Summary

The activity and expression of plasma membrane NADH coenzyme Q reductase is increased by calorie restriction (CR) in rodents. Although this effect is well established and is necessary for CR's ability to delay aging, the mechanism is unknown. Here we show that the Saccharomyces cerevisiae homolog, NQR1, resides at the plasma membrane and when overexpressed extends both replicative and chronological lifespan. We show that NQR1 extends replicative lifespan in a SIR2-dependent manner by shifting cells towards respiratory metabolism. Chronological lifespan extension, in contrast, occurs via a SIR2-independent decrease in ethanol production. We conclude that NQR1 is a key mediator of lifespan extension by CR through its effects on yeast metabolism and discuss how these findings could suggest a function for this protein in lifespan extension in mammals.

Keywords: Plasma membrane, coenzyme Q reductase, NQR1, coenzyme Q, replicative lifespan, chronological lifespan, dietary restriction

Introduction

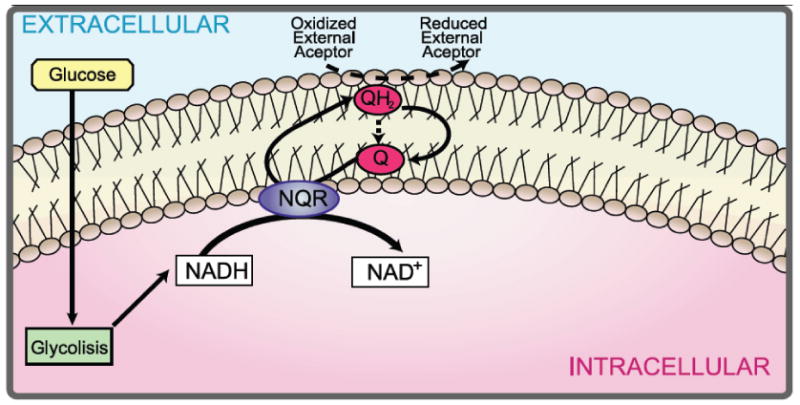

The NAD(P)H-dependent plasma membrane redox system (PMRS) of mammalian cells regulates fasting-induced apoptosis through the trans-plasma membrane redox system Navas et al. (2007). Figure 1 shows a simple scheme of the basic PMRS components in eukaryotic cells. The PMRS regulates apoptosis in part through maintaining coenzyme Q (Q) in its reduced state (QH2). QH2 specifically inhibits the magnesium-dependent neutral sphingomyelinase which prevents the initiation of apoptosis Van Maldergem et al. (2002). Cytochrome b5 reductase is the major PMRS protein responsible for Q reduction, accomplished through the oxidation of NADH Villalba et al. (1995).

Figure 1. The plasma membrane redox system.

Scheme of the plasma membrane redox system where electrons move from internal electron donor such as NADH to external oxidants through the reduction of Q to QH2.

The PMRS is activated in mitochondrial-deficient ρ° cells, allowing the maintenance of cytosolic NAD+/NADH ratios in the absence of respiration Hyun et al. (2007). Navas and colleagues have demonstrated that activation of the PMRS increases both the NAD+/NADH ratio and total cellular NAD+ in mammals Navas et al. (1986). Conversely, inhibition of the PMRS increases apoptosis and this effect is independent of mitochondria Macho et al. (1999).

PMRS function is decreased with age, and this down-regulation can be partially prevented by calorie restriction De Cabo et al. (2004); Hyun et al. (2006). Increased PMRS activity improves membrane homeostasis and resistance to oxidative stress by maintaining water- and lipid-soluble antioxidants in their reduced states Navas et al. (2007). Despite the well-characterized antioxidant function of the PMRS its connection to cellular metabolism is not fully understood.

CR, undernutrition without malnutrition, is the only dietary intervention that extends mean and maximum lifespan in all organisms tested, including yeast Bishop & Guarente (2007). CR extends replicative lifespan (RLS) in yeast by activating Sir2p, an NAD+-dependent deacetylase Lin et al. (2000). Chronological lifespan (CLS) is also extended by CR but through a SIR2-independent mechanism Smith et al. (2007). Knockout of SIR2 can further extend CLS under extreme CR or starvation Fabrizio et al. (2005). The common link between RLS and CLS extension in yeast seems to be respiratory metabolism. CR is the only nutritional intervention that increases both kinds of yeast longevity, and both apparently depend on an upregulation of respiration. It has been proposed that RLS extension by CR requires respiration Lin et al. (2002), but different results from other groups are in disagreement with this conclusion Bishop & Guarente (2007). A TOR1 deletion increases CLS through the upregulation of respiration Bonawitz et al. (2007). Further, CR can produce both kinds of lifespan extension by enhancing respiratory rate and decreasing mitochondrial oxidative stress Barros et al. (2004). In both cases, an increased respiration induces a rise in the NAD+/NADH ratio that activates Sir2p Lin et al. (2004). However, the proper analysis of NAD+ and NADH concentrations is highly conflictive and different technical approaches were used leading to contradictory interpretations to CR effect on lifespan extension in yeast Anderson et al. (2003); Lin et al. (2004)

A variety of genes have been shown to mimic CR-dependent lifespan extension in yeast Bishop & Guarente (2007), but it is unclear how respiration and NAD+/NADH are naturally regulated by CR Belenky et al. (2007a); Belenky et al. (2007b). Considering that the PMRS modulates cytosolic NAD+/NADH, we hypothesized that activation of this system would have a positive effect on longevity and may mediate lifespan extension by CR.

It is still unclear that a shift from fermentative to respiratory metabolism is required to extend lifespan in yeast Lin et al. (2004); Bonawitz et al. (2007), but it has been demonstrated that the activation of respiratory metabolism is required to eliminate ethanol produced in fermentation in conditions that extends CLS Fabrizio et al. (2005). Here, we identify Nqr1p as a yeast plasma membrane-associated cytochrome b5 reductase. We show that NQR1 is induced by CR and that mimicking this induction by overexpression of NQR1 is sufficient to extend both CLS and RLS by promoting respiration and suppressing ethanol production. Thus, we propose that NQR1 encodes a plasma membrane enzyme that mediates lifespan extension by CR by shifting fermentative to respiratory metabolism, probably through modulating the NAD+/NADH ratio.

