Abstract

Lymphocytes help determine whether gut epithelial cells proliferate or differentiate but are not known to affect whether they live or die. Here, we report that lymphocytes play a controlling role in mediating gut epithelial apoptosis in sepsis but not under basal conditions. Gut epithelial apoptosis is similar in unmanipulated Rag-1−/− and wild-type (WT) mice. However, Rag-1−/− animals have a 5-fold augmentation in gut epithelial apoptosis following cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) compared to septic WT mice. Reconstitution of lymphocytes in Rag-1−/− mice via adoptive transfer decreases intestinal apoptosis to levels seen in WT animals. Subset analysis indicates that CD4+ but not CD8+, γδ, or B cells are responsible for the antiapoptotic effect of lymphocytes on the gut epithelium. Gut-specific overexpression of Bcl-2 in transgenic mice decreases mortality following CLP. This survival benefit is lymphocyte dependent since gut-specific overexpression of Bcl-2 fails to alter survival when the transgene is overexpressed in Rag-1−/− mice. Further, adoptively transferring lymphocytes to Rag-1−/− mice that simultaneously overexpress gut-specific Bcl-2 results in improved mortality following sepsis. Thus, sepsis unmasks CD4+ lymphocyte control of gut apoptosis that is not present under homeostatic conditions, which acts as a key determinant of both cellular survival and host mortality.—Stromberg, P. E., Woolsey, C. A., Clark, A. T., Clark, J. A., Turnbull, I. R., McConnell, K. W., Chang, K. C., Chung, C.-S., Ayala, A., Buchman, T. G., Hotchkiss, R. S., Coopersmith, C. M. CD4+ lymphocytes control gut epithelial apoptosis and mediate survival in sepsis.

Keywords: crosstalk, intestine, Bcl-2, cell death, cecal ligation and puncture

Crosstalk regularly occurs between the gut epithelium and lymphocytes under homeostatic conditions (1, 2). Intestinal lymphocytes play an essential role in controlling whether gut epithelial cells proliferate or differentiate (3), as well as maintaining gut integrity through the localized production of growth factors (2). Gut epithelial cells affect the immune system by acting as a barrier against antigens from the external environment and the internal commensal bacteria, thereby preventing activation of mucosal lymphocytes (1). They also express HLA class II antigens and function as antigen-presenting cells to CD4+ lymphocytes (4, 5). Imbalances in this homeostatic conversation have been proposed as a potential mechanism for the development of inflammatory bowel disease (1, 6,7,8).

Although extensive data exist on crosstalk between the gut epithelium and lymphocytes under basal conditions and in chronic disease, this relation has not been studied to the same degree in acute illness, in which the inflammatory milieu is markedly different. This may be particularly relevant in sepsis, a disease that kills 215,000 people annually in the United States (9), where the gut has been described as the “motor” that perpetuates inflammation, leading to multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (10,11,12).

Whereas autopsy studies of patients who die of sepsis in intensive care units are notable for an absence of generalized histological abnormalities, there is up-regulated gut epithelial apoptosis compared to patients who die without sepsis (13). Similar findings exist in animal studies, in which gut epithelial apoptosis is increased in cecal ligation and puncture (CLP), an animal model of ruptured appendicitis, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia (14,15,16). Notably, preventing sepsis-induced increases in gut epithelial apoptosis by intestine-specific overexpression of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 improves survival 2- to 10-fold in CLP and pneumonia, although the mechanisms underlying this survival advantage are poorly understood (17, 18).

This study evaluated the influence of lymphocytes on sepsis-induced gut epithelial apoptosis in light of 1) known crosstalk between the gut epithelium and lymphocytes, 2) the survival advantage conferred by preventing gut epithelial apoptosis in sepsis, and 3) the fact that lymphocytes play a central role in the pathophysiology of sepsis, as evidenced by the fact that Rag-1−/− mice have elevated mortality following CLP (19). We demonstrate herein that lymphocytes have no effect on gut epithelial apoptosis under basal conditions but have a profound antiapoptotic role in the intestinal epithelium in septic mice. Further, the mortality benefit conferred by gut overexpression of Bcl-2 following CLP is dependent on the presence of an intact adaptive immune system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Six- to 10-wk-old male C57BL/6 WT, Rag-1−/−, CD4−/−, CD8−/−, γδ−/−, and B-cell−/− mice were purchased commercially (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Fabpl-Bcl-2 mice on an FVB/N background were derived in our laboratory (20). Fabpl-Bcl-2 mice were crossed to Rag-1−/−mice for two generations to create Bcl-2+/Rag-1−/−, Bcl-2+/Rag-1+/−, Bcl-2−/Rag-1−/−, and Bcl-2−/Rag-1+/− animals. Bcl-2 transgene was identified via PCR. The presence or absence of lymphocytes was determined using flow cytometry. After 70 μl of blood was taken from the tail vein, red blood cells were lysed, and polymorphonuclear leukocytes were resuspended, incubated with anti-mouse CD16/32 (Fc block), and stained with PEcy5-CD3 and FITC-CD45 (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) to identify T lymphocytes. Animal studies were approved by the Washington University Animal Studies Committee and conducted in accordance with the U.S. National Institutes of Health guidelines for the use of laboratory animals.

