Abstract

Background

Inhibition of voltage-gated Na+ channels (Nav) is implicated in the synaptic actions of volatile anesthetics. We studied the effects of the major halogenated inhaled anesthetics (halothane, isoflurane, sevoflurane, enflurane and desflurane) on Nav1.4, a well characterized pharmacological model for Nav effects.

Methods

Na+ currents (INa) from rat Nav1.4 α-subunits heterologously expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells were analyzed by whole cell voltage-clamp electrophysiological recording.

Results

Halogenated inhaled anesthetics reversibly inhibited Nav1.4 in a concentration- and voltage-dependent manner at clinical concentrations. At equi-anesthetic concentrations, peak INa was inhibited with a rank order of desflurane > halothane ≈ enflurane > isoflurane ≈ sevoflurane from a physiological holding potential (−80 mV). This suggests that the contribution of Na+ channel block to anesthesia might vary in an agent-specific manner. From a hyperpolarized holding potential that minimizes inactivation (−120 mV), peak INa was inhibited with a rank order of potency for tonic inhibition of peak INa of halothane > isoflurane ≈ sevoflurane > enflurane > desflurane. Desflurane produced the largest negative shift in voltage-dependence of fast inactivation consistent with its more prominent voltage-dependent effects. A comparison between isoflurane and halothane showed that halothane produced greater facilitation of current decay, slowing of recovery from fast inactivation, and use-dependent block than isoflurane.

Conclusions

Five halogenated inhaled anesthetics all inhibit a voltage-gated Na+ channel by voltage- and use-dependent mechanisms. Agent-specific differences in efficacy for Na+ channel inhibition due to differential state-dependent mechanisms creates pharmacologic diversity that could underlie subtle differences in anesthetic and nonanesthetic actions.

Introduction

Both ligand-gated ion channels, including GABAA (γ-aminobutyric acid, type A) receptors, glycine receptors, neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, and N-methyl-D-aspartic acid -type glutamate receptors, as well as voltage-gated ion channels, including Ca2+ channels, K+ channels and Na+ channels, represent promising molecular targets for various general anesthetics.1 Depression of presynaptic action potential amplitude involving Na+ channel blockade has been implicated in inhibition of neurotransmitter release by the potent inhaled (volatile) anesthetics.2,3 The voltage-gated Na+ channel (Nav) superfamily consists of 9 distinct genes that encode for the channel-forming α-subunit (Nav1.1–1.9), each with tissue-dependent expression and functions.4 The potent inhaled anesthetics inhibit native neuronal Na+ channels5–7 as well as heterologously expressed mammalian Na+ channel α-subunits.8–11 However, the relative potencies and channel gating effects of various inhaled anesthetics have not been compared in detail. Although Na+ channel blockade is of enormous therapeutic importance for cardiac dysrhythmias, acute and chronic pain states, seizure disorders and possibly general anesthesia, systemic administration of Na+ channel blockers is associated with severe cardiac and central nervous system side-effects.4 Effects of anesthetics on central nervous system and peripheral Nav isoforms are therefore likely to be involved in their anesthetic and some of their agent-specific non-anesthetic effects.

We characterized the effects of five potent inhaled anesthetics on the functionand gating of rat Nav1.4 α-subunits heterologously expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. The skeletal muscle Na+ channel isoform Nav1.4 is expressed at the neuromuscular junction where it regulates muscle excitability.12 Nav1.4 function is inhibited by local anesthetic and antidepressant drugs, and provides a well-characterized model for studies of Na+ channel pharmacology that is amenable to genetic manipulation for detailed structure-function studies.13–17 The halogenated alkane halothane and methylethyl ethers isoflurane, sevoflurane, enflurane and desflurane represent the principal volatile anesthetics employed clinically in the modern era. Detailed kinetic characterization of their Na+ channel blocking effects is important in identifying common and/or distinct features that might contribute to agent-specific pharmacological profiles. We report here that all five anesthetics inhibit Nav1.4 at concentrations in the clinical range in proportion to their potencies for producing anesthesia in vivo, which provides additional support for Na+ channel blockade as a plausible mechanism of inhaled anesthetic action. In addition, agent-specific differences in their relative potencies and involvement of state-dependent mechanisms could contribute to differences in their central and peripheral pharmacodynamic properties.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

Chinese hamster ovary cells stably transfected with rat Nav1.4 α-subunit (a gift from S. Rock Levinson, Ph.D., Professor, Department of Physiology and Biophysics, University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Denver, Colorado) were cultured in 90% (v/v) DMEM medium, 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum, 300 μg/ml G418 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Biosource, Rockville, MD) under 95% air/5% CO2 at 37°C. Cells were plated on glass coverslips in 35-mm plastic dishes (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) 1–3 days prior to electrophysiological recording.

Electrophysiology

Cells attached to coverslips were transferred to a plastic Petri dish (35×10 mm) on the stage of a Nikon ECLIPSE TE300 inverted microscope (Melville, NY). The culture medium was replaced and cells were superfused at 1.5–2 ml/min with extracellular solution containing (in mM): NaCl 140; KCl 4; CaCl2 1.5; MgCl2 1.5; HEPES 10; D-glucose 5; pH 7.30 with NaOH. Studies were conducted at room temperature (24±1°C) using conventional whole cell patch-clamp techniques.18 Patch electrodes (tip diameter <1 μm) were made from borosilicate glass capillaries (Drummond Scientific, Broomall, PA) using a micropipette puller (P-97, Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA) and fire polished (Narishige Microforge, Kyoto, Japan). Electrode tips were coated with SYLGARD (Dow Corning Corporation, Midland, MI) to lower background noise and reduce capacitance; electrode resistance was 2–5 MΩ. The pipet electrode solution contained (in mM): CsF 80; CsCl 40; NaCl 15; HEPES 10; EGTA 10; pH 7.35 with CsOH. Currents were sampled at 10 kHz and filtered at 1–3 kHz using an Axon 200B amplifier, digitized via a Digidata 1321A interface, and analyzed using pClamp 8.2 (Axon/Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Capacitance and 60–85% series resistance were compensated and leak current was subtracted using P/4 or P/5 protocols. Cells were held at −80 mV between recordings. Only cells with Na+ currents of 0.5–3.5 nA were analyzed in order to minimize increasing series resistance and contributions of endogenous Na+ currents (<50 pA) occasionally observed in Chinese hamster ovary cells.19

Anesthetics

Thymol-free halothane was obtained from Halocarbon Laboratories (River Edge, NJ); isoflurane and sevoflurane were from Abbott Laboratories (Abbott Park, IL), enflurane was from Anaquest Inc. (Liberty Corner, NJ), and desflurane was from Baxter Healthcare Corporation (Deerfield, IL). Anesthetics were diluted from saturated aqueous stock solutions made in extracellular solution (14–16 mM halothane, 10–12 mM isoflurane, 4–6 mM sevoflurane, 10–12 mM enflurane, 8–10 mM desflurane) prepared 12–24 h prior to experiments into airtight glass syringes, and applied locally to attached cells at 50–70 μl/min using an ALA-VM8 pressurized perfusion system (ALA Scientific, Westbury, NY) through a 0.15 mm diameter perfusion pipette positioned 30–40 μm away from patched cells. Concentrations of volatile anesthetics were determined by local sampling of the perfusate at the site of the recording pipette tip and analysis by gas chromatography as described. 5

