Abstract

β-Thalassemia is a genetic disorder caused by mutations in the β-globin gene. Triplex-forming oligonucleotides and triplex-forming peptide nucleic acids (PNAs) have been shown to stimulate recombination in mammalian cells via site-specific binding and creation of altered helical structures that provoke DNA repair. However, the use of these molecules for gene targeting requires homopurine tracts to facilitate triple helix formation. Alternatively, to achieve binding to mixed-sequence target sites for the induced gene correction, we have used pseudo-complementary PNAs (pcPNAs). Due to steric hindrance, pcPNAs are unable to form pcPNA–pcPNA duplexes but can bind to complementary DNA sequences via double duplex-invasion complexes. We demonstrate here that pcPNAs, when co-transfected with donor DNA fragments, can promote single base pair modification at the start of the second intron of the beta-globin gene. This was detected by the restoration of proper splicing of transcripts produced from a green fluorescent protein-beta globin fusion gene. We also demonstrate that pcPNAs are effective in stimulating recombination in human fibroblast cells in a manner dependent on the nucleotide excision repair factor, XPA. These results suggest that pcPNAs can be effective tools to induce heritable, site-specific modification of disease-related genes in human cells without purine sequence restriction.

INTRODUCTION

β-Thalassemia, a blood disease linked to defects in the β-globin gene, is a common genetic disorder that can be caused by over 200 mutations in the β-globin gene (1). Many of the mutations responsible for β-thalassemia involve single base-pair substitutions. Among these, some of the most frequent cause aberrant splicing of intron 1 (IVS1-110, IVS1-6 and IVS1-5) or intron 2 (IVS2-1, IVS2-654 and IVS2-745) of the human β-globin gene (2). Such mutations activate aberrant splice sites in the introns, leading to the production of aberrantly spliced mRNA, improper translation and a deficiency in β-globin that ultimately results in β-thalassemia.

In one approach specific to the thalassemias in which the genetic defect affects mRNA splicing, antisense oligonucleotides have been used to block aberrant splice sites in thalassemic mRNA transcripts (3,4). Nonetheless, as they do not correct the responsible mutation, there is a requirement for continued administration of the antisense molecules to maintain the desired effect.

Gene targeting via homologous recombination (HR) offers a potential strategy for gene correction. Several groups have shown that gene correction at a chromosomal locus can be mediated by donor DNA fragments that are designed to be homologous to the target gene (differing only at the bp of the mutation to be corrected) (5,6). Other studies have shown that site-specific chromosomal damage can substantially increase the frequency of HR by exogenous DNA (7). One method to create site-specific DNA damage is the use of triplex-forming oligonucleotides (TFOs) which bind as third strands to homopurine/homopyrimidine sites in duplex DNA in a sequence-specific manner (8). The formation of a triple helix creates a helical distortion that has been shown to provoke DNA repair and recombination (9–11). This approach has been used successfully to stimulate targeted recombination at chromosomal loci in mammalian cells, with recombination frequencies of up to 0.5%. Similarly, another class of DNA-binding molecules, bis-PNAs, which can bind to homopurine regions to form PNA/DNA/PNA triplexes, with a displaced DNA strand, can create PNA ‘clamps’ that also create a helical distortion that strongly provokes repair and recombination (12).

However, both of these approaches are limited by the requirement for a polypurine sequence in the target duplex to enable triplex formation. To overcome this limitation, Lohse et al. (13) reported the design of pseudo-complementary PNAs (pcPNAs), which can bind to duplex DNA at mixed purine-pyrimidine sequences via double duplex strand invasion to form four stranded complexes. To achieve pseudo-complementarity, pcPNAs are synthesized with 2,6-diaminopurine (D) and 2-thiouracil (sU) nucleobases instead of As and Ts, respectively apart from natural guanine and cytosine bases. While D and sU substitutions impede the base pairing between two mutually pcPNA oligomers (due to steric hindrance), they do not prevent pcPNAs from binding to the corresponding sequences in DNA carrying natural nucleobases. As a result, a pair of pcPNAs can pry open a duplex DNA site via formation of double-duplex invasion complexes. This novel mode of pcPNA-mediated DNA recognition substantially extends the range of possible DNA targets for pcPNAs, since almost any chosen mixed-base site in duplex DNA can be targeted with pcPNAs (A + T content ≤40%).

In work so far, it has been reported that pcPNAs can block access of T7 RNA polymerase to the corresponding promoter site in vitro thus inhibiting transcription initiation (13). Later it was shown that a pair of psoralen-conjugated pcPNAs can direct the formation of targeted psoralen photoadducts on duplex plasmid DNA in vitro (14) as well as at a chromosomal site in living cells, leading to the production of site-specific mutations with high efficiency and specificity (15). These results suggest the potential of pcPNAs to serve as highly specific gene targeting agents in cells.

In the work reported here, we have evaluated the possibility of using a pair of pcPNAs to stimulate recombination at a chromosomal site in mammalian cells. A common β-thalassemia mutation occurs at the first position of intron 2 in the human β-globin gene (designated IVS2-1). We therefore chose intron 2 of the β-globin gene as a target for pcPNA binding. We established an assay for gene correction in which the splicing-defective β-globin intron 2 is inserted within the green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter gene, which in turn was integrated as a single chromosomal copy in CHO cells. In this assay, correction of the IVS2-1 mutation is required to allow GFP expression. We find that transfection of cells with a pair of 13-mer pcPNAs targeting β-globin intron 2, 50 base-pairs downstream of the IVS2-1 mutation can induce recombination of a 51-mer donor DNA with the target site, yielding correction of the thalassemia-associated splicing mutation at frequencies of up to 0.78%. The activity of the pcPNAs and donor DNAs in gene correction was enhanced by measures to modify target site accessibility and to improve oligomer delivery, including synchronization of the cells in S-phase, treatment of cells with a histone deacetylase inhibitor, and the use of the endosome-disrupting agent, chloroquine.

Finally, we demonstrate that pcPNA-induced recombination and gene modification is dependent on the nucleotide excision repair (NER) damage recognition factor, XPA. Recombination was not detected in human fibroblast cells deficient in XPA, but was observed in a cDNA-complemeted line expressing XPA.

