Abstract

Mass spectrometry technologies for measurement of cellular metabolism are opening new avenues to explore drug activity. Trimethoprim is an antibiotic that inhibits bacterial dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR). Kinetic flux profiling with 15N-labeled ammonia in Escherichia coli reveals that trimethoprim leads to blockade not only of DHFR but also of another critical enzyme of folate metabolism: folylpoly-γ-glutamate synthetase (FP-γ-GS). Inhibition of FP-γ-GS is not directly due to trimethoprim. Instead, it arises from accumulation of DHFR’s substrate dihydrofolate, which we show is a potent FP-γ-GS inhibitor. Thus, owing to the inherent connectivity of the metabolic network, falling DHFR activity leads to falling FP-γ-GS activity in a domino-like cascade. This cascade results in complex folate dynamics, and its incorporation in a computational model of folate metabolism recapitulates the dynamics observed experimentally. These results highlight the potential for quantitative analysis of cellular metabolism to reveal mechanisms of drug action.

Enzyme inhibition is among the best established mechanisms of drug action1. Nevertheless, even for enzyme inhibitors, the mechanisms of action are often incompletely understood2. For example, drugs known to be inhibitors of one enzyme may further bind to unidentified enzymes or indirectly interact with other pathways. In part, this limited understanding is due to the scope and complexity of cellular chemical reactions as well as the associated difficulty of tracking many reactions at once. The recent development of technologies that can measure many cellular metabolites3–5 and metabolic fluxes6–8 in parallel may allow for more complete elucidation of actions of enzyme inhibitors. Here we apply LC-MS/MS to explore the effects of the DHFR inhibitor trimethoprim (1) in Escherichia coli by tracking both metabolite concentrations and fluxes throughout the folate pathway.

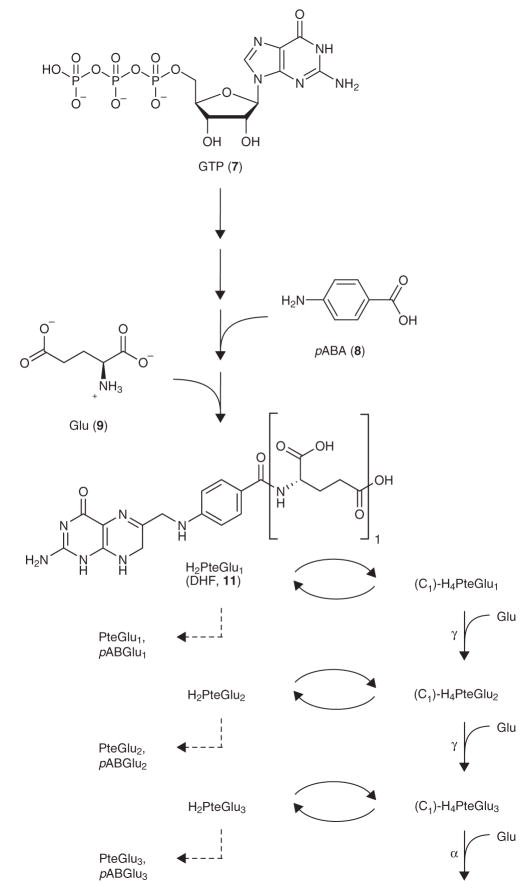

Folates are cofactors that accept or donate one-carbon units for the biosynthesis of essential metabolites including purines, thymine (2), methionine (3) and glycine (4). Folate metabolism is the target of many therapeutics, including antibiotics (trimethoprim and sulfa drugs)9–11 and anticancer agents (methotrexate, 5, and pemetrexed, 6)12. Folates are synthesized from GTP (7), p-aminobenzoic acid (pABA, 8) and glutamates (9) and can exist in three different oxidation/reduction states: PteGlun (pteroylglutamate, or folate, 10), H2PteGlun (dihydrofolate, DHF, 11) and H4PteGlun (tetrahydrofolate, THF, 12). The folate synthesis pathway is shown in Scheme 1. Dihydrofolate species (H2PteGlun) are reduced by DHFR to form tetrahydrofolate species (H4PteGlun)13. Tetrahydrofolate species can be substituted with one-carbon units to form the following folates: 5-methyl-H4PteGlun (13), 5-formyl-H4PteGlun (14), 5-formimino- H4PteGlun (15), 10-formyl-H4PteGlun (16), 5,10-methenyl-H4PteGlun (17) and 5,10-methylene-H4PteGlun (18), which are the active onecarbon donors in specific biosynthetic reactions. Dihydrofolate species are generated from reduced folates as a byproduct of thymidylate synthase, which catalyzes the conversion of dUMP (19) and 5,10- methylene-H4PteGlun to dTMP (20) and H2PteGlun (refs. 14–18).

Scheme 1.