Statistical analysis

IC50 values were calculated by least squares fitting of data to the Hill equation: Y=1/(1+10((logIC50−X)*h)), where Y is the effect, X is measured anesthetic concentration, and h is Hill slope. Activation curves were fitted to a Boltzmann equation of the form G/Gmax=1/(1+e(V1/2a−V)/k), where G/Gmax is normalized fractional conductance, Gmax is maximum conductance, V1/2a is voltage for half-maximal activation, and k is the slope factor. Na+ conductance (GNa) was calculated using the equation: GNa=INa/(Vt−Vr), where INa is peak Na+ current, Vt is test potential and Vr is Na+ reversal potential (ENa=69 mV). Fast inactivation curves were fitted to a Boltzmann equation of the form I/Imax=1/(1+e(V1/2in−V)/k), where I/Imax is normalized current, Imax is maximum current, V1/2in is voltage of half maximal inactivation, and k is slope factor. INa current decay was analyzed by fitting the decay phase of the current trace between 90% and 10% of maximal INa to the mono-exponential equation INa=A·exp(−t/τin)+C, where A is maximal INa amplitude, C is plateau INa, t is time, and τin is time constant of current decay. Channel recovery from fast inactivation was fitted to the mono-exponential function Y=A*(1−exp(−τr*X)), where Y is fractional current recovery constrained to 1.0 at infinity time, A is normalized control amplitude, X is recovery time, and τr is time constant of recovery, and the goodness of fit compared to that of a bi-exponential function. The effects of anesthetics were compared to control using sum-of-squares F-test between curve fits of mean data. The time course of use-dependent decay of normalized INa was analyzed by fitting to the mono-exponential equation INa=exp(− τuse·n)+C, where n is pulse number, C is plateau INa, and τuse is time constant of use-dependent decay. Data were analyzed using pClamp 8.2 (Axon/Molecular Devices), Prism 4.0 (Graph-Pad Software Inc., San Diego, CA) and SigmaPlot 6.0 (SPSS Science Software Inc., Chicago, IL). Curve fits were compared by sum-of-squares F-test. Statistical significance was assessed by analysis of variance with Newman-Keuls post hoc test or paired or unpaired t-tests, as appropriate; p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Inhibition of peak INa

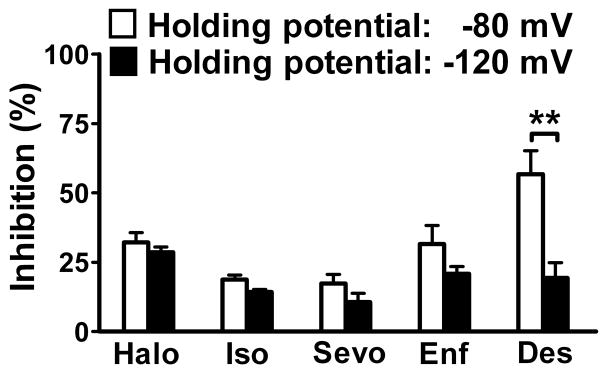

Average peak Na+ current (INa) in Chinese hamster ovary cells transfected with the Nav1.4 α-subunit was −3.0±0.2 nA (n=11) from a holding potential of −120 mV. Peak INa was rapidly (onset<1.5 min) and reversibly inhibited by all five inhaled anesthetics tested (fig. 1), and by the specific Na+ channel blocker tetrodotoxin (data not shown). Inhibition was greater from the more physiological holding potential of −80 mV than from the hyperpolarized potential of −120 mV (fig. 2), indicative of significant voltage-dependent inhibition. At aqueous concentrations equivalent to ~1 Minimum alveolar concentration (MAC) for rat (0.35 mM for halothane and isoflurane, 0.46 mM for sevoflurane, 0.75 mM for enflurane, and 0.80 mM for desflurane),20 desflurane showed the greatest inhibition of peak INa from a holding potential of −80 mV. The rank order of inhibition was desflurane (57±6.2% @ 0.83±0.06 mM, n=4) > halothane (32±3.5% @ 0.42±0.05 mM, n=6) enflurane (32±6.7% @ 0.82±0.06 mM, n=5) > isoflurane (19±1.9% @ 0.46±0.04 mM, n=4) sevoflurane (17±3.3% @ 0.44±0.04 mM, n=4; mean±SEM). The degree of voltage-dependent inhibition (difference between efficacy at −80 mV vs. −120 mV) varied between anesthetics, and was greatest for desflurane and least for halothane (fig. 2).

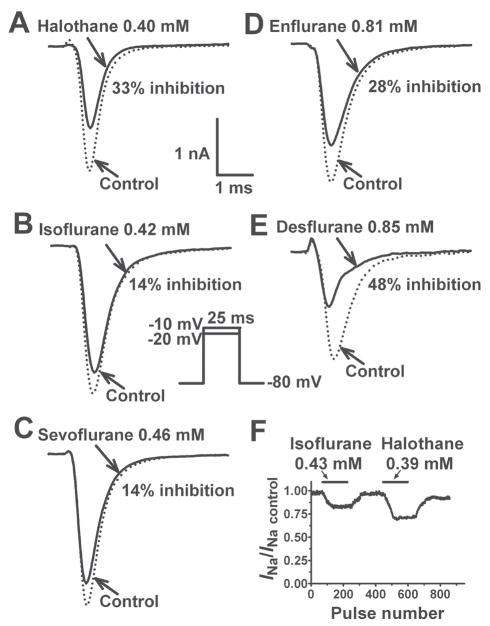

Fig. 1.

Inhibition of Nav1.4 by equipotent concentrations of various inhaled anesthetics. Na+ currents (INa) were recorded from a holding potential of −80 mV by 25 ms test steps to Vmax (−10 or −20 mV) as shown in the inset. The effects of halothane (A, 0.40 mM; 1.1 MAC), isoflurane (B, 0.42 mM; 1.2 MAC) and sevoflurane (C, 0.46 mM; 1.0 MAC), enflurane (D, 0.81 mM; 1.1 MAC) and desflurane E, (0.85 mM; 1.1 MAC) at ~1 MAC are shown in these representative traces (summary data are given in the Results). The time-course of INa inhibition expressed as fractional INa (INa/INa control) during application of isoflurane (0.43 mM, 1.2 MAC) or halothane (0.39 mM, 1.1 MAC) for 1.5 min is shown in F. INa was repetitively activated from a holding potential of −120 mV by 25 ms test pulses to −10 mV at 0.5 sec intervals.

Fig. 2.

