Abstract

GABAA channels are ubiquitously expressed on neuronal cells and act via an inward chloride current to hyperpolarize the cell membrane of mature neurons. Expression and function of GABAA channels on airway smooth muscle cells has been demonstrated in vitro. Airway smooth muscle cell membrane hyperpolarization contributes to relaxation. We hypothesized that muscimol, a selective GABAA agonist, could act on endogenous GABAA channels expressed on airway smooth muscle to attenuate induced increases in airway pressures in anesthetized guinea pigs in vivo. In an effort to localize muscimol's effect to GABAA channels expressed on airway smooth muscle, we pretreated guinea pigs with a selective GABAA antagonist (gabazine) or eliminated lung neural control from central parasympathetic, sympathetic, and nonadrenergic, noncholinergic (NANC) nerves before muscimol treatment. Pretreatment with intravenous muscimol alone attenuated intravenous histamine-, intravenous acetylcholine-, or vagal nerve-stimulated increases in peak pulmonary inflation pressure. Pretreatment with the GABAA antagonist gabazine blocked muscimol's effect. After the elimination of neural input to airway tone by central parasympathetic nerves, peripheral sympathetic nerves, and NANC nerves, intravenous muscimol retained its ability to block intravenous acetylcholine-induced increases in peak pulmonary inflation pressures. These findings demonstrate that the GABAA agonist muscimol acting specifically via GABAA channel activation attenuates airway constriction independently of neural contributions. These findings suggest that therapeutics directed at the airway smooth muscle GABAA channel may be a novel therapy for airway constriction following airway irritation and possibly more broadly in diseases such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Keywords: acetylcholine, histamine, vagal nerve stimulation, gabazine, guanethidine

there has been a global increase in the incidence of asthma in the last 20 years (4). Current asthma treatment focuses on avoiding triggers, reducing the incidence of exacerbations, and limiting airway inflammation and chronic remodeling. There have been few new developments in the pharmacological armamentarium against asthma over the last two decades and a paucity of new developments in the treatment of acute airway smooth muscle constriction, which is essential in the treatment of acute exacerbations.

Recently, our laboratory identified γ-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) channels in human and animal airway smooth muscle (12). Activation of GABAA channels in mature central nervous system neurons results in an inward chloride flux resulting in hyperpolarization of the cell membrane (2). In airway smooth muscle, plasma membrane hyperpolarization favors relaxation (11). Although in vitro studies of endogenous airway smooth muscle GABAA channels demonstrate relaxation of substance P- and histamine-induced contraction by a specific GABAA agonist (12) and potentiation of β-adrenergic relaxation of acetylcholine contractions in human airway smooth muscle (6), the functional role of GABAA channel activation on induced airway constriction in vivo is unclear.

Because in vitro studies do not always model drug effects in vivo, we questioned whether a GABAA agonist would relax airway constriction in vivo. In the current studies, we hypothesized that muscimol, a specific GABAA agonist, would relax airway constriction induced by intravenous acetylcholine, intravenous histamine, or electrical vagal nerve stimulation in this in vivo model of reflex bronchoconstriction. In an attempt to demonstrate a direct effect of muscimol on the GABAA channel on airway smooth muscle in vivo, we eliminated central parasympathetic, postganglionic sympathetic, and inhibitory nonadrenergic, noncholinergic (NANC) neural contributions to airway tone.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal model.

Male Hartley guinea pigs (∼400 g) were anesthetized and instrumented in this established model of airway inflation pressure measurements (5, 10, 14) in protocols previously described (10) and approved by the Columbia University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Anesthesia was induced by intraperitoneal injection of urethane (1.5 g/kg) and increased by 0.5 g ip until lack of foot pinch response before the start of the procedure. Urethane was chosen for its long duration of action (∼10 h) and lack of influence on respiratory nerve function (7). Animals received a tracheostomy with a 1-in. 14-g angiocatheter attached to a microventilator (model 683; Harvard Apparatus, South Natick, MA; IMV, volume control, tidal volume 2.6 ml, 66 breaths/min). The ventilator circuit was connected via side ports to two separate pressure monitors with different sensitivities (TSD160B 0–12.5 cmH2O and TSD160C 0–25 cmH2O; Biopac Systems, Goleta, CA) using rigid pressure tubing and was continuously monitored and recorded using Acqknowledge software. Animals then received bilateral external jugular catheters by using PE-50 tubing for a continuous succinylcholine infusion (5 mg·kg−1·h−1), started after a bolus of 1.5 mg/kg to remove any influence of chest wall or diaphragm muscle tone on airway pressures, and an independent catheter for delivery of study drugs. A carotid arterial line was placed to monitor blood pressure and heart rate and to ensure adequate depth of anesthesia by monitoring hemodynamic responses. Vagus nerves were dissected and tied with suture bilaterally, but not transected, to interrupt transmission along the nerve. In vagal nerve stimulation experiments, the distal ends of the vagus nerves were attached to electrodes and electrically isolated.