Folate synthesis, one-carbon substitution, polyglutamation and catabolism in E. coli. A series of reactions converts GTP and pABA to dihydropteroic acid (H2Pte). Linkage of H2Pte to glutamate forms dihydrofolate (H2PteGlu1, DHF). DHF and its polyglutamated forms (H2PteGlun) are reduced by DHFR to form tetrahydrofolate species (H4PteGlun), which can gain one-carbon units to form C1-H4PteGlun (5-methyl-H4PteGlun, 5-formyl-H4PteGlun, 5-formimino-H4PteGlun, 10-formyl-H4PteGlun, 5,10-methenyl-H4PteGlun and 5,10-methylene- H4PteGlun), the active one-carbon donors in specific biosynthetic reactions. 5,10-methylene-H4PteGlun is the substrate of TS, which regenerates H2PteGlun. H2PteGlun can also be oxidized to folate species (PteGlun) or catabolized to pABGlun. Both H4PteGlun and C1-H4PteGlun are substrates of folylpolyglutamate synthetase (FPGS) to form the corresponding (C1)- H4PteGlun+1 species. Second and third glutamate residues are connected via γ-linkages to previous glutamates, and the rest are connected via α-linkages.

Reduced forms of folates are polyglutamated to increase their retention in the cell and to become the preferred substrates in vivo for many folate-dependent enzymes19–23. E. coli has two enzymes that add glutamate residues to folates: FP-γ-GS and FP-α-GS (refs. 24,25). FP-γ-GS adds the first three glutamates to folates26. Additional glutamates (fourth glutamate and on) are added by FP-α-GS. Thus, the second and third glutamate residues are bonded via γ-linkages to previous glutamates, and additional glutamate residues are bonded via α-linkages.

Various methods for detecting folates are available and have been reviewed23. Recently reported LC-MS/MS methods enable quantification of the full diversity of intracellular folates, by differentiating related species based on chromatographic retention time, parent ion mass and fragmentation pattern27,28. Although measurements of folate pools have been previously reported, measurements of fluxes through folate pools have not. To investigate the kinetics of assimilation of isotope-labeled ammonia into folates, we apply the concept of kinetic flux profiling (KFP), which monitors the dynamics of incorporation of isotope-labeled nutrients into downstream products using LC-MS/MS (ref. 7).

The antifolate drug trimethoprim inhibits bacterial DHFR, which catalyzes the reduction of dihydrofolate (H2PteGlun) to tetrahydrofolate (H4PteGlun)13. Treatment of E. coli with trimethoprim results in a rapid accumulation of dihydrofolate, which is then further oxidized to folate (PteGlun) and catabolized to pteridines and p-aminobenzoylglutamate (pABGlun, 21)2,29,30.

To examine further the mechanism of action of trimethoprim, we studied the dynamics of folate pools following its addition to exponentially growing E. coli. We found an unexpected nonmonotonic response in reduced folate mono- and diglutamate species: after initially falling as expected, they subsequently increased. We demonstrate that this increase results from blockade of FP-γ-GS, and that this blockade is caused by dihydrofolate species that accumulate during DHFR blockade. Thus, trimethoprim is an indirect inhibitor of FP-γ-GS. We support our findings with quantitative modeling of the folate network dynamics. These results highlight the utility of applying emerging metabolomic and kinetic flux profiling technologies to further understand drug mechanisms.

RESULTS

Dynamics of intracellular folate pools

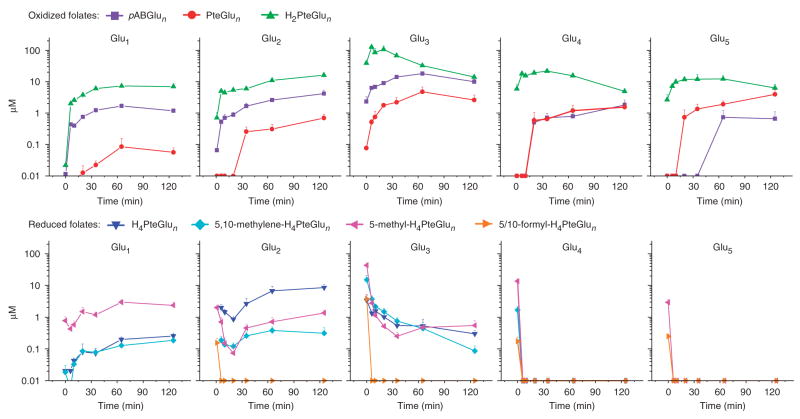

The dynamic response of the pools of 31 different folate species in E. coli to trimethoprim addition was quantitated by LC-MS/MS (Fig. 1). As expected, the immediate response of all dihydrofolate species (H2PteGlun) and their catabolized products (PteGlun, pABGlun) was to increase in concentration (often from previously undetectable levels). Similarly, all reduced folate species (H4PteGlun, 5,10-methylene-H4PteGlun, 5-methyl-H4PteGlun, and the analytically indistinguished species 5-formyl-H4PteGlun and 10-formyl-H4Pte- Glun) initially decreased in concentration. However, reduced monoand diglutamates increased in concentration from 20 min after trimethoprim addition onward, reaching levels yet higher than during exponential growth. This contrasted markedly with the reduced polyglutamates, which fell to at least ten-fold and often ≥100-fold below levels in exponentially growing cells. Despite the rapid and large concentration changes in individual folate species, the total folate pool changed in concentration only slowly (Supplementary Fig. 1 online). To confirm that these changes in folate pools were due to the drug and not due to extraction procedures (that is, centrifugation), the experiment was repeated with E. coli growing on filters on top of an agarosemedium support. This filter-culture approach enables fast quenching of metabolism7,31. The results (Supplementary Fig. 2 online) show the same qualitative behaviors in folate pools after DHFR inhibition by trimethoprim.