Voltage-dependent inhibition of Nav1.4 by inhaled anesthetics. Equipotent concentrations (~1 MAC) of inhaled anesthetics differentially inhibited INa from a holding potential of −80 mV (open bars) or −120 mV (filled bars). The measured concentrations of halothane (Halo), isoflurane (Iso), sevoflurane (Sevo), enflurane (Enf), and desflurane (Des) were 0.42±0.05 mM (1.2 MAC), 0.46±0.03 mM (1.3 MAC), 0.44± 0.03 mM (1.0 MAC), 0.82±0.04 mM (1.1 MAC), and 0.83±0.03 mM (1.0 MAC), respectively, from a holding potential of −80 mV; and were 0.38±0.05 mM (1.1 MAC), 0.41±0.04 mM (1.1 MAC), 0.45±0.05 mM (1.0 MAC), 0.80±0.05 mM (1.1 MAC), and 0.83±0.04 mM (1.0 MAC), respectively, from a holding potential of −120 mV. Data are expressed as mean±SEM (n=4–12). ** P < 0.01 by unpaired t-test.

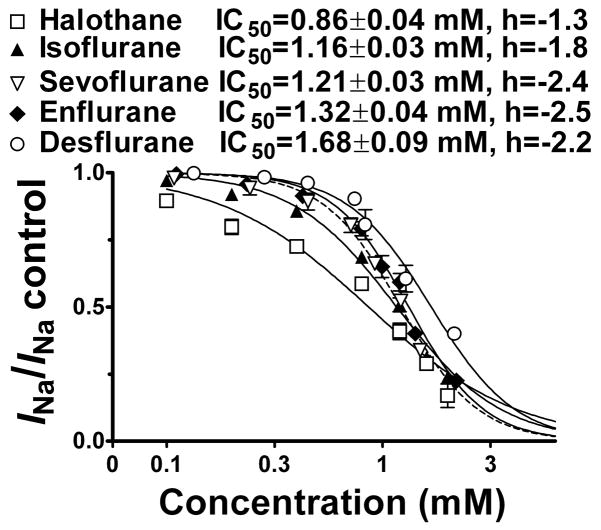

Voltage-gated Na+ channels have at least three distinct conformational states: resting, open, and inactivated.13 The potency of each anesthetic for tonic inhibition was investigated using a holding potential of −120 mV to maintain channels in the resting state allowing assessment of resting channel block with minimal interference from voltage-dependent inactivation. All five anesthetics exhibited concentration-dependent inhibition of peak INa with IC50 values in the millimolar range and Hill slopes of ~2, except for halothane which had a Hill slope of ~1 (fig. 3); this suggests the possibility of two sites of interaction with Nav1.4 for the ethers vs. a single site of interaction for the alkane.

Fig. 3.

Concentration dependence of Nav1.4 inhibition by inhaled anesthetics. Normalized peak INa values from a holding potential of −120 mV were fitted to the Hill equation to yield IC50 values (±SE) and Hill slopes. IC50 values differed from each other by sum-of-squares F-test (P < 0.05). □, Halothane; ▲, Isoflurane; ▽, Sevoflurane; ◆, Enflurane; ○, Desflurane.

Effects on channel gating

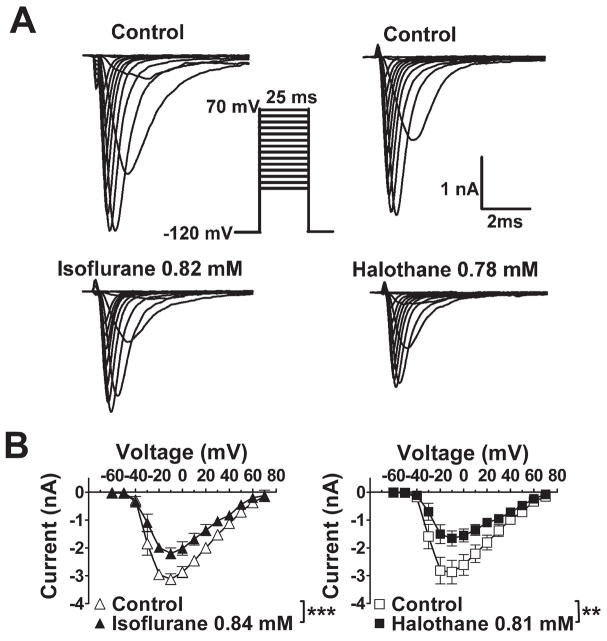

None of the anesthetics tested altered the current-voltage relationship or reversal potential for INa (fig. 4; data not shown). At concentrations equivalent to ~1 MAC, all five anesthetics produced no significant shift in the voltage dependence of activation (fig. 5) with minor effects on slope factors (data not shown). The voltage dependence of fast inactivation was determined for the prototypical anesthetic isoflurane, and for desflurane and halothane which exhibited extremes in voltage sensitivity (fig. 2). Representative current traces, which reflect channel availability at various holding potentials, obtained using a protocol designed to minimize the influence of slow inactivation are shown in figure 6A. Isoflurane, halothane and desflurane strongly enhanced inactivation in a concentration-dependent manner. Desflurane produced a greater negative shift in V1/2in than isoflurane or halothane as seen in curve fits of the mean data (fig. 6B,C). At concentrations of ~1 MAC, isoflurane, halothane and desflurane shifted V1/2in by −7 mV, −9 mV and −13 mV, respectively (fig. 6B). Similar effects were evident when the data were analyzed by calculating the mean values of V1/2in derived from curve fits of the individual data sets (table 1). Slope factors, which reflect the voltage sensitivity of the inactivation gate,21 were not significantly affected by isoflurane and halothane, but were slightly increased by desflurane (table 1). Macroscopic current inactivation was examined by fitting the rate of decay of current elicited by depolarization from −120 mV to Vmax to a mono-exponential equation. Time constants of current decay (τin) were reduced by desflurane > halothane > isoflurane (table 2). The effects of isoflurane and halothane on recovery of INa from fast inactivation were evaluated by a two-pulse protocol with varying time intervals (fig. 7). Both anesthetics slowed recovery from inactivation by increasing the time constant of recovery (τr, ms) derived from mono-exponential fits of the fractional current (fig. 7).

Fig. 4.

Effects of isoflurane and halothane on Nav1.4 current-voltage relationship. A. Isoflurane (left) or halothane (right) at concentrations equivalent to ~2 MAC significantly inhibited INa from a holding potential of −120 mV. B. Voltage of peak INa activation (Vmax) was −10 mV; neither anesthetic affected voltage of peak current activation or reversal potential. Mean concentrations of isoflurane was 0.84±0.08 mM (2.4 MAC) and of halothane was 0.81±0.06 mM (2.3 MAC) (n=5–8). Comparable results were obtained for desflurane, enflurane, and sevoflurane (data not shown). *** P < 0.001, ** P < 0.01 vs. control by paired t-test.