After preparation, each animal received increasing stimuli of intravenous acetylcholine (4–28 μg/kg; n = 4), intravenous histamine (2–24 μg/kg; n = 7), or electrical vagal nerve stimulation (10–20 V, 10–20 Hz, 0.2-ms pulse width, 7-s durations; n = 5) at 5-min intervals (Grass Instrument S88 Stimulator; Quincy, MA) until consistent increases in peak pulmonary inflation pressures (Ppi; 50–100% above baseline) were achieved. This optimized stimulus was administered three times and averaged for the control response. The magnitude of the response was calculated as the difference between the baseline and stimuli-induced Ppi. After control responses to stimuli were obtained, muscimol in doses ranging from 3.75 to 375 μg/kg iv was given 1 min before each subsequent stimulus. The response to a stimulus after muscimol was calculated as the difference between Ppi after muscimol but immediately before a stimulus (baseline Ppi) and compared with the control stimulus-induced Ppi. Separate groups of animals were used for each agent to induce airway constriction, and new groups of animals were used for the experiments of GABAA antagonism or nerve blockade detailed below for a total of 28 animals.

Effects of intravenous GABAA antagonist before intravenous muscimol on intravenous acetylcholine-induced increases in Ppi.

In separate experiments, guinea pigs (n = 6) were pretreated with gabazine (3.75 mg/kg iv), a selective GABAA antagonist, 10 min before control values for intravenous acetylcholine-induced increase in Ppi were established. Muscimol (187 μg/kg iv) was given 1 min before a subsequent intravenous acetylcholine challenge.

Elimination of neural contributions before assessing muscimol's effect on intravenous acetylcholine-induced increases in Ppi.

To determine whether muscimol is acting directly at airway smooth muscle or mediating its effect through central parasympathetic, peripheral sympathetic, or peripheral NANC neural pathways, these pathways were suppressed by ligation of the vagus nerve (central parasympathetic) and pharmacologically depleted of contents by treatment with capsaicin (20 μg/kg iv twice, 20 min apart; NANC), and guanethidine (10 mg/kg iv; postganglionic sympathetic) (n = 6). After a 20-min equilibration period, control values for intravenous acetylcholine-induced increase in Ppi were established. A single dose of muscimol (18.75 μg/kg) was given 1 min before the subsequent dose of acetylcholine. To confirm sustained sympathetic nerve depletion by guanethidine, animals were administered tyramine (10 mg/kg iv) and blood pressure effects were determined.

Statistical analysis.

Data were analyzed using repeated-measures ANOVA with significance at P < 0.05, and values are means ± SE obtained via GraphPad Instat software version 3.01.

Materials.

Urethane, acetylcholine, histamine, muscimol, capsaicin, and gabazine were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Acetylcholine, histamine, muscimol, and gabazine were diluted in lactated Ringer to 0.15 ml per dose. Capsaicin was suspended in DMSO at 2 μg/μl and then diluted in lactated Ringer to 8 μg/0.15 ml (20 μg/kg). Urethane was diluted in lactated Ringer to 1 g/ml. Succinylcholine (Hospira, Lake Forest, IL) was diluted in lactated Ringer to 1 mg/ml and continuously infused via a Medfusion 2010 microinfuser pump (Medex, Kensington, MD).

RESULTS

GABAA agonist pretreatment reduces the increase in Ppi induced by intravenous acetylcholine.

