cut (ALC) and unilateral-anterolateral cut (UALC) isolation groups. Mid-anterior cut (ACmid) started at −2.3 mm posterior from bregma and the posterior-anterior cut (ACpost) started at −2.8 mm posterior from bregma. Pituitary stalk lesion (PSL) cuts started at −4.2 mm posterior to bregma. When the tip of the knife reached the base of the skull the knife was rotated 90° to both sides in the case of the ALC, ACmid, ACpost, and PSL isolation groups. In the case of the ALC group, cuts were further elongated backward in the lateral direction. The UALC group of rats were prepared using the same procedure as the ALC group, but this group was cut only unilaterally (either left or right side). Other isolation groups were not elongated backward in the lateral direction. 3V, third ventricle; Apit, anterior pituitary; ARC, arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus; DMH, dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus; LH, lateral hypothalamus; ox, optic chiasm; PeV, periventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus; Ppit, posterior pituitary; Rch, retrochiasmatic area; SCN, suprachiasmatic nucleus; SO, supraoptic nucleus; VMH, ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus.

Recording

Seven days after surgery, rats were connected to the recording cables that were attached to electronic commutators (Plastics One, Roanoke, VA, USA). The rats were free to move around and were habituated to the experimental conditions for 1 wk. Wires from commutators and electromagnetic transducers were connected to amplifiers (filtered below 0.1 and above 30 Hz) in an adjacent room. The signals were digitized (64-Hz sampling rate) and collected by a computer and stored on compact discs. For determination of sleep-wake states, the EEG, Tbr, and motor activity signals were used for visual scoring on a computer screen. Power density values were calculated by fast Fourier transformation for consecutive 8-s epochs in the frequency range between 0.25 and 20 Hz. The power density spectra were also displayed on the computer screen as an aid for scoring the records for sleep/wake epochs. The stages of vigilance were determined over 8-s epochs by the usual criteria as NREMS (high-amplitude EEG slow waves, high delta power, lack of body movements, and declining Tbr on entry), REMS (regular theta activity in the EEG, general lack of body movements with occasional twitches, and a rapid rise in Tbr at onset), and wakefulness (EEG activities similar to those in REM sleep but often less regular and with lower theta power; frequent body movements, and a gradual increase in Tbr after arousal). The time spent in each vigilance state for 1-h periods was determined. Mean power density spectra were calculated for all 8-s uninterrupted periods of artifact-free NREMS in each hour. Tbr values obtained every 8 s were averaged for 1-h periods. These values were, in turn, used to calculate mean Tbr during daylight and dark periods. The power density values for the 0.5–4.0 Hz (delta) frequency range during NREMS were integrated (10) and used as an index of EEG slow-wave activity (SWA) to characterize sleep intensity in each recording hour.

Sleep Deprivation and Water Intake Measurements

The EEG, Tbr, and motor activity (movements of the recording cable) were continuously displayed on computer monitors and recorded during sleep deprivation (SD) for visual surveillance and after SD when recovery sleep was allowed. To deprive rats of sleep, they were aroused by means of gentle stimuli (knocking on the cage, stirring the bedding) when either behavioral or EEG signs of sleep appeared. Rats were not disturbed during feeding, drinking, and grooming. The records were scored in 8-s epochs. During SD, the rats slept less than 1 min/h. Every group of rats was subjected to SD except the UALC group (Table 1).

Experimental Protocol

Water intake was measured on three consecutive days directly before the EEG recording started. EEG, motor activity, and Tbr were recorded for three consecutive days (12 h light and 11 h dark period with 1 h off on each day) to determine baseline values. On day 4 rats were sleep deprived for 4 h, and then while continuously recording, they were left undisturbed for the next 19 h.

Histology

For the verification of the knife cuts, the rats were killed under deep ketamine-xylazine anesthesia (180 and 27 mg/kg, respectively) and were transcardially perfused with 0.9% physiological saline followed by 5% formalin, 1% picric acid fixative solution. Brains and pituitaries were carefully removed from the skull and embedded in Histoplast (SERVA Electrophoresis, Heidelberg, Germany). These blocks of brains were serially sectioned in the coronal plane at 10 μm of thickness. Every fifth section was mounted and stained with the Bock & Brinkmann method for neurosecretory material (11). The evaluation of the sections was performed on coded slides by an individual without the knowledge of the group treatment and sleep results. Those animals that had incomplete cuts, e.g., the knife did not reach the bottom of the skull, were excluded from the experiment and are not included in the N values shown in Table 1.

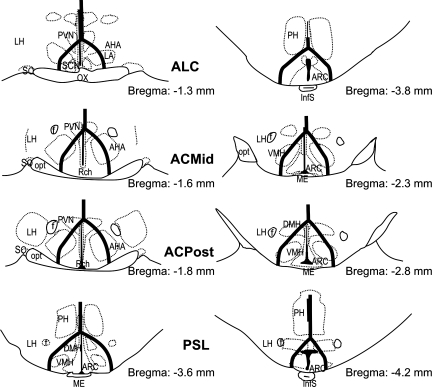

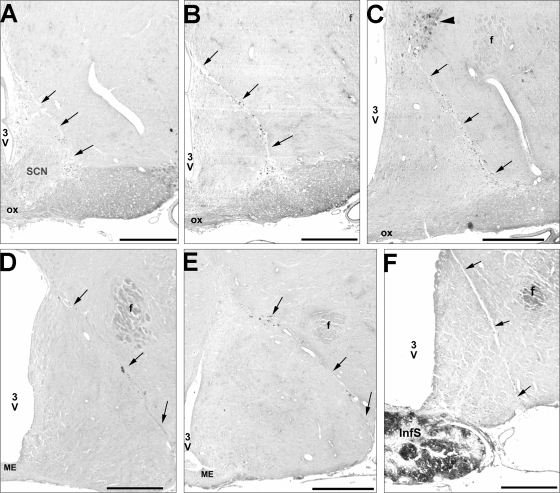

The cuts began in the middle of the optic chiasm (OX) at −1.30 mm and ended bilaterally at −3.80 mm after the separation of the pituitary stalk in the case of the ALC group (Figs. 2 and 3A). The UALC group of rats showed the same cut characteristics as the ALC group, but cuts were restricted to one side of the hypothalamus. In the case of the ACmid and ACpost groups, the cuts started at the second half of the OX at the starting point of the retrochiasmatic area (Rch) (−1.30) or at the posterior edge of the OX (−1.60), respectively (Figs. 2 and 3, B and C). Cuts ended in the middle of the ME in the ACmid group (−1.80) and in the posterior ME, just before the separation of the pituitary stalk (Figs. 2 and 3E) in the ACpost group (−2.30). The rats with PSL had a cut beginning before (−3.60) and ending (−4.16) after the separation of the pituitary stalk (Figs. 2, 3, E and F). The cuts beginning around the middle portion of the OX were around 1 mm wide from the midline at the level of Rch; while more posteriorly, the cut ran under the fornix, but included the ARC, PeV, ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus, and parts of the dorsomedial nucleus. In a few cases, the lateral part of the SCN was unilaterally or bilaterally excluded or lesioned by the knife cuts.