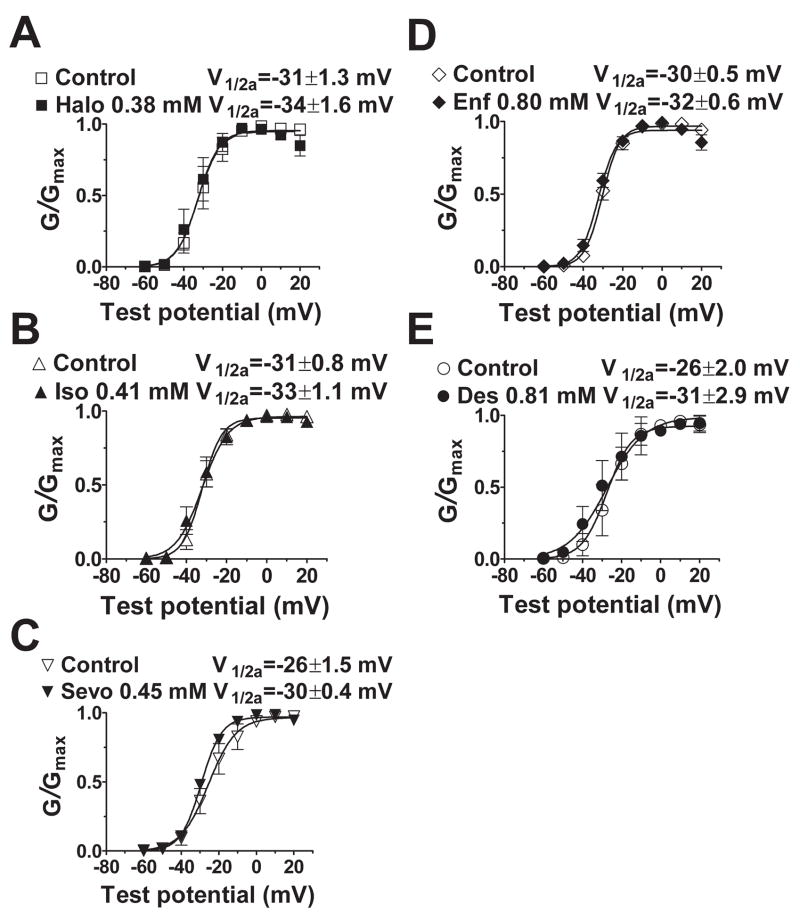

Fig. 5.

Effects of volatile anesthetics on voltage-dependence of Nav1.4 activation. Normalized conductance data (mean±SEM) were fitted to a Boltzmann equation to yield voltage of 50% maximal activation (V1/2a) and slope factor. Holding potential was −120 mV (n=5–12). There were no significant shifts in V1/2a or slope factor (P > 0.05 by t-test). See Fig. 2 legend for abbreviations.

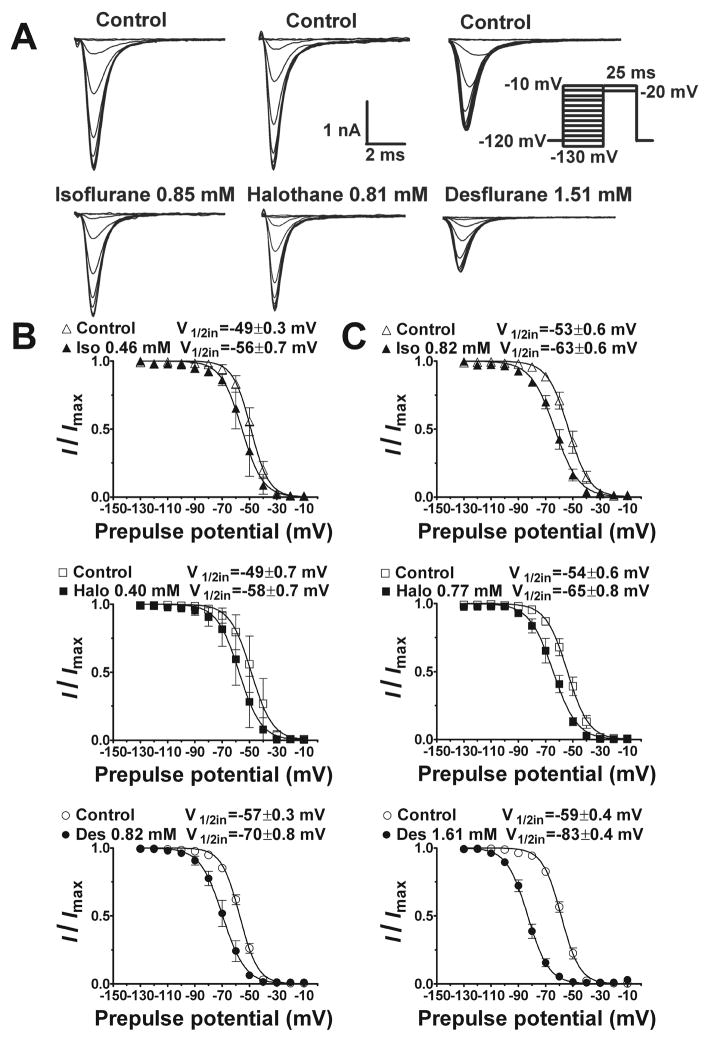

Fig. 6.

Effects of isoflurane, halothane and desflurane on voltage dependence of Nav1.4 fast inactivation. A. Representative traces show inhibition of INa by isoflurane (left), halothane (middle) and desflurane (right) using a fast inactivation protocol (inset) involving a conditioning pulse of 30 ms followed by a test pulse of 25 ms to minimize slow inactivation. Normalized data were fitted to the Boltzmann equation to yield voltage of 50% inactivation (V1/2in) and slope factor for ~1 MAC (B) or ~2 MAC (C). Each anesthetic significantly shifted the V1/2in in the negative direction as determined by sum-of-squares F-test comparison between curve fits of mean data (P < 0.05). Parameters derived from analysis of independent curve fits are presented in Table 1. Anesthetic concentrations were 0.46±0.09 mM and 0.82±0.07 mM for isoflurane; 0.40±0.06 mM and 0.77±0.10 mM for halothane; and 0.82±0.06 mM and 1.61±0.07 mM for desflurane. Data expressed as mean±SEM, n=5–7.

Table 1.

