Abstract

Heat shock protein 90β (Hsp90β) is involved in many cellular functions. However, the posttranslational modification of Hsp90β, especially in response to apoptotic stimulation, is not well understood. In this study, we found that Hsp90β was cleaved by activated caspase-10 under UVB irradiation. Caspase-10 activation, in turn, depended on caspase-8, which cleaved caspase-10 directly. Autocrine secretion of FAS ligand and upregulated FAS expression induced by UVB irradiation contributed to activation of caspase-10, which cleaved Hsp90β at D278, P293, and D294. The downregulation of Hsp90β mediated by caspase-8-dependent caspase-10 activation promoted UVB-induced cell apoptosis.

Heat shock proteins (Hsps) are broadly classified into distinct subfamilies—Hsp100, Hsp90, Hsp70, Hsp60, Hsp40, small Hsps, and Hsp10—on the basis of their apparent molecular weights, amino acid sequences, and functions. Many members of these subfamilies are present constitutively in cells, whereas others are expressed only after stress (9). Hsps are involved in the normal folding of various polypeptides, assist misfolded proteins to attain or regain their native states, regulate protein stability and degradation, and promote protein translocation (9).

Hsp90 is one of the most abundant Hsps in eukaryotic cells, comprising 1% to 2% of cellular proteins under nonstress conditions (25). There are two major cytoplasmic isoforms of Hsp90 in vertebrates, inducible Hsp90α and constitutively expressed Hsp90β (7). Hsp90 is unique because it is not required for the biogenesis of most polypeptides. Instead, many but not all of its cellular substrates or client proteins are conformationally labile signal transducers, including protein kinases and transcription factors that have crucial roles in cell proliferation and differentiation, cell survival and apoptosis, and developmental processes (1, 19, 22, 28). Upon Hsp90 inhibition, client protein substrates are unable to properly fold into their biologically active conformations; therefore, they are destined for degradation via the ubiquitin-proteasomal pathway (3, 13). Because Hsp90 is involved in the modulation of tumor cell apoptosis and its inhibition disrupts multiple pathways essential to the survival, proliferation, and metastasis of transformed cells, Hsp90 has become a promising target for the development of cancer chemotherapeutics (28).

Apoptotic stimulation activates at least one of the two major apoptotic pathways, the intrinsic or mitochondrial death pathway and the extrinsic or receptor-mediated cell death pathway. Both of these pathways eventually activate effector caspases to execute cell death (4). The activation of the intrinsic pathway leads to the assembly of functional apoptosomes composed of mitochondrially released cytochrome c, apoptotic protease activating factor 1, and procaspase-9. The apoptosome complex proteolytically processes procaspase-9 to an active form that activates effector caspase-3 and -7 (4, 30). The extrinsic pathway transduces death signals through the binding of death ligands such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), FAS ligand/Apo1L/CD95L, Trail/Apo2L, and Apo3L to their respective cell surface receptors. A homotypic interaction occurs between the death domains of TNF receptor-1 (TNFR-1) and FAS receptors and their respective adaptor molecules, TNFR-1-associated death domain protein (TRADD) and Fas-associated death domain protein (FADD), that leads to the formation of the death-inducing signal complex (DISC), which activates procaspase-8 and, subsequently, caspase-3 and -7. The extrinsic death signals can be linked to the intrinsic pathway through the Bcl-2 family of proteins, which includes both proapoptotic (e.g., Bax, Bad, Bak, and Bid) and antiapoptotic (e.g., Bcl-XL) members (1, 8, 30).

Hsp90β is involved in many cellular functions via regulation of its client substrate proteins. However, most studies of Hsp90β regulation are conducted at transcriptional levels (7, 25); its posttranslational modification, especially in response to apoptotic stimulation, is not well understood. In this report, we found that Hsp90β was cleaved by activated caspase-10 under UVB irradiation. Caspase-10 activation, in turn, depended on UVB-induced secretion of FAS ligand and subsequent activation of caspase-8. The downregulation of Hsp90β promoted UVB-induced cell apoptosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, cell culture conditions, and UVB irradiation.

A431, 293T, Jurkat T, NIH 3T3, and caspase-8-deficient Jurkat T cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% bovine calf serum (HyClone, Logan, UT). Quiescent cell cultures were created by growing cells in medium containing 0.5% serum for 16 h and exposing them to 18 mJ of UVB.

Materials.

Caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK, caspase-8 inhibitor Z-IETD-FMK, caspase-9 inhibitor Z-LEHD-FMK, and caspase-10 inhibitor Z-AEVD-FMK were from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). Active recombinant caspase-1 to caspase-10 were from BioVision (Mountain View, CA). A monoclonal antibody for FAS and polyclonal antibodies for C-terminal Hsp90β (D-19), caspase-10 p10 (C-13), FAS ligand, c-FLIP, and actin were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Antibodies for caspase-10 were from MBL (Woburn, MA). Monoclonal antibodies for FLAG, poly-His, and tubulin were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Monoclonal and polyclonal anti-caspase-8 antibodies were from BD Biosciences Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). Fas-Fc fusion proteins were from Alexis Biochemicals (San Diego, CA).

DNA constructs and mutagenesis.