Fig. 2.

Schematic line drawing represents the Halász's knife isolations observed on the sections stained with the Bock and Brinkmann method. Left: beginning of the isolations in the different treatment groups. Right: end of the isolations in the different treatment groups. Numbers show the distance of the section relative to bregma at the right bottom of each section. AHA, anterior hypothalamic area; ARC, arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus; DMH, dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus; f, fornix; InfS, infundibular stem; LA, lateroanterior hypothalamic nucleus; LH, lateral hypothalamus; ME, median eminence; opt, optic tract; ox, optic chiasm; PH, posterior hypothalamus; PVN, paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus; Rch, retrochiasmatic area; SCN, suprachiasmatic nucleus; SO, supraoptic nucleus; VMH, ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus.

Fig. 3.

A series of bright-field photomicrographs illustrating the localization of different Halász-knife isolations. A: example of the beginning of the isolation in the case of the ALC group at −1.3 mm posterior to bregma (this is also the starting level of the UALC group). B: beginning of the isolation group ACmid at −1.6 posterior to bregma. C: beginning level of the isolation group ACpost at bregma −1.8. Solid arrowhead shows strong granular staining of the magnocellular part of the paraventricular nucleus outside the isolation area. D: termination level of the ACmid isolation group at around bregma -2.3 mm. E: termination level of the isolation ACpost at bregma −2.8 mm. F: termination point of the ALC isolation group just after bregma −3.8 mm. Black arrows are pointing to the isolation cuts on each picture. 3V, third ventricle; f, fornix; ME, median eminence; ox, optic chiasm; SCN, suprachiasmatic nucleus. Scale bar = 500 μm.

Statistical Analyses

For statistical analysis, averaged values obtained from different groups on baseline days were compared using one-way ANOVA followed by Student-Newman-Keuls method (SNK) to determine differences between the treatment groups for duration of NREMS and REMS, EEG delta wave power during NREMS (SWA), Tbr, and water consumption (Table 2). Averages of total sleep time; light and dark periods were determined and compared across the six experimental groups including the control group of rats. As described above, water consumption values were measured on three consecutive days. These values were averaged and analyzed with one-way ANOVA followed by the SNK test to determine differences of the 24-h water consumption.

Table 2.

Effects of different hypothalamic isolation on nonrapid eye movement sleep

| Groups |

NREMS |

REMS

|

Tbr, °C

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

% Recording time |

% Recording time

|

|||||||

| Light | Dark | Total (23 h) | Light | Dark | Total (23 h) | Light | Dark | |

| ALC | 44.8±1.38* | 28.1±1.40* | 36.4±0.84* | 6.4±0.52* | 7.3±0.62 | 6.8±0.38* | 36.1±0.04 | 36.4±0.09 |

| UALC | 62.1±1.41 | 29.7±1.35* | 45.9±1.08* | 9.7±0.67 | 7.1±0.50 | 8.4±042 | 36.0±0.05 | 36.7±0.07 |

| ACmid | 52.9±1.57* | 29.7±2.29* | 41.3±0.95 | 9.0±0.63* | 6.8±0.65 | 7.9±0.35 | 35.9±0.13 | 36.3±0.17 |

| ACpost | 50.9±1.95* | 26.4±2.29 | 38.6±1.40 | 7.0±1.00* | 6.7±0.59 | 6.8±0.46* | 36.1±0.13 | 36.6±0.26 |

| PSL | 60.5±0.85 | 22.0±1.16 | 41.2±0.94 | 10.5±0.94 | 5.3±0.64 | 7.9±0.50 | 35.9±0.05 | 36.6±0.08 |

| Sham | 61.7±0.47 | 21.0±0.85 | 41.3±0.50 | 11.8±0.43 | 5.4±0.31 | 8.6±0.20 | 36.0±0.04 | 36.8±0.06 |

Values are expressed as means ± SE of NREMS and REMS percent recording times; and °C in the case of Tbr, during the 12-h-light and the 12-h dark period of the baseline recording. Significant difference between the treatment (hypothalamic isolation) and the control sham-operated group of rats (Student-Newman-Keuls test following ANOVA; P < 0.05).

To evaluate the effects of knife cuts on diurnal rhythm, light-dark ratios of NREMS and REMS were calculated by dividing 12-h averaged light values with 11-h averaged dark values. We performed a Chi-square (χ2) test, in which the observed values were the light-dark ratios and the expected values were set to 1. For the case in which light-dark ratios are 1, the light values are equal with dark values. Significant variation from 1 indicates the presence of a diurnal rhythm.

Data (hourly values of the states of vigilance, SWA during NREMS, and Tbr) were compared by two-way ANOVA for repeated measures followed by the SNK test to evaluate the effect of SD to the baseline recording days with treatment as factor 1 and time as factor 2 from hour 5 to hour 23 for each vigilance state, EEG SWA, and Tbr. Sample sizes varied slightly in the individual tests because a few records and samples were lost or omitted for technical reasons. In particular, the UALC group was not included in the SD experiment. An α level of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant in all statistical tests used herein.

RESULTS

Comparisons of Measured Parameters Between Groups on Baseline Days

Water consumption on the baseline days.

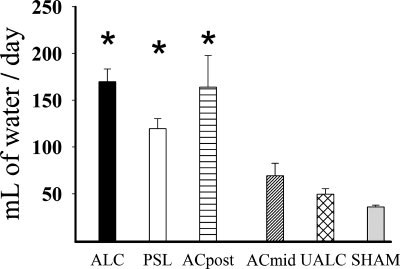

One-way ANOVA indicated there were significant differences in water consumption between groups [F(5,65) = 19.107, P < 0.001]. The SNK test indicated that rats in the ALC, PSL, and ACpost groups drank significantly more water than rats in the other groups (P < 0.001 for all comparisons) (Fig. 4). These effects were large; rats in these groups drank about three times as much water as the other groups. The other groups (ACmid, UALC) were not significantly different from the sham group or each other.

Fig. 4.

Bar graph shows daily water consumption values (means ± SE) in different treatment and the control (sham) groups. *Statistically significant changes compared with the control (SHAM) group of rats P < 0.05.

Sleep changes on the baseline days of recording.

