Abstract

A 60-year-old man presented with cough, sputum, and dyspnea. He had a history of acute myeloid leukemia and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with chronic renal failure. Chest CT scans showed miliary nodules and patchy consolidations. Histological examination revealed numerous fibrin balls within the alveoli and thickening of the alveolar septum, both of which are typical pathological features of acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia (AFOP). We report the first case of AFOP following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Keywords: Acute fibrinous, organizing pneumonia, Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, Graft-versus-host disease

INTRODUCTION

The incidences of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) are increasing. In particular, 40-60% of patients with HSCT sometimes develop pulmonary complications, with the incidence varying according to the type of transplant, conditioning regimen, underlying disease, and age of the patient. Pulmonary complications encompass various noninfectious conditions, including pulmonary edema, diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, idiopathic pneumonia syndrome, bronchiolitis obliterans, and cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP) [1]. There also exist unusual histological patterns with predominantly intra-alveolar fibrin and organizing pneumonia, which do not meet the criteria for acute interstitial pneumonia or COP. Thus far, there are only a few reports describing these findings [2-4]. In this paper, we describe a case of intra-alveolar fibrin and organizing pneumonia following allogeneic HSCT.

CASE REPORT

A 60-year-old man, who had no history of smoking, was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia (FAB classification M1) in February 2005. He was treated with anthracyclin and cytarabine arabinoside for remission induction and postremission therapy. During the first remission induction period, he developed chemotherapy-related pneumonia and sepsis for 21 days. At the second induction chemotherapy, we confirmed a complete remission through bone marrow biopsy and aspiration. Next, we tested his sibling's human leukocyte antigen (HLA) in an attempt to find a stem cell donor. Completely matched HLA (A, B, C, and DR) and ABO-matched blood were detected in his 55-year-old sister. From his sister, we collected the G-CSF-mobilized stem cells from peripheral blood and harvested the bone marrow. The total concentrations of the various components of the harvested cells were as follows: total nuclear cells (TNCs), 19.48×108/recipient-kg; mononuclear cells (MNCs), 10.11×108/kg; CD34 cells, 1.8×106/kg; and CD3 cells, 21.7×107/kg. After nonmyeloabrative conditioning with fludarabine (from day -9 to day -5; 25 mg/m2/day1) and melphalan (from day -4 to day -3; 70 mg/m2/day1), the patient underwent allogeneic HSCT with total harvested cells in September 2005. He was treated with cyclosporine A and short-term methotrexate for GVHD prophylaxis. Pulmonary function test (PFT), including spirometry, lung volume, diffusion, and airway resistance, performed before the transplantation showed mild pulmonary insufficiency of the mixed type with decreased cabon monoxide diffusing capacity (DLCO). The patient also had chronic renal failure that was treated with hemodialysis. In November 2005, he complained of cough and dyspnea due to pleural effusion, but the symptoms disappeared after intensified hemodialysis and pleurodesis with talc.

In January 2006, he again complained of cough, sputum, and exertional dyspnea for 3 days. On physical examination, the respiratory rate was 18/min and the heart rate was 104 beats/min. However, there was no fever, edema, or cyanosis. Auscultation revealed fine inspiratory crackles in both lung bases. The C-reactive protein level was 6.0 mg/dL (normal: ≤0.4 mg/dL); erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 25 mm/h (normal: ≤9 mm/hours); and serum creatinine level, 4.4 mg/dL (normal: ≤1.20 mg/dL). The white blood cell count was 5200× 103/µL (normal: 4,000-10,000×103/µL) with normal differential counts; hemoglobin concentration, 7.9 g/dL (normal: 14-18 g/dL); and platelet count, 44×103/µL (normal: 150-450×103/µL). Examination of arterial blood gases in room air revealed a pH of 7.527, PaCO2 of 38.8 mmHg, and PaO2 of 72.2 mmHg. Both cytomegalovirus and Pneumocystis carinii were found to be negative by PCR of the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid. BAL was also negative for the markers of other infections. Cryptogenic antigen was negative in the peripheral blood. Bone marrow study showed no evidence of leukemic blast. Chromosome analysis showed 46XX, and chimerism analysis revealed complete chimerism.

