Abstract

Recent clinical reports strongly support the intriguing possibility that emotional stress alone is sufficient to cause reversible myocardial dysfunction in patients. We previously reported that a combination of prenatal stress followed by restraint stress (PS+R) results in echocardiographic evidence of myocardial dysfunction in anesthetized rats compared with control rats subjected to the same restraint stress (Control+R). We now report results of our catheter-based hemodynamic studies in both anesthetized and freely ambulatory awake rats, comparing PS+R vs. Control+R. Systolic function [positive rate of change in left ventricular pressure over time (+dP/dt)] was significantly depressed (P < 0.01) in PS+R vs. Control+R both under anesthesia (6,287 ± 252 vs. 7,837 ± 453 mmHg/s) and awake (10,438 ± 741 vs. 12,111 ± 652 mmHg/s). Diastolic function (−dP/dt) was also significantly depressed (P < 0.05) in PS+R vs. Control+R both under anesthesia (−5,686 ± 340 vs. −7,058 ± 458 mmHg/s) and awake (−8,287 ± 444 vs. 10,440 ± 364 mmHg/s). PS+R also demonstrated a significantly attenuated (P < 0.05) hemodynamic response to increasing doses of the β-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol. Intraperitoneal injection of the p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB-203580 reversed the baseline reduction in +dP/dt and −dP/dt as well as the blunted isoproterenol response. Intraperitoneal injection of SB-203580 also reversed p38 MAP kinase and troponin I phosphorylation in cardiac myocytes isolated from PS+R. Thus the combination of prenatal stress followed by restraint stress results in reversible depression in both systolic and diastolic function as well as defective β-adrenergic receptor signaling. Future studies in this animal model may provide insights into the basic mechanisms contributing to reversible myocardial dysfunction in patients with ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathies.

Keywords: heart failure, emotional stress, hemodynamics

an important relationship between emotional stress and the heart has been the subject of speculation for centuries (20). An effect of emotional stress on cardiac rhythms, coronary and vascular blood flow, and hypertension has been extensively explored (2, 27, 28). However, a direct effect of emotional stress on the myocardium was not appreciated until recently. Clinical reports now strongly suggest that emotional stress alone is sufficient to cause reversible myocardial dysfunction in patients (9, 23).

We have previously described (16) a novel rat model of reversible myocardial dysfunction using a combination of prenatal stress followed by restraint stress (PS+R). We provided echocardiographic evidence of myocardial dysfunction in anesthetized PS+R compared with control rats subjected to the same restraint stress (Control+R). We also reported the reversal of a blunted adrenergic response to isoproterenol by a p38 MAP kinase inhibitor in cardiac myocytes isolated from PS+R in vitro. The previous studies were limited by the use of the potentially more subjective and qualitative technique of echocardiography, which also necessarily requires the use of general anesthesia in laboratory animals. In addition, the effects of the p38 MAP kinase inhibitor were examined in cardiac myocytes in vitro, but not in vivo.

The present studies were conducted to determine whether the initial echocardiographic observations under anesthesia would be confirmed in the more physiologically rigorous and relevant catheter-based hemodynamic measurements in awake animals. In addition, we were interested in determining whether our observations in cardiac myocytes in vitro would be confirmed in awake animals in vivo. We now confirm, extend, and expand our previous studies by demonstrating both systolic and diastolic dysfunction and reversal of attenuated adrenergic response to isoproterenol with a p38 MAP kinase inhibitor in freely ambulatory awake PS+R compared with Control+R.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All reagents were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise indicated. Adult male and female (230–300 g) Sprague-Dawley rats were purchased from Hilltop Lab Animals (Scottdale, PA) and housed in a room specifically dedicated for rats in the Animal Care Facility of either the Robert C. Byrd Health Sciences Center of West Virginia University or the adjacent National Institutes of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). Strict adherence to the protocol dually approved by the West Virginia University Animal Care and Use Committee and NIOSH was maintained throughout.

Stress paradigm.

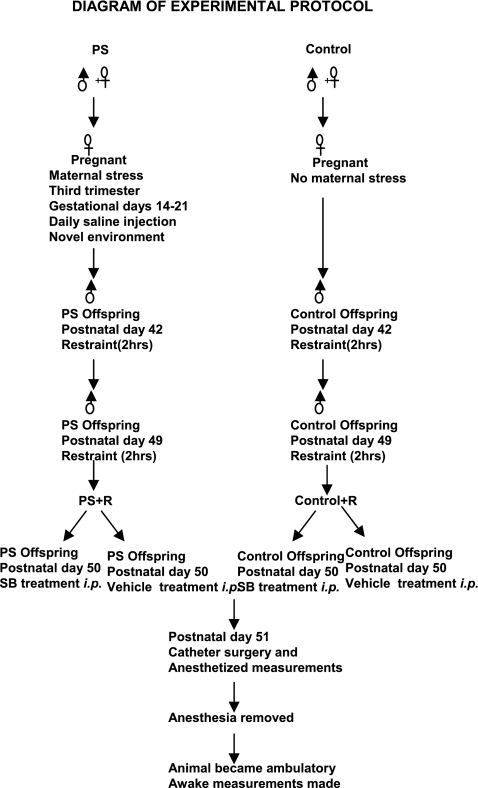

The experimental protocol is illustrated in Fig. 1. Offspring were obtained by breeding male and female Sprague-Dawley rats. Maternal stress was induced by daily saline injections (0.9%, 1 ml sc) at different times of day and moving from cage to cage from gestational day 14 to day 21, as we previously reported (16). Male offspring from stressed or control dams were restrained for 2 h at 25°C in plastic tubes under normal room light at 42 days and again at 49 days of age, as we previously reported (16). During restraint the animal's head was exposed, but the animal was unable to back up or turn and had limited lateral mobility. No open field testing was performed. SB-203589 (SB)-treated rats were injected with 5 mg/kg SB (ip) 24 h before catheter surgery, as previously reported (15).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram illustrating the steps involved in generating this animal model of prenatal stress (PS) + restraint stress (PS+R) vs. control + restraint (Control+R), SB-203589 (SB) treatment, catheter surgery, and hemodynamic measurements.

In vivo hemodynamic measurements.

