Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To compare the effects of a 1-year intervention with a low-carbohydrate and a low-fat diet on weight loss and glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

This study is a randomized clinical trial of 105 overweight adults with type 2 diabetes. Primary outcomes were weight and A1C. Secondary outcomes included blood pressure and lipids. Outcome measures were obtained at 3, 6, and 12 months.

RESULTS

The greatest reduction in weight and A1C occurred within the first 3 months. Weight loss occurred faster in the low-carbohydrate group than in the low-fat group (P = 0.005), but at 1 year a similar 3.4% weight reduction was seen in both dietary groups. There was no significant change in A1C in either group at 1 year. There was no change in blood pressure, but a greater increase in HDL was observed in the low-carbohydrate group (P = 0.002).

CONCLUSIONS

Among patients with type 2 diabetes, after 1 year a low-carbohydrate diet had effects on weight and A1C similar to those seen with a low-fat diet. There was no significant effect on blood pressure, but the low-carbohydrate diet produced a greater increase in HDL cholesterol.

Type 2 diabetes affects >20 million people in the U.S. (1). Optimal weight loss strategies in patients with type 2 diabetes continue to be debated, and the best dietary strategy to achieve both weight loss and glycemic control in type 2 diabetes is unclear.

Prior studies, done primarily in patients without diabetes, demonstrated weight loss outcomes with low-carbohydrate diets comparable to that with other diets (2–6). Based on the effectiveness of low-carbohydrate diets for weight loss, recent guidelines from the American Diabetes Association state that for short-term weight loss either a low-carbohydrate or low-fat calorie-restricted diet may be effective (7).

In addition to weight loss, the metabolic effects of low-carbohydrate diets may be of particular benefit in type 2 diabetes. Carbohydrates are the primary source of glucose for metabolism, and restricting carbohydrate intake can reduce insulin levels, reduce postprandial hyperglycemia, and improve insulin sensitivity (8,9). In short-term randomized studies and long-term observational studies, low-carbohydrate diets have shown benefits for improving glycemic control in type 2 diabetes (9–12).

To date, studies examining low-carbohydrate diets specifically in patients with type 2 diabetes have had small sample sizes, lacked control groups, or had short follow-up (13). We conducted a nonblinded, two-arm randomized clinical trial to compare the effects of a 1-year intervention of a low-carbohydrate diet with those of a low-fat diet on weight and glycemic control in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes. We hypothesized that a low-carbohydrate diet would result in greater improvement in weight and glycemic control compared with a low-fat diet.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Eligible participants were adults aged >18 years with a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes for at least 6 months, BMI ≥25 kg/m2, and A1C between 6 and 11%. Exclusion criteria were a weight change of >10 pounds within 3 months of screening, kidney disease (defined as creatinine >1.3 mg/dl), active liver or gallbladder disease, significant heart disease, a history of severe (requiring hospitalization) hypoglycemia, or use of weight loss medications. Participants were recruited from the offices of primary care physicians, endocrinologists, and the local community in Bronx, New York, through physician referral, letters of invitation, and posted advertisements. All study visits occurred at the Clinical Research Center of Albert Einstein College of Medicine. The study was approved by the internal review boards of Albert Einstein College of Medicine and Montefiore Medical Center. All participants provided written informed consent.

Screening and enrollment

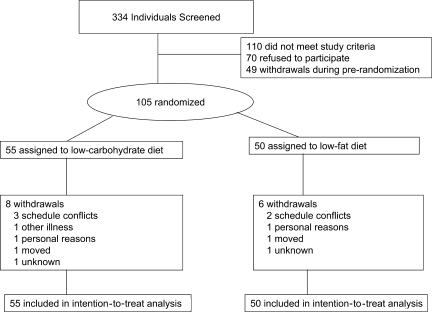

Study enrollment was completed between August 2004 and November 2006. As seen in Fig. 1, 334 individuals responded to the recruitment effort and 154, who were eligible, entered a 3- to 4-week prerandomization protocol. During prerandomization, participants received instructions and were asked to complete dietary and blood glucose self-monitoring activities. Participants received self-monitoring supplies that included measuring cups, food scales, and blood glucose meters with test strips (Ascensia Elite XL). Forty-nine participants discontinued the study during prerandomization, leaving 105 participants who were randomly assigned.

