Abstract

The current effectiveness of HAART in the management of HIV infection is compromised by the emergence of extensively cross-resistant strains of HIV-1, requiring a significant need for new therapeutic agents. Due to its crucial role in viral maturation and therefore HIV-1 replication and infectivity, the HIV-1 protease continues to be a major development target for antiretroviral therapy. However, new protease inhibitors must have higher thresholds to the development of resistance and cross-resistance. Research has demonstrated that the binding characteristics between a protease inhibitor and the active site of the HIV-1 protease are key factors in the development of resistance. More specifically, the way in which a protease inhibitor fits within the substrate consensus volume, or “substrate envelope”, appears to be critical. The currently available inhibitors are not only smaller than the native substrates, but also have a different shape. This difference in shape underlies observed patterns of resistance because primary drug-resistant mutations often arise at positions in the protease where the inhibitors protrude beyond the substrate envelope but are still in contact with the enzyme. Since all currently available protease inhibitors occupy a similar space (in spite of their structural differences) in the active site of the enzyme, the specific positions where the inhibitors protrude and contact the enzyme correspond to the locations where most mutations occur that give rise to multidrug-resistant HIV-1 strains. Detailed investigation of the structure, thermodynamics and dynamics of the active site of the protease enzyme is enabling the identification of new protease inhibitors that more closely fit within the substrate envelope and therefore decrease the risk of drug resistance developing. The features of darunavir, the latest FDA-approved protease inhibitor, include its high binding affinity (Kd = 4.5 × 10–12 M) for the protease active site, the presence of hydrogen bonds with the backbone, and its ability to fit closely within the substrate envelope (or consensus volume). Darunavir is potent against both wild-type and protease inhibitor-resistant viruses in vitro, including a broad range of over 4000 clinical isolates. Additionally, in-vitro selection studies with wild-type HIV-1 strains have shown that resistance to darunavir develops much more slowly and is more difficult to generate than for existing protease inhibitors. Clinical studies have shown that darunavir administered with low-dose ritonavir (darunavir/ritonavir) provides highly potent viral suppression (including significant decreases in HIV viral load in patients with documented protease inhibitor resistance) together with favorable tolerability. In conclusion, as a result of its high binding affinity for and overall fit within the active site of HIV-1 protease, darunavir has a higher genetic barrier to the development of resistance and better clinical efficacy against multidrug-resistant HIV relative to current protease inhibitors. The observed efficacy, safety and tolerability of darunavir in highly treatment-experienced patients makes darunavir an important new therapeutic option for HIV-infected patients.

Keywords: HIV, Drug resistance, Darunavir, TMC114, Substrate recognition, HIV-1 protease

Introduction

Although HAART has successfully improved the management of HIV infection by reducing mortality and slowing the progression to AIDS, its widespread effectiveness is compromised with the emergence of extensively cross-resistant strains of HIV-11–4. The degree of cross-resistance to different drugs within a drug class has been shown to vary according to the number and type of mutations5. The transmission of drug-resistant HIV is also a growing problem, with 5–25% of newly infected individuals being infected with resistant virus6–9. Despite the use of HAART, incomplete viral suppression and persistent low-level viremia can be associated with the development of clinically significant resistance and poor long-term clinical outcome, even when overt virologic failure is not apparent10–12. For protease inhibitors (PIs), Richman, et al. estimated that 41% of patients with HIV viral load > 500 copies/ml were resistant to one or more of the drugs in the class3.

Nevertheless, despite the challenges of potential drug resistance, HIV protease continues to be a prime target for antiretroviral (ARV) therapy because of its essential role in viral replication13,14. Nine HIV-1 PIs have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Association (FDA): amprenavir, atazanavir, indinavir, lopinavir, nelfinavir, ritonavir, saquinavir, tipranavir, and recently darunavir (previously TMC114). To be effective, PIs should combine the following characteristics: improved binding to the protease, prevention of the development of resistance, high potency against both wild-type and resistant HIV strains, effective and durable virologic suppression, favorable tolerability, and convenience. This article profiles the balance of substrate recognition and reviews the existing HIV-1 PIs, including tipranavir, in comparison with the unique in vitro and clinical properties of the latest FDA-approved PI, darunavir15–17.

The structural and dynamic determinants of substrate recognition in HIV-1 protease

During virion maturation, HIV-1 protease specifically cleaves the posttranslational precursor polyproteins Gag and Gag-Pro-Pol in at least nine non-homologous sites, releasing six structural proteins (matrix, capsid, p2, nucleocapsid, p1, and p6) and four enzymes (protease, reverse transcriptase, RNaseH, and integrase)18. This processing is essential for viral maturation and therefore HIV-1 replication and infectivity. Abolition of protease activity by either deletions or point mutations results in the production of noninfectious viral particles13,19. The HIV-1 protease’s extreme specificity and critical role in viral maturation makes it an attractive target for ARV drugs13,14.

The HIV-1 protease is a small aspartyl protease. Like other retroviral aspartyl proteases20,21 it is active as a symmetric homodimer, but each monomer is only 99 amino acids long. The structure is primarily β-sheet with the active site at the dimer interface. Each monomer contributes one critical aspartic acid22 to form the active enzyme. The dynamics of HIV-1 protease are also critical to function, as the substrate sites within the Gag and Gag-Pro-Pol polyproteins access the active site when two large flexible flaps open23–25 then close over the active site allowing proteolysis of the substrate to occur. The flaps then reopen and allow the cleaved products to be released.

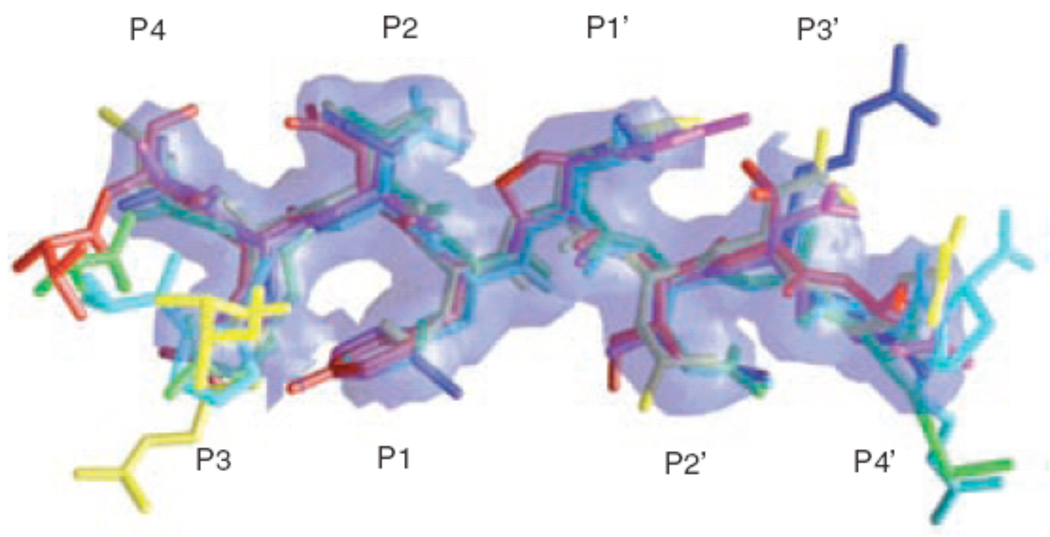

The substrate sequences that HIV-1 protease cleaves are diverse in sequence and asymmetric; however, it is not a promiscuous enzyme, but rather is highly specific. The rate and order in which the sequences are cleaved is site-specific. Crystal structures of peptide complexes have been determined that correspond to the various cleavage sites in Gag and Gag-Pro-Pol26–33. Analysis of the structures of the substrate complexes revealed that although the sequences are diverse, the structures that they form pack into a conserved asymmetric shape31. This asymmetric shape appears to determine the enzyme’s specificity rather than any particular amino acid sequence or hydrogen bonding pattern30,31. The conservation of this shape was determined by the intersection of the van der Waals surfaces of the substrates, and this intersecting volume or consensus volume has been defined as the protease “substrate envelope” or the region within the active site that is most critical for substrate recognition (Fig. 1)15,34.

Figure 1.

