Abstract

Experiments are presented that suggest DNA strands chemically immobilized on gold nanoparticle surfaces can engage in two types of hybridization, one that involves complementary strands and normal base pairing interactions and a second one assigned as a “slipping” interaction, which can additionally stabilize the aggregate structures through non-Watson Crick type base pairing or interactions less complementary than the primary interaction. The curvature of the particles appears to be a major factor that contributes to the formation of these “slipping” interactions as evidenced by the observation that flat gold triangular nanoprism conjugates of the same sequence do not support them. Finally, these “slipping” interactions significantly stabilize nanoparticle aggregate structures, leading to large increases in Tms and effective association constants as compared with free DNA and particles that do not have the appropriate sequence to maximize their contribution.

Main Text

Over the past decade, polyvalent oligonucleotide-gold nanoparticle conjugates (DNA-AuNPs) have become the focus of intense research.1–3 These structures exhibit properties that are often different from the properties of the nanoparticle and free-oligonucleotides from which they are derived,4,5 and from their monovalent analogues.6 They have been utilized in the development of novel materials assembly schemes,7–12 useful and, in certain cases, commercially viable detection systems,13–28 and intra-cellular gene regulation agents.29–31 Despite their extensive utility, however, there remain several fundamental questions pertaining to DNA hybridization with these polyvalent structures.

When two types of DNA-AuNPs, functionalized with complementary oligonucleotide sequences, are introduced in one solution, under the appropriate conditions, they will assemble into large polymeric amorphous or crystalline aggregates (Scheme 1A).1,7,8,32–34 This assembly is accompanied by a concomitant dampening and red-shifting of their surface plasmon resonance (SPR) band and a color change from red to blue. This process is reversible, and when heated, the DNA linkages holding the particles together dehybridize (melting of the DNA-AuNPs) in a highly cooperative manner resulting in a recovery of their original spectroscopic signatures and intense red color. These structures typically melt at temperatures higher than one would predict based upon the melting properties of the particle-free DNA.1,35,36

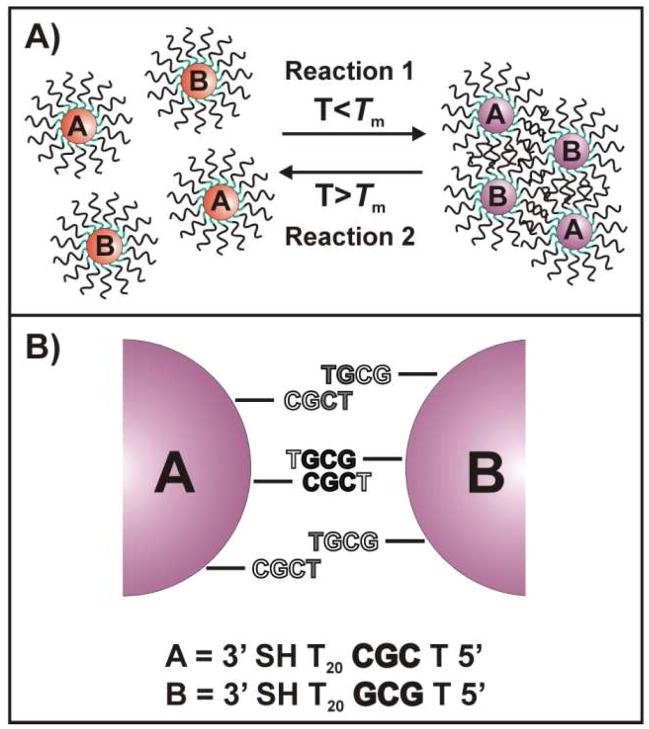

Scheme 1.

A) General scheme for the hybridization and melting of particles which are functionalized with complementary oligonucleotide sequences termed A and B. B) General scheme (in a ‘two-particle’ model) showing the potential interactions (normal and “slipping”) accessible for DNA-AuNPs functionalized with TCGC– (particle A) and TGCG– (particle B). The interactions possible for oligonucleotides on the particle surface depend on their ability to engage in hybridization with complementary strands on an adjacent particle and are impacted by the radius of curvature of the particles. Black lettering indicates bases involved in normal Watson-Crick interactions, gray lettering indicates bases involved in non-Watson-Crick “slipping” interactions, and white lettering indicates bases that are not involved in hybridization.