Figure 1.

Participant flow.

Dietary interventions

By using a computer-generated 1:1 randomization, participants were assigned to either a low-carbohydrate or a low-fat diet. The low-carbohydrate diet was modeled after the Atkins diet (14) and was initiated with a 2-week phase of carbohydrate restriction of 20–25 g daily depending on baseline weight. As participants lost weight, they were able to increase carbohydrate intake at 5-g increments each week. The low-fat diet was modeled after that in the Diabetes Prevention Program (15). Participants received a fat gram goal, which was 25% of energy needs, based on baseline weight. Participants in each arm received a booklet with the carbohydrate or fat content of common foods and instructions for self-monitoring. Participants were responsible for their own food purchases and food preparation. We provided participants with general recommendations to achieve 150 min of physical activity each week, but physical activity was not an emphasis of the study.

Nutrition counseling

At randomization, all participants received 45 min of individual dietary instruction by a registered dietitian and were given a specific gram allowance of carbohydrates or fat to achieve a 1-pound weight loss each week. Structured menus that provided meal choices and recipes were used for the first 2 weeks (16). After the first 2 weeks, participants were instructed on selecting foods that met their dietary goals without using the menus. During the 12-month study, participants had a total of six scheduled, 30-min visits with the dietitian for additional dietary counseling.

Medication adjustments

During prerandomization, we adjusted diabetes medications to minimize side effects that could affect study findings, e.g., discontinuing thiazolidinediones (due to weight gain as a side effect) (17) and changing short-acting insulin to insulin glargine to minimize the risk of hypoglycemia (18). At randomization and during the remainder of the study, we used a predefined algorithm for medication adjustments. The algorithm was developed by study investigators based on clinical experience and prior diabetes studies (19,20) and reviewed by a clinical panel of experts that included diabetologists, dietitians, primary care providers, and a certified diabetes educator. At randomization, the algorithm included reducing insulin dosages by 50% and discontinuing sulfonylurea in the low-carbohydrate arm and reducing insulin by 25% and decreasing the sulfonylurea dose by 50% in the low-fat arm. Subsequently, the algorithm for medication adjustment was the same in both groups. Adjustments of insulin and sulfonylurea were made based on results of self-monitored capillary blood glucose. Metformin was not adjusted during the study.

Study visits

For the 1st month after randomization, participants had individual study visits once or twice weekly and after the 1st month, participants had scheduled visits every 6 weeks. During these visits, weight and blood pressure was measured, and participants received counseling from the study staff (study physician and research assistant), which focused on diabetes management, adjustment of diabetes medications, and dietary adherence. Ascertainment of study outcomes was done during the scheduled study visits closest to the 3-, 6-, and 12-month time point after randomization.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes were weight and glycemic control (measured by A1C). In addition, we collected data on blood pressure (measured with a manual sphygmomanometer after a 5-min rest period) and lipids (measured from serum samples collected after an overnight fast). Weight was measured with participants in light clothing and bare feet, using a digital scale (Tanita BF 681). A1C, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides were measured by enzymatic immunoassay (Olympus AU400 chemistry autoanalyzer). LDL levels were calculated using the Friedewald equation (21). All laboratory analyses were done in the Clinical Research Center.

Dietary intake

At baseline, 6 months, and 12 months, we collected single-day 24-h recall by in-person interviews. Participants were also instructed to keep daily food diaries, which were reviewed during the study visits. Because 24-h recall was not collected as a part of the study protocol at 3 months, we obtained dietary data for 3 months by analyzing participant food diaries for 1 day before their 3-month appointment. Nutrient data were analyzed using FoodWorks version 8.01.

Statistical analysis

Means ± SD describe the distribution of baseline variables. Primary outcomes were 12-month changes in weight and A1C. Hierarchical linear models were used to analyze all available data. We fitted a linear spline model, dividing study time into two phases: an early phase (months 0–3) and a late phase (months 3–12). Person-level random slopes during both phases and intercepts at the person level were included. Treatment group was represented by an indicator variable, and coefficients of treatment × time interaction terms were used for inference about dietary differences. To control for medication changes, we included the change in insulin and change in sulfonylurea at each time point as a covariate in the model with age, sex, and race. Medication changes were not significantly associated with weight and were dropped from the weight model. The analyses were done with and without imputation of missing values.

