Abstract

Introduction

Eosinophilia in travelers returning from tropical countries is often caused by helminths. The high eosinophil counts arise particularly from tissue migration of invasive larvae.

Methods

Review of literature selected by means of a Medline search using the MeSH terms "eosinophilia" and "helminth."

Results

The patient’s geographic and alimentary history may suggest infection with particular parasitic worms. A targeted diagnostic approach is suggested. The physician should concentrate on the principal signs and be guided by the geographic and alimentary history. Elaborate diagnostic measures are seldom indicated.

Discussion

Although eosinophilia alone has low positive predictive value for a worm infection, it points clearly to helminthosis if the patient has recently returned from the tropics and the eosinophilia is new.

Keywords: eosinophilia, helminth infection, foreign travel, migration, differential diagnosis

Eosinophilia has a wide variety of causes, including allergic illnesses, skin diseases, malignant conditions or even medication use (1). Nonparasitic causes should therefore also be considered when attempting to establish the cause of eosinophilia (1). New-onset eosinophilia following a visit to the tropics, however, is most likely due to a worm infection (helminthosis). Up to 5% of asymptomatic travelers returning from the tropics have eosinophilia requiring diagnostic clarification and between 14% and 48% of these travelers with eosinophilia are suffering from a parasitosis requiring treatment (2–6). Screening of immigrants with eosinophilia has shown that helminths are present in up to 77% of cases depending on the country of origin (7, 8). On the other hand, the sensitivity and specificity of eosinophilia for diagnosing helminthosis are low and the positive predictive value was only about 10% in some studies (4).

In medical practice, an increased percentage of eosinophilic granulocytes in the differential blood count is often erroneously referred to as "eosinophilia." In fact, the decisive factor is the number of eosinophilic granulocytes per µL blood. Healthy persons have on average fewer than 450 eosinophils per µL blood. Depending on the time of day, this value can vary by as much as 40% depending on the cortisol level (9). The patient’s age, physical training condition as well as environmental factors (especially allergen exposure) also influence the eosinophil count in peripheral blood. The degree of eosinophilia can be categorized as follows:

Mild eosinophilia: up to 1500/µL

Moderate to severe eosinophilia >1500/µL (according to [10], modified).

Another helpful laboratory parameter is total IgE. An increase in the IgE concentration occurs in various worm diseases. Mutual pathophysiological relationships, but only a low correlation exist between IgE and eosinophilia (11).

No guidelines are yet available for diagnostic evaluation of eosinophilia in the primary care setting. Physicians frequently contact institutes of tropical medicine for advice. In the following, the authors recommend structured screening programs guided by the geographic history and cardinal symptoms. These programs are based on epidemiological data on imported diseases (12–20), especially surveillance data from the GeoSentinel Network (21–23). An economical procedure and the lowest possible stress for the patient were also among the goals in developing these programs. The authors propose screening programs for "generalists" and not for specialists assumed to possess detailed knowledge of the routes of transmission and clinical presentations, even of very rare tropical infectious diseases. In doubtful cases a physician specializing in tropical medicine has to be consulted who possesses specialized knowledge of the prevalences and clinical manifestations of rare tropical diseases.

The most important helminthoses—including clinical signs, diagnosis, and treatment—are summarized in the e-table.

e-Table. Clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of major worm diseases (e16–e19).

| Pathogen | Clinical symptoms | Eosinophil count*1 | Diagnosis | Treatment |

| Adult nematodes (roundworms) in the intestine | ||||

| Ascaris lumbricoides(maw worm) | Larval migration causes pulmonary symptoms, rarely ileus, liver abscesses, obstructive jaundice | Greatly increased during larval migration, later slightly increased or normal | Detection of eggs in stool | Mebendazole 2 x 100 mg/d for 3 days |

| Ancylostoma, Necator (hookworm) | Larval migration causes pulmonary symptoms, abdominal complaints, poss. (iron deficiency) anemia | Greatly increased during larval migration, later slightly increased or normal | Detection of eggs in stool | Mebendazole 2 x 100 mg/d for 3 days |