Sepsis model

CLP was performed by the method of Baker et al. (21). Animals were anesthetized with halothane, and a midline incision was made. The cecum was removed, ligated with 4-0 silk below the ileocecal valve, and subjected to a double puncture with a 23-gauge needle. The cecum was then gently squeezed to extrude a small amount of stool and replaced into the peritoneal cavity. The abdomen was closed in layers, and mice then received a 1.0-ml subcutaneous injection of 0.9% NaCl.

Immunohistochemistry

Apoptosis was quantified by functional analysis using active caspase-3 staining and by morphological analysis using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining in 100 contiguous crypts/section by an observer masked to section identity. Used in conjunction, this combination of identifying apoptosis via functional and morphological techniques has been demonstrated to be an accurate assessment of gut epithelial apoptosis following diverse injuries (16). Trends regarding apoptosis levels were similar for both active caspase 3 and H&E staining in all groups examined. For active caspase 3 staining, sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and incubated in 3% H2O2 for 15 min to block endogenous peroxidase activity. Sections were blocked with serum-free protein block (Dako Corporation, Carpinteria, CA, USA) for 10 min, and antigen retrieval was facilitated by incubating sections in antigen decloaker solution (Biocare Medical, Concord, CA, USA) for 45 min at 100°C. Sections were washed in PBS and incubated overnight at 4°C with polyclonal rabbit anti-active caspase 3 (1:100; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA). Sections were then washed in PBS, incubated for 1 h at 25°C with biotinylated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (1:200; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) followed by Vectastain ABC-AP (Vector Laboratories), developed with Sigma Fast DAB (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 5 min, and counterstained with hematoxylin. Morphological analysis on H&E-stained sections was performed by identifying apoptotic cells via the presence of compacted and condensed nuclei and/or nuclear fragmentation.

Staining and development for CD3 to determine where adoptively transferred lymphocytes homed was similar to that for active caspase 3 except following antigen retrieval. Sections were blocked in 20% goat serum (Vector Laboratories) for 30 min at 25°C, and this was followed by incubation with rabbit anti-human T cell CD3 peptide (1:100; this has mouse cross-reactivity, Sigma) overnight at 25°C.

Adoptive transfer of splenocytes or CD4+ lymphocytes

Donor spleens were harvested from unmanipulated C57BL/6 mice and disassociated using a cell strainer and a sterile plunger from a 5-ml syringe (22). After washing with PBS, red blood cells were lysed using a buffered ammonium chloride lysis solution and washed in PBS 2 additional times. Samples were then centrifuged at 754 g for 10 min, and resuspended splenocytes were layered onto Histopaque 1083 (Sigma) to remove dead cells. After 3 more cycles of rinsing and centrifugation, cells were pooled and counted using a hemocytometer. Alternatively, CD4+ cells were isolated using a commercially available isolation system (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, splenocytes were suspended in a solution of anti-mouse CD4 magnetic particles. The resuspended cells were incubated on a magnet, and the supernatant containing the negative fraction was aspirated and discarded. The remaining cells underwent 2 more cycles of resuspension and incubation. After the final wash, the positive fraction was resuspended in PBS and counted on a hemocytometer. Purity was verified using flow cytometry. Under halothane anesthesia, recipient mice received a retroorbital injection of either 5 × 107 splenocytes in a volume of 500 μl or 5 × 106CD4+-enriched lymphocytes in a volume of 300 μl. Artificial tears were applied to the appropriate eye of the recipient animal.

CD4+/CD25+ depletion

Splenocytes were isolated and pooled as described above from C57BL/6 mice. CD4+/CD25+ cells were depleted using a commercially available isolation system (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA). The cells to be depleted were incubated with a biotin-antibody cocktail for labeling of non-CD4+ T cells and antibiotin microbeads. The suspension was passed through a magnetic column to isolate CD4+ T cells by negative selection. Isolated CD4+ T cells were depleted of their CD25+ subset by labeling with CD25-PE and incubation with anti-PE microbeads. After passing through a second magnetic column, CD4+/CD25− cells were obtained. This subset of cells was then added to a population of splenocytes containing all cells except CD4+ cells, resulting in a population of splenocytes that was specifically depleted of CD4+/CD25+ cells. Depletion was verified using flow cytometry. Cells were incubated with FITC-conjugated anti-CD4 antibody (1:1000; BD Biosciences) and PE-conjugated anti-CD25 antibody (1:1000; BD Biosciences) and phenotyping was performed using a FACScan machine (BD Biosciences). CD4+/CD25+-depleted lymphocytes and control splenocytes were then adoptively transferred to different cohorts of Rag-1−/− mice as above.