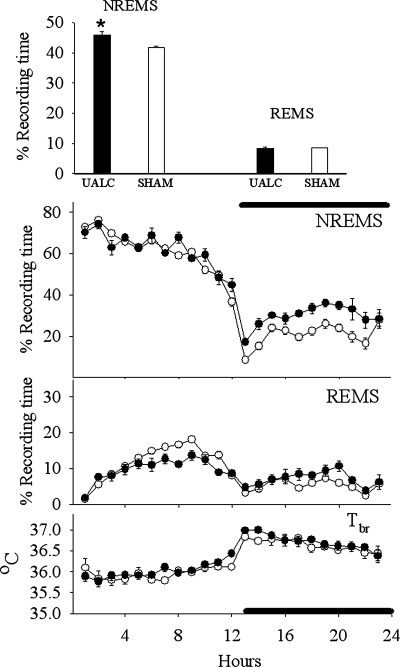

Analyses of duration of NREMS during the entire 23-h period indicated there were significant group affects: group [F(5,66) = 11.014, P < 0.001]. The ALC group (Fig. 5) had significantly (P < 0.001) less NREMS than the sham group, while the UALC group (Fig. 6) had significantly (P = 0.002) more NREMS than the sham group.

Fig. 5.

Effects of the ALC isolation on sleep [rapid eye movement sleep (REMS), non-REM sleep (NREMS), electroencephalogram (EEG) slow-wave activity during NREMS (SWA) and cortical brain temperature (Tbr)] during 23 h of recording period. Measured values were averaged and depicted as means ± SE in the case of the NREMS, REMS, and the Tbr. Percent differences are represented between baseline day and sleep deprivation day values for SWA (bar graph). Solid symbols (including bars) show the ALC group values, and open symbols show the sham-operated control values. Baseline values of NREMS, REMS, and Tbr are indicated by circles, whereas triangles indicate responses to 4 h of sleep deprivation (beginning at the light onset).

Fig. 6.

Effects of the UALC isolation on sleep [rapid eye movement sleep (REMS), non-REM sleep (NREMS), and cortical brain temperature (Tbr)] during 23 h of recording period. Only baseline values of NREMS, REMS, and Tbr are indicated; values are depicted as means ± SE. Top: averaged NREMS and REMS values during the total 23 h of recording period. *Statistically significant changes compared with the control (sham) group of rats P < 0.05.

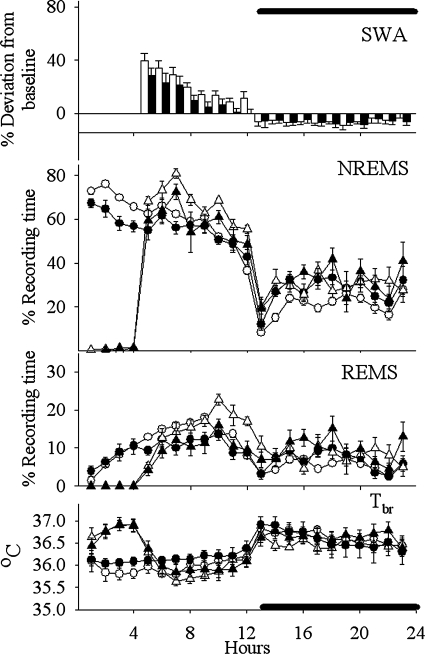

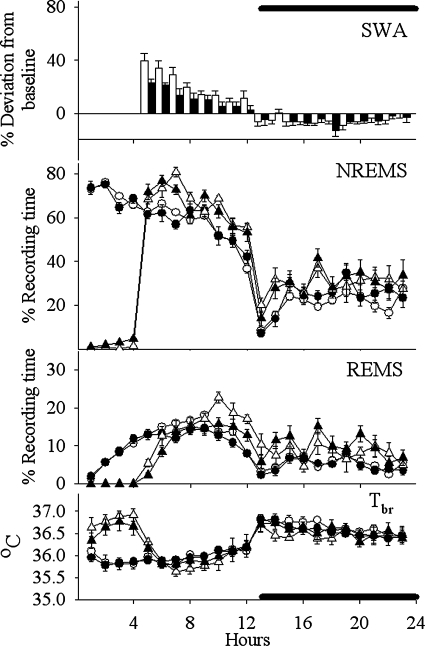

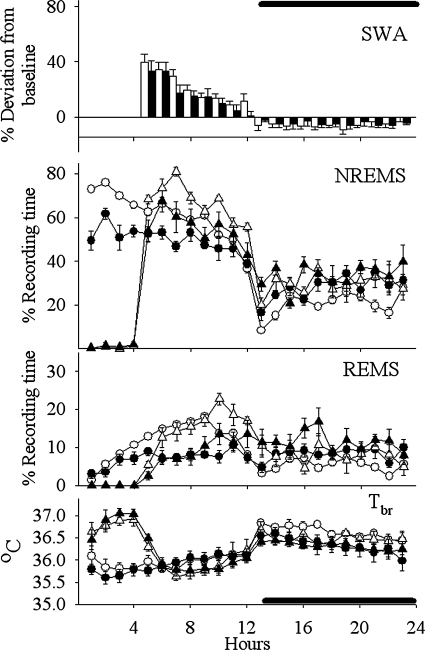

Analyses of duration of NREMS during the light period indicated there was a significant [F(5,66) = 45.351, P < 0.001] reduction in the duration of NREMS in the ALC, ACmid, and ACpost groups (Figs. 5–8) compared with the sham group on baseline days (SNK; P < 0.001) (Table 2). In contrast, values obtained from the PSL (Fig. 9) and UALC (Fig. 6) groups during the light period were not significantly different from the sham group.

Fig. 8.

Effects of the ACpost isolation on sleep (REMS, NREMS, EEG SWA during NREMS, and Tbr) during 23 h of recording period. Measured values were averaged and depicted as means ± SE in the case of the NREMS, REMS, and the Tbr. Percent differences are represented between baseline day and sleep deprivation day values for SWA (bar graph). Solid symbols (including bars) show the ACpost group values and open symbols the sham-operated control values. Baseline values of NREMS, REMS, and Tbr are indicated by circles, whereas triangles indicate responses to 4 h of sleep deprivation (beginning at the light onset).

Fig. 9.

Effects of the PSL isolation on sleep (REMS, NREMS, EEG SWA during NREMS, Tbr) during 23-h of recording period. Measured values were averaged and depicted as means ± SE in the case of the NREMS, REMS, and the Tbr. Percent differences are represented between baseline day and sleep deprivation day values for SWA (bar graph). Solid symbols (including bars) show the PSL group values, and open symbols show the sham-operated control values. Baseline values of NREMS, REMS, and Tbr are indicated by circles, whereas triangles indicate responses to 4 h of sleep deprivation (beginning at the light onset).