| Strongyloides stercoralis (dwarf threadworm) | Larval migration causes pulmonary symptoms, abdominal complaints, severe courses in immunodeficiency | Initially greatly increased, later moderately to slightly increased, in immunodeficiency poss. normal (!) | Detection of larvae in stool (e.g. Baermann test) or duodenal secretion | Albendazole 2 x 400 mg/d or ivermectin*2 1 x 200 µg/kg for 1 to 2 days, repeated after 2 weeks |

| Trichuris trichiura (whipworm) | Rarely rectal prolapse | Slightly increased to normal | Detection of eggs in stool | Mebendazole2 x 100 mg/d for 3 days |

| Enterobius vermicularis (pinworm) | Perianal pruritus, rarely vaginitis, appendicitis | Slightly increased to normal | Detection of eggs in perianal swab sample | Mebendazole 1 x 100 mg/d,repeated after 2 and 4 weeks |

| Trichostrongylus spp. | Diarrhea, abdominal pain | Slightly increased to normal | Detection of eggs in stool | Mebendazole2 x 100 mg/d for 3 days |

| Adult nematodes (roundworms) in tissue | ||||

| Onchocera volvulus | Dermatitis, subcutaneous nodules, ocular involvement | Usually increased | Detection of adult worms in skin nodules (poss. by ultrasonography) or of microfilaria in the skin (skin snip) | Ivermectin*2 150 µg/kg,poss. additionally doxycycline*2100 mg/d for 6 weeks |

| Loa loa | Cutaneous swellings, subconjunctival worm migration | Often greatly increased | Detection of microfilaria in blood | Diethylcarbamazine*2 Caution with high microfilaria counts |

| Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi | Lymph vessel obstruction or even elephantiasis, lymphadenitis, lymphangitis | In early stages | Detection of microfilaria in blood | Diethylcarbamazine*2 |

| Nematode larvae | ||||

| Anisakis spp. | Abdominal pain | Slightly to moderately increased | Clinical and serological | Endoscopically, poss. surgically |

| Toxocara spp. (visceral larva migrans) | Generalized symptoms, poss. focal neurological signs, ocular symptoms | Moderately to greatly increased | Clinical and serological | Albendazole 2 x 400 mg/d over 2 to 4 weeks |

| Gnathostoma spp. | Subcutaneous or visceral larva migrans syndrome | Moderately to greatly increased | Clinical and serological | Albendazole 2 x 400 mg/d over3 weeks poss. also surgical removal |

| Trichinella spp. (trichinosis) | Abdominal complaints, myalgia, periorbital edema, poss. focal neurological signs | Moderately to greatly increased | Clinical, blood test for larvae, serological | Mebendazole 2 x 200 mg/d for 2 weeks or albendazole 400 mg/d over 2 weeks, poss. additionally corticosteroids |

| Cestodes (tapeworms) in the intestine | ||||

| Taenia saginata (beef tapeworm) | Abdominal complaints | Normal to slightly increased | Detection of proglottids in stool | Niclosamide 1 x 2 g or praziquantel 1 x 10 mg/kg |

| Taenia solium (pork tapeworm) | Abdominal complaints | Normal to slightly increased | Detection of proglottids in stool | Niclosamide 1 x 2 g or praziquantel 1 x 10 mg/kg |

| Diphyllobothrium latum (fish tapeworm) | Poss. megaloblastic anemia with glossitis | Normal to slightly increased | Detection of eggs in stool | Niclosamide 1 x 2 g or praziquantel 1 x 25 mg/kg |

| Hymenolepsis nana (dwarf tapeworm) | Abdominal complaints, diarrhea | Normal to slightly increased | Detection of eggs in stool | Praziquantel 1 x 25 mg/kg |

| Tapeworm larvae in tissue | ||||

| Taenia solium (cysticercosis) | Focal neurological signs, subcutaneous nodules | Normal to slightly increased | Imaging, immunodiagnostics | Albendazole 15 mg/kg/d for 30 days |

| Echinococcus granulosus and E. multilocularis | Intrahepatic cysts | Normal to slightly increased | Imaging, immunodiagnostics | Albendazole 15 mg/kg/d for 30 days, often several cycles necessary |

| Trematodes (leeches, flukes) | ||||

| Schistosoma haematobium | Initially poss. fever ("Katayama fever"), dysuria, hematuria, hydronephrosis | In Katayama fever greatly increased, later slightly increased | Detection of eggs in urine or in rectal biopsies | Praziquantel 40 mg/kg/d for 3 days |