Results

CR induces the expression of NQR1

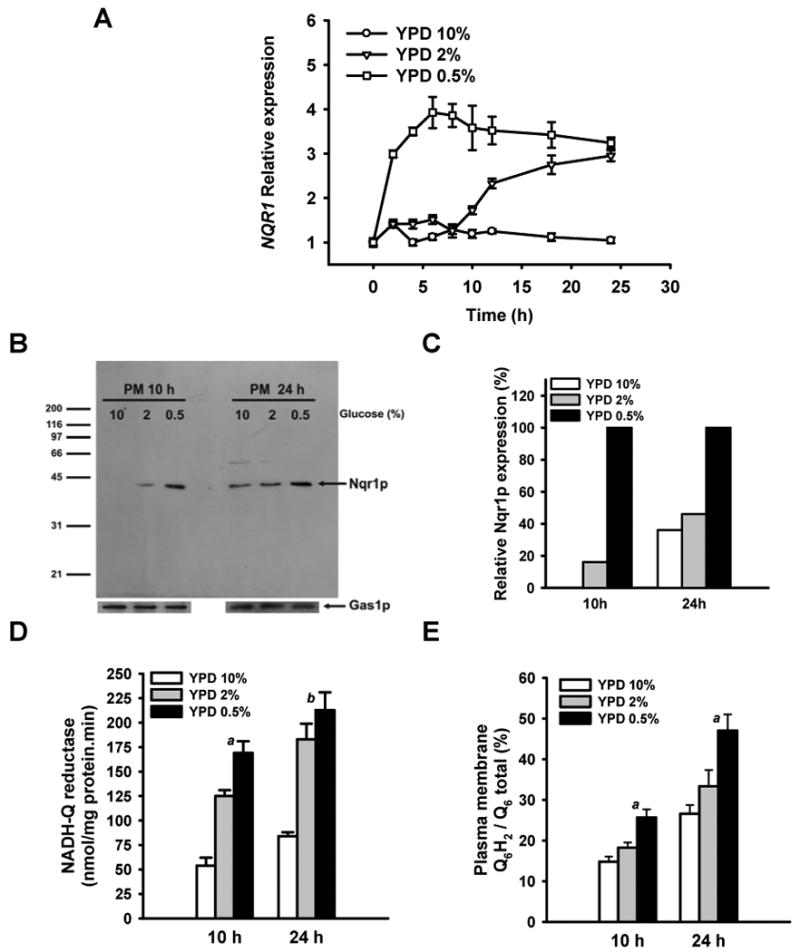

Low glucose concentrations, which some consider to approximate CR in yeast, extend lifespan by increasing respiration Barros et al. (2004) Bonawitz et al. (2007) Lin et al. (2002). Incubating the BY4741 yeast strain in different glucose concentrations led to an increase in CLS inversely to glucose concentration (Figure S1A). The immunolocalization of cytochrome c by confocal microscopy demonstrated the increase of mitochondria as the concentration of glucose was decreased (Figure S2A). These results correlated with the increase of both cytochrome c and Cox1p by immunoblot in these cells (Figure S2D). Further, oxygen consumption (Figure S2B) and NADH-cytochrome c reductase (complex I+III) activity (Figure S2C) were increased as the concentration of glucose dropped indicating the activation of respiration. These analyses were carried out at 16 h to prevent the glucose inhibition of respiratory-associated activities determined in this work. Corresponding growth curves are included in figure S2E. In the same conditions, NQR1 expression was induced earlier and to higher levels in low glucose (0.5%) compared to concentrations of 2 or 10% glucose as assessed by real time-PCR (Figure 2A). NQR1 peptide was also accumulated in cells in yeast growing in low glucose at 10 h and only slightly identified at this time when growing in 2% glucose. No expressed protein was detected in 10% glucose (Figure 2B). At 24 h, NQR1 was in all cells but the concentration was clearly higher at 0.5% glucose (Figure 2B). Relative Nqr1p content in plasma membrane was normalized to Gas1p in figure 2C, showing a neat increase in CR conditions. To demonstrate if this expression was affecting plasma membrane, enriched fractions were obtained and both NADH-Q reductase activity and redox state of Q were analyzed. Figure 2D shows that NADH-Q reductase activity was higher in plasma membrane of yeast as lower were the concentration of glucose in media. Further, the fraction of QH2 in plasma membrane was increasing compared to total Q as the glucose concentration in media was decreasing (Figure 2E). Low concentration of glucose that mimics CR in yeast induced an increase of NQR1 expression and its activity in plasma membrane in the same conditions where respiration was activated.

Figure 2. Low glucose conditions induce the expression and activity of NQR1.

(A) NQR1 shows an early expression during low glucose culture conditions. Wild type cells (BY4741) were inoculated in YPD media containing several glucose concentrations (0.5, 2 and 10%). At the indicated points samples were taken to measure NQR1 expression by RT-PCR. Data corresponds to the average of two independent experiments and each point was calculated with at least three reactions. Data are normalized using ACT1 expression. Control point (0 h) corresponds with the cells used to inoculate the different cultures that were grown in YPD 10% 16 h (B) Plasma membrane samples purified from BY4741 cells cultured in YPD at several glucose concentrations (0.5, 2 and 10%) were analyzed by western blot using a polyclonal anti-NQR1p antibody. The analysis with anti-Gas1p polyclonal antibody was performed as loading control. Cultures were inoculated at 0.1 U OD 660nm/ml and cells were harvested at 10 and 24 hours to purify the plasma membrane. (C) Densitometric analysis of Nqr1p expression normalized with the Gas1p expression. Arbitrary units were calculated for each sample and the highest level was used as 100% in each blot. (D) The same plasma membrane samples were subjected to the measure of the activity of plasma membrane redox system NADH-Q reductase. Activity is expressed as the average ± SD of at least three measurements. a Data are significantly different compared with other data (p< 0.001). b Data are significantly different compared with YPD 10% data (p< 0.001) (E) The same plasma membrane samples were subjected to HPLC-ECD to measure the levels of Q6. The HPLC peaks corresponding to the reduced Q6 (Q6H2) were integrated and compared with total Q6 in order to calculate the proportion against total Q6. a Data are significantly different compared with other data (p< 0.001).

NQR1 encodes for a NADH-dependent cytochrome b5 reductase that reduces Q at the plasma membrane

Analysis in silico of yeast genome showed the existence of the YML125c gene that encoded a putative yeast cytochrome b5 reductase (NQR1) Giaever et al. (2002).

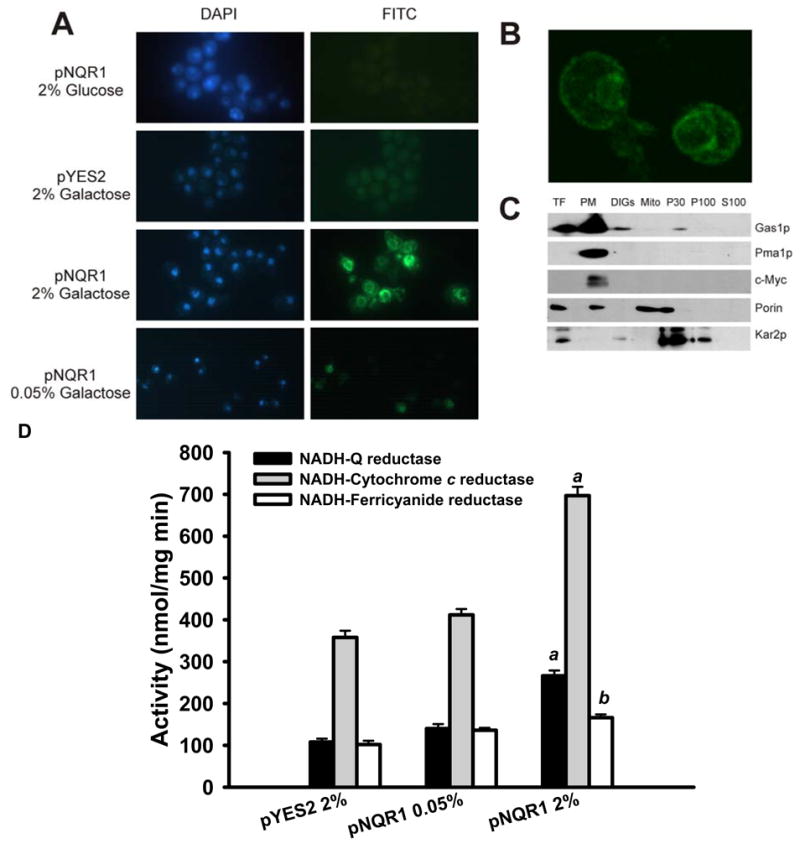

In order to analyze a possible function of NQR1 on longevity, this gene was cloned into a yeast expression vector controlled by the GAL promoter (pYES2.1/V5-His-TOPO from Invitrogen) that allows the fusion of the V5 epitope tag. In 2% galactose, NQR1 was expressed uniformly (Figure 3A), and the signal was located mainly on the plasma membrane and in karmellae (Figure 3B), a special form of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) generated by overexpression of HMG1 (Profant et al., 1999) or plasma membrane AHA1 product in yeast Villalba et al. (1992). Cell fractionation analysis performed using a strain harboring the c-myc tag fused to the nuclear copy of NQR1 showed its location at the plasma membrane (Figure 3C). A high scale study indicated the location of GFP-Nqr1p construction in ER Giaever et al. (2002), but this could be considered an artifact due to the modification introduced in NQR1 after the fusion of a 27 kDa protein as GFP compared with the 34 kDa of Nqr1p. As expected, NQR1 overexpression significantly increased NADH-dependent PMRS activity at the plasma membrane, allowing for increased levels of reduced coenzyme Q (Q) (Figure 3D), and consistent with previous reports, this activity was very sensitive to the specific flavodehydrogenases inhibitor diphenylene iodonium (DPI) (Figure S3) Riganti et al. (2004).

