Abstract

Background:

Narcolepsy is a chronic neurodegenerative disorder with a typical onset in childhood or early adulthood. Narcolepsy may have serious negative effects on health-, social-, education-, and work-related issues for people with narcolepsy and for their families. The disease may, thus, present a significant socioeconomic burden, but no studies to date have addressed the indirect and direct costs of narcolepsy.

Methods:

Using records from the Danish National Patient Registry (1998-2005), we identified 459 Danish patients with the diagnosis of narcolepsy. Using a ratio of 1 patient record to 4 control subjects’ records, we then compared the information of patients with narcolepsy with that of 1836 records from age- and sex-matched, randomly chosen citizens in the Danish Civil Registration System Statistics. We calculated the annual direct and indirect health costs, including labor supply and social transfer payments (which include income derived from state coffers, such as subsistence allowances, pensions, social security, social assistance, public personal support for education, etc.). Direct costs included frequencies and costs of hospitalizations and weighted outpatient use, according to diagnosis-related groups, and specific outpatient costs based on data from The Danish Ministry of Health. The use of and costs of drugs were based on data from the Danish Medicines Agency. The frequencies and costs from primary sectors were based on data from The National Health Security. Indirect costs were based on income data derived from data from the Coherent Social Statistics.

Results:

Patients with narcolepsy had significantly higher rates of health-related contact and medication use and higher expenses, as compared with control subjects. They also had higher unemployment rates. The income level of patients with narcolepsy who were employed was lower than that of employed control subjects. The annual total direct and indirect costs were €11,654 (€ = Eurodollars) for patients with narcolepsy and €1430 for control subjects (p < 0.001), corresponding to an annual mean excess health-related cost of €10,223 for each patient with narcolepsy. In addition, the patients with narcolepsy received an annual social transfer income of €2588.

Conclusion:

The study confirms that narcolepsy has major socioeconomic consequences for the individual patient and for society. Early diagnosis and treatment could potentially reduce disease burden, which would have a significant socioeconomic impact.

Citation:

Jennum P; Knudsen S; Kjellberg J. The economic consequences of narcolepsy. J Clin Sleep Med 2009;5(3):240–245.

Keywords: Narcolepsy, social-economics, epidemiology, medication, consequences

Narcolepsy is a relatively common neurologic sleep disorder, with a prevalence of 1 per 2000 people. Because the disorder is chronic and typically has an early age of onset, narcolepsy may have a serious effect on the individual patient related to social, family, quality-of-life, education, work, and health issues. During the past 20 years, significant progress has been made in understanding the underlying mechanism, diagnosis, and management of the disease. A major step in the pathogenesis of narcolepsy is destruction of hypocretin-producing cells in the ventral hypothalamus in genetically susceptible individuals who carry 1 or more alleles of HLA DQB1*0602, potentially related to immune or other processes.1–3 Significant progress has been made in treatment, and additional advances are to be expected with our further understanding of the brain processes underlying the disease. Despite this progress, most cases of narcolepsy are undiagnosed and, therefore, not treated.4,5 Recent studies have identified an increased socioeconomic impact of narcolepsy6–9 and a reduced quality of life.7, 9,12 To date, studies have been conducted using questionnaires in selected patients from outpatient clinics or telephone-based surveys, and estimates of the economic burden have been extracted from this information.

In Denmark, however, it is possible to more precisely calculate indirect and direct costs because medication, social, income, and employment data from all patients—including information from public and private hospitals and clinics in the secondary and primary sector—are registered in a central database, the National Patient Registry (NPR). We conducted the current study to evaluate the socioeconomic consequences of narcolepsy, as determined in a national population-based study.

METHODS

In Denmark, all patient contacts are recorded in the NPR by time of contact and include the primary diagnosis. The NPR includes administrative information, diagnoses, and diagnostic and treatment procedures using several international classification systems, including the International Classification of Disorders (ICD-10). Thus, the NPR is a time-based national database that includes data from all patient contacts; therefore, the data that we extrapolated are representative of all patients in Denmark who have received a diagnosis of narcolepsy in the primary or secondary sector in both public and private hospitals.

The economic consequence of narcolepsy was estimated by determining the yearly cost of illness per patient diagnosed with narcolepsy (ICD DG474) and comparing that calculation with the cost of healthcare in a matched control group. The health cost was then divided into annual direct and indirect healthcare costs.

