Abstract

Background

This study compares the efficacy of three types of reminders in promoting annual repeat mammography screening.

Design

RCT.

Setting and participants

Study recruitment occurred in 2004–2005. Participants were recruited through the North Carolina State Health Plan for Teachers and State Employees. All were aged 40–75 years and had a screening mammogram prior to study enrollment. A total of 3547 women completed baseline telephone interviews.

Intervention

Prior to study recruitment, women were assigned randomly to one of three reminder groups: (1) printed enhanced usual care reminders (EUCRs); (2) automated telephone reminders (ATRs) identical in content to EUCRs; or (3) enhanced letter reminders that included additional information guided by behavioral theory. Interventions were delivered 2–3 months prior to women’s mammography due dates.

Main outcome measures

Repeat mammography adherence, defined as having a mammogram no sooner than 10 months and no later than 14 months after the enrollment mammogram.

Results

Each intervention produced adherence proportions that ranged from 72% to 76%. Post-intervention adherence rates increased by an absolute 17.8% from baseline. Women assigned to ATRs were significantly more likely to have had mammograms than women assigned to EUCRs (p=0.014). Comparisons of reminder efficacy did not vary across key subgroups.

Conclusions

Although all reminders were effective in promoting repeat mammography adherence, ATRs were the most effective and lowest in cost. Health organizations should consider using ATRs to maximize proportions of members who receive mammograms at annual intervals.

Introduction

Breast cancer is a major public health concern. The American Cancer Society (ACS) projects about 182,000 new breast cancer cases and 40,000 breast cancer deaths in 2008.1 Mammography is the most effective method to detect breast cancers early, when they are smaller and potentially more treatable. Routine mammography screening reduces breast cancer mortality among women aged 40–74 years.2–4 Although most major medical organizations advise regular mammograms for women aged ≥40 years, they differ on the recommended interval between screenings. The research reported here is consistent with the ACS recommendation5 for annual mammography screening for women aged ≥40 years and is supported by research showing that annual, rather than biennial, screening may be optimal.6–9

Widespread adoption of mammography in the U.S. is a public health success. About 66% of U.S. women now report having mammograms in the past 1–2 years (referred to as recent mammography).10,11 However, there are areas of concern. The proportion of women with recent mammograms is slightly lower than previous assessments, signaling that mammography use may be in decline. Also, most women do not get regular mammograms at recommended intervals, referred to as repeat mammography. Receipt of repeat mammograms is crucial to achieving population-level reductions in breast cancer morbidity and mortality.12 The average repeat mammography rate (defined here as receipt of two consecutive mammograms on an annual interval) has been found to be only 38%.13 More extensive use of reminder systems might help to increase the proportion of women who get repeat mammograms.

Reminders typically are printed messages advising women that they are due for mammograms. An extensive literature documents the effectiveness of reminders in increasing mammography use14–20 and shows that these effects generally apply across diverse population groups.21,22 Fewer studies have tested the effect of reminders on repeat mammography use.15–18,21,23,24 Women who received printed reminders in one study15 had greater adherence to repeat mammography screening compared to women who received no intervention. Another study16 showed that mammography facilities using reminder systems had higher rates of repeat mammography adherence compared to facilities that did not use reminders. Studies17,18 have also found that simple printed reminders are as effective as more complex interventions. Results of these studies suggest that simple reminders can be powerful tools for promoting repeat mammography adherence.

Automated telephone reminders (ATRs) are a potentially promising strategy to increase repeat mammography adherence. Although they have received little attention for cancer screening,25,26 ATRs are effective for promoting health behaviors such as immunization27–29 and medication adherence.30,31 Automated telephone reminders may be a desirable communication channel for several reasons. They can potentially reach large numbers of people at relatively low cost, can be delivered at times convenient for intended recipients, and can be customized by content or language preference. Although no previously published study has compared the efficacy of ATRs to printed reminders on mammography adherence, one study32 found that reminder telephone calls made by office staff were more effective than printed reminders for promoting mammography use, but they have also been shown to be less cost effective.33

Analyses are from Personally Relevant Information on Screening Mammography (PRISM), a 4-year, randomized intervention trial funded by NIH. The overarching aim of PRISM is to find the minimal intervention needed for sustained annual-interval mammography use among a population of insured women. That is, although some women may need only to be reminded to have mammograms, others may have barriers that require more intensive interventions. Novel aspects of the current study are that it tested effects of manipulating message content and channel on repeat mammography adherence.

The specific aims of the current report were to: (1) assess change in annual repeat mammography adherence rates before and after delivery of interventions; (2) compare the efficacy of enhanced letter reminders (ELRs) to enhanced usual care reminders (EUCRs; manipulating reminder content); and (3) compare the efficacy of ATRs to EUCRs (manipulating reminder channel). A nonintervention control group was not included in PRISM for ethical reasons and because a large body of research documents the efficacy of reminders compared to nonintervention controls. A secondary aim was to test whether comparisons of reminder efficacy varied by population subgroup.

Methods

Study Overview

Researchers identified potential PRISM participants through the North Carolina State Health Plan (SHP) for Teachers and State Employees. Eligible participants had a previous mammogram within a specified window and were due for their next mammogram. Those who consented to participate (n=3547) completed baseline telephone interviews and were re-contacted at 12, 24, 36, and 42 months for follow-up interviews. They also agreed to participate in various interventions over the course of the study.