| Schistosoma mansoni,S. japonicum,S. intercalatum | Initially poss. fever ("Katayama fever"), abdominal complaints, bloody stool, poss. hepatic fibrosis | In Katayama fever greatly increased, later slightly increased | Detection of eggs in stool or in colon biopsies | Praziquantel 40–60 mg/kg/d for 3 days |

| Fasciolepsis buski (large intestinal fluke) | Nonspecific symptoms | Normal to slightly increased | Detection of eggs in stool | Praziquantel 1 x 15 mg/kg |

| Fasciola spp.(large liver fluke) | Hepatomegaly (often painful), liver abscesses, biliary tract symptoms | In early infection greatly increased,later slightly increased | Detection of eggs in stool and duodenal secretion, adult worm in ultrasonography | Triclabendazole*2 1 x 10 mg/kg for severe infections up to 20 mg/kg |

| Clonorchis and Opisthorchis spp.(Chinese and cat liver fluke) | Biliary tract symptoms, pyrogenic cholangitis, cholangiocarcinoma | In early infection greatly increased, later slightly increased | Detection of eggs in stool and duodenal secretion | Praziquantel 3 x 25 mg/kg/d for 2 days |

| Paragonimus spp.(lung fluke) | Chronic cough, chest pain, hemoptyses or brownish tinged sputum | In early infection greatly increased, later normal | Detection of eggs in stool and sputum, x-ray | Praziquantel 3 x 25 mg/kg/d for 2 days |

*1 Degree of eosinophilia classified according to Brigden (10; modified): mild eosinophilia <1500/µL, moderate to severe eosinophilia >1500/µL

*2 Off-label use, only after consulting a specialist in tropical medicine

Systematic search for evidence

The diagnosis and treatment of tropical diseases should be evidence based. Unfortunately, no sufficiently controlled studies are available on many topics of tropical medicine. Many of the studies that are available were performed in developing countries and their results cannot be extrapolated to Germany. Moreover, many parasitic diseases are rarely imported into industrialized countries, with the result that there are no adequate case numbers. It is therefore difficult to state methods with which to interpret and assess the level of evidence. The Cochrane Collaboration studies are also of limited assistance because for the reasons outlined above they cover only small partial areas of tropical medicine and most of the topics addressed focus on developing countries. It is therefore not surprising that there are hardly any international guidelines. Germany also lacks guidelines for the diagnostic evaluation of eosinophilia in travelers returning from the tropics and migrants. This article is a reflection of expert opinion and was produced on the basis of an informal consensus. The authors performed a review of literature selected by means of a Medline search using the MeSH terms "eosinophilia" and "helminth" for the period 1983 to 2008.

Diagnostic strategies

Since helminth infections can result in serious health impairment and eosinophilia can also point to the presence of various malignant diseases, rapid and efficient diagnostic clarification is essential. Whereas in most cases the treatment of worm diseases is easy, cost effective and safe, an unstructured investigation of eosinophilia is often time consuming, cost intensive and burdensome for the patient. If test results are negative but there is a continued suspicion of helminthosis, an expert in tropical medicine should be consulted.

History

The geographic history is especially important. Some helminths have worldwide prevalence, while others are found only in circumscribed geographic areas. Loa loa (figure 1), for example, is found only in Central and West Africa. Ascaris, on the other hand, has a worldwide distribution. Travelers returning from schistosomiasis-endemic regions, for example, must be questioned specifically about contact with natural fresh waters. An alimentary history can also provide useful information regarding the type of worm infection. Liver flukes, for example, are usually transmitted by the consumption of aquatic plants such as watercress, lung flukes by fresh water crabs and the herring worm by raw sea fish (table 1).

Figure 1.

