Abstract

Prior research has yielded discrepant findings regarding change in caregiver burden or depressive symptoms after institutionalization of persons with dementia. However, earlier studies often included small post-placement samples. In samples of 1,610 and 1,116 dementia caregivers with up to 6-months and 12-months post-placement data, respectively, this study identified predictors of change in caregiver burden and depressive symptoms following nursing home admission (NHA). Descriptive analyses found that caregivers reported significant and considerable decreases in burden in the 6- and 12-month post-placement panels. A number of variables predicted increased burden and depressive symptoms in the 6- and 12-month post-placement panels. Pre-placement measures of burden and depressive symptoms, site (Florida), overnight hospital use, and spousal relationship appear to result in impaired caregiver well-being following NHA. Incorporating more specific measures of stress, considering the influence of health-related transitions, and coordinating clinical strategies that balance caregivers’ needs for placement with sustainability of at-home care are important challenges for future research.

Keywords: Caregiving, Alzheimer’s disease, Long-term care, Institutionalization, Nursing home entry, Informal long-term care, Depression

Longitudinal investigations have found that caregiver depressive symptoms and burden are present following a care recipient’s nursing home admission (NHA) (Aneshensel, Pearlin, Mullan, Zarit, & Whitlatch, 1995; Gaugler, Pot, & Zarit, 2007; Schulz et al., 2004). Less clear are those factors that mitigate or exacerbate these adverse caregiver effects after NHA. Using a data source that included over 1,000 dementia caregivers who provided information up to 12 months after institutionalization, the present study examined risk factors associated with increases in burden or depressive symptoms immediately prior to and after NHA. The identification of variables that influence change in emotional distress and well-being after NHA is important, as burden and depressive symptoms are associated with negative health outcomes throughout the course of caregiving (Pinquart & Sörensen, 2003b; Schulz, O’Brien, Bookwala, & Fleissner, 1995; Schulz & Beach, 1999).

Background

Family caregivers incur substantial emotional, physical, and financial costs in their attempts to avoid NHA of a relative (Covinsky et al., 2001; Haley, 1997; Langa et al., 2001; Moore, Zhu, & Clipp, 2001). These efforts contribute to a high risk of burden and depressive symptoms (Parks & Novielli, 2000; Schulz et al., 1995), poor health outcomes (Schulz et al., 1995; Vitaliano, Zhang, & Scanlan, 2003), lower quality of life (Coen, O’Boyle, Coakley, & Lawlor, 2002), and increased mortality among caregivers (Schulz & Beach, 1999) which can eventually lead to NHA of care recipients (Gaugler, Kane, Kane, Clay, & Newcomer, 2003; Yaffe et al., 2002). In a recent systematic review of the literature, a number of care recipient variables were found to precipitate institutionalization in persons suffering from cognitive impairment (Gaugler, Yu, Krichbaum, & Wyman, 2009). Severity of cognitive impairment, an Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis, functional dependence (i.e., reliance on others to complete activities of daily living), depressive symptoms, and behavior problems in persons with dementia emerged as consistent predictors of NHA. A key finding of the systematic review was that caregiving indicators were as consistent in their prediction of NH placement as care recipient indicators. Caregivers who reported greater stress because of care responsibilities, caregivers who felt “trapped” in the caregiving role, and caregivers who indicated a greater desire to institutionalize the care recipient were all highly consistent in their increased risk for placement of their relatives. Interestingly, sociodemographic characteristics of the caregiver or care recipient (e.g., age, gender, kin relationship of caregiver to care recipient) were not consistent in their prediction of institutionalization (Gaugler et al., 2009). Among the highest quality studies included in this review was a secondary analysis of the Medicare Alzheimer’s Disease Demonstration Evaluation (MADDE), which is the source of data for the present study (Gaugler et al., 2003). In contrast to the overall conclusions of the systematic review, the analysis of MADDE found several sociodemographic characteristics of care recipients that were significant predictors of NHA including male gender, Caucasian race/ethnicity, greater age, Medicaid eligibility, and living alone (Gaugler et al., 2003; see also Yaffe et al., 2002).

A number of longitudinal studies suggest that caregiver stress and depressive symptoms remain stable or even increase following NHA (Aneshensel et al., 1995; Gaugler et al., 2007; Schulz et al., 2004; Whitlatch, Schur, Noelker, Ejaz, & Looman, 2001; Zarit & Whitlatch, 1992). It is important to note that these studies do not include comparison groups who continue to provide assistance at home. Other work suggests a pronounced decrease in caregiver burden or depressive symptoms after institutionalization when at-home caregiver comparison groups are included (e.g., Gaugler, Roth, Haley, & Mittelman, 2008).

Prior studies investigating predictors of caregiver burden or depressive symptoms after NHA are also inconsistent in their findings. Some report that behavior problems exhibited by the care recipient prior to NHA are linked to poor emotional and psychological outcomes for caregivers and less frequent family visits following institutionalization (Almberg, Grafstrom, Krichbaum, & Winblad, 2000; Gaugler, Leitsch, Zarit, & Pearlin, 2000; Majerovitz, 2007; Whitlatch et al., 2001). Other analyses find less consistent effects of behavior problems (Gaugler, Anderson, Zarit, & Pearlin, 2004; Tornatore & Grant, 2002). Several studies suggest that kin relationship influences caregiver well-being following NHA, with spouses indicating greater dissatisfaction with the NH environment and more depressive symptoms following placement (Gaugler et al., 2000; Schulz et al., 2004). Other studies report that emotional distress or psychological well-being after NHA does not differ significantly between spouses or adult children (Zarit & Whitlatch, 1992).

Research Objectives

There are discrepancies in the literature on how caregiver outcomes change following NHA. The first objective of the present study was to resolve these divergent findings. Previous longitudinal studies that followed care recipient-caregiver dyads before and after NHA included relatively small post-placement samples, making it difficult to detect any but the most substantial changes in outcomes for caregivers (Aneshensel et al., 1995; Gaugler et al., 2007, 2008; Schulz et al., 2004) (e.g., analyses of the Caregiver Stress and Coping Study, such as Aneshensel et al., 1995, had no more than 185 dementia caregivers available immediately after NHA; the Schulz et al. 2004 study included 180 dyads). The present study included over 1,000 dementia caregivers who provided up to 12 months of data after institutionalization. Of secondary interest was an examination of whether burden or depressive symptoms exhibited clinical change up to 6 and 12 months after institutionalization. A limitation of prior dementia caregiving research is the lack of clinical significance reported (Schulz et al., 2002).

The second objective of this study was to identify those variables that predict changes in caregiver burden and depressive symptoms following NHA. As summarized above, there are a handful of variables that appear to be associated with caregiver stress after institutionalization. The inconsistency of empirical findings makes it difficult to limit potential predictors of caregiver burden or depressive symptoms to a specific set of variables. For these reasons, the present study utilized an exploratory approach to identify those pre-placement indicators that influenced caregiver burden and depressive symptoms 6- and 12-months after a cognitively impaired care recipient’s NHA. The following domains of predictors, informed by prior research on NHA, were considered:

Sociodemographic and contextual characteristics

Several background characteristics of the caregiver and care recipient may influence stress or depressive symptoms of caregivers following NHA. As noted above, sociodemographic and contextual characteristics such as kin relationship of the caregiver to care recipient (i.e., spousal relationship), age, gender, the type and nature of living arrangements, ethnicity, socioeconomic characteristics of the caregiving household, and caregiving history (e.g., duration of care) may not only precipitate institutionalization but may also account for whether caregivers experience stress after NHA.

Care recipient dementia severity

Among the most consistent predictors of NHA in dementia are severity of cognitive impairment and frequency of behavior problems (Gaugler et al., 2009). Similarly, behavior problems prior to placement may continue to adversely affect caregivers after institutionalization (Almberg et al., 2000; Gaugler et al., 2000; Majerovitz, 2007; Whitlatch et al., 2001).