Figure 3. The protein coded by NQR1 is located at the plasma membrane.

(A) Fluorescence microscopy indicates a double localization in plasma membrane and karmellae. Wild type cells transformed with the pNQR1 or pYES2 vector were cultured in galactose (0.05% or 2%) and glucose 2%. pNQR1 is the pYES2 empty vector harboring the coding sequence of the YML125c gene (NQR1) fused with V5 epitope controlled by the GAL promoter. Cells were subjected to epifluorescence microscopy analysis using V5 antibody as primary and anti-mouse labeled with FITC as secondary. Cell nuclei were labeled with DAPI. All images were obtained with the same magnification (×1000). (B) Wild type cells BY4741 over expressing NQR1 analyzed with confocal microscopy. Is possible appreciate with more detail the karmellae structure and the plasma membrane. (C) Mitochondrial localization of NQR1p after over expression is an artifact of mitochondrial purification process. The nuclear copy of the NQR1 gene was labeled with the c-Myc epitope after the insertion of a kanamycin cassette fused in frame. Cell subfractionation performed with labeled cells was analyzed by western blotting using as primary antibodies Gas1p (plasma membrane and DIGs), c-Myc, Pma1p (plasma membrane), Porin (mitochondrial outer membrane) and Kar2p (ER). Western blots corresponds to TF (total fraction), PM (plasma membrane), DIGs (detergent insensitive glycolipid-enriched fractions), Mito (mitochondria), P30 (pellet from 30,000 rpm centrifugation), P100 (pellet from 100,000 rpm centrifugation) and S100 (supernatant from 100,000 rpm centrifugation). (D) Plasma membranes samples from wild type yeast strains strain harboring the control vector (pYES2) and the same vector containing the gene NQR1 (pNQR1) and cultured in several amounts of galactose (0.05% or 2%) were used to measure three typical activities of the plasma membrane redox system. Results are expressed as the average of at least three assays ± SD. a Data are significantly different compared with other data (p< 0.001), b Data are significantly different compared only with pYES2 2% data (p< 0.001).

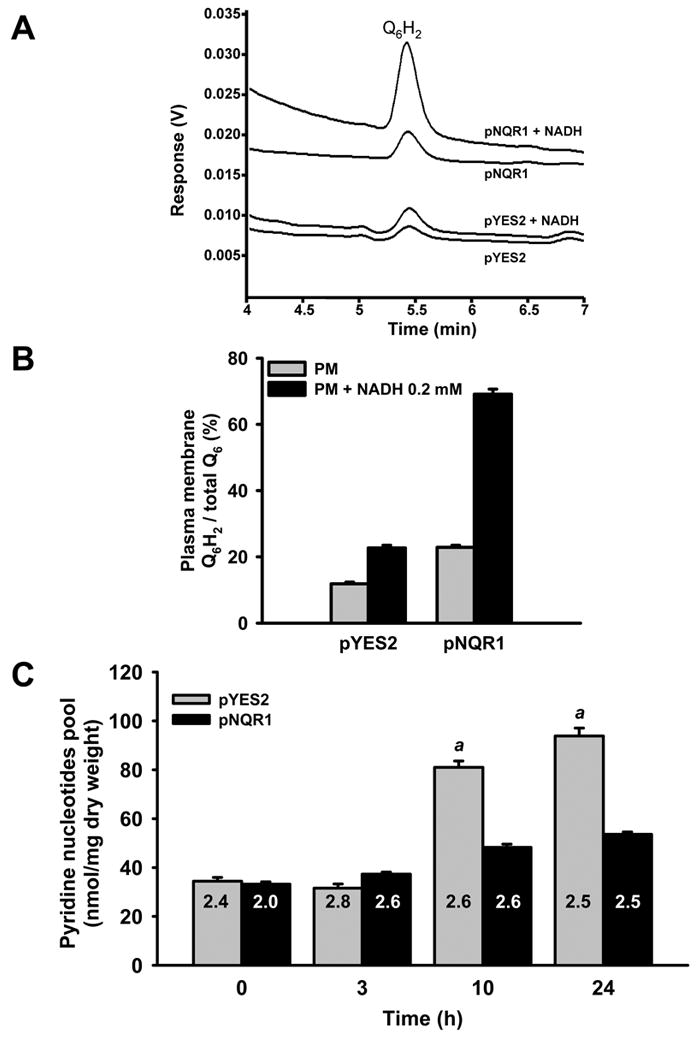

Given that NQR1 transfers electrons to Q6 we analyzed the redox state of the endogenous Q6 at the plasma membrane in cells overexpressing NQR1 (Figure 4A and 4B). The results confirmed that NQR1 overexpressing cells had double amounts of reduced Q6 (Q6H2) from 11.8% to 22.9% of total Q6 when plasma membrane fractions were incubated with NADH. When we induced the overexpression of NQR1, the results were a three fold increase on Q6H2 from 22.7% to 69.1% in the presence of NADH. These results illustrate that NADH is the natural electron donor in both mammals Sun et al. (1992), and yeast Santos-Ocaña et al. (1998a). No significant changes of NAD+/NADH ratio were detected until 24 hours of growth in control and NQR1 overexpressed cells. However, these cells showed a significant decrease of total pyridine nucleotide relative to control, 94 nmol/mg DW compared to 53 nmol/mg DW (Figure 4D). These results would indicate that recycling of NAD+ levels by NQR1 overexpression in yeast is higher than in wildtype cells, demanding less new biosynthesis, although the numerous reactions involving NAD+ or NADH at the cytosol make difficult to interpret these data.

Figure 4. The protein coded by NQR1 requires NADH as electron donor and increases the reduced Q6 at the plasma membrane.

(A) Plasma membrane samples from control (pYES2) and NQR1 over expressing cells (pNQR1) were subjected to lipid extraction and separation by HPLC to analyze the levels of Q6 in both redox states. Some samples were previously incubated in presence of 0.2 mM NADH. (B) The areas of HPLC peaks corresponding to the reduced Q6 (Q6H2) were integrated and compared with total Q6 in order to calculate the proportion against total Q6. PM: Plasmas membrane sample. Data correspond to the integration of three chromatograms from the same plasma membrane sample. Data from plasma membrane obtained from cells expressing NQR1 (pNQR1) were significantly higher (p<0.001) that control samples. Data from plasma membrane samples incubated with NADH were significantly higher (p<0.001) that non incubated samples. (C) The wild type yeast strain BY4741 harboring the control vector (pYES2) and the same vector containing the gene NQR1 (pNQR1) were cultured in 2% galactose. At the indicated times were collected samples to quantify separately the level of pyridine nucleotides. Results correspond to the pool of pyridine nucleotides and are expressed as the average of three assays ± SD and are representative of a set of two experiments. Inside the bars is indicated the ratio NAD+/NADH. a The pool of pyridine nucleotides at 10 and 24 hours was significantly higher in pYES2 cells compared to pNQR1 cells (p<0.001).