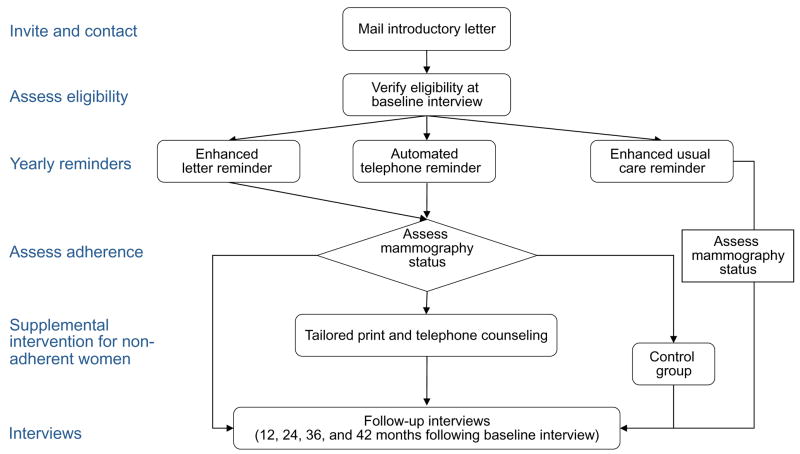

The PRISM interventions encouraged women to get annual mammograms using a stepped intervention design (Figure 1). The first round of intervention consisted of one of three reminder types delivered about 3 months prior to mammography due dates. Women who became overdue for their mammograms received supplemental interventions consisting of printed materials and telephone counseling tailored to address individuals’ barriers to mammography use. This report focuses on the efficacy of reminders only after the first year of delivery and not on subsequent interventions. The outcome for these analyses is repeat mammography adherence, defined as receipt of a subsequent mammogram within 10–14 months of the enrollment mammogram. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Public Health–Nursing IRB and the Duke University Medical Center approved the study (initial approval was granted in 2003 and 2004, respectively, and renewed annually).

Figure 1.

PRISM study design

Study Eligibility and Randomization

Researchers calculated target study enrollment as approximately 3545 participants to provide 80% power to detect a 6% difference in effect among intervention arms, with alpha 0.05 and two-tailed tests. The projected 6% effect size was based on outcomes found in prior research.

Researchers identified 9087 SHP members initially eligible for study participation. Those eligible were women residents of North Carolina aged 40–75 years; were enrolled with the SHP for ≥2 years; had their last screening mammograms (enrollment mammograms) between September 2003 and September 2004 (to ensure all had recent mammograms upon study entry); and had only one mammogram in the designated timeframe (to exclude those who had diagnostic mammograms).

Prior to recruitment, 9087 eligible participants were pre-randomized to one of three reminder groups: EUCR, ATR, or ELR. Descriptions of reminders are provided below. Researchers allocated 25% of eligible participants to EUCR and the remaining 75% to ATR (37.5%) and ELR (37.5%). The study design allocated larger proportions of women to ATR and ELR than to EUCR so that sample sizes would be sufficient for future analyses assessing efficacy of supplemental interventions.

Recruitment and Data Collection

Study recruitment for PRISM occurred between October 2004 and April 2005. Researchers first sent invitation letters to all potential participants who met initial eligibility criteria (n=9087). Letters included required Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule information and instructions for opting out of the study. Trained telephone interviewers made up to 12 attempts to obtain consent from potential participants to maximize the opportunity for contact. Women completed 30-minute baseline telephone interviews and provided sociodemographic and general health information and data about mammography beliefs, practices, and related variables.

The PRISM Interventions

Enhanced usual care reminders

Intervention characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The PRISM researchers created a usual care reminder because the SHP did not provide routine reminders. It is referred to here as an EUCR because it represents our best judgment of what a reminder should include at a minimum. The EUCRs, delivered as mailed letters, included dates of women’s last mammograms; information about benefits of mammography (Mammography is the key to finding breast cancers early); recommended guidelines (Most doctors agree that women aged 40 and older need mammograms once a year); contact information for the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Information Service; and SHP coverage.

Table 1.

Contents of intervention materials

| Component | Enhanced usual care reminder | Automated telephone reminder | Enhanced letter reminder |

|---|---|---|---|

| Date of last mammogram | X | X | X |

| Facility name and telephone number | NC | NC | X |

| Benefits of mammography | X | X | X |

| Recommended guidelines | X | X | X |

| State Health Plan coveragea | X | X | X |

| Cancer Information Service contact information | X | X | X |

| Breast cancer severity | NC | NC | X |

| Breast cancer susceptibility | NC | NC | X |

| Word count (approximate) | 224 | 224 | 352 |

Note: X denotes items covered in intervention materials; NC denotes items not covered in intervention materials.

Coverage differed for women in their forties vs women aged ≥50 years at the time of intervention delivery.

Automated telephone reminders

The ATRs contained the same content as the EUCRs but were delivered as automated telephone calls by TeleVox Software, Inc. Automated messages used a real woman’s voice because some research suggests that this form is more persuasive than computer-synthesized speech.34 Call attempts were terminated after a 2-week call window or ten unsuccessful call attempts to reach intended recipients. Automated messages instructed the listener to “press 1” if the call had reached the intended recipient, and they were not left on answering machines. Researchers classified women who listened to ≥20 seconds of the 69-second message as successful call attempts, because key message content (due for a mammogram) was delivered during this time. Successfully delivered ATRs required an average of three call attempts.