Human Hsp90β was subcloned from p2HG/hHsp90β into pCold I vector between NdeI and XbaI. His-Hsp90β mutants were created using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA).

pRETRO-SUPER(pRS) caspase-10-1 was generated with oligonucleotides 5′-GATCCCCGCATGCAGGTAGTAATGGTTTCAAGAGAACCATTACTACCTGCATGCTTTTTGGAAA-3′ (forward) and 5′-AGCTTTTCCAAAAAGCATGCAGGTAGTAATGGTTCTCTTGAAACCATTACTACCTGCATGCGGG-3′ (reverse). pRS caspase-10-2 was generated with oligonucleotides 5′-GATCCCCAGGACATGATCTTCCTTCTTTCAAGAGAAGAAGGAAGATCATGTCCTTTTTTGGAAA-3′ (forward) and 5′-AGCTTTTCCAAAAAAGGACATGATCTTCCTTCTTCTCTTGAAAGAAGGAAGATCATGTCCTGGG-3′ (reverse). The pRS control was generated with oligonucleotides 5′-GATCCCCAGATGGTGTCACACCAATATTCAAGAGATATTGGTGTGACACCATCTTTTTTGGAAA-3′ (forward) and 5′-AGCTTTTCCAAAAAAGATGGTGTCACACCAATATCTCTTGAATATTGGTGTGACACCATCTGGG-3′ (reverse).

pGIPZ Hsp90β-1 shRNA was generated with oligonucleotide 5′-GCTGTTGACAGTGAGCGAAAGAAGTGCCTTGAGCTCTTCTAGTGAAGCCACAGATG TAGGAAGAGCTCAAGGCACTTCTTTGCCTACTGCCTCGGA-3′. pGIPZ Hsp90β-1 was generated with oligonucleotide 5′-GCTGTTGACAGTGAGCGAAACCATTGCCAAGTCTGGTACTAGTGAAGCCACAGATGTAGTACCAGA CTTGGCAATGGTTGTGCCTACTGCCTCGGA-3′.

Transfection.

Cells were plated at a density of 4 × 105 per 60-mm-diameter dish 18 h prior to transfection. Transfection was performed using either calcium phosphate or HyFect reagents (Deveville Scientific) according to the vendor's instructions. Transfected cultures were selected with G418 (800 μg/ml) or hygromycin (200 μg/ml) for 10 to 14 days at 37°C. After treatment with G418 or hygromycin, antibiotic-resistant colonies were pooled and expanded for further analysis under selective conditions.

Purification of recombinant proteins.

Wild-type (WT) and mutant His-Hsp90β and His-histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3) proteins were expressed in bacteria and purified as described previously (16).

Immunofluorescence analysis.

Cells were fixed and incubated with the indicated antibodies and Hoechst 33342 according to standard protocols. Cells were examined using a laser-scanning Olympus microscope with a ×60 oil immersion objective. DeltaVision (Applied Precision Software) was used to deconvolve z-series images.

In vitro caspase cleavage assay.

In vitro caspase cleavage assays were conducted as described previously (29). In brief, anti-caspase-10 or anti-c-FLIP antibody was covalently cross-linked to immobilized protein A or protein G beaded agarose resin using the Seize X immunoprecipitation kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). The immunoprecipitated caspase-10 or c-FLIP from A431 cell lysate with the corresponding antibodies or 500 ng of purified WT His-Hsp90β protein was incubated with 1.5 U of caspases at 37°C for 4 h in a reaction solution (pH 7.2) containing 50 mM NaCl, 50 mM HEPES, 10 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol, and 0.1% CHAPS {3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio)-1-propanesulfonate}.

Preparation of proteins and trichloroacetic acid precipitation.

Cells growing in serum-free medium (3 ml/60-cm dish) were exposed to UVB. The medium was then collected and centrifuged at 1,200 × g to pellet and remove any cells and cell debris. Total protein in the supernatant was precipitated with trichloroacetic acid (final concentration, 15%). The samples were centrifuged at 12,000 × g, and the pellets were washed three times with ice-cold 80% acetone. The precipitated proteins were dried and resuspended in sample loading buffer for sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).

Cell apoptosis assay.

We plated 5 × 105 cells. The cells were left untreated or were treated with UVB, kept in quiescent medium for 24 h, and collected and processed for annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-propidium iodide (PI) staining. The cells were then washed with phosphate-buffered saline, and 105 cells (in 100 μl) were stained with 5 μl of annexin V-FITC and 5 μg/ml of PI in annexin binding buffer containing 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 140 mM NaCl, and 2.5 mM CaCl2 at ambient temperature. After 15 min, 400 μl of annexin binding buffer was added to the samples, which were immediately analyzed with a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton-Dickinson, San Jose, CA). The data represent the means ± standard deviations from three independent experiments.

Digestion and MS.

Protein bands were cut from Coomassie blue-stained SDS-PAGE gels, washed with water, and subsequently washed with 50% acetonitrile containing 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate two times. The bands were digested with 200 ng trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI) in 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate for 20 h. The peptides were extracted twice with 50% acetonitrile containing 0.01% trifluoroacetic acid and concentrated to less than 10 μl using a Speedvac (Thermo Savant, Holbrook, NY).

The resulting peptides were analyzed by Nano-liquid chromatography-coupled ion trap mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) with on-line desalting on a system consisting of a Famos autosampler, Ultimate Nano-LC module, and a Switchos precolumn switching device (LC-Packings/Dionex Corp., Sunnyvale, CA). Electrospray ion trap MS was performed on a linear ion-trap mass spectrometer (LTQ; Thermo-Finnigan, San Jose, CA). Proteins were identified by searching for the fragment spectra in the National Center for Biotechnology Information nonredundant protein database using Mascot (Matrix Science, London, United Kingdom) and Sequest (Thermo, San Jose, CA).