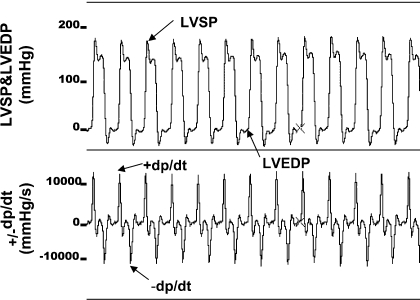

For in vivo hemodynamic measurements (see Fig. 2), catheters were inserted into rats under anesthesia with 2% isoflurane at the rate of 2 l/min oxygen, as we previously reported (21). All catheters were passed through subcutaneous tunnels at the back of the neck and patency was maintained with heparin flushes. Initial hemodynamic determinations were made while the animals were still under general anesthesia (“anesthetized”). Subsequently, “awake” measurements were made at 2 h after anesthesia, when all rats were fully conscious and freely ambulatory. For intravenous drug administration, a 3-Fr silicone catheter (Access Technologies) was placed in the right jugular vein. Mean arterial pressure was measured with a catheter (PE-10, Access Technologies) inserted into the left femoral artery with a 3-Fr polyurethane catheter (Access Technologies) passed through subcutaneous tunnels to the back of the neck. Left ventricular systolic pressure (LVSP), left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP), positive and negative rates of change in left ventricular pressure over time (+dP/dt, −dP/dt), systemic blood pressure, and heart rate measurements were determined by using 3-Fr polyurethane catheters that were advanced into the left ventricle via the right carotid artery or a femoral artery catheter with a powerlab/4SP analog-to-digital converter (ADInstruments, Chalgrove, UK), as we previously reported (21).

Fig. 2.

Representative tracings of simultaneously recorded left ventricular systolic pressure (LVSP), left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP), and positive and negative rates of change in left ventricular pressure over time (+dP/dt, −dP/dt) in a freely ambulatory, awake rat from the PS+R control group.

Isolation of adult rat ventricular myocytes.

Cells were isolated from the hearts of adult male Sprague-Dawley rats, as we previously reported (16). Rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium, and the hearts were removed rapidly and perfused with Krebs-Henseleit bicarbonate buffer (KHB) containing (in mM) 118.1 NaCl, 3.0 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.0 KH2PO4, 27.3 NaHCO3, 10.0 glucose, and 2.5 pyruvic acid, pH 7.4, according to the method of Langendorff at a constant rate of 8 ml/min with a peristaltic pump. All buffer and enzyme solutions used during cell isolation were maintained at 37°C and preequilibrated with 95% O2-5% CO2. Hearts were perfused with KHB for 15 min, followed by change to low-Ca2+ KHB containing (in mM) 105.1 NaCl, 3.0 KCl, 0.01 CaCl2, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.0 KH2PO4, 20.0 NaHCO3, 10.0 glucose, 5.0 pyruvic acid, 10.0 taurine, and 5.0 mannitol, pH 7.4, for an additional 10 min. Hearts were then immersed in recirculating KHB with low Ca2+ containing collagenase B (1.25 mg/ml; Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN) for 40 min. The ventricles were minced and placed into a 50-ml centrifuge tube, followed by dissociation of cells and debris with vigorous pipetting. The resultant mixture was passed through 225-μm nylon mesh and centrifuged at 50 g for 2 min. The pellet was used for protein extraction (16).

Protein phosphorylation assay.

Phosphorylation of p38 MAP kinase and troponin I were determined by Western blotting, as we previously reported (16). The quantity of each sample loaded was determined by using nonphosphoprotein (p38 MAP kinase, troponin I) antibodies on the same blots. To reuse the blot, the blot was left in the stripping buffer (7 M guanidine-HCl, 2.5 M glycine, 0.05 mM EDTA, 0.1 M KCl, 20 mM mercaptoethanol) for 15 min, and the blot was washed with distilled water and reblotted with different antibodies. Blots were detected with the Amersham enhanced chemiluminescence system. Cells were lysed by adding 100 μl/106 cells of lysis on ice. This was followed by sonicating for 2 s and centrifuging at 10,000 g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was transferred to a new centrifuge tube. Sample buffer was added to protein samples at a ratio of 5:1 and microcentrifuged for 30 s, followed by loading 30 μg of total protein onto SDS-PAGE.

Immunoprecipitation and phosphorylation assay of tropomyosin.

Immunoprecipitation was performed according to the Seize X Mammalian Immunoprecipitation kit (Pierce). Tropomyosin antibody (200 μg) was added to 50% protein G-Sepharose bead slurry (400 μl) and rocked for 30 min, followed by another 2-h incubation with disuccinimidyl suberate, used to cross-link antibody and protein G-Sepharose bead. Two milligrams of total protein in 500 μl of lysis buffer was added and rocked overnight at 4°C. The beads bound with proteins were then collected by centrifuging at 5,000 g for 1 min at 4°C. Supernatant was discarded, and the bead pellet was washed three times at room temperature with the IgG elution buffer in the kit. Purified protein was collected in the buffer. The protein was combined with 5× sample buffer and boiled for 5 min. Proteins from the immunoprecipitations were separated on SDS-PAGE and transferred to a membrane. The membrane was immunoblotted with tropomyosin and phosphoserine antibody.

Statistical methods.

In vivo hemodynamic data are presented in Table 1 as means ± SE of values obtained from 6–12 different rats in each group. The statistical methodology involved an analysis of variance appropriate to the split-plot (or repeated measures) nature of the experimental design. In those analyses, the factor of primary interest was the interaction term. Bonferroni-corrected orthogonal contrasts were used when significance in the interaction term was observed to compare the experimental (PS+R) and control (Control+R) groups at each dosage level. Values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. JMP statistical software (version 7.0) was used for all statistical procedures (SAS Institute).

Table 1.

Cumulative hemodynamic data in prenatally stressed rats after restraint stress versus similarly restrained control rats under general anesthesia and in the freely ambulatory awake state

| Group | +dP/dt, mmHg/s | LVSP, mmHg | −dP/dt, mmHg/s | LVEDP, mmHg | HR, beats/min | BP, mmHg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anesthesia | ||||||

| Control+R | 7,836.6±452.5 | 143.1±3.5 | −7,057.7±458.4 | 6.8±2.1 | 329.7±7.7 | 96.0±1.7 |

| PS+R | 6,287.0±252.2 | 131.2±3.2 | −5,685.8±340.0 | 8.8±1.2 | 315.3±14.3 | 84.3±1.2 |

| P | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | NS | NS | <0.05 |

| Awake | ||||||

| Control+R | 12,110.5±652.0* | 185.5±3.1* | −10,440.0±363.7* | 3.8±2.3* | 397.4±7.3* | 131.1±2.6* |

| PS+R | 10,437.8±741.1* | 165.6±1.7* | −8,287.1±444.0* | 4.8±1.3* | 370.3±12.7* | 126.9±4.5* |

| P | <0.01 | <0.05 | <0.05 | NS | NS | NS |

Values are mean ± SE cumulative hemodynamic data in prenatally stressed rats following restraint stress (PS+R) vs. similarly restrained control rats (Control+R) determined under general anesthesia and in the freely ambulatory awake state. +dP/dt, −dP/dt, positive and negative rates of change in left ventricular pressure over time; LVSP, left ventricular systolic pressure; LVEDP, left ventricular end-diastolic pressure; HR, heart rate; BP, blood pressure. P values shown are for Control+R vs. PS+R; NS = not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

P < 0.05, general anesthesia vs. freely ambulatory awake state.