Western blot analysis

The small intestine was harvested, flushed of luminal contents with cold PBS, and opened lengthwise. Epithelial scrapings were obtained using coated glass slides, weighed immediately, and placed in cell lysis buffer with an array of protease inhibitors (23). Cells were sonicated and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C, and the resulting lysate was aliquotted and stored at −80°C. Quantification of protein was performed using the Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Fifty micrograms of protein was added to an equal volume of 2× Laemmli sample buffer, heat denatured, and run on an SDS-PAGE gel, (Bio-Rad) at 180 V for 45 min. Protein was transferred to previously equilibrated Immuno-Blot polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad) for 1 h at 100 V. Membranes were blocked for 1 h in 5% nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST; Sigma) and incubated overnight at 4°C using antibodies against Bax, Bcl-xL (1:500, Cell Signaling Technology), or β-actin (1:5000; Chemicon, Temecula, CA, USA). Membranes were then rinsed with TBST and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (1:2000; Cell Signaling Technology) for 1 h at 25°C and then rinsed again in TBST. Blots were developed using SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA), exposed to X-ray film and developed in a film processor.

Survival

Animals were subjected to 2 × 23 CLP. Antibiotic therapy was initiated 1 h post-CLP with 35 mg/kg of metronidazole and 50 mg/kg of ceftriaxone and continued every 12 h for 2 d. Animals were allowed free access to food and water and were followed 7 d for survival.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the statistical software program Prism 4.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) and are reported as means ± se. For experiments comparing noncontiguous variables in three or more groups, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey posttest was performed. When two groups were compared, Student’s t test was performed. Differences in group survival were determined using log-rank analysis. A value of P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Sepsis-induced gut epithelial apoptosis is augmented in the absence of lymphocytes

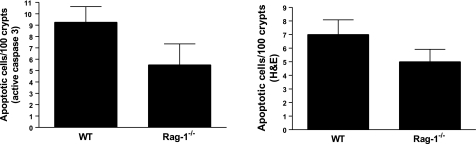

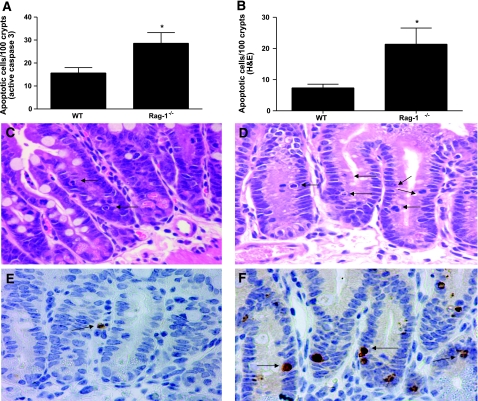

Intestines from unmanipulated WT C57BL/6 and Rag-1−/− mice were examined to determine whether lymphocytes mediate gut epithelial apoptosis under basal conditions. Apoptosis levels were similar in each group demonstrating that lymphocytes do not affect intestinal cell survival in unstressed animals (Fig. 1). WT and Rag-1−/− mice were then subjected to 2 × 23 CLP and sacrificed 24 h later. While WT mice had an increase in sepsis-induced gut epithelial apoptosis, septic Rag-1−/− mice had a further 2- to 5-fold augmentation in gut apoptosis compared to WT mice whether assayed by active caspase 3 or H&E staining (P<0.05 for both, Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Gut epithelial apoptosis is similar in unmanipulated Rag-1−/− mice and WT mice. Quantification of apoptotic cells by active caspase 3 (left panel) or H&E staining (right panel) in 100 contiguous crypts 24 h after CLP. Data represent means ± se of 5 animals/group.

Figure 2.

Sepsis-induced gut epithelial apoptosis is higher in Rag-1−/− mice than WT mice. A) Quantification of apoptotic cells by active caspase 3 in 100 contiguous crypts 24 h after CLP. Data represent means ± se of 8–9 animals. *P = 0.01. B) Quantification of apoptotic cells by H&E staining. Data represent means ± SE of 10–14 animals. *P = 0.0005. C–F) Histologic sections of representative intestines by H&E staining (C, D) or by active caspase 3 staining (E, F) demonstrate that apoptosis is detectable in septic WT mice (C, E) but is higher in septic Rag-1−/− mice (D, F). Arrows indicate apoptotic cells. View ×400.