Figure 1.

Changes in folate pools with the addition of trimethoprim (4 μg ml−1). As expected, the DHFR inhibitor caused an overall increase in oxidized folates and a decrease in reduced folates. Surprisingly, reduced mono- and diglutamate species increased in concentration after an initial decrease. The x axis represents minutes after drug addition, and the y axis represents μM concentrations on a log scale. The error bars show +1 s.e.m. (n = 3 independent experiments).

The surprising pattern of increasing pool sizes of reduced monoand diglutamate species during trimethoprim treatment suggested two potential hypotheses: (i) depletion of reduced folate polyglutamate pools was resulting in a compensatory increase in de novo folate synthesis, leading to increased concentrations of reduced mono- and diglutamate species, or (ii) trimethoprim treatment was impairing, through a previously unknown mechanism, conversion of these species into folate polyglutamates, leading to their accumulation.

DHFR inhibition impairs FP-γ-GS activity

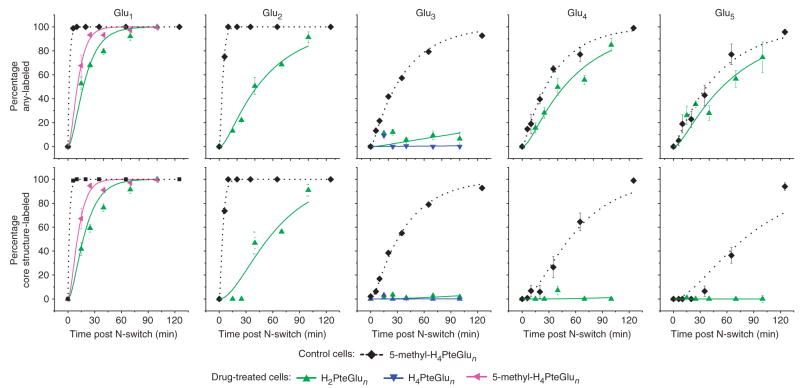

To determine the cause of the unexpected increase in reduced monoand diglutamates in response to DHFR inhibition, we conducted 15N flux profiling in cells treated with trimethoprim for 15 min (Fig. 2). Two values are reported for each time point: the fraction of folates containing greater than or equal to one 15N atom (any labeling), and the fraction of folates containing greater than or equal to one 15N atom in the pteroate portion of the molecule (core structure labeling). These two classifications (based on MS/MS data) differentiate newly synthesized folates (which show core structure labeling) from folates that have only undergone glutamate tail extension during the labeling period.

Figure 2.

Probing folate fluxes in the presence of trimethoprim. Trimethoprim treatment decreases flux through folylpoly-γ-glutamate synthetase (FP-γ-GS) but does not affect flux through folylpoly-α-glutamate synthetase (FP-α-GS). Control E. coli cells were grown in 14N medium and then switched to 15N medium. Drug-treated cells were grown in 14N medium, treated with 4 μg ml−1 trimethoprim for 15 min, and then switched to 15N medium also containing 4 μg ml−1 trimethoprim. The x axis represents minutes after N-switch. In the top row, the y axis represents the percent of the indicated folate species containing greater than or equal to one 15N atom (any-labeled). In the bottom row, the y axis represents the percent containing greater than or equal to one 15N atom in the pteroate portion of the molecule (core structure-labeled). Error bars show ±1 s.e.m. (n = 3 independent experiments). Curves represent a fit of the data to equations presented previously7 as described in the Methods.

Compared with folates in control cells, those in drug-treated cells were more slowly labeled, with passage of new core structures to folates with ≥3 glutamates essentially blocked. Quantitative analysis of the labeling kinetics can be used to estimate absolute fluxes and reveals moderately decreased de novo folate biosynthetic flux (that is, into folate monoglutamates) with DHFR inhibition: 2.8 ± 0.1 μMmin−1 in control cells and 1 ± 0.1 μM min−1 in drug-treated cells. In contrast, flux into folate triglutamates was indistinguishable from monoglutamate flux in control cells (2.8 μM min−1) but was negligible in drugtreated cells (<0.1 μM min−1). This flux pattern suggests that the increasing concentration of folate mono- and diglutamate species in response to drug treatment is due to impaired efflux to species with longer glutamate tails.

Notably, whereas folate triglutamates never became labeled in drugtreated cells, folate tetra- and pentaglutamate species did become labeled (with similar kinetics as in control cells), with the labeling restricted to their glutamate tails (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 3 online). Quantitative analysis of the labeling kinetics revealed a flux of 0.6 ± 0.1 μMmin−1 through folate tetraglutamates and a flux of 0.1 ± 0.04 μM min−1 through folate pentaglutamates in both control and drug-treated cells. As second and third glutamates are γ-linked and added by the enzyme FP-γ-GS, whereas further glutamates are α-linked and added by the enzyme FP-α-GS, this pattern of labeling is consistent with specific inhibition of FP-γ-GS but not FP-α-GS activity in the trimethoprim-treated cells.

In both trimethoprim-treated and control cells, all oxidation/reduction and one-carbon states of a given glutamate chain length were labeled with indistinguishable kinetics, which is consistent with oxidation/reduction and one-carbon reactions being markedly faster than glutamate chain extension reactions in both cases (Supplementary Fig. 4 online; see also Fig. 2).

