Abstract

Objective

To estimate the prevalence, genotypes, and individual-level correlates of high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) among women aged 57–85.

Methods

Community-residing women (n=1550), aged 57–85, were drawn from a nationally-representative probability sample. In-home interviews and biomeasures, including a self-collected vaginal specimen, were obtained between 2005 and 2006. Specimens were analyzed for high-risk HPV DNA using probe hybridization and signal amplification (hc2); of 1,028 specimens provided, 1,010 were adequate for analysis. All samples testing positive were analyzed for HPV DNA by L1 consensus polymerase chain reaction followed by type-specific hybridization.

Results

The overall population-based weighted estimate of high-risk HPV prevalence by hc2 was 6.0% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 4.5 to 7.9). Current marital and smoking status, frequency of sexual activity, history of cancer, and hysterectomy were associated with high-risk HPV positivity. Among high-risk HPV+ women, 63% had multiple type infections. HPV 16 or 18 was present in 17.4% of all high-risk HPV+ women. The most common high-risk genotypes among high-risk HPV+ women were HPV 61 (19.1%), 31 (13.1%), 52 (12.9%), 58 (12.5%), 83 (12.3%), 66(12.0%), 51 (11.7%), 45 (11.2%), 56 (10.3%), 53 (10.2%), 16 (9.7%), and 62 (9.2%). Being married and having an intact uterus were independently associated with lower prevalence of high-risk HPV. Among unmarried women, current sexual activity and smoking were independently and positively associated with high-risk HPV infection.

Conclusions

In this nationally representative population, nearly 1 in 16 women aged 57–85 were found to have high-risk HPV and prevalence was stable across older age groups.

INTRODUCTION

Nearly all cases of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cancer are attributable to sexually-transmitted genital tract infection with one or more of approximately 15 oncogenic, or high-risk, types of human papillomavirus (HR-HPV) (1, 2). In the US, 20% of cervical cancer cases, but 36% of cervical cancer deaths, occur in women age 65 and older(3). Annual direct medical costs for preventing and treating HPV-related anogenital disease across the whole US population are estimated to exceed $4 billion; morbidity and cost among older women have not been quantified(4).

The natural history of genital tract HPV in older women is poorly understood. A bimodal age distribution in HPV prevalence has been observed in some populations (5–8). The second peak in HPV prevalence in older women, where observed, is thought to result primarily from persistent infection (9). HR types may be more likely than LR types to persist (10, 11). Susceptibility to and failure to clear genital HPV infection may be affected by immune function, sex hormone status, or vaginal epithelial function (9).

Women age 65 and older will comprise 14.8% of the US population by 2010, and 21.7% by 2030 (12). Many older women are sexually active (13) and engage in other behaviors, such as smoking (14), that are known risk factors for genital tract HPV in younger women. Older women initiating new sexual relationships in later life may be exposed to HPV strains for the first time(15). Substantially more women are aging with their uterus intact (16) and therefore remain vulnerable to cervical HPV disease and Pap smear abnormalities. Public health messages and commercial advertising about cervical cancer screening, genital HPV, and the HPV vaccine reach women (and men) of all ages and generate public concern about vulnerability to infection, transmission, and sequelae (17). The age-group specific population prevalences of HR-HPV among older women in the US and its consequences for older women’s health are unknown.

This study aims to extend recent HPV prevalence data (18) by estimating the prevalence, genotypes, and individual-level correlates of HR-HPV among women ages 57–85.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A nationally-representative probability sample of community-dwelling adults aged 57–85 was generated from US households screened in 2004 for the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) which was seeking participants ages 56 and younger. Of 4017 eligible cases, 3005 (1455 men, 1550 women) were interviewed between July 2005 and March 2006 yielding a weighted response rate of 75.5% (unweighted 74.8%). In-home interviews conducted by trained female field staff (unless the respondent requested a male) included an interviewer-administered, standardized, computer-assisted questionnaire and biological measures(19). A detailed description of the National Social Life Health and Aging Project (NSHAP) study population and study design has been previously published(13).

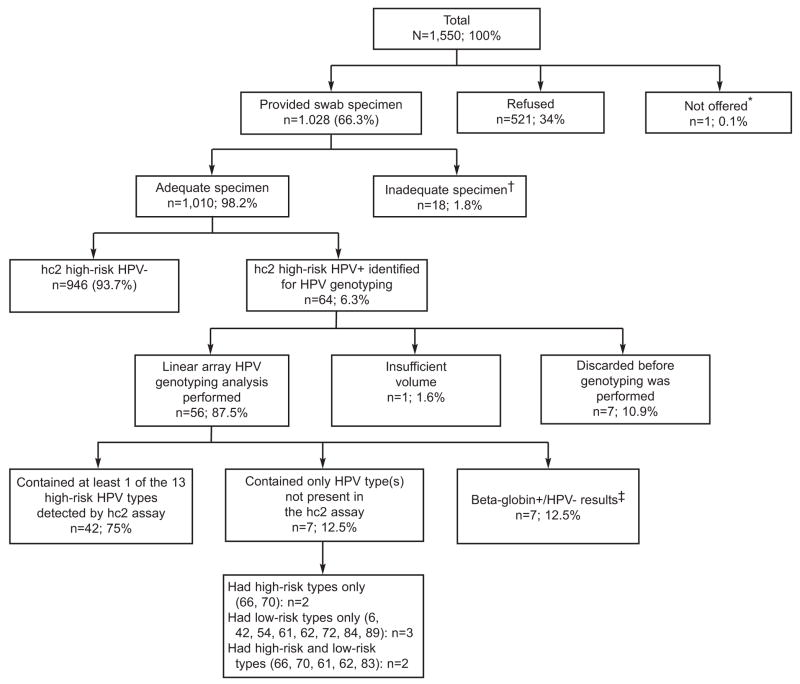

All women selected for participation in NSHAP were eligible for this study. Of 1550 eligible women, 1028 (66.3% unweighted, 67.5% weighted) agreed to submit a self-administered vaginal swab specimen (Figure 1). Of these, 9 respondents tried but were unable to collect the vaginal swab, equipment problems occurred in the collection of 6 swabs, 2 specimens were lost in transit and 1 specimen was missing in error. Thus, 1010 (98.0%, 66.2% overall) specimens were adequate for analysis.