RESULTS

Maternal stress was induced by daily subcutaneous saline injections into skin folds behind the neck (0.9%, 0.1 ml sc) at different times of day and moving from cage to cage from gestational day 14 through day 21, as we previously reported (16). Male offspring from maternally stressed and control rats were subsequently subjected to the same restraint stress paradigm for 2 h at 42 days and again at 49 days of postnatal age. These groups are referred to as PS+R and Control+R, as we previously described (16) (Fig. 1).

We previously reported (16) a decrease in left ventricular fractional shortening in PS+R vs. Control+R in anesthetized rats by echocardiography. We first sought to determine whether the differences noted by echocardiography under general anesthesia would be confirmed by catheter-based hemodynamic measurements. Table 1 summarizes the results of catheter-based hemodynamic measurements comparing PS+R with Control+R under general anesthesia and awake conditions. Systolic dysfunction under general anesthesia was confirmed in PS+R, as evidenced by a decrease in both +dP/dt and LVSP (Table 1). The use of the more sensitive catheter-based technique also provided convincing evidence of diastolic dysfunction in PS+R under anesthesia, as reflected in a decrease in −dP/dt (Table 1). Thus these hemodynamic findings confirm and extend our previously reported echocardiographic data in anesthetized rats. As expected, general anesthesia significantly altered hemodynamic parameters in both PS+R and Control+R (P < 0.05 for each; Table 1).

Most importantly, this catheter-based technique provides the unique capacity to assess hemodynamic parameters in the more physiologically and clinically relevant state of being both freely ambulatory and awake (Fig. 2; Table 1). Here, too, the PS+R animals demonstrate both systolic and diastolic dysfunction compared with Control+R, as evidenced by reduced +dP/dt (P < 0.01), LVSP (P < 0.05), and −dP/dt (P < 0.05). In addition, the reduced systemic blood pressure observed in PS+R compared with Control+R under anesthesia (P < 0.05) is no longer apparent in the awake state [P = not significant (NS)]. Whether this finding relates to enhanced sensitivity of PS+R to anesthetic stress is unclear. Most importantly, the decrease in +dP/dt in PS+R vs. Control+R is significant and even more compelling in the awake (P < 0.01) compared with anesthetized (P < 0.05) animals.

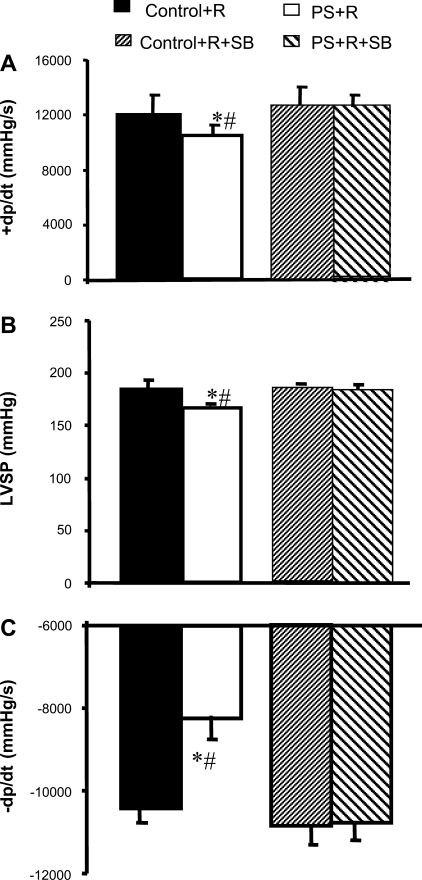

The phosphorylation of p38 MAP kinase plays a key role in signaling pathways activated in response to a variety of cellular stressors (3, 14, 15, 30, 34, 45). We previously reported (16) that addition of the p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB both reversed the baseline depression in % fractional shortening and attenuated β-adrenergic responses of cardiac myocytes isolated from PS+R in vitro. We inferred from these in vitro observations that the continuous activation/phosphorylation of p38 MAP kinase is required to depress contractility and attenuate adrenergic signaling in this novel PS+R cardiomyopathy model. In vivo studies to confirm the physiological relevance of these in vitro studies were not conducted. Accordingly, SB (5 mg/kg) was injected (ip) 24 h before catheter surgery in accordance with previously published reports demonstrating in vivo inhibition of p38 MAP kinase enzymatic activity (15). Injection of SB normalized baseline +dP/dt, LVSP, and −dP/dt in PS+R compared with Control+R (PS+R+SB vs. Control+R+SB, P = NS for each), while having no demonstrable effect on Control+R vs. Control+R+SB (P = NS; Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Bar graph depicting reversibility by the p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB of impaired systolic (+dP/dt, A; LVSP, B) and diastolic (−dP/dt, C) function of PS+R freely ambulatory awake rats. *P < 0.05, PS+R vs. PS+R+SB (n = 6–8); #P < 0.05, PS+R vs. Control+R (n = 6–8).

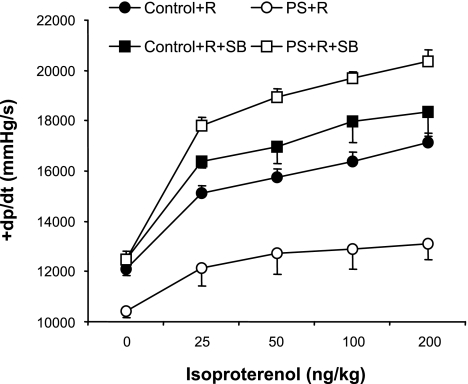

Attenuated response to β-adrenergic stimulation is a common characteristic of cardiomyopathies regardless of the etiology (17, 32, 46). We previously demonstrated (16) a blunted response to the β-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol in cardiac myocytes isolated from PS+R compared with Control+R. The effects of adrenergic stimulation in vivo were not determined. Accordingly, in vivo hemodynamic responses to increasing doses of isoproterenol injected into the right jugular vein were assessed in PS+R vs. Control+R (see Figs. 4–9). The positive inotropic response to β-adrenergic stimulation was significantly attenuated in PS+R compared with Control+R, as reflected in a depressed +dP/dt response to 25–200 ng/kg isoproterenol (P < 0.01; Fig. 4). SB treatment also reversed the attenuated +dP/dt response to isoproterenol in PS+R compared with Control+R (PS+R+SB vs. Control+R+SB, P = NS; Fig. 4). SB treatment had no effect on Control+R (Control+R vs. Control+R+SB, P = NS; Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Dose-response curves of systolic contractile function (+dP/dt) in response to increasing doses of the β-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol in prenatally stressed PS+R vs. Control+R (P < 0.01; n = 6–8). The p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB reversed the impaired systolic contractile response (+dP/dt) to increasing doses of isoproterenol in PS+R (PS+R vs. PS+R+SB, P < 0.01; n = 6–8). SB did not affect systolic contractile function (+dP/dt) in response to isoproterenol in Control+R [Control+R vs. Control+R+SB, P = not significant (NS); n = 6–8].