RESULTS

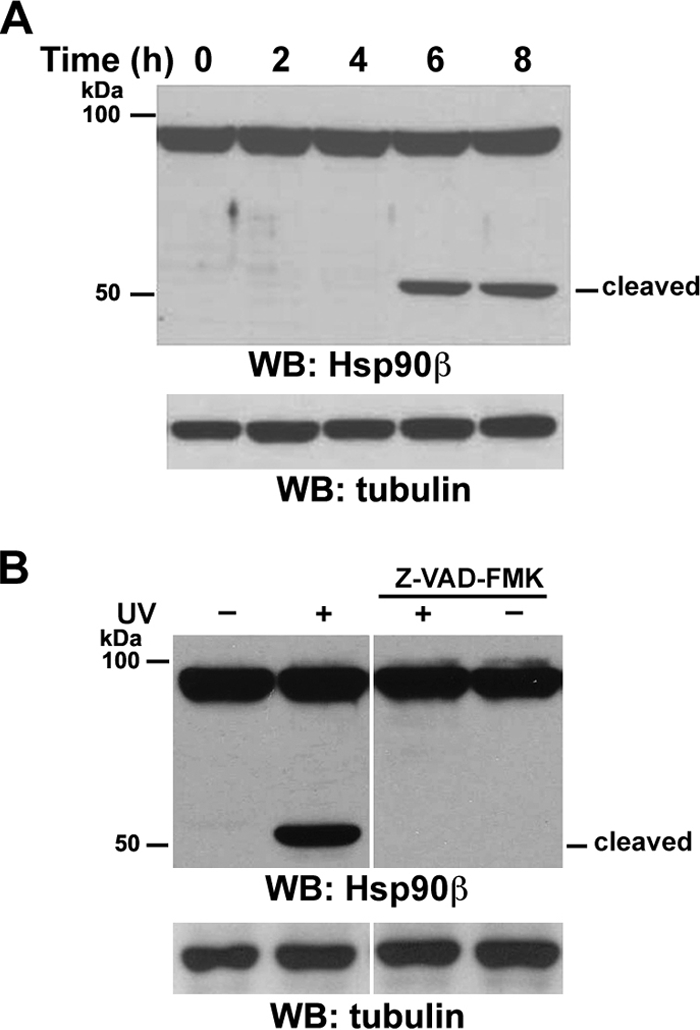

UVB irradiation induces caspase-dependent cleavage of Hsp90β.

To determine the effect of UVB irradiation on Hsp90β expression, we exposed A431 human epidermoid carcinoma cells to UVB irradiation before harvesting. An immunoblotting analysis showed that UVB irradiation created an approximately 55-kDa fragment (Fig. 1A) that was recognized by an antibody against the C terminus of Hsp90β, implying a cleavage close to its N terminus. Because this cleavage occurred within 6 h after UVB irradiation, a time point when little cell death was detected (data not shown), it was unlikely to be an effect of cell apoptosis (33).

FIG. 1.

UVB irradiation induces caspase-dependent cleavage of Hsp90β. Western immunoblotting (WB) analyses were carried out with the indicated antibodies. (A) Serum-starved A431 cells were exposed to UVB (18 mJ) irradiation, followed by incubation in 0.5% calf serum for the indicated time. (B) Serum-starved A431 cells were left untreated or were pretreated with caspase inhibitor Z-VAD (10 μM) for 30 min, followed by exposure to UVB (18 mJ) and incubation in 0.5% calf serum with or without Z-VAD for 8 h.

Because UVB irradiation activates caspases (33), the observed Hsp90β cleavage may have been mediated by caspases. To determine whether UVB-induced caspase activation was responsible for this cleavage, we pretreated A431 cells with the general caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK and then subjected them to UVB irradiation. As shown in Fig. 1B, caspase inhibition abrogated the UVB-induced truncation of Hsp90β. These results indicate that UVB irradiation induces caspase-dependent cleavage of Hsp90β.

Caspase-10 cleaves Hsp90β in vitro.

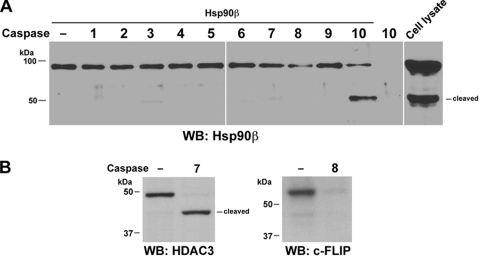

To determine which caspase was directly involved in Hsp90β cleavage, we conducted an in vitro caspase cleavage assay by mixing purified His-Hsp90β protein with purified active caspase-1 to -10. An immunoblotting analysis revealed that Hsp90β was cleaved by purified active caspase-10 but not by active caspase-1, -2, -3, -4, -5, -6, -7, -8, or -9 (Fig. 2A). In contrast, caspase-7 cleaved bacterially purified HDAC3 (Fig. 2B) and generated a fragment that was approximately 4 kDa smaller than its full-length WT protein; this finding is consistent with those of our previous study showing that HDAC3 is a substrate of caspase-7 (29). In addition, caspase-8 cleaved immunoprecipitated c-FLIP, a known substrate of caspase-8 (20). These results indicate that Hsp90β is a direct specific substrate of caspase-10 in vitro.

FIG. 2.

Caspase-10 cleaves Hsp90β in vitro. Bacterially purified Hsp90β (A) or HDAC3 (B) (left panel) or c-FLIP (right panel) immunoprecipitated from A431 cell lysate with an anti-c-FLIP antibody covalently cross-linked to immobilized protein A-agarose resin was incubated with the indicated recombinant caspases in reaction buffer at 37°C for 4 h. Western immunoblotting (WB) analyses were carried out with the indicated antibodies.

Both caspase-10 and -8 are required for UVB-induced Hsp90β cleavage in vivo.