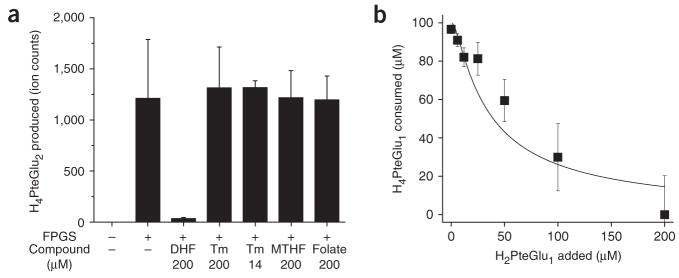

FP-γ-GS is blocked by dihydrofolate

The finding of impaired FP-γ-GS flux in trimethoprim-treated cells raised the question of the mechanism of the flux inhibition. Potential mechanisms included direct inhibition of FP-γ-GS by trimethoprim or inhibition by an endogenous compound that accumulates in response to DHFR inhibition. Biochemical assays of FP-γ-GS activity revealed no direct effect of trimethoprim but strong blockade by dihydrofolate, the endogenous substrate of DHFR (Fig. 3a). Inclusion of DHF (H2PteGlu1) in an assay for addition of glutamates to H4PteGlu1 by purified FP-γ-GS resulted in markedly reduced consumption of H4PteGlu1 even at low concentrations of DHF (Ki ≈ 3.1 μM, Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

DHF inhibits FP-γ-GS activity, as determined by in vitro FP-γ-GS assays. (a) DHF (H2PteGlu1) inhibits FP-γ-GS activity, but trimethoprim (Tm), 5-methyl-H4PteGlu1 (MTHF) and folate (PteGlu1) do not. H4PteGlu2 production was measured as peak intensity from LC-MS/MS analysis. (b) Dosedependent inhibition of FP-γ-GS activity by DHF. H4PteGlu1 consumption was measured as peak intensity from LC-MS/MS analysis. The line indicates a fit to competitive Michaelis-Menten kinetics with Ki = 3.1 μM. Error bars show ±1 s.e.m. (n = 3 independent experiments).

Inhibition of FP-γ-GS explains in vivo folate dynamics

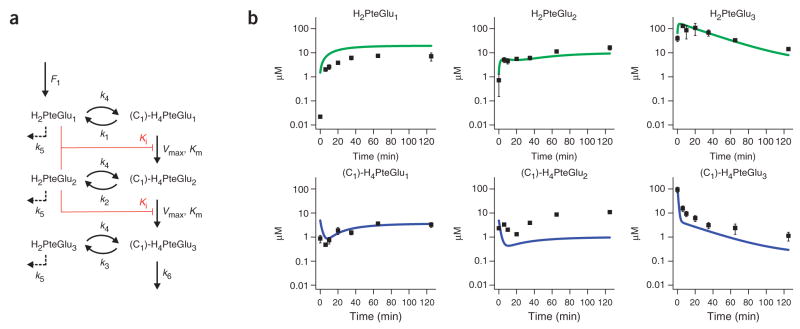

To determine whether the observed inhibition of FP-γ-GS by dihydrofolate could account for the complex, biphasic responses of numerous intracellular folates to DHFR inhibition, we developed an ordinary differential equation (ODE) model of folate biosynthetic metabolism. A schematic of the model is shown in Figure 4a. The model simulates reactions corresponding to folate oxidation/reduction, glutamate tail extension (by FP-γ-GS and FP-α-GS as appropriate) and folate degradation (from the oxidized state). Onecarbon transfer reactions are not explicitly considered, as the observed flux data (Supplementary Fig. 4) indicate that they are uniformly faster than the glutamate chain extension reactions of interest. All simulated reactions are assumed to be first order with respect to their folate substrates, except for the pivotal FP-γ-GS reactions, which are modeled as Michaelis-Menten forms with competitive inhibition by H2PteGlu1 and H2PteGlu2 (similar results are obtained assuming inhibition by H2PteGlu1 only). All enzyme concentrations were assumed to be constant. Though these simplifications are likely not fully accurate, they minimize nonlinear interactions among free parameters that could result in a model matching the data through mechanisms other than the hypothesized one.

Figure 4.

Computational modeling of cellular folate dynamics. (a) Model schematic. The model simulates reactions corresponding to folate oxidation/reduction, glutamate tail extension (by FP-γ-GS and FP-α-GS as appropriate) and degradation (from the oxidized state). One-carbon transfer reactions are not explicitly considered, as the observed flux data (Supplementary Fig. 4) indicate that they are uniformly faster than the glutamate chain extension reactions of interest. All simulated reactions were assumed to be first order with respect to their folate substrates, except for the pivotal FP-γ-GS reactions, which were modeled as Michaelis-Menten forms with competitive inhibition by H2PteGlu1 and H2PteGlu2 (similar results were obtained assuming inhibition by H2PteGlu1 only). The script is supplied in the Supplementary Methods. (b) The computational model shows the same qualitative behaviors as the experimental data. The (C1)-H4PteGlun data represent the sum of all measured reduced folates containing n glutamates. Error bars show ±1 s.e.m. (n = 3 independent experiments).