This unique behavior has been explained, in part, by the multivalent character of the particles and their ability to engage in multiple hybridization events, which lead to enhanced stability.36 However, the exact nature of the DNA base interactions contained within these structures has not been completely resolved. Herein, we describe experiments that suggest that these curved particles can engage in two types of hybridization, one that involves complementary strands and normal base pairing interactions and a second “slipping” interaction, which can stabilize the aggregate structures through non-Watson Crick type base pairing interactions (Scheme 1B). A “slipping” interaction in this case is defined as a secondary base pairing motif (not necessarily Watson Crick and partial complementarity) that contains fewer total base interactions than the primary and stronger interaction (normal Watson-Crick and full complementarity) of the system, while still imparting a measure of stability onto the nanoparticle aggregate systems.

Gold nanoparticles (60 nm in diameter, Ted Pella, Redding, CA) and triangular gold nanoprisms (~ 140 nm edge length)37 were functionalized with a series of 24-mer propyl thiol-modified oligonucleotides according to standard literature protocols with minor modifications.38–40 The gold nanoparticles and nanoprisms were salt stabilized to 1.0 and 0.15 M NaCl, respectively. The sequences used in this study were composed of: 1) a 3′ propyl thiol moiety, 2) a poly-T spacer, 3) a C and/or G -rich recognition element designed to access a particular set of “slipping” interactions, and 4) a single T capping base on the 5′ end designed to prevent undesired aggregation resulting from G-quartet formation (Table 1).41–43 Extremely short (1–3 base) recognition elements were used in order to limit and easily focus on the possible “slipping” interactions for each system. A poly-T spacer was used since this base has the weakest interaction with itself;44,45 DNA-AuNPs functionalized with the control sequence (Table 1) exhibit no hybridization or melting behavior under any of the conditions studied (Supporting Information, Figure S1).

Table 1.

DNA sequences.

| Name | Oligonucleotide Sequence |

|---|---|

| Control | 5′ – TTT TTT TTT TTT TTT TTT TTT TTT – (CH2)3 – SH-3′ |

| TGC- | 5′ – TGC TTT TTT TTT TTT TTT TTT TTT – (CH2)3 – SH-3′ |

| TCG- | 5′ – TCG TTT TTT TTT TTT TTT TTT TTT – (CH2)3 – SH-3′ |

| TCGC- | 5′ – TCG CTT TTT TTT TTT TTT TTT TTT – (CH2)3 – SH-3′ |

| TGCG- | 5′ – TGC GTT TTT TTT TTT TTT TTT TTT – (CH2)3 – SH-3′ |

Complementary DNA-AuNPs (A and B, Scheme 1A) were hybridized overnight at 4 °C. The melting transitions of the aggregates were recorded as the temperature of the solution was ramped from 4 to 95 °C (at 1 °C/min) with magnetic stirring. The temperature where the melting transition takes place (Tm) and the breadth of the transition (full width at half maximum, FWHM) provide information about the nature of the DNA interactions linking the DNA-AuNPs;46 stronger interactions typically lead to systems of aggregates with higher melting temperatures.47