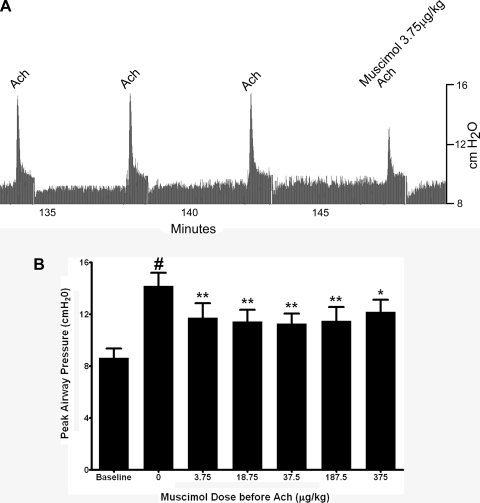

A representative airway pressure tracing is presented in Fig. 1A that illustrates the transient and reproducible increase in Ppi induced by intravenous acetylcholine and the attenuation of the acetylcholine response by a single dose of intravenous muscimol given 1 min before acetylcholine. The optimized dose of acetylcholine to achieve three reproducible increases in Ppi before muscimol varied between 4 and 28 μG/kg acetylcholine in individual animals. Pretreatment doses of muscimol (3.75–375 μg/kg) were given 1 min before the optimized acetylcholine dose in each animal. Although individual animals demonstrated a dose response to muscimol, the dose response for muscimol varied among animals, likely because of the variation in the optimized dose of acetylcholine among animals. The combined effects of muscimol doses in four animals are shown in Fig. 1B, where all concentrations of muscimol evaluated significantly suppressed the acetylcholine-induced increase in Ppi by ∼50%. Among the study animals (n = 4), the average baseline Ppi before acetylcholine challenge was 8.62 ± 0.029 cmH2O. Acetylcholine alone (4–28 μg/kg iv) caused a transient and consistent increase in Ppi of 5.55 ± 0.56 cmH2O above baseline. Muscimol (3.75–187 μg/kg) pretreatment 1 min before a subsequent intravenous acetylcholine challenge significantly decreased the acetylcholine-induced increase in Ppi at each dose tested (P < 0.001, n = 4) (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

A: representative airway pressure tracing in a guinea pig of intravenous acetylcholine (ACh)-induced increases in airway pressure. After 3 consistent increases in pulmonary inflation pressure (Ppi) by 8 μg/kg iv ACh, muscimol (3.75 μg/kg) pretreatment 1 min before a subsequent intravenous ACh challenge attenuated the ACh-induced increase in airway pressure. B: transient increases in Ppi following intravenous ACh in guinea pig airways in vivo before and after intravenous muscimol (3.75–375 μg/kg). Muscimol (3.75–375 μg/kg) significantly attenuated ACh-induced increases in Ppi. Values are means ± SE (n = 4). *P < 0.01; **P < 0.001 compared with no muscimol (ACh alone). #P < 0.001 compared with baseline.

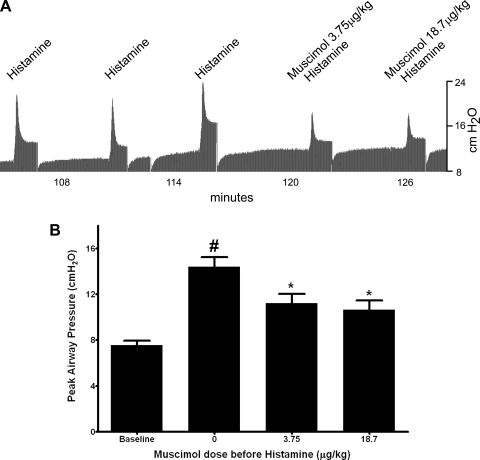

GABAA agonist pretreatment reduces intravenous histamine-induced increases in Ppi.