Repeated-measures ANOVAs with diet as the between-subject factor and time as the within-subject factor were used to compare mean changes of blood pressure and lipids. Unpaired t tests or Wilcoxon rank tests were used to compare dietary composition at each time point. For these analyses, we included only data for which there were results for all time points.

With a sample size of 105 participants, we had 80% power to detect a mean ± SD difference in weight of 2.0 ± 3.3 kg and in A1C of 0.7 ± 1.3% between dietary arms. All statistical tests were two-tailed with a significance level of 0.05. Analyses were done with SPSS 15.0 and STATA 10.1.

RESULTS

At baseline, participants were similar in demographic characteristics, glycemic control, diabetes medications, blood pressure, and lipids (Table 1). Only 13% reported current tobacco use, and this percentage did not differ between dietary arms. Baseline differences in weight between the dietary arms were adjusted for in the statistical model.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants

| Low-carbohydrate diet | Low-fat diet | |

|---|---|---|

| n | 55 | 50 |

| Age (years) | 54 ± 6 | 53 ± 7 |

| Female sex | 45 (82) | 37 (74) |

| Race | ||

| Black | 34 (62) | 33 (66) |

| Hispanic | 8 (15) | 9 (18) |

| White | 8 (15) | 7 (14) |

| Asian | 2 (4) | 1 (2) |

| Other | 2 (4) | 0 |

| Physical measures | ||

| Weight (kg) | 93.6 ± 18 | 101 ± 19 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 35 ± 6 | 37 ± 6 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 125 ± 18 | 130 ± 17 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 73 ± 9 | 77 ± 10 |

| Clinical | ||

| A1C (%) | 7.5 ± 1.5 | 7.4 ± 1.4 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l) | 4.4 ± 0.83 | 4.3 ± 0.86 |

| LDL (mmol/l) | 2.5 ± 0.69 | 2.4 ± 0.74 |

| HDL (mmol/l) | 1.3 ± 0.24 | 1.2 ± 0.29 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/l) | 1.4 ± 0.84 | 1.4 ± 0.67 |

| Medications | ||

| Metformin | 43 (78) | 43 (86) |

| Sulfonylurea | 24 (44) | 26 (52) |

| Insulin | 19 (35) | 12 (24) |

| Cholesterol-lowering medication | 34 (62) | 28 (56) |

Data are means ± SD or n (%) unless otherwise noted.

Attrition

Data collection of weight and A1C was complete for 91% of participants at 3 months (n = 95), 80% of participants at 6 months (n = 84), and 81% of participants at 12 months (n = 85). There was no difference in attrition between dietary arms.

Weight

Weight change at each time point is shown in Table 2. After adjustment for age and sex, baseline differences in weight were not significant (P = 0.149). During the first 3 months, the low-carbohydrate group lost an average of 1.7 kg/month (95% CI 1.4–2.0) and in months 3–12 gained an average of 0.23 kg/month (95% CI 0.09–0.35). The low-fat group in contrast lost weight at a slower rate of 1.2 kg/month (95% CI 0.86–1.5) and plateaued during months 3–12 with an average weight gain of <0.01 kg/month (95% CI −0.13 to 0.14). At 1 year, there was a 3.4% weight reduction in both groups. The difference in the early- and late-phase rates of weight change between the dietary groups was significant (P = 0.005). In a sensitivity analysis that carried forward the baseline weight for missing values, the findings were similar.

Table 2.