Substrate envelope of HIV protease. GRASP model generated from overlapping van der Waals volume of substrate peptides. Red: matrix capsid, green: capsid-p2, blue: p2-nucleocapsid, cyan: p1-p6, magenta: reverse transcriptase-ribonucleaseH, yellow: ribnucleaseH-integrase (reprinted from Chemistry & Biology, Vol. 11, Nancy M King, Moses Prabu-Jeyabalan, Ellen A Nalivaika, and Celia Schiffer, Combating susceptibility to drug resistance: lessons from HIV-1 protease, p1333-8, Copyright 2004, with permission from Elsevier34).

Characterization of PIs – structures and thermodynamics

The HIV PIs were the first success of structure-based drug design22. All of the clinically successful ones are competitive active site inhibitors. They interact with the active site in such a way as to keep the flaps of the enzyme tightly closed over the active site, thus mimicking the transition state and thereby effectively inactivating the enzyme. Most of the inhibitors, even those whose precursors were found through screening libraries, were optimized with successive co-crystal crystal structures35–41.

Chemically, these inhibitors have generally hydrophobic moieties that interact with the mainly hydrophobic S2-S2’ pockets in the active site. Structurally there are two types of HIV PIs – peptidomimetic PIs, which comprise the majority of approved PIs including darunavir, and nonpeptidomimetic PIs, such as tipranavir41.

In addition to structure, isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) has been extensively utilized to characterize the thermodynamics of the binding of these inhibitors to HIV-1 protease34,42–47. Under specified temperature and buffer conditions, thermodynamics allows for the enthalpy and entropy of a molecular interaction to be characterized. The inhibitors vary in binding affinity from nanomolar to picomolar; however to achieve these binding affinities there are a wide variety of different combinations of more favorable entropy or more favorable enthalpy. Many of the first generation inhibitors, despite being designed on the basis of structural interactions, are actually enthalpically unfavorable and are driven into the active site by the entropically favorable action of burial of relatively rigid hydrophobic groups. Recent theories suggest that enthalpically driven inhibitors may be more resilient to resistant variants of HIV-1 protease34,46; however, whether this is universal remains to be verified.

Recently approved PIs

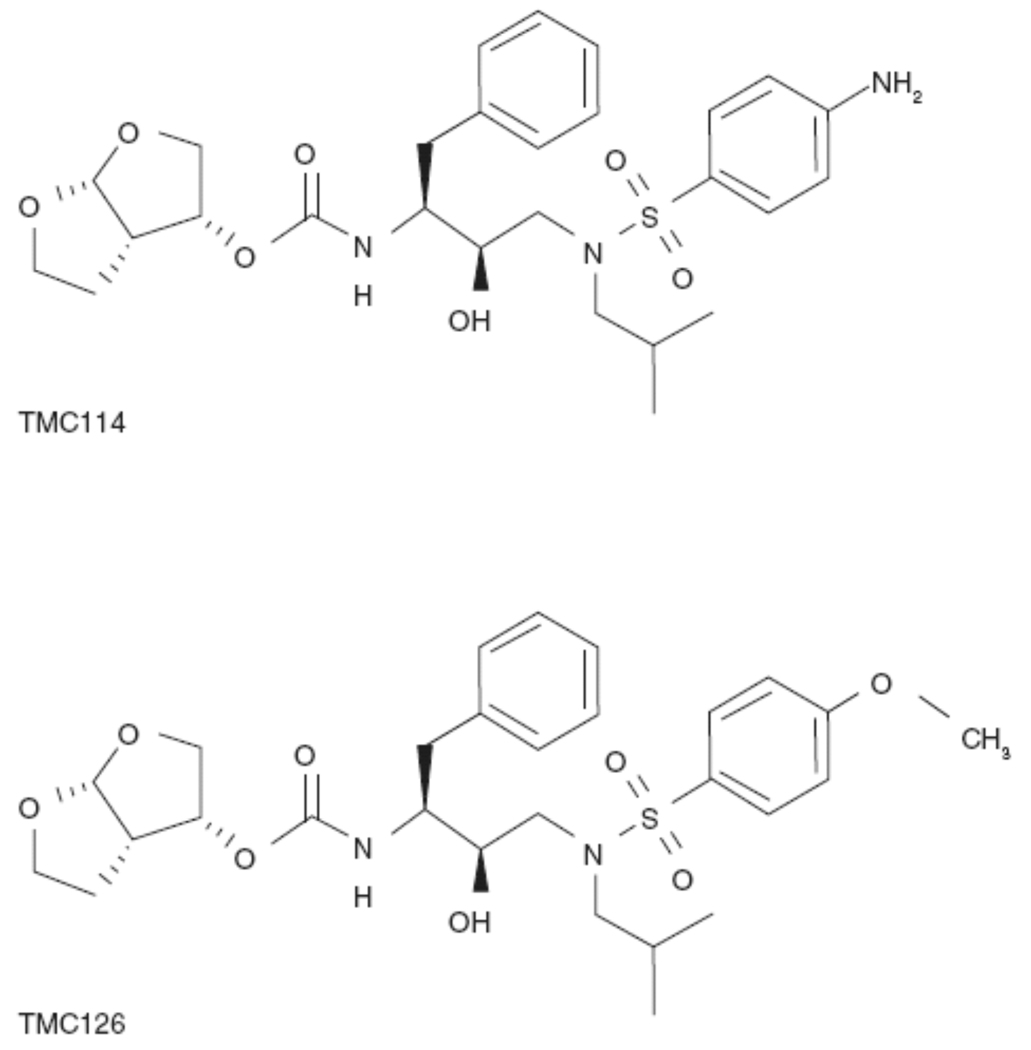

The most recently approved PI, darunavir, is a peptidomimetic PI, containing a 3(R), 3a(S), 6a(R)-bis-tetrahydrofuranylurethane (bis-THF) group. Darunavir is highly potent in vitro and in vivo against a broad range of HIV-1 strains, including wild-type virus and a variety of multidrug-resistant (MDR) clinical strains15,27,48–51. Darunavir was identified in a unique research and development program, which assessed potential PI compounds by profiling their antiviral activity against a panel of recombinant HIV strains derived from highly PI-resistant and cross-resistant clinical isolates. Additionally, several thousand clinical isolates with varying degrees of PI resistance were also used for the evaluation of the most interesting compounds16,51. Two key evaluation criteria were high potency against both wild-type and MDR HIV-1 strains, and a favorable pharmacokinetic (PK) profile following oral administration. From this search, the prototype compound TMC126 was identified. To improve the PK profile of TMC126 while retaining its high potency, a series of closely related compounds, all of which had the bis-THF moiety for improved interaction in the P2-pocket, were synthesized and darunavir was identified as the lead compound for clinical development (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Chemical structure of darunavir (TMC114) and TMC126 (reproduced with permission15).

Although darunavir has some chemical similarities to amprenavir, it binds approximately 100-times more tightly to wild-type protease (Kd = 4.5 × 10–12 M versus Kd = 3.9 × 10–10 M) and 1000-times more tightly than indinavir, nelfinavir, ritonavir, and saquinavir15,52. The unique high-binding affinity of darunavir may partly be due to the bis-THF moiety at P2’17. This moiety forms strong hydrogen bonds with the backbone atoms of residues D29 and D30. These hydrogen bonds may be partially responsible for the very favorable binding enthalpy of darunavir to the wild-type protease (−12.1 kcal/mol)16 and very slow dissociation rate52. Together with further hydrogen bonds between darunavir and the backbone atoms at the base of the active site, the drug mimics the conserved hydrogen bonds of the natural substrates30,31. In contrast, other PIs form more extensive interactions with the protease side-chains48,49.

Tipranavir is another recently approved PI. Tipranavir is nonpeptidomimetic (sulfonamide-containing 5,6-dihydro-4-hydroxy-2-pyrone) and as such is structurally unrelated to the other PIs53. Identified through structure-based drug design, tipranavir is a potent inhibitor of the HIV-1 protease with a dissociation constant for inhibitor binding of Kd = 1.9 × 10–11 M54. A study examining the thermodynamic basis of the potent antiviral activity of tipranavir against PI-resistant mutants found that in contrast to darunavir, the high potency of tipranavir results from a large entropy change (−14.6 kcal/mol) combined with a small enthalpy change (−0.7 kcal/mol)54. The structure of tipranavir allows seven direct hydrogen bonds to be established with conserved residues of the protease enzyme, and makes fewer water-mediated hydrogen bonds compared with other PIs. Together with the retention of structural flexibility, these features allow enthalpic interactions to compensate for conformational entropy losses induced in the presence of resistance mutations. This is also thought to go some way towards explaining the activity of tipranavir against resistant viruses54.