A representative airway pressure tracing is presented in Fig. 2A illustrating the transient and reproducible increase in Ppi induced by three control doses of intravenous histamine and the attenuation of the histamine-induced increase in airway pressure by intravenous muscimol (3.75 or 18.7 μg/kg) given 1 min before histamine. Average baseline Ppi before histamine in the study group (n = 7) was 7.55 ± 0.06 cmH2O. Histamine alone (2–24 μg/kg) caused a transient and consistent increase of 6.83 ± 0.59 cmH2O in Ppi above baseline. Pretreatment with intravenous muscimol (3.75 or 18.7 μg/kg) 1 min before a subsequent histamine challenge significantly attenuated the increase in peak Ppi in response to histamine by ∼50% (P < 0.001, n = 7) (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

A: representative airway pressure tracing in a guinea pig of intravenous histamine-induced increases in Ppi. After 3 consistent increases in Ppi by 16 μg/kg iv histamine, muscimol (3.75 or 18.7 μg/kg) pretreatment 1 min before a subsequent intravenous histamine challenge attenuated the histamine-induced increase in airway pressure. B: transient increases in Ppi following intravenous histamine in guinea pig airways in vivo before and after intravenous muscimol (3.75 or 18.7 μg/kg). Muscimol (3.75 or 18.7 μg/kg) significantly attenuated histamine-induced increases in Ppi. Values are means ± SE (n = 7). *P < 0.001 compared with no muscimol (histamine alone). #P < 0.001 compared with baseline.

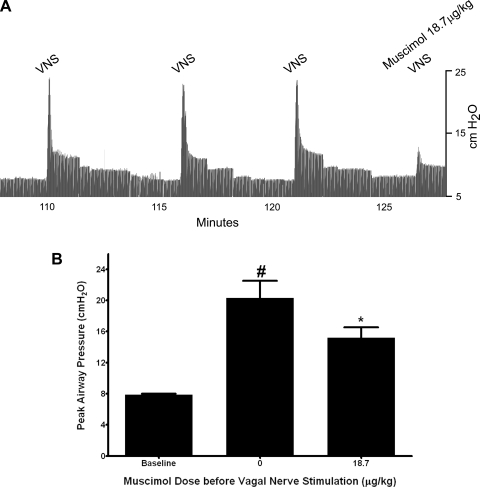

GABAA agonist pretreatment reduces vagal nerve-induced increases in Ppi.

Figure 3A is a representative tracing of airway inflation pressure showing reproducible increases in airway pressure in response to three repeated control vagal nerve stimulations that are attenuated by muscimol (18.7 μg/kg) given 1 min before a fourth vagal nerve stimulus. Vagal nerve stimulation caused a transient and consistent increase in Ppi of 12.42 ± 2.26 cmH2O from an average baseline Ppi of 7.86 ± 0.15 cmH2O. Pretreatment with intravenous muscimol (18.75 μg/kg) 1 min before a subsequent vagal nerve stimulation significantly decreased the vagal nerve-induced increases in Ppi by 54% to an increase of only 6.78 ± 1.47 cmH2O above baseline (P < 0.05, n = 5) (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

A: representative airway pressure tracing in a guinea pig of vagal nerve stimulation (VNS)-induced increases in Ppi. After 3 consistent increases in Ppi by electrical VNS, muscimol (18.7 μg/kg iv) pretreatment 1 min before a subsequent VNS attenuated the vagal nerve stimulus-induced increase in Ppi. B: transient increases in Ppi following VNS in guinea pig airways in vivo before and after intravenous muscimol (18.7 μg/kg). Muscimol (18.7 μg/kg) significantly attenuated VNS-induced increases in Ppi. Values are means ± SE (n = 5). *P < 0.05 compared with no muscimol (VNS alone). #P < 0.001 compared with baseline.

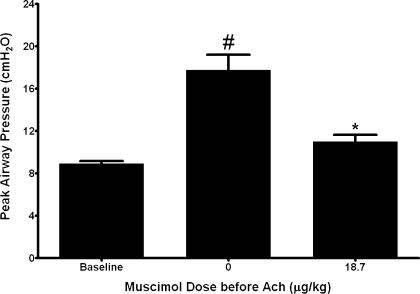

GABAA agonist pretreatment reduces intravenous acetylcholine-induced increases in Ppi after ligation of vagus nerve, postsynaptic sympathetic nerve neurotransmitter depletion with guanethidine, and NANC nerve neurotransmitter depletion with capsaicin.