The indirect costs, measured from the perspective of societal costs, included those related to a reduced labor supply and to social transfer payments. In Denmark, social transfer payments comprise income derived from state coffers. These payments include subsistence allowances, pensions, social security, social assistance, public personal support for education, and other payments. Direct costs included costs of hospitalization and outpatient cost weighted by use, according to diagnosis-related groups, and specific outpatient costs—all based on data from The Danish Ministry of Health. The use and costs of drugs were based on data from the National Danish Medicine Agency, which includes the retail price of the drug (including dispensing costs) multiplied by the number of transactions. The frequencies and costs of consultations with general practitioners and other specialists were based on data from The National Health Security. Indirect costs were based on income numbers from Coherent Social Statistics data.

Cost-of-illness studies measure the economic burden resulting from disease and illness across a defined population, including both direct and indirect costs. Direct costs are the value of resources used in the treatment, care, and rehabilitation of persons with the condition under study. Indirect costs represent the value of economic resources lost because of disease-related work disability or premature mortality. It is important to distinguish costs from monetary transfer payments, such as disability and welfare payments. Such payments represent a transfer of purchasing power to the recipients from the general taxpayers but do not represent net increases in the use of resources and are, therefore, not included in the total cost estimate.

By reviewing the NPR, we identified all patients who were diagnosed with narcolepsy from 1998 to 2005. Then, using data from the Civil Registration System Statistics Denmark, we randomly selected citizens who had the same age and sex as the patients with narcolepsy but who had no diagnosis of narcolepsy or hypersomnia. The ratio of control subjects to patients was 4:1. Data from patients and matched control subjects that could not be identified in the Coherent Social Statistics database were excluded from the sample. (More than 99% of the observations in both groups were successfully matched.) Patients and matched control subjects were followed from diagnosis year until 2005. Costs were measured on a yearly basis and adjusted to 2005 prices using the health sector price index for health sector costs, and the general price index was applied to nonmedical costs. All cost were measured in DKK and converted into Euros (€1: DKK 7.45).

The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency. Because the data handling was anonymous, individual or ethics approval was not mandatory. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.1.3 (SAS, Inc., Cary, NC). Statistical significance of the cost estimates was generated using nonparametric bootstrap analysis.13

RESULTS

In total, 462 patients with narcolepsy were identified. Complete data for cross-tabulations were available for 459 patients (218 men and 241 women) and 1836 control subjects without narcolepsy or other hypersomnias of central origin, resulting in observation years of 1907 for patients and 7692 for control subjects.

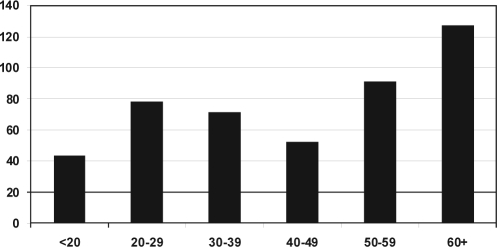

The age distribution of the patients is shown in Figure 1. The age distribution was relatively wide. The number of young patients with a new diagnosis of narcolepsy increased during the study period: in 1998, 9 of 55 patients were younger than 30 years of age, and, in 2005, 22 of 53 patients were in this age group. These data probably reflect the increased awareness of narcolepsy among health care professionals.

Figure 1.

Number and age distribution of patients receiving the diagnosis of narcolepsy from 1998-2005.

Direct Costs as Outpatient Clinic Costs, Hospital Costs, Primary Care Costs, and Drug Costs

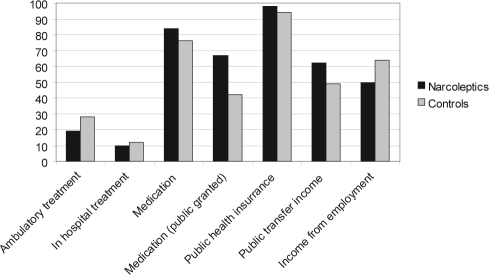

More patients than control subjects were treated in outpatient clinics (53% vs 28%, p < 0.0001), were hospitalized (25% vs 12%, p < 0.0001), and had contact with the primary care system (98% vs 94%). Eight-four percent of patients were taking medication, versus 76% of control subjects, with 67% of patients receiving public support for their medications, versus 42% of control subjects (p < 0.001).