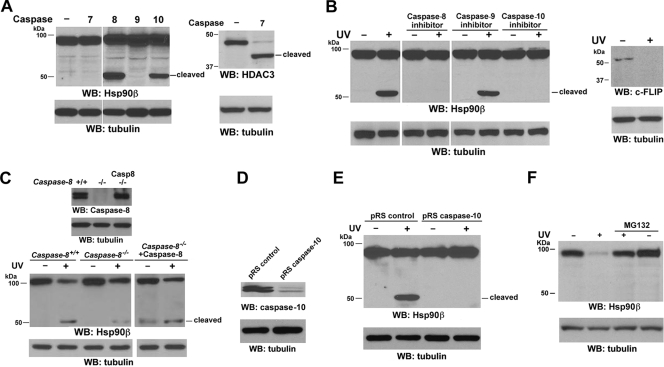

To determine whether caspase-10 is involved in UVB-induced Hsp90β cleavage, we transiently transfected caspase-7, -8, -9, or -10 into 293T human embryonic kidney cells (Fig. 3A, left panel). Consistent with the in vitro data demonstrating that caspase-10 directly cleaved Hsp90β, caspase-10 expression resulted in Hsp90β cleavage. Notably, expression of active caspase-8, but not caspase-7 or -9, also truncated Hsp90β to a similar size, as did caspase-10. In contrast, caspase-7 cleaved its substrate HDAC3 (Fig. 3A, right panel). Pretreatment with the caspase-8 inhibitor Z-IETD-FMK and caspase-10 inhibitor Z-AEVD-FMK, but not the caspase-9 inhibitor Z-LEHD-FMK, inhibited UVB-induced Hsp90β cleavage, indicating that the activation of caspase-8 and -10 is required for the effect of UVB on Hsp90β (Fig. 3B, left panel). As expected, c-FLIP was cleaved in response to UVB irradiation (Fig. 3B, right panel), indicating that UVB induced caspase-8 activation. In keeping with these results, caspase-8-deficient Jurkat T cells (11, 12), in contrast to their parental WT cells, were mostly resistant to UVB-induced Hsp90β cleavage (Fig. 3C). The reduced Hsp90β cleavage induced by caspase-8 deficiency was recuperated by reconstitutive expression of caspase-8 in caspase-8-deficient Jurkat cells. The incomplete block of Hsp90β cleavage implies the existence of a complementary effect of other caspases. Similarly, the depletion of caspase-10 in A431 cells by its short hairpin RNA (shRNA) (Fig. 3D) largely blocked UVB-induced Hsp90β cleavage (Fig. 3E). Given that the CASP-10 gene is absent from the murine genome (23), we treated NIH 3T3 mouse fibroblasts with UVB, which failed to cleave Hsp90β (Fig. 3F). These results indicate that caspase-10 has an essential role in Hsp90β cleavage in vivo in response to UVB irradiation. To examine whether the UVB-induced reduction of Hsp90β expression in murine cells results from other posttranslational modifications of Hsp90β, such as proteasome-mediated degradation, we pretreated NIH 3T3 cells with the proteasome inhibitor MG132. Inhibition of proteasome abrogated UVB-induced Hsp90β degradation (Fig. 3F), indicating that UVB induces Hsp90β downregulation by distinct mechanisms in different species.

FIG. 3.

Both caspase-10 and -8 are required for UVB-induced Hsp90β cleavage in vivo. Western immunoblotting (WB) analyses were carried out with the indicated antibodies. (A) 293T cells were transfected with a parental vector or the vector expressing the indicated caspases. (B) Serum-starved A431 cells were left untreated or treated with the indicated caspase inhibitors (10 μM each) for 30 min, followed by exposure to UVB (18 mJ) and incubation in 0.5% calf serum, with or without the indicated inhibitors, for 8 h. (C) Serum-starved Jurkat cells, caspase-8-deficient Jurkat cells, and caspase-8-deficient Jurkat cells transfected with pCDN3.1caspase-8 were exposed to UVB (18 mJ) irradiation, followed by incubation in 0.5% calf serum for 8 h. (D) A431 cells were stably transfected with the indicated plasmids. (E) Serum-starved A431 cells expressing the indicated plasmids were exposed to UVB (18 mJ), followed by incubation in 0.5% calf serum for 8 h. (F) Serum-starved NIH 3T3 cells ectopically expressing Hsp90β were exposed to UVB (18 mJ) irradiation, followed by incubation in 0.5% calf serum, with or without MG132 (50 μM), for 8 h.

Caspase-8 cleaves and activates caspase-10.

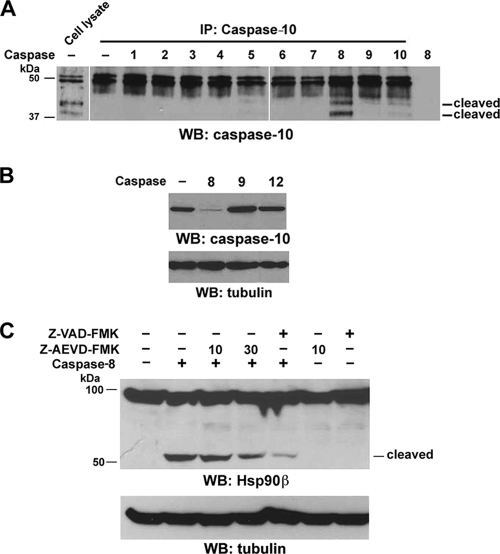

FAS and TNFR-1 bind their respective adaptor molecules FADD and TRADD, which recruit procaspase-8 and -10 to form the DISC (26). It is known that this recruitment of procaspase-8 and -10 leads to their autoproteolytic cleavage and activation. Activated caspase-10 can function independently of activated caspase-8 in death ligand-induced apoptosis (14, 17, 18, 27). Because caspase-8 and -10 are involved in Hsp90β cleavage upon UVB irradiation, we evaluated the relationship between the activation of caspase-8 and that of caspase-10. The incubation of active recombinant caspase-1 to -10 with immunoprecipitated caspase-10 in the absence of UVB stimulation showed that caspase-8 cleaved caspase-10 in a pattern similar to that found in cell lysates after UVB irradiation (Fig. 4A). In addition, overexpression of active caspase-8 sufficiently and significantly reduced pro-caspase-10 expression in 293T cells; caspase-9 and -12 did not (Fig. 4B). Pretreatment of 293T cells with the general caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK or the caspase-10 inhibitor Z-AEVD-FMK inhibited Hsp90β cleavage by caspase-8 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4C). These results indicate that caspase-8, functioning as an upstream regulator of caspase-10, cleaves and activates caspase-10, which leads to cleavage of Hsp90β.

FIG. 4.

Caspase-8 cleaves and activates caspase-10. Western immunoblotting (WB) analyses were carried out with the indicated antibodies. (A) Immunoprecipitated (IP) caspase-10 from A431 cells was incubated with the indicated recombinant caspases in reaction buffer at 37°C for 4 h. (B) pCDN3.1-caspase-10 was cotransfected with plasmids expressing caspase-8, -9, or -12 into 293T cells. (C) 293T cells were transfected with pCDN3.1 or pCDN3.1-caspase-8. The transfected cells were left untreated or were treated with Z-VAD-FMK (10 μM) or the indicated doses (μM) of Z-AEVD-FMK for 16 h.