Enhanced letter reminders

Reminder efficacy potentially can be increased by incorporating persuasive content informed by behavioral theory.35–37 The Health Belief Model38 is a commonly used framework for informing mammography interventions.18,39,40 Key tenets of the Health Belief Model as they relate to mammography screening are that women must feel susceptible to breast cancer, perceive breast cancer as a serious disease, understand the benefits of getting regular mammograms, and receive cues to obtain mammograms.

The ELRs contained the same information as the other two reminders with several additions. The mailed ELR was a full-color, four-page booklet with a quilt graphic on the cover. The ELRs included additional text, informed by the Health Belief Model, about the severity of breast cancer (Each year, nearly 6,000 women in North Carolina will learn they have breast cancer, and about 1,100 North Carolina women will die from breast cancer) and breast cancer susceptibility (As women get older, their chances of getting breast cancer increase). The ELRs also included names and telephone numbers for the facility where recipients had their last mammograms, and stickers to remind women to make and keep their mammogram appointments. People Designs, Inc. in Durham NC produced both the EUCRs and ELRs.

Measures

Repeat Mammography Adherence

Researchers defined the outcome, repeat mammography adherence, as having a mammogram no sooner than 10 months and no later than 14 months after the enrollment mammogram. The 10-month boundary excludes mammograms that probably were diagnostic, and the 14-month boundary provides a 2-month window for scheduling. Mammograms occurring within 10 months of the enrollment mammogram were excluded from analysis (n=21). A series of algorithms was used to assess the outcome using both self-report and health claims data. Women who completed follow-up interviews were asked to confirm dates of both their recent and previous mammograms provided by claims data. Ninety-one percent of baseline participants (n=3211) completed 12-month follow-up interviews. If a discrepancy between self-report data and claims data occurred, self-report data were used, because it often took several months for mammograms to appear in health claims records. Discrepancies between claims data and self-reported information were estimated to have occurred for <10% of mammograms. Previous research confirms that self-reports are valid measures of recent mammography use.41–43

Because PRISM collected information on participants’ previous mammography histories, the study assessed whether women were adherent to repeat mammography prior to study enrollment (referred to as pre-intervention repeat mammography adherence). This measure assessed timing of the two most recent mammograms occurring prior to baseline interviews. Women who had these mammograms within the designated 10- to 14-month window were classified as adherent prior to study enrollment.

Sociodemographic and Healthcare Items

Interviewers asked questions at baseline to assess standard sociodemographics, including race/ethnicity, age, education, perceived financial status, marital status, work status, number living in household, and health status. Researchers categorized race/ethnicity as white or black. Age was categorized as 40–49 years or 50–75 years to reflect differences in mammography health insurance coverage by age group at the time of baseline data collection. Perceived financial status was assessed with the item: Without giving exact dollars, how would you describe your household’s financial situation right now? Responses were dichotomized as either no financial hardship or some financial hardship. One item assessed health status: How would you describe your current health? Responses were categorized as excellent/good or fair/poor. Study items also assessed whether women had received physician recommendations for mammograms in the past year, if they had a usual source of medical care, if they ever had an abnormal result on a mammogram that was not cancer, and if they had received reminders from their doctors or mammography facilities in the year prior to study enrollment.

Data Analysis

Analyses were conducted (completed in 2008) using SAS version 9.1. Tests were two-sided at p<0.05. Chi-square analyses tested for differences on sociodemographic and healthcare-related variables by reminder type at baseline and assessed change in repeat mammography adherence rates pre- and post-intervention. To assess the influence of reminder type on the outcome, the bivariate association between reminder type and repeat mammography adherence was tested. The efficacy of ATR and ELR compared to EUCR was examined using multivariable logistic regression analyses. Candidate variables were those associated with the outcome at the bivariate level of p≤0.05. Assignments to ATR and ELR were treated as dummy variables. Multivariable analyses produced ORs adjusted for other variables in the model, and 95% CIs. The likelihood ratio test was used to determine whether inclusion of interaction terms with race, marital status, household number, health status, work status, and pre-intervention repeat mammography adherence improved model fit.44