These results show that pcPNAs can effectively induce recombination at mixed-sequence chromosomal target sites within human β-globin sequences, providing the foundation for a new therapeutic strategy for modifying mutations in disease-related human genes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells

The β-globin intron IVS2-1 (G→A) carrying a thalassemia-associated mutation or its wild-type equivalent IVS2wt was inserted into the eGFP cDNA sequence of the pEGFP-N1 plasmid (Clontech, Palo Alto CA), between nucleotides 105 and 106, by PCR-based homologous recombination (16), resulting in pGFP/IVS2-1 and pGFP/IVS2wt, respectively. The HinDIII-NotI fragments of these plasmids, containing the GFP sequence interrupted by IVS2-1 or IVS2wt construct, were subcloned into the multiple cloning site of pcDNA5/FRT (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and the resulting vectors were stably transfected into CHO-Flp host cell lines using the Flp-In System according to manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad CA). Clones that had undergone single-copy integration at the expected site were isolated by selection and confirmed via Southern blot (data not shown). The resulting CHO-GFP/IVS2-1G→A cells and control CHO-GFP/IVS2-1WT cells were grown in Ham's F12 media supplemented with 10% FBS and 2 mM l-glutamine.

To study the role of NER in pcPNA-stimulated recombination, two human fibroblast cell lines, the XPA-deficient XP12RO (homozygous for a nonsense mutation at Arg207) and its XPA-expressing subline, XP12RO/CL12 (17) (kind gift from Richard Wood, University of Pittsburgh Medical School) were used. Cells were maintained in RPMI supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 2 mM glutamine and 1% antibiotics (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

pcPNAs and oligonucleotides

Boc-protected PNA monomers of 2-thiouracil and 2,6-diaminopurine were synthesized according to published methods (13). These monomers were used together with commercially available Boc-protected G and C PNA monomers (Applied Biosystems, CA). PNA oligomers were synthesized on a MBHA resin by standard procedures (18), purified by RP-HPLC and characterized by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. DNA oligonucleotides were synthesized by Midland Certified Reagent Company (TX), using cyanoethyl phosphoramidite chemistry, and purified by HPLC. For targeting of the endogenous beta globin gene, the donor DNA is a 50-mer, single-stranded end-protected oligonucleotide that is homologous to the human beta-globin gene but introduces a 6-nucleotide mutation at the exon 2/intron 2 boundary. Sequences of oligomers used are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sequences of PNA and DNA oligomers

| pcPNA1 | H-Lys-DCGDCSUCDCSU-Lys-NH2 |

| pcPNA2 | H-Lys-DGSUGDGSUCGSU-Lys-NH2 |

| pcPNA3 | H-Lys-GSUDGDSUCDCSU-Lys-NH2 |

| pcPNA4 | H-Lys-DGSUGDSUCSUDC-Lys-NH2 |

| Bis-PNA5 | JJJJJTTJJT-O-O-O-TCCTTCCCCC-(Lys)3 |

| pcPNA6 | H-Lys-SUDSUGDCDSUGDDCSU-(Lys)4-NH2 |

| pcPNA7 | H-Lys-DGSUSUCDSUGSUCDSUD-(Lys)4-NH2 |

| PNA8 | H-Lys-TATGACATGAACT-(Lys)4-NH2 |

| PNA9 | H-Lys-AGTTCATGTCATA-(Lys)4-NH2 |

| AG30 | AGGAAGGGGGGGGTGGTGGGGGAGGGGGAG |

| SCR30 | GGAGGAGTGGAGGGGAGTGAGGGGGGGGGG |

| supF1 Donor | TTCGAACCTTCGAAGTCGATGACGGGAGATTTAGAGTCTGCTCCCTTTGGC |

| supF2 Donor | AGGGAGCAGACTCTAAATCTGCCGTCATCGACTTCGAAGG |

| β-globin/GFP Donor | GTTCAGCGTGTCCGGCGAGGGCGAGGTGAGTCTATGGGACCCTTGATGTTT |

| β-globin donor | AAACATCAAGGGTCCCATAGGTCTATTCTGAAGTTCTCAGGATCCACGTG |

PNAs are listed from N to C terminus. D: 2,6-diaminopurine, SU: 6-thiouracil, O-8-amino-2,6-dioxaoctanoic acid. DNA sequences are written from 5′ to 3′.

Binding assays

To assay for the double duplex invasion complexes, various concentrations of pcPNA1 and pcPNA2, as indicated, were incubated with a desired amount (0.5 μg) of pLSG3T7 in TE buffer (pH 7.4) with 10 mM KCl for 16 h at 37°C. The pcPNAs-pLSG3T7 mixtures were then digested with two restriction enzymes (XhoI and BamHI), and analyzed by gel electrophoresis in 8% native polyacrylamide gels (19:1 acrylamide to bisacrylamide) using TBE buffer (90 mM Tris pH 8.0, 90 mM Boric acid and 2 mM EDTA). DNA bands were visualized by silver staining.

For the GFP-pcPNA-binding assay, plasmid pBluescript 2–48 containing the target site for the pcPNA6 and pcPNA7 was generated by annealing the oligonucleotides 5′-GATCATGGTTAAGTTCATGTCATA-3′ and 5′-AATTTATGACATGAACTTAACCAT-3′ and cloning them into the BamHI/EcoRI sites of pBluescriptII-SK (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The resulting plasmid DNA (1 μg) containing the binding site was incubated overnight with increasing concentrations of pcPNAs at 37°C in TE buffer (pH 7.4) with 10 mM KCl. After incubation to allow plasmid:pcPNA complex formation, the samples were digested with PvuII to release a 400 bp fragment, and binding was assayed by gel mobility shift as described above.