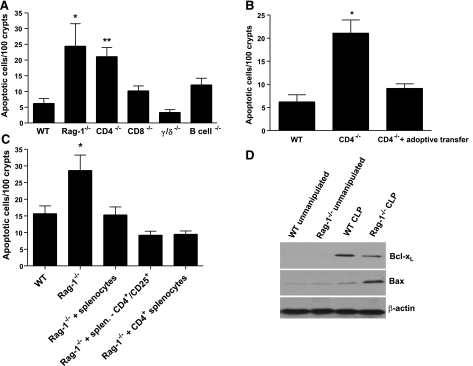

To determine which cellular subsets were responsible for the antiapoptotic role lymphocytes have in the gut epithelium, knockout animals lacking T-cell subsets (CD4−/−, CD8−/−, γδ−/−) or B cells were made septic. Gut epithelial apoptosis was augmented solely in septic CD4−/− mice with a 4-fold increase in the number of apoptotic cells compared to septic WT mice (Fig. 3A). To prove that the increase in sepsis-induced gut epithelial apoptosis in depleted animals was lymphocyte dependent, splenocytes from unmanipulated WT mice were adoptively transferred to CD4−/− mice. After 7 d, animals were subjected to CLP and then sacrificed 24 h later. There was a 5-fold up-regulation of sepsis-induced gut epithelial apoptosis in CD4−/− mice, and adoptively transferring splenocytes brought levels of intestinal epithelial cell death down to levels seen in septic WT mice (Fig. 3B). To further assess whether the antiapoptotic effect of lymphocytes on the gut epithelium was due to CD4+/CD25+ (T-regulatory) or CD4+/CD25− cells, Rag-1−/− mice were given either splenocytes from unmanipulated WT mice or splenocytes specifically depleted of CD4+/CD25+ via adoptive transfer and then subjected to CLP. Both decreased apoptosis to similar levels demonstrating that T-regulatory lymphocytes were not necessary to reverse the augmentation in sepsis-induced gut epithelial apoptosis seen in Rag-1−/− mice (Fig. 3C). Further, to demonstrate that CD4+ lymphocytes were sufficient to prevent sepsis-induced apoptotic augmentation in mice lacking lymphocytes, Rag-1−/− mice were given CD4+ lymphocytes via adoptive transfer and found to have similar levels of apoptosis as Rag-1−/− mice given splenocytes (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

CD4+ lymphocytes protect against gut epithelial apoptosis. A) CD4−/− but not CD8−/−, γδ−/−, or B-cell−/− mice have increased gut epithelial apoptosis 24 h after CLP. Data represent means ± se of 7–13 animals. *P < 0.001, **P < 0.01 vs. WT mice. B) Adoptive transfer of splenocytes to CD4−/− mice decreases gut epithelial apoptosis to levels seen in WT animals. Data represent means ± se of 10–14 animals. *P < 0.001 vs. WT mice. C) Adoptive transfer of splenocytes with or without CD4+CD25+ lymphocytes decreases gut epithelial apoptosis to levels seen in WT animals. Adoptive transfer of CD4+ lymphocytes also decreases gut epithelial apoptosis to levels seen in WT animals. Data represent means ± se of 8–10 animals. *P < 0.001 vs. WT mice. D) Western blot of Bax and Bcl-xL levels in intestinal epithelial cells in unmanipulated and septic Rag-1−/− and WT mice. Representative Western blot of n = 3 experiments is shown and is normalized to β-actin to demonstrate equal protein loading.

Lymphocytes prevent sepsis-induced gut epithelial apoptosis via the mitochondrial pathway

Intestinal epithelial cells were then harvested from unmanipulated and septic WT and Rag-1−/− mice and assayed for the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-xL and the proapoptotic Bax. Bcl-xL was undetectable in unmanipulated WT and Rag-1−/− mice, while Bax was present at similar low levels in each. Although there was an increase in Bcl-xL levels in WT septic mice, Bcl-xL levels were markedly lower in septic Rag-1−/− mice, consistent with a further augmentation of gut epithelial apoptosis in this cell type (Fig. 3D). Sepsis also induced a mild increase in Bax levels in the gut epithelium following CLP in WT mice, while Bax was further up-regulated in Rag-1−/− mice.

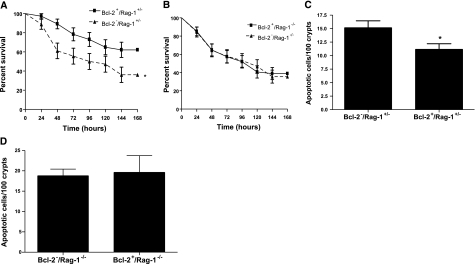

Survival benefit conferred by gut-specific overexpression of Bcl-2 is dependent on the presence of lymphocytes