Figure 1.

National Social Life Health & Aging Project HPV study participation and test results summary (n, unweighted percentages). hc2, probe hybridization and signal amplification; HPV, human papillomavirus

*Due to computer entry error for respondent gender, this respondent was not offered vaginal swab testing.

†Tried, but unable to provide specimen (n=9), Equipment/material problems (n=6), Lost/ruined (n=3)

‡Negative for all 37 anogenital high-risk and low-risk HPV genotypes detectable by the Linear Array assay

Non-responders to the vaginal swab protocol were significantly more likely than responders to be older (>75 years), have less than high school education (Table 1), and were less likely to report: a recent pelvic examination, menopausal prescription hormone use, and frequent sexual activity in the past year(19). A physical or health problem was the most common recorded reason for not submitting a vaginal specimen. The protocol was approved by the University of Chicago and NORC Institutional Review Boards; all respondents gave written informed consent.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Vaginal Swab Specimen Responders (N=1028a) and Non-Responders (N=521a)

| Characteristic | Responders (%)b | Non-Responders (%)b |

|---|---|---|

| Overall (age 57–85) | 67.6 (63.6, 71.2) | 32.4 (28.8, 36.4) |

| Age group | p <0.001c | |

| 57–64 | 41.0 (37.6, 44.6) | 35.2 (30.3, 40.5) |

| 65–74 | 36.4 (33.1, 39.8) | 31.4 (26.6, 36.7) |

| 75–85 | 22.6 (20.2, 25.2) | 33.3 (28.6, 38.5) |

| Race/Ethnicityd | p = 0.86 c | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 80.4 (75.1, 84.7) | 80.8 (75.0, 85.6) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 10.6 (7.8, 14.3) | 11.3 (7.8, 16.2) |

| Hispanic | 7.1 (3.8, 12.9) | 5.7 (3.5, 9.4) |

| Other | 1.9 (0.9, 3.7) | 2.1 (1.1, 4.1) |

| Current marital status | p = 0.29c | |

| Married | 56.4 (53.3, 59.5) | 53.7 (47.6, 59.6) |

| Living with partner | 2.5 (1.5, 4.4) | 1.8 (0.7, 4.4) |

| Widowed | 23.5 (20.5, 26.8) | 28.4 (23.9, 33.4) |

| Separated | 1.3 (0.8, 2.1) | 0.6 (0.2, 1.6) |

| Divorced | 13.2 (11.3, 15.4) | 11.3 (7.8, 16.0) |

| Never married | 3.0 (2.1, 4.3) | 4.3 (2.7, 6.8) |

| Education | p = 0.02c | |

| Less than high school | 17.7 (14.3, 21.7) | 25.3 (20.3, 31.2) |

| High school or equivalent | 29.6 (26.2, 33.2) | 29.4 (24.9, 34.3) |

| Some college/Assoc. degree | 34.9 (30.7, 39.4) | 27.4 (22.4, 33.0) |

| Bachelors degree or higher | 17.8 (14.6, 21.6) | 18.0 (13.6, 23.4) |

| Insurance status | p = 0.41 c | |

| Medicare | 63.5 (59.1, 67.7) | 64.9 (59.0, 70.5) |

| Private without Medicare | 32.1 (27.8, 36.7) | 29.4 (23.7, 35.7) |

| VA, Medicaid, other | 3.7 (2.5, 5.5) | 4.1 (2.2, 7.4) |

| No insurance | 0.7 (0.4, 1.5) | 1.6 (0.7, 4.0) |

Unweighted frequencies;

Estimates are weighted to account for differential probabilities of selection and differential non-response;

P-value represents global test of significance;

Race and ethnicity were self-reported using the questions: “Do you consider yourself primarily white or Caucasian, black or African-American, American Indian, Asian, or something else?” and “Do you consider yourself Hispanic or Latino?”

Race and ethnicity were self-reported. Sex was defined as: “any mutually voluntary activity with another person that involves sexual contact, whether or not intercourse or orgasm occurs.” For those reporting a current (prior 12 months) sexual partner, sexual frequency, condom use, partner gender, and were collected for up to the two most recent partners. Partner infidelity (known or perceived) was collected for up to the two most recent partners for a randomly selected two-thirds of survey respondents. Questions about sexual activity were refused by 2–7% of respondents. Data regarding the most recent sexual partner are used in the analyses reported here.

Smoking was assessed using questions adapted from a major epidemiologic study of aging (20). Physical health was self-rated using the standard 5-point scale and co-morbidities were assessed using a modified Charlson Index (21). Current medications were logged and classified according to the Multum® Drug Database: Lexicon Plus version(22). Other health and health behavior variables were obtained by self report.

Women were given an illustrated instruction card with collection materials (23) and directed to a bathroom or other private room(19). The swab for HPV testing was secured inside a labeled tube containing 1 mL Specimen Transport Medium™(STM; Digene Corp.). Tubes were stored on wet ice until day’s end and shipped overnight on cold packs to the University of Pittsburgh, Magee-Women’s Hospital Department of Pathology clinical microbiology laboratory of JAJ.

HR-HPV DNA testing was performed using the Hybrid Capture 2® (hc2) High-Risk HPV DNA Test™ (Catalog No. 5199 1220; Digene Corporation, Gaithersburg, MD) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The HR hc2 signal amplification assay contains a cocktail of probes complementary to 13 HR-HPV types (HPV 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, and 68). In addition to the kit controls, an external sample processing control for adequate cells lysis (HeLa cells, which contain integrated HPV 18 DNA), was processed with each batch of specimens. Specimens with Relative Light Unit/Cutoff Values ≥ 1.0, obtained using the Digene Microplate Luminometer 2000 (DML 2000™) Instrument were considered positive for HR-HPV DNA.