Care recipient functional dependency

Another consistent predictor of NHA in dementia is activity of daily living (ADL) dependence (Gaugler et al., 2009). In systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Gaugler, Duval, Anderson, & Kane, 2007; Gaugler et al., 2009), instrumental activities of daily living assistance (IADLs) appear to exert less robust effects on NH entry. However, IADLs were considered in this exploratory analysis to determine if they influenced change in caregiver burden or depressive symptoms after institutionalization since many of these tasks may be assumed by NH staff following placement (see Gaugler, 2005).

Resources

As operationalized in the present study, resources can include social support provided to the caregiver from other relatives and friends, support provided by formal services such as in-home help or adult day services, and personal health resources of the caregiver as embodied in caregivers’ subjective health and functional dependence. Some research suggests that help from family for specific tasks may delay NHA (Gaugler et al., 2000) while other studies have found that formal service utilization (such as adult day service use) has little to no effect on caregivers’ decisions to institutionalize (Lee & Cameron, 2004). Given these divergent findings, a range of resources were considered in our study of caregivers’ emotional and psychological distress after NHA.

Methods

The Medicare Alzheimer’s Disease Demonstration Evaluation

The present study relied on data obtained as part of a large multi-regional sample of persons with dementia, the Medicare Alzheimer’s Disease Demonstration Evaluation (MADDE; Newcomer, Spitalny, Fox, & Yordi, 1999). MADDE was conducted in eight communities between 1989 and 1994 and examined whether a combination of case management services and Medicare-covered home care benefits was effective in reducing caregiver burden and depressive symptoms and delaying NHA for cognitively impaired care recipients (for additional detail on MADDE see Newcomer et al., 1999). The following criteria governed participants’ inclusion in MADDE: all older adults (a) had a physician-certified diagnosis of an irreversible dementia, (b) were enrolled or eligible for Parts A and B of Medicare, (c) had service needs, and (d) resided at home in one of the eight MADDE catchment areas (Champaign, Illinois; Cincinnati, Ohio; Memphis, Tennessee; Miami, Florida; Parkersburg, West Virginia; Portland, Oregon, Rochester, New York; Minneapolis/St. Paul, Minnesota). Persons living in a NH or who were in a hospital at the time of application were ineligible. MADDE case management and any other supports provided to caregivers were terminated within 60 days following NHA. The caregiver was defined as the relative who provided the most assistance to the person with dementia throughout the course of MADDE. MADDE implemented an experimental research design with care recipients randomly assigned to either a treatment group eligible for the expanded Medicare case management benefit or a control group that did not receive the benefit but continued to receive usual care. Interviews were administered to caregivers by trained nurses and social workers every 6-months for 3 years and up to 12 months following NHA. The baseline interview was in-person. Semi-annual assessments and post-NHA interviews were conducted by telephone. The date of enrollment in MADDE was considered the care recipient’s baseline date.

Sample

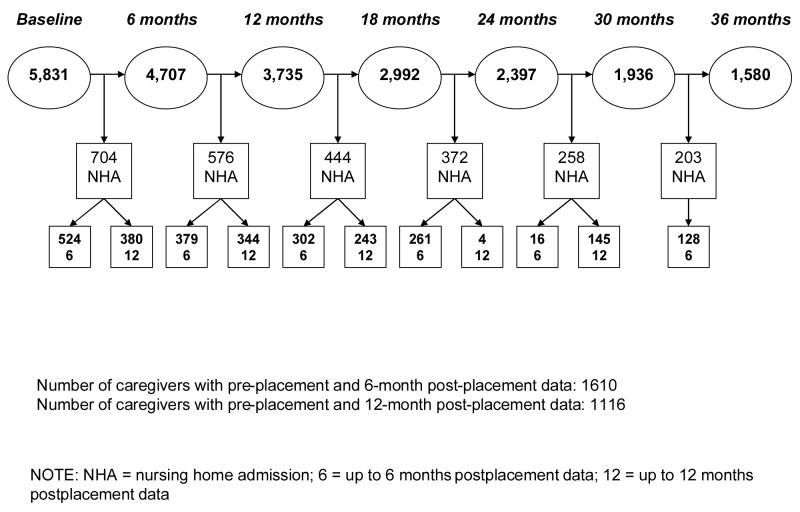

A total of 5,831 persons voluntarily enrolled in MADDE at baseline. Just over 40% (43.9%) of care recipients were permanently admitted to a NH at some time during the demonstration. There were 1,610 dementia caregivers who reported information on burden or depressive symptoms up to 6 months following NHA (the 6-month post-placement panel) and 1,116 caregivers with burden or depressive symptoms data up to 12 months after institutionalization (the 12-month post-placement panel). Figure 1 provides detail on the number of persons institutionalized during each 6-month interval. Pre-placement was defined as the measurement interval immediately prior to NHA.

Figure 1.

Institutionalization in the Medicare Alzheimer’s Disease Demonstration Evaluation.

A strength of MADDE was its classification of NH entries the caregiver indicated as “permanent.” Instances where persons with dementia returned home after short-stay NH entries (less than 60 days) were classified separately from permanent long-term care placements. In addition, institutionalization events resulting in death in the NH facility were classified as permanent. In the present study NH entry was considered for those stays MADDE classified as permanent (Miller, Newcomer, & Fox, 1999). There were 581 and 307 persons with dementia who died following NHA in the 6- and 12-month post-placement cohorts, respectively. Average time from NHA to death for care recipients was 387.71 days (SD = 240.74) in the 6-month post-placement cohort and 539.50 days (SD = 193.80) in the 12-month post-placement cohort. A handful of persons with dementia died either prior to 30 days (n = 6) or 60 days (n = 27) after institutionalization in the 6-month post-placement cohort. No care recipients died within 30 or 60 days after NHA in the 12-month post-placement cohort.

Although MADDE group assignment appeared to interact with several site variables to result in reduced caregiver burden and depressive symptoms in one site, prior published evaluations of MADDE concluded that the expanded Medicare benefit had little or no effect overall on time to NHA, caregiver burden, or caregiver depressive symptoms (Miller et al., 1999; Newcomer, Yordi, DuNah, Fox, & Wilkinson, 1999). For this reason, data from the treatment and control participants in MADDE were pooled to maximize sample size for the current analyses.

Measures

Descriptive information for the 6- and 12-month post-placement panels is included in Table 1. Baseline reliability coefficients are presented for the 6- and 12-month post-placement panels below.

Table 1.

Descriptive Information and Bivariate Comparison, 6-month (N = 1,610) and 12-month (1,116) Post-Placement Panels.

| M/% | SD | Range | M/% | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | ||||||

| Pre-placement burden | 13.76 | 7.06 | 0.00–28.00 | 13.92 | 6.91 | 0.00–28.00 |

| 6-month post- placement burden | 9.61 | 6.90 | 0.00–28.00 | 9.38 | 6.87 | 0.00–28.00 |

| 12-month post- placement burden | - | - | - | 7.04 | 6.13 | 0.00–27.00 |

| Pre-placement depressive symptoms | 4.69 | 3.55 | 0.00–15.00 | 4.70 | 3.49 | 0.00–15.00 |

| 6-month post-placement depressive symptoms | 4.17 | 3.74 | 0.00–15.00 | 4.04 | 3.69 | 0.00–15.00 |

| 12-month post-placement depressive symptoms | - | - | - | 3.79 | 3.68 | 0.00–15.00 |