Inhaled Anesthetic Effects on Nav1.4 Inactivation.

| ~1 MAC | V1/2in, mV | k | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | −49.1 ± 1.4 | 6.5 ± 0.2 | 4 |

| Isoflurane (0.46 ± 0.09 mM) | −55.4 ± 2.6 | 6.9 ± 0.1 | 4 |

| Control | −48.8 ± 2.5 | 7.0 ± 0.5 | 7 |

| Halothane (0.40 ± 0.06 mM) | −57.8 ± 2.5‡ | 7.2 ± 0.4 | 7 |

| Control | −57.2 ± 1.1 | 6.6 ± 0.1 | 5 |

| Desflurane (0.82 ± 0.06 mM) | −69.7 ± 3.0†§|| | 7.4 ± 0.3* | 5 |

| ~2 MAC | |||

| Control | −53.2 ± 2.3 | 7.1 ± 0.3 | 5 |

| Isoflurane (0.82 ± 0.07 mM) | −63.3 ± 2.1* | 8.4 ± 0.9 | 5 |

| Control | −54.1 ± 2.2 | 7.3 ± 0.4 | 5 |

| Halothane (0.77 ± 0.10 mM) | −64.9 ± 2.8‡ | 7.9 ± 0.6 | 5 |

| Control | −58.7 ± 1.2 | 6.7 ± 0.1 | 4 |

| Desflurane (1.61 ± 0.07 mM) | −83.2 ± 1.6‡§|| | 7.5 ± 0.1* | 4 |

Data for each experiment were fitted to a standard Boltzmann equation, and V1/2in and slope values for each experiment were averaged and displayed as mean ± SEM.

P < 0.05,

P <0.01,

P < 0.001 vs. respective control by paired t test.

P < 0.05 vs. isoflurane,

P < 0.05 vs. halothane by one-way analysis of variance with Newman-Keuls post hoc test. k = slope factor; MAC = minimum alveolar concentration; V1/2in = voltage of half-maximal inactivation.

Table 2.

Inhaled anesthetic effects on Nav1.4 current decay.

| τin, ms | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Anesthetic | Concentration, mM | n | |

| Isoflurane | 0.54 ± 0.08 | 0.47 ± 0.08* | 0.46 ± 0.05 | 8 |

| 0.52 ± 0.09 | 0.43 ± 0.08* | 0.85 ± 0.04 | 6 | |

| Halothane | 0.51 ± 0.07 | 0.42 ± 0.04* | 0.43 ± 0.03 | 5 |

| 0.55 ± 0.07 | 0.39 ± 0.06† | 0.81 ± 0.04 | 5 | |

| Desflurane | 0.55 ± 0.10 | 0.40 ± 0.05*‡ | 0.80 ± 0.06 | 7 |

| 0.54 ± 0.09 | 0.34 ± 0.08†‡§ | 1.65 ± 0.14 | 5 | |

Values are mean ± SEM.

P < 0.01,

P < 0.001 vs. respective control by unpaired t test.

P < 0.05 vs. isoflurane,

P < 0.05 vs. halothane by one-way analysis of variance with Newman-Keuls post hoc test. τin = time constant of current decay calculated for a prepulse potential of −120 mV.

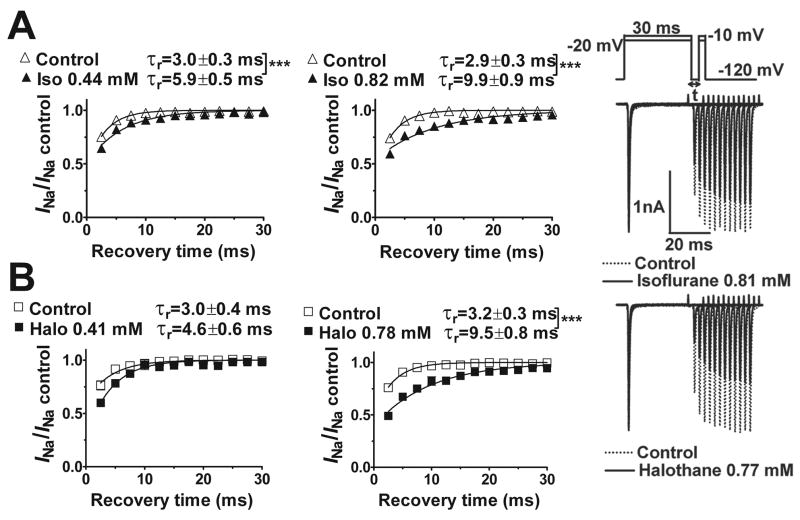

Fig. 7.

Effects of isoflurane and halothane on recovery of Nav1.4 from fast inactivation. The protocol, shown in the upper right inset, involved 12 depolarizing test steps at various recovery times (t) in 2.5 ms intervals. Representative current traces obtained for the effects of isoflurane (~2.3 MAC) and halothane (~2.2 MAC) are shown on the right. The time course of channel recovery from fast inactivation was best fitted by a mono-exponential function in all cases to yield a recovery time constant (τr). The rate of recovery, expressed as current normalized to initial control current, was slowed by isoflurane (A) and halothane (B). The recovery time constant was greater for halothane than for isoflurane at the higher concentrations as determined by sum-of-squares F-test between curve fits of mean data (P < 0.001). Mean isoflurane concentrations were 0.44±0.06 mM and 0.82±0.08 mM; mean halothane concentrations were 0.41±0.07 mM and 0.78±0.10 mM. Data are expressed as mean±SEM, n=5–8. *** P < 0.001 vs. control.

Use-dependent block

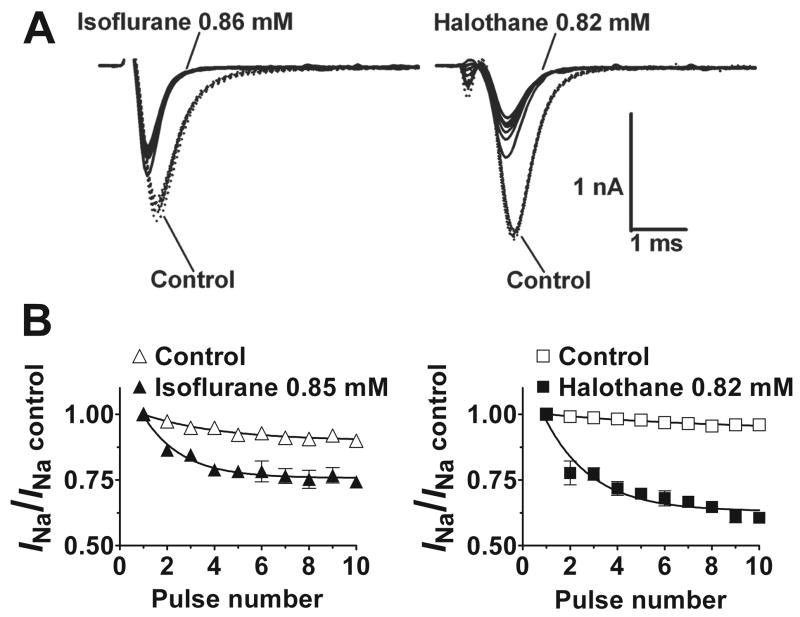

Use-dependent block of Nav1.4 was evident as a reduction in normalized INa relative to the peak of the first pulse evaluated in a series of rapid depolarizing pulses (fig. 8). In the absence of anesthetic, repetitive pulses produced only small reductions in peak INa. Both halothane and isoflurane at ~2 MAC reduced the time constant of use-dependent decay (τuse). Halothane produced a greater reduction in steady-state normalized INa amplitude than isoflurane (P < 0.05 by paired t-test, n=3). These results are consistent with contributions of open channel block and/or enhanced inactivation to inhibition of Nav1.4.