Genotyping was performed on 56 hc2 HR-HPV positive specimens (Figure 1) using the Linear Array HPV Genotyping Test (RUO) and Linear Array Detection Kit (Roche Molecular Systems Inc., Pleasanton, CA). Only hc2 HR-HPV positive specimens were genotyped for this study. The denatured specimens were stored at −20°C before being thawed, neutralized, and genotyped. For compatibility with the QIAamp® MinElute™ Media Kit protocol for DNA extraction (Cat. #57704, QIAGEN, Valencia, CA), 250 microliters of each denatured STM was re-acidified to a pH just below 7.0 and the entire volume extracted. Fifty microliters of the final 120 μL extract volume were amplified by PCR in a master mix containing hot-start Taq polymerase and biotin-labeled PGMY09/11 primer set to amplify 37 different anogenital HPV genotypes (~450 base pair target) along with a primer set to human beta-globin (268 base pair target), which served as an internal control for DNA amplification. Thermocycling was performed using the Gold-plated 96-Well GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (Part No. 4314878; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) thermocycler. Amplicon denaturation and detection was carried out using the Linear Array Detection Kit. For each specimen to be considered valid, both the high- and low-level beta-globin controls had to yield a visible band on the blot. For each run to be considered valid, both positive and negative controls had to perform as expected. The ambiguous XR/52 probe data were handled as follows: HPV type 52 was considered positive only when the HPV GT52/33/35/58 band alone was visible. Although co-infection with HPV type 52 cannot be ruled out in cases where both the HPV GT52/33/35/58 band and one or more of the individual GT33, GT35 and/or GT58 bands were visible, we interpreted those specimens as negative for HPV type 52. To ensure reproducibility, 22 of the 56 specimens were randomly selected and retested. Without exception, the number of bands and their relative staining intensities were similar between runs.

The analytic sample consisted of 1010 responders who provided an adequate vaginal self-swab specimen. HR-HPV prevalences (at least one HR genotype present by hc2) were estimated with 95% confidence intervals obtained using a logit transform to ensure that the confidence limits would fall between 0 and 1. Logistic regression was used to model associations between HR-HPV and individual factors. All analyses accounted for the survey sampling design through incorporation of sampling strata and clusters, as well as weights that adjusted for differential probability of selection and differential non-response. Standard errors were computed using the Taylor linearization method (24). Estimates in tables are marked if the variance estimate is based on fewer than 12 strata with observations in both primary sampling units, following guidelines for the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey(25). Results were not adjusted for multiple testing. A sensitivity analysis was conducted, in which all analyses were repeated with missing HR-HPV values recoded as HR-HPV negative (n=539, Figure 1). Analyses were conducted using Stata 10.0 (26).

Prior to analysis, independent variables measured on a continuous scale or as counts were categorized because of linearity assumptions underlying the use of continuous covariates. Lifetime number of sex partners was categorized as 0, 1, or 2 or more. Age was categorized as 57–64, 65–74, and 75–85 years for consistency with previous studies (27) and the age structure of the NSHAP sample. Duration since last menstrual period was broken into decades, and then decades were collapsed as indicated by model fit using the criteria described below. Categories were collapsed prior to analysis if necessary to obtain adequate numbers of observations and cases within each category. During analysis, categories that did not differ significantly and had similar odds ratios were collapsed, provided that the collapsed categories were clinically meaningful. Univariable results are reported with minimal collapsing. Selected clinically relevant interactions were tested: between married and each of the sexual behavior variables (lifetime number of sex partners, sex in the last year, condom use) and between duration since last menstrual period and hysterectomy.

Multivariable logistic models were fit to identify independent correlates of HR-HPV. Terms considered for inclusion were the significant interaction of marital status (married versus not) by sex in the last year, factors significant at p<0.20 in univariable analysis, and potential confounders (age, lifetime number of sex partners). Model selection was conducted using a stepwise approach, keeping within the limitations of the number of HR-HPV cases(28). Terms were retained if significant at p≤0.05 or if they modified the effect of a significant covariate. Multivariable analysis was conducted for the entire sample and for women not currently married; multivariable analysis among married women was precluded by the small number of HR-HPV cases (n=19).

RESULTS

The mean age of respondents was 68 years, mean age at menopause was 46 years, mean duration since menopause was 22 years, mean lifetime number of sex partners was 4.5 (median 2) and mean number of pregnancies was 2.8. The population prevalence of HR-HPV was estimated to be 6.0% (95% CI = 4.5 to 7.9). This corresponds to 1.8 (95% CI = 1.4 to 2.4) million females ages 57–85 with prevalent HR-HPV infection, using 2006 Census estimates (29).

HR-HPV prevalence was estimated according to sociodemographic characteristics (Table 2). Prevalence of HR-HPV infection did not differ significantly by age group, race/ethnicity, education, or insurance status. Current marital status was a strong, significant predictor of HR-HPV infection. Prevalence was lowest among those currently married and was highest among those who were divorced.

Table 2.

Estimated High-Risk HPV Prevalence Using Digene hc2 Assay by Demographic Characteristics

| Characteristic | Na | HR-HPV Prevalence (%)b | Odds Ratio (95% CI)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (age 57–85) | 1,010 | 6.0 (4.5, 7.9) | - |

| Age groupc | p = 0.73d | ||

| 57–64 | 332 | 5.8 (3.4, 9.8) | 1.00 [Referent] |

| 65–74 | 376 | 6.8 (4.3, 10.6) | 1.19 (0.53, 2.68) |

| 75–85 | 302 | 5.0 (2.6, 9.4) | 0.85 (0.36, 2.02) |

| Race/Ethnicitye | p = 0.13d | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 693 | 6.1 (4.5, 8.4) | 1.00 [Referent] |

| Non-Hispanic black | 187 | 8.4 (4.0, 16.7) | 1.43 (0.62, 3.29) |

| Hispanic | 108 | 2.6 (1.1, 6.2)* | 0.42 (0.16, 1.16) |

| Current marital statusf | p = 0.0001d | ||

| Married | 483 | 3.6 (2.3, 5.7) | 1.00 [Referent] |

| Widowed | 318 | 6.1 (3.7, 9.9) | 1.75 (0.90, 3.39) |

| Divorced | 132 | 13.6 (9.2, 19.7) | 4.22 (2.38, 7.49) |

| Never married | 34 | 9.7 (3.1, 26.5)* | 2.88 (0.79, 10.6) |

| Education | p = 0.67d | ||

| Less than high school | 233 | 7.5 (4.0, 13.8) | 1.00 [Referent] |

| High school or equivalent | 280 | 4.7 (2.7, 8.0) | 0.61 (0.26, 1.40) |

| Some college/Assoc. degree | 328 | 5.8 (3.4, 9.6) | 0.75 (0.29, 1.93) |

| Bachelors degree or higher | 169 | 7.0 (3.4, 14.0) | 0.92 (0.33, 2.56) |

| Insurance statusg | p = 0.70d | ||

| Medicare | 572 | 5.3 (3.7, 7.5) | 1.00 [Referent] |

| Private without Medicare | 226 | 5.8 (3.2, 10.6) | 1.12 (0.51, 2.43) |

| VA, Medicaid, other | 35 | 9.4 (2.3, 31.5)* | 1.87 (0.40, 8.72) |

Unweighted frequencies;