The de novo folate biosynthetic rate F1 was fixed, based on the flux profiling results, at 2.8 μM min−1 in control cells and 1 μM min−1 in drug-treated cells. The first-order rate constant k3 was estimated based on the thymidylate synthase (TS) flux known to be required to support DNA replication, and on the assumption that 5,10-methylene- H4PteGlu3 (the most abundant and preferred folate substrate32) is the primary folate feeding this reaction (fluxTS ≈ k3 × pool size(C1)-H4PteGlu3). The experimentally observed ratio of DHF triglutamate to all reduced triglutamate species was then used to determine k4 based on the steady state assumption (k3 × pool size(C1)-H4PteGlu3 ≈ k4 × pool sizeH2PteGlu3). The effect of adding trimethoprim was modeled as a decrease in k4 from 2 min−1 to 0.03 min−1 based on the observed oxidized-to-reduced folate triglutamate ratio in control versus drug-treated cells. Knowledge of k4 enabled calculation of k1 and k2 (k1 × pool size(C1)-H4PteGlu1 ≈ k4 × pool sizeH2PteGlu1). This calculation assumes that k4 is similar for DHF mono-, di- and triglutamates. It yields k3 > k2 > k1, which is consistent with the biochemically observed preference of TS for 5,10-methylene-H4PteGlu3 (ref. 32). Experimental determination of the flux from triglutamates to tetraglutamates via FP-α-GS was used to determine k6 (fluxFP-α-GS ≈ k6 × pool size(C1)-H4PteGlu3). Km and Ki for the FP-γ-GS reactions were determined biochemically, leaving only two free parameters, k5 and Vmax.

Manual adjustment of these two parameters resulted in the output of the model (Fig. 4b) generally matching the experimentally observed patterns in Figure 1. Agreement was obtained for a wealth of complex dynamics, including the unexpected experimental pattern of initial decrease followed by subsequent increase in reduced mono- and diglutamate species. Reduced triglutamate species decrease monotonically with drug treatment in the model, as observed experimentally. DHF mono- and diglutamate species increase monotonically with drug treatment, again matching experimental observations. Finally, DHF triglutamate species increase initially with drug treatment and then decrease ~ 15 min after drug addition in both the model and experimental data. Each of these behaviors is robust to five-fold increases or decreases in k5 and Vmax.

The different behaviors of the total diglutamate pool (sum of oxidized and reduced forms, increased) and total triglutamate pool (decreased) are accounted for by efflux from diglutamates to triglutamates being impaired by DHF inhibition of FP-γ-GS, whereas efflux from triglutamates is not, as it is catalyzed by FP-α-GS. These modeling results suggest that our proposed mechanism can in large part account for the complex dynamics in folate pools following trimethoprim treatment.

DISCUSSION

Improvements in the ability to quantitate metabolites by LC-MS/MS hold promise for advancing pharmacology. Important applications include drug metabolism33, biomarker discovery3 and personalization of therapy34. Here we investigated another potential application: deepening understanding of the molecular mechanisms of drug action.

A capability of LC-MS/MS that promises to be particularly useful in this regard is the ability to differentiate individual chemical species within a class of structurally related metabolites. Folates exemplify this: the core of folates can exist in different oxidation and one-carbon modification states, which can be paired with glutamate tails of various lengths. Prior chromatographic methods enabled measurement of either the distribution of glutamate tail lengths (without regard to oxidation and one-carbon modification states)24,25 or of oxidation and one-carbon modification states (without regard to glutamate tail length)2. Recent LC-MS/MS methods bridge this information gap by allowing for direct measurement of individual species.

Individual folate measurements revealed an unexpected trend after treatment of E. coli with trimethoprim: even though DHFR was blocked (causing a shift toward more oxidized folates overall), reduced folates with short glutamate tails surprisingly increased. Increases in metabolite concentration can arise from increased production or decreased consumption of the metabolite. Kinetic flux profiling—which to our knowledge is the first method capable of quantitating fluxes within the folate pathway—clearly differentiated these alternatives: flux from short-tail to long-tail glutamates was blocked upon trimethoprim treatment. Once flux profiling identified this blockade, identifying the responsible molecular entity (DHF that had accumulated in response to trimethoprim treatment) was readily achieved via standard biochemical approaches.

The observation that DHF is an inhibitor of FP-γ-GS in E. coli35 is noteworthy in light of related findings in mammalian systems. In human MCF-7 breast cells, AICAR transformylase is inhibited by DHF species that accumulate in response to methotrexate treatment36,37. Additionally, DHF species have been reported to inhibit pig liver methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase38 as well as Lactobacillus casei and human TS (refs. 39,40). To our knowledge, inhibition of folylpolyglutamation enzymes (in any species) or Enterobacteriaceae enzymes (of any sort) by DHF in live cells has not been previously reported.

The finding that DHF, which accumulates in response to DHFR inhibition, is itself an enzyme inhibitor in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes leads to the concept of a domino effect—a cascade in which direct pharmacological inhibition of one enzyme results in accumulation of the enzyme’s substrate, which then inhibits additional enzymes. Such a cascade of enzyme inhibition could in theory propagate yet further, just as the tumbling of one domino can lead to tumbling of many others downstream. In cells, the propagation occurs via natural interconnections between endogenous metabolites (for example, the natural role of DHF as both the substrate of DHFR and an inhibitor of FP-γ-GS in E. coli). The requisite inhibitory connections could arise either by coincidence (the absence of selective pressure to avoid them) or through mechanisms of regulation that are beneficial to the cell harboring them37,38,41.