PI resistance and cross-resistance

In general, drug resistance occurs when mutations in the target protein enable it to retain function while no longer being effectively inhibited by the drug34. The high viral replication rate combined with the highly error-prone reverse transcriptase and the selective pressure of therapy cause many drug-resistant mutants of HIV-1 to emerge43,55,56. Since the introduction of PIs, drug-resistant mutations in the protease have become widespread. These mutations render the variant protease resistant to the inhibitor while allowing it to maintain its function in cleaving its natural substrates5,34. Mutations in at least 34 of the 99 residues of HIV-1 protease have been found to have clinical significance56–59. Although only a subset of these mutations, such as D30N, G48V, V82A, I84V, I50V, and I50L, affect inhibitor binding by an alteration of a direct point of contact within the active site, many others alter inhibitor binding by altering the balance between substrate recognition and inhibitor binding. The HIV-1 found in most highly PI-experienced patients has between 5 and 15 mutations in the protease gene56,57. These are often in specific combinations of mutations both inside and outside the active site. Mutations outside the active site may not only impact inhibitor binding, but also compensate for the viability and fitness of the enzyme and thus increase the growth rate of the mutant virus60,61.

Varying degrees of resistance to all of the PIs has been described and cross-resistance among the older PIs is common5,62,63. In a phenotypic and genotypic analysis of ARV drug resistance to indinavir, nelfinavir, ritonavir, and saquinavir in more than 6000 patient isolates from Europe and the USA, phenotypic resistance to any single PI was found in 17–25% of isolates. Cross-resistance was found in 59–80% of those isolates that were resistant (greater than 10-fold increase in inhibitory concentration [EC50]) to at least one PI62. Although certain predominantly primary active site mutations are closely associated with a particular PI64,65, such as D30N with nelfinavir, G48V with saquinavir, I50V with amprenavir, or I50L with atazanavir, others such as V82A and I84V impact almost all of the PIs. The active site mutations are often combined with other common mutational patterns that contribute to PI cross-resistance, including combinations of mutations at L10I, I54V or T, A71V or T, V77I, and L90M56,57,62. The structural similarities between darunavir and amprenavir may contribute to some shared determinants of resistance. Recent studies have indicated that previous use of or resistance to (fos)amprenavir may be associated with a higher level of resistance to darunavir66,67, although in phase IIb trials the impact on virological response to darunavir was minimal68. This commonality potentially limits the success of subsequent therapy following virologic failure of PI-containing regimens, since fewer new mutations may be required to produce viruses that are clinically resistant to the PI(s) in the salvage regimen69.