Estimates are weighted to account for differential probabilities of selection and differential non-response. The unweighted total number of HR-HPV cases was 64. An asterisk indicates the variance estimate is based on fewer than 12 strata with observations in both primary sampling units;

HR-HPV prevalence also did not differ by age considered as a continuous covariate or categorized into 5-year intervals. Polynomial terms (age squared, age cubed) were tested and were non-significant;

P-value represents global test of significance;

Excluding ‘Other’ race (n=18, no cases). Race and ethnicity were self-reported using the questions: “Do you consider yourself primarily white or Caucasian, black or African-American, American Indian, Asian, or something else?” and “Do you consider yourself Hispanic or Latino?”;

Excluding ‘Separated’ (n=22) and ‘Non-marital cohabiting relationship’ (n=21) due to small sample size;

Excluding ‘No insurance’ (n=8, no cases)

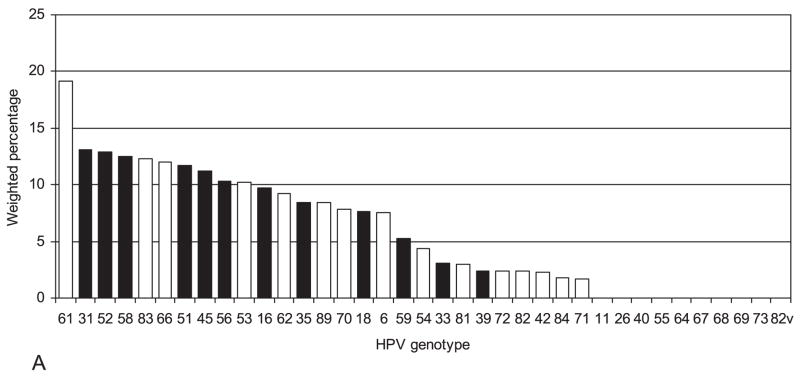

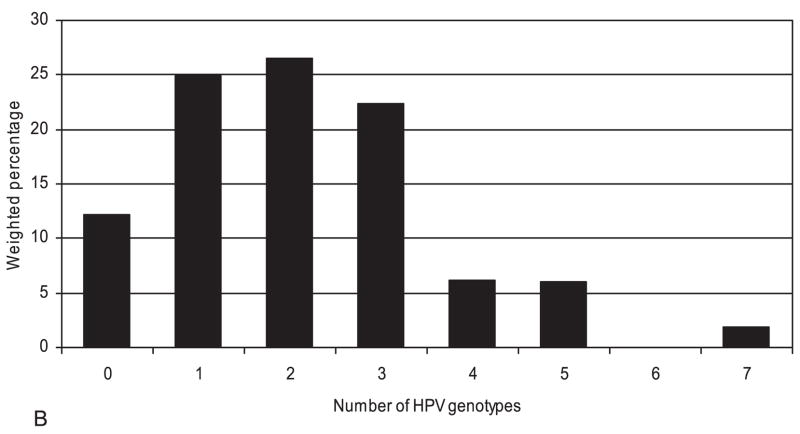

The frequencies of HPV genotypes were determined for 56 of the 64 HR hc2-positive specimens (Figure 1). Figure 2 illustrates their distribution (2A) and co-presence (2B). One or more of the four genotypes included in the quadrivalent HPV vaccine (6, 11, 16, 18) was detected in 27.2% of women with HR-HPV, although zero cases of HPV 11 were found. Nearly two thirds (63%) of women with HR-HPV had multiple types detected. Among 49 specimens with any HR-HPV genotype detected, 37 contained 2 or more genotypes. The most common HR genotypes found among HR-HPV+ women were HPV 61 (19.1%), 31 (13.1%), 52 (12.9%), 58 (12.5%), 83 (12.3%), 66(12.0%), 51 (11.7%), 45 (11.2%), 56 (10.3%), 53 (10.2%), 16 (9.7%), and 62 (9.2%). No specimens tested positive for both HR-HPV 16 and 18; HPV 16 or 18 was present in 17.4% of all HR-HPV+ women. These genotype prevalences may be underestimates of the prevalences in the entire population because genotyping was limited to women who tested positive for HR-HPV.

Figure 2.

A. HPV genotype distribution among 56 hc2 high-risk HPV positive specimens B. Number of HPV genotypes present among 56 hc2 high-risk HPV positive specimens Note: Weighted percentages underestimate population prevalences because high-risk HPV negative women were not genotyped. Standard errors are not shown because they are based on fewer than 8 variance strata with observations in both primary sampling units. hc2, probe hybridization and signal amplification; HPV, Human papillomavirus

Behavioral and health factors significantly associated with higher HR-HPV prevalence in bivariate analyses included current smoking, cancer, and hysterectomy. While data on prior chemotherapy use were unavailable, 47 women (4.6% of HR-HPV negative and 12.6% of HR-HPV positive) were currently using an antineoplastic agent. HR-HPV was positively associated with current chemotherapy use (OR=2.99, 95% CI = 1.17 to 7.68, p=0.02). HR-HPV prevalence was also associated with sex in the prior 12 months, but the nature of the association differed between married and unmarried women (Table 3).

Table 3.