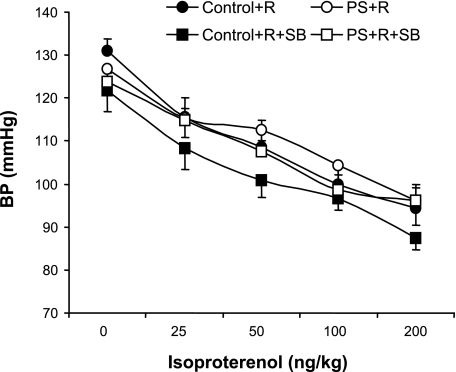

Fig. 9.

Dose-response curves of blood pressure (BP) in response to increasing doses of the β-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol in PS+R vs. Control+R (Control+R vs. PS+R, P = NS; n = 6–8) and no significant effect of the p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB on BP responses to increasing doses of isoproterenol in either PS+R (PS+R vs. PS+R+SB, P = NS) or Control+R (Control+R vs. Control+R+SB, P = NS, n = 6–8).

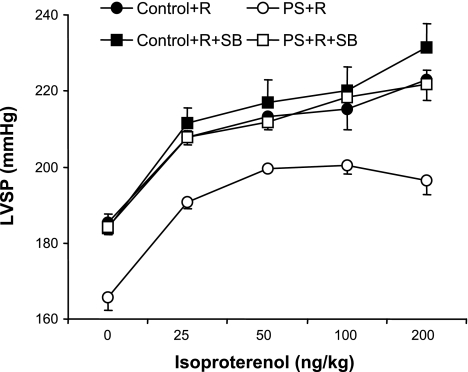

This difference in inotropic response to isoproterenol was sufficient to also be evident in a reduction in LVSP (P < 0.01; Fig. 5). SB treatment similarly reversed the attenuated LVSP dose response to isoproterenol in PS+R compared with Control+R (PS+R+SB vs. Control+R+SB, P = NS; Fig. 5). SB had no significant effects on LVSP response to isoproterenol by Control+R (Control+R vs. Control+R+SB, P = NS; Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Dose-response curves of LVSP in response to increasing doses of the β-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol in PS+R vs. Control+R (Control+R vs. PS+R, P < 0.01; n = 6–8). The p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB reversed the impaired LVSP response to isoproterenol in PS+R (PS+R+SB vs. PS+R, P < 0.01; n = 6–8). SB did not affect LVSP in response to isoproterenol in Control+R (Control+R vs. Control+R+SB, P = NS; n = 6–8).

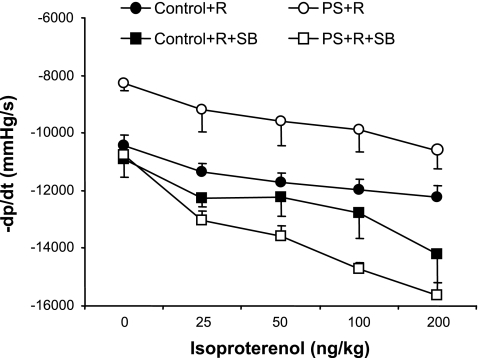

SB treatment significantly enhanced the diastolic/lusitropic response to isoproterenol infusion in PS+R (PS+R vs. PS+R+SB, P < 0.01; Fig. 6). SB had no significant effect on Control+R (Control+R vs. Control+R+SB, P = NS; Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Dose-response curves of diastolic function (−dP/dt) in response to increasing doses of the β-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol in PS+R vs. Control+R (Control+R vs. PS+R, P < 0.01; n = 6–8). The p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB reversed the impaired lusitropic/diastolic response (−dP/dt) to isoproterenol in PS+R (PS+R+SB vs. PS+R, P < 0.01). SB did not affect diastolic function in response to isoproterenol in Control+R (Control+R vs. Control+R+SB, P = NS; n = 6–8).

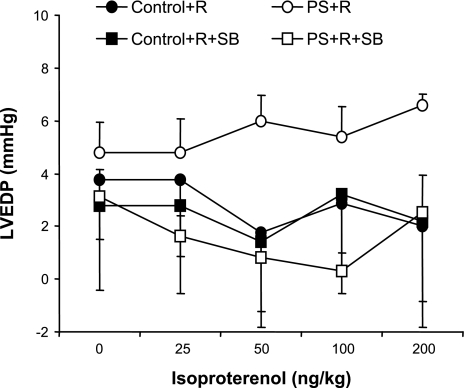

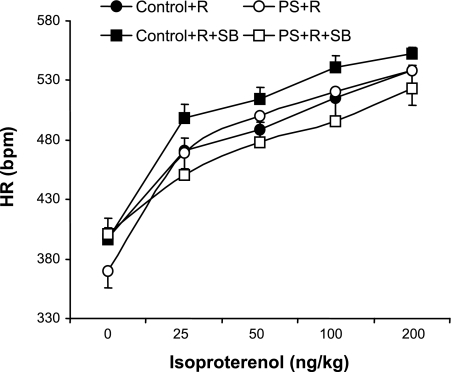

No significant differences in LVEDP, heart rate (chronotropic), and systemic blood pressure responses to injections of isoproterenol were demonstrable between PS+R and Control+R (P = NS for each; Figs. 7–9).

Fig. 7.

Dose-response curves of LVEDP in response to increasing doses of the β-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol in PS+R vs. Control+R (Control+R vs. PS+R, P = NS; n = 6–8). The p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB had no significant effect on LVEDP in response to increasing doses of isoproterenol in either PS+R (PS+R+SB vs. PS+R, P = NS) or Control+R (Control+R vs. Control+R+SB, P = NS; n = 6–8).

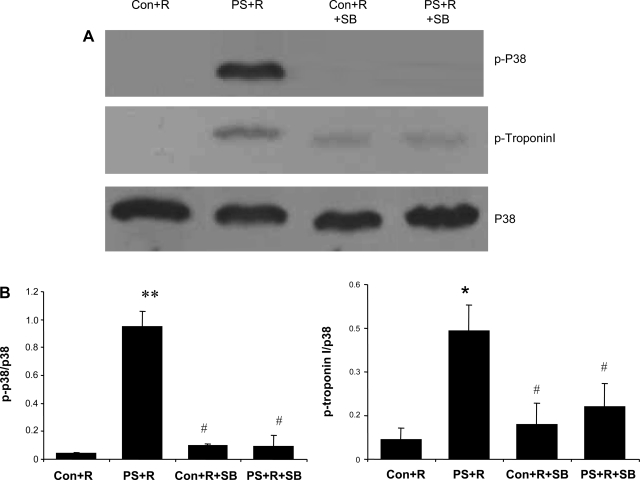

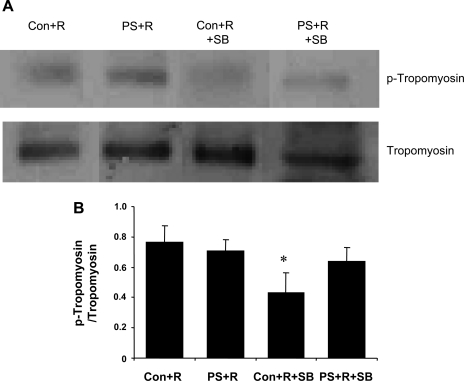

Western blot analyses confirmed that in vivo treatment with SB resulted in blocking p38 MAP kinase and troponin I phosphorylation in cardiac myocytes isolated from PS+R (Fig. 10). The correlation of biochemical evidence with physiological data further supports a role for a p38 MAP kinase mechanism in this animal model of reversible myocardial dysfunction. Alternative mechanisms for the effect of SB were sought by also assaying for potential alternative pharmacological targets identified in the literature (4, 13–15, 30, 34, 41, 43). No specific effect on the phosphorylation pattern for tropomyosin was observed after SB (Fig. 11).