NQR1 overexpression extends both RLS and CLS and increases respiration

Since NQR1 plays a role in the regulation of cytosolic NAD+ by increasing the oxidation of NADH, we set out to perform a longevity analysis in NQR1 overexpressing yeast strains. There are two models that are used to study lifespan in yeast, replicative (RLS) and chronological (CLS) lifespan, which correspond to different aspects of the yeast physiology Muller et al. (1980). RLS is defined as the number of buds produced by a mother cell and CLS measures the time in which cells are viable in a nutrient exhausted media.

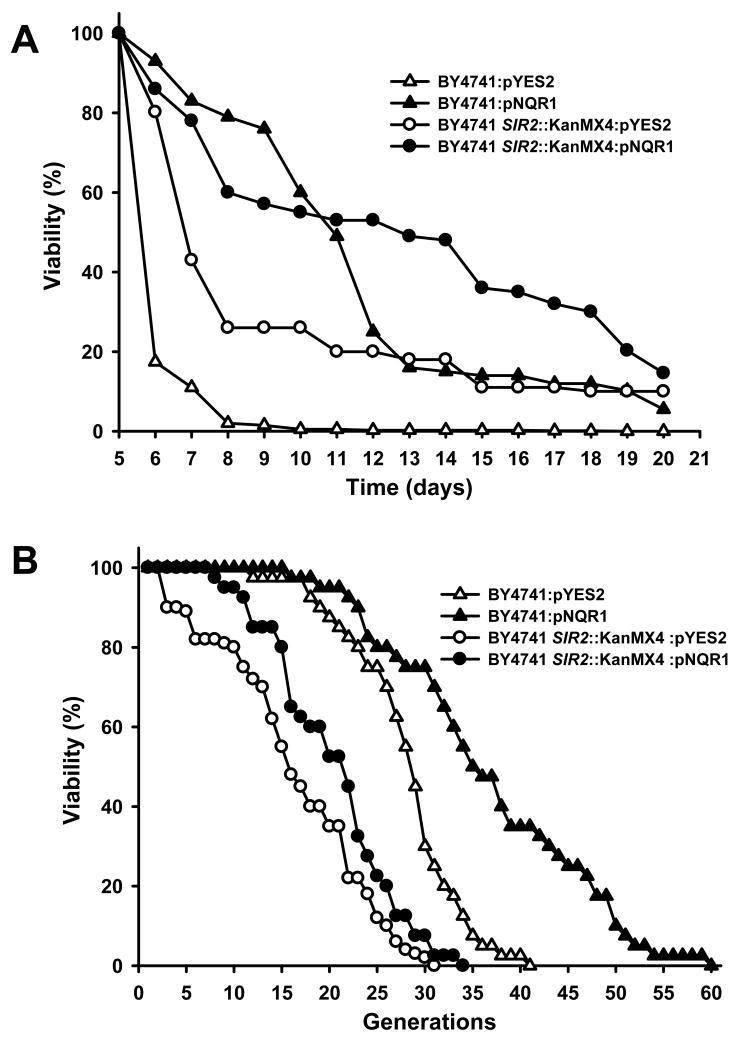

Overexpression of NQR1 in wild type increased mean lifespan from 6.38 to 11.13 days (Figure 5A). Analysis performed on an isogenic sir2Δ strain showed no further changes in mean lifespan, 8.11 to 11.55 days, demonstrating that CLS extension by NQR1 is not dependent on SIR2. Additionally, CLS extension also occured by NQR1 overexpression in other yeast backgrounds such as CEN PK2.1C SIR2∷KanMX4 strains (Figure S1B). It is possible that lifespan extension could be caused by ER accumulation in karmellae. However, this is not apparently the case because the yeast 3-hydroxy 3-methylglutaryl CoA reductase (HMG1) when overexpressed in yeast also accumulated in karmellae with no alteration of CLS (Figure S1C).

Figure 5. NQR1 over expression produces the extension of chronologic and replicative life span.

(A) Chronological life span assay. Liquid cultures containing galactose as carbon source were inoculated with the same number of cells. After 5 days of growth, samples of each culture were taken to measure the cell viability in YPD plates. The first day was used as control (100%). Average life was BY4741:pYES2 (6.38), BY4741:pNQR1 (11.13), BY4741 SIR2∷KMX4:pYES2 (8.11), BY4741 SIR2∷KMX4:pNQR1 (11.55). The survival log rank analysis shown a p<0.001 with the exception of BY4741:pNQR1/SIR2∷KMX4:pNQR1 that was p=0.244. The plots show a representative experiment repeated 3 times with similar results. (B) Replicative life span analysis. Average life was BY4741:pYES2 (28.07), BY4741:pNQR1 (36.75), BY4741 SIR2∷KMX4:pYES2 (16.52), BY4741 SIR2∷KMX4:pNQR1 (20.27) The survival log rank analysis shown a p<0.001 with the exception of BY4741 SIR2∷KMX4:pYES2/BY4741 SIR2∷KMX4:pNQR1 that was p=0.004. The analysis was carried out twice independently with more than 45 cells for each strain each time. Representative results are shown.

Using the same strains, there was a significant extension in RLS in cells overexpressing NQR1, from 28.07 to 36.75 generations (Figure 5B). However, in this case, the effect of NQR1 overexpression was greatly attenuated in strains lacking SIR2 (16.52 vs. 20.27 generations), indicating that this effect is dependent on Sir2p activity. These results clearly demonstrate the role of NQR1 in the extension of both CLS and RLS, representing a common link to both types of lifespan.

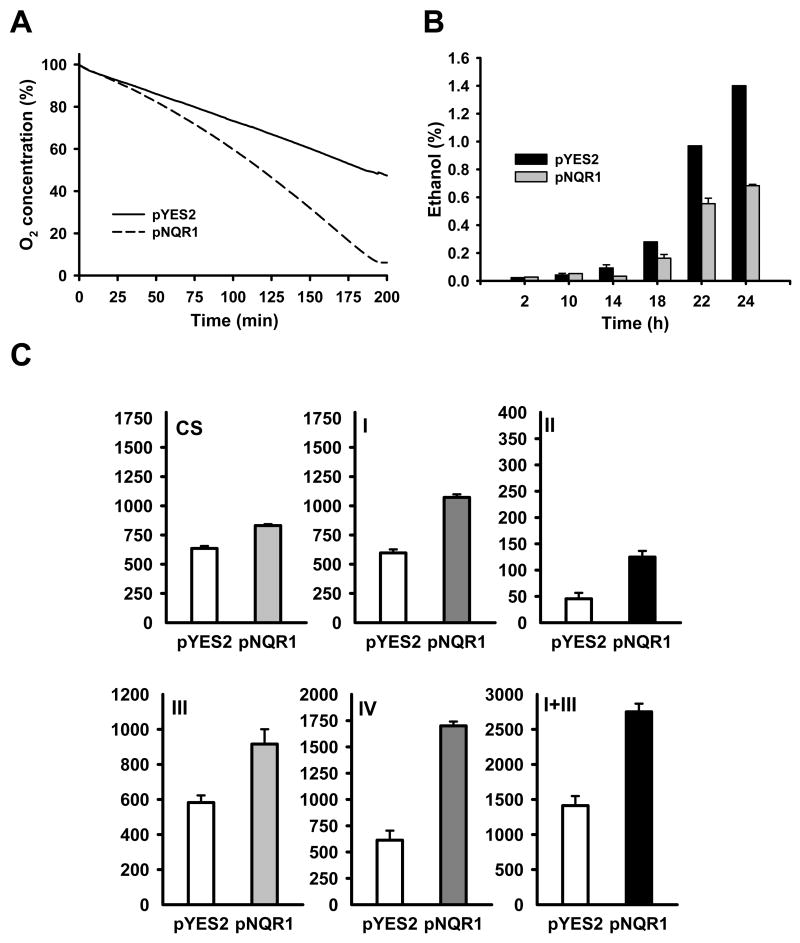

Next, we wondered whether the ability of NQR1 to extend lifespan was due to alterations in oxidative metabolism. We found that NQR1 overexpression in yeast caused a significant increase of O2 consumption, a marker of respiration (Figure 6A), and a decrease on ethanol production, a marker of fermentation (Figure 6B). Ethanol decrease is then correlated with increased respiration rate. Oxidative phosphorylation complexes activities were also significantly increased in these cells (Figure 6C), correlating with the increase of O2 consumption. The increased respiratory metabolism was accompanied with a higher growth rate for cells expressing NQR1 (Figure S4)

Figure 6. Respiratory metabolism is enhanced after NQR1 over expression.