Estimated High-Risk HPV Prevalence Using Digene hc2 Assay by Behavioral and Health Characteristics

| Characteristic | Na | HR-HPV Prevalence (%)b | Odds Ratio (95% CI)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual Behavior | |||

| Lifetime number of sex partners | p = 0.10c | ||

| 0 | 87 | 4.4 (1.3, 13.8) | 1.00 [Referent] |

| 1 | 300 | 2.8 (1.2, 6.5) | 0.63 (0.15, 2.73) |

| ≥2 | 542 | 7.7 (5.6, 10.6) | 1.81 (0.50, 6.64) |

| Sex within the last 12 months | |||

| ○ Among married | p = 0.49 | ||

| No | 159 | 4.7 (2.4, 9.2) | 1.00 [Referent] |

| Yes | 313 | 3.2 (1.5, 6.6) | 0.67 (0.21, 2.13) |

| ○ Among unmarried | p = 0.01 | ||

| No | 466 | 6.8 (4.4, 10.3) | 1.00 [Referent] |

| Yes | 57 | 23.7 (11.6, 42.5)* | 4.29 (1.47, 12.5) |

| Health Behavior | |||

| Current self-reported smoking status | p = 0.04 | ||

| Non-smoker, including former smoker | 874 | 5.5 (4.0, 7.5) | 1.00 [Referent] |

| Current smoker | 136 | 9.1 (5.9, 13.8) | 1.73 (1.03, 2.91) |

| Last Pap smear test | p = 0.72c | ||

| Within the past year | 408 | 5.0 (3.0, 8.1) | 1.00 [Referent] |

| Between 1 and 5 years ago | 353 | 6.6 (4.2, 10.3) | 1.35 (0.64, 2.83) |

| More than 5 years agod | 192 | 5.7 (3.3, 9.9) | 1.17 (0.52, 2.65) |

| Last pelvic examination | p = 0.45c | ||

| Within the past year | 413 | 4.8 (2.8, 8.0) | 1.00 [Referent] |

| Between 1 and 5 years ago | 357 | 7.1 (4.5, 11.1) | 1.53 (0.69, 3.38) |

| More than 5 years agoe | 176 | 5.2 (3.0, 8.9) | 1.09 (0.47, 2.57) |

| Health Characteristics | |||

| Self-rated physical health | p = 0.54 | ||

| Fair to Excellent | 934 | 5.9 (4.4, 7.9) | 1.00 [Referent] |

| Poor | 71 | 8.1 (2.9, 20.7)* | 1.42 (0.45, 4.44) |

| Co-morbidities | p = 0.19c | ||

| 0–1 | 523 | 5.0 (3.2, 7.7) | 1.00 [Referent] |

| 2 | 244 | 6.0 (3.6, 9.9) | 1.23 (0.59, 2.57) |

| 3–9 | 243 | 8.6 (5.4, 13.6) | 1.80 (0.95, 3.40) |

| Cervical dysplasia | p = 0.95 | ||

| No | 850 | 5.7 (4.2, 7.8) | 1.00 [Referent] |

| Yes | 75 | 5.9 (2.2, 14.9) | 1.03 (0.34, 3.16) |

| Any cancer | p = 0.04 | ||

| No | 886 | 5.2 (3.8, 7.3) | 1.00 [Referent] |

| Yes | 124 | 11.5 (6.1, 20.8) | 2.35 (1.05, 5.28) |

| Total number of pregnancies | p = 0.90 c | ||

| 0 | 66 | 8.1 (2.8, 21.0) | 1.00 [Referent] |

| 1 | 81 | 4.4 (1.3, 13.6) | 0.52 (0.10, 2.85) |

| 2 | 197 | 6.8 (3.9, 11.4) | 0.83 (0.25, 2.69) |

| 3 | 218 | 6.3 (3.2, 12.1) | 0.76 (0.21, 2.84) |

| 4 or more | 447 | 5.3 (3.4, 8.2) | 0.64 (0.21, 1.96) |

| Hysterectomyf | p = 0.02 c | ||

| Never | 553 | 3.5 (2.2, 5.5) | 1.00 [Referent] |

| After menopause | 91 | 9.3 (3.8, 21.2) | 2.82 (0.91, 8.70) |

| Before menopause | 359 | 8.8 (5.8, 13.3) | 2.66 (1.34, 5.30) |

| Duration since last menstrual period (years) | p = 0.13c | ||

| <10 | 114 | 2.3 (0.7, 7.7) | 1.00 [Referent] |

| 10–19 | 230 | 4.0 (1.9, 8.2) | 1.77 (0.43, 7.33) |

| 20–29 | 313 | 9.6 (6.3, 14.6) | 4.52 (1.18, 17.3) |

| 30–39 | 194 | 6.9 (3.9, 11.9) | 3.16 (0.79, 12.6) |

| 40–63 | 71 | 7.7 (2.2, 23.8)* | 3.51 (0.36, 34.3) |

| Prescription hormone use since menopause | p = 0.99 | ||

| No | 532 | 6.0 (4.2, 8.5) | 1.00 [Referent] |

| Yes | 475 | 6.0 (4.1, 8.8) | 1.00 (0.60, 1.67) |

Unweighted frequencies;

Estimates are weighted to account for differential probabilities of selection and differential non-response. The unweighted total number of HR-HPV cases was 64. An asterisk indicates the variance estimate is based on fewer than 12 strata with observations in both primary sampling units;

P-value represents global test of significance;

Includes 20 women who reported never having a Pap smear test;

Includes 33 women who reported never having a pelvic exam;

Includes total and supracervical hysterectomy

HR-HPV prevalence was significantly higher among women who reported 2 or more sexual partners over their lifetime compared to those who reported one or none (OR = 2.54, 95% CI = 1.07 to 6.02, p=0.04). Only 3 women (1 hc2 negative, 2 hc2 positive) reported having more than 1 current sexual partner. Very few women reported condom use (1.5%, 95% CI = 0.9 to 2.6), ever being diagnosed with cervical cancer (1.4%, 95% CI = 0.7 to 2.7), a sexually transmitted infection (STI) other than HPV (11%, 95% CI = 9.1 to 13.9), or genital warts (2%, 95% CI = 1.0 to 3.6). HR-HPV was detected in 4.4% of women who reported never having had sex.