Results

Study Response and Sample Characteristics

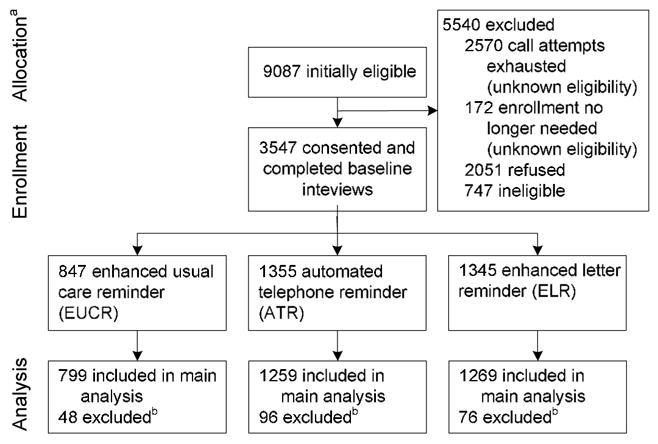

Of 9087 women initially eligible for recruitment (Figure 2), 3547 completed baseline telephone interviews; 2051 refused to participate; and 747 were classified as ineligible because they did not meet additional study requirements (working telephone, previous mammography dates inside the range of eligible dates, or no breast cancer history). The remaining 2742 women were classified as being of unknown eligibility either because call attempts were exhausted (n=2570) or their enrollment was no longer needed (n=172) to reach the target sample size. The range in response rates based on the American Association for Public Opinion Research Standard Definitions45 was 47%–64%. The lower response rate excludes a portion of those with unknown eligibility from response rate computation; the higher response rate excludes all those with unknown eligibility. Indirect assessment of differential nonresponse by race (methods are discussed elsewhere46) showed that there may have been a slightly lower response rate for black women.

Figure 2.

PRISM participant recruitment and randomization

aRandom allocation to study arms occurred prior to participant contact and recruitment. Larger numbers for the ATR and ELR groups were planned for future analysis of supplemental intervention.

bParticipants excluded from main analysis are: (1) those with self-reported race other than white or black (EUCR=7, ATR=24, ELR=22); (2) those who received subsequent mammograms ≤10 months after enrollment mammograms (EUCR=3, ATR=9, ELR=9), and/or those who received previous mammograms ≤10 months prior to enrollment mammograms (EUCR=38, ATR=63, ELR=45).

Of 3547 women who participated, 847 (23.9%) were in the EUCR group; 1355 (38.2%) were in the ATR group; and 1345 (37.9%) were in the ELR group. Because women were randomized prior to recruitment, proportions of actual participants in each study arm differed slightly from proportions described in the study design.

The final analytic sample contained 3327 participants. Analyses were intent-to-treat and included all study participants (n=3547) minus women who had subsequent mammograms within 10 months of their enrollment mammogram (n=21); had prior mammograms within 10 months of their enrollment mammograms (n=146); or self-reported their race as something other than white or black (n=53). Numbers for these racial/ethnic groups were too small for meaningful analyses. Intervention groups did not significantly differ on sociodemographic and healthcare variables at baseline interviews (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Personally Relevant Information on Screening Mammography (PRISM) sample, n (%) unless otherwise specified

| Enhanced usual care reminder (n=847) |

Automated telephone reminder (n=1355) |

Enhanced letter reminder (n=1345) |

Total (n=3547) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.167 | ||||

| 40–49 | 176 (20.8) | 305 (22.5) | 263 (19.6) | 744 (21.0) | |

| 50–74 | 671 (79.2) | 1050 (77.5) | 1082 (80.5) | 2803 (79.0) | |

| Race | 0.163 | ||||

| White | 757 (89.4) | 1183 (87.3) | 1179 (87.8) | 3119 (87.9) | |

| Black | 83 (9.8) | 148 (10.9) | 144 (10.7) | 375 (10.6) | |

| Asian | 0 (0.0) | 5 (0.4) | 6 (0.4) | 11 (0.3) | |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.07) | 1 (0.03) | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 4 (0.5) | 16 (1.2) | 13 (1.0) | 33 (0.9) | |

| Refused or self-reported as“other” | 3 (0.4) | 3 (0.2) | 2 (0.1) | 8 (0.2) | |

| Marital status | 0.393 | ||||

| Married | 681 (80.6) | 1075 (79.3) | 1095 (81.4) | 2851 (80.4) | |

| Not married (divorced, separated, widowed, never married) | 164 (19.4) | 280 (20.7) | 250 (18.6) | 694 (19.6) | |

| Education | 0.300 | ||||

| ≤High school | 130 (15.4) | 241 (17.8) | 210 (15.6) | 581 (16.4) | |

| Some college | 191 (22.6) | 267 (19.7) | 287 (21.3) | 745 (21.0) | |

| ≥College | 526 (62.1) | 845 (62.5) | 848 (63.0) | 2219 (62.6) | |

| Perceived financial status | 0.376 | ||||

| No financial hardship | 538 (64.2) | 838 (62.3) | 864 (64.8) | 2240 (63.7) | |

| Some financial hardship | 300 (35.8) | 508 (37.7) | 470 (35.2) | 1278 (37.3) | |

| Number of additional household members | 0.631 | ||||

| None | 105 (12.4) | 145 (10.7) | 143 (10.6) | 393 (11.1) | |

| 1 | 440 (52.0) | 717 (53.0) | 719 (53.5) | 1876 (52.9) | |

| 2 | 150 (17.7) | 246 (18.2) | 261 (19.4) | 657 (18.5) | |

| 3 | 104 (12.3) | 179 (13.2) | 148 (11.0) | 431 (12.2) | |

| ≥4 | 48 (5.7) | 68 (5.0) | 74 (5.5) | 190 (5.4) | |

| Work for pay | 680 (80.3) | 1061 (78.3) | 1041 (77.4) | 2782 (78.4) | 0.275 |

| Hours of work | 0.634 | ||||

| Daytime | 590 (86.8) | 920 (86.7) | 915 (88.0) | 2425 (87.2) | |

| Non-daytime (evening, night, rotating) | 90 (13.2) | 141 (13.3) | 125 (12.0) | 356 (12.8) | |