Change in anthropometric and metabolic outcomes at 3, 6, and 12 months after diet initiation

| 3 months | 6 months | 12 months | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1C | ||||

| Low-carbohydrate diet | −0.64 ± 1.4 | −0.29 ± 0.92 | −0.02 ± 0.89 | 0.71 |

| Low-fat diet | −0.26 ± 1.1 | −0.15 ± 1.1 | 0.24 ± 1.4 | |

| Weight (kg)* | ||||

| Low-carbohydrate diet | −5.2 ± 2.8 | −4.8 ± 3.5 | −3.1 ± 4.8 | 0.005 |

| Low-fat diet | −3.2 ± 3.7 | −4.4 ± 5.3 | −3.1 ± 5.8 | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | ||||

| Low-carbohydrate diet | −5.8 ± 19.2 | −0.78 ± 17.7 | 2.0 ± 15.6 | 0.15 |

| Low-fat diet | −0.98 ± 21.0 | −37 ± 19.8 | −1.8 ± 22.6 | |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | ||||

| Low-carbohydrate diet | −2.2 ± 12.5 | −0.93 ± 12.4 | −2.9 ± 9.4 | 0.62 |

| Low-fat diet | −0.40 ± 12.6 | 0.95 ± 9.8 | −2.2 ± 11.6 | |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l)† | ||||

| Low-carbohydrate diet | 0.05 ± 0.79 | 0.10 ± 0.76 | 0.37 | |

| Low-fat diet | −0.27 ± 0.74 | −0.13 ± 0.70 | ||

| LDL (mmol/l) | ||||

| Low-carbohydrate diet | −0.10 ± 0.52 | −0.04 ± 0.63 | 0.23 | |

| Low-fat diet | −0.25 ± 0.56 | −0.18 ± 0.66 | ||

| HDL (mmol/l) | ||||

| Low-carbohydrate diet | 0.16 ± 0.28 | 0.16 ± 0.27 | 0.002 | |

| Low-fat diet | −0.01 ± 0.22 | 0.06 ± 0.21 | ||

| Triglycerides (mmol/l) | ||||

| Low-carbohydrate diet | −0.02 ± 0.85 | −0.15 ± 0.88 | 0.53 | |

| Low-fat diet | 0.04 ± 0.56 | −0.01 ± 0.86 |

Data are means ± SD.

*P values for diet difference over all time points.

†Lipid values were not collected at 3 months.

Glycemic control

Change in A1C at each time is seen in Table 2. There was no difference in the rate of change in A1C in either the early or late phase of dietary intervention. On average, participants experienced a decrease in A1C of 0.12 per month during the early phase (months 0–3) but an increase of 0.06 per month during the late phase (months 3–12). Participants with higher baseline A1C levels had more rapid declines in A1C during the first 3 months (r = –0.35, 95% CI –0.11 to –0.55), but baseline levels did not affect the rate of change in A1C in months 3–12. There was an association between medication changes and A1C such that increases in insulin dose or sulfonylurea dose were associated with slightly higher A1C levels. Of the participants using insulin, the dose was reduced by a mean ± SD of 10 ± 14 units in the low-carbohydrate arm and increased by 4 ± 19 units in the low-fat arm (P = 0.12) at 12 months. Of the participants, 26% of those prescribed sulfonylureas had a reduction in sulfonylurea dose at 12 months. The change in sulfonylurea dose was a 1.6 ± 3.6 mg reduction in both arms. Imputation of baseline measurements for missing A1C values yielded similar results.

Blood pressure

Systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure were similar between dietary groups at baseline and did not change over the 12-month period (Table 2).

Lipids

Over 12 months, there were no significant differences in total cholesterol, triglycerides, or calculated LDL between dietary groups. There was a significant increase in HDL in the low-carbohydrate group, which occurred at 6 months and was sustained at 12 months (Table 2).

Dietary adherence

At baseline, dietary groups did not differ with respect to calorie or macronutrient intake; ∼43% of calories were from carbohydrates, 36% were from fat, and 23% were from proteins. Based on food records, at 3 months participants in the low-carbohydrate arm had an intake of 24% of calories from carbohydrate (equivalent to 77 ± 44 g of carbohydrates daily) and 49% of calories from fat. The low-fat group had an intake of 53% of calories from carbohydrate (equivalent to 199 ± 69 g of carbohydrates) and an intake of 25% of calories from fat. As seen in Table 3, at 6 and 12 months, there was an increase in calories and macronutrients in both groups, suggesting decreased adherence.

Table 3.