During the night time hours, there was a significant increase [F(5,66) = 8.147, P < 0.001] in the duration of NREMS in the ALC, ACmid, and UALC groups (Figs. 5–7) compared with the sham group [SNK; ALC-ACmid: P < 0.001; UALC: (P = 0.002)] (Table 2). Duration of night time NREMS in the ACpost and PSL groups (Figs. 8 and 9) was not statistically different from that observed in the sham group (Table 2).

Fig. 7.

Effects of the ACmid isolation on sleep (REMS, NREMS, EEG SWA during NREMS, and Tbr) during 23-h of recording period. Measured values were averaged and depicted as means ± SE in the case of the NREMS, REMS, and the Tbr. Percent differences are represented between baseline day and sleep deprivation day values for SWA (bar graph). Closed symbols (including bars) show the ACmid group values, and open symbols show the sham-operated control values. Baseline values of NREMS, REMS, and Tbr are indicated by circles, whereas triangles indicate responses to 4 h of sleep deprivation (beginning at the light onset).

The diurnal rhythm of NREMS remained significant only in the sham group [χ2 = 7.46; P < 0.006] and the PSL [χ2 = 5.95; P < 0.015] groups. In all of the other groups, the diurnal rhythm of NREMS was lost during the baseline recording (Figs. 5–8).

Analyses of the amount of REMS occurring during the entire 23-h recording period indicated there were significant group effects [F(5,66) = 3.810, P < 0.04]; these reductions occurred only in the ALC and ACpost groups compared with the sham group (SNK; P = 0.02; P = 0.03, respectively).

One-way ANOVA of day time REMS values indicated that the duration of REMS decreased significantly [F(5,66) = 13.418, P < 0.001] in the ALC, ACmid, and ACpost groups compared with the sham group (SNK; P < 0.01–0.001) during the light period (Table 1). In contrast, duration of REMS in the UALC and PSL groups did not significantly differ from that of the sham group during the light period. During the dark phase, all groups had similar REMS duration, and they were not significantly different from each other (Table 2).

The diurnal rhythm of REMS remained significant only in the sham [χ2 = 13.18; P < 0.0003] and the PSL [χ2 = 7.68; P < 0.005] groups. In all the other groups, the diurnal rhythm of REMS was absent during the baseline recording (Figs. 5–8).

Analyses of the 23-h averages for EEG SWA during NREMS indicated that there were no significant differences between the lesioned groups and the sham group. Similarly, during either the light period or dark period, EEG SWA during NREMS, was not significantly different between any lesion group and the sham group (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effects of different hypothalamic isolation on EEG slow wave activity during NREMS

| Groups | Light | Dark | Total (23 h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALC | 2049.8±162.89 | 2248.1±159.74 | 2148.9±160.36 |

| UALC | 1587.1±150.29 | 1834.6±198.07 | 1710.9±173.91 |

| ACmid | 2070.3±143.72 | 2260.9±162.21 | 2165.6±151.02 |

| ACpost | 2289.6±204.50 | 2493.4±228.31 | 2391.5±215.05 |

| PSL | 1807.2±105.94 | 1973.2±111.33 | 1890.2±107.37 |

| Sham | 2049.4±94.82 | 2328.7±96.58 | 2189.0±92.23 |

Values are expressed as means ± SE of the EEG (μV2) in the 0.5–4.0 Hz frequency range during the 12-h light, 11-h dark or the total (23 h) of the baseline recording period. No significant differences were detected between the treatment groups and the Sham group of rats.

One-way ANOVA indicated that Tbr values obtained during either the 12-h daylight period or the 11-h dark period were not different between any of the groups (Table 2). All groups displayed typical diurnal variations in Tbr, with higher temperatures during dark hours and lower Tbr during the rest period (light hours) (Table 2, Figs. 5–9), thereby indicating that their temperature rhythms were intact during baseline conditions.

Sleep and Cortical Brain Temperature Changes After Sleep Deprivation

Two-way ANOVA for repeated measures showed significant increases in NREMS duration during the recovery sleep period following SD compared with the identical hours (hours 5–23) of baseline sleep in the PSL [F(1,8) = 33.28, P < 0.001], ACmid [F(1,5) = 8.602, P = 0.033], ACpost [F(1,7) = 19.37, P = 0.003] groups (Figs. 7–9), and in the sham-operated control group [F(1,6) = 22.10, P = 0.003]. The only treatment group that failed to respond to SD during the recovery period with an increased NREMS duration was the ALC group of rats [F(1,9) = 3.90, P = 0.08] (Fig. 5).

The PSL [F(1,8) = 40.83, P < 0.001]; ACpost [F(1,7) = 16.65, P = 0.005]; and the sham [F(1,6) = 11.40, P = 0.015] groups responded to SD with an increased amount of REMS time after sleep deprivation (Figs. 8 and 9). SD failed to alter significantly the duration of REMS compared with the baseline values in the ALC [F(1,9) = 2.416, P = 0.155] and ACmid [F(1,5) = 4.720, = 0.082] groups of rats during the 5–23-h period of recovery sleep (Figs. 5 and 7).

EEG SWA during NREMS significantly increased after SD in all groups during the first 4–6 h after SD (Figs. 5 and 7). These increases were not significantly different from those observed in the sham group [F(1,10) = 4.63, P = 0.05].

During SD, Tbr values increased in all groups compared with baseline values: ALC, [F(1;7) = 179.19; P < 0.001]; ACmid, [F(1,5) = 24.40; P < 0.004]; ACpost, [F(1,7) = 167.39; P < 0.001]; PSL, [F(1,6) = 24,14; P < 0.003]; sham, [F(1,9) = 149.50; P < 0.001] (Figs. 5–9). The Tbr values returned to the baseline values during first 8 h of recovery sleep in the PSL, ACmid, ACpost, and sham group of rats. Therefore, no significant differences in the Tbr values were detected in these groups during the recovery sleep period compared with the baseline values. Tbr values, however, decreased significantly below the baseline day values during the first 8 h following the SD during the recovery sleep period in the case of the ALC group: [F(1,7) = 7.17, P = 0.032] (Figs. 5 and 7 ). In the ALC group, the decreased Tbr lasted 13 h after the end of SD.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study demonstrate that anterolateral separation of the MBH results in a decreased NREMS and REMS times, suggesting that MBH projections are involved in sleep regulation. Similar reductions in NREMS and REMS were observed during the light period when differently positioned cuts were applied around the MBH. In contrast, during the dark period, rats with the various MBH separation cuts spent more time in NREMS than the sham-operated control group of rats. Finally, the pituitary stalk-lesioned group did not show any sleep/wake abnormalities, suggesting that arginine vasopressin is not involved in the initiation or the maintenance of sleep.