In this series of studies the average baseline Ppi was 8.92 ± 0.27 cmH2O. Acetylcholine alone (8–24 μg/kg iv) caused a transient and consistent increase of 8.85 ± 1.52 cmH2O in Ppi above baseline. After ligation of the vagus nerves and guanethidine and capsaicin depletion of sympathetic and NANC nerve neurotransmitter, respectively, pretreatment with muscimol (18.7 μg/kg) again decreased the response to an acetylcholine challenge to only 2.10 ± 0.85 cmH2O above baseline, an ∼75% reduction in response (P < 0.001, n = 6) (Fig. 4). No animal responded to tyramine (10 mg/kg iv) with an increase in blood pressure after completing the acetylcholine and muscimol challenges, confirming that guanethidine depletion of sympathetic nerve neurotransmitters persisted throughout the experiments. Tyramine (10 mg/kg iv) in control animals did cause an appreciable increase in blood pressure in the absence of guanethidine (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Transient increases in Ppi following ACh in guinea pig airways in vivo before and after intravenous muscimol (18.7 μg/kg) in animals with ligated vagal nerves pretreated with capsaicin (20 μg/kg iv, 2 doses) and guanethidine (10 mg/kg iv). Muscimol (18.7 μg/kg) significantly attenuated ACh-induced increases in peak Ppi after vagal nerve ligation and nonadrenergic, noncholinergic and sympathetic nerve neurotransmitter depletion by capsaicin and guanethidine, respectively. Values are means ± SE (n = 6). *P < 0.001 compared with no muscimol (ACh alone). #P < 0.001 compared with baseline.

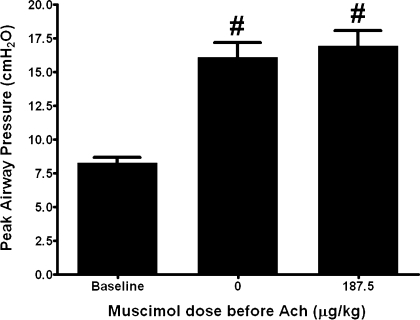

GABAA agonist pretreatment effect on intravenous acetylcholine-induced increases in Ppi after pretreatment with the GABAA antagonist gabazine.

In this series of experiments the average baseline Ppi was 8.28 ± 0.42 cmH2O. Acetylcholine alone (8–24 μg/kg iv) caused a transient and consistent increase in Ppi of 7.83 ± 0.67 cmH2O above baseline. Pretreatment with gabazine (3.75 mg/kg), a selective GABAA antagonist, before muscimol (187.5 μg/kg) and acetylcholine eliminated the attenuation by muscimol with an average acetylcholine-induced increase in airway pressure of 8.02 ± 0.68 cmH2O (P = 0.8392, n = 5) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Transient increases in Ppi following ACh in guinea pig airways in vivo before and after intravenous muscimol (187.5 μg/kg) in animals pretreated with gabazine, a selective GABAA antagonist (3.75 mg/kg iv). Gabazine pretreatment eliminated the ability of muscimol to attenuate ACh-induced increases in peak Ppi. Values are means ± SE (n = 6). #P < 0.001 compared with baseline.

DISCUSSION

The major findings of this study are that intravenous pretreatment with muscimol, a selective GABAA agonist, attenuated increases in peak Ppi in vivo in guinea pigs in response to intravenous acetylcholine, intravenous histamine, and direct vagal nerve stimulation. In this well-characterized model of airway responsiveness, acetylcholine is thought to act directly on airway smooth muscle M3 muscarinic receptors to induce constriction modeling reflex bronchoconstriction to increase peak airway pressure (5, 10). The ability of muscimol to block a direct stimulation by exogenous acetylcholine acting directly on airway smooth muscle suggests direct action of muscimol at endogenous GABAA channels on airway smooth muscle to decrease the ability of acetylcholine to induce contraction at each dose of muscimol tested.

In these experiments, intravenous muscimol did not have a detectable effect on baseline airway pressure but attenuated acetylcholine-induced airway contraction. This is consistent with the known function of GABAA channels in the central nervous system to hyperpolarize neurons, since hyperpolarization of airway smooth muscle cells is a known component of β-adrenergic receptor-mediated relaxation (11). Dose-response studies of muscimol against acetylcholine-induced increases in Ppi were performed. Individual animals demonstrated a dose response, but the dose response was shifted left or right depending on the dose of acetylcholine required in an individual animal to achieve an ∼50% increase in baseline Ppi. Thus, since the dose of acetylcholine varied, the dose of muscimol varied between animals such that the combined data shown in Fig. 1B do not convey the dose-response relationship.