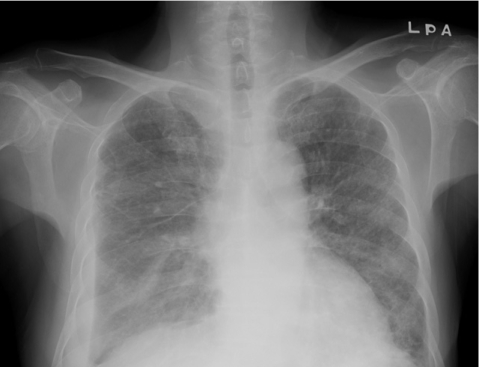

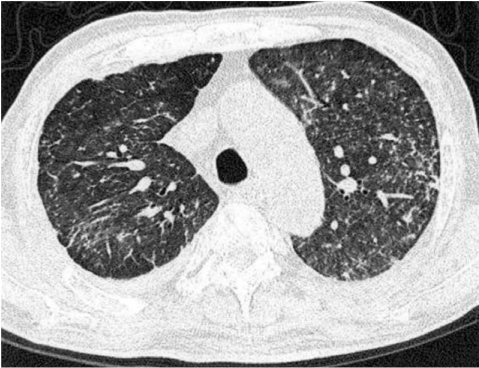

The initial chest radiograph demonstrated diffuse haziness and miliary nodules in both the lungs and slight right pleural effusion (Fig. 1). There were no significant changes on chest radiographs after hemodialysis. High-resolution chest CT (HRCT) scans showed diffuse miliary nodules and ground glass opacity in both the lungs, patchy consolidation in the left lower lobe, and pleural effusion in the right lobe (Fig. 2). He had been on regular dialysis and had not had any change of pleural effusion. PFT findings worsened to extremely severe pulmonary insufficiency of a restrictive type and moderately decreased DLCO.

Figure 1.

The chest radiography. The initial chest radiograph reveals diffuse haziness and miliary nodules in both the lungs and slight right pleural effusion.

Figure 2.

HRCT. HRCT scan shows diffuse miliary nodules and ground glass opacity in both the lungs and pleural effusion in the right lobe. Patchy consolidation in the left lower lobe can be noted on the CT scan.

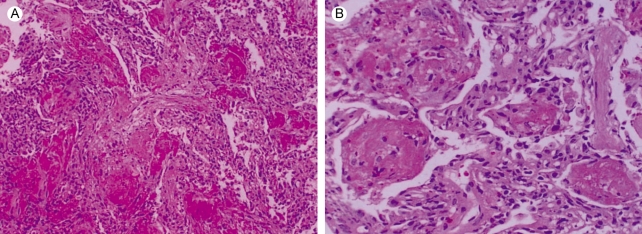

At admission day 4, transbronchial lung biopsy was performed. All 6 biopsy specimens revealed similar pathological findings. The specimens showed intraalveolar spaces containing fibrous plugging with extensive fibrin deposition, a finding consistent with cryptogenic organizing pneumonia with fibrous exudates (Fig. 3A). Fibrin balls with hemosiderin deposition were noted in the alveolar spaces (Fig. 3B). There was no evidence of diffuse alveolar damage, alveolitis, eosinophilic infiltration, or granulomas. Fibrin ball is a characteristic finding of acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia (AFOP) and presents as dense and red coalescent masses on hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining. There were no histological features of uremic lung, including protein-rich edema, vascular congestion, tuberculous infection, or fungal infection. A course of broad-spectrum antibiotics and methylprednisolone pulse therapy (60 mg/day) was administered. At day 28 of the methylprednisolone treatment (30 mg/day), ground opacity and military nodules in both the lungs and right pleural effusion were slightly decreased with concomitant improvement in his respiratory symptoms and O2 saturation. At day 44 of the methylprednisolone treatment, ground glass opacity and miliary nodules in both the lungs increased, and the PFT showed no change. Therefore, we increased the dose of methylprednisolone to 45 mg/day. At day 61 of the methylprednisolone treatment (20 mg/day), the patient developed hemoptysis, for which we performed bronchial angiography with embolization. After 3 days, he died due to respiratory failure.

Figure 3.

Microscopic findings of a lung specimen. (A) The biopsied lung shows intra-alveolar spaces containing fibrous plugging with extensive fibrin deposition, a finding consistent with cryptogenic organizing pneumonia with fibrous exudates (H&E, ×100). (B) Fibrin balls with hemosiderin deposition are noted in the alveolar spaces (H&E, ×200).

DISCUSSION

AFOP was first reported by Beasley in 2002 as an unusual type of acute lung injury [2]. Progressive dyspnea was the major symptom, with commonly accompanying cough, fever, and chest pain. Thus far, there are only a few reports describing AFOP [2-4]. This disease is characterized by histological features comprising prominent intraalveolar fibrin deposition (fibrin balls) and organizing pneumonia [2]. Although its clinical and radiological features have not been precisely defined, AFOP is presumed to be a type of diffuse alveolar damage. It has been reported that AFOP can either be idiopathic or occur in association with a spectrum of clinical conditions, including collagen vascular diseases, adverse drug or chemicals reactions, lymphoma, altered immune status, and inhalation diseases [2,3]. The present patient had a history of acute myeloid leukemia with chronic renal failure. Histologically, there was no evidence of uremic lung, which is characterized by generalized protein-rich interstitial and intraalveolar edema associated with the expansion of parenchymal connective tissues and prominent lymphatic duct ectasia [5]. Hemodialysis did not result in the improvement of the lung lesions. These findings indicated AFOP as the histological and clinical diagnosis in this patient.