Transfection

Total 1 × 106 cells in 100 μl of media were mixed with selected pcPNAs (6 μM) and GFP-DNA (12 μM) oligonucleotides and electroporated in 0.4 cm cuvettes using a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser (280 V, 960 μFd, Hercules, CA). Cells were replated in 60 mm dishes following electroporation and allowed to expand to ∼90% confluency (2–3 days). Chloroquine (100 μM) or Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA, 5 μM) were added after electroporation and media was replaced after 4 h. Two days later as indicated, cells were then visualized via fluorescence microscopy or analyzed by FACS.

For XP12RO and XP12RO/CL12, 1 × 106 cells were transfected with 4 uM beta globin donor DNA (Table 1) and 0 or 8 uM pcPNAs using the Amaxa Nucleofector according to manufacturer's instructions (Human fibroblast NHDF nucleofection kit, Amaxa Biosystems, Gaithersburg MD), then placed in RPMI media containing 10% fetal bovine serum supplemented with G418 at a final concentration of 650 ug/mL (Invitrogen, Carlsbad CA). Cells were harvested 48 h post-nucleofection by trypsinization, and then genomic DNA was extracted using the Wizard Genomic DNA Purification kit (Promega, Madison WI).

Fluorescence microscopy, FACS and live flow cytometry

Cells were visualized using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 (Thornwood, NY) fluorescent microscope at 100× and 200× magnification. Cells for GFP FACS analysis were detached by trypsinization, washed once in 1× PBS, and fixed for at least 2 h at 4°C in 2% paraformaldehyde in 1× PBS. Prior to FACS, the cells were pelleted and resuspended in PBS. Cells were analyzed using a Becton Dickinson FACS-Calibur flow cytometer (Franklin Lakes, NJ). Live cell sorting of samples was performed at the Yale University Cell Sorter Facility using a Becton Dickinson FACSVantage SE flow cytometer, and cells were collected in Ham's F12 media supplemented with 20% FBS. Collected data were then analyzed using the FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR).

Cell synchronization

Double thymidine addition was used for S phase synchronization. Thymidine was added to 1 × 106 cells in Ham's F12 media to a final concentration of 2 mM. Following a 12 h incubation period the thymidine-containing medium was replaced with normal culture medium, and the cells were grown for an additional 12 h to allow exit from S phase. The cells were grown again in medium containing 2 mM thymidine for another 12 h to synchronize the cells at the G1/S border. The arrest was subsequently released by growing the cells in thymidine-free medium for 4–5 h to allow progression into S phase. Cell cycle profiles were determined by FACS, as discussed above.

RNA isolation and analysis

Total RNA was isolated from expanded GFP-positive flow-sorted cells using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Messenger RNA transcripts were then analyzed by reverse transcription-PCR (RT–PCR) on 50 ng purified total RNA with primers pJK115 (5′-AGCAAGGGCGAGGAGCTGTTCACC-3′) and pJK118 (5′-CACTGCACGCCGTAGGTCAGGGT-3′) using the SuperScript One-Step RT-PCR kit (Invitrogen). The products were visualized by electrophoresis on a 1.7% TAE agarose gel. For human cell beta globin RT-PCR, primers were designed to anneal to exon sequences that flank IVS2.

Sequence analysis of genomic DNA

Genomic DNA was purified from expanded GFP-positive flow-sorted cells using the Wizard Genomic DNA Purification kit (Promega, Madison, WI), and the GFP-IVS2 region was amplified using primers pJK115 and pJK118, as above. The resulting PCR products were gel purified and sequenced with forward primer pJK115.

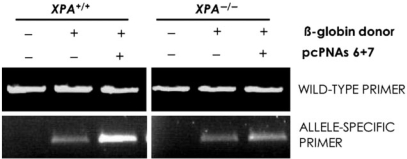

Allele-specific PCR

Gene modification in XP12RO and XP12RO/CL12 cells treated with pcPNAs and beta globin donor DNA was assayed using allele-specific PCR, in which the 3′ end of the forward primer corresponds to the wild-type or mutated sequence as introduced by the donor DNA. Equal amounts of genomic DNA were subjected to 40 cycles of 95° for 30 s, 62° (mutant allele-specific primer) or 64° (wild-type primer) for 30 s, and 72° for 1 min, and the PCR products were electrophoresed on 1% agarose gels.

RESULTS

pcPNA design and binding motif

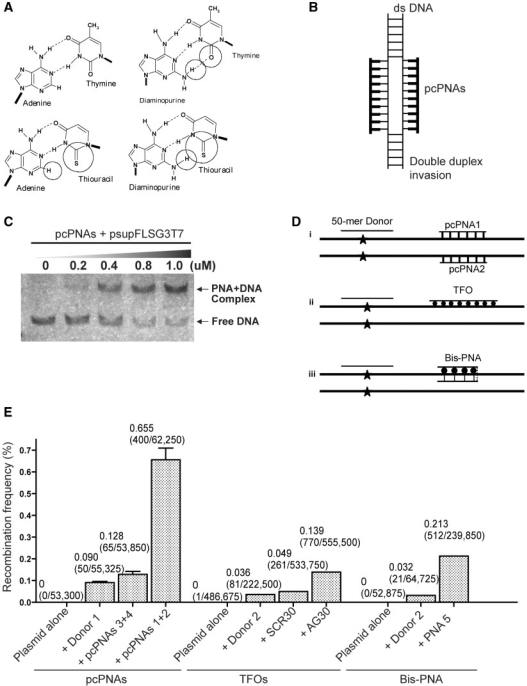

The base pairs that are the basis of the pcPNA strategy, D:T and A:sU, are shown in Figure 1A, along with the canonical A:T base-pair. Note that, in the apposition of sU and D, there is potential steric interference between the thio and amino groups of sU and D, respectively, which prevents pairing between these analogs. Since sU and D can bind without steric hindrance to A and T, respectively, pcPNA pairs can bind cognate DNA but not each other. This property underlies the ability of pcPNAs to form double duplex strand invasion complexes on duplex DNA, as shown in Figure 1B.

Figure 1.