Indirect Cost as Social Costs, Employment Rate, and Income

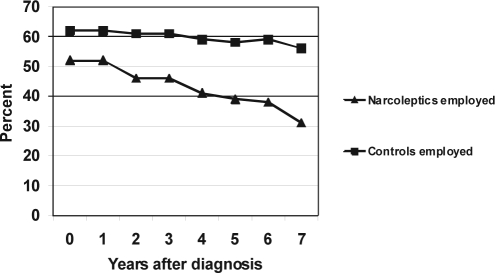

More patients than control subjects received social services (62% vs 49%, p < 0.001). Fewer patients with narcolepsy than control subjects received income from employment (50% versus 64%, p < 0.01) (Figure 2). Patients with narcolepsy had lower employment rates and significantly higher social transfer rates, as compared with control subjects (Table 1). The employment rate for patients steadily decreased for patients in the time period after they received a diagnosis of narcolepsy, compared with the same period for control subjects (Figure 3). A corresponding increase in social transfer expenses took place, whereas the rate of retirement was similar in both groups (not shown).

Figure 2.

Percentage of people with narcolepsy and control subjects receiving any of the services (public or income).

Table 1.

Percentages of Unemployment, Transfer Income, and Pension/Retirement in Patients with Narcolepsy and Control Subjects

| Demographic | Patients with narcolepsy | Control subjects | p Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employedb on leave | 47 | 61 | < 0.0001 |

| Receiving transfer income | 25 | 10 | < 0.0001 |

| Receiving pension benefits payable between early retirement and normal retirement pension | 22 | 23 | 0.16 |

| Other | 6 | 5 | 0.66 |

Data are presented as percentages.

Bootstrap

Includes self-employed persons, salary earners, and students.

Figure 3.

Employment rate at the time of diagnosis and in the years after diagnosis in patients with narcolepsy and control subjects, all values: p < 0.0001 between patients and controls.

Total Health Costs Per Year

The sources of information and the average annual health cost per person year by cost categories in Denmark are presented in Table 2. Direct health costs (general practitioner services, hospital services, and medication) and indirect costs (loss of labor market income), sum of direct and indirect costs (being €10,303), and social transfer payments are all significantly different in patients with narcolepsy, as compared with that of control subjects. The social transfer payments for patients with narcolepsy was €8,107 per year versus €5,519 per year in the control group. To assess whether there was a difference in consumption of health services we assessed the total number of contacts before and after a diagnosis is made. Patients with narcolepsy have 22 contacts before and after diagnosis of a two year period, controls 12 and 11 contacts per two years

Table 2.

Sources of Information and the Average Annual Health Cost (in Euros) per Person Year by Cost Categories in Denmark

| Category of data | Sources | Annual costs narcolepsy | Annual costs controls | p Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct health costs | ||||

| The primary sector | The National Health | 285 | 197 | < 0.0001 |

| Insurance Security System | ||||

| Inpatient cost | Danish Ministry of Heath | 2,646 | 705 | < 0.0001 |

| Outpatient cost | Danish Ministry of Heath | 411 | 191 | < 0.0001 |

| Drugs | Danish Medicines Agency | 821 | 257 | < 0.0001 |

| Total direct health costs | 4,163 | 1350 | ||

| Labor market income | ||||

| Indirect cost of narcolepsy | Coherent Social Statistics | 13,657 | 21,147 | < 0.0001 |

| 7,490 | ||||

| Sum of direct and indirect costs | 11,653 | 1350 | < 0.0001 | |

| Net yearly costs of narcolepsy | 10,303 | |||

| Social transfer payments | Coherent Social Statistics | 8,107 | 5519 | < 0.0001 |

Bootstrap

DISCUSSION

This is the first study objectively evaluating the socioeconomic impact of narcolepsy. The study is population based and includes all patients with a diagnosis of narcolepsy in Denmark. Patients with narcolepsy had significantly higher rates of contact with the healthcare system, which included all healthcare sectors: general practice, outpatient clinics, and in-hospital services. The patients had higher rates of medication use, including public-supported medication. The total expenses were higher in the group of patients with narcolepsy, as compared with age- and sex-matched control subjects. Narcoleptic patients had lower employment rates; they were significantly more often receiving welfare payments; and, among employed patients, had lower incomes, compared with employed control subjects. Thus, narcolepsy has a significant socioeconomic impact. The differences between patients with narcolepsy and control subjects are considerable: as compared with control subjects, the medication costs were more than 3 times higher in patients with narcolepsy, the hospital costs were 3 to 4 times higher, and the employment rate was more than 30% lower. Employed patients earned only two-thirds that of the control subjects’ income. Patients with narcolepsy had much higher social expenditures than did controls subjects. Because narcolepsy is a chronic disease with early disease onset, typically in the young age, the economic impact of the disease is considerable