Role of MBH in Neuroendocrine Regulation and in the Regulation of Sleep

Functionally, the MBH contains both arousal and sleep-promoting neuronal populations. For example, wake-promoting substances are found in ARC neurons (see review in Ref. 15) such as dopamine (5, 21), corticotropic hormone ACTH (37), neuropeptide Y (16), and somatostatin (32, 36). In our experiments, however, wakefulness increased and sleep decreased after the disruption of the anterolateral connections of the MBH. These results suggest that in normal rats the net output of the MBH is sleep promoting rather than wake promoting.

Separating the anterior connections of the MBH caused a profound decrease in both NREMS and REMS during the light period. These results may suggest that connections between the MBH and the AH/POA play a critical role in sleep regulation. Lesions of the AH and basal forebrain (BF) induce profound insomnia in rats (53, 76) and in cats (49, 64, 75). In contrast, electrical stimulations of the POA and olfactory tubercle enhance cat sleep (6, 7), and these areas contain neurons with a NREMS-related firing pattern. Within the AH/POA, there are two distinct neuronal populations implicated in sleep regulation, especially NREMS regulation: the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus (VLPO) (68, 73) and the median preoptic nucleus (19). Immunohistochemical studies described several GHRH-containing fiber systems reaching important sleep regulatory regions in the AH/POA, such as ventral and lateral parts of the POA and structures in the BF (12, 66). Physiological evidence demonstrates that GHRH stimulates NREMS when it is microinjected directly into the AH/POA (80). These data together with our current findings strongly suggest that GHRH-containing fibers originating in the MBH, reach sleep regulatory neuronal population in the AH/POA and might play an important role in the regulation of spontaneous NREMS. On the basis of our current experiments, we cannot exclude the possibility that the micro-knife separation also damaged the efferent projections from the sleep-promoting AH/POA, thus reducing sleep amount.

REMS amount also significantly decreased in the anterior and anterolateral isolated rats, either during the entire recording period or during the light period. Few papers suggest that the AH/POA is involved in the regulation of REMS. REMS is classically viewed as being regulated by the brain stem (30, 34, 48). Recent data, however, suggest that a galaninergic neuronal population located medially and dorsally from the VLPO (so called “extended VLPO”) may be involved in the regulation of REMS (23, 42, 43). Our results are consistent with the idea that, connections of the AH/POA with the brain stem REMS-promoting areas (67, 70) are damaged by different anterior isolation cuts; therefore, they can result in a decrease in REMS amounts during the light period. Although our earlier studies indicate that GH may be involved in the regulation of REMS (54, 61), our current experiment, especially the pituitary stalk lesion series of experiments, did not show a similar outcome. Transection of the pituitary stalk results in disruption of neuronal and circulatory connections between the hypothalamus and the pituitary in the rat. Neuronal damage is long lasting; diabetes insipidus is observable long after the transection, but there is a strong capacity of regeneration of the hypophysial portal vessels in the rat (25–27). This restored portal vessel connection also restores the regulation of anterior hypothalamic hormone secretions, thus GH secretion. These earlier studies are in good agreement with observations (Makara GB, unpublished data) that after a week of recovery period, GH secretion pattern is close to normal in pituitary stalk-lesioned rats. Parallel with this restored GH secretion, we could not determine significant changes in the REMS amount in the PSL group.

The only isolation that affects both NREMS and REMS during the entire recording period was the ALC isolation; therefore, at least, partial involvement of the lateral hypothalamus may have a role in sleep/wake regulatory mechanisms. Anatomically, the ALC isolation group is the only treatment group in which the isolation starts anterior enough, and also is long enough, to separate the MBH from the possible sleep or wake-promoting areas. In contrast, the isolation of the posterior-AC (ACpost) group starts in a more posterior direction and does not isolate the anterior part of the MBH adequately.

Our observations raise the possibility of a functional connection between the MBH-GHRH-containing neurons and a neuronal population of the LH. Although the amount of GHRH-immunoreactive fibers entering the LH is small (12, 66), our results suggest that these projections innervate and may activate possible sleep-promoting, or may inhibit wake-promoting/maintaining neuronal populations in the LH. The LH contains several peptidergic systems, including orexin/hypocretin, ghrelin/obestatin, neuropeptide Y, and melatonin-concentrating hormone-containing neurons, all of which affect sleep. However, a functional or anatomical relationship between the GHRH-containing neuronal population in the MBH and these LH peptidergic neurons remains to be described.

The main inhibitory afferent system innervating the GHRH-containing system in the MBH originates in the anterior part of the PeV and utilizes somatostatin as a neurotransmitter (8, 29, 41, 62). Earlier ALC-isolation studies provided evidence that somatostatin-containing projections, originating from the PeV, do not directly reach the MBH and the ME (45), but the main projection system runs first laterally, reaching the LH, then turns ventral to the lateral retrochiasmatic area, entering into the MBH, innervating the ipsilateral ARC. These inhibitory somatostatin-containing fibers enter the MBH laterally to reach the GHRH-containing neurons. These laterally entering fibers are entirely transected by the ALC isolation and partially by the UALC. As the result of these isolations, the infundibular GHRH-containing neurons are liberated from the inhibition by somatostatin. This possible sleep-promoting effect was blocked by the same transection in the anterior direction. The overall effect is a reduced total sleep time in the ALC group of rats.

Our results also indicate that both the lateral and the anterior connections of the MBH are important in the regulation of rebound sleep after sleep deprivation. After sleep deprivation, NREMS amounts increased significantly in all experimental groups except in the ALC isolation group. Functionally, these ALC isolated rats had the lowest amount of NREMS on baseline day, suggesting a lower sleep pressure; thus, sleep deprivation did not cause as much sleep loss as in the other groups.

Although duration of NREMS was altered in the transected groups, spontaneous EEG SWA and EEG SWA after sleep loss were not affected. These results indicate that the effects of MBH isolations on sleep are independent from the EEG delta power changes, indicating possible different regulatory mechanisms. The anatomical correlates of EEG SWA reside, in part, within the cortex and thalamo-cortical circuitry (71). These circuits would not have been lesioned in our studies. Nevertheless, intact GHRH connections originating from the MBH may have an important role in the regulation of EEG delta power generation. Immunoneutralization of GHRH blocks the rebound sleep response after sleep deprivation, including the intensity of SWA in rats (56). However, in another study we showed that direct application of GHRH onto the somatosensory cortex enhanced EEG SWA during NREMS (72). There are multiple lines of additional evidence suggesting independent regulation of EEG SWA from duration of NREMS, (e.g., see Ref. 35).