Subconjunctival localization of Loa loa

Table 1. Helminths transmitted by foods (e20–e22).

| Food | Pathogen |

| Fish, if raw or insufficiently heated | Anisakis and Pseudoterranova, Clonorchis sinensis, Opisthorchis, Diphyllobothrium latum |

| Pork | Taenia solium |

| Beef | Taenia saginata |

| Watercress, water spinach etc. | Fasciola |

| Shellfish and crustaceans | Paragonimus |

| Fish, frogs, snakes, pets fed with fish | Gnathostoma |

| Pork, wild boar, bear, horse, walrus etc. | Trichinella |

Laboratory diagnostics

Besides quantifying eosinophilia in the differential blood count, primary importance attaches to direct identification of pathogens and immune diagnostics. Most desirable is the direct detection of adult worms, larvae in the blood or worm eggs in feces because this is an unequivocal result and requires no interpretation, as for instance in immune diagnostic procedures. For infections with adult worms or with worm larvae which are localized in the tissue, however, direct detection is often not possible. It is then necessary to resort to antibody diagnosis. It should be noted that cross reactions are common within the three groups of tapeworms (cestodes), roundworms (nematodes), and flukes (trematodes). In migrants and travelers who frequently sojourn in tropical regions, the possibility of a serological scar should be considered. Molecular biological techniques, especially the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), will in future simplify the diagnosis of tropical diseases and improve specificity. For example, a PCR for the detection of schistosomiasis is currently being developed.

Asymptomatic eosinophilia

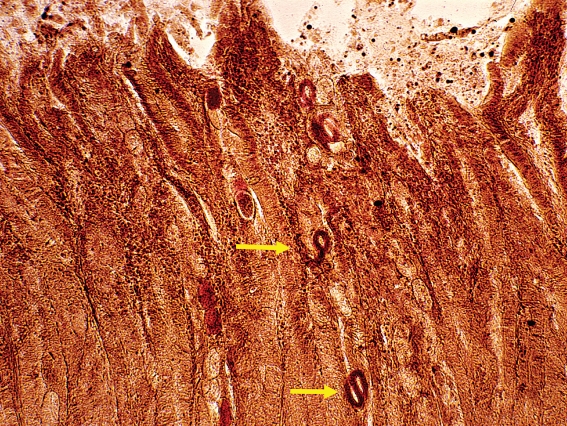

New-onset asymptomatic eosinophilia following a journey to the tropics should first prompt the physician to rule out the presence of parasitic diseases even if the patient has an allergic predisposition. Table 2 presents a structured screening program for this purpose. First it is recommended to analyze the stool three times for worm eggs on three consecutive days. If the stool analyses are negative, tests should be performed for Strongyloides stercoralis. This worm has a worldwide distribution in warm countries (e1). The larvae usually hatch while still in the intestine, which is why the eggs are not detectable in the normal stool tests (figure 2). It is important to exclude Strongyloidiasis because internal and external autoinfection can lead to chronic, persisting disease. It is also possible for a potentially life-threatening hyperinfection syndrome to develop in immunosuppressed persons. A search should also be made for antibodies against schistosomes if the patient has spent time in a schistosomiasis-endemic region (box 1) and the stool samples have tested negative.

Table 2. Diagnosis of asymptomatic eosinophilia.

| Eosinophilia per µL blood | Recommended screening program | Special features |

| ≤1500 | 3 × stool test for worm eggs, if negative: | If results negative: re-test after 3 months |

| Strongyloides and schistosome antibodies in serum (if patient from schistosomiasis-endemic region; see box 1) | ||

| >1500 | 3 x stool test for worm eggs, | If patient from sub-Saharan Africa: additionally Filaria antibodies in serum; if results negative: refer to specialist in tropical medicine |

| 1 × Baermann stool test for Strongyloides stercoralis larvae; Strongyloides, schistosome (if patient from schistosomiasis-endemic region; see box 1), Fasciola (if patient not from schistosomiasis-endemic region) and cysticercal anti-bodies in serum; ECG, chest X-ray, abdominal sonography |

Figure 2.

Larvae of Strongyloides stercoralis in the small intestine

Box 1. Overview of schistosomiasis-endemic regions*.