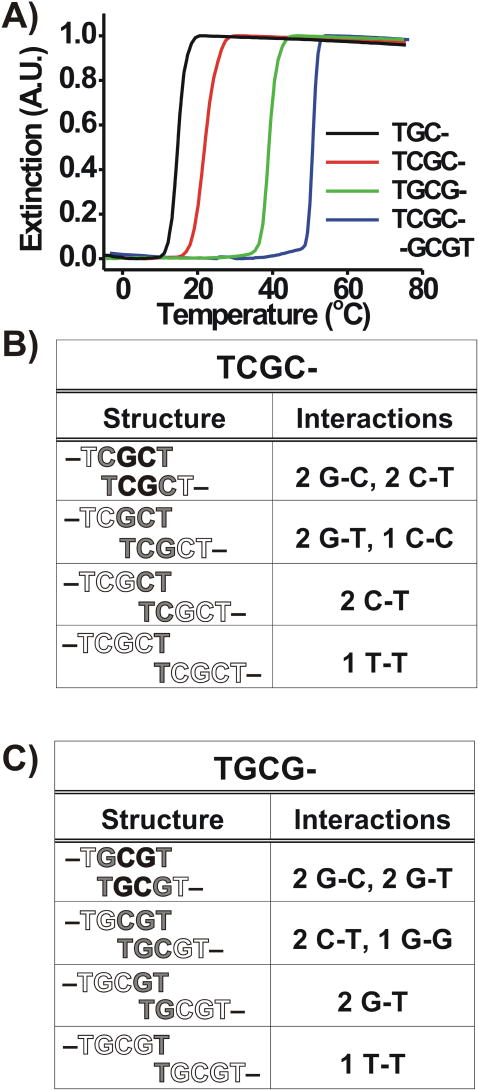

In our initial experiments, we investigated the hybridization/melting behavior of DNA-AuNPs functionalized with sequences containing 2 base pair recognition elements (i.e., A = B = TCG– and A = B = TGC–, Scheme 1A, Table 1). We chose these particular DNA-AuNP systems because each has the ability to access a combination of “slipping” interactions of different strengths (Figures 1B and 1C). For example, in a ‘two-particle’ version of the variable strength “slipping” model introduced above, we assume that the most favorable interaction, a complementary 2 base pair GC core, forms for both systems. If “slipping” is considered, both of these systems also can participate in G-T, C-T, and T-T interactions, while C-C and G-G interactions are limited to the TGC– and TCG– systems, respectively (Figure 1B and 1C). Among these non-Watson-Crick interactions, those involving a G base generally are stronger than the analogous interaction involving a C base, and both of these types of interactions are stronger than the interaction of T with itself (i.e., G-G > C-C > G-T > C-T > T-T).48,49 According to this analysis, we hypothesized that DNA-AuNPs functionalized with TGC– are capable of forming stronger overall hybridization interactions (normal plus “slipping”) in a nanoparticle aggregate than those functionalized with TCG–. We further hypothesized that, if “slipping” interactions contribute significantly to aggregate stability, an increased melting temperature should be observed for aggregates of DNA-AuNPs functionalized with TGC– as compared with aggregates formed from particles functionalized with TCG–. Indeed, we observe that the melting temperature of DNA-linked aggregates comprised of DNA-Au NPs functionalized with TGC– is 5.1 °C higher than those comprised of DNA-AuNPs functionalized with TCG– in 1.0 M NaCl, 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, 0.01 % SDS, pH 7.2 (i.e., Tm (TGC–) = 19.9 °C; Tm (TCG–) = 14.8 °C, Table 2, Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

A) Melting transitions (monitored at 520 nm) for aggregates of DNA-AuNPs functionalized with 2 base pair sequences (TCG– or TGC–). B) The “slipping” interactions possible in a ‘two-particle’ model for DNA-AuNPs functionalized with TCG–. C) The “slipping” interactions possible in a ‘two particle’ model for DNA-AuNPs functionalized with TGC–. In B) and C), black lettering indicates bases involved in normal Watson-Crick interactions, gray lettering indicates bases involved in non-Watson-Crick “slipping” interactions, and white lettering indicates bases that are not involved in hybridization. Similar melting behavior also was observed at 260 nm.

Table 2.

Thermodynamic values for Reaction 1 (Scheme 1A).