Fig. 10.

A: representative Western blot illustrating the increase in phosphorylated p38 MAP kinase and troponin I in PS+R vs. Control+R. The p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB reversed the increase in phosphorylation of both p38 MAP kinase and troponin I in PS+R. B: results of densitometric analyses of experiments repeated 3 times independently with identical results (**P < 0.01,*P < 0.05, PS+R vs. Control+R; #P < 0.05, PS+R vs. Control+R+SB vs. PS+R+SB).

Fig. 11.

A: representative Western blot illustrating no differences in the phosphorylation of tropomyosin in PS+R vs. Control+R. The p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB also did not affect the phosphorylation of tropomyosin in PS+R. B: results of densitometric analyses of experiments repeated 3 times independently with identical results (*P < 0.05, Control+R vs. Control+R+SB).

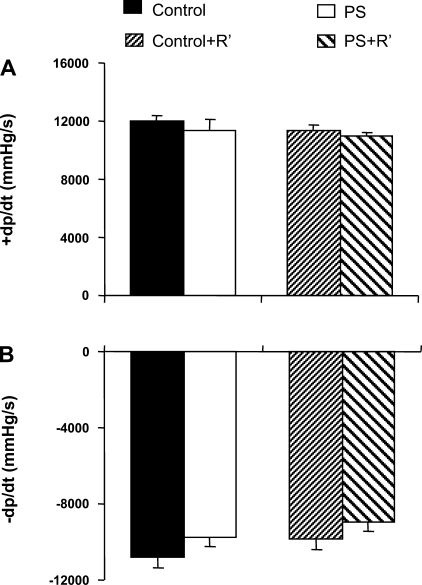

We previously reported (16) echocardiographic changes in PS+R vs. Control+R only after two successive restraints. We were unable to discern significant differences in prenatal stress (PS) alone or the combination of PS with a single restraint stress. We next sought to determine whether more subtle changes could be observed with catheter-based hemodynamic measurements. The absence of hemodynamic differences after PS alone or PS followed by a single restraint (PS+R′) was confirmed in freely ambulatory, awake rats (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12.

Bar graphs depicting lack of change in either systolic (+dP/dt, A) or diastolic (−dP/dt, B) function in prenatally stressed (PS) rats vs. control rats (Control vs. PS, P = NS; n = 6–8). In addition, no differences were seen between prenatally stressed rats subjected to only 1 restraint stress (PS+R′) vs. similarly restrained control rats (Control+R′) (Control+R′ vs. PS+R′, P = NS; n = 6–8) in the freely ambulatory awake state. +dP/dt = 12,010 ± 439, 11,400 ± 666, 11,362 ± 374, and 10,912 ± 328 mmHg/s for Control, PS, Control+R′, and PS+R′, respectively; −dP/dt = −10,818 ± 550, −9,724 ± 503, −9,875 ± 517, and −8,941 ± 535 mmHg/s for Control, PS, Control+R′, and PS+R′, respectively.

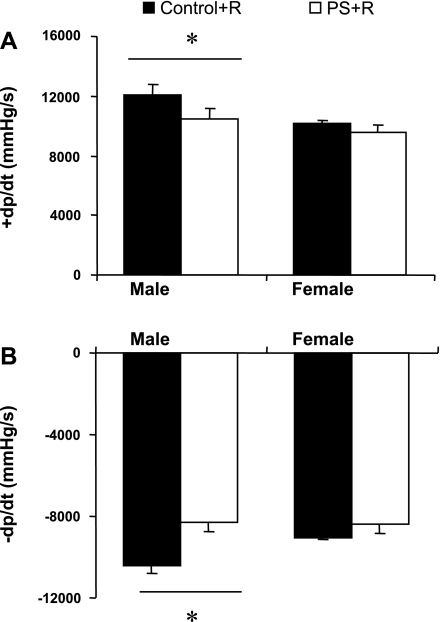

Behavioral changes described in this and other prenatal stress models consistently show more pronounced effects in male compared with female offspring of stressed dams (6, 11, 12, 41, 43). Accordingly, we similarly studied age-matched female PS+R compared with female Control+R (Fig. 13). Unlike males, no significant hemodynamic differences were observed between female PS+R and female Control+R. These findings are consistent with a relationship between the behavioral and hemodynamic abnormalities in this animal model. Potential mechanisms involved in preserving and/or preventing hemodynamic compromise among female PS+R remain to be elucidated.

Fig. 13.

Bar graph depicting differences in hemodynamic responses between male vs. female rats after PS+R. Both systolic and diastolic dysfunction were significant in male PS+R vs. male Control+R (Control+R vs. PS+R, *P < 0.05; n = 6–8). However, no such differences between age-matched female PS+R and female Control+R were observed (Control+R vs. PS+R, P = NS; n = 6–8). +dP/dt = 12,110 ± 652 vs. 10,438 ± 741 mmHg/s, −dP/dt = −10,440 ± 364 vs. −8,287 ± 444 mmHg/s, male Control+R vs. PS+R, respectively; +dP/dt = 10,169 ± 220 vs. 9,582 ± 438 mmHg/s, −dP/dt = −9,036 ± 119 vs. −8,391 ± 412 mmHg/s, female Control+R vs. PS+R, respectively.

DISCUSSION

We provide compelling in vivo evidence of reversible myocardial dysfunction following a combination of prenatal stress followed by restraint stress (PS+R) in both anesthetized and freely mobile, awake rats. More specifically, we have demonstrated that the combination of prenatal stress followed by restraint stress (PS+R) results in 1) depressed systolic function (+dP/dt and LVSP), 2) depressed diastolic function (−dP/dt), 3) attenuated positive inotropic (+dP/dt) responses to β-adrenergic stimulation with isoproterenol, 4) attenuated negative inotropic (lusitropic; −dP/dt) responses to β-adrenergic stimulation with isoproterenol, 5) reversal of baseline hemodynamic changes with the p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB, 6) reversal of attenuated hemodynamic responses to isoproterenol with the p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB, 7) p38 MAP kinase and troponin I phosphorylation in cardiac myocytes isolated from PS+R but not Control+R, and 8) reversal of p38 MAP kinase and troponin I phosphorylation in cardiac myocytes isolated from PS+R with the p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB. The most likely and consistent explanation for these observations is that continuous activation of p38 MAP kinase plays a critical pathophysiological role in this animal model of stress-induced reversible myocardial dysfunction.