Changes of Diurnal Rhythms

The only groups in which the diurnal rhythm of sleep/wake cycles was maintained were the sham-operated control and the pituitary stalk-lesioned groups of rats. All other isolation groups lost their diurnal rhythms of NREMS and REMS. These results are surprising in the case of the REMS because there is little evidence that efferent projections from the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), the principal circadian pacemaker of the brain (31, 52), would directly reach REMS-promoting/ REM-on areas in the brain stem (40). Several electrophysiological studies, however, identified the LH as a target of SCN projections (38, 39, 57). Physiological data indicate that orexin-containing neurons have a strong influence on the circadian regulation of REMS and that the loss of these neurons leads to loss of the circadian rhythm of REMS (24). The anterior and anterolateral isolations in our experiments likely influence the circadian rhythm of REMS via the destructions of SCN fibers reaching the orexinergic neurons in the LH. The PSL did not change either the diurnal rhythm of NREMS or REMS. This was likely because the fiber system from the LH projecting to the brain stem REMS regulatory neurons may run on the lateral side of the hypothalamus and doesn't cross the midline.

The attenuated diurnal rhythm of NREMS in all groups that received anterior or anterolateral isolation cannot be explained by simple transection of the fibers projecting from the SCN to the sleep-promoting nuclei of the AH/POA, because these projection systems remained intact in all of these groups. Our results suggest that circadian information from the SCN first conveyed to the MBH and then possibly transferred to the sleep-active AH/POA. One possible anatomical area that is located inside our isolation cuts is the ventral part of the subparaventricular zone. Indeed, SCN efferents heavily target the subparaventricular zone in the rat (17, 79). Ibotenic acid lesions of the ventral subparaventicular zone markedly reduce circadian rhythms of sleep and locomotor activity (44). Further, the subparaventricular zone targets sleep active VLPO in the POA (13). Another possible candidate to convey integrated circadian information to the AH is the dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus (13, 14). Although the dorsomedial nucleus was only partially transected and only a portion of this nucleus was inside the isolation cuts, these cuts may disturb either direct and indirect afferent projections from the SCN to the dorsomedial nucleus or its GABAergic efferent projections to the VLPO (14).

Cortical Brain Temperature Changes

The medial part of the POA is considered the main thermoregulatory region of the mammalian brain (65, 76), and several lines of evidence indicate a close connection between thermoregulation and sleep (1, 2, 33, 74, 76). We could not detect altered brain temperature values during the baseline days in the various experimental groups. Similar normal responses were seen during sleep deprivation, when animals increased their heat production, and during the recovery period, when in most of the cases, this elevated cortical temperature returned to the baseline level. These findings seem to corroborate earlier results, in which ALC isolation was also used (9). Others found attenuated cold-induced cutaneous vasoconstriction responses, but not shivering responses (18), after micro-knife separation of the POA from the rest of the hypothalamus. One of the major factors regulating core temperature is the regulation of the peripheral vasomotor tone (mainly the sympathetic vasoconstrictor outflow). The peripheral vasodilation following the reduction in the sympathetic vasoconstrictor outflow results in an increased skin blood flow and dissipation of heat from the blood in the case of a heat load (20). In our current experiments, the reduced NREMS response during recovery sleep after sleep deprivation, parallel with a reduced cortical brain temperature response in the ALC group of rats suggests a disturbed heat regulatory system. Retrograde tracing studies of brain structures, responsible for sympathetic outflow to the tail artery of the rat, labeled structures such as the LH, ARC, PVN, ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus, and the dorsomedial nucleus (69). The efferent projections from the thermoregulatory neuronal groups of the POA regulating sympathetic outflow via the MBH (nuclei such as ARC, ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus) and partially the dorsomedial nucleus might also be affected by the anterolateral isolations parallel with the reduced sleep amount during the recovery phase.

Water Consumption Results and Technical Considerations

The knife cut method used herein does not allow distinctions between the afferent and efferent connections of the MBH. However, we can estimate which fiber systems are affected by the various cuts. For example, arginine vasopressin-containing fibers originate mainly from the magnocellular part of the PVN and the supraoptic nucleus reaching the internal layer of the median eminence and the infundibular stalk to the posterior lobe of the pituitary (28). In our experiments, only those groups of rats that obtained posterior enough isolations to transect these arginine vasopressin-containing fibers (in the case of group ALC and ACpost) or where the stalk of the pituitary is damaged (PSL group) increased water consumption and developed diabetes insipidus. Our water consumption results combined with the sleep recordings also excluded the possibility that arginine vasopressin is involved in sleep regulation via the posterior pituitary system, because no sleep changes were detected in the case of the PSL group in contrast with the ALC and the ACpost groups. These water consumption data also reinforce that these Halász-knife isolations were physiologically effective. Earlier experiments also demonstrate that the GHRH system in the MBH hypothalamus remains functionally intact after the anterolateral isolation because the rats are capable of increasing their GH secretion after electrical stimulation (4). These experimental observations also indicate that the transection of these GHRH-containing fibers does not cause cellular death of these projecting neurons. Additional experiments (45) have demonstrated that after ALC isolation no sign of fiber regrowth could be seen, even in seven postoperative weeks.

In summary, the results presented in this article provide functional and anatomical evidence that the MBH system may be linked to the sleep regulatory AH/POA, suggesting that MBH may play a role in integrating sleep-related signals.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the Hungarian National Science Foundation (OTKA T043156) and by the National Institutes of Health, USA (NS27250).