Dietary intake at each time point

| Baseline | 6 months* | 12 months† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caloric intake (kcal/day) | |||

| Low-carbohydrate diet | 1,983 ± 650 | 1,652 ± 650 | 1,642 ± 600 |

| Low-fat diet | 1,863 ± 450 | 1,653 ± 471 | 1,810 ± 590 |

| P value for low-carbohydrate diet vs. low-fat diet | 0.28 | 0.99 | 0.30 |

| Carbohydrate intake (% total energy) | |||

| Low-carbohydrate diet | 43.9 ± 9.1 | 33.5 ± 14.7 | 33.4 ± 13.2 |

| Low-fat diet | 41.2 ± 10.4 | 48.1 ± 14.1 | 50.1 ± 10.0 |

| P value for low-carbohydrate diet vs. low-fat diet | 0.14 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Fat intake (% total energy) | |||

| Low-carbohydrate diet | 36.1 ± 7.6 | 43.0 ± 13.1 | 43.9 ± 10.8 |

| Low-fat diet | 38.8 ± 9.4 | 30.8 ± 9.8 | 30.8 ± 10.2 |

| P value for low-carbohydrate diet vs. low-fat diet | 0.12 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Saturated fat (% total fat)† | |||

| Low-carbohydrate diet | 31.3 ± 7.9 | 28.6 ± 8.8 | 28.7 ± 9.6 |

| Low-fat diet | 31.5 ± 7.0 | 30.7 ± 8.4 | 30.2 ± 5.4 |

| P value for low-carbohydrate diet vs. low-fat diet | 0.91 | 0.33 | 0.43 |

| Polyunsaturated fat (% total fat)† | |||

| Low-carbohydrate diet | 19.1 ± 7.6 | 19.1 ± 7.5 | 17.4 ± 8.0 |

| Low-fat diet | 19.6 ± 9.0 | 19.8 ± 8.0 | 21.4 ± 8.6 |

| P value for low-carbohydrate diet vs. low-fat diet | 0.76 | 0.70 | 0.06 |

| Monounsaturated fat (% total fat)† | |||

| Low-carbohydrate diet | 36.1 ± 7.0 | 39.5 ± 11.0 | 40.7 ± 10.4 |

| Low-fat diet | 37.6 ± 6.9 | 35.2 ± 8.7 | 38.1 ± 6.9 |

| P value for low-carbohydrate diet vs. low-fat diet | 0.28 | 0.08 | 0.25 |

| Protein intake (% total energy) | |||

| Low-carbohydrate diet | 19.5 ± 6.3 | 22.5 ± 6.0 | 22.7 ± 6.7 |

| Low-fat diet | 19.4 ± 6.6 | 20.5 ± 7.0 | 18.9 ± 4.7 |

| P value for low-carbohydrate diet vs. low-fat diet | 0.94 | 0.18 | 0.02 |

| Fiber (g/day) | |||

| Low-carbohydrate diet | 15.4 ± 8.5 | 12.6 ± 10.7 | 15.1 ± 9.5 |

| Low-fat diet | 14.9 ± 8.5 | 17.0 ± 9.7 | 17.2 ± 8.1 |

| P value for low-carbohydrate diet vs. low-fat diet | 0.78 | 0.09 | 0.36 |

Data are means ± SD.

*Based on 24-h recall from 68 participants.

†Based on 24-h recall from 57 participants.

CONCLUSIONS

Our results indicate that after 1 year, overweight patients with type 2 diabetes had similar weight reduction with both a low-carbohydrate and a low-fat diet. Similar to prior studies, we observed a more rapid weight loss after initiation of a low-carbohydrate diet and equivalent weight loss after 1 year (2,3). Despite modest weight reduction in both arms, there was no significant reduction in A1C. Participants in the low-carbohydrate arm achieved an initial mean reduction of A1C 0.6% in the first 3 months, but this was not sustained. Prior studies demonstrated that a 6-kg weight loss was associated with A1C reduction of 0.55% (22). Study participants achieved a 3-kg weight loss, which may not have been sufficient to affect A1C. The lack of change in A1C should also be taken in the context of reduced medications. One-third of all participants were taking thiazolidinedione medications before randomization, which were discontinued during prerandomization and were not restarted. In addition, there was an overall reduction in insulin and sulfonylurea dose. Perhaps we would have observed greater reductions in A1C if we did not make medication adjustments during the study; however, because we were concerned about hypoglycemia, not making adjustments would not have been appropriate.