Schistosomiasis is endemic in the following regions of the world:

Africa, Eastern Brazil, Venezuela, Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Oman, Iraq, Syria, Iran, China, Laos, Cambodia, Phillipines, Sulawesi

Severe eosinophilia (>1500/µL blood) often cannot be sufficiently explained by the detection of worm eggs in the stool. Additional antibody tests for a cestode (tapeworm), a trematode (fluke), and a nematode (roundworm) should thus always be performed. Because of the cross reactions within these groups, a positive antibody test should then be the starting point for further investigations appropriate to the geographic and alimentary history. Chest radiography in two planes is useful in excluding eosinophilic pulmonary infiltrates that can develop during the larval migration of various helminths (frequently: Ascaris, hookworm, or Strongyloides). Upper abdominal imaging (sonography or CT; figure 3) can reveal hepatic lesions that substantiate the suspicion of an infection with liver flukes. Electrocardiography should also rule out nonspecific endomyocardial damage that can develop due to eosinophil degranulation products. If no evidence of the origin of the eosinophilia is found, clarification by a specialist is required.

Figure 3.

Computed tomography. Lesions of the liver in infection with liver flukes (Fasciola hepatica)

Fever

The geographic history is particularly important in patients with eosinophilia and fever (box 1 and table 3). The commonest cause of fever in travelers returning from schistosomiasis-endemic regions and who present with eosinophilia is Katayama syndrome (e2, e3). About 14 to 90 days after initial contact with schistosomes, this acute form of schistosomiasis produces clinical symptoms comprising nocturnal fever, cough, myalgia, headache and abdominal pain developing as a reaction to the maturing worms. In this infectious phase, therefore, usually no eggs are yet excreted in the urine (bladder schistosomiasis) or stools (intestinal schistosomiasis). Antibody diagnosis may initially also give negative results. In such cases the patient should be re-examined after about four weeks and in severe courses a shorter interval is recommended. If eggs are then found, the schistosome species can be identified from the egg morphology, allowing targeted treatment.

Table 3. Diagnosis of eosinophilia with fever.

| Origin (see box 1) | Recommended screening program | Special features |

| From schistosomiasis-endemic region | 3 × stool test for worm eggs | For acute schistosomiasis (Katayama syndrome) poss. no eggs yet in stool or urine, poss. repeat diagnostic tests after 4 weeks |

| Schistosome antibodies in serum ECG, chest X-ray, abdominal sonography | ||

| If negative: | If results negative: | |

| tests as for eosinophilia and fever not from schistosomiasis-endemic region (see below) | refer to specialist in tropical medicine | |

| Not from schistosomiasis-endemic region | 3 × stool test for worm eggs, | If results negative: |

| 1 × Baermann stool test for Strongyloides stercoralis larvae | refer to specialist in tropical medicine | |

| Strongyloides, Trichinella, Toxocara and Fasciola antibodies in serum | ||

| ECG, chest X-ray, abdominal sonography |

In patients who have not visited a schistosomiasis-endemic region, an infection with Fasciola spp. (liver fluke) may be a possible cause of eosinophilia with subfebrile temperatures (e4). These patients are found to have intrahepatic space occupying lesions in imaging studies and also test positive for antibodies. The patient’s further management should then be entrusted to a specialist.

Cutaneous swellings

Periorbital edema in patients with a relevant history—for example following consumption of insufficiently cooked pork or wild boar meat—(table 1) is typical of trichinosis (e5). Blood filtration for trichina larvae should then be performed; a suitable serological screening test is also available (table 4).

Table 4. Diagnosis of eosinophilia with cutaneous swellings.

| Type of cutaneous swelling | Recommended screening program | Special features |

| Periorbital edema | Blood filtration for Trichina larvae | If results negative: |

| Trichinella antibodies in serum | refer to specialist in tropical medicine | |

| Urticaria | 3 × stool test for worm eggs | For patients from sub-Saharan Africa additionally: Filaria antibodies in serum |

| 1 × Baermann stool test for Strongyloides stercoralis larvae | If results negative: | |

| Strongyloides antibodies in serum | refer to specialist in tropical medicine | |

| Schistosome antibodies in serum | ||

| (if patient from schistosomiasis-endemic region see box 1) | ||

| Subcutaneous swellings, poss. migrating | 3 x stool test for worm eggs | For patients from Central Africa: |

| 1 x Baermann stool test for Strongyloides stercoralis larvae | 3 × blood test for microfilaria in blood (perform test at about 12 noon) | |

| Strongyloides, Gnasthosoma, Filaria and Paragonimus antibodies in serum | If results negative: | |

| refer to specialist in tropical medicine |

If urticaria is present, however, a Katayama syndrome should be considered the prime candidate. Alternating subcutaneous swellings occur in gnathostomiasis (e6) and also in loiasis (Calabar swelling). Patients originally from Central and West Africa can therefore immediately be tested for Loa loa (e7). The latest data from the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network show that filaria - such as Loa loa - can also be transmitted during short trips to endemic regions (22).