Acknowledgments

Current address for Z. Peterfi: Department of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles; Research Service, Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, North Hills, CA, USA.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alam NM, McGinty D, Szymusiak R. Thermosensitive neurons of the diagonal band in rats: relation to wakefulness and non-rapid eye movement sleep. Brain Res 752: 81–89, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alam NM, McGinty D, Szymusiak R. Neuronal discharge of preoptic/anterior hypothalamic thermosensitive neurons: relation to NREM sleep. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 269: R1240–R1249, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Physiological Society. Guiding principles for research involving animals and human beings. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 283: R281–R283, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antoni FA, Makara GB, Rappay G. Growth hormone releasing activity persists in the deafferented medial-basal hypothalamus of the rat. J Endocrinol 91: 415–425, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ben-Jonathan N Dopamine: a prolactin-inhibiting hormone. Endocr Rev 6: 564–589, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benedek G, Obál F Jr, Rubicsek G, Obál F. Sleep elicited by olfactory tubercle stimulation and the effect of atropine. Behav Brain Res 2: 23–32, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benedek G, Obál F Jr, Szekeres L, Obál F. Two separate synchronizing mechanisms in the basal forebrain: study of the synchronizing effects of the rostral hypothalamus, preoptic region and olfactory tubercle. Arch Ital Biol 117: 164–185, 1979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beranek L, Obal F Jr, Taishi P, Bodosi B, Laczi F, Krueger JM. Changes in rat sleep after single and repeated injections of the long-acting somatostatin analog octreotide. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 273: R1484–R1491, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blatteis CM, Banet M. Autonomic thermoregulation after separation of the preoptic area from the hypothalamus in rats. Pflügers Arch 406: 480–484, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bodosi B, Gardi J, Hajdu I, Szentirmai E, Obal F Jr., Krueger JM. Rhythms of ghrelin, leptin, and sleep in rats: effects of the normal diurnal cycle, restricted feeding, and sleep deprivation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 287: R1071–R1079, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brinkmann H, Bock R. Quantitative Veranderungen “Gomori-positiver” Substanzen in Infundibulum und Hypophysenhinterlappen der Ratte nach Adrenalektomie und Kochsalzoder Durstbelastung. J Neurovisc Relat 32: 48–64, 1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bruhn TO, Anthony EL, Wu P, Jackson IM. GRF immunoreactive neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the rat: an immunohistochemical study with monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies. Brain Res 424: 290–298, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chou TC, Bjorkum AA, Gaus SE, Lu J, Scammell TE, Saper CB. Afferents to the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus. J Neurosci 22: 977–990, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chou TC, Scammell TE, Gooley JJ, Gaus SE, Saper CB, Lu J. Critical role of dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus in a wide range of behavioral circadian rhythms. J Neurosci 23: 10691–10702, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chronwall BM Anatomy and physiology of the neuroendocrine arcuate nucleus. Peptides 6 Suppl 2: 1–11, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chronwall BM, DiMaggio DA, Massari VJ, Pickel VM, Ruggierro DA, Odonohue TL. The anaromy of neuropeptide Y containing neurons in rat brain. Neuroscience 15: 1159–1181, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deurveilher S, Burns J, Semba K. Indirect projections from the suprachiasmatic nucleus to the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus: a dual tract-tracing study in rat. Eur J Neurosci 16: 1195–1213, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilbert TM, Blatteis CM. Hypothalamic thermoregulatory pathways in the rat. J Appl Physiol 43: 770–777, 1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gong H, Szymusiak R, King J, Steininger T, McGinty D. Sleep-related c-Fos protein expression in the preoptic hypothalamus: effects of ambient warming. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 279: R2079–R2088, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gordon CJ Thermal biology of the laboratory rat. Physiol Behav 47: 963–991, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gudelsky GA Tuberoinfundibular dopamine neurons and the regulation of prolactin secretion. Psychoneuroendocrinology 6: 3–16, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guillemin R, Brazeau P, Bohlen P, Esch F, Ling N, Wehrenberg WB. Growth hormone-releasing factor from a human pancreatic tumor that caused acromegaly. Science 218: 585–587, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gvilia I, Turner A, McGinty D, Szymusiak R. Preoptic area neurons and the homeostatic regulation of rapid eye movement sleep. J Neurosci 26: 3037–3044, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hara J, Beuckmann CT, Nambu T, Willie JT, Chemelli RM, Sinton CM, Sugiyama F, Yagami K, Goto K, Yanagisawa M, Sakurai T. Genetic ablation of orexin neurons in mice results in narcolepsy, hypophagia, and obesity. Neuron 30: 345–354, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris GW Neural control of the pituitary gland. London: Arnold, E., 1955.

- 26.Harris GW Regeneration of the hypophysial portal vessels. Nature 162: 70, 1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris GW, Jacopsohn D. Proliferative capacity of the hypophysial portal vessels. Nature 165: 854, 1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hatton GI, Hutton UE, Hoblitzell ER, Armstrong WE. Morphological evidence for two populations of magnocellular elements in the rat paraventricular nucleus. Brain Res 108: 187–193, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Havlicek V, Rezek M, Friesen H. Somatostatin and thyrotropin releasing hormone: central effect on sleep and motor system. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 4: 455–459, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hobson JA, McCarley RW, Wyzinski PW. Sleep cycle oscillation: reciprocal discharge by two brainstem neuronal groups. Science 189: 55–58, 1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ibuka N, Inouye SI, Kawamura H. Analysis of sleep-wakefulness rhythms in male rats after suprachiasmatic nucleus lesions and ocular enucleation. Brain Res 122: 33–47, 1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johansson O, Hokfelt T, Elde RP. Immunohistochemical distribution of somatostatin-like immunoreactivity in the central nervous system of the adult rat. Neuroscience 13: 265–339, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.John J, Kumar VM. Effect of NMDA lesion of the medial preoptic neurons on sleep and other functions. Sleep 21: 587–598, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jouvet M Recherches sur les sttuctures nerveuses et le mecanismes responsable des differentesphasses du sommeil physiologique. Arch Ital Biol 100: 125–206, 1962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kapas L, Bohnet SG, Traynor TR, Majde JA, Szentirmai E, Magrath P, Taishi P, Krueger JM. Spontaneous and influenza virus-induced sleep are altered in TNF-alpha double-receptor deficient mice. J Appl Physiol 105: 1187–1198, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawano H, Daikoku S, Saito S. Immunohistochemical studies of intrahypothalamic somatostatin- containing neurons in rat. Brain Res 242: 227–232, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knigge KM, Joseph SA, Nocton J. Topography of the ACTH immunoreactive neurons in the basal hypothalamus of the rat brain. Brain Res 216: 333–341, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koizumi K, Nishino H. Circadian and other rhythmic activity of neurones in the ventromedial nuclei and lateral hypothalamic area. J Physiol 263: 331–356, 1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kreisel B, Conforti N, Gutnick M, Feldman S. Antidromic responses of suprachiasmatic neurons following mediobasal hypothalamic stimulation. Isr J Med Sci 11: 925–927, 1975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krout KE, Kawano J, Mettenleiter TC, Loewy AD. CNS inputs to the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the rat. Neuroscience 110: 73–92, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lanneau C, Peineau S, Petit F, Epelbaum J, Gardette R. Somatostatin modulation of excitatory synaptic transmission between periventricular and arcuate hypothalamic nuclei in vitro. J Neurophysiol 84: 1464–1474, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu J, Bjorkum AA, Xu M, Gaus SE, Shiromani PJ, Saper CB. Selective activation of the extended ventrolateral preoptic nucleus during rapid eye movement sleep. J Neurosci 22: 4568–4576, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu J, Greco MA, Shiromani P, Saper CB. Effect of lesions of the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus on NREM and REM sleep. J Neurosci 20: 3830–3842, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lu J, Zhang YH, Chou TC, Gaus SE, Elmquist JK, Shiromani P, Saper CB. Contrasting effects of ibotenate lesions of the paraventricular nucleus and subparaventricular zone on sleep-wake cycle and temperature regulation. J Neurosci 21: 4864–4874, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Makara GB, Palkovits M, Antoni FA, Kiss JZ. Topography of the somatostatin-immunoreactive fibers to the stalk-median eminence of the rat. Neuroendocrinology 37: 1–8, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Makara GB, Stark E, Palkovits M. ACTH release after tuberal electrical stimulation in rats with various cuts around the medial basal hypothalamus. Neuroendocrinology 27: 109–118, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Makara GB, Stark E, Palkovits M, Revesz T, Mihaly K. Afferent pathways of stressful stimuli: corticotropin release after partial deafferentation of the medial basal hypothalamus. J Endocrinol 44: 187–193, 1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McCarley RW, Hobson JA. Neuronal excitability modulation over the sleep cycle: a structural and mathematical model. Science 189: 58–60, 1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McGinty DJ, Sterman MB. Sleep suppression after basal forebrain lesions in the cat. Science 160: 1253–1255, 1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meister B, Hokfelt T, Vale WW, Goldstein M. Growth hormone releasing factor (GRF) and dopamine coexist in hypothalamic arcuate neurons. Acta Physiol Scand 124: 133–136, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Merchenthaler I, Vigh S, Schally AV, Petrusz P. Immunocytochemical localization of growth hormone-releasing factor in the rat hypothalamus. Endocrinology 114: 1082–1085, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moore RY, Lenn NJ. A retinohypothalamic projection in the rat. J Comp Neurol 146: 1–14, 1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nauta WJH Hypothalamic regulation of sleep in rats: an experimental study. J Neurophysiol 9: 285–316, 1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Obal F, Floyd R, Kapas L, Bodosi B, Krueger JM. Effects of systemic GHRH on sleep in intact and hypophysectomized rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 270: E230–E237, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Obal F., Krueger JM. GHRH and sleep. Sleep Med Rev 8: 367–377, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Obal F, Payne L, Opp M, Alfoldi P, Kapas L, Krueger JM. Growth hormone-releasing hormone antibodies suppress sleep and prevent enhancement of sleep after sleep deprivation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 263: R1078–R1085, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oomura Y, Ono T, Ooyama H, Wayner MJ. Glucose and osmosensitive neurones of the rat hypothalamus. Nature 222: 282–284, 1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Opp MR, Obal F Jr, Payne L, Krueger JM. Responsiveness of rats to interleukin-1: effects of monosodium glutamate treatment of neonates. Physiol Behav 48: 451–457, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotxic Coordinates. San Diego, CA: Academic, 1998.