The initial difference in weight loss between arms was similar to that observed previously (2,3). Although there is debate regarding the effects of macronutrient composition on weight loss, it would appear from our results that participants in the low-carbohydrate arm reduced their caloric intake to a greater extent than participants in the low-fat arm. In addition, low-carbohydrate arm participants had a greater reduction in insulin dose and because of the potential effect of insulin on weight gain, this reduction may have promoted a greater weight loss.

Dietary adherence is a key factor in achievement of weight loss with any diet (5). Our diverse patient population, 80% of whom were black or Hispanic, had high carbohydrate and fat intake at baseline. Culturally, diets of Hispanics may have higher amounts of carbohydrate intake than those of the general U.S. population (23) and following a low-carbohydrate diet may have posed an even greater challenge for this population.

We did not observe any change in blood pressure at 1 year but did observe an increase in HDL in participants in the low-carbohydrate arm, which is consistent with prior studies (2,24). Participants in the low-carbohydrate arm increased their total and monounsaturated fat intake, which may have contributed to this increase. In contrast with previous studies, we did not observe significant reductions in triglycerides, which may be due to low triglyceride levels at baseline.

We did not have outcomes of A1C and weight for 19% of participants at 12 months. This attrition rate is lower than that found in many dietary interventions (13). We analyzed the data, carrying forward baseline values for these missing outcomes, assuming that any weight lost during the study was regained. This analysis did not change our results. However, if participants withdrew because they gained weight beyond their baseline weight, then our weight results would be less favorable.

Several limitations should be considered in interpreting our findings. Despite randomization, participants in the low-fat arm were heavier at baseline than those in the low-carbohydrate arm. Although we controlled for this imbalance statistically, it raises the question of whether there were other unmeasured differences between the arms. We used single-day dietary recall or a single-day food record to assess dietary intake, either of which is subject to bias. Participants may not have fully recalled their dietary intake and, in addition, may have changed their dietary intake for the day before their scheduled appointment. We did not have objective measures of physical activity, which could be a confounder; however, given the similarity of our findings in both groups at 1 year, it is unlikely that there were significant changes in physical activity in either group.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that among overweight patients with type 2 diabetes, there was no significant difference in the weight or A1C change in participants after a low-carbohydrate compared with a low-fat diet for 12 months. Participants in both arms achieved an average 3.4% weight reduction but did not reduce A1C. Differences in the short-term effects of each diet were not sustained.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research grants through the Robert C. Atkins Foundation and the Diabetes Research and Training Center (P60 DK020541) and by Clinical and Translational Science Award UL1 RR025750.

We thank Bayer Pharmaceuticals and sanofi aventis for their donations. We thank Joy Pape for her advice and assistance.

No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Footnotes

Clinical trial reg. no. NCT00795691, clinicaltrials.gov.

The funding sources did not have any role in the design, implementation, or analysis of the study. The funding sources did not review the manuscript before publication.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