| Sociodemographic and Contextual Characteristics | ||||||

| Site | ||||||

| Florida | 8.9% | 7.6% | ||||

| Illinois | 15.9% | 16.8% | ||||

| Minnesota | 21.9% | 22.0% | ||||

| New York | 13.2% | 14.4% | ||||

| Ohio | 14.7% | 16.2% | ||||

| Oregon | 9.6% | 8.4% | ||||

| Tennessee | 9.6% | 8.3% | ||||

| West Virginia | 6.1% | 6.2% | ||||

| CR is female* | 59.3% | 63.7% | ||||

| CR is Caucasian | 92.0% | 92.2% | ||||

| CR age | 71.47 | 7.62 | 30.63–102.10 | 78.83 | 7.41 | 47.03–97.06 |

| CR is Medicaid eligible* | 50.3% | 55.1% | ||||

| CR lives with CG | 73.7% | 72.5% | ||||

| MADDE treatment group assignment | 51.0% | 52.2% | ||||

| CG is female | 71.1% | 69.4% | ||||

| CG is spouse | 51.2% | 48.1% | ||||

| CG age | 63.56 | 14.42 | 23.00–100.00 | 63.01 | 14.31 | 25.00–100.00 |

| CG incomea | 5.81 | 2.91 | 1.00–11.00 | 5.90 | 2.91 | 1.00–11.00 |

| CG is employed | 33.1% | 33.8% | ||||

| CG educationb | 3.54 | 1.33 | 0.00–6.00 | 3.53 | 1.33 | 0.00–6.00 |

| Duration of care at baseline (in months) | 44.21 | 38.53 | 0.00–360.00 | 43.98 | 39.09 | 0.00–360.00 |

| Time to NHA from pre- placement (days)*** | 113.86 | 69.80 | 0.00–372.00 | 99.98 | 50.31 | 0.00–372.00 |

| Care Recipient Dementia Severity | ||||||

| MMSE at baseline | 14.29 | 7.89 | 0.00–30.00 | 14.08 | 8.14 | 0.00–30.00 |

| Pre-placement behavior problems | 9.67 | 4.06 | 0.00–19.00 | 9.74 | 4.01 | 0.00–19.00 |

| Care Recipient Functional Dependency | ||||||

| Pre-placement ADLs | 4.34 | 2.55 | 0.00–10.00 | 4.26 | 2.48 | 0.00–10.00 |

| Pre-placement IADLs | 7.13 | 1.20 | 0.00–8.00 | 7.10 | 1.20 | 1.00–8.00 |

| Pre-placement caregiving hours (typical week) | 74.67 | 61.43 | 0.00–988.00 | 74.66 | 68.03 | 0.00–988.00 |

| Pre-placement unmet needs | 2.92 | 4.31 | 0.00–18.00 | 3.02 | 4.36 | 0.00–18.00 |

| Resources | ||||||

| Pre-placement secondary caregiving hours (typical week) | 6.42 | 20.97 | 0.00–168.00 | 7.73 | 23.42 | 0.00–168.00 |

| Pre-placement chore service use (times) | 29.76 | 98.08 | 0.00–1300.00 | 30.44 | 107.52 | 0.00–1300.00 |

| Pre-placement personal care use (times) | 67.56 | 193.55 | 0.00–1456.00 | 77.26 | 210.83 | 00.00–1456.00 |

| Pre-placement adult day service use (days) | 19.74 | 37.06 | 0.00–120.00 | 20.74 | 38.00 | 0.00–120.00 |

| Pre-placement overnight hospital use (times) | 2.05 | 7.97 | 0.00–120.00 | 2.23 | 9.18 | 0.00–120.00 |

| Chore service use during NHA (times) | 14.82 | 52.33 | 0.00–650.00 | 16.07 | 57.90 | 0.00–812.00 |

| Personal care use during NHA (times) | 42.03 | 124.84 | 0.00–1176.00 | 44.57 | 131.19 | 00.00–1176.00 |

| Adult day service use during NHA (days) | 11.85 | 24.50 | 0.00–119.00 | 11.88 | 24.37 | 0.00–119.00 |

| Overnight hospital use during NHA (times) | 8.12 | 14.64 | 0.00–150.00 | 8.38 | 15.67 | 0.00–150.00 |

| CG pre-placement self- reported healthc | 2.05 | .83 | 1.00–4.00 | 2.05 | .82 | 1.00–4.00 |

| CG pre-placement ADLs | .24 | .69 | 0.00–5.00 | .22 | .63 | 0.00–5.00 |

| CG pre-placement IADLs | .78 | 1.51 | 0.00–8.00 | .74 | 1.48 | 0.00–8.00 |

NOTE: M = mean; SD = standard deviation; CR = care recipient; CG = caregiver; NHA = nursing home admission; ADL = activities of daily living; IADLs = instrumental activities of daily living; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination

1 = under $4,999 to 11 = $50,000 and above (each item response reflects a range of $5,000 upward in income)

0 = No formal schooling; 1 = elementary school; 2 = some high school; 3 = high school or equivalent; 4 = some college; 5 = college graduate; 6 = post graduate

1 = excellent; 2 = good; 3 = fair; 4 = poor

p < .001;

p < .01;

p < .05

Outcomes

The outcome variables were caregiver burden, measured with a 7-item short form of the Zarit Burden Interview in which symptoms are relevant for caregiving in home or NH settings (ZBI; Zarit, Reever, & Bach-Peterson, 1980; 6-month α = .89; 12-month α = .89) and caregiver depressive symptoms, measured with the 15-item Geriatric Depressive Symptoms scale (GDS) (Sheikh & Yesavage, 1986; 6-month α = .75; 12-month α = .75). The ZBI is widely used as a measure of caregiver stress in the dementia context (e.g., Gaugler, Kane, & Langlois, 2000; O’Rourke & Tuokko, 2003). The GDS is also widely used and numerous studies have linked high GDS scores to adverse health outcomes (Covinsky et al., 1999). The ZBI and GDS measures were assessed at all pre-placement and post-placement study intervals.

Sociodemographic and contextual characteristics

Care recipient demographic variables included gender, race, age, and living arrangement. Caregiver demographics included gender, age, income, employment status, and education. Contextual variables included site/location of recruitment (Champaign, Illinois; Cincinnati, Ohio; Memphis, Tennessee; Miami, Florida; Parkersburg, West Virginia; Portland, Oregon, Rochester, New York; or Minneapolis/St. Paul, Minnesota), Medicaid status, whether the care recipient was assigned to the MADDE treatment or control condition, caregiver relationship to care recipient, and duration of care at entry into MADDE. Time from the pre-placement interview to the NHA date was also considered.

Care recipient dementia severity

Case managers administered the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975) to care recipients at baseline only (6-month α = .94; 12-month α = .94). This was used as an indicator of care recipient cognitive impairment. Care recipient behavior problems such as asking repetitive questions, being suspicious or accusative, or wandering/getting lost were assessed by caregivers on a 19-item measure, The Memory and Behavior Checklist, at pre-placement (Zarit, Orr, & Zarit, 1985; 6-month α = .77; 12-month α = .76).

Care recipient functional dependency

Care recipient functional variables included dependence on 10 ADL tasks (Katz, Ford, Moskowitz, Jackson, & Jaffe, 1963; 6-month α = .89; 12-month α = .88) and 8 IADL tasks (Lawton & Brody, 1969; 6-month α = .84; 12-month α = .83). The number of hours caregivers spent managing care recipient’s functional and cognitive needs in a typical week was assessed (primary informal caregiving hours). Unmet needs with respect to care recipients’ ADL and IADL limitations (i.e., not enough help indicated by the caregiver) were summed (6-month α = .87; 12-month α = .84).

Resources

Secondary caregiving hours were measured in pre-placement study interviews by asking respondents how many hours they typically received help from other family members or friends. Primary caregivers were also asked to identify, from a fixed list of options, the formal services they had used in the past 6 months and how often they relied on these services. Three community-based services accounted for the majority of community-based care use in MADDE prior to placement: chore, personal care, and adult day services. These services and overnight hospital use for the care recipient were included in the analysis. Service use was assessed at pre-placement and at the 6-month post-placement intervals for this study. Comparisons of self-reported service use with demonstration-reimbursed claims in MADDE found that 93% of the cases could correctly identify that they were or were not receiving a service (Newcomer et al., 1999). The post-placement measurements could be considered assessments of service use “during” NHA, as each measure determined whether caregivers utilized the aforementioned community-based or overnight hospital services in the 6 month time interval in which institutionalization occurred. However, information on whether these services were used leading up to NHA or how long these services were used after NHA was not available.