At admission, the HRCT scan revealed new patchy consolidations in the left lower lobe and diffuse military nodules in both the lungs. Accordingly, we suspected miliary tuberculosis or disseminated fungal infection as the diagnosis. These clinical and radiological findings were similar to those described in the case report of Kobayashi [4]. Beasley has described the radiological features of 15 patients with AFOP: the most common radiographic pattern was bilateral basilar infiltration, and nodular lesions were not seen in any of the 15 patients [2].

There appear to be 2 clinical presentations of AFOP. One is the subacute type that resembles COP or bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP) [6]. In patients with COP or BOOP, a solitary nodule or multiple nodules were detected radiologically. Akira reported that 53 of 60 nodular lesions detected in 12 BOOP patients had an irregular margin, and 27 had an air bronchogram. Therefore, he concluded that BOOP should be considered when imaging reveals nodular lesions with an air bronchogram and irregular margins [7]. Thus, the first type of AFOP was reported to have some clinical similarities with BOOP [8-10]. Corticosteroid therapy resulted in the improvement of nodular lesions and diffuse infiltrates. The disease in our patient may be classified as the subacute type of AFOP. The second type shows a more rapid progression and has clinical features similar to that of acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Pulmonary complications account for significant morbidity and mortality in patients after HSCT, with an incidence rate of 70%, and are a contributing factor in more than 30% of transplant-related deaths [11]. With the advances in transplantation, the reports of noninfectious pulmonary complications have increased. However, there are a few reports on acute-onset noninfectious pulmonary complications following HSCT. Noninfectious pulmonary complications are the major causes of morbidity and mortality after allogeneic HSCT. Epidemiological data suggest that conditioning-related toxicity is the major contributing factor although GVHD may play a role. Among the noninfectious pulmonary complications, obliterative bronchiolitis and BOOP are more closely associated with GVHD [12]. The other complications are pulmonary edema, engraftment syndrome, diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, and pulmonary veno-occlusive disease [1].

The uniqueness of this report is that it describes the first case of AFOP following allogeneic HSCT, and this condition may be a type of GVHD in the lung. Further information should be obtained about the clinical and radiological features of AFOP and the differences between AFOP and other acute interstitial lung disease. The present case report provides useful data about this new entity.

References

- 1.Yen KT, Lee AS, Krowka MJ, Burger CD. Pulmonary complications in bone marrow transplantation: a practical approach to diagnosis and treatment. Clin Chest Med. 2004;25:189–201. doi: 10.1016/S0272-5231(03)00121-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beasley MB, Franks TJ, Galvin JR, Gochuico B, Travis WD. Acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia: a histological pattern of lung injury and possible variant of diffuse alveolar damage. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2002;126:1064–1070. doi: 10.5858/2002-126-1064-AFAOP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prahalad S, Bohnsack JF, Maloney CG, Leslie KO. Fatal acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia in a child with juvenile dermatomyositis. J Pediatr. 2005;146:289–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kobayashi H, Sugimoto C, Kanoh S, Motoyoshi K, Aida S. Acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia: initial presentation as a solitary nodule. J Thorac Imaging. 2005;20:291–293. doi: 10.1097/01.rti.0000168600.78213.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bleyl U, Sander E, Schindler T. The pathology and biology of uremic pneumonitis. Intensive Care Med. 1981;7:193–202. doi: 10.1007/BF01724840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society International Multidisciplinary Consensus Classification of the Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:277–304. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.2.ats01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akira M, Yamamoto S, Sakatani M. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia manifesting as multiple large nodules or masses. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:291–295. doi: 10.2214/ajr.170.2.9456931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chee CB, Da Costa JL, Sim CS. A female with dry cough, progressive dyspnea and weight loss. Eur Respir J. 2005;25:206–209. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00053504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poletti V, Casoni GL. Cryptogenic organising pneumonia or acute fibrinous and organising pneumonia? Eur Respir J. 2005;25:1128. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00004805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cordeiro CR. Airway involvement in interstitial lung disease. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2006;12:337–341. doi: 10.1097/01.mcp.0000239550.47702.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wah TM, Moss HA, Robertson RJ, Barnard DL. Pulmonary complications following bone marrow transplantation. Br J Radiol. 2003;76:373–379. doi: 10.1259/bjr/66835905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watkins TR, Chien JW, Crawford SW. Graft versus host-associated pulmonary diasesa and other idiopathic pulmonary complications after hematopoietc stem cell transplant. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;26:482–489. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-922031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]