We next examined whether the survival advantage conferred by gut Bcl-2 overexpression was dependent on the presence of lymphocytes. Rag-1−/− mice were crossed with Fabpl-Bcl-2 mice (that overexpress Bcl-2 in the gut epithelium; ref. 20) over two generations to create Bcl-2+/Rag-1−/− (gut epithelial Bcl-2 overexpression, no lymphocytes), Bcl-2+/Rag-1+/− (gut epithelial Bcl-2 overexpression), Bcl-2−/Rag-1−/− (no lymphocytes), and Bcl-2−/Rag-1+/− (WT) mice. In the presence of lymphocytes, overexpression of Bcl-2 in the gut epithelium decreased intestinal epithelial apoptosis and improved survival nearly 2-fold compared to WT animals following CLP (Fig. 4A, C). In contrast, survival was nearly identical in septic Rag-1−/− animals, regardless of whether they possessed the Bcl-2 transgene (Fig. 4B), demonstrating the survival advantage conferred by intestinal epithelial overexpression of Bcl-2 is dependent on the presence of lymphocytes. In addition, overexpression of Bcl-2 in the gut epithelium did not prevent sepsis-induced gut epithelial apoptosis in the absence of lymphocytes (Fig. 4D). To further prove the functional relation between gut epithelial apoptosis, lymphocytes, and mortality after sepsis, we compared survival in two additional cohorts of septic Bcl-2+/Rag-1−/− mice, one of which was given splenocytes via adoptive transfer 7 d prior to CLP (Fig. 5). Bcl-2+/Rag-1−/− mice that had reconstitution of lymphocytes by adoptive transfer had a survival advantage compared to Bcl-2+/Rag-1−/− mice. Of note, immunohistochemical staining for CD3 in Rag-1−/− mice that received adoptive transfer demonstrated that lymphocytes homed to the intestinal lamina propria 7 d following transfer (Fig. 6). In addition, there were no differences in intestinal permeability between septic mice regardless of whether they overexpressed Bcl-2 or had lymphocytes (data not shown).

Figure 4.

The survival advantage conferred by gut overexpression of Bcl-2 in sepsis is dependent on the presence of lymphocytes. A) Animals that overexpress Bcl-2 in their gut epithelium (Bcl-2+/Rag-1+/−) have increased survival 7 d following CLP compared to WT (Bcl-2−/Rag+/−) animals. Data represent n = 35–37 animals/group. *P = 0.02. B) Survival is similar in septic animals lacking lymphocytes, regardless of whether Bcl-2 is overexpressed in the gut epithelium. Data represent n = 45–54 animals/group. C) Gut overexpression of Bcl-2 prevents intestinal epithelial apoptosis in the presence of lymphocytes. Data represent means ± se of 6–11 animals. *P = 0.03. D) Gut overexpression of Bcl-2 does not prevent intestinal epithelial apoptosis in the absence of lymphocytes. Data represent means ± se of 5–8 animals.

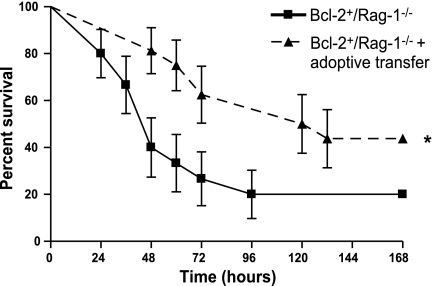

Figure 5.

Adoptive transfer of splenocytes restores the survival advantage conferred by gut epithelial overexpression of Bcl-2. Survival was compared 7 d after CLP between transgenic mice that simultaneously overexpress Bcl-2 in their gut epithelium but lack lymphocytes to genotypically identical animals that had adoptive transfer of lymphocytes prior to the onset of sepsis. Data represent 15–16 animals/group. *P = 0.03.

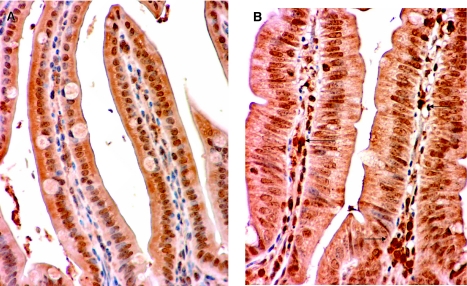

Figure 6.

Adoptively transferred splenocytes home to the lamina propria. Histologic sections of representative intestines stained for CD3. A) Rag-1−/− mice have no detectable staining for CD3. B) Rag-1−/− mice that received adoptive transfer of lymphocytes 7 d earlier stain positive for CD3 in the lamina propria (arrows). View ×400.

DISCUSSION

Our results uncover a previously unknown element of gut-immune crosstalk in which CD4+ lymphocytes control cellular fate in the intestinal epithelium in a relation unmasked only in conditions of acute stress. In addition, lymphocyte control of gut epithelial apoptosis appears to be a critical determinant of survival in intra-abdominal sepsis.

Although this is the first demonstration that CD4+ lymphocytes play a major role in controlling gut epithelial apoptosis in polymicrobial sepsis, significant evidence already exists that crosstalk occurs between the two cell types. Intestinal epithelial cells act as antigen-presenting cells to CD4+ lymphocytes in the intestinal mucosa via two pathways depending on the inflammatory state of the cell, with higher levels of antigen expression required for presentation in the absence of IFN-γ (24). Chronic inflammation leads to higher expression of HLA Class II antigens in intestinal epithelial cells than under basal conditions (25). Consistent with our results, these studies suggest that the gut epithelium actively senses its environment and responds differently when homeostatic mechanisms in the immune system are lost, and this response occurs in both directions with the gut epithelium and CD4+ lymphocytes exerting different effects on each other in conditions of stress than they do under basal conditions. This is similar to how the gut epithelium and the gut’s commensal bacteria coexist in equilibrium in the healthy state but interact in a fashion that may be detrimental to the host when sensing acute inflammatory perturbations seen in critical illness (26).