- 60.Peterfi Z, Churchill L, Hajdu I, Obal JF, Krueger JM, Parducz A. Fos-immunoreactivity in the hypothalamus: dependency on the diurnal rhythm, sleep, gender, and estrogen. Neuroscience 124: 695–707, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Peterfi Z, Obal F Jr, Taishi P, Gardi J, Kacsoh B, Unterman T, Krueger JM. Sleep in spontaneous dwarf rats. Brain Res 1108: 133–146, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rezek M, Havlicek V, Hughes KR, Friesen H. Cortical administration of somatostatin (SRIF): effect on sleep and motor behavior. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 5: 73–77, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rivier J, Spiess J, Thorner M, Vale W. Characterization of a growth hormone-releasing factor from a human pancreatic islet tumour. Nature 300: 276–278, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sallanon M, Denoyer M, Kitahama K, Aubert C, Gay N, Jouvet M. Long-lasting insomnia induced by preoptic neuron lesions and its transient reversal by muscimol injection into the posterior hypothalamus in the cat. Neuroscience 32: 669–683, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Satinoff E Neural organization and evolution of thermal regulation in mammals. Science 201: 16–22, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sawchenko PE, Swanson LW, Rivier J, Vale WW. The distribution of growth-hormone-releasing factor (GRF) immunoreactivity in the central nervous system of the rat: an immunohistochemical study using antisera directed against rat hypothalamic GRF. J Comp Neurol 237: 100–115, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Semba K, Fibiger HC. Afferent connections of the laterodorsal and the pedunculopontine tegmental nuclei in the rat: a retro- and antero-grade transport and immunohistochemical study. J Comp Neurol 323: 387–410, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sherin JE, Shiromani PJ, McCarley RW, Saper CB. Activation of ventrolateral preoptic neurons during sleep. Science 271: 216–219, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Smith JE, Jansen AS, Gilbey MP, Loewy AD. CNS cell groups projecting to sympathetic outflow of tail artery: neural circuits involved in heat loss in the rat. Brain Res 786: 153–164, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Steininger TL, Wainer BH, Blakely RD, Rye DB. Serotonergic dorsal raphe nucleus projections to the cholinergic and noncholinergic neurons of the pedunculopontine tegmental region: a light and electron microscopic anterograde tracing and immunohistochemical study. J Comp Neurol 382: 302–322, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Steriade M The corticothalamic system in sleep. Front Biosci 8: d878–d899, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Szentirmai E, Yasuda T, Taishi P, Wang M, Churchill L, Bohnet S, Magrath P, Kacsoh B, Jimenez L, Krueger JM. Growth hormone-releasing hormone: cerebral cortical sleep-related EEG actions and expression. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 293: R922–R930, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Szymusiak R, Alam N, Steininger TL, McGinty D. Sleep-waking discharge patterns of ventrolateral preoptic/anterior hypothalamic neurons in rats. Brain Res 803: 178–188, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Szymusiak R, Danowski J, McGinty D. Exposure to heat restores sleep in cats with preoptic/anterior hypothalamic cell loss. Brain Res 541: 134–138, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Szymusiak R, McGinty D. Sleep suppression following kainic acid-induced lesions of the basal forebrain. Exp Neurol 94: 598–614, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Szymusiak R, Satinoff E. Ambient temperature-dependence of sleep disturbances produced by basal forebrain damage in rats. Brain Res Bull 12: 295–305, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Takahashi Y, Kipnis DM, Daughaday WH. Growth hormone secretion during sleep. J Clin Invest 47: 2079–2090, 1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Toppila J, Alanko L, Asikainen M, Tobler I, Stenberg D, Porkka-Heiskanen T. Sleep deprivation increases somatostatin and growth hormone-releasing hormone messenger RNA in the rat hypothalamus. J Sleep Res 6: 171–178, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Watts AG, Swanson LW, Sanchez-Watts G. Efferent projections of the suprachiasmatic nucleus: I Studies using anterograde transport of Phaseolus vulgaris leucoagglutinin in the rat. J Comp Neurol 258: 204–229, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhang J, Obal F Jr, Zheng T, Fang J, Taishi P, Krueger JM. Intrapreoptic microinjection of GHRH or its antagonist alters sleep in rats. J Neurosci 19: 2187–2194, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]