(A) Oxygen consumption was measured in wild type cells (BY4741 strain) harboring the control vector (pYES2) or pNQR1 in a continuous method in parallel. (B) Same cells as previous experiment were used to measure the ethanol production during the growth. Was measured the ethanol concentration in the culture media. (C) Mitochondrial activities measured in wild type cells (BY4741) harboring the control vector (pYES2) or pNQR1. Results show average values and SD for at least three assays and were expressed as nmol/mg mitochondrial protein.min. Data from mitochondria obtained from cells expressing NQR1 (pNQR1) were significantly higher (p<0.001) that control samples. CS, citrate synthase; I, Complex I, NADH-DCPIP reductase; II, Complex II Succinate-DCPIP reductase; III, bc1 complex, decyl ubiquinone-cytochrome c reductase; IV, complex IV cytochrome c oxidase and I+III, NADH-cytochrome c reductase.

Respiration is required for NQR1 overexpression effect

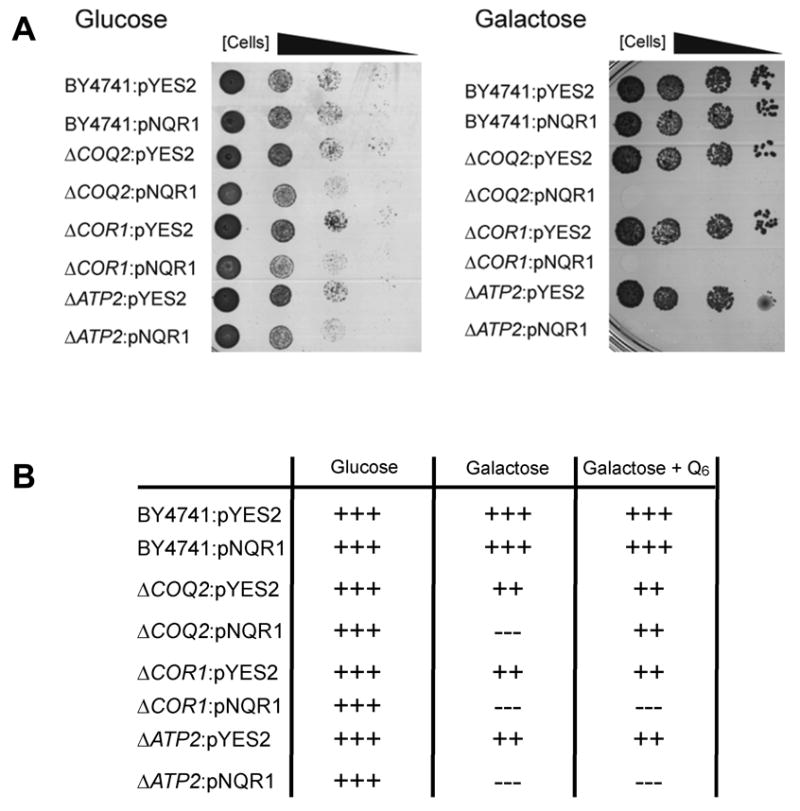

To further illustrate the connection between NQR1 and respiration, we used respiratory-defective yeast strains that lacked genes required for Q6 biosynthesis such as COQ2 or respiratory defective strains unrelated to Q6 biosynthesis such as cor1 and atp2. These strains were transformed with NQR1 and incubated in glucose or galactose (Figure 7A). All strains were able to grow in glucose and galactose but cells that overexpressed NQR1 were only able to grow on glucose. When the experiment was performed in liquid media, the lack of growth in Nqr1p-overexpressing cells was reproduced but the addition of exogenous Q6 to COQ2Δ cells allowed them to resume normal respiration and growth in galactose media but not in the cor1 and atp2 mutants, which are unable to restore respiration even after Q6 addition (Figure 7B). These results are a clear indication that NQR1 acts through the respiratory metabolism in yeast to promote CLS and RLS extension.

Figure 7. NQR1 overexpression requires a respiratory metabolism.

(A) Several strains harboring the control plasmid pYES2 or the pNQR1 plasmid that were spotted in 10-fold dilutions in SDc - ura plates with 2% glucose or 2% galactose in order to analyze the requirement of Q6 to produces life span extension. BY4741, wild type; ΔCOQ2, defective in the Q6 synthesis; ΔCOR1, defective in the bc1 complex; ΔATP2, defective in the ATP synthase complex. (B) The previous experiment was carried out in liquid media in order to complement the respiration deficiency with 2 μM of exogenous Q6. The symbol (+) indicates the rate of growth.

Discussion

Diverse genes have been related to the mechanisms that regulate lifespan in model organisms such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and some of them are conserved in mammals Bishop & Guarente (2007). Many of these genes have been identified because their mutations or overexpression mimic totally or in part CR, indicating that different pathways are affecting lifespan Kaeberlein et al. (2005). Enzymes involved with respiration, bioenergetics, as well as NAD+ biosynthesis pathways are linked to regulation of lifespan, perhaps, because all these enzymes participate in fitness, nutrient sensing, and energy production Lin et al. (2002); Barros et al. (2004); Belenky et al. (2007b); Easlon et al. (2007) The identification of new genes that contribute to balance bioenergetics in yeast, particularly those that facilitate the transition from fermentative to respiratory metabolism, would help us understand the genetics of aging.

The plasma membrane also contributes to the balance of bioenergetics because it contains NADH-dependent dehydrogenases that alter NAD+/NADH ratios Navas et al. (2007), and can support survival in mitochondria-defective ρ° cells Larm et al. (1994); Hyun et al. (2007). These activities are diminished during aging but their decline is prevented by CR in mammals De Cabo et al. (2004); López-Lluch et al. (2005). Yeast plasma membrane also contains a specific NADH-dependent enzyme system that requires Q6 as electron acceptor Santos-Ocaña et al. (1998a); Santos-Ocaña et al. (1998b).

We have shown here that the NQR1-encoded protein localizes in the plasma membrane and reduces Q6 by equivalents from NADH. Overexpression of NQR1 further demonstrated the specificity of NADH as it was observed for the trans-plasma membrane electron transport system in both mammals Sun et al. (1992); Villalba et al. (1995) and yeast Santos-Ocaña et al. (1998a). Cytochrome b5 reductase was identified as responsible for NADH oxidation in liver plasma membrane Navarro et al. (1995). As a consequence, activation of NQR1 at the plasma membrane uses cytosolic NADH that would raise NAD+ level. As a whole, these results indicate the regulation of cytosol NAD+ level or better the NAD+/NADH recycling rate by NQR1 in yeast.