Abdominal pain

Abdominal pain associated with eosinophilia suggests the presence of acute disease (table 5). Persons infected with liver flukes (such as Fasciola) experience permanent or intermittent pain. Abdominal pain and elevated laboratory values for transaminases may be a sign of toxocariasis (e8). Anisakiasis (caused mainly by the herring worm Anisakis spp. and the codworm Pseudoterranova spp.) may be associated with acute disease symptoms such as acute abdomen or chronic gastroenteritis with recurrent abdominal pain (e9). These diseases, however, are reported less from the tropics than from Holland, Japan, and the American coastal regions. These worms are transmitted by the consumption of raw or insufficiently heated fish (table 1). A sonographic examination should always be performed if there is eosinophilia and abdominal pain, for example in order to identify any liver lesions. Rare causes such as Ascaris lumbricoides that has migrated into the bile duct can also be detected by ultrasonography.

Table 5. Diagnosis of eosinophilia with abdominal pain.

| Recommended screening program | Special features |

| 3 × stool test for worm eggs, | If results negative: |

| 1 × Baermann stool test for | refer to specialist in tropical medicine |

| Strongyloides stercoralis larvae | |

| Strongyloides, Fasciola, Toxocara antibodies in serum | |

| Anisakis antibodies in serum (with corresponding alimentary history; see table 1) | |

| ECG, chest X-ray, abdominal sonography |

Elevated transaminase concentrations

Toxocariasis can lead to increased transaminase concentrations (box 2). Infections with Toxocara canis are common worldwide but only rarely become symptomatic.

Box 2. Diagnosis of eosinophilia with elevated transaminase concentrations.

3 × stool test for worm eggs

Baermann stool test for Strongyloides stercoralis larvae

Strongyloides, Fasciola and Toxocara antibodies in serum

Diarrhea

Diarrhea frequently occurs after a period spent in the tropics, but helminths are only rarely the cause of acute traveler’s diarrhea (e10). If the diarrhea is associated with eosinophilia, the usual screening procedure must be extended. Besides the obligatory screening for Strongyloidiasis, the early stage of trichinosis should also be considered (box 3).

Box 3. Diagnosis of eosinophilia and diarrhea.

3 × stool test for worm eggs

1 × Baermann stool test for Strongyloides stercoralis larvae

Strongyloides antibodies in serum

Trichinella antibodies in serum (with corresponding history; see table 1)

Pulmonary infiltrates

Worm larvae that pass through the lung cause transient pulmonary infiltrates (e11, e12). If this suspicion is present, a stool test should be arranged for about 4 to 6 weeks after the presumed date of infection (table 6). Echinococcosis may manifest in the form of pulmonary, possibly septated cysts on chest radiograph or thoracic CT, and the diagnosis can be substantiated by an antibody test (e13). Imported infections with lung flukes (Paragonimus) have only been described in migrants in a small number of individual cases. The worm cyst with pericystic infiltration appears in the radiograph as an extensive opacity and on CT as an annular structure. The diagnosis is confirmed by the detection of eggs in sputum and stools and by specific antibodies in the serum (e14). Immigrants from South and South East Asia with asthmatic complaints, pulmonary infiltrates, and pronounced eosinophilia in very rare cases have "tropical pulmonary eosinophilia," a special variant of lymphatic filariasis. These patients should be referred to a specialist (e15).

Table 6. Diagnosis of eosinophilia with pulmonary infiltrates.

| Recommended screening program | Special features |

| 3 x stool test for worm eggs (if result negative: repeat stool test after 4 weeks) | Cystic structure in imaging: Echinococcus antibodies in serum; if positive, refer to specialized center |

| 1 x Baermann stool test for | Patient from Indian subcontinent: |

| Strongyloides stercoralis larvae (if result negative: repeat stool test after 4 weeks) | suspicion of tropical pulmonary eosinophilia: refer to specialist in tropical medicine |

| Strongyloides, Toxocara, and Paragonimus antibodies in serum |

Key message.