Fig. 8.

Enhanced use-dependent block of Nav1.4 by isoflurane and halothane. A. Representative current traces showing isoflurane (left) and halothane (right; solid lines) enhancement of use-dependent block of INa compared to control (dotted lines) from a holding potential of −120 mV. B. Peak currents were normalized to the current of the first pulse (mean±SEM; n=3), plotted against pulse number, and fitted to a mono-exponential function. Halothane (0.82±0.06 mM) reduced the time constant of use-dependent decay (τuse) from 7.3 to 2.0 pulses, and isoflurane (0.85±0.08 mM) reduced τuse from 3.3±0.02 to 1.6±0.02 pulses (mean, n=3). Halothane produced a significantly greater reduction in the plateau INa amplitude (0.94±0.02 to 0.63±0.02) than isoflurane (0.90±0.01 to 0.76±0.01; P < 0.05 by paired t-test, n=3). Repetitive pulse protocol: 25 ms, 10 Hz test pulses from holding potential of −120 mV to peak activation voltage.

Discussion

We compared the actions of five potent halogenated inhaled anesthetics on a single Na+ channel isoform (Nav1.4) expressed in a uniform mammalian cellular environment to enhance detection of possible agent specific effects on state-dependent inhibition. All five of these clinically used inhaled anesthetics, with representatives from both alkane and ether subclasses, inhibited currents conducted by the α-subunit of the Nav1.4 voltage-gated Na+ channel isoform at clinically relevant concentrations consistent with a role for blockade of Nav in anesthetic immobilization.1 There were differences between agents in their potencies for inhibition of Nav1.4 relative to their anesthetic potencies, as well as differences in the voltage-dependence of their inhibition. For example, at equi-anesthetic concentrations desflurane was the most effective inhibitor of peak INa from a near physiological holding potential of −80 mV while halothane was most effective from a hyperpolarized holding potential of −120 mV. Thus members of the same drug class have agent-specific differences in their effects on a single target with potential pharmacological implications. A clinical implication of these findings is that inhibition of Nav1.4 could contribute to skeletal muscle relaxing effects of anesthetics given the high density of Nav1.4 at the neuromuscular junction.12 Indeed the greater inhibition of Nav1.4 by desflurane at 1 MAC correlates with its relatively greater enhancement of nondepolarizing neuromuscular blocking drug potency during anesthesia in vivo in human subjects.22

Inhibition of Nav1.4 from a hyperpolarized holding potential is consistent with anesthetic block of the closed resting state.21 Our results are comparable to those reported for the cardiac isoform Nav1.5, for which equi-anesthetic concentrations of halothane are more potent than isoflurane in tonic blockade of human9 and guinea pig23 cardiac INa. Isoflurane, halothane and desflurane, which were analyzed in more detail, exhibited state-dependent block and a negative shift in the voltage dependence of inactivation, consistent with enhancement of inactivation at physiological holding potentials. State-dependent block has been reported previously for isoflurane effects on INa in rat neurohypophysial nerve terminals,7 guinea pig cardiomyocytes,23 and heterologously expressed Nav1.2, Nav1.4, Nav1.5 and Nav1.6.8–11 Moreover, isoflurane and halothane affected channel gating evident as accelerated current decay and use-dependent block (halothane > isoflurane). The similarity of these effects of inhaled anesthetics to the effects of local anesthetics, antidepressants and anticonvulsants on Nav1.2 and Nav1.413–17 currents suggests conserved or overlapping drug binding sites and/or allosteric conformational mechanisms for these chemically diverse Na+ channel antagonists. The relative contributions of open state block and enhanced fast and/or slow inactivation to use-dependent block by inhaled anesthetics, which differs between various Na+ channel blockers, should be resolvable by examining anesthetic effects on fast inactivation-deficient Na+ channels.

Inhaled anesthetics are known to inhibit various isoforms of Nav α-subunits heterologously expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells (rat Nav1.2, Nav1.4 and Nav1.5),11 human embryonic kidney cells (HEK 293, human Nav1.5),9 and Xenopus oocytes (rat Nav1.2 and 1.6, human Nav1.4).10 Small differences in potencies reported between various studies probably result from differences in isoform sensitivity, species, expression systems, β-subunit co-expression, recording conditions, stimulation protocols, anesthetic concentration determinations, etc. Isoflurane at clinically relevant concentrations inhibits rat neuronal (Nav1.2), skeletal muscle (Nav1.4), and cardiac muscle (Nav1.5) voltage-gated Na+ channel α-subunits studied under identical conditions with isoform-dependent differences in state-dependent block.11 Significantly lower IC50 values for isoflurane were observed at more physiological holding potentials11 due to marked voltage-dependent effects on channel gating compared to the hyperpolarized potential used to characterize tonic block in the current study. The IC50 for inhibition of Nav1.4 by isoflurane reported previously for a holding potential of −100 mV (IC50=0.99 mM)11 compares well with the value obtained in the present study for a holding potential of −120 mV (IC50=1.16 mM). Rat Nav1.8 in Xenopus oocytes has been reported to be insensitive to isoflurane,10 but recent evidence indicates that rat Nav1.8 expressed in a mammalian neuroblastoma cell line is inhibited by isoflurane at concentrations comparable to those effective on other isoforms (unpublished data, 2008, Karl F. Herold, M.D. and Hugh C. Hemmings, M.D., Ph.D., New York NY). Thus all mammalian Nav isoforms tested so far are susceptible to inhibition by the prototypical inhaled anesthetic isoflurane with minor isoform-specific differences in relative potency and mechanism.

Human Nav1.4 heterologously expressed in Xenopus oocytes is inhibited by isoflurane and halothane,10 whereas rat Nav1.4 in the same expression system was reported to be insensitive to halothane unless co-expressed with protein kinase C (PKC).24 Our results indicate that rat Nav1.4 expressed in a mammalian cell line is inhibited by multiple inhaled anesthetics in the absence of over-expression or pharmacological activation of PKC indicating that PKC activation is apparently not required for inhibition. A requirement for activation of endogenous PKC, which can be activated by halogenated inhaled anesthetics,25 cannot be excluded however. Attempts to test this possibility by inhibition of endogenous PKC using small molecule PKC inhibitors have been unsuccessful since the PKC inhibitors themselves inhibit Na+ channels.26

Inhaled anesthetics negatively shift the voltage dependence of INa fast inactivation. Similar shifts in inactivation of INa are produced in ventricular cardiomyocytes by isoflurane and halothane,9 and in rat neurohypophysial nerve terminals7 and heterologously expressed Nav isoforms by isoflurane.10,11 Negative shifts in the voltage dependence of fast inactivation suggest greater anesthetic binding affinity and selective stabilization of inactivated states. The large negative shift in V1/2in by desflurane contributes to its greater potency compared to isoflurane and halothane for inhibition of Nav1.4 from the more positive (physiological) holding potential of −80 mV vs. −120 mV. Preferential anesthetic interaction with the nonconducting inactivated state of Nav1.4 is also consistent with anesthetic slowing of recovery from fast inactivation. The slightly greater slowing effect of halothane compared to isoflurane is consistent with a greater shift in V1/2in and hence stronger interaction with the fast inactivated state for halothane.