Caregivers’ self-reported health status (as measured on a single item, 4-point Likert scale: 1 = excellent; 2 = good; 3 = fair; 4 = poor; see Idler & Benyamini, 1997; Shanas et al., 1968) and caregivers’ own functional dependency as measured by 5 ADLs (6-month α = .62; 12-month α = .60) and 8 IADLs (6-month α = .80; 12-month α = .80) were also available at pre-placement.

Analysis

Description of change following the NH transition: Within subjects models

The first objective of this analysis was to determine whether change in caregiver burden and depressive symptoms was significant in the 6- and 12-month post-placement panels. Within-subjects analyses were utilized. Two waves of data were available in the 6-month post-placement panel (i.e., pre-placement and post-placement). For this reason, a paired T-test was conducted to determine whether change in burden or depressive symptoms in the 6-month placement period was significantly different from zero (p < .05).

Since the 12-month panel offered 3 waves of data (pre-placement and 2 post-placement assessments) a more complex within-subjects model was possible. Specifically, a Level 1 growth curve model was “fit” to describe trajectories of change in burden and depressive symptoms in the 12-month placement panel. A growth curve model includes two levels. Level 1 is an initial within-subjects model that describes intra-individual change in an outcome (i.e., a random effects model where the intercept and rate of change parameters are estimated for a given sample). The Level 1 model examines each individual’s growth as a function of time. To describe trajectories of change in burden and depressive symptoms in the 12-month placement cohort, a Level 1 model using LISREL 8.7 was conducted (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1993). LISREL provides a number of “goodness of fit” indices as well as parameter estimates and mean level change values. In order to conduct a Level 1 growth curve model, n + 1 data points are necessary for the number of parameters estimated in the Level 1 model. Therefore, we limited the Level 1 growth curve model to the 12-month post-placement panel (which included pre-placement, 6-month post-placement, and 12-month post-placement data points that resulted in two Level 1 parameters: initial status/pre-placement and rate of change).

Unlike traditional change variables (such as the change scores calculated for burden and depressive symptoms in the 6-month post-placement panel), the rate of change parameter in a growth curve model is considered a latent variable. This is a unique strength of growth curve modeling since the estimation of this latent parameter takes advantage of all intra-individual data to create a “rate of change” parameter. Another advantage of the growth curve approach is that, in addition to identifying the significance of mean rates of change, variance in the growth curve parameters is also provided. This is important, as rates of change in burden and depressive symptoms were retained as dependent variables in the subsequent 12-month post-placement panel analysis (see below).

Although several studies have attempted to establish a clinical threshold for burden using the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI), these efforts have found less than optimal sensitivity or specificity (Bedard et al., 2001; O’Rourke & Tuokko, 2003). For these reasons, we calculated a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve using the full baseline sample of MADDE to develop a potential threshold score where both the sensitivity (77%) as well as the specificity (or, the true negative rate; 71%) are optimized on the ZBI when compared to the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) (area under the ROC curve = .81). This resulted in a burden threshold score of 13.50. The 15-item GDS has shown sensitivity and specificity in screening for depression at 6 or greater (Lyness et al., 1997), and this score was used as a clinical threshold in subsequent analyses.

Predictors of change in caregiver burden and depressive symptoms after NHA: Between subjects modeling

The second research objective was to identify pre-placement variables that could predict change in caregiver burden or depressive symptoms after NHA. In order to achieve this objective we conducted a series of between-subjects analyses to identify characteristics of caregivers and care recipients that predict change in caregiver burden and depressive symptoms following NHA (i.e., significant change in burden and depressive symptoms after institutionalization). To examine significant between-subjects predictors of change in burden or depressive symptoms in the 6-month post-placement panel, a multivariate regression model was conducted. Six-month change in burden and depressive symptoms (i.e., 6-month post-placement burden/depressive symptoms score minus pre-placement burden/depressive symptoms score) served as the dependent variables in the model. The main independent variables were sociodemographic and contextual characteristics, pre-placement indicators of care recipient dementia severity, pre-placement indicators of care recipient functional dependence, and resources. The multivariate regression also considered pre-placement burden and depressive symptoms as predictors of change in these outcomes. LISREL 8.7 (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1993) was used to evaluate the multivariate regression model. A similar multivariate regression model was conducted to examine 6-month change in burden and depression after NHA in the 12-month post-placement panel.

A Level-2 growth curve model was analyzed to ascertain predictors of change in burden and depressive symptoms in the 12-month post-placement panel. Level 2 is a between-subjects model that identifies significant predictors of the growth curve parameters estimated in Level 1 (e.g., also known as the fixed effects model; Collins & Sayer, 1997; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). As interpreted in Level 2 models, unstandardized regression coefficients represent the amount of change in the outcome per one unit increase in the predictor variable at each measurement interval. In the 12-month post-placement panel analysis, rate of change parameters of burden and depressive symptoms served as the dependent variables of interest. Key covariates included initial status parameters of burden and depressive symptoms as well as sociodemographic and contextual characteristics, pre-placement measures of care recipient dementia severity, pre-placement measures of care recipient functional dependence, and resources. LISREL 8.7 was used to analyze the 12-month growth curve model.

Per the exploratory strategy of this analysis and the desire to limit the multivariate, between-subjects models to empirically pertinent predictors, a series of bivariate correlations were conducted in the 6- and 12-month post-placement panels. Correlations were conducted between sociodemographic and contextual characteristics, indices of care recipient dementia severity and functional dependence, resources, and the panel outcomes (6-month change in burden and depressive symptoms in the 6-month and 12-month post-placement panels and rate of change parameters of burden and depressive symptoms in the 12-moth post-placement panel). If any variable was significantly related to an outcome (p < .05), it was included as a final predictor in the between-subjects multivariate model.

Results

Descriptive Panel Data

As shown in Table 1, the bivariate panel comparisons did not reveal many significant differences. Fewer care recipients in the 6-month post-placement panel were female (59.3% vs. 63.7%;.< .05, respectively) or Medicaid eligible (50.3% vs. 55.1%; p < .05, respectively) when compared to respondents in the 12-month post-placement panel. Time to NHA was also shorter in the 6-month post-placement panel when compared to those in the 12-month post-placement panel (M = 113.86 days vs. M = 99.98 days; p < .001, respectively). The composition of the 6-and 12-month post-placement panels was largely similar, and potential bias due to attrition (e.g., care recipient death, caregiver loss to follow-up) or selection did not appear to result in significant variation between the two panels.

Description of Change Following the NH Transition: Within-Subjects Models

The within-subjects analyses for the 6- and 12-month post-placement panels found significant change in burden and depressive symptoms prior to and after NHA. There was significant change in burden (df = 1609; t = 23.43, p < .001) in the 6-month post-placement panel, with burden greater at pre-placement than at post-placement (M = 13.76 vs. M = 9.60). Depressive symptoms also decreased significantly in the 6-month post-placement panel (df = 1594; t = 6.40, p < .001). There was an average decrease of .52 in depressive symptoms in the 6-month post-placement panel (M = 4.79 at pre-placement vs. M = 4.18 at post-placement).

The within-subjects analysis for the 12-month post-placement panel also indicated significant change in caregiver burden. The Level 1 growth curve trajectories of the 12-month post-placement panel found significant and considerable decreases in burden following NHA (Mrate of change = −3.30, p < .001). Unlike the 6-month panel, mean rate of change in depressive symptoms was not significant (Mrate of change = 1.80, p > .05). Variances in the rate of change parameters for burden (p < .01) and depressive symptoms (p < .05) were significant, suggesting a diversity of trajectories in the 12-month post-placement panel.

An analysis of means at pre-placement and each post-placement interval suggest that the decreases found in burden were clinically relevant. Specifically, burden was above the clinical threshold of 13.50 at pre-placement in the 6-month (M = 13.76) and 12-month (M = 13.58) post-placement panels. Burden fell to levels below the 13.50 clinical threshold at the 6 month post-placement interval (M = 9.60) and the 12 month post-placement interval (M = 6.98) in the 6- and 12-month post-placement panels, respectively. However, the significant change observed on the GDS in the 6-month panel (from 4.79 to 4.18) did not result in a mean shift of depressive symptoms above or below a threshold of clinical significance (i.e., from above a GDS score of 6 at pre-placement to a GDS score below 6 at post-placement).