UVB-induced autosecretion of FAS ligand contributes to caspase-10 activation.

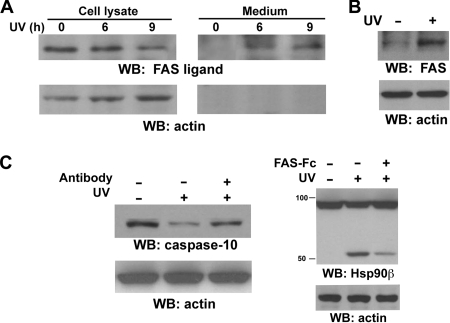

Caspase-10 is best known for being activated by ligand binding-induced trimerization of death receptors, such as FAS, TNFR, DR3, DR4 (TRAIL-R1), DR5 (TRAIL-R2), and DR6 (1, 8, 30). To test the possible involvement of death receptors in caspase-10 activation, serum-free media were collected after UVB irradiation of A431 cells. Immunoblotting with anti-FAS ligand antibodies showed that UVB resulted in increased secretion of FAS ligand from A431 cells, which was associated with a reduction of intracellular FAS ligand (Fig. 5A), whereas the lack of detectable actin in these media indicates that they were not contaminated with broken cells. Intriguingly, UVB irradiation induced upregulated FAS expression (Fig. 5B), which is consistent with the results of a previous report showing that UVB irradiation transiently increases FAS expression in mouse epidermis (10). Incubation with a neutralizing FAS ligand antibody (Fig. 5C, left panel) or a neutralizing FAS-Fc fusion protein that binds to FAS ligand (Fig. 5C, right panel) reduced UVB-induced cleavage of pro-caspase-10 (Fig. 5C, left panel) and Hsp90β (Fig. 5C, right panel), indicating that the secreted FAS ligand contributes to caspase-10 activation and Hsp90β cleavage.

FIG. 5.

UVB-induced autosecretion of FAS ligand contributes to caspase-10 activation. Western immunoblotting (WB) analyses were carried out with the indicated antibodies. (A) A431 cells were exposed to UVB (18 mJ), followed by incubation in non-serum-supplemented Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium for the indicated time. Cell lysates and precipitated proteins from serum-free medium were prepared. (B) A431 cells were exposed to UVB (18 mJ), followed by incubation in 0.5% calf serum for 12 h. (C) After being exposed to UVB (18 mJ), A431 cells were incubated with or without a neutralizing FAS ligand antibody (4 μg/ml) (left panel) or a FAS-Fc fusion protein (20 μg/ml) (right panel) for 9 h. This was followed by cell lysate preparation.

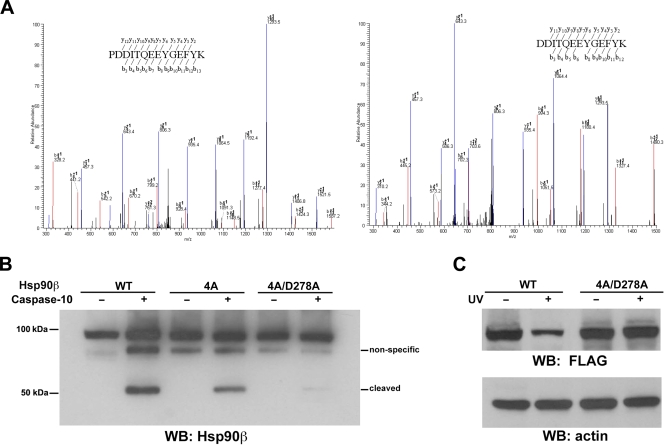

Caspase-10 cleaves Hsp90β at D278, P293, and D294.

An in vitro caspase reaction showed that caspase-10 cleaves Hsp90β and generates ∼55-kDa and ∼35-kDa fragments (Fig. 6A). The ∼55-kDa fragment can be recognized by an antibody against the C terminus of Hsp90β (Fig. 1), implying that caspase-10 cleaves residues close to the N terminus. To identify the cleavage sites of Hsp90β by caspase-10, we mutated several aspartic acids (D), including D264, -278, -294, -295, -311, and -314, in the region that is ∼35 kDa downstream from the N terminus. Nevertheless, mutations of these individual aspartic acids into alanines (A) did not block the cleavage of Hsp90β by caspase-10 (data not shown). An analysis of the tryptic digest of the ∼55-kDa fragment by LC-MS/MS revealed that caspase-10 appeared to have cleaved Hsp90β at peptide bonds between asparagine (N292) and proline (P293) and between P293 and D294 (Fig. 6A). The mutation of N292, P293, D294, and D295 into four alanines (4A) significantly reduced caspase-10-mediated Hsp90β cleavage in vitro (Fig. 6B). An additional combined mutation at D278A (4A/D278A), which is immediately adjacent to 4A, almost completely abolished Hsp90β cleavage by caspase-10. Consistent with these in vitro results, the expression of the Hsp90β (4A/D278A) mutant, but not that of WT Hsp90β, in A431 cells was resistant to UVB-induced downregulation (Fig. 6C). These results indicate that caspase-10 cleaves Hsp90β at D278, P293, and D294. Given that caspases usually cleave aspartic acid residues in position P1, our results indicate that caspase-10 may cleave non-aspartic acid residues, such as proline, under certain circumstances.

FIG. 6.

Caspase-10 cleaves Hsp90β at D278, P293, and D294. (A) An in vitro caspase reaction was carried out with purified Hsp90β, with or without purified caspase-10. A Coomassie blue-stained ∼55-kDa fragment was excised from an SDS-PAGE gel and digested and analyzed by MS. MS analysis of the semitryptic fragments PDDITQEEYGEFYK (left panel) and DDITQEEYGEFYK (right panel) indicates that caspase-10 cleaved Hsp90β at peptide bonds between N292 and P293 (left panel) and between P293 and D294 (right panel). (B) An in vitro caspase reaction was carried out with purified WT Hsp90β and Hsp90β 4A and Hsp90β 4A/D278A mutants, with or without purified caspase-10. Western immunoblotting (WB) analyses were carried out with an Hsp90β antibody. (C) A431 cells expressing FLAG-tagged WT Hsp90β or the Hsp90β 4A/D278A mutant were exposed to UVB (18 mJ) 9 h before being harvested. Immunoblotting analyses were carried out with the indicated antibodies.