HR-HPV prevalence was significantly associated with having had sex in the prior 12 months only among unmarried (including formerly married) women (Table 3), corresponding to a significant interaction of marital status with sex in this time period (p=0.03). Among married women, HR-HPV prevalence did not differ significantly between no sex and infrequent sex in the prior 12 months, while more frequent sex (more than once a month) was significantly associated with a decreased prevalence of HR-HPV (OR = 0.12, 95% CI = 0.03 to 0.45, p=0.002). Spousal infidelity was reported by 5.9% of married women and was significantly associated with having HR-HPV (OR = 5.39, 95% CI = 1.43 to 20.4, p=0.01). Too few cases of HPV (n=12) occurred among unmarried women who reported sex within the past year to further evaluate the effect of frequency of sex in this subgroup. Due to heterogeneity and sparse data on the timing and nature of the relationship with the most recent sexual partner among unmarried women, the effects of partner infidelity in this subgroup were not explored.

The prevalence of hysterectomy, which was significantly associated with higher HR-HPV prevalence, was 46% (95% CI = 41.9 to 49.2). Women who had a hysterectomy did not differ from those who did not with respect to sexual behavior, current smoking, demographic characteristics, history of cervical dysplasia, or number of pregnancies Hysterectomy was significantly associated with poorer self-rated health (very poor, poor versus higher rating: OR = 1.73, 95% CI = 1.18 to 2.52). Among women reporting pre-menopausal hysterectomy, HR-HPV prevalence did not differ between those with concurrent bilateral oophorectomy and those with at least one remaining ovary (p=0.46). Among women who did not have a hysterectomy, the likelihood of HR-HPV presence was significantly higher if more than 20 years had elapsed since the last menstrual period (age-adjusted OR = 9.25, 95% CI = 2.63 to 32.5, p=0.001).

In multivariable analysis, marital status and hysterectomy were independent correlates of HR-HPV detection, adjusted for age (Table 4). Among unmarried women, higher HR-HPV prevalence was independently associated with sex in the prior 12 months and current smoking, adjusted for age and lifetime number of sex partners. While the number of cases of HR-HPV among married women was too small to conduct a full multivariable analysis, the association of more frequent sex with lower HR-HPV remained after adjustment for age and lifetime number of sex partners.

Table 4.

Multivariate Analysis of Factors Associated with High-Risk HPV Positivity Among Women Ages 57–85

| Characteristic | Odds Ratio (95% CI)a | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Womenb | |||

| Married | p = 0.001 | ||

| No | 1.00 [Referent] | ||

| Yes | 0.38 (0.22, 0.66) | ||

| Hysterectomy | p = 0.01 | ||

| No | 1.00 [Referent] | ||

| Yes | 2.63 (1.37, 5.04) | ||

| Unmarried Womenc,d | |||

| Sex within the last 12 months | p = 0.02 | ||

| No | 1.00 [Referent] | ||

| Yes | 3.94 (1.23, 12.6) | ||

| Current smoker | p = 0.01 | ||

| No | 1.00 [Referent] | ||

| Yes | 3.54 (1.39, 8.98) | ||

Estimates are weighted to account for differential probabilities of selection and differential non-response;

Estimates are adjusted for age. Candidate covariates also included race and ethnicity, smoking status, any cancer, number of co-morbidities, lifetime number of sex partners, sex within the last 12 months, and the interaction of married and sex within the last 12 months. The unweighted total number of HR-HPV cases was 64;

Estimates are adjusted for age and lifetime number of sex partners. Candidate covariates also included race and ethnicity, hysterectomy, any cancer, and number of co-morbidities. The unweighted total number of HR-HPV cases among unmarried women was 45.

The number of cases of HPV among married women (n=19) was insufficient to fit a multivariate model.

In the sensitivity analysis, in which 539 missing HR-HPV values were recoded as HR-HPV negative, the overall prevalence of HR-HPV was 4.0% (95% CI = 3.0 to 5.2). The associations between HR-HPV and respondent characteristics were similar.

DISCUSSION

Prevalence of HR-HPV DNA in a representative sample of US females ages 57–85 was 6.0%, corresponding with 1.8 (95% CI = 1.4 to 2.4) million women, and is stable across older age subgroups. Risk factors in younger women are also significant correlates of HR-HPV presence in older women. Additional health-related correlates of HR-HPV positivity, not appreciated in younger populations, are identified. Among older women with genital HR-HPV, the vast majority exhibit multiple genotype infection.

Estimated HR-HPV prevalence for women ages 57–85 is nearly identical to that reported by the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) for women ages 50–59, using comparable methods (18). In a validation study including older women, high agreement was found (88.1%, κ=0.73), between physician and self-swab specimens for detecting HPV (30). The frequency of oncogenic HPV types 16 and 18 translates roughly to minimum population prevalences of 0.5 and 0.4%, respectively; no individual tested positive for both HPV types 16 and 18. These findings are very similar to the NHANES prevalence estimates for these genotypes among women ages 14–59, including the rare co-presence of types 16 and 18 (0.1%) (18).

Other US-based studies of HPV that include older women are limited by relatively small, clinical convenience samples and aggregation of women ages 60 and older. Age standardized estimates of HR-HPV in 1154 female patients, 16 years and older between 1989–90, were 4.2–4.9% using a PCR and DNA hybridization assay (31). A smaller study of 260 healthy postmenopausal women seeking gynecologic care during 1997–99 found a HR-HPV prevalence of 6% (32), using similar methods.

The frequency of multiple type infection found here is significantly higher than that observed among younger women with any genital HPV (18) or HR-HPV specifically (33). This may reflect cumulative lifetime exposure (34), an association between multiple type infection and vulnerability to persistence (35) or reactivation of latent infection (36), and/or a senescence-related reduction in capacity to suppress dormant virus or clear new infection (37). Longitudinal, population-based data are needed to elucidate mechanisms underlying the natural history of oncogenic HPV in older women. The implications of long-term carriage of genital tract HPV well beyond menopause are not well-understood; further work is needed to appreciate the implications in older women for vulvovaginal diseases, transmission to partners, Pap smear abnormalities, treatment decisions about gynecologic co-morbidities, and psychological well-being.