| Health status | 0.220 | ||||

| Excellent or good | 763 (90.3) | 1242 (91.9) | 1211 (90.0) | 3216 (90.8) | |

| Fair or poor | 82 (9.7) | 110 (8.1) | 134 (10.0) | 326 (9.2) | |

| Ever had an abnormal mammogram | 419 (49.5) | 632 (47.0) | 616 (45.5) | 1667 (47.0) | 0.186 |

| Have a regular doctor | 823 (97.2) | 1305 (96.3) | 1286 (95.6) | 3414 (96.3) | 0.174 |

| Doctor or provider advised mammogram in the past year | 666 (78.7) | 1072 (79.5) | 1046 (66.9) | 2784 (78.7) | 0.605 |

| Received reminder from doctor, health plan, or mammography facility in the past year | 448 (53.7) | 715 (53.8) | 730 (55.2) | 1893 (54.3) | 0.711 |

| Non-adherent to repeat mammography pre-interventiona | 340 (42.5) | 546 (43.2) | 559 (43.8) | 1445 (43.3) | 0.829 |

Total for category differs because participants who had mammograms within 10 months of enrollment mammogram were excluded from analyses

Intervention Efficacy

Each of the three reminders produced significant proportions of women adherent to repeat mammography after intervention delivery (Table 3). Overall, 74.5% of women (n=2479) were adherent to repeat mammography after intervention delivery compared to 56.7% (n=1887) prior to intervention delivery, an absolute increase of 17.8% (p<0.0001).

Table 3.

Adherence to annual repeat mammography pre- and post-intervention (n=3327), n (%) unless otherwise specified

| Adherent to repeat mammography pre-intervention | Adherent to repeat mammography post-intervention | Absolute change | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enhanced usual care reminder | 460 (57.6) | 574 (71.8) | 114 (14.2) | <0.0001 |

| Automated telephone reminder | 715 (56.8) | 960 (76.3) | 245 (19.5) | <0.0001 |

| Enhanced letter Reminder | 712 (56.1) | 945 (74.5) | 233 (18.4) | <0.0001 |

| Total | 1887 (56.7) | 2479 (74.5) | 592 (17.8) | <0.0001 |

The bivariate association between intervention arm (EUCR, ELR, ATR) and repeat mammography adherence rates was significant (Χ2=6.43, p=0.04). Repeat mammography adherence rates were 71.8% for EUCR, 74.5% for ELR, and 76.3% for ATR. After adjusting for other variables in the model (Table 4), women randomized to ATR were significantly more likely to have been adherent to repeat mammography than women randomized to EUCR (AOR=1.32 [95% CI=1.06, 1.64]), reflecting an absolute difference of 4.5%. Women randomized to ELR had adherence rates similar to women randomized to EUCR. Differences between these groups were not significant (AOR=1.19 [95% CI=0.96, 1.48]). The log-likelihood statistic was not significant at p<0.05, indicating that inclusion of interaction terms did not improve model fit.

Table 4.

Multivariable analyses of factors associated with repeat mammography adherence

| Variable | AOR (95% CI) | % adherent | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention group | |||

| Enhanced usual care reminder | ref | 71.8 | |

| Automated telephone reminder | 1.32 (1.06, 1.64) | 76.3 | 0.014 |

| Enhanced letter reminder | 1.19 (0.96, 1.48) | 74.5 | 0.117 |

| Race | |||

| Black | ref | 66.2 | |

| White | 1.31 (1.01, 1.70) | 75.2 | 0.042 |

| Perceived financial status | |||

| No financial hardship | 1.32 (1.11, 1.58) | 77.8 | 0.002 |

| Some financial hardship | ref | 68.0 | |

| Age (years) | |||

| 40–49 | ref | 61.9 | |

| 50–74 | 1.38 (1.11, 1.71) | 77.4 | 0.004 |

| Work for pay | |||

| Yes | 0.90 (0.72, 1.13) | 72.8 | 0.37 |

| No | ref | 79.4 | |

| Number of additional household members | 0.21 | ||

| ≥4 | 0.81 (0.52, 1.24) | 61.2 | |

| 3 | 0.92 (0.65, 1.31) | 67.5 | |

| 2 | 0.77 (0.56, 1.06) | 70.6 | |

| 1 | 1.0 (0.75, 1.33) | 77.9 | |

| None | ref | 75.3 | |

| Pre-intervention adherence to repeat mammography | |||

| Non-adherent | ref | 58.5 | |

| Adherent | 4.12 (3.45, 4.92) | 86.8 | <0.0001 |

| Health status | |||

| Fair or poor | ref | 64.9 | |

| Excellent or good | 1.59 (1.21, 2.10) | 75.1 | 0.001 |

| Received reminder from doctor, health plan, or mammography facility in the past year | |||

| Yes | 1.12 (0.94, 1.32) | 76.7 | 0.21 |

| No | ref | 71.1 | |

| Ever had an abnormal mammogram | |||

| Yes | 1.14 (0.96, 1.35) | 76.7 | 0.14 |

| No | ref | 72.0 |

Other variables were associated with repeat mammography adherence in the multivariable model (Table 4). White women (AOR=1.34 [95% CI=1.03, 1.74]); those who reported no financial hardship (AOR=1.32 [95% CI=1.11, 1.58]); those aged 50–75 years (AOR=1.38 [95% CI=1.11, 1.71]); and those who reported excellent or good health (AOR=1.59 [95% CI=1.21, 2.10]) were more likely to have been adherent to repeat mammography. Women adherent to repeat mammography prior to study enrollment were much more likely to be adherent after intervention delivery (AOR=4.12 [95% CI=3.45, 4.92]).