Notably, the observed domino effect in E. coli was sufficient to explain the complex dynamics of folate pools following trimethoprim addition, as revealed by a quantitative, chemical kinetic model of the system. Despite the clinical importance of antifolate drugs and growing interest in quantitative modeling of one-carbon metabolism42,43, we are unaware of other efforts to model folate polyglutamation reactions or their modulation by pharmacological agents.

Metabolite concentration and flux analysis by LC-MS/MS, especially when interpreted via quantitative models, holds great promise for more completely elucidating the events triggered by pharmacological therapy. Such improved knowledge should ultimately be useful for guiding future efforts to develop improved therapeutics, and for making the best use of existing agents.

METHODS

Chemicals and reagents

Trimethoprim (≥98%), L-ascorbic acid (≥99.0%), dihydrofolate (approximately 90%), tetrahydrofolate (approximately 70%) and all media components were from Sigma-Aldrich. Ammonium acetate (99.4%) was from Mallinckrodt Chemicals, and ammonium hydroxide solution (29.73%) was from Fisher Scientific. 15N-ammonium chloride and 99.9% U-12C-glucose were from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories. Dimethyl sulfoxide (ACS reagent grade) was from MP Biomedicals, Inc. HPLC-grade water, acetonitrile and methanol (OmniSolv; EMD Chemical) were from VWR International. Folate polyglutamate standards were from Schircks Laboratories.

Microbial culture conditions and extraction

E. coli K-12 strain NCM3722 was grown at 37 °C in a minimal salts medium44 with 10 mM ammonium chloride as the nitrogen source and 0.4% glucose as the carbon source. To generate folate extracts, bacteria were separated from the medium by centrifugation. Immediately upon completion of spin, the supernatant was discarded and metabolic activity in the pellet was quenched by addition of 240 μl of extraction solvent (80:20 methanol:water + 0.1% ascorbic acid + 20 mM ammonium acetate, −75 °C, prepared fresh daily) and extracted serially with extraction solvent. Experimental manipulations (trimethoprim addition, flux profiling) were conducted at late log phase (A650 ~ 0.5). For an exemplary growth curve, see Supplementary Figure 5 online.

Nitrogen-switch experiments

Folate fluxes were monitored based on the assimilation of isotope-labeled ammonia into intracellular folates. Cells were transferred into 15N-ammonia by centrifugation and resuspension in labeled medium. Metabolism was quenched and folates extracted at distinct time points. As the M+1 peaks containing a single 15N atom are informative regarding folate dynamics, U-12C-glucose (99.9%) was used as the carbon source for these studies to minimize M+1 isotopic peaks on the MS spectrum resulting from naturally occurring 13C (1% natural abundance), which otherwise complicates analysis. For drug-treated cells, trimethoprim was added 15 min before the nitrogen switch.

Kinetic flux profiling7 was used to estimate flux through folate pools. In control cells, 5-methyl-H4PteGlun (n = 1–5) data were used for flux calculations, as they are the most abundant folate species. In drug-treated cells, 5-methyl-H4PteGlu1 and H2PteGlun (n = 2–5) data were used for flux calculations, as they are the most abundant folate species after drug treatment. Flux through each folate polyglutamate species was calculated as described previously7:

| (1) |

where is the total pool of a folate species with n glutamates in its tail, and fn is the flux through that folate species. To determine the kn for each species, labeling data was fit to the following equation:

| (2) |

where is the unlabeled form of a folate species with n glutamates in its tail, and is a single exponential fit to the available data for Xn–1 (the precursor to Xn). For core structure labeling, the precursor to Xn was considered to be folate species with one less glutamate in their tail. For any labeling, the precursor to Xn was considered to be glutamate. In control cells, de novo folate flux (into Glu1, Glu2 and Glu3 species, which are approximately equal at steady state) was determined using 5-methyl-H4PteGlu3 data. Analysis of any labeling and core structure labeling both gave the same flux value. In drug-treated cells, in which flux into polyglutamates was impaired, 5-methyl-H4PteGlu1 anylabeling data were used to determine the de novo folate flux, and H2PteGlu3 any-labeling data were used to determine the FP-γ-GS flux into triglutamates. In both control and drug-treated cells, 5-methyl-H4-PteGlu4 and Glu5 anylabeling data were used to determine FP- α-GS fluxes. Error estimates for fluxes were determined based on the standard error of kn from the curve fitting.

LC-MS/MS analysis

Folates were measured using LC-MS/MS as previously described28. Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) scan events used in this study (including those for 15N-labeled species) are presented in Supplementary Table 1 online (which also includes details on the LC-MS/MS method used). To account for the different ionization of folates with varying numbers of glutamates, raw counts from LC-MS/MS were corrected using conversion factors generated from studies with standards. For details, see Supplementary Methods online.

In vitro assay for activity of recombinant FP-γ-GS

Biochemical assays were performed using a His-tagged version of E. coli folC with H4PteGlu1 as the folate substrate and saturating glutamate and ATP. The Km for H4PteGlu1 and Ki for H2PteGlu1 (which was treated as a competitive inhibitor) were determined by titrating their respective concentrations and measuring the associated enzymatic reaction rate. For details, see Supplementary Methods.