The differential response in Bax and Bcl-xL levels in unmanipulated and septic WT and Rag-1−/− mice suggest lymphocytes act on the gut epithelium via the mitochondrial pathway. As might be expected, Bax protein levels were consistent with quantity of apoptosis (low in unmanipulated animals, higher in WT septic animals, highest in Rag-1−/− septic animals). However, levels of Bcl-xL were unexpectedly higher in mice subjected to CLP than in unmanipulated animals despite the fact that gut epithelial apoptosis was higher in septic animals. This suggests that sepsis up-regulates multiple members of the mitochondrial pathway—both proapoptotic and antiapoptotic—and the ratio of apoptotic mediators determines cell fate. Supporting this notion, the decreased Bax/Bcl-xL ratio in WT septic vs. Rag-1−/− septic mice is consistent with previous reports demonstrating this ratio is associated with survival on a cellular level (27) and with decreased mortality in septic patients (28).

Our results offer a clearer understanding of how prevention of gut epithelial apoptosis improves survival in sepsis. Bacteria can initiate gut apoptosis by either directly interacting with intestinal epithelial cells (29) or indirectly by altering the immune response (e.g., by systemic increases in reactive oxygen species (30) or Fas ligand (31), which can, in turn, activate apoptosis). Regardless of how bacteria initiate intestinal cell death, prevention of gut epithelial apoptosis could theoretically improve survival by mechanisms directly related to the gut (altering permeability, cytokine production) or simply by altering the total burden of apoptosis in the host since apoptotic cells are immunosuppressive (32, 33) and adoptive transfer of apoptotic cells worsens survival in murine sepsis (22). However, we did not find a difference in permeability or cytokines between Rag-1−/− mice regardless of whether they overexpress Bcl-2 (data not shown). Instead, the finding that intestine-specific Bcl-2 overexpression fails to improve survival in the absence of lymphocytes appears directly linked to whether or not Bcl-2 can prevent sepsis-induced gut epithelial apoptosis. There are multiple reports in which Bcl-2 prevents apoptosis in vitro, but the addition or subtraction of other agents abrogates its antiapoptotic effect despite the molecule’s continued expression (34,35,36). However, we are aware of no in vivo correlate in which altering a different cell type prevents the ability of Bcl-2 to function in the tissue in which it is overexpressed. In contrast, the reverse has been described—Bcl-2 overexpression in myeloid cells prevents gut epithelial apoptosis following CLP despite the fact that Bcl-2 is not overexpressed in the gut, potentially through secretion of a molecule that has distant effects from the primary site of transgene expression (37).

The role of CD4+ lymphocytes on sepsis-induced mortality is not entirely clear. Two recent studies examining this issue have come to different conclusions, demonstrating that depletion of this cell type either has no effect (38) or is associated with increased mortality in CLP (39). However, the first study used a model with rapid 100% lethality, and neither examined the intestine, making them difficult to compare to our results. Of note, the finding that lymphocyte control of sepsis-induced gut epithelial apoptosis is independent of T-regulatory cells is consistent with studies demonstrating that depletion of these immunomodulatory cells does not affect mortality in polymicrobial sepsis (40, 41).

A possible limitation of our results is the fact that experiments involving Bcl-2 were performed on a mixed C57BL/6 and FVB/N background. Although all animals herein were littermates and a similar survival benefit was seen on Fabpl-Bcl-2 mice on a mixed background compared to those on a pure FVB/N background (Fig. 4A is similar to previous work published on these animals; ref. 17), genetic background has been demonstrated to play a critical role in the response to sepsis (42), so we cannot rule out that the results were affected by crossing animals from two strains. Another limitation to the manuscript is that while we showed that adoptive transfer of CD4+ lymphocytes was sufficient to prevent the augmentation of sepsis-induced gut epithelial apoptosis seen in Rag-1−/− mice, we cannot conclude from the survival experiments that CD4+ lymphocytes alone can confer a survival advantage in Bcl-2+/Rag-1−/− mice, since adoptive transfer experiments used splenocytes and not CD4+ lymphocytes.

Despite this limitation, this study describes a novel type of stress-induced gut epithelial-lymphocyte crosstalk that is not present under homeostatic conditions, and this interaction affects both cellular survival and host mortality. Additional work is needed to determine the factors through which lymphocytes control sepsis-induced gut epithelial apoptosis and host survival.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Washington University Digestive Diseases Research Morphology Core. This study was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (GM072808, GM66202, GM008795, GM055194, GM044118, DK052574).