References

- 1. Cowie CC, Rust KF, Byrd-Holt DD, Eberhardt MS, Flegal KM, Engelgau MM, Saydah SH, Williams DE, Geiss LS, Gregg EW: Prevalence of diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in adults in the U.S. population: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2002. Diabetes Care 2006; 29: 1263– 1268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Foster GD, Wyatt HR, Hill JO, McGuckin BG, Brill C, Mohammed BS, Szapary PO, Rader DJ, Edman JS, Klein S: A randomized trial of a low-carbohydrate diet for obesity. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 2082– 2090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Samaha FF, Iqbal N, Seshadri P, Chicano KL, Daily DA, McGrory J, Williams T, Williams M, Gracely EJ, Stern L: A low-carbohydrate as compared with a low-fat diet in severe obesity. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 2074– 2081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stern L, Iqbal N, Seshadri P, Chicano KL, Daily DA, McGrory J, Williams M, Gracely EJ, Samaha FF: The effects of low-carbohydrate versus conventional weight loss diets in severely obese adults: one-year follow-up of a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2004; 140: 778– 785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dansinger ML, Gleason JA, Griffith JL, Selker HP, Schaefer EJ: Comparison of the Atkins, Ornish, Weight Watchers, and Zone diets for weight loss and heart disease risk reduction: a randomized trial. JAMA 2005; 293: 43– 53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shai I, Schwarzfuchs D, Henkin Y, Shahar DR, Witkow S, Greenberg I, Golan R, Fraser D, Bolotin A, Vardi H, Tangi-Rozental O, Zuk-Ramot R, Sarusi B, Brickner D, Schwartz Z, Sheiner E, Marko R, Katorza E, Thiery J, Fiedler GM, Bluher M, Stumvoll M, Stampfer MJ: Weight loss with a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or low-fat diet. N Engl J Med 2008; 359: 229– 241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bantle JP, Wylie-Rosett J, Albright AL, Apovian CM, Clark NG, Franz MJ, Hoogwerf BJ, Lichtenstein AH, Mayer-Davis E, Mooradian AD, Wheeler ML: Nutrition recommendations and interventions for diabetes: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2008; 31 ( Suppl. 1): S61– S78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Accurso A, Bernstein RK, Dahlqvist A, Draznin B, Feinman RD, Fine EJ, Gleed A, Jacobs DB, Larson G, Lustig RH, Manninen AH, McFarlane SI, Morrison K, Nielsen JV, Ravnskov U, Roth KS, Silvestre R, Sowers JR, Sundberg R, Volek JS, Westman EC, Wood RJ, Wortman J, Vernon MC: Dietary carbohydrate restriction in type 2 diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome: time for a critical appraisal. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2008; 5: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Boden G, Sargrad K, Homko C, Mozzoli M, Stein TP: Effect of a low-carbohydrate diet on appetite, blood glucose levels, and insulin resistance in obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Ann Intern Med 2005; 142: 403– 411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yancy WS, Jr, Foy M, Chalecki AM, Vernon MC, Westman EC: A low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet to treat type 2 diabetes. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2005; 2: 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nielsen JV, Joensson EA: Low-carbohydrate diet in type 2 diabetes: stable improvement of bodyweight and glycemic control during 44 months follow-up. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2008; 5: 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gannon MC, Nuttall FQ: Control of blood glucose in type 2 diabetes without weight loss by modification of diet composition. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2006; 3: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dyson PA: A review of low and reduced carbohydrate diets and weight loss in type 2 diabetes. J Hum Nutr Diet 2008; 21: 530– 538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Atkins RC: Dr. Atkins' New Diet Revolution. New York, Harper Collins, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, Nathan DM: Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 2002; 346: 393– 403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cunningham C, Johnson S, Cowell B, Souroudi N, Isaacson CJ, Davis NJ, Wylie-Rosett J: Menu plans in a diabetes self-management weight loss program. J Nutr Educ Behav 2006; 38: 264– 266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pi-Sunyer FX: The effects of pharmacologic agents for type 2 diabetes mellitus on body weight. Postgrad Med 2008; 120: 5– 17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bazzano LA, Lee LJ, Shi L, Reynolds K, Jackson JA, Fonseca V: Safety and efficacy of glargine compared with NPH insulin for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabet Med 2008; 25: 924– 932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bernstein R: Dr. Bernstein's Diabetes Solution: A Complete Guide to Achieving Normal Blood Sugars. New York, Little, Brown, 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gutierrez M, Akhavan M, Jovanovic L, Peterson CM: Utility of a short-term 25% carbohydrate diet on improving glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Nutr 1998; 17: 595– 600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Warnick GR, Knopp RH, Fitzpatrick V, Branson L: Estimating low-density lipoprotein cholesterol by the Friedewald equation is adequate for classifying patients on the basis of nationally recommended cutpoints. Clin Chem 1990; 36: 15– 19 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wing RR: Behavioral treatment of obesity: its application to type II diabetes. Diabetes Care 1993; 16: 193– 199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tucker KL, Bianchi LA, Maras J, Bermudez OI: Adaptation of a food frequency questionnaire to assess diets of Puerto Rican and non-Hispanic adults. Am J Epidemiol 1998; 148: 507– 518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yancy WS, Jr, Olsen MK, Guyton JR, Bakst RP, Westman EC: A low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet versus a low-fat diet to treat obesity and hyperlipidemia: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2004; 140: 769– 777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.