| Name | Tm (°C) | FWHM (°C) | Keq (4°C) | Keq (25°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCG- | 14.8 | 3.2 | 8.6 × 104 | 5.0 × 10−5 |

| TGC- | 19.9 | 5.1 | 1.5 × 105 | 2.7 × 10−2 |

| TCGC- | 22.0 | 5.1 | 5.0 × 105 | 1.3 × 10−1 |

| TGCG- | 39.5 | 3.4 | 1.1 × 1016 | 1.2 × 106 |

| TCGC--GCGT | 50.7 | 2.5 | 3.1 × 1036 | 4.7 × 1018 |

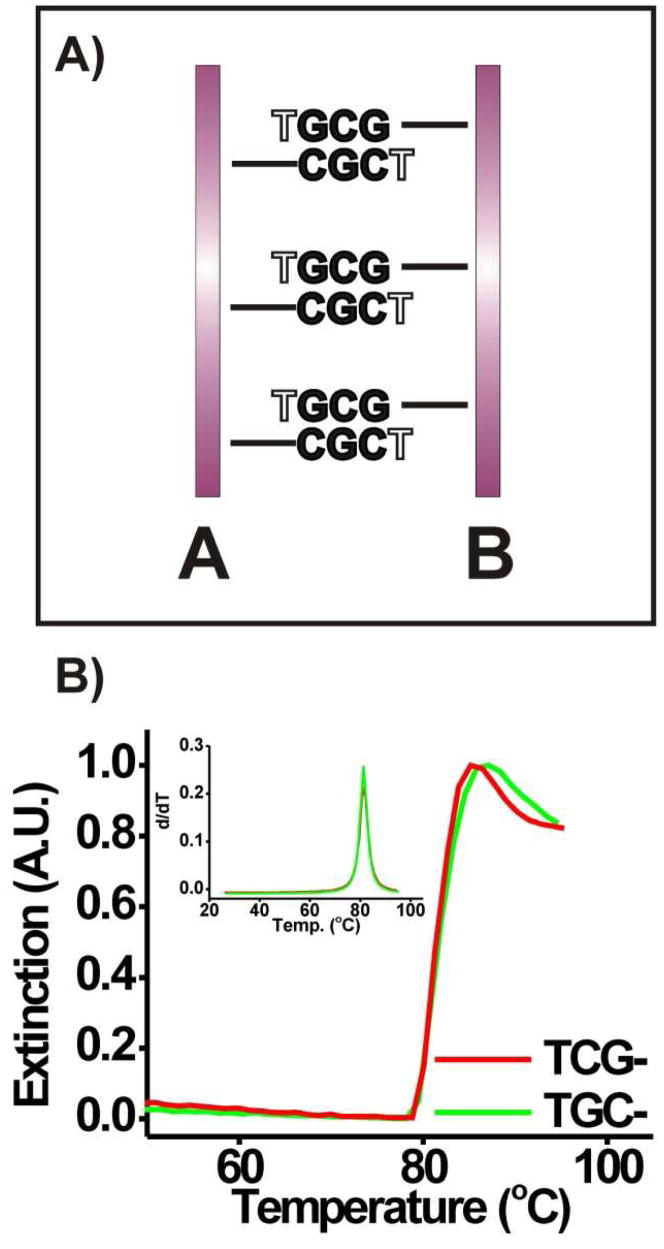

We also investigated the hybridization/melting behavior of systems of DNA-Au NPs functionalized with sequences containing a 3 base pair recognition element (i.e., A = B = TCGC– and A = B = TGCG–, Scheme 1A, Table 1). In these systems, we hypothesized, again using a ‘two-particle’ model and information about the relative strengths of DNA base pairing interactions,48,49 that DNA-AuNPs functionalized with TGCG– are capable of forming stronger overall interactions in an aggregate than those functionalized with TCGC– (Figure 2B and 2C). This enhanced stability again is evidenced by an increased melting temperature; we observe that the melting temperature of aggregates comprised of DNA-Au NPs functionalized with TGCG– is 17.5 °C higher than those comprised of DNA-Au NPs functionalized with TCGC– in 1.0 M NaCl, 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, 0.01 % SDS, pH 7.2 (i.e., Tm (TGCG–) = 39.5 °C; Tm (TCGC–) = 22.0 °C, Table 2, Figure 2A). In this case, it is possible for each system to form a 2 base pair duplex core, and this likely occurs since the Tm for each of these systems is higher than the Tm for the 2 base pair systems (Table 2, Figure 2A). In addition, the melting temperatures of both of these aggregate systems are lower than the fully complementary system with 3 base pairings in the recognition element (A = TCGC– and B = TGCG–, Table 2, Figure 2A). Ultimately, the differences in melting temperature that are observed for both the 2 and 3 base pair systems indicate that the “slipping” interactions of oligonucleotides attached to AuNPs lead to a significant increase in aggregate stability.