When eosinophilia is present after periods in the tropics, worm diseases should always be considered.

In infection with intestinal worms, comparatively low eosinophilia is generally found.

In patients with high eosinophilia, tissue worms should be strongly suspected.

In migrants with eosinophilia from the tropics and subtropics, strongyloidiasis should always be ruled out.

For fever and pronounced eosinophilia after a period in a schistosomiasis endemic region, the possibility of Katayama syndrome should always be considered.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof. Dr. Dr. Büttner of the Bernard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine, Hamburg, for his critical review of the manuscript and for supplying the illustrations.

Translated from the original German by mt-g.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists according to the guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

References

- 1.Rothenberg ME. Eosinophilia. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1592–1600. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199805283382206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitty CJM, Mabey DC, Armstrong M, Wright SG, Chiodini PL. Presentation and outcome of 1107 cases of schistosomiasis from Africa diagnosed in a non-endemic country. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2000;94:531–534. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(00)90077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harries AD, Fryatt R, Walker J, Chiodini PL, Bryceson AD. Schistosomiasis in expatriates returning to Britain from the tropics. Lancet. 1986;11:86–88. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)90730-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Libman MD, MacLean JD, Gyorkos TW. Screening for schistosomiasis, filariasis, and strongyloidiasis among expatriates returning from the tropics. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:353–359. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.3.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weller PF. Eosinophilia in travellers. Med Clin North Am. 1992;76:1413–1432. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)30294-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harries AD, Myers B, Bhattacharrya D. Eosinophilia in Caucasians returning from the tropics. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1986;80:327–328. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(86)90049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pardo J, Carranza C, Muro A, et al. Helminth-related eosinophilia in African immigrants, Gran Canaria. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1587–1589. doi: 10.3201/eid1210.060102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seybold LM, Christiansen D, Barnett ED. Diagnostic evaluation of newly arrived asymptomatic refugees with eosinophilia. Clin Inf Dis. 2006;42:363–367. doi: 10.1086/499238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nutman TB. Evaluation and differential diagnosis of marked, persistent eosinophilia. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2007;27:529–549. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brigden ML. A practical workup for eosinophilia. Postgrad Med. 1999;105:193–210. doi: 10.3810/pgm.1999.03.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Löscher T. Fortschritte in der Immundiagnostik und Chemotherapie der Wurminfektionen. Internist. 1983;24:610–618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolfe MS. Eosinophilia in the returning traveller. Med Clin North Am. 1999;83:1019–1032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whetham J, Day JN, Armstrong M, Chiodini PL, Whitty CJM. Investigation of tropical eosinophilia; assessing a strategy based on geographical area. J Infect. 2003;46:180–185. doi: 10.1053/jinf.2002.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ansart S, Perez L, Vergely O, Danis M, Bricaire F, Caumes E. Illnesses in travelers returning from the tropics: a prospective study of 622 patients. J Travel Med. 2005;12:312–318. doi: 10.2310/7060.2005.12603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boggild AK, Yohanna S, Keystone JS, Kain KC. Prospective analysis of parasitic infections in Canadian travelers and immigrants. J Travel Med. 2006;13:138–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2006.00032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Brien DP, Leder K, Matchett E, Brown GV, Torresi J. Illness in returned travelers and immigrants/refugees: the 6-year experience of two Australian infectious diseases units. J Travel Med. 2006;13:138–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2006.00033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toovey S, Moerman F, van Gompel A. Special infectious disease risks of expatriates and long-term travelers in tropical countries. Part II: Infections other than malaria. J Travel Med. 2007;14:50–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2006.00092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Löscher T, Saathoff E. Eosinophilia during intestinal infection. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;22:511–536. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meltzer E, Percik R, Shatzkes J, Sidi Y, Schwartz E. Eosinophilia among returning travelers. A practical approach. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;78:702–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jelinek T. European Network on Imported Infectious Disease Surveillance. Imported schistosomiasis in Europe: preliminary data for 2007 from TropNetEurop. Euro Surveill. 2008 Feb 14; doi: 10.2807/ese.13.07.08038-en. 13. pii 8038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freedman DO, Weld LH, Kozarsky PE, Fisk T, Robins R, von Sonnenburg F, Keystone JS, Pandey P, Cetron MS. GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Spectrum of disease and relation to place of exposure among ill returned travelers. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:119–130. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leder K, Tong S, Weld L, Kain KC, Wilder-Smith A, von Sonnenburg F, Black J, Brown GV, Torresi J. GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Illness in travelers visiting friends and relatives: a review of the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1185–1193. doi: 10.1086/507893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lipner EM, Law MA, Barnett E, et al. for the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network: Filariasis in Travelers Presenting to the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2007;1:e88. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e1.Greiner K, Bettencourt J, Semolic C. Strongyloidiasis: a review and update by case example. Clin Lab Sci. 2008;21:82–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e2.Gryseels B, Polman K, Clerinx J, Kestens L. Human schistosomiasis. Lancet. 2006;368:1106–1118. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69440-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e3.Ross AG, Vickers D, Olds GR, Shah SM, McManus DP. Katayama syndrome. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:218–224. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70053-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e4.Garcia HH, Moro PL, Schantz PM. Zoonotic helminth infections of humans: echinococcosis, cysticercosis and fascioliasis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2007;20:489–494. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3282a95e39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e5.Pozio E, Morales MA Gomez, Dupouy-Camet J. Clinical aspects, diagnosis and treatment of trichinellosis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2003;1:471–482. doi: 10.1586/14787210.1.3.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e6.Clément-Rigolet MC, Danis M, Caumes E. La gnathostomose, une maladie exotique de plus en plus souvent importée dans les pays occidentaux. Presse Med. 2004;33:1527–1532. doi: 10.1016/s0755-4982(04)98978-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e7.Boussinesq M. Loiasis. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2006;100:715–731. doi: 10.1179/136485906X112194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e8.Despommier D. Toxocariasis: clinical aspects, epidemiology, medical ecology, and molecular aspects. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16:265–272. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.2.265-272.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e9.Seitz HM. Die Anisakidose (Heringswurmkrankheit) Dtsch Arztebl. 1990;87(41):A3116–A3120. [Google Scholar]