Predictors of Change in Caregiver Burden and Depressive Symptoms after NHA: Between Subjects Models

The predictors described below and in Tables 2–4 were selected based on their significant correlations with burden and depressive symptom outcomes per the bivariate screening approach (see above).

Table 2.

Multivariate Regression Results: Selected Predictors of Change in Caregiver Burden and Depressive Symptoms after Nursing Home Admission, 6 Months (6-Month Post-Placement Panel, N = 1,610)

| Predictor | 6-Month Burden (R2 = .36) | 6-Month Depressive Symptoms (R2=.23) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | β | t | |

| Pre-Placement Outcome Measures | ||||

| Pre-placement burden | −.65 | −19.73*** | −.03 | −.84 |

| Pre-placement depressive symptoms | .16 | 4.78** | −.50 | −13.67*** |

| Sociodemographic and Contextual Characteristics | ||||

| Site | ||||

| Florida | .07 | 3.18** | .07 | 2.83** |

| Illinois | −.08 | −3.24** | .02 | .62 |

| New York | −.08 | −3.47** | −.12 | −4.63** |

| West Virginia | −.03 | −1.29 | −.04 | −1.70 |

| CG is female | .05 | 2.31* | −.03 | −1.36 |

| CG age | .07 | 2.73* | .16 | 5.60*** |

| CR lives with CG | .00 | .18 | .02 | .56 |

| Time to NHA from pre- placement (days) | .15 | 6.61*** | .02 | 1.01 |

| Care Recipient Dementia Severity | ||||

| Pre-placement behavior problems | −.02 | −.83 | −.01 | −.23 |

| Care Recipient Functional Dependency | ||||

| Pre-placement IADLs | −.02 | −.82 | −.01 | −.27 |

| Pre-placement caregiving hours (typical week) | .00 | .10 | .01 | .21 |

| Pre-placement unmet needs | .04 | 1.88 | .01 | .55 |

| Resources | ||||

| Pre-placement secondary caregiving hours (typical week) | .04 | 1.86 | .00 | .17 |

| Pre-placement adult day service use (days) | −.02 | −.72 | −.04 | −1.55 |

| Overnight hospital use during NHA (times) | .06 | 2.85** | .05 | 2.17* |

| CG pre-placement self-reported health | .00 | .18 | .15 | 5.37*** |

NOTE: CR = care recipient; CG = caregiver; NHA = nursing home admission; IADLs = instrumental activities of daily living;

p < .001;

p < .01;

p < .05

Goodness of fit: df = 78, χ2 = 124.70, p < .001, RMSEA = .02, NNFI = .98, CFI = .99, GFI = .99 Standardized correlation between 6-month change in burden and change in depressive symptoms = .33***

Table 4.

Growth Curve Results: Selected Predictors of Change in Caregiver Burden and Depressive Symptoms after Nursing Home Admission, 12 Months (12-Month Post-Placement Panel, N = 1,116)

| Predictor | 12-Month Rate of Change in Burden(R2= .32) | 12-Month Rate of Change in Depressive Symptoms (R2 = .21) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | β | t | |

| Pre-Placement Outcome Measures | ||||

| Pre-placement burden (initial status parameter) | −.43 | −8.97*** | - | - |

| Pre-placement depressive symptoms (initial status parameter) | - | - | −.44 | −7.65*** |

| Sociodemographic and Contextual Characteristics | ||||

| Site | ||||

| Florida | .11 | 3.27** | .10 | 2.90** |

| New York | −.16 | −5.02*** | −.12 | −3.43** |

| Ohio | .09 | 2.81** | .09 | 2.50* |

| CR is female | −.05 | −1.17 | −.02 | −.32 |

| CR age | −.01 | −.18 | .03 | .69 |

| MADDE treatment group assignment | −.06 | −1.88 | −.04 | −1.09 |

| CG is female | −.05 | −1.20 | −.11 | −2.45* |

| CG is spouse | .26 | 4.11** | .26 | 3.59** |

| CG age | −.02 | −.44 | −.05 | −.92 |

| CG income | .01 | .43 | −.06 | −1.58 |

| CG education | −.04 | −1.44 | −.03 | −.92 |

| CR lives with CG | −.13 | −3.24 | −.06 | −1.28 |

| Care Recipient Functional Dependency | ||||

| Pre-placement ADLs | .07 | 2.08* | .00 | .07 |

| Pre-placement caregiving hours (typical week) | −.05 | −1.20 | −.01 | −.16 |

| Resources | ||||

| Pre-placement chore service use(times) | .04 | 1.48 | .02 | .55 |

| CG pre-placement self-reported health | −.04 | −1.01 | .05 | 1.21 |

| CG pre-placement ADLs | .07 | 1.84 | .07 | 1.58 |

| CG pre-placement IADLs | −.02 | −.49 | .09 | 1.97* |

NOTE: CR = care recipient; CG = caregiver; NHA = nursing home admission; IADLs = instrumental activities of daily living;

p < .001;

p < .01;

p < .05

Goodness of fit: df = 128; χ2 = 608.26; p = .00; RMSEA = .06; NNFI = .91; CFI = .96; GFI = .95 Standardized correlation between 12-month rate of change in burden and change in depressive symptoms = .46***

Six-month change in caregiver burden and depressive symptoms: Multivariate regressions

Empirical results of the multivariate regression model for the 6-month post-placement are presented in Table 2. The model was an excellent fit to the data, with df = 78, χ2 = 124.70, p < .001, Root Mean Square of Approximation (RMSEA) = .02, Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI) = .98, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = .99, and Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI) = .99 (specifically, “excellent” fit is demonstrated in models where p > .05, RMSEA < .05, NNFI >.95, CFI > .95, and GFI >.92) (Schumacker & Lomax, 1996). The model explained a moderate amount of variance in change in burden (R2 = .36) and a smaller amount of variance in change in depressive symptoms (R2 = .23).

Pre-placement burden (β = −.65, p < .001) and pre-placement depressive symptoms (β = −.50, p < .001) were associated with decreases in burden and depressive symptoms respectively following the NH transition. Pre-placement depressive symptoms were also related to post-placement increases in burden (β = .16, p < .01). Several sociodemographic and contextual characteristics emerged as significant predictors. Caregivers from Florida reported greater increases in burden and depressive symptoms 6-months following institutionalization (β = .07, p < .01; β = .07, p < .01, respectively). Caregivers from Illinois and New York indicated greater decreases in burden after NHA (β = −.08, p < .01; β = −.08, p < .01, respectively) while caregivers from New York reported greater decreases in depressive symptoms (β = −.12, p < .01). Caregivers who were older were more likely to report increased burden and depressive symptoms after the NH transition (β = .07, p < .05; β = .16, p < .01, respectively). Female caregivers also indicated increased burden (β = .05, p < .05). Time to NHA was associated with change in burden, as those who institutionalized their care recipients later in the 6-month cohort were more likely to indicate increased burden (β = .15, p < .001).

Two resource variables were significant predictors of change in caregiver burden and depressive symptoms following NHA. Those caregivers who indicated hospital use during the NH transition reported increases in burden and depressive symptoms (β = .06, p < .01; β = .05, p < .05, respectively). Caregivers who reported greater subjective health impairment at pre-placement also reported increases in depressive symptoms in the 6-month placement panel (β = .15, p < .001).