NQR1 has been demonstrated to be an essential protein Giaever et al. (2002) that when overexpressed increased both CLS and RLS. CLS extension was caused although SIR2 was not present, but this effect was only observed in yeast strains with functional respiration. NQR1 must act through a pathway that depends on NAD+/NADH balance, involving respiration, but different to that involving SIR2 Smith et al. (2007), and requiring the increase of respiration Bonawitz et al. (2007). RLS was extended by NQR1 overexpression in a SIR2-dependent manner and mimics CR Lin et al. (2002). When overexpressed in galactose, NQR1 induced a shift from fermentative to respiratory metabolism based on an increase of oxygen consumption and a decrease of ethanol production, along with a rise of respiratory chain maker enzyme activities.

The connection between NQR1 and respiratory bioenergetics is also demonstrated because yeast strains can not grow in galactose when this enzyme is overexpressed in the absence of respiration. Although yeast can produce mainly fermentation with galactose, being about 55% of this sugar accumulated as ethanol Gancedo & Serrano (1989), respiratory shift by NQR1 overexpresion maybe not sufficient to maintain growth in mitochondria deficient strains. This indicates that probably NADH reoxidation rate was enough to prevent ethanol production but without recycling acetaldehyde produced. According to these results, overexpression of NQR1 activates the same respiratory pathway as CR, which also extends both CLS and RLS Barros et al. (2004). The opposite is also demonstrating the connection of NQR1 with respiratory metabolism shift. CR increases the expression of NQR1, raising Q6 reduction activity at the plasma membrane. In parallel, mitochondrial metabolism shifted from glucose fermentation to respiration.

Taken together, these results further support our hypothesis that NQR1 is required to a proper transition from fermentation to respiration having a positive impact on lifespan. Respiratory metabolism is required to allow lifespan induction by CR (low glucose) Lin et al. (2002); Barros et al. (2004), which also increases NQR1 expression.

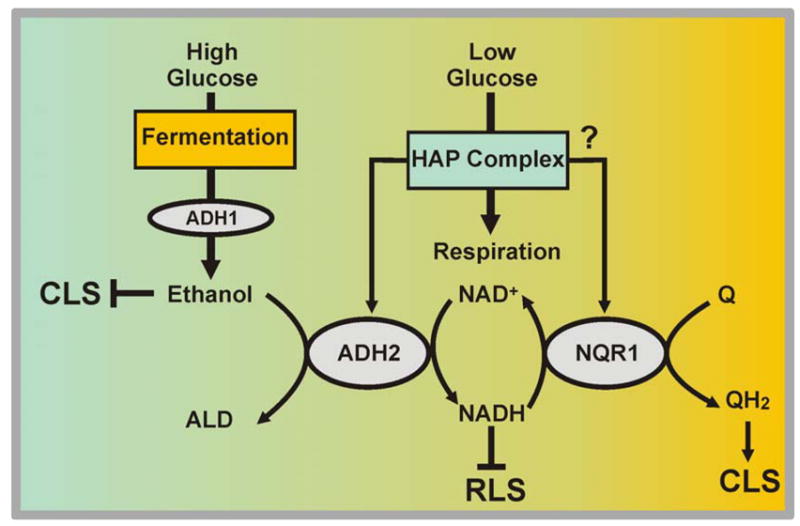

We hypothesize that NQR1 would participate in the regulation of bioenergetics transition from fermentation to respiration through the regulation of NAD+ and NADH pools. A model has been drawn in figure 8. At low levels of glucose (CR) or during the postdiauxic shift, NQR1 cooperates with ADH2 regulating NAD+/NADH homeostasis. NQR1 oxidizes cytosolic NADH by reducing Q at the plasma membrane. NAD+ increase due to this activity will favor Adh2p-dependent ethanol oxidation promoting CLS extension. Likewise, higher levels of NAD+ or low levels of NADH due to NQR1 activity, facilitates extension of RLS via Sirp2 activation.

Figure 8. Function of NQR1 to scavenging NADH produced during fermentative to respiratory transition.

A model to approach the role of NQR1 in NADH oxidation to promote NAD+ raise. This is connected to NAD+ reduction of ADH2 to decrease ethanol accumulation.

We demonstrate here that NQR1 encodes for a member of cytochrome b5 reductase family and it is located at the plasma membrane of yeast. NQR1 specifically requires NADH and Q6 as substrates. Given importance of NAD+ and NADH levels in the modulation of longevity, we show here that NQR1 is a plasma membrane enzyme able to oxidize the excess of NADH and decreases the production of ethanol produced during normal growth in fermentable carbon sources, regulating the transition from fermentative to respiratory metabolism. NQR1 over expression causes the extension of both chronological and replicative lifespan, by regulating this metabolic transition. Thus, activation or increased levels of NQR1 in yeast produce a positive impact on longevity. We propose NQR1 as a novel target for pro-longevity interventions and a therapeutic target for the development of calorie restriction mimetics.

Experimental Procedures

Yeast strains and primers

BY4741 (a, his 3Δ1, leu2Δ0, met15Δ0, ura3Δ0) and BY4741 SIR2∷KanMX4 strains were obtained from Euroscarf (Frankfurt, Germany). CEN PK2.1C strain (a, his 3-Δ1, leu2-3,112, trp1-289, ura3-52, MAL2-8c, MAL3, SUC3) was a gift from the Dr. Karl D. Entian Proft et al. (1995). Yeast strain with the NQR1 gene labeled with the epitope C-myc was obtained according to the method described previously Longtine et al. (1998). The correct insertion of c-myc tag was tested by PCR using a reverse primer corresponding to the 3′ flanking region of the kanamycin cassette (FullK6-R 5′-GAATTCGAGCTCGTTTAAAC-3′) and an internal forward primer located in the NQR1 gene (125iR 5′-TGT TCA TCT GGT CCT TGG TG-3′). The amplicon of the expected size was also analyzed by sequencing (MWG, Ebersberg, Germany). NQR1 gene was cloned from genomic yeast DNA purified from the wild type strain BY4741 by PCR using the forward primer (125FullF 5′-GTT GCC ACC CAA ACT TAT-3′) and the reverse primer (125RevR 5′-GAC TTG ATC GTC GCC AG-3′) to fuse the V5 epitope in frame or the reverse primer (125FullR 5′-GCA GCC TAC TTT CAA CAC A-3′) to clone the intact NQR1 gene. PCR product was cloned in the vector pYES2.1 V5-His TOPO (Invitrogen). HMG1 gene was cloned from genomic yeast DNA purified from the wild type strain BY4741 by PCR using the forward primer (HMG1-F 5′-ATGCCGCCGCTATTCAAG-3′) and the reverse primer (HMG1-R 5′-GATTTAATGCAGGTGACGGA-3′). All PCR products were cloned in the vector pYES2.1 V5-His TOPO (Invitrogen). The NQR1 and HMG1 expression on this vector requires the growth on media containing galactose as carbon source.

Fluorescence methods

Epifluorescence analyses were performed with a Leica (TCS SL) microscopy (Ex 350/Em 470-525). Confocal microscopy was performed with a Leica (TCS SP2) equipment (Ex Argon 488-514/Em 525). Sample preparation was performed according to Pringle et al. (1991) with minor modifications. As primary antibodies, 1:200 anti-V5 (Invitrogen) and anti-cytochrome c 1:200 (a gift of the Dr. K. Koehler, UCLA) were used. As secondary antibodies 1:100 anti-rabbit FITC (Molecular Probes) and 1:100 anti-mouse FITC (Santa Cruz) were used.