The occurrence of a decrease in employment rate after the establishment of a diagnosis is well known in other chronic disorders. Several factors may explain this: (1) patients may have symptoms long before the narcolepsy diagnose is made; (2) patients may not be able to seek a pension before they receive a diagnose and, thus, they maintain their employment before their diagnosis; and (3) finally, patients may only seek professional help when they have arrived at the point at which their social lives have reached an impasse and their symptoms have led to exhaustion. Narcolepsy is often misdiagnosed or not recognized, and the symptoms may, therefore, be mistreated, leading to a significant health burden. We have not evaluated the data regarding morbidity before the first narcolepsy diagnosis, but further extensions of the analysis of the data could evaluate such factors and should include types of comorbidities. If treatment and early intervention for disease control are effective in terms of influencing the negative social prognosis, a huge potential exists to implement early intervention, thus sparing the patient and the community from the negative consequences of the disease.

In the current study, we used the diagnosis based on reports from all Danish clinics or hospitals registered in the NPR, thus representing a complete national patient sample. This was possible because all Danes are registered using social security codes, and data include health, medication, social, and employment information. The data on the diagnosis of narcolepsy registered in this database are derived from clinical information with or without the results of polysomnography or Multiple Sleep Latency Tests, which would have provided an objective diagnosis. Conducting polysomnography or Multiple Sleep Latency Tests was not part of the current diagnostic requirement, although this lack of objective testing may have increased the risk that we included patients with diseases other than narcolepsy. The data were extracted from the period 1998-2005 and calculated for 2005 prices. The control subjects were randomly selected from the background population without narcolepsy, which includes healthy and nonhealthy subjects, to evaluate the additional health and socioeconomic impact of narcolepsy. We used 4 randomly selected citizens to serve as controls for each patient (ratio 4:1) to reduce the variation among controls and to ensure that we had a representative control population. Statistical analyses prior to the study initiation found that the use of at least 4 control subjects would equalize the variations in the sample population and increase the statistical power of the study.

No studies have been conducted that show whether people with narcolepsy have a higher risk of being involved in motor vehicle crashes or occupational accidents, but it is likely that people with narcolepsy have a higher risk of being involved in motor vehicle crashes.14–21 We did not extract the rate of motor vehicle crashes in the current study. The impact of narcolepsy on potential health and occupation consequences, yielding estimates of increased morbidity, and other direct and indirect estimates are included in the analysis because all primary and secondary health-related costs are included. However, the secondary effects of narcolepsy on accidents (eg, the impact of motor vehicle crashes on individuals or materials) and on family members are not included because such estimates are very difficult to evaluate. Consequently, the economic estimates represent a conservative, but concrete and realistic, estimate of the consequences of narcolepsy. With the current estimates of the prevalence of narcolepsy, we expect the number of people in Denmark who have narcolepsy to be 2500 to 3000. Narcolepsy is not a well-known disorder in most countries, resulting in narcolepsy often being undiagnosed and not treated.5 There are no data suggesting that people who have received a diagnosis of narcolepsy have a more-severe form of the disease, as compared with people who have narcolepsy that is not diagnosed. Therefore, the estimates from this study suggest a significant health and economic impact of the disease.

Studies have shown that people with narcolepsy report having a reduced quality of life,7,9,10,12,20,22 with the impact being comparable with that of other neurologic diseases, such as Parkinson disease and multiple sclerosis. Recent studies have suggested that narcolepsy may impart an increased socioeconomic burden. The 2-part study by Dodel et al7 was based on a standardized telephone interview that they used to inquire about the disease and its burden, with additional health-related quality-of-life scales (SF-36 and EQ-5D) mailed to 75 people who responded affirmatively to having a diagnosis of narcolepsy. Direct and indirect costs were calculated from the societal perspective. Transfer income was not included. The total annual costs associated with a diagnosis of narcolepsy were estimated to be €14,790 ± €16,180. These estimates were based on the results of this analysis from a clinical population, and no data from control subjects were included. The major difference is that, in our analysis, we estimated the objective costs of health care, medication costs, and income and social costs for people with narcolepsy and compared these data with these same costs for age- and sex-matched controls. We included data in this national database from all patients with different disease severities for a longer period of time. We also included data from elderly patients, who have lower socioeconomic consequences, as compared with younger patients. The results of our analysis show that the total objective annual social and health-related costs of narcolepsy are €11,654, with an excess cost of €10,303, as compared with that of control subjects. In addition, the patients with narcolepsy had an annual social transfer income that was €2588 higher than that of control subjects.