DNA binding and induced recombination by pcPNAs. (A) Base pairing between 2,6-diaminopurine:thymine and between adenine:2-thiouracil in comparison to the canonical A:T base pair. Steric hindrance prevents similar base pairing between 2,6-diaminopurine and 2-thiouracil. (B) Diagram of the double duplex strand invasion complex formed by a pair of pcPNAs on complementary double stranded DNA. (C) Gel mobility shift assay demonstrating binding of pcPNA1 and pcPNA2 to the target site in the supF gene in a reporter plasmid (psupFLSG3T7). (D) Diagram of recombination between a target gene and a single stranded donor DNA induced by selected DNA-binding molecules: (i) pcPNAs, (ii) triplex-forming oligonucleotides (TFOs) and (iii) triplex-forming bis-PNAs. (E) Correction of a point mutation in the supF reporter gene in the shuttle vector, psupFLSG3T7, mediated by the selected molecules. Plasmid DNA was incubated in vitro with the indicated molecules and the samples were transfected into monkey COS cells. Two days later, the episomal DNA was isolated for genetic analysis of the supF gene by transformation into indicator bacteria. Donor DNA indicates a 51-mer single stranded oligonucleotide complementary to the supF gene except for the base pair to be corrected. Molecules designed to bind to the supF gene include pcPNA1 and pcPNA2, which bind 62 bp away from the mutation, the TFO, AG30 and the bis-PNA5, which both bind 24 bp away from the mutation to be corrected. Controls include mismatched pcPNA3 and pcPNA4 (CTR-pcPNAs) and a mismatched DNA oligonucleotide (SCR30). The frequency of gene correction as scored in indicator bacteria is shown. Data represent at least three replicates in all cases, with standard errors given.

Initial test on a plasmid target

We first investigated the ability of a pair of 10-mer pcPNAs (pcPNAs1 and pcPNA2; Table 1) to strand invade into and bind a plasmid target (pSupFLSG3T7) in vitro. Both of the pcPNAs were modified at the C and N-terminus by the addition of lysine residues to provide positive charges to enhance solubility. The two pcPNAs were incubated with the plasmid substrate and binding was assessed by cutting the target region from the plasmid by restriction enzyme digestion. The binding of the pcPNAs to the resulting linear fragment was visualized by gel mobility shift assay; binding of the pcPNA pair to the target is detected as the band of altered mobility that appears with increasing concentrations of pcPNAs (Figure 1C).

We hypothesized that the double duplex strand invasion complex formed by pcPNAs (Figure 1B) might constitute a helical alteration sufficient to provoke DNA repair and recombination. This hypothesis was based on an extrapolation from the activity of TFOs and bis-PNAs, both of which create altered helical structures that have been shown to induce recombination in mammalian cells (12). As a model for gene correction, TFOs and bis-PNAs are able to stimulate recombination between a target gene and a DNA donor fragment in mammalian cells (Figure 1D).

We therefore compared pcPNA1 and pcPNA2 with TFOs and bis-PNA5 in an assay for induced recombination in mammalian cells (Table 1 and Figure 1E). In this assay, we designed each targeting oligomer, including the pair of pcPNAs, the TFO (AG30) and the bis-PNA (bis-PNA5) each to bind to a selected site in the supF reporter gene contained in an SV40-based shuttle vector. In this vector construct, the supF gene has an inactivating single base pair mutation which can be corrected by recombination with a short single stranded oligonucleotide donor. The pcPNAs were designed to bind to a mixed sequence site 62 bp away from the mutation, whereas the TFO and the bis-PNA were targeted to a G:C bp rich polypurine site 24 bp away from the mutation. The plasmid vector DNA was co-mixed with selected molecules and the samples were transfected into monkey COS cells. Two days were allowed for repair/recombination/replication, and the episomal vector DNA was harvested for genetic analysis of the supF gene in indicator bacteria, as previously described (19). As expected, and consistent with other published work, the TFO (AG30) and the bis-PNA5 induced gene correction in the supF gene at frequencies of 0.14 and 0.21%, respectively. Interestingly, the pcPNAs appeared to be even more effective, inducing gene correction by the supF1-donor DNA at a frequency of 0.65%, more than 7-fold above the activity of the donor DNA alone. This elevated frequency of induced recombination produced by the pcPNAs suggests that these molecules have the potential to form highly recombinogenic structures when bound to duplex DNA. A pair of control pcPNAs (pcPNA3 and pcPNA4) with five mismatches each to the supF target site were ineffective, showing the sequence specificity of the process.

Targeted correction of a thalassemia associated mutation in a chromosomal locus

We next sought to test the ability of pcPNAs to induce gene correction at a chromosomal site. We established an assay in which the entire second intron of the human β-globin gene, carrying a thalassemia mutation at position 1 (IVS2-1, G:C to A:T), was inserted within the open reading frame of the GFP gene to form a fusion gene designated GFP/IVS2-1G→A (Figure 2A). This GFP/IVS2-1G→A construct was stably transfected into CHO cells to create a reporter cell line containing a single copy of the GFP/IVS2-1G→A gene. The insertion was directed into a single, pre-defined locus by use of the CHO-Flp system (20), and the new reporter cell line was designated as CHO-GFP/IVS2-1G→A. Single copy integratation was confirmed by Southern blot (data not shown). The IVS2-1 mutation disrupts the normal β-globin splice site, and therefore expression of GFP requires correction of the IVS2-1 mutation so the β-globin intron can be spliced out of the GFP mRNA.

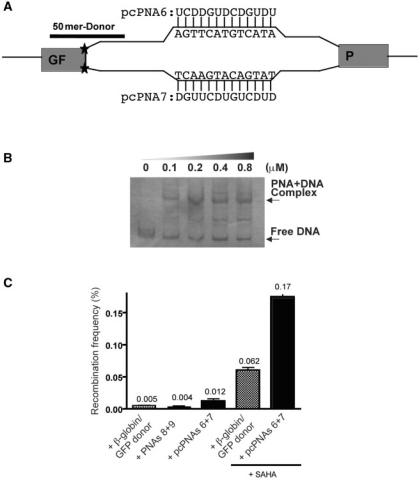

We designed a pair of 13-mer pcPNAs, designated as pcPNA6 and pcPNA7 (Figure 2A and Table 1) to bind within the β-globin intron at positions 51–64, a distance of 50 bp from the splice site mutation. Binding of the pcPNAs to the target site in the β-globin intron was confirmed in a gel mobility shift assay similar to that described above (Figure 2B). A β-globin/GFP donor DNA was designed to correct the IVS2-1 G:C to A:T mutation to the wild-type sequence (Figure 2A). This 51-mer contained 25 nt of GFP sequence and 26 nt of β-globin sequence.