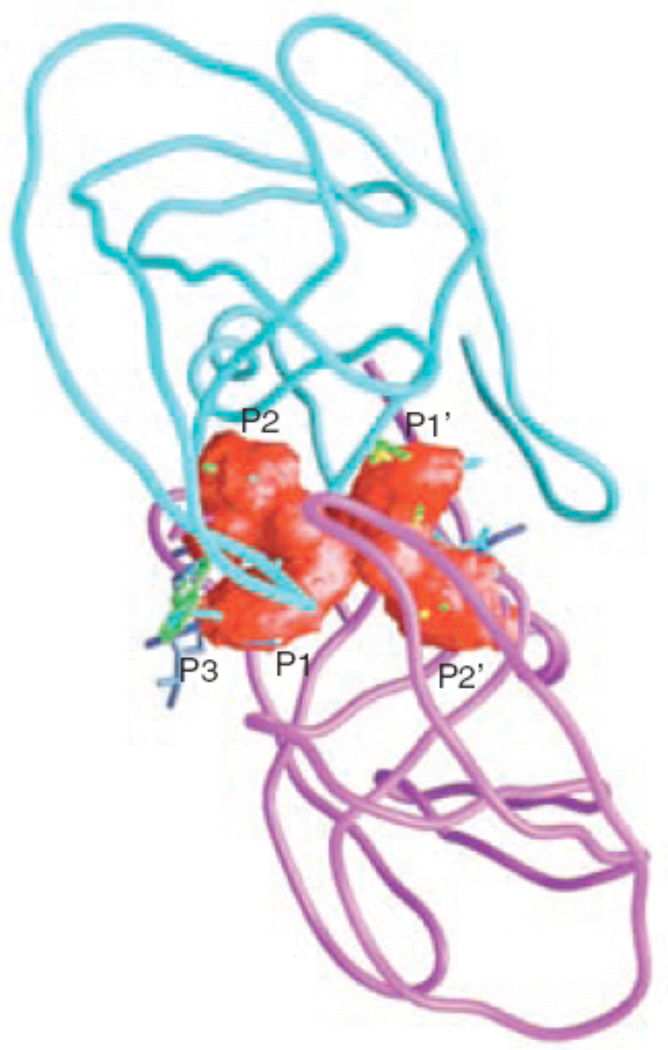

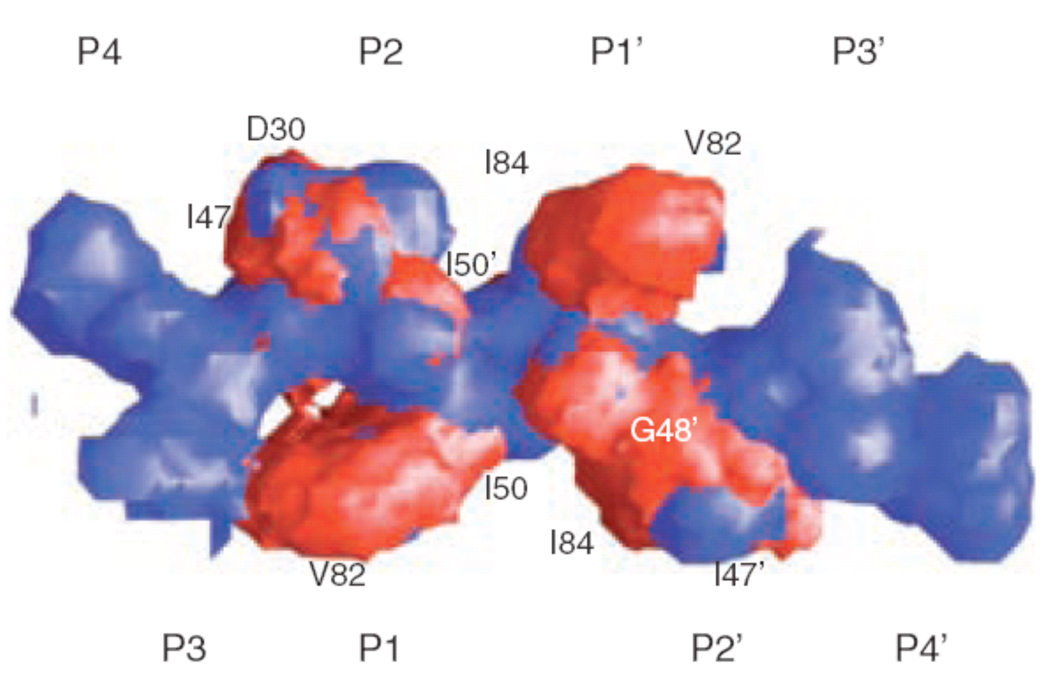

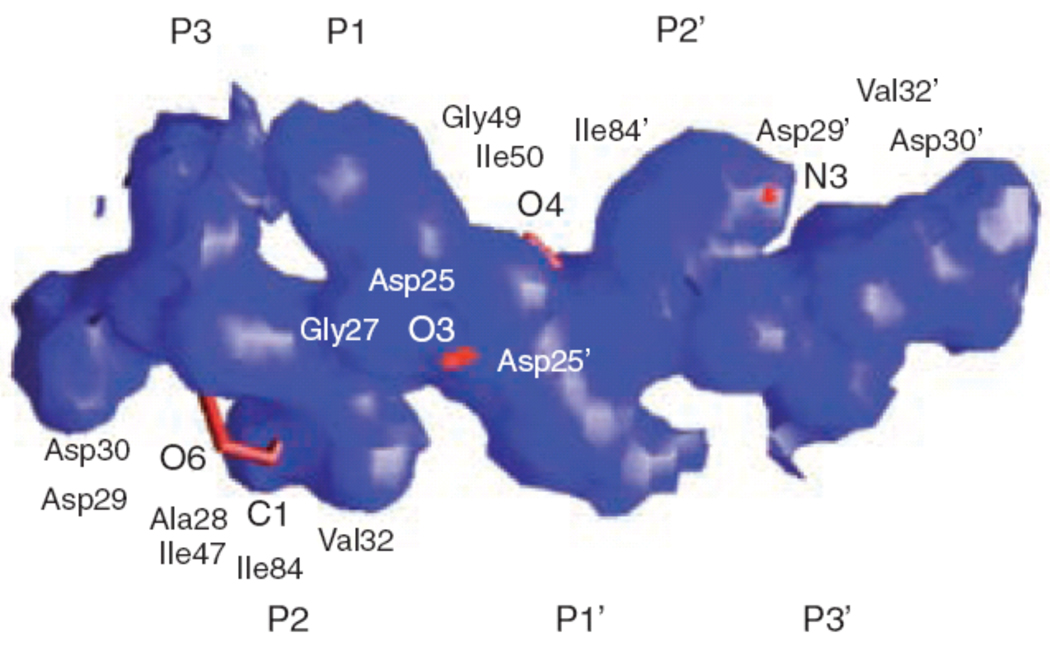

Why is there so much cross-resistance between the PIs? Although there are clear chemical differences between all the currently available PIs, when bound in the active site of HIV-1 protease they occupy a similar space, and even have similar functional groups at similar positions (Fig. 3). As a result, atoms of different PIs frequently come into contact with the protease at the same residues34. Thus, mutations at these residues in HIV-1 protease produce MDR viruses15,34,70. The key molecular recognition question is how do the protease variants with resistance mutations in their active sites, that confer resistance to competitive inhibitors, retain the ability to recognize and cleave substrates and thus maintain viable virus? This retention of activity often occurs without co-evolution of the substrate sequences. A partial answer to this puzzle was found when the inhibitor complexes were superimposed on the substrate complexes32,34 (Fig. 4). Not only are the inhibitors smaller than the substrates, they also have a different shape than the substrates. The superimposition studies found that drug resistance mutations occur at positions where the inhibitors protrude beyond the substrate consensus volume (or substrate envelope) but are still in contact with the enzyme. This explains how resistance can occur without having a significant impact on function, as those residues are more important to inhibitor binding than they are for substrate recognition and thus are prime locations for resistant mutations.

Figure 3.

The inhibitor envelope in red, as it fits within the active site of HIV-1 protease, calculated from overlapping van der Waals volume of five or more of eight inhibitor complexes. The colors of the inhibitors are yellow, Nelfinavir; gray, Saquinavir; cyan, Indinavir; light blue, Ritonavir; green, Amprenavir; magenta, Lopinavir; blue, Atazanavir; and red, Darunavir (reprinted from Chemistry & Biology, Vol. 11, Nancy M King, Moses Prabu-Jeyabalan, Ellen A Nalivaika, and Celia Schiffer, Combating susceptibility to drug resistance: lessons from HIV-1 protease, p1333-8, Copyright 2004, with permission from Elsevier34).

Figure 4.

Superimposition of the substrate consensus volume (blue) with the inhibitor consensus volume (red). Residues that contact with the inhibitors where the inhibitors extend beyond the substrate volume and confer drug resistance when they mutate are labeled (reprinted from Chemistry & Biology, Vol. 11, Nancy M King, Moses Prabu-Jeyabalan, Ellen A Nalivaika, and Celia Schiffer, Combating susceptibility to drug resistance: lessons from HIV-1 protease, p1333-8, Copyright 2004, with permission from Elsevier34).

Avoiding cross-resistance among PIs

For a PI to maintain effectiveness against resistance mutations, two characteristics are required: a high binding affinity for the wild-type protease and resilience to the effect of mutations, i.e. the PI is able to maintain viable binding affinity and effective inhibition in the presence of those mutations32,34,71. The traditional approach to combating drug resistance has included the characterization and targeting of each drug-resistant variant protein to enable the identification of new active inhibitors72,73. However, this is not practical for HIV-1 protease as more than one third of the 99 residues are known to mutate and contribute in various combinations to PI resistance56,57. We have proposed a general strategy of structure-based design to decrease the probability of drug resistance developing, by designing inhibitors that interact only with those residues that are essential for function34. For HIV-1 protease, this would mean developing a PI that is contained within the substrate envelope and thus interacts only with the same residues that are required for substrate recognition. Such an inhibitor would be less susceptible to drug resistance, as any mutation that affects the inhibitor would simultaneously affect the recognition of a substantial proportion of the substrates.

In fact, darunavir and amprenavir more closely mimic substrate interactions because they fit within the substrate consensus volume or substrate envelope better than any of the other PIs (Fig. 5)15,34. The combination of tight binding, mimicking substrate hydrogen bonds and the overall fit within the substrate envelope should provide darunavir with a higher “genetic barrier” to the development of resistance, as the backbone interactions are not changed by mutation. Furthermore, the mutations that perturb darunavir binding will have a negative impact on substrate recognition and cleavage, and are either less likely to occur or will result in reduced viral replication. Thus, based on simple molecular interaction principles, this suggests that darunavir should have greater robustness in treating HIV-1 infection.

Figure 5.

Crystal structure of darunavir superimposed on the structure of the substrate envelope derived from the substrate crystal structures. Atoms that protrude from the envelope are shown in red and labeled. Other labels highlight protease residues within van der Waals contact of the protruding atoms (reproduced with permission15).

This strength was demonstrated when comparing the binding of darunavir to wild-type protease with binding to a prototype MDR HIV-1 protease variant (I84V, V82T). Variant I84V is the most common resistant mutation that affects the binding of every currently used PI. The flexible N-isobutyl group of darunavir interacts with residue 84 (Fig. 5) in the protease active site and allows for conformational adjustments in the ligand and possible retention of binding affinity. However, the binding affinity of darunavir (measured by ITC) was reduced by a factor of 13.3. Nevertheless, despite the reduction in binding affinity to this variant HIV protease, darunavir still binds with a 60 pM binding affinity which is more than 33-fold higher than amprenavir and more than 1.5 orders of magnitude higher than older PIs15. Other recent studies have examined the structure and binding affinity with other resistant variants27,50 and found a maximum of 30-fold loss in binding affinity to the I50V variant, a known amprenavir resistant mutation and a point of contact outside of the substrate envelope (Fig. 5). Thus, the high binding affinity of darunavir appears to provide resilience against the effect of resistance mutations in the HIV-1 protease at the molecular level.

Activity of darunavir against wild-type and resistant strains of HIV, and development of resistance in vitro

Darunavir has demonstrated strong potency against both wild-type and PI-resistant viruses in vitro, including a broad range of over 4000 clinical isolates48,51. In vitro, darunavir showed potent activity against wild-type HIV-1 and HIV-2, with an EC50 of 1 to 5 nM and an EC90 of 2.7 to 13 nM, with no observed cytotoxicity at concentrations up to 100 µM51. Darunavir also demonstrated good activity against 19 recombinant clinical isolates with multiple protease mutations and phenotypic resistance to an average of five PIs. Except for one strain, darunavir showed EC50 of < 10 nM for all isolates compared with EC50 of > 100 nM for nelfinavir, indinavir, ritonavir, amprenavir, saquinavir, and lopinavir. Against 1501 clinical isolates with a four-fold or greater change in EC50 for one or more PI, darunavir inhibited 75% of viruses with an EC50 of < 10 nM and 21% of viruses with an EC50 of 10 to 100 nM. Darunavir was more potent against these PI-resistant strains than any other PI tested (amprenavir, indinavir, lopinavir, nelfinavir, ritonavir, and saquinavir)48.

Koh, et al. also demonstrated that darunavir has potent in vitro activity against wild-type HIV-1 and HIV-2 and MDR clinical HIV-1 strains48. Compared with amprenavir, indinavir, lopinavir, nelfinavir, ritonavir, and saquinavir, which suppressed the infectivity and replication of HIV-1 LAI with EC50 of 17 to 47 nM, darunavir showed superior potency (EC50 3 nM). Darunavir also showed potent activity against HIV-1 Ba-L (EC50 3 nM) and two HIV-2 strains (EC50 3 to 6 nM), activity that was greater than that of the other PIs tested.