Enhanced inactivation is critical to inhibition of Nav1.4 by inhaled anesthetics at more positive membrane potentials. This has classically been attributed to fast inactivation, but recent evidence implicates slow inactivation in activity-dependent attenuation of Nav currents.4 The possible role of slow inactivation in the Na+ channel blocking effects of inhaled anesthetics is not clear, but is an important area for future investigation that will be facilitated using mutations in Nav1.4 that enhance or remove inactivation.27 Possible mechanisms underlying state-dependent effects include facilitated transitions from the closed to inactivated state (tonic block), open to inactivated state (enhanced inactivation), and/or stabilization of inactivated states (delayed recovery). Small differences between anesthetics in their state-dependent effects on various Nav isoforms11 could underlie anesthetic- and isoform-specific differences in pharmacological profiles of specific anesthetics in vivo, e.g., differential effects on brain, heart and skeletal muscle.

All five inhaled anesthetics tested produced insignificant shifts in the voltage dependence of Nav1.4 activation, similar to the findings of Stadnicka et al.,9 but in contrast to those of Weigt et al.23 who found small negative shifts for Nav1.5. These findings suggest isoform-selective interactions between volatile anesthetics and the activation process similar to those observed for the local anesthetic lidocaine.28 Another class of anesthetics, the n-alkanols, also inhibits voltage-gated Na+ channels at anesthetic concentrations, but with somewhat distinct mechanisms from those of inhaled anesthetics that involve primarily open channel block with relatively small effects on both activation and inactivation.29 Thus the n-alkanols and inhaled anesthetics both inhibit Na+ channels, but differ in the relative involvement of open channel block and activation (greater for the alkanols) versus inactivation mechanisms (greater for inhaled anesthetics).

Both halothane and isoflurane exhibited use-dependent block with repetitive stimuli. The fraction of open versus inactivated channels increases during fast repetitive depolarizations, so the presence of use-dependent block suggests a possible role for open-channel block and/or slow inactivation mechanisms by both anesthetics.17,21 Halothane was more efficacious than isoflurane in inhibiting normalized current amplitude with repetitive stimuli consistent with its greater tonic INa blocking effect. Open-channel block is particularly important in pathological conditions such as myotonia and periodic paralysis that involve Nav1.4 inactivation gating defects,30 inflammatory and neuropathic pain states that involve repetitive activation of Nav1.7 and Nav1.8,31,32 and ischemia which leads to resting membrane depolarization.33

Accessory subunits can have important effects on the pharmacological and gating properties of voltage-gated Na+ channels that must be considered in pharmacological studies, although α-subunit expression is sufficient to mimic native Na+ channel gating properties.4 Modulation of Nav function by β–subunits depends on both the α subunit isoform and the cell type used for expression. Co-expression of the β1-subunit has no effect on inhibition by isoflurane of Nav1.2, Nav1.4, Nav1.6 or Nav1.8 α-subunits expressed in Xenopus oocytes.10 In mammalian expression systems, β1-subunit co-expression has no major effects on local anesthetic sensitivity, current kinetics, or activation and inactivation properties of tetrodotoxin-sensitive currents in ND7/23 cells,34 but produces positive shifts of channel activation and inactivation of Nav1.2 in tsA-201 cells35 and positive shifts of inactivation but no change in cocaine affinity of Nav1.4 and Nav1.5 in human embryonic kidney 293t cells36 Although we have not ruled out possible effects of β–subunit co-expression on inhaled anesthetic sensitivity of Nav1.4 in Chinese hamster ovary cells, taken together these findings make a major effect unlikely.

The role of voltage-gated Na+ channels in the mechanisms of inhaled anesthetics is an important and unresolved question, but a number of factors impede its resolution.1 Correlations between in vitro effects on Na+ currents and anesthetic potencies in vivo are limited by our ignorance regarding the specific cells, networks and molecular targets involved in the behavioral effects of inhaled anesthetics (immobilization in the case of MAC). Thus we are unable to define the degree of Na+ channel inhibition critical for an anesthetic effect that must be taken into consideration when evaluating correlations between potencies measured in vitro and in vivo. Interestingly, experiments with local anesthetics suggest that relatively small degrees of Nav blockade (10–20% inhibition of peak current amplitude) can have profound effects on neuronal firing rate.37 Moreover, determination of anesthetic effects on ion channels in vitro is subject to numerous experimental variables including the species and isoform of the channel, expression system used, accessory subunits, modulation by cellular signaling pathways, temperature, experimental conditions including holding potentials and stimulus protocols, etc. These and other factors can have profound effects on channel function and pharmacological sensitivity. Given these reservations, the observation that all five inhaled anesthetics tested inhibit Nav1.4 supports, but does not prove, an important role for Nav inhibition in anesthesia. Additional support for this hypothesis is provided by the recent observation that intrathecal administration of the Nav agonist veratridine increases MAC in rats.38

In summary, halogenated inhaled anesthetics all inhibit heterologously expressed Nav1.4 at clinical concentrations by state-dependent mechanisms. These findings support inhibition of Nav as a common mechanism for inhaled anesthetic action. Small agent-specific differences in relative potency and gating effects are consistent with subtle inter-agent variability in pharmacodynamic profiles, such as skeletal muscle relaxant effects. Agent-specific differences in potency for Nav1.4 inhibition at normal resting membrane potential were determined primarily by differences in state-dependent block reflected in effects on inactivation gating. These gating effects of inhaled anesthetics are remarkably similar to those of local anesthetics, and suggest the possibility of overlapping binding sites,13–17 an interesting hypothesis that can now be tested by detailed structure-function studies in Nav1.4 using mutations that affect gating mechanisms and local anesthetic sensitivity.

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, Maryland) grant GM 58055 (to H.C.H). K.F.H. was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Bonn, Germany) fellowship HE4554/5-1.