Network model of in vivo folate data

The model assumes constant de novo folate biosynthesis (forming H2PteGlu1 at a constant rate of 2.8 μM min−1 in control cells and 1.0 μMmin−1 in drug-treated cells) and simulates reactions corresponding to folate oxidation/reduction, glutamate tail extension by FP-α-GS, and degradation (from the oxidized state) as pseudo-first-order reactions. The pivotal FP-γ-GS reactions were modeled as Michaelis-Menten forms with competitive inhibition by H2PteGlu1 and H2PteGlu2. The script (written in R programming language for statistical computing) is supplied in the Supplementary Methods.

Km (50 μM) and Ki (3.1 μM) values were determined experimentally from in vitro FP- γ-GS assays. The rate constant for conversion of reduced triglutamates (k3) was calculated to be 1.2 min−1 by dividing the flux through TS in exponentially growing E. coli (75 μMmin−1; from a previous study45 based on the amount of thymidine required for replication during optimally efficient growth at the experimentally observed doubling time of ~90 min) by the total pool of reduced triglutamates (65 μM). k4 was determined as described in the Results to be 2 min−1 in control cells and 0.03 min−1 in drug-treated cells. Similarly, k1 and k2 were determined to be 0.1 min−1 and 0.6 min−1, respectively. k6 was calculated to be 0.006 min−1 by dividing flux from triglutamates to tetraglutamates by substrate concentration ( ). k5 (0.03 min−1), the sum of slow oxidation of dihydrofolates to folates and slow catabolism to pABGlu1–3, and Vmax of FP-γ-GS (60 μM min−1) were selected manually to mimic experimental behavior.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) Center for Quantitative Biology at Princeton University (P50GM071508). Additional support came from the Beckman Foundation, the US National Science Foundation (NSF) Dynamic Data Driven Applications Systems grant CNS-0540181, the American Heart Association grant 0635188N, NSF Career Award MCB-0643859 and the NIH grant AI078063 (to J.D.R.).

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary information and chemical compound information is available on the Nature Chemical Biology website.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Y.K.K. and J.D.R. designed experiments, analyzed data and wrote the paper. W.L. developed the LC-MS/MS method. E.M. wrote the computer code. N.K. and A.B. contributed to biochemical assays of FP-γ-GS activity. A.B. edited the paper.

Published online at http://www.nature.com/naturechemicalbiology/

Reprints and permissions information is available online at http://npg.nature.com/reprintsandpermissions/