Cost Analyses

Reminder costs were estimated in the context of fully scaled dissemination within a large health organization. Assuming delivery for 500,000 members, the estimated cost per intended recipient was $0.86 for EUCR, $0.35 for ATR, and $1.34 for ELR. Cost estimates excluded research and development costs (e.g., overhead, administration of telephone interviews) because they would not be incurred in a nonresearch setting. Costs for printed reminders included materials, printing, postage, and personnel time associated with individualizing materials and delivery. Cost for ATRs was estimated by totaling the actual number of call attempts for all intended recipients and multiplying this figure by $0.12, the approximate cost per call. This amount was divided by the total number of participants randomized to ATR.

Discussion

This study assessed efficacy of three reminder types (EUCRs, ATRs, and ELRs) on repeat mammography adherence for women with previous mammograms who were due for their next screening. Interventions produced adherence proportions ranging from 72% to 76%. These rates reflect an absolute increase of nearly 18% when compared to pre-intervention rates of repeat mammography adherence. Findings confirm previous research documenting the effectiveness of reminders on mammography use,14,19,32 but they extend these findings to include ATRs.

Comparisons of the three reminders suggest that ATRs are the most effective strategy to increase repeat mammography adherence for women with recent mammograms. Rates of repeat mammography adherence for women in the ATR group were higher (an absolute difference of 4.5%) than for those who received EUCRs containing similar content. This finding was stable across key sample characteristics including race, education, and work status. Of the three reminders, ATRs also cost the least, at an estimated $0.35 per intended recipient.

There are several potential explanations for why ATRs yielded higher rates of repeat mammography adherence compared to EUCRs. The ATRs may have reached a larger proportion of intended recipients than printed reminders, although it was not possible to test this hypothesis. Multiple attempts (an average of three) were made to deliver automated messages, whereas only one printed reminder was sent (unless returned as undeliverable). One clear advantage of ATRs is that the number can be automatically redialed if the message is not delivered successfully, which could have resulted in greater delivery success. Further analyses provided by the ATR vendor showed that they successfully delivered calls for 1168 (86.2%) participants. Although the delivery success rate for study printed materials is not known, it is possible that not all women received them or read them in their entirety. It is also possible that participants viewed ATRs as an appealing and credible channel of communication about mammography. Research suggests that recorded health messages typically are viewed as credible,47,48 especially when characteristics of recipients, such as gender, are matched to those of message senders.49 Although this study did not assess message credibility and appeal, future studies on ATRs might benefit by including these measures.

Effects for ELRs were similar to those for EUCRs (74.5% and 71.8% adherence, respectively). There are several possible reasons the differences were slight. Core content was very similar across reminders. All reminders provided dates of women’s previous mammograms, noted the benefits of mammography, and stated recommended mammography guidelines and health plan coverage. The ELRs were enhanced in that they included theory-guided information on breast cancer severity and susceptibility, as well as mammography facility names and telephone numbers. The ELRs also differed from EUCRs in appearance. Despite these differences, the fundamental message conveyed in these two reminders was essentially the same, and this may have been sufficient to influence behavior. Also, ELRs contained more pages and text than EUCRs, thus requiring more effort from participants. Women may not have read ELR booklets in their entirety. The study design did not permit us to disaggregate the impact of each of these elements to determine why differences between ELRs and EUCRs were slight.

Other study variables were associated with repeat mammography adherence. Women who were adherent to repeat mammography prior to study enrollment were much more likely to respond to reminders compared to those who were non-adherent to repeat mammography prior to study enrollment (86.8% and 58.5%, respectively). This finding is consistent with other mammography studies showing that past screening behaviors strongly predict future mammography use.50–53 Also consistent with previous research is the finding that black women, those who reported financial hardship, and those in poorer health were less likely to have repeat mammograms.6,50,54,55 More intense intervention efforts probably will be needed for these groups. Findings also showed that women in their forties were less likely to be adherent to repeat mammography compared to women aged 50–75 years. Differences in health insurance coverage may explain this finding. At the time of PRISM intervention, the SHP covered mammograms every year for women aged ≥50 years, and every other year for women in their forties. The SHP now has extended annual coverage of mammograms to women aged ≥35 years. Lingering confusion over screening guidelines for women in their forties may also have contributed to this finding.56

The current study focused on repeat mammography for insured women with recent mammograms. Although effective for this study population, ATRs are not an appropriate intervention for women without access to health care or those who have never had mammograms. Also, findings cannot be generalized to minority women other than black women because there were too few ethnic and racial minority women in the sample to analyze their data. The delivery success rate and efficacy of ATRs for racial/ethnic minorities other than black women and/or non-English speakers are not known.