References

- 1.Hemmings HC, Jr, Akabas MH, Goldstein PA, Trudell JR, Orser BA, Harrison NL. Emerging mechanisms of general anesthetic action. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:503–10. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu XS, Sun JY, Evers AS, Crowder M, Wu LG. Isoflurane inhibits transmitter release and the presynaptic action potential. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:663–70. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200403000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ouyang W, Hemmings HC., Jr Depression by isoflurane of the action potential and underlying voltage-gated ion currents in isolated rat neurohypophysial nerve terminals. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;312:801–8. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.074609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldin AL. Resurgence of sodium channel research. Annu Rev Physiol. 2001;63:871–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ratnakumari L, Hemmings HC., Jr Inhibition of presynaptic sodium channels by halothane. Anesthesiology. 1998;88:1043–54. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199804000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ratnakumari L, Vysotskaya TN, Duch DS, Hemmings HC., Jr Differential effects of anesthetic and nonanesthetic cyclobutanes on neuronal voltage-gated sodium channels. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:529–41. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200002000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ouyang W, Wang G, Hemmings HC., Jr Isoflurane and propofol inhibit voltage-gated sodium channels in isolated rat neurohypophysial nerve terminals. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;64:373–81. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.2.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rehberg B, Xiao YH, Duch DS. Central nervous system sodium channels are significantly suppressed at clinical concentrations of volatile anesthetics. Anesthesiology. 1996;84:1223–33. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199605000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stadnicka A, Kwok WM, Hartmann HA, Bosnjak ZJ. Effects of halothane and isoflurane on fast and slow inactivation of human heart hH1a sodium channels. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:1671–83. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199906000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shiraishi M, Harris RA. Effects of alcohols and anesthetics on recombinant voltage-gated Na+ channels. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;309:987–94. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.064063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ouyang W, Hemmings HC., Jr Isoform-selective effects of isoflurane on voltage-gated Na+ channels. Anesthesiology. 2007;107:91–8. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000268390.28362.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Awad SS, Lightowlers RN, Young C, Chrzanowska-Lightowlers ZM, Lomo T, Slater CR. Sodium channel mRNAs at the neuromuscular junction: distinct patterns of accumulation and effects of muscle activity. J Neurosci. 2001;21:8456–63. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-21-08456.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ragsdale DS, McPhee JC, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Molecular determinants of state-dependent block of Na+ channels by local anesthetics. Science. 1994;265:1724–28. doi: 10.1126/science.8085162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang GK, Quan C, Wang S. A common local anesthetic receptor for benzocaine and etidocaine in voltage-gated mu1 Na+ channels. Pflugers Arch. 1998;435:293–302. doi: 10.1007/s004240050515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang SY, Nau C, Wang GK. Residues in Na+ channel D3-S6 segment modulate both batrachotoxin and local anesthetic affinities. Biophys J. 2000;79:1379–87. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76390-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nau C, Wang SY, Wang GK. Point mutations at L1280 in Nav1.4 channel D3-S6 modulate binding affinity and stereoselectivity of bupivacaine enantiomers. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:1398–406. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.6.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang GK, Russell C, Wang SY. State-dependent block of voltage-gated Na+ channels by amitriptyline via the local anesthetic receptor and its implication for neuropathic pain. Pain. 2004;110:166–74. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflugers Arch. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.West JW, Scheuer T, Maechler L, Catterall WA. Efficient expression of rat brain type IIA Na+ channel alpha subunits in a somatic cell line. Neuron. 1992;8:59–70. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90108-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taheri S, Halsey MJ, Liu J, Eger EI, 2nd, Koblin DD, Laster MJ. What solvent best represents the site of action of inhaled anesthetics in humans, rats, and dogs? Anesth Analg. 1991;72:627–34. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199105000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hille B. Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes. 3. Sinauer Associates, Inc; Sunderland, Massachusetts: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wulf H, Ledowski T, Linstedt U, Proppe D, Sitzlack D. Neuromuscular blocking effects of rocuronium during desflurane, isoflurane, and sevoflurane anaesthesia. Can J Anaesth. 1998;45:526–32. doi: 10.1007/BF03012702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weigt HU, Kwok WM, Rehmert GC, Turner LA, Bosnjak ZJ. Voltage-dependent effects of volatile anesthetics on cardiac sodium current. Anesth Analg. 84:285–93. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199702000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mounsey JP, Patel MK, Mistry D, John JE, Moorman JR. Protein kinase C co-expression and the effects of halothane on rat skeletal muscle sodium channels. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;128:989–98. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hemmings HC, Jr, Adamo AIB. Activation of endogenous protein kinase C by halothane in synaptosomes. Anesthesiology. 1996;84:652–62. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199603000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ratnakumari L, Vysotskaya TN, Duch DS, Hemmings HC., Jr Inhibition of voltage-dependent sodium channels by Ro 31-8220, a ‘specific’ protein kinase C inhibitor. FEBS Lett. 2000;473:265–8. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01532-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Reilly JP, Wang SY, Wang GK. Residue-specific effects on slow inactivation at V787 in D2-S6 of Na(v)1.4 sodium channels. Biophys J. 2001;81:2100–11. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75858-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hofer D, Lohberger B, Steinecker B, Schmidt K, Quasthoff S, Schreibmayer W. A comparative study of the action of tolperisone on seven different voltage dependent sodium channel isoforms. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;538:5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horishita T, Harris RA. n-Alcohols inhibit voltage-gated Na+ channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;326:270–7. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.138370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cannon SC. Pathomechanisms in channelopathies of skeletal muscle and brain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2006;29:387–41. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.112815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benarroch EE. Sodium channels and pain. Neurology. 2007;68:233–6. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000252951.48745.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jarvis MF, Honore P, Shieh CC, Chapman M, Joshi S, Zhang XF, Kort M, Carroll W, Marron B, Atkinson R, Thomas J, Liu D, Krambis M, Liu Y, McGaraughty S, Chu K, Roeloffs R, Zhong C, Mikusa JP, Hernandez G, Gauvin D, Wade C, Zhu C, Pai M, Scanio M, Shi L, Drizin I, Gregg R, Matulenko M, Hakeem A, Gross M, Johnson M, Marsh K, Wagoner PK, Sullivan JP, Faltynek CR, Krafte DS. A-803467, a potent and selective Nav1.8 sodium channel blocker, attenuates neuropathic and inflammatory pain in the rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:8520–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611364104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hemmings HC., Jr Neuroprotection by Na+ channel blockade. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2004;16:100–1. doi: 10.1097/00008506-200401000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leffler A, Reiprich A, Mohapatra DP, Nau C. Use-dependent block by lidocaine but not amitriptyline is more pronounced in tetrodotoxin (TTX)-resistant Nav1.8 than in TTX-sensitive Na+ channels. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;320:354–64. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.109025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qu Y, Curtis R, Lawson D, Gilbride K, Ge P, DiStefano PS, Silos-Santiago I, Catterall WA, Scheuer T. Differential modulation of sodium channel gating and persistent sodium currents by the beta1, beta2, and beta3 subunits. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2001;18:570–80. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2001.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wright SN, Wang SY, Xiao YF, Wang GK. State-dependent cocaine block of sodium channel isoforms, chimeras, and channels coexpressed with the beta1 subunit. Biophys J. 1999;76:233–45. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77192-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scholz A, Kuboyama N, Hempelmann G, Vogel W. Complex blockade of TTX-resistant Na+ currents by lidocaine and bupivacaine reduce firing frequency in DRG neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:1746–54. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.4.1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Y, Sharma M, Eger EI, 2nd, Laster MJ, Hemmings HC, Jr, Harris RA. Intrathecal veratridine administration increases minimum alveolar concentration in rats. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:875–8. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181815fbc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]