These compelling data confirm, complement, and considerably extend and expand our initial report of echocardiographic evidence of a decrease in fractional shortening in anesthetized PS+R (16). The performance of echocardiograms in rats has both advantages and disadvantages. Advantages include the capability of performing repeated measures over time in the same animal model with a technique that is currently widely accepted to diagnose and manage cardiomyopathies in patients. However, animals must be sedated under general anesthesia to perform echocardiograms of adequate quality to obtain reliable, reproducible, quantitative measurements. The impact of general anesthesia on hemodynamics can be considerable and was a potential source of artifact in our initial observations in this PS+R model. We were particularly concerned about this possibility in view of the novel nature of our initial observations (i.e., new cardiomyopathy model). The profound and consistent adverse impact of general anesthesia on in vivo baseline hemodynamics was confirmed by our present study (Table 1). Both systolic and diastolic function were diminished in both PS+R and Control+R under general anesthesia compared with the freely ambulatory, awake state in the same animals (P < 0.05 for each parameter). Our hemodynamic data now provide more rigorous and better-quantified confirmation of our echocardiographic data by demonstrating decreased +dP/dt and LVSP in PS+R vs. Control+R under general anesthesia (P < 0.05; Table 1). Importantly, we now also report the persistence of the difference in contractility (+dP/dt) between PS+R and Control+R in the freely mobile, awake animals (P < 0.01; Table 1). These findings alone provide much more compelling evidence of the physiological and clinical relevance of this novel cardiomyopathy model. In addition, the technique is sufficiently versatile and quantitative to clearly demonstrate significant impairment in diastolic function (−dP/dt) as well (Table 1).

Further confirmation of the physiological and clinical relevance of this cardiomyopathy model is the demonstration of attenuated adrenergic signaling in vivo (Figs. 4–9). Attenuated adrenergic signaling is a common characteristic shared by human and animal cardiomyopathies of diverse etiologies (16, 32, 46). Accordingly, we compared the inotropic, lusitropic, and chronotropic effects of increasing doses of intravenous isoproterenol infusions between PS+R and Control+R. Consistent with other cardiomyopathies, inotropic (+dP/dt; LVSP) and lusitropic (−dP/dt) responses to isoproterenol were significantly blunted in PS+R compared with Control+R (P < 0.05 for +dP/dt, LVSP, −dP/dt; Figs. 4–6). These observations are also consistent with our previous report of attenuated isoproterenol responses of cardiac myocytes isolated from PS+R rats compared with Control+R rats (16). In vitro observations in cardiomyocytes have considerable potential for the introduction of observation bias based on cell selection and artifact from cell preparation. Therefore, the confirmation of a blunted inotropic response to isoproterenol in vivo provides much more convincing and compelling evidence that the combination of prenatal stress followed by restraint stress results in a novel cardiomyopathy model that shares the characteristics of previously identified animal and human cardiomyopathies.

Potential molecular signaling pathways mediating stress-induced reversible myocardial dysfunction is an active area of investigation. Possible mediators implicated in this process include immediate-early genes (IEG), calcium leakage from ryanodine receptor 2 (RyR2), catecholamine-induced free radicals, p44/42 MAP kinases, heat shock proteins (HSPs), atrial natriuretic peptides (ANP), brain natriuretic peptides (10, 31, 36, 37), and so on. We (16, 21) and others (3, 15, 34, 45) have previously provided evidence of a possible role for a p38 MAP kinase signaling pathway in myocardial dysfunction. p38 MAP kinase is known to phosphorylate proteins in response to inflammatory mediators, such as cytokines, and stressors, such as ischemia (3, 14, 15, 30, 34, 45). Accumulating evidence has been forthcoming that p38 MAP kinase mediates a negative inotropic effect on cardiac myocytes (16, 24, 25). Prolonged and persistent activation of p38 MAP kinase by emotional stress could contribute to myocardial dysfunction and progression to overt heart failure.

We (18) and others (25)have provided evidence that p38 MAP kinase mediates its negative inotropic effect independent of changes in intracellular ionized free calcium. Selective inhibition of p38 MAP kinase in vitro enhanced contractility associated with changes in pH, but not calcium transients or calcium membrane currents (25). A calcium-independent effect suggests an effect of p38 MAP kinase on the affinity of contractile proteins for calcium. However, no suitable phosphorylation site for p38 MAP kinase has been identified on contractile proteins. We have previously (18) provided evidence in an human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) cardiomyopathy model that p38 MAP kinase participates in an upstream process that culminates in troponin I phosphorylation.

We previously reported (16) that the addition of the p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB to cardiac myocytes isolated from PS+R reversed the negative inotropic effect and blunted adrenergic signaling defects. The reversal of p38 MAP kinase phosphorylation by SB was correlated with reversal of defective adrenergic signaling in vitro. In vivo studies were not performed. We now report that the injection of SB in vivo normalized baseline +dP/dt, LVSP, and −dP/dt in PS+R (P < 0.05 for each), while having no demonstrable effect on Control+R (Fig. 3). These observations alone provide considerably more rigorous and quantitative evidence of an essential role for p38 MAP kinase in the myocardial dysfunction resulting from a combination of prenatal stress followed by restraint stress. Further evidence of a central role for p38 MAP kinase is that treatment of PS+R with SB also reversed the attenuated response to the adrenergic agonist isoproterenol. Thus treatment with a p38 MAP kinase inhibitor can reverse and normalize hemodynamic abnormalities in an animal model after overt manifestations of classic features of a cardiomyopathy.

The specificity of the effect of SB on p38 MAP kinase is supported by Western blots that correlate reversal of p38 MAP kinase and troponin I phosphorylation by SB with reversal of baseline hemodynamic abnormalities and defective adrenergic signaling in PS+R (Fig. 10). However, alternative possibilities have not been definitively excluded. Evidence of an effect of SB on tropomyosin phosphorylation could present a plausible alternative (39). The absence of an effect of SB on tropomyosin phosphorylation reduces that likelihood in our model (Fig. 11). Recent reports raise the intriguing possibility that SB mediates effects through inhibition of p38 MAP kinase-mediated cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 activity (4, 13, 19, 35). Initial reports of direct effects of SB on COX-2 in vitro suggested that the enzyme inhibitor was less selective for p38 MAP kinase (4). However, more recent studies indicate that SB actually mediates effects on COX-2 in cell systems indirectly via inhibition of p38 MAP kinase (19, 35). Similarly, SB has been reported to inhibit and/or enhance cRAF in vitro versus in cell systems (13). Therefore, a potential role for additional p38 MAP kinase targets other than troponin I may need to be considered. However, the dose of 5 mg/kg translates into a maximum systemic concentration of 18 μM, assuming ∼75% volume/wt. This corresponds well to the 10 μM concentration we previously used with isolated cardiac myocytes in vitro to reverse adrenergic signaling defects in PS+R (16). Higher concentrations than these have been used to identify “nonspecific” effects of SB. As noted above, nonspecific effects may need to be distinguished from newly identified relationships between signaling pathways uncovered by the inhibitor.