In further experiments, to determine whether muscimol's attenuation of stimulated increases in airway pressure was due to GABAA channels on airway smooth muscle or possible inhibition of tonic parasympathetic tone or activation of sympathetic nerve activity or release of NANC mediators, animals underwent vagal nerve ligation and pretreatment with guanethidine and capsaicin to eliminate contributions from parasympathetic, sympathetic, and NANC nerves, respectively. Capsaicin acts to depolarize airway NANC nerves via Ca2+ channel activation that causes the nerve to release its products, and the capsaicin stimulus maintains the nerve in a depolarized state, desensitizing the nerve to a subsequent depolarizing stimulus (8, 9). Guanethidine acts by activating release of catecholamines and then blocking catecholamine reuptake from postganglionic sympathetic nerves. After depletion of these sources of possible airway neural relaxing mediators, muscimol maintained significant attenuation of increases in airway pressure induced by exogenous acetylcholine, further suggesting a direct effect at GABAA channels on airway smooth muscle.

Reflex-induced bronchoconstriction that occurs clinically following irritation of the upper trachea is in part mediated by vagus nerve reflexes. Vagal nerve postganglionic parasympathetic nerves mediate this airway constriction via acetylcholine release acting on airway smooth muscle M3 muscarinic receptors. Although vagal nerve stimulation in this model is thought to predominantly release acetylcholine, altering the characteristics of the electrical stimulus applied to the vagal nerve can result in the release of nonadrenergic, noncholinergic airway constrictors (1). In these experiments, muscimol attenuated vagal nerve-stimulated increases in airway pressure, which is a stimulus that more clearly models the clinical circumstances of reflex-induced bronchoconstriction. Muscimol attenuation of vagal nerve-stimulated increases in airway pressure is consistent with the results obtained with exogenous intravenous acetylcholine.

To confirm that muscimol was acting to attenuate induced increases in Ppi via action at a GABAA channel, we pretreated guinea pigs with gabazine, a selective GABAA antagonist. Gabazine was chosen as a selective GABAA antagonist given its ability to competitively and selectively inhibit the GABAA channel, its superior water solubility, and its proven use in in vivo studies with minimal side effects (i.e., seizures) (15). Therefore, in the present study, animals were pretreated with gabazine to determine whether it would block muscimol's effect. After pretreatment with gabazine, muscimol's attenuation of acetylcholine-induced increases in Ppi was lost, indicating a selective effect of muscimol at GABAA channels. This is the first known demonstration of a specific GABAA agonist attenuating induced increases in airway pressure in vivo.

The model used in the present study measures Ppi, which is not a direct measurement of airway resistance, but rather a combination of airway resistance and dynamic compliance. This model does not allow for separation of concurrent increases in airway resistance and dynamic compliance, and it is likely that changes in airway resistance are partly caused by changes in dynamic compliance. It is possible that changes in compliance over the course of the experiment could contribute to changes in measured Ppi. However, if changes in airway compliance were significant, we would expect to see a change in the baseline Ppi or the end-expiratory airway pressures over the course of the experiments. As shown in representative Figs. 1A, 2A, and 3A, these baseline pressures did not vary over the course of the measurements, suggesting that changes in airway compliance did not have a significant impact on our induced changes in airway pressures.