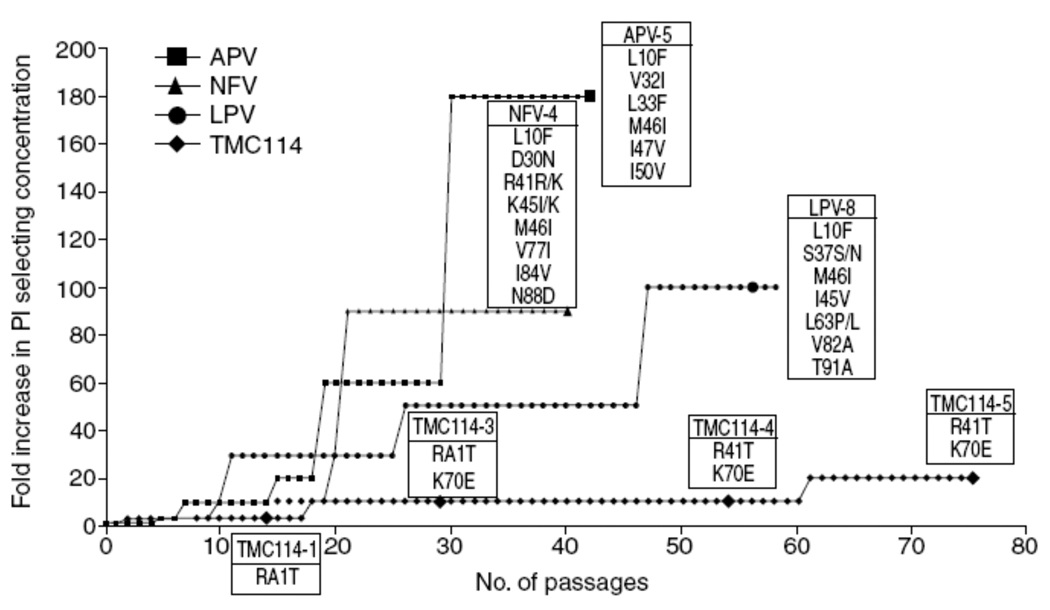

Preliminary data from in vitro selection studies with wild-type HIV-1 strains have shown that resistance to darunavir develops much slower and is more difficult to generate than for existing PIs16,51. De Meyer, et al. showed that selection of resistant HIV with amprenavir, lopinavir, and nelfinavir was more rapid and easier than with darunavir and resulted in the emergence of strains carrying clinically relevant PI resistance-associated mutations (Fig. 6)16,51. The concentrations of these PI could readily be increased to > 1 µM and still allow virus replication. In contrast, the concentration of darunavir could not be increased rapidly and virus replication did not occur at concentrations > 200 nM (Fig. 6). Moreover, the mutations emerging in the selected strains (R41T and K70E) have never been associated with resistance to PIs, and when introduced in a wild-type genetic background by site-directed mutagenesis, did not cause decreased susceptibility to darunavir71.

Figure 6.

In vitro selection of resistant HIV from wild-type in the presence of amprenavir, lopinavir, nelfinavir, or darunavir (TMC114) in sequential passage experiments. Each passage represents 3–4 days with passage 75 representing a total of 260 days. Enlarged symbols indicate genotypes of viruses selected at defined times and list all genotypic changes from the original HIV-1 LAI strain. Curves are normalized and starting concentrations were 10, 20, 100 and 100 nM for darunavir (TMC114), lopinavir, amprenavir and nelfinavir respectively (reproduced with permission51).

Clinical activity

In clinical studies, darunavir is administered together with low-dose ritonavir (darunavir/ritonavir). Published results from one phase IIa clinical study and two phase IIb studies indicate that darunavir/ritonavir has potent antiviral activity in PI-experienced patients75–77. In the 24-week dose-finding portion of two large, randomized and controlled 144-week phase IIb studies (POWER 1 [TMC114-C213] and POWER 2 [TMC114-C202]), patients were nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI)-, nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI)- and PI-experienced, had at least one primary PI mutation (according to the IAS-USA guidelines) and had viral load ≥ 1000 copies/ml at screening76,77. Both studies were of similar design. Patients were randomized to receive either investigator-selected PI(s) or one of four darunavir/ritonavir doses: 400/100 mg 1/d, 800/100 mg 1/d, 400/100 mg 2/d or 600/100 mg 2/d; all regimens were given in combination with an optimized background regimen (OBR; at least two NRTI with or without enfuvirtide). Patients were stratified by the number of primary PI mutations, by the use of enfuvirtide and by screening viral load. The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients with a decrease in viral load of ≥ 1 log10 HIV-RNA copies/ml at week 24. Secondary endpoints included the decrease in viral load from baseline, the proportion of patients with HIV-RNA < 50 copies/ml, and the mean change in CD4 cell count at week 24.

The baseline characteristics showed that patients in the POWER 2 study had somewhat more advanced disease (longer duration of infection, lower baseline CD4 and higher viral load), more patients had virus resistant to all commercially available PIs (71 vs. 63%) and a greater percentage of patients had three or more primary PI mutations (66 vs. 56%) than in the POWER 1 study77. In both studies, darunavir/ritonavir plus OBR was shown to be significantly more effective than investigator-selected PI(s) plus OBR for both suppression of HIV-1 RNA and increase in CD4 cell count.

In the POWER 1 study, 77% of patients receiving darunavir/ritonavir 600/100 mg 2/d (the dose selected for further development in treatment-experienced patients) achieved at least a 1.0 log10 reduction in viral load relative to baseline, compared with only 25% of control patients (p < 0.001)76. Similarly, significantly more darunavir/ritonavir patients had viral load < 50 copies/ml at week 24 compared with control patients (53 vs. 18%; p < 0.001). Increases in mean CD4 cell count were substantially greater at week 24 versus baseline for darunavir/ritonavir compared with the control group (124 vs. 20 cells/mm3; p < 0.001).

Similar results were observed in the POWER 2 study, which recruited more advanced patients: significantly more patients on darunavir/ritonavir 600/100 mg 2/d achieved at least a 1.0 log10 reduction in viral load relative to baseline compared with control patients (62 vs. 14%; p < 0.001)77. Patients on the recommended dose of darunavir/ritonavir were also more likely to achieve a viral load < 50 copies/ml than control patients (39 vs. 7%; p < 0.001). The mean increase in CD4 cell count at week 24 versus baseline was significantly greater for patients on darunavir/ritonavir 600/100 mg compared with control patients (59 vs. 12 cells/mm3; p < 0.01).

At week 24, the overall mean changes versus baseline in log10 viral load (NC = F) for the darunavir/ritonavir 600/100 mg 2/d treatment groups of the POWER 1 and 2 studies were −2.03 and −1.71 copies/ml, respectively76,77. In the control groups, the mean changes versus baseline in log10 viral load were −0.63 and −0.29 copies/ml, respectively76,77. Importantly, the magnitude of the differences in change in viral load between the darunavir/ritonavir 600/100 mg 2/d groups and the control groups of the POWER 1 and 2 studies were comparable: a difference of 1.35 and 1.37 copies/ml, respectively76,77.

Subgroup analyses demonstrated that the inclusion of a greater number of active ARV (including NRTI and enfuvirtide) in the OBR was associated with better virologic outcomes in all treatment groups. In the POWER 1 study, 63% of patients receiving darunavir/ritonavir 600/100 mg 2/d and using enfuvirtide for the first time achieved suppression < 50 copies/ml at week 24 compared to 56% of patients who did not receive enfuvirtide (for control: 22 and 19%, respectively)76. In the POWER 2 study, this was 64 and 30% of patients, respectively (for control: 7 and 4%, respectively)77. This apparent difference was likely related to the number of other viable agents in their OBR. On the recommended dose, the population evaluated in the POWER 1 study had a greater proportion of patients with one or more susceptible NRTI than POWER 2 (77 vs. 62%)76,77. Taken together, these findings underscore the value of using at least two potent ARV agents in heavily treatment-experienced patients. Similar results were obtained with a comparable patient population receiving the darunavir/ritonavir 600/100 mg 2/d dose, in a nonrandomized integrated analysis of two trials (POWER 3 [TMC114-C215 and C208])78.