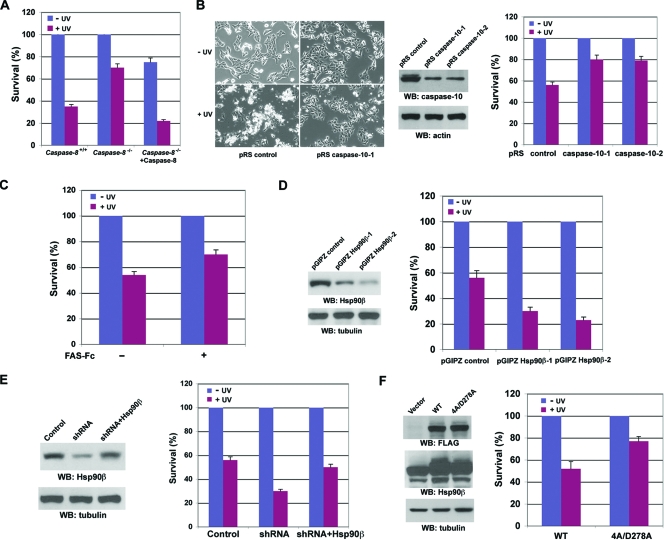

Downregulation of Hsp90β promotes UVB-induced cell apoptosis.

To determine the role of downregulation of Hsp90β by caspase-8 and -10 in apoptosis, we first evaluated the effect of deficiency or depletion of caspase-8 or -10 on UVB-induced cell death. Caspase-8-deficient Jurkat T cells, in contrast to their WT cells, displayed an enhanced resistance to UVB-induced apoptosis, as measured by the annexin V-FITC-PI staining (Fig. 7A) and nuclear condensation and fragmentation analysis (data not shown). Reexpression of caspase-8 in caspase-8-deficient Jurkat T cells promoted UVB-induced apoptosis. Similarly, A431 cells with shRNA-induced depletion of caspase-10 had fewer morphological changes than did A431 cells transfected with scrambled shRNA, which exhibited a detached, refractile, spherical, and shrunken phenotype in response to UVB irradiation (Fig. 7B, left panel). Consistent with the changes in cell morphology, fewer A431 cells with depleted caspase-10, caused by expressing shRNAs against two different regions of caspase-10 mRNA, underwent UVB-induced apoptosis (Fig. 7B, right panel). Consistent with the results showing that UVB-induced autosecretion of FAS ligand contributes to caspase-10 activation (Fig. 5C), incubation with a neutralizing FAS-Fc fusion protein after UVB irradiation reduced UVB-induced apoptosis (Fig. 7C). Because activation of caspase-8 and -10 leads to downregulation of Hsp90β by proteolytic cleavage, we evaluated the role of Hsp90β downregulation in UVB-induced apoptosis. Hsp90β was depleted by expressing shRNAs, and the downregulation of Hsp90β dramatically promoted UVB-induced cell death (Fig. 7D), which was rescued by ectopic overexpression of Hsp90β (Fig. 7E). In contrast, A431 cells stably expressing Hsp90β (4A/D278A) mutant were more resistant to UVB-induced apoptosis than were A431 cells expressing WT Hsp90β (Fig. 7F). These results indicate that UVB-induced downregulation of Hsp90β, mediated by caspase-8-dependent caspase-10 activation, promotes cell apoptosis and that Hsp90β cleavage is not merely a nonproductive side consequence of caspase activation.

FIG. 7.

Downregulation of Hsp90β promotes UVB-induced cell apoptosis. (A) Serum-starved Jurkat cells, caspase-8-deficient Jurkat cells, and caspase-8-deficient Jurkat cells transiently transfected with pCDN3.1caspase-8 were exposed to UVB (18 mJ) irradiation, followed by incubation in 0.5% calf serum for 24 h. Cells were stained with annexin V-FITC-PI and analyzed with a FACSCalibur flow cytometer. (B) A431 cells expressing a control shRNA or an shRNA against caspase-10 mRNA were exposed to UVB (18 mJ) irradiation, followed by incubation in 0.5% calf serum for 24 h. Pictures were taken with a digital camera mounted on a microscope at ×100 magnification (left panel). Western immunoblotting (WB) analyses of A431 cells expressing a control shRNA or two different shRNAs against caspase-10 mRNA were carried out with the indicated antibodies (middle panel). The collected cells were processed for an annexin V-FITC-PI apoptosis flow cytometric assay (right panel). (C) A431 cells were incubated with or without a FAS-Fc fusion protein (20 μg/ml) immediately after being exposed to UVB (18 mJ) for 24 h. The collected cells were analyzed with an annexin V-FITC-PI apoptosis flow cytometric assay. (D) Hsp90β expression levels in A431 cells expressing a control shRNA or two different shRNAs against Hsp90β mRNA were examined by an immunoblotting analysis with the indicated antibodies (left panel). These cells had been exposed to UVB (18 mJ) irradiation, followed by incubation in 0.5% calf serum for 24 h and annexin V-FITC and PI apoptosis flow cytometric assays (right panel). (E) A431 cells expressing pGIPZ control shRNA or pGIPZ Hsp90β shRNA-1 or coexpressing pGIPZ Hsp90β shRNA-1 and p2HG/hHsp90β were exposed to UVB (18 mJ) and then incubated in 0.5% calf serum for 24 h. The collected cells were processed for immunoblotting analysis with the indicated antibodies (left panel) and an annexin V-FITC-PI apoptosis flow cytometric assay (right panel). (F) Hsp90β expression levels in A431 cells expressing FLAG-Hsp90β WT or FLAG-Hsp90β 4A/D278A mutant were examined by an immunoblotting analysis with the indicated antibodies (left panel). These cells had been exposed to UVB (25 mJ) irradiation, followed by incubation in 0.5% calf serum for 24 h and annexin V-FITC-PI apoptosis flow cytometric assays (right panel). For all panels, the data represent means ± standard deviations from three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Hsp90β is the major form of Hsp90; it is involved in a variety of cellular functions through its regulation of many important signaling client proteins. Hsp90β is a direct substrate of caspase-10 in vitro, and activation of caspase-10, which can be induced by activated caspase-8, cleaves Hsp90β in vivo. Both caspase-8 and -10, acting as initiator caspases, contain two tandem repeats of the death effector domain (DED) and interact with FADD through homotypic interactions of their DEDs. Upon death ligand binding to their receptors, dimer and oligomer formations of caspase-8 and -10, induced by FADD, may be responsible for the self-activation of caspase-8 and -10 in the DISC (6). Although caspase-10 can function independently of caspase-8 (6), we found that caspase-8 cleaves caspase-10 and that caspase-8 inhibition blocked caspase-10-induced Hsp90β truncation in response to UVB irradiation; these findings strongly suggest that caspase-8 can directly activate caspase-10, which in turn cleaves Hsp90β. Intriguingly, UVB irradiation induced secretion of FAS ligand and upregulation of FAS expression, and blocking the binding of FAS ligand to its receptor with a neutralizing FAS ligand antibody reduced caspase-10 activation and Hsp90β cleavage. These results indicate that autocrine-secreted death ligand, in response to UVB irradiation, plays a pivotal role in caspase-8 and -10-mediated downregulation of Hsp90β.