The prevalence of HR-HPV is higher in hysterectomized versus non-hysterectomized women, despite similar sexual behavior. Understanding the role of hysterectomy in the natural history of HR-HPV is complex, limited in this study by self-report, and should incorporate factors such as timing and type of hysterectomy, oophorectomy, indication for hysterectomy, and adjunctive treatment. In two studies, Castle et al. documented HR-HPV in younger women who had undergone hysterectomy, but found no difference in HPV prevalence by hysterectomy status (31, 38). One study suggests that persistent genital tract HPV infection in older women may be a marker of immune compromise (37). This may partially explain the relationship we find between hysterectomy and HR-HPV. We find that a history of any cancer, a higher number of cancers, and any current antineoplastic agent use were associated with a higher prevalence of HR-HPV and that women with hysterectomy were less healthy than women who did not have hysterectomy.

There were limitations to our study. Cervical dysplasia and sexually transmitted infection history are likely under-reported (39), thereby attenuating expected associations with HPV. Sexuality data were also self-reported; prior work with this dataset demonstrates high internal and external validity and low item non-response using valid interview methods(13, 40). Differences between vaginal swab non-responders and responders could bias prevalence estimates; however, in the extreme case where all non-responders are assumed to be HR-HPV negative, overall prevalence is still 4.0% (2.9% in the women age 75–85) and the same correlates are identified. In some subgroups, the very small number of participants with HR-HPV results in wide confidence intervals, which have been reported for completeness, but should be regarded with caution. Use of the self-collected specimens may lead to detection of different HPV types than those collected by direct endocervical sampling, and may favor detection of low risk types with predilection for the vagina (30),(18). The degree of vaginal atrophy may also influence HPV detection (27), as suggested in our study by a higher rate of detection in women with a longer duration since last menses. Also, collecting a vaginal specimen from a single time point does not distinguish between new, persistent, or reactivated latent infection. Furthermore, because the hc2 assay does not control for cellular adequacy, a small but unknown proportion may have been falsely negative.

HR-HPV prevalence was stable across older age groups and nearly equivalent to that estimated by NHANES for women in the 6th decade. The proportion of HPV types targeted by the HPV vaccine among older women with HR-HPV positivity was 27.2% (95% CI = 14.4 to 36.9), comparable to 1.2% (95% CI = 0.8 to 2.0) prevalence. Although an underestimate of the prevalence of vaccine types among all older women, this is in contrast to the estimated 3.4% prevalence among the general population of women ages 14–59(19). These data provide physicians and the public new information pertinent to HPV counseling, screening decisions, and health-related quality of life(41).

Acknowledgments

Financial support for the National Health, Social Life and Aging Project (NSHAP) and this manuscript comes from the National Institutes of Health, including the National Institute on Aging, the Office of Research on Women’s Health, the Office of AIDS Research, and the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (5R01AG021487). The NSHAP study is also supported by NORC, whose staff was responsible for the data collection. Donors of supplies to NSHAP include: Orasure, Sunbeam Corporation, A&D/LifeSource, Wilmer Eye Institute at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Schleicher & Schuell Bioscience, Biomerieux, Roche Diagnostics, Digene Corporation, Richard Williams.

The authors thank Megan Young, MD, for research assistance provided while a medical student working with Dr. Lindau. The authors also thank Jessica Schwartz, Syed Saad Iqbal, and Andreea Mihai for research assistance and help with preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: Dr. Jordan has a consulting agreement with Roche Diagnostics Corporation (Basel, Switzerland). The other authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Schiffman MH, Bauer HM, Hoover RN, Glass AG, Cadell DM, Rush BB, et al. Epidemiologic evidence showing that human papillomavirus infection causes most cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993 Jun 16;85(12):958–64. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.12.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bosch FX, Manos MM, Munoz N, Sherman M, Jansen AM, Peto J, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus in cervical cancer: a worldwide perspective. International biological study on cervical cancer (IBSCC) Study Group. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87(11):796–802. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.11.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ries L, Harkins D, Krapcho M, Mariotto A, Miller B, Feuer E, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2003, Table V-4, based on November 2005 SEER data submission. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Insinga RP, Dasbach EJ, Elbasha EH. Assessing the annual economic burden of preventing and treating anogenital human papillomavirus-related disease in the US: analytic framework and review of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics. 2005;23(11):1107–22. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200523110-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herrero R, Hildesheim A, Bratti C, Sherman ME, Hutchinson M, Morales J, et al. Population-based study of human papillomavirus infection and cervical neoplasia in rural Costa Rica. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000 Mar 15;92(6):464–74. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.6.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schiffman M, Kjaer SK. Chapter 2: Natural history of anogenital human papillomavirus infection and neoplasia. Journal of the National Cancer Institute Monographs. 2003;(31):14–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a003476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franceschi S, Herrero R, Clifford GM, Snijders PJ, Arslan A, Anh PT, et al. Variations in the age-specific curves of human papillomavirus prevalence in women worldwide. Int J Cancer. 2006;119(11):2677–84. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Sanjose S, Diaz M, Castellsague X, Clifford G, Bruni L, Munoz N, et al. Worldwide prevalence and genotype distribution of cervical human papillomavirus DNA in women with normal cytology: a meta-analysis. Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2007 Jul;7(7):453–9. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70158-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castle PE, Schiffman M, Herrero R, Hildesheim A, Rodriguez AC, Bratti MC, et al. A prospective study of age trends in cervical human papillomavirus acquisition and persistence in Guanacaste, Costa Rica. J Infect Dis. 2005 Jun 1;191(11):1808–16. doi: 10.1086/428779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franco EL, Villa LL, Sobrinho JP, Prado JM, Rousseau MC, Desy M, et al. Epidemiology of acquisition and clearance of cervical human papillomavirus infection in women from a high-risk area for cervical cancer. J Infect Dis. 1999;180(5):1415–23. doi: 10.1086/315086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown DR, Shew ML, Qadadri B, Neptune N, Vargas M, Tu W, et al. A longitudinal study of genital human papillomavirus infection in a cohort of closely followed adolescent women. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(2):182–92. doi: 10.1086/426867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.U. S. Census Bureau. “U. S. Interim Projections by Age, Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin,” Table 2a. 2004 [cited 2006 December 6]; Available from: http://www.census.gov/ipc/www/usinterimproj/