References

- 1.Voet D, Voet JG. In: Biochemistry. Harris D, Fitzgerald P, editors. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; Hoboken, New Jersey, USA: 2004. pp. 482–486. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quinlivan EP, McPartlin J, Weir DG, Scott J. Mechanism of the antimicrobial drug trimethoprim revisited. FASEB J. 2000;14:2519–2524. doi: 10.1096/fj.99-1037com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sabatine MS, et al. Metabolomic identification of novel biomarkers of myocardial ischemia. Circulation. 2005;112:3868–3875. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.569137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bajad SU, et al. Separation and quantitation of water soluble cellular metabolites by hydrophilic interaction chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 2006;1125:76–88. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2006.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Werf MJ, Overkamp KM, Muilwijk B, Coulier L, Hankemeier T. Microbial metabolomics: toward a platform with full metabolome coverage. Anal Biochem. 2007;370:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sauer U. Metabolic networks in motion: 13C-based flux analysis. Mol Syst Biol. 2006;2:62. doi: 10.1038/msb4100109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yuan J, Fowler WU, Kimball E, Lu W, Rabinowitz JD. Kinetic flux profiling of nitrogen assimilation in Escherichia coli. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:529–530. doi: 10.1038/nchembio816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noh K, et al. Metabolic flux analysis at ultra short time scale: isotopically nonstationary 13C labeling experiments. J Biotechnol. 2007;129:249–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2006.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bushby SR, Hitchings GH. Trimethoprim, a sulphonamide potentiator. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1968;33:72–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1968.tb00475.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reeves DS. Sulphamethoxazole-trimethoprim: the first two years. J Clin Pathol. 1971;24:430–437. doi: 10.1136/jcp.24.5.430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Then RL. History and future of antimicrobial diaminopyrimidines. J Chemother. 1993;5:361–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gangjee A, Jain HD, Kurup S. Recent advances in classical and non-classical antifolates as antitumor and antiopportunistic infection agents: part I. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2007;7:524–542. doi: 10.2174/187152007781668724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schnell JR, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Structure, dynamics, and catalytic function of dihydrofolate reductase. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2004;33:119–140. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.33.110502.133613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedkin M. Thymidylate synthetase. Adv Enzymol. 1973;38:235–292. doi: 10.1002/9780470122839.ch5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pogolotti AL, Santi DV. In: Bioorganic Chemistry. van Tamelen EE, editor. Vol. 1. Academic Press; New York: 1977. pp. 277–311. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Danenberg PV. Thymidylate synthetase - a target enzyme in cancer chemotherapy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1977;473:73–92. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(77)90001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Santi DV, Danenberg PV. In: Folates and Pterins. Blackley RL, Benkovic SJ, editors. Vol. 1. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1984. pp. 345–398. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carreras CW, Santi DV. The catalytic mechanism and structure of thymidylate synthase. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:721–762. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.003445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGuire JJ, Bertino JR. Enzymatic synthesis and function of folylpolyglutamates. Mol Cell Biochem. 1981;38:19–48. doi: 10.1007/BF00235686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGuire JJ, Coward JK. In: Folates and Pterins. Blackley RL, Benkovic SJ, editors. Vol. 1. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1984. pp. 135–190. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shane B. Folylpolyglutamate synthesis and role in the regulation of one-carbon metabolism. Vitam Horm. 1989;45:263–335. doi: 10.1016/s0083-6729(08)60397-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lowe KE, et al. Regulation of folate and one-carbon metabolism in mammalian cells. II Effect of folylpoly-gamma-glutamate synthetase substrate specificity and level on folate metabolism and folylpoly-gamma-glutamate specificity of metabolic cycles of one-carbon metabolism. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:21665–21673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quinlivan EP, Hanson AD, Gregory JF. The analysis of folate and its metabolic precursors in biological samples. Anal Biochem. 2006;348:163–184. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferone R, Hanlon MH, Singer SC, Hunt DF. α-Carboxyl-linked glutamates in the folylpolyglutamates of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:16356–16362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferone R, Singer SC, Hunt DF. In vitro synthesis of α-carboxyl-linked folylpolyglutamates by an enzyme preparation from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:16363–16371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bognar AL, Osborne C, Shane B, Singer SC, Ferone R. Folylpoly-gammaglutamate synthetase-dihydrofolate synthetase. Cloning and high expression of the Escherichia coli folC gene and purification and properties of the gene product . J Biol Chem. 1985;260:5625–5630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garratt LC, et al. Comprehensive metabolic profiling of mono- and polyglutamated folates and their precursors in plant and animal tissue using liquid chromatography/negative ion electrospray ionisation tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2005;19:2390–2398. doi: 10.1002/rcm.2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu W, Kwon YK, Rabinowitz JD. Isotope ratio-based profiling of microbial folates. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2007;18:898–909. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scott JM. In: Folates and Pterins. Blackley RL, Benkovic SJ, editors. Vol. 1. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1984. pp. 307–327. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suh JR, Oppenheim EW, Girgis S, Stover PJ. Purification and properties of a folate-catabolizing enzyme. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:35646–35655. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005864200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brauer MJ, et al. Conservation of the metabolomic response to starvation across two divergent microbes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:19302–19307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609508103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kisliuk RL. Pteroylpolyglutamates. Mol Cell Biochem. 1981;39:331–345. doi: 10.1007/BF00232583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hsieh Y. HPLC-MS/MS in drug metabolism and pharmacokinetic screening. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2008;4:93–101. doi: 10.1517/17425255.4.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clayton TA, et al. Pharmaco-metabonomic phenotyping and personalized drug treatment. Nature. 2006;440:1073–1077. doi: 10.1038/nature04648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Masurekar M, Brown GM. Partial purification and properties of an enzyme from Escherichia coli that catalyzes the conversion of glutamic acid and 10-formyltetrahydropteroylglutamic acid to 10-formyltetrahydropteroyl-gamma-glutamylglutamic acid. Biochemistry. 1975;14:2424–2430. doi: 10.1021/bi00682a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allegra CJ, Drake JC, Jolivet J, Chabner BA. Inhibition of phosphoribosylaminoimidazolecarboxamide transformylase by methotrexate and dihydrofolic acid polyglutamates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:4881–4885. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.15.4881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Allegra CJ, Hoang K, Yeh GC, Drake JC, Baram J. Evidence for direct inhibition of de novo purine synthesis in human MCF- 7 breast cells as a principal mode of metabolic inhibition by methotrexate. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:13520–13526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matthews RG, Baugh CM. Interactions of pig liver methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase with methylenetetrahydropteroylpolyglutamate substrates and with dihydropteroylpolyglutamate inhibitors. Biochemistry. 1980;19:2040–2045. doi: 10.1021/bi00551a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kisliuk RL, Gaumont Y, Baugh CM. Polyglutamyl derivatives of folate as substrates and inhibitors of thymidylate synthetase. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:4100–4103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dolnick BJ, Cheng YC. Human thymidylate synthetase. II Derivatives of pteroylmono- and -polyglutamates as substrates and inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:3563–3567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matthews RG, Haywood BJ. Inhibition of pig liver methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase by dihydrofolate: some mechanistic and regulatory implications. Biochemistry. 1979;18:4845–4851. doi: 10.1021/bi00589a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reed MC, Nijhout HF, Sparks R, Ulrich CM. A mathematical model of the methionine cycle. J Theor Biol. 2004;226:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reed MC, et al. A mathematical model gives insights into nutritional and genetic aspects of folate-mediated one-carbon metabolism. J Nutr. 2006;136:2653–2661. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.10.2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gutnick D, Calvo JM, Klopotowski T, Ames BN. Compounds which serve as the sole source of carbon or nitrogen for Salmonella typhimurium LT-2. J Bacteriol. 1969;100:215–219. doi: 10.1128/jb.100.1.215-219.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ibarra RU, Edwards JS, Palsson BO. Escherichia coli K-12 undergoes adaptive evolution to achieve in silico predicted optimal growth. Nature. 2002;420:186–189. doi: 10.1038/nature01149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.