This research should be viewed within the larger context of PRISM, which seeks to find the minimal intervention needed for sustained annual-interval mammography use. These analyses did not address two important questions: (1) Are reminders efficacious over time if delivered regularly?; (2) What is the incremental effect of more intensive intervention—tailored printed materials and telephone counseling—for women who became delayed? Future PRISM research will seek to answer these questions. Also, although study interventions promoted annual mammography, efficacy is not likely to differ substantially for other screening intervals (e.g., biennial screening), although outcomes might be slightly larger with longer screening intervals. It is hypothesized that findings would be very similar if disseminated within a health plan or organization with similar mammography coverage. Researchers designed interventions with potential dissemination as a major consideration and conducted research within a defined population of health plan members.

Conclusion

Although all types of reminders were effective in promoting repeat mammography, ATRs were the most promising. Along with having a greater impact, ATRs were also lower in cost compared to mailed materials. Findings also suggest that communication channel may be a more influential factor than content. This study is, to the best of our knowledge, the first published report to assess efficacy of ATRs to promote regular mammography. Because of their efficacy, ability to reach large numbers of women, low cost, and potential to be customized, ATRs should be considered for use by health organizations as a means to maximize proportions of their members who adhere to regular mammograms.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Deborah Usinger and Tara Strigo, MPH, from the PRISM study, for assistance with data collection. We appreciate the help of Isaac Lipkus, PhD, for his input throughout the project. We are grateful to staff with Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina and the North Carolina State Health Plan for making this research possible.

This study was supported by National Cancer Institute grant 5R01CA105786. At the time of this research, Jennifer Gierisch, PhD, was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (grant 2T32HS000079).

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58(2):71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berry DA, Cronin KA, Plevritis SK, et al. Effect of screening and adjuvant therapy on mortality from breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(17):1784–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Humphrey LL, Helfand M, Chan BK, Woolf SH. Breast cancer screening: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(5 Pt 1):347–60. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-5_part_1-200209030-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tabar L, Yen MF, Vitak B, Chen HH, Smith RA, Duffy SW. Mammography service screening and mortality in breast cancer patients: 20-year follow-up before and after introduction of screening. Lancet. 2003;361(9367):1405–10. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13143-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith RA, Saslow D, Sawyer KA, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines for breast cancer screening: update 2003. CA Cancer J Clin. 2003;53(3):141–69. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.53.3.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blanchard K, Colbert JA, Puri D, et al. Mammographic screening: patterns of use and estimated impact on breast carcinoma survival. Cancer. 2004;101(3):495–507. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michaelson J, Satija S, Moore R, et al. The pattern of breast cancer screening utilization and its consequences. Cancer. 2002;94(1):37–43. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moss SM, Cuckle H, Evans A, Johns L, Waller M, Bobrow L. Effect of mammographic screening from age 40 years on breast cancer mortality at 10 years’ follow-up: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;368(9552):2053–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69834-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White E, Miglioretti DL, Yankaskas BC, et al. Biennial versus annual mammography and the risk of late-stage breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(24):1832–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Breen N, A Cronin K, Meissner HI, et al. Reported drop in mammography: is this cause for concern? Cancer. 2007;109(12):2405–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.CDC. Use of mammograms among women aged ≥40 years-united states, 2000–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:49–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Byers T, Mouchawar J, Marks J, et al. The American Cancer Society challenge goals. How far can cancer rates decline in the U.S. by the year 2015? Cancer. 1999;86(4):715–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clark MA, Rakowski W, Bonacore LB. Repeat mammography: prevalence estimates and considerations for assessment. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26(3):201–11. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2603_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baron RC, Rimer BK, Breslow RA, et al. Client-directed interventions to increase community demand for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening. A systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(1):S:S34–55. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mayer JA, Lewis EC, Slymen DJ, et al. Patient reminder letters to promote annual mammograms: a randomized controlled trial. Prev Med. 2000;31(4):315–22. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quinley J, Mahotiere T, Messina CR, Lee TK, Mikail C. Mammography-facility-based patient reminders and repeat mammograms for Medicare in New York state. Prev Med. 2004;38(1):20–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rakowski W, Lipkus IM, Clark MA, et al. Reminder letter, tailored stepped-care, and self-choice comparison for repeat mammography. Am J Prev Med. 2003;25(4):308–14. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rimer BK, Halabi S, Skinner CS, et al. Effects of a mammography decision-making intervention at 12 and 24 months. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22(4):247–57. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00417-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wagner TH. The effectiveness of mailed patient reminders on mammography screening: a meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(1):64–70. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(97)00003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yabroff KR, Mandelblatt JS. Interventions targeted toward patients to increase mammography use. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8(9):749–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goel A, George J, Burack RC. Telephone reminders increase re-screening in a county breast screening program. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19(2):512–21. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Legler J, Meissner HI, Coyne C, Breen N, Chollette V, Rimer BK. The effectiveness of interventions to promote mammography among women with historically lower rates of screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11(1):59–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clark MA, Rakowski W, Ehrich B, et al. The effect of a stage-matched and tailored intervention on repeat mammography. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00406-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lipkus IM, Rimer BK, Halabi S, Strigo TS. Can tailored interventions increase mammography use among HMO women? Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corkrey R, Parkinson L, Bates L. Pressing the key pad: trial of a novel approach to health promotion advice. Prev Med. 2005;41(2):657–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crawford AG, Sikirica V, Goldfarb N, et al. Interactive voice response reminder effects on preventive service utilization. Am J Med Qual. 2005;20(6):329–36. doi: 10.1177/1062860605281176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alemi F, Alemagno SA, Goldhagen J, et al. Computer reminders improve on-time immunization rates. Med Care. 1996;34(10):S:OS45–51. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199610003-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacobson VJ, Szilagyi P. Patient reminder and patient recall systems to improve immunization rates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(3):CD003941. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003941.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lieu TA, Capra AM, Makol J, Black SB, Shinefield HR. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of letters, automated telephone messages, or both for underimmunized children in a health maintenance organization. Pediatrics. 1998;101(4):E3. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.4.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krishna S, Balas EA, Boren SA, Maglaveras N. Patient acceptance of educational voice messages: a review of controlled clinical studies. Methods Inf Med. 2002;41(5):360–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roter DL, Hall JA, Merisca R, Nordstrom B, Cretin D, Svarstad B. Effectiveness of interventions to improve patient compliance: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 1998;36(8):1138–61. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199808000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taplin SH, Barlow WE, Ludman E, et al. Testing reminder and motivational telephone calls to increase screening mammography: a randomized study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(3):233–42. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fishman P, Taplin S, Meyer D, Barlow W. Cost-effectiveness of strategies to enhance mammography use. Eff Clin Pract. 2000;3(5):213–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stern SE, Mullennix JW. Sex differences in persuadability of human and computer-synthesized speech: meta-analysis of seven studies. Psychol Rep. 2004;94(3 Pt 2):1283–92. doi: 10.2466/pr0.94.3c.1283-1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kreuter MW, Skinner CS, Holt CL, et al. Cultural tailoring for mammography and fruit and vegetable intake among low-income African-American women in urban public health centers. Prev Med. 2005;41(1):53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noar SM, Benac CN, Harris MS. Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychol Bull. 2007;133(4):673–93. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rimer BK, Kreuter MW. Advancing tailored health communication: a persuasion and message effects perspective. J Commun. 2006;56(S1):s184–s201. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Janz NK, Becker MH. The health belief model: a decade later. Health Educ Q. 1984;11(1):1–47. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Champion V, Maraj M, Hui S, et al. Comparison of tailored interventions to increase mammography screening in nonadherent older women. Prev Med. 2003;36(2):150–8. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(02)00038-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Champion V, Skinner CS, Hui S, et al. The effect of telephone versus print tailoring for mammography adherence. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;65(3):416–23. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.King ES, Rimer BK, Trock B, Balshem A, Engstrom P. How valid are mammography self-reports? Am J Public Health. 1990;80(11):1386–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.11.1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rauscher GH, O’Malley MS, Earp JA. How consistently do women report lifetime mammograms at successive interviews? Am J Prev Med. 2002;22(1):8–14. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00405-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rauscher GH, Johnson TP, Cho YI, Walk JA. Accuracy of self-reported cancer-screening histories: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(4):748–57. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kleinbaum DG. Logistic regression: a self-learning text. New York: Springer; 1994. p. 282. [Google Scholar]