Cell subfractionation

Plasma membrane purification was performed according to Serrano (1988), DIGs according to Bagnat et al. (2000), mitochondria according to Glick & Pon (1995), karmellae according to Villalba et al. (1992), ER, P30, P100 and S100 fractions were purified after successive differential centrifugation of S12 fraction obtained from mitochondrial purification as were described previously.

Life span analyses

CLS analysis was performed as indicated by Fabrizio & Longo (2003). Briefly cells were incubated in either minimal medium containing galactose (SDC-ura) or YPD and CLS was monitored in expired medium after the fifth day by measuring colony-forming units (CFUs) every 24 hours. In CLS experiments with high glucose the measuring of CFUs was initiated after the first day. The number of CFUs at day 5 was considered as the 100% of initial survival, required to calculate the age-dependent mortality. RLS analysis was performed by micromanipulation as described Lin et al. (2000). These assays were carried out in yeast strains that were previously cultured in galactose to accumulate Nqr1p.

Enzymatic determinations

Plasma membrane redox activities were measured according to the method previously described Santos-Ocaña et al. (1998b). Mitochondrial respiratory chain activities were performed as described Padilla et al. (2004). Oxygen consumption was performed in parallel with two electrodes using an YSI 5300A Oxygen Biological Monitor at 30°C using a magnetic stirred macro chamber. Ethanol concentration was analyzed enzymatically in cell free media using a Boehringer Mannheim kit.

Western blots were performed with cell extracts obtained as described previously. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Biorad) and blocked with 5% blocking reagent (Biorad) in TBS-Tween 20 0.5%. Membranes were incubated with 1:5000 anti-V5 (Invitrogen), anti-Gas1p 1:10000 (a gift of the Dr. K. Simmons), 1:500 anti-Pma1p (Biomedal, Sevilla, Spain), 1:1000 anti c-myc (Sigma), 1:10000 porin (gift of the Dr. G. Schatz), 1:500 anti-Kar2p (Santacruz) and 1:500 anti-Nqr1p. Anti-Nqr1p is a polyclonal antibody obtained in our laboratory using New Zealand rabbits. A typical protocol involving pre-immune serum extraction, two antigen injection and serum extraction was performed. As antigen 500 μg of karmellae fraction resuspended in 500 μl of PBS was used. Anti-NQR1p was purified by affinity after the immobilization of NQR1p in a nitrocellulose membrane after SDS-PAGE separation performed in a Biorad Miniprotean III equipped with a special comb with a lane of 1 ml. The strip containing Nqr1p was incubated with the original antiserum. Bound anti-Nqr1p was removed from Nqr1p after 15′ of incubation with glycine buffer pH 2.8. Anti-Nqr1p was tested for western blot but was shown ineffective for fluorescence methods.

Pyridine nucleotides determinations

Extraction of the NAD+ and NADH nucleotides was performed as described previously (Lin et al. 2001) with some modification. Cells were grown in SDc -ura 2% galactose and samples were collected by duplicate at 0, 3, 10 and 24 hours in 1.5-mL tubes. For each sample cells were resuspended in 500 μl of cold 50 mM NaOH. Half of the cell solution was mixed with a same volume of 100 mM HCl. Both acid and alkaline cell solutions were incubated 30 min at 60°C to perform the hydrolysis. Samples were neutralized with 100 μl of 400 mM Tris-Base (acid hydrolysis) and with 100 μl of HCl 50 mM and 100 μl of 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8. Acid extraction was performed in one tube to obtain NAD+ and alkali extraction was performed in the other to obtain NADH. After the neutralization samples were subjected to centrifugation at 4°C. Supernatant was transferred to new tubes. Neutralized extracts were used for enzymatic cycling reaction as previously described (Theobald et al. 1997). Pyridine nucleotide concentrations were expressed as nmol/mg dry weight cells.

Coenzyme Q6 determination

Reduced and total Q6 in plasma membrane samples was performed by HPLC-ECD. Plasma membrane samples were extracted with isopropanol (1:1 vol) followed by centrifugation and filtration trough a Millipore PTFE filter. Lipid components were separated by a Beckmann

166-126 HPLC system equipped with a 15-cm Kromasil C-18 column in a column oven set to 40 °C, with a flow rate of 1 ml/min and a mobile phase containing 88:24:10 methanol/ethanol/2-propanol and 13.4 mM lithium perchlorate. Reduced quinones were quantified with an ESA

Coulochem III electrochemical detector (ECD) and a 5010 analytical cell (E1, -500 mV; E2, 500 mV) were used. To quantify total Q6 samples were oxidized with a pre-column cell set in oxidizing mode (E, -500 mV). As external standards commercial Q6 (Sigma) was used as the oxidized form and the same after BH4 treatment as the reduced form.

Real Time PCR

Yeast total RNA was prepared according the procedures described by the manufacturer with the Perfect RNA Eukaryotic Mini kit from Eppendorf after a cell wall digestion with Zymoliase 20T (Seikagaku Corporation). cDNA was synthesized using the iScript cDNA Synthesis kit from Biorad and RT-PCR was performed using the iQ SYBR Green Supermix from Biorad. ACT1 gene was used as calibrator gene using as primers ACT1-F-TR 5′-CGC TCC TCG TGC TGT C-3′ and ACT1-R-TR 5′-TGT AGA AGG TAT GAT GCC AGA T-3′. NQR1 expression was measured using as primers 125TR-F 5′-TCC GAA GCC GCT ATT GAA G -3′ and 125TR-R 5′-AGA GAT GGA CTT GAC GAC TTG -3′. Each point analyzed was performed with five reactions and at least three reactions were used to calculate the expression. The expression ratio was calculated according to the 2-ΔΔCP method Pfaffl (2001).

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were carried out using the Sigmastat 3.0 (SPSS) statistical package. Survival log rank analyses were calculated for each pair of life span analyses and average lifespan were shown in the datasets.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología, Grant BFU2005-03017/BMC, by APP2E04053 Grant of the Universidad Pablo de Olavide, and in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health.

References

- Anderson RM, Latorre-Esteves M, Neves AR, Lavu S, Medvedik O, Taylor C, Howitz KT, Santos H, Sinclair DA. Yeast Life-Span Extension by Calorie Restriction Is Independent of NAD Fluctuation. Science. 2003;302:2124–2126. doi: 10.1126/science.1088697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagnat M, Keränen S, Shevchenko A, Shevchenko A, Simons K. Lipid rafts function in biosynthetic delivery of proteins to the cell surface in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:3254–3259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.060034697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros MH, Bandy B, Tahara EB, Kowaltowski AJ. Higher respiratory activity decreases mitochondrial reactive oxygen release and increases life span in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:49883–49888. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408918200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belenky P, Bogan KL, Brenner C. NAD+ metabolism in health and disease. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007a;32:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belenky P, Racette FG, Bogan KL, McClure JM, Smith JS, Brenner C. Nicotinamide riboside promotes Sir2 silencing and extends lifespan via Nrk and Urh1/Pnp1/Meu1 pathways to NAD+ Cell. 2007b;129:473–484. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop NA, Guarente L. Genetic links between diet and lifespan: shared mechanisms from yeast to humans. Nat Rev Genet. 2007 doi: 10.1038/nrg2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonawitz ND, Chatenay-Lapointe M, Pan Y, Shadel GS. Reduced TOR signaling extends chronological life span via increased respiration and upregulation of mitochondrial gene expression. Cell Metab. 2007;5:265–277. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Cabo R, Cabello R, Rios M, Lopez-Lluch G, Ingram DK, Lane MA, Navas P. Calorie restriction attenuates age-related alterations in the plasma membrane antioxidant system in rat liver. Exp Gerontol. 2004;39:297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easlon E, Tsang F, Dilova I, Wang C, Lu SP, Skinner C, Lin SJ. The dihydrolipoamide acetyltransferase is a novel metabolic longevity factor and is required for calorie restriction-mediated life span extension. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:6161–6171. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607661200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrizio P, Gattazzo C, Battistella L, Wei M, Cheng C, McGrew K, Longo VD. Sir2 blocks extreme life-span extension. Cell. 2005;123:655–667. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrizio P, Longo VD. The chronological life span of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Aging Cell. 2003;2:73–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1474-9728.2003.00033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gancedo C, Serrano R. Energy-Yielding metabolism. Academic Press; 1989. pp. 205–259. [Google Scholar]