Figure 2.

pcPNA-induced recombination in human β-globin sequences at a chromosomal locus in CHO cells. (A) Schematic illustrating the experimental strategy to study pcPNA-induced recombination. A fusion gene containing the entire second intron of the human β-globin gene, carrying a thalassemia-associated mutation at position 1 (IVS2-1, G:C to A:T), was inserted within the open reading frame of the GFP gene to form a fusion gene designated GFP/IVS2-1G→A. This GFP/IVS2-1G→A construct was stably transfected into CHO cells to create a reporter cell line containing a single copy of the GFP/IVS2-1G→A gene. The IVS2-1 mutation disrupts the normal β-globin splice site, and therefore expression of GFP requires correction of the IVS2-1 mutation so that the β-globin intron can be spliced out of the GFP mRNA. A pair of 13-mer pcPNAs, designated pcPNA6 and pcPNA7, were designed to bind within the β-globin intron at positions 51–64, a distance of 50 bp from the splice site mutation, and to provoke recombination and gene correction by a co-transfected 51-mer single stranded donor DNA. (B) Gel mobility shift assay to assess binding of the pcPNAs to the target site in the β-globin intron, as in Figure 2B. (C) Induced recombination in the chromosomal GFP/IVS2-1G→A gene by electroporation-mediated transfection with selected molecules: β-globin/GFP donor alone, β-globin/GFP donor plus PNAs (non-pseudo-complementary PNA8 and PNA9 of the same sequence as pcPNA6 and pcPNA7), or β-globin/GFP donor plus specific pcPNAs (pcPNA6 and pcPNA7). Cells were also treated or not with the histone deacetylase inhibitor, SAHA, immediately after electroporation with the indicated molecules.

To test the ability of the pcPNAs to induce gene correction within β-globin sequences at a chromosomal site, the CHO-GFP/IVS2-1G→A cells were transfected with β-globin/GFP donor DNA alone, β-globin/GFP donor DNA plus the β-globin pcPNAs (6 + 7), or β-globin/GFP donor DNA plus a pair of regular (non-pseudo-complementary) PNAs of the same sequence (PNA8 and PNA9). Correction of the IVS2-1 G:C to A:T mutation was detected by the generation of green fluorescent cells which were quantified by FACS or fluorescent microscopy.

We found that the combination of pcPNAs (6 and 7) with the β-globin/GFP donor DNA yielded a frequency of gene correction of 0.012% in a single transfection, 3-fold above the frequency seen with the β-globin/GFP donor DNA alone (Figure 2C).

At this stage, we cannot fully explain the differences in frequencies between the episomal and chromosomal targets beyond the obvious differences in the nature of the substrates, including accessibility, chromatin structure, and copy number. In addition to the biological differences between episomal and chromosomal loci, we have used two different sets of pcPNAs for these targets. The reason for this was to optimize the (A + T) content; binding sites with ≥40% A:T bp are preferred. To meet this requirement, we designed and synthesized two different pairs of pcPNAs with slightly different lengths for the episomal and chromosomal targets.

Because previous studies with TFOs have suggested that the accessibility of chromosomal loci to binding molecules can vary with cell cycle phase (21) and transcriptional activity (22), we tested the possibility that modulation of chromatin/DNA interactions by treatment of cells with the histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor, SAHA (an agent currently in clinical trials for cancer therapy), might increase the ability of the pcPNAs to target the GFP/IVS2-1G→A fusion gene. As shown, exposure of cells to SAHA substantially enhanced the gene correction frequencies, with the pcPNAs inducing gene correction at a frequency of 0.17%, a frequency again 3-fold above that seen with the donor alone under such conditions.

Many factors affect gene correction frequency, such as the nature of the DNA-binding molecules, their delivery to the nucleus, the accessibility and structure of the target region, and possibly the cell cycle. Also, different cell lines and different targets may provide for different targeting frequencies. Hence, the frequencies seen in the studies here are not directly comparable to the frequencies reported in other work using single-stranded oligonucleotides alone (6). The point is that whatever the baseline is of recombination mediated by single-stranded donor DNAs themselves, the use of pcPNAs can stimulate the level of recombination.

Note that the pair of unmodified PNAs (PNA8 and 9), which have the same cognate sequence as β-globin-pcPNA6 and β-globin-pcPNA7, respectively, but are complementary to each other, had no effect above that of the GFP-donor DNA alone (0.004% versus 0.005%). The inability of this pair to induce gene correction was expected since they should quench each other by forming a very stable PNA/PNA duplex. This finding suggests that a pair of unmodified PNAs cannot mediate sufficient strand invasion and target DNA binding to promote gene correction, a conclusion consistent with the model that a pair of pcPNAs is necessary to afford sufficient free energy to favor double-duplex invasion complex formation by binding the two target DNA strands simultaneously (13). This demonstrates the importance of the pseudo-complementarity and provides direct evidence for pcPNA-induced recombination.

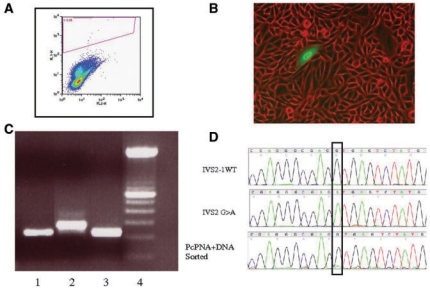

To validate the FACS analysis data (Figure 3A), we routinely performed fluorescent microscopy to directly visualize the green cells (Figure 3B). In selected samples we also used FACS to obtain an enriched population of green cells produced by treatment of the CHO-GFP/IVS2-1G→A cells with the pcPNAs and β-globin/GFP donor DNA. The RT-PCR analysis of the sorted cells (Figure 3C, lane 3) was carried out in comparison to CHO cells containing the GFP gene with the wild-type beta-globin intron (Figure 3C, lane 1), and with the CHO cells containing the GFP gene with the mutated intron Figure 3C, lane 2). Note that the CHO-GFP/IVS2-1G→A cells with the mutant splice site have a larger RT-PCR product consistent with incorrect splicing, that is, use of an aberrant splice site almost 50 nt from the IVS2-1 site. The CHO-GFP/IVS2 wild type cells with the wild-type intron yield a smaller RT–PCR product, indicative of correct splicing out of the entire intron. The sorted cell populations show the correct (smaller) RT-PCR product, in keeping with the restoration of the wild-type splice site sequence at the IVS2-1 position, and consistent with the observed, acquired GFP expression by microscopy and FACS.

Figure 3.

Confirmation of GFP/IVS2-1G→A gene correction at the phenotype and genotype level. (A) Sample FACS analysis of CHO-GFP/IVS2-1G→A cells treated with pcPNA6 and pcPNA7 plus β-globin/GFP donor DNA. GFP fluorescence is scored on the y-axis, and dots in the upper sector represent cells expressing GFP. (B) Fluorescence micrograph of pcPNA6 and pcPNA7 and β-globin/GFP donor DNA-treated cells 48 h after transfection, showing GFP-expressing CHO-GFP/IVS2-1G→A cells in a field of predominantly GFP-negative, uncorrected cells. (C) RT–PCR analysis of RNA harvested from GFP-positive CHO-GFP/IVS2-1G→A cells that were isolated by FACS. RT–PCR of the correctly spliced mRNA results in a 209 bp product, whereas the IVS2-1 splicing mutation yields a longer mRNA and produces a 256 bp RT-PCR product. Lane 1: CHO-GFP/IVS2wt cells with wild-type and thus properly spliced intron 2; lane 2: untreated CHO-GFP/IVS2-1G→A cells; lane 3: CHO-GFP/IVS2-1G→A cells treated with pcPNA6 and pcPNA7 and β-globin/GFP donor DNA sorted by FACS to enrich for GFP-positive cells; lane 4: 100 bp ladder. (D) Genomic DNA from GFP-expressing sorted cells was harvested and sequenced to verify genomic modification at the target site. Chromograms are from untreated CHO-GFP/IVS2wt cells containing the wild-type intron (top), untreated CHO-GFP/IVS2-1G→A cells with the IVS2-1 GA mutation (middle) and CHO-GFP/IVS2-1G→A cells treated with pcPNAs and donor DNAs and sorted by FACS for GFP-expressing cells (bottom).

Finally, as another level of confirmation, genomic DNA was extracted and sequenced from sorted, GFP-positive cells that had been in culture for one month, to demonstrate the presence and persistence of the expected single base pair change at the genomic level (Figure 3D).

Increased pcPNA-mediated gene correction in cells synchronized in S-phase

Since manipulation of chromatin by the use of the HDAC inhibitor, SAHA, yielded an increased frequency of pcPNA-stimulated gene correction, we tested whether selectively targeting cells in S-phase might also yield improved gene correction (23).

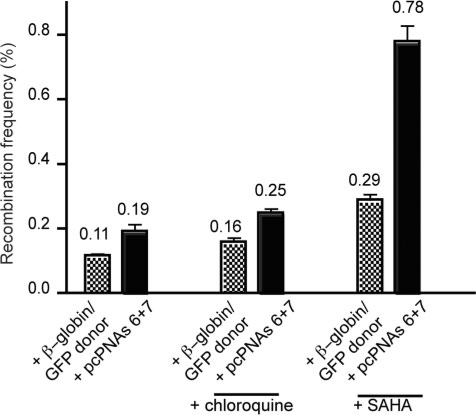

The CHO-GFP/IVS2-1G→A cells were synchronized in S-phase by double thymidine block (24), yielding a cell population with 68% of the cells in S-phase. These cells were transfected with the β-globin-pcPNAs (6 + 7) plus β-globin/GFP donor DNA (or β-globin/GFP donor DNA alone) using electroporation. To attempt further optimization, replicate samples were also treated either with the lysomotropic agent, chloroquine (which has been reported to enhance delivery of PNAs into cells) (25), or with the HDAC inhibitor, SAHA, which we had already found to promote increased levels of gene targeting in asynchronous cells (Figure 2C).

As shown in Figure 4, S-phase synchronized cells are more susceptible to gene correction, with a frequency of 0.19% achieved with the combination of pcPNAs and β-globin/GFP donor DNA. When chloroquine was added, the induced gene correction frequency produced by pcPNAs was further elevated to 0.25%. However, a greater improvement was seen by the combination of cell synchronization and HDAC inhibition by SAHA, yielding a correction frequency of 0.78% in a single treatment, versus 0.29% with donor alone under the same conditions.

Figure 4.

pcPNA-induced recombination in human β-globin sequences at a chromosomal locus in S-phase synchronized CHO cells. CHO-GFP/IVS2-1G→A cells, synchronized in S-phase, were transfected with β-globin/GFP donor DNA alone, or with the pcPNA6 and pcPNA7 plus β-globin/GFP donor DNA. Cells were also treated with the endosomolytic agent, chloroquine or with the histone deacetylase inhibitor, SAHA, immediately after electroporation, as indicated. Bar graph represents data collected from at least three independent experiments, and with standard error indicated.

Requirement for the nucleotide excision repair factor, XPA, in pcPNA-induced recombination

The results above establish that pcPNAs can stimulate recombination and gene modification. It has been shown earlier that the ability of triplex formation to stimulate recombination depends on the nucleotide excision repair pathway and on the damage recognition factor, XPA (9,10,12). To study whether the NER pathway participates in pcPNA-induced gene modification, we performed the recombination assay in two human fibroblast cell lines, the XPA-deficient cell line XP12RO (homozygous for a nonsense mutation at Arg207) and its XPA-expressing, complemented subline, XP12RO/CL12. Cells were transfected with 4 uM donor DNA (designed to introduce a six bp sequence change in the beta globin gene at the exon 1/intron 2 border) and 0 or 8 uM β-globin-pcPNA6 and pcPNA7, harvested 48 h post-transfection by trypsinization, and then genomic DNA was extracted. Gene modification was assayed using allele-specific PCR, in which the 3′ end of the forward primer corresponds to the wild-type or mutated sequence as introduced by the beta globin donor DNA. The results reveal that pcPNA and donor DNA were effective in inducing recombination only in XPA expressing cells (Figure 5). In the XPA-deficient cell line, no recombination was detected above the background (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Role of the NER pathway in pcPNA-induced recombination. Human fibroblast cell lines, either deficient in XPA and/or complemented with XPA cDNA, were transfected with pcPNA6 and pcPNA7 plus donor DNAs specific for beta globin (beta globin donor, designed to introduce a 6 bp mutation; Table 1). Gene modification was assayed using allele-specific PCR, in which the 3′ end of the forward primer corresponds to the modified sequence as introduced by the donor DNA. The gene-specific wild-type primer amplifies the wild-type allele.

These findings suggest that the ability of pcPNAs to induce recombination depends on the NER factor, XPA, and they support the hypothesis that the NER pathway can recognize pcPNA double duplex invasion complexes as lesions, thereby provoking DNA metabolism to yield recombinagenic intermediates.

DISCUSSION

The work reported here demonstrates that pcPNAs can be used to stimulate recombination in mammalian cells. Initial experiments using plasmid substrates were extended to a chromosomal target gene consisting of the GFP gene interrupted by the human β-globin second intron. Correction of a thalassemia-associated mutation at position 1 of β-globin IVS2 was achieved by a combination of the β-globin-specific pcPNAs and a 51-mer single stranded β-globin/GFP donor DNA designed to revert the G:A mutation to the wild-type A:T sequence and thereby restore normal splicing. The combination of pcPNA/donor DNA transfection with cell synchronization in S-phase and with HDAC inhibition yielded gene correction frequencies of up to 0.78% in a single treatment.

Correction of the GFP/β-globin fusion gene was detected at the protein level (green fluorescence in the treated cells), at the mRNA level (by assaying for wild-type or mutant splicing products), and at the genomic level by DNA sequence in FACS-sorted GFP-positive cell populations. Taken together, the detection of gene correction in the CHO-GFP/IVS2-1G→A reporter cell line was confirmed at all levels.

In our prior work, we had shown that site-specific DNA damage mediated by TFOs that bind as third strands in the major groove can induce recombination at a chromosomal luciferase reporter gene in mammalian cells at frequencies up to 0.1% (20). Yet, the use of TFOs requires the availability of polypurine sequences due to the involvement of Hoogsteen bonding by the third strand. The same sequence requirement also restricts the range of target sites for triplex-forming bis-PNAs. Importantly, in the work described here, we show that a pair of pcPNAs can be designed to bind to a mixed sequence site within the β-globin gene IVS2 and can be effective in inducing site-specific recombination in mammalian cells at a chromosomal locus. pcPNA binding to duplex DNA to form a double duplex invasion complex does not require polypurine regions and needs only 40% or more A:T bp content, and so there are many potential pcPNA target sites in all genes.

Recognition of duplex DNA at mixed sequence sites has been achieved by only two other classes of DNA-binding molecules, polyamides (26) and modular zinc finger polypeptides (27). Polyamides show high affinity for duplex DNA in the minor groove, but they have not shown the ability to mediate targeted genome modification in cells. Zinc finger polypeptides, when linked to nuclease domains to form zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs), can induce recombination events in mammalian cells via the direct creation of double strand breaks, which promote recombination (27). Frequencies of gene modification achieved with ZFNs (plus donor DNAs) appear to be about 10-fold higher than those seen here with pcPNAs (plus donor DNAs). However, ZFNs are complex proteins that must be expressed in cells from viral or plasmid vectors and that can produce variable levels of non-specific, off-target nuclease activity. pcPNAs, in contrast, are relatively simple, chemically synthesized oligomers which appear to have favorable toxicity profiles.

Nucleotide excision repair is a versatile DNA damage-removal pathway that plays a critical role in repairing bulky DNA lesions (28,29). XPA is a key NER factor responsible for recognizing and verifying altered DNA conformations, and it is crucial for correct assembly of the remaining repair machinery around the lesion (30). Although the exact mechanisms by which these proteins recognize DNA damage is not understood, damage recognition signals have been proposed, including defects in the DNA helical structure and modification of the DNA chemistry. The ability of triplex-forming bis-PNAs and TFOs, to stimulate recombination with donor DNAs has been shown to be dependent on the nucleotide excision repair and on XPA in particular. pcPNAs invade DNA duplex by forming double duplexes invasion complexes and thereby significantly altering DNA helical structure and chemistry. Based on this we hypothesized that XPA would play a role in the repair of the pcPNA double duplex invasion structure. Experiments with NER-deficient human fibroblast cells lacking XPA function and with a cDNA-corrected, otherwise isogenic subline reveal that NER is required for production of the recombinants. This result not only is consistent with our previous work showing that triplex-induced recombination is substantially reduced in human mutant cell lines deficient in XPA (8,10), but also it demonstrates directly that XPA is required for the process of pcPNA-induced recombination.

The work reported here, demonstrates that pcPNAs having minimum sequence restrictions can effectively target human β-globin gene sequences and promote correction of a thalassemia-associated mutation. The work not only demonstrates targeting of a beta globin construct in a reporter CHO cell line but also in patient-derived human XPA-deficient and complemented cells. This work may provide a basis for a new therapeutic strategy for hemoglobin disorders.

FUNDING

National Institute of Health (R01CA64186 and R01HL082655) (to P.M.G.). Funding for open access charge: R01HL082655.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr Scott Strobel in the Department of Molecular Biophysics and Biochemistry for the space and resources required for pcPNA monomer synthesis. We also thank Denise Hegan, Lisa Cabral and Dr Setu Roday for their assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schwartz E, Benz EJ. Hematology: basic principles and practice. In: Hoffman R, Benz EJ, Shattil SJ, Furie B, Cohen HJ, editors. Thalassemia Syndromes. NY: Churchill Livingston; 1991. pp. 586–610. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chui DH, Hardison R, Riemer C, Miller W, Carver MF, Molchanova TP, Efremov GD, Huisman TH. An electronic database of human hemoglobin variants on the World Wide Web. Blood. 1998;91:2643–2644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sazani P, Gemignani F, Kang SH, Maier MA, Manoharan M, Persmark M, Bortner D, Kole R. Systemically delivered antisense oligomers upregulate gene expression in mouse tissues. Nat. Biotech. 2002;20:1228–1233. doi: 10.1038/nbt759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sierakowska H, Sambade MJ, Agrawal S, Kole R. Repair of thalassemic human beta-globin mRNA in mammalian cells by antisense oligonucleotides. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:12840–12844. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.12840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu YL, Parekh-Olmedo H, Drury M, Skogen M, Kmiec EB. Reaction parameters of targeted gene repair in mammalian cells. Mol. Biotech. 2005;29:197–210. doi: 10.1385/MB:29:3:197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olsen PA, Randol M, Luna L, Brown T, Krauss S. Genomic sequence correction by single-stranded DNA oligonucleotides: role of DNA synthesis and chemical modifications of the oligonucleotide ends. J. Gene Med. 2005;7:1534–1544. doi: 10.1002/jgm.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jasin M. Genetic manipulation of genomes with rare-cutting endonucleases. Trends Genet. 1996;12:224–228. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(96)10019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vasquez KM, Wang G, Havre PA, Glazer PM. Chromosomal mutations induced by triplex-forming oligonucleotides in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:1176–1181. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.4.1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vasquez KM, Marburger K, Intody Z, Wilson JH. Manipulating the mammalian genome by homologous recombination. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:8403–8410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111009698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang G, Seidman MM, Glazer PM. Mutagenesis in mammalian cells induced by triple helix formation and transcription-coupled repair. Science. 1996;271:802–805. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5250.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Datta HJ, Chan PP, Vasquez KM, Gupta RC, Glazer PM. Triplex-induced recombination in human cell-free extracts – dependence on XPA and HsRad51. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:18018–18023. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011646200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rogers FA, Vasquez KM, Egholm M, Glazer PM. Site-directed recombination via bifunctional PNA-DNA conjugates. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:16695–16700. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262556899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lohse J, Dahl O, Nielsen PE. Double duplex invasion by peptide nucleic acid: A general principle for sequence-specific targeting of double-stranded DNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:11804–11808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.11804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim KH, Fan XJ, Nielsen PE. Efficient sequence-directed psoralen targeting using pseudocomplementary peptide nucleic acids. Bioconjug. Chem. 2007;18:567–572. doi: 10.1021/bc0603236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim KH, Nielsen PE, Glazer PM. Site-directed gene mutation at mixed sequence targets by psoralen-conjugated pseudo-complementary peptide nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:7604–7613. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones DH, Howard BH. A rapid method for recombination and site-specific mutagenesis by placing homologous ends on DNA using polymerase chain-reaction. Biotechniques. 1991;10:62–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Köberle B, Roginskaya V, Wood RD. XPA protein as a limiting factor for nucleotide excision repair and UV sensitivity in human cells. DNA Repair. 2006;5:641–648. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Christensen L, Fitzpatrick R, Gildea B, Petersen KH, Hansen HF, Koch T, Egholm M, Buchardt O, Nielsen PE, Coull J, et al. Solid-phase synthesis of peptide nucleic acids. J. Pep. Sci. 1995;1:175–183. doi: 10.1002/psc.310010304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan PP, Lin M, Faruqi AF, Powell J, Seidman MM, Glazer PM. Targeted correction of an episomal gene in mammalian cells by a short DNA fragment tethered to a triplex-forming oligonucleotide. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:11541–11548. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knauert MP, Kalish JM, Hegan DC, Glazer PM. Triplex-stimulated intermolecular recombination at a single-copy genomic target. Mol. Therapy. 2006;14:392–400. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu XS, Xin L, Yin WX, Shang XY, Lu L, Watt RM, Cheah KS, Huang JD, Liu DP, Liang CC. Increased efficiency of oligonucleotide-mediated gene repair through slowing replication fork progression. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:2508–2513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406991102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Igoucheva O, Alexeev V, Pryce M, Yoon K. Transcription affects formation and processing of intermediates in oligonucleotide-mediated gene alteration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:2659–2670. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Majumdar A, Puri N, Cuenoud B, Natt F, Martin P, Khorlin A, Dyatkina N, George AJ, Miller PS, Seidman MM. Cell cycle modulation of gene targeting by a triple helix-forming oligonucleotide. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:11072–11077. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211837200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zielke HR, Littlefield JW. Repetitive synchronization of human lymphoblast cultures with excess thymidine. Methods Cell Biol. 1974;8:107–121. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60447-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abes S, Williams D, Prevot P, Thierry A, Gait MJ, Lebleu B. Endosome trapping limits the efficiency of splicing correction by PNA-oligolysine conjugates. J. Controll. Rel. 2006;110:595–604. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horne DA, Dervan PB. Recognition of mixed-sequence duplex DNA by alternate-strand triple-helix formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:2435–2437. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Urnov FD, Miller JC, Lee YL, Beausejour CM, Rock JM, Augustus S, Jamieson AC, Porteus MH, Gregory PD, Holmes MC. Highly efficient endogenous human gene correction using designed zinc-finger nucleases. Nature. 2005;435:646–651. doi: 10.1038/nature03556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Faruqi AF, Datta HJ, Carroll D, Seidman MM, Glazer PM. Triple-helix formation induces recombination in mammalian cells via a nucleotide excision repair-dependent pathway. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000;20:990–1000. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.3.990-1000.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petit C, Sancar A. Nucleotide excision repair: from E. coli to man. Biochimie. 1999;81:15–25. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(99)80034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Batty DP, Wood RD. Damage recognition in nucleotide excision repair of DNA. Gene. 2000;241:193–204. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00489-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]