Figure 2.

A) Melting transitions (monitored at 520 nm) for aggregates of DNA-Au NPs functionalized with sequences containing 2 and 3 base pair recognition elements. B) The “slipping” interactions possible for a ‘two-particle’ model for DNA-AuNPs functionalized with TCGC–. C) The “slipping” interactions possible in a ‘two-particle’ model for DNA-AuNPs functionalized with TGCG–. In B) and C), black lettering indicates bases involved in normal Watson-Crick interactions, gray lettering indicates bases involved in non-Watson-Crick “slipping” interactions, and white lettering indicates bases that are not involved in hybridization. Similar melting behavior also was observed at 260 nm.

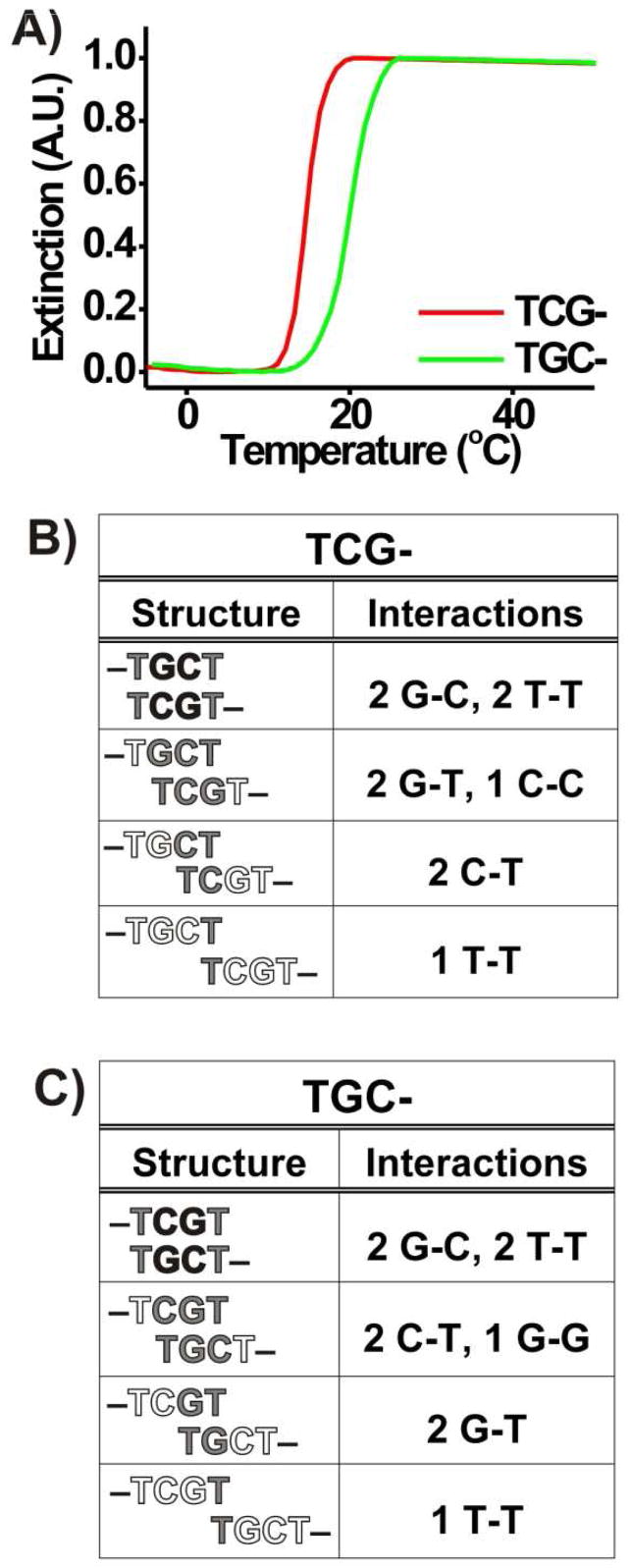

To further evaluate if the radius of curvature of the gold nanoparticles is responsible for the “slipping” interactions of the DNA bases we studied the hybridization and melting behavior of DNA functionalized triangular gold nanoprisms (DNA-Au prisms)37,39 in 0.15 M NaCl, 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, 0.01 % SDS, pH 7.2. We reasoned that the atomically flat surfaces of triangular gold nanoprisms would not foster DNA base “slipping” interactions (Figure 3A) and therefore differences in melting temperature would not be observed for, for example, aggregates of gold nanoprisms functionalized with TGC– and aggregates of those functionalized with TCG–. Aggregates of gold nanoprisms functionalized with TCG– or TGC– in fact had nearly identical melting profiles and melting temperatures (Tmprism (TCG–) = 81.4 °C or Tmprism (TGC–) = 81.5 °C (Figure 3B). This experiment indicates that the difference in Tm seen for aggregates of AuNPs functionalized with TCG– or TGC– (Figure 2A) is indeed due to the radius of curvature of the gold nanoparticle and the “slipping” interactions that occur as a result.

Figure 3.

A) Diagram (for a ‘two-particle’ model) showing that “slipping” interactions are not as likely with DNA functionalized-Au prisms (particle A is functionalized with TCGC–, while particle B is functionalized with TGCG–, prisms presented edge on). In contrast, note that, for the same DNA sequences immobilized on AuNPs, “slipping” interactions occur (Scheme 1B). Black lettering indicates bases involved in normal Watson-Crick interactions and white lettering indicates bases that are not involved in hybridization. B) Melting transitions (monitored at 260 nm) for aggregates of DNA-Au triangular prisms functionalized with sequences containing 2 base pair recognition elements (TCG– or TGC–). Similar melting behavior also was observed at 900 nm.

To gain further insight into the role of base pair “slipping” in nanoparticle aggregation, the thermodynamic parameters (ΔHtot, ΔG, ΔS, and Keq) were explored. It is possible to calculate the total enthalpy (ΔHtot) for an aggregate system by fitting the experimentally obtained melting profiles using the following equation:46

Where f is the fraction of the total aggregate in the dispersed state, R is the ideal gas constant in kcal/mol, T is the temperature in Kelvin (K) and Tm is the melting temperature of the nanoparticle aggregate. Since the equilibrium binding constant (Keq) equals:

the values of ΔHtot (fitted) and the Tm (measured) can be used to calculate Keq for a given temperature T. After determining the equilibrium binding constants for the given systems, we were able to calculate the change in Gibbs free energy (ΔG) of the system during the melting process:

Finally, the entropy (ΔS) of melting for the aggregated systems also can be determined at a given temperature, T. Selected results from these thermodynamic calculations are shown in Table 2 and a complete compilation of all the results is shown in Table S1 for all of the sequences tested.

Interesting insight into the system can be gained by analyzing these thermodynamic values (Table 2, Table S1). First, the equilibrium binding constants (Keq) obtained from the calculations (at 4 °C and 25 °C) accurately reflect the physical state (assembled or not) of the nanoparticles tested at these two temperatures (when T = Tm, Keq = 1; assembled, Keq > 1 or dispersed, Keq < 1, Table 2, Table S1). These equilibrium binding constants highlight the importance of the contributions from the base pair “slipping” interactions. In the most striking example, we find that the difference in Keq between systems of particles functionalized with TCGC– and those functionalized with TGCG– (which have the same type of normal hybridization interactions but different “slipping” interactions) is ~ 1 × 1011 calculated at 4 °C (Table 2, Table S1, Scheme 1A). Further, one can see that, at room temperature, particles functionalized with TCGC– are not expected to form an assembled structure (Keq < 1) while those functionalized with TGCG– will readily assemble (Keq > 1). In conclusion, we have presented experiments that suggest that DNA strands chemically immobilized on gold nanoparticle surfaces can engage in two types of hybridization, one that involves complementary strands and normal base pairing interactions and a second one assigned as a “slipping” interaction, which can stabilize the aggregate structures through non-Watson Crick type base pairing or less complementary interactions than the primary interaction. The curvature of the particles is a major factor that contributes to these slipping interactions. Indeed, they are not observed with flat gold nanoprism conjugates of the same sequence. Further, when comparing the melting temperatures of aggregates of AuNPs to that of aggregates of nanoprisms functionalized with the same DNA sequences, we observe that the melting temperatures are much higher in the case of the nanoprism systems (even at a much lower salt concentration, Figure 2A, Figure 3B). The melting temperature is higher in the nanoprism system in part because the nanoprisms can only engage in the fully complementary base pairing interactions (no “slipping,” Scheme 1B, Figure 3A) and have greater surface contact. Finally, we conclude that a hierarchy of binding strengths for a given set of complementary sequences or sequence functionalized structures can be defined where the overall stability of duplex strands (higher Tms and effective association constants) goes as: free duplex DNA < free DNA and complementary DNA attached to a flat substrate (i.e. DNA monolayer) < curved or highly faceted polyvalent NPs linked by complementary duplex DNA < polyvalent NPs with large flat terraces linked by complementary duplex DNA (i.e., nanoprisms).