The pooled POWER 1 and 2 48-week analysis showed darunavir/ritonavir provided durable efficacy in this highly treatment-experienced population79. More recently, treatment with darunavir/ritonavir 600/100 mg 2/d was shown to be statistically non-inferior and superior to lopinavir/ritonavir 400/100 mg 2/d for the endpoint of viral load < 400 copies/ml in early treatment-experienced patients at 48 weeks in the phase III TITAN trial80. Treatment with darunavir/ritonavir 800/100 mg 1/d in treatment-naive patients was also shown to be non-inferior to lopinavir/ritonavir 800/200 mg (either 1/d or 400/100 mg 2/d) for the endpoint of viral load < 50 copies/ml in the phase III ARTEMIS trial at 48 weeks, and was more effective in patients with baseline HIV-1 RNA above 100,000 copies/ml81.

In terms of safety, darunavir showed no cytotoxicity at concentrations of up to 100 µM in in vitro studies51. In patients, darunavir/ ritonavir has been shown to be well tolerated in a phase IIa clinical study and the phase IIb POWER 1 and POWER 2 controlled studies75–77. In a combined analysis of all darunavir/ritonavir dose groups from POWER 1 and POWER 2, the most common adverse events (AE) (occurring in ≥10% of patients, regardless of severity and causality) were similar in darunavir/ritonavir-treated patients and in the control arms; in decreasing order of incidence, these were: diarrhea, headache, nausea, fatigue, nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infection, insomnia, cough, herpes simplex, and pyrexia82. The combined safety analysis revealed that there were more discontinuations in the control group (81% total: 67% for virologic failure, 5% for AEs) than in the darunavir/ritonavir groups (25% total: 12% for virologic failure, 8% for AEs) resulting in a shorter treatment duration for control patients. Finally, the safety results of the POWER 1 and POWER 2 studies showed no apparent relationship between darunavir dose and AE incidence, and no overall difference compared to PIs used in the control groups. The safety results of POWER 3 were similar to those of POWER 1 and POWER 278. The pooled 48-week analysis of POWER 1 and 2 safety and tolerability results79, along with the more recent 48-week data from the two phase III TITAN80 and ARTEMIS81 trials, confirmed the favourable tolerability of darunavir/ritonavir treatment.

The similarity between the POWER trials and the phase III RESIST trials (which evaluated tipranavir/r), in terms of study design, inclusion criteria, selection of control treatment and primary efficacy endpoint, formed the basis of a recent non-randomized comparison between the 24-week results of the studies83. Although darunavir/r and tipranavir/r showed statistically significant benefits over the control treatments in the respective trials, the size of the treatment benefit over control PIs was found to be greater for darunavir/r than tipranavir/r in treatment-experienced patients83. As certain differences exist in baseline characteristics in the two trials, including enfuvirtide use, hepatitis co-infection and advanced HIV infection, such a comparison may not allow for robust conclusions84,85; however, in the absence of randomized comparative trials in treatment-experienced patients, this remains one of the only ways to compare antiviral efficacy83. Both of these most recently approved PIs are considered to be effective in treatment-experienced patients, do not generally show signs of cross-resistance, and can be selected individually on the basis of their resistance profiles85.

Darunavir resistance in the clinic

The most predictive factor for virologic outcome in the POWER 1, 2, and 3 studies was the fold change in EC50 value (FC) for darunavir at baseline. The determinants of increased FC for darunavir were researched by analyzing the influence of both the number and the type of protease mutations on the virologic response at week 24, as well as the mutations that emerged upon virologic failure while on darunavir treatment.

Mutations present at study baseline that were associated with a diminished virologic response to darunavir/ritonavir were V11I, V32I, L33F, I47V, I50V, I54L/M, G73S, L76V, I84V, and L89V. Isolates from patients harboring these mutations tended to have a higher number of PI resistance-associated mutations, as compared with patients who did not harbor these mutations at baseline. Even in the presence of these mutations, however, virologic response in the darunavir/ritonavir arm was higher than for the control arm.

Mutations that developed on-study in ≥ 10% of patients who failed virologically were V32I, L33F, I47V, I54L, and L89V. However, when introduced in a wild-type genetic background by site-directed mutagenesis, mutations V32I, L33F, I47V, or I54L (alone or in combination with one or two other PI resistance-associated mutations) did not cause decreased susceptibility to darunavir (mutation L89V is currently being studied). Interestingly, darunavir makes contacts outside of the substrate envelope at V32, I47, I50 and I84 (Figure 5) making several of these sites of mutation consistent with the substrate envelope theory. Finally, isolates from patients experiencing virologic failure by rebound showed an 8.14-fold median FC increase for darunavir at endpoint compared with baseline. In the same group of patients, however, no such FC increase (median increase of 0.82) was found for tipranavir, suggesting limited cross-resistance between these two PIs. However, this is based on a small number of observations. The FC increase could not be studied for the other PIs, since the baseline isolates were already resistant to these PIs.

Thus, mutations developing upon virologic failure in this population of highly treatment-experienced patients with extensive PI-resistance conferred resistance to darunavir only in the presence of a high number of PI resistance-associated mutations86.

Conclusions

As resistance continues to be a problem with the currently available ARV, there is a significant need for new agents. In the case of PIs, these must have a higher threshold to the development of resistance. This should help limit the development of cross-resistance. The binding characteristics between a PI and the active site of the HIV-1 protease have been shown to be important factors in the development of resistance and cross-resistance. In particular, how PIs fit within the substrate envelope (or substrate consensus volume) seems to be crucial, since primary drug-resistant mutations frequently occur at positions in the protease that are contacted by PI atoms that protrude beyond it. In addition, these specific residues correspond to those where most MDR mutations occur. Insight into the structure, thermodynamics and dynamics of the active site should enable the design of new PIs that mostly fit within the substrate envelope and thus reduce the potential for the development of drug resistance.

Darunavir is a novel PI with improved potency and binding characteristics compared with most currently available PIs. Important distinguishing features include high binding affinity for the protease binding site, the presence of hydrogen bonds with the backbone at the active site cleft, and fitting primarily within the substrate envelope or substrate consensus volume. Darunavir/ritonavir has demonstrated potent in vitro activity against wild-type and PI-resistant viruses and proves difficult to select for resistance in vitro. In clinical studies, darunavir/ritonavir has demonstrated highly potent viral suppression, including highly significant decreases in HIV viral load in both treatment-naive and treatment-experienced patients with documented PI resistance, favorable tolerability, and the potential for both twice-daily and once-daily dosing. Due to its high binding affinity for and the closeness and flexibility of fit within the protease, darunavir has a higher genetic barrier to the development of resistance and improved clinical efficacy against MDR HIV compared with most current PIs, making it a valuable option for the treatment of HIV-infected patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Kevin De-Voy (Professional Medical Writer) and Julia Woodman (Scientific Director), Gardiner-Caldwell Communications, for their assistance in drafting the manuscript. Financial assistance to support this service was provided by Tibotec. Celia Schiffer has received research funding from Tibotec and National Institutes of Health (R01-GM64347 and P01-GM66524).