References

- Dahan S, Roth-Walter F, Arnaboldi P, Agarwal S, Mayer L. Epithelia: lymphocyte interactions in the gut. Immunol Rev. 2007;215:243–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00484.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Chou K, Fuchs E, Havran W L, Boismenu R. Protection of the intestinal mucosa by intraepithelial gamma delta T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:14338–14343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212290499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerneis S, Bogdanova A, Kraehenbuhl J P, Pringault E. Conversion by Peyer’s patch lymphocytes of human enterocytes into M cells that transport bacteria. Science. 1997;277:949–952. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershberg R M, Cho D H, Youakim A, Bradley M B, Lee J S, Framson P E, Nepom G T. Highly polarized HLA class II antigen processing and presentation by human intestinal epithelial cells. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:792–803. doi: 10.1172/JCI3201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazawa A, Dotan I, Brimnes J, Allez M, Shao L, Tsushima F, Azuma M, Mayer L. The expression and function of costimulatory molecules B7H and B7–H1 on colonic epithelial cells. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1347–1357. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershberg R M, Mayer L F. Antigen processing and presentation by intestinal epithelial cells—polarity and complexity. Immunol Today. 2000;21:123–128. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(99)01575-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powrie F. T cells in inflammatory bowel disease: protective and pathogenic roles. Immunity. 1995;3:171–174. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90086-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caruso R, Fina D, Peluso I, Stolfi C, Fantini M C, Gioia V, Caprioli F, Del Vecchio B G, Paoluzi O A, Macdonald T T, Pallone F, Monteleone G. A functional role for interleukin-21 in promoting the synthesis of the T-cell chemoattractant, MIP-3α, by gut epithelial cells. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:166–175. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angus D C, Linde-Zwirble W T, Lidicker J, Clermont G, Carcillo J, Pinsky M R. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1303–1310. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassoun H T, Kone B C, Mercer D W, Moody F G, Weisbrodt N W, Moore F A. Post-injury multiple organ failure: the role of the gut. Shock. 2001;15:1–10. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200115010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alverdy J C, Laughlin R S, Wu L. Influence of the critically ill state on host-pathogen interactions within the intestine: gut-derived sepsis redefined. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:598–607. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000045576.55937.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark J A, Coopersmith C M. Intestinal crosstalk: a new paradigm for understanding the gut as the “motor” of critical illness. Shock. 2007;28:384–393. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e31805569df. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotchkiss R S, Swanson P E, Freeman B D, Tinsley K W, Cobb J P, Matuschak G M, Buchman T G, Karl I E. Apoptotic cell death in patients with sepsis, shock, and multiple organ dysfunction. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:1230–1251. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199907000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotchkiss R S, Swanson P E, Cobb J P, Jacobson A, Buchman T G, Karl I E. Apoptosis in lymphoid and parenchymal cells during sepsis: findings in normal and T- and B-cell-deficient mice. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:1298–1307. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199708000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coopersmith C M, Stromberg P E, Davis C G, Dunne W M, Amiot D M, Karl I E, Hotchkiss R S, Buchman T G. Sepsis from Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia decreases intestinal proliferation and induces gut epithelial cell cycle arrest. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1630–1637. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000055385.29232.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyas D, Robertson C M, Stromberg P E, Martin J R, Dunne W M, Houchen C W, Barrett T A, Ayala A, Perl M, Buchman T G, Coopersmith C M. Epithelial apoptosis in mechanistically distinct methods of injury in the murine small intestine. Histol Histopathol. 2007;22:623–630. doi: 10.14670/hh-22.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coopersmith C M, Chang K C, Swanson P E, Tinsley K W, Stromberg P E, Buchman T G, Karl I E, Hotchkiss R S. Overexpression of Bcl-2 in the intestinal epithelium improves survival in septic mice. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:195–201. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200201000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coopersmith C M, Stromberg P E, Dunne W M, Davis C G, Amiot D M, Buchman T G, Karl I E, Hotchkiss R S. Inhibition of intestinal epithelial apoptosis and survival in a murine model of pneumonia-induced sepsis. JAMA. 2002;287:1716–1721. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.13.1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotchkiss R S, Swanson P E, Knudson C M, Chang K C, Cobb J P, Osborne D F, Zollner K M, Buchman T G, Korsmeyer S J, Karl I E. Overexpression of Bcl-2 in transgenic mice decreases apoptosis and improves survival in sepsis. J Immunol. 1999;162:4148–4156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coopersmith C M, O'Donnell D, Gordon J I. Bcl-2 inhibits ischemia-reperfusion-induced apoptosis in the intestinal epithelium of transgenic mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Physiol. 1999;276:G677–G686. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.3.G677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker C C, Chaudry I H, Gaines H O, Baue A E. Evaluation of factors affecting mortality rate after sepsis in a murine cecal ligation and puncture model. Surgery. 