Supplementary Material

Supporting information, including figures as mentioned in the text, are available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof. George C. Schatz for helpful discussions and Dr. Jill E. Millstone for assistance with nanoprism functionalization and melting experiments. C. A. M. acknowledges the NSF-NSEC, the AFOSR, and the NCI CCNE for support of this work. He also is grateful for a NIH Director’s Pioneer Award and a NSSEF Fellowship from the DoD. H. D. H. acknowledges the U. S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) for a Graduate Fellowship under the DHS Scholarship and Fellowship Program.

References

- 1.Mirkin CA, Letsinger RL, Mucic RC, Storhoff JJ. Nature. 1996;382:607–609. doi: 10.1038/382607a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niemeyer CM. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2001;40:4128–4158. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011119)40:22<4128::AID-ANIE4128>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Storhoff JJ, Mirkin CA. Chem Rev. 1999;99:1849–1862. doi: 10.1021/cr970071p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daniel MC, Astruc D. Chem Rev. 2004;104:293–346. doi: 10.1021/cr030698+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayat MA. Colloidal Gold: Principles, methods, and applications. Academic Press; San Diego: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alivisatos AP, Johnsson KP, Peng X, Wilson TE, Loweth CJ, Bruchez MP, Schultz PG. Nature. 1996;382:609–611. doi: 10.1038/382609a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park SY, Lytton-Jean AKR, Lee B, Weigand S, Schatz GC, Mirkin CA. Nature. 2008;451:553–556. doi: 10.1038/nature06508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nykypanchuk D, Maye MM, Lelie D, van der Gang O. Nature. 2008;451:549–552. doi: 10.1038/nature06560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niemeyer CM, Simon U. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2005:3641–3655. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dillenback LM, Goodrich GP, Keating CD. Nano Lett. 2006;6:16–23. doi: 10.1021/nl0508873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Witten KG, Bretschneider JC, Eckert T, Richtering W, Simon U. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2008;10:1870–1875. doi: 10.1039/b719762d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim AJ, Biancaniello PL, Crocker JC. Langmuir. 2006;22:1991–2001. doi: 10.1021/la0528955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Medley CD, Smith JE, Tang Z, Wu Y, Banrungsap S, Tan W. Anal Chem. 2008;80:1067–1072. doi: 10.1021/ac702037y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nam JM, Thaxton CS, Mirkin CA. Science. 2003;301:1884–1886. doi: 10.1126/science.1088755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu JW, Lu Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:6642–6643. doi: 10.1021/ja034775u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu JW, Lu Y. Anal Chem. 2004;76:1627–1632. doi: 10.1021/ac0351769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alivisatos P. Nature Biotech. 2004;22:47–52. doi: 10.1038/nbt927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang CC, Huang YF, Cao ZH, Tan WH, Chang HT. Anal Chem. 2005;77:5735–5741. doi: 10.1021/ac050957q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee JS, Han MS, Mirkin CA. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:4093–4096. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han MS, Lytton-Jean AKR, Oh BK, Heo J, Mirkin CA. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:1807–1810. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosi NL, Mirkin CA. Chem Rev. 2005;105:1547–1562. doi: 10.1021/cr030067f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Storhoff JJ, Marla SS, Bao YP, Hagenow S, Mehta H, Lucas A, Garimella V, Patno T, Buckingham W, Cork W, Muller UR. Biosens Bioelectron. 2004;19:875–883. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2003.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Storhoff JJ, Lucas AD, Garimella V, Bao YP, Muller UR. Nature Biotech. 2004;22:883–887. doi: 10.1038/nbt977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taton TA, Mirkin CA, Letsinger RL. Science. 2000;289:1757–1760. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5485.1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katz E, Willner I. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:6042–6108. doi: 10.1002/anie.200400651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niemeyer CM, Ceyhan B, Hazarika P. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2003;42:5766–5770. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maxwell DJ, Taylor JR, Nie S. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:9606–9612. doi: 10.1021/ja025814p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dai Q, Liu X, Coutts J, Austin L, Huo Q. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:8138–8139. doi: 10.1021/ja801947e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giljohann DA, Seferos DS, Patel PC, Millstone JE, Rosi NL, Mirkin CA. Nano Lett. 2007;7:3818–3821. doi: 10.1021/nl072471q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosi NL, Giljohann DA, Thaxton CS, Lytton-Jean AKR, Han MS, Mirkin CA. Science. 2006;312:1027–1030. doi: 10.1126/science.1125559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seferos DS, Giljohann DA, Rosi NL, Mirkin CA. ChemBioChem. 2007;8:1230–1232. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hill HD, Macfarlane RJ, Senesi AJ, Lee B, Park SY, Mirkin CA. Nano Lett. 2008;8:2341–2344. doi: 10.1021/nl8011787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Storhoff JJ, Lazarides AA, Mucic RC, Mirkin CA, Letsinger RL, Schatz GC. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:4640–4650. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reynolds RA, III, Mirkin CA, Letsinger RL. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:3795–3796. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elghanian R, Storhoff JJ, Mucic RC, Letsinger RL, Mirkin CA. Science. 1997;277:1078–1081. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5329.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hurst SJ, Hill HD, Mirkin CA. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:12192–12200. doi: 10.1021/ja804266j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Millstone JE, Park S, Shuford KL, Qin L, Schatz GC, Mirkin CA. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:5312–5313. doi: 10.1021/ja043245a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hurst SJ, Lytton-Jean AKR, Mirkin CA. Anal Chem. 2006;78:8313–8318. doi: 10.1021/ac0613582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Millstone JE, Georganopoulou DG, Xu X, Wei W, Li S, Mirkin CA. Small. 2008 doi: 10.1002/smll.200800931. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Demers LM, Mirkin CA, Mucic RC, Reynolds RA, III, Letsinger RL, Elghanian R, Viswanadham G. Anal Chem. 2000:5535–5541. doi: 10.1021/ac0006627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li Z, Mirkin CA. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:1170–1178. doi: 10.1021/ja046931i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seela F, Jawalekar AM, Anup M, Chi L, Zhong D. Chem Biodivers. 2005;2:84–91. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200490168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu ZS, Guo MM, Shen GL, Yu RQ. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2007;387:2623–2626. doi: 10.1007/s00216-007-1126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saenger W. Principles of Nucleic Acid Structure. Springer-Verlag; New York, NY: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bloomfield VA, Crothers DMI, Tinoco J. Nucleic Acids: Structures, Properties, and Functions. University Science Books; Sausalito, CA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jin R, Wu G, Mirkin CA, Schatz GC. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:1643–1654. doi: 10.1021/ja021096v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lytton-Jean AKR, Mirkin CA. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:12754–12755. doi: 10.1021/ja052255o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kabeláè M, Hobza P. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2007;9:903–917. doi: 10.1039/b614420a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pranta J, Wierschke SG, Jorgensen WL. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:2810–2819. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information, including figures as mentioned in the text, are available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.