In an initial investigation for a role for airway GABA receptors in the control of airway tone, Tamaoki et al. (16) relaxed electrical field stimulation (EFS)-induced contraction of isolated tracheal rings with GABA, baclofen, and muscimol in vitro. The attenuation of EFS-induced tracheal ring contraction by GABA and baclofen was antagonized by bicuculline, a specific GABAA antagonist. There was no attenuation by GABA or baclofen of a contraction by exogenous acetylcholine, which is believed to act as a direct agonist at airway smooth muscle. The relaxant effect of GABA was not affected by the removal of airway epithelium. The group concluded that an attenuation of EFS and lack of attenuation of exogenous acetylcholine indicated that this GABAA effect was on the prejunctional parasympathetic nerve. However, the group did not attempt to give a specific GABAA agonist in vivo, but instead used GABA, which, in addition to its action on GABAA channels, could be acting on postjunctional GABAB receptors to induce contraction (13). Our studies differ by demonstrating relaxation of both vagal nerve stimulation and exogenous acetylcholine-induced increases in airway pressure by a selective GABAA agonist in vivo. The attenuation of exogenously administered acetylcholine- and histamine-induced increases in airway pressure suggests that muscimol, a specific GABAA agonist, is acting on recently described GABAA receptors on airway smooth muscle (12). This argument is further supported by the continued attenuation by muscimol of acetylcholine-induced increases in Ppi after ligation of parasympathetic nerves and depletion of postganglionic sympathetic and NANC contributions, making neurally mediated attenuation unlikely.

Chapman et al. (3) studied the effects of GABA, GABAA, and GABAB agonists on vagal nerve stimulation-induced increases in peak airway inflation pressures in vivo. The vagal nerve-induced increases in airway pressure following a 5-V, 20-Hz, 0.5-ms pulse width, 5-s duration stimulus was completely blocked by atropine, suggesting the vagal nerve stimulation-induced airway pressure increase was mediated by acetylcholine, whereas a 10-V, 20-Hz, 0.5-ms pulse width, 5-s duration stimulus was not blocked by atropine, suggesting other, presumably NANC, mediators were being released by vagal nerve stimulation. The study by Chapman et al. did show an attenuation of vagal nerve-stimulated increases in airway pressure with GABA and baclofen, but not with muscimol. The attenuation of increases in airway pressures by GABA was not affected by bicuculline, a GABAA antagonist. Neither GABA nor baclofen decreased a methacholine-induced contraction, suggesting a prejunctional nerve GABAB rather than a direct smooth muscle effect of GABA, and baclofen. The current study demonstrates a significant decrease in vagal nerve-induced increases in airway pressure at a similar range of stimulation (10–20 V, 10–20 Hz, 0.2-ms pulse width, and 7-s duration) by intravenous muscimol. One possible explanation for the attenuation of the vagal nerve stimulus by muscimol in the current study is that muscimol was given 1 min before vagal nerve stimulation, rather than 10 min before as in the study by Chapman et al (3). In our preliminary studies, acetylcholine given again 5 min after muscimol (data not shown) was not attenuated, suggesting that an intravenous dose of muscimol has a short duration of action against acetylcholine-induced increases in airway pressure and may account for the lack of effect in the study by Chapman et. al. Another significant difference between the current study and the work by Chapman et al. is that we conducted multiple vagal nerve contractions to find an optimal stimulus for each animal and then repeated the vagal nerve stimulation three times to show a consistent stimulus before attempting to attenuate the vagal nerve contraction with muscimol. Since Chapman et al. conducted only a single contraction as control and a single contraction 10 min after drug or vehicle administration, they may have been giving a muscimol challenge at a point of either an increasing or decreasing response to vagal nerve stimulation.