- e10.Genta RM. Diarrhea in helminthic infections. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16(Suppl 2):S122–S129. doi: 10.1093/clinids/16.supplement_2.s122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e11.Chitkara RK, Krishna G. Parasitic pulmonary eosinophilia. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;27:171–184. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-939520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e12.Vijayan VK. How to diagnose and manage common parasitic pneumonias. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2007;13:218–224. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e3280f31b58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e13.Gottstein B, Reichen J. Hydatid lung disease (echinococcosis/hydatidosis) Clin Chest Med. 2002;23:397–408. doi: 10.1016/s0272-5231(02)00007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e14.Kagawa F. Pulmonary paragonimiasis. Semin Respir Infect. 1997;12:149–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e15.Vijayan VK. Tropical pulmonary eosinophilia: pathogenesis, diagnosis and management. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2007;13:428–433. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e3281eb8ec9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e16.Bethony J, Brooker S, Albonico M, et al. Soil-transmitted helminth infections: ascariasis, trichuriasis, and hookworm. Lancet. 2006;367:1521–1532. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68653-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e17.Reddy M, Gill SS, Kalkar SR, Wu W, Anderson PJ, Rochon PA. Oral drug therapy for multiple neglected tropical diseases: a systematic review. JAMA. 2007;298:1911–1924. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.16.1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e18.Craig P, Ito A. Intestinal cestodes. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2007;20:524–532. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3282ef579e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e19.Keiser J, Utzinger J. Efficacy of current drugs against soil-transmitted helminth infections: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;299:1937–1948. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.16.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e20.Bruckner DA. Helminthic food-borne infections. Clin Lab Med. 1999;19:639–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e21.Fried B, Graczyk TK, Tamang L. Food-borne intestinal trematodiases in humans. Parasitol Res. 2004;93:159–170. doi: 10.1007/s00436-004-1112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e22.Macpherson CN, Gottstein B, Geerts S. Parasitic food-borne and water-borne zoonoses. Rev Sci Tech. 2000;19:240–258. doi: 10.20506/rst.19.1.1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e23.Steinmann P, Keiser J, Bos R, Tanner M, Utzinger J. Schistosomiasis and water resources development: systematic review, meta-analysis, and estimates of people at risk. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:411–425. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70521-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]