Six-month change in post-placement burden and depression was also modeled in the 12-month post-placement panel. Table 3 demonstrates that the multivariate regression model was a strong fit to the observed data (df = 68, χ2 = 84.3, p = .09, RMSEA = .02, NNFI = .99, CFI = .99, and GFI = .99). The multivariate model accounted for moderate amounts of variance in change in burden (R2 = .34) and less variance in depressive symptoms (R2 = .24). As in the 6-month post-placement panel, the strongest predictor of 6-month change in burden was pre-placement burden (β = −.60, p < .001). Pre-placement depressive symptomatology was strongly related to 6-month changes in depressive symptoms after NHA (β = −.46, p < .001). Pre-placement depressive symptoms were also related to post-placement increases in burden (β = .14, p < .01).

Table 3.

Multivariate Regression Results: Selected Predictors of Change in Caregiver Burden and Depressive Symptoms after Nursing Home Admission, 6 Months (12-Month Post-Placement Panel, N = 1,116)

| Predictor | 6-Month Burden (R2 = .34) | 6-Month Depressive Symptoms (R2=.24) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | β | t | |

| Pre-Placement Outcome Measures | ||||

| Pre-placement burden | −.60 | −15.66*** | .00 | .07 |

| Pre-placement depressive symptoms | .14 | 3.79** | −.46 | −11.63*** |

| Sociodemographic and Contextual Characteristics | ||||

| Site | ||||

| Illinois | −.08 | −2.88** | .01 | .28 |

| New York | −.10 | −3.52** | −.15 | −4.65** |

| Ohio | .08 | 2.86* | .05 | 1.61 |

| Oregon | .07 | 2.30* | .05 | 1.68 |

| West Virginia | .01 | .51 | .00 | .10 |

| CG is female | .04 | 1.28 | −.03 | −1.04 |

| CG age | .07 | 2.34* | .15 | 4.73** |

| CR lives with CG | −.02 | −.78 | .01 | .40 |

| Time to NHA from pre- placement (days) | .15 | 5.57*** | .03 | 1.02 |

| Care Recipient Dementia Severity | ||||

| Pre-placement behavior problems | −.01 | −.28 | .00 | .09 |

| Care Recipient Functional Dependency | ||||

| Pre-placement IADLs | −.01 | −.34 | .01 | .37 |

| Pre-placement caregiving hours (typical week) | .02 | .65 | .03 | 1.00 |

| Resources | ||||

| Pre-placement adult day service use (days) | −.03 | −.99 | −.06 | −1.91 |

| Overnight hospital use during NHA (times) | .06 | 2.23* | .04 | 1.48 |

NOTE: CR = care recipient; CG = caregiver; NHA = nursing home admission; IADLs = instrumental activities of daily living;

p < .001;

p < .01;

p < .05

Goodness of fit: df = 68, χ2 = 84.3, p = .09, RMSEA = .02, NNFI = .99, CFI = .99, and GFI = .99 Standardized correlation between 6-month change in burden and change in depressive symptoms = .34***

Several sociodemographic and contextual characteristics were associated with 6-month change in burden and depressive symptoms after NHA in the 12-month post-placement panel. Older caregivers were more likely to report increases in burden and depressive symptoms after institutionalization (β = .07, p < .05; β = .15, p < .01). Site variables were also predictive of change in burden and depressive symptoms up to 6 months after NHA in the 12-month post-placement panel. Caregivers from Illinois and New York reported decreases in burden (β =−.08, p < .01; β = −.10, p < .01). Caregivers from the New York site also reported decreases in depressive symptoms up to 6 months following placement (β = −.15, p < .01). Caregivers from the Ohio and Oregon catchment areas were more likely to report increases in burden (β = .08, p < .05; β = .07, p < .05, respectively). Caregivers’ with a longer interval from pre-placement to NHA reported increases in burden at the 6-month post-placement interval (β = .15, p < .001). One resource variable was predictive of change in burden up to 6-months after NHA in the 12-month post-placement panel; caregivers who utilized more overnight hospital services during institutionalization indicated increased burden (β = .06, p < .05).

12-month rate of change in caregiver burden and depressive symptoms: Level 2 growth curve

The results of the Level 2 growth curve model are displayed in Table 4. The model proved a moderate fit to the data (df = 128; χ2 = 608.26; p = .00; RMSEA = .06; NNFI = .91; CFI = .96; GFI = .95). The 12-month post-placement model explained a moderate amount of variance in the rate of change parameter for burden (R2 = .32) and a smaller amount of variance in the rate of change parameter for depressive symptoms (R2 = .21). The burden initial status parameter (i.e., pre-placement) was strongly and negatively predictive of rate of change in burden (β = −.43, p < .001). Similarly, those caregivers who reported higher depressive symptoms prior to NHA were more likely to indicate mean decline in depressive symptoms following institutionalization (β = −.44, p < .001). Caregivers who were spouses were much more likely to experience increases in burden (β = .26, p < .01) and depressive symptoms (β = .26, p < .01) after NHA. The site variables were also associated with caregiver burden and depressive symptoms after the NH transition; caregivers from Florida and Ohio experienced increases in burden (β = .11, p < .01; β = .09, p < .01, respectively) and depressive symptoms (β = .10, p < .01; β = .09, p < .01, respectively) while caregivers from New York reported decreases in burden and depressive symptoms (β = −.16, p < .001; β = −.12, p < .01, respectively). Functional dependency on the part of care recipients also appeared to influence burden and depressive symptoms following NHA. Care recipients with greater ADL dependence at pre-placement had caregivers who reported increased burden (β = .07, p < .05). One resource variable was predictive of rate of change in depressive symptoms up to 12 months after NHA. Caregivers who experienced their own ADL impairment reported increased depressive symptoms (β = .09, p < .05).

Discussion

The within subjects analyses found that caregiver burden and depressive symptoms decreased significantly in the 6-month post-placement panel. Burden also decreased significantly up to 12 months following NHA. When compared to longitudinal analyses of at-home caregivers in MADDE (Gaugler, Kane, Kane, & Newcomer, 2005) and analyses using other data sources that compared at-home caregivers with those who institutionalized (Gaugler et al., 2008), the decreases observed in this study lend some confidence to the conclusion that the reductions in burden are due, at least in part, to the effects of NHA. Institutionalization may contribute to mean reductions in emotional distress as daily care tasks are assumed by facility staff. It is important to note that while stress related to at-home care may decrease, it is possible that there is a trade-off as one set of stressors (care demands) is replaced with another (dissatisfaction with NH care staff; see Gaugler et al., 2000). Nonetheless, the results emphasize that NHA is a transition in the dementia caregiving process that may offer at least some benefit for caregivers. It is also notable that the considerable decline in burden prior to and after institutionalization appears to be clinically relevant, and provides further support that NHA may offer considerable emotional relief to dementia caregivers. The significant change observed for depressive symptoms in the 6-month post-placement panel did not appear to result in a mean shift above or below the clinical significance threshold of the GDS.

A contextual variable that was predictive of 6-month change in burden was time to NHA. A longer duration between the pre-placement interview and actual institutionalization was predictive of increases in burden. This suggests considerable emotional distress and upheaval leading up to institutionalization. While the original findings of MADDE found that treatment effects were small by site, half of the sites demonstrated small, albeit significant, effects. The present study also found several site effects. In particular, caregivers in Florida were more likely to indicate increases in burden and depressive symptoms following NHA. As the MADDE data did not have access to key site-level characteristics, it is difficult to conclude what regional factors may have explained this effect. Cultural reasons, variation in reimbursement caps and how the case management models were delivered by site, and different case manager to client ratios by site may all have influenced the site differences found in this study. Another explanation may lie in when the MADDE data were collected (1989–1994). For example, Hurricane Andrew struck Florida during the hurricane season of 1992 and the extensive damage this event caused may have led to increased psychological or emotional distress to caregivers living in Florida. Other possible explanations could lie in issues related to NH bed supply, availability of affordable home care services, and long-term care policies in Florida, Ohio, Oregon, or New York relative to other regions in MADDE. The site differences reported here emphasize the need to consider regional characteristics and historical events that may influence the longitudinal experience of dementia caregivers (for more detail on site variations in MADDE, see Miller et al., 1999).