Hsp90 has been shown to act as an antiapoptotic factor via several mechanisms (1). Hsp90 forms a cytosolic complex with Apaf-1 and inhibits cytochrome c-mediated Apaf-1 oligomerization and procaspase-9 activation (21). Hsp90 interacts with Bid, a proapoptotic member of the Bcl-2 family, and prevents TNF-α-induced Bid cleavage, which is involved in cytochrome c release (32). In addition to keeping proapoptotic factors in an inert state, Hsp90 regulates antiapoptotic proteins. Hsp90 modulates the stability of receptor-interacting protein, which functions as an antiapoptotic protein by regulating nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) activity (15). Hsp90 has been shown to regulate TNF-induced activation of IκB kinase (IKK) and NF-κB by interacting with the kinase domains of IKKα and -β and by forming a heterocomplex, which also contains NF-κB essential modulator and cochaperone protein Cdc37 (5). Hsp90 also directly interacts with and maintains the activity of Akt by inhibiting its dephosphorylation, and Hsp90 and Akt function together to inhibit the activity of proapoptotic kinase ASK1 (apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1) (2, 24, 31). Consistent with these findings, our results demonstrated that UVB induces Hsp90β downregulation by sequential activation of caspase-8 and -10. Inhibition of caspase-8 or -10 activation inhibited Hsp90β cleavage and largely inhibited UVB-induced apoptosis. Conversely, downregulation of Hsp90β by expression of its shRNA, which would be expected to relieve its inhibition of proapoptotic proteins and the protection of antiapoptotic proteins, promotes cell death in response to UVB irradiation.