- 45.The American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard definitions: final dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys. 4. Lenexa Kansas: AAPOR; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 46.DeFrank JT, Bowling JM, Rimer BK, Gierisch JM, Skinner CS. Triangulating differential nonresponse by race in a telephone survey. Prev Chronic Dis. 2007;4(3):A60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Glanz K, Shigaki D, Farzanfar R, Pinto B, Kaplan B, Friedman RH. Participant reactions to a computerized telephone system for nutrition and exercise counseling. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;49(2):157–63. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaplan B, Farzanfar R, Friedman RH. Personal relationships with an intelligent interactive telephone health behavior advisor system: a multimethod study using surveys and ethnographic interviews. Int J Med Inform. 2003;71(1):33–41. doi: 10.1016/s1386-5056(03)00072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nass C, Lee KM. Does computer-synthesized speech manifest personality? Experimental tests of recognition, similarity-attraction, and consistency-attraction. J Exp Psychol Appl. 2001;7(3):171–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bobo JK, Shapiro JA, Schulman J, Wolters CL. On-schedule mammography rescreening in the national breast and cervical cancer early detection program. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13(4):620–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Halabi S, Skinner CS, Samsa GP, Strigo TS, Crawford YS, Rimer BK. Factors associated with repeat mammography screening. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(12):1104–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mayne L, Earp J. Initial and repeat mammography screening: different behaviors/different predictors. J Rural Health. 2003;19(1):63–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2003.tb00543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schueler KM, Chu PW, Smith-Bindman R. Factors associated with mammography utilization: a systematic quantitative review of the literature. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2008;17(9):1477–98. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McAlearney AS, Reeves KW, Tatum C, Paskett ED. Cost as a barrier to screening mammography among underserved women. Ethn Health. 2007;12(2):189–203. doi: 10.1080/13557850601002387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rakowski W, Meissner H, Vernon SW, Breen N, Rimer B, Clark MA. Correlates of repeat and recent mammography for women ages 45 to 75 in the 2002 to 2003 health information national trends survey (HINTS 2003) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(11):2093–101. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Calvocoressi L, Sun A, Kasl SV, Claus EB, Jones BA. Mammography screening of women in their 40s: impact of changes in screening guidelines. Cancer. 2008;112(3):473–80. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]