A recent study by Xiang et al. (17) described GABAA receptors on airway epithelial cells that mediate airway mucus production but failed to identify GABAA channels on airway smooth muscle (17). The immunohistochemistry data presented failed to show the β2β3 GABAA channel subunit in what appears to be peripheral mouse lung tissue. In contrast, our laboratory recently demonstrated multiple GABAA subunits, including the β3-subunit, in human and guinea pig airway smooth muscle by RT-PCR, immunoblotting, and immunohistochemistry that were coupled to airway relaxation in vitro. It is possible that GABAA channel airway smooth muscle expression varies by species or, more likely, by location within the bronchopulmonary tree. A study of the distal mouse airways in contrast to the more proximal human or guinea pig airway may account for these differences.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that muscimol, a selective GABAA agonist, attenuates increases in pulmonary inflation pressure induced by exogenous intravenous acetylcholine, intravenous histamine, or vagal nerve stimulation in guinea pigs in vivo. Attenuation of exogenous acetylcholine-induced increases in airway pressure by muscimol is preserved after ligation of parasympathetic nerves, depletion of postganglionic sympathetic nerves, and depletion of NANC nerves, suggesting a direct effect at recently described airway smooth muscle GABAA channels. Muscimol's attenuation of acetylcholine-induced increase in airway pressure is ablated by the selective GABAA antagonist gabazine, confirming muscimol's selectivity at GABAA channels. This is the first demonstration of attenuation of stimulated increases in pulmonary inflation pressures by a GABAA agonist in guinea pigs in vivo and suggests a novel therapeutic approach to reactive airway disease.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants GM065281 and ULI RR 024156.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of the Department of Anesthesiology, Columbia University.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Belvisi MG, Ichinose M, Barnes PJ. Modulation of non-adrenergic, non-cholinergic neural bronchoconstriction in guinea-pig airways via GABAB-receptors. Br J Pharmacol 97: 1225–1231, 1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bieda MC, MacIver MB. Major role for tonic GABAA conductances in anesthetic suppression of intrinsic neuronal excitability. J Neurophysiol 92: 1658–1667, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chapman RW, Danko G, Rizzo C, Egan RW, Mauser PJ, Kreutner W. Prejunctional GABA-B inhibition of cholinergic, neurally-mediated airway contractions in guinea-pigs. Pulm Pharmacol 4: 218–224, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eder W, Ege MJ, von ME. The asthma epidemic. N Engl J Med 355: 2226–2235, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faulkner D, Fryer AD, Maclagan J. Postganglionic muscarinic inhibitory receptors in pulmonary parasympathetic nerves in the guinea-pig. Br J Pharmacol 88: 181–187, 1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gallos G, Gleason NR, Zhang Y, Pak SW, Sonett JR, Yang J, Emala CW. Activation of endogenous GABAA channels on airway smooth muscle potentiates isoproterenol-mediated relaxation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 295: L1040–L1047, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenberg R, Antonaccio MJ, Steinbacher T. Thromboxane A2 mediated bronchoconstriction in the anesthetized guinea pig. Eur J Pharmacol 80: 19–27, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holzer P Local effector functions of capsaicin-sensitive sensory nerve endings: involvement of tachykinins, calcitonin gene-related peptide and other neuropeptides. Neuroscience 24: 739–768, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jia Y, Wang X, Aponte SI, Rivelli MA, Yang R, Rizzo CA, Corboz MR, Priestley T, Hey JA. Nociceptin/orphanin FQ inhibits capsaicin-induced guinea-pig airway contraction through an inward-rectifier potassium channel. Br J Pharmacol 135: 764–770, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jooste E, Zhang Y, Emala CW. Neuromuscular blocking agents’ differential bronchoconstrictive potential in Guinea pig airways. Anesthesiology 106: 763–772, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kotlikoff MI, Kamm KE. Molecular mechanisms of beta-adrenergic relaxation of airway smooth muscle. Annu Rev Physiol 58: 115–141, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mizuta K, Xu D, Pan Y, Comas G, Sonett JR, Zhang Y, Panettieri RA Jr, Yang J, Emala CW Sr. GABAA receptors are expressed and facilitate relaxation in airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 294: L1206–L1216, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osawa Y, Xu D, Sternberg D, Sonett JR, D'Armiento J, Panettieri RA, Emala CW. Functional expression of the GABAB receptor in human airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 291: L923–L931, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schultheis AH, Bassett DJ, Fryer AD. Ozone-induced airway hyperresponsiveness and loss of neuronal M2 muscarinic receptor function. J Appl Physiol 76: 1088–1097, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sonner JM, Zhang Y, Stabernack C, Abaigar W, Xing Y, Laster MJ. GABAA receptor blockade antagonizes the immobilizing action of propofol but not ketamine or isoflurane in a dose-related manner. Anesth Analg 96: 706–712, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tamaoki J, Graf PD, Nadel JA. Effect of gamma-aminobutyric acid on neurally mediated contraction of guinea pig trachealis smooth muscle. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 243: 86–90, 1987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiang YY, Wang S, Liu M, Hirota JA, Li J, Ju W, Fan Y, Kelly MM, Ye B, Orser B, O'Byrne PM, Inman MD, Yang X, Lu WY. A GABAergic system in airway epithelium is essential for mucus overproduction in asthma. Nat Med 13: 862–867, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]