Because Hsp90 is a molecular chaperone responsible for regulating numerous oncogenic proteins and because its overexpression has been detected in human cancers and is associated with poor prognosis, its inhibition would be a novel approach to simultaneously disrupting multiple signaling cascades to elicit apoptosis (3, 28). Hsp90 has become an attractive target for development of a small molecule inhibitor for cancer therapy. Similar to the effect induced by UVB, gamma radiation resulted in caspase-dependent Hsp90β cleavage (data not shown). Because irradiation results in the downregulation of Hsp90, thereby promoting apoptosis, cancer treatment with a combination of an Hsp90 inhibitor and irradiation for more complete downregulation of Hsp90, which should further enhance apoptosis, warrants further investigation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Junying Yuan (Harvard Medical School) for caspase-12 plasmid, Dean G. Tang and Michael Andreeff (University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center) for caspase-8-deficient Jurkat T cells, Didier Picard (Université de Genève) for p2HG/hHsp90β, Emad Alnemri (Thomas Jefferson University) for pKS-Rev-caspase-6, Seiji Kondo (M. D. Anderson Cancer Center) for pCDN3.1caspase-8, Bingliang Fang (M. D. Anderson Cancer Center) for pCDN3.1+caspase-3, and Jin Wang (Baylor College of Medicine) for pCDN3.1caspase-10. We thank Ann Sutton for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Pediatric Brain Tumor Foundation (Z.L.), a Brain Tumor Society research grant (Z.L.), a Phi Beta Psi Sorority research grant (Z.L.), an institutional research grant from the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center (Z.L.), and National Cancer Institute grant 5R01CA109035 (Z.L.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 20 April 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arya, R., M. Mallik, and S. C. Lakhotia. 2007. Heat shock genes—integrating cell survival and death. J. Biosci. 32595-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basso, A. D., D. B. Solit, G. Chiosis, B. Giri, P. Tsichlis, and N. Rosen. 2002. Akt forms an intracellular complex with heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) and Cdc37 and is destabilized by inhibitors of Hsp90 function. J. Biol. Chem. 27739858-39866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bishop, S. C., J. A. Burlison, and B. S. Blagg. 2007. Hsp90: a novel target for the disruption of multiple signaling cascades. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 7369-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Budihardjo, I., H. Oliver, M. Lutter, X. Luo, and X. Wang. 1999. Biochemical pathways of caspase activation during apoptosis. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 15269-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen, G., P. Cao, and D. V. Goeddel. 2002. TNF-induced recruitment and activation of the IKK complex require Cdc37 and Hsp90. Mol. Cell 9401-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, M., and J. Wang. 2002. Initiator caspases in apoptosis signaling pathways. Apoptosis 7313-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Csermely, P., T. Schnaider, C. Soti, Z. Prohaszka, and G. Nardai. 1998. The 90-kDa molecular chaperone family: structure, function, and clinical applications. A comprehensive review. Pharmacol. Ther. 79129-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Green, D. R., and J. C. Reed. 1998. Mitochondria and apoptosis. Science 2811309-1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hartl, F. U., and M. Hayer-Hartl. 2002. Molecular chaperones in the cytosol: from nascent chain to folded protein. Science 2951852-1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hill, L. L., A. Ouhtit, S. M. Loughlin, M. L. Kripke, H. N. Ananthaswamy, and L. B. Owen-Schaub. 1999. Fas ligand: a sensor for DNA damage critical in skin cancer etiology. Science 285898-900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Juo, P., C. J. Kuo, J. Yuan, and J. Blenis. 1998. Essential requirement for caspase-8/FLICE in the initiation of the Fas-induced apoptotic cascade. Curr. Biol. 81001-1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Juo, P., M. S. Woo, C. J. Kuo, P. Signorelli, H. P. Biemann, Y. A. Hannun, and J. Blenis. 1999. FADD is required for multiple signaling events downstream of the receptor Fas. Cell Growth Differ. 10797-804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim, T. S., C. Y. Jang, H. D. Kim, J. Y. Lee, B. Y. Ahn, and J. Kim. 2006. Interaction of Hsp90 with ribosomal proteins protects from ubiquitination and proteasome-dependent degradation. Mol. Biol. Cell 17824-833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kischkel, F. C., D. A. Lawrence, A. Tinel, H. LeBlanc, A. Virmani, P. Schow, A. Gazdar, J. Blenis, D. Arnott, and A. Ashkenazi. 2001. Death receptor recruitment of endogenous caspase-10 and apoptosis initiation in the absence of caspase-8. J. Biol. Chem. 27646639-46646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis, J., A. Devin, A. Miller, Y. Lin, Y. Rodriguez, L. Neckers, and Z. G. Liu. 2000. Disruption of hsp90 function results in degradation of the death domain kinase, receptor-interacting protein (RIP), and blockage of tumor necrosis factor-induced nuclear factor-kappaB activation. J. Biol. Chem. 27510519-10526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu, Z., S. Xu, C. Joazeiro, M. H. Cobb, and T. Hunter. 2002. The PHD domain of MEKK1 acts as an E3 ubiquitin ligase and mediates ubiquitination and degradation of ERK1/2. Mol. Cell 9945-956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin, D. A., R. M. Siegel, L. Zheng, and M. J. Lenardo. 1998. Membrane oligomerization and cleavage activates the caspase-8 (FLICE/MACHalpha1) death signal. J. Biol. Chem. 2734345-4349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muzio, M., B. R. Stockwell, H. R. Stennicke, G. S. Salvesen, and V. M. Dixit. 1998. An induced proximity model for caspase-8 activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2732926-2930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nathan, D. F., M. H. Vos, and S. Lindquist. 1997. In vivo functions of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Hsp90 chaperone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9412949-12956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niikura, Y., T. Nonaka, and S. Imajoh-Ohmi. 2002. Monitoring of caspase-8/FLICE processing and activation upon Fas stimulation with novel antibodies directed against a cleavage site for caspase-8 and its substrate, FLICE-like inhibitory protein (FLIP). J. Biochem. 13253-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pandey, P., A. Saleh, A. Nakazawa, S. Kumar, S. M. Srinivasula, V. Kumar, R. Weichselbaum, C. Nalin, E. S. Alnemri, D. Kufe, and S. Kharbanda. 2000. Negative regulation of cytochrome c-mediated oligomerization of Apaf-1 and activation of procaspase-9 by heat shock protein 90. EMBO J. 194310-4322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pratt, W. B. 1998. The hsp90-based chaperone system: involvement in signal transduction from a variety of hormone and growth factor receptors. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 217420-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reed, J. C., K. Doctor, A. Rojas, J. M. Zapata, C. Stehlik, L. Fiorentino, J. Damiano, W. Roth, S. Matsuzawa, R. Newman, S. Takayama, H. Marusawa, F. Xu, G. Salvesen, and A. Godzik. 2003. Comparative analysis of apoptosis and inflammation genes of mice and humans. Genome Res. 131376-1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sato, S., N. Fujita, and T. Tsuruo. 2000. Modulation of Akt kinase activity by binding to Hsp90. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9710832-10837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sreedhar, A. S., E. Kalmar, P. Csermely, and Y. F. Shen. 2004. Hsp90 isoforms: functions, expression and clinical importance. FEBS Lett. 56211-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tibbetts, M. D., L. Zheng, and M. J. Lenardo. 2003. The death effector domain protein family: regulators of cellular homeostasis. Nat. Immunol. 4404-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang, J., H. J. Chun, W. Wong, D. M. Spencer, and M. J. Lenardo. 2001. Caspase-10 is an initiator caspase in death receptor signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9813884-13888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whitesell, L., and S. L. Lindquist. 2005. HSP90 and the chaperoning of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 5761-772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xia, Y., J. Wang, T. J. Liu, W. K. Yung, T. Hunter, and Z. Lu. 2007. c-Jun downregulation by HDAC3-dependent transcriptional repression promotes osmotic stress-induced cell apoptosis. Mol. Cell 25219-232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yan, N., and Y. Shi. 2005. Mechanisms of apoptosis through structural biology. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2135-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang, R., D. Luo, R. Miao, L. Bai, Q. Ge, W. C. Sessa, and W. Min. 2005. Hsp90-Akt phosphorylates ASK1 and inhibits ASK1-mediated apoptosis. Oncogene 243954-3963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao, C., and E. Wang. 2004. Heat shock protein 90 suppresses tumor necrosis factor alpha induced apoptosis by preventing the cleavage of Bid in NIH3T3 fibroblasts. Cell Signal. 16313-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhuang, L., B. Wang, and D. N. Sauder. 2000. Molecular mechanism of ultraviolet-induced keratinocyte apoptosis. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 20445-454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]