- 13.Lindau ST, Schumm P, Laumann EO, Levinson W, O’Muircheartaigh C, Waite LJ. Prevalence of Sexual Activity, Behaviors and Problems Among Older Adults in the United States: A National, Population-Based Study. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:762–74. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaccarella S, Herrero R, Snijders PJF, Dai M. Smoking and human papillomavirus infection: pooled analysis of the International Agency for Research on Cancer HPV Prevalence Surveys. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;37(2):1–11. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burchell A, Winer RL, De Sanjose S, Franco E. Chapter 6: Epidemiology and transmission dynamics of genital HPV infection. Vaccine. 2006 Aug 21;24(S3):S52–61. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merrill RM, Layman AB, Oderda G, Asche C. Risk estimates of hysterectomy and selected conditions commonly treated with hysterectomy. Annals of Epidemiology. 2008 Mar;18(3):253–60. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedman AL, Shepeard H. Exploring the knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and communication preferences of the general public regarding HPV: Findings from CDC focus group research and implications for practice. Health Education & Behavior. 2007 Jun;34(3):471–85. doi: 10.1177/1090198106292022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dunne EF, Unger ER, Sternberg M, McQuillan G, Swan DC, Patel SS, et al. Prevalence of HPV infection among females in the United States. Jama. 2007;297(8):813–19. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.8.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindau ST, Hoffman JN, Lundeen K, Jaszczak A, McClintock M, Jordan JA. Vaginal Self-Swab Specimen Collection in a Home-Based Survey of Older Women: Methods and Applications. 2007 doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbn021. Under Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor JO, Wallace RB, Ostfeld AM, Blazer DG. Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly, 1981–1993: [East Boston, Massachusetts, Iowa and Washington Counties, Iowa, New Haven, Connecticut, and North Central North Carolina]. Resource Data Book and Questionnaires, ICPSR 9915; 1994.

- 21.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1987;40(5):373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qato D, Schumm P, Johnson M, Lindau S. The National Social Life, Health and Aging Project Technical Report on Medication Coding. The University of Chicago and NORC 2008 [cited; Available from: http://biomarkers.uchicago.edu/pdfs/TR-PharmData.pdf

- 23.Lindau ST, Surawska, H., Schwartz, J., Jordan, J.A. Vaginal Swab Measurement of Human Papillomavirus in Wave I of the National Social Life Health & Aging Project (NSHAP). NORC and the University of Chicago 2008 [cited; Available from: http://biomarkers.uchicago.edu/pdfs/TR-HPV.pdf

- 24.Binder DA. On the variances of asymptotically normal estimators from complex surveys. International Statistical Review. 1983;51:279–92. [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Centers for Health Statistics Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1988–94) Analytic and reporting guidelines. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1996. NHANES II Reference manuals and reports (CD-ROM): http://wwwcdcgov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes3/nh3guipdf. [Google Scholar]

- 26.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 9. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Castle PE, Jeronimo J, Schiffman M, Herrero R, Rodriguez AC, Bratti MC, et al. Age-related changes of the cervix influence human papillomavirus type distribution. Cancer Res. 2006;66(2):1218–24. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Concato J, Feinstein AR, Holford TR. The Risk of Determining Risk with Multivariable Models. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1993 Feb 1;118(3):201–10. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-3-199302010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.U. S. Census Bureau. [Accessed June 27, 2007];Monthly Population Estimates by Age, Sex, Race and Hispanic Origin for the United States: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2006. 2007 http://www.census.gov/popest/national/asrh/2006_nat_ni.html.

- 30.Gravitt PE, Lacey JV, Jr, Brinton LA, Barnes WA, Kornegay JR, Greenberg MD, et al. Evaluation of self-collected cervicovaginal cell samples for human papillomavirus testing by polymerase chain reaction. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001 Feb;10(2):95–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Castle PE, Schiffman M, Glass AG, Rush BB, Scott DR, Wacholder S, et al. Human papillomavirus prevalence in women who have and have not undergone hysterectomies. J Infect Dis. 2006;194(12):1702–5. doi: 10.1086/509511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith EM, Ritchie JM, Levy BT, Zhang W, Wang D, Haugen TH, et al. Prevalence and persistence of human papillomavirus in postmenopausal age women. Cancer Detect Prev. 2003;27(6):472–80. doi: 10.1016/s0361-090x(03)00104-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clifford GM, Gallus S, Herrero R, Munoz N, Snijders PJ, Vaccarella S, et al. Worldwide distribution of human papillomavirus types in cytologically normal women in the International Agency for Research on Cancer HPV prevalence surveys: a pooled analysis. Lancet. 2005 Sep 17–23;366(9490):991–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67069-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herrero R, Castle PE, Schiffman M, Bratti MC, Hildesheim A, Morales J, et al. Epidemiologic profile of type-specific human papillomavirus infection and cervical neoplasia in Guanacaste, Costa Rica. J Infect Dis. 2005 Jun 1;191(11):1796–807. doi: 10.1086/428850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ho GY, Bierman R, Beardsley L, Chang CJ, Burk RD. Natural history of cervicovaginal papillomavirus infection in young women. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(7):423–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199802123380703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strickler HD, Burk RD, Fazzari M, Anastos K, Minkoff H, Massad LS, et al. Natural history and possible reactivation of human papillomavirus in human immunodeficiency virus-positive women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005 Apr 20;97(8):577–86. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garcia-Pineres AJ, Hildesheim A, Herrero R, Trivett M, Williams M, Atmetlla I, et al. Persistent human papillomavirus infection is associated with a generalized decrease in immune responsiveness in older women. Cancer Res. 2006 November 15;66(22):11070–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Castle PE, Schiffman M, Bratti MC, Hildesheim A, Herrero R, Hutchinson ML, et al. A population-based study of vaginal human papillomavirus infection in hysterectomized women. J Infect Dis. 2004 Aug 1;190(3):458–67. doi: 10.1086/421916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anderson JE, McCormick L, Fichtner R. Factors associated with self-reported STDs: data from a national survey. Sex Transm Dis. 1994;21(6):303–8. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199411000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fenton KA, Johnson AM, McManus S, Erens B. Measuring sexual behaviour: methodological challenges in survey research. Sex Transm Infect. 2001;77(2):84–92. doi: 10.1136/sti.77.2.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fleurence RL, Dixon JM, Milanova TF, Beusterien KM. Review of the economic and quality-of-life burden of cervical human papillomavirus disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(3):206–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]