There is evidence supporting a role for adrenergic activation in the pathogenesis of emotional stress-induced myocardial dysfunction (36). Studies have also reported that isoproterenol mediates effects through p38 MAP kinase (1). In adult mouse cardiac myocytes, β2-adrenoceptor stimulation by isoproterenol induces a time- and dose-dependent increase in p38 MAP kinase activation that may be attributable to the Gs-adenylyl cyclase-PKA pathway (43). Activated p38 MAP kinase appears to provide a negative feedback to its upstream, PKA-mediated contractile response. Inhibition of p38 MAP kinase by SB significantly enhances β2-adrenoceptor-mediated contractile response in vitro (47). In the present study, PS+R blunted the dose response to isoproterenol and SB enhanced the response in vivo. These in vivo findings are compatible with the in vitro data revealing the enhancement of the positive inotropic effect of isoproterenol in the presence of SB.

The prenatally stressed (PS) rat has gained widespread acceptance as an animal model for mood disorders (6, 8, 11, 41–43). Behavioral disturbances indicative of increased fearfulness have been demonstrated in offspring of rats that are subjected to behavioral stress during pregnancy (PS). Various modifications of the PS paradigm have been developed with different specific stressors. A common feature of these PS variants is enhanced sympathoadrenal activation in response to stressful stimuli (7, 12). Features similar to those seen in PS rats occur in offspring of human expectant mothers subjected to psychosocial stress (26, 33, 40). These include developmental delay and behavioral disturbances such as excessive clinging, crying, hyperactivity, attention deficits, and unsociable behavior. Similar behavioral disturbances are observed in nonhuman primates that have undergone prenatal or early postnatal stress (7). Biochemical disturbances observed in the nonhuman primate models of maternal stress include elevations of the anxiogenic neuropeptide CRF and increased metabolites of serotonin and dopamine in cerebrospinal fluid. A relationship between the neurochemical abnormalities documented in PS and the development of a cardiomyopathy remains to be explored. It is particularly interesting that male PS animals manifest more severe behavioral symptomatology and greater hemodynamic abnormalities than female PS animals (26). This animal model provides the opportunity to explore mechanisms responsible for the relationship between hormonal effects on behavior and their effects on cardiac hemodynamics.

The potential clinical relevance of our observations in the PS rat model is underscored by reports of patients presenting with new onset of unexplained reversible myocardial dysfunction after episodes of emotional stress (22, 29, 44). This model appears to share additional features with patients who suffer reversible myocardial depression after emotional stress. Wittstein and colleagues (44) investigated 19 patients who suffered reversible myocardial dysfunction after emotional stress. Almost all of these patients had surprisingly low heart rates considering their low systemic blood pressures, cardiac outputs, and elevated catecholamine levels. The PS+R rats also appear to have relatively low heart rates. These features may reflect defects in central nervous system, autonomic, or hormonal regulation of cardiovascular function that remain to be elucidated. Future studies in this animal model may provide insights into the basic mechanisms contributing to reversible myocardial dysfunction in patients after emotional stress. In addition, myocardial dysfunction resulting solely from emotional stress may be an extreme example of a more common confounding effect of emotional stress on myocardial function. Thus this animal model may provide a unique opportunity to elucidate basic mechanisms involved in myocardial dysfunction in more commonly diagnosed cardiomyopathies as well.

GRANTS

This work was supported by a Department of Veterans Affairs MERIT Award and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant RO-1-HL-70565.

Fig. 8.