References

- 1.Harrigan P, Larder B. Extent of cross-resistance between agents used to treat HIV-1 infection in clinically derived isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:909–912. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.3.909-912.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leigh-Brown A, Frost S, Mathews W, et al. Transmission fitness of drug-resistant HIV and the prevalence of resistance in the antiretroviral-treated population. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:683–686. doi: 10.1086/367989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richman D, Morton S, Wrin T, et al. The prevalence of antiretroviral drug resistance in the United States. AIDS. 2004;18:1393–1401. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000131310.52526.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yerly S, Jost S, Telenti A, et al. Infrequent transmission of HIV-1 drug-resistant variants. Antivir Ther. 2004;9:375–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller V. International perspectives on antiretroviral resistance. Resistance to protease inhibitors. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;26 Suppl 1:S34–S50. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200103011-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grant R, Hecht F, Warmerdam M, et al. Time trends in primary HIV-1 drug resistance among recently infected persons. JAMA. 2002;288:181–188. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grossman Z, Lorber M, Maayan S, et al. Drug-resistant HIV infection among drug-naive patients in Israel. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:294–302. doi: 10.1086/426592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Little S, Holte S, Routy J, et al. Antiretroviral-drug resistance among patients recently infected with HIV. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:385–394. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wensing A, Van de Vijver D, Asjo B, et al. Analysis from more than 1600 newly diagnosed patients with HIV from 17 European countries shows that 10% of the patients carry primary drug resistance:the CATCH-Study. 2nd IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis and Treatment; 13–17 July, 2003; Paris, France. [abstract LB01]. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greub G, Cozzi-Lepri A, Ledergerber B, et al. Intermittent and sustained low-level HIV viral rebound in patients receiving potent antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2002;16:1967–1969. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200209270-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karlsson A, Younger S, Martin J, et al. Immunologic and virologic evolution during periods of intermittent and persistent low-level viremia. AIDS. 2004;18:981–989. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200404300-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sklar P, Ward D, Baker R, et al. Prevalence and clinical correlates of HIV viremia (‘blips’) in patients with previous suppression below the limits of quantification. AIDS. 2002;16:2035–2041. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200210180-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kohl N, Emini E, Schleif W, et al. Active HIV protease is required for viral infectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:4686–4690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.13.4686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tomasselli A, Heinrikson R. Targeting the HIV-protease in AIDS therapy: a current clinical perspective. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1477:189–214. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(99)00273-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.King N, Prabu-Jeyabalan M, Nalivaika E, Wigerinck P, de Béthune M, Schiffer C. Structural and thermodynamic basis for the binding of TMC114, a next-generation HIV-1 protease inhibitor. J Virol. 2004;78:12012–12021. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.21.12012-12021.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Surleraux D, Tahri A, Verschueren W, et al. Discovery and selection of TMC114, a next generation HIV-1 protease inhibitor. J Med Chem. 2005;48:1813–1822. doi: 10.1021/jm049560p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Surleraux D, de Kock H, Verschueren W, et al. Design of HIV-1 protease inhibitors active on multidrug-resistant virus. J Med Chem. 2005;48:1965–1973. doi: 10.1021/jm049454n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pettit S, Michael S, Swanstrom R. The specificity of the HIV-1 protease. Perspect Drug Discov Design. 1993;1:69–83. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peng C, Ho B, Chang T, Chang N. Role of HIV-1-specific protease in core protein maturation and viral infectivity. J Virol. 1989;63:2550–2556. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.6.2550-2556.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turner B, Summers M. Structural biology of HIV. J Mol Biol. 1999;285:1–32. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wlodawer A, Gustchina A. Structural and biochemical studies of retroviral proteases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1477:16–34. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(99)00267-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wlodawer A, Erickson J. Structure-based inhibitors of HIV-1 protease. Annu Rev Biochem. 1993;62:543–585. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.002551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rose R, Craik C, Stroud R. Domain flexibility in retroviral proteases: structural implications for drug-resistant mutations. Biochemistry. 1998;37:2607–2621. doi: 10.1021/bi9716074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scott W, Schiffer C. Curling of flap tips in HIV-1 protease as a mechanism for substrate entry and tolerance of drug resistance. Structure. 2000;8:1259–1265. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00537-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perryman A, Lin J, McCammon J. HIV-1 protease molecular dynamics of a wild-type and of the V82F/I84V mutant: possible contributions to drug resistance and a potential new target site for drugs. Protein Sci. 2004;13:1108–1123. doi: 10.1110/ps.03468904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu F, Boross P, Wang Y, et al. Kinetic, stability, and structural changes in high-resolution crystal structures of HIV-1 protease with drug-resistant mutations L24I, I50V, and G73S. J Mol Biol. 2005;354:789–800. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tie Y, Boross P, Wang Y, et al. Molecular basis for substrate recognition and drug resistance from 1.1 to 1.6 angstroms resolution crystal structures of HIV-1 protease mutants with substrate analogs. Febs J. 2005;272:5265–5277. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mahalingam B, Louis J, Hung J, Harrison R, Weber I. Structural implications of drug-resistant mutants of HIV-1 protease: high-resolution crystal structures of the mutant protease/substrate analog complexes. Proteins. 2001;43:455–464. doi: 10.1002/prot.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mahalingam B, Boross P, Wang Y, et al. Combining mutations in HIV-1 protease to understand mechanisms of resistance. Proteins. 2002;48:107–116. doi: 10.1002/prot.10140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prabu-Jeyabalan M, Nalivaika E, Schiffer C. How does a symmetric dimer recognize an asymmetric substrate? A substrate complex of HIV-1 protease. J Mol Biol. 2000;301:1207–1220. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prabu-Jeyabalan M, Nalivaika E, Schiffer C. Substrate shape determines specificity of recognition for HIV-1 protease: analysis of crystal structures of six substrate complexes. Structure. 2002;10:369–381. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00720-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prabu-Jeyabalan M, Nalivaika E, King N, Schiffer C. Viability of a drug-resistant HIV-1 protease variant: structural insights for better antiviral therapy. J Virol. 2003;77:1306–1315. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.2.1306-1315.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prabu-Jeyabalan M, Nalivaika E, King N, Schiffer C. Structural basis for coevolution of a HIV-1 nucleocapsid-p1 cleavage site with a V82A drug-resistant mutation in viral protease. J Virol. 2004;78:12446–12454. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.22.12446-12454.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.King N, Prabu-Jeyabalan M, Nalivaika E, Schiffer C. Combating susceptibility to drug resistance: lessons from HIV-1 protease. Chem Biol. 2004;11:1333–1338. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim E, Baker C, Dwyer M, et al. Crystal structure of HIV-1 protease in complex with VX-478, a potent and orally bioavailable inhibitor of the enzyme. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:1181–1182. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen Z, Li Y, Chen E, et al. Crystal structure at 1.9-A resolution of HIV II protease complexed with L-735,524, an orally bioavailable inhibitor of the HIV proteases. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:26344–26348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krohn A, Redshaw S, Ritchie J, Graves B, Hatada M. Novel binding mode of highly potent HIV-proteinase inhibitors incorporating the (R)-hydroxyethylamine isostere. J Med Chem. 1991;34:3340–3342. doi: 10.1021/jm00115a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kempf D, Marsh K, Denissen J, et al. ABT-538 is a potent inhibitor of HIV protease and has high oral bioavailability in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2484–2488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaldor S, Kalish V, Davies J, et al. Viracept (nelfinavir mesylate, AG1343): a potent, orally bioavailable inhibitor of HIV-1 protease. J Med Chem. 1997;40:3979–3985. doi: 10.1021/jm9704098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stoll V, Qin W, Stewart K, et al. X-ray crystallographic structure of ABT-378 (lopinavir) bound to HIV-1 protease. Bioorg Med Chem. 2002;10:2803–2806. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(02)00051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thaisrivongs S, Strohbach J. Structure-based discovery of tipranavir disodium (PNU-140690E): a potent, orally bioavailable, nonpeptidic HIV protease inhibitor. Biopolymers. 1999;51:51–58. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(1999)51:1<51::AID-BIP6>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yanchunas J, Jr, Langley D, Tao L, et al. Molecular basis for increased susceptibility of isolates with atazanavir resistance-conferring substitution I50L to other protease inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:3825–3832. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.9.3825-3832.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Todd M, Luque I, Velazquez-Campoy A, Freire E. Thermodynamic basis of resistance to HIV-1 protease inhibition: calorimetric analysis of the V82F/I84V active site resistant mutant. Biochemistry. 2000;39:11876–11883. doi: 10.1021/bi001013s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Velazquez-Campoy A, Luque I, Todd M, Milutinovich M, Kiso Y, Freire E. Thermodynamic dissection of the binding energetics of KNI-272, a potent HIV-1 protease inhibitor. Protein Sci. 2000;9:1801–1809. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.9.1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ohtaka H, Muzammil S, Schon A, Velazquez-Campoy A, Vega S, Freire E. Thermodynamic rules for the design of high affinity HIV-1 protease inhibitors with adaptability to mutations and high selectivity towards unwanted targets. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:1787–1799. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ohtaka H, Freire E. Adaptive inhibitors of the HIV-1 protease. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2005;88:193–208. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.King N, Melnick L, Prabu-Jeyabalan M, et al. Lack of synergy for inhibitors targeting a multi-drug-resistant HIV-1 protease. Protein Sci. 2002;11:418–429. doi: 10.1110/ps.25502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koh Y, Nakata H, Maeda K, et al. Novel bis-tetrahydrofuranylurethane-containing nonpeptidic protease inhibitor UIC-94017 (TMC114) with potent activity against multi-PI-resistant HIV in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:3123–3129. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.10.3123-3129.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tie Y, Boross P, Wang Y, et al. High resolution crystal structures of HIV-1 protease with a potent non-peptide inhibitor (UIC-94017) active against multi-drug-resistant clinical strains. J Mol Biol. 2004;338:341–352. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kovalevsky A, Tie Y, Liu F, et al. Effectiveness of nonpeptide clinical inhibitor TMC-114 on HIV-1 protease with highly drug resistant mutations D30N, I50V, and L90M. J Med Chem. 2006;49:1379–1387. doi: 10.1021/jm050943c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.De Meyer S, Azjin H, Surleraux D, et al. TMC114, a novel HIV-1 protease inhibitor active against protease inhibitor-resistant viruses, including a broad range of clinical isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:2314–2321. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.6.2314-2321.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dierynck I, Keuleers I, De Wit M, et al. Kinetic characterization of the potent activity of TMC114 on wild-type HIV-1 protease. Abstracts of 14th International HIV Drug Resistance Workshop; 7–11 June, 2005; Québec City, Canada. [poster 64]. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chong K-T, Pagano PJ. In vitro combination of PNU-140690, a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease inhibitor, with ritonavir against ritonavir-sensitive and -resistant clinical isolates. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2367–2373. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.11.2367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Muzammil S, Armstrong AA, Kang LW, et al. Unique thermodynamic response of tipranavir to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease drug resistance mutations. J Virol. 2007;81:5144–5154. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02706-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clavel F, Hance A. HIV drug resistance. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1023–1035. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra025195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu T, Schiffer C, Gonzales M, et al. Mutation patterns and structural correlates in HIV-1 protease following different protease inhibitor treatments. J Virol. 2003;77:4836–4847. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.8.4836-4847.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rhee S, Fessel W, Zolopa A, et al. HIV-1 Protease and reverse transcriptase mutations: correlations with antiretroviral therapy in subtype B isolates and implications for drug-resistance surveillance. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:456–465. doi: 10.1086/431601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hoffman N, Schiffer C, Swanstrom R. Covariation of amino acid positions in HIV-1 protease. Virology. 2003;314:536–548. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00484-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.De Mendoza C, Soriano V. Resistance to HIV protease inhibitors: mechanisms and clinical consequences. Curr Drug Metab. 2004;5:321–328. doi: 10.2174/1389200043335522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Watkins T, Resch W, Irlbeck D, Swanstrom R. Selection of high level resistance to HIV-1 protease inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:759–769. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.2.759-769.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schock H, Garsky V, Kuo L. Mutational anatomy of an HIV-1 protease variant conferring cross-resistance to protease inhibitors in clinical trials. Compensatory modulations of binding and activity. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:31957–31963. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.31957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hertogs K, Bloor S, Kemp S, et al. Phenotypic and genotypic analysis of clinical HIV-1 isolates reveals extensive protease inhibitor crossresistance: a survey of over 6000 samples. AIDS. 2000;14:1203–1210. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006160-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kemper C, Witt M, Keiser P, et al. Sequencing of protease inhibitor therapy: insights from an analysis of HIV phenotypic resistance in patients failing protease inhibitors. AIDS. 2001;15:609–615. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200103300-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shafer R, Hsu P, Patick A, Craig C, Brendel V. Identification of biased amino acid substitution patterns in HIV-1 isolates from patients treated with protease inhibitors. J Virol. 1999;73:6197–6202. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.6197-6202.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shafer R, Stevenson D, Chan B. HIV reverse transcriptase and protease sequence database. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:348–352. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mitsuya Y, Liu TF, Rhee SY, et al. Prevalence of darunavir resistance-associated mutations: patterns of occurrence and association with past treatment. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:1177–1179. doi: 10.1086/521624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Poveda E, de Mendoza C, Martin-Carbonero L, et al. Prevalence of darunavir resistance mutations in HIV-1-infected patients failing other protease inhibitors. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60:885–888. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Picchio G, Vangeneugden T, Van Baelen B, et al. Prior utilization/resistance to amprenavir at screening has minimal impact on the 48-week response to darunavir/r in the POWER 1, 2 and 3 studies. 14th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; 25–28 February, 2007; Los Angeles, CA, USA. [abstract 609]. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kempf D, Isaacson J, King M, et al. Identification of genotypic changes in HIV protease that correlate with reduced susceptibility to the protease inhibitor lopinavir among viral isolates from protease inhibitor-experienced patients. J Virol. 2001;75:7462–7469. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.16.7462-7469.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schinazi R, Larder B, Mellors W. Mutations in retroviral genes associated with drug resistance. Int Antiviral News. 1997;5:129–142. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ohtaka H, Velazquez-Campoy A, Xie D, Freire E. Overcoming drug resistance in HIV-1 chemotherapy: the binding thermodynamics of amprenavir and TMC-126 to wild-type and drug-resistant mutants of the HIV-1 protease. Protein Sci. 2002;11:1908–1916. doi: 10.1110/ps.0206402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mo H, Lu L, Dekhtyar T, et al. Characterization of resistant HIV variants generated by in vitro passage with lopinavir/ritonavir. Antiviral Res. 2003;59:173–180. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(03)00107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yoshimura K, Kato R, Kavlick M, et al. A potent HIV-1 protease inhibitor, UIC-94003 (TMC-126), and selection of a novel (A28S) mutation in the protease active site. J Virol. 2002;76:1349–1358. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.3.1349-1358.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.De Meyer S, Azijn H, Fransen E, et al. The pathway leading to TMC114 resistance is different for TMC114 compared with other protease inhibitors. XV International HIV Drug Resistance Workshop; 13–17 June, 2006; Sitges, Spain. [abstract 19]. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Arastéh K, Clumeck N, Pozniak A, et al. TMC114/ritonavir substitution for protease inhibitor(s) in a non-suppressive antiretroviral regimen: a 14-day proof-of-principle trial. AIDS. 2005;19:943–947. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000171408.38490.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Katlama C, Esposito R, Gatell J, et al. Efficacy and safety of TMC114/ritonavir in treatment-experienced HIV patients: 24-week results of POWER 1. AIDS. 2007;21:395–402. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328013d9d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Haubrich R, Berger D, Chiliade P, et al. Week 24 efficacy and safety of TMC114/ritonavir in treatment-experienced HIV patients. AIDS. 2007;21:F11–F18. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3280b07b47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Molina J-M, Cohen C, Katlama C, et al. TMC114/r in treatmentexperienced HIV patients in POWER 3: 24-week efficacy and safety analysis. 16th IAC; 13–18 August, 2006; Toronto, Canada. [abstract TUPE0060]. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Clotet B, Bellos N, Molina J-M, et al. Efficacy and safety of darunavir-ritonavir at week 48 in treatment-experienced patients with HIV-1 infection in POWER 1 and 2: a pooled subgroup analysis of data from two randomised trials. Lancet. 2007;369:1169–1178. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60497-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Valdez-Madruga J, Berger D, McMurchie M, et al. Efficacy and safety of darunavir-ritonavir compared with that of lopinavir-ritonavir at 48 weeks in treatment-experienced, HIV-infected patients in TITAN: a randomised controlled phase III trial. Lancet. 2007;370:49–58. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.DeJesus E, Ortiz R, Khanlou H, et al. Efficacy and safety of darunavir/ritonavir versus lopinavir/ritonavir in ARV treatment-naive patients at week 48: ARTEMIS. 47th Annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy; 17–20 September, 2007; Chicago, IL, USA. [abstract H-718b]. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tibotec BVBA. Belgium: Mechelen; Data on file. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hill A, Moyle G. Relative antiviral efficacy of ritonavir-boosted darunavir and ritonavir-boosted tipranavir vs. control protease inhibitor in the POWER and RESIST trials. HIV Med. 2007;8:259–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2007.00465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Llibre JM, Perez-Alvarez N, Hill A, Moyle G. Relative antiviral efficacy of ritonavir-boosted darunavir and ritonavir-boosted tipranavir vs. control protease inhibitor in the POWER and RESIST trials. HIV Med. 2007;8:259–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2007.00465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Methodological accuracy in cross-trial comparisons of antiretroviral regimens in multitreated patients. HIV Med. 2007;8:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2007.00503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hall D. Relative antiviral efficacy should not be inferred from cross-trial comparisons. HIV Med. 2007;8:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2007.00503_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.De Meyer S, Hill A, De Baere I, et al. Effect of baseline susceptibility and on-treatment mutations on TMC114 and control PI efficacy: preliminary analysis of data from PI-experienced patients from POWER 1 and POWER 2. 13th CROI; 5–9 February, 2006; Denver, Colorado, USA. [abstract 157]. [Google Scholar]