A relatively unexplored issue in dementia caregiving research is the influence of transitioning from one type of service use to another (e.g., adult day service use and institutionalization; see Wilson et al., 2007). A service transition to consider is overnight hospital use and NHA. Overnight hospital use during the NH transition was associated with an increase in caregiving burden and depressive symptoms in the 6-month post-placement panel. Delirium, depressive symptoms, or other comorbid conditions are often prevalent in older persons in acute care settings along with Alzheimer’s disease (see Fick, Agostini, & Inouye, 2002; Pisani, Murphy, Van Ness, Araujo, & Inouye, 2007). These clinical challenges may increase caregivers’ difficulties when navigating the transition from overnight hospital use to long-stay residential care. It is possible that the clinical complexity of managing dementia in acute care settings results in a more difficult NH transition for caregivers during the early stages of institutionalization. Overnight hospital use may also have led to the initial decision to institutionalize, and during the early months of placement some of the medical challenges associated with hospital use may have made for a more difficult emotional and psychological transition for caregivers. Nursing home placement is sometimes advised by hospital personnel and may be an unexpected, rather than planned, event which may likewise make NHA more emotionally difficult for caregivers. Over time and with stabilization of some of the problems associated with hospitalization such problems may wane (thus explaining overnight hospital use’s lack of significance in the 12-month post-placement panel).

A particularly strong predictor of increases in burden and depressive symptoms in the 12-month post-placement panel was caregiver kin relationship. Spouses reported greater increases in care burden and depressive symptoms up to 12 months after NHA when compared to other caregivers. This is consistent with research that found greater burden among spouse caregivers than adult child caregivers at home (Pinquart & Sörensen, 2003a; Sörensen, Duberstein, Gill, & Pinquart, 2006). The findings may be due to a higher risk of age-related functional disabilities and a greater sense of emotional and social investment in the role of “caregiver” when compared to adult child caregivers (Gaugler, Zarit, & Pearlin, 1999; Pinquart & Sörensen, 2003a). This intense investment in at-home care may also make for a more challenging NH transition as spouse caregivers have more difficulty relinquishing care to facility staff due to the continued desire to provide help (Gaugler, Anderson, & Leach, 2003). It is not clear why spousal relationship did not emerge as a significant predictor of change in burden or depressive symptoms in the 6-month post-placement panel. The long-term adjustment to NHA may pose more difficulties for spouses than other relatives of the cognitively impaired care recipient, whereas the shorter-term stressors associated with institutionalization (e.g., becoming acclimated to staff or the NH environment) equally affect family caregivers regardless of kin relationship.

Another important predictor of increase in burden in the 6-month post-placement cohort was pre-placement depressive symptoms. It is possible that the months immediately following NHA are most challenging for caregivers who had the greatest psychological difficulty providing at-home care or making the decision to institutionalize a relative suffering from dementia. Caregivers who have psychological difficulties prior to NHA may be less likely to adjust to their roles immediately after NHA, resulting in less involvement (e.g., fewer visits, see Gaugler et al., 2000) and perhaps greater emotional distress. With time and increased comfort in their roles in a post-placement situation, caregivers who experience pre-placement depressive symptoms are no more likely to indicate feelings of burden than others who have placed their relatives in a nursing home.

An important limitation and implication of our results is the need for measures that better capture the NH transition for family caregivers (Aneshensel et al., 1995). Similar to other studies that have examined caregiver well-being after NHA, our dependent variables included two common measures of stress and well-being (the ZBI and GDS). As with many studies of caregiver stress following NHA that include pre- and post-placement measurements, data were not available in MADDE to capture challenges specific to institutionalization for caregiving families (e.g., how the decision to institutionalize came about, how helpful the NH was in facilitating the move, difficulty in finding an appropriate facility, overall satisfaction with the institutionalization experience). Prior research has found that family caregivers engage in interaction with staff, provide IADL assistance, and offer socioemotional forms of care but reduce their time spent in hands-on tasks such as ADL care or behavioral supervision after NHA (see Gaugler et al., 2005; Gaugler & Kane, 2007). Due to these shifts in care responsibility, measures that focus on family-staff interaction, family satisfaction with care staff and the facility, and assessments of stress factors germane to placement may be more representative of the realities of NH care. Such measures may also help to identify caregivers who experience difficulty adapting to the NH transition (Gaugler et al., 2007; Specht et al., 2005).

Another limitation and implication of our study is the predominant focus on the NH event. MADDE data were collected in the early 1990s. Since then a number of developments have occurred in long-term care such as the emergence of assisted living that may influence families’ placement decisions (Kane, 2001). Given the growth of assisted living, it is important to broaden our consideration of NHA to transitions to other residential environments. A recent review of families and assisted living has suggested that caregiving burden may persist for families following a relative’s entry to assisted living, but few studies exist (Gaugler & Kane, 2007). Issues surrounding assisted living entry such as timing in the course of caregiving, satisfaction with assisted living care, ongoing family involvement, relationship of assisted living entry to NHA, the effect of kinship (spouse vs. adult child) on caregiver distress, and variation in assisted living environments require greater attention when examining key transitions in dementia caregiving.

Similarly, the data available did not allow for an analysis of how prior transitions may have influenced caregiver emotional or psychological distress in this sample. Due to the progression of dementia and the potential for caregivers and care recipients to experience multiple health care transitions prior to NHA (e.g., hospitalization, rehabilitative care placements in a NH), it would be important to consider how these events may influence caregivers’ burden or depressive symptoms following NHA. It is possible that the permanency associated with long-term NHA may actually result in less stress and fewer depressive symptoms for caregivers who have experienced the upheaval of multiple cycles of hospitalization, rehabilitative care, or similar events prior to institutionalization.

The results emphasize that NHA is a critical transition in the dementia caregiving process and one that may offer at least some benefit for caregivers. As suggested by the findings here and in longitudinal evaluation of psychosocial interventions such as the NYU Caregiver Intervention (Gaugler et al., 2008), good clinical care must balance the goal of: 1) sustaining families and delaying institutionalization to maximize quality of life for the person suffering from dementia with 2) facilitating an appropriate transfer to residential long-term care when the family can no longer continue to provide at-home care without significant distress. Coordinating these two clinical objectives poses important challenges for future intervention development.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant R21 AG025625 from the National Institute on Aging/National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Joseph E. Gaugler, School of Nursing, Center on Aging, Center for Gerontological Nursing, University of Minnesota

Mary S. Mittelman, Department of Psychiatry, New York University School of Medicine

Kenneth Hepburn, School of Nursing, Emory University.

Robert Newcomer, Department of Social and Behavioral Science, University of California-San Francisco.

References

- Almberg B, Grafstrom M, Krichbaum K, Winblad B. The interplay of institution and family caregiving: Relations between patient hassles, nursing home hassles and caregivers’ burnout. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2000;15:931–939. doi: 10.1002/1099-1166(200010)15:10<931::aid-gps219>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel CS, Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Zarit SH, Whitlatch CJ. Profiles in caregiving: The unexpected career. San Diego: Academic Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bedard M, Molloy DW, Squire L, Dubois S, Lever JA, O’Donnell M. The Zarit Burden Interview: A new short version and screening version. The Gerontologist. 2001;41:652–657. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.5.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coen RF, O’Boyle CA, Coakley D, Lawlor BA. Individual quality of life factors distinguishing low-burden and high-burden caregivers of dementia patients. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2002;13(3):164–170. doi: 10.1159/000048648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, Sayer AG. Modeling growth and change processes: Design, measurement, and analysis for research in social psychology. In: Reiss H, Judd C, editors. Handbook of research methods in social psychology. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1997. pp. 478–495. [Google Scholar]