During the past few years, insight into the mechanism of narcolepsy has increased, and improvements have been made into the diagnosis and treatment of this disease. The validity of diagnostic criteria and electrophysiologic methods used to confirm the diagnosis have been evaluated,23–25 and potential new methods of HLA typing26 combined with measurement of hypocretin-1 levels in cerebrospinal fluid27–32 have led to critical improvements in disease classification and the diagnosis and treatment of narcolepsy. These steps are vitally important because narcolepsy is often not diagnosed but is potentially treatable. The current treatment of narcolepsy is characterized by a number of different types of modalities. Although several lines of treatment have been suggested, only a few controlled trials have been conducted.33 Despite these limitations, the results of several studies suggest that treatment may improve quality of life in people with narcolepsy.20,34–36 However, no evidence exists to support the notion that the early diagnosis of narcolepsy impacts the socioeconomic, education, or professional consequence of the disease, nor does providing information, education, and professional advice to these patients. Furthermore, no studies have presented evidence that medical treatment influences education level or employment status. The results of the current study, however, strongly suggest that such interventions are most relevant.

In conclusion, the current study, which includes data from all patients diagnosed with narcolepsy during a 6-year period, found that narcolepsy leads to significantly lower levels of employment and income and higher health-related and social transfer costs. It also identified a significant health-related impact and socioeconomic aspect of the disease, revealing a great need to further address the relevance of diagnosing narcolepsy and measuring the effect of treatment. Professionals should be aware of the disease to ensure adequate management, including diagnosis, treatment follow-up, and patient information regarding education and profession. Appropriate treatment must be provided not only to increase quality of life, but also to assist the patients in their ability to continue taking part in their family and professional lives. There is a further need to focus on disease management and the effects of narcolepsy on quality of life, socioeconomic factors, work capabilities, and motor vehicle crashes to reduce these costs for patients and society.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This study was supported in part by UCB International. The support was used for statistical analysis. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dauvilliers Y, Arnulf I, Mignot E. Narcolepsy with cataplexy. Lancet. 2007;369:499–511. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knudsen S, Mikkelsen JD, Jennum P. Antibodies in narcolepsy-cataplexy patient serum bind to rat hypocretin neurons. Neuroreport. 2007;18:77–9. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e328010baad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Overeem S, Black JL, 3rd, Lammers GJ. Narcolepsy: immunological aspects. Sleep Med Rev. 2008;12:95–107. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knudsen S, Jennum PJ. [Narcolepsy--new implications of molecular biology] Ugeskr Laeger. 2006;168:3699–704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kryger MH, Walid R, Manfreda J. Diagnoses received by narcolepsy patients in the year prior to diagnosis by a sleep specialist. Sleep. 2002;25:36–41. doi: 10.1093/sleep/25.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Broughton R, Valley V, Aguirre M, Roberts J, Suwalski W, Dunham W. Excessive daytime sleepiness and the pathophysiology of narcolepsy-cataplexy: a laboratory perspective. Sleep. 1986;9:205–15. doi: 10.1093/sleep/9.1.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dodel R, Peter H, Spottke A, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with narcolepsy. Sleep Med. 2007;8:733–41. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dodel R, Peter H, Walbert T, et al. The socioeconomic impact of narcolepsy. Sleep. 2004;27:1123–8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.6.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ervik S, Abdelnoor M, Heier MS, Ramberg M, Strand G. Health-related quality of life in narcolepsy. Acta Neurol Scand. 2006;114:198–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2006.00594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daniels E, King MA, Smith IE, Shneerson JM. Health-related quality of life in narcolepsy. J Sleep Res. 2001;10:75–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2001.00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goswami M. The influence of clinical symptoms on quality of life in patients with narcolepsy. Neurology. 1998;50:S31–6. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.2_suppl_1.s31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stores G, Montgomery P, Wiggs L. The psychosocial problems of children with narcolepsy and those with excessive daytime sleepiness of uncertain origin. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e1116–23. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aldrich CK, Aldrich MS, Aldrich TK, Aldrich RF. Asleep at the wheel. The physician’s role in preventing accidents `just waiting to happen’. Postgrad Med. 1986;80(233-5, 8):40. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1986.11699572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aldrich MS. Automobile accidents in patients with sleep disorders. Sleep. 1989;12:487–94. doi: 10.1093/sleep/12.6.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bartels EC, Kusakcioglu O. Narcolepsy: a possible cause of automobile accidents. Lahey Clin Found Bull. 1965;14:21–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Findley L, Unverzagt M, Guchu R, Fabrizio M, Buckner J, Suratt P. Vigilance and automobile accidents in patients with sleep apnea or narcolepsy. Chest. 1995;108:619–24. doi: 10.1378/chest.108.3.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grubb TC. Narcolepsy and highway accidents. JAMA. 1969;209:1720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wright J, Johns R, Watt I, Melville A, Sheldon T. Health effects of obstructive sleep apnoea and the effectiveness of continuous positive airways pressure: a systematic review of the research evidence. BMJ. 1997;314:851–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7084.851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beusterien KM, Rogers AE, Walsleben JA, et al. Health-related quality of life effects of modafinil for treatment of narcolepsy. Sleep. 1999;22:757–65. doi: 10.1093/sleep/22.6.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reimer MA, Flemons WW. Quality of life in sleep disorders. Sleep Med Rev. 2003;7:335–49. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2001.0220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vignatelli L, D’Alessandro R, Mosconi P, et al. Health-related quality of life in Italian patients with narcolepsy: the SF-36 health survey. Sleep Med. 2004;5:467–75. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lammers GJ, Overeem S, Bassetti C. Silber MH, Krahn LE, Olson EJ. Diagnosing narcolepsy: validity and reliability of new diagnostic criteria. Sleep Med. 2002 Mar;3(2):109-13. Sleep Med. 2002;3:531–2. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(01)00161-7. author reply 3-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silber MH, Krahn LE, Olson EJ. Diagnosing narcolepsy: validity and reliability of new diagnostic criteria. Sleep Med. 2002;3:109–13. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(01)00161-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vignatelli L, Plazzi G, Bassein L, et al. ICSD diagnostic criteria for narcolepsy: interobserver reliability. Intemational Classification of Sleep Disorders. Sleep. 2002;25:193–6. doi: 10.1093/sleep/25.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsuki K, Honda Y, Juji T. Diagnostic criteria for narcolepsy and HLA-DR2 frequencies. Tissue Antigens. 1987;30:155–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1987.tb01614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bassetti C, Gugger M, Bischof M, et al. The narcoleptic borderland: a multimodal diagnostic approach including cerebrospinal fluid levels of hypocretin-1 (orexin A) Sleep Med. 2003;4:7–12. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(02)00191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baumann CR, Khatami R, Werth E, Bassetti CL. Hypocretin (orexin) deficiency predicts severe objective excessive daytime sleepiness in narcolepsy with cataplexy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:402–4. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.067207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heier MS, Evsiukova T, Vilming S, Gjerstad MD, Schrader H, Gautvik K. CSF hypocretin-1 levels and clinical profiles in narcolepsy and idiopathic CNS hypersomnia in Norway. Sleep. 2007;30:969–73. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.8.969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kunimoto M. The level of hypocretin 1 (orexin A) in cerebrospinal fluid and the diagnosis of narcolepsy and other somnolent disorders. Intern Med. 2003;42:634–5. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.42.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mignot E, Chen W, Black J. On the value of measuring CSF hypocretin-1 in diagnosing narcolepsy. Sleep. 2003;26:646–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mignot E, Lammers GJ, Ripley B, et al. The role of cerebrospinal fluid hypocretin measurement in the diagnosis of narcolepsy and other hypersomnias. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:1553–62. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.10.1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Billiard M, Bassetti C, Dauvilliers Y, et al. EFNS guidelines on management of narcolepsy. Eur J Neurol. 2006;13:1035–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Becker PM, Schwartz JR, Feldman NT, Hughes RJ. Effect of modafinil on fatigue, mood, and health-related quality of life in patients with narcolepsy. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;171:133–9. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1508-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murali H, Kotagal S. Off-label treatment of severe childhood narcolepsy-cataplexy with sodium oxybate. Sleep. 2006;29:1025–9. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.8.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weaver TE, Cuellar N. A randomized trial evaluating the effectiveness of sodium oxybate therapy on quality of life in narcolepsy. Sleep. 2006;29:1189–94. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.9.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]