1983;94:331–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotchkiss R S, Chang K C, Grayson M H, Tinsley K W, Dunne B S, Davis C G, Osborne D F, Karl I E. Adoptive transfer of apoptotic splenocytes worsens survival, whereas adoptive transfer of necrotic splenocytes improves survival in sepsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6724–6729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1031788100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern M D, Holubec H, Clark J A, Saunders T A, Williams C S, Dvorak K, Dvorak B. Epidermal growth factor reduces hepatic sequelae in experimental necrotizing enterocolitis. Biol Neonate. 2006;89:227–235. doi: 10.1159/000090015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershberg R M, Framson P E, Cho D H, Lee L Y, Kovats S, Beitz J, Blum J S, Nepom G T. Intestinal epithelial cells use two distinct pathways for HLA class II antigen processing. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:204–215. doi: 10.1172/JCI119514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer L, Eisenhardt D, Salomon P, Bauer W, Plous R, Piccinini L. Expression of class II molecules on intestinal epithelial cells in humans. Differences between normal and inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:3–12. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90575-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaborina O, Lepine F, Xiao G, Valuckaite V, Chen Y, Li T, Ciancio M, Zaborin A, Petroff E, Turner J R, Rahme L G, Chang E, Alverdy J C. Dynorphin activates quorum sensing quinolone signaling in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. [Online] PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e35. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George N M, Evans J J, Luo X. A three-helix homo-oligomerization domain containing BH3 and BH1 is responsible for the apoptotic activity of Bax. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1937–1948. doi: 10.1101/gad.1553607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilbault P, Lavaux T, Launoy A, Gaub M P, Meyer N, Oudet P, Pottecher T, Jaeger A, Schneider F. Influence of drotrecogin alpha (activated) infusion on the variation of Bax/Bcl-2 and Bax/Bcl-xl ratios in circulating mononuclear cells: a cohort study in septic shock patients. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:69–75. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000251133.26979.F4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J M, Eckmann L, Savidge T C, Lowe D C, Witthoft T, Kagnoff M F. Apoptosis of human intestinal epithelial cells after bacterial invasion. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1815–1823. doi: 10.1172/JCI2466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crimi E, Sica V, Slutsky A S, Zhang H, Williams-Ignarro S, Ignarro L J, Napoli C. Role of oxidative stress in experimental sepsis and multisystem organ dysfunction. Free Radic Res. 2006;40:665–672. doi: 10.1080/10715760600669612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Freitas I, Fernandez-Somoza M, Essenfeld-Sekler E, Cardier J E. Serum levels of the apoptosis-associated molecules, tumor necrosis factor-alpha/tumor necrosis factor type-I receptor and Fas/FasL, in sepsis. Chest. 2004;125:2238–2246. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.6.2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Frank M E, Jin W, Wahl S M. TGF-β released by apoptotic T cells contributes to an immunosuppressive milieu. Immunity. 2001;14:715–725. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00147-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voll R E, Herrmann M, Roth E A, Stach C, Kalden J R, Girkontaite I. Immunosuppressive effects of apoptotic cells. Nature. 1997;390:350–351. doi: 10.1038/37022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasmahapatra G, Almenara J A, Grant S. Flavopiridol and histone deacetylase inhibitors promote mitochondrial injury and cell death in human leukemia cells that overexpress Bcl-2. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:288–298. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.016154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang L, Boise L H, Dent P, Grant S. Potentiation of 1-beta-d-arabinofuranosylcytosine-mediated mitochondrial damage and apoptosis in human leukemia cells (U937) overexpressing Bcl-2 by the kinase inhibitor 7-hydroxystaurosporine (UCN-01) Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;60:1445–1456. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00463-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Freeman A, Liu J, Dai Q, Lee R M. The apoptotic effect of HA14–1, a Bcl-2-interacting small molecular compound, requires Bax translocation and is enhanced by PK11195. Mol Cancer Ther. 2002;1:961–967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata A, Stevenson V M, Minard A, Tasch M, Tupper J, Lagasse E, Weissman I, Harlan J M, Winn R K. Over-expression of Bcl-2 provides protection in septic mice by a trans effect. J Immunol. 2003;171:3136–3141. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.6.3136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enoh V T, Lin S H, Etogo A, Lin C Y, Sherwood E R. CD4+ T-cell depletion is not associated with alterations in survival, bacterial clearance, and inflammation after cecal ligation and puncture. Shock. 2008;29:56–64. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e318070c8b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martignoni A, Tschop J, Goetzman H S, Choi L G, Reid M D, Johannigman J A, Lentsch A B, Caldwell C C. CD4-expressing cells are early mediators of the innate immune system during sepsis. Shock. 2008;29:591–598. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318157f427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scumpia P O, Delano M J, Kelly K M, O'Malley K A, Efron P A, McAuliffe P F, Brusko T, Ungaro R, Barker T, Wynn J L, Atkinson M A, Reeves W H, Salzler M J, Moldawer L L. Increased natural CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells and their suppressor activity do not contribute to mortality in murine polymicrobial sepsis. J Immunol. 2006;177:7943–7949. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.7943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisnoski N, Chung C S, Chen Y, Huang X, Ayala A. The contribution of CD4+ CD25+ T-regulatory-cells to immune suppression in sepsis. Shock. 2007;27:251–257. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000239780.33398.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Maio A, Torres M B, Reeves R H. Genetic determinants influencing the response to injury, inflammation, and sepsis. Shock. 2005;23:11–17. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000144134.03598.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]