Dose-response curves of heart rate (HR) response to increasing doses of the β-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol in PS+R vs. Control+R (Control+R vs. PS+R, P = NS; n = 6–8) and the effects of the p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB on HR in response to increasing doses of isoproterenol in PS+R (PS+R vs. PS+R+SB, P < 0.05). SB did not affect HR in response to isoproterenol in Control+R (Control+R vs. Control+R+SB, P = NS; n = 6–8). bpm, Beats per minute.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aggeli IK, Gaitanaki C, Lazou A, Beis I. Alpha1- and beta-adrenoceptor stimulation differentially activate p38-MAPK and atrial natriuretic peptide production in the perfused amphibian heart. J Exp Biol 205: 2387–2397, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bacon SL, Sherwood A, Hinderliter AL, Coleman RE, Waugh R, Blumenthal JA. Changes in plasma volume associated with mental stress ischemia in patients with coronary artery disease. Int J Psychophysiol 61: 143–148, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ballard-Croft C, Locklar AC, Keith BJ, Mentzer RM Jr, Lasley RD. Oxidative stress and adenosine A1 receptor activation differentially modulate subcellular cardiomyocyte MAPKs. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H263–H271, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Börsch-Haubold AG, Pasquet S, Watson SP. Direct inhibition of cyclooxygenase-1 and -2 by the kinase inhibitors SB 203580 and PD 98059. SB 203580 also inhibits thromboxane synthase. J Biol Chem 273: 28766–28772, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Y, Rajashree R, Liu Q, Hoffman P. Acute p38 MAPK activation decreases force development in ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H2578–H2586, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clinton S, Miller S, Watson SJ, Akil H. Prenatal stress does not alter innate novelty-seeking behavioral traits, but differentially affects individual differences in neuroendocrine stress responsivity. Psychoneuroendocrinology 33: 162–177, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coplan JD, Andrews MW, Rosenblum LA, Owens MJ, Friedman S, Gorman JM, Nemeroff CB. Persistent elevations of cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of corticotropin-releasing factor in adult nonhuman primates exposed to early-life stressors: implications for the pathophysiology of mood and anxiety disorders. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 1619–1623, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cratty MS, Ward HE, Johnson EA, Azzaro AJ, Birkle DL. Prenatal stress increases corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) content and release in rat amygdala minces. Brain Res 675: 297–302, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Derian W, Soundarraj D, Rosenberg MJ. Stress-induced cardiomyopathy: not always apical ballooning. Rev Cardiovasc Med 8: 228–233, 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ellison GM, Torella D, Karakikes I, Purushothaman S, Curcio A, Gasparri C, Indolfi C, Cable NT, Goldspink DF, Nadal-Ginard B. Acute β-adrenergic overload produces myocyte damage through calcium leakage from the ryanodine receptor 2 but spares cardiac stem cells. J Biol Chem 282: 11397–11409, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fride E, Dan Y, Feldon J, Halevy G, Weinstock M. Effects of prenatal stress on vulnerability to stress in prepubertal and adult rats. Physiol Behav 37: 681–687, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fride E, Weinstock M. Prenatal stress increases anxiety-related behavior and alters cerebral lateralization of dopamine activity. Life Sci 42: 1059–1065, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall-Jackson CA, Goedert M, Hedge P, Cohen P. Effect of SB 203580 on the activity of c-Raf in vitro and in vivo. Oncogene 18: 2047–2054, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson G, Lapadat R. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways mediated by ERK, JNK, and p38 protein kinases. Science 298: 1911–1912, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joyeux M, Boumendjel A, Carroll R, Ribuot C, Godin-Ribuot D, Yellon DM. SB 203580, a mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitor, abolishes resistance to myocardial infarction induced by heat stress. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 14: 337–343, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kan H, Birkle D, Jain AC, Failinger C, Xie S, Finkel MS. p38 MAP kinase inhibitor reverses stress-induced cardiac myocyte dysfunction. J Appl Physiol 98: 77–82, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kan H, Finkel MS. Inflammatory mediators and reversible myocardial dysfunction. J Cell Physiol 195: 1–11, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kan H, Xie Z, Finkel MS. iPLA2 inhibitor blocks negative inotropic effect of HIV gp120 on cardiac myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 40: 131–137, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kellogg AP, Converso K, Wiggin TD, Stevens MJ, Pop-Busui R. Effects of cyclooxygenase-2 gene inactivation on cardiac autonomic and left ventricular function in experimental diabetes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 296: H453–H461, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khanna D, Kan H, Failinger C, Jain AC, Finkel MS. Emotional stress and reversible myocardial dysfunction. Cardiovasc Toxicol 6: 183–198, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khanna D, Kan H, Fang Q, Xie Z, Underwood BL, Jain AC, Williams HJ, Finkel MS. Inducible nitric oxide synthase attenuates adrenergic signaling in alcohol fed rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 50: 692–696, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurisu S, Sato H, Kawagoe T, Ishihara M, Shimatani Y, Nishioka K, Kono Y, Umemura T, Nakamura S. Tako-tsubo-like left ventricular dysfunction with ST-segment elevation: a novel cardiac syndrome mimicking acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 143: 448–455, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee YP, Poh KK, Lee CH, Tan HC, Razak A, Chia BL, Low AF. Diverse clinical spectrum of stress-induced cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol (January 10, 2008); doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Liao P, Georgakopoulos D, Kovacs A, Zheng M, Lerner D, Pu H, Saffitz J, Chien K, Xiao RP, Kass DA, Wang Y. The in vivo role of p38 MAP kinases in cardiac remodeling and restrictive cardiomyopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 12283–12288, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liao P, Wang SQ, Wang S, Zheng M, Zheng M, Zhang SJ, Cheng H, Wang Y, Xiao RP. p38 Mitogen-activated protein kinase mediates a negative inotropic effect in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res 90: 190–196, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meijer A Child psychiatric sequelae of maternal war stress. Acta Psychiatr Scand 72: 505–511, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murata J, Matsukawa K, Shimizu J, Matsumoto M, Wada T, Ninomiya I. Effects of mental stress on cardiac and motor rhythms. J Auton Nerv Syst 75: 32–37, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sawai A, Ohshige K, Yamasue K, Hayashi T, Tochikubo O. Influence of mental stress on cardiovascular function as evaluated by changes in energy expenditure. Hypertens Res 30: 1019–1027, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharkey SW, Lesser JR, Zenovich AG, Maron MS, Lindberg J, Longe TF, Maron BJ. Acute and reversible cardiomyopathy provoked by stress in women from the United States. Circulation 111: 472–479, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi Y, Gaestel M. In the cellular garden of forking paths: how p38 MAPKs signal for downstream assistance. Biol Chem 383: 1519–1536, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singal PK, Kapur N, Dhillon KS, Beamish RE, Dhalla NS. Role of free radicals in catecholamine-induced cardiomyopathy. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 60: 1390–1397, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spinale FG, Tempel GE, Mukherjee R, Eble DM, Brown R, Vacchiano CA, Zile MR. Cellular and molecular alterations in the beta adrenergic system with cardiomyopathy induced by tachycardia. Cardiovasc Res 28: 1243–1250, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stott DH Follow-up study from birth of the effects of prenatal stress. Dev Med Child Neurol 15: 770–787, 1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sugden PH, Clerk A. “Stress-responsive” mitogen-activated protein kinases (c-Jun N-terminal kinases and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases) in the myocardium. Circ Res 83: 345–352, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun H, Xu B, Inoue H, Chen QM. p38 MAPK mediates Cox-2 gene expression by corticosterone in cardiomyocytes. Cell Signal 20: 1952–1959, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ueyama T Emotional stress-induced Tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy: animal model and molecular mechanism. Ann NY Acad Sci 1018: 437–444, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ueyama T, Senba E, Kasamatsu K, Hano T, Yamamoto K, Nishio I, Tsuruo Y, Yoshida K. Molecular mechanism of emotional stress-induced and catecholamine-induced heart attack. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 41, Suppl 1: S115–S118, 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ueyama T, Yoshida KI, Senba E. Emotional stress induces immediate-early gene expression in rat heart via activation of α- and β-adrenoceptors. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 277: H1553–H1561, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vahebi S, Ota A, Li M, Warren CM, de Tombe PP, Wang Y, Solaro RJ. p38-MAPK induced dephosphorylation of alpha-tropomyosin is associated with depression of myocardial sarcomere tension and ATPase activity. Circ Res 100: 408–415, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ward AJ Prenatal stress and child psychopathology. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 22: 97–110, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ward HE, Johnson EA, Salm AK, Birkle DL. Effects of prenatal stress on defensive withdrawal behavior and corticotropin releasing factor systems in rat brain. Physiol Behav 70: 359–366, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weinstock M, Poltyrev T, Schorer-Apelbaum D, Men D, McCarty R. Effect of prenatal stress on plasma corticosterone and catecholamines in response to foot shock in rats. Physiol Behav 64: 439–444, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weinstock M Does prenatal stress impair coping and regulation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis? Neurosci Biobehav Rev 21: 1–10, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wittstein IS, Thiermann DR, Lima JAC, Baughman KL, Schulman SP, Gerstenblith G. Neurohumoral features of myocardial stunning due to sudden emotional stress. N Engl J Med 352: 539–548, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang M, Wu J, Martin CM, Kvietys PR, Rui T. Important role of p38 MAP kinase/NF-kappaB signaling pathway in the sepsis-induced conversion of cardiac myocytes to a proinflammatory phenotype. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H994–H1001, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu Z, McNeill JH. Altered inotropic responses in diabetic cardiomyopathy and hypertensive-diabetic cardiomyopathy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 257: 64–71, 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zheng M, Zhang SJ, Zhu WZ, Ziman B, Kobilka BK, Xiao RP. Beta2-adrenergic receptor-induced p38 MAPK activation is mediated by protein kinase A rather than by Gi or Gbetagamma in adult mouse cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem 275: 40635–40640, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]