- Covinsky KE, Eng C, Lui LY, Sands LP, Sehgal AR, Walter LC, et al. Reduced employment in caregivers of frail elders: Impact of ethnicity, patient clinical characteristics, and caregiver characteristics. Journal of Gerontology: Medical Sciences. 2001;56:M707–13. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.11.m707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covinsky KE, Kahana E, Chin MH, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, Landefeld CS. Depressive symptoms and 3-year mortality in older hospitalized medical patients. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1999;130:563–569. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-7-199904060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fick DM, Agostini JV, Inouye SK. Delirium superimposed on dementia: A systematic review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2002;50:1723–1732. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-Mental State: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Kane RL, Kane RA, Newcomer R. The longitudinal effects of early behavior problems in the dementia caregiving career. Psychology and Aging. 2005;20:100–116. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE. Family involvement in residential long-term care: A synthesis and critical review. Aging & Mental Health. 2005;9:105–118. doi: 10.1080/13607860412331310245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Anderson KA, Leach CR. Predictors of family involvement in residential long-term care. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2003;42:3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Anderson KA, Zarit SH, Pearlin LI. Family involvement in the nursing home: Effects on stress and well-being. Aging & Mental Health. 2004;8:65–75. doi: 10.1080/13607860310001613356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Duval S, Anderson KA, Kane RL. Predicting nursing home admission in the U.S: A meta-analysis. BMC Geriatrics. 2007;7:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Edwards AB, Femia EE, Zarit SH, Stephens MAP, Townsend A, et al. Predictors of institutionalization of cognitively impaired older adults: Family help and the timing of placement. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2000;55b:P247–P256. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.4.p247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Kane RA, Langlois J. Assessment of family caregivers of older adults. In: Kane RL, Kane RA, editors. Assessing the well-being of older people: Measures, meaning, and practical applications. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 320–359. [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Kane RL. Families and assisted living. The Gerontologist. 2007;47(Supp I):730–740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Kane RL, Kane RA, Clay T, Newcomer R. Predicting institutionalization of cognitively impaired older people: Utilizing dynamic predictors of change. The Gerontologist. 2003;43:219–229. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Leitsch SA, Zarit SH, Pearlin LI. Caregiver involvement following institutionalization: Effects of preplacement stress. Research on Aging. 2000;22:337–359. [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Pot AM, Zarit SH. Long-term adaptation to institutionalization in dementia caregivers. The Gerontologist. 2007;47:730–740. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.6.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Roth DL, Haley WE, Mittelman MS. Can counseling and support reduce burden and depressive symptoms in caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease during the transition to institutionalization? Results from the New York University Caregiver Intervention study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2008;56(3):421–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01593.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Yu F, Krichbaum K, Wyman JF. Predictors of nursing home admission for persons with dementia. Medical Care. 2009;47:191–198. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31818457ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Zarit SH, Pearlin LI. Caregiving and institutionalization: Perceptions of family conflict and socioemotional support. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 1999;49:15–38. doi: 10.2190/91A8-XCE1-3NGX-X2M7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haley WE. The family caregiver’s role in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1997;48:S25–9. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.5_suppl_6.25s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1997;38:21–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog KG, Sörbom D. LISREL 8: Structural equation modeling with the SIMPLIS command language. Chicago, IL: Scientific Software International; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kane RA. Long-term care and a good quality of life: Bringing them closer together. The Gerontologist. 2001;41:293–304. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1963;185:914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langa KM, Chernew ME, Kabeto MU, Herzog AR, Ofstedal MB, Willis RJ, et al. National estimates of the quantity and cost of informal caregiving for the elderly with dementia. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16:770–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.10123.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. The Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Cameron M. Respite care for people with dementia and their carers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Online) 2004;2(2):CD004396. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004396.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyness JM, Noel TK, Cox C, King DA, Conwell Y, Caine ED. Screening for depression in elderly primary care patients. A comparison of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression scale and the Geriatric Depression Scale. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1997;157:449–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majerovitz SD. Predictors of burden and depression among nursing home family caregivers. Aging & Mental Health. 2007;11:323–329. doi: 10.1080/13607860600963380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller R, Newcomer R, Fox P. Effects of the Medicare Alzheimer’s Disease Demonstration Evaluation on nursing home entry. Health Services Research. 1999;34:691–714. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore MJ, Zhu CW, Clipp EC. Informal costs of dementia care: Estimates from the National Longitudinal Caregiver Study. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2001;56:S219–S228. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.4.s219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomer R, Spitalny M, Fox P, Yordi C. Effects of the Medicare Alzheimer’s Disease Demonstration Evaluation on the use of community-based services. Health Services Research. 1999;34:645–667. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomer R, Yordi C, DuNah R, Fox P, Wilkinson A. Effects of the Medicare Alzheimer’s Disease Demonstration on caregiver burden and depression. Health Services Research. 1999;34:669–689. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke N, Tuokko HA. Psychometric properties of an abridged version of the Zarit Burden Interview within a representative Canadian caregiver sample. The Gerontologist. 2003;43:121–127. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks SM, Novielli KD. A practical guide to caring for caregivers. American Family Physician. 2000;62:2613–2622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Associations of stressors and uplifts of caregiving with caregiver burden and depressive mood: A meta-analysis. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2003a;58:P112–28. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.2.p112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging. 2003b;18:250–267. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisani MA, Murphy TE, Van Ness PH, Araujo KL, Inouye SK. Characteristics associated with delirium in older patients in a medical intensive care unit. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167:1629–1634. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.15.1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Application and data analysis methods. 2. Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: The caregiver health effects study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282:2215–2260. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.23.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Belle SH, Czaja SJ, McGinnis KA, Stevens A, Zhang S. Long-term care placement of dementia patients and caregiver health and well-being. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292:961–967. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.8.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, O’Brien AT, Bookwala MS, Fleissner K. Psychiatric and physical morbidity effects of dementia caregiving: Prevalence, correlates, and causes. The Gerontologist. 1995;35:771–791. doi: 10.1093/geront/35.6.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, O’Brien A, Czaja S, Ory M, Norris R, Martire LM, Belle SH, Burgio L, Gitlin L, Coon D, Burns R, Gallagher-Thompson D, Stevens A. Dementia caregiver intervention research: In search of clinical significance. The Gerontologist. 2002;42:589–602. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.5.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacker R, Lomax RG. A beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Shanas E, Townsend P, Wedderburn D, Friis H, Milhoj P, Stehouwer J. Old people in three industrial societies. New York: Atherton; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh J, Yesavage J. Geriatric Depression Scale: Recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clinical Gerontologist. 1986;5:165–173. [Google Scholar]

- Sörensen S, Duberstein P, Gill D, Pinquart M. Dementia care: Mental health effects, intervention strategies, and clinical implications. Lancet Neurology. 2006;5:961–973. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70599-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Specht JK, Park M, Maas ML, Reed D, Swanson E, Buckwalter KC. Interventions for residents with dementia and their family and staff caregivers: Evaluating the effectiveness of measures of outcomes in long-term care. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2005;31:6–14. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20050601-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tornatore JB, Grant LA. Burden among family caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease in nursing homes. The Gerontologist. 2002;42:497–506. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.4.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitaliano PP, Zhang J, Scanlan JM. Is caregiving hazardous to one’s physical health? A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:946–972. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.6.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlatch CJ, Schur D, Noelker LS, Ejaz FK, Looman WJ. The stress process of family caregiving in institutional settings. The Gerontologist. 2001;41:462–473. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.4.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, McCann JJ, Li Y, Aggarwal NT, Gilley DW, Evans DA. Nursing home placement, day care use, and cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:910–915. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe K, Fox P, Newcomer R, Sands L, Lindquist K, Dane K, et al. Patient and caregiver characteristics and nursing home placement in patients with dementia. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;287:2090–2097. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.16.2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarit SH, Orr N, Zarit J. Understanding the stress of caregivers: Planning an intervention. In: Zarit SH, Orr N, Zarit J, editors. Hidden victims of Alzheimer’s disease: Families under stress. New York: NYU Press; 1985. pp. 69–86. [Google Scholar]

- Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: Correlates of feelings of burden. The Gerontologist. 1980;20(6):649–655. doi: 10.1093/geront/20.6.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarit SH, Whitlatch CJ. Institutional placement: Phases of transition. The Gerontologist. 1992;32:665–672. doi: 10.1093/geront/32.5.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]