- Giaever G, Chu AM, Ni L, Connelly C, Riles L, Veronneau S, Dow S, Lucau-Danila A, Anderson K, Andre B, Arkin AP, Astromoff A, El-Bakkoury M, Bangham R, Benito R, Brachat S, Campanaro S, Curtiss M, Davis K, Deutschbauer A, Entian KD, Flaherty P, Foury F, Garfinkel DJ, Gerstein M, Gotte D, Guldener U, Hegemann JH, Hempel S, Herman Z, Jaramillo DF, Kelly DE, Kelly SL, Kotter P, LaBonte D, Lamb DC, Lan N, Liang H, Liao H, Liu L, Luo C, Lussier M, Mao R, Menard P, Ooi SL, Revuelta JL, Roberts CJ, Rose M, Ross-Macdonald P, Scherens B, Schimmack G, Shafer B, Shoemaker DD, Sookhai-Mahadeo S, Storms RK, Strathern JN, Valle G, Voet M, Volckaert G, Wang CY, Ward TR, Wilhelmy J, Winzeler EA, Yang Y, Yen G, Youngman E, Yu K, Bussey H, Boeke JD, Snyder M, Philippsen P, Davis RW, Johnston M. Functional profiling of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Nature. 2002;418:387–391. doi: 10.1038/nature00935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick BS, Pon LA. Isolation of highly purified mitochondria from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods In Enzymology. 1995;260:213–223. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)60139-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyun DH, Emerson SS, Jo DG, Mattson MP, de Cabo R. Calorie restriction up-regulates the plasma membrane redox system in brain cells and suppresses oxidative stress during aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19908–19912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608008103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyun DH, Hunt ND, Emerson SS, Hernandez JO, Mattson MP, de Cabo R. Up-regulation of plasma membrane-associated redox activities in neuronal cells lacking functional mitochondria. J Neurochem. 2007;100:1364–1374. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaeberlein M, Kirkland KT, Fields S, Kennedy BK. Genes determining yeast replicative life span in a long-lived genetic background. Mech Ageing Dev. 2005;126:491–504. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larm JA, Vaillant F, Linnane AW, Lawen A. Up-regulation of the plasma membrane oxidoreductase as a prerequisite for the viability of human Namalwa ° cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;296:30097–30100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SJ, Defossez PA, Guarente L. Requirement of NAD and SIR2 for life-span extension by calorie restriction in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science. 2000;289:2126–2128. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5487.2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SJ, Ford E, Haigis M, Liszt G, Guarente L. Calorie restriction extends yeast life span by lowering the level of NADH. Genes Dev. 2004;18:12–16. doi: 10.1101/gad.1164804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SJ, Kaeberlein M, Andalis AA, Sturtz LA, Defossez PA, Culotta VC, Fink GR, Guarente L. Calorie restriction extends Saccharomyces cerevisiae lifespan by increasing respiration. Nature. 2002;418:344–348. doi: 10.1038/nature00829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine MS, McKenzie A, 3rd, Demarini DJ, Shah NG, Wach A, Brachat A, Philippsen P, Pringle JR. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998;14:953–961. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<953::AID-YEA293>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Lluch G, Rios G, Lane MA, Navas P, de Cabo R. Mouse liver plasma membrane redox system activity is altered by aging and modulated by calorie restriction. AGE. 2005 doi: 10.1007/s11357-005-2726-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macho A, Calzado MA, Munoz-Blanco J, Gomez-Diaz C, Gajate C, Mollinedo F, Navas P, Munoz E. Selective induction of apoptosis by capsaicin in transformed cells: the role of reactive oxygen species and calcium. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:155–165. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller I, Zimmermann M, Becker D, Flomer M. Calendar life span versus budding life span of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mech Ageing Dev. 1980;12:47–52. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(80)90028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro F, Villalba JM, Crane FL, McKellar WC, Navas P. A phospholipid-dependent NADH-Coenzyme Q reductase from liver plasma membrane. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;212:138–143. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navas P, Sun IL, Morre DJ, Crane FL. Decrease of NADH in HeLa cells in the presence of transferrin or ferricyanide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1986;135:110–115. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(86)90949-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navas P, Villalba JM, de Cabo R. The importance of plasma membrane coenzyme Q in aging and stress responses. Mitochondrion. 2007;7(Suppl):S34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla S, Jonassen T, Jimenez-Hidalgo MA, Fernandez-Ayala DJM, Lopez-Lluch G, Marbois B, Navas P, Clarke CF, Santos-Ocana C. Demethoxy-Q, An Intermediate of Coenzyme Q Biosynthesis, Fails to Support Respiration in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Lacks Antioxidant Activity. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:25995–26004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400001200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle JR, Adams AE, Drubin DG, Haarer BK. Immunofluorescence methods for yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:565–602. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94043-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proft M, Kötter P, Hedges D, Bojunga N, Entian KDCQsyf. CAT5, a new gene necessary for derepression of gluconeogenic enzymes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO Journal. 1995;14:6116–6126. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00302.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riganti C, Gazzano E, Polimeni M, Costamagna C, Bosia A, Ghigo D. Diphenyleneiodonium inhibits the cell redox metabolism and induces oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:47726–47731. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406314200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Ocana C, Córdoba F, Crane FL, Clarke CF, Navas P. Coenzyme Q6 and iron reduction are responsible for the extracellular ascorbate stabilization at the plasma membrane of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The Journal Of Biological Chemistry. 1998a;273:8099–8105. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.14.8099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Ocana C, Villalba JM, Córdoba F, Padilla S, Crane FL, Clarke CF, Navas PCQsyf. Genetic evidence for coenzyme Q requirement in plasma membrane electron transport. Journal Of Bioenergetics And Biomembranes. 1998b;30:465–475. doi: 10.1023/a:1020542230308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano R. H+-ATPase from plasma membranes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Avena sativa roots: purification and reconstitution. Methods Enzymol. 1988;157:533–544. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)57102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DL, Jr, McClure JM, Matecic M, Smith JS. Calorie restriction extends the chronological lifespan of Saccharomyces cerevisiae independently of the Sirtuins. Aging Cell. 2007;6:649–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun IL, Sun EE, Crane FL, Morré DJ, Lindgren A, Löw H. Requirements for coenzyme Q in plasma membrane electron transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:11126–11130. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.23.11126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Maldergem L, Trijbels F, DiMauro S, Sindelar PJ, Musumeci O, Janssen A, Delberghe X, Martin JJ, Gillerot Y. Coenzyme Q-responsive Leigh's encephalopathy in two sisters. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:750–754. doi: 10.1002/ana.10371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villalba JM, Navarro F, Córdoba F, Serrano A, Arroyo A, Crane FL, Navas P. Coenzyme Q reductase from liver plasma membrane: Purification and role in trans-plasma-membrane electron transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4887–4891. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.4887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villalba JM, Palmgren MG, Berberian GE, Ferguson C, Serrano R. Functional expression of plant plasma membrane H(+)-